Abstract

The emergence of a novel coronavirus named SARS-CoV-2 during December 2019, has caused the global outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is officially announced to be a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). The increasing burden from this pandemic is seriously affecting everyone’s life, and threating the global public health. Understanding the transmission, survival, and evolution of the virus in the environment will assist in the prevention, control, treatment, and eradication of its infection. Herein, we aimed to elucidate the environmental impacts on the transmission and evolution of SARS-CoV-2, based on briefly introducing this respiratory virus. Future research objectives for the prevention and control of these contagious viruses and their related diseases are highlighted from the perspective of environmental science. This review should be of great help to prevent and control the epidemics caused by emerging respiratory coronaviruses (CoVs).

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Transmission route, Evolution, Environmental impact

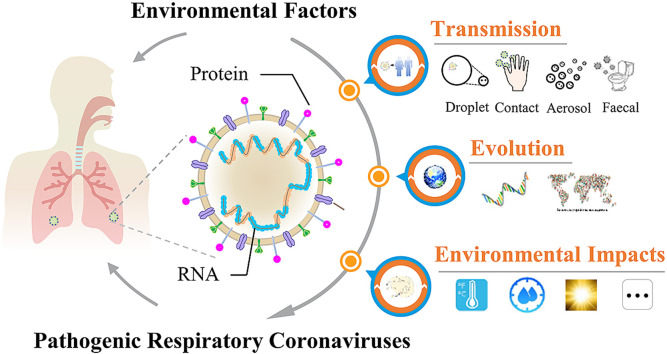

Graphical abstract

Summary: More knowledge on the transmission and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in the environment is urgently needed.

1. Introduction

The emergence of a novel coronavirus (CoV), named SARS-CoV-2, in December 2019, has caused the global outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is officially announced to be a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). The increasing burden from this pandemic is seriously affecting people’s lives, and threating global public health. More than 10, 021, 424 people have been infected worldwide by June 29, 2020, and total deaths have exceeded 499,913 so far (CCDC, 2020). The causative pathogen of COVID-19 is identified to be a novel coronavirus named SARS-CoV-2, also known as 2019-nCoV, which is highly contagious and pathogenic. Like some other human-infectious coronaviruses, e.g. SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, this newly-found CoV causes symptoms typical of colds, pneumonia and even acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Guan et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020), thus posing high risks to human life. Public epidemic prevention measures are now being urgently taken to efficiently control the human-to-human transmission of the virus globally. Although this intervention may decrease the basic reproduction number of this infectious disease (R0) (Hellewell et al., 2020), evaluating the transmission and evolution of the contagious and pathogenic respiratory viruses and related environmental influencing factors are of high priority, for the sake of avoiding the possible additional outbreaks, reoccurrences of public health emergencies of international concern (PHEIC) or pandemics from acute respiratory infection (ARI).

Currently, a total of 7 species of respiratory CoVs, which may cause human infection, have been identified, including HCoV-NL63, HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HKU1, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and the emerging virus, SARS-CoV-2 (Cui et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020a). The pathogenicities of the first four species are low, whereas, the latter three viruses exhibit high infectivity and pathogenicity (Su et al., 2016; Cui et al., 2019). In addition to new discoveries in biological and medical fields, environmental impacts on transmission and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 are worthy of being discussed for the purpose of giving an insight into latent health threats from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and potential trends in its development. Some previous findings have showed that several environmental factors, such as temperature, humidity, and climate change (Murdoch and Jennings, 2009; Peci et al., 2019), are involved in the transmission and evolution of respiratory CoVs. The association between air pollution and respiratory CoV infection has also been widely studied and discussed (Coccia, 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). Understanding the environmental behavior of these viruses is of assistance in guiding efficient measures for prevention and control of the resulting epidemics or pandemics.

This work aimed to give a systematic insight into the potential environmental influences on the prevalence of COVID-19. Although the environmental transmission and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 have not been sufficiently investigated yet, the knowledge regarding previously-found respiratory CoVs could provide inspirations for the present SARS-CoV-2 considering their similar biological structures (Lu et al., 2020). Herein, the potential environmental impacts on the transmission and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 were investigated based on the current findings of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogenic respiratory CoVs: (1) briefly introduce the biological characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogenic respiratory CoVs; (2) elucidate possible transmission routes of these respiratory CoVs; (3) clarify the evolution of these respiratory CoVs including their origin and emergence in human; (4) discuss the environmental impacts on the transmission and evolution of respiratory CoVs; (5) present the advances and future perspectives. This review would raise awareness of the roles of environmental factors in the transmission and evolution of SARS-CoV-2, and help deal with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Biological characteristics of pathogenic respiratory CoVs

Respiratory CoVs are a type of single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus with 5′-cap structure and 3′-poly-A tail. They have a nucleocapsid (N), and an envelope structure containing spike (S), membrane (M) and envelope (E) proteins (Li et al., 2020). As an example, SARS-CoV-2 shows the characteristic crown-like appearance, and belongs to the β coronavirus family, possessing 79% and 50% genome sequence identities with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, respectively (Lu et al., 2020). Entrance of CoVs into host cells occurs through the binding of their S protein to host cell receptors (Wrapp et al., 2020). For example, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a transmembrane glycoprotein in respiratory epithelial cells, is the dominant receptor for SARS-CoV-2 infection (Yan et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). Infected patients may exhibit typical cold symptoms, such as fever, cough, myalgia and fatigue (Guan et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020). A majority of confirmed cases also have mild pneumonia, which may develop into life-threatening hypoxemia and ARDS (Guan et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020). These characteristics share high similarities with those observed in respiratory infections from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV (Peiris et al., 2003; Nassar et al., 2018; Guan et al., 2020). Nevertheless, unlike SARS-CoV- or MERS-CoV-positive patients, a few SARS-CoV-2-infected patients are asymptomatic, but still can spread the virus, which may accelerate human-to-human transmission (Hu et al., 2020; Rothe et al., 2020), and aggravate the outbreak of the pandemic. The high infectivity and high pathogenicity of respiratory CoVs, especially for the currently-prevalent SARS-CoV-2, make it essential to understand their transmission and evolutionary behaviors in the environment, so as to provide the substantial support to control the related epidemic or pandemic.

