ABSTRACT

Over the past 16 years, three coronaviruses (CoVs), severe acute respiratory syndrome CoV (SARS-CoV) in 2002, Middle East respiratory syndrome CoV (MERS-CoV) in 2012 and 2015, and SARS-CoV-2 in 2020, have been causing severe and fatal human epidemics. The unpredictability of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) poses a major burden on health care and economic systems across the world. This is caused by the paucity of in-depth knowledge of the risk factors for severe COVID-19, insufficient diagnostic tools for the detection of SARS-CoV-2, as well as the absence of specific and effective drug treatments. While protective humoral and cellular immune responses are usually mounted against these betacoronaviruses, immune responses to SARS-CoV2 sometimes derail towards inflammatory tissue damage, leading to rapid admissions to intensive care units. The lack of knowledge on mechanisms that tilt the balance between these two opposite outcomes poses major threats to many ongoing clinical trials dealing with immunostimulatory or immunoregulatory therapeutics. This review will discuss innate and cognate immune responses underlying protective or deleterious immune reactions against these pathogenic coronaviruses.

Keywords: Covid-19, Sars-CoV-2, Coronavirus, immune response, immunity, cellular, humoral

Introduction

Three zoonotic positive sense single-stranded RNA betacoronavirus that cause lethal respiratory tract infections in humans feature on the World Health Organization (WHO) Blueprint list of priority pathogens for research and development due to their pandemic potential: the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and the recently discovered novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2).1,2 SARS-CoV-2 was first identified in patients with pneumonia in Wuhan, China in late 2019 and has rapidly spread to all continents. The unprecedented outbreak of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) was declared a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) by the WHO. At the end of July 2020, approximately 14 million cases of COVID-19 have been ‘officially’ diagnosed, and more than 614,000 deaths from COVID-19 have been reported to the World Health Organization.3 The true number of COVID-19 infections remains to be determined.3,4 Data from studies of COVID from China, Europe and USA show that clinical manifestation of COVID-19 ranges from asymptomatic or mild upper respiratory illness to moderate and severe disease, rapidly progressive pneumonitis, respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiorgan failure with fatal outcomes. The natural history of the disease can be divided into four different phases, from incubation toward critical illness in which the direct cytotoxic effects of SARS CoV-2, coagulopathy and exacerbated immune responses play critical roles in the progression to severe illness (Figure 1).6,11 Many individuals remain asymptomatic whereas some go on to develop mild disease and are not all detected by routine COVID19 screening services.11 The diagnosis of COVID-19 currently relies on qPCR detection of viral nucleic acids in nasopharyngeal swabs.3 From a respiratory infection, COVID-19 can rapidly evolve into a systemic disease, as evidenced by the extrapulmonary manifestations (Figure 2). Systemic manifestations are associated with an inflammatory syndrome (elevated serum levels of interleukin-6 [IL-6], alarmins and inflammatory chemokines), a profound lymphopenia, coagulopathy in multiple vascular territories, either related to a systemic immunopathology (as exemplified by the presence of anticardiolipin IgA, anti–β2 -glycoprotein IgA and IgG antibodies and cold agglutinin20-26), a direct infection of endothelial cells of lung capillaries expressing the SARS-CoV-2 angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor 27,28 or a hyperactivated innate immune response29 (Figure 2). Finally, the incidence and severity of COVID-19 correlate with risk factors and comorbidities, such as older age, cancer, obesity, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes linked to immuno-senescence, immunosuppression or immunopathologies.30-33

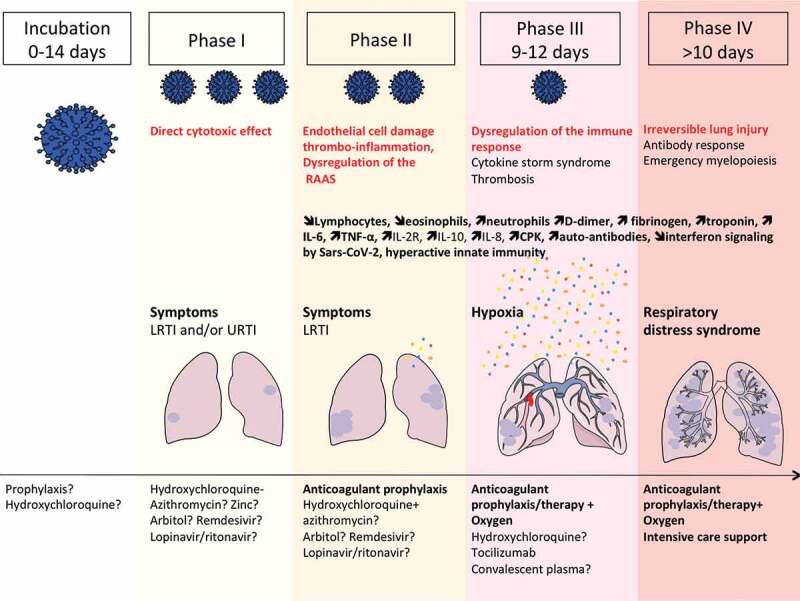

Figure 1.

Natural history of COVID-19 infection, from incubation to critical disease.

Incubation phase is reported as variable between 0-14 days,3,5 then first clinical symptoms, upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) (rhinitis, anosmia and agueusia) and/or lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI)(cough, fever, thoracic pain and “happy hypoxia”) are observed. The second phase is characterised by persistent LRTI and leads to medical consultation and/or hospitalization. In the second phase of the disease, abnormal blood parameters involved in the severity of the disease can be observed. Then,from day 9 to 12 after the onset of symptoms (phase III), sudden deterioration caused by the cytokine storm syndrome and pulmonary (macro and micro) embolism can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (phase IV) and death. Therapeutic strategies have been proposed for each stage of the disease.6 At the time of incubation, prophylaxis with hydroxychloroquine has showed mitigated results depending on the dosing.7 In the first and second phase of the disease, hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin and zinc showed promising results6,8,9 Anticoagulant prophylaxis should be used from phase II to IV, since it was shown to reduce both, the cytokine storm and the risk of thrombotic complications.10 Tocilizumab therapy may be useful in the third phase of the disease at the time of cytokine storm syndrome. Oxygen and intensive care therapy are used in the third and fourth phases of the disease.

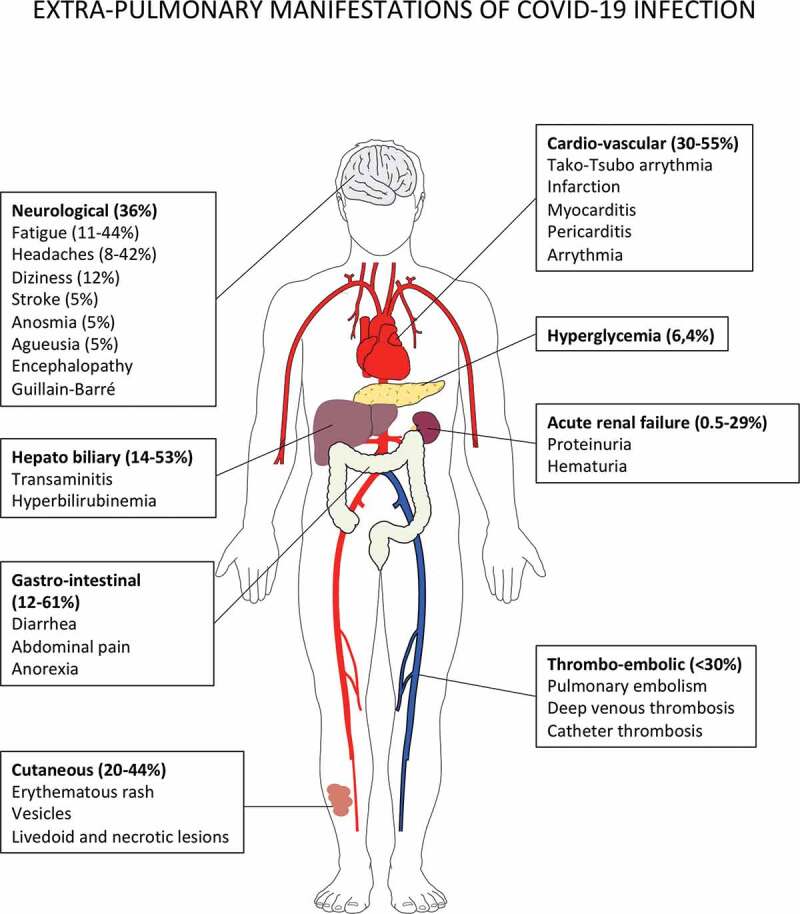

Figure 2.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19 identified in severe and critically ill patients (percentage in hospitalized patients).

Extrapulmonary manifestations are observed in one quarter to one third of hospitalized patients. Four mechanisms are involved in the pathophysiology of multiorgan injury: i. the direct viral toxicity, ii. Dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). iii. Endothelial cell damage and thrombo-inflammation and iv. Dysregulation of the immune system and cytokine release syndrome that causes disseminated organ injuries. Histopathological analyses identified the virus in the lung, the kidney, the myocardium, the brain, and the gastro-intestinal tissues.12-18 The ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression were confirmed by single cell RNA seq in epithelial cells of these organs.16,19. The entry of SARS-CoV-2 via ACE2 receptor in endothelial cells of arterial and venous capillaries generates the recruitment of innate immunosuppressive cells with pro-thrombotic features (“viral sepsis” like syndrome), favoring micro- and macro- thromboembolic events (stroke, infarction, myocarditis and pericarditis).

