Abstract

Forest declines caused by climate disturbance, insect pests and microbial pathogens threaten the global landscape, and tree diseases are increasingly attributed to the emergent properties of complex ecological interactions between the host, microbiota and insects. To address this hypothesis, we combined reductionist approaches (single and polyspecies bacterial cultures) with emergentist approaches (bacterial inoculations in an oak infection model with the addition of insect larvae) to unravel the gene expression landscape and symptom severity of host–microbiota–insect interactions in the acute oak decline (AOD) pathosystem. AOD is a complex decline disease characterized by predisposing abiotic factors, inner bark lesions driven by a bacterial pathobiome, and larval galleries of the bark-boring beetle Agrilus biguttatus. We identified expression of key pathogenicity genes in Brenneria goodwinii, the dominant member of the AOD pathobiome, tissue-specific gene expression profiles, cooperation with other bacterial pathobiome members in sugar catabolism, and demonstrated amplification of pathogenic gene expression in the presence of Agrilus larvae. This study highlights the emergent properties of complex host–pathobiota–insect interactions that underlie the pathology of diseases that threaten global forest biomes.

Keywords: acute oak decline, Brenneria goodwinii, pathobiome, Agrilus biguttatus, Gibbsiella quercinecans

1. Introduction

Global forests provide essential ecological, economic and cultural services, but their capacity for carbon storage and climate regulation is increasingly threatened by altered climatic conditions and increased attack by pests and pathogens [1,2]. In recent decades, devastating outbreaks of tree disease such as chestnut blight [3], Dutch elm disease [4], and ash dieback [5], have changed the global landscape, and tree pests and diseases therefore represent a major future threat to forest biomes. Such diseases often involve the activity of both insect pests and microbial pathogens, and ultimately arise from complex interactions between the host, environment, pests and pathogens [6–8].

Acute oak decline (AOD) is a complex decline disease mediated by abiotic predisposing factors (temperature, rainfall, nutrients) [9] and biotic contributing factors (insect and bacterial) [8] that are a major threat to native oak in the UK, with similar declines described in continental Europe [10–12], Asia [13] and America [14]. The characteristic disease symptoms are outer bark cracks with dark exudates (bleeds), which overlie necrotic tissue in the inner bark, and larval galleries and exit holes of the two-spotted buprestid beetle Agrilus biguttatus [10]. Previously, we demonstrated that tissue necrosis on AOD affected trees is caused by a polybacterial complex (pathobiome) which macerates pectin connective tissue within the cells, resulting in inner bark lesions on oak stems [8,15]. The pathobiome is a complex assemblage of organisms that combine to cause disease in host organisms and challenge strict adherence to Koch's postulates [16]. It has previously been shown that AOD is not caused by a single pathogen, but results from interactions between the pathobiome, A. biguttatus, the host and its environment [8]. Within the AOD pathobiome, several bacteria are consistently identified, primarily Brenneria goodwinii, Gibbsiella quercinecans, Rahnella victoriana, and occasionally, Lonsdalea britannica.

Brenneria goodwinii is the most active member of the lesion pathobiome and is thought to be the primary agent of bacterial canker in AOD [8,15]. Agrilus larvae are also associated with AOD lesions, and spread necrogenic members of the pathobiome through the inner bark tissue, amplifying the area of tissue necrosis in the inner bark [8].

Unravelling the mechanistic processes and complex multidimensional interactions between the host, environment, insects and the pathobiome that underlie the aetiology of complex tree diseases is challenging, but represents a major knowledge gap. Considering pathobiome virulence as an emergent property [17], where emerging properties cannot be explained by their individual components and are greater than the sum of their individual components, is therefore an attractive framework in conceptualising complex tree diseases. Here, we hypothesize that host–microbiota–insect interactions combine to cause emergent properties of pathobiome virulence in AOD. To investigate this, we combined reductionist approaches (interactions with oak tissue in single and polyspecies bacterial culture) with emergentist approaches (bacterial inoculations in an oak infection model with the addition of insect larvae) to unravel the gene expression landscape of host–microbiota–insect interactions in the AOD pathosystem.

2. Results and discussion

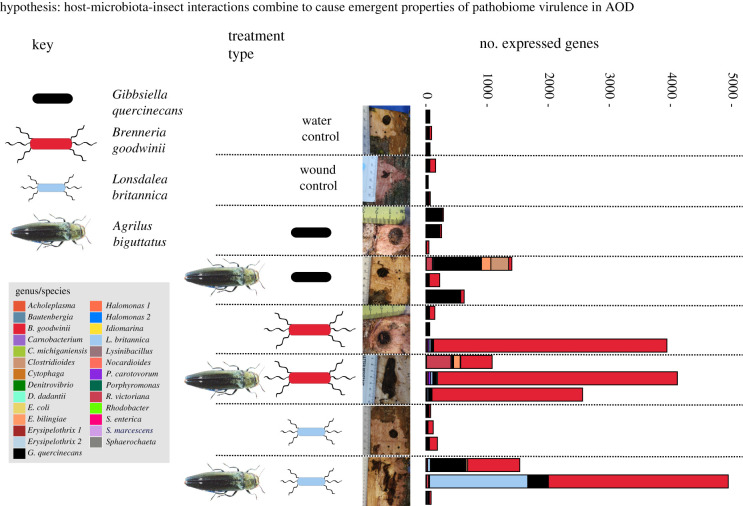

(a). Inoculation of B. goodwinii, G. quercinecans and L. britannica onto oak logs with A. biguttatus eggs

Oak logs were inoculated with either B. goodwinii, G. quercinecans or L. britannica (single, bacteria-only treatments), or in combination with A. biguttatus eggs (single bacterial species plus Agrilus treatments) (i.e. six treatments). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of the resultant stem lesions (or ‘clean’ stem tissue, for control treatments) revealed that apart from host genes, B. goodwinii genes were the most actively expressed among the bacterial species tested (figure 1 and electronic supplementary material, table S1), concurring with previous results [8,15]. The complete genome of B. goodwinii FRB141 contains 4869 genes and the highest levels of B. goodwinii gene activity in the log infection tests were detected in treatments where B. goodwinii was co-inoculated with A. biguttatus eggs (515, 3924 and 2464 genes expressed in each replicate, respectively) and there was positive detection of B. goodwinii via quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (see Methods for our definition of active genes briefly, these are genes which were not differentially expressed, but were deemed ‘active’ as they passed expression filters, e.g. transcripts per million (TPM), but differ from subsequent analyses that focused on differential gene expression). By comparison, only one of the three B. goodwinii only inoculations produced necrosis, with 3819 active genes detected, while the other two inoculations did not show appreciable lesion development and only 88 and 96 active genes were detected.

