Abstract

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has resulted in a global pandemic, prompting unprecedented efforts to contain the virus. Many developed countries have implemented widespread testing and have rapidly mobilized research programmes to develop vaccines and therapeutics. However, these approaches may be impractical in Africa, where the infrastructure for testing is poorly developed and owing to the limited manufacturing capacity to produce pharmaceuticals. Furthermore, a large burden of HIV-1 and tuberculosis in Africa could exacerbate the severity of infection and may affect vaccine immunogenicity. This Review discusses global efforts to develop diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines, with these considerations in mind. We also highlight vaccine and diagnostic production platforms that are being developed in Africa and that could be translated into clinical development through appropriate partnerships for manufacture.

Subject terms: Medical research, Vaccines, Infectious-disease diagnostics, Viral infection

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted unparalleled progress in the development of vaccines and therapeutics in many countries, but it has also highlighted the vulnerability of resource-limited countries in Africa. Margolin and colleagues review global efforts to develop SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines, with a focus on the opportunities and challenges in Africa.

Introduction

Coronaviruses are ubiquitous RNA viruses that are responsible for endemic infections in humans and other animals, and sporadic outbreaks of potentially fatal respiratory disease in humans. Four human coronaviruses, namely HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1, circulate in the human population, causing the common cold, with some causing potentially life-threatening disease in infants, young children, older individuals and individuals who are immunocompromised1. In the recent past, two additional coronaviruses have crossed the species barrier from other animals to infect humans. These are severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which emerged in 2002 and 2012, respectively2,3. In December 2019, a novel betacoronavirus, subsequently named SARS-CoV-2, was implicated in an outbreak of respiratory disease in Wuhan, China4. The first cases to be reported presented as atypical pneumonia and were traced to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, although cases without any association with the market, and predating the putative index cases, were subsequently recognized. Following these first reports, community transmission rapidly ensued, culminating in a global pandemic5,6.

The virus is speculated to have originated in bats and possibly to have passed through another host before infecting humans, but an intermediate host or intermediate hosts have yet to be defined. This remains the subject of considerable debate, and recent work suggests that the host receptor-binding motif of SARS-CoV-2 was acquired through recombination with a pangolin coronavirus7–9, but further work is needed to establish the origin of the virus. Infection with SARS-CoV-2 in humans manifests as coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), a spectrum of disease that ranges from asymptomatic infection to acute respiratory distress syndrome with multisystem involvement. Older individuals and individuals with co-morbidities are at greatest risk10. In individuals who are symptomatic, fever and cough are most commonly reported, although sore throat, shortness of breath, fatigue, anosmia, dysgeusia and gastrointestinal involvement are also frequently observed5,11. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19 are being increasingly recognized. Among adults with pre-existing diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis may be a common complication and is associated with a poor prognosis12,13. According to the International Diabetes Federation, Africa has an estimated 19.4 million adults aged between 20 and 79 years living with diabetes and is the region with the highest proportion of undiagnosed diabetes14. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications have also been recognized as presenting or complicating factors15. Children generally have a milder course of disease and are more likely to be asymptomatic, although recent reports have described hyperinflammatory shock in children who were previously asymptomatic that seems similar to Kawasaki disease16–18. Further studies are required to determine the prevalence of this phenomenon and to define the immunological drivers of the illness. However, the contrasting presentation of COVID-19 in children and adults suggests that the immune responses of children and adults to SARS-CoV-2 may be different.

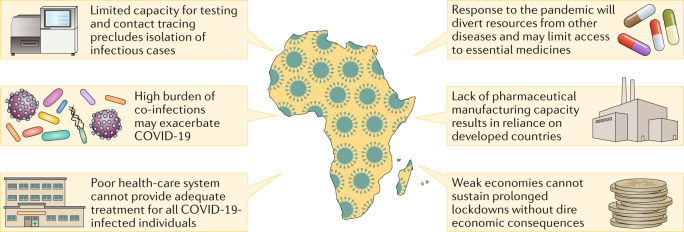

The virus continued to spread globally, prompting the implementation of radical travel restrictions and social distancing measures19. At the time of writing this article, the virus has resulted in over 25 million confirmed infections and has claimed the lives of over 850,000 people6. As of 8 August 2020, there have been over 1.2 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Africa, with 29,833 deaths reported (Africa CDC) There is concern that the pandemic may pose an even greater risk to countries in Africa owing to their weak health-care infrastructure, large burden of co-infections, including HIV-1 and tuberculosis, and ongoing outbreaks of emerging and re-emerging infections such as Ebola virus (Democratic Republic of Congo) and Lassa haemorrhagic fever (Nigeria) that will divert much-needed resources away from the fight against COVID-19 (ref.20) (Fig. 1). Differences in global population demographics and health status are also likely to affect the severity of the pandemic in different regions and are a major concern in Africa (Fig. 2). In addition to the health-care infrastructure, the general infrastructure throughout Africa is also highly variable, and thus access to appropriate medical care is an important determinant of COVID-19 disease outcome. The number of hospital beds in a population of 10,000 individuals varies from as low as 1 in Mali to 32 in Libya. However, Libya is an exception for the region, and many central and west African countries are at the lower end of this range and generally report fewer than 10 beds per 10,000 individuals. This is in stark contrast to other developed countries such as Germany and the USA, where 80 and 28.7 beds per 10,000 individuals are available, respectively. A similar trend is also seen for the number of doctors per 10,000 individuals. In more than 10 African countries, less than 1 doctor is available (per 10,000 individuals), whereas Germany and the USA report 42 and 26 doctors (per 10,000 individuals), respectively21.

Fig. 1. Challenges for African countries in their response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The limited capacity for testing and contact tracing, poor health-care systems, lack of pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity and underdeveloped infrastructure in Africa pose several challenges that constrain the response of the region to the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This is worsened by the high burden of infectious diseases, which may worsen disease outcome and compete for the available resources. A further challenge is the dire economic consequences of prolonged lockdowns in countries with weak economies.

Fig. 2. Global population demographics and health-care status underscore important risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease.

Population demographics and prevalence of known co-morbidities for each of the six World Health Organization regions. Although Africa reports a lower average age compared with other regions, the burden of infectious disease is disproportionately high. Both HIV and tuberculosis are associated with an increase in coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) disease severity, and their prevalence in Africa will increase the risk of fatal infection for a large number of people. There is also a large proportion of individuals in Africa with raised blood pressure, which is a known risk factor for severe disease. Other known co-morbidities, including raised cholesterol, raised glucose and obesity, are less prevalent in Africa compared with the other reported regions. Raised blood pressure (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm/Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg), raised fasting blood glucose levels (≥7 mmol/l or taking medication), raised total cholesterol levels (≥5 mmol/l) and body mass index (BMI) >25 are reflected as age-standardized estimates. All data shown reflect the latest available data from the World Health Data Platform (Global Health Observatory). The number of people living with HIV-1/AIDS (in millions) reflects the population of individuals who were infected in 2018, tuberculosis cases shown reflect the number of incident cases in 2018 and malaria cases reflect the estimated number of cases in 2017.

