SUMMARY

A G4C2 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in an intron of C9orf72 is the most common cause of frontal temporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (c9FTD/ALS). A remarkably similar intronic TG3C2 repeat expansion is associated with spinocerebellar ataxia 36 (SCA36). Both expansions are widely expressed, form RNA foci, and can undergo repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation to form similar dipeptide repeat proteins (DPRs). Yet, these diseases result in the degeneration of distinct subsets of neurons. We show that the expression of these repeat expansions in mice is sufficient to recapitulate the unique features of each disease, including this selective neuronal vulnerability. Furthermore, only the G4C2 repeat induces the formation of aberrant stress granules and pTDP-43 inclusions. Overall, our results demonstrate that the pathomechanisms responsible for each disease are intrinsic to the individual repeat sequence, highlighting the importance of sequence-specific RNA-mediated toxicity in each disorder.

In Brief

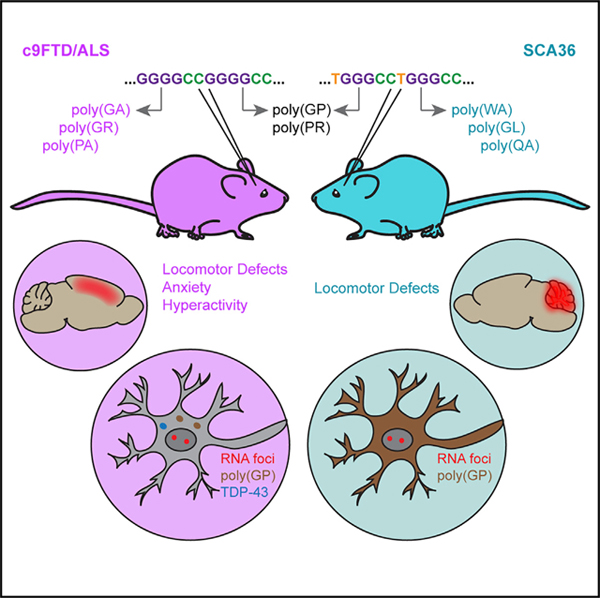

c9FTD/ALS and SCA36 are distinct diseases associated with similar hexanucleotide repeat expansions: G4C2 versus TG3C2. Todd et al. show that expressing these repeats in mice is sufficient to recapitulate each disease. The pathology and selective neurodegeneration characteristic of each disorder are therefore due to pathomechanisms intrinsic to each repeat sequence.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The phenomenon of selective neuronal vulnerability has long been a question in the field of neurodegenerative disease research. If a toxic entity is widely expressed in the brain, why do only certain neurons die, whereas others survive? This question becomes more complicated in diseases that are characterized by multiple potentially toxic pathologies. A prime example of this is frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). FTD is associated with the loss of cortical neurons in the frontal and temporal lobes, whereas ALS is caused by the progressive degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons. The most commonly known genetic cause of both of these diseases is the expansion of a G4C2 hexanucleotide repeat in intron 1 of Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72) (DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Renton et al., 2011). The expanded repeat accumulates into RNA foci that can be detected throughout the central nervous system (CNS) (CooperKnock et al., 2015; DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Mizielinska et al., 2013), and undergoes repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation to produce dipeptide repeat proteins (DPRs) that aggregate in neurons (Ash et al., 2013; Gendron et al., 2013; Mori et al., 2013a, 2013b; Zu et al., 2013). A key driver of toxicity in c9FTD/ALS is believed to be the mislocalization and aggregation of phosphorylated TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (pTDP-43), yet the connection between the G4C2 repeat expansion and this proteinopathy is not fully understood (Arai et al., 2006; Neumann et al., 2006; Todd and Petrucelli, 2016). Importantly, both the pathology and neurodegeneration characteristic of c9FTD/ALS can be recapitulated in mice by expressing an expanded G4C2 repeat throughout the CNS via AAV-mediated somatic brain transgenesis (Chew et al., 2015, 2019).

There are five DPRs produced from the bidirectional RAN translation of the G4C2 repeat: the sense DPRs poly(GA) and poly(GR); the antisense poly(PA) and poly(PR); and poly(GP), which is produced from both the sense and antisense transcripts (Ash et al., 2013; Gendron et al., 2013; Mori et al., 2013b; Zu et al., 2013). Studies have suggested that the DPRs poly(GP) and poly(PA) are largely non-toxic (Freibaum et al., 2015; Mizielinska et al., 2014; Wen et al., 2014), but the other three are all believed to contribute to pathogenesis (Todd and Petrucelli, 2016). To dissect out the role of each DPR in c9FTD/ALS, our lab used codon-optimized constructs to express the individual proteins in mice without concomitant expression of the repeat RNA. All three of these mouse models show cortical neuronal loss, as well as a loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells and, for poly(GA) and poly(PR), hippocampal degeneration (Zhang et al., 2016, 2018b, 2019). Toxicity arises through different mechanisms in each model, but together they confirm that each of these DPRs can contribute to disease. Yet, we saw little to no pTDP-43 inclusions in these DPR-specific mice (Zhang et al., 2016, 2018b, 2019). We therefore hypothesize that the development of pTDP-43 proteinopathy, and perhaps the exact pattern of selective degeneration observed in c9FTD/ALS, may be dependent not only on toxic DPRs, but also upon the presence of the repeat-containing RNA. Unfortunately, because RAN translation is always coupled to the presence of the repeat expansion, we have been unable to produce a mouse that expresses the pure G4C2 repeat RNA on its own. As an alternative approach, in this study we have taken advantage of a highly similar intronic hexanucleotide repeat expansion: the TG3C2 repeat associated with spinocerebellar ataxia 36 (SCA36).

SCA36 is a progressive cerebellar ataxia that has been primarily identified in Japan (Ikeda et al., 2012; Kobayashi et al., 2011) and Spain (García-Murias et al., 2012). Patients suffer from the loss of the cerebellar Purkinje cells and associated brainstem neurons, resulting in pronounced ataxic symptoms (García-Murias et al., 2012; Ikeda et al., 2012; Kobayashi et al., 2011). It is caused by the expansion of a TG3C2 (often denoted GGCCTG) repeat in intron 1 of NOP56 (García-Murias et al., 2012; Kobayashi et al., 2011). This repeat differs from the G4C2 repeat by only one nucleotide, and like the expanded G4C2 repeat, the TG3C2 repeat expansion also forms RNA foci that can be detected throughout the brains of SCA36 patients (Liu et al., 2014). Similar to what is observed in c9FTD/ALS, SCA36 patients also often harbor long expansions containing hundreds to thousands of repeat units (García-Murias et al., 2012; Kobayashi et al., 2011), and both repeat expansions are believed to form similar RNA secondary structures (Zhang et al., 2018a). Furthermore, RAN translation of the TG3C2 repeat can produce two of the same DPRs as the G4C2 repeat: poly(GP) and poly(PR). In other words, these two repeat expansions are remarkably similar (Figure S1A), and yet they apparently lead to the degeneration of distinct subsets of neurons, resulting in two distinct neurodegenerative disorders.

If pTDP-43 pathology and other FTD/ALS-like phenotypes are due to specific features of the G4C2 repeat RNA, we would not expect these phenotypes to arise from the expression of the TG3C2 repeat. We have shown here that this is indeed the case: mice that express the expanded TG3C2 repeat do not show a loss of cortical neurons or the development of pTDP-43 inclusions. Instead, these mice show a robust loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells, as well as pronounced locomotor defects, phenotypes highly reminiscent of SCA36. In fact, the pathological features observed in the expanded TG3C2 repeat-expressing mice, including RNA foci, RAN translation, and a lack of pTDP-43 pathology, are all consistent with what is observed in SCA36 patient tissue. Together our mouse models demonstrate that the distinct patterns of neuronal loss characteristic of c9FTD/ALS and SCA36 are both due at least in part to pathomechanisms that are intrinsic to the specific hexanucleotide repeat-containing RNA.

RESULTS

The TG3C2 Repeat Undergoes RAN Translation and Forms RNA Foci In Vitro

To generate repeat constructs for AAV injection, we extracted genomic DNA from SCA36 fibroblasts and used a nested PCR strategy to generate a 62-repeat TG3C2 fragment and a 6-repeat control. Both clones contain flanking sequences from human NOP56 and have three protein tags in-frame with each of the sense DPR encoding sequences (Figure S1B). These constructs are analogous to our existing G4C2 clones (Figure S1C).

We first tested our TG3C2 repeat constructs for RAN translation and RNA foci formation in HEK293T cells. We used a Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) immunoassay to measure poly(GP) levels (Su et al., 2014) in whole-cell lysates from HEK293T cells that were transiently transfected with either (TG3C2)6 or (TG3C2)62. As a positive control, we also transfected cells with a 50-repeat clone that contains an ATG start site in-frame with poly(GP). As expected, cells expressing this ATG-(TG3C2)50 control showed robust poly(GP) expression (Figure S1D). Poly(GP) was not detected in cells transfected with (TG3C2)6, but was observed in lysates from cells transfected with (TG3C2)62 (Figure S1D). Because this construct does not contain an ATG start site and harbors three STOP codons upstream of the repeat, this poly(GP) must have been generated by RAN translation.

