Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To examine the associations of APOE ε2ε4 with the development of Alzheimerʼs disease (AD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in non-Latino whites.

DESIGN:

Prospective longitudinal cohort study.

SETTING:

Uniform Data Set from the National Alzheimerʼs Coordinating Center (NACC) between 2005 and August 2018 (data freeze in September 2018).

PARTICIPANTS:

Participants who were non-Latino white, had an APOE genotype available, first visit with dementia free for AD cohort and both dementia and MCI free for MCI cohort, and had a minimum of one follow-up visit (n = 11 871 for AD cohort, and n = 8305 for MCI cohort).

MEASUREMENTS:

The incidences of AD and MCI were determined based on consensus meetings at each Alzheimerʼs disease center. We used NACC-derived variables to define individuals experiencing incidents of AD and MCI at the initial visit as well as the follow-up visits.

RESULTS:

Among participants in the AD cohort (N = 11 871), ε2ε4 accounted for 2.5%, ε2ε2 accounted for 0.4%, ε2ε3 accounted for 11.0%, ε4ε4 accounted for 4.4%, ε3ε4 accounted for 27.3%, and ε3ε3 accounted for 54.4%. Over an average of 4.6 years follow-up, 1857 (15.6%) developed AD dementia, with the range from 6.0% to 35.2% across the six groups. Compared to ε3ε3 carriers, ε2ε4 carriers exhibited an increased risk of incident AD (18.4% vs 11.7%; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 1.74; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.32–2.30; P < .0001). Among participants in the MCI cohort (N = 8305), the average follow-up was 4.7 years, and 1912 (23.0%) developed MCI, with the range from 20.4% to 33.9% across the six groups. Compared to ε3ε3 carriers, ε2ε4 carriers exhibited an increased risk of incident MCI (27.5% vs 21.5%; aHR = 1.52; 95% CI = 1.15–1.99; P = .003).

CONCLUSIONS:

The APOE ε2ε4 genotype is associated with the increased risk of AD and MCI in non-Latino whites.

Keywords: Alzheimerʼs disease, APOE ε2ε4 genotype, mild cognitive impairment

Alzheimerʼs disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative, progressive, and irreversible brain disease; and it is the most common type of dementia. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) polymorphic alleles are the main genetic determinants of AD.1 The three common alleles are ε2, ε3, and ε4.2 APOE ε3, the most common allele, is believed to play a neutral role in the disease (ie, neither decreasing nor increasing risk). In contrast, APOE ε4 is the strongest genetic factor to increase the risk of AD and lowers the age of onset, and APOE ε2 is the least common allele and actually may provide some protection to reduce the risk of the disease. Several studies have shown that ε4 carriers (ie, ε4ε4 or ε3ε4) are associated with the significant increased risk of AD with a dose-dependent effect.3–7 Conversely, ε2 carriers (ie, ε2ε2 or ε2ε3) are associated with a decreased risk of AD dementia.8 Nonetheless, the effect of ε2ε4, which comprises of a “toxic” copy of ε4 and a “protective” copy of ε2, on the risk of AD dementia remains unclear.

Published studies on this topic often either exclude the small number of individuals with APOE ε2ε4 genotype from the analyses to maintain mutually exclusive groups or ignore this variant in the analyses due to the typically small sample size of participants with ε2ε4 genotype.9–11 In a recent study by Oveisgharan et al,12 they examined the association of the APOE ε2ε4 genotype with the incident AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in a sample of community-dwelling older adults and found that ε2ε4 genotype is associated with the risk of MCI, but not AD. One major limitation of this study is the small sample size of the ε2ε4 group (n = 46). Though larger than any previous publications, the analysis may still have been underpowered to detect additional associations. As such, for our study, we took advantage of the Uniform Data Set (UDS), an established prospective cohort of a large, multisite, longitudinal aging and dementia data set provided by the National Alzheimerʼs Coordinating Center (NACC). Implemented by the NACC in 2005, the UDS follows a standard data collection protocol and comprises clinical, neurological, and neuropsychological results and medical history collected from 39 Alzheimerʼs disease centers (ADCs) across the United States since 2005. The resultant information provided by 38 836 subjects (at the time that we received our data) recruited from those ADCs has provided the unique opportunity to study dementia among the US population. The purpose of this study was to examine the associations of APOE ε2ε4 with the development of AD dementia and MCI among the older adult population using the UDS provided by NACC.