3. Human-to-human transmission of respiratory CoVs

There are several routes for the human-to-human transmission of respiratory CoVs, including respiratory droplets, close contact, aerosols, feces and water. Respiratory droplets and close contact have been reported to be the dominant modes of transmission for most respiratory CoVs, while aerosols and fecal transmission are also risky in some specific situations (Wong and Yuen, 2008; Kutter et al., 2018).

3.1. Transmission via respiratory droplets

Inhalation of virus-contaminated respiratory droplets may directly lead to the infection by respiratory CoVs. The contaminated droplets, serving as the transmission vector of infectious virus pathogens, can be generated when the patients cough, sneeze and talk, causing the direct deposition of sedimentary droplets in other people’s upper respiratory tracts, or providing contamination sources for other transmission routes like close contact and aerosol etc (Stilianakis and Drossinos, 2010; Teunis et al., 2010). Generally, exhaled droplets travel less than 1 m before settling down on the susceptible mucosa of close contacts or other biotic and abiotic surfaces (Kutter et al., 2018). The duration of droplets suspended in air lasts no longer than 17 min (Knight, 1980). Experimental and observational evidence has been provided for the droplets transmission of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, showing that droplets enable the pathogens to spread efficiently among humans, which can be significantly reduced by precautionary measures (Seto et al., 2003; Zumla et al., 2015; Kutter et al., 2018). Despite the lack of detailed experimental data for transmission of SARS-CoV-2 through droplets, this virus is recognized to be easily passed from person to person through respiratory droplets (Peng et al., 2020). As evidenced by the study of influenza, sneezing can generate more pulmonary bio-aerosols containing influenza virus than can coughing (Chen et al., 2009), and smaller influenza droplets pose a potentially higher indoor infection risk to human beings (Cheng et al., 2016). Altogether, the transmission risk of respiratory CoV-contaminated droplets is top concern regarding frequent social activities and routine face-to-face communications.

3.2. Transmission via close contact

Respiratory CoVs have been found to survive and retain infectivity outside the host. For example, SARS-CoV in respiratory specimens retained its infectiousness for more than 7 d at room temperature (Duan et al., 2003). The survival ability of SARS-CoV on eight different surfaces and in water remained similar, and its infectivity decreased after 72- to 96-h exposure (Duan et al., 2003). Comparatively, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 appeared to have lower survival capacities, losing the infectivity within 72 h on non-absorptive surfaces (Sizun et al., 2000; Muller et al., 2008). Recent investigations showed that SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the ambient environment from sick patients, including floor, glass windows, tables, chairs, door knobs, air outlet fans, toilet bowls, sinks and personal care equipment (Ong et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 can remain viable and infectious on various surfaces (copper, cardboard, plastic and stainless steel) for hours to days (van Doremalen et al., 2020). Consequently, infectious SARS-CoV-2 can be transferred through close contact with contaminated droplet-laden surfaces or objects to mucous membranes of nose, eyes or mouth by hand, potentially leading to infection and development of clinical symptoms.

3.3. Aerosol transmission

Aerosols are defined as solid or liquid suspensions in air, which remain airborne for prolonged duration because of low settling velocity (Yu et al., 2004; Tellier, 2006), and may cause long-range human-to-human transmission of respiratory CoVs (Li et al., 2005). A previous investigation revealed the temporal and spatial distributions of infected cases in a large community outbreak of SARS in Hong Kong, and examined the correlation of these data with the three-dimensional spread of a virus-laden aerosol plume, suggesting viral airborne spread as a reasonable explanation for the large community outbreak of SARS (Yu et al., 2004). Additionally, aerosolized HCoV-229E had a half-life of 67 h in a rotating steel drum (at 20 °C and 50% relative humidity) and MERS-CoV remained stable for 10 min at 20 °C and 40% relative humidity in aerosols (Ijaz et al., 1985; van Doremalen et al., 2013). Recent study demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 remained viable in aerosols for 3 h with a reduction in infectious titer from 103.5 to 102.7 TCID50 (50% tissue-culture infectious dose) per liter of air (van Doremalen et al., 2020). Some medical procedures like intubation, the use of continuous positive-pressure ventilation, drug delivery via nebulizers and dental practice are likely to produce high-concentration aerosols, which may travel further than droplets from coughs (Gamage et al., 2005; Peng et al., 2020). The above information showed that aerosol transmission of respiratory CoVs was of particular concern, especially in healthcare settings and enclosed spaces.