By sequence analysis, the sense TG3C2 repeat also encodes poly(GL) and poly(WA). We used the protein tags included in our vector to determine whether these DPRs can be produced in HEK293T cells, using western blot analysis and immunofluorescence (IF). When we used the Myc tag to detect poly(GL), only cells expressing the (TG3C2)62 repeat showed a unique band around 18 kDa (Figure S1E). We also detected protein accumulated in the stacking gel of these blots, indicating that this protein may be aggregated. When we used the FLAG tag to detect poly(WA), we detected a robust high molecular weight smear only in lysates from cells expressing (TG3C2)62 (Figure S1F). As is consistent with our western blot data, IF with both anti-Myc and anti-FLAG antibodies revealed a punctate staining pattern in the cytoplasm of cells expressing (TG3C2)62 (Figures S1G–S1J). When we used an anti-hemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibody to detect the sense strand-derived poly(GP), we observed only diffuse staining in the (TG3C2)62-transfected cells (Figures S1K and S1L), suggesting that the protein remained soluble. A similar diffuse distribution was observed in cells transfected with ATG-(TG3C2)50, but at higher overall levels (data not shown). Together, our findings suggest that RAN translation can occur in all three sense reading frames, and that poly(GL) and poly(WA) may be aggregation prone.

To determine whether (TG3C2)62 can form RNA foci, we used RNA florescent in situ hybridization (FISH) to detect the sense strand of the repeat. We observed nuclear RNA foci specifically in cells that were transfected with (TG3C2)62 (Figures S1M and S1N).

Mice Expressing Similar Hexanucleotide Repeat

Expansions Show Distinct Behavioral Defects

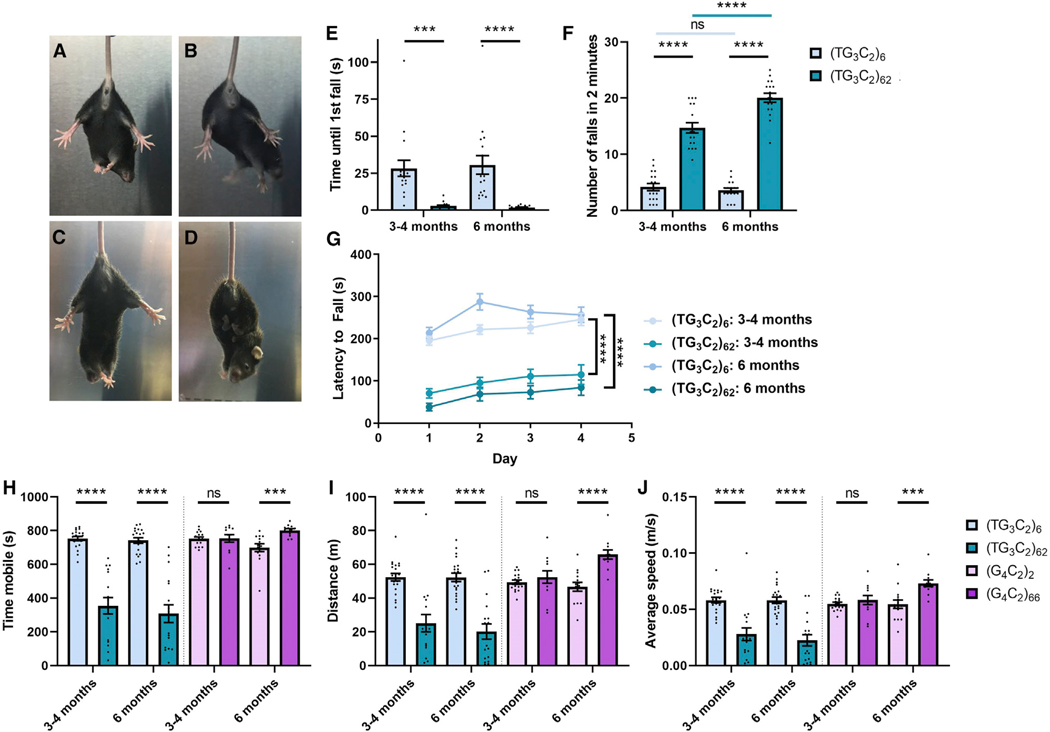

We have reported that the expression of the G4C2 repeat is sufficient to induce repeat length-dependent FTD/ALS-like phenotypes in mice (Chew et al., 2015, 2019). This c9FTD/ALS model was generated by injecting AAV9 vectors into the cerebral ventricles at post-natal day zero, which allows for widespread, primarily neuronal expression (Chakrabarty et al., 2013). We used this same protocol to express the TG3C2 repeat in mice. We were able to detect the transgene throughout the brains of these mice and did not see a significant difference in the level of expression across regions (Figure S2A). Although (TG3C2)62 mice displayed normal foot splaying behavior at 1 month (Figures 1A and 1B), they show a clasping phenotype starting at 2–3 months of age. This clasping persisted through all subsequent time points analyzed (Figures 1C and 1D). (TG3C2)62 mice showed a pronounced locomotor defect compared with controls, as evidenced by impaired performance in the rotating rod test (Figure 1G) and the hanging wire test (Figures 1E and 1F). When subjected to an open field assay, (TG3C2)62 mice preferred to stay in one location. They therefore spent less time mobile (Figure 1H), covered a lower total distance (Figure 1I), and moved at a lower average speed than control mice (Figure 1J). This phenotype is in direct contrast with what is observed in our c9FTD/ALS model; these animals become hyperactive with age, moving faster and more often in this assay (Figures 1H–1J). The c9FTD/ALS mice also show increased anxiety with age (Chew et al., 2015). No anxiety defect was observed in the (TG3C2)62 mice, neither by open field assay nor elevated plus maze, and they behaved normally in a social interaction assay (data not shown). (TG3C2)62 mice show behavioral deficits as early as 3–4 months of age, a time when the behavior of the c9FTD/ALS mice is largely normal. Some phenotypes appeared to be more severe at the later 6-month time point (Figure 1F), suggesting these phenotypes are progressive.

Figure 1. Mice Expressing Similar Repeat Expansions Show Distinct Behavioral Defects.

(A–D) Clasping phenotypes for (TG3C2)6 (A and C) and (TG3C2)62 (B and D) mice at 1 month (A and B) and 5 months (C and D).

(E and F) Hanging wire assay. (TG3C2)62 mice fall sooner (E) and more often (F) than their littermate controls.

(G) Rotating rod assay. The average latency to fall over 4 days is shown.

(H–J) The total time mobile (H), total distance covered (I), and average speed (J) in an open field assay.</p/>Error bars are SEM. 3- to 4-month-old mice: n = 20 (TG3C2)6; 17 (TG3C2)62; 17 (G4C2)2; 12 (G4C2)66. 6-month-old mice: n = 20 (TG3C2)6; 17 (TG3C2)62; 14 (G4C2)2; 12 (G4C2)66. ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001; ns, non-significant (two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). All graphs use the same color scheme.

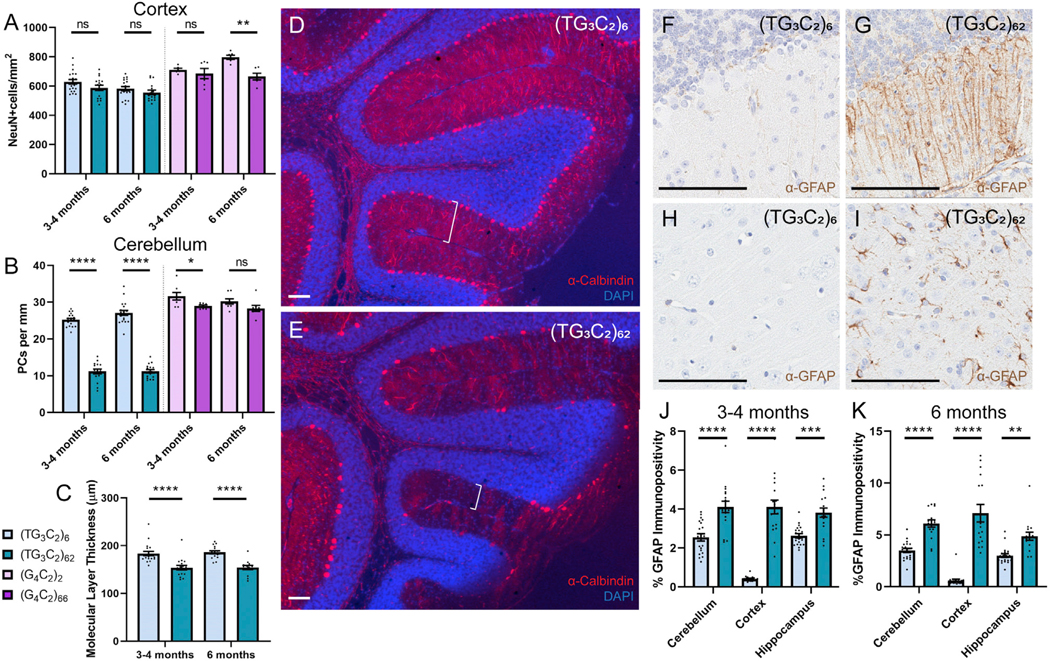

Expression of (G4C2)66 Induces Cortical Neuronal Loss, whereas Expression of (TG3C2)62 Affects the Cerebellum

(G4C2)66 mice show a loss of cortical neurons as measured by the number of neuronal nuclei (NeuN)-positive nuclei per area (Figure 2A). We did not observe any difference in the number of cortical neurons in the (TG3C2)62 mice compared with their controls (Figure 2A). Instead, we found that (TG3C2)62 mice show a dramatic loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells (Figure 2B). This loss does not appear to be lobule specific. We used the Purkinje cell marker calbindin to look at the dendritic arborization of these neurons and observed not only a reduction in the number of cell bodies, but also a narrowing of the molecular cell layer in the cerebellum of (TG3C2)62 mice (Figures 2C–2E), suggesting a degeneration of the Purkinje cell dendritic network. The other layers of the cerebellum appeared grossly normal. Consistent with this neuronal loss, (TG3C2)62 mice, like our G4C2 mice, showed a decrease in total brain weight (Figure S2B). Because (TG3C2)62 mice generally weigh less than their littermate controls (Figure S2C), we used the ratio of the brain weight to total body weight to confirm that this decrease is due to atrophy. This ratio was indeed decreased in (TG3C2)62 mice compared with controls (Figure S2D).

