Abstract

Background and purpose

Low-profile self-expandable stents have increased the number of intracranial aneurysms treated by endovascular means. The new low-profile visible intraluminal support device LVIS EVO (Microvention), the successor of LVIS Jr, is a self-expandable and retrievable microstent system, designed for implantation into intracranial arteries with a diameter up to 2.0 mm. In this retrospective study we aimed to elucidate the technical feasibility and clinical safety of the novel LVIS EVO stent for stent-assisted coil embolisation of intracranial aneurysms.

Materials and methods

A single centre technical report of the first six consecutive cases of stent-assisted coil embolisation with the novel LVIS EVO stent for the treatment of unruptured or recanalised intracranial aneurysms. Records were made of basic demographics, aneurysmal characteristics, device properties and related technical details, adverse events, clinical outcomes and occlusion rates on available radiological follow-up.

Results

Six LVIS EVO devices were successfully implanted in all subjects to treat a total number of six intracranial aneurysms. No device-related intraprocedural complications were seen. At early clinical follow-up six out of six (100%) patients had a modified Ranking score of 0–1. Early angiographic and cross-sectional radiological follow-up, available in five out of six (83.3%) of the patients confirmed unchanged aneurysmal occlusion rates. A minor, transitory neurological deficit was recorded in one of the six (16.6%) patients. Mortality was 0%.

Conclusions

Preliminary experience in this subset of our patients confirms a notably improved technical behaviour of the novel LVIS EVO stent system when compared to its ancestor LVIS Jr. The enhanced visibility of the stent and the refined delivery/retrieval capabilities of the stent further increase the safety margins of the devices profile, especially in cases of tortuous anatomy.

Keywords: Aneurysm, embolisation, stent, LVIS EVO, intraluminal device

Introduction

Almost two decades have passed since the introduction of the first dedicated intracranial stent for assisted coil embolisation of wide-necked cerebral aneurysms.1 As a result, a handful of techniques and different stent configurations have been developed to provide improved durability and to facilitate coil embolisation in situations that would be untreatable with coils alone.2–4 The early versions of these stents needed be delivered through microcatheters with an internal diameter (ID) of 0.027 and 0.021 inches and the suboptimal physical properties of both the stents and microcatheters was a limiting factor. The rapid technological advancements and the recent introduction of new low-profile microstent systems including Neuroform Atlas (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA), Acandis Acclino (Acandis, Pforzheim, Germany), LEO Baby (BALT, Montmorency, France), and low-profile visible intraluminal support (LVIS) Jr (Microvention, Tustin, CA, USA), have allowed neurointerventionalists to overcome these issues. These low-profile devices can be deployed via microcathers with an ID of 0.0165 inches with the aim to enhance distal stent delivery into smaller and more delicate arteries and thereby increase the safety and ease of use. One of the most recently introduced low-profile stents is the low-profile visible intraluminal support (LVIS) EVO device (Microvention, Tustin, CA, USA). The LVIS EVO is a self-expandable, braided implant and basically represents a new improved version of its ancestor LVIS Jr. This stent uses drawn filled tube (DFT) technology to optimise visibility and the shape memory properties of nitinol. The visibility modifications made to the stent and the improvements in the delivery system aim to facilitate stent-assisted embolisation of intracranial aneurysms arising from parent vessels 2.0 to 4.0 mm.

The purpose of this paper is to evaluate and report the technical nuances and early clinical experience in the first-time use of newly introduced second generation LVIS EVO for stent-assisted embolisation of cerebral aneurysms.

Methods

Adherence to ethical standards and requirements

An informed consent in written form was given by each patient or legal representative at least 12 hours before the procedure. Patients’ consents for the data management and future anonymous publication were also collected. All the included study subjects were informed in written form about the applications of the general data protection regulation (GDPR). This study was approved by local ethics committee and was designed and performed according to its policies and guidelines.

Study population and data collection

The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were followed to aid the authors in ensuring high quality presentation of the conducted observational study. These guidelines were followed for collection and reporting of the data.5

After CE mark labelling in November 2019 of the LVIS EVO microstent system, the implant was added to our armamentarium and used for stent-assisted embolisation of unruptured, recurrent aneurysms or those with significant remnant after endovascular coiling or surgical clipping. Patients harbouring acutely ruptured cerebral aneurysms were not treated with this device.

LVIS EVO assisted coiling was adjudicated by careful planning and consensus among a multidisciplinary team of neuroradiologists, neurosurgeons and neurologists considering multiple factors including the morphology of the target aneurysm.

