Abstract

Radiation-induced heart damage is a serious side effect caused by radiotherapy, especially during the treatment of cancer near the chest. Trimetazidine is effective at reducing inflammation in the heart, but how it affects radiation-induced cardiac fibrosis (RICF) is unknown. To investigate the potential effect and molecular mechanism, we designed this project with a C57BL6 male mouse model supposing trimetazidine could inhibit RICF in mice. During the experiment, mice were randomly divided into six groups including a control group (Con), radiation-damaged model group (Mod) and four experimental groups receiving low-dose (10 mg/kg/day) or high-dose (20 mg/kg/day) trimetazidine before or after radiation treatment. Apart from the control group, all mice chests were exposed to 6 MV X-rays at a single dose of 20 Gy to induce RICF, and tissue analysis was done at 8 weeks after irradiation. Fibroblast or interstitial tissues and cardiac fibrosis-like characteristics were determined using haematoxylin and eosin and Masson staining, which can be used to assess myocardial fibrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis and RT-PCR were used to determine gene expression and study the molecular mechanism. As a result, this study suggests that trimetazidine inhibits RICF by reducing gene expression related to myocyte apoptosis and fibrosis formation, i.e. connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, smad2 and smad3. In conclusion, by regulating the CTGF/TGF-β1/Smad pathway, trimetazidine could be a prospective drug for clinical treatment of RICF.

Keywords: radiotherapy, radiation-induced cardiac fibrosis, mice, trimetazidine

INTRODUCTION

Radiation therapy is an important method for the treatment of malignant chest tumours. However, long-term radiation toxicity in normal tissue is commonly observed and results in radiation-induced heart damage (RIHD) [1]. With the increasing number and prolonged survival times of patients, researchers have gradually found that RIHD offsets some benefits and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in cancer survivors [2]. Although the morbidity of RIHD has been reduced by optimal treatment plans and techniques with radiation, modern technology does not eliminate the risk of RIHD [3, 4]. Radiation-induced cardiac fibrosis (RICF) has both acute and chronic stages of RIHD based on the specific pathology, and it is thought to be a major contributor to myocardial remodelling and vascular changes [5]. Therefore, reducing the direct radiation dose to the heart and screening for and diagnosing these events as early as possible are essential for preventing RICF, and drugs remain an effective means of prevention and treatment [5].

Trimetazidine is a myocardial energy metabolism drug that selectively inhibits the activity of mitochondrial long-chain 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, resulting in the inhibition of free fatty acid (FFA) oxidation and the promotion of glucose oxidation [6]. In addition to its metabolic effects, trimetazidine exerts cardioprotective effects due to its reduction of oxidative damage, inhibition of inflammation and apoptosis, and improvement of endothelial function [7]. Studies have shown that trimetazidine can reduce myocardial injury in irradiated rats by regulating the expression levels of TNF-alpha and IL-10 in myocardial tissue to control the cardiac inflammatory response [8, 9]. Studies have also reported that trimetazidine can reduce the production of collagen in cardiac fibroblasts by reducing the expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 proteins in the myocardial tissue and cardiac fibroblasts of rats with chronic heart failure, with a subsequent anti-fibrosis effect [10]. TGF-β1 has been reported to participate in myocardial fibrosis due to radiation [11]. CTGF expression has also been reported to be essential for fibroblast proliferation, and fibroblasts are unresponsive to stimuli such as TGF-β that would normally strongly enhance their proliferation in the absence of CTGF [12]. However, the underlying mechanism is still not clear.

Therefore, this study aimed to explore the effects and mechanisms of trimetazidine in a RICF mouse model by measuring the expression levels of CTGF, TGF-β1, Smad2 and Smad3 in the heart tissues of these mice. This research provides an evidence base for the clinical use of trimetazidine to treat RIHD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals and grouping

Sixty male C57BL6 mice (SPF grade, 8 weeks old) weighing ~18–22 g were raised in isolated cages in temperature-controlled rooms under continuous 12-h artificial dark–light cycles. The animals received standard mouse chow and free access to tap water. We followed the institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. The mice were randomly divided into groups A, B, C, D, E and F, with 10 mice per group. The mice were kept at constant temperature (22 ± 2°C) and humidity (50 ± 10%) with normal light for 1 week.

Experimental design

The animals were randomly assigned to six groups: one control group, one radiation treatment only group and four experimental groups, namely, LDPre, LDPost, HDPre and LDPost.

For control group A (Con), the mice were raised under the same conditions without any intervention or medication. For model group B (Mod), the mice received only irradiation. For group C (LDPre), a low dose of trimetazidine (10 mg/kg/day) was administered by gavage at a fixed time every day from 1 week before irradiation to the end of the experiment. For group D (HDPre), a high dose of trimetazidine (20 mg/kg/day) was administered by gavage at a fixed time every day from 1 week before irradiation to the end of the experiment. For group E (LDPost), a low dose of trimetazidine (10 mg/kg/day) was administered by gavage at a fixed time every day from 1 week after irradiation to the end of the experiment. For group F (LDPost), a high dose of trimetazidine (20 mg/kg/day) was administered by gavage at a fixed time every day from 1 week after irradiation to the end of the experiment. The pharmaceutical trimetazidine hydrochloride was provided by Servier (Tianjin) (approved by H20055465).

