Abstract

While much of the focus of sociobiology concerns identifying genomic changes that influence social behaviour, we know little about the consequences of social behaviour on genome evolution. It has been hypothesized that social evolution can influence the strength of negative selection via two mechanisms. First, division of labour can influence the efficiency of negative selection in a caste-specific manner; indirect negative selection on worker traits is theoretically expected to be weaker than direct selection on queen traits. Second, increasing social complexity is expected to lead to relaxed negative selection because of its influence on effective population size. We tested these two hypotheses by estimating the strength of negative selection in honeybees, bumblebees, paper wasps, fire ants and six other insects that span the range of social complexity. We found no consistent evidence that negative selection was significantly stronger on queen-biased genes relative to worker-biased genes. However, we found strong evidence that increased social complexity reduced the efficiency of negative selection. Our study clearly illustrates how changes in behaviour can influence patterns of genome evolution by modulating the strength of natural selection.

Keywords: social complexity, behaviour, caste-biased gene expression, relaxation of selection

1. Introduction

Understanding the processes underlying the evolution and elaboration of sociality is a central goal of sociobiology. Eusocial behaviour evolved multiple times in insects and is characterized by overlapping generations, cooperative brood care and reproductive division of labour [1–4]. It is commonly theorized that eusociality evolved by positive selection on mutations that promote altruistic behaviours [5–9]. It is not surprising then that the majority of molecular population genetic studies of social insects focus only on positive selection [10–16]. While understanding how changes in DNA adaptively drive changes in social behaviour is clearly important, there is a growing interest in understanding how the evolution of social behaviour can influence patterns of genome evolution [17]. Some phenotypes, such as those associated with eusociality, can have substantive consequences on demography and effective population size [17,18], and these changes in effective population size can have profound consequences on the evolutionary landscape in ways that may influence molecular evolution and genome architecture and complexity [19,20]. In other words, the evolution of social behaviour can potentially feed back to influence genome evolution [17,18]. Evaluating this bidirectional link between eusociality and the genome is critical for both disentangling the molecular causes and consequences of eusocial evolution, and for understanding if and how behaviour's influence on the genome could have contributed to the fitness of incipient eusocial lineages.

One plausible way through which sociality can influence patterns of genome evolution is by altering the efficiency of negative selection. The evolution of eusociality has been hypothesized to influence the efficiency of negative selection in a caste- and lineage-specific way. Theory predicts that, all other factors being equal, direct selection on queen traits is more efficient than indirect selection on worker traits [21] because of the stronger association between fitness and the transmission of alleles in the former. This hypothesis directly predicts a relaxation of negative selection on genes with indirect fitness effects (i.e. genes underlying worker traits associated with helping) than genes with direct fitness effects (i.e. genes affecting queen traits). Additionally, eusociality is hypothesized to reduce the effective population size (Ne) [22–29] because of overlapping generations, often extreme sex ratios and reproductive skews (e.g. hundreds to thousands of sterile workers relative to a small number of reproductives), and male-production by workers. A corollary of this concept is that the greater the reproductive skew found within a colony, the greater the reduction in effective population size. The effective population size is a central parameter in population genetics that directly influences the strength of genetic drift, thereby influencing the efficiency of natural selection [30]—a process that can influence genome structure and complexity [19,20]. Genetic drift in populations with small Ne can overwhelm natural selection allowing deleterious mutations to ‘drift’ up to higher frequencies. This hypothesis has been indirectly supported by elevated rates of amino acid evolution in four eusocial species relative to solitary insects [25], although we note that other evolutionary forces can be responsible for this signature, including positive selection on beneficial mutations [31].

We used available population genomic datasets for the advanced eusocial honeybee Apis mellifera [10], the primitively eusocial bumblebee Bombus impatiens [12], the primitively eusocial paper wasp Polistes dominula [11] and the advanced eusocial fire ant Solenopsis invicta [32], in conjunction with existing population transcriptomic data for several other social and solitary insects [25], to investigate the relationship between caste and social complexity on the strength of negative selection. We quantified the strength of negative selection using the distribution of fitness effects approach [25,33–38], which relies on the principal that negative selection skews the allele frequency distribution towards rare variants. This involved analysing within-species polymorphism data, where the strength of negative selection at 0-fold (i.e. sites at which all changes are non-synonymous), 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs), intronic, and intergenic sites can be estimated by comparing their allele frequency distributions to fourfold sites (i.e. those at which all changes are synonymous) predicted to be neutral [25,33–38]. We used our population genomic datasets to test the following hypotheses: (i) negative selection on worker traits is relaxed relative to negative selection acting on queen traits, and (ii) negative selection is relaxed as a function of social complexity in insects.