To tackle the COVID-19 pandemic and to reduce death rates, understanding the natural history and underlying immunological mechanisms governing disease expression is fundamental to develop preventive and therapeutic interventions. Whilst clinical features have rapidly been defined worldwide, the underlying immune responses and pathogenetic mechanisms operating in people with SARS-CoV-2 infections over time until recovery or death require further delineation. Here, we review the literature regarding human innate and cognate immune responses to SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, and relevant preclinical mouse models scrutinizing distinct molecular pathways involved in protective or pathological responses. A more comprehensive understanding of the quality of the immune responses elicited during COVID-19 infection would enable to predict the incidence of the disease, to gauge individual risks and guide prolonged containment, to better qualify convalescent serum for therapeutics, to accurately assess immuno-stimulatory versus immuno-regulatory therapeutic approaches and to generate efficient vaccines against SARS-CoV-2.

Innate barriers to viral infection paving the way to T and B cell responses

Lung parenchyma local immunity

The lung is a complex organ with specialized structures to allow for adequate gas exchange. Our understanding of the anatomical/spatial positioning, ontology, maintenance, and function of macrophages and tissue resident T lymphocytes during homeostasis and infection is still limited. Tissue-specific microenvironment can regulate the genetic landscape of macrophage populations.34 Pulmonary macrophages maintain lung homeostasis through clearance of dead cells, and invading pathogens. The lung harbors two distinct populations of macrophages, the alveolar macrophages (AMs) that arise mostly from fetal liver monocytes as well as the interstitial macrophages (IMs), which are located with dendritic cells and lymphocytes in the interstitium. In murine lung, these IMs can be subclassified into distinct populations based on their phenotype and gene signature.35,36 CD206+ IM exhibit a prominent tolerogenic and chemokine secretory profile, whereas CD206− IM have a typical antigen-presenting cell fingerprint. Of note, the IL-10 secreting function, which is a functional hallmark of lung IM, is also shared by a fraction of CD64+CD16.2+ monocytes.37 Moreover, a unique subset of IMs called “nerve airway macrophages” (NAMs), distinct from AMs by its close association with sympathetic nerves, its dependency on colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF1R), its self-renewal and its embryonic ontogeny, is crucial to mitigate viral infection through a unique IL-10 centered anti- inflammatory gene programing in vivo.38 It will be interesting to follow all these distinct subsets of macrophages during the course of COVID-19, in particular the balance between bone marrow inflammatory versus yolk sac derived-NAMs. A recent study performed single-cell RNA sequencing combined with TCR sequencing of the lung immune infiltrates obtained from bronchoalveolar lavages (BALs) in 3 mild and 3 severe patients suffering from COVID-19 as well as 8 previously reported healthy lung controls.39 BALs from patients with severe diseases contained more monocytes/macrophages. Classifying macrophage heterogeneity based on genes associated with bone marrow derived -inflammatory monocytes (centered by the Fcn1 gene encoding ficolin-1), with fibrosis (centered by the Spp1 gene encoding osteopontin), and with embryonic derived- alveolar macrophages (centered by the Fabp4 gene encoding fatty acid binding protein 4), they concluded that inflammatory monocytes expressing S100A8, S100A9, VCAN, FCN1, CD14 and CD62L were shifting towards a pro- interferon (IFN) signature (secreting chemokines such as CCL2, CCR5 and CXCR3 ligands and genes from IFN-stimulated genes) eventually associated with a pro-fibrosis differentiation pattern, more so in severe than in mild COVID-19.39 Nevertheless, analysis of gene expression is not sufficient to define ontogeny, as was recently demonstrated after human lung transplantation in patients not infected with COVID-19, where it was shown that most AMs were derived from circulating monocytes.40 The human AM population was therefore assumed to be much more dynamic and unstable than that observed in mice.40

Pulmonary macrophages, more specifically AMs, can control lung- resident memory T cells (TRMs).41 TRMs are perfectly positioned to mediate rapid protection against respiratory pathogens such as coronavirus. Animal models show that influenza-specific lung CD8+ TRMs cells are indispensable for cross-protection against pulmonary infection with different influenza virus strains.42,43 Human lungs contain a population of CD8+ TRMs that are highly proliferative and have polyfunctional progeny with influenza virus–specific CD8+ T cell TCR specificities with varying efficiencies. The size of the influenza-specific CD8+ T cell population persisting in the lung directly correlated with the efficiency of differentiation into TRMs.44 However, it is unclear whether CD8+ TRMs specific of endemic coronaviruses could be present within the human lungs and could protect to some degree against pandemic coronaviruses. Contrasting with this view, other reports claimed that in contrast to mechanisms described for other mucosae, airway, and lung parenchyma CD8+ TRMs establishment required the persistence of the cognate viral antigen recognition in situ. Systemic effector CD8+ T cells could be transiently recruited into the lung in response to localized inflammation, but these effector cells would not be able to establish tissue residency unless antigen would be maintained in the pulmonary parenchyma. The interaction of effector CD8+ T cells with cognate antigen in the lung resulted in sustained expression of tissue-retention markers (CD69 and CD103), and increased expression of the adhesion molecule VLA-1.45 This is in accordance with the preclinical work reported by Zhao et al. showing the critical role of airway CD4+ T cells recruited from the periphery by mediastinal DC and capable of proliferating locally to contain SARS-CoV infection.46 In the BAL fluids from the study described above, there were higher proportions of CD4+ and CD8+ T and NK cells in SARS-CoV-2 positive BAL than controls, and more so in mild cases.39 T cell activation, migration, calcium ion signaling and XCL1 molecules were expressed in T cells from mild cases while CD8+ T cells were only proliferative in ARDS. Moreover, pulmonary exsudates from favorable prognosis contained oligoclonal TCRs with cytotoxic and TRM molecular features.39

Pulmonary innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) play a role in mitigating immune responses to lung viral infections.47,48 Viral infection of epithelial cells leads to the activation of macrophages and DCs which secrete IL-12, IL-18 and type I IFNs subsequently activating NK cells to exert effector functions. NK cell- derived IFN-γ acts back on DCs and AMs to amplify the response. Damaged epithelium sensed by AMs releases IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP alarmins acting on ILC-2 to stimulate their proliferation and effector functions. ILC-2- derived amphiregulin promotes epithelial cell repair, while IL-9 amplifies the type 2 response in an autocrine manner. Both type I and type II IFNs produced in response to viral infection inhibit the ILC-2 response, while IL-12 together with IL-1β and IL-18 promote the conversion of ILC-2 into T-bet- expressing ILC-1- like cells.47,48 Importantly, CCR2+ monocytes control IL-22 release by ILC-3 in an IL-1β-dependent manner, and this regulation is crucial for the elimination of a pathogen invading the digestive tract.49 No data are currently available on the phenotype and functional relevance of these ILCs during COVID-19 to our knowledge.

Given the powerful immunoregulatory network in the lung parenchyma, we surmise that the myeloid cell imbalance and dysfunction may be a cornerstone of this uncontrolled tissue immune response during SARS-Cov-2 infection (Figure 3) when the lung disease clinical presentation prevails and potentially at later stages as well.

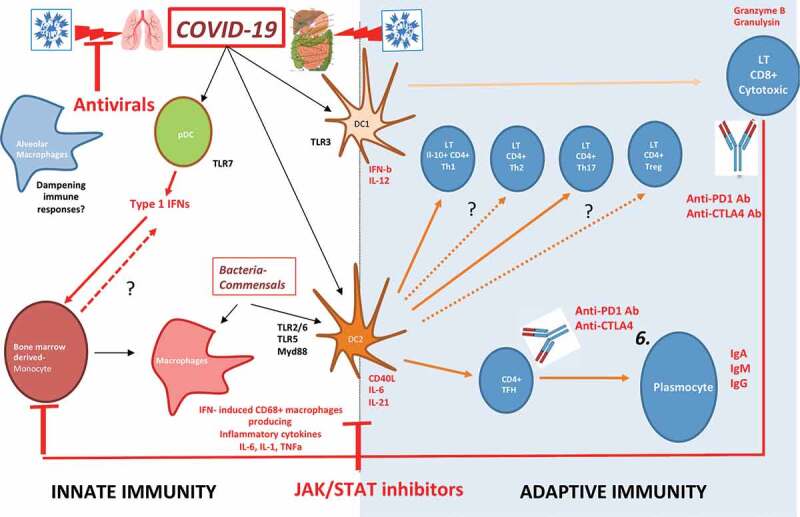

Figure 3.

Putative immune scenarios associated with protective immune responses.

Bone marrow-derived monocytes and DC precursors migrate to lung and inflammatory lesions to cross-present apoptotic virally-infected epithelial cells. Indeed, cDC1 resist to viral infection and are expected to foster CD8+ Tc1 cell responses. Plasmacytoid DC may be readily infected by the SARS-CoV-2, becoming the first source of type 1 IFNs, and contributing to the chemo-attraction and the burst of monocyte derived macrophages in lesions. cDC2 could sense and become activated by mucosal commensals/opportunistic bacteria during COVID-19, thereby inducing additional signals through DNA and RNA sensing. The appropriate orchestration of MYD88 and TRIF signaling, and other PRR in these DC subsets could contribute to the efficient priming of effector Tc1 CD8 CTL, CD4+TFH for B cell maturation leading to the resolution of COVID-19 by the eradication of virally infected cells and acceleration of lung tissue repair. The balance between TFH and TH1 cells will depend on the recruitment of cells producing IL-6, IL-21, IL-12 and expressing CD40 and ICOSL, while sustained IFN signaling might favor chronicity of the inflammation and infection rather than the elicitation of B and T cell memory responses. Lung parenchyma ILC2, IL-10 producing CTLs, tolerogenic yolk sac derived-tissue resident interstitial macrophages might mitigate myeloid crisis allowing the elicitation of DC-dependent protective CTL responses. The bioactivity and success of concomitant antivirals and therapies dampening overt TLR signaling (such as JAK/STAT, IL-6R) will likely depend on the respective kinetics of viral replication and immune responses. It is unclear to which extent T cell exhaustion is relevant at the early phase of acute infection and whether immune checkpoint inhibitors (such as anti-CTLA4/PD-1/PDL-1) could resuscitate or mitigate T cell functions.