The irradiation conditions and doses were as follows. A cardiac injury model was established by exposing murine heart to X-ray irradiation. The mice underwent intraperitoneal injections of 40 g/L chloral hydrate (0.01 mL/g) before local heart irradiation. Irradiation was performed with 6-MV X-ray beam energy with a 20 Gy/fraction dose and a 300 cGy/min dose rate and by setting the source-surface distance (SSD) at 100 cm and the radiation field for 1 × 1 cm using a CLINAC23EX electron linear accelerator (VARIAN, USA). The mice hearts were excised under deep anaesthesia at 8 weeks after exposure. The heart specimens were longitudinally divided into two parts: one part was fixed in formaldehyde solution and the other part was stored as a lysate.

Haematoxylin and eosin staining and histopathological analysis

The heart samples of the mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution. Then, 3-mm-thick heart tissue was cut from the maximum transverse diameter of the heart. The tissues were dehydrated, cleaned and embedded in paraffin. Then, 4-μm-thick slices were cut and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE). The changes in myocardial morphology were observed under a light microscope (×400).

Masson staining for collagen

Masson staining of the paraffin sections prepared from Bouin-fixed samples using a Masson’s Trichrome Staining Kit (Solarbio Science & Technology, Beijing) was performed to examine collagen fibres. The collagen volume fraction (CVF) was calculated by microscopic observation and with Image-Pro Plus software 6.0. The formula for CVF was myocardial interstitial collagen area/total visual field area. Six slices were taken for each group, and six high-powered fields were scored under the microscope and averaged for each slice.

Immunohistochemistry

The paraffin-embedded tissue sections (5 μm) were deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol with PBS and then incubated in blocking solution (3% H2O2) at room temperature for 10 min. After three washes in PBS (containing 0.1% Tween 20), the sections were incubated separately with rabbit anti-mouse and mouse anti-mouse primary antibodies (Wuhan Elabscience, China) overnight at 4°C. The sections were then washed in PBS and incubated with the corresponding reagents in the immunohistochemistry secondary antibody SP kit (detection system of Streptomyces rabbit ovalbine-biotin method) (Beijing ASGB-BIO, China) at room temperature for 30 min. All sections were then stained with diaminobenzidine reagent and haematoxylin, dehydrated, mounted and viewed under a light microscope. Positivity for the expression of CTGF, TGF-β1, SMAD2 and SMAD3 was assessed using Image-Pro plus.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the heart tissues of C57BL/6 mice by RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and quantified by spectrophotometry. RNA (2 μg) was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis according to the protocol for a reverse transcription system (Takara, Dalian, China). Then, cDNA, together with SYBR and specific primers (TAKARA, Dalian, China), was used for RT-PCR, which was performed by RT-PCR Master Mix (Takara, Dalian, China) in a 20 μL reaction volume following the manufacturer’s instructions. The RT-PCR reaction was performed with the following cycling parameters: 95°C for 30 s, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s followed by 60°C for 30 s, with the last steps at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s and 95°C for 15 s. The relative transcription levels were calculated by the relative standard curve method. The cycle threshold (Ct SYBR) of β-actin was used as an internal control. The primers for CTGF, TGF-β1, smad2 and smad3 were designed and synthesized by RuiBo Biotech Co. Ltd. (Qingdao, China), and the sequences were as follows: CTGF(mouse), forward: 5′-CAA GGA CCG CAC AGC AGT TGG-3′ and reverse: 5′-CAG GCA GTT GGC TCG CAT CAT AG -3′; TGF-β1(mouse), forward: 5′-CGC AAC AAC GCC ATC TAT GA-3′ and reverse: 5′-ACT GCT TCC CGA ATG TCT GA-3′; Smad2(mouse), forward: 5′-GTC GTC CAT CTT GCC ATT CAC TCC-3′ and reverse: 5′-GCT CTC CAC CAC CTG CTC CTC -3′; and Smad3(mouse), forward: 5′-AGG AGG AGA AGT GGT GCG AGA AG-3′ and reverse: 5′- AGC CGA CCA TCC AGT GAC CTG-3′; β-actin (mouse) as housekeeping gene, forward: 5′-GAT TAC TGC TCT GGC TCC TAG C-3′ and reverse: 5′-GAC TCA TCG TAC TCC TGC TTG C-3′.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17. All continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. If the distribution of the variable was normal, the t-test was used, otherwise, the Wilcoxon test was used. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Effect of trimetazidine on cardiac morphology in mice

All mice except for one in the Mod group, two in the LDPre group and one in the LDPost group survived to the end of the final administration of trimetazidine. The observations by light microscopy were as follows. In the Con group, normal myocardial fibres were pink, irregular, short, cylindrical or banded, with blue–purple and oval nuclei, a small amount of loose connective tissue and abundant capillaries between the myocardium, without degeneration or oedema. In the Mod group, there was increased myocardial interstitial fibre deposition with a large amount of inflammatory cell infiltration. In the LDPre, LDPost, HDPre and LDPost groups, the myocardial interstitium showed slight fibrous deposition and inflammatory cell infiltration. Among them, the degrees of inflammation were lower in HDPost and LDPost than in HDPre and LDPre.