2. Material and methods

(a). Population genomics data

We used published datasets for 49 A. mellifera scutellata workers [10,39], 10 B. impatiens drones [12], 10 P. dominula workers [11] and 40 S. invicta males [32]; these datasets were derived from paired-end Illumina genome sequencing. While the honeybee A. mellifera is sometimes assumed to be domesticated, we note that prior population genetic analyses do not provide any evidence for a ‘domestication bottleneck’ [40,41] and, for the analysis here, we purposefully chose a sample of pure bees from Africa—a population that is rarely used for commercial beekeeping [10]. We used a bioinformatics pipeline to detect single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) using GATK 3.8 (modules used: HaplotypeCaller to obtain gvcf files from bam files, GenotypeGVCFs to merge gvcf files, SelectVariants to select SNPs, VariantFiltration to mask and filter out indels and ambiguous sites) [42]. We used GATK 3.8's filter recommendations to remove sites with low quality (50 < QUAL < 5000; 2 < QD < 40) and depth (SNPs are within 1.5× of interquartile range for depth). Tri-allelic sites were also removed for this analysis. After variant calling, we used SnpEff [43] to annotate SNPs as: 0-fold, 4-fold, 5′ UTR, 3′ UTR, intronic or intergenic. Genes with warning for incomplete transcripts, no start codon or multiple stop codons were removed.

(b). Analyses of negative selection

We used the distribution of fitness effects method in DFE-Alpha to estimate the proportion of sites experiencing negative selection [44]. This analysis only requires within-species polymorphism data, and our analysis was carried out independently for honeybees, bumblebees, paper wasps and fire ants. To reduce the impact of demography on population genetic inference, we used DFE-Alpha's recommendation of conducting a modelling run on the neutral (i.e. fourfold synonymous mutations) site frequency spectrum to estimate demographic and mutation parameters first, before running the entire dataset to estimate negative selection using the demographic and mutation parameters estimated from the first run [44]. This process proceeded independently for each species. We used SnpEff's annotations to determine fourfold synonymous SNPs used as a benchmark for neutrally evolving regions in DFE-Alpha. As recommended, we used the folded allele spectrum for our analysis [44] to estimate the proportion of sites under different bins of negative selection. The folded site frequency spectrum represents the distribution of counts of minor alleles for each dataset calculated over all segregating sites (i.e. the number of sites with 1, 2, 3, 4, etc. minor alleles). For the analysis presented in figure 3, we obtained estimates of the proportion of 0-fold sites experiencing strong negative selection from published data for Halictus scabiosae, Messor barbarus, Reticulitermes grassei, Culex pipiens, Melitaea cinxia and Drosophila melanogaster [25,45]; these estimates were also derived from DFE-Alpha using the same approach as we used for Apis, Bombus, Polistes and Solenopsis.

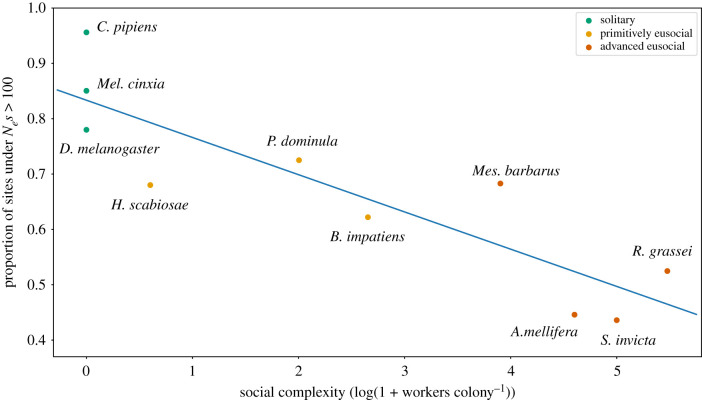

Figure 3.

Social complexity predicts the strength of negative selection in insects. We found a significant association between social complexity and the proportion of 0-fold sites under strong negative selection in 10 insect species after correcting for phylogeny. (Online version in colour.)