METHODS

Setting and Study Participants

The NACC was established by the National Institute on Aging (NIA; U01 AG016976) in 1999 to facilitate collaborative research and record the cumulative enrollment of the NIA-funded ADCs. In 2005, NACC implemented the UDS using a standardized clinical evaluation administered during approximately annual visits. The participants (ie, exhibiting normal cognition, MCI, and dementia) undergo a complete examination approximately yearly, which yields demographic data, neuropsychological testing scores, and clinical diagnoses. The UDS database comprises not only referral cases and normal controls, but also well-defined phenotypes, genetic information, and long follow-up, which generally are absent in epidemiological studies. For this study, we used data from 38 836 subjects with visiting spanning from September 2005 to August 2018 (data freeze in September 2018). All contributing ADCs are required to obtain informed consent from their participants and maintain their own Institutional Review Board review and approval from their institutions prior to submitting data to NACC.

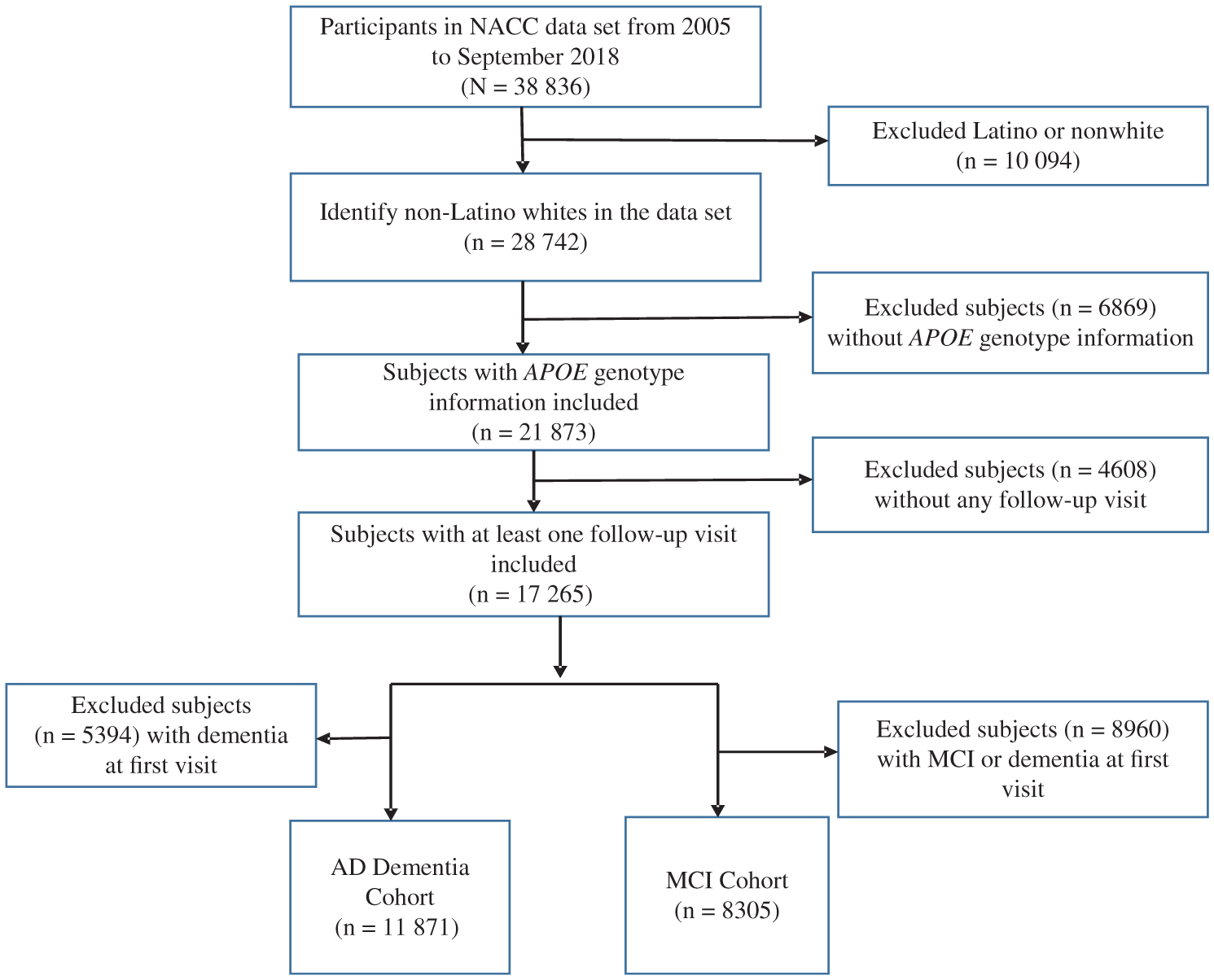

Given that previous studies have shown differential associations between APOE genotype and AD risks among different ethnic groups,8 we restricted our analysis to participants who were non-Latino white. In addition, we restricted our analysis to participants who had an APOE genotype available, first visit with dementia free for AD cohort and both dementia and MCI free for MCI cohort, and attended a minimum of one follow-up visit. These filter criteria resulted in two cohorts for analysis: an AD cohort (N = 11 871) and an MCI cohort (N = 8305) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram displaying derivation of study sample for the analyses with source of exclusion. AD indicates Alzheimerʼs disease; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NACC, National Alzheimerʼs Coordinating Center.

