Introduction:

Interest in clinical rotations in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) has grown among high-income country (HIC) orthopaedic residents. This study addresses the following questions: (1) What motivates HIC surgical residents to rotate in LMICs? (2) What is the impact of rotations on HIC residents? (3) What are the LMIC partner perceptions of HIC collaboration?

Materials and Methods:

A search strategy of multiple databases returned 3,740 unique articles pertaining to HIC surgical resident motivations for participating in rotations in LMICs or the LMIC host perspective. Data extraction was dually performed using meta-ethnography, the qualitative equivalent of meta-analysis.

Results:

Twenty-one studies were included in the final analysis. HIC residents were primarily motivated to rotate in LMICs by altruistic intent, with greatest impact on professional development. LMIC partners mostly valued HIC sustained investment and educational opportunities for LMIC partners. From LMIC's perspective, potential harm from collaboration arose from system-level and individual-level discordance between HIC and LMIC expectations and priorities. HIC priorities included the following: (1) adequate operative time, (2) exposure to varied pathology, and (3) mentorship. LMIC priorities included the following: (1) avoiding competition with HIC residents for surgical cases, (2) that HIC groups not undermine LMIC internal authority, (3) that HIC initiatives address local LMIC needs, and (4) that LMIC partners be included as authors on HIC research initiatives. Both HIC and LMIC partners raised ethical concerns regarding collaboration and perceived HIC residents to be underprepared for their LMIC rotation.

Discussion:

This study synthesizes the available literature on HIC surgical resident motivations for and impact of rotating in LMICs and the LMIC host perception of collaboration. Three improvement categories emerged: that residents (1) receive site-specific preparation before departure, (2) remain in country long enough to develop site-specific skills, and (3) cultivate flexibility and cultural humility. Specific suggestions based on synthesized data are offered for each concept and can serve as a foundation for mutually beneficial international electives in LMICs for HIC orthopaedic trainees.

Orthopaedic surgery resident interest in low- and middle-income country (LMIC) rotations is growing, a trend broadly reflected by high-income country (HIC) surgical residents over the past decade1,2. In a 2008 survey of resident members of the American College of Surgeons, over 80% of respondents endorsed preference for international electives over other clinical opportunities, with over 70% wishing to participate even without credit toward graduation requirements3. Although lack of funding has long been considered prohibitive to implementing such orthopaedic rotations4, new models of orthopaedic partnerships within LMICs5,6 and evidence for the cost-effectiveness of global orthopaedic care7 have increased LMIC orthopaedic access. Today, over 25% of North American orthopaedic residency programs offer some form of international training2,8-11.

The published orthopaedic literature regarding LMIC surgical rotations overwhelmingly focuses on benefits to HIC residents11-16. Perspectives of LMIC hosts are rarely considered despite concerns that resident rotations may have negative outcomes for LMIC partners13,17. Although the LMIC perspective is lacking in the orthopaedic literature, an examination of other surgical specialties may provide insight for orthopaedics.

The goal of this study was to provide a comprehensive understanding of the following questions because they pertain to international orthopaedic resident rotations. (1) What motivates HIC surgical residents to electively rotate in LMICs? (2) What is the perceived impact of such rotations on HIC residents? (3) What are LMIC partner perceptions of HIC collaboration?