(c). Caste-biased genes

Similar to other studies of molecular evolution in social insects [10–12], we used gene expression datasets to define caste-biased genes (i.e. genes that are upregulated in specific castes). We directly used published lists of differentially expressed genes or proteins in queens versus workers that are significant after correcting for multiple testing (false discovery rate (FDR) < 5%) for B. impatiens [12], P. dominula [11], S. invicta [46] and A. mellifera [47]. We also analysed two A. mellifera RNAseq datasets to identify queen-biased and worker-biased genes, as these two studies did not publish such lists as supplementary data [48,49]. For these two datasets, we generated caste-biased gene lists using DESeq2 [50], and we included any gene in the analysis with greater than 14 reads across all samples and used un-normalized counts following standard practices [50]. Genes were considered differentially expressed if their log2 fold change was greater than 1 and their FDR (Benjamini–Hochberg)-corrected p-value was less than 0.05.

(d). Statistical analyses

Most statistical analyses were performed using Scipy.stats in Python [51]. Following established methods [36], we bootstrapped the results of DFE-Alpha 5000 times to generate 95% confidence intervals to carry out statistical comparisons. When comparing DFE-Alpha estimates of negative selection between groups, we first subtracted the means of the two groups for each bootstrap run, and then estimated the 95% confidence interval for differences in bootstrapped means [52]; differences in means were deemed significant if the 95% confidence interval of the bootstrapped mean differences does not contain zero [52].

For studying the relationship between social complexity and the strength of negative selection, we used previously published information on colony sizes of social species (electronic supplementary material, table S1), and corrected for the effect of phylogeny using the method of phylogenetically independent contrasts [53] as implemented using the function pic in the R [54] package phytools [55]. To do so, we constructed a phylogeny for all 10 taxa using eight single-copy orthologous nuclear genes from OrthoDB [56]: Cdc37 (FBgn0011573), mEFG1 (FBgn0263133), hh (FBgn0004644), exd (FBgn0000611), Hsc70Cb (FBgn0026418), Hr39 (FBgn0261239), CG5504 (FBgn0002174), and wls (FBgn0036141). Amino acid sequences for these genes in the 10 species were aligned using PRANK [57] and the resulting alignments were used to construct a phylogenetic tree based on maximum likelihood as implemented in MEGA [58]; both analyses were carried out using default parameters. We carried out the phylogenetically independent contrasts analysis using both raw proportion data (r2 = 0.561; p = 0.02) and arcsine-transformed proportion data (r2 = 0.552; p = 0.02); both analyses were consistent and statistically significant.

