Abstract

A 69-year-old female presented with subacute onset ascending weakness and paraesthesias. She was initially diagnosed with Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) based on her clinical presentation and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showing albuminocytological dissociation. However, she was later found to have anti-neuronal nuclear antibody 1 (ANNA-1/anti-Hu)-positive CSF and was subsequently diagnosed with small-cell lung cancer. Her neurological symptoms were ultimately attributed to ANNA-1/anti-Hu-associated paraneoplastic polyneuropathy. During the course of her evaluation, she had magnetic resonance imaging findings of dorsal predominant cauda equina nerve root enhancement, which has not been previously described. The only previously reported case of cauda equina enhancement due to ANNA-1-associated polyneuropathy described ventral predominant findings. The distinction between ventral and dorsal enhancement is important, since it suggests that different patterns of nerve root involvement may be associated with this paraneoplastic syndrome. Therefore, ANNA-1-associated paraneoplastic inflammatory polyneuropathy can be considered in the differential diagnosis of cauda equina nerve root enhancement with ventral and/or dorsal predominance. This can potentially be helpful in differentiating ANNA-1 polyneuropathy from GBS, which classically has ventral predominant enhancement.

Keywords: Paraneoplastic polyneuropathy, ANNA-1, anti-Hu, cauda equina enhancement

Introduction

Paraneoplastic syndromes are manifestations of systemic reactions to neoplasms, often mediated by immunological mechanisms. Common paraneoplastic neurological syndromes include limbic encephalitis, encephalomyelitis, paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration, brainstem encephalitis and paraneoplastic sensory neuropathy (PSN).1 PSN is associated with lung cancer in up to 80% of cases, with the most common subtype being small-cell lung cancer. However, PSN may also occur with various adenocarcinomas, thymoma and lymphoma.2 PSN is associated with several paraneoplastic antibodies, including anti-neuronal nuclear antibody 1 (anti-Hu/ANNA-1), anti-CRMP5 and anti-amphiphysin.

Symptoms of PSN include pain, paraesthesias, ataxia and loss of deep sensation in the extremities. These typically progress over a period of weeks to months before presentation. In the majority of cases, paraneoplastic polyneuropathies are pure sensory syndromes, with motor and sensorimotor syndromes being far less common.3,4 For example, in one study of 200 patients with anti-Hu-associated paraneoplastic syndromes, only 4% of patients had a sensorimotor neuropathy with prominent motor features.5 Reports of ANNA-1-associated sensorimotor neuropathy are rare. Most reported patients have no abnormal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings. Therefore, examples of MRI abnormalities in ANNA-1 polyneuropathy are exceedingly rare. To our knowledge, only one previous report has shown cauda equina imaging abnormalities on spine MRI corroborating the diagnosis.6 This prior patient had ventral predominant cauda equina enhancement. It can be difficult to consider this entity when cauda equina enhancement is seen on MRI due to the paucity of knowledge regarding imaging findings. We report the first patient diagnosed with ANNA-1-associated sensorimotor polyneuropathy with lumbar spine MRI showing dorsal predominant enhancement of the cauda equina nerve roots.

Patient presentation and work-up

A 69-year-old female presented with ascending weakness and bilateral paraesthesias that had rapidly progressed over two weeks. Her exam was remarkable for weakness in all four extremities with a proximal predominance. She was also noted to have labile blood pressures, possibly due to autonomic dysregulation. MRI of the head, cervical spine and thoracic spine were normal. Lumbar puncture demonstrated elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein with albuminocytological dissociation. This led to a presumptive diagnosis of Guillain–Barré Syndrome (GBS), and she was started on intravenous immunoglobulin G (IVIg).

Subsequent electromyography failed to show evidence of demyelination – a non-specific finding that is often seen in GBS. Moreover, she did not clinically improve with IVIg treatment. MRI of the lumbar spine showed abnormal enhancement predominately involving dorsal cauda equina nerve roots (Figures 1 and 2). This was felt to be somewhat atypical for GBS, which classically involves ventral nerve roots, but the overall clinical presentation remained consistent with GBS.