Innate lymphocytes

Most responses of TCRγδ T cells appear to be directed against microbial pathogenic agents including bacteria, parasites, and viruses. In particular, the potent cytotoxic responses of γδ T cells against cells infected with herpesviruses or lentiviruses may be essential for the overall antiviral defense of vertebrates.50 The protective role of Vγ9Vδ2+ T cells has been analyzed during the H7N9 influenza virus outbreak as well as for the 2003 SARS-CoV pandemics highlighting variable impacts. Indeed, health care workers surviving to SARS-CoV harbored effector memory Vγ9Vδ2+ T cell subsets that selectively expanded ~3 months after the onset of disease, correlated with anti-SARS-CoV IgG titers, and displayed an IFNγ -dependent anti-SARS-CoV activity.51 In contrast, activation of Vγ9Vδ2+ T cell functions was not found during the 2013 outbreak of H7N9 influenza virus. While IFNγ producing NK cells and CD4+ TH cells were detected in patients exhibiting a late recovery (compensating their defective CTL responses at early phases of the infection), MAIT and γδT did not contrast favorable from dismal clinical outcomes.52 Almost no data are available concerning the phenotype and functions of innate effectors during SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Antigen presenting cells (APCs) (Figure 4)

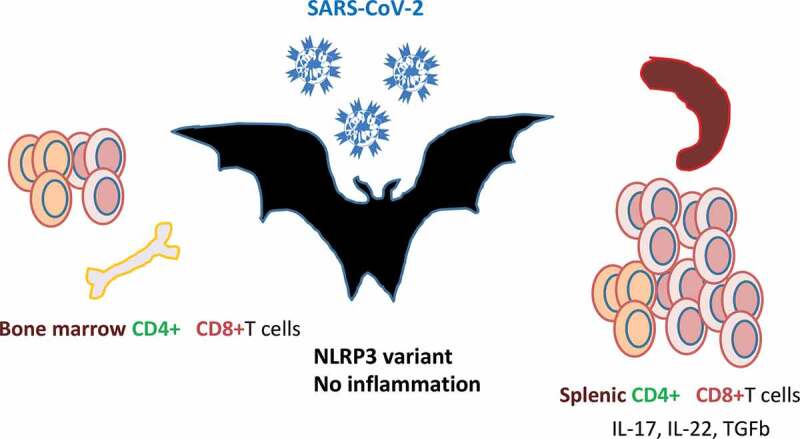

Figure 4.

Bats are the natural reservoir of betacoronaviruses: immune specificities.

Bats are increasingly recognized as the natural reservoirs of viruses of public health concern.The SARS-CoV-2 that emerged from Wuhan shared 96% identity with a bat-borne coronavirus at the whole-genome level.53 Bats primary immune cells exhibit dampened activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome compared to human or mouse counterparts, related to a novel splice variant and an altered leucine-rich repeat domain of bat NLRP3.54 Lower secretion of interleukin-1β in response to both ‘sterile’ stimuli and infection with multiple zoonotic viruses was observed with no impact on the overall viral loads. The study of the immune organs from wild-caught bats revealed a predominance of CD8+ T cells in the spleen, reflecting either the presence of viruses in this organ or the steady state. The majority of T cells in circulation, lymph nodes and bone marrow (BM) were CD4+ subsets. 40% of spleen T cells expressed constitutively IL-17, IL-22 and TGF-β mRNA. Furthermore, the unexpected high number of T cells in bats BM could suggest a role for this primary lymphoid organ in T celldevelopment.55

Classical Dendritic Cells (cDCs) are professional APCs that initiate and regulate the pathogen-specific adaptive immune responses. cDCs can be further subdivided into cDC1 and cDC2 based on their expression of cell surface markers, gene expression profile, specific transcription factors required for their development and unique functions.56 In mouse models of SARS-CoV, lung cDCs were shown to migrate to mediastinal lymph nodes in a CCR7-dependent manner to prime and expand anti-SARS-CoV specific airway memory CD4+ and effector CD8+ T cell responses, and were indispensable for viral clearance.46 APCs are affected by coronaviruses and dramatic decrease of various blood DC subsets have been reported during SARS-CoV infection, favoring profound lymphopenia.57 In vitro studies tend to indicate that epithelial cells could dampen APC functions. The apical and basolateral domains of highly polarized human lung epithelial cells infected by SARS-CoV can modulate the intrinsic functions of monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells (DC), respectively. They blunt the APC functions of DC and macrophage phagocytosis through a mechanism involving IL-6 and IL-8.58 In contrast, cDC1 (expressing CD141, CLEC9A and XCR1 in humans) resist to most viral infections, thereby maintaining their APC functions through their constitutive expression of a vesicle-trafficking protein RAB15.59,60 In addition, a discrete new population of blood circulating DC precursors (pre-DCs) shown to give rise to both cDC1 and cDC2, was recently described.61,62 Interestingly, pre-cDCs, but not other blood cDC subsets, were shown to be susceptible to infection by HIV-1 in a Siglec-1-dependent manner. Such preferential relationship of this emerging cell type with viruses advocates for future investigation whether this new DC precursor population possesses specific functional features as compared to the other blood DC subset upon CoVs encounter.

Finally, the only DC subset that could produce type 1 IFN in the context of MERS-CoV infection was the plasmacytoid DC (pDC). Human pDCs can be infected by MERS-SARS through its surface receptor CD26/DDP4, and the recycling in TLR7 expressing endosomes transduced a TLR7 -dependent signaling that culminated in type 1 and III IFNs secretion.63

Innate interferons (IFNs): a double-edged sword

Type I interferon includes IFN-α, β and ω cytokines, which are involved in the cellular antiviral response through the JAK-STAT signaling pathway and through the induction of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs).64 An impaired type I IFN response was reported to be associated with severe and critical Covid-19 infection.65 Patients with low type I IFN plasma level presented high blood viral load, an exacerbated NFκB-driven inflammatory response and increased levels of TNF-α and IL-6.65 Three mechanisms can lead to a type I interferon deficit in patients with Covid-19 disease. First, human coronavirus encode multiple structural and non structural proteins that antagonize IFN and ISG responses. The SARS-CoV papain like protease inhibits the type I interferon signaling pathway through the TRING-TRAF3-TBK1 complex.66 The MERS-CoV M protein suppresses type I IFN expression through the inhibition of TBK1 dependent phosphorylation of IRF3, and the MERS-CoV ORF 4b inhibits the production of type I IFN through direct interaction with IKK/TBK1 in the cytoplasm.3,p67) In addition, comorbidities such as obesity can inhibit IFN type I production via leptin and SOCS3.68,69 Finally, genetic factors may influence the IFN response and explain the interindividual variability in antiviral response as previously reported for severe influenzae pneumonia associated with IRF7 deficiency.70,71 It should be noted that administration of type I IFN reportedly reduced the duration of detectable virus in the upper respiratory tract, correlating with reduced blood levels for IL-6 and CRP inflammatory markers.72,73 Today, thirteen clinical trials are ongoing to evaluate the efficacy of IFN type I treatment in patients with Covid-19 infection (www.clinicaltrials.gov). Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as ssRNA, dsRNA, or viral proteins, trigger the activation of transcription factors leading to pro-inflammatory cytokines and type I IFN induction. The activation of cytoplasmic sensors RIG-I and MDA-5 triggers the upregulation of IFN regulatory factors (IRF)-3 and IRF-7, and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB) through mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein. In addition, TLRs activate the MyD88 response protein and adaptor molecule TRIF-dependent pathways, which also upregulate transcription factors IRF-3, IRF-7, NF-kB, and activator protein 1 (AP-1).74 Finally, interferon type II (IFNγ) synergizes with IFN-type 1 (IFNα/β) to inhibit the replication of both RNA and DNA viruses.