Figure 1.

Transcriptome analysis of oak log infection tests comprising single bacterial species inoculations and bacteria plus Agrilus biguttatus egg inoculations. From left to right: organisms inoculated into oak logs are shown in the key on the top right, these are Gibbsiella quercinecans, Brenneria goodwinii, Lonsdalea britannica and A. biguttatus. There were three biological replicates of each infection test, including replicate water only and wound controls. Each of the three bacterial species were inoculated individually and in combination with eggs of A. biguttatus. Exemplary pictures of a single log inoculation replicate from each treatment are shown. The number of expressed genes from log inoculations are shown in the bar chart, with each expressed gene aligned against a custom database and colour coded with the genus/species key shown on the bottom left of the figure. Oak transcripts were excluded from the bar chart. (Online version in colour.)

Lesions barely developed in L. britannica inoculations, with low activity (11 ± 3 active genes) detected, although this species was previously isolated from naturally symptomatic material and has the genomic potential to cause tissue necrosis [18]. By comparison, when co-inoculated with A. biguttatus eggs, two of the three inoculations developed dramatic, typical AOD lesions, with 46 and 1607 L. britannica genes active (figure 1), but both B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans were also reisolated via qPCR, and 852 and 2942 B. goodwinii genes and 579 and 320 G. quercinecans genes were found to be active. Notably, G. quercinecans which has been consistently isolated from environmental AOD lesions and can cause necrotic lesions on oak [8], had low activity in log inoculations (143 ± 71 active genes), but had higher gene activity and significant lesion formation when combined with A. biguttatus (444 ± 225).

Thus, with the exception of a single B. goodwinii inoculation, none of the single isolate inoculations created significant lesions or demonstrated high gene expression, which supports our hypothesis that although these organisms can be pathogenic, emergent virulence is dependent upon complex host–pathobiome–insect interactions. However, when co-inoculated with A. biguttatus eggs that developed into larvae, typical AOD symptoms were developed and B. goodwinii gene activity was highly increased. This suggests that the presence of A. biguttatus larvae provides a stimulus for enhanced B. goodwinii pathogenicity. Furthermore, the biggest lesions formed when genes of all three bacterial species were detected. Despite the fact that only single species inoculations were made, the occurrence of B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans in the L. britannica plus Agrilus treatment could be explained either by the bacteria already being present as endosymbionts of the non-symptomatic oak logs, or by them gaining entry through wound inoculations, or that A. biguttatus is a vector of B. goodwinii, either incidentally or that it resides within A. biguttatus as part of the microbiome and is deposited when feeding or egg laying [10]. This suggests that the presence of A. biguttatus larvae provides a stimulus for enhanced B. goodwinii pathogenicity. However, there is no previous evidence showing that A. biguttatus is a vector of B. goodwinii, G. quercinecans or L. britannica and the bacteria-beetle relationship may be as co-infecting agents taking advantage of declining oak trees [19].

Our results demonstrate that the driver of variation between non-symptomatic and symptomatic oak trees was bacterial inoculum (p = 0.031) and the presence of A. biguttatus larvae (p = 0.005) (figure 1). Possible sources of variation in gene activity between symptomatic and non-symptomatic trees were tested in a multivariate model, these were: actual lesion size, presence or absence of A. biguttatus, bacterial inoculum, and between replicate differences. Biological replicates and lesion size did not account for significant variation in gene activity (p > 0.05). Furthermore, differential gene expression analysis revealed that the number of genes expressed in G. quercinecans and L. britannica was relatively small, whereas in B. goodwinii inoculations, a substantial portion of the B. goodwinii geneset (electronic supplementary material table, S2) was differentially expressed. Therefore, the following differential gene expression analysis of B. goodwinii was directly compared against control treatments and B. goodwinii when co-inoculated with A. biguttatus larvae.

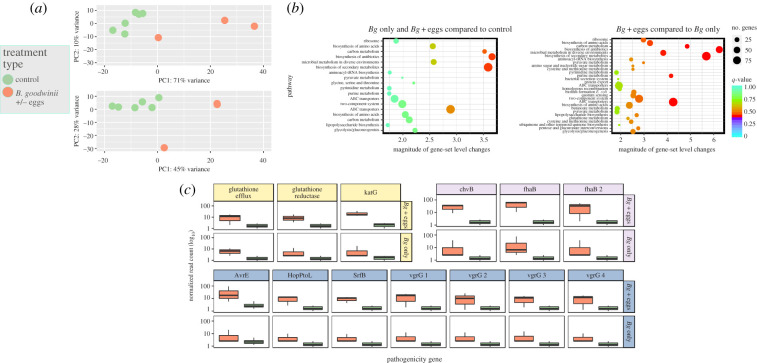

(b). Brenneria goodwinii has a high number of significantly upregulated genes in log inoculations when inoculated with A. biguttatus