3. Results

(a). Patterns of negative selection in eusocial genomes

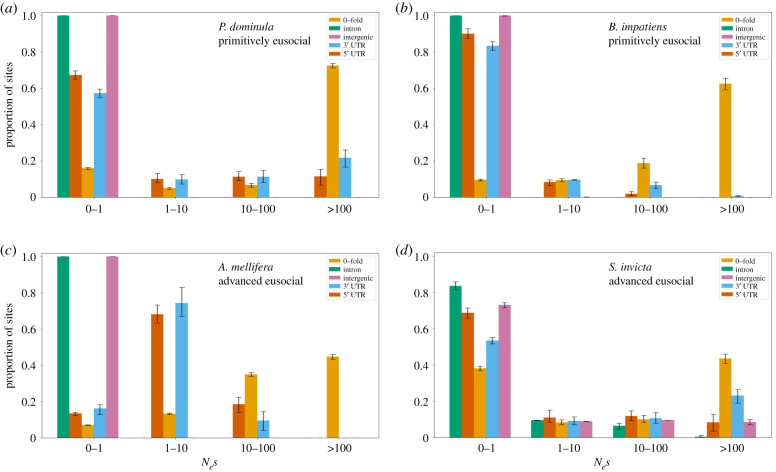

We used previously published population genomic datasets for A. mellifera [10], B. impatiens [12], P. dominula [11] and S. invicta [32] to estimate the strength of negative selection at 0-fold, 5′ UTRs, 3′ UTRs, intronic and intergenic sites; overall, our dataset included mutations in the vast majority of annotated genes in these four species (N = 19 855 for fire ants, 10 662 for honeybees, 14 794 for bumblebees and 11 768 for paper wasps). We used data from fully degenerate fourfold sites as a neutral benchmark. The strength of negative selection was estimated as a categorical variable with the following bins: effectively neutral evolution (Nes = 0–1), weak (Nes = 1–10), moderate (Nes = 10–100) and strong negative selection (Nes > 100). Consistent with Drosophila and human genomes [34,45,59], we found that 0-fold sites experienced the strongest negative selection in all four eusocial species (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, table S2). Polistes dominula (figure 1a) had 72% of their 0-fold sites under strong negative selection (Nes > 100), followed by B. impatiens (62%, figure 1b), A. mellifera (44%, figure 1c) and S. invicta (43%, figure 1d). All species experienced some level of negative selection on 5′ UTRs and 3′ UTRs (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, table S2). Intronic and intergenic sites evolved neutrally in most species expect for S. invicta, where 20–25% of these sites experienced some form of negative selection (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Negative selection in four eusocial insect genomes. The strength of negative selection (Nes) in P. dominula (a), B. impatiens (b), A. mellifera (c), and S. invicta (d) at intergenic, intronic, 5′ and 3′ UTR, and 0-fold sites. Nes bins of 0–1 represent effectively neutral evolution, 1–10 represent weak negative selection, 10–100 represent moderate negative selection and greater than 100 represent strong negative selection. The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval of the means obtained using bootstrapping. (Online version in colour.)

(b). Negative selection on queens versus workers

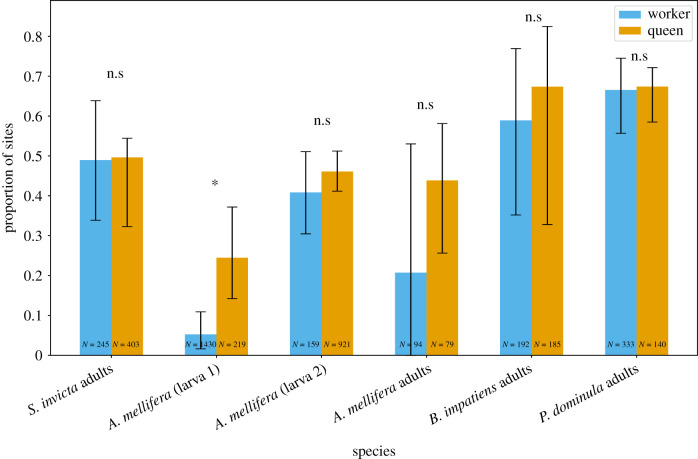

We tested the hypothesis that genes upregulated in queens (i.e. queen-biased genes) experience stronger negative selection compared to genes that are upregulated in workers (i.e. worker-biased genes) because selection acts on the former directly but on the latter indirectly [21]. We tested this hypothesis using three published expression datasets from honeybees and one each for bumblebees, paper wasps and fire ants. Across all but one of the datasets, we found no evidence of relaxed selection on worker-biased genes (figure 2; electronic supplementary material, table S3). This included comparisons of adult fire ants [46], adult and larval (L2 + L4) honeybees [47,49], adult bumblebees [60] and adult paper wasps [61]. Only a single dataset was consistent with the hypothesis: in honeybee L4 larvae [48], the proportion of 0-fold sites in queen-biased genes with strong negative selection was significantly higher relative to worker-biased genes (figure 2; electronic supplementary material, table S3).

Figure 2.

Caste expression does not lead to a relaxation of negative selection on workers under most circumstances. Estimates of strong negative selection (Nes > 100) at 0-fold sites in queen-biased and worker-biased genes. The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval of the means, obtained using bootstrapping. n.s. and * indicate non-significant, or significant differences in means between queens and workers, respectively. N indicates number of differentially expressed genes for each caste for each study. (Online version in colour.)

(c). Social complexity predicts relaxed constraint in insects

Social complexity was associated with relaxed negative selection in all four species. For example, the species with the greatest caste divergence and the largest colonies (S. invicta) had the smallest proportion of 0-fold sites under strong negative selection (43.5% [42.6–45.9%]), while the species with the least caste divergence and smallest colonies (P. dominula) had the highest proportion of 0-fold sites (72.5% [71.2–73.8%]) experiencing strong negative selection (figure 1). To further explore the hypothesis that social complexity impacts the strength of negative selection, we supplemented our data with published estimates of negative selection on 0-fold sites from three additional eusocial insects [25]: the sweat bee H. scabiosae, the harvester ant Mes. barbarus and the termite R. grassei, and three solitary insects [25,45]: the common house mosquito C. pipiens, the glanville fritillary Mel. cinxia and the fruit fly D. melanogaster. For each species, we developed the following parameter as a proxy for social complexity: log10(1 + no. workers colony−1). Solitary insects thereby have a score of zero and increasingly positive values indicate eusocial species with increasingly larger colonies. We then asked if increasing social complexity leads to a relaxation of strong negative selection on 0-fold sites. After correcting for phylogeny, we found a significant negative correlation between social complexity and the proportion of 0-fold sites experiencing strong negative selection (figure 3, r2 = 0.561; p = 0.02).