Concerns have been raised regarding the impact of the pandemic on other diseases and access to essential medicines22. For example, according to a newspaper article, the Ministry of Health in Zimbabwe reported a 45% increase in malaria infections compared with 2019 (ref.23). Many African countries lack the capacity to implement widespread testing, including the identification of asymptomatic and mild infections that are major drivers of the pandemic24. Although it is difficult to determine the number of tests conducted in many Africa countries, the publicly available data clearly highlight the limited testing capacity on the continent. South Africa is currently conducting the largest number of tests per 10,000 individuals (0.5/10,000 individuals), whereas many other countries, including Ethiopia, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Tunisia, Senegal and Rwanda, perform fewer than 0.1 tests/10,000 individuals. This is markedly less than in the USA (1.54/10,000 individuals), the UK (0.9/10,000 individuals), Italy (0.91/10,000 individuals) or Germany (0.55/10,000 individuals)25. Similar infrastructure limitations constrain the development of prophylactic vaccines and therapeutic interventions, which results in a concerning reliance on developed countries. Another important consideration in the response to the pandemic in Africa will be to limit the impact of the virus on vulnerable economies where prolonged lockdowns may not be feasible.

The first case of COVID-19 in Africa was reported in Egypt on 14 February 2020; subsequently, infections have been documented in 44 other African countries, with South Africa reporting the highest number of cases6. Interestingly, in spite of the obvious challenges in combatting the growing pandemic, African countries have observed a delay in the exponential growth trajectory that has been described by countries in the developed world26. This may be partly attributable to lower testing capacity in the region and the impact of implementing lockdowns in the early phase of the pandemic. The warmer climate has also been proposed to influence the spread of COVID-19, which could explain the delayed pandemic in Africa compared with the rest of the world, although this is largely speculative (Box 1). The transition into winter in southern Africa has been accompanied by an increase in SARS-CoV-2 infections, further complicated by seasonal influenza and limited influenza vaccine availability. In this Review, we discuss the global efforts to develop diagnostic tests and therapeutic options to treat COVID-19, as well as the vaccine platforms for immunization, with a focus on the opportunities and challenges for Africa.

Box 1 Potential impact of climate on SARS-CoV-2 dissemination.

The comparatively low incidence of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) in Africa has raised the possibility that climate could influence the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). There is some circumstantial evidence describing a possible association between higher temperatures and lower severity of COVID-19 to support this hypothesis; however, outbreaks in Malaysia, Hong Kong, Australia and South Africa seem to be inconsistent with this theory as large numbers of infections have been reported despite higher temperatures130–132. The influence of climate could potentially account for the severity of the pandemic in central China and northern Italy, where winter may have been particularly conducive to the spread of the virus131. These cold conditions are reminiscent of the environment in which SARS-CoV first emerged in China in November 2002 (ref.133). Although these observations are compelling, it is noteworthy that many of these studies have yet to undergo formal peer review, and the accuracy of species distribution models is constrained by variability in global testing capacity134. For example, infections in many African countries are expected to be an underestimate that reflects the lower number of tests conducted. It is also acknowledged that numerous other variables could influence the spread of the virus and may confound interpretations of the impact of climate. These variables may include variation in population density and age distribution, timely lockdown measures, adherence to social distancing protocols or even childhood vaccination with Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette–Guérin as examples135. The impact of differing behaviour, with increased social mixing, in the winter months also cannot be discounted136. As with many respiratory pathogens, both Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) and SARS-CoV exhibit decreased viability in the laboratory following exposure to increasing temperature and humidity137,138. Similar observations have also been reported for influenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus, for which the incidence of infection is highest under cold and dry conditions, which results in seasonal cycles of infection139,140. A similar seasonality has also been observed for other endemic human coronaviruses, which led to the speculation that SARS-CoV-2 may also conform to a seasonal cycle of infection136. However, although all four endemic human coronaviruses (HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1) exhibit a marked winter seasonality141, the pathogenic human coronaviruses (MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV) do not conform to such a defined infection cycle. For example, MERS-CoV generally occurs mostly during summer months in the Middle East despite temperatures often exceeding 50 °C142. By contrast, the highest incidence of SARS-CoV was reported during the winter months, although the outbreak continued to spread throughout spring in Hong Kong143,144. Therefore, more research is needed to define the impact of climate on the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

COVID-19 diagnostics in Africa

The diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 poses a major challenge owing to the prevalence of asymptomatic infections, pre-symptomatic infections with high viral loads in the upper airways (probably at peak infectivity) and the range of non-specific symptoms that manifest in individuals who are symptomatic5,24. Widespread testing is therefore critical to identify infected individuals who are asymptomatic, pre-symptomatic and symptomatic, and to enable contact tracing and isolation27. Whereas this has been highly successful in countries such as Germany and South Korea, it is not generally possible in most African countries where the infrastructure is weak. Indeed, in countries such as South Africa, where widespread community testing was attempted, this has resulted in a very large backlog of tests and delays of weeks for returning test results, which are then rendered meaningless for quarantining of cases and containment28. In many African countries, testing is only available for severe cases of presumed COVID-19, and self-isolation is recommended for less severe cases. Therefore, reported cases and true prevalence do not equate. Accordingly, the capacity provided by academic laboratories and pharmaceutical companies is being leveraged to increase testing capacity further, as has been necessary even in developed countries29.

Diagnosis of acute infection is by PCR with reverse transcription of respiratory tract specimens, which is generally performed in central laboratories with specialized equipment30. Scale-up of testing is a major challenge for countries in Africa, owing to laboratory infrastructure, costs and availability of test reagents that are largely imported and currently stretched global supply chains. A recently launched, continent-wide initiative, the Africa Medical Supplies Platform, seeks to leverage collective purchasing for procurement of testing supplies, personal protective equipment, medical equipment and even, potentially, future vaccines31. In addition, repurposing of rapid, automated molecular diagnostics platforms such as GeneXpert® (Cepheid), which is widely used for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in South Africa, has the potential to decentralize and accelerate testing in certain countries, including using mobile testing centres, although test kits are also in limited supply. However, this has to be understood in the light of the potential for unintended consequences on the management of tuberculosis, with fewer diagnostic platforms being available as a result of increased SARS-CoV-2 testing. Testing for tuberculosis in South Africa has reportedly decreased by 50% during the lockdown period and, concurrently, the weekly average of microbiologically confirmed tuberculosis cases decreased by 33% (ref.32).

Recently, a rapid method of heating samples prior to quantitative PCR with reverse transcription has shown promise to improve the turnaround time for testing and bypasses the need to order RNA extraction reagents or kits33. Furthermore, a rapid CRISPR–Cas12-based test has also been developed to diagnose infection from respiratory sample-derived RNA34. The test yields a result within 1 h and is less reliant on sophisticated laboratory infrastructure and test reagents that are in limited supply. Implementing this test in Africa could be a useful way of expanding the current testing capacity and could offer a faster turnaround time for high-priority cases.

Serology-based testing approaches have been proposed, but the delay between infection and the development of detectable antibodies (within 19 days) renders this approach impractical for the diagnosis of acute infection35,36. Nonetheless, these tests are critical for seroprevalence studies and to identify appropriate donors for convalescent sera, and potentially for the isolation of monoclonal antibodies that can be developed as therapeutics. Serology studies are also crucial for understanding the longevity of the antibody response after infection, with the key caveat that it is not known whether humoral responses are a correlate of immunity against the virus. In addition, preliminary data suggest that not all individuals who are infected may seroconvert37, and early evidence is emerging that antibody levels may wane rapidly during the convalescent phase38. Several serological assays have already been developed, and binding antibodies against the spike and nucleocapsid proteins are both indicative of past SARS-CoV-2 infection39,40. Many of these assays are also commercially available, but their specificity and sensitivities seem to be variable41. A major outstanding question is which antigen, or region of the antigen, is most appropriate for serology testing. Most assays have favoured the spike glycoprotein for the detection of an immune response against the virus, although it is worth noting that the nucleocapsid is the most abundant viral antigen42.