Methods

Search Strategy

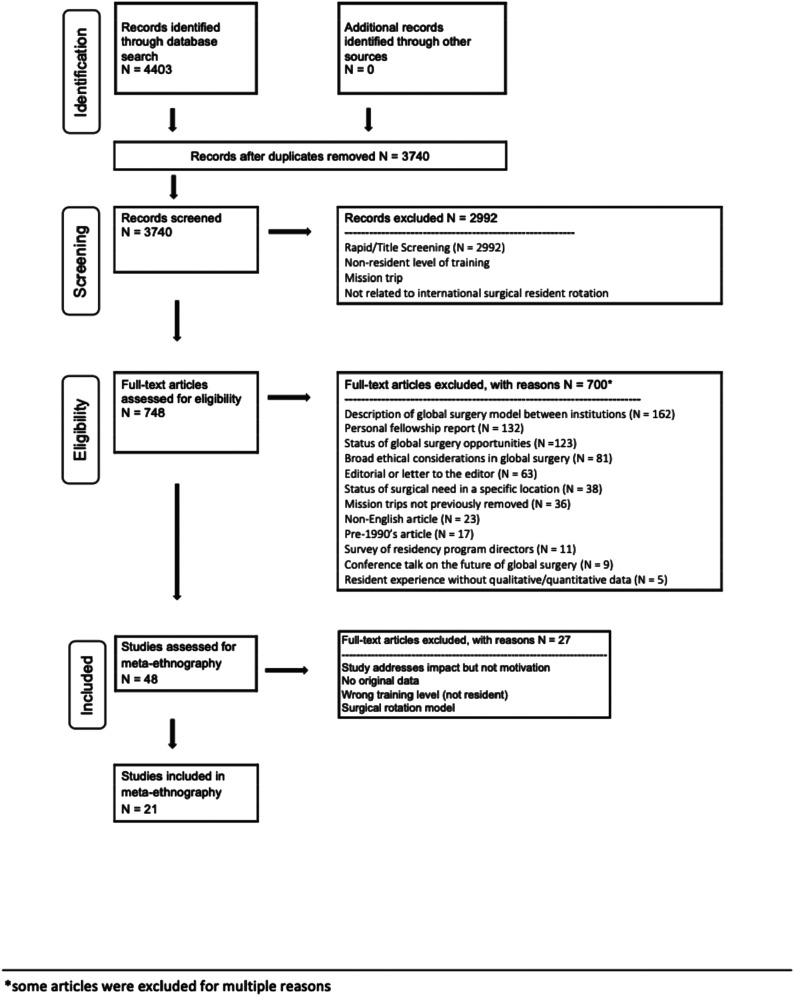

We searched the following databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scielo, IRIS, AIM African Index Medicus, LILACS, Asia Journals Online, and Africa Journals Online (Appendix A) for articles related to international resident rotations. This search strategy, last run in September of 2019, identified 4,403 articles, of which 3,740 were unique and screened for eligibility. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram18 details the number of articles retrieved and excluded at each stage of the review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A PRISMA flow diagram for systematic review. This workflow shows the steps of article screening, article inclusion and exclusion, and data extraction. Each step completed in duplicate.

Study Identification

Two authors (C.A.D. and N.W.) screened titles and abstracts using DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada). These 2 authors then assessed the full-text articles of eligible studies for final inclusion. Consensus was achieved through discussion.

Eligibility Criteria

Title and abstract screening inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) articles that pertain to HIC surgical resident rotations in an LMIC, (2) include resident motivations for participating in an overseas rotation, or (3) incorporate the LMIC host perspective on HIC collaborations. Exclusions were made by full-text screening to eliminate articles that were as follows: (1) published before 1990, (2) ethical considerations of global surgery without empirical data, (3) conference notes or residency program director surveys, (4) narrative accounts of an LMIC experience, (5) HIC group visits lasting less than 1 month, (6) descriptions of a model between 2 institutions, or (7) case log reviews and status of LMIC surgical need. A full list of exclusion criteria is included in Fig. 1.

Data Extraction for Meta-Ethnography

Two authors (C.A.D. and N.W.) identified key findings from the included articles via a meta-ethnographic methodology19,20. Analogous to meta-analysis in quantitative research19,21, meta-ethnography is a tool for synthesizing the results of qualitative studies22,23. It involves a process of determining the interrelatedness of qualitative or semiqualitative studies, intuitively categorizing similar key findings termed “first-order concepts,” making interpretive groups of these categories termed “second-order concepts,” and defining these groupings in a manner that best captures their collective meaning20,24. The role of second-order concepts is to categorize and thus extend first-order interpretations beyond what can directly be extracted from the original studies23.

Table I shows each study's population, country of origin, and data collection instruments. Owing to heterogeneity within studies, LMIC rotation site was not included in our analysis. The “Primary Findings” column of Table I preserves the terminology used in the original articles.

TABLE I.

Study Information*

| Section 1.1. HIC Resident Motivations for Seeking LMIC Rotation | ||||

| Author | Study Population | Country/World Health Organization (WHO) Income Level | Data Collection Instrument | Primary Findings |

| Barton et al. 200725 | 103 general surgery residents | Canada/HIC | Electronic survey | Operating, travel, learning, and teaching |

| Cheung et al. 201726 | 61 general surgery residents | US/HIC | Electronic survey | Clinical experience, research, and training the local population |

| Disston et al. 200927 | 31 orthopaedic surgery residents† | US/HIC | Electronic survey | Opportunity to serve a less privileged population, desire for cross-cultural experience, and limited-resource setting |

| Javidnia et al. 201128 | 53 ear nose throat residents | Canada/HIC | Electronic survey | Contribute to an important cause, personal growth, learn about medicine in developing countries, travel, and improve understanding of other cultures |

| Johnston et al. 201829 | 74 surgical residents | US/HIC | Paper survey | Giving back by participating on surgical, medical, or disaster relief missions, long-term career goals, and religious motivation |

| Matar et al. 201230 | 361 general and orthopaedic surgery residents | Canada/HIC | Electronic survey | Contribute to an important cause, enhance technical/clinical skills, tourism/cultural enhancement, determine interest in international volunteerism, exposure to uncommon pathologies, teaching, and establishing contacts abroad |

| Pope et al. 201631 | 278 obstetrics, gynecology residents | US/HIC | Electronic survey | Promote maternal survival, research social determinants of health, and health policy |

| Powell et al. 200732 | 52 general surgery residents | US/HIC | Electronic survey | Technical/clinical skills, cultural experience, personal goals, language skills, altruism, and international contacts |

| Powell et al. 20093‡ | 724 surgical residents | US/HIC | Electronic survey | Cultural experience, technical/clinical skills, fulfilling personal goals, altruism, language skills, and international contacts |

| Sawatsky et al. 201633 | 377 reflective reports from residents | US/HIC | Qualitative analysis |

|

| Stagg et al. 201734 | 4,926 obstetrics and gynecology (OBGYN) residents | US/HIC | Electronic survey | Education, practicing medicine in other countries, full OBGYN experience, humanitarian opportunity, cultural competency, and “chance to see the world” |

| Zhang et al. 201635 | 122 orthopaedic surgery residents | US/HIC | Electronic survey | Contribute to care for the underserved, improve communication skills, physical exam and surgical techniques and resource allocation, and improve knowledge base with pathology not commonly seen in the United States |