Figure 2. Expression of (G4C2)66 Induces Cortical Neuronal Loss, whereas Expression of (TG3C2)62 Affects the Cerebellum.

(A) The number of NeuN-positive cells per square millimeter in the cortex of the mice indicated.

(B) The number of Purkinje cells per millimeter in the cerebellum of the mice indicated.

(C) The average molecular layer thickness in micrometers for TG3C2 mice.

(D and E) Representative images of cerebellar degeneration from 3- to 4-month-old (TG3C2)62 mice (E) compared to (TG3C2)6 controls (D). Calbindin is shown in red; DAPI marks nuclei in blue. Brackets denote molecular layer thickness. Similar results were obtained at 6 months.

(F–K) IHC for GFAP in the cerebellum (F and G) and cortex (H and I) of representative 3- to 4-month-old mice. Similar results were obtained at 6 months.</p/>Quantification of GFAP positivity in TG3C2 mice at 3–4 months (J) and 6 months (K).

Error bars are SEM. Scale bars: 100 μm. 3- to 4-month-old mice: n = 20 (TG3C2)6; 17 (TG3C2)62; 17 (G4C2)2; 12 (G4C2)66. 6-month-old mice: n = 20 (TG3C2)6; 17 (TG3C2)62; 14 (G4C2)2; 12 (G4C2)66. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001. ns, non-significant (two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test).

We next looked at astrogliosis in (TG3C2)62 brains. We used glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) as a marker of reactive astrocytes, because we have previously observed increased GFAP staining in our c9FTD/ALS mice (Chew et al., 2015, 2019). Although this method for quantifying astroglial activation is not directly comparable across different brain regions, we did observe an increase in GFAP immunoreactivity in the cerebellum, cortex, and hippocampus of (TG3C2)62 mice compared with the corresponding regions in control mice (Figures 2F–2K). Because this defect was not limited to the cerebellum, we cannot rule out the possibility that other brain regions are also affected by the expression of (TG3C2)62, albeit in the absence of overt neuronal loss.

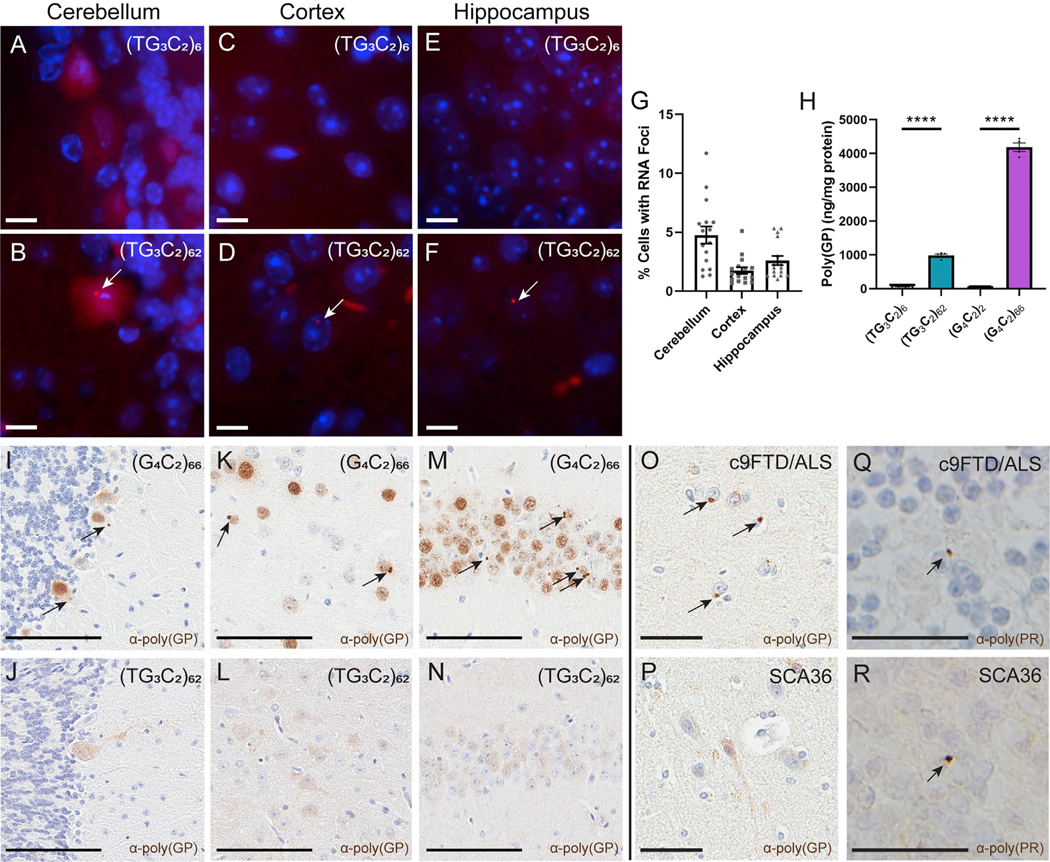

(TG3C2)62 Mice Show RNA Foci and DPR Pathology that Is Consistent with Data from SCA36 Patients

Similar to what has been seen in SCA36 patients (Liu et al., 2014), RNA FISH revealed sense RNA foci throughout the brains of (TG3C2)62 mice (Figures 3B, 3D, 3F, and 3G), but not control mice (Figures 3A, 3C, and 3E). We quantified the number of foci-containing cells in the cerebellum (Purkinje cells), hippocampus (CA1–3), and cortex in 3- to 4- and 6-month-old mice and found a comparable distribution of foci in all regions analyzed (Figure 3G). Surprisingly, we were also able to detect some antisense foci in the brains of (TG3C2)62 mice, but these foci were quite rare (Figures S3A–S3F).

Figure 3. (TG3C2)62 Forms RNA Foci and Undergoes RAN Translation In Vivo.

(A–F) FISH detects sense RNA foci (arrows) in the cerebellum (A and B), cortex (C and D), and hippocampus (E and F) of representative 3- to 4-month-old mice. DAPI marks nuclei in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm.

(G) Distribution of RNA foci in 3- to 4- month-old (TG3C2)62 mice. Similar results are seen at 6 months.

(H) MSD immunoassay to detect poly(GP) in cortical lysates from 3- to 4-month-old mice. Error bars are SEM. n = 5–8 mice per AAV. Samples were run induplicate. ****p ≤ 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test).

(I–N) IHC for poly(GP) in the cerebellum (I and J), cortex (K and L), and hippocampus (M and N) of representative 3- to 4-month-old mice. Arrows mark inclusions. Scale bars: 100 μm.

(O and P) IHC for poly(GP) in human frontal cortex of c9FTD/ALS (O) and SCA36 (P) patients. Arrows mark inclusions. Scale bars: 50 μm.

(Q and R) IHC for poly(PR) in human cerebellar granular cells of c9FTD/ALS (Q) and SCA36 (R) patients. Arrows mark inclusions. Scale bars: 25 μm.

See also Figure S4.

To determine whether the TG3C2 repeat undergoes RAN translation in vivo, we used an MSD immunoassay to detect poly(GP) in cortical protein lysates. We detected poly(GP) in (TG3C2)62 mice and (G4C2)66 mice, but not in mice expressing either unexpanded control (Figure 3H). We next used immunohistochemistry (IHC) to analyze the distribution of poly(GP) in the brain. Although we did not detect any specific staining in control mice (Figures S4A–S4F and S4J–S4L), poly(GP) was observed throughout the brains of (TG3C2)62 mice (Figures 3J, 3L, and 3N; Figures S4G–S4I and S4M–S4U). Interestingly, although poly(GP) forms inclusions in our G4C2 mice (Figures 3I, 3K, and 3M), we detected only diffuse staining in TG3C2 mice (Figures 3J, 3L, and 3N; Figures S4G–S4I and S4M–S4O). This diffuse staining appears similar in both the 3- to 4- and 6-month-old mice, as well as in a subset of mice that were aged to 12 months (Figures 3J, 3L, and 3N; Figures S4G–S4I and S4M–S4O), suggesting that age does not exacerbate this phenotype. This is in contrast with the G4C2 mice, where the number of DPR inclusions increases with age (Figure S4V) (Chew et al., 2019).