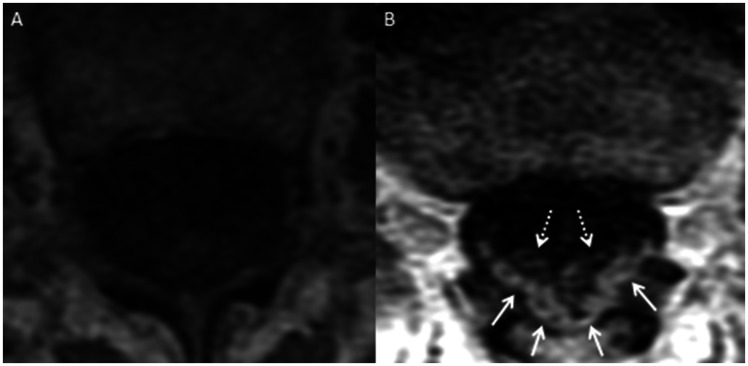

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine in a 69-year-old female with paraneoplastic polyneuropathy. Sagittal T1-weighted (T1W) pre-contrast (a) and post-contrast (b) images show smooth enhancement of the dorsal cauda equina nerve roots (b, solid arrows). There is no appreciable enhancement of the ventral nerve roots (b, dashed arrows).

Figure 2.

MRI of the lumbar spine in a 69-year-old female with paraneoplastic polyneuropathy. Axial T1W pre-contrast (a) and post-contrast (b) images show enhancement of the dorsal cauda equina nerve roots (b, solid arrows). There is substantially less, if any, enhancement of the ventral cauda equina nerve roots (b, dashed arrows).

CSF testing returned positive for ANNA-1, raising concern for an underlying malignancy. A positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan was obtained, which showed a hypermetabolic pulmonary nodule and hypermetabolic mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Figure 3). Biopsy of the mediastinal node revealed small-cell carcinoma. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with ANNA-1-associated paraneoplastic polyneuropathy with mixed sensory and motor features. She was treated with chemotherapy and radiation, as well as multiple short courses of corticosteroids and plasma exchange for her paraneoplastic syndrome. She had significant improvement in her symptoms on follow-up several months later, with mild residual weakness and paraesthesias.

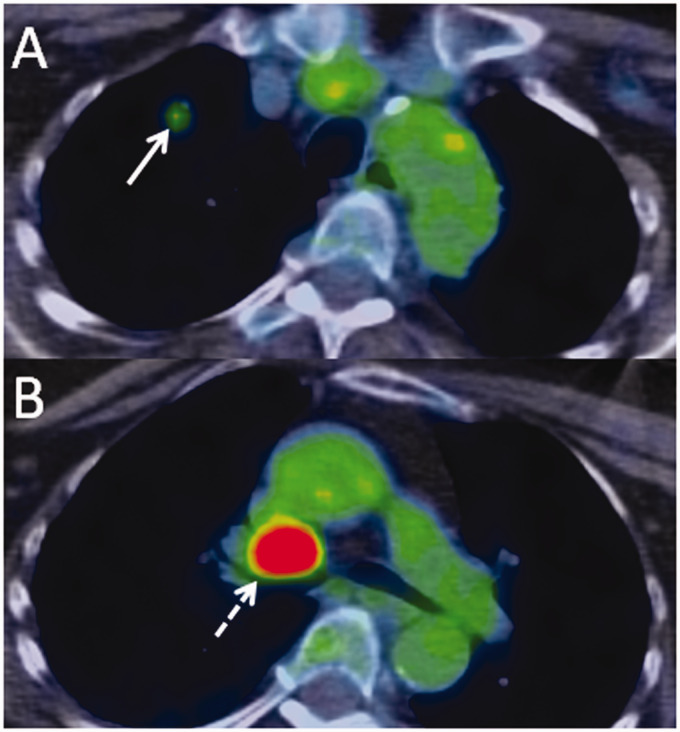

Figure 3.

F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography performed in a 69-year-old female with paraneoplastic polyneuropathy. Axial fusion images through the upper chest (a) and central mediastinum (b) show a small hypermetabolic pulmonary nodule (a, arrow) and a large hypermetabolic mediastinal lymph node (b, dashed arrow).

Discussion

Anti-Hu/ANNA-1 is associated with a variety of neurological syndromes, including limbic encephalitis, encephalomyelitis and polyneuropathies such as PSN. ANNA-1-associated polyneuropathy is usually a sensory predominant syndrome, with relatively few known examples of motor or sensorimotor syndromes. Our patient’s presentation was therefore quite unique, even within the subset of rare ANNA-1-associated polyneuropathies, because she presented with both motor and sensory symptoms. The temporal evolution of ANNA-1-associated polyneuropathy is quite variable. For instance, one recent patient with ANNA-1-associated paraneoplastic motor neuropathy presented with acute onset tetraplegia.7 Others, such as our patient, present with progressive symptoms over weeks or months.

