A 71-year-old man with alcohol-induced cirrhosis, complicated by portal hypertension, esophageal and rectal varices, and chronic portal vein thrombosis, presented to the hospital with rectal bleeding. This was his fourth presentation over the past year, with multiple diagnostic colonoscopies revealing rectal varices as the source of the bleeding and no therapeutic interventions performed. He was hemodynamically stable with unremarkable physical examination findings. Laboratory results revealed hemoglobin of 9.6 g/dL, platelet count of 103 × 109/L, and international normalized ratio of 1.4. The remainder of his laboratory workup was within normal limits.

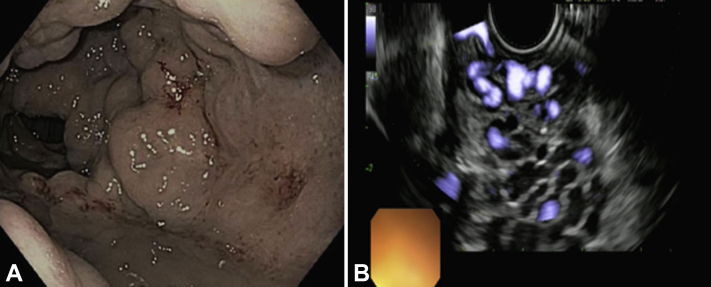

The patient was managed conservatively, and a colonoscopy was performed. This confirmed the presence of large rectal varices extending from the anorectal junction superiorly with stigmata of recent bleeding (Fig. 1A). The patient was deemed to be high risk for interventional radiology (IR)-guided therapies such as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and for surgical intervention. After multidisciplinary input, the plan was to proceed with EUS-guided coil therapy (Video 1, available online at www.VideoGIE.org).

Figure 1.

A, Colonoscopy revealing the presence of large rectal varices extending from the anorectal junction superiorly with stigmata of recent bleeding. B, Dense network of multiple hypoechoic tubular structures with Doppler venous flow consistent with rectal varices.

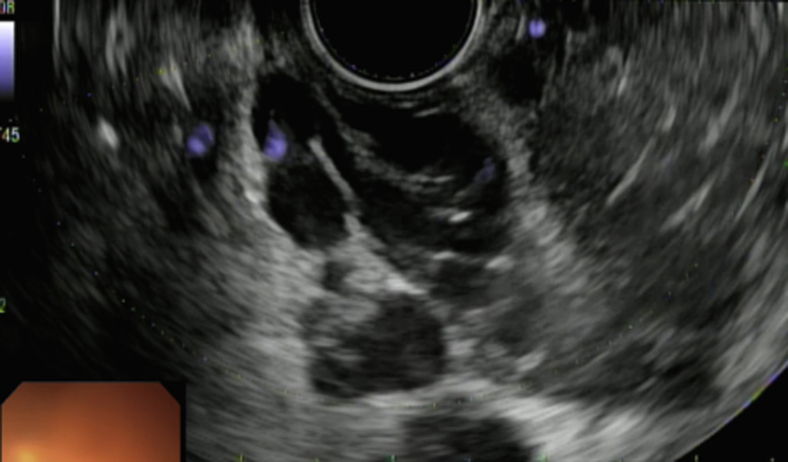

On EUS, a dense network of multiple hypoechoic tubular structures with Doppler flow was encountered (Fig. 1B). The decision was made to proceed with EUS-guided coil injection. The coil was loaded into the EUS-FNA needle (Fig. 2). The largest varix measured 4 mm in cross-sectional diameter. The perforator vein, responsible for feeding the various variceal nests, was identified traversing the muscularis propria (Fig. 3). One 0.035-in × 14-mm × 20-cm embolization coil was placed into the perforator vein through a 19-gauge FNA needle (Fig. 4). Doppler confirmed significant reduction in blood flow at 2 and 5 minutes (Fig. 5). The patient tolerated the procedure well. At the 6-month follow-up, he had no recurrent bleeding, admission, or need for transfusion (Fig. 6), with repeat colonoscopy revealing significantly diminished rectal varices and EUS confirming markedly reduced Doppler flow (Fig. 7A and B).