Recent work has suggested that the receptor-binding domain alone may be sufficient to detect antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2, and given that it is not conserved between coronaviruses, its use may limit cross-reactivity arising from other coronavirus infections43. Nonetheless, a nucleocapsid-based ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) may be the easiest to implement in an African context as the antigen could easily be produced locally at low cost. Nucleocapsid could be produced in Escherichia coli, Pichia pastoris or even in plants, as has been reported for the nucleocapsid proteins of three bunyaviruses, two of which were used successfully in validated assays44–46. Moreover, the Biovac Institute in South Africa has the capacity for bacterial fermentation and the required infrastructure for downstream processing, and a new plant-based production facility (Cape Bio Pharms) is currently generating S1 protein derivatives as reagents. Although the spike glycoprotein is heavily glycosylated and needs to be expressed in a more complex expression host to ensure appropriate post-translational modifications, both mammalian cells and plants would be suitable to produce both spike and nucleocapsid, and novel approaches to enhance recombinant glycoprotein production in plants have also been developed in South Africa47.

Therapeutic options to treat COVID-19

Given the optimistic development timeline of 12–18 months before any vaccines could be available for widespread use, it is clear that these efforts will not affect the first wave of the pandemic48. More importantly, the lack of manufacturing capacity in Africa and the global demand for immunization against the virus will further delay the availability of vaccines in the region. Repurposing existing drugs presents a feasible short-term strategy to manage the pandemic, especially given that some of the drug candidates are already available and have an established safety profile in humans49. These drugs would face lower regulatory barriers for approval and, in addition to being used for treating active infections, may have potential to be used as prophylactics for individuals at high risk, such as health-care workers or those who have been in contact with documented cases of infection.

Currently, two treatments have been shown to have an effect on the outcome of COVID-19. The broad-spectrum antiviral drug remdesivir has been shown to shorten the recovery time in adults admitted to hospital with severe COVID-19 in a publication of preliminary results from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in the USA50. However, remdesivir did not reduce mortality. By contrast, initial data from the recent RECOVERY trial in the UK suggest that daily oral or intravenous doses of dexamethasone (10 mg for 10 days) reduced mortality by one-fifth in hospitalized patients with proven COVID-19 requiring oxygen therapy, and that mortality was reduced by one-third in patients who needed mechanical ventilation51. It had no effect on patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who were not requiring oxygen. The reductions in mortality were seen in patients whose symptoms started >7 days before receipt of the drug. The fact that a commonly used corticosteroid could reduce mortality in this trial is promising, as numerous other corticosteroids such as prednisolone and hydrocortisone (which were options in the RECOVERY trial in pregnant women) are equally available, and some of them are manufactured in Africa, which means that access may be less of an issue than for other more novel medicines.

More commonly available medicines have been, and some continue to be, used in investigational treatments for COVID-19. The commonly available antimalarials chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine were among the first to be investigated. Initial studies were small and underpowered, and some combined hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin52 and some proved highly controversial in relation to their conduct, leading to retraction53. One of the arms of the RECOVERY trial included hydroxychloroquine, and on 4 June 2020 the independent data monitoring committee review of the data concluded that there was no beneficial effect of hydroxychloroquine in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 (ref.54). Shortly after, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that recruitment for the hydroxychloroquine arm of the SOLIDARITY trial was being stopped55,56.

All experimental treatments should either be introduced into properly conducted clinical trials or, if a country decides to use such a medicine outside a trial, then it should be controlled according to the WHO’s Monitored Emergency Use of Unregistered Interventions (MEURI) framework, whereby it can be ethically appropriate to offer individuals investigational interventions on an emergency basis, in the context of an outbreak characterized by high mortality57. Large-scale adaptive studies such as the RECOVERY and SOLIDARITY trials continue, and such trials will reduce the time taken for randomized clinical trials58. Several African countries, including South Africa, Burkina Faso and Senegal, are in the process of joining the SOLIDARITY study.

Similarly, small studies are ongoing in several countries, looking at the utility of convalescent plasma from patients who recently recovered from COVID-19 as potential prophylaxis or treatment59. The need for randomized control trials using this treatment modality has been stressed60. Unlike other investigational medicines, convalescent plasma can be readily produced, even in low and middle-income countries, through the national blood transfusion service, making it an attractive option for study. However, scaling production for use is the rate-limiting step for this intervention. Preliminary studies identified monoclonal antibodies with the ability to neutralize SARS-CoV-2, which may also be important candidates for both treatment and prophylaxis, although similar issues with manufacture are a challenge61,62.

There is increasing recognition that pathophysiology of severe COVID-19 includes an appreciable component of hyperactivation of inflammatory responses, manifesting as a cytokine storm and secondary haemophagocytic lymphocytic histiocytosis. In addition to the findings relating to dexamethasone detailed above, various immune-modulating drugs have been proposed as treatment options for COVID-19. The IL-6 inhibitors tocilizumab (Actemra; Roche) and sarilumab (Kevzara; Sanofi and Regeneron), which are used to treat arthritis, are already being used in patients with COVID-19 (NCT04327388)63. Their mechanism of action involves the prevention and the inhibition of the overactive inflammatory responses in the lungs. Both drugs have entered phase III clinical trials for SARS-CoV-2. A late-stage clinical trial with another IL-6 inhibitor, siltuximab (Sylvant; EUSA), started in Italy in mid-March (NCT04322188). Anti-inflammatory drugs used in combination with an antiviral drug such as remdesivir may increase the potential of the drug to improve disease outcome64. Genentech has recently initiated a phase III trial (REMDECTA) to study the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab and remdesivir in patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 pneumonia (NCT04409262). Additionally, the COVACTA study (NCT04320615) will evaluate tocilizumab and standard of care versus standard of care alone in a similar cohort65.

Patients who have chronic medical conditions may be at higher risk for serious illness from COVID-19, including those with pulmonary fibrosis66. The antifibrotic drug pirfenidone (Genentech) has already entered a study to evaluate its efficacy and safety (NCT04282902). Recombinant angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2; APN01) that lacks the transmembrane region of the protein was developed by Apeiron Biologics for the treatment of acute lung injury and pulmonary artery hypertension. The soluble ACE2 has the potential to reduce lung injury by activating the anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory angiotensin (1–7)–Mas receptor axis of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, and by acting as a decoy and preventing infection by binding to the SARS-CoV-2 virus and inactivating it. APN01 is being tested in a phase I trial in China, and approval has been secured to carry out phase II trials in Austria, Germany and Denmark (NCT04335136).

Currently, there are no targeted therapies for COVID-19. However, numerous drug discovery programmes are in progress, and a recent study reported a structure-based drug design strategy, as well as virtual and high-throughput screening to identify lead compounds that bind to the main protease of the virus (Mpro; also known as 3CLpro)67. The active site of the protease is highly conserved among coronaviruses, making a strong case for pursuing an Mpro-targeting drug. The organoselenium drug ebselen, which is an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant, showed high affinity for Mpro and showed promising antiviral activity (concentration that gives half-maximal response EC50 = 4.67 μM). Thus, the presented approach may greatly accelerate the discovery of drug leads with potential in the clinic.