4. Discussion

We used an allele frequency spectrum approach to quantify the strength of negative selection acting on several insect genomes to understand how eusociality influences patterns of molecular evolution. We first tested the hypothesis that indirect selection on worker phenotypes is less efficient than direct selection on queen phenotypes [21]. Following previous studies [11,12], we used published RNA and protein expression datasets to define sets of genes that are upregulated in workers (worker-biased) relative to queens, and vice versa (i.e. queen-biased). Despite adequate power to detect predicted differences between queen-biased and worker-biased genes (electronic supplementary material, table S4), we did not find strong support for this hypothesis (figure 2; electronic supplementary material, table S3), with only one out of six expression datasets showing a pattern that is consistent with relaxed negative selection on worker-biased genes. We found evidence of weaker indirect selection on worker-biased genes only in L4 larvae in honeybees. Caste differences in the strength of negative selection were not prevalent in primitively eusocial bumblebees and paper wasps (figure 2), which is perhaps not surprising given that: (i) workers in both species contribute to the production of males, (ii) worker Polistes retain the ability to mate and produce daughters, and (iii) relaxed selection on alleles with indirect effects on siblings are less pronounced in monandrous versus polyandrous species [21]. The paper wasp, bumblebee and fire ant studied herein all have an effective mating number of approximately 1 (i.e. monandrous), while honeybees are highly polyandrous [62]. It is important to note that the prediction of relaxed negative selection on worker-biased versus queen-biased genes only holds assuming ‘all else being equal’ [21]. It is possible that this assumption—queen-biased and worker-biased genes are essentially equivalent with the exception of their effect (direct versus indirect, respectively)—rarely occurs in social insects, or that it only transiently occurs during specific developmental stages. As such, it may be operationally difficult to test this hypothesis, especially in eusocial species where workers can produce haploid sons, thereby allowing selection to act directly on their traits under some circumstances.

Next, we tested the hypothesis that eusocial complexity is correlated with patterns of relaxed negative selection [22–24]. The effective population size is a key parameter that influences the strength of genetic drift, which, in turn, influences the ability of natural selection to fix beneficial alleles and remove deleterious ones [30]. In social insects, it is the number of reproductives that influences Ne. For example, consider a colony of 40 000–80 000 honeybees; such a colony requires a tremendous amount of environmental resources but only contains a single queen and a few hundred drones. Assuming a finite carrying capacity, we would expect eusocial species with large colony sizes to have relatively lower effective population size than eusocial species with small colony sizes. Our analysis of fire ants, honeybees, bumblebees and paper wasps was consistent with this hypothesis. Fire ants have the largest colony sizes but experienced the weakest negative selection on 0-fold sites, while paper wasps had the smallest colony sizes but experienced the strongest negative selection on 0-fold sites.

We supplemented our analysis with comparable estimates of negative selection on 0-fold sites from three additional eusocial species and three solitary species. To study how eusociality influences the strength of negative selection, we needed an appropriate metric to capture differences in social behaviour and complexity across all 10 insect species. A recent categorical scale was proposed for comparative analyses of solitary and social species [15] with values ranging from 0 to 3: 0 indicates solitary behaviour, while 1–3 indicate increasing complex eusocial societies. However, this scale does not directly capture the importance of colony size to social complexity [63], which is of primarily interest in our study. We, therefore, decided to quantify social complexity as log(1 + no. workers colony−1). This scale is intuitive and quantitative: solitary species have a score of zero and social species with larger colonies score higher than species with smaller colonies. We found a strong negative association between our measure of social complexity and the proportion of 0-fold sites experiencing strong purifying selection. While correlation does not imply causation, our results are consistent with the hypothesis that sociality reduces Ne [22–29], and the well-established relationship between reductions in Ne and a genome-wide relaxation of selection [19,20,24,64]. Interestingly, there appears to be an association between recombination and social complexity; advanced eusocial insects tend to have higher rates of recombination relative to solitary insects [18,65,66]. The causes of this association have yet to be discovered, but—all other factors being equal—higher recombination is expected to enhance the efficiency of negative selection [67]. Unfortunately, we lacked estimates of cross-over rates for the vast majority of species in figure 3 to jointly estimate the effects of social complexity and recombination rate on negative selection. However, we note that the observed negative association between social complexity and relaxed selection on 0-fold sites (figure 3) may have actually been larger if recombination rates did not positively covary with social complexity.