The indications for embolisation were defined as a wide-necked or recurrent cerebral aneurysm. The presence of parent vessel incorporation at the aneurysmal neck and a complex bifunctional location were also considered characteristics that warranted stent-assisted embolisation. Aneurysmal morphological classification was conducted after careful evaluation of a rotational angiogram (GE Innova 3131 IQ). Wide-necked aneurysms were defined as aneurysms with dome-to-neck ratio of less than 2 or a neck diameter of more than 4 mm. Recurrent aneurysms or those with significant post-treatment remnant were assessed according to the modified Raymond and Roy classification.6

Study population

Our study consisted of six patients treated between February and March 2020. Patient details and aneurysmal anatomical locations and characteristic are summarised in Table 1. The average age of the treated patients at the time of embolisation was 53 years (range 40–60). Women made up half of the study population. Five of the aneurysms were located across the anterior cerebral circulation: one in the A2 portion of the anterior cerebral artery, one at the level of the anterior communicating complex and three at the level of the middle cerebral artery bifurcation. However, one lesion involved the tip of the basilar artery. All of the treated aneurysms were small in size (≤10 mm) and with saccular morphology. The average dome height of the aneurysms was 7.53 mm (range 3.5–10 mm). The mean neck width was 5.45 mm (range 2.8–8.8 mm).

Table 1.

Aneurysmal characteristics of the patients with procedural data, immediate and follow-up outcomes.

| Patient | Age | Location | Aneurysmal size (mm) | Neck size (mm) | Parent artery proximal diameter (mm) | Parent artery distal diameter (mm) | Angulation (degree)* | Procedural complications | Technical success | Raymond class at final DSA run | Fluoroscopy time | Raymond class at first follow-up | mRS score at first |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60s | Pericallosa (recurred) | 11.5 | 6 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 60 | None | 100% | 1 | 23 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 40s | AComA (recurred) | 3.5 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 45 | None | 100% Recapture need | 1 | 20 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 60s | BA tip | 5 | 6 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 60 | None | 100% | 1 | 25 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 40s | MCA (incidental) | 12 | 8.8 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 60 | None | 100% | 1 | 33 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | 40s | MCA (incidental) | 7.8 | 6.1 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 45 | None | 100% Recapture need | 1 | 37 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 | 50s | MCA (incidental) | 5.4 | 3 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 45 | None | 100% | 1 | 21 | 1 | 0 |

*The degree of the angulation was measured as the angle of incidence between the parent vessel (proximal) and the vessel to receive the stent (distal). Angles were measured on intra-procedural three-dimensional angiography.

Pericallosa: pericallosal artery; AComA: anterior communicating artery; BA tip: basilar artery tip; MCA: middle cerebral artery; mRS: modified Rankin scale.

The mean distal diameter of the target parent artery was 2.3 mm (range 2.1–2.8) and the mean proximal diameter was 2.7 mm (range 2.3–3.6 mm). Three of the aneurysms had previously been treated with plain coiling in the acute rupture setting. The rest or 50% of the aneurysms were found incidentally as part of other radiological or clinical evaluations.

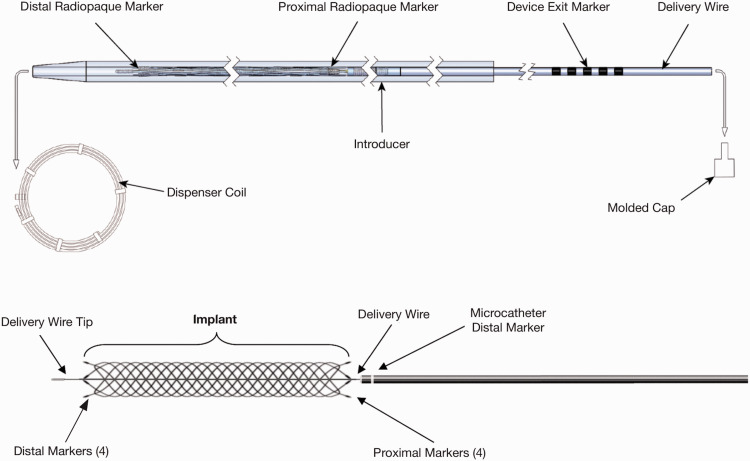

Device information: LVIS EVO stent system

The LVIS EVO is a self-expanding DFT, single wire-braided stent. The single wire is braided 16 times. There are four proximal and distal markers and the device, similar to the LVIS, has slightly flared ends. It should be introduced only by means of a Headway 17 microcatheter (0.017-inch inner diameter) or Scepter C/Scepter XC occlusion balloon. The LVIS EVO device is available in 2.5, 3.0, 3.5 and 4.0 mm diameters with a potential maximum expansion up to 0.2 mm past nominal. The device is available in a variety of lengths between 12 mm and 34 mm; the device foreshortens more than its predecessor LVIS Jr (Figures 1 and 2). The stent can be recaptured up to the ‘point of no return’ which is represented by the proximal radio-opaque markers.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the new low-profile visible intraluminal support (LVIS) EVO microstent system components. Figure used with permission of MicroVention.