Although the diffuse localization of poly(GP) observed in our (TG3C2)62 mice is consistent with our results from HEK293T cells (Figure S1L), we wished to validate these findings in SCA36 patient samples to ensure that our model is relevant to the human disease. We performed IHC against poly(GP) on the frontal cortex of SCA36 patient brains (patient information is in Table S1). Gratifyingly, these results matched our observations in the mouse model: although we detected poly(GP) inclusions in the brain of a c9FTD/ALS patient (Figure 3O), this DPR appears to remain soluble in SCA36 patient tissue (Figure 3P). In the human genome, there is an ATG start site located upstream of the NOP56-TG3C2 repeat expansion and in-frame with poly(GP). Ergo, although this ATG start site is not present in our mouse model, it cannot be determined whether the poly(GP) observed in patient tissue is generated via RAN translation. We therefore performed IHC on the SCA36 patient tissue using our antibody against poly(PR). We were able to detect poly(PR) inclusions in the cerebellar granular layer of the SCA36 patient brains (Figure 3R), as well as in our c9FTD/ALS positive control (Figure 3Q). Because this DPR is not in-frame with a translational start site, it must be produced via RAN translation. These inclusions therefore confirm that the RAN translation observed in our mice is also present in human SCA36 and is not an artifact of our model system. This finding also verifies that, like the G4C2 repeat, the TG3C2 repeat can be bidirectionally transcribed in vivo. Unfortunately, we were unable to detect poly(GL) or poly(WA) in our SCA36 mice via the protein tags (data not shown). We also did not detect any apparent inclusions in the cerebellum or hippocampus of (TG3C2)62 mice when we performed IHC for ubiquitin (Figures S3H, S3I, S3K, and S3L), despite being able to detect inclusions in (G4C2)66 mice (Figures S3G and S3J). We used IF to look at the distribution of p62 in the SCA36 mice and again failed to see any apparent inclusions (data not shown).

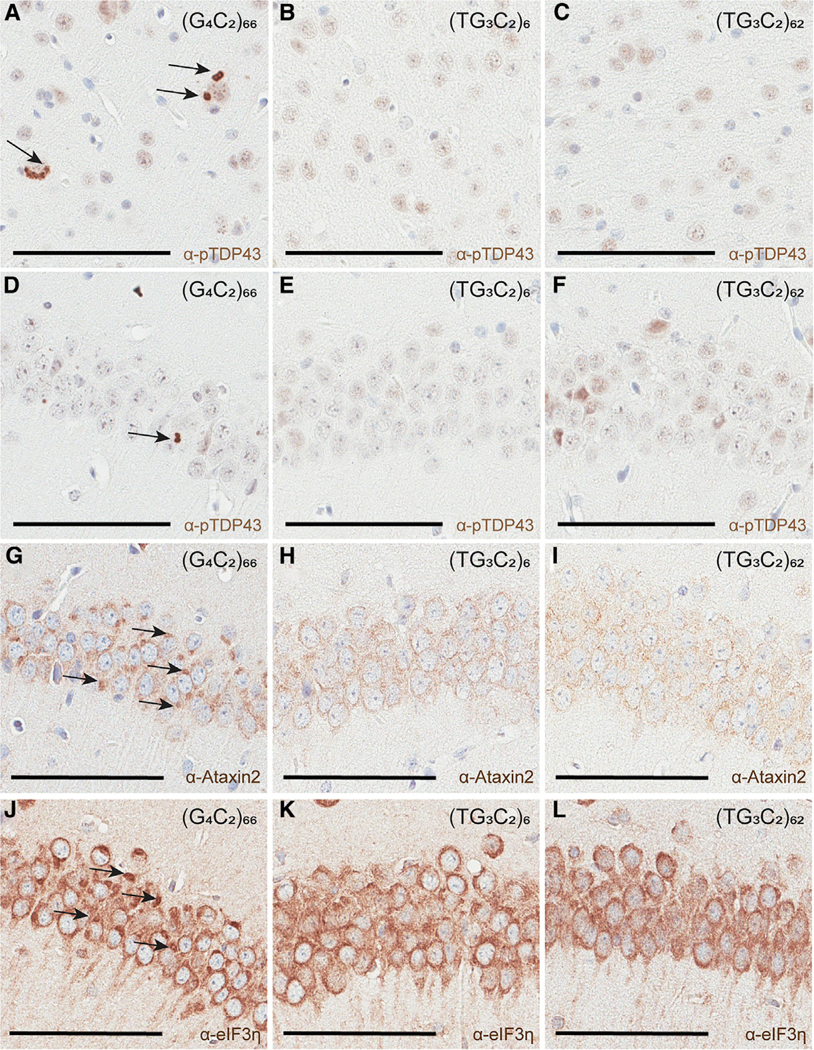

Expression of (TG3C2)62 Does Not Induce the Formation of pTDP-43 Inclusions or Aberrant Stress Granule Pathology

A major hallmark of c9FTD/ALS is the aggregation of pTDP-43, and this is recapitulated in our c9FTD/ALS model (Chew et al., 2015). Although there are only a few autopsy reports available for SCA36 patients, none of these reports have recorded evidence of pTDP-43 pathology (Liu et al., 2014; Obayashi et al., 2015). To look for pathology in our TG3C2 mice, we performed IHC using our in-house pTDP-43 antibody (Chew et al., 2015, 2019; Clippinger et al., 2013). We detected the expected inclusions in c9FTD/ALS mice (Figures 4A and 4D), but did not observe any pTDP-43 inclusions in our TG3C2 mice (Figures 4B–4F), whether 3–4, 6, or 12 months of age. We have shown the cortex and hippocampus here, but inclusions were also absent from the cerebellum and other brain regions. We also failed to detect any inclusions when using a commercially available pTDP-43 antibody (data not shown).

Figure 4. No pTDP-43 Inclusions or Aberrant Stress Granule Pathology in (TG3C2)62 Mice.

(A–F) IHC for pTDP-43 in the cortex (A–C) and hippocampus (D–F) of representative 12-month-old mice. Arrows mark inclusions.

(G–I) IHC for Ataxin2 reveals aberrant pathology (arrows) in the hippocampus of representative 12-month-old (G4C2)66 mice (G), but not in TG3C2 animals (H and I).

(J–L) IHC for eIF3h reveals aberrant pathology (arrows) in the hippocampus of representative 12-month-old (G4C2)66 mice (J), but not in TG3C2 animals (K and L).

Scale bars: 100 μm.

Recently, our lab found that persistent stress granules can be detected in the brains of our c9FTD/ALS model using multiple markers (Ataxin2, eIF3η, G3BP1), and this aberrant pathology occurs before the formation of pTDP-43 inclusions (Chew et al., 2019). We currently hypothesize that an alteration in the normal stress granule response is a key mechanism underlying the eventual aggregation of pTDP-43. If this is true, we would predict that this stress granule pathology would be absent from TG3C2 mice. Using Ataxin2 as a marker, we performed IHC on TG3C2 brains at 3–4, 6, and 12 months of age, and indeed, we did not observe any persistent stress granules (Figures 4G and 4I). We also performed IHC against eIF3η as an additional stress granule marker, and once again did not observe any aberrant pathology in 12-month-old mice (Figures 4J–4L). The hippocampus is shown here; stress granule pathology was also absent from the cortex and cerebellum.

DISCUSSION

c9FTD/ALS and SCA36 are both late-onset, progressive neurodegenerative diseases caused by the expansion of intronic hexanucleotide repeats, but the neurons that degenerate in each are distinct. We have shown that these differences in neuronal vulnerability can be recapitulated in mice simply by expressing each repeat expansion in the CNS. That is, the mechanism underlying degeneration in each disease is intrinsic to the specific repeat sequence. Furthermore, only the G4C2 repeat induces the formation of pTDP-43 pathology, suggesting that this too is intrinsic to this repeat. The downstream effects of these different repeat expansions could be triggered by specific RAN-translated DPRs, by the presence of the repeat RNA and its accumulation into foci, or by some combination thereof.

The discovery of RAN translation opened the door for protein-mediated toxicity in diseases associated with repeat expansions in noncoding regions (Zu et al., 2011). This has been well studied in c9FTD/ALS (Todd and Petrucelli, 2016). The presence of DPRs in SCA36 brain tissue verifies that RAN translation also occurs in this disorder, adding SCA36 to the growing list of diseases potentially caused by both RNA- and protein-mediated toxicity. The repeat expansion associated with SCA36 can encode two of the same DPRs that are produced in c9FTD/ALS: poly(GP) and poly(PR). Although we detected poly(GP) in our SCA36 mice, intriguingly it does not form inclusions and instead remains diffuse. These results are in complete congruence with observations from human tissue, suggesting that identical DPRs may behave differently in different disease contexts. The exact mechanism underlying this divergent pathology is not known, but one could predict that it results from the interplay of poly(GP) with other disease-specific entities such as the other DPRs. Nevertheless, although the diffuse staining is interesting, poly(GP) is largely considered to be non-toxic (Freibaum et al., 2015; Mizielinska et al., 2014; Wen et al., 2014) and is therefore unlikely to be a main pathogenic driver in SCA36 or c9FTD/ALS. The fact that this DPR is detected in both diseases supports this hypothesis. Poly(GP) is a useful biomarker for c9FTD/ALS (Gendron et al., 2017; Lehmer et al., 2017; Su et al., 2014), however, and future studies focusing on whether it can play a similar role for SCA36 are warranted.

We were also able to detect poly(PR) inclusions in the cerebellar granular cells of both c9FTD/ALS and SCA36 patients (Figures 3Q–3R). Poly(PR) is toxic (Freibaum et al., 2015; Mizielinska et al., 2014; Wen et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2019) and could therefore play a role in both diseases. At the same time, we have been unable to detect poly(PR) in our SCA36 model, neither by IHC nor MSD immunoassay (data not shown). Our models primarily overexpress the sense strand, and we were able to detect only very rare antisense foci in (TG3C2)62 mice. It is therefore likely that we do not see an accumulation of poly(PR) in this model simply because the antisense repeat is expressed at very low levels. On the other hand, the cerebellar degeneration observed in our SCA36 mice is already quite robust, suggesting that poly(PR) may not be necessary for the Purkinje cell loss characteristic of this disease. Although c9FTD/ALS and SCA36 primarily affect different subsets of neurons, some SCA36 patients also suffer from motor neuron degeneration (Kobayashi et al., 2011; García-Murias et al., 2012). It is intriguing to imagine that perhaps this shared degeneration can be attributed to poly(PR), and it will be interesting to see whether poly(PR) can be detected in the spinal cord of SCA36 patients.