Trimetazidine inhibits radiation-induced cardiac fibrosis in mice

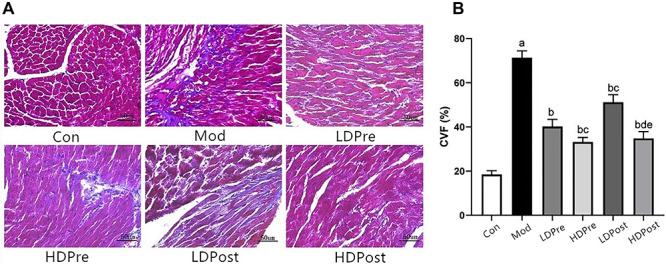

As myocardial fibrosis contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiac injury caused by radiation exposure [13], we investigated whether trimetazidine attenuated the collagen deposition in heart tissue caused by radiation in C57BL6 mice. As shown in Fig. 1, substantial deposition of collagen was detected in the cardiac interstitial tissues of the irradiation groups compared with the control group. However, the decreased deposition of collagen was ameliorated in the trimetazidine treatment groups (LDPre, LDPost, HDPre and LDPost). Among them, the deposition of collagen was lower in LDPost and HDPost than in HDPre and LDPre. In summary, trimetazidine ameliorated RICF in mice.

Fig. 1.

Effects of trimetazidine on myocardial collagen in mice. (A) Masson staining 8 weeks after irradiation showed that collagen fibres increased and invaded into the muscles. The myocardium is indicated in red and collagen is indicated in blue. Magnification 400×. (B) The collagen volume fraction (CVF) in myocardial tissue was calculated. As shown in (A), the proportion of collagen fibre in the heart of the radiation-only group was significantly higher than those of the other groups. The analysis found no significant difference between the experimental groups LDPre and LDPost (cP > 0.05) or HDPre and HDPost (dP > 0.05), but there were significant differences between experimental groups LDPre and HDPre (cP < 0.05) and between LDPost and HDPost (eP < 0.05).