The Drug Discovery and Development Centre (H3D) based at the University of Cape Town is the only fully integrated drug discovery centre in Africa that has taken a drug into a phase II clinical trial. The centre has very strong collaborations with the pharmaceutical industry and MMV, a leading product development partnership, as well as the infrastructure and expertise to find potential therapies against COVID-19. H3D has assembled chemical libraries for its malaria and tuberculosis projects that could be screened to identify possible drug leads against SARS-CoV-2; however, this will require additional resources and funding because the centre is contractually focused on antimalarial and anti-tuberculosis drug development.

Vaccine platforms and implementation

The infrastructure for large-scale, high-volume vaccine manufacturing is largely absent in Africa, and the rapidly escalating COVID-19 pandemic highlights the urgent need for capital investment in the region to lessen reliance on developed countries. The few facilities that are available are specialized, and are not well-suited to produce vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1). It is also anticipated that it would take a minimum of 18 months to build a suitable manufacturing plant under ideal conditions, and therefore to contribute to the global COVID-19 vaccine initiative, African developers will need to outsource large-scale manufacturing in the short term. The African Vaccine Manufacturing Initiative, which aims to develop local manufacturing capacity in Africa, has established a working group and is actively engaged with key stakeholders to meet the local need for a vaccine. Innovative Biotech (Nigeria) has already partnered with Medigen (USA) and Merck (Germany) to apply their insect cell production platform to producing virus-like particles with the intention of initiating a clinical trial in Nigeria. Similarly, the Ethiopian Public health Institute (EPHI) is planning to partner with TechInvention (India) to produce the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in a yeast-based fermentation system, although limited details are available (personal communication, S. Agwale, CEO of Innovative Biotech). Last, Biovac (South Africa) has modern facilities at a modest scale and has initiated a feasibility study for a large-scale facility with an annual minimum production capacity of 100 million vaccine doses for COVID-19 and future pandemic vaccines, as well as vaccines for routine immunization use (personal communication, P. Tippoo, Head of Science and Innovation, Biovac).

Table 1.

Infrastructure for human vaccine manufacturing in Africa

| Organization | Location | Technology platform | Vaccines | Production scale (doses) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institut Pasteur de Tunis | Tunisia | Bacterial fermentation | BCG | <1 million |

| Institut Pasteur de Dakar | Senegal | Egg-based | Yellow fever (WHO prequalified) | Currently 5 million doses (expansion to 30 million underway) |

| Biovaccines | Nigeria | Not yet operational | Undisclosed | Unknown |

| Innovative Biotech | Nigeria | Insect cell virus-like particles | Preclinical: HIV-1 and Ebola virus | Unknown |

| Vacsera | Egypt | Bacterial fermentation, end to end | DTP, cholera | Undisclosed |

| The Biovac Institute | South Africa | Fill–finish | Variable | ~30 million |

BCG, Bacille Calmette–Guérin; DTP, diphtheria, tetanus toxoid and pertussis; WHO, World Health Organization.

Given the global demand for a COVID-19 vaccine, it is likely that even when a suitable candidate is approved for human use, there will be a considerable delay before it is available in Africa. This is not unprecedented — during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, a global shortage of influenza vaccines resulted in limited supplies being provided for countries in the region, and, in fact, the vaccines only became generally available after 2010 (ref.68). This unfortunate, but entirely plausible, scenario may necessitate prioritizing high-risk groups, such as health-care workers and older individuals, to receive the first SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to reach Africa.

More than 100 vaccine candidates are currently in preclinical development around the world, and 15 vaccines are already being tested in clinical trials69,70 (Table 2). These vaccines are mostly focused on eliciting immunity against the spike glycoprotein, although other viral antigens may also have a role in vaccine-mediated protection (Box 2). The speed of clinical deployment of these vaccines is unprecedented, but there are concerns regarding the longevity of immune responses and the potential for vaccine-mediated enhancement of infection (Box 3). Although the rapid progress to clinical testing is encouraging, it is still too early to determine whether they will confer immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection or whether they will ameliorate the disease course following infection. The only peer-reviewed report of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in clinical trial to date is for CanSino Biologics’ Ad5-nCoV vaccine, which recently completed phase I testing. Encouragingly, the vaccine elicited both binding antibodies and antigen-specific T cells, although, disappointingly, only 50% of volunteers developed neutralizing antibodies in the low (5 × 1010 viral particles) and medium (1 × 1011 viral particles) dose regimens. However, 75% of the high-dose group (1.5 × 1011 viral particles) developed neutralizing antibodies. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the high-dose group also reported a higher incidence of adverse effects following vaccination and only the low and intermediate doses will be pursued in phase II trials71.

Table 2.

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates currently in clinical testing

| Vaccine technology (vaccine name) | Description | Developer | Cohort age | Location | Phase and trial number | Number of participants | Start date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 | Evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity of the vaccine in a healthy population | Wuhan Institute of Biological Product | ≥6 years | China |

Phase I and II ChiCTR2000031809 |

1,112 | 25 April 2020 |

| Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 (BBIBP-CorV) | Evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity of the vaccine in a healthy population | Beijing Institute of Biotechnology | ≥3 years | China |

Phase I and II ChiCTR2000032459 |

2,128 | 25 April 2020 |

| Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 (PiCoVacc) with an alum adjuvant | Clinical trial to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of the vaccine in healthy adults | Sinovac | 18–59 years | China |

Phase I and II |

744 | 16 April 2020 |

| Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 | Trial in healthy individuals | Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences | 18–59 years | China |

Phase Ia and IIa |

942 | 15 May 2020 |

| Stable, pre-fusion spike nanoparticle with and without Matrix-MTM adjuvant | To evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of the vaccine with and without the adjuvant | Novavax | 18–59 years | Australia |

Phase I and II |

131 | 25 May 2020 |

| COVID-19 spike protein trimer subunit vaccine (SCB-2019) with different adjuvants | To evaluate the safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of the vaccine candidate at different dose levels with and without the adjuvant | Clover Biopharmaceuticals | Adults and older individuals | Australia |

Phase I |

90 (adults) 60 (older individuals) |

22 June 2020 |

| Non-replicating chimpanzee adenovirus AZD1222, expressing spike protein (ChAdOx1) | To determine the efficacy, safety and immunogenicity in healthy adult volunteers | University of Oxford and AstraZeneca | 18–55 years | UK |

Phase I and phase II |

1,090 | 23 April 2020 |

| Variable | UK | Phase II and III | 10,000 | 29 May 2020 | |||

| 18–65 years | South Africa |

Phase I/II |

2,000 | 24 June 2020 | |||

| 18–55 years | Brazil |

Phase III ISRCTN89951424 |

5,000 | 20 June 2020 | |||

| Ad5-nCoV encoding full-length spike protein | To evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of the vaccine in healthy adults | CanSino Biologics | ≥18 years | China |

Phase II |

508 | 12 April 2020 |

| 18-60 years | China |

Phase I |

108 | 16 March 2020 | |||

| mRNA (NRM) (mRNA-1273) expressing spike protein encapsulated with LNP | Open-label, dose-confirmation study to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of the vaccine in healthy adults | Moderna and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases | 18–99 years | USA |

