Abstract

Takayasu's arteritis exposes to complications of varying severity, such as arterial stenosis, thrombosis, and more rarely aneurysms. Aortic dissection is a rare complication of Takayasu's disease, reported in few times in the literature, only 7 of which concern the abdominal aorta. We report the case of a 41-year-old woman followed for Takayasu disease for 15 years, who presented an asymptomatic and chronic dissection of the abdominal subrenal aorta. The patient underwent conservative medical treatment. After a follow-up of 17 months, the aortic dissection was still asymptomatic, with a stable appearance on follow-up imaging. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of asymptomatic aortic dissection as a rare complication of Takayasu disease.

Keywords: Takayasu disease, Dissection, Subrenal aorta

Introduction

Takayasu disease is arteritis that involves the aorta, its major branches, and less often the pulmonary arteries. It occurs more commonly in young females, of the second or the third decade.

It may cause arterial stenosis, occlusions, and aneurysm, which lead to ischemia [1]. Aortic dissection is a rare complication of Takayasu's arteritis; 5% of aortic aneurysmal lesions secondary to Takayasu disease are complicated by dissection [2].

In this article, we recall the radiological presentation of Takayasu disease, and we discuss a case of an isolated chronic asymptomatic dissection of the abdominal aorta as an unusual complication of this pathological entity.

Case presentation

A 41-year-old woman followed for Takayasu disease for 15 years. The initial presentation of Takayasu disease in the patient was at the age of 26 years. At that time, the patient reported bilateral carotidynia, persistent asthenia, and vertigo. Clinical and paraclinical investigations showed erythema nodosum, hypertension at 166/91 mmHg with a difference of 13 mmHg systolic pressure between the 2 arms, decreased brachial artery pulse, a rise of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) at 89 mm/hour, and angiographic evidence of bilateral narrowing in carotid arteries and left subclavian artery. The diagnosis of Takayasu arteritis was based on the presence of 2 major criteria and 3 minor criteria according to the Sharma criteria of 1995. The outcome was favorable under corticosteroid treatment with resolution of clinical and biological signs.

The patient was lost to follow-up. Afterward, she consulted in emergency at the age of 35 for the same clinical symptoms (carotidynia, asthenia, and vertigo). CT angiography of the neck, chest, and abdomen was performed. It showed a smooth and circumferential arterial thickening in the carotid arteries with delayed enhancement related to the disease's active nature, associated with partial stenosis of the superior mesenteric artery without any impact on the downstream arterial branches. After the administration of corticosteroids, the patient's condition improved.

Recently the patient presented moderate and intermittent postprandial abdominal pain. The inflammatory biological tests were negative.

A CT angiography of the abdomen was performed. It showed total occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery (Fig. 1) without signs of ischemia, explaining the moderate and intermittent postprandial abdominal pain in the patient. This pain is due to decreased intestinal arterial flow, which was supplied by collaterals arising from the celiac trunk.

Fig. 1.

(a): Axial section pointing out the superior mesenteric artery occlusion (pink arrow), with the hypodense and regular parietal thickening of the aorta (yellow arrow). (b): Maximum intensity projection reconstruction (MIP) on the axial section, showing the superior mesenteric artery occlusion (pink arrow), and partial stenosis <50% of the ostium of the left renal artery (arrowheads). (Color version available online.)

In the arterial phase, we found an incidental intimal flap on the subrenal aorta without endoluminal thrombosis (Fig. 2), denoting aortic dissection. This lesion was associated with a low attenuated, circumferential, and regular thickening of the aortic wall, compatible with Takayasu disease (Figs. 1 and 2). In the delayed phase, there was no parietal enhancement, proving the chronicity of the abnormalities. There were no atheroma plaques and no parietal calcifications.

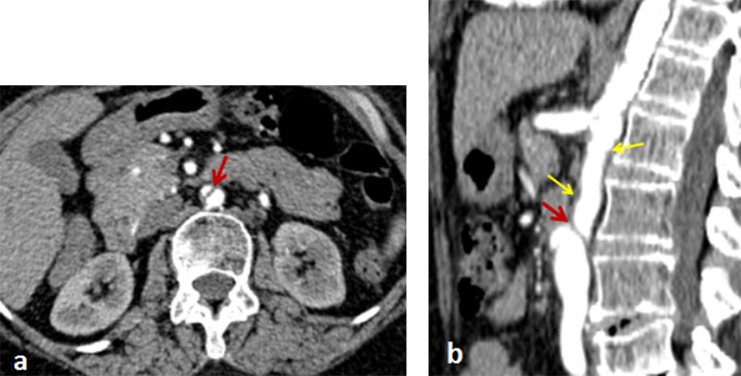

Fig. 2.

Axial (a) and sagittal (b) sections of the abdominal CT angiography in the arterial phase, denoting intimal flap of the subrenal aorta without thrombosis (red arrow); associated with hypodense and regular parietal thickening (yellow arrows) related to Takayasu disease. (Color version available online.)

We noticed partial stenosis (<50%) on the ostium of the left renal artery (Fig. 1b). Renal Doppler ultrasound performed subsequently did not show abnormality of the renal vascularization.

The patient underwent conservative medical treatment with improvement in her intermittent abdominal pain. The aortic dissection is still asymptomatic on the follow-up of 17 months with a stable appearance on follow-up imaging (3 Doppler ultrasounds and 1 CT angiography).