3.4. Fecal and waterborne transmission

Fecal and waterborne routes provide another potential transmission route for respiratory CoVs due to infection-related gastrointestinal symptoms (Shi et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2020b). The detection of viable CoVs in stools of patients and hospital sewage suggested the risk of spread through city sewers (Wang et al., 2005, Wang et al., 2020d). For example, virus was detected in feces, urine and blood from some patients with COVID-19 (Guan et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020d). Studies have shown that SARS-CoV could be viable for 2 d in hospital sewage, domestic sewage and dechlorinated tap water, 3 d in feces, 14 d in PBS, and 17 d in urine at room temperature (Wang et al., 2005). When the temperature was decreased to 4 °C, the virus could persist for 14 d in wastewater and at least 17 d in feces or urine (Wang et al., 2005). Apart from possible infection by the direct contact, fecal contamination with respiratory CoVs might produce a large number of polluted aerosols in vertical soil stacks when toilets were flushed. A representative example was reported for the transmission of the SARS pathogen through a flawed sewage-disposal system among residents in a large community in Hong Kong, resulting in the outbreak of a local SARS epidemic (Yu et al., 2004). Respiratory CoVs via waterborne transmission may also occur in communities that do not have sewage infrastructure, or use wastewater for irrigation, as well as in buildings that have sewage overflows or faulty plumbing systems (Wigginton and Boehm, 2020). Therefore, the spread of respiratory CoVs through fecal and waterborne transmission also needs attention, especially in the control of the currently-ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Evolution of respiratory CoVs

Generally, respiratory CoVs originate from the natural wildlife reservoirs (Forni et al., 2017). Though direct infection of humans is possible, the viruses may need to evolve through gene mutation and recombination to adapt to new hosts in most cases, thus spreading from the original host to some other animal species, and finally becoming human infective (Su et al., 2016; Forni et al., 2017). The origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2 has been shown by analyzing viral genomes of patient specimens from different countries and regions (Wang et al., 2020c; Yeh and Contreras, 2020; Tang et al., 2020). Both genetics and ecology are important in determining whether a RNA virus is able to successfully cross species boundaries, and the evolution of respiratory CoVs can be influenced by genetic factors of the virus itself and human activities.

4.1. Genetic factors for the evolution of respiratory CoVs

Based on currently-available evidence, most respiratory CoVs including SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-229E were considered to have originated in bats (Lau et al., 2005; Corman et al., 2014, 2015; Tao et al., 2017). The latest study demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 was 96.2% identical at the whole-genome level to the coronavirus (RaTG13) from a Rhinolophus affinis bat collected in Yunnan Province, China (Zhou et al., 2020), suggesting bats could be a prime suspect for the origin of SARS-CoV-2. The main mechanisms driving RNA virus evolution include mutation, recombination, natural selection, genetic drift and migration (Moya et al., 2004). RNA viruses have the highest rate of mutation among all organisms due to the high speed of replication and low synthesis fidelity, which, together with recombination, provide an important genetic basis for rapid evolution of RNA viruses, causing an alteration of viral characteristics in host range, antigen composition, drug resistance, or virulence etc (Moya et al., 2004). The mutation in spike glycoprotein of respiratory CoVs might contribute to the cross-species transmission from bats to humans (Benvenuto et al., 2020). Recombination is also an important pathway for emerging viruses to get innovative antigenic combinations and modify antigenicity to enter and adapt to an animal or human host (Worobey and Holmes, 1999). Nine putative recombination patterns involved in spike glycoprotein, RdRp, helicase, and ORF3a have been identified in SARS-CoV-2, which may allow SARS-CoV-2 for adjustments and adaptations in the rapidly changing environment (Rehman et al., 2020).

4.2. Human activities and the evolution of respiratory CoVs

Ecological factors include changes in either the proximity or density of the reservoir hosts or intermediate species, which increase the likelihood of humans being exposed to new pathogens, resulting in the establishment of sustained transmission networks (Moya et al., 2004). Enlargement of human settlements may cause a more frequent contact between human beings and the reservoir or intermediate hosts of emerging RNA viruses, which may help respiratory CoVs transfer from different reservoir species and evolve to be human infective. Additionally, since RNA viruses tend to accumulate mutations during the process of transmission from one infected individual to another (Guan et al., 2003), increase of population size and migration rate may accelerate the transmission of respiratory CoVs as well as their environmental evolution. Lateral transfer from different reservoir species has been reported to be a predominant manner by which RNA viruses could enter new host species (Moya et al., 2004). For instance, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV were inferred to spread to humans through masked palm civet and dromedary camels, respectively (Guan et al., 2003; Raj et al., 2014). Recent studies indicated that the coronavirus isolated from pangolins (Manis javanica) had approximately 90% sequence identity to the genome of SARS-CoV-2, and the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the S protein exhibited high sequence similarity to that of SARS-CoV (Lam et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020), showing that pangolin might act as an intermediate host for SARS-CoV-2. At present, the origin and evolution traces of SARS-CoV-2 are not yet fully confirmed. Wild animal trade, including bushmeat, wildlife medicine, and wildlife crafts, is inferred to be responsible for human infection of many zoonotic viruses involving SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and even SARS-CoV-2 (Awaidy and Hashami, 2020; Yuan et al., 2020). Additionally, anthropogenic alterations on natural habitats and environments (e.g. deforestation, habitat encroachment, agricultural land expansion, and urbanization) are also considered as the possible factors driving interspecies transmission of pathogens from wildlife reservoirs to humans (Brearley et al., 2013).

5. Environmental impacts

The successful transmission of respiratory CoVs largely relies on the maintenance of their viability when traveling between susceptible hosts. Once they are released from a host, their behavior could be directly regulated by diverse environmental factors (e.g. temperature, humidity, climate change, and air pollution). Given the globally-rampant SARS-CoV-2, attentions to the environmental impacts on its transmission and evolution are of high priority.