Phase Ia |

120 | 16 March 2020 |

| Open-label, dose-confirmation study to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of the vaccine | Moderna and National Institute of allergy and infectious diseases | ≥18 years | USA |

Phase IIa |

600 | 25 May 2020 | |

| mRNA (NRM) and SAM constructs expressing spike protein in LNP (BNT162) | Dose-escalation trial investigating the safety and immunogenicity of four prophylactic SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines using different dosing regimens in healthy adults | BioNTech and Pfizer | 18–55 years | Germany and USA |

Phase I and II |

200 | 23 April 2020 |

| mRNA SAM expressing spike protein in LNP (COVAC1) | A first-in-human clinical trial to assess the safety and immunogenicity of a self-amplifying ribonucleic acid (SAM) vaccine encoding the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 | Imperial College London | 18–45 years | UK |

Phase I ISRCTN17072692 |

300 | 15 June 2020 |

| 18–75 years | UK | Phase II | 200 | 15 June 20 20 | |||

| mRNA encoding the spike protein encapsulated in LNP (CVnCoV) | To evaluate the safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of the vaccine in healthy adults | CureVac | 18–60 years | Germany and Belgium |

Phase I |

168 | 18 June 2020 |

|

DNA expressing spike protein (INO-4800) |

To evaluate the safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of the prophylactic vaccine against SARS-CoV-2, administered intradermally followed by electroporation in healthy volunteers | Inovio Pharmaceuticals | ≥18 years | USA |

Phase I |

120 | 3 April 2020 |

| DNA expressing spike protein (GX-19) | Safety and immunogenicity study of the vaccine in healthy adults | Genexine, Inc. | 18–50 years | South Korea |

Phase I and II |

190 | 17 June 2020 |

|

DCs modified with lentivirus vectors expressing SARS-CoV-2 minigene SMENP and immunomodulatory genes with antigen-specific CTLs (LV-SMENP) |

Multicentre trial of the vaccine | Shenzhen Geno-Medical Institute | 6 months−80 years | China |

Phase I and II |

100 | 24 March 2020 |

| aAPCs modified with lentivirus vectors expressing minigenes from selected SARS-CoV-2 proteins | Safety and immunity evaluation of the vaccine | Shenzhen Geno-Medical Institute | 6 months−80 years | China |

Phase I |

100 | 15 February 2020 |

aAPC, artificial antigen-presenting cell; COVID-19, coronavirus disease-2019; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; DC, dendritic cell; LNP, lipid nanoparticles, NRM, non-replicating mRNA; SAM, self-amplifying mRNA; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Despite the absence of suitable facilities for current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP)-compliant vaccine or therapeutics manufacturing in most of Africa, considerable expertise in preclinical vaccine development is also available in academic institutes, and vaccines could be manufactured on contract for clinical trials as was the case for the South African AIDS Vaccine Initiative72. Accordingly, groups at the University of Cape Town (South Africa), the National Research Centre (Egypt) and the Kenya Aids Vaccine Initiative (KAVI) have all confirmed that early-stage research on SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development is underway — although further details have not been disclosed73. Important considerations for these vaccines will be the cost, their safety in individuals who are immunocompromised and the availability of manufacturing partners who can produce the vaccines at the required scale. With these restrictions in mind, non-replicating viral vectors, DNA vaccines and cell and plant-based subunit immunogens are arguably the most suitable prospects. Alternatively, if suitable capital investment is made available, a cGMP-compliant facility could be established with the intention of manufacturing one of the vaccines that is already in clinical development.

Genetic immunization with plasmid DNA is perhaps the easiest vaccine modality to develop for clinical trials as the manufacturing process is well established, the incumbent costs are low compared with other platforms and multiple clinical trials have shown their safety. Technological advances have also substantially reduced the time from identifying the viral sequence to initiating immunizations in humans74. Accordingly, DNA vaccines have been advanced into the clinic in response to several emerging pathogens, including MERS-CoV, and Inovio Pharmaceuticals (USA) have already completed recruiting participants to initiate a phase I trial with a candidate DNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 (NCT04336410)75. Recent preclinical data demonstrated that the vaccine elicited neutralizing antibodies in both mice and guinea pigs, and an unrelated study reported that immunization with a DNA vaccine protected against viral challenge in macaques76,77. Genetic immunization is well-suited to clinical development for Africa, and candidate vaccines could be manufactured to cGMP standards using one of the contract manufacturers offering this service. However, there are no licensed human vaccines based on this platform, and the current delivery methods are not suitable for large-scale immunization.

Host-restricted viral vectors are another promising vector platform for immunization in Africa78. Replication-deficient chimpanzee adenovirus-based vaccines have shown promise for several emerging viruses, and given their simian origin, they circumvent concerns for vector-specific immunity as was observed when using human adenoviral vectors for immunization79. A single dose of a MERS-CoV-2 vaccine using this platform was reported to elicit protective immunity in non-human primates80. More recently, a single immunization with ChAdOx1 encoding the SARS-CoV-2 spike protected against pneumonia and lowered viral loads in both bronchoalveolar lavage and respiratory tract samples in macaques following challenge81. This effect was observed in the absence of high titres of neutralizing antibodies and the impact of the vaccine was to ameliorate severe disease rather than to prevent infection. Although it is disappointing that the vaccine did not confer sterilizing immunity in monkeys, it is noteworthy that the monkeys only received a single immunization and that the inoculum used for challenge was high. It should be noted that the high-challenge inoculum was conceived to determine whether immunization resulted in vaccine-mediated enhancement of infection, and that there was no evidence to suggest that this would be a concern81. This is the vaccine being pursued by the University of Oxford in collaboration with AstraZeneca that is now in phase II testing. A clinical trial for this vaccine has recently been initiated in Johannesburg (South Africa), and this is the first vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 to be tested in Africa. The manufacturing cost of ChAdOx1 would be far less than for a subunit vaccine and, moreover, no adjuvant is needed for immunization.