Our primary outcome was the time in years until the first diagnosis of AD dementia for the AD cohort and until the first diagnosis of MCI for the MCI cohort. Participants were followed up to their last visit until September 2018. Because only a small number of observations were available beyond the 10 years of follow-up, data were censored at a maximum 10 years of follow-up, the first time of incident event, or death—whichever came first.

Diagnosis of AD and MCI

The incidence of AD and MCI were determined based on consensus meetings at each ADC. We used NACC-derived variables to define individuals experiencing incidents of AD and MCI at the initial visit as well as the follow-up visits. MCI was defined based on the NACC-derived variable of cognitive status at UDS visit (normal cognition, impaired but not MCI, MCI, and dementia). AD was defined based on the combination of two NACC-derived variables of cognitive status at UDS visit and primary etiologic diagnosis.

APOE Genotype

The participants were classified into six groups, based on APOE genotyping: ε2ε4, ε2ε2, ε2ε3, ε4ε4, ε3ε4, with ε3ε3 carriers serving as the reference group.

Other Characteristics

The sex and age at initial visit were recorded in the NACC data set. The education level of participants was assessed as the total number of years of schooling. We regrouped year of initial visit into three categories, according to the distribution of baseline visit each year: between years 2005 and 2007, between years 2008 and 2012, and between years 2013 and 2017.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (ie, mean and SD for continuous variables; frequency and percentage for categorical variables) for baseline characteristics at their initial visit, which comprised age, sex, education level, and year of initial visit, were calculated (1) separately for the AD cohort and MCI cohort and (2) overall and by the six APOE genotype subgroups. One-way analysis of variance and χ2 tests were used to compare group differences across the six APOE groups (Supplementary Table S1).