In addition to the DPRs shared by c9FTD/ALS and SCA36, each disease also encodes a set of divergent DPRs. For c9FTD/ALS, several studies have argued for a role for poly(GR) and poly(GA) in pathogenesis (Freibaum et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017; Schludi et al., 2017; Wen et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014, 2016, 2018b), and the lack of these DPRs in SCA36 only supports these arguments. For SCA36, the TG3C2 repeat also encodes poly(GL) and poly(WA) in the sense direction and poly(QA) in the antisense direction. Although we can detect poly(GL) and poly(WA) in cultured cells (Figure S1), we are currently unable to detect these DPRs in our mouse model. We therefore cannot determine whether they are important for the phenotypes we observe. It is possible that these proteins are produced in our mice, but that we are unable to detect them due to technical issues associated with the protein tags. At the same time, the fact that we also failed to see inclusion-like structures when we used antibodies against ubiquitin (Figures S3H, S3I, S3K, and S3L) and p62 could suggest that these proteins are not produced in vivo, or that they do not aggregate in the brain. We hope to develop antibodies specific to these unique DPRs in the future, because this would enable us to definitively determine whether these proteins are produced in our mice and, more importantly, whether they can be detected in human tissue. Unfortunately, until such tools are available, it remains unclear whether these DPRs are relevant to SCA36.

Although we have detected RAN translation in our SCA36 model, we have been able to confirm only the presence of poly(GP), a DPR that could ultimately be benign. Therefore, we currently predict that the robust degeneration observed in this model is primarily due to the presence of RNA foci. Furthermore, because the RNA foci and RAN translation we observe in the cerebellum of our mice are in the Purkinje cells, we suspect that this degeneration is at least in part cell autonomous. It is generally believed that RNA foci exert toxicity by sequestering RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), preventing their normal function and resulting in defects in RNA processing (Todd and Petrucelli, 2018). Ultimately, which RBPs are sequestered by a repeat expansion is dictated by the structure formed when the RNA folds; that is, the structure forms high-affinity binding sites for particular proteins, producing a scaffold upon which nuclear foci are built. Although the repeat expansions in c9FTD/ALS and SCA36 differ by only a single nucleotide, and although both are able to accumulate into foci, the structures they form could be very different, and the RBPs that nucleate foci formation in each disease would therefore be distinct. In other words, it is likely that these repeats sequester separate suites of RBPs, and that certain neuronal populations are more sensitive to the disruption of one set of RBPs than to another. Future work focusing on identifying RBPs that are co-localized with foci in one disease, or in one of our mouse models, and not in the other would be invaluable in understanding the contributions of RBP sequestration to these disorders.

In summary, we have shown that, although the expression of an expanded G4C2 repeat in mice can recapitulate the behavioral and pathological features of c9FTD/ALS (Chew et al., 2015, 2019), changing just one nucleotide in this repeat sequence to TG3C2 is sufficient to induce phenotypes that are reminiscent of SCA36. By comparing and contrasting these models, we can conclude that the hallmarks of c9FTD/ALS, including selective patterns of degeneration and the formation of pTDP-43 pathology, likely derive from the presence of the repeat-containing RNA and the concomitant production of repeat-specific DPRs, while the SCA36-like phenotypes observed in our TG3C2 mice are likely due to the repeat-containing RNA. Collectively, these observations suggest that each repeat expansion will require its own therapeutic solution; that is, there will be no single treatment for these similar microsatellite disorders. Each will require the development of its own inhibitor, designed around the RNA’s unique structure, the RBPs it sequesters, and/or the downstream cellular processes it disrupts.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Leonard Petrucelli (petrucelli.leonard@mayo.edu).

Materials Availability

All unique reagents generated in this study are available upon reasonable request from the Lead Contact.

Data and Code Availability

This study did not generate any unique datasets or code.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice

All procedures involving rodents were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Experimental Animals and approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Mice were maintained in the animal facilities at Mayo Clinic Jacksonville on a 12-hour light/dark cycle in standard housing. When in their home cage, animals had access to standard mouse chow and water ad libitum. All mice were of the same genetic background (C57BL/6J) and were assigned to experimental groups based on the AAV received. When possible, litters were divided so that some pups received AAV harboring the control repeat and some received an expanded repeat, effectively controlling for any litter-specific effects on phenotype. Roughly equal numbers of males and females were included in each experimental cohort and no differences between sexes were observed, except for expected differences in total body weight. Mice were aged to three different time points as indicated in the text and figures. Total n numbers for each cohort are listed in the Quantification and Statistical Analysis section.

Post-Mortem Human Samples

We analyzed post-mortem brain samples from three SCA36 patients and one c9FTD/ALS control patient. Age, sex, and genetic diagnosis for each case are listed in Table S1. All postmortem human materials were obtained through established brain banks as noted in the acknowledgments and Key Resources Table, and were used in accordance with all ethical regulations set forth by these institutions.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE Antibodies | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-c-Myc Clone 9E10 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#M4439; RRID: AB_439694 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG clone M2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#F3165; RRID:AB_259529 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH | Meridian | Cat#H86504M; RRID: AB_151542 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-HA clone 12CA5 | Roche | Cat# 11583816001; RRID: AB_514505 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-calbindin-D-28K clone CB-955 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C9848; RRID: AB_476894 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-poly(GP) | in-house | Rb5823 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-poly(PR) | in-house | Rb8736 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-poly(GA) | in-house | Rb9880 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-poly(GR) | in-house | Rb7810 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-GFAP | Biogenex | Cat#PU020-UP |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-NeuN clone 360 | Millipore | Cat#MAB377; RRID: AB_2298772 |

| Mouse monoclonal Anti-ubiquitin clone Ubi-1 (042691GS) | Chemicon/Millipore | Cat#MAB1510; RRID: AB_2180556 |

| Rabbit polyclonal Anti-SQSTM1/p62 | Cell Signaling | Cat#5114S; RRID:AB_10624872 |

| Anti-pTDP-43 pS409/410 | in-house | Rb3655 |

| Rabbit polyclonal Anti-pTDP-43 pS409/410 | Cosmo Bio | Cat#CAC-TIP-PTD-P02; RRID: AB_1961898 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Ataxin2 | Proteintech | Cat#21776–1-AP; RRID: AB_10858483 |

| Anti-eIF3h clone A5342 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#sc-16377; RRID: AB_671941 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| pAAV-CBA-C9orf72-(G4C2)2-3Tag | Chew etal. (2015) | N/A |

| pAAV-CBA-C9orf72-(G4C2)66-3Tag | Chew etal. (2015) | N/A |

| pAAV-CBA-NOP56-(TG3C2)6-3Tag | This study. | N/A |

| pAAV-CBA-NOP56-(TG3C2)62-3Tag | This study. | N/A |

| Biological Samples | ||

| SCA36 patient-derived cortex and cerebellum | Biobank Galicia Sur Health Research Institute | https://www.iisgaliciasur.es/home/biobank-iisgs/?lang=en |

| c9FTD/ALS patient-derived cortex and cerebellum | Emory Neuropathology Core | http://neurology.emory.edu/ENNCF/neuropathology |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| HEK293T | Laboratory of Dr. Petrucelli; ATCC | Cat#CRL-3216; RRID: CVCL_0063 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mice: strain C57BL/6J | Laboratory of Dr. Petrucelli; The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# JAX:000664; RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| LNA probe: SCA36 sense: 5TYE563- CTGGGCCTGGGCCTG | Exiqon | ID#300500; batch #620467 |

| LNA probe: SCA36 antisense: 5TYE563- AGGCCCAGGCCCAG | Exiqon | ID#300500; batch# 562515 |

| SCA36 qPCR Forward Primer: GTGGTTGCGGGGCGACGC | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| SCA36 qPCR Reverse Primer: GGCTCTGTCTGCGGCCCG | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| WPRE qPCR Forward Primer: GGCTGTTGGGCACTGACAAT | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| WPRE qPCR Reverse Primer: CCGAAGGGACGTAGCAGAAG | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Zeiss AxioVision v4.9.10 | Carl Zeiss Microscopy | https://www.micro-shop.zeiss.com/en/us/system/software-axiovision+software-products/1007/ |

| Aperio eSlide Manager v12.4.2.5010 | Leica Biosystems | https://www.leicabiosystems.com/aperio-eslide-manager/ |

| Aperio ImageScope v12.4.2.7000 | Leica Biosystems | https://www.leicabiosystems.com/digital-pathology/manage/aperio-imagescope/ |

| Graphpad Prism v8.1.1 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

Cultured Cell Lines

HEK293T cells were maintained in the laboratory of Dr. Petrucelli at Mayo Clinic Jacksonville. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% Pen-Strep (penicillin-streptomycin). Cells were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2.

