Abstract

Policy Points.

Changes in US state policies since the 1970s, particularly after 2010, have played an important role in the stagnation and recent decline in US life expectancy.

Some US state policies appear to be key levers for improving life expectancy, such as policies on tobacco, labor, immigration, civil rights, and the environment.

US life expectancy is estimated to be 2.8 years longer among women and 2.1 years longer among men if all US states enjoyed the health advantages of states with more liberal policies, which would put US life expectancy on par with other high‐income countries.

Context

Life expectancy in the United States has increased little in previous decades, declined in recent years, and become more unequal across US states. Those trends were accompanied by substantial changes in the US policy environment, particularly at the state level. State policies affect nearly every aspect of people's lives, including economic well‐being, social relationships, education, housing, lifestyles, and access to medical care. This study examines the extent to which the state policy environment may have contributed to the troubling trends in US life expectancy.

Methods

We merged annual data on life expectancy for US states from 1970 to 2014 with annual data on 18 state‐level policy domains such as tobacco, environment, tax, and labor. Using the 45 years of data and controlling for differences in the characteristics of states and their populations, we modeled the association between state policies and life expectancy, and assessed how changes in those policies may have contributed to trends in US life expectancy from 1970 through 2014.

Findings

Results show that changes in life expectancy during 1970‐2014 were associated with changes in state policies on a conservative‐liberal continuum, where more liberal policies expand economic regulations and protect marginalized groups. States that implemented more conservative policies were more likely to experience a reduction in life expectancy. We estimated that the shallow upward trend in US life expectancy from 2010 to 2014 would have been 25% steeper for women and 13% steeper for men had state policies not changed as they did. We also estimated that US life expectancy would be 2.8 years longer among women and 2.1 years longer among men if all states enjoyed the health advantages of states with more liberal policies.

Conclusions

Understanding and reversing the troubling trends and growing inequalities in US life expectancy requires attention to US state policy contexts, their dynamic changes in recent decades, and the forces behind those changes. Changes in US political and policy contexts since the 1970s may undergird the deterioration of Americans’ health and longevity.

Keywords: life expectancy, social determinants of health, health disparities, US state policies

For a number of years, the united states has ranked last in life expectancy among high‐income countries. 1 , 2 In 2016, life expectancy of American women (81.4 years) was 3.0 years below the female average of high‐income countries and 5.8 years below the leader; life expectancy of American men (76.4 years) was 3.4 years below the male average and 5.2 years below the leader. 2 The fall of the United States to the bottom in international rankings began in the 1980s, first with slower gains in longevity than other countries and then with absolute declines in recent years. 1 , 2 Among 22 high‐income countries, the United States fell from thirteenth place in 1980 to the bottom by the early 2000s. 1 Given that life expectancy captures overall social, economic, physical, and mental well‐being, such trends paint a troubling portrait of life and death in the United States.

Compared with residents of other high‐income countries, Americans have worse health on multiple measures and higher mortality risk throughout the life course until about age 75. 3 Explanations for these disparities are complex and multifaceted. In 2013, a report commissioned by the National Research Council outlined five potential explanations: public health and medical care systems, individual behaviors, social and economic factors, physical and social environments, and policies and social values. 3 Studies to date have largely focused on the first three explanations, with mixed evidence about their contribution. Some researchers assert that medical care could contribute only a small extent to the US longevity disadvantage, 4 noting that the disadvantage exists even among Americans with health insurance 5 ; the United States spends more on medical care than any other country; shortfalls in medical care explain just 10%‐15% of preventable mortality in the United States 6 ; and deaths from external causes (suicides, homicides, accidents), which increasingly comprise a sizable part of the disadvantage, 2 are not determined by medical care. Other studies note that Americans engage in some unhealthy behaviors more so than do individuals in peer countries. For example, Americans have the highest average caloric consumption in the world and have historically had higher smoking rates than peer countries. 3 However, even a highly risky behavior like smoking cannot explain why the US mortality disadvantage is pronounced below age 50. 4 , 7 Socioeconomic factors might also contribute to the US disadvantage, particularly given the relatively high prevalence of poverty and income inequality. Yet, even highly educated and high‐income Americans (particularly women) have worse health and shorter lives than their peers in many other high‐income countries. 8 , 9 Importantly, even if proximal explanations such as smoking, diet, poverty, and medical care did explain the disadvantage, they do not explain why Americans used to smoked more, consume more calories, experience higher poverty levels, are less likely to have health insurance, and so on. 4 , 10 Doing so requires examining upstream factors and taking a political economy perspective. 4 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16

Importance of US States

Progress in explaining the troubling trends in US life expectancy will be greatly enhanced by making two shifts in focus. The first is a focus on subnational analyses, particularly on US states. National analyses obscure substantial differences across states. In 2017, life expectancy ranged from 74.6 years in West Virginia to 81.6 years in Hawaii. 17 If West Virginia were a nation, it would be ranked ninety‐third in the world in terms of life expectancy, between Lithuania and Mauritius. 18 In fact, life expectancy in West Virginia falls below several lower‐middle‐income countries, including Honduras, Morocco, Tunisia, and Vietnam. If Hawaii were a nation, it would rank twenty‐third in the world. Its life expectancy is within 0.7 years of world leaders such as Canada, Iceland, and Sweden.