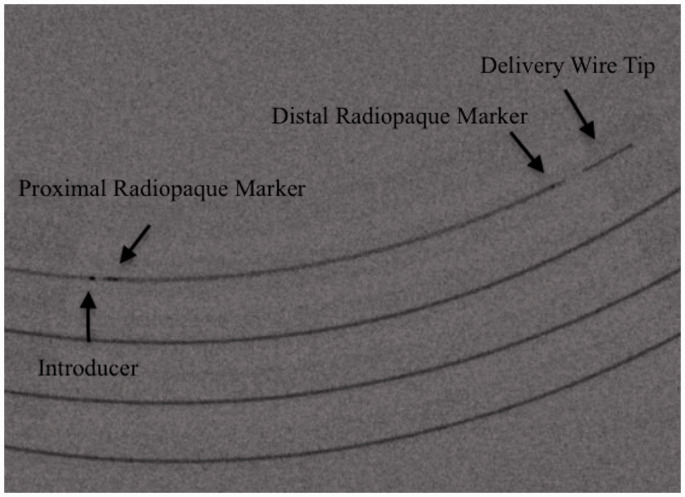

Figure 2.

Fluoroscopic visualisation of the low-profile visible intraluminal support (LVIS) EVO microstent system components (arrows, text). The device is packaged sterile inside a dispenser coil as a single unit within an introducer sheath.

Anti-aggregation and anticoagulation

Prior to each procedure, the patients were pretreated for at least five consecutive days with a daily dose of aspirin 100 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg. The level of anti-aggregation activity provided by thienopyridine was assessed by the P2Y12 VerifyNow test (Accumetrics, San Diego, CA, USA).

Patient ‘non-responders’ to clopidrogrel received an oral dose of either 1 × 10 mg prasugrel or 2 × 90 mg ticagrelor daily. No LVIS EVO was placed unless a significant platelet inhibition was confirmed (i.e. <120 P2Y12 reaction units).7–9 Heparinising with 5000 IU was conducted at the start of each procedure, after acquiring access to either the femoral or distal radial artery. The flush systems used for the microcatheters contained heparin (2500 IU per litre).

Daily prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy was recommended for at least 6 months after discharge following which aspirin was continued for life.

Procedural information

All procedures were conducted under general anaesthesia. A 6F guiding system was introduced into the proximal internal carotid artery or vertebral artery through a femoral or distal radial arterial access. As per our procedural protocol, rotational angiography was performed followed by three-dimensional reconstruction to ensure better understanding of the surrounding anatomy and the geometrical characteristics of the target aneurysm and the involved parent arteries. After acquiring the most accurate working projection two 0.017-inch microcatheters were navigated into the one branch of the parent artery and into the aneurysmal dome. Prior to stent navigation and deployment several initial loops of the first framing coil were inserted into the aneurysmal dome in order to mitigate catheter movement due to catheter interaction on stent delivery. Secondly, the LVIS EVO microstent system was fully loaded into the second microcatheter and completely deployed into the selected arterial branch and across the aneurysmal neck as per a standard jailing technique. The stent-loaded delivery wire was carefully removed followed by the complete coil embolisation of the aneurysm via the jailed microcatheter. If needed, to perform complete embolisation of the aneurysm, the catheter was repositioned and the stent-struts crossed.

Clinical and radiological follow-up

According to our institutional policy, when it comes to using new devices or techniques the first radiological follow-up with digital subtraction angiography (DSA) or cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were scheduled at 30 days, 3 and 12 months after the treatment. The angiographic evaluations were conducted by SS (12 years of experience) and AS (5 years of experience).

The clinical and neurological status evaluation was performed by certified vascular neurologists using the modified Rankin scale.10

Results

Procedural results and device data

Treatment of all the reported cases was carried out electively over a total number of six interventions. Stent-assisted coil embolisation via the LVIS EVO microstent system was the primary treatment strategy and the only technique used in this cohort. A total of six LVIS EVO stents was successfully deployed. The LVIS EVO stent was inserted and advanced easily in the used 0.017-inch Excelsior SL 10 (Stryker) (Figure 3) microcatheter in all cases, despite the fact that the used microcatheter was not officially recommended for this particular purpose. We did not observe any structural abnormalities (i.e. distal or proximal ‘fish mouthing’, stent twisting or migration) of the device during embolisation. Complete recapture inside the microcatheter with further reposition of the device was required in two out of the six patients. All six stents were positioned at the desired location with fluoroscopically confirmed complete neck coverage. However, slight foreshortening of the deployed stent was observed in two cases.