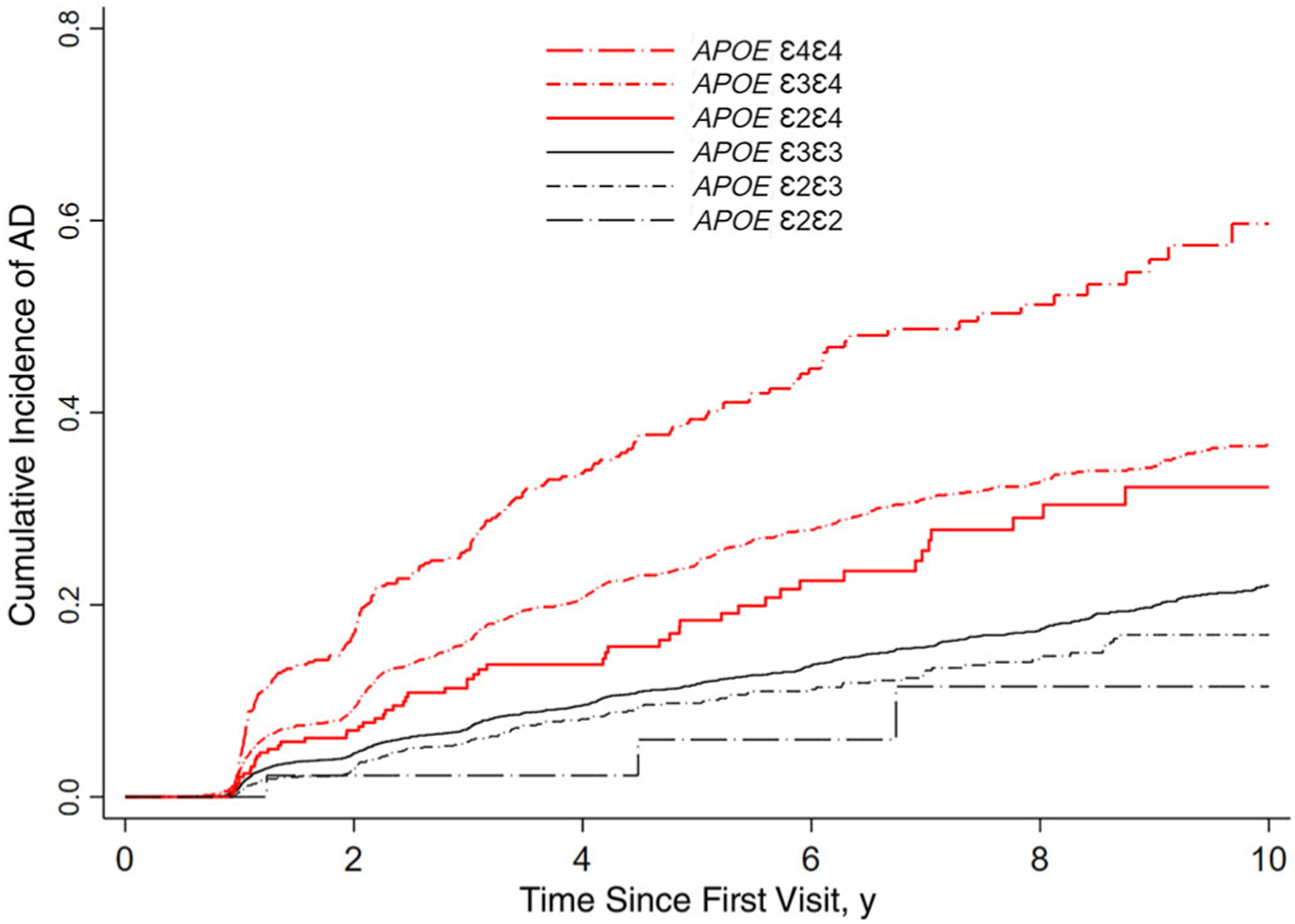

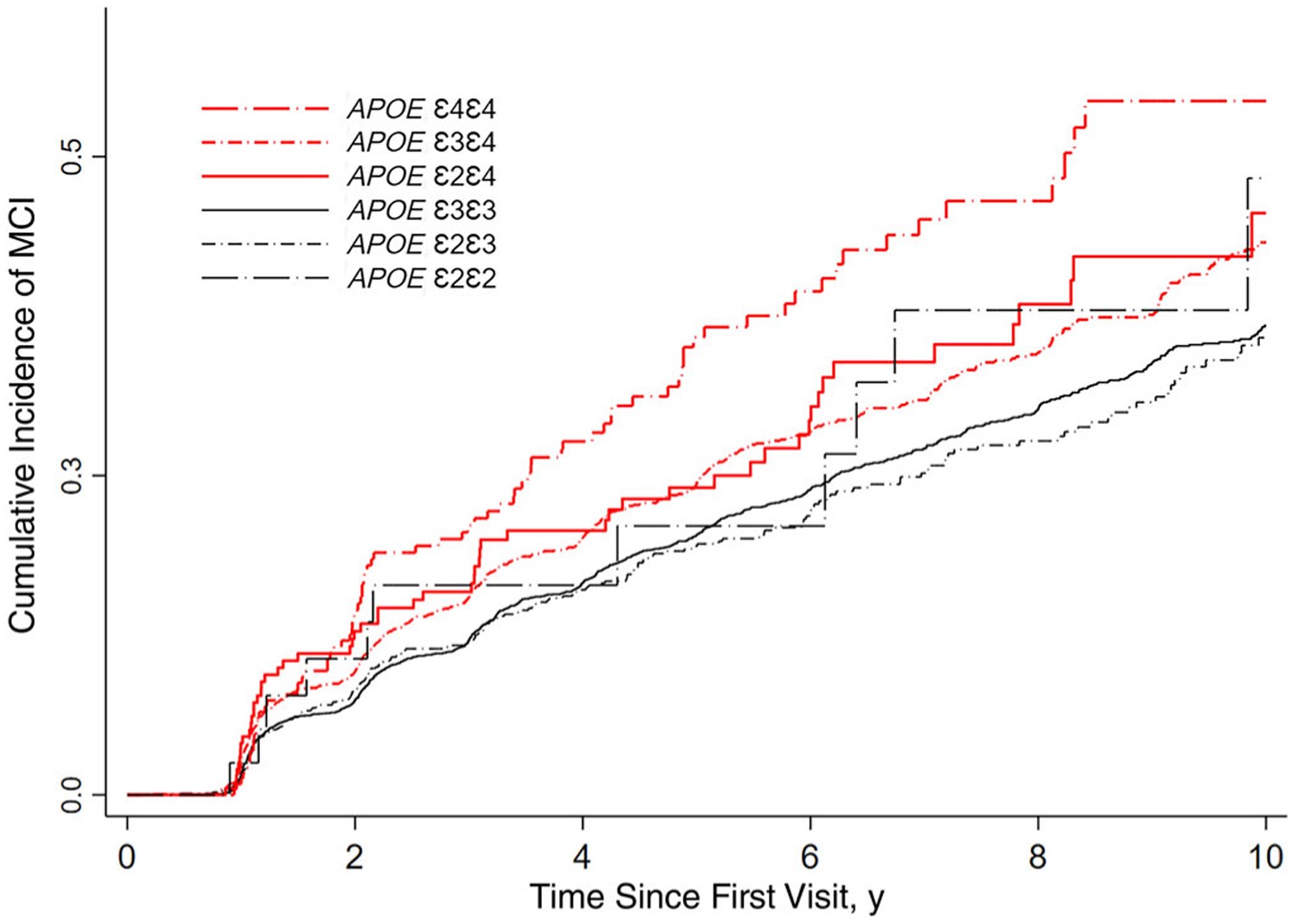

We depicted the cumulative incidence rate of AD and MCI by APOE genotype in Figures 2 and 3. In addition, the 5- and 10-year incidence rates were summarized in Table 1. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the association between APOE genotype and the risk of AD dementia in both an unadjusted and adjusted model, controlling for age, sex, education, baseline cognitive status (ie, normal, impaired but not MCI, and MCI), and year of initial visit. The same approach was used to estimate the association between APOE genotype with the incidence of MCI among participants who did not present with cognitive impairment during the initial visit. Participants with no incident event or death were right censored at the last evaluation or a maximum of 10 years of follow up. The proportional hazard assumption was tested based on the smoothed plots of the scaled Schoenfeld residuals. The unadjusted and multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported to measure the strength of risk across different APOE genotype groups (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia during 10 years of follow-up among participants with APOE ε2ε4 genotype compared with other APOE genotype groups.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) during 10 years of follow-up among participants with APOE ε2ε4 genotype compared with other APOE genotype groups.

Table 1.

The Cumulative Incidence Rate at 5 and 10 Years

| AD Cohort (N = 11 871) | MCI Cohort (N = 8305) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 5 y | 10 y | 5 y | 10 y |

| Overall | 0.16 (0.16–0.17) | 0.27 (0.26–0.29) | 0.22 (0.21–0.23) | 0.39 (0.37–0.41) |

| ε3ε3 | 0.12 (0.11–0.13) | 0.22 (0.2–0.24) | 0.20 (0.19–0.22) | 0.37 (0.35–0.39) |

| ε3ε4 | 0.24 (0.23–0.26) | 0.37 (0.34–0.39) | 0.24 (0.22–0.27) | 0.43 (0.40–0.47) |

| ε2ε3 | 0.10 (0.08–0.12) | 0.17 (0.14–0.2) | 0.19 (0.17–0.23) | 0.36 (0.31–0.41) |

| ε4ε4 | 0.39 (0.34–0.45) | 0.60 (0.52–0.68) | 0.36 (0.29–0.44) | 0.54 (0.45–0.65) |