However, CoV proteins nsp 3, 4, and 6 are actively involved in the formation of host membrane vesicles and structures that affect CoV replication and evasion of the immune system by hiding the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) generated during virus replication.75 Moreover, some CoV proteins act as IFN antagonists by inhibiting its production or signaling.74,76 Indeed, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV are relatively inefficient inducers of IFN responses. SARS-CoV expresses various proteins that effectively circumvent IFN production at different levels via distinct mechanisms. For instance, SARS-CoV exploits the unique functions of proteins 8b and 8ab to overcome IRF3-mediated IFN response during viral infection.77 MERS-CoV M structural protein, & accessory ORF 4a, ORF 4b, ORF 5 proteins are also potent IFN antagonists. ORF 4a protein of MERS-CoV strongly counteract the antiviral effects of type 1 IFN via the inhibition of both the interferon production (IFN-β promoter activity, IRF-3/7 and NF-κB activation) and ISRE promoter element signaling pathways.78

Paradoxically, exacerbated or uncontrolled induction of these pro-inflammatory cytokines can also increase pathogenesis and disease severity as described for SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.74,79 Using mice infected with SARS -CoV, Channappanavanar et al., showed that viral replication is actually accompanied by a delayed type I interferon (IFN-I) signaling that orchestrates inflammatory responses and lung immunopathology and mice death.80 Type 1 IFNs remained detectable until after the peak of viral titers, and delayed IFN-I signaling promoted the recruitment of pathogenic inflammatory monocyte/macrophages, resulting in elevated lung cytokine/chemokine levels, vascular leakage, and impaired virus-specific T cell responses. Genetic ablation of the IFN-αβ receptor (IFNAR) or myeloid cell depletion protected mice from lethal infection, without affecting viral load.80 In addition, overt and sustained type 1 IFN signaling and ISG signatures compromise proper TFH differentiation and IgG responses required to survive the first phase of the viral crisis.81,82(p2) A human study profiling serum proteins and microarrays transcriptomics in 40 patients during the three phases of SARS-CoV (onset of symptoms, peak and discharge from hospital versus death) mirrored these mouse studies. Indeed, the authors revealed pathognomonic type I/II IFN responses during the acute-phase of SARS, those patients with oxygen saturation SO2>91% showed higher CXCL10 and CCL2 serum levels than those with SO2<91%.82 However, sustained and relentless IFN responses that culminated in a dysfunctional adaptive immunity (deficient anti-SARS spike antibody production) were also observed in poor outcomes.82 Chloroquine, by blocking the endosomal maturation, can reduce IFNαβ, and λ secretion by pDC and entail this type 1 IFN -related crisis.83 Therefore, we surmise that the delicate regulation between the first wave of IFN (released by pDC), followed by bona fide cDC1 expected to efficiently prime airway CD4+ Th1 and Tc1 CTL and coincide with a productive TFH/B cell dialogue, is not occurring when secondary relays or influx of IFNs producing neutrophils and monocytes are recruited and/or when IL-10 producing regulatory T cells are missing. No data are available on the protective or pathogenic role of cDCs during COVID-19 so far.

Relevant TLR signaling pathways

TLR agonists and antagonists have been discussed as potential compounds with broad-spectrum therapeutic bioactivity against a number of respiratory infections in the context of antivirals and vaccine adjuvants.84,85(p) TLR signaling through the TRIF adaptor protein protected mice from lethal SARS-CoV disease. An elegant study in Trif, Myd88, Tram, Tlr3, Tlr4 -gene deficient mice infected with coronaviruses showed that a balanced immune response operating through both the TRIF- and MyD88-driven pathways provides the most effective host cell intrinsic antiviral defense response to severe SARS-CoV disease, while removal of either branch of TLR signaling causes lethal SARS-CoV disease.86 Based on these observations, TLR agonists have been proposed as respiratory vaccine adjuvants, as well as for protection against respiratory virus-induced disease or immunopathology.87-89 Both the TLR3 agonist poly(I:C) and the TLR4 agonist lipopolysaccharide (LPS) are protective against SARS-CoV infection in mice when administered prophylactically, although poly(I:C) is more effective than LPS.85 Treatment with the TLR3 agonist poly(I:C) has protective effects in mouse models of infections by highly pathogenic coronavirus species, including group 2c (MERS-like) coronaviruses.84 TLR4 receptor has also been identified as a key pathway of acute lung injury in case of H5N1 avian flu and SARS-CoV infection.90

The right side of the janus face: protective responses based on airway CD4++ T cells and CD8++ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs)

Coronaviral infections are reportedly asymptomatic or heavily attenuated in bat populations. In wild-caught bat Pteropus alecto, there was a predominance of splenic CD8+ T cells as well as CD4+ T cells expressing TH17/TH22 -related cytokines, BCGperhaps reflecting the presence of viruses in this organ or the predominance of this cell subset at steady state (Figure 4).91 Lung macrophages and ex vivo propagatedBC DCs have high phagocytic capacities, which may regulate protective anti-viral T cell clonal expansion. Upon stimulation of TLR7, Flt3L-induced bone marrow-derived bat DCs make IFNλ2, and these cDC1-like cells exhibited strong allo-stimulatory T cell functions.55 Thus, cognate interactions between DCs and T cells may protect bats against viruses that are highly pathogenic for humans.

T cell response against coronaviruses

The significance of T cell responses to respiratory coronaviruses has been extensively reviewed.92 The acute phase of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 in humans is associated with a marked lymphopenia (80% of symptomatic patients), involving a dramatic loss of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells in comparison with unaffected individuals. Unlike MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, there is no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can infect T cells.93 Altered antigen presenting cell function and impaired DC migration resulting in ineffective priming and expansion of T cells may have contributed to the reduction of intraparenchymal virus-specific T cells.58,94 Other possible explanations for T cell lymphopenia include a sustained type I IFN response and high levels of stress-induced glucocorticoids, both contributing to T cell apoptosis.95 Chinese studies exploring >1,000 patients with COVID-19 reported that low levels of circulating lymphocytes CD4+ and CD8+ reflect COVID-19 severity.96,97

The majority of studies addressing the functional impact of T cell responses against respiratory virus infections come from mice infected with a variety of natural and mouse-adapted pathogens. Virus clearance during a primary response to infection depends on virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and the rapidity of virus clearance correlates with the magnitude of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses. Zhao et al. adoptively transferred SARS-CoV-specific effector CD4+ or CD8+ T cells into immunodeficient mice and observed rapid virus clearance and amelioration of lung infection. Priming virus-specific CD8+ T cells in vivo using viral peptide-pulsed DCs also resulted in a robust T cell response, accelerated virus clearance and increased survival in SARS-CoV-MA-15 challenged BALB/c mice.98 Similar to SARS-CoV-specific T cells, MERS-CoV specific CD8+ T cells play an important role in clearing MERS-CoV in both BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice.92 Another group II coronavirus, the murine hepatitis virus MHV-3, which causes enteritis, pneumonia, hepatitis, and demyelinating encephalomyelitis, could be kept in check by an effective Th1 (but not Th2) cell response.99

An elegant study analyzed the immune compartments in the pulmonary areas and the geographical relevance of T lymphocytes in the lung (airway, parenchyma versus vasculature) during a challenge with SARS-CoV in mice. Indeed, airway memory CD4+ T cells were the first to encounter the virus, outnumbered CD8+ T cells at sites of infection and had multiple roles in initiating and propagating the immune response.46,98,100,101 After intranasal immunization with a dominant CD4+ T cell epitope of the nucleocapsid (N) of SARS-CoV in a vector (VRP), N-specific airway memory CD4+ T cells did not exhibit the typical markers of TRMs. They expanded locally but replenished from the periphery, then acquired a polyfunctional effector phenotype and mediated an IFNγ -dependent antiviral protection after challenge with SARS-CoV. Intranasal vaccination did not increase airway TNFα, IL-1β or IL-6 cytokine levels. Instead, CD4+ T cell-derived IFNγ was associated with a prototypical type-1 IFN fingerprint (STAT-1, PKR, and OAS-1) in the lungs of these vaccinated mice, that paved the way to SARS-CoV clearance after challenge with a lethal dose of this virus. To generate robust secondary CTL responses, respiratory dendritic cells (rDCs) migrated to mediastinal lymph nodes and primed naive CD8+ T cells.59 The airway memory CD4+ T cells were indispensable for rDCs to be recruited and to prime naive CD8+ T cells. In fact, intranasal instillations of rIFNγ resulted in a 10-fold increase in the frequency of lung CCR7+ rDCs. The lung expression of the CXCR3 ligands (CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11) depended on airway CD4+ T cells and IFNγ, allowing the recruitment and activation of SARS-CoV-specific CXCR3+ CTLs that were mandatory for virus clearance.46 These protective CTLs did not express CCR4 nor CCR5, which are both known to attract undesirable regulatory or inflammatory cells. Importantly, to counterbalance overt immunostimulation and prevent immunopathology, airway memory CD4+ T cells expression of the anti-inflammatory molecules (IL-10) (along with IFNγ) was required for optimal virus clearance and mice survival.46 In fact, IL-10 was not produced by T cells in SARS-CoV-infected mice experiencing disease severity.84 Hence, this study and others indicate that airway CoV-specific CD4+ T cells provide the first line of defense against infection.102 In fact, the race between extensive viral replication in the lungs and the elicitation of an effective virus-specific CD8+ T cell cytotoxic response may dictate the final outcome in humans affected by these harmful viruses.

In SARS-CoV survivors, several HLA-A*02:01-restricted T cells recognizing SARS-CoV epitopes have been identified in the blood. Most of these immunogenic epitopes were localized to the spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) protein of SARS-CoV.103,104 Additionally, several CD8+ T cell epitopes were also identified and characterized in the M protein of SARS-CoV from PBMCs of SARS survivors.105 Peng et al., found memory Th1 CD4+ and Tc1 CD8+ T cells in the blood from fully recovered SARS individuals. These T cells rapidly produced IFN-γ and IL-2 following stimulation with a pool of overlapping peptides that cover the entire nucleocapsid N protein sequence, and persisted two years in the absence of virus. Epitope mapping study indicated that a cluster of overlapping peptides located in the C-terminal region (amino acids [aa] 331 to 362) of N protein contained at least two different T-cell epitopes.106 Similarly, Oh et al., identified the persistence of polyfunctional SARS-specific memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at 6 years post-infection. Subsequently, a dominant memory CD8+ T cell response against SARS-CoV nucleocapsid protein (NP; amino acids 216 to 225) was defined in SARS-recovered individuals carrying HLA-B*40:01.107