| Section 1.2. Self-Described Impact of LMIC Rotation on HIC Residents | ||||

| Author | Study Population | Country/WHO Income Level | Data Collection Instrument | Primary Findings |

| Graf et al. 201736 |

|

US and Israel/HIC | Qualitative analysis of resident reports and electronic survey | Positive learning experience, exposure to new pathology and disease, and development of close relationships. Difficulty functioning with limited language proficiency and emotional challenges of dealing with different standards of care |

| Henry et al. 201237 | 14 surgical residents# | US/HIC | Electronic survey/qualitative analysis of free text |

|

| Jafari et al. 201738 | 44 residents, 8 fellows** | Multiple/HIC | Electronic survey | Residents believed that the experience was life-changing and confirmed their passion for surgery |

| Kelley et al. 201539 | 21 current/former surgical residents | Canada/HIC | Electronic survey | Helped residents grow as physicians and develop new appreciation for their home health care system and public health. Improved managerial skills, creativity, and resourcefulness. |

| Tarpley et al. 201340 | 9 4th year residents returning from 4-week surgical rotation in Kenya | US/HIC | Survey and discussion | Opportunity to work with LMIC residents and care for patients in a resource-challenged environment. Challenged by language differences, unfamiliar clinical issues, and adjusting to different medical environment. |

| Section 1.3. LMIC Host Perspective of HIC Collaboration | ||||

| Author | Study Population | Country/WHO Income Level | Data Collection Instrument | Primary Findings |

| Cadotte et al. 201441 |

|

Ethiopia/LMIC and Canada, US, Norway††/HIC | In-person open-ended interviews | HIC mentorship of LMIC trainees is valuable if sustained. Do not undermine authority of local healthcare providers. |

| Elobu et al. 201442 | 33 “postgraduate trainees” in anesthesia and surgery at single institution | Uganda/LMIC | Paper survey | Value in internationally organized surgical skill workshops and specialist camps. International groups had a neutral or negative impact on patient care and questioned the ethics of clinical decisions made by visiting faculty. Research projects are often conducted without crediting LMIC authors and are not in locally identified priority areas. |

| Ibrahim et al. 201527 | 13 HIC surgeons, 18 LMIC surgeons | Multiple HICs and LMICs | In-person and online semi-structured interviews | Need to monitor and evaluate longitudinal success of international collaboration and impact on local community with broad regional and national indicators. |

| O’Donnell et al. 201458 | 3 department chairs, 6 residents, 15 attending physicians of EM medicine | Peru/LMIC | Semi-structured interviews |

|

HIC = High Income Country; LMIC = Low-, Middle-Income Country.

Completed survey in June, immediately after graduation.

Follow-up study to Powell et al. 2007 with expanded study population.

Included here with “motivations,” see also section 1.2.

Study included attending surgeons and medical students, but stratified the responses, enabling inclusion.

Responses from residents and fellows were not separated.

Could not exclude HIC neurosurgeons (even though faculty) as thematic analysis did not separate out responses.

Studies were categorized as follows (Table I): (1) HIC resident motivation for seeking LMIC rotation (section 1.1), (2) self-described impact of LMIC rotation on HIC residents (section 1.2), and (3) LMIC host perspective of HIC collaboration (section 1.3).

Results

Of 3,740 articles, 21 were included in the final analysis: 12 that addressed HIC resident motivations for participation in LMIC rotations, 6 that addressed the impact on HIC residents of rotations in LMICs (one study was co-listed), and 4 that addressed the LMIC host perspective. None of these 4 were specific to orthopaedics, and all discussed both surgical resident rotations and general HIC collaboration. To our knowledge, there are no publications that exclusively address LMIC host perspectives of HIC surgical resident rotations. Included studies used both qualitative and quantitative methods. First- and second-order concept groupings reported in Tables II–IV are first organized by benefit or harm and then ordered by the descending frequency.

TABLE II.

| First-Order Concept Grouping | Scope of Concept | Second-Order Concept Grouping |

| Altruism |

|

Find meaning: Residents anticipated that practicing medicine in resource-austere environment would provide them with a sense of humanitarianism, meaning, purpose, or fulfillment beyond what was typical in their home institutions |

| Fulfillment |

|

|

| Religion |

|

|

| Operative experience |

|

Professional development: Residents anticipated that practicing surgery within a new, LMIC hospital setting might present developmental opportunities beyond those available at their home institutions |

| Career advancement |

|

|

| Novel pathology |

|

|

| Research |

|

|

| Cultural awareness |

|

Personal experience: Residents anticipated that conducting surgical interventions in an LMIC setting might allow them to experience a new culture and learn about the people and practice of healthcare in other countries |

| Travel |

|

|

| Contextualize health care systems |

|

|

| Language |

|

|

| Professional collaboration |

|

Engage in collaboration: Residents anticipated that rotating in an LMIC might provide a purpose and joy for both the host and visiting surgeons and that with thoughtful management such relationships might grow and deepen over time |

| Teaching |

|

|

| Friendship |

|

|

| Capacity building |

|

This table was first grouped into potential benefits (4) and potential harm (0) and then ordered by frequency, with concepts that received the most mentions across included papers listed first. Lines delineate unique second-order concepts encapsulating first-order groupings.