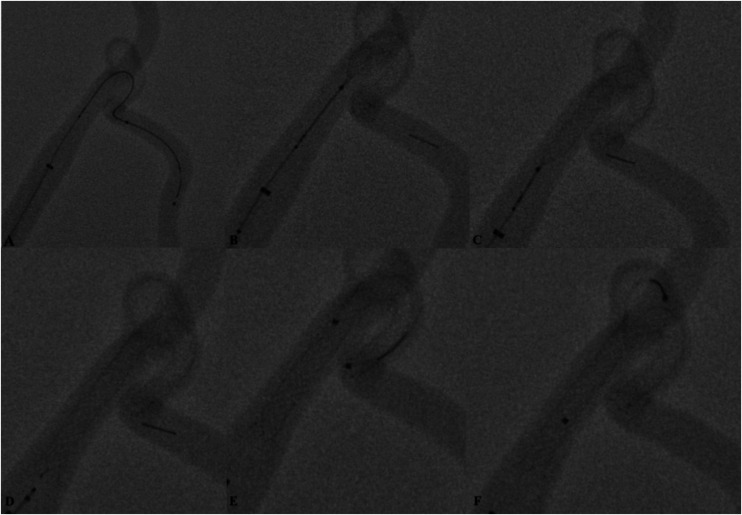

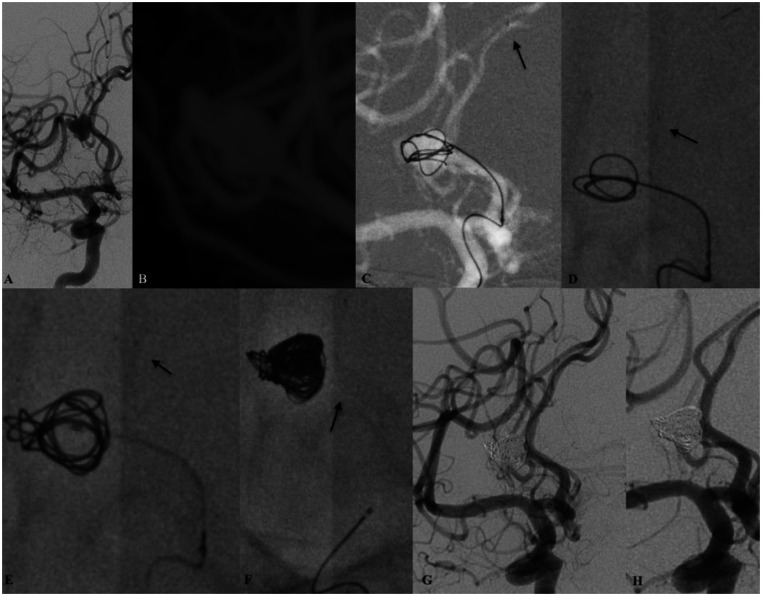

Figure 3.

Preclinical bench-side testing of the device was performed on several artificial aneurysm models (Elastrat, Geneva, Switzerland) to understand better the technical properties and capabilities of the device. Access to the target aneurysm and the parent branch was performed with a SL 10 microcatheter (Stryker Neurovascular, Kalamazoo, USA) (a). Under fluoroscopy, multiple delivering and recapturing manoeuvres were performed to understand better the behaviour (b), (c), (d) of the stent. Maximum wall apposition of the stent to the vessel wall and complete neck bridging was achieved by applying axial force to the delivery system (delivery wire/microcatheter) during slow continuous deployment. Trouble-free navigations with the microcatheter within the total length implant over the delivery wire were possible (e). Numerous navigations (f) over the struts of the stents were performed with straight and angulated microcatheters. During testing we did not observe any macroscopic and structural abnormalities of the stent inside the plastic model (i.e. distal or proximal ‘fish mouthing’, stent twisting or migration).

In all cases the microcatheter was ‘jailed’ by the stent during coil embolisation. In two cases repeat catheterisation of the aneurysm through the struts of the stent with the coiling microcatheter was performed to ensure complete embolisation.

At the end of the procedure as per our technical protocol a final pass through the whole stent with a 0.017-inch delivery microcatheter was performed to guarantee optimal wall apposition of the implant. Average fluoroscopy time was 26.5 minutes (range 21–37 minutes).

Immediate angiographic/clinical results and follow-up

Immediate angiography results showed that total aneurysmal occlusion rates of Raymond and Roy class 1 was achieved in all patients (Figure 4). There were no procedural-related complications (i.e. acute in-stent stenosis), vessel perforation or iatrogenic vasospasm during the embolisation.