The clinical significance of T cell responses to other harmful viruses has been discussed in the context of survivors to previous pandemics.52,108,109 Indeed, the avian origin A/H7N9 influenza virus caused high hospitalization rates (>99%), due to severe pneumonia and cytokine release culminating in >30% mortality. Recovery from H7N9 disease was dominated by CD8+ T cell responses.108(p8) During H7N9 infection, patients presenting with a brisk and early (<2-3 weeks) CTL response specific for H7N9 influenza virus recovered faster. This cellular response was characterized by a transient peak in activated CD38+HLA-DR+PD-1+CD8+ Tc1 (IFNγ -producing CTL) cells in the context of low plasma concentrations of inflammatory cytokines.52 In contrast, the duration of hospitalization was prolonged in patients that failed to rapidly mount a CTL response or who showed a retarded (by >4 weeks) T cell expansion, dominated by CD4+ T helper (TH) cells coinciding with elevated titers of Ig and late NK cell activation.52 In fatal cases, prolonged viral exposure correlated with a pro-inflammatory profile of the serum proteins (high concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β and low IFNγ release) and minimal and exhausted T cell responses.108,110. The low frequency of peripheral CD4+ and CD8+ T cells observed in fatal cases may reflect their trapping into pulmonary inflammatory sites or lack of priming or survival capacities. Genetic defects in type 1 IFN signaling were associated with severe outcome. Patients harboring the rs12252-C/C IFN-induced transmembrane protein-3 (IFITM3) genotype, coding for a protein that restricts multiple pathogenic viruses, had faster disease progression and were less likely to survive when compared to the rs12252-T/T or rs12252-T/C genotypes.109,110

Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV) is a negative sense single-stranded RNA virus and the etiologic agent of the highly lethal 2014 Ebola virus disease outbreak, which caused 8,000 deaths in West Africa. Knowledge on EBOV has been limited by the biosafety level 4 degree of containment required to study the viral particles and patient samples. Fatal cases were characterized by a high degree of immunosuppression. The complete scenario of immune paralysis comprised high serum cytokine levels, peripheral CD95+CD4+ and CD8+ lymphopenia linked to apoptosis in human and non-human primates, as well as EBOV capacity to infect DCs and macrophages and paralyze IFN release, maturation and antigen presentation in vitro111,112 However, in survivors at the convalescent phase of this disease, robust and prolonged CD4+ Th1 and CD8+ Tc1 cell responses were observed in two waves, the second wave corresponding to the return of TRMs to the peripheral blood after control of the lung infection.113 Phenotyping of CD8+ T cells highlighted that they were not only proliferating cells but also expressing surface markers consistent with TCR engagement such as CD127low, HLA-DR+, CD38+, PD-1+, GrzBhigh, Bcl-2low, and IFNγ+TNFα+. The high level of PD-1 expression suggests that EBOV-specific CD8+ T cells are kept in check by the PD-1 inhibitory pathway.113 Several viral proteins were targeted by EBOV-specific T-cells, with the NP (and to some extent GP) being the major viral target of CD8+ T cells.113

T cell responses against SARS-CoV-2

It has been speculated that an early CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response against Sars-CoV-2 is protective, whereas a late T cell response may amplify pathogenic inflammatory responses contributing to the cytokin storm syndrome and to the lung injuries.11,114 Compared to healthy individuals, the number of T-cells were dramatically reduced in severe COVID-19 patients, especially in patient requiring intensive care unit. Total T lymphocytes, CD4+ and CD8+ lower than 800, 300 and 400/μL respectively predicted later death.115 Interestingly, T cell numbers were inversely correlated to serum IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α concentrations in severe patients, whereas resolution was associated with T-cell restauration and IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α reduction.115,116 Thymosin-α1 treatment of severe COVID-19 patients was significantly associated with a reduction of mortality, with a rebound of circulating CD4 and CD8 numbers in aged patients.117 In peripheral blood from severe COVID-19 patients, the percentage of naïve T CD4+ cells were increased, whereas the percentage of memory T helper cells were decreased together with that of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.96

In a recent high dimensional flow cytometry study, three distinct immunotypes were identified by analyzing 125 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 compared to convalescent and healthy individuals: i. a robust CD8+ and/or CD4+ T-cell activation and proliferation with a relative lack of peripheral TFH and modest activation of TEMRA-like cells as well as highly activated or exhausted CD8+ T cell with a signature of T-bet+ plasmablasts, ii. the expression Tbetbright effector-like CD8+ T cell response with a mild CD4+ T cell activation, KI67+ plasmablasts and memory B cells iii. bearly detectable lymphocyte response compared to controls that suggests a failure in the immune activation.118 The authors identified considerable inter -patients heterogeneity in those who mounted a detectable B and T-cell response within groups of increasing disease severity.118

T cell cross -reactivity

The spike protein is essential for the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with ACE2 receptor and infections of host cells. The spike protein is a homotrimer. Each protomer is composed by two subunits S1 and S2. The receptor binding domain (RBD), which is part of the S1 subunit, binds to ACE2, triggers a conformational change in the receptor and then facilitates membrane fusion.119 Robust CD4+ T cell responses against the S protein spike were identified and correlated with IgG and IgA titers.120 Numerous T and B cells epitopes were cross-reactive between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2.120 Interestingly, SARS-CoV-2 reactive CD4+ T cells were detected in 40 to 60% of individuals that had not been exposed to SARS-CoV-2.114 Cross reactive T-cell recognition between circulating seasonal coronavirus (hCoVs) (HKU1, NL63, 229E and OC43, all responsible of upper respiratory infections) and SARS-CoV-2 has been suspected to account for this pre-existing immune response.120 The T-cell specific response focused on Spike, N (nucleocapside), M (membrane) and ORFs proteins (nsp3, nsp4, ORF3a, and ORF8) and epitopes pools detected CD4+ and CD8+ in 100% and 70% of convalescent COVID patients respectively.114 Braun et al. identified S reactive-CD4+ T cells in 83% of SARS-CoV-2 positive and in 34% of negative patients. Whereas CD4+ T cells from COVID-19 patients equally targeted the N and C terminal regions of the S protein, CD4+ T cells from healthy volunteers only targeted the C terminal region, which has a high homology with the S protein of seasonal coronaviruses.121 Of note, S-reactive CD4+ T cells from COVID-19 patients co-expressed CD38 and HLA-DR indicative for their recent in vivo activation, at difference with CD4+ Tcells from healthy volunteers.121 Finally, Le Bert et al. identified the NSP-7/13 specific T-cell as dominant in SARS-CoV-1/2 unexposed donors, a consistent result with Griffoni’s observation who identified ORF-1 specific T-cell response in unexposed SARS-CoV-2 specific donors.122 Since the ORF-1 region contains highly conserved domains among the different coronaviruses, periodic human contact with ORF-1 can therefore induce a specific response of T cells that react with the SARS-CoV-2.114,122 In addition, it has been shown that the T-cell memory response can last up to 17 years after SARS-CoV infection, suggesting the existence of long-term protective cross-immunity.122 However, whether the crossreactivity of TCR reacting against hCoVs or SARS-CoV confer protective cellular immunity against SARS-Cov-2 remains to be demonstrated.

Based on epidemiological reports identifying fewer confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 in countries implementing BCG vaccination, it has been postulated that “trained” immunity induced by BCG adjuvants could confer protection against SARS-CoV-2.123-127 BCG vaccination has been shown to increase the immunogenicity of influenza virus-based vaccine and reduce acute lower respiratory tract infections in children.127,128 Across 55 countries, BCG significantly mitigated the spread and severity of the COVID pandemic-19109. Potentiation of innate immune responses and/or T-cell-mediated cross-reactivities were suspected in these protective effects. Nonetheless, a recent epidemiological study did not support this hypothesis.129 There is an ongoing Phase III trials testing BCG to promote trained innate immunity.130

Given the general clinical significance of T cell responses to harmful viruses (coronaviruses but also EBOV, H7N9 avian influenza virus), we could surmise that effector memory CD8+ T cells will be crucial for the elimination of and protection against SARS-Cov2.52,108,109 All these clinical and preclinical observations urge investigators to design vaccine strategies capable of eliciting protective virus-specific Tc1 immune responses. Preclinical DNA-based immunization strategies identified dominant CD4+ and CD8+T cell epitopes located in the receptor-binding domain of SARS -CoV S protein.131 The route of immunization matters for the expansion of the most reactive lung airway CD4+ T cells. Intranasal vaccination with Venezuelan equine encephalitis replicons (VRP) encoding a SARS-CoV CD4+ T cell epitope from the N nucleocapsid induced airway CoV-specific memory CD4+ T cells that efficiently protected mice against lethal disease through rapid local IFNγ production while the subcutaneous route was not as efficient.46 Cross-protection between endemic and pandemic coronaviruses is obviously advantageous. The epitope used in murine studies was presented by human leukocyte antigen HLA-DR2 and -DR3 molecules, and mediated cross-protection between SARS-CoV N353 and its homolog in MERS-CoV, HKU4 N and related bat CoVs. In line with another study conducted in SARS survivors, this work suggests that this epitope is likely to be useful as an immunogen in human populations.106,107 Future efforts will determine which precise MHC class I and II-restricted epitopes confer a broad antigenicity across multiple HLA haplotypes for the generation of efficient vaccines and the follow up of long-term protective immunity against SARS-CoV2 (See next chapter). The T cell response plays a critical role in orchestrating the antiviral response since a close relationship between TCR diversity and the immune response to viral antigen has been reported.132 Under homeostatic conditions, the TCR repertoire is diverse and polyclonal. The question remains whether, in the case of SARS-CoV-2 viral infection, T cell clones may contribute to narrowing the TCR repertoire selected by the antigen.132

The potential relevance of B cells, TFH and humoral immune responses (Figure 5)

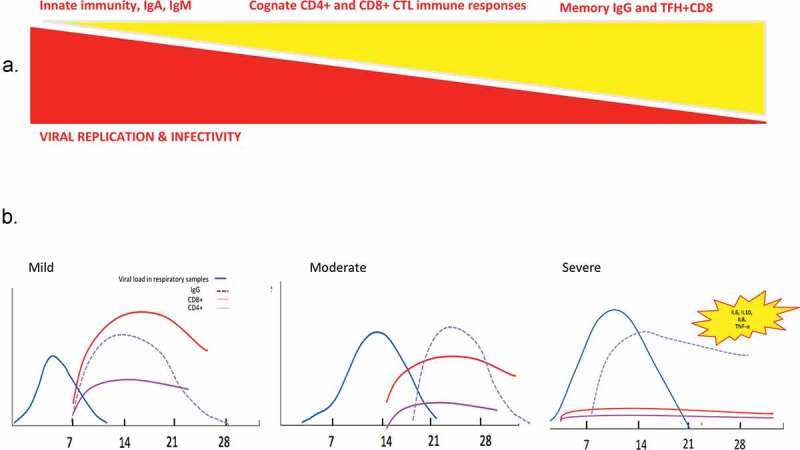

Figure 5.