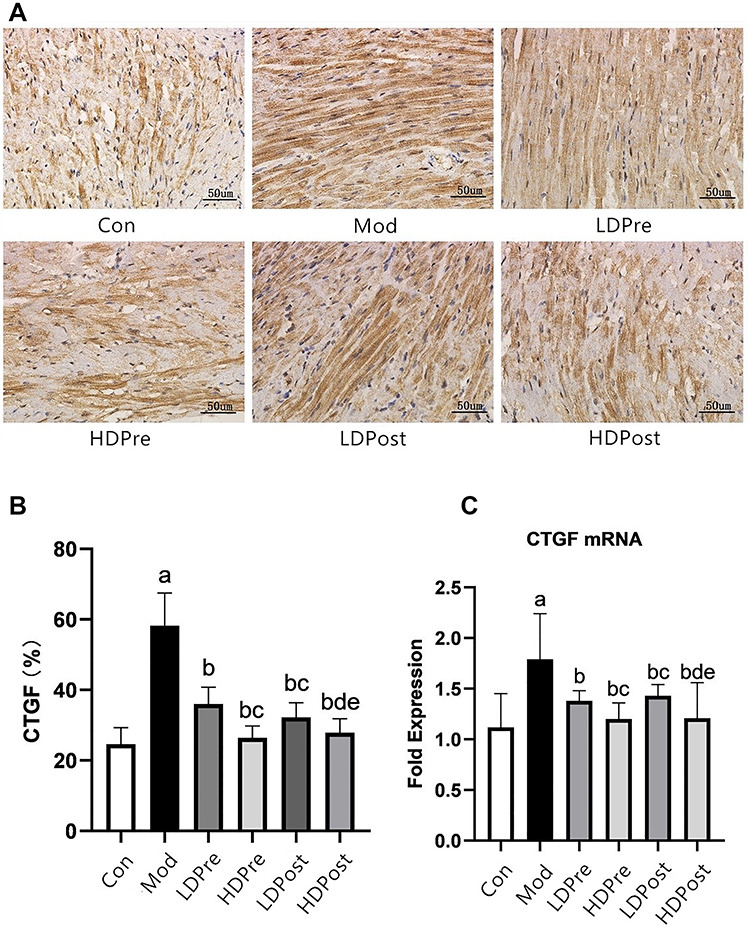

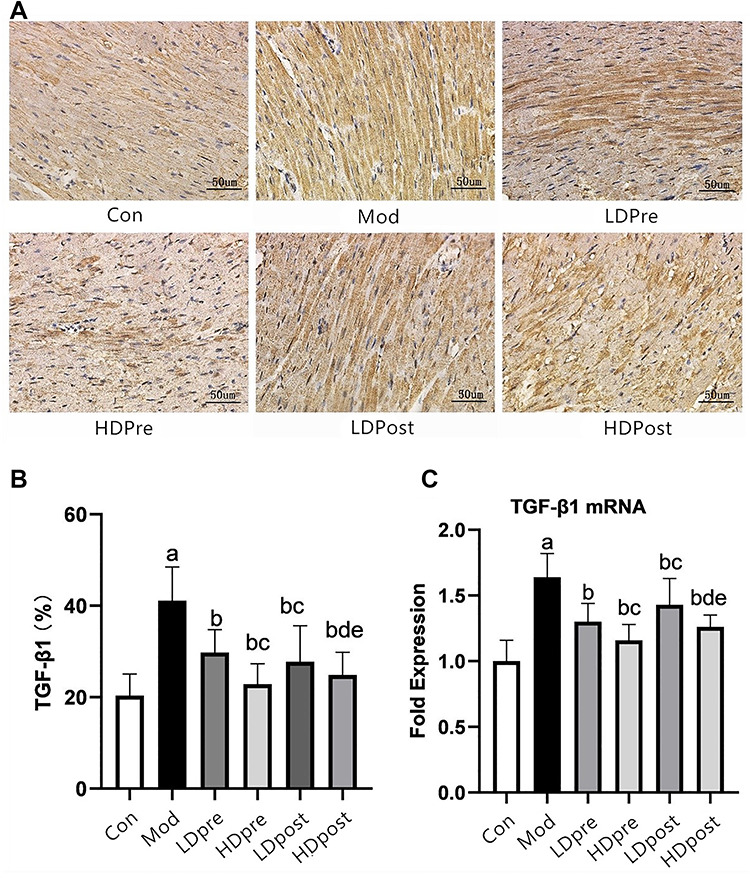

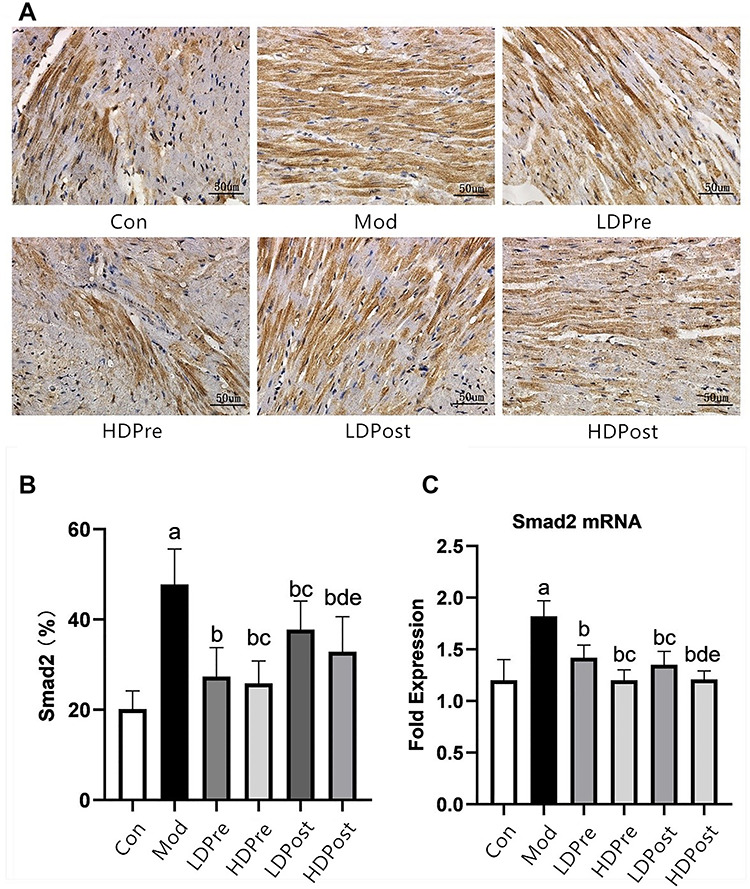

Trimetazidine decreases the expression levels of CTGF, TGF-β1, Smad2 and Smad3 in the myocardial tissues of mice