Figure 2.

Extrusion of back-loaded embolization coil from the tip of the EUS-FNA needle.

Figure 3.

Identification of the perforator vein (traversing muscularis propria), which is responsible for feeding the various variceal nests and is the target for coil embolization.

Figure 4.

EUS-FNA needle puncture (yellow arrow) of the perforator vein with deployment of the embolization coil into the perforator vein (red arrow).

Figure 5.

Significant reduction in Doppler flow within the perforator vein and variceal nests at 2 and 5 minutes after coil embolization.

Figure 6.

Graph illustrating admission for rectal bleeding, transfusion, and colonoscopy before and after EUS-guided coil therapy of rectal varices.

Figure 7.

A, Repeat colonoscopy at 6 months revealing significantly diminished rectal varices. B, Radial EUS at 6-month follow-up confirming collapsed varices with absent Doppler flow.

Discussion

Rectal varices occur as an adverse event of portal hypertension and are associated with lower GI bleeding. Although the prevalence rate in patients with cirrhosis may be as high as 56%, significant bleeding occurs in less than 5% of patients.1,2 Diagnosis usually requires endoscopy alone or concomitant EUS. Endoscopic treatment options include variceal band ligation and endoscopic sclerosant injections, such as glue or thrombin (which can be injected alone or as adjunctive therapy with coils). Although effective in bleeding cessation, they are associated with adverse events and risk of recurrence.3 Nonendoscopic treatment options include IR-guided therapies, such as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts and balloon retrograde transvenous obliteration.1 For cases refractory to IR and endoscopic measures, surgery can be performed. This includes suture ligation, vein occlusion, and shunt surgery.1 Surgery, however, has been associated with mortality rates as high as 80%.4 Although EUS-guided coil injection has been described in the past,5,6 this usually entails injection of coils into the variceal nests. There are limited data highlighting this technique of targeting the perforator vein to promote hemostasis and variceal thrombosis. The perforator vein is thought to supply the variceal nest; by targeting this vessel instead of the variceal nest directly, hemostasis may be more easily achieved with fewer coils.

Conclusion

EUS-guided coil embolization by targeting the feeder or perforator vein is feasible and effective for the treatment of bleeding rectal varices in patients considered to be poor candidates for IR-guided or surgical therapies. This modality can result in fewer coils used to promote hemostasis, prolonged bleeding-free time, and reduced episodes of rectal bleeding.

Disclosure

Dr Thompson is a consultant for and receives research support from Apollo Endosurgery, GI Dynamics, Olympus America, and USGI Medical; is consultant for Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Fractyl; and receives research support from Aspire Bariatric. Dr Ryou is a consultant for Olympus America, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Fujifilm. All other authors disclosed no financial relationships.

Supplementary data

EUS-guided coil injection of rectal varices.

References

- 1.Al Khalloufi K., Laiyemo A.O. Management of rectal varices in portal hypertension. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2992–2998. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i30.2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chawla Y., Dilawari J.B. Anorectal varices–their frequency in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. Gut. 1991;32:309–311. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato T., Yamazaki K., Akaike J. Retrospective analysis of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for rectal varices compared with band ligation. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2010;3:159–163. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S15401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bittinger M. Bleeding from rectal varices in patients with liver cirrhosis - an ominous event. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:270. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philips C.A., Augustine P. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided management of bleeding rectal varices. ACG Case Rep J. 2017;4:e101. doi: 10.14309/crj.2017.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukkada R.J., Mathew P.G., Francis Jose V. EUS-guided coiling of rectal varices. VideoGIE. 2017;2:208–210. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

EUS-guided coil injection of rectal varices.