Race between viral replication and immune responses during viral infection with SARS-CoV viruses.

Theoretical principles (A) and tentative scheme (B) of the kinetics of virus replication and infectivity, humoral and cellular immune responses, based on previous human pandemic infections with betacoronaviruses.

B cell responses

In cases of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, significant B cell lymphopenia was unevently observed.96,133,134 Mathew et al. identified a subgroup of severe hospitalized patients with a immunotype characterized by T cell activation and plasmablast responses >30% of circulating B cells.118 Critically ill patients with COVID-19 accumulated cells exoding from germinal centers, produced of a considerable number of antibodies secreting cells and lose unique transitional B cell populations that correlated with good prognosis.135 B-1a cells have been shown to play a crucial role in the immune response against SARS CoV-2 by producing immunoglobulins that confer protection against progression from mild disease to ARDS.136 In the unicellular atlas of peripheral immune response to severe COVID-19 infection, an increased proportion of plasmablasts has been identified in patients with ARDS, suggesting that more severe cases may be associated with a greater humoral immune response.137 Since plasmablasts are rarely detected in the blood of healthy patients, their high frequency in COVID-19 blood samples suggests pro-active humoral responses.137 Next generation sequencing of the T and B cell receptors identified a signature associated with the severity of the disease in which B cell response showed converging IGHV3-driven BCR clusters closely associated with SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.138

TFH cells (follicular helper T cells)

TFH cells (follicular helper T cells) are essential for antibody-mediated humoral immunity against various pathogens in rodents. After viral infection, TFH cells facilitate the generation of long-lived memory B cells and plasma cells that produce virus specific neutralizing antibodies. Virus-specific TFH cells, characterized by high expression of chemokine receptor CXCR5 and Bcl6, mTORC2 and TCF1 transcription factors in mice, are endowed with the ability of migrating into B cell follicles in response to chemokine CXCL13, where they facilitate the maturation of germinal center (GC) B cells by interacting with cognate virus-specific B cells and providing “help” signals such as IL-21, IL-4, CD40L and inducible costimulatory molecules (ICOS).139 Upon acute viral infection, virus specific CD4+ T cells mainly differentiate into Th1 and TFH cells, (rather than Th2, Th17, and Th9 in the context of IFNs and “type 1-like” inflammation). The divergence between TFH (Bcl6+Blimp1neg) versus Th1 (Bcl6negBlimp1+) differentiation fates begins immediately after activation. IL-6 and IL-21 play a critical role tilting the balance towards TFH by influencing the phosphorylation of STAT3 governing the upregulation of Bcl6, while IL-2, through phosphorylation of STAT5 influences the upregulation of Blimp1 culminating in Th1 polarization. Memory TFH maintain high expression of CXCR5, FR4 and CD40L, but lose Bcl-6, ICOS, PD-1, and Ly6c while acquiring CCR7, CD62L and IL-7Rα, and are retained in the draining lymph nodes to ensure faster antibody production of neutralizing antibodies against potentially new viral variants.139,140 During chronic viral infection, there is a major shift towards TFH differentiation at the expense of Th1 cells, stimulated through type 1 IFNs and IL-6/IL-27. TFH maintained their pathognomonic transcriptional profile, centered by IL-21 (crucial for CD8+ T cell triggering), with high expression of PD-1 and CTLA4 exhaustion markers. Moreover, there is a dysregulated TFH/B cell interaction, leading to delayed, reduced and poor-quality production of Ig, coinciding with the presence of regulatory Foxp3 TFH. It is unclear whether SARS-CoV-2 can directly infect TFH or impact their differentiation and exhaustion patterns in the context of prolonged and sustained IFNAR signaling, and what impact could PD-1/CTLA4 blockade may have in accelerating a productive TFH/B cell interaction at the early stages of COVID-19 for long-term protection against this virus. There is a need to study this TFH cell subset in the blood of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 at different kinetics of the ongoing immune response, since peripheral TFH can be followed in the blood.141 One case report discussed the relevance of a peculiar subset of CD4+ T cells, follicular T helper cells (TFH cells) that were paralleled by a raise in effector CD8+ CTL announcing the resolution of the COVID19 in one pauci-symptomatic Chinese woman.142 Prior to recovery, there was an increase of circulating antibody secreting cells (ASCs), follicular helper T-cells (TFH cells), activated CD4+ T and CD8+ T and IgG and IgM bounding the SARS-CoV-2 virus detectable by day 7 and persisting during 7 days following full resolution of symptoms.142 Co-expression of CD38+ and HLA-DR CD8+ T-cells rapidly increased from day 7 to day 9, at higher levels than in healthy controls and decreased at day 20.

The humoral response against coronaviruses

The quality of the Ig production makes a difference for the long-term immunization against harmful viruses. Antibodies undergo an intricate process of adaptation to the viral antigens i.e., affinity maturation. In a Darwinian-like manner, B cells harboring somatic mutations that increase affinity for the antigen give more progeny with an enrichment in high affinity somatic variants across the subjects.143 Sporadic differentiation of germinal center B cells into antibody secreting plasma cells accounts for the progressive improvement of antibody titers over time. The extent to which affinity maturation is required for the generation of protective and neutralizing antibodies varies from virus to virus. The natural serologic response to EBOV infection has been well-characterized, with specific IgM responses generally occurring 10–29 d after symptom onset in most patients. Ebola virus-specific IgG responses occurred ~19 d after symptom onset in most individuals.144,145 Serological responses to EBOV have been reported as absent or diminished in fatal cases. While for influenza virus, low affinity antibodies emerging early after infection can be protective, EBOV infection generates highly protective neutralizing antibodies late (after 1 year) in survivors, once EBOV-specific B cell lineages have acquired substantial somatic mutations, although potent antibody responses monitored at earlier phases that may not necessitate mutations may confer some protection albeit directed toward different epitopes (cleaved-as opposed to naive- surface glycoprotein found at late time points). The N protein is conserved among different coronaviruses and induces cross-reacting antibodies.146 However, N-specific sera failed to neutralize the viruses.46,147 Neutralizing antibodies induced by the S glycoprotein provided complete protection against lethal CoV infections.148 Moreover, an inverse correlation was observed between IgA secretion and MERS-CoV infectivity in patients, suggesting that virus-specific IgA production may be a suitable tool to evaluate the potency of candidate vaccines against MERS-CoV.149 However, the anti-SARS-CoV antibody response, particularly the IgA response, was short-lived in patients who have recovered from SARS. Indeed, SARS-CoV-specific memory CD8+ T cells persisted for almost 6 years after SARS-CoV infection when memory B cells and antivirus antibodies had already become undetectable.150

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies

Seroconversion during COVID-19 occurs at the same timing as the one described post- SARS-CoV infection.151 Analyzing 208 plasma from patients with a high suspicion of COVID-19 infection using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) specific for recombinant viral nucleocapsid protein, Guo et al., found that IgM and IgA were detected by day 5 in 85% and 93% cases, respectively, while IgG could be measured by day 14 in 77% individuals after the onset of symptoms.152 The detection efficiency of the IgM ELISA was higher than that of qRT-PCR method after 5.5 days of symptom onset. The success rate for screening detection of COVID-19 using the combination of IgM ELISA and qPCR outperformed that of qPCR alone (98.6% versus 51.9%).152 In an independent study, Liu et al., tested the sera of a large series of confirmed COVID-19 patients with two ELISAs based on recombinant SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein (rN) and spike protein (rS) to detect IgM and IgG antibodies.153 Among the 214 patients tested, around 68% and 70% were successfully diagnosed with the rN-based IgM and IgG ELISAs, respectively; while around 77% and 74% were positive with the rS-based IgM and IgG ELISAs, respectively. The sensitivity of the rS-based ELISA for IgM detection was significantly higher than that of the rN-based ELISA, mostly after day 10 of disease onset. In a small European study, seroconversion was detected by IgG and IgM immunofluorescence using recombinant cells expressing the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, as well as by a SARS-CoV-2 virus neutralization assay. Seroconversion occurred in 50% of patients by day 7 (when no virus was isolated) and in all individuals by day 14. All patients showed detectable neutralizing antibodies. There was no obvious correlation between the time of seroconversion and abrupt virus elimination. This may be explained by the glycosylation pattern of the viral surface proteins that may attenuate the neutralization potential of the antibody response, as described in the case of EBOV infection. Rather, seroconversion early in week 2 coincided with a slow but steady decline of sputum viral load.154 Liou et al. reported that an increase in antibody levels was accompanied by a decrease in viral load suggesting that such antibodies have an antiviral activity.155