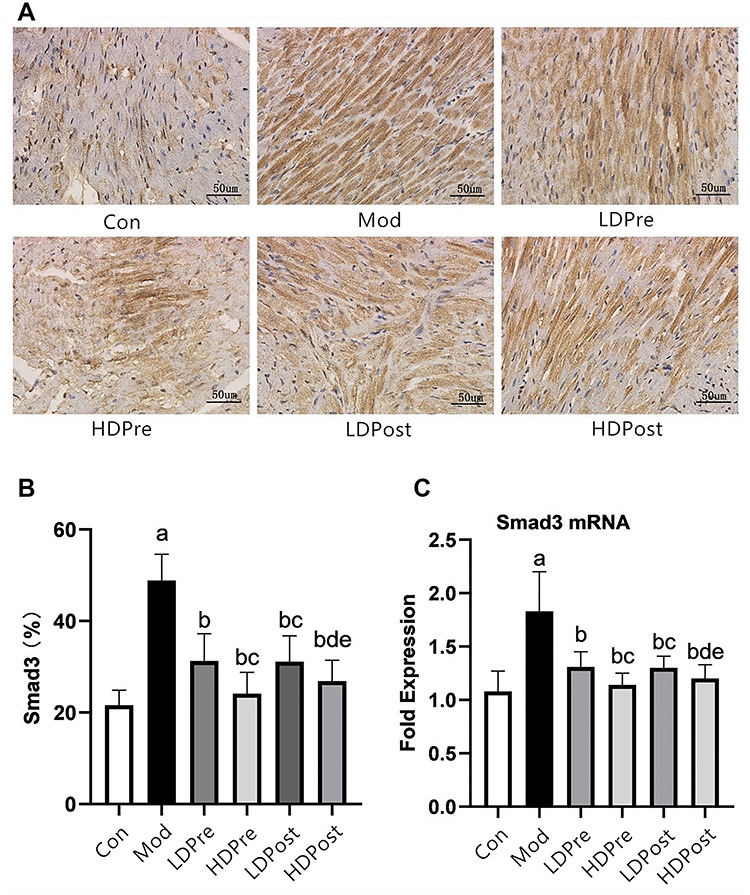

Immunohistochemistry analyses were performed to evaluate the expression levels of CTGF, TGF-β1, Smad2 and Smad3 in the heart (Figs. 2A, 3A, 4A and 5A). Increases in CTGF, TGF-β1, Smad2 and Smad3 expression were found in the radiation groups at 8 weeks post-irradiation compared with the control group (P < 0.05). Significant decreases in expression were observed in the LDPre, LDPost, HDPre and HDPost groups at 8 weeks post-irradiation (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in expression between the LDPre and LDPost groups (P > 0.05) or between the HDPre and HDPost groups (P > 0.05). The HDPost group exhibited significantly lower expression levels of these proteins than did the LTPost group (P < 0.05). Therefore, a higher dosage of trimetazidine administration appeared to be more effective for reducing CTGF, TGF-β1, Smad2 and Smad3 expression (Figs. 2B, 3B, 4B and 5B).

Fig. 2.

CTGF expression in the mouse heart. (A) Immunohistochemistry was performed 8 weeks after irradiation to reveal the effect of trimetazidine on the changes in CTGF in mice. Magnification 400×. (B) Comparison of the positive expression rates of CTGF protein in the myocardial tissues of each group. (C) Quantitative analysis of the transcriptional expression of CTGF by qRT-PCR. The CTGF levels in the mouse hearts of the other groups were lower than those of the Mod group (bP < 0.05). The low-dose groups and high-dose groups displayed significant differences (cP < 0.05, dP < 0.05). The analysis found no significant difference between groups LDPre and LDPost (cP > 0.05), and there was no significant difference between groups HDPre and HDPost (dP > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

TGF-β1 expression in the mouse heart. (A) Immunohistochemistry was performed 8 weeks after irradiation to reveal the effect of trimetazidine on changes in TGF-β1 in mice. Magnification 400×. (B) Comparison of the positive expression rates for TGF-β1 protein in the myocardial tissues of each group. (C) Quantitative analysis of the transcriptional expression of TGF-β1 by qRT-PCR. The TGF-β1 levels in the mouse hearts of the other groups were lower than those of the Mod group (bP < 0.05). The low-dose groups and high-dose groups showed significant differences (cP < 0.05, dP < 0.05). The analysis found no significant difference between groups LDPre and LDPost (cP > 0.05) or between groups HDPre and HDPost (dP > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Smad2 expression in the mouse heart. (A) Immunohistochemistry was performed 8 weeks after irradiation to reveal the effect of trimetazidine on the changes in Smad2 in mice. Magnification 400×. (B) Comparison of the positive expression rates for Smad2 protein in the myocardial tissues of each group. (C) Quantitative analysis of the transcriptional expression of Smad2 by qRT-PCR. The Smad2 levels in the mouse hearts of the other groups were lower than those of the Mod group (bP < 0.05). The low-dose groups and high-dose groups showed significant differences (cP < 0.05, dP < 0.05). The analysis found no significant difference between groups LDPre and LDPost (cP > 0.05) or between groups HDPre and HDPost (dP > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Smad3 expression in the mouse heart. (A) Immunohistochemistry was performed 8 weeks after irradiation to reveal the effect of trimetazidine on the changes in Smad3 in mice. Magnification 400×. (B) Comparison of the positive expression rates of Smad3 protein in the myocardial tissues of each group. (C) Quantitative analysis of the transcriptional expression of Smad3 by qRT-PCR. The Smad3 levels in the mouse hearts of the other groups were lower than those of the Mod group (bP < 0.05). The low-dose groups and high-dose groups showed significant differences (cP < 0.05, dP < 0.05). The analysis found no significant difference between groups LDPre and LDPost (cP > 0.05) or between groups HDPre and HDPost (dP > 0.05).