Differential gene expression analysis of B. goodwinii log inoculations (bacteria only) compared against wound and water controls revealed 191 genes were significantly differentially upregulated (electronic supplementary material table, S2). Comparison of the B. goodwinii and A. biguttatus treatment with the wound control resulted in 552 upregulated B. goodwinii genes. Variance between expressed genes within transcriptomic datasets was measured using principal component analyses (PCA) (figure 2a). This PCA collapsed 73% of the variance and revealed clear separation between transcript abundance in B. goodwinii infected oak logs compared to the control (figure 2a, bottom). The same pattern was found in B. goodwinii and A. biguttatus inoculated oak logs where 81% of the variance was captured in a PCA and revealed distinct expression patterns in comparison to oak control logs (figure 2a, top). Analysis of differential expression of gene families, revealed significant upregulation of putative pathogenic families in B. goodwinii and A. biguttatus egg inoculations when compared to B. goodwinii only oak logs. These gene families were identified using geneset enrichment analysis and revealed that gene families were upregulated in B. goodwinii by the presence of A. biguttatus eggs. Significantly upregulated functional groups include bacterial pathogenicity homologues, such as bacterial secretion systems (p = 0.04, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) family 03070), terpenoid biosynthesis (p = 0.04, KEGG family 00130), biofilm formation (p = 0.007, KEGG family 02026), and quorum sensing (p = 0.01, KEGG family 02024) (figure 2b). Differential gene expression analysis between oak log incoulations revealed significant upregulation of pathogenicity associated genes in B. goodwinii and A. biguttatus oak logs compared to control, in comparison to differential expression of the same gene in B. goodwinii only oak logs when compared to control. Genes were functionally annotated using homologues in closely related bacteria (see Methods). Significantly upregulated functional homologues included a biofilm formation gene, exoglucanase B – chvB (Padj < 0.0001 in B. goodwinii + A. biguttatus versus healthy, compared to B. goodwinii only versus healthy, which had no p-value owing to low transcript expression), an adherence gene–fhaB (Padj = 0.03 in B. goodwinii + A. biguttatus versus healthy, compared to p = 0.02, N.B. Padj was NA as the mean read count was low in B. goodwinii only versus healthy), poly(β-d-mannuronate) C5 epimerase 1, a biofilm formation and quorum sensing gene - algG (Padj < 0.0001 in B. goodwinii + A. biguttatus versus healthy, compared to Padj = 0.0006 B. goodwinii only versus healthy). Poly(β-d-mannuronate) C5 epimerase 1 is a large, type I secreted adhesion which is found in shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli strains and in disease formation of the bacterial phytopathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum [20,21]. Both exoglucanase B and poly(β-d-mannuronate) C5 epimerase 1 were significantly upregulated in B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans only live log inoculations indicating that A. biguttatus may not be the only stimulus for its expression. The actual stimulus may be carried by A. biguttatus or may reside in the wider environment. Similar to the type I secreted proteins, two copies of the two-partner secreted filamentous haemagglutinin (fhaB), a bacterial virulence gene were expressed by B. goodwinii across live log transcriptomes. As described above, the number of genes expressed in B. goodwinii when A. biguttatus was present was greater than B. goodwinii only inoculations (191 versus 552, respectively), but in addition the number of pathogenic gene homologues expressed increased when A. biguttatus eggs were combined with B. goodwinii (figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Transcriptome analysis of Brenneria goodwinii inoculations on live oak logs. (a) Principal component analysis (PCA) of (top) B. goodwinii (n = 3) compared to control (n = 6); (bottom) B. goodwinii and A. biguttatus compared to control (n = 6). (b) Geneset enrichment analysis (GSEA) of B. goodwinii gene families when compared to (left) water and wound control oak logs; (right) B. goodwinii inoculated in combination with A. biguttatus when compared to B. goodwinii only. The lower q-value represents increased magnitude of gene family expression and circle size represents number of genes per family. (c) Gene expression changes of selected significantly differentially expressed genes, these are anti-toxicity genes (yellow), biofilm and persistence genes (purple), secretion system effectors (blue): (top) B. goodwinii compared to control; (bottom) B. goodwinii and A. biguttatus compared to control. Transcriptome samples were taken from log inoculations of bacterial combinations, wound and water controls, and field samples of AOD lesions and asymptomatic oaks. Bg = Brenneria goodwinii; eggs = A. biguttatus. (Online version in colour.)

The T3SS is a primary virulence factor in seven of the top 10 bacterial plant pathogens [22]. Brenneria goodwinii encodes a complete T3SS and multiple effectors, which is likely to be a key pathogenicity component within AOD tissue necrosis [18]. Within B. goodwinii and A. biguttatus live log inoculations, four T3 effectors are significantly differentially expressed, only one of which is expressed in B. goodwinii only inoculations (figure 2c). Significantly expressed T3 effectors are; HopPtoL (Padj = 0.02), SrfB (Padj = 0.02), AvrE_2 (Padj = 0.015), in addition to AvrE_1 which is significantly differentially expressed in B. goodwinii only and with A. biguttatus inoculations (Padj = 0.04, B. goodwinii inoculation only; Padj = 0.0001, B. goodwinii and A. biguttatus co-infection). The AvrE T3 effector is found in a wide number of bacterial plant pathogens owing to its proclivity for horizontal gene transfer [23]. Notably, within the plant pathogen Pseudomonas viridflava, AvrE is the primary virulence factor [24].

(c). Detoxification genes in B. goodwinii are stimulated by the presence of A. biguttatus, which may neutralize host defences

As described above, co-infection of oak logs with A. biguttatus significantly increases the number of significantly differentially expressed genes within B. goodwinii and stimulates expression of putative pathogen genes. In addition, homologues of genes which neutralize tree defences were expressed. In previous studies, these homologues have been shown to create a desirable environment for pupation and bacterial persistence [25]. The number of significantly differentially expressed genes in B. goodwinii inoculated logs increased from 191 to 552 when A. biguttatus eggs were co-inoculated. Genes upregulated by A. biguttatus eggs and not in B. goodwinii only log inoculations included host defence detoxification genes; catalase peroxidase (Padj < 0.0001; E.C. 1.11.1.21), glutathione reductase (Padj = 0.02; E.C. 1.8.1.7), and glutathione-regulated potassium efflux system (Padj = 0.02). Catalase peroxidase and glutathione reductase are encoded on the same operon; catalase peroxidase (katG) protects against hydrogen peroxide released by host defences [26] and glutathione is a metabolite of isoprene and its derivative terpene, both of which are common in oak trees and used to combat abiotic stress and in high quantities are toxic to bark-boring beetles [7,27,28]. Brenneria goodwinii mediated terpene reduction may exhaust terpene synthesis similar to that of drought stressed oaks which initially produce abundant amounts of terpenes but upon severe drought stress are no longer able to synthesize the volatiles, leaving them open to herbivores [29].

(d). The oak host upregulates more defence-associated genes during co-inoculation with A. biguttatus

Examination of oak host transcripts within infection tests revealed differential gene expression when challenged with B. goodwinii only compared to B. goodwinii with A. biguttatus eggs. This analysis revealed 25 significantly upregulated genes in logs inoculated with B. goodwinii and A. biguttatus eggs compared to 12 upregulated genes with only B. goodwinii. This result provides further evidence of an increase in activity of B. goodwinii when co-infected with A. biguttatus. For both B. goodwinii treatments we discovered the upregulation of genes encoding the calcium sensor protein CML38. This protein, and calcium signalling proteins in general are reportedly induced during wounding, stress and pathogen infection [30,31]. Furthermore, during inoculation with B. goodwinii only, and with G. quercinecans and eggs, there was significant upregulation of a NDR1/HIN1-like protein, which is associated with senescence and pathogen infection [32]. Host genes encoding NDR1/HIN1-like proteins have previously been reported as upregulated when comparing field AOD lesion bark to that from non-symptomatic trees. During inoculation of B. goodwinii and eggs, there was also significant upregulation of two infection-associated genes encoding WUN1, a wound induced protein, and EP3, an endochitinase associated with infection [33–35]. These results support the conclusion that bacterial co-infection with A. biguttatus enhances not only bacterial activity but also overall triggering of host defence-associated genes.