5.1. Temperature and humidity

Generally, the viabilities of respiratory CoVs will dramatically decrease with the increase of the ambient temperature (Casanova et al., 2010), due to the thermal denaturation of the viral proteins and genomes. It was reported that SARS-CoV lost its infectivity after being heated at 56 °C for 15 min (Chan et al., 2011). Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 was also accelerated by increasing temperature. At room temperature (24 °C), the half-life of SARS-CoV-2 ranged from 6.3 to 18.6 h, but was decreased to 1.0–8.9 h when the temperature was up to 35 °C (Biryukov et al., 2020). Most respiratory viruses containing lipid envelopes, such as influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza, human coronavirus, measles virus, rubella virus, and varicella zoster virus, tend to remain infective at low relative humidity (20–30%), whereas the high relative humidity facilitates the survival of viruses without lipid envelopes, like rhinovirus and adenovirus, due to cross-linking reactions occurring in the surface proteins of these viruses in high humidity (Tang, 2009). Both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 rapidly lost their infectivity under high relative humidity (Chan et al., 2011; Biryukov et al., 2020). Additionally, humidity can alter the dynamics of virus-laden droplets by influencing their evaporation speed and droplet size, resulting in disturbed transmission distance (Nicas et al., 2005). Altogether, temperature and humidity are the most likely factors influencing viral infectivity and its human-to-human transmission. As for the evolution, a few previous studies have shown that temperature may affect the mutation of viruses, particularly some temperature-sensitive mutants (Beachboard et al., 2013; Deng et al., 2019), but the effects of temperature and humidity on mutation and recombination of SARS-CoV-2 have remained a blur so far.

5.2. Physical irradiation and biocidal agents

UV Irradiation was reported to efficiently eliminate the infectivity of CoVs through the inactivation of viral RNA (Duan et al., 2003). Irradiation of SARS-CoV in culture medium under UV for 60 min significantly decreased its infectivity to an undetectable level (Duan et al., 2003). UV irradiation is commonly suggested for the disinfection of an enclosed space. Some biocidal chemicals, such as 75% ethanol solution, disinfectants containing chlorine, peracetic acid and sodium hypochlorite, etc., can also effectively inactivate respiratory CoVs, including SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 (Wong and Yuen, 2008; Kampf et al., 2020), which provide useful disinfection approaches for contaminated household surfaces, floors, sewage and medical care area, avoiding the viral infection through direct contact.

5.3. Climate change

Climate change is becoming a global public health concern due to its impacts on the pandemic of viral respiratory infections. Global average surface temperature has been reported to increase 0.8 °C (1.4 °F) over the past century (Ebi and Semenza, 2008), and the thinning and breakup of the arctic ice resulting from climate changes is suspected to lead to the appearance of novel insects and microbes (e.g. virus and bacteria) (Omenn, 2010). Climate conditions, especially ambient temperature, precipitation and humidity, were connected with the survival, reproduction, distribution and abundance of the intermediate vectors, and the physiological conditions, immune responses and crowding occurrence of the specific hosts (Monto, 2004; Campbell et al., 2015; Paz, 2015), thus increasing the outbreak risk of the epidemic of respiratory infectious diseases. Worldwide climate changes, mainly temperature and carbon dioxide (CO2) variations, had the possibility to affect the mutation of rotavirus and hepatitis A virus (Tarek et al., 2019). To date, the evidence on climatic influences on the evolution of respiratory CoVs has been still lacking.

A study on the association between weather and SARS transmission in Beijing and Hong Kong in the 2003 epidemic showed that weather factors (e.g. daily temperature, rainfall and air pressure) was associated with the daily confirmed SARS cases. Other respiratory CoVs, like HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-229E, are likely to behave in a seasonal manner (Owusu et al., 2014; Abramczuk et al., 2017). As for the epidemic of SARS-CoV-2, how the factor of climate influences its reoccurrence is still to be elucidated. Climates were believed to relate to COVID-19 global distribution because climates in different latitudes may contribute to population density, regional economy and health care condition, thereby influencing the spread of COVID-19 (Baqui et al., 2020; Sarmadi et al., 2020). Human activities may change with the weather conditions, resulting in different human-to-human transmission risks of the disease (Bi et al., 2007). Understanding the pattern of global CoV seasonality and its pivotal environmental regulators is essential for preparing the effective strategies to prevent and control the respiratory infectious diseases, like COVID-19 pandemic.

5.4. Air pollution

Epidemiological investigations based on meta-analysis have suggested ambient air pollution could be a risk factor, contributing to the rapid spread of viral respiratory infections and the increased symptoms and mortality of respiratory infectious diseases (Lin et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2010; Mehta et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2016). For instance, a positive correlation was observed between the respiratory infection rate among children and the levels of ambient particulate matter (PM) or gaseous pollutants (e.g. SO2, NO2, and CO) in Hangzhou and Toronto (Lin et al., 2005; Ye et al., 2016). The exploration on the correlation between air pollution and SARS case fatality via model fitting showed that the mortality risk of SARS patients from regions with moderate air pollution index (APIs) was increased by 84% when compared with that of the patients from regions with low APIs (Cui et al., 2003). A recent investigation based on 120 cities in China found that the levels of PM2.5, PM10, CO, NO2, and O3 were positively associated with the number of COVID-19 confirmed cases, while the concentration of SO2 showed negative association with the number of COVID-19 confirmed cases (Zhu et al., 2020). A study based on the COVID-19 cases in Italy also demonstrated that cities with more than 100 days of air pollution (exceeding the limit sets for PM10 or ozone) had a high average number of infected individuals, and the factor of air pollution might be involved in the diffusion intensity of COVID-19 infection (Coccia, 2020). As a potential virus-laden vehicle, ambient PM might also contribute to the enlargement of virus populations in a host and human-to-human transmission of respiratory CoVs (Weinhold, 2004; Qu et al., 2020). An in vitro test showed infectious respiratory pathogens could harbor on PM for prolonged periods, and the joint effect of PM and viruses on cytokine secretion of respiratory epithelial cells was distinct from that observed after the viral exposure alone (Cruz-Sanchez et al., 2013). Additionally, toxicological evidence showed that exposure to ambient PM could cause pulmonary inflammation and affect host defenses against infection (Samet et al., 2006). For instance, organic pollutants and metals adsorbed by ambient PM appear to exhibit diverse biological effects, including oxidative stress, pro-inflammatory effects, pulmonary injury, and cardiovascular toxicity, etc., which could be regulated by size, source, and chemical compositions of ambient PM (Kelly and Fussell, 2012). Indoor air pollution resulting from smoking, cooking, and solid fuel and biomass burning might also be a risk factor associated with COVID-19 infection due to the release of toxic chemicals and PMs (de Leon-Martinez et al., 2020). In some densely populated and severe COVID-19-ridden areas, air pollution should be of particular concern (Baqui et al., 2020; de Leon-Martinez et al., 2020). Overall, the interactions between ambient air pollution and viruses as well as their combined effects need to be unveiled for the purpose of efficiently controlling COVID-19 pandemic.