Indeed, there is compelling evidence that the falling position of the United States in international rankings of life expectancy in the post‐1980 era partly reflects the growing geographic disparities in health and longevity within the United States. 19 For instance, after examining life expectancy at age 50 in the United States and other high‐income countries (Canada, France, Germany, Japan) between 1980 and 2000, Wilmoth and colleagues concluded that 10% to 50% of the growing life‐expectancy gap between the United States and those countries was attributable to growing geographic variation within the United States, alongside shrinking variation in the other countries, with the growing US variation being the driving force. 19

To illustrate the growing divergence in life expectancy between US states starting around 1980, Figure 1 shows trends in life expectancy by state. Life expectancy became more similar across states during the 1960s and 1970s but began to diverge in the early 1980s. By 2017, the 7.0‐year gap in longevity across states was the largest recorded. Figure 1 illustrates that states have taken vastly different trajectories. For instance, in 1959, life expectancy was 71.1 years in both Connecticut and Oklahoma. By 2017, Connecticut had gained 9.6 years, putting it near the top of states’ rankings, while Oklahoma had gained just 4.7 years, putting it near the bottom. In short, explaining trends in US life expectancy requires the consideration of state contexts.

Figure 1.

Trends in Life Expectancy by US State, 1959–2017 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Data from the United States Mortality Database. 17

Importance of Structural Explanations

The second shift in focus requires attention to structural explanations, particularly the policy contexts of US states. Indeed, several researchers have hypothesized that the US health and longevity disadvantage in large part reflects structural conditions related to the policy environment. 10 , 11 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 20 For instance, Avendano and Kawachi claimed that “much of the US health disadvantage is due to variations in nonmedical determinants of health, some of which result from dramatic differences in public policies across the United States and other OECD countries.” 4 (p321) They described a number of US policies that are less generous than policies in other high‐income countries, such as those on housing, income support, labor protections, and education. Similarly, Bambra and colleagues asserted that “to properly understand the US mortality disadvantage, geographical research needs to ‘scale up’ and refocus on upstream political, economic, and policy drivers.” 10 (p39) Montez also urged researchers to “hypothesize upward,” 12 proposing that deregulation, the devolution of policymaking authority from federal to state levels, and state preemption laws are major forces behind the growing gaps in longevity across US states and its deteriorating overall ranking.

As a key structural factor, policies influence a host of “downstream” factors such as economic well‐being, individual behaviors, and medical care access. Policies shape opportunities for a healthy life and the importance of social determinants (eg, education, race) of health. As Bambra and colleagues claimed, policies and political choices are “the causes of the causes of the causes of geographical inequalities in health” (emphasis in original), and that research must focus on them or risk “missing the bigger picture.” 10 (pp37‐38) The present study provides a first look at how the overall policy context of US states (combinations and orientations of policies) may underlie the troubling trends and growing geographic inequalities in life expectancy.

Recent evidence has demonstrated that, since the 1970s, the policy context in which Americans live is increasingly determined by their state of residence. 21 , 22 This new reality was spurred by two significant changes in the balance of policymaking authority across federal, state, and local governments. First, the decentralization of policymaking authority from federal to state levels (termed “devolution”) gave states greater discretion over programs such as welfare and Medicaid by replacing categorical grants to states with block grants that had few strings attached. 23 Second, the more recent surge of state preemption laws has greatly curtailed local authority. 24 Many states now prohibit localities from enacting laws such as smoke‐free ordinances, nutrition labeling in restaurants, paid sick days, and raising the minimum wage. 25 For example, in 2000, only two states (Louisiana, Colorado) preempted their localities from raising the minimum wage, and no state preempted localities from mandating paid leave. At present, 25 states preempt localities from raising the minimum wage, and 20 states preempt mandatory paid leave. 26 A large body of empirical research demonstrates that these state‐level policies, like many others, have significant consequences for population health. 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31