HIC = High-Income Country; LMIC = Low-, Middle-Income Country.

TABLE III.

| First-Order Concept Grouping | Scope of Concept | Second-Order Concept Grouping |

| Learning in a unique environment |

|

Professional development: practicing surgery in an LMIC hospital setting may present developmental opportunities for residents beyond what they have access to at their home institutions |

| Positively challenged |

|

|

| Exposed to novel pathology |

|

|

| Greater responsibility |

|

|

| Trained with different methodologies |

|

|

| Fulfillment |

|

Finding meaning: residents describe the relationships they have with their patients and friendships they develop with LMIC colleagues as providing meaning and fulfillment beyond what they experience at their home institutions |

| Rejuvenation of purpose |

|

|

| Friendship |

|

|

| Global sensitization |

|

Awareness of global inequity: residents emerge from global surgery rotations with a greater appreciation for the social determinants of health, scarcity of care for the high burden of surgical disease and improved cultural awareness, understanding of, and commitment to global surgery equity |

| Cultural awareness |

|

|

| Ethical concerns |

|

Feeling ineffective: developing an awareness of self-limitations and need of navigating culture and protocol differences that can be frustrating and emotionally draining |

| Recognition of internal expectations for standards of care |

|

|

| Underpreparedness |

|

|

| Awareness of professional role |

|

This table was first grouped into potential benefits (3) and potential harm (1) and then ordered by frequency, with concepts that received the most mentions across included articles listed first. Lines delineate unique second-order concepts encapsulating first-order groupings.

HIC = High-Income Country; LMIC = Low-, Middle-Income Country.

TABLE IV.

| First-Order Concept Grouping | Scope of Concept | Second-Order Concept Grouping |

| Sustained collaboration |

|

Sustained investment in Education: LMIC residents benefit from international collaboration when such collaborations are sustained and include new educational development |

| Educational exchange |

|

|

| Limited impact on patient care |

|

Systems-level discordance: organizations must thoughtfully implement LMIC collaborations, including coordinating with other international groups that may be working out of the same host site, involving local healthcare providers, assessing and adjusting to meet local needs, and developing protocols for assessing potential impact |

| Unmet local needs |

|

|

| Harmful effects of multiple visiting groups |

|

|

| Undermined authority |

|

|

| Limited reciprocity |

|

Individual-level discordance: individual actions, including not providing credit to local healthcare providers for their work and lack of cultural awareness or sensitivity from HIC visitors may damage relationships within a host institution |

| Resident effectiveness limited by underpreparedness |

|

|

| Ethical concerns |

|

This table was first grouped into potential benefits (1) and potential harm (2) and then ordered by frequency, with concepts that received the most mentions across included articles listed first. Lines delineate unique second-order concepts encapsulating first-order groupings.

HIC = High-Income Country; LMIC = Low-, Middle-Income Country.

HIC Resident Motivations for LMIC Rotations

Fifteen first-order concepts were synthesized from HIC resident-reported surveys and descriptive responses. These first-order concepts were thematically grouped into 4 second-order concepts (Table II):

-

•

Potential benefits: finding meaning, professional development, personal experience, and engage in collaboration

-

•

Potential harm: not identified

The motivation for HIC resident participation in LMIC rotations cited by the most studies was altruism.

Self-Identified Impact of LMIC Rotations on HIC Residents

Fourteen first-order concepts were grouped into 4 second-order concepts (Table III):

-

•

Potential benefits: professional development, finding meaning, and developing awareness of global inequity

-

•

Potential harm: feeling ineffective

The impact of LMIC rotations on HIC residents most frequently cited was finding mentorship in a unique environment.

LMIC Host Perspective on the Impact of HIC Resident Rotations and Collaboration

All studies that addressed the LMIC perspective did so through interviews with LMIC surgeons (faculty and residents). From these, 9 first-order concepts were identified and synthesized into 3 second-order concepts (Table IV):

-

•

Potential benefit: sustained investment in education

-

•

Potential harm: systems-level and individual-level discordance between HIC and LMIC expectations

Sustained HIC collaboration was the most frequently cited theme.

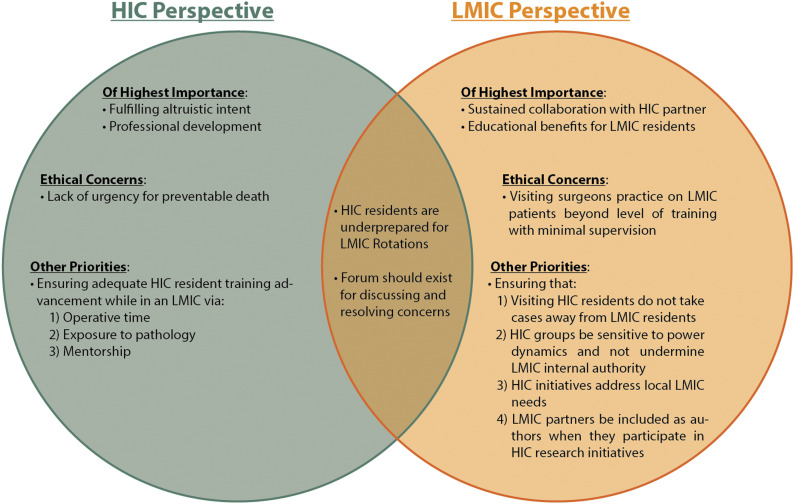

The concordance and discordance between major themes identified from the HIC perspective and LMIC perspective is represented in a Venn diagram (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Concordance and discordance of HIC and LMIC perspectives. Categorization of concordance and discordance between themes identified by HIC and LMIC partners. HIC = High-Income Country and LMIC = Low-, Middle-Income Country.