While there has been much interest in quantifying patterns of molecular evolution that led to the rise of eusociality in insects, we know little about how eusociality can ‘feed back’ to alter patterns of molecular and genome evolution. We uncovered a close relationship between social complexity and relaxed negative selection—a phenomenon that is believed to be key for the evolution of phenotypic plasticity in social insects [68] and other organisms [69]. Going forward, it will be increasingly important to disentangle the genomic changes underlying the evolution of sociality, from those caused by social evolution via its influence on Ne. Moreover, it will be interesting to study how relaxed selection could have contributed to the elaboration of sociality following the evolution of caste.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Robert J. Williamson and Pablo Cingolani for assistance with using DFE-Alpha and SnpEff, respectively, and Eyal Privman and Brendan Hunt for providing advice on relevant fire ant datasets. Harshilkumar Patel and Stephen A. Rose provided support in implementing the bootstrap analysis. Clement Kent provided advice on quantifying social complexity.

Data accessibility

We used previously published and deposited genomic and transcriptomic data. Refer to articles cited herein for data accession numbers.

Authors' contributions

M.A.I. and A.Z. designed the research. K.A.D. and B.A.H. provided datasets. M.A.I., K.A.D., B.A.H. and A.Z. performed the analyses. M.A.I. and A.Z. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

Our study was funded by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and a York University Research Chair in Genomics to A.Z.