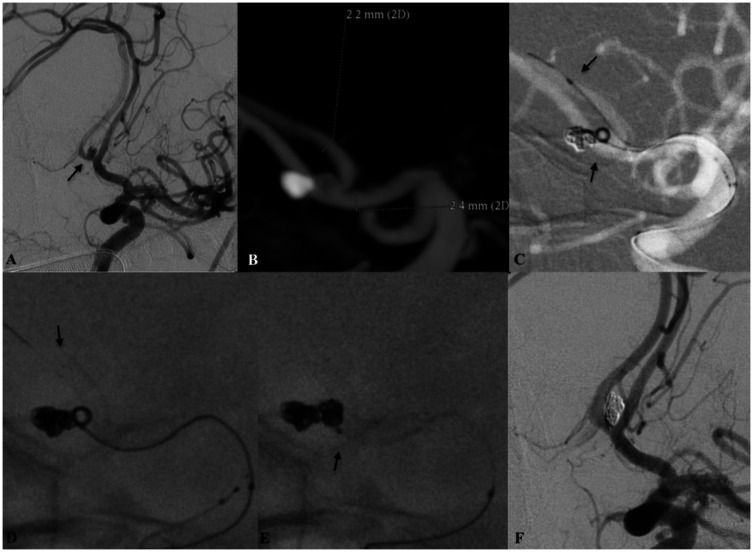

Figure 4.

Patient harbouring a recurrent and previously coiled anterior communicating artery (AComA) aneurysm. (a) Working oblique projection demonstrating the recanalised part of the aneurysm (arrow). (b) Maximum intensity projection (MIP) image from the intraprocedural three-dimensional rotational digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the left internal carotid artery. Note the distal and the proximal diameters of the target vasculature. Under roadmap (c) guidance and after anchoring the coiling microcatheter (arrow pointing upwards) deployment of the low-profile visible intraluminal support (LVIS) EVO stent had been initiated. Although the anatomical relationship between the contralateral A2 and the ipsilateral A1 is acutely angulated complete expansion ((d) arrow – distal LVIS EVO radio-opaque markers) of the device with maximal wall apposition can be noted. The 0.017-inch microcatheter used for stent delivery was removed following the complete embolisation of the aneurysm (e). The ‘jailed’ microcatheter remained stable during the embolisation ((e) arrow). (f) Final DSA run demonstrated the complete embolisation of the aneurysm. There were no changes to the anatomical configuration or the patency of the target vasculature and the AComA complex.

There were no intra-procedural adverse events and no procedure-related mortality. Results from clinical and neurological examinations from all patients at discharge remained unchanged from baseline. However, early post-procedural complications (i.e. within 30 days) were clinically and radiographically established in one patient. This patient was treated for a basilar apex aneurysm via LVIS EVO stent-assisted coiling. Exactly 11 days after the treatment the patient reported tingling sensations across the left arm. The following neurological examination did not reveal anything unusual. Cranial MRI was conducted and a small hyperintense T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) lesion of the left inferior cerebellar peduncle adjacent to the medulla oblongata was seen. Time of flight (TOF) imaging and the following DSA examination did not reveal any abnormal findings in the posterior circulation. The patient reported complete reversal of the initial symptoms on the first clinical follow-up at 30 days.

Five of the treated patients underwent first month DSA and cross-sectional MRI follow-up scan (mean follow-up period 28 days, range 11–31 days). Among those patients, complete occlusion (RR 1) was observed in all cases (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Endovascular embolisation of a saccular cerebral aneurysm of the right pericallosal artery. (a) Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) run from the right internal carotid artery demonstrating the target aneurysm. Intraprocedural three-dimensional rotational DSA (b) maximum intensity projection (MIP) reconstructions confirms the relative wide neck of the aneurysm. Right internal carotid artery roadmap imaging (c) demonstrating the anchoring of the coiling microcatheter with few initial loops right after the distal navigation of the deploying microcatheter (arrow). Deployment of the low-profile visible intraluminal support (LVIS) EVO stent ((d), (e) arrows – distal radio-opaque markers of the stent). The sufficient radial force of the stent permitted the migration of the coiling microcatheter. After solid and complete coil structuring was achieved the second microcatheter was removed (e). The implant remained stable at the end of the procedure (e, arrow). Complete embolisation RR1 was observed at the final DSA run (g) as well as complete patency of the distal cerebral vasculature. At 30-day follow-up angiography the status of the aneurysmal occlusion remained unchanged.

There was no in-stent stenosis or side branch occlusion in this series. Detailed fluoroscopic analysis proved that the position of the implants at follow-up remained the same as their initial deployment position. Further radiological follow-up at 6 and 12 months are scheduled and pending.