6. Advances and concluding remarks

The novel SARS-CoV-2 has caused the global outbreak of COVID-19, and human society has suffered greatly from this pandemic. Researchers have called for attention to the environmental factors affecting the transmission of COVID-19 (Eslami and Jalili, 2020; Qu et al., 2020). Roles of some environmental factors like temperature and humidity have been elucidated in the transmission of respiratory CoVs (Pica and Bouvier, 2012; Eslami and Jalili, 2020), but new knowledge and insights on COVID-19 should also be updated constantly. Compared to these previous articles, the current review discussed the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 based on its biological features and the commonality of previously-found respiratory CoVs. In particular, some transmission routes of widespread concern, like aerosol transmission and fecal and waterborne transmission, were systematically summarized. More importantly, major environmental factors including ambient air pollution were objectively discussed to clarify their potential impacts on the transmission and evolution of SARS-CoV-2.

People are striving for elimination of this public health crisis, yet there is a long way to go, and more knowledge of the virus survival, evolution, and transmission in the environment are urgently needed. Although numerous research findings have been obtained, strong evidences and conclusive results remain to be achieved: (1) The influences of ambient air pollution especially PMs on the transmission of COVID-19 are controversial. Further evidence is needed to prove the connection between air pollution and COVID-19 infection. (2) Recent cases of COVID-19 suggested that the contaminated food with virus may cause transmission through the process of production, processing, transport, and selling (Ceylan et al., 2020). Consequently, SARS-CoV-2 in food safety and hygiene should cause a concern, and prevention and regulatory strategies may be of high priority in the future. (3) The pivotal process and environmental selection pressures during the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 are still unclear. Monitoring the seasonal prevalence, tracing the environmental evolution, and uncovering the original hosts are important for predicting the breakout of emerging contagions.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (21806178, 21527901) and Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (SZSM201811070).

Footnotes

This paper has been recommended for acceptance by Da Chen.

References

- Abramczuk E., Pancer K., Gut W., Litwinska B. Non-pandemic human coronaviruses - characteristics and diagnostics. Postepy Mikrobiol. 2017;56(2):205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Awaidy A.S., Hashami A.H. Zoonotic diseases in Oman: successes, challenges, and future directions. Vector-Borne Zoonot. 2020;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2019.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baqui P., Bica I., Marra V., Ercole A., van der Schaar M. Ethnic and regional variations in hospital mortality from COVID-19 in Brazil: a cross-sectional observational study. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8(8):e1018–e1026. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30285-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beachboard D.C., Lu X., Baker S.C., Denison M.R. Murine hepatitis virus nsp4 N258T mutants are not temperature-sensitive. Virology. 2013;435(2):210–213. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuto D., Giovanetti M., Ciccozzi A., Spoto S., Angeletti S., Ciccozzi M. The 2019-new coronavirus epidemic: evidence for virus evolution. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(4):455–459. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi P., Wang J., Hiller J.E. Weather: driving force behind the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome in China? Intern. Med. J. 2007;37(8):550–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biryukov J., Boydston J.A., Dunning R.A., Yeager J.J., Wood S., Reese A.L., Ferris A., Miller D., Weaver W., Zeitouni N.E., Phillips A., Freeburger D., Hooper I., Ratnesar-Shumate S., Yolitz J., Krause M., Williams G., Dawson D.G., Herzog A., Dabisch P., Wahl V., Hevey M.C., Altamura L.A. Increasing temperature and relative humidity accelerates inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces. mSphere. 2020;5(4) doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00441-20. e00441-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brearley G., Rhodes J., Bradley A., Baxter G., Seabrook L., Lunney D., Liu Y., McAlpine C. Wildlife disease prevalence in human-modified landscapes. Biol. Rev. 2013;88(2):427–442. doi: 10.1111/brv.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L.P., Luther C., Moo-Llanes D., Ramsey J.M., Danis-Lozano R., Peterson A.T. Climate change influences on global distributions of dengue and chikungunya virus vectors. Philos. T. R. Soc. B. 2015;370(1665):20140135. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova L.M., Jeon S., Rutala W.A., Weber D.J., Sobsey M.D. Effects of air temperature and relative humidity on coronavirus survival on surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76(9):2712–2717. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02291-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCDC (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention) Globle epidemic distribution of COVID-19. Chinese center for disease control and prevention. 2020. http://2019ncov.chinacdc.cn/2019-nCoV/global.html