Trimetazidine decreases the expression of CTGF, TGF-β1, Smad2 and Smad3 mRNA in the myocardial tissues of the mice in each group

The mRNA levels of CTGF, TGF-β1, Smad2 and Smad3 in the hearts taken from the mice were evaluated using qRT-PCR, and the means and standard deviations of the mRNA levels of CTGF, TGF-β1, Smad2 and Smad3 are shown in histograms. Compared with the control group (Con), the Mod group showed significant increases in CTGF, TGF-β1, Smad2 and Smad3 mRNA levels. Decreased expression levels of the mRNA of CTGF, TGF-β1, Smad2 and Smad3 were observed in the LDPre, LDPost, HDPre and HDPost groups at 8 weeks post-irradiation. While there were no significant differences in the mRNA levels of these genes between groups LDPre and LDPost (P > 0.05), groups HDPre and HDPost exhibited significantly lower levels of mRNA than groups LDPre and LDPost. Interestingly, the mRNA levels of these genes in experimental groups LDPre and HDPre were significantly different (P < 0.05). Higher doses of trimetazidine administration appeared to be more effective at reducing the mRNA levels (P < 0.05). The results of immunohistochemical analysis showed similar patterns at the protein level to those at the mRNA level (Figs. 2C, 3C, 4C and 5C).

DISCUSSION

Radiation-induced heart damage is one of the side effects of radiotherapy for chest malignancies. Cardiac fibrosis and remodelling induced by radiotherapy can cause cardiac dysfunction. Previous studies [16] have shown that cardiac radiation can induce myocardial inflammation in mice in the early stage and induce myocardial fibrosis in the late stage to enhance myocardial remodelling. In studies of RIHD, the radiation dose reported in the literature included several Gy values [14], but most of them were >10 Gy, with the highest being 50 Gy [15]. The large difference in irradiation dose for modelling is related to the size of the irradiation field. When animals received local irradiation only in the cardiac region, their whole body was less affected by the radiation and they were able to tolerate a large dose of irradiation. Considering that the heart is a radiation-insensitive organ, this high dose of local irradiation to the heart exerts more significant damage to the heart and is more suitable for animal RICF research. In preliminary experiments in mice, when the radiation dose was increased to 20 Gy, fibrosis injury and structural damage to the heart resulted [16]. Therefore, an X-ray dose of at least 20 Gy to the cardiac area was considered necessary for the construction of RICF conditions in a mouse model. In this study, we found high increases in collagen deposition at 8 weeks. There are several possibilities. As the small heart and lungs of mice are close together, it is possible that some mice had radiation-induced lung injury and the pulmonary fibrosis aggravated heart damage while the decrease in lung function induced cardiovascular fibrosis. We should analyse the lung tissue in future experiments to determine whether it is damaged and the degree of damage.

Radiation-induced vascular damage is the fundamental cause of myocardial fibrosis. Radiation can act on endothelial cells of the myocardial capillaries, causing them to proliferate, become injured, swell and degenerate. Vascular intimal collagen deposition can cause pipe wall thickening and luminal stenosis. The deposition of collagen is also the reason for capillary luminal stenosis, thrombosis and the reduction in myocardial blood supply [17]. Radiation-induced myocardial fibrosis is the result of a multicellular interaction. After irradiation, swelling of the endothelial cells induces early acute inflammation (in the first few minutes of ionizing radiation), e.g. neutrophil infiltration and macrophage and monocyte activation, thereby promoting the release of cytokines such as TNF, IL-1, IL-6 and IL-8. After a few hours of irradiation, pro-fibrosis cytokines such as bFGF, IGF, CTGF, PDGF and TGF-β are released [13]. Trimetazidine, a long-chain fatty acid β-oxidative inhibitor, is thought to switch cardiac myocyte metabolism from FFA metabolism to glucose metabolism, thereby improving the myocardial oxidative metabolism effect [6]. At the same time, numerous clinical trials have indicated that trimetazidine may improve cardiac function in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy and heart failure [17, 18]. In a study by Belardinelli et al. [19], trimetazidine was able to improve endothelial function. However, studies on the influence of trimetazidine on cardiac fibrosis induced by radiation are rare [20]. In this study, we examined whether trimetazidine could suppress the cardiac fibrosis induced by radiation. The result shows that radiation exposure aggravated the degree of myocardial fibrosis in mice and caused heart dysfunction through cardiac fibrosis. Cardiac fibrosis causes systolic dysfunction and an inhomogeneity in conduction, leading to heart failure and arrhythmia [20]. However, 8 weeks after X-ray irradiation, the myocardial cell injury of mice in the trimetazidine dose group was less than that in the model group. With increasing trimetazidine dose, the degree of myocardial cell damage is reduced; in terms of protecting against radiation-induced myocardial fibrosis in mice, trimetazidine exhibited a better effect in the high-dose group than in the low-dose group. Additionally, regarding the medication before irradiation and irradiation after drug use, no obvious correlation between the different degrees of myocardial injury was found. This result may be because trimetazidine is associated with insufficient myocardial oxygen; by increasing oxygen utilization, cells generate sufficient ATP energy, thereby improving ischaemic/hypoxic conditions due to the imbalance in myocardial cell energy metabolism and protecting myocardial function. In mice given trimetazidine before irradiation, in a normal environment, the pharmacological effects of trimetazidine are not fully exerted [21].