METHOD DETAILS

Cloning and generation of the AAV vectors

To generate the (TG3C2)6 and (TG3C2)62 expression vectors, we employed a cloning strategy that resembled the protocol we previously used to generate our G4C2 repeat vectors (Su et al., 2014). We began with a sequence analysis of the genomic DNA from SCA36 fibroblasts, which confirmed that the expansion consisted of repeating units of TGGGCC (abbreviated TG3C2). The genomic DNA from these patient fibroblasts and (TG3C2)6 oligomers (Integrated DNA Technologies) were then used as templates in a nested PCR strategy using ThermalAce DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) or AmpliTaq Gold 360 Polymerase (Thermo Fisher) to amplify (TG3C2)n repeat fragments. These fragments include flanking sequences from the NOP56 gene both 5′ (69 base pairs) and 3′ (40 base pairs) of the repeat. The PCR products were cloned into the pAG3 expression vector (gift of T. Golde, University of Florida), and then sequentially ligated using TypeIIS restriction enzymes to ultimately generate a (TG3C2)62 fragment. As a non-pathogenic control, a (TG3C2)6 repeat was amplified from genomic DNA from a lymphoblastoid cell line of a SCA36-negative patient. Both the 62- and 6-repeat fragments, including the NOP56 flanking sequences, were subcloned into an AAV expression vector (pAM/CBA-pl-WPRE-BGH) containing inverted repeats of serotype 2. This vector also contains upstream stop codons in each reading frame, as well as three different C-terminal protein tags in alternate reading frames (Figures S1B and S1C). The (G4C2)6 and (G4C2)66 AAV vectors were generated as previously described (Chew et al., 2015). The repeats, along with 5′ (119 base pairs) and 3′ (100 base pairs) flanking sequences from the human C9orf72 gene, were also cloned into the pAM/CBA-pl-WPRE-BGH vector.

To generate AAV for injection, the AAV-C9orf72-(G4C2)2, AAV-C9orf72-(G4C2)66, AAV-NOP56-(TG3C2)6, and AAV-NOP56(TG3C2)62 particles were packaged into AAV serotype 9 capsids and purified using standard methods (Zolotukhin et al., 1999). Briefly, the AAV expression vectors were co-transfected with helper plasmids into HEK293T cells. Cells were harvested 48 hours later and lysed with 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and 50 units/mL Bensonase (Sigma-Aldrich) by freeze-thaw. The virus was then purified from these lysates using a discontinuous iodixanol gradient and the genomic titer of each virus was determined by qPCR. Viruses were then diluted to a standard titer of 1E13 using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), aliquoted, and frozen prior to injection.

RNA florescent in situ hybridization

HEK293T cells were allowed to grow on glass coverslips and then transiently transfected with indicated AAV expression vectors using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were also transfected with an empty vector as a negative control. Cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde 48 hours post-transfection, permeabilized using 0.2% Triton X-100 in 1x diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated PBS, and incubated in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 2x saline-sodium citrate buffer (SSC), 50mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.0) for 30 minutes in a humidified chamber at 55C. The 5TYE563-CTGGGCCTGGGCCTG sense LNA probe (Exiqon 300500; batch 620467) was diluted in hybridization buffer to a concentration of 60nM. Cells were bathed in the diluted probe for 24 hours in a humidified chamber at 55°C before being washed with 0.1% Tween in 2x SSC for 5 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then washed two times for 10 minutes in 0.2x SSC at 55°C and mounted to glass slides using Vectashield mounting media with DAPI (Vector Laboratories).

For mouse tissue sections, mice were euthanized at the desired time point by carbon dioxide overdose and both brains and spinal cords were harvested. Hemibrains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours, then rinsed with PBS and embedded in paraffin. Brains were sectioned (5 μM, sagittal), mounted on positively charged glass slides, and dried overnight. These paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) brain sections were then deparaffinized in xylenes and rehydrated through a series of ethanol dilutions. Sections were permeabilized with ice cold 2% acetone/1x DEPC-treated PBS for five minutes, then dehydrated through a series of ethanol solutions. The pre-hybridization, probe hybridization, and wash steps were carried out as described for fixed HEK293T cells. Slides were dipped in 0.3% Sudan black for 1 minute (diluted in 70% methanol), then rinsed with DEPC-treated water. Coverslips were mounted with Vectashield with DAPI. The same protocol was used when employing the 5TYE563-AGGCCCAGGCCCAG antisense LNA probe (Exiqon 300500; batch 562515).

RNA foci were imaged on a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) under 63x magnification. Quantification of RNA foci-positive cells were completed by eye. All Purkinje cells present in the hemisection were scored for foci (150–300 cells, depending on degeneration levels). Approximately 300 cells were scored from the CA1-CA3 region of the hippocampus, and 500–600 cells were scored from randomly selected imaging planes that spanned the entire length of the cortical section.

MSD immunoassays

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with AAV expression vectors harboring the (TG3C2)6 or (TG3C2)62 repeats, or with an empty vector control, using Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were then harvested 72 hours later and lysed using 1% Triton X-100, 2% SDS, and a mix of phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were sonicated and cleared by centrifugation. To generate mouse cortical lysates, fresh-frozen tissue was sonicated in ice-cold TE (50mM Tris pH 7.4, 50mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA) with 2x protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails until all tissue chunks were dissolved. An equal volume of homogenate was mixed with a 2X protein lysis buffer (50mM Tris pH 7.4, 250mM NaCl, 2% Triton X-100, 4% SDS, protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails) and resonicated. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation and the soluble fraction was collected. A BCA assay was used to determine the total protein concentration of each lysate and an equal amount of protein was used for a poly(GP) sandwich immunoassay as previously described. Briefly, lysates were diluted in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and tested alongside serial dilutions of recombinant (GP)8 in TBS. Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) electrochemiluminescence detection technology was used to measure poly(GP) levels in each sample. Response values according to the intensity of emitted light upon electrochemical stimulation of the assay plate were acquired with the MSD QUICKPLEX SQ120 and background corrected. A standard curve was generated using the serial (GP)8 dilutions and the level of poly(GP) per experimental sample was interpolated using this curve. A similar protocol was used to measure poly(PR) levels.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole cell lysates were generated from transiently transfected HEK293T cells as described above. A BCA assay was used to determine the protein concentration of the lysates and equal amounts of protein were mixed with loading buffer and ran on a 4%–20% SDS-PAGE gradient gel. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and subjected to western blot analysis using anti-c-Myc clone 9E10 (1:1000, Sigma) or anti-FLAG M2 (1:1000, Sigma). Anti-GAPDH (1:4000, Fisher/Meridian) was used as a loading control.

Immunofluorescence

HEK293T cells were allowed to grow on glass coverslips and then transiently transfected with indicated AAV expression vectors using Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were also transfected with an empty vector as a negative control. Cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde 48 hours post-transfection, permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100, washed in 1x PBS, and blocked in 1% normal goat serum, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1x PBS. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C, then washed in 0.05% Triton X-100. Cells were incubated with Alexa 488-tagged secondary antibodies (1:500, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) diluted in blocking solution for 1.5 hours at room temperature in the dark. Cells were then washed, stained with Hoescht (1:10000), washed in 1x PBS and mounted to glass slides using Vectashield. Primary antibodies used were anti-c-Myc clone 9E10 (1:1000, Sigma), anti-FLAG M2 (1:1000, Sigma), and anti-HA (1:1000, Roche).

For immunofluorescence against calbindin in the mouse cerebellum, FFPE brain sections were generated as described above. Slides were deparafinized in xylenes and rehydrated through a series of ethanol solutions. Slides were then steamed for 30 minutes in sodium citrate buffer (10mM citrate, 0.05% Tween-20 pH 6.0) and blocked in Dako Protein Block plus Serum Free before being incubated with anti-calbindin-D 28K (1:300; Sigma C9848) diluted with Dako Antibody Diluent overnight at 4°C. Sections were then washed in PBS before being incubated with an Alexa 568-tagged secondary antibody (1:500, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc) in Dako Antibody diluent for 1.5 hours at room temperature in the dark. Slides were washed in PBS, dipped in 0.3% Sudan black for 2 minutes, and rinsed in distilled water. Coverslips were mounted with Vectashield with DAPI. Images were then analyzed on an Axio Imager Z1 fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) and the number of Purkinje cells was counted manually. The molecular layer thickness was measured using Zeiss AxioVision software.

Neonatal viral injections

Intracerebroventricular injections of AAV were carried out as previously described (Chew et al., 2015, 2019). Briefly, post-natal day zero C57BL/6J pups were cryoanesthetized on ice. Two microliters (1E13 viral genomes/μl) of the desired AAV solution was then manually injected into each lateral ventricle using a 32-gauge needle (product#7803–04, 0.5 in. custom length, point style 4, 12 degrees, Hamilton Company) fitted to a 10 μL syringe (Hamilton Company). Following injection, pups were allowed to recover on a heated pad before being returned to their home cage.

qRT-PCR to detect transgene expression

Fresh-frozen brain tissue was homogenized by sonication in ice-cold TE as described above and homogenate was immediately mixed with Trizol LS at a ratio of 1:3. Total RNA was extracted using a Direct-zol RNA prep kit from Zymo Research, Inc. according to the manufacturer’s instructions and including in-column DNase I digestion. This RNA was used as template to generate cDNA using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit from Applied Biosystems. The resulting cDNA was diluted with water and subjected to a SYBR Green-based qRT-PCR assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using primers designed to detect either the NOP56 flanking sequences or the WPRE domain present in the AAV transgenes. Both probes revealed similar results. Primers designed to detect mouse GAPDH were used as an endogenous control. These assays were carried out in triplicate using an ABI Prism 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System from Applied Biosystems.

Behavioral tests

Cohorts of TG3C2 and G4C2 repeat-expressing mice were subjected to a battery of behavioral assays over the course of two weeks at either 3–4 months or 6 months of age. All mice were allowed to acclimate to the testing room for at least one hour before beginning any behavioral assessments, and all mice were returned to their home cages after all testing was complete for the day. All behavioral equipment was sterilized with 30% ethanol prior to use and in between each animal trial.