- Ceylan Z., Meral R., Cetinkaya T. Relevance of SARS-CoV-2 in food safety and food hygiene: potential preventive measures, suggestions and nanotechnological approaches. Virusdisease. 2020;31(2):154–160. doi: 10.1007/s13337-020-00611-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.H., Peiris J.S.M., Lam S.Y., Poon L.L.M., Yuen K.Y., Seto W.H. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. Advances in Virology. 2011;2011:734690. doi: 10.1155/2011/734690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P.-S., Tsai F.T., Lin C.K., Yang C.-Y., Chan C.-C., Young C.-Y., Lee C.-H. Ambient influenza and avian influenza virus during dust storm days and background days. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118(9):1211–1216. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.C., Chio C.P., Jou L.J., Liao C.M. Viral kinetics and exhaled droplet size affect indoor transmission dynamics of influenza infection. Indoor Air. 2009;19(5):401–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2009.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.H., Wang C.H., You S.H., Hsieh N.H., Chen W.Y., Chio C.P., Liao C.M. Assessing coughing-induced influenza droplet transmission and implications for infection risk control. Epidemiol. Infect. 2016;144(2):333–345. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815001739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Factors determining the diffusion of COVID-19 and suggested strategy to prevent future accelerated viral infectivity similar to COVID. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138474. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corman V.M., Baldwin H.J., Tateno A.F., Zerbinati R.M., Annan A., Owusu M., Nkrumah E.E., Maganga G.D., Oppong S., Adu-Sarkodie Y., Vallo P., Ribeiro Ferreira da Silva Filho L.V., Leroy E.M., Thiel V., van der Hoek L., Poon L.L.M., Tschapka M., Drosten C., Drexler J.F. Evidence for an ancestral association of human coronavirus 229E with bats. J. Virol. 2015;89(23):11858–11870. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01755-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corman V.M., Ithete N.L., Richards L.R., Schoeman M.C., Preiser W., Drosten C., Drexler J.F. Rooting the phylogenetic tree of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus by characterization of a conspecific virus from an African bat. J. Virol. 2014;88(19):11297–11303. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01498-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Sanchez T.M., Haddrell A.E., Hackett T.L., Singhera G.K., Marchant D., Lekivetz R., Meredith A., Horne D., Knight D.A., van Eeden S.F., Bai T.R., Hegele R.G., Dorscheid D.R., Agnes G.R. Formation of a stable mimic of ambient particulate matter containing viable infectious respiratory syncytial virus and its dry-deposition directly onto cell cultures. Anal. Chem. 2013;85(2):898–906. doi: 10.1021/ac302174y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Li F., Shi Z. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Zhang Z., Froines J., Zhao J., Wang H., Yu S., Detels R. Air pollution and case fatality of SARS in the People’s Republic of China: an ecologic study. Environ. Health. 2003;2(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon-Martinez L.D., de la Sierra-de la Vega L., Palacios-Ramirez A., Rodriguez-Aguilar M., Flores-Ramirez R. Critical review of social, environmental and health risk factors in the Mexican indigenous population and their capacity to respond to the COVID-19. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;733:139357. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X., Mettelman R.C., O’Brien A., Thompson J.A., O’Brien T.E., Baker S.C. Analysis of coronavirus temperature-sensitive mutants reveals an interplay between the macrodomain and papain-Like protease impacting replication and pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2019;93(12) doi: 10.1128/JVI.02140-18. e02140-02118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan S.M., Zhao X.S., Wen R.F., Huang J.J., Pi G.H., Zhang S.X., Han J., Bi S.L., Ruan L., Dong X.P. Stability of SARS coronavirus in human specimens and environment and its sensitivity to heating and UV irradiation. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2003;16(3):246–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebi K.L., Semenza J.C. Community-based adaptation to the health impacts of climate change. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008;35(5):501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eslami H., Jalili M. The role of environmental factors to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Amb. Express. 2020;10:92. doi: 10.1186/s13568-020-01028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forni D., Cagliani R., Clerici M., Sironi M. Molecular evolution of human coronavirus genomes. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25(1):35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamage B., Moore D., Copes R., Yassi A., Bryce E., Respiration B.C.I. Protecting health care workers from SARS and other respiratory pathogens: a review of the infection control literature. Am. J. Infect. Contr. 2005;33(2):114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., Liang W., Ou C., He J., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C., Hui D.S.C., Du B., Li L., Zeng G., Yuen K.-Y., Chen R., Tang C., Wang T., Chen P., Xiang J., Li S., Wang J., Liang Z., Peng Y., Wei L., Liu Y., Hu Y., Peng P., Wang J., Liu J., Chen Z., Li G., Zheng Z., Qiu S., Luo J., Ye C., Zhu S., Zhong N. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Zheng B.J., He Y.Q., Liu X.L., Zhuang Z.X., Cheung C.L., Luo S.W., Li P.H., Zhang L.J., Guan Y.J., Butt K.M., Wong K.L., Chan K.W., Lim W., Shortridge K.F., Yuen K.Y., Peiris J.S.M., Poon L.L.M. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in Southern China. Science. 2003;302(5643):276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellewell J., Abbott S., Gimma A., Bosse N.I., Jarvis C.I., Russell T.W., Munday J.D., Kucharski A.J., Edmunds W.J., Funk S., Eggo R.M. Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8(4):e488–e496. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Song C., Xu C., Jin G., Chen Y., Xu X., Ma H., Chen W., Lin Y., Zheng Y., Wang J., Hu Z., Yi Y., Shen H. Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with COVID-19 Screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020;63:706–711. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijaz M.K., Brunner A.H., Sattar S.A., Nair R.C., Johnsonlussenburg C.M. Survival characteristics of airborne human coronavirus 229E. J. Gen. Virol. 1985;66:2743–2748. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-66-12-2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampf G., Todt D., Pfaender S., Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020;104(3):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly F.J., Fussell J.C. Size, source and chemical composition as determinants of toxicity attributable to ambient particulate matter. Atmos. Environ. 2012;60:504–526. [Google Scholar]