TGF-β1 can positively regulate the proliferation, apoptosis and migration of cells and the synthesis of ECM components, such as collagen, in the heart. Therefore, TGF-β1 plays a major role in the process of cardiovascular remodelling. Studies have shown that TGF-β1 is involved in radiation-induced fibrosis [22, 23] and that TGF-β is a key regulator of cardiac fibrosis [24]. TGF-β can promote the transformation and proliferation of myocardial fibroblasts by inducing Smad protein expression and activity [25]. The TGF-β1–Smad complex, a transcription factor, induces the activation of a large number of fibrosis genes, thus playing an important role in myocardial fibrosis [26, 27]. TGF-β1 initiates its cellular response by binding to TGF-β1 receptor phosphorylates, i.e. RSmads (Smad2 and Smad3). Subsequently, activated SMADs assemble with Smad4 and translocate into the nucleus where the SMAD complex interacts with canonical SMAD-binding elements of target genes to activate a profibrotic programme of transcription [28]. TGF-β can promote the transformation and proliferation of myocardial fibroblasts by inducing Smad protein activity. These proteins promote fibroblast proliferation and attach to the original deposit, accelerating the growth of myocardial fibrosis in cardiac remodelling and heart failure. Smads can cause myocardial fibrosis and myocardial cell apoptosis. The expression of Smad proteins can occur in a variety of cardiac pathophysiological states and have fatal effects on cardiac myocytes; hence, their importance in myocardial fibrosis has been increasingly recognized. In this study, TGF-β1 and myocardial collagen were used as pathological molecular indicators to reflect the pathological process of fibrosis in RICF, which is consistent with the changes in CVF observed by Masson staining. These experimental results also confirmed the reliability of the 20-Gy single-irradiation method for the construction of the progressive RICF model. In the current study, we found that the expression levels of TGF-β1, Smad2 and Smad3 were higher in the hearts of irradiated mice than in those of the control mice and that trimetazidine reduced the expression of these factors. However, SMAD proteins are always expressed in the heart and are activated via phosphorylation. Therefore, measuring the expression of the SMAD proteins does not indicate whether they were activated, and more experimental results are needed on this. In conclusion, our results suggest that the decrease in TGF-β1 is one of the possible pharmacological mechanisms of trimetazidine action towards alleviating RICF.

CTGF, a typical member of the CCN (CTGF, Cyr61 and Nov) matricellular protein family, is a downstream mediator of TGF-β1-induced activation of fibroblasts. A TGF-β1 response element is located in the CTGF promoter, indicating that CTGF is likely to be a fibroblast-selective mediator of the profibrotic effects of TGF-β1 [29]. Furthermore, the induction of CTGF can also occur independently of TGF-β1/Smad signalling through the activation of the Rho/ROCK pathway. A previous study demonstrated that pirfenidone protects against the progression of radiation-induced fibrosis both in vivo and in vitro by inhibiting the proliferation and differentiation of intestinal fibroblasts and suppressing the TGF-β1/Smad/CTGF signalling pathways [30]. Based on our results, CTGF expression was higher in the hearts of irradiated mice than in those of the control mice, and trimetazidine reduced the expression of CTGF. The increasing and decreasing trend of CTGF was almost the same as that of TGF-β1 by immunohistochemistry and RT-PCR.

There are some limitations to this study that should be noted. First, the mice in groups C–F received oral gavage every day for 7 or 9 weeks. This is a stressful experience that could have affected the health of the mice. For a proper comparison, the mice in group B should have been administered vehicle by gavage. However, we failed to consider this. Second, SMAD proteins are always expressed in the heart, and they are activated via phosphorylation. Therefore, measuring the expression of SMAD proteins does not indicate whether they were activated. Third, because of time limits, the details of how trimetazidine affects the pathology of RIHD and the molecular mechanism of trimetazidine action are not clear. Additional experiments may be conducted in the future. Finally, future studies should be performed in both male and female mice to determine whether gender affects the study outcomes, and research into the effect of trimetazidine on the early phase of cytokine and histological changes, e.g. 1 day, 3 day and 1 week after X- irradiation, should be undertaken to investigate the related pathways.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the CTGF and TGF-β1/Smad signalling pathways are involved in the pathological process of RICF. Our study suggests that trimetazidine is an effective treatment for RICF. Specifically, the findings from experimental groups HDPre and HDPost suggest that the effectiveness of trimetazidine treatment is more pronounced when applied at a higher dosage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors appreciate all the authors for their contributions and physicians and participants from the the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. They are also grateful to all the reviewers and editors for their patience regarding this manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