| ε2ε4 | 0.18 (0.14–0.24) | 0.32 (0.25–0.41) | 0.24 (0.18–0.32) | 0.46 (0.35–0.58) |

| ε2ε2 | 0.06 (0.01–0.23) | 0.12 (0.04–0.34) | 0.21 (0.10–0.40) | 0.48 (0.27–0.75) |

Note: Data are given as incidence rate (95% confidence interval). Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Table 2.

The HR of APOE Genotype From Cox Proportional Hazards Model

| AD Cohort (N = 11 871) | MCI Cohort (N = 8305) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Modela | Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Modela | |||||

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

| ε3ε3 (Reference group) | ||||||||

| ε3ε4 | 2.11 (1.9–2.33) | <.0001 | 2.1 (1.89–2.33) | <.0001 | 1.24 (1.11–1.37) | <.0001 | 1.41 (1.27–1.57) | <.0001 |

| ε2ε3 | 0.78 (0.65–0.95) | .013 | 0.82 (0.67–0.99) | .041 | 0.95 (0.82–1.11) | .511 | 0.9 (0.77–1.05) | .181 |

| ε4ε4 | 3.88 (3.3–4.55) | <.0001 | 3.57 (3.03–4.22) | <.0001 | 1.8 (1.43–2.25) | <.0001 | 2.53 (2.01–3.18) | <.0001 |

| ε2ε4 | 1.64 (1.24–2.16) | <.0001 | 1.74 (1.32–2.3) | <.0001 | 1.35 (1.03–1.77) | .032 | 1.52 (1.15–1.99) | .003 |

| ε2ε2 | 0.47 (0.15–1.45) | .186 | 0.45 (0.14–1.39) | .164 | 1.29 (0.71–2.33) | .403 | 1.19 (0.65–2.15) | .576 |

| ε2ε4 comparing to other genotype as reference group | ||||||||

| ε2ε4 vs ε3ε4 | 0.78 (0.59–1.02) | .074 | 0.83 (0.63–1.09) | .187 | 1.09 (0.83–1.44) | .547 | 1.07 (0.81–1.42) | .620 |

| ε2ε4 vs ε4ε4 | 0.42 (0.31–0.57) | <.0001 | 0.49 (0.36–0.66) | <.0001 | 0.75 (0.53–1.06) | .100 | 0.60 (0.42–0.84) | .003 |

| ε2ε4 vs ε2ε3 | 2.09 (1.52–2.88) | <.0001 | 2.13 (1.54–2.94) | <.0001 | 1.42 (1.05–1.91) | .022 | 1.68 (1.25–2.27) | .001 |

| ε2ε4 vs ε2ε2 | 3.52 (1.10–11.3) | .034 | 3.90 (1.22–12.5) | .022 | 1.05 (0.55–2.00) | .894 | 1.28 (0.67–2.44) | .457 |

Note: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; HR, hazard ratio; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Models were adjusted for age, sex, education, baseline cognitive status, and year of initial visit.