- Knight V. Viruses as agents of airborne contagion. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1980;353:147–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb18917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutter J.S., Spronken M.I., Fraaij P.L., Fouchier R.A.M., Herfst S. Transmission routes of respiratory viruses among humans. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2018;28:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam T.T.-Y., Jia N., Zhang Y.-W., Shum M.H.-H., Jiang J.-F., Zhu H.-C., Tong Y.-G., Shi Y.-X., Ni X.-B., Liao Y.-S., Li W.-J., Jiang B.-G., Wei W., Yuan T.-T., Zheng K., Cui X.-M., Li J., Pei G.-Q., Qiang X., Cheung W.Y.-M., Li L.-F., Sun F.-F., Qin S., Huang J.-C., Leung G.M., Holmes E.C., Hu Y.-L., Guan Y., Cao W.-C. Identifying SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020;583:282–285. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S.K.P., Woo P.C.Y., Li K.S.M., Huang Y., Tsoi H.W., Wong B.H.L., Wong S.S.Y., Leung S.Y., Chan K.H., Yuen K.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102(39):14040–14045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506735102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Fan Y., Lai Y., Han T., Li Z., Zhou P., Pan P., Wang W., Hu D., Liu X., Zhang Q., Wu J. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(4):424–432. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Huang X., Yu I.T.S., Wong T.W., Qian H. Role of air distribution in SARS transmission during the largest nosocomial outbreak in Hong Kong. Indoor Air. 2005;15(2):83–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Stieb D.M., Chen Y. Coarse particulate matter and hospitalization for respiratory infections in children younger than 15 years in Toronto: a case-crossover analysis. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):E235–E240. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N., Bi Y., Ma X., Zhan F., Wang L., Hu T., Zhou H., Hu Z., Zhou W., Zhao L., Chen J., Meng Y., Wang J., Lin Y., Yuan J., Xie Z., Ma J., Liu W.J., Wang D., Xu W., Holmes E.C., Gao G.F., Wu G., Chen W., Shi W., Tan W. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S., Shin H., Burnett R., North T., Cohen A.J. Ambient particulate air pollution and acute lower respiratory infections: a systematic review and implications for estimating the global burden of disease. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 2013;6(1):69–83. doi: 10.1007/s11869-011-0146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monto A.S. Occurrence of respiratory virus: time, place and person. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2004;23(1):S58–S63. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000108193.91607.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya A., Holmes E.C., Gonzalez-Candelas F. The population genetics and evolutionary epidemiology of RNA viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2(4):279–288. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A., Tillmann R.L., Muller A., Simon A., Schildgen O. Stability of human metapneumovirus and human coronavirus NL63 on medical instruments and in the patient environment. J. Hosp. Infect. 2008;69(4):406–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch D.R., Jennings L.C. Association of respiratory virus activity and environmental factors with the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease. J. Infect. 2009;58(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar M.S., Bakhrebah M.A., Meo S.A., Alsuabeyl M.S., Zaher W.A. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis and clinical characteristics. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmaco. 2018;22(15):4956–4961. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201808_15635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicas M., Nazaroff W.W., Hubbard A. Toward understanding the risk of secondary airborne infection: emission of respirable pathogens. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2005;2(3):143–154. doi: 10.1080/15459620590918466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omenn G.S. Evolution and public health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:1702–1709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906198106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong S.W.X., Tan Y.K., Chia P.Y., Lee T.H., Ng O.T., Wong M.S.Y., Marimuthu K. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323(16):1610–1612. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu M., Annan A., Corman V.M., Larbi R., Anti P., Drexler J.F., Agbenyega O., Adu-Sarkodie Y., Drosten C. Human coronaviruses associated with upper respiratory tract infections in three rural areas of Ghana. PloS One. 2014;9(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz S. Climate change impacts on West Nile virus transmission in a global context. Philos. T. R. Soc. B. 2015;370(1665):20130561. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peci A., Winter A.-L., Li Y., Gnaneshan S., Liu J., Mubareka S., Gubbay J.B. Effects of absolute humidity, relative humidity, temperature, and wind speed on influenza activity in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019;85(6) doi: 10.1128/AEM.02426-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris J.S.M., Chu C.M., Cheng V.C.C., Chan K.S., Hung I.F.N., Poon L.L.M., Law K.I., Tang B.S.F., Hon T.Y.W., Chan C.S., Chan K.H., Ng J.S.C., Zheng B.J., Ng W.L., Lai R.W.M., Guan Y., Yuen K.Y., Grp H.U.S.S. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia:A prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X., Xu X., Li Y., Cheng L., Zhou X., Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):9. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pica N., Bouvier N.M. Environmental factors affecting the transmission of respiratory viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2(1):90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu G., Li X., Hu L., Jiang G. An Imperative need for research on the role of environmental factors in transmission of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54(7):3730–3732. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c01102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj V.S., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Fouchier R.A.M., Haagmans B.L. MERS: emergence of a novel human coronavirus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014;5:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman S.U., Shafique L., Ihsan A., Liu Q.Y. Evolutionary trajectory for the emergence of novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Pathogens. 2020;9(3):240. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9030240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C., Zimmer T., Thiel V., Janke C., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Drosten C., Vollmar P., Zwirglmaier K., Zange S., Wolfel R., Hoelscher M. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet J.M., Brauer M., Schlesinger R. Air Quality Guidelines: Global Update 2005. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen: 2006. Particulate matter. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmadi M., Marufi N., Kazemi Moghaddam V. Association of COVID-19 global distribution and environmental and demographic factors: an updated three-month study. Environ. Res. 2020;188:109748. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto W.H., Tsang D., Yung R.W.H., Ching T.Y., Ng T.K., Ho M., Ho L.M., Peiris J.S.M. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Lancet. 