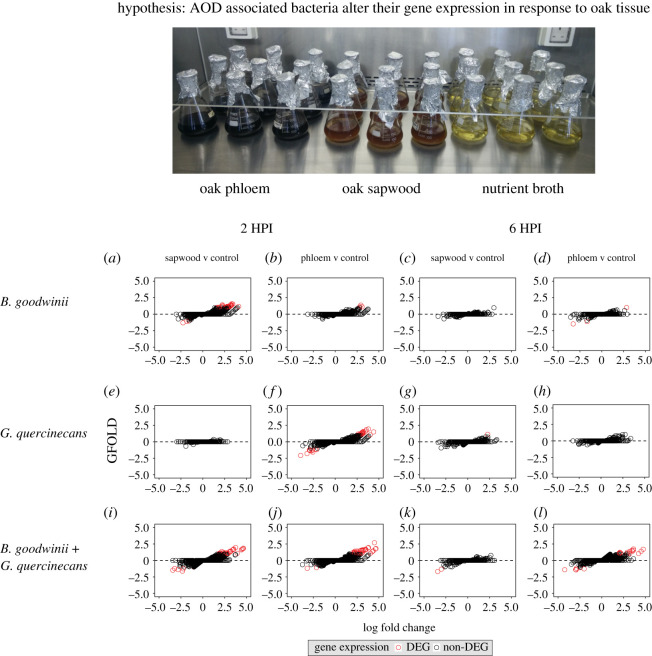

(e). In vitro analysis of the B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans transcriptome response to oak sapwood and phloem tissue

To gain greater understanding of interactions between two key bacteria within the AOD pathobiome, in vitro transcriptome assays were designed to measure gene expression changes of B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans in pure cultures and co-cultures containing oak phloem and sapwood (figure 3 and see Methods for recipe). A key unanswered question in AOD pathology relates to the nature of pathobiome interactions between B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans, and whether they represent competitive or cooperative strategies.

Figure 3.

In vitro transcriptome analysis of Brenneria goodwinii and Gibbsiella quercinecans in nutrient broth supplemented with oak phloem and oak sapwood. Each panel shows gene expression changes when phloem and sapwood are present, compared with nutrient broth only controls. (a) Brenneria goodwinii in sapwood at 2 h post inoculation (HPI). (b) B. goodwinii in phloem at 2 HPI, (c) B. goodwinii in sapwood at 6 HPI, (d) B. goodwinii in phloem at 6 HPI, (d) G. quercinecans in oak sapwood at 2 HPI. (e) G. quercinecans in oak phloem at 2 HPI, (f) G. quercinecans in sapwood at 6 HPI, (g) G. quercinecans in phloem at 6 HPI, (i) B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans in sapwood at 2 HPI, (j) B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans in phloem at 2 HPI, (k) B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans in sapwood at 6 HPI, and (l) B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans in phloem at 6 HPI. DEG = differentially expressed gene. GFOLD is the generalized fold change. (Online version in colour.)

(f). Gene expression of B. goodwinii within phloem and sapwood in vitro cultures varies substantially between single inoculations and co-cultures

Gene expression analysis revealed that B. goodwinii has a substantial transcriptomic response to oak sapwood tissue 2 h post inoculation (HPI), significantly differentially expressing 39 genes (p < 0.05; 35 upregulated and four downregulated) (figure 3a). Upregulated genes were mostly sugar transport/catabolism (n = 11) and general metabolism genes but also included an anti-bacterial gene, the type I secretion protein colicin V (attacks closely related bacteria) [36]. This effect is not found in oak phloem tissue (figure 3b), indicating that B. goodwinii is stimulated by glucose and xylose rich sapwood tissue which it can use as a sugar source.

In co-culture, 2 HPI with G. quercinecans, B. goodwinii significantly differentially expressed genes which were not expressed in axenic B. goodwinii culture (n = 14 in phloem; n = 13 in sapwood) (figure 3i). This response was found in both oak phloem and sapwood tissue (figure 3i–l), with upregulated genes including those associated with sugar depolymerization, which hydrolyse long chain sugar polymers such as α-N-arabinofuranosidae (E.C. 3.2.1.55), bacterial α-l-rhamnosidase (E.C. 3.2.1.40) and β-galactosidase (E.C. 3.2.1.23). These enzymes degrade plant tissue by breaking glycosidic linkages in the pectic polysaccharide, rhamnogalacturonan-II [37] and hemicellulose [38]. In sapwood at 2 HPI (figure 3a), flagellar motility genes (n = 2) were upregulated including the motility regulator fliA [39], indicating that sapwood and G. quercinecans stimulate the flagellar apparatus of B. goodwinii.

(g). Gibbsiella quercinecans has a substantial upregulation of genes towards oak phloem tissue but not sapwood

The environmental reservoir and ecological niche of G. quercinecans is unconfirmed. However, it is a robust bacterium that can survive in harsh environments [40] and is consistently isolated from AOD lesions where it may contribute to tissue necrosis [18]. Evidence provided here reveals that G. quercinecans is differentially stimulated by oak phloem (figure 3f) and may assist B. goodwinii in colonizing this environment by inducing expression of hitherto unexpressed genes (figure 3j,l).

Here, G. quercinecans significantly differentially expressed 42 genes in single inoculations with phloem tissue at 2 HPI (32 upregulated and 10 downregulated) (figure 3f). A large number of upregulated genes are involved in sugar catabolism/transport (n = 10), but also upregulated were general metabolism genes, the type IV secretion system (T4SS) component virB4 and a key PCWDE—rhamnogalacturonan lyase (E.C. 4.2.2.23). The in vitro environment, containing oak phloem and sapwood, may mirror the environmental habitat of G. quercinecans, which has previously been isolated from rotting wood and has many saprophytic properties [18,40].