References

- 1. Tapio S. Pathology and biology of radiation-induced cardiac disease. J Radiat Res 2016;57:439–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davis M, Witteles RM. Radiation-induced heart disease: An under-recognized entity? Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2014;16:317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boero IJ, Paravati AJ, Triplett DP et al. Modern radiation therapy and cardiac outcomes in breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016;94:700–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boekel NB, Schaapveld M, Gietema JA et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in a large, population-based cohort of breast cancer survivors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016;94:1061–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ma C-X, Zhao X-K, Li Y-D. New therapeutic insights into radiation-induced myocardial fibrosis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2019;10: 2040622319868383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kantor PF, Lucien A, Kozak R et al. The antianginal drug trimetazidine shifts cardiac energy metabolism from fatty acid oxidation to glucose oxidation by inhibiting mitochondrial long-chain 3-ketoacyl coenzyme a thiolase. Circ Res 2000;86:580–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ruixing Y, Wenwu L, Al-Ghazali R. Trimetazidine inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis in a rabbit model of ischemia-reperfusion. Transl Res 2007;149:152–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhou Y, Chen H-Y, Wang J-Y et al. Effects of trimetazidine on TNF - expression after myocardial injury in rats. Progress in Modern Biomedicine 2014;14:1821–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou Y, Chen H-Y, Wang J-Y et al. Effects of trimetazidine on IL-10 expression after myocardial injury in rats. Progress in Modern Biomedicine 2013;20:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ma D, Xu T, Cai G et al. Effects of ivabradine hydrochloride combined with trimetazidine on myocardial fibrosis in rats with chronic heart failure. Exp Ther Med 2019;18:1639–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Subramanian V, Seemann I, Merl-Pham J et al. Role of TGF Beta and PPAR alpha Signaling pathways in radiation response of locally exposed heart: Integrated global Transcriptomics and proteomics analysis. J Proteome Res 2017;16:307–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lipson KE, Wong C, Teng Y et al. CTGF is a central mediator of tissue remodeling and fibrosis and its inhibition can reverse the process of fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2012;5:S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taunk NK, Haffty BG, Kostis JB et al. Radiation-induced heart disease: Pathologic abnormalities and putative mechanisms. Front Oncol 2015;5:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeBo RJ, Lees CJ, Dugan GO et al. Late effects of Total-body gamma irradiation on cardiac structure and function in male rhesus macaques. Radiat Res 2016;186:55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kiscsatari L, Sarkozy M, Kovari B et al. High-dose radiation induced heart damage in a rat model. In Vivo 2016;30:623–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao F-L, Sun Y, He X-J et al. Study on cardiac radiation damage in mice after cisplatin combined with single large dose irradiation. Journal of Precision Medicine 2019;34:249–53. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Belardinelli R, Cianci G, Gigli M et al. Effects of trimetazidine on myocardial perfusion and left ventricular systolic function in type 2 diabetic patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2008;51:611–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fragasso G, Salerno A, Lattuada G et al. Effect of partial inhibition of fatty acid oxidation by trimetazidine on whole body energy metabolism in patients with chronic heart failure. Heart 2011;97:1495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Belardinelli R, Solenghi M, Volpe L et al. Trimetazidine improves endothelial dysfunction in chronic heart failure: An antioxidant effect. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1102–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang L, Ding W-Y, Wang Z-H et al. Early administration of trimetazidine attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats by alleviating fibrosis, reducing apoptosis and enhancing autophagy. J Transl Med 2016;14:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lopatin YM, Rosano GM, Fragasso G et al. Rationale and benefits of trimetazidine by acting on cardiac metabolism in heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2016;203:909–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gu J, Li H-L, Wu H-Y et al. Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate attenuates radiation-induced fibrosis damage in cardiac fibroblasts. J Asian Nat Prod Res 2014;16:941–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boerma M, Wang J, Sridharan V et al. Pharmacological induction of transforming growth factor-beta1 in rat models enhances radiation injury in the intestine and the heart. PLoS One 2013;8:e70479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hu H-H, Chen D-Q, Wang Y-N et al. New insights into TGF-beta/Smad signaling in tissue fibrosis. Chem Biol Interact 2018;292:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gao H, Bo Z, Wang Q et al. Salvanic acid B inhibits myocardial fibrosis through regulating TGF-beta1/Smad signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2019;110:685–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miyazawa K, Miyazono K. Regulation of TGF-beta family Signaling by inhibitory Smads. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2017;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guo Y, Gupte M, Umbarkar P et al. Entanglement of GSK-3beta, beta-catenin and TGF-beta1 signaling network to regulate myocardial fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2017;110:109–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gauldie J, Bonniaud P, Sime P et al. TGF-beta, Smad3 and the process of progressive fibrosis. Biochem Soc Trans 2007;35:661–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhu Y, Zhou J, Tao G. Molecular aspects of chronic radiation enteritis. Clin Invest Med 2011;34:E119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sun Y-W, Zhang Y-Y, Ke X-J et al. Pirfenidone prevents radiation-induced intestinal fibrosis in rats by inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and differentiation and suppressing the TGF-beta1/Smad/CTGF signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol 2018;822:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]