Discussion

This study synthesizes available literature on HIC surgical resident motivations for rotating in LMICs, the impact on residents of these rotations, and the LMIC host perception of collaboration. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to interpret data on surgical resident rotations in LMICs. Despite strong interest in these rotations from orthopaedic programs2,3,8, literature reporting their motivations and impact is sparse. Thus, for this analysis, we included surgical resident rotations beyond orthopaedics to identify practices that minimize harm and share benefits with LMIC partners43,44.

The available data from the LMIC perspective shows that the most important component of HIC collaboration is sustained investment. Because any HIC collaboration requires significant LMIC host investment, a commensurate, long-term HIC investment is warranted. As one LMIC partner states, “It’s not worth it to come back for one second and say a few things and leave. The person has to come on a slightly regular basis, maybe once a year”45. Strong models of longitudinal partnerships in the orthopaedic literature46-49 are considerate of LMIC capacity, including adequate surgical volume and faculty supervision to support visiting residents, and to ensure that residents operate within their training level46,47,50,51. These models rely on ongoing interest and investment of both LMIC and HIC orthopaedic faculty, and designated LMIC and HIC program director responsible for ongoing management46,47,50,51. Once established, monitoring and evaluating the longitudinal success of these collaborations is beneficial.

In addition to sustained investment, LMIC partners benefit most when programs are designed as bidirectional educational exchanges rather than merely HIC resident training opportunities. Although LMIC residents would likely benefit most from a true bidirectional relationship in which residents from each institution “swap,” a more limited bidirectional model that instead emphasizes local capacity maintains advantages for both stakeholders52. In the words of one LMIC surgeon, “Try not to replace the local doctor, because you’re going to leave”44. For orthopaedic residency programs, this means the following: (1) preferentially sending residents of higher training level, (2) ensuring residents receive the best possible pretrip preparation, and (3) investing in local capacity. Capacity building may include HIC faculty mentorship for LMIC residents, incorporating LMIC training and surgical education opportunities, and encouraging HIC residents to ask how they can be helpful to LMIC hosts49,53. Under appropriate LMIC directorship, HIC residents have opportunities to meaningfully channel their desire to help and can contribute substantively. Furthermore, global networks developed through these educational exchanges may further global interest in locally identified but poorly recognized disease burden.

Despite extensive literature devoted to the development of resident “guides” or recipes for success14,54-56, HIC residents believed and LMIC hosts agreed that HIC residents were underprepared for their LMIC rotations and required increased supervision, often because of poor patient-surgeon communication or surgeon-surgeon communication. In addition, HIC residents of all training levels often assumed authority and the ability to teach or provide training where perhaps they should not. From this, 3 categories for improvement emerged: that residents (1) receive site-specific preparation from experienced individuals prior to departure; (2) remain in country long enough to integrate into the environment, and develop a working knowledge of the local system, pathology, and surgical procedures; and (3) cultivate flexibility, particularly in recognizing that despite their training, they will not be local experts57. As one LMIC surgeon notes, “…you should not seek to learn how to practice medicine, but instead learn how medicine is practiced in another country”58. Although flexibility is an essential skill in all orthopaedic residents59,60, on LMIC rotations “flexibility” means being receptive and responsive to feedback from LMIC partners, recognizing your limitations, being open to learning, and being willing to change. Because of the lack of data, this review reveals no definite answer as to what in-country rotation length would be optimal for both HIC residents and LMIC partners. Although the Residency Review Committee (RRC) defines the minimum resident elective as one month60, LMIC partners note that this is too short for residents to substantively contribute45, unless their rotation is a component of a larger, sustained partnership between institutions9,61. If HIC residents wish to stay longer at an LMIC site, the RCC denotes no maximum time for elective rotations, but residents may be limited by financial constraints and difficulty fulfilling their minimum 60-month Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) training requirement60.

The idea of resident flexibility may be incorporated into pretrip planning by establishing reasonable resident expectations. Our study identifies that surgical residents are highly motivated by increasing their exposure to surgical pathology and are eager to operate on interesting cases. However, there is an associated cost: LMIC residents then struggle to compete with HIC residents for cases and mentorship opportunities. This cost can be mitigated on 2 fronts: (1) at the systems-level, by ensuring that before initiating a partnership, an LMIC institution has the surgical volume to accommodate visiting residents, and (2) at the individual-level, by ensuring that HIC residents are prepared to respectfully share cases and training opportunities with LMIC residents.