(h). Sugar consumption by G. quercinecans in oak sapwood is stimulated by B. goodwinii

Compared to axenic growth of G. quercinecans in sapwood (figure 3e,g), co-culture with B. goodwinii induced significant differential expression of 21 genes (14 upregulated and seven downregulated) (figure 3i,k). Upregulated gene function included sugar catabolism/transport (n = 5), iron transporters (n = 3) and two secondary PCWDEs (n = 2). It was anticipated that co-culture could potentially induce expression of anti-bacterial effectors but similar to B. goodwinii in phloem, G. quercinecans catabolizes and transports sugars from sapwood when B. goodwinii is present (figure 3i–l). Despite the encoding of multiple toxin-antitoxin systems and type VI secretion systems, there was no evidence of competitive behaviour between B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans. These are closely related bacteria, isolated from the same environmental niche and these experiments suggest that they assist each other to metabolize oak tissue. Anti-bacterial effectors may be expressed at later stages of co-culture, when resources are reduced, but this was not tested here.

(i). RNA-seq validation using RT-qPCR analysis of G. quercinecans FRB97 and B. goodwinii FRB141 putative pathogenicity genes

Two reverse transcription-qPCR (RT-qPCR) gene expression assays were used to validate RNA-seq data using the same RNA extracts as the in vitro RNA-seq experiment. In G. quercinecans tssD was selected, as homologues of this gene form part of the T6SS injectosome [41], and in B. goodwinii fliA was selected, which is an alternative sigma factor and controls flagella filament synthesis, chemotaxis machinery and motor switch complex genes in E. coli [42].

RT-qPCR assays revealed that gene expression was highest at 6 HPI for tssD (an average of 2.2 × 105 absolute transcript copies at 2 HPI, 3.5 × 106 at 6 HPI, 2.7 × 105 at 12 HPI, 4.1 × 104 at 24 HPI), and 2 HPI for fliA (an average of 5.5 × 104 absolute transcript copies at 2 HPI, 8.7 × 103 at 6 HPI, and 2.6 × 103 at 12 HPI) (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). RNA-seq data revealed high gene expression of fliA in axenic B. goodwinii culture at 2 HPI, and differential upregulation in co-culture with G. quercinecans, in nutrient broth (NB) and sapwood (NBS) and NB and phloem (NBP) cultures at 2 HPI only, with gene expression being suppressed with the addition of G. quercinecans in NB. tssD was highly expressed at 6 HPI, concurring with the RT-qPCR data (electronic supplementary material, figure S1), and was differentially upregulated at 2 HPI in NBS and NBP compared to NB. Within the G. quercinecans transcriptome tssD was upregulated in NBS and NBP, suggesting that it is part of a wider virulence transcription cascade, and may respond to eukaryotic stimuli. Transcriptomic expression data of tssD and fliA, data correlates with the RT-qPCR data, however, small variations may be explained by the high sensitivity of RT-qPCR [43,44].

3. Conclusion

Here we investigated the emergent properties of pathobiome virulence in AOD. We used gene expression analysis of axenic and co-cultures of bacteria supplemented with oak inner bark tissue, and oak infection tests using combinations of the A. biguttatus beetle and microbial pathobionts. We demonstrated that the pathogenic potential of the dominant bacterial species within the AOD lesion pathobiome, B. goodwinii, is stimulated by a co-invading native beetle, A. biguttatus, and also potentially induced by other microorganisms in the AOD pathobiome associated with either the host or A. biguttatus. Furthermore, B. goodwinii genes induced by the presence of A. biguttatus may confer nutrient acquisition benefits to beetle eggs and larvae.

The cooperative behaviour of B. goodwinii and G. quercinecans in a nutrient-rich environment may differ from the AOD lesion environment where resources are scarce. However, both bacteria persisted in oak phloem and sapwood when combined, and when resources were plentiful there was no significant upregulation of interbacterial competition genes. It was also revealed that G. quercinecans favours sugar metabolites from oak phloem tissue, whereas B. goodwinii favours oak sapwood as a carbon source. The role of L. britannica in the lesion environment is unclear but merits further investigation owing to its encoded pathogenic potential and high expression activity in combination with B. goodwinii and A. biguttatus. It is possible that AOD pathobiome constituents each contribute degradative enzymes to systematically macerate oak tissue, thereby cooperating to provide ingestible sugars as a public good. To fully characterize the molecular processes uncovered in this study will require tractable genetic manipulations of single-gene effects in appropriate model systems.

In conclusion, we identified expression of key pathogenicity genes in B. goodwinii, the dominant member of the AOD pathobiome, tissue-specific gene expression profiles, cooperation with other bacterial pathobiome members in sugar catabolism, and demonstrated amplification of pathogenic gene expression in the presence of Agrilus larvae. These data highlight the emergent properties of complex multidimensional interactions between host plants, insects and the microbiome that underpin complex tree decline diseases that threaten the global landscape.

4. Methods

(a). In vitro culture-based assay

(i). Strains, growth medium and conditions

Strains of G. quercinecans FRB97 and B. goodwinii FRB141 were obtained by Forest Research (Surrey, UK) from AOD affected trees. Isolates were maintained on nutrient agar (Oxoid) at room temperature. To simulate growth on sapwood and phloem, cells were cultured in nutrient broth (NB) (Oxoid) containing 1% (w/v) milled sapwood (NBS), NB with 1% (w/v) milled phloem (NBP) and a control consisting of NB. Initially, a 10 ml starter culture from a single colony was incubated overnight to stationary phase at 28°C on a shaking incubator at 100 r.p.m. 1% of the overnight culture, was centrifuged and re-suspended, before addition to three replicate culture flasks containing 150 ml volumes of NB, NBS and NBP (figure 3). The flasks were incubated at 28°C and 100 r.p.m., for 6 HPI, with cell suspensions collected at 2 HPI and 6 HPI. At each time point, 25 ml of liquid was collected in a 50 ml Falcon tube and centrifuged for 5 min at 3000 r.p.m. The supernatant was discarded, and pelleted cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen.

(b). Log infection assay

Log trials were established in 2015 (see the electronic supplementary material, table S3 for list of log inoculation treatments, resultant lesion sizes and further information). Owing to the high cost of transcriptomics when the trial was terminated and samples processed, only a subset of three inoculation points in each of the above described treatments were sampled, at random, from the log test, except where there were exceptional cases of typical AOD lesions, i.e. two Lonsdalea inoculations, which were specifically included in the transcriptomic analyses. Following lesion area measurements and plating lesion margin wood chips [8], the remaining lesion was chiselled out, placed in a labelled ziplock plastic bag and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction took place.