Clasping assessment

To assess hindlimb clasping, mice were lifted by the tail and observed for at least 10 s before being returned to their home cage. Mice were scored on a scale of 0–3 for the severity of their clasping phenotype, but all (TG3C2)62 repeat-expressing mice began to clasp by 2–3 months of age (score of 1–3) and had already developed a severe clasping behavior by 3–4 months of age (score of 3).

Hanging Wire Test

A 2 mm-thick wire was suspended between two vertical stands approximately 55 cm apart, at a height of 35 cm. A layer of cushioned bedding was placed beneath the wire to prevent injury to the animals. Mice were weighed prior to beginning the assay to account for differences in body weight. Mice were lifted by the tail and allowed to grasp the wire with their front paws. Once they grasped the wire, the animal was gently released and allowed to hang from the wire for as long as they could. The number of seconds until the first fall was recorded, and then the timer was stopped and the mouse was allowed to re-grasp the wire. The timer was restarted and the assay continued. The total number of falls in 2 minutes was recorded.

Rotarod Assay

An automated rotarod system (Med Associates, Inc.) was used for this assay. Each mouse was placed on a rotating spindle that was set to accelerate from 4–40 rpm over the course of 5 minutes. The apparatus is divided into 5 different lanes, and two identical machines were used simultaneously, allowing for a total of 10 mice to be assessed at a time. Each lane is equipped with a timer and a sensor that is triggered when a mouse falls from the rotating spindle. This sensor stops the timer and the latency to fall is recorded. On each day, each mouse was assessed for four consecutive trials, with at least 20 minutes of rest time between trials. This procedure was then repeated for the following 3 days. If a mouse clung to the spindle and rolled for more than three consecutive rotations, the timer was stopped and the mouse was removed from the apparatus. The recorded time was used as the latency to fall for that trial.

Open Field Assay

Mice were placed in the center of an open field area inside a square Perspex box (40 × 40 × 30 cm). Each mouse was allowed to explore the field for a total of 15 minutes while movement was monitored through the use of an overhead camera and AnyMaze software (Stoelting Co.). Several parameters were recorded, including the total time each mouse spent mobile, the total distance covered, and the average speed at which each mouse moved. Side-mounted photobeams raised 7.6 cm above the floor were used to measure rearing. An overhanging light fixture was suspended above the center of the field and the ratio of time spent in this illuminated center and the outer wall was used to assess anxiety levels in the mice.

Immunohistochemistry

FFPE tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylenes and rehydrated through a series of ethanol solutions. Antigen retrieval was performed in distilled water or pH 9 Tris-EDTA (DAKO) for 30 min. Sections were then immunostained with antibodies against poly(GP) (1:10000, generated in-house), poly(PR) (1:500, generated in-house), poly(GA) (1:50000, generated in-house), poly(GR) (1:2500, generated in-house), GFAP (1:2500, Biogenex), NeuN (1:5000, Millipore), or ubiquitin (1:55000) using the DAKO Autostainer (Universal Staining System) and the DAKO+HRP system. IHC against pTDP-43 was carried out using the VECTASTAIN Elite-ABC kit (Vector Laboratories). For these slides, antigen retrieval was done by steaming the slides in sodium citrate buffer for 30 minutes before blocking in the DAKO Dual Endogenous Enzyme Block. Sections were blocked with 2% normal goat serum in PBS for one hour at room temperature and then incubated with anti-TDP-43 pS409/410 (1:500; generated in-house) overnight at 4°C. Slides were then washed in PBS and incubated in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200) for 2 hours at room temperature. Slides were washed again, incubated with avidin-biotin complex solution for 30 minutes, and washed again. 3,3′-diaminobesidine (Acros Organics) was activated with hydrogen peroxide and a positive control slide from the brain of a G4C2 repeat-expressing mouse was used to determine the staining time. Once the desired staining level was achieved, the reaction was stopped by rinsing in distilled water. A similar protocol was used to stain for stress granule markers using antibodies against Ataxin2 (1:500; Proteintech 21776–1-AP) and eIF3h (1:2000; Abclonal A5342 Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-16377).

All IHC-treated slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated with a series of ethanol washes and xylenes, and cover-slipped using Cytoseal mounting media (Themo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

IHC-treated slides were scanned with a ScanScope® AT2 (Leica Biosystems) at either 20x or 40x magnification and images were analyzed using ImageScope® and Aperio ePathology software (Leica Biosystems). For NeuN analysis, the cortex was selected as a region of interest and the number of NeuN-positive cells per area was quantified using an algorithm designed to detect nuclei. The number of Purkinje cells was counted manually and the length of the Purkinje cell layer measured using ImageScope on slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin as previously described (Chew et al., 2015). The degree of GFAP and diffuse poly(GP) immunoreactivity was measured using a custom-designed positive pixel count algorithm (Murray et al., 2012), the output of which is the number of positively-stained pixels per annotation area. The cortex, cerebellum, and hippocampus were isolated as individual annotation areas for the purpose of these analyses. It is worth noting that the cerebellum often has increased background staining compared to other brain regions due to the pigmentation of various cell types in this region. This is particularly noticeable when quantifying diffuse poly(GP) staining, as this positive staining occurs only in the few remaining Purkinje cells in the (TG3C2)62 mice.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Quantification methods are described in the Method Details and in figure legends. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism. The statistical test used and the definition of statistical significance in each case is included in the figure legends. All error bars represent the SEM. Generally, unless otherwise noted, graphs including multiple samples at multiple time points were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc multiple comparisons test. Whenever possible, investigators were blinded to the AAV status of each mouse, including during behavioral assessments and when quantifying neuronal number and GFAP positivity. For all behavioral analyses included in this study, n numbers are as follows. For 3- to −4-month-old mice: n = 20 (TG3C2)6; 17 (TG3C2)62; 17 (G4C2)2; and 12 (G4C2)66. For 6-month-old mice: n = 20 (TG3C2)6; 17 (TG3C2)62; 14 (G4C2)2; and 12 (G4C2)66. The overall cohort size was determined based on standard methods used in the literature and was more than adequate as determined by the Resource Equation Method (Charan and Kantharia, 2013). All of these TG3C2 mice were included in subsequent pathological analyses, unless noted in the figure legend. Six to eight G4C2 mice of each repeat length were analyzed for neuronal loss and DPR inclusions. These same mice were also used as positive controls when staining for poly(GP) and poly(PR). For analyses involving the 12 month TG3C2 mice and associated G4C2 controls, 5–7 mice per repeat length were assessed for poly(GP), pTDP-43 inclusions, stress granule markers, and antisense RNA foci. These mice also displayed all other pathological phenotypes assessed at earlier time points (sense RNA foci, Purkinje cell loss/cerebellar degeneration, increased GFAP immunoreactivity) at levels that were similar to what was seen in 6-month-old mice (data not shown). All cell culture experiments were performed in duplicate or triplicate, and each experiment was repeated at least three times to ensure consistent results.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