An additional component of pretrip expectation is developing an awareness of how personal motivations for going on an LMIC rotation may affect behavior. Altruistic intent was the most commonly reported HIC resident motivation for an LMIC surgical rotation. As one HIC surgeon notes, “When we go [to an LMIC institution], we don’t just go to help the patients, we go to help society”45. This desire to help, or affect change, is laudable62. However, this “altruistic intent” is often a generalized, intangible idea of what may be helpful without a realistic understanding of LMIC institution needs. Unchecked altruistic intent may lead to a belief that visitors can “fix things” where less competent others have failed, lacking recognition that doing so may undermine local authority57 and permanently damage relationships with LMIC hosts. As one Ghanaian nurse noted, “[HIC visitors] don’t take our advice, or if you tell them something, they think they know better than us and that is not good”44. For orthopaedic residents, this means having the humility to recognize personal and system-level limitations, even at the oft-reported cost of feeling ineffective. Working as an HIC visitor in an LMIC surgery program demands that residents have the emotional maturity to orient to the “big picture” without abandoning the desire for continued improvement essential for all parties in a longitudinal surgical training partnership. In our review, we chose the terminology “cultural humility” over “cultural competence” to incorporate ongoing discussions of cultural understanding63-65 within resident training because it encompasses awareness of power dynamics and emphasizes a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation, improvement, and partner advocacy.

Finally, one pitfall in setting up resident rotations resulted from the absence of a framework for addressing and resolving concerns. Both HIC and LMIC surgeons expressed concern regarding the ethics of the other party. HIC residents reported that LMIC hosts lacked urgency for preventable death. This perception may arise when visiting residents are unaware of the systemic issues that lead to this perceived “lack of urgency,” including insufficient resources or oversight45. Conversely, LMIC hosts believed as though visiting surgeons used LMIC patients to gain experience or practice new techniques beyond their training level, an ethical concern that has been acknowledged from the HIC perspective17. As both parties concede that these ethical concerns are valid, orthopaedic residency programs may incorporate discussion forums for surgeon accountability and patient outcome measures. As noted by one LMIC surgeon, “…we just have to once in a while sit down and discuss things…and what needs to be changed”45. HIC resident concerns may be mitigated by setting appropriate expectations, including awareness of the resource limitations that are beyond the control of LMICs. Directors from resident rotation sites, both HIC and LMIC, may provide opportunities for feedback regarding resident rotations and other aspects of partnership, sharing this information to address concerns as they arise. To best determine the impact of visiting surgeons on patient care, it may be helpful to establish outcome measures toward monitoring the effect of overseas clinical rotations on the local LMIC community.

There are several limitations to our study. All meta-ethnographies assume that the results of each study are generalizable19. Although the studies included in this work overlap in setting and methodology (Table I), they differ in LMIC location, support of HIC residents, and human factors; thus, these data may not be commensurable. In addition, in keeping with 2019 ACGME guidelines60, only articles describing resident rotations of at least 1-month duration were included; all other accounts of orthopaedic studies, mission trips, and general volunteerism were omitted. Although mission trips and other short-term trips make up a substantive proportion of global health initiatives and literature (our review excluded nearly 1,000 studies based on this criteria), the extreme heterogeneity of such trips makes it challenging to draw meaningful conclusions. Although we recognize that the distinction between a mission trip and a resident rotation may not be easily defined, broadly we noted that mission trips have much greater variability in personnel, training level, involvement of local stakeholders, length of stay, and trip purpose. With no meaningful ways of stratifying these trips and relating to resident rotations, we chose to exclude them.

In addition, the LMIC stakeholder perspective is limited by the lack of published literature, with only 4 LMIC-perspective studies involving surgical residents identified through this review. Even research that directly queries LMIC providers often uses survey instruments developed by HIC researchers without input from their LMIC counterparts, likely introducing HIC-perspective bias into the study design. A much greater effort is needed to address the striking absence of the LMIC perspective throughout the global health literature.

Conclusion

Orthopaedic resident interest in LMIC rotations continues to grow2,3,8, an unsurprising trend considering the opportunities it affords HIC residents to honor their humanitarian ideals through immersive exposure to a new pathology and surgical technique. This article highlights several points on HIC surgical resident rotations in LMICs and the need for future orthopaedic research on this topic, particularly from the LMIC perspective. As HIC orthopaedic residency programs create LMIC rotations for their residents, careful consideration of sustainable investment, bidirectional educational exchange, and prerotation orientation may improve the overall value of collaboration for both stakeholders. A foundation of analysis, planning, and preparation may render LMIC/HIC orthopaedic residency training partnerships beneficial to all parties and their patients and build within HIC residents a lifelong commitment to global and equitable partnerships.

Appendix

Supporting material provided by the authors is posted with the online version of this article as a data supplement at jbjs.org (http://links.lww.com/JBJSOA/A184).

Acknowledgments

Note: The authors are grateful for the assistance of librarian Evans Whitaker, MD, MLIS, who was instrumental in the development of a comprehensive and appropriately scoped search criteria.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California

Disclosure: The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJSOA/A183).