Because our primary interest was ε2ε4 carriers compared to the reference group ε3ε3 carriers, the statistical significance α level was fixed at .05. In eight sets of post hoc comparisons that involved multiple groups (ie, four sets of comparisons between the various genotypes and reference group ε3ε3 [eg, ε3ε4 vs ε3ε3, ε2ε3 vs ε3ε3, ε4ε4 vs ε3ε3, ε2ε2 vs ε3ε3] and four sets of comparisons between ε2ε4 and other APOE genotypes [eg, ε2ε4 vs ε2ε3, ε2ε4 vs ε4ε4, ε2ε4 vs ε2ε2, ε2ε4 vs ε3ε4]), the statistical significance α level was fixed at .05/8 = .00625 to account for multiple testing.

The protocol of the UDS data set requires that follow-up visit data are collected from participants on an approximately annual basis. However, our analysis of the UDS data revealed that follow-up visit time actually varied considerably across participants. Therefore, our primary analysis strategy treated this visit time as a continuous time variable, and we used Cox proportional hazards models as our main statistical approach. Moreover, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with discrete-time survival models using the visit number as a discrete time variable to assess the robustness of our model estimates. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and STATA version 15 (StataCorp).

RESULTS

The demographic characteristics of the individuals included in our analyses were summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Participants in the AD cohort (N = 11 871) were, on average, 72 years of age at their initial visit, 56% female, and possessed an average of 16 years of education; moreover, 30% had been diagnosed with MCI at baseline, and 45% were recruited between 2005 and 2007. The demographics for MCI cohort participants were similar: average age of 71 years at baseline visit, over 60% female, and an average 16 years of education; moreover, 46% had been recruited between years 2005 and 2007. There were statistically significant differences across the six APOE genotype groups for age and years of initial visit.

APOE Genotype and Incidence of AD Dementia

Among participants in the AD cohort (N = 11 871), ε2ε4 accounted for 2.5% of the total, with the other alleles representing the following percentage of the total: ε2ε2, 0.4%; ε2ε3, 11.0%; ε4ε4, 4.4%; ε3ε4, 27.3%; and ε3ε3, 54.4%. Over an average of 4.6 years of follow-up, 54 of 294 (18.4%) ε2ε4 developed AD dementia, with the following percentages for the other allele carriers: 758 of 6454 (11.7%) ε3ε3, 737 of 3239 (22.7%) ε3ε4, 120 of 1308 (9.17%) ε2ε3, 185 of 526 (35.2%) ε4ε4, and 3 of 50 (6%) ε2ε2. In total, 1857 (15.6%) participants in the AD cohort developed AD dementia. The overall cumulative incidence rate of AD dementia at 5 and 10 years was 16% and 27%, respectively; and the percentages were as follows for these allele carriers: ε2ε4 (18% and 32%, respectively), ε4ε4 (39% and 60%, respectively), ε3ε4 (24% and 37%, respectively), ε3ε3 (12% and 22%, respectively), ε2ε3 (10% and 17%, respectively), and ε2ε2 (6% and 12%, respectively).

In a Cox proportional hazards model that controlled for age, sex, education, baseline cognitive status, and year of initial visit (Table 2), the point estimate for the risk of AD dementia was statistically significantly higher among ε2ε4 compared to ε3ε3 carriers (aHR = 1.74; 95% CI = 1.32–2.30; P < .0001). Meanwhile, ε3ε4 carriers exhibited a 110% increased risk of incident AD dementia (aHR = 2.10; 95% CI = 1.89–2.33; P < .0001), and ε4ε4 carriers exhibited a 257% increased risk of incident AD dementia (aHR = 3.57; 95% CI = 3.03–4.22; P < .0001) compared to ε3ε3 carriers. In contrast, ε2ε3 carriers exhibited an 18% decreased risk of incident AD dementia (aHR = 0.82; 95% CI = 0.67–0.99; P = .041), and ε2ε2 exhibited a 55% decreased risk of incident AD dementia (aHR = 0.45; 95% CI = 1.14–1.39; P = .164) compared to ε3ε3 carriers; however, these differences were not statistically significant. Additionally, we observed a statistically significant difference in the risk of AD dementia between ε2ε4 and ε2ε3 (aHR = 2.13; 95% CI = 1.54–2.94; P < .0001) and between ε2ε4 and ε4ε4 (aHR = 0.49; 95% CI = 0.36–0.66; P < .0001). However, we did not observe a statistically significant difference in the risk of AD dementia between ε2ε4 and ε2ε2 (aHR = 3.90; 95% CI = 1.22–12.5; P = .022) and between ε2ε4 and ε3ε4 (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.63–1.09; P = .187).