Discussion

The present paper reports the first real-life, in-human clinical and technical results with the recently introduced LVIS EVO microstent system for the treatment of complex recurrent or wide-necked cerebral aneurysms. Our observations are based on the fact that adjunctive coil embolisation via either temporary or permanent stenting is used in up to 60% of 260 cases annually by our neurointerventional team – SS (senior) and AS (junior).11–13

The early observations indicate that the device’s technical behaviour shows subjective non-inferiority in comparison with the already reported preliminary outcomes of its ancestors – LVIS Jr or any other similar low-profile endoluminal device.14–19

In our limited study sample, the implant demonstrated solid technical success with a good safety profile. The stent has been easily deployed at the desired location in all our patients. We noted an improvement in terms of implant radio-opacity and visibility, which according to our experience facilitates the deployment of the stent itself. The LVIS EVO uses DFT technology to optimise visualisation and is similar in this regard to the Acandis Accero,20 the Silk Vista Baby21–23 and the p48.24,25 In our series there was no evidence of incomplete aneurysmal neck coverage or compromised stent/vessel relationship which is a well-known limitation of braided-cell designed stents.14 We did not use any post-deployment angioplasty techniques; however, as per our local stent embolisation protocol, post-deployment navigation with the delivery microcatheter was performed in all cases.

Our results suggest that the new LVIS EVO microstent system is technically applicable in distal arterial vasculature with diameters less than 2.1 mm. The mean distal parent vessel diameter in our series was 2.3 mm. The tolerance of the stent is of a major concern when it comes to one being embedded into such delicate distal arteries. Successful stent deployment and smooth navigation were unarguably facilitated by three facts. First, the LVIS EVO system is fully compatible with the 0.017-inch microcatheter. This allows easy distal navigation into smaller arterial sites. Second, the stent harbours a new lower profile delivery wire of 0.0020 inches and optimised braid angle, which according to our experience translates into improved delivery and deployment of the stent in angulated configurations and torturous anatomy. Last but not least, the mount wire feature of the LVIS EVO offers the operator the ability to recapture the implant inside the microcatheter and re-deploy if necessary. Technically speaking, the deployment of the new LVIS EVO stent does not differ from that of previous braided stents, which will result in a flatter learning curve for this new stent. Furthermore, due to pharmacoeconomic reasons we found that the system can be safely handled with the marked ‘off-label’ 0.017-inch Excelsior SL 10 (Stryker) microcatheter.

Even though the stent comes in a smaller nominal diameter, smaller cell size and increased metal coverage of up to 28%, we did not encounter any difficulties in navigating a microcatheter through the struts of the stent for further coiling. Moreover, during our preclinical testing of the device on multiple reproducible aneurysmal models and different technical configurations we noted impressive ‘semi-compliance’ between the coiling microcatheter and the struts of the stent while passing through. However, it is already suggested that the smaller cell size could potentially permit the expansion of a second stent at the intersection point in cases where Y or X-stenting techniques are considered.26 In addition, we consider this new stent system as a perfect candidate for some alternative stenting techniques such as the ‘Flow-T’ setting or modified deployment manoeuvres such as the ‘railroad switch’.27,28

On the contrary, there is a certain concern regarding the new LVIS EVO stent observed in our series. Based on the discretion of the main operator and the fact that the new system comes with reduced nominal diameter and potentially lower radial force, each stent we used was slightly oversized with minimum 0.25 mm to the diameter of the target parent artery. We noted premature foreshortening of the implant during deployment that occurred in two cases. Fortunately, this did not result in reduced aneurysmal neck coverage or malposition of the stent. Theoretically speaking, this could probably be due to the fact that we wanted to maximise neck coverage and to increase the comfortability of the stent to the vessel wall by applying additional axial force over the delivery wire and the microcatheter in controlled fashion during deployment. In such cases, and if this precaution is undertaken, we suggest that the main operator has to remain cautious for potential ‘kick-back’ of the delivery microcatheter and the wire at the time of full stent deployment.29

One alternative possible explanation to explain the foreshortening seen in our cases could be the fact that both stents were deployed into vessels in which the distal calibre was larger than the proximal calibre (see Table 1). We have compared our preliminary technical results with those recently published for the predecessor LVIS Jr stent (Table 2).

Table 2.

Review of previous and recently published notable case series with LVIS Jr.

| Author | Year | Aneurysm treated with LVIS Jr (n) | Ruptured (n) | Technical success (%) | Procedural-related complications | Immediate complete occlusion (n, %) | Complete occlusion at available follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim | 2020 | 15 | 15 (100%) | 100% | 0% | 6 (40%) | 10 (83%) |

| Santillan | 2018 | 25 | 7 (28%) | 96% | 3 (12%) | 18 (72%) | 14 (70%) |

| Alghamdi | 2016 | 43 | 3 (7%) | 100% | 3 (7.5%) | 36 (83.7%) | 36 (90%) |

| Grossberg | 2016 | 85 | 17 (20%) | 98.8% | 8 (9.41%) | 36 (43%) | 35 (71%) |

| Shankar | 2016 | 100 | 13 (13%) | 100% | 23 (23%) | 52 (52%) | 61 (61%) |

| Gross | 2018 | 27 | 0 | 81% | 4 (15%) | 11 (41%) | 14 (67%) |

LVIS: low-profile visible intraluminal support.