The use of a reliable serologic test is necessary in clinical practice to detect asymptomatic COVID-19 cases that have healed on their own, to estimate the seroprevalence of the disease in the general population, and to identify the presence of a serologic response as protective against SARS- CoV-2 reinfection. Serological tests are currently under development to detect present or past COVID-19 infection.155,156 Humoral responses against SARS-CoV-2 are characterized by 3 critical points. Seroconversion begins on the sixth day after the onset of symptoms and peaks in the second week, as usually reported for viral infections.155 The seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in known infected patients is heterogeneous and varied from 47 to 100%, depending on the tests and target populations.155-157 The third interesting point is that several studies agree that early and high levels of anti SARS-CoV-2 antibodies are associated with severe diseases.156-158 This questions the potential deletorious role of these antibodies. In a macaque model, Liu et al. showed that anti spike IgG cause severe acute lung injury. The presence of S-IgG prior to viral clearance abrogated the wound-healing response and promoted MCP1 and IL-8 production, as well as the accumulation of proinflammatory monocytes/macrophages in the lung.159

Serological cross -reactivity and neutralizing antibodies

The SARS-Cov2 nucleocapsid and S genes share some degrees of sequence homology with other human coronaviruses.152 Importantly, SARS-CoV elicited polyclonal Ab responses potently neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 S-mediated entry into cells. It is likely that most of these Abs target the highly conserved S2 subunit (including the fusion peptide region) based on its structural similarity across SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV, the lack of cross-reactivity of several SB-directed Abs. As the SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV SB domains share 75% amino acid sequence identity, future work will be necessary to evaluate whether any of these Abs neutralize the newly emerged coronavirus.160 Hence, neutralization testing is therefore necessary to rule out cross-reactive antibodies directed against endemic human coronaviruses. Technical progress is being made to circumvent this cross-reactivity.88,161 Krammer’s group developed a sensitive and specific ELISA to detect neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 using two different versions of the S protein, the full length trimeric and stabilized version of S protein and the much smaller receptor binding domain (RBD). Reactivity of COVID19 sera was stronger against the full-length S protein than against the RBD. The isotyping and subtyping ELISA was also performed using S proteins expressed by insect and mammalian cells. Strong reactivity was found for all samples for IgG3, IgM and IgA. An IgG1 signal was also detected for 3/4 samples. No signal was detected for IgG4 and reagents for IgG2 were unavailable. Altogether, the antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 is poorly neutralizing. In a recent study, Robbiani et al. showed that high levels of neutralizing antibodies were rarely observed (1:1,000 in 79%, while only 1% showed titers above 1:5,000), whereas rare but recurring RBD specific antibodies with potent antiviral activity were found in all recovered patients 39 days after the onset of symptoms.162

Plasma therapy

The neutralizing power of IgG has been evidenced by the use of convalescent plasma in severe viral infections during SARS, H5N1, H1N1, Ebola pandemics, and anecdotally against MERS-CoV infection.163-169 Clinical trials with convalescent sera as therapeutics have been initiated in China (e.g. NCT04264858), and anecdotal evidence from the epidemic in Wuhan suggests that compassionate use of these interventions was successful. Five cases of COVID-19 infection were reported. Three patients were discharged from the hospital in good medical conditions on the first day post- transfusion.163 Duan et al., also reported the effectiveness of convalescent plasma in 10 cases. Seven days after the transfusion, increased levels of neutralizing antibodies were observed while viral load became undetectable.170

Vaccination

Preclinical studies in rodents tested a modified form of the SARS-CoV-2 spike gene in place of the native glycoprotein gene into replication-competent vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-based vaccine.171 Immunization of mice with VSV-eGFP-SARS-CoV-2 conferred high levels of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies that neutralized viral infection by targeting the receptor binding domain that engages ACE2 receptor.171 Reduced viral infection and inflammation were observed in vaccinated mice. In addition, sera from VSV-eGFP-SARS-CoV-2-immunized animals conferred protection to naïve mice.171

In human, a recombinant adenovirus type-5 vectored COVID-19 vaccine was tested in an open label, non randomized, first human trial.172 One hundred and eight patients (36 in each groups) received low, middle or high dose of the vaccine.172 Neutralizing antibodies were detected at day 14 and peaked at day 28 post infection proving that the Ad5 vectored COVID-19 vaccine is tolerable and immunogenic 28 days post vaccination.172 Next to that phase1/2 of BNT162b1, a lipid nanoparticle-formulated, nucleoside-modified, mRNA vaccine that encodes trimerized SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein RBD was tested in 45 randomized participants.173 Twenty-one days after the first injection, a modest increased in SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was observed.173 In addition, a Phase I vaccine trial, based on intramuscular administration of the prominent and novel lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-encapsulated mRNA-1273 that encodes a full-length, perfusion stabilized spike (S) protein is ongoing.174 Fourty-five healthy donors divided into 3 groups of 15 were included to receive two vaccinal doses (25 μg, 100 μg, or 250 μg in each group respectively). Preliminary results showed the detection neutralizing activity in all participants after the second dose vaccination.174 Twenty-one percent of the participants in the 250 μg reported adverse effects after the second dose.174 Neutralizing antibodies were observed for all doses (10 μg and 30 μg) and greater serum neutralizing antibodies were observed 7 days after a second dose, while the kinetics and durability monitoring of these antibodies is ongoing.174

Likewise, a wide range of vaccine candidates have been developed against these coronaviruses, including subunit, whole inactivated virus, DNA, and vectored vaccines.175-178 However, these vaccines were found to induce antibody-dependent enhancement of infectivity and eosinophilia. In contrast, live-attenuated vaccines have a long history of success. Attenuation of viruses generally relies on the previous identification of genes involved in viral virulence in specific hosts, often encoding proteins that antagonize the innate immune response. Their deletion leads to viruses that are attenuated in their virulence and, therefore, may be developed into candidate vaccines.179,180

Monoclonal antibodies

The development of antibodies protecting during Sars CoV-2 infection is an urgent public health and vaccine development issue. The majority of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients generate antibodies specific for S protein and RBD.119 A human monoclonal antibody, 47D11, prevents the replication of both SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV in vitro by binding with similar affinity to the conserved epitope S1b present on the RBD spike protein of both viruses.181 The CR3022 human antibodies that neutralizes SARS-CoV also binds the RBD of SARS-CoV-2.182 Targeting a distinct epitope than CR3022, the S309 antibody was shown to crossreact between the two viruses, SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV.183 Nonetheless, there are only few cases in which antibodies truly neutralize the virus. Analysing plasma sample from patients infected with SARS-CoV and Sars-CoV-2, Lv et al. identified limited cross-neutralization by antibodies recognizing conserved epitopes in the spike protein.119 Of note, a human monoclonal antibody was able to neutralize SARS-CoV and Sars-CoV-2 in vitro.181 In fact, the Sars-CoV-2 Spike protein is similar to that of the SARS-CoV since 77.5% of their primary amino acid sequence are identical. The S1b domain of this protein commonly binds the human angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).181 Whether such antibodies arise in patients at doses sufficiently hight to protect against viral spread in vivo is an open question.

Dogan et al. identified a 3000-fold higher antibody and neutralization titers in hospitalized patients compared to outpatients or convalescent plasma donors.184 Analyzing 4313 SARS-CoV-2 reactive B-cells, 255 antibodies were isolated with a broad spectrum of variable (V) and a low level of somatic mutation,185 28 of them have potentially neutralizing properties. As potential precursor sequences have been identified in the naïve B-cell repertoire of 48 healthy individuals, SARs-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies can easily be generated from a diverse set of precursors.185

The wrong side of the janus face: virus-induced immunopathology

Balancing immune-mediated virus clearance and overt immunopathology may be difficult in certain patients. Higher serum levels of the cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-2R, IL-10 and the chemokine IL-8 were found in patients with severe COVID-19, whereas these cytokine levels were within the normal range in moderate cases.96 In severe cases, bronchoalveolar lavages revealed interstitial mononuclear infiltrates dominated by lymphocytes, pulmonary edema, hyaline formation and pneumocytes desquamation. These pathological features of COVID-19 resemble those observed in SARS and Middle Eastern Respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV).186-188 In a case report diagnosed with ARDS, peripheral CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were substantially reduced, albeit exhibiting a hyperactivated status, as evidenced by the high expression of IL-17 and HLA-DR in CD4+ T cells and CD38+ in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Of note, CD8+T cells harbored high contents in perforin and granulysin containing cytotoxic granules.186 As already reported during overt H7N9 viral infection, the severe immune injury manifested in this patient likely resulted from over-activation of T cells.186 In mouse models, T cells could cause lung immunopathology, depending on the virus and the mouse strains.189,190(p4) Trandem et al., showed that IL-10 produced by CD8+ T cells diminished disease severity in mice with coronavirus-induced acute encephalitis, suggesting a self-regulatory mechanism that minimizes immunopathological changes.191 Sun et al., re-enforced this notion in an acute influenza infection showing the IL-10 dependent- anti-inflammatory property of antiviral CD8+ and CD4+ effector T cells (Teff cells) in the infected lungs and in the periphery.192 Besides IL-10 producing T cells, Foxp3 regulatory T cells may also protect the host against overt inflammation, notably in models of murine hepatitis virus (a group II murine coronavirus) MHV-induced encephalomyelitis.193 So, an orchestrated airway CD4+ T cell responses, mediastinal DC migration leading to proper CD8+ T cell priming, proliferation and IL-10 producing Tc1 polarization may be crucial to prevent T cell apoptosis, failure and exhaustion and to keep in check SARS-CoV receptor ACE2 expression.194 Alternatively, by binding to ACE2, the virus promotes the accumulation of its natural ligand, angiotensin II, in the tissue environment, unleashing the renin angiotensin system. Interestingly, T lymphocytes express the angiotensin II receptor AT1R, and signaling through AT1R in T cells unleashed their effector and memory functions during cognate interactions, as described in AT1R deficient transgenic CD8+ T cells in a mouse model of malaria.195