Poxvirus-based vectors are similarly attractive: they elicit strong humoral and cellular immune responses, can be manufactured at low cost and are stable in the absence of a sustained cold chain78,82. In addition, they can accommodate larger genetic insertions, which could be exploited to encode multiple SARS-CoV-2 genes (such as the spike, nucleocapsid, membrane and envelope antigens) and could potentially produce virus-like particles. Suitable examples of candidate poxvirus vectors include the attenuated orthopoxviruses modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA)83 and NYVAC84, the avipoxviruses canarypox virus (ALVAC)85 and fowlpox virus (FWPV)86, and the capripoxvirus lumpy skin disease virus (LSDV)87. MVA is the most widely explored of these vectors. Having been attenuated by more than 570 passages in chick embryo fibroblast cells, MVA has a well established safety record, including in individuals who are immunocompromised, and has recently been approved as a vaccine against smallpox88,89. NYVAC was engineered by the purposeful deletion of 18 genes involved in host range and pathogenicity; it causes no disseminated disease in immunodeficient mice, like MVA, and is unable to replicate in humans90. Several MVA-vectored vaccines of particular relevance to Africa have shown promise in clinical trials, usually in prime-boost regimens together with other vectors such as DNA or adenovirus. These include vaccines against HIV-1 (ref.91), Mycobacterium tuberculosis92 and Ebola virus93. LSD, a notifiable disease of cattle worldwide, is prevalent in most African countries, and the live-attenuated Neethling vaccine strain is widely used to control the disease on the continent94. LSDV is being developed both as a multivalent cattle vaccine vector87,95 and as a host-restricted HIV-1 vaccine vector96. It has been shown to have no adverse effects in immunodeficient mice, and although this vector could not be used in countries free of LSDV, it has potential as a human vaccine in sub-Saharan Africa96. Together with MVA and NYVAC, the avipoxvirus vectors ALVAC (attenuated canarypox virus) and FWPV are probably more realistic targets for rapid clinical development, as they have also undergone testing in humans, and ALVAC is already licensed for several veterinary applications97. At present, there are no cGMP-accredited manufacturers of adenovirus or poxvirus-based vaccines for humans in Africa. Sanofi Pasteur (France) supplies ALVAC-based vaccines, Virax (Australia) manufactures FWPV and MVA-based vaccines are manufactured by multiple companies including Geovax Labs, Inc. (USA), ProBioGen (Germany) and Bavarian Nordic (Denmark). Similarly, chimpanzee adenovirus-based vaccines are manufactured at the Jenner Institute (UK) or in collaboration with established manufacturing partners. Capripoxviruses are manufactured as veterinary vaccines, although the only cGMP-approved manufacturer is MCI Santé Animale (Morocco).

Plant-based vaccine protein production is an emerging technology that is well-suited to resource-limited areas given the capacity of the system for rapidly scalable production, the low manufacturing costs and the less sophisticated infrastructure requirements than mammalian expression systems98. The platform is well established to produce diverse classes of recombinant proteins, and recent advances in expression technologies and molecular engineering have also enabled improvements in glycoprotein production in plants47,99. Encouragingly, a preliminary pilot study suggests that these approaches can be applied to produce the SARS-CoV-2 spike in Nicotiana benthamiana plants, warranting further testing of the recombinant antigen in preclinical vaccine immunogenicity models100. Three leading plant biotechnology companies, Medicago Inc. (Canada), Ibio Inc. (USA) and Kentucky BioProcessing Inc. (USA), have already announced the successful production of candidate virus-like particle vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Although plant-based manufacturing of recombinant protein antigens may be the most suitable solution for Africa, it may also pose a challenge for manufacturing. The major advantages of plant-based vaccine production for SARS-CoV-2 in Africa are the lower costs and the potential for rapid production scale-up to accommodate the large demand for a vaccine. This is best demonstrated in the context of influenza vaccine development, as a fully formulated virus-like particle vaccine was produced within 3 weeks following release of the viral sequence101. This rapid development timeline supported the production of 10 million doses of the vaccine within 1 month102. However, despite the costs to establish a GMP-compliant plant-based manufacturing facility being considerably less than those for the equivalent mammalian platform (for example, US$80–100 million versus US$250–350 million, respectively), they are not insignificant, and the capital investment required has been prohibitive for Africa98. Furthermore, there are few suitable contract manufacturing organizations worldwide, and these are already invested in their own SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development programmes.

Several recent preliminary data have suggested a possible correlation between Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination and lower prevalence and mortality due to COVID-19 (refs103–106). The BCG vaccine is one of the most widely used vaccines worldwide and has been used to vaccinate against tuberculosis for nearly 100 years. The vaccine comprises a live, attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, which provides protection against disseminated forms of tuberculosis in infants but gives variable protection against pulmonary tuberculosis in adults107,108. Non-specific cross-protection against other pathogens, including those causing respiratory tract infections, has also been documented109. This effect may be attributable to altered expression of host cytokines and pattern-recognition receptors, as well as the reprogramming of different cellular metabolic pathways that, in turn, increases the innate immune response to other pathogens109,110. However, potential correlation between BCG vaccination and COVID-19 severity should be interpreted with caution. First, it is unlikely that BCG vaccination at birth will still provide non-specific cross-protection against viral pathogens in older individuals. Second, the correlation could be influenced by numerous unknown confounding factors, including variation in testing between countries, which leads to differences in the recorded case numbers; differences in average population age, ethnic and genetic backgrounds; the stage of the pandemic in each country; and different approaches to mitigating the spread of the disease in different countries. Numerous clinical trials are presently underway to determine whether BCG vaccination reduces the incidence and severity of COVID-19 in health-care workers and older individuals (Supplementary Table). A trial has also started in Egypt (NCT04347876), where disease severity and mortality in patients with COVID-19 will be compared between those with positive and negative tuberculin tests. In Brazil, the BCG vaccine will be given to patients with COVID-19 as a therapeutic vaccine to evaluate the impact on the rate of elimination of SARS-CoV-2, the clinical evolution of COVID-19 and the seroconversion rate and titres of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. As the BCG vaccine has been administered to most neonates in South Africa and France until recently, these trials will also investigate the effect of revaccination with the BCG vaccine. In addition, a new modified version of BCG, namely VPM1002, which expresses listeriolysin instead of urease C, will be tested in health-care workers and older individuals in Germany111. Securing a reliable supply of BCG vaccine doses could be a challenge in Africa if re-immunization shows promise, as there is limited manufacturing capacity for the vaccine on the continent. Historically, shortages of the vaccines were documented in 41% of countries on the continent between 2005 and 2015 (ref.112). This was largely due to lack of supply, but the limited availability of financing, procurement shortcomings and ineffective vaccine management also contributed to the shortage. The low price for a BCG vaccine and limited investment has also reduced the incentive for manufacturers to redesign and improve production processes in the region. From 1988 to 2001, the 172-Tokyo BCG strain was produced at the State Vaccine Institute in Cape Town, South Africa; however, this was discontinued as the cost of importing the vaccine was lower than that of local manufacture.

Box 2 SARS-CoV-2 virus structure and targets for vaccine development.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) comprises pleomorphic virions, ranging from 60 to 140 nm in diameter, with prominent glycoprotein spike proteins projecting from the virus surface4. The virion also contains the membrane, envelope and nucleocapsid proteins, which encapsulate the viral genome and accessory proteins (see the figure, left). The spike protein is a glycosylated type 1 fusion protein that mediates infection by binding the host membrane-anchored angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)145. The glycoprotein is organized into extracellular (S1) and membrane-spanning (S2) subunits, which mediate receptor binding and membrane fusion, respectively (not shown). Binding of the spike protein to ACE2 results in a conformational change that enables the dissociation of the S1 subunit and the insertion of the fusion peptide into the host membrane146.

The spike glycoprotein is the primary target of vaccine development, based on the premise that neutralizing antibodies against spike will prevent viral entry into susceptible cells (see the figure, right). This is supported by preclinical immunogenicity studies, for the related Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and SARS-CoV, for which immunization with spike-based vaccines elicited protective antibody responses147,148. More recently, neutralizing antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike have been reported in natural infection; these are readily elicited and frequently target the receptor-binding domain in S1 (ref.35). The potential role of cell-mediated immunity in coronavirus vaccines generally has not been as well explored. It is reasonable to expect that cellular immune responses would contribute to viral clearance and ameliorate the severity of the disease, as well as support the development of antibody responses. Accordingly, robust and durable cellular responses have been observed against the spike, membrane, envelope and nucleocapsid proteins in patients who recovered from SARS coronavirus infection149–151. Ultimately, both cell-mediated and humoral responses are desirable in a vaccine, especially given the observation that cellular responses are longer lived than antibodies following infection with SARS coronaviruses152,153. MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

Box 3 Immunological challenges for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development.