Our study reports the complete occlusion of all six aneurysms at the time of coiling and at early (30-days) DSA and cross-sectional imaging follow-up. Similar results in terms of immediate aneurysmal occlusion have already been published in previous studies with the ancestor LVIS Jr stent.15,30,31

There were no intra-procedural complications neither mortality, nor permanent neurological deficits in this series. Transient ischaemic symptoms during the early post-embolisational period occurred in one patient. In this case we did not manage to identify any potential link between the procedure or the device and the anatomical location where the ischaemic changes were noted. A possible explanation of the latter could be the presence of cardiac arrhythmia and a compromised anticoagulation regime intake by the patient.

At early clinical and neurological follow-up examinations patient results remained at baseline. Although there is some key difference between the study population, clinical and radiological follow-up data and slightly different technologies, our results are generally speaking similar to those reported in recently published case series, multicentre trials and reviews involving the ancestor LVIS Jr stent or conceptually similar braided stents.32–38

Limitations

We acknowledge the fact that our study has some limitations: first and foremost, the subjective comparison mainly between two different available technologies. The reported results are limited by the authors’ individual experience and techniques. Secondly, and maybe most importantly, is that this study involves a small study sample and that we do not have mid and long-term follow-up data on our patients owing to the recent introduction of this stent on the market. This is why the reported results should be taken into consideration with caution.

Notably, our paper adds some new interesting data to the existing literature because it reports the first in-human technical experience and nuances with the recently introduced low-profile braided stent.

Conclusion

Technical and early clinical results with the new LVIS EVO stent are promising. The LVIS EVO combines easy navigation, excellent visualisation and re-capture ability with the ability to be deployed through low-profile microcatheters. Further investigations are needed to determine the safety and the efficacy of this new device.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Stanimir Sirakov https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6034-5340