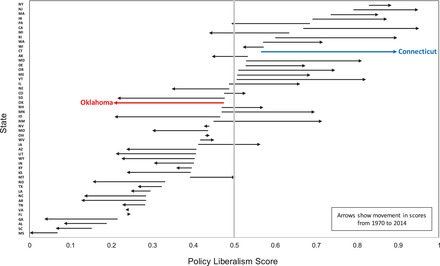

Political scientists report that the increase in policymaking authority among states has been accompanied by a hyperpolarization of policies across states. 21 , 22 Figure 2 shows how states’ overall policy orientation changed between 1970 and 2014. The policy orientation scores were developed by Grumbach, 21 who collected annual information on 135 state‐level policies from 1970 through 2014. Using an established methodology, 32 Grumbach assigned to all state‐year observations a score from 0 to 1 indicating the overall policy liberalism of that observation, where a score of 0 represents the most conservative state policy context observed during the 45‐year period and 1 represents the most liberal context. As Grumbach noted, the polarization is striking. Most states moved further from the center during the period. Interestingly, the two states that exhibited the largest movement were Oklahoma and Connecticut.

Figure 2.

Change in US States’ Overall Policy Orientation Between 1970 and 2014 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Data are from Grumbach, 21 who assigned an overall policy liberalism score for each state in each calendar year and then normalized the scores across all state‐year observations to a 0‐1 scale reflecting a conservative‐liberal continuum. The start of each arrow represents the 1970 score, while the arrowhead represents the 2014 score.

Figure 3 combines information from Figures 1 and 2, providing another view of the potential link between diverging state policies and diverging longevity. It plots the annual range in policy orientation scores across states against the annual range in longevity. Both the policy orientation and longevity of states converged until the early 1980s and have since been diverging.

Figure 3.

Range in Policy Orientation and Life Expectancy Across US States, 1970–2014

State policy scores are from Grumbach, 21 and state life expectancy data are from the United States Mortality Database. 17 The range in life expectancy in each calendar year is the difference between the state with the highest life expectancy and the state with the lowest life expectancy. The range in policy orientation in each calendar year is the difference between the state with the maximum policy liberalism score and the state with the minimum policy liberalism score.

The main aim of this study is to assess how the policy contexts of US states since 1970 may have contributed to the troubling trends in life expectancy. The study addresses two main questions. First, how do shifts in state policy contexts predict men's and women's life expectancy since 1970? To answer this question, we use a recently created, extensive data set of state‐level policies, where each policy is measured on a conservative‐liberal continuum. 21 The second question is hypothetical: how might US longevity change if all states enacted policy contexts that were liberal or conservative, or that mirrored the states with the largest or smallest shifts in policy context between 1970 and 2014? This study makes several important contributions. It addresses the call of several researchers in recent years to investigate the upstream policy factors that may undergird the troubling trends in US longevity. 4 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 14 In addition, by including a large and diverse set of policies summarized into 18 policy domains, the study advances knowledge on how those policy domains are collectively associated with life expectancy and which domains may be key levers for improving US longevity.

Data and Methods

Data on US State Life Expectancy

Annual data on life expectancy by state were taken from the United States Mortality Database (USMD). 17 Life expectancy is an ideal indicator of overall population health. The USMD data were released in 2018 as the first documented set of complete US state life tables. We examine male and female life expectancy separately because prior work has shown sex‐specific trends in life expectancy for the country as a whole and by states, 2 , 19 and suggests that the importance of state contexts for mortality risk may differ for women and men. 33

Data on US State Policies

The main source of data on state policies is the study by Grumbach. 21 As shown in Table 1, the data contain 135 policies spanning 16 domains: abortion, campaign finance, civil rights and liberties, criminal justice, education, environment, gun control, health and welfare, housing and transportation, immigration, private sector labor, public sector labor, LGBT rights, marijuana, taxes, and voting. For each state, the data contain a score for each domain annually from 1970 through 2014.

Table 1.

State Policies and Policy Domains

| Abortion | Campaign Finance | Civil Rights and Liberties |

|

Abortion insurance restriction Abortion legality Consent post‐Casey Consent pre‐Casey Emergency contraception Gestation limit Medicaid covers abortion Parental notice Partial birth abortion ban Physician required Waiting required |

Corporate contribution ban Dollar limit on individual contributions Dollar limit on PAC contributions Limit on individual contributions Limit on PAC contributions Public funding of elections |

Bible allowed in public schools Corporal punishment ban Discrimination ban in public accommodations ERA ratification Fair employment commission Gender discrimination ban Gender equal pay law Moment of silence in public school No‐fault divorce Physician‐assisted suicide Public breastfeeding Religious freedom rights amendment Reporters’ right to source confidentiality State ADA State ERA |

| Criminal Justice | Education | Environment |

|

Death penalty repeal Determinate sentencing DNA motions Three strikes Truth in sentencing |