(c). RNA extraction

(i). RNA extraction from bacterial cultures

Total RNA was extracted from cell pellets of bacterial cultures using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), according to manufacturer's instructions. Genomic DNA was removed from extracted RNA samples using a TURBO DNA-free DNase kit (Ambion). Total RNA was pooled from three biological replicates in equimolar quantities giving a total quantity of 750 ng (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Total ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was depleted to enrich messenger RNA (mRNA) (transcripts) using the RiboZero rRNA depletion kit (Illumina). The protocol was performed according to manufacturer's instructions. Depleted mRNA concentrations were measured using a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen). Remnant rRNA was minimal as confirmed by the Centre for Genomic Research (CGR) (University of Liverpool, UK), using the Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer.

(ii). RNA extraction from log inoculations

RNA was extracted from logs using the method described in our previous multi-omic AOD work and described here [45]. Briefly, inner bark around log inoculation spots was scraped off and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Oak tissue was homogenized using a mortar and pestle, and extraction buffer (4 M guanidine thiocyanate, 0.2 M sodium acetate pH 5.0, 25 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 2.5% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone and 1% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol) was added. The frozen tissue in extraction buffer was further ground until thawed, while additional extraction buffer and 20% sodium lauroyl sarcosinate were mixed into the sample. The sample mixture was shaken vigorously at room temperature and further processed using the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen). After centrifugation in the QIAShredder column, 350 µl of the supernatant was mixed with 0.9 volumes of ethanol, and subsequently centrifuged in the RNeasy Mini column. After this centrifugation step, the manufacturer's instructions for the RNeasy Plant Mini kit were followed. The extracted RNA was treated with DNase I (Qiagen) and further concentrated and purified using the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions. The purified RNA was checked for quality using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (LabTech), and the concentration determined using the Qubit RNA HS assay kit (Thermo Fisher) following the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, rRNA was depleted from RNA extracts using a 1 : 1 combination of the Ribo-Zero rRNA removal kits for plant seed/root and for bacteria (Illumina) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The rRNA-depleted samples were again purified using the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup kit (Qiagen) again and stored at −80°C before sequencing.

(d). RNA sequencing

Library preparation, transcriptomic sequencing and post-sequencing quality control (QC) of depleted RNA samples was performed by CGR, University of Liverpool, UK. Samples were assayed for quality using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser. Log infection samples were further assayed for quality using the Eukaryote Total RNA Pico Series II. All libraries were prepared using the strand-specific ScriptSeq kit (Illumina), and subsequently paired-end sequenced (2 × 125 bp) on one lane (note: in vitro and log infection samples were sequenced on separate lanes) of the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (electronic supplementary material, figures S3 and S4).

(e). Transcriptome analysis

(i). RNA-seq quality control

Illumina adapter sequences were removed from raw FastQ files containing the sequencing reads using Cutadapt v. 1.2.1 [46], using the option –O 3, which specifies that at least three base pairs have to match the adapter sequences before they were trimmed. Sequences were quality trimmed using Sickle v. 1.2 [47] with a minimum quality score of 20. Reads shorter than 10 base pairs were removed. RNA-seq QC was performed by CGR, University of Liverpool, UK (electronic supplementary material, figures S3 and S4).

(ii). Bioinformatic analysis of transcriptome data

Bioinformatic analyses were carried out on SuperComputing Wales, an HPC network, using GNU/Linux Red Hat Enterprise Linux Server release 7.4 (Maipo). A complete list of commands used to perform the below analysis is hosted on GitHub (https://github.com/clydeandforth/Bg_Ab_logs.git).

(iii). Transcriptome alignment and differential gene expression analysis

RNA recovered from log inoculations and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq, was aligned using Bowtie2 v. 1.1.2 [48] to an in-house database of structurally and functionally annotated coding regions (electronic supplementary methods) used in a previous field AOD microbiome analysis [15], but with the addition of L. britannica 477. Transcript counts for each gene were calculated using eXpress v. 1.5.1 [49]. To give an overview of species activity in the lesion environment, an active gene was defined as those with TPM greater than 1 and a total transcript count of three. TPM rather than raw read counts was used to normalize the number of transcripts across samples and remove sequencing depth as an experimental artefact. Subsequently, in a separate test, to get a statistically robust understanding of transcriptional activity, significantly differentially expressed genes were identified using DESeq2 v. 1.2 [50]. Genes which had p-adjusted values of less than 0.05 between conditions were considered as significantly differentially expressed. Principal coordinate analyses based on dispersion of mean normalized gene count data between samples was calculated and plotted using DESeq2 v. 1.2.

Geneset enrichment analyses of KEGG pathways were used to measure functional upregulation of gene families between samples using the R packages Gage v. 2.30.0 [51] and clusterProfiler v. 3.8.1 [52]. Gage uses a two sample t-test to compare expression level changes between genesets. KEGG datasets were compiled from KEGGREST v. 1.20.1 (accessed 04 February 2019) and comprised pathways from the following bacteria: Dickeya dadantii 3937, Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum PC1, E. coli K12, E. coli 0157:H7 Sakai, Rahnella aquatilis CIP 78.65, Serratia proteamaculans 568, and plants: Phoenix datylifera, Arabidopsis thaliana, Methylorubrum populi BJ001.

(iv). Multivariate analysis: generalized linear model

To test for biological variation between samples, the effect of inoculum, beetle presence/absence, lesion size and replicate were included in a generalized linear model (GLM) [53]. Normalized read count data produced using eXpress (described below) were set as the multivariate response variable and the biological predictors were fitted using a negative binomial distribution. The ‘manyglm’ function of the R package [54] mvabund [55] was used to carry out the analysis. Inoculum, beetle presence/absence, lesion size, and replicate were included as exploratory variables to allow the model to test our hypotheses.

(v). Transcriptomic analysis of in vitro sequence data

Sequenced RNA from in vitro tests was aligned to a custom database and counted as described above. The TPM counts from eXpress analysis were used to calculate the generalized fold change (GFOLD) [56], which uses the posterior distribution of the raw fold change to calculate differential expression of genes between conditions and is analogous to the p-value in DESeq2. Genes which had GFOLD values greater than 1.5 or less than 1.5 between conditions were considered as significantly differentially expressed.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sarah Plummer and Andrew Griffiths for technical assistance with the log tests, Katy Reed for providing A. biguttatus eggs for the log infection tests, and Jack Foster and Bethany Pettifor for useful suggestions on the manuscript. The authors would also like to thank Supercomputing Wales for their support.