Two concerns have been raised that could undermine the vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in clinical testing: the longevity of immunity, and the potential for adverse effects following SARS-CoV-2 infection in immunized volunteers. The durability of antibody responses has implications for vaccine development, as immunization may need to induce stronger immunity than natural infection. This concern is partly due to observations of waning neutralizing antibody titres after SARS coronavirus infection, and a lack of knowledge regarding the potential for SARS-CoV-2 re-infection154–156. Encouragingly, preliminary data suggest that rhesus macaques may be resistant to challenge with SARS-CoV-2 after clearing the primary infection157. The duration of this protection remains unclear, as do the correlates of immunity. Low neutralizing antibody titres were recently reported in 30% of patients who recovered from mild infection with SARS-CoV-2, which suggests that cellular responses may have an important role in viral clearance. However, it is plausible that neutralizing antibody titres correlate with disease severity and merely reflect the extent of antigenic stimulation61.

Another concern is vaccine-induced enhancement of infection. This can manifest as either antibody-dependent enhancement or cell-mediated inflammatory responses that result in pathology following exposure to the virus. Accordingly, type 2 T helper cell-mediated lung pathology with eosinophilic infiltrates has been observed in vaccinated and challenged animals for both Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and SARS-CoV158–160. The potential impact of antibody-dependent enhancement in the context of coronavirus vaccines has not been as well defined, although the phenomenon has been described for a monoclonal antibody targeting the MERS coronavirus spike glycoprotein161. Preliminary data suggest that antibody-dependent enhancement may account for the severity of COVID-19 in some cases, where previous exposure to other coronaviruses may have elicited responses that enhanced infection, although this remains to be determined162.

The potential impact of co-infections

Africa shoulders a considerable burden of co-infections. Although HIV-1 and tuberculosis may be the most important infections when considering potentially enhanced COVID-19 disease severity, the high incidence of malaria and helminth infections as well as multiple ongoing outbreaks of Ebola virus disease, Lassa fever, cholera, measles, yellow fever, hepatitis E and chikungunya virus113 all represent infections with unknown interactions with SARS-CoV-2.

The high prevalence of HIV-1 and tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa presents an important but largely unknown challenge for the continent with regard to COVID-19. The urgent question that needs answering is whether individuals with HIV-1, or those with past or current tuberculosis, have a higher risk of infection or greater morbidity and mortality from COVID-19. Of the 37.9 million people living with HIV-1 globally, 25.6 million live in sub-Saharan Africa, and it is estimated that 64% are accessing antiretroviral therapy and 54% are virally suppressed114. Although individuals who are immunocompetent with well-controlled HIV-1 infections may be at no greater risk for COVID-19, there remains a considerable number of individuals with low CD4 counts and uncontrolled HIV-1 viraemia who may be at risk of severe disease. To date, there have been two published reports of concurrent COVID-19 and HIV-1 infection115,116. Although the cohort was an extremely limited group of patients predominantly established on antiretroviral therapy, the pattern of clinical disease did not differ from that observed in the general population, but more research is needed to confirm this result.

The severity of other respiratory infections concomitant with HIV-1 may provide some clues: although the immunopathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 is probably distinct in several aspects from influenza viruses, there are some shared clinical features. HIV-1 infection is associated with a greater susceptibility to influenza virus infection, increased severity of influenza-related disease and poorer prognosis in patients who are severely immunocompromised117. A large South African study observed an eightfold higher incidence of influenza virus infection and a fourfold greater risk of death in the case of HIV-1 co-infection118. Paradoxically, there is also evidence that lower inflammatory responses in individuals who are immunocompetent and infected with HIV-1 may lead to milder influenza-related disease117. In addition to altering the clinical course of disease, HIV-1 infections may result in poorer antibody responses that may lead to prolonged viral shedding, thereby influencing disease transmission119. Tuberculosis, a disease that causes chronic lung damage, may also present a challenge in the COVID-19 era. There were approximately 2.4 million new cases of tuberculosis in Africa in 2018 (ref.120). In a South African study of patients who were hospitalized for severe respiratory illness, those with influenza virus infection together with laboratory-confirmed tuberculosis had a 4.5-fold greater risk of death121. HIV-1 largely drives the tuberculosis epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa, and the ‘triple-hit’ of HIV-1, tuberculosis and SARS-CoV-2 infection is consequently of considerable concern.

A preliminary study suggests that HIV-1 infection increases the risk of mortality from COVID-19 by 2.39-fold, and this increased risk seemed to be independent of suppressed HIV-1 viral load due to antiretroviral therapy. Individuals with current tuberculosis had a 2.7-fold greater risk of death122. These figures represent a modest increased risk compared with older age and co-morbidities such as diabetes in the same population, which suggests that HIV-1 and tuberculosis may not be considered major risk factors for COVID-19. Although this would be considered good news, further studies are awaited to confirm these initial observations.

The two main potential issues for using SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in individuals infected with HIV-1 are safety and efficacy. However, potential safety issues are likely to be restricted to use of certain vaccine modalities, such as live-attenuated or replicating vaccines, in individuals who are highly immunosuppressed. When considering vaccine efficacy, the magnitude and durability of immunity in individuals infected with HIV-1 for both vaccination against and natural infection with SARS-CoV-2 is unknown. To date, there are no reports describing immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 in individuals infected with HIV-1. It is possible that individuals with HIV-1 may have incomplete immune reconstitution and impaired immunity that may influence vaccine safety and efficacy, even if they are receiving antiretroviral therapy, owing to persistent immune activation and incomplete recovery of T cell and B cell immunity123,124. Suboptimal neutralizing antibody responses have been described following immunization against influenza virus or other pathogens in individuals infected with HIV-1 (ref.125). Weaker antibody responses and lower influenza virus-specific memory B cell responses in individuals infected with HIV-1 were directly related to CD4 counts126. It will be important to test candidate vaccines for their ability to generate immune responses in a range of high-risk groups, including patients with HIV-1. Several strategies may improve the magnitude and durability of vaccine responses in individuals infected with HIV-1, such as higher doses, booster immunizations and/or the use of adjuvants127. Substantive data on the clinical and immunological interaction of HIV-1, tuberculosis and COVID-19 will emerge from Africa in time for improved strategies to guide clinical management of patients who are co-infected and the vaccine regimens.

Finally, an important additional point to note is the indirect effects of COVID-19 on health in Africa within the setting of a high burden of infectious diseases. The WHO estimates that the disruption in vaccination due to disruption in supply could put 80 million infants at risk of contracting vaccine-preventable diseases128. Several countries have reported reduced uptake of tuberculosis testing, and patients failing to collect tuberculosis medication or antiretroviral therapy owing to overwhelmed health-care systems, lockdown interventions and public fear of contracting COVID-19 (ref.129). Mitigating these interruptions in prevention, diagnosis and treatment, and ensuring that essential health services continue, will ultimately lower the overall impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa.