Because motor and sensorimotor paraneoplastic polyneuropathies are far less common than their sensory predominant counterparts, they may be subject to early misdiagnosis. This is exemplified by our patient’s work-up. She was initially diagnosed with GBS due to a clinical presentation largely characterised by motor symptoms and motor deficits on exam. Also, her findings of CSF albuminocytological dissociation were initially felt to corroborate a diagnosis of GBS, though this finding is relatively non-specific and can be seen with various inflammatory aetiologies.8 Our patient’s experience was therefore instructive in showing that paraneoplastic polyneuropathy may overlap clinically with GBS, with regard to both symptomatology and lab findings. A similar initial misdiagnosis of GBS in a patient with ANNA-1-associated sensorimotor neuropathy has been previously reported, though this patient also had brain MRI findings of limbic encephalitis that suggested a paraneoplastic aetiology.9 Correlation with any antecedent infection versus any evidence of malignancy can be helpful in differentiating GBS from a paraneoplastic syndrome.

Our patient is also unique with regard to her imaging findings. Although cauda equina enhancement has been previously described in an ANNA-1-associated paraneoplastic polyneuropathy, dorsal predominant cauda equina nerve root enhancement is a novel finding. To our knowledge, only one previous patient with ANNA-1-associated polyneuropathy exhibiting abnormal MRI findings has been reported. This prior patient’s MRI demonstrated a ventral predilection of cauda equina enhancement.6 Three other previous reports of presumed paraneoplastic polyneuropathy demonstrated cauda equina imaging abnormalities in the setting of malignancy, though no autoantibody marker was found (Table 1). These include two reports of diffuse enlargement and enhancement of the cauda equina nerve roots in patients with lymphoma and breast cancer, respectively, resulting in both sensory and motor deficits.10–12 A third previously reported patient with Hodgkin lymphoma had nerve root enlargement and enhancement restricted to the ventral roots, resulting in a pure motor neuropathy.11 While it is difficult to derive significance from this small sample of reported positive MRI findings in patients with paraneoplastic polyneuropathy, these prior patients show that the pattern of cauda equina enhancement can correlate with the associated clinical syndrome. Our patient’s dorsal predominant imaging findings did not precisely correlate with her combined motor and sensory symptoms. Thus, this is also the first example of MRI findings in paraneoplastic polyneuropathy that were discordant with the clinical scenario.

Table 1.

Summary of previously reported paraneoplastic sensorimotor polyneuropathies with spinal MRI imaging findings.

| Authors/year | Patient characteristics | Paraneoplastic antibody | Clinical presentation | Reported imaging findings | Clinical follow-up of neurological symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kumar and Dyck (2005) | 60-year-old female with lymphoma | None isolated | Leg weakness, heaviness, numbness | Diffuse cauda equina enlargement and enhancement | Initial improvement with IVIg |

| Nomiyama et al. (2007) | 56-year-old female with breast cancer | None isolated | Gait disturbance | Diffuse cauda equina enlargement and enhancement | Unknown |

| Flanagan et al. (2012) | 31-year-old female with lymphoma | None isolated | Left>right limb weakness without sensory symptoms | Ventral predominant cauda equina enlargement and enhancement | Improvement over five years after short-term IVIg, corticosteroids and treatment of lymphoma |

| Shibata et al. (2015) | 64-year-old female with small-cell lung cancer | ANNA-1/anti-Hu | Numbness and weakness in the lower extremities | Ventral predominant cauda equina enhancement | Initial improvement with IVIg |

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; ANNA-1: anti-neuronal nuclear antibody 1; IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulin G.

Indications for imaging patients with suspected paraneoplastic polyneuropathy are not well established due to the rarity of this entity. In our experience, imaging is often performed before any definite paraneoplastic syndrome is diagnosed. Therefore, it is important to be aware of the spectrum of imaging findings that can be seen in paraneoplastic polyneuropathy and how this affects the differential diagnosis. For example, the enhancement pattern may be helpful in assessing the likelihood of other differential considerations. In our patient’s case, the finding of dorsal predominant cauda equina enhancement would be considered atypical for GBS, which can have variable findings but classically has ventral predominant enhancement. Additionally, since paraneoplastic polyneuropathy can present with cauda equina thickening, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy could also be considered, although enhancement would generally suggest a more acute syndrome. Since paraneoplastic polyneuropathy can coexist with other syndromes such as limbic encephalitis, brain imaging should also be considered in appropriate clinical circumstances.