Data accessibility

Sequence data have been deposited in NCBI under BioProject PRJNA369790.

Authors' contributions

J.D. and M.B. carried out the molecular laboratory work, RNA extraction and depletion, statistical and bioinformatic analysis. J.D. drafted the manuscript and created the figures. J.E.M. supervised the laboratory work and critically revised the manuscript. S.D. conducted log tests and critically revised the manuscript. All authors, designed and coordinated the study. All authors gave final approval for publication and agree to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was funded by Woodland Heritage, the Rufford Foundation, the Monument Trust, Forestry Commission and DEFRA; we are grateful for their support.

References

- 1.Bebber DP, Ramotowski MAT, Gurr SJ. 2013. Crop pests and pathogens move polewards in a warming world. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 985–988. ( 10.1038/nclimate1990) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Millar CI, Stephenson NL. 2015. Temperate forest health in an era of emerging megadisturbance. Science 349, 823–826. ( 10.1126/science.aaa9933) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs DF. 2007. Toward development of silvical strategies for forest restoration of American chestnut (Castanea dentata) using blight-resistant hybrids. Biol. Conserv. 137, 497–506. ( 10.1016/j.biocon.2007.03.013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potter C, Harwood T, Knight J, Tomlinson I. 2011. Learning from history, predicting the future: the UK Dutch elm disease outbreak in relation to contemporary tree disease threats. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 366, 1966–1974. ( 10.1098/rstb.2010.0395) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pautasso M, Aas G, Queloz V, Holdenrieder O. 2013. European ash (Fraxinus excelsior) dieback: a conservation biology challenge. Biol. Conserv. 158, 37–49. ( 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.08.026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koskella B, Meaden S, Crowther WJ, Leimu R, Metcalf CJE. 2017. A signature of tree health? Shifts in the microbiome and the ecological drivers of horse chestnut bleeding canker disease. New Phytol. 215, 737–746. ( 10.1111/nph.14560) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams AS, Aylward FO, Adams SM, Erbilgin N, Aukema BH, Currie CR, Suen G, Raffa KF. 2013. Mountain pine beetles colonizing historical and naive host trees are associated with a bacterial community highly enriched in genes contributing to terpene metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 3468–3475. ( 10.1128/AEM.00068-13) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denman S, et al. 2018. Microbiome and infectivity studies reveal complex polyspecies tree disease in acute oak decline. ISME J. 12, 386–399. ( 10.1038/ismej.2017.170) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown N, Vanguelova E, Parnell S, Broadmeadow S, Denman S. 2018. Predisposition of forests to biotic disturbance: predicting the distribution of acute oak decline using environmental factors. For. Ecol. Manage. 407, 145–154. ( 10.1016/j.foreco.2017.10.054) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denman S, Brown N, Kirk S, Jeger M, Webber J. 2014. A description of the symptoms of acute oak decline in Britain and a comparative review on causes of similar disorders on oak in Europe. Forestry 87, 535–551. ( 10.1093/forestry/cpu010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biosca EG, González R, López-López MJ, Soria S, Montón C, Pérez-Laorga E, López MM. 2003. Isolation and characterization of Brenneria quercina, causal agent for bark canker and drippy nut of Quercus spp. in Spain. Phytopathology 93, 485–492. ( 10.1094/PHYTO.2003.93.4.485) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruffner B, Schneider S, Meyer J, Queloz V, Rigling D. 2020. First report of acute oak decline disease of native and non-native oaks in Switzerland. New Dis. Reports 41, 18 ( 10.5197/j.2044-0588.2020.041.018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moradi-Amirabad Y, Rahimian H, Babaeizad V, Denman S. 2019. Brenneria spp. and Rahnella victoriana associated with acute oak decline symptoms on oak and hornbeam in Iran. For. Pathol. 49, e12535 ( 10.1111/efp.12535) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sitz R, Caballero J, Zerillo M, Snelling J, Alexander K, Tisserat N, Cranshaw W, Stewart J. 2018. Drippy blight, a disease of red oaks in Colorado produced from the combined effect of the scale insect Allokermes galliformis and the bacterium Lonsdalea quercina subsp. quercina. Arboric. Urban For. 44, 146–153. ( 10.1094/pdis-12-18-2248-re) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broberg M, Doonan J, Mundt F, Denman S, McDonald JE. 2018. Integrated multi-omic analysis of hostmicrobiota interactions in acute oak decline. Microbiome 6, 21 ( 10.1186/s40168-018-0408-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bass D, Stentiford GD, Wang H-C, Koskella B, Tyler CR. 2019. The pathobiome in animal and plant diseases. Trends Ecol. Evol. 34, 996–1008. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2019.07.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casadevall A, Fang FC, Pirofski L. 2011. Microbial virulence as an emergent property: consequences and opportunities. PLoS Pathog. 7, 1–3. ( 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002136) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doonan J, Denman S, Pachebat JA, McDonald JE. 2019. Genomic analysis of bacteria in the acute oak decline pathobiome. Microb. Genomics 5, 1–15. ( 10.1099/mgen.0.000240) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown N, Jeger M, Kirk S, Williams D, Xu X, Pautasso M, Denman S. 2017. Acute oak decline and Agrilus biguttatus: the co-occurrence of stem bleeding and D-shaped emergence holes in Great Britain. Forests 8, 87 ( 10.3390/f8030087) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Etcheverría AI, Padola NL. 2013. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: factors involved in virulence and cattle colonization. Virulence 4, 366–372. ( 10.4161/viru.24642) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell KS, et al. 2004. Genome sequence of the enterobacterial phytopathogen Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica and characterization of virulence factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 11 105–11 110. ( 10.1073/pnas.0402424101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansfield J, et al. 2012. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 614–629. ( 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00804.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindeberg M. 2012. Genome-enabled perspectives on the composition, evolution, and expression of virulence determinants in bacterial plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 50, 111–132. ( 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartoli C, et al. 2014. The Pseudomonas viridiflava phylogroups in the P. syringae species complex are characterized by genetic variability and phenotypic plasticity of pathogenicity-related traits. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 2301–2315. ( 10.1111/1462-2920.12433) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behar A, Jurkevitch E, Yuval B. 2008. Bringing back the fruit into fruit fly-bacteria interactions. Mol. Ecol. 17, 1375–1386. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03674.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jittawuttipoka T, Buranajitpakorn S, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. 2009. The catalase-peroxidase KatG is required for virulence of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris in a host plant by providing protection against low levels of H2O2. J. Bacteriol. 191, 7372–7377. ( 10.1128/JB.00788-09) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGenity TJ, Crombie AT, Murrell JC. 2018. Microbial cycling of isoprene, the most abundantly produced biological volatile organic compound on Earth. ISME J. 12, 931–941. ( 10.1038/s41396-018-0072-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roosild TP, Castronovo S, Healy J, Miller S, Pliotas C, Rasmussen T, Bartlett W, Conway SJ, Booth IR. 2010. Mechanism of ligand-gated potassium efflux in bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 19 784–19 789. ( 10.1073/pnas.1012716107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rennenberg H, Loreto F, Polle A, Brilli F, Fares S, Beniwal RS, Gessler A. 2006. Physiological responses of forest trees to heat and drought. Plant Biol. 8, 556–571. ( 10.1055/s-2006-924084) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanderbeld B, Snedden WA. 2007. Developmental and stimulus-induced expression patterns of Arabidopsis calmodulin-like genes CML37, CML38 and CML39. Plant Mol. Biol. 64, 683–697. ( 10.1007/s11103-007-9189-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu M, Khan NU, Wang N, Yang X, Qiu D. 2016. The protein elicitor PevD1 enhances resistance to pathogens and promotes growth in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 12, 931–943. ( 10.7150/ijbs.15447) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bao Y, et al. 2016. Overexpression of the NDR1/HIN1-Like gene NHL6 modifies seed germination in response to abscisic acid and abiotic stresses in arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 11, 1–16. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0148572) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yen SK, Chung MC, Chen PC, Yen HE. 2001. Environmental and developmental regulation of the wound-induced cell wall protein WI12 in the halophyte ice plant. Plant Physiol. 127, 517–528. ( 10.1104/pp.010205.related) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Hengel AJ, Guzzo F, van Kammen A, de Vries SC. 1998. Expression pattern of the carrot EP3 endochitinase genes in suspension cultures and in developing seeds. Plant Physiol. 117, 43–53. ( 10.1104/pp.117.1.43) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J, Xu X, Tian L, Wang G, Zhang X, Wang X, Guo W. 2016. Discovery and identification of candidate genes from the chitinase gene family for Verticillium dahliae resistance in cotton. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–12. ( 10.1038/srep29022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang LH, Fath MJ, Mahanty H, Tai P, Kolter R. 1995. Genetic analysis of the colicin V secretion pathway. Genetics 141, 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ndeh D, et al. 2017. Complex pectin metabolism by gut bacteria reveals novel catalytic functions. Nature 544, 65–70. ( 10.1038/nature21725) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pérez J, Muñoz-Dorado J, De La Rubia T, Martínez J. 2002. Biodegradation and biological treatments of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin: an overview. Int. Microbiol. 5, 53–63. ( 10.1007/s10123-002-0062-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antúnez-Lamas M, Cabrera-Ordóñez E, López-Solanilla E, Raposo R, Trelles-Salazar O, Rodríguez-Moreno A, Rodríguez-Palenzuela P. 2009. Role of motility and chemotaxis in the pathogenesis of Dickeya dadantii 3937 (ex Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937). Microbiology 155, 434–442. ( 10.1099/mic.0.022244-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geider K, Gernold M, Jock S, Wensing A, Völksch B, Gross J, Spiteller D. 2015. Unifying bacteria from decaying wood with various ubiquitous Gibbsiella species as G. acetica sp. nov. based on nucleotide sequence similarities and their acetic acid secretion. Microbiol. Res. 181, 93–104. ( 10.1016/j.micres.2015.05.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murdoch SL, Trunk K, English G, Fritsch MJ, Pourkarimi E, Coulthurst SJ. 2011. The opportunistic pathogen Serratia marcescens utilizes type VI secretion to target bacterial competitors. J. Bacteriol. 193, 6057–6069. ( 10.1128/JB.05671-11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jahn CE, Willis DK, Charkowski AO. 2008. The flagellar sigma factor fliA is required for Dickeya dadantii virulence. Mol. Plant. Microbe. Interact. 21, 1431–1442. ( 10.1094/MPMI-21-11-1431) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geiss GK, et al. 2008. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 317–325. ( 10.1038/nbt1385) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. 2009. RNA-seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 57–63. ( 10.1038/nrg2484) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Broberg M, McDonald JE. 2019. Extraction of microbial and host DNA, RNA, and proteins from oak bark tissue. Methods Protoc. 2, 15 ( 10.3390/mps2010015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin M. 2011. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12. ( 10.14806/ej.17.1.200) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joshi N, Fass J.. 2011. Sickle. A sliding-window, adaptive, quality-based trimming tool for FastQ files. See https://github.com/najoshi/sickle.