References

- 1.Asgary R, Junck E. New trends of short-term humanitarian medical volunteerism: professional and ethical considerations. J Med Ethics. 2013;39(10):625-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shultz PA, Kamal RN, Daniels AH, DiGiovanni CW, Akelman E. International health electives in orthopaedic surgery residency training. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol. 2015;97(3):e15(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powell AC, Casey K, Liewehr DJ, Hayanga A, James TA, Cherr GS. Results of a national survey of surgical resident interest in international experience, electives, and volunteerism. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(2):304-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler MW, Krishnaswami S, Rothstein DH, Cusick RA. Interest in international surgical volunteerism: results of a survey of members of the American Pediatric Surgical Association. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(12):2244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miclau T, MacKechnie MC, Shearer DW. Consortium of orthopaedic academic traumatologists: a model for collaboration in orthopaedic surgery. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(10):3-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook M, Howard BM, Yu A, Grey D, Hofmann PB, Moren AM, McHembe M, Essajee A, Mndeme O, Peck J, Schecter WP. A consortium approach to surgical education in a developing country: educational needs assessment. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(11):1074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA, Bickler SW, Conteh L, Dare AJ, Davies J, Mérisier ED, El-Halabi S, Farmer PE, Gawande A, Gillies R, Greenberg SLM, Grimes CE, Gruen RL, Ismail EA, Kamara TB, Lavy C, Lundeg G, Mkandawire NC, Raykar NP, Riesel JN, Rodas E, Rose J, Roy N, Shrime MG, Sullivan R, Verguet S, Watters D, Weiser TG, Wilson IH, Yamey G, Yip W. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. 2015;386(9993):569-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan B, Zhao C, Sabharwal S. International elective during orthopaedic residency in north America: perceived barriers and opportunities. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol. 2015;97(1):e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozgediz D. Surgical training and global health. Arch Surg. 2008;143(9):860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schultz IZ, Editors RJG. Handbook of Return to Work from Research to Practice Handbooks in Health, Work, and Disability. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Love TP, Martin BM, Tubasiime R, Srinivasan J, Pollock JD, Delman KA. Emory global surgery program: learning to serve the underserved well. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(4):e46-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin BM, Love TP, Srinivasan J, Sharma J, Pettitt B, Sullivan C, Pattaras J, Master VA, Brewster LP. Designing an ethics curriculum to support global health experiences in surgery. J Surg Res. 2014;187(2):367-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aluri J, Moran D, Kironji AG, Carroll B, Cox J, Chen CCG, Decamp M. The ethical experiences of trainees on short-term international trips: a systematic qualitative synthesis. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meier DE, Fitzgerald TN, Axt JR. A practical guide for short-term pediatric surgery global volunteers. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51(8):1380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimes CE, Maraka J, Kingsnorth AN, Darko R, Samkange CA, Lane RHS. Guidelines for surgeons on establishing projects in low-income countries. World J Surg. 2013;37(6):1203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipnick M, Mijumbi C, Dubowitz G, Kaggwa S, Goetz L, Mabweijano J, Jayaraman S, Kwizera A, Tindimwebwa J, Ozgediz D. Surgery and anesthesia capacity-building in resource-poor settings: description of an ongoing academic partnership in Uganda. World J Surg. 2013;37(3):488-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramsey KM, Weijer C. Ethics of surgical training in developing countries. World J Surg. 2007;31(11):2067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzshe PC, Loannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):50931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Myfanwy Morgan RP. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Pol. 2002;7(4):209-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkins S, Lewin S, Smith H, Engel M, Fretheim A, Volmink J. Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: lessons learnt. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schutz A. Collected Papers. Vol 1 The Hague, the Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandahl J. Preparing for citizenship: the value of second order thinking concepts in social science education. J Soc Sci Educ. 2015;14(1):19-30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feast A, Orrell M, Charlesworth G, Poland F, Featherstone K, Melunsky N, Moniz-Cook E. Using meta-ethnography to synthesize relevant studies: capturing the bigger picture in dementia with challenging behavior within families. Sage Res Methods Cases. 2018. doi: 10.4135/9781526444899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barton A, Williams D, Beverldge M. A survey of Canadian general surgery residents' interest in international surgery. Can J Surg. 2008;51(2):125-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung M, Healy JM, Hall MR, Ozgediz D. Assessing interest and barriers for resident and faculty involvement in global surgery. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(1):49-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Disston AR, Martinez-Diaz GJ, Raju S, Rosales M, Berry WC, Coughlin RR. The international orthopaedic health elective at the University of California at San Francisco: the eight-year experience. J Bone Joint Surg Ser A. 2009;91(12):2999-3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Javidnia H, McLean L. Global health initiatives and electives: a survey of interest among Canadian otolaryngology residents. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;40(1):81-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston PF, Scholer A, Bailey JA, Peck GL, Aziz S, Sifri ZC. Exploring residents' interest and career aspirations in global surgery. J Surg Res. 2018;228:112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matar WY, Trottier DC, Balaa F, Fairful-Smith R, Moroz P. Surgical residency training and international volunteerism: a national survey of residents from 2 surgical specialties. Can J Surg. 2012;55(4 Suppl. 2):191-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pope R, Shaker M, Ganesh P, Larkins-Pettigrew M, Pickett SD. Barriers to global health training in obstetrics and gynecology. Ann Glob Heal. 2016;82(4):625-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Powell AC, Mueller C, Kingham P, Berman R, Pachter HL, Hopkins MA. International experience, electives, and volunteerism in surgical training: a survey of resident interest. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(1):162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sawatsy AP, Nordhues HC, Merry SP, Bashir MU, Hafferty F. Why I went into medicine: using transformative learning theory to understand the impact of international health electives on residents' professional identity formation. In: Abstracts from the 2016 Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting. 2016. p. S87.