Discussion

The diagnosis of Takayasu's disease is based on the convergence of clinical, biological, and radiological elements grouped according to Sharma criteria [1]. Classically, there are 2 evolutionary phases of Takayasu's disease. The initial stage is called "preocclusive," characterized by general and nonspecific signs, such as arthralgia, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, carotidynia, and sometimes ocular lesions as episcleritis or anterior uveitis [2]. The "occlusive" or "vascular" phase is characterized by symptoms related to arterial stenosis or aneurysm; therefore, ischemic complications are in the foreground [2].

We can find the increasing of some nonspecific biological markers like C-reactive protein (CRP), alpha-2 globulins, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and fibrinogen. Pentraxin-3 is currently considered an activity marker for Takayasu disease [3].

Radiological exploration is founded on Doppler ultrasound, CT angiography, and Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) that are far more sensitive than angiography on detecting lesions at the initial stage [4].

The essential imaging finding is the mural thickening of an arterial segment, typically smooth, circumferential, and exceeding 3 mm, forming the « macaroni » sign. This aspect is found at 97% in the preocclusive phase, with a high prevalence in the carotid and subclavian arteries [2,4].

The disease's activity can be assessed on postcontrast delayed phase images (10 minutes after injection of contrast agent), which shows a delayed enhancement of the active thickening as a "double-ring sign." The transition zones between the pathological and healthy arterial segments are abrupt, giving the appearance of a suspended lesion.

Parietal calcifications can be present at the chronic phase at variable proportions, and it may take a long-form as "porcelain aorta." The coexistence of active and inactive lesions is possible [4].

Takayasu disease's lesions can be complicated by arterial stenosis, aneurysms, baroreceptors abnormalities, and a drop in arterial compliance, with repercussions on the blood flow and arterial hypertension [2,5]. Ischemia is a frequent complication that occurs following hypoperfusion.

Our patient presents a nonaneurysmal and asymptomatic dissection Stanford type B of the subrenal aorta sparing the iliac arteries (Fig. 2). Dissection Stanford type B is more frequent than type A in association with Takayasu disease [6]. To our knowledge, our case is the first asymptomatic aortic dissection as a complication of Takayasu disease. The presence of a circumferential and regular parietal thickening of the aorta is typically related to an inflammatory origin that is compatible with Takayasu disease, and less likely consistent with an atheromatous background, given the absence of calcifications and the young age of the patient. The literature review reports only a few cases of aortic dissection complicating Takayasu disease, and only 7 implied an isolated abdominal aorta, all of which were symptomatic [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11].

The surgical treatment indications of aortic dissection complicating Takayasu disease are not clearly defined, dominated by ischemic manifestations. Nevertheless, it is recommended to perform the surgery beyond the inflammatory phase of the disease. In the Yang KQ series of 10 patients who had aortic dissection as a complication of Takayasu Disease (2 of whom had isolated abdominal aortic dissection), 9 patients underwent conservative treatment; 1 patient underwent endovascular repair. Among the 7 cases of isolated abdominal aortic dissection complicating Takayasu disease reported in the literature, only 1 patient is surgically treated considering ischemic lesions [8]. The endovascular treatment is still a useful alternative applied in simple cases, especially on the descending aorta, with a good prognosis in the short and medium-term [6,8,12].

Conclusion

Aortic dissection is an uncommon complication of Takayasu disease; only a few cases are reported in the literature. Our case corresponds to a chronic asymptomatic dissection of the subrenal aorta in a young patient followed for Takayasu disease for 15 years.

Consent

The authors attest that the figures associated with this manuscript are anonymized. The paper does not contain data that could identify the patient.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sharma BK, Jain S, Suri S, Numano F. Diagnostic criteria for Takayasu arteris. Int J Cardiol. 1996;54:127–133. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(96)88783-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirault T., Messas E. La maladie de Takayasu. Rev Med Int. 2016;37(4):223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2015.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagna L, Salvo F, Tiraboschi M, Bozzolo EP, Franchini S, Doglioni C. Pentraxin-3 as a marker of disease activity in Takayasu arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:425–433. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-7-201110040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma LY, Li CL, Ma LL, Cui XM, Dai XM, Sun Y. Value of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography of the carotid artery for evaluating disease activity in Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:24. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1813-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comarmond C, Dessault O, Devaux J-Y, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Resche-Rigon M. Myocardial perfusion imaging in Takayasu arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:2052–2060. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang KQ, Yang YK, Meng X, Zhang Y, Zhang HM, Wu HY. Aortic Dissection in Takayasu Arteritis. Am J Med Sci. 2017;353(4):342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Civilibal M, Sever L, Numan F, Altun G, Ocak S, Candan C. Dissection of the abdominal aorta in a child with Takayasu's arteritis. Acta Radiol. 2008;49:101–104. doi: 10.1080/02841850701564491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theresa K, Jean-Marc A, Jean-Paul DVH, Jean EF. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of a Takayasu disease on an abdominal aortic dissection. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25:556. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lie JT. Segmental Takayasu (giant cell) aortitis with rupture and limited dissection. Hum Pathol. 1987;18:1183–1185. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silbert PL, Matz LR, Larbalestier R, Lawrence-Brown M. Abdominal aortic dissection due to idiopathic medial aortopathy in a 32-year-old Caucasian man. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1992;33:457–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyagi S, Nigam A. Aortic dissection: a rare presenting manifestation of Takayasu's aortitis. Indian Heart J. 2008;60:58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silaschi M, Byrne J, Wendler O. Aortic dissection: medical, interventional and surgical management. Heart. 2017;103:78–87. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]