Conclusions and outlook

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic presents an unprecedented global humanitarian and medical challenge. Although this has prompted unparalleled progress in the development of vaccines and therapeutics in many countries, it has also highlighted the vulnerability of resource-limited countries in Africa. Not only do these countries have limited testing capacity but the infrastructure to manufacture tests, vaccines and therapeutic drugs is largely absent, and few clinical trials are underway on the continent to combat SARS-CoV-2. Clearly, there is an urgent need for capacity development and the available resources should focus on solutions that are specific to the needs of the continent. For example, there is an urgent need to inexpensively manufacture viral antigens for serological testing: this will determine the seroprevalence of the virus where PCR-based testing is not available for mild infections. Therapeutics development should focus on repurposing existing drugs, or using convalescent plasma that can rapidly be used to treat infection and could be prioritized for individuals who are at high risk. Appropriate manufacturing partnerships need to be established to produce vaccines that could be tested and licensed on the continent, to limit reliance on global initiatives that may be overwhelmed by the global demand for a vaccine. In fact, this may present an opportunity for governments to finally invest in much-needed cGMP-compliant vaccine manufacturing facilities. Although the situation is unquestionably dire, Africa has an important role in the global fight against COVID-19, and the resilience and resourcefulness of the people are not to be underestimated.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the South African Medical Research Council with funds received from the South African Department of Science and Technology, core funding from the Wellcome Trust (203135/Z/16/Z) and funding from the South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation (Grant Number 64815).

Glossary

- Index cases

The first documented cases in a disease outbreak.

- Kawasaki disease

A rare condition associated with inflammation in blood vessels that most commonly presents in children under 5 years of age.

- Serology-based testing

A diagnostic test that measures the presence of antibodies in blood to determine exposure to pathogens or to diagnosis autoimmune diseases.

- Convalescent sera

Sera obtained from individuals who have recovered from an infectious disease and contain antibodies against the pathogen.

- Cytokine storm

A disproportionately large cytokine response that promotes inflammation and is harmful to the host.

- Tuberculin tests

Tuberculosis diagnostic tests that involve the intradermal injection of bacterial antigens to determine whether the recipient mounts an immune response at the site of injection.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Microbiology thanks M. Baylis, G. Dougan, S. Jiang and L. F. P. Ng for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Related links

Africa CDC: https://africacdc.org/covid-19

Africa Medical Supplies Platform: https://amsp.africa

Cape Bio Pharms: www.capebiopharms.com

Drug Discovery and Development Centre: http://www.h3d.uct.ac.za

RECOVERY trial: https://www.recoverytrial.net

SOLIDARITY trial: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/global-research-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/solidarity-clinical-trial-for-covid-19-treatments

The Biologicals and Vaccines Institute of Southern Africa: https://www.biovac.co.za

World Health Data Platform: https://www.who.int/data

Contributor Information

Emmanuel Margolin, Email: Emmanuel.margolin@uct.ac.za.

Edward P. Rybicki, Email: Ed.rybicki@uct.ac.za

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41579-020-00441-3.

References

- 1.Su S, et al. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drosten C, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu N, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen N, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou P, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang T, Wu Q, Zhang Z. Probable pangolin origin of SARS-CoV-2 associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr. Biol. 2020;30:1346–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 through recombination and strong purifying selection. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eabb9153. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb9153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guan WJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, et al. COVID-19 infection may cause ketosis and ketoacidosis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020 doi: 10.1111/dom.14057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palermo NE, Sadhu AR, McDonnell ME. Diabetic ketoacidosis in COVID-19: unique concerns and considerations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020 doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Diabetes Foundation. IDF Africa. IDFhttps://idf.org/our-network/regions-members/africa/welcome.html (2019).

- 15.Varatharaj A, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 in 153 patients: a UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiat. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30287-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1607–1608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viner RM, Whittaker E. Kawasaki-like disease: emerging complication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1741–1743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31129-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu X, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1663–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chinazzi M, et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.aba9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nkengasong JN, Mankoula W. Looming threat of COVID-19 infection in Africa: act collectively, and fast. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30464-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Hospital beds (per 10 000 population). WHOhttps://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/hospital-beds-(per-10-000-population) (2020).

- 22.Thornton J. Covid-19: keep essential malaria services going during pandemic, urges WHO. BMJ. 2020;369:m1637. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basson, A. Zimbabwe under strain as Malaria cases surge during COVID-19 fight. news24https://www.news24.com/Africa/News/zimbabwe-under-strain-as-malaria-cases-surge-during-covid-19-fight-20200424 (2020).

- 24.Li R, et al. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) Science. 2020;368:489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Our World in Data. Coronavirus (COVID-19) testing. Global Change Data Labhttps://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-testing#how-many-tests-are-performed-each-day (2020).

- 26.Saglietto A, D’Ascenzo F, Zoccai GB, De Ferrari GM. COVID-19 in Europe: the Italian lesson. Lancet. 2020;395:1110–1111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30690-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hellewell J, et al. Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8:e488–e496. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendelson M, Madhi S. South Africa’s coronavirus testing strategy is broken and not fit for purpose: it’s time for a change. SAMJ. 2020;110:429–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nkengasong J. Let Africa into the market for COVID-19 diagnostics. Nature. 2020;580:565. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corman VM, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Guardian (international edition). African countries unite to create ‘one stop shop’ to lower cost of Covid-19 tests and PPE. The Guardianhttps://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/jun/22/the-power-of-volume-africa-unites-to-lower-cost-of-covid-19-tests-and-ppe (2020).

- 32.Madhi SA, et al. COVID-19 lockdowns in low- and middle-income countries: success against COVID-19 at the price of greater costs. SAMJ. 2020;110:724–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fomsgaard AS, Rosenstierne MW. An alternative workflow for molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2 – escape from the NA extraction kit-shortage, Copenhagen, Denmark, March 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25:2000398. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.14.2000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broughton JP, et al. CRISPR–Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:870–874. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0513-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Long QX, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26:845–848. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deeks JJ, et al. Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staines HM, et al. Dynamics of IgG seroconversion and pathophysiology of COVID-19 infections. Preprint at. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.07.20124636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ibarrondo FJ, et al. Rapid decay of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in persons with mild COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2025179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stadlbauer D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans: a detailed protocol for a serological assay, antigen production, and test setup. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2020;57:e100. doi: 10.1002/cpmc.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okba NMA, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-specific antibody responses in coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lassaunière R, et al. Evaluation of nine commercial SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays. Preprint at. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.09.20056325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petherick A. Developing antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2020;395:1101–1102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30788-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Premkumar L, et al. The receptor binding domain of the viral spike protein is an immunodominant and highly specific target of antibodies in SARS-CoV-2 patients. Sci. Immunol. 2020;5:eabc8413. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abc8413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atkinson R, Burt F, Rybicki EP, Meyers AE. Plant-produced Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever virus nucleoprotein for use in indirect ELISA. J. Virol. Methods. 2016;236:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mbewana S, et al. Expression of Rift Valley fever virus N-protein in Nicotiana benthamiana for use as a diagnostic antigen. BMC Biotechnol. 2018;18:77. doi: 10.1186/s12896-018-0489-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han X, et al. The expression of SARS-CoV M gene in P. Pastoris and the diagnostic utility of the expression product. J. Virol. Methods. 2004;122:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Margolin E, et al. Co-expression of human calreticulin significantly improves the production of HIV gp140 and other viral glycoproteins in plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020 doi: 10.1111/pbi.13369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amanat F, Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: status report. Immunity. 2020;52:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gordon DE, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature. 2020;583:459–468. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beigel JH, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19 — preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]