APOE Genotype and Incidence of MCI

Among participants in the MCI cohort (N = 8305), ε2ε4 carriers accounted for 2.41% of the total, and the other allele carriers represented the following percentages: ε3ε3, 7.6%; ε3ε4, 24.8%; ε2ε3, 11.9%; ε4ε4, 2.88%; and ε2ε2, 0.48%. Over an average of 4.7 years of follow-up, 55 of 200 (27.5%) ε2ε4, 1027 of 4780 (21.5%) ε3ε3, 537 of 2060 (26.1%) ε3ε4, 201 of 986 (20.4%) ε2ε3, 81 of 239 (33.9%) ε4ε4, and 11 of 40 (27.5%) ε2ε2 carriers developed MCI. In total, 1912 (23.0%) participants in the MCI cohort developed MCI. The overall cumulative incidence rates of MCI at 5- and 10-year follow-ups were 22% and 39%, respectively; and the percentages were as follows for these allele carriers: ε2ε4 (24% and 46%, respectively), ε4ε4 (36% and 54%, respectively), ε3ε4 (24% and 43%, respectively), ε3ε3 (20% and 37%, respectively), ε2ε3 (19% and 36%, respectively), and ε2ε2 (21% and 48%, respectively).

In a Cox proportional hazards model that controlled for age, sex, education, baseline cognitive status, and years of initial visit (Table 2), the point estimate for the risk of MCI was statistically significantly higher among ε2ε4 compared with ε3ε3 carriers (aHR = 1.52; 95% CI = 1.15–1.57; P < .0001). ε3ε4 carriers exhibited a 41% increased risk of MCI (aHR = 1.41; 95% CI = 1.27–2.33; P < .0001), and ε4ε4 carriers exhibited a 153% increased risk of MCI (aHR = 2.53; 95% CI = 2.01–3.18; P < .0001) compared to ε3ε3 carriers. In contrast, ε2ε3 carriers exhibited a 10% decreased risk of MCI (aHR = 0.90; 95% CI = 0.77–1.05; P = .181), and ε2ε2 exhibited a slightly increased 19% risk of MCI (aHR = 1.19; 95% CI = 0.65–2.15; P = .576), compared to ε3ε3 carriers; however, these differences failed to reach statistical significance.

We also observed a statistically significant difference in the risk of MCI between ε2ε4 and ε2ε3 (aHR = 1.68; 95% CI = 1.25–2.27; P = .001) and between ε2ε4 and ε4ε4 (aHR = 0.60; 95% CI = 0.43–0.84; P = .003). However, we did not observe a statistically significant difference in the risk of MCI between ε2ε4 and ε2ε2 (aHR = 1.28; 95% CI = 0.67–2.44; P = .46) and between ε2ε4 and ε3ε4 (aHR = 1.07; 95% CI = 0.81–1.42; P = .62). Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using discrete-time survival model, which generated similar results as the Cox proportional hazards model (Supplementary Table S2). Regardless of different analytical approach, the results presented herein are robust.

DISCUSSION

Using data from the NACC-provided UDS, which were collected from 39 ADCs across the United States, we identified (1) more than 11 000 individuals in the AD cohort who did not present with dementia at baseline and (2) over 8000 participants in the MCI cohort who did not present with either dementia or MCI at baseline. Overall, we found that APOE ε2ε4 carriers exhibited an increased risk of the incidence of AD and MCI. Not surprisingly, we also found that ε4 carriers (ε3ε4 and ε4ε4) exhibited an increased risk of AD and MCI, compared with ε3ε3 carriers in the reference group. In particular, ε4ε4 carriers exhibited a statistically significant higher risk for AD and MCI compared with ε2ε4 carriers, and ε3ε4 carriers exhibited a similar extent of risk for AD and MCI compared with ε2ε4 carriers. Moreover, ε2 carriers (ie, ε2ε2 and ε3ε2) exhibited a lower risk of MCI and AD dementia compared to ε3ε3 carriers, although this difference did not reach statistical significance. These results suggest that ε4 allele has a much stronger “toxic” effect than the ε2 alleleʼs “protective” effect on the risk of AD and MCI. Therefore, despite the presence of a single copy of the “protective” ε2 allele, adults with the ε2ε4 genotype manifest an increased risk of AD and MCI that is more similar to ε4 than it is to ε2.