Lymphopenia

In contrast to exacerbated T cell activation, T cell exhaustion could represent the cause of this inflammatory syndrome. In COVID-19, T lymphocytes failed to produce TH1 cytokines, to accumulate cytolytic granules and expressed high levels of NKG2A inhibitory receptor.196 Hence, overt recruitment of activated monocytes to lung lesions could be the main driver. Stressing the relevance of possibly exhausted CD8+ T cell functions in the uncontrolled monocyte activation and cytokine release syndrome, Liu et al., recently described how systemic PD-1 blockade could mitigate the hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) syndrome in patients suffering from EBV-induced HLH.197 In EBV-induced HLH, single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis revealed that HLH syndrome was associated with hyperactive monocytes/macrophages (expressing high levels of CD163, IL-1β, IL-6) and ineffective CD8+ T cell response characterized by a defective activation program (apoptosis, reduced TCR signaling, lower IFNγ/GrzB/Ki67 and higher PD-1/LAG3 exhaustion markers).197 SARS-CoV2 -induced secondary HLH could be observed in severe cases of COVID-19.32,198,199

Mechanisms leading to peripheral lymphopenia and severe disease remain unclear. Three non-exclusive hypotheses have been emitted. First SARS-CoV-2 might directly infect and the destroy splenic and lymph nodes follicles, as indicated by the post mortem analysis of 6 patients.200 Second, activated lymphocytes might be sequestered in the injured tissues, especially in the lung.186,201 Third, the production of lymphocyte precursors by the bone marrow and the thymus might be exhausted.202

Endothelial cell injury

In SARS-CoV-2 infection, 72% of non survivors have evidence of hypercoagulability.203 Dehydration, an acute inflammatory state, prolonged immobilization during illness and a medical history of cardiovascular disease increase the risk of thromboembolism.204 Hypertension, aging, diabetes and obesity are co-morbidities impairing endothelial cell metabolism and contributing to COVID-19-related death. Furthermore, the increased incidence of Kawasaki disease in young children with COVID-19 infections, even in the absence of cardiovascular predisposition, is indicative of SARS- CoV-2 vascular tropism and vascular damage.205 According to the Virshow Triad, abnormalities of the vascular endothelium, altered blood flow and abnormal platelet function lead to venous and arterial thrombosis in the event of COVID-19.206

Pathological analysis have shown diffuse microthrombi surrounded by CD4+T cells, macrophages and significant hemorrage called immunothrombosis.207,208 Excess soluble fms-type tyrosine kinase-1 has been shown to promote endothelial dysfunction and the incidence of organ failure in patients with COVID-19.209 The most common initial hemostatic abnormalities observed in severe patients are mild thrombocytopenia, increased fibrinogen and D-dimer.210 Elevation of D-dimers on admission is associated with increased mortality.210 Endothelial dysfunction, activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) with the release of a procoagulant plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1), and hyperimmune response with platelet activation are important factors in the thrombogenesis of COVID-19.206 This is evidenced by the ACE 2 receptor on vascular endothelial cells, the presence of viral inclusion in endothelial cells and by endothelitis.211,212 In severe COVID-19 patients, endothelial cells exhibited characteristics of inflammation, cells dysfonction, lysis and death.209,213 Endothelial injured cells were shown to secrete Von Willebrant Factor (VWF), which activated platelets, and favor their aggregation contributing to blood coagulation.213-215 Mortality was significantly associated with the detection of the VWF antigen in COVID-19 patients.213 In response to the virus invasion, endothelial cells release IL-6 that amplify the host immune response even to the state of the cytokine storm syndrome.204,206,216

Hence, pulmonary complications result in part from endothelitis, activation of coagulation and myeloid pathways, maybe calling for therapeutics targeting angiopoietin-2, bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds VEGF and counteracts its vessel permeabilizing effect.217

Immature neutrophils and the cytokine storm

Recent studies revealed that emergency myelopoiesis marked by the occurrence of pre-neutrophils and immature neutrophils is correlated with the severity of the disease.218 Thus, profound alteration in the peripheral myeloid cell compartment is associated with severe COVID-19 infection.218 Immature neutrophils have immunosuppressive properties that may promote the spread of infection, immunothrombosis and the deterioration of sepsis i.e low phagocytosis capacity, tumoricidal activity of T cells, spontaneous release of extracellular neutrophil traps that promote endothelial damage and hypercoagulation.219-221 The cytokinemia, mainly IL-6/sIL-6Ra and IL-6-induced IL-8 release can all participate in the bone marrow demargination of neutrophils. Neutrophils are rapidly attracted to the lung parenchyma following the local burst in inflammatory cytokines/chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL8, CXCL10, CCL2), likely as the consequence of viral replication and IFNAR signaling in epithelial cells. In mouse models in which coronavirus replication is increased by genetic defects in innate lines of defense (such as TRIF, TLR3, TLR4, C3, NLRP3 deficiencies), increased weight loss and fatality are associated with excess recruitment of neutrophils and monocytic cells to the lung, correlating with acute respiratory distress syndrome.222-224(p9) “Immuno-thrombosis” appears to be initiated by neutrophils. Neutrophils facilitate trapping and killing of pathogens through an organized cell death pathway in which decondensed chromatin and antimicrobial proteins are expelled from the cell to form Neutrophils Extracellular Traps (NETs).225-230 Preclinical studies performed in a murine inferior vena cava stenosis model demonstrated the contribution of neutrophils and NETs in this thrombosis.231 It will be interesting to elucidate whether the neutrophils-NET hypothesis is a cause or consequence of the COVID-19 -associated coagulopathy, whether it is upstream or downstream the IL-6R signaling and whether it could be drug targetable. In severe COVID-19 patients, the anti-IL-6R antibody Tocilizumab (TCZ) attenuated the over -activated inflammatory syndrome.232 While meta-analyses of IL-6R blockade in rheumatoid arthritis patients revealed that the reduction of neutrophils counts was a key pharmacological hallmark of TCZ, current trials in COVID-19 should shed more light on its bioactivity on lung immune infiltrates and severity of pneumonia.233 The presence of highly expanded clonal CD8+ T cells in the lung microenvironment of mild symptom patients suggested that a robust adaptive immune response is connected to a better control of COVID-19 under TCZ.39

IL-6

Several studies reported that tocilizumab, a antibody that neutralizes the IL-6 receptor, improved the outcome of severe COVID-19. The first anecdotic report identified a favourable course of treatment with tocilizumab (TCZ), while the first cohort study reported that 3 of the 10 treated patients died (perhaps because TCZ was used in combination with methylprednisolone).234-236 IL-6 levels tend to decrease after TCZ treatment.236 More recently, treating 100 patients with COVID-19 infection, among which 43 were recovered in ICU, Toniati et al. reported that respiratory conditions improved in 77% of the cases.237 Finally, in a prospective monocentric study, 21 patients with severe COVID-19 infection were treated with TCZ. Fever resolved one day after administration and 15 out of 21 patients (75%) required less oxygen within 5 days of tocilizumab administration.238 CT scan-detetecable lung lesions regressed and peripheral lymphocytes cell counts returned to normal in 52% of the patients 5 days after the initiation of the treatment. This is the first cohort study reporting strong promising results. Interestigly, all these studies reported improvement of CT scans and CRP but lacked control groups. In addition, progression to secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis was reported for severe COVID-19 patients presenting a cytokine release syndrome under tocilizumab treatment.239 Gastrointestinal perforations were also recently reported under tocilizumab treatment.240 Therefore, it is difficult to evaluate the clinical efficacy of TCZ.

Conclusions

The knowledge accumulated so far on the most lethal human coronavirus pandemics – particularly SARS-CoV and CoV-2 and MERS-CoV, points to the critical impact of a poly-functional CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses, perhaps re-enforced by early IgM and IgA and later, IgG responses to fight against the virus and win the race against its overt replication in the lungs (Figure 5). While it appears clear that T lymphocyte responses can confer effective and durable protection against SARS-CoV-2, the role of humoral responses is still elusive. Paradoxically, the mortality rate associated with COVID19 is mainly the result of a dysregulated immunopathology in response to the virus rather than organ injury due to the viral replication itself. At present there is little knowledge on the source of overt inflammation, although geared toward bone marrow derived-monocytes or myeloid and hematopoietic (neutrophil) precursors (“viral spesis”), and a putative positive feed-back loop through vascular endothelial cells and coagulopathy without operational counter-regulatory mechanisms (likely mediated by pulmonary ILC-2, local regulatory TRMs, IL-10 producing T cells, effector memory killer CD8+ T cells).

There is an urgent need for a high dimensional and longitudinal follow-up of the underlying immunological mechanisms across the different stages of the COVID-19 to make more rational and personalized therapeutic decision. Consortia aimed at patient stratification and appropriate clinical management are being constituted to bring together the required expertise to reach this goal in short term. Importantly, pilot and large clinical trials based on antivirals, immunostimulatory and immunosuppressive drugs are being conducted for early and late stages of COVID-19 in hospitals of these consortia, awaiting diagnostic tools to optimally stratify patients according to their risk. The race between viral replication and the elicitation of a productive and coordinated immune response likely necessitates drugs that operate on those sides (likely as a result of off-target effects) or combinatorial regimen.