References

- 1.Akpek S, Arat A, Morsi H, et al. Self-expandable stent-assisted coiling of wide-necked intracranial aneurysms: a single-center experience. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26: 1223–1231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiotta AM, Gupta R, Fiorella D, et al. Mid-term results of endovascular coiling of wide-necked aneurysms using double stents in a Y configuration. Neurosurgery 2011; 69: 421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fargen KM, Mocco J, Neal D, et al. A multicenter study of stent-assisted coiling of cerebral aneurysms with a Y configuration. Neurosurgery 2013; 73: 466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow MM, Woo HH, Masaryk TJ, et al. A novel endovascular treatment of a wide-necked basilar apex aneurysm by using a Y-configuration, double-stent technique. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25: 509–512. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61: 344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mascitelli JR, Moyle H, Oermann EK, et al. An update to the Raymond–Roy occlusion classification of intracranial aneurysms treated with coil embolization. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almekhlafi MA, Goyal M. Antiplatelet therapy prior to temporary stent-assisted coiling. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: E6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griessenauer CJ, Jain A, Enriquez-Marulanda A, et al. Pharmacy-mediated antiplatelet management protocol compared to one-time platelet function testing prior to pipeline embolization of cerebral aneurysms: a propensity score-matched cohort study. Neurosurgery 2019; 84: 673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonetti DA, Jankowitz BT, Gross BA. Antiplatelet therapy in flow diversion. Neurosurgery 2020; 86: S47–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiberger CJ, Kazi S, Mehta TI, et al. Effects on stroke metrics and outcomes of a nurse-led stroke triage team in acute stroke management. Cureus 2019; 11: e5590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirakov S, Sirakov A, Minkin K, et al. Early clinical experience with Cascade: a novel temporary neck bridging device for embolization of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 2020; 12: 303–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sirakov S, Sirakov A, Hristov H, et al. Early experience with a temporary bridging device (Comaneci) in the endovascular treatment of ruptured wide neck aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 2018; 10: 978–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sirakov S, Sirakov A, Bhogal P, et al. The p64 flow diverter-mid-term and long-term results from a single center. Clin Neuroradiol. Epub ahead of print 9 August 2019. DOI: 10.1007/s00062-019-00823-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Möhlenbruch M, Herweh C, Behrens L, et al. The LVIS Jr. microstent to assist coil embolization of wide-neck intracranial aneurysms: clinical study to assess safety and efficacy. Neuroradiology 2014; 56: 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho YD, Sohn C-H, Kang H-S, et al. Coil embolization of intracranial saccular aneurysms using the Low-profile Visualized Intraluminal Support (LVIS™) device. Neuroradiology 2014; 56: 543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behme D, Weber A, Kowoll A, et al. Low-profile Visualized Intraluminal Support device (LVIS Jr) as a novel tool in the treatment of wide-necked intracranial aneurysms: initial experience in 32 cases. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baek JW, Jin S-C, Kim JH, et al. Initial multicentre experience using the neuroform atlas stent for the treatment of un-ruptured saccular cerebral aneurysms. Br J Neurosurg 2020; 34: 333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jankowitz BT, Hanel R, Jadhav AP, et al. Neuroform Atlas Stent System for the treatment of intracranial aneurysm: primary results of the Atlas Humanitarian Device Exemption cohort. J Neurointerv Surg 2019; 11: 801–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ten Brinck MFM, de Vries J, Bartels RHMA, et al. NeuroForm Atlas stent-assisted coiling: preliminary results. Neurosurgery 2019; 84: 179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mühl-Benninghaus R, Abboud R, Ding A, et al. Preclinical evaluation of the Accero stent: flow remodelling effect on aneurysm, vessel reaction and side branch patency. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2019; 42: 1786–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schob S, Hoffmann K-T, Richter C, et al. Flow diversion beyond the circle of Willis: endovascular aneurysm treatment in peripheral cerebral arteries employing a novel low-profile flow diverting stent. J Neurointerv Surg 2019; 11: 1227–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martínez-Galdámez M, Biondi A, Kalousek V, et al. Periprocedural safety and technical outcomes of the new Silk Vista Baby flow diverter for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: results from a multicenter experience. J Neurointerv Surg 2019; 11: 723–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhogal P, Wong K, Uff C, et al. The Silk Vista Baby: initial experience and report of two cases. Interv Neuroradiol 2019; 25: 530–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhogal P, Bleise C, Chudyk J, et al. The p48_HPC antithrombogenic flow diverter: initial human experience using single antiplatelet therapy. J Int Med Res 2020; 48: 300060519879580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhogal P, Bleise C, Chudyk J, et al. The p48MW flow diverter-initial human experience. Clin Neuroradiol. Epub ahead of print 21 August 2019. DOI: 10.1007/s00062-019-00827-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cagnazzo F, Limbucci N, Nappini S, et al. Y-Stent-assisted coiling of wide-neck bifurcation intracranial aneurysms: a meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2019; 40: 122–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makalanda H, Wong K, Bhogal P. Flow-T stenting with the Silk Vista Baby and Baby Leo stents for bifurcation aneurysms – a novel endovascular technique. Interv Neuroradiol 2020; 26: 68–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heiferman DM, Reynolds MR, Reddy AS, et al. Railroad switch' technique for stent-assisted coil embolization of a wide-neck bifurcation intracranial aneurysm: technical note. Neuroradiol J. Epub ahead of print 29 April 2020. DOI: 10.1177/1971400920919688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yub Lee S, Won Youn S, Kyun Kim H, et al. Inadvertent detachment of a retrievable intracranial stent: review of manufacturer and user facility device experience. Neuroradiol J 2015; 28: 172–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alghamdi F, Mine B, Morais R, et al. Stent-assisted coiling of intracranial aneurysms located on small vessels: midterm results with the LVIS Junior stent in 40 patients with 43 aneurysms. Neuroradiology 2016; 58: 665–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng Z, Zhang L, Li Q, et al. Endovascular treatment of wide-neck anterior communicating artery aneurysms using the LVIS Junior stent. J Clin Neurosci 2015; 22: 1288–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiorella D, Boulos A, Turk AS, et al. The safety and effectiveness of the LVIS stent system for the treatment of wide-necked cerebral aneurysms: final results of the pivotal US LVIS trial. J Neurointerv Surg 2019; 11: 357–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iosif C, Biondi A. Braided stents and their impact in intracranial aneurysm treatment for distal locations: from flow diverters to low profile stents. Expert Rev Med Devices 2019; 16: 237–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shankar JJS, Quateen A, Weill A, et al. Canadian Registry of LVIS Jr for Treatment of Intracranial Aneurysms (CaRLA). J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: 849–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim SS, Park H, Lee KH, et al. Utility of low-profile visualized intraluminal support junior stent as a rescue therapy for treating ruptured intracranial aneurysms during complicated coil embolization. World Neurosurg 2020; 135: e710–e715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grossberg JA, Hanel RA, Dabus G, et al. Treatment of wide-necked aneurysms with the Low-profile Visualized Intraluminal Support (LVIS Jr) device: a multicenter experience. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: 1098–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santillan A, Boddu S, Schwarz J, et al. LVIS Jr. stent for treatment of intracranial aneurysms with parent vessel diameter of 2.5 mm or less. Interv Neuroradiol 2018; 24: 246–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pardo MI, Pumar JM, Blanco M, et al. Medium-term results using the LEO self-expanding stent in the treatment of complex intracranial aneurysms. Neuroradiol J 2008; 21: 704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]