Because of the opposite effect of ε4 and ε2 alleles and the rare genotype ε2ε4 in the population, many previous publications have either excluded this variant from the analyses or ignore this variant in the analysis. Few studies have addressed the effect of ε2ε4 on the risk of AD and MCI. For example, a case-control study has reported no association of ε2ε4 with AD dementia; nevertheless, the study included only 18 ε2ε4 carriers.13 A more recent study found that ε2ε4 genotype among older adults is associated with risk of MCI but not AD, and the study included only slightly more ε2ε4 carriers (n = 46).12 Indeed, the small number of individuals carrying ε2ε4 included in these studies may not provide enough statistical power to detect the effect of the ε2ε4 allele. Incorporating a much larger sample size, our study confirmed findings of previous studies that ε2ε4 is associated with the risk of MCI. Furthermore, we found that ε2ε4 is associated with the increased risk of AD, which was not reported in the literature. Compared with previous studies, our study featured a much larger sample size, with 294 ε2ε4 carriers in the AD cohort and 200 ε2ε4 carriers in the MCI cohort.

Given that few studies have previously addressed the clinical association between ε2ε4 genotype with AD and MCI, our methods and results are especially interesting and potentially translatable. As such, we recommend that subsequent research should be conducted to assess whether the ε2ε4 genotype is associated with measures of AD pathology and decline of cognitive function among older adults.

The major strength of the study described herein is its large sample size of the rare ε2ε4 genotype, facilitated by using the UDS data collected at ADCs nationwide and provided by the NACC. Nonetheless, we must acknowledge the potential sampling bias inherent in our study. Indeed, the individuals assessed at ADCs who agree to participate in longitudinal research studies at academic medical centers are unlikely to represent the general population of older adults—even when these participants exhibit normal cognition. In addition, the education level of these participants likely exceeds the population average. These sampling biases may limit generalizability of our findings. Moreover, because our analyses were restricted to non-Latino whites, similar analyses will need to be extended to other racial and ethnic populations in the future. Furthermore, despite careful adjustment for baseline sociodemographic and clinical factors, the potential for unmeasured confounding (eg, comorbidities) of the relationship between ε2ε4 genotype on the AD and MCI is possible, given the observational design of our study, which could have influenced our findings.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial Disclosure: The National Alzheimerʼs Coordinating Center (NACC) database is funded by National Institute on Aging (NIA)/National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded Alzheimerʼs disease centers: P30 AG019610 (principal investigator [PI] Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P30 AG062428-01 (PI James Leverenz, MD) P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P30 AG062421-01 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P30 AG062422-01 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI Robert Vassar, PhD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P30 AG062429-01 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P30 AG062715-01 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), and P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Sponsor’s Role: The authors declare no role of any sponsor in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplementary Table S1: Demographic Characteristics of Participants at Initial Visit

Supplementary Table S2: The Hazard Ratio of APOE Genotype From Discrete-Time Proportional Hazards Model

REFERENCES

- 1.Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel D, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimerʼs disease. Neurology. 1993;43(8):1467–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strittmatter WJ, Roses AD, Apolipoprotein E. Alzheimerʼs disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:53–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genin E, Hannequin D, Wallon D, et al. APOE and Alzheimer disease: a major gene with semi-dominant inheritance. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(9):903–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu CC, Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(2):106–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seshadri S, Drachman DA, Lippa CF. Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele and the lifetime risk of Alzheimerʼs disease: what physicians know, and what they should know. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(11):1074–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chartier-Harlin MC, Parfitt M, Legrain S, et al. Apolipoprotein E, epsilon 4 allele as a major risk factor for sporadic early and late-onset forms of Alzheimerʼs disease: analysis of the 19q13.2 chromosomal region. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3(4):569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houlden H, Crook R, Backhovens H, et al. ApoE genotype is a risk factor in nonpresenilin early-onset Alzheimerʼs disease families. Am J Med Genet. 1998;81(1):117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;278(16):1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berlau DJ, Corrada MM, Head E, Kawas CH. APOE epsilon2 is associated with intact cognition but increased Alzheimer pathology in the oldest old. Neurology. 2009;72(9):829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinohara M, Kanekiyo T, Yang L, et al. APOE2 eases cognitive decline during aging: clinical and preclinical evaluations. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(5):758–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Berry-Kravis E, Evans DA, Bennett DA. The apolipoprotein E epsilon 2 allele and decline in episodic memory. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73(6):672–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oveisgharan S, Buchman AS, Yu L, et al. APOE epsilon2epsilon4 genotype, incident AD and MCI, cognitive decline, and AD pathology in older adults. Neurology. 2018;90(24):e2127–e2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lung FW, Yen YC, Chou LJ, Hong CJ, Wu CK. The allele interaction between apolipoprotein epsilon2 and epsilon4 in Taiwanese Alzheimerʼs disease patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;111(1):38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.