- 34.Stagg AR, Blanchard MH, Carson SA, Peterson HB, Flynn EB, Ogburn T. Obstetrics and gynecology resident interest and participation in global health. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(5):911-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang S, Shultz P, Daniels A, Akelma E, Kamal RN. High disparity between orthopedic resident interest and participation in international health electives. Orthopedics. 2016;39(4):e680-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graf J, Cook M, Schecter S, Deveney K, Hofmann P, Grey D, Akoko L, Mwanga A, Salum K, Schecter W. Coalition for global clinical surgical education: the alliance for global clinical training. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(3):688-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henry JA, Groen RS, Price RR, Nwomeh BC, Kingham TP, Hardy MA, Kushner AL. The benefits of international rotations to resource-limited settings for U.S. surgery residents. Surg (United States). 2013;153(4):445-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jafari A, Tringale KR, Campbell BH, Husseman JW, Cordes SR. Impact of humanitarian experiences on otolaryngology trainees: a follow-up study of travel grant recipients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(6):1084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly K, McCarthy A, McLean L. Distributed learning or medical tourism? A Canadian residency program's experience in global health. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(4):e33-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarpley M, Hansen E, Tarpley JL. Early experience in establishing and evaluating an ACGME-approved international general surgery rotation. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(6):709-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cadotte DW, Sedney C, Djimbaye H, Bernstein M. A qualitative assessment of the benefits and challenges of international neurosurgical teaching collaboration in Ethiopia. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(6):980-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elobu AE, Kintu A, Galukande M, Kaggwa S, Mijjumbi C, Tindimwebwa J, Roche A, Dubowitz G, Ozgediz D, Lipnick M. Evaluating international global health collaborations: perspectives from surgery and anesthesia trainees in Uganda. Surg (United States). 2014;155(4):585-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wassef DW, Holler JT, Pinner A, Challa S, Xiong M, Zhao C, Sabharwal S. Perceptions of orthopaedic volunteers and their local hosts in low- and middle-income countries. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(10):S29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lasker JN. Hoping to Help: The Promises and Pitfalls of Global Health Volunteering. In: Gordon S, Nelson S, eds. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ibrahim GM, Cadotte DW, Bernstein M. A framework for the monitoring and evaluation of international surgical initiatives in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Conway DJ, Coughlin R, Caldwell A, Shearer D. The institute for Global orthopaedics and traumatology: a model for academic collaboration in orthopaedic surgery. Front Public Heal. 2017;5:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderson LA, Bernthal NM, Haller JM, Higgins TF, Elliott IS, Anderson DR. Partnership in Ethiopia. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(10):S12-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siy AB, Lins LA, Dahm JS, Shaw JT, Simske NM, Noonan KJ, Whiting PS. Availability of global health opportunities in North American paediatric orthopaedic fellowship programmes. J Child Orthop. 2018;12(6):640-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Belding R, Grabowski G, Williams K, Mobley K, Bray C, Woolf S, Jumelle P, Koon D. The Haitian orthopaedic residency exchange program. JAAOS Glob Res Rev. 2019;3(8):e027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Phillips J, Jergesen HE, Caldwell A, Coughlin R. IGOT-the institute for global orthopaedics and traumatology: a model for collaboration and change. Tech Orthop. 2009;24(4):308-11. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu HH, Ibrahim J, Conway D, Liu M, Morshed S, Miclau T, Coughlin RR, Shearer DW. Clinical research course for international orthopaedic surgeons. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(10):S35-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woolley PM, Hippolyte JW, Larsen H. What's important: teching us how to fish. J Bone Joint Surg. 2019;101:1411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carey JN, Caldwell AM, Coughlin RR, Hansen S. Building orthopaedic trauma capacity: IGOT international SMART course. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(10):S17-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Furey A, OʼHara NN, Marshall E, Pollak AN. Practical guide to delivering surgical skills courses in a low-income country. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(10):S18-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leow JJ, Groen RS, Kingham TP, Casey KM, Hardy MA, Kushner AL. A preparation guide for surgical resident and student rotations to underserved regions. Surg. 2012;151(6):770-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goecke ME, Kanashiro J, Kyamanywa P, Hollaar GL. Using CanMEDS to guide international health electives: an enriching experience in Uganda defined for a Canadian surgery resident. Can J Surg. 2008;51(4):289-95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahmad AA. What's important: recognizing local power in global surgery. J Bone Joint Surg. 2019;101:1974-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O'Donnell S, Adler DH, Inboriboon PC, Alvarado H, Acosta R, Godoy-Monzon D. Perspectives of South American physicians hosting foreign rotators in emergency medicine. Int J Emerg Med. 2014;7(1):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. How to obtain an orthopaedic residency. Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997:1-6. Available at: https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/about/diversity/how-to-obtain-an-orthopaedic-residency.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in orthopaedic surgery. 2019. 1-23. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tocco-Tussardi I, Boccella S, Bassetto F. The instructional value of international surgical volunteerism from a resident's perspective. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2016;29(2):146-50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elliott IS, Sonshine DB, Akhavan S, Slade Shantz A, Caldwell A, Slade Shantz J, Gosselin RA, Coughlin RR. What factors influence the production of orthopaedic research in East Africa? A qualitative analysis of interviews. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2120-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Foronda C, Baptiste DL, Reinholdt MM, Ousman K. Cultural humility: a concept analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(3):210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greene-Moton E, Minkler M. Cultural competence or cultural humility? Moving beyond the debate. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21(1):1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9(2):117-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]