2003;361(9368):1519–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13168-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.Y., Gong E.C., Gao D.X., Zhang B., Zheng J., Gao Z.F., Zhong Y.F., Zou W.Z., Wu B.Q., Fang W.G., Liao S.L., Wang S.L., Xie Z.G., Lu M., Hou L., Zhong H.H., Shao H.Q., Li N., Liu C.R., Pei F., Yang J.P., Wang Y.P., Han Z.H., Shi X.H., Zhang Q.Y., You J.F., Zhu X., Gu J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome associated coronavirus is detected in intestinal tissues of fatal cases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005;100(1):169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sizun J., Yu M.W.N., Talbot P.J. Survival of human coronaviruses 229E and OC43 in suspension and after drying on surfaces: a possible source of hospital-acquired infections. J. Hosp. Infect. 2000;46(1):55–60. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stilianakis N.I., Drossinos Y. Dynamics of infectious disease transmission by inhalable respiratory droplets. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2010;7(50):1355–1366. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S., Wong G., Shi W., Liu J., Lai A.C.K., Zhou J., Liu W., Bi Y., Gao G.F. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(6):490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J.W. The effect of environmental parameters on the survival of airborne infectious agents. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2009;6:S737–S746. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0227.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X., Wu C., Li X., Song Y., Yao X., Wu X., Duan Y., Zhang H., Wang Y., Qian Z., Cui J., Lu J. On the origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020;7(6):1012–1023. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y., Shi M., Chommanard C., Queen K., Zhang J., Markotter W., Kuzmin I.V., Holmes E.C., Tong S.X. Surveillance of bat coronaviruses in Kenya identifies relatives of human coronaviruses NL63 and 229E and their recombination history. J. Virol. 2017;91(5) doi: 10.1128/JVI.01953-16. e01953-01916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarek F., Hassou N., Benchekroun M.N., Boughribil S., Hafid J., Ennaji M.M. Impact of rotavirus and hepatitis A virus by worldwide climatic changes during the period between 2000 and 2013. Bioinformation. 2019;15(3):194–200. doi: 10.6026/97320630015194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellier R. Review of aerosol transmission of influenza A virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12(11):1657–1662. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teunis P.F.M., Brienen N., Kretzschmar M.E.E. High infectivity and pathogenicity of influenza A virus via aerosol and droplet transmission. Epidemics. 2010;2(4):215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., Harcourt J.L., Thornburg N.J., Gerber S.I., Lloyd-Smith J.O., de Wit E., Munster V.J. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Munster V.J. Stability of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) under different environmental conditions. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(38):7–10. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.38.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.W., Li J.S., Jin M., Zhen B., Kong Q.X., Song N., Xiao W.J., Yin J., Wei W., Wang G.J., By Si, Guob B.Z., Liu C., Ou G.R., Wang M.N., Fang T.Y., Chao F.H., Li J.W. Study on the resistance of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus. J. Virol. Methods. 2005;126(1–2):171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Horby P.W., Hayden F.G., Gao G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., Wang B., Xiang H., Cheng Z., Xiong Y., Zhao Y., Li Y., Wang X., Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Li M., Ren R., Li L., Chen E.-Q., Li W., Ying B. International expansion of a novel SARS-CoV-2 mutant. J. Virol. 2020;94(12) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00567-20. e00567-00520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R., Lu R., Han K., Wu G., Tan W. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323(18):1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhold B. Infectious disease: the human costs of our environmental errors. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004;112(1):A32–A39. doi: 10.1289/ehp.112-a32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigginton K.R., Boehm A.B. Environmental engineers and scientists have important roles to play in stemming outbreaks and pandemics caused by enveloped viruses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54(7):3736–3739. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c01476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S.S.Y., Yuen K.-Y. The management of coronavirus infections with particular reference to SARS. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;62(3):437–441. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worobey M., Holmes E.C. Evolutionary aspects of recombination in RNA viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80:2535–2543. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-10-2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.-L., Abiona O., Graham B.S., McLellan J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367(6483):1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao K., Zhai J., Feng Y., Zhou N., Zhang X., Zou J., Li N., Guo Y., Li X., Shen X. Isolation and characterization of 2019-nCoV-like coronavirus from malayan pangolins. bioRxiv Published on February. 2020;20 doi: 10.1101/2020.1102.1117.951335. 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xia L., Guo Y., Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., Shu H., Xia Ja, Liu H., Wu Y., Zhang L., Yu Z., Fang M., Yu T., Wang Y., Pan S., Zou X., Yuan S., Shang Y. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Resp. Med. 2020;8(5):475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q., Fu J., Mao J., Shang S. Haze is a risk factor contributing to the rapid spread of respiratory syncytial virus in children. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016;23(20):20178–20185. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh T.-Y., Contreras G.P. Emerging viral mutants in Australia suggest RNA recombination event in the SARS-CoV-2 genome. Med. J. Aust. 2020;213(1):44. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu I.T.S., Li Y.G., Wong T.W., Tam W., Chan A.T., Lee J.H.W., Leung D.Y.C., Ho T. Evidence of airborne transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350(17):1731–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J.J., Lu Y.L., Cao X.H., Cui H.T. Regulating wildlife conservation and food safety to prevent human exposure to novel virus. Ecosys. Health Sustain. 2020;6(1):1741325. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Yang X., Wang X., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C., Chen H., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R., Liu M., Chen Y., Shen X., Wang X., Zheng X., Zhao K., Chen Q., Deng F., Liu L., Yan B., Zhan F., Wang Y., Xiao G., Shi Z. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Xie J., Huang F., Cao L. Association between short-term exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 infection: evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;727:138704. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumla A., Hui D.S., Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):995–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60454-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]