References

- 1.Wilson EO, Holldobler B. 2005. Eusociality: origin and consequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 13 367–13 371. ( 10.1073/pnas.0505858102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batra S. 1966. Nests and social behavior of halictine bees of India (Hymenoptera: Halictidae). Indian J. Entomol. 28, 375–393. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michener C. 1969. Comparative social behavior of bees. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 14, 299–342. ( 10.1146/annurev.en.14.010169.001503) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson EO. 1971. The insect societies. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton WD. 1964. The genetical evolution of social behavior I. J. Theor. Biol. 7, 1–16. ( 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton WD. 1964. The genetical evolution of social behavior II. J. Theor. Biol. 7, 17–52. ( 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90039-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strassmann JE, Page RE, Robinson GE, Seeley TD. 2011. Kin selection and eusociality. Nature 471, E5–E6. ( 10.1038/nature09833) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbot P, et al. 2011. Inclusive fitness theory and eusociality. Nature 471, E1–E4; author reply E9–10 ( 10.1038/nature09831) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowak MA, Tarnita CE, Wilson EO. 2010. The evolution of eusociality. Nature 466, 1057–1062. ( 10.1038/nature09205) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harpur BA, Kent CF, Molodtsova D, Lebon JMD, Alqarni AS, Owayss AA, Zayed A. 2014. Population genomics of the honey bee reveals strong signatures of positive selection on worker traits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 2614–2619. ( 10.1073/pnas.1315506111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dogantzis KA, Harpur BA, Rodrigues A, Beani L, Toth AL, Zayed A. 2018. Insects with similar social complexity show convergent patterns of adaptive molecular evolution. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–8. ( 10.1038/s41598-018-28489-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harpur BA, Dey A, Albert JR, Patel S, Hines HM, Hasselmann M, Packer L, Zayed A. 2017. Queens and workers contribute differently to adaptive evolution in bumble bees and honey bees. Genome Biol. Evol. 9, 2395–2402. ( 10.1093/gbe/evx182) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallberg A, et al. 2014. A worldwide survey of genome sequence variation provides insight into the evolutionary history of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Nat. Genet. 46, 1081–1088. ( 10.1038/ng.3077) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodard SH, Fischman BJ, Venkat A, Hudson ME, Varala K, Cameron SA, Clark AG, Robinson GE. 2011. Genes involved in convergent evolution of eusociality in bees. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 7472–7477. ( 10.1073/pnas.1103457108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapheim KM, et al. 2015. Genomic signatures of evolutionary transitions from solitary to group living. Science 348, 1139–1143. ( 10.1126/science.aaa4788) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warner MR, Mikheyev AS, Linksvayer TA. 2017. Genomic signature of kin selection in an ant with obligately sterile workers. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1780–1787. ( 10.1093/molbev/msx123) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubenstein DR, et al. 2019. Coevolution of genome architecture and social behavior. Trends Ecol. Evol. 34, 844–855. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2019.04.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kent CF, Zayed A. 2013. Evolution of recombination and genome structure in eusocial insects. Commun. Integr. Biol. 6, e22919 ( 10.4161/cib.22919) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch M, Conery JS. 2003. The origins of genome complexity. Science 302, 1401–1404. ( 10.1126/science.1089370) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch M. 2007. The origins of genome architecture. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linksvayer TA, Wade MJ. 2009. Genes with social effects are expected to harbor more sequence variation within and between species. Evolution 63, 1685–1696. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00670.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crozier RH. 1971. Heterozygosity and sex determination in haplodiploidy. Am. Nat. 105, 399–412. ( 10.1086/282733) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crozier RH. 1977. Evolutionary genetics of the hymenoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 22, 263–288. ( 10.1146/annurev.en.22.010177.001403) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pamilo P, Crozier RH. 1997. Population biology of social insect conservation. Mem. Mus. Vic. 56, 411–419. ( 10.24199/j.mmv.1997.56.32) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romiguier J, et al. 2014. Population genomics of eusocial insects: the costs of a vertebrate-like effective population size. J. Evol. Biol. 27, 593–603. ( 10.1111/jeb.12331) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crozier RH. 1979. Genetics of sociality. In Social insects (ed. Hermann HR.), pp. 223–286. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedrick PW, Parker JD. 1997. Evolutionary genetics and genetic variation of haplodiploids and X-lined genes. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 28, 55–83. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.55) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nomura T, Takahashi J. 2012. Effective population size in eusocial Hymenoptera with worker-produced males. Heredity (Edinb.) 109, 261–268. ( 10.1038/hdy.2012.11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harpur BA, Smith NMA. 2017. Digest: gene duplication and social evolution: using big, open data to answer big, open questions. Evolution 71, 2952–2953. ( 10.1111/evo.13390) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura M. 1985. The neutral theory of molecular evolution. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kent CF, Zayed A. 2015. Population genomic and phylogenomic insights into the evolution of physiology and behaviour in social insects. Adv. Insect Physiol. 48, 293–324. ( 10.1016/bs.aiip.2015.01.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Privman E, Cohen P, Cohanim AB, Riba-Grognuz O, Shoemaker DW, Keller L. 2018. Positive selection on sociobiological traits in invasive fire ants. Mol. Ecol. 27, 3116–3130. ( 10.1111/mec.14767) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elyashiv E, Sattath S, Hu TT, Strutsovsky A, Mcvicker G, Andolfatto P, Coop G, Sella G. 2016. A genomic map of the effects of linked selection in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006130 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006130) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyko AR, et al. 2008. Assessing the evolutionary impact of amino acid mutations in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000083 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000083) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lafon-Placette C, et al. 2018. Changes in the epigenome and transcriptome of the poplar shoot apical meristem in response to water availability affect preferentially hormone pathways. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 537–551. ( 10.1093/jxb/erx409) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williamson RJ, Josephs EB, Platts AE, Hazzouri KM, Haudry A, Blanchette M, Wright SI. 2014. Evidence for widespread positive and negative selection in coding and conserved noncoding regions of Capsella grandiflora. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004622 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004622) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chun S, Fay JC. 2009. Identification of deleterious mutations within three human genomes. Genome Res. 19, 1553–1561. ( 10.1101/gr.092619.109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris K, Nielsen R. 2016. The genetic cost of Neanderthal introgression. Genetics 203, 881–891. ( 10.1534/genetics.116.186890) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallberg A, Schoning C, Webster MT, Hasselmann M. 2017. Two extended haplotype blocks are associated with adaptation to high altitude habitats in East African honey bees. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006792 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006792) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harpur BA, Minaei S, Kent CF, Zayed A. 2012. Management increases genetic diversity of honey bees via admixture. Mol. Ecol. 21, 4414–4421. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05614.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harpur BA, Minaei S, Kent CF, Zayed A. 2013. Admixture increases diversity in managed honey bees. Reply to De la Rúa et al. (2013). Mol. Ecol. 22, 3211–3215. ( 10.1111/mec.12332) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKenna A, et al. 2010. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303. ( 10.1101/gr.107524.110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang LL, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, Land SJ, Lu X, Ruden DM. 2012. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff. Fly 6, 80–92. ( 10.4161/fly.19695) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keightley PD, Eyre-Walker A. 2007. Joint inference of the distribution of fitness effects of deleterious mutations and population demography based on nucleotide polymorphism frequencies. Genetics 177, 2251–2261. ( 10.1534/genetics.107.080663) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kousathanas A, Keightley PD. 2013. A comparison of models to infer the distribution of fitness effects of new mutations. Genetics 193, 1197–1208. ( 10.1534/genetics.112.148023) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chandra V, Fetter-Pruneda I, Oxley PR, Ritger AL, Mckenzie SK, Libbrecht R, Kronauer DJC. 2018. Social regulation of insulin signaling and the evolution of eusociality in ants. Science 361, 398–402. ( 10.1126/science.aar5723) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan QW, Chan MY, Logan M, Fang Y, Higo H, Foster LJ. 2013. Honey bee protein atlas at organ-level resolution. Genome Res. 23, 1951–1960. ( 10.1101/gr.155994.113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He XJ, Jiang WJ, Zhou M, Barron AB, Zeng ZJ. 2019. A comparison of honeybee (Apis mellifera) queen, worker and drone larvae by RNA-Seq. Insect Sci. 26, 499–509. ( 10.1111/1744-7917.12557) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ashby R, Foret S, Searle I, Maleszka R. 2016. MicroRNAs in honey bee caste determination. Sci. Rep. 6, 18794 ( 10.1038/srep18794) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 ( 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Virtanen P, et al. In press. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Meth. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Whitlock MC, Schluter D. 2015. Analysis of biological data. Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts and Company Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Felsenstein J. 1985. Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am. Nat. 125, 1–15. ( 10.1086/284325) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.R Development Core Team, 2019. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; See https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Revell LJ. 2012. phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 217–223. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00169.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kriventseva EV, Kuznetsov D, Tegenfeldt F, Manni M, Dias R, Simão FA, Zdobnov EM. 2019. OrthoDB v10: sampling the diversity of animal, plant, fungal, protist, bacterial and viral genomes for evolutionary and functional annotations of orthologs. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D807–D811. ( 10.1093/nar/gky1053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loytynoja A, Goldman N. 2010. webPRANK: a phylogeny-aware multiple sequence aligner with interactive alignment browser. BMC Bioinf. 11, 579 ( 10.1186/1471-2105-11-579) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739. ( 10.1093/molbev/msr121) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halligan DL, Kousathanas A, Ness RW, Harr B, Eöry L, Keane TM, Adams DJ, Keightley PD. 2013. Contributions of protein-coding and regulatory change to adaptive molecular evolution in murid rodents. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003995 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003995) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woodard SH, Bloch GM, Band MR, Robinson GE. 2014. Molecular heterochrony and the evolution of sociality in bumblebees (Bombus terrestris). Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20132419 ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.2419) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Standage DS, Berens AJ, Glastad KM, Severin AJ, Brendel VP, Toth AL. 2016. Genome, transcriptome and methylome sequencing of a primitively eusocial wasp reveal a greatly reduced DNA methylation system in a social insect. Mol. Ecol. 25, 1769–1784. ( 10.1111/mec.13578) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strassmann J. 2001. The rarity of multiple mating by females of social Hymenoptera. Insectes Soc. 48, 1–13. ( 10.1007/PL00001737) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bourke AF. 1999. Colony size, social complexity and reproductive conflict in social insects. J. Evol. Biol. 12, 245–257. ( 10.1046/j.1420-9101.1999.00028.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hartl DL, Clark AG. 2007. Principles of population genetics, 4th edn Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kent CF, Minaei S, Harpur BA, Zayed A. 2012. Recombination is associated with the evolution of genome structure and worker behavior in honey bees. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18 012–18 017. ( 10.1073/pnas.1208094109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilfert L, Gadau J, Schmid-Hempel P. 2007. Variation in genomic recombination rates among animal taxa and the case of social insects. Heredity 98, 189–197. ( 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800950) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hill W, Robertson A. 1966. The effect of linkage on limits to artificial selection. Genet. Res. 8, 269–294. ( 10.1017/S0016672300010156) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hunt BG, Ometto L, Wurm Y, Shoemaker D, Yi SV, Keller L, Goodisman MAD. 2011. Relaxed selection is a precursor to the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 15 936–15 941. ( 10.1073/pnas.1104825108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Snell-Rood EC, Van Dyken JD, Cruickshank T, Wade MJ, Moczek AP. 2010. Toward a population genetic framework of developmental evolution: the costs, limits, and consequences of phenotypic plasticity. Bioessays 32, 71–81. ( 10.1002/bies.200900132) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

We used previously published and deposited genomic and transcriptomic data. Refer to articles cited herein for data accession numbers.