- 48.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. ( 10.1038/nmeth.1923) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roberts A, Pachter L. 2012. Streaming fragment assignment for real-time analysis of sequencing experiments. Nat. Methods 10, 71–73. ( 10.1038/nmeth.2251) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 ( 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luo W, Friedman MS, Shedden K, Hankenson KD, Woolf PJ. 2009. GAGE: generally applicable gene set enrichment for pathway analysis. BMC Bioinf. 10, 1–17. ( 10.1186/1471-2105-10-161) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu G, Wang L-G, Han Y, He Q-Y. 2012. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omi. A J. Integr. Biol. 16, 284–287. ( 10.1089/omi.2011.0118) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szöcs E, et al. 2015. Analysing chemical-induced changes in macroinvertebrate communities in aquatic mesocosm experiments: a comparison of methods. Ecotoxicology 24, 760–769. ( 10.1007/s10646-015-1421-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.R Core Team. 2017. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Naumann U, Wright ST, Warton DI. 2012. Mvabund: an R package for model-based analysis of multivariate abundance data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 471–474. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2012.00190.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng J, Meyer CA, Wang Q, Liu JS, Liu XS, Zhang Y. 2012. GFOLD: a generalized fold change for ranking differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 28, 2782–2788. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts515) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data have been deposited in NCBI under BioProject PRJNA369790.