NOP56-(TG3C2)62 and C9orf72-(G4C2)66 repeats confer distinct phenotypes in mice

NOP56-(TG3C2)62 induces cerebellar degeneration akin to SCA36

RNA foci and RAN translation in the SCA36 mice resemble human pathologies

TDP-43 proteinopathy and aberrant stress granules are unique to C9orf72-G4C2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to all patients and their families who agreed to donate postmortem tissue. Human biological samples and associated data were obtained from the Emory Neuropathology Core (P30 NS055077) and the Brain Bank of Biobank Galicia Sur Health Research Institute (PT17/0015/0034) and were used in compliance with all ethical regulations set forth by these institutions. Informed consent was obtained from patients prior to the inclusion of samples in each bank. We would like to acknowledge all individuals who assisted in the procuring of these samples. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorder and Stroke (grants R35NS097273, P01NS084974, P01NS099114, R01NS088689, R35NS097263, R01NS91749, and R21NS084528), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grant R01ES20395), the Department of Defense (ALSRP grant AL130125), the Mayo Clinic Foundation, the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins, Target ALS, an ALS Association Milton Safenowitz Postdoctoral Fellowship (17-PDF-361 to T.W.T.), and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (grant 426618).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107616.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Arai T, Hasegawa M, Akiyama H, Ikeda K, Nonaka T, Mori H, Mann D, Tsuchiya K, Yoshida M, Hashizume Y, and Oda T. (2006). TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 351, 602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash PE, Bieniek KF, Gendron TF, Caulfield T, Lin WL, Dejesus-Hernandez M, van Blitterswijk MM, Jansen-West K, Paul JW 3rd, Rademakers R, et al. (2013). Unconventional translation of C9ORF72 GGGGCC expansion generates insoluble polypeptides specific to c9FTD/ALS. Neuron 77, 639–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty P, Rosario A, Cruz P, Siemienski Z, Ceballos-Diaz C, Crosby K, Jansen K, Borchelt DR, Kim JY, Jankowsky JL, et al. (2013). Capsid serotype and timing of injection determines AAV transduction in the neonatal mice brain. PLoS ONE 8, e67680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charan J, and Kantharia ND (2013). How to calculate sample size in animal studies? J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 4, 303–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew J, Gendron TF, Prudencio M, Sasaguri H, Zhang YJ, Castanedes-Casey M, Lee CW, Jansen-West K, Kurti A, Murray ME, et al. (2015). Neurodegeneration. C9ORF72 repeat expansions in mice cause TDP-43 pathology, neuronal loss, and behavioral deficits. Science 348, 1151–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew J, Cook C, Gendron TF, Jansen-West K, Del Rosso G, Daughrity LM, Castanedes-Casey M, Kurti A, Stankowski JN, Disney MD, et al. (2019). Aberrant deposition of stress granule-resident proteins linked to C9orf72-associated TDP-43 proteinopathy. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clippinger AK, D’Alton S, Lin WL, Gendron TF, Howard J, Borchelt DR, Cannon A, Carlomagno Y, Chakrabarty P, Cook C, et al. (2013). Robust cytoplasmic accumulation of phosphorylated TDP-43 in transgenic models of tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Knock J, Higginbottom A, Stopford MJ, Highley JR, Ince PG, Wharton SB, Pickering-Brown S, Kirby J, Hautbergue GM, and Shaw PJ (2015). Antisense RNA foci in the motor neurons of C9ORF72-ALS patients are associated with TDP-43 proteinopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 130, 63–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, Nicholson AM, Finch NA, Flynn H, Adamson J, et al. (2011). Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72, 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freibaum BD, Lu Y, Lopez-Gonzalez R, Kim NC, Almeida S, Lee KH, Badders N, Valentine M, Miller BL, Wong PC, et al. (2015). GGGGCC repeat expansion in C9orf72 compromises nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature 525, 129–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Murias M, Quintá ns B, Arias M, Seixas AI, Cacheiro P, Tarrío R, Pardo J, Millá n MJ, Arias-Rivas S, Blanco-Arias P, et al. (2012). ‘Costa da Morte’ ataxia is spinocerebellar ataxia 36: clinical and genetic characterization. Brain 135, 1423–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron TF, Bieniek KF, Zhang YJ, Jansen-West K, Ash PE, Caulfield T, Daughrity L, Dunmore JH, Castanedes-Casey M, Chew J, et al. (2013). Antisense transcripts of the expanded C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat form nuclear RNA foci and undergo repeat-associated non-ATG translation in c9FTD/ALS. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 829–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron TF, Chew J, Stankowski JN, Hayes LR, Zhang YJ, Prudencio M, Carlomagno Y, Daughrity LM, Jansen-West K, Perkerson EA, et al. (2017). Poly(GP) proteins are a useful pharmacodynamic marker for C9ORF72-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaai7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda Y, Ohta Y, Kobayashi H, Okamoto M, Takamatsu K, Ota T, Manabe Y, Okamoto K, Koizumi A, and Abe K. (2012). Clinical features of SCA36: a novel spinocerebellar ataxia with motor neuron involvement (Asidan). Neurology 79, 333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Abe K, Matsuura T, Ikeda Y, Hitomi T, Akechi Y, Habu T, Liu W, Okuda H, and Koizumi A. (2011). Expansion of intronic GGCCTG hexanucleotide repeat in NOP56 causes SCA36, a type of spinocerebellar ataxia accompanied by motor neuron involvement. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YB, Baskaran P, Gomez-Deza J, Chen HJ, Nishimura AL, Smith BN, Troakes C, Adachi Y, Stepto A, Petrucelli L, et al. (2017). C9orf72 poly GA RAN-translated protein plays a key role in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis via aggregation and toxicity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 4765–4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmer C, Oeckl P, Weishaupt JH, Volk AE, Diehl-Schmid J, Schroeter ML, Lauer M, Kornhuber J, Levin J, Fassbender K, et al. ; German Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (2017). Poly-GP in cerebrospinal fluid links C9orf72-associated dipeptide repeat expression to the asymptomatic phase of ALS/FTD. EMBO Mol. Med. 9, 859–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Ikeda Y, Hishikawa N, Yamashita T, Deguchi K, and Abe K. (2014). Characteristic RNA foci of the abnormal hexanucleotide GGCCUG repeat expansion in spinocerebellar ataxia type 36 (Asidan). Eur. J. Neurol. 21, 1377–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizielinska S, Lashley T, Norona FE, Clayton EL, Ridler CE, Fratta P, and Isaacs AM (2013). C9orf72 frontotemporal lobar degeneration is characterised by frequent neuronal sense and antisense RNA foci. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 845–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizielinska S, Grönke S, Niccoli T, Ridler CE, Clayton EL, Devoy A, Moens T, Norona FE, Woollacott IOC, Pietrzyk J, et al. (2014). C9orf72 repeat expansions cause neurodegeneration in Drosophila through arginine-rich proteins. Science 345, 1192–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Arzberger T, Grässer FA, Gijselinck I, May S, Rentzsch K, Weng SM, Schludi MH, van der Zee J, Cruts M, et al. (2013a). Bidirectional transcripts of the expanded C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat are translated into aggregating dipeptide repeat proteins. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 881–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Weng SM, Arzberger T, May S, Rentzsch K, Kremmer E, Schmid B, Kretzschmar HA, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C, et al. (2013b). The C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat is translated into aggregating dipeptide-repeat proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science 339, 1335–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray ME, Vemuri P, Preboske GM, Murphy MC, Schweitzer KJ, Parisi JE, Jack CR Jr., and Dickson DW (2012). A quantitative postmortem MRI design sensitive to white matter hyperintensity differences and their relationship with underlying pathology. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 71, 1113–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM, et al. (2006). Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314, 130–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obayashi M, Stevanin G, Synofzik M, Monin ML, Duyckaerts C, Sato N, Streichenberger N, Vighetto A, Desestret V, Tesson C, et al. (2015). Spinocerebellar ataxia type 36 exists in diverse populations and can be caused by a short hexanucleotide GGCCTG repeat expansion. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 86, 986–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, Simón-Sánchez J, Rollinson S, Gibbs JR, Schymick JC, Laaksovirta H, van Swieten JC, Myllykangas L, et al. ; ITALSGEN Consortium (2011). A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72, 257–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schludi MH, Becker L, Garrett L, Gendron TF, Zhou Q, Schreiber F, Popper B, Dimou L, Strom TM, Winkelmann J, et al. (2017). Spinal poly-GA inclusions in a C9orf72 mouse model trigger motor deficits and inflammation without neuron loss. Acta Neuropathol. 134, 241–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z, Zhang Y, Gendron TF, Bauer PO, Chew J, Yang WY, Fostvedt E, Jansen-West K, Belzil VV, Desaro P, et al. (2014). Discovery of a biomarker and lead small molecules to target r(GGGGCC)-associated defects in c9FTD/ALS. Neuron 83, 1043–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd TW, and Petrucelli L. (2016). Insights into the pathogenic mechanisms of Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72) repeat expansions. J. Neurochem. 138 (Suppl 1), 145–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd TW, and Petrucelli L. (2018). Neurodegenerative diseases and RNA-mediated toxicity In The Molecular and Cellular Basis of Neurodegenerative Diseases, Wolfe MS, ed. (Academic Press; ), pp. 441–475. [Google Scholar]

- Wen X, Tan W, Westergard T, Krishnamurthy K, Markandaiah SS, Shi Y, Lin S, Shneider NA, Monaghan J, Pandey UB, et al. (2014). Antisense proline-arginine RAN dipeptides linked to C9ORF72-ALS/FTD form toxic nuclear aggregates that initiate in vitro and In vivo neuronal death. Neuron 84, 1213–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YJ, Jansen-West K, Xu YF, Gendron TF, Bieniek KF, Lin WL, Sasaguri H, Caulfield T, Hubbard J, Daughrity L, et al. (2014). Aggregation-prone c9FTD/ALS poly(GA) RAN-translated proteins cause neurotoxicity by inducing ER stress. Acta Neuropathol. 128, 505–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YJ, Gendron TF, Grima JC, Sasaguri H, Jansen-West K, Xu YF, Katzman RB, Gass J, Murray ME, Shinohara M, et al. (2016). C9ORF72 poly(GA) aggregates sequester and impair HR23 and nucleocytoplasmic transport proteins. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 668–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Roland C, and Sagui C. (2018a). Structural and Dynamical Characterization of DNA and RNA Quadruplexes Obtained from the GGGGCC and GGGCCT Hexanucleotide Repeats Associated with C9FTD/ALS and SCA36 Diseases. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 9, 1104–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YJ, Gendron TF, Ebbert MTW, O’Raw AD, Yue M, Jansen-West K, Zhang X, Prudencio M, Chew J, Cook CN, et al. (2018b). Poly(GR) impairs protein translation and stress granule dynamics in C9orf72-associated frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Med. 24, 1136–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YJ, Guo L, Gonzales PK, Gendron TF, Wu Y, Jansen-West K, O’Raw AD, Pickles SR, Prudencio M, Carlomagno Y, et al. (2019). Heterochromatin anomalies and double-stranded RNA accumulation underlie C9orf72 poly(PR) toxicity. Science 363, eaav2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhin S, Byrne BJ, Mason E, Zolotukhin I, Potter M, Chesnut K, Summerford C, Samulski RJ, and Muzyczka N. (1999). Recombinant adeno-associated virus purification using novel methods improves infectious titer and yield. Gene Ther. 6, 973–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu T, Gibbens B, Doty NS, Gomes-Pereira M, Huguet A, Stone MD, Margolis J, Peterson M, Markowski TW, Ingram MA, et al. (2011). Non-ATG-initiated translation directed by microsatellite expansions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 260–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu T, Liu Y, Bañez-Coronel M, Reid T, Pletnikova O, Lewis J, Miller TM, Harms MB, Falchook AE, Subramony SH, et al. (2013). RAN proteins and RNA foci from antisense transcripts in C9ORF72 ALS and frontotemporal dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E4968–E4977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate any unique datasets or code.