Treatment options for paraneoplastic neuropathy, in addition to treatment of the underlying malignancy, include corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, IVIg and plasmapheresis.1 Our patient did show significant symptomatic improvement with steroids and plasma exchange, although her symptoms were refractory to IVIg.

Conclusion

We present a patient with ANNA-1-associated paraneoplastic polyneuropathy who was initially misdiagnosed with GBS, having presented with rapidly ascending weakness, paraesthesias and CSF albuminocytological dissociation. To our knowledge, this is only the second reported patient showing positive MRI findings in the setting of ANNA-1-associated polyneuropathy. Additionally, this is the first example of MRI in any type of paraneoplastic polyneuropathy showing dorsal predominant enhancement of the cauda equina nerve roots. This finding is important, since it suggests that different patterns of nerve root involvement may be associated with paraneoplastic syndromes, including ANNA-1-associated polyneuropathy. Our patient’s presentation and imaging findings illustrate multiple learning points. First, ANNA-1 polyneuropathy can clinically mimic GBS. Second, the main imaging finding of this entity is cauda equina enhancement, though nerve enlargement can also be seen as demonstrated by prior patients. Lastly, ANNA-1-associated paraneoplastic polyneuropathy can be considered in the differential diagnosis of cauda equina nerve root enhancement with either ventral or dorsal predominance. This was not previously recognised and contributes to the understanding of imaging findings in this rare entity.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, NEU919689 Supplemental Material for Dorsal cauda equina nerve root enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging due to ANNA-1-associated paraneoplastic polyneuropathy by Ajay A Madhavan, Julie B Guerin, Laurence J Eckel, Vance T Lehman and Carrie M Carr in The Neuroradiology Journal

Acknowledgements

This paper was previously presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Spine Radiology, 20–24 February 2019, Miami, Florida.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Ajay A Madhavan https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1794-4502

References

- 1.Pelosof LC, Gerber DE. Paraneoplastic syndromes: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85: 838–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoftberger R, Rosenfeld MR, Dalmau J. Update on neurological paraneoplastic syndromes. Curr Opin Oncol 2015; 27: 489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graus F, Santamaria J, Obach J, et al. Sensory neuropathy as remote effect of cancer. Neurology 1987; 37: 1266–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graus F, Elkon KB, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. Pure sensory neuropathy. Restriction of the Hu antibody to the sensory neuropathy associated with small cell carcinoma of the lung. Neurologia 1986; 1: 11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graus F, Keime-Guibert F, Reñe R, et al. Anti-Hu-associated paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis: analysis of 200 patients. Brain 2001; 124: 1138–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibata M, Uchida M, Tsukagoshi S, et al. Anti-Hu antibody-associated paraneoplastic neurological syndrome showing peripheral neuropathy and atypical multifocal brain lesions. Intern Med 2015; 54: 3057–3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheli M, Dinoto A, Ridolfi M, et al. Motor neuron disease as a treatment responsive paraneoplastic neurological syndrome in patient with small cell lung cancer, anti-Hu antibodies and limbic encephalitis. J Neurol Sci 2019; 400: 158–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks JA, McCudden C, Breiner A, et al. Causes of albuminocytological dissociation and the impact of age-adjusted cerebrospinal fluid protein reference intervals: a retrospective chart review of 2627 samples collected at tertiary care centre. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e025348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakurai T, Wakida K, Kimura A, et al. [Anti-Hu antibody-positive paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis with acute motor sensory neuropathy resembling Guillain–Barré syndrome: a case study]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2015; 55: 921–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar N, Dyck PJ. Hypertrophy of the nerve roots of the cauda equina as a paraneoplastic manifestation of lymphoma. Arch Neurol 2005; 62: 1776–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flanagan EP, Sandroni P, Pittock SJ, et al. Paraneoplastic lower motor neuronopathy associated with Hodgkin lymphoma. Muscle Nerve 2012; 46: 823–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nomiyama K, Uchino A, Yakushiji Y, et al. Diffuse cranial nerve and cauda equina lesions associated with breast cancer. Clin Imaging 2007; 31: 202–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, NEU919689 Supplemental Material for Dorsal cauda equina nerve root enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging due to ANNA-1-associated paraneoplastic polyneuropathy by Ajay A Madhavan, Julie B Guerin, Laurence J Eckel, Vance T Lehman and Carrie M Carr in The Neuroradiology Journal