Charter school law Higher ed. spending K‐12 spending School choice |

Bottle bill CA car emissions Endangered species E‐waste Greenhouse gas cap Renewables fund Solar tax credit State NEPA |

| Gun Control | Health and Welfare | Housing and Transportation |

|

Assault weapon ban Background checks (dealers) Background checks (private) Brady law Dealer licenses required Gun registration Open carry Saturday night special ban Stand‐your‐ground laws |

ACA exchange AFDC payment level AFDC Unemployed Parent program CHIP eligibility (children) CHIP eligibility (infants) CHIP eligibility (pregnant women) Expanded dependent coverage Medicaid adoption Medicaid expansion Pre‐BBA CHIP eligibility Senior prescription drugs TANF eligibility TANF payment level Welfare drug test Welfare time limit |

Growth management Lemon law Rent control ban Tort limit |

| Immigration | Labor (Private Sector) | Labor (Public Sector) |

|

Driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants English official language E‐verify E‐verify ban In‐state tuition for undocumented immigrants State cash benefits for recent immigrants State food benefits for recent immigrants |

Disability insurance Local minimum wage ban Local sick leave law ban Minimum wage Paid family leave Paid sick leave Prevailing wage Right to work Unemployment compensation |

Ban on agency fees (state) Collective bargaining (firefighters) Collective bargaining (local) Collective bargaining (police) Collective bargaining (state) Collective bargaining (teachers) |

| State health benefits for recent immigrants | ||

| LGBT Rights | Marijuana | Others |

|

Civil unions and marriage Gay marriage ban Hate crime law LGB discrimination ban in public accommodations LGB employment discrimination ban Sodomy ban |

Marijuana decriminalization Medical marijuana |

Animal cruelty felony Beer keg registration Bike helmet required Casinos Cigarette tax Drinking age 21 Grandparent visitation Living wills Lottery Mandatory car insurance Mandatory seat belts Motorcycle helmet required Smoking ban (restaurants) Smoking ban (workplaces) Zero tolerance of underage drinking |

| Taxes | Voting | |

|

Corporate tax rate Earned income tax credit Estate tax Income tax Sales tax Tax burden Top capital gains rate Top income rate |

Absentee voting Early voting Motor voter Voter ID |

Adapted from Grumbach.21 ACA = Affordable Care Act, ADA = Americans with Disabilities Act, AFDC = Aid to Families with Dependent Children, BBA = Bipartisan Budget Act, CHIP = Children's Health Insurance Program, ERA = Equal Rights Amendment, NEPA = National Environmental Policy Act, PAC = political action committee, TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

As described by Grumbach, 21 the scores for each policy domain were derived from an established method analogous to that used by Erikson and colleagues. 32 First, each of the 135 policies was categorized as liberal or conservative. Liberal was defined as expanding state power for economic regulation and redistribution or for protecting marginalized groups, or restricting state power for punishing deviant social behavior; conservative was defined as the opposite. 21 For instance, legalization of medical marijuana was categorized as a liberal policy, and gay marriage bans were categorized as a conservative policy. Second, each policy was scored on a 0‐1 scale, where 0 and 1 represent the actual range of the policies during the 1970‐2014 period on a conservative‐to‐liberal continuum. For example, a state's score for medical marijuana policy is 0 in years when it was not legal and 1 in years when it was legal. Policies that are not binary (eg, minimum wage level) were normalized across all state‐year observations to range from 0 to 1. In the third step, a state's annual score for each policy domain was calculated as the sum of the liberal policy scores minus the sum of the conservative policy scores. To facilitate interpretation, the summed scores for each domain were then normalized across all states and years to a 0‐1 scale.

We added two other important measures to the 16 domains. We added state excise taxes on tobacco (measured as cents per pack of cigarettes), given their key role in deterring smoking, the leading preventable cause of death. 34 This measure was among the 15 policies that Grumbach placed in an “Other” category for policies whose ideological direction was considered unclear or that varied little across states. 21 We also added a measure of overall policymaking activity to examine whether activity itself is an important indicator, net of the substance of policies. Activity was measured by the well‐established state policy innovation score, defined as the number of policies adopted by a state divided by the number of adoption opportunities (ie, policies adopted by other states but not yet by that state). 35 , 36 As with the other measures, we normalized tobacco taxes (in 2015 dollars) and policy activity on a 0‐1 scale.

Operationalizing Time

A key decision in our analysis was how to specify the time trend in life expectancy. As shown in Figure 1, the overall trend is nonlinear and includes multiple points where the slope of the trend appears to change. In such situations, joinpoint regression models are a helpful statistical tool for specifying temporal trends and identifying calendar years when the slope changed significantly. 37 Joinpoints are the years when the slope changed significantly; the years in between joinpoints are linear segments.

The results identified five segments for women (1970‐1978, 1979‐1991, 1992‐2001, 2002‐2009, 2010‐2014) and four for men (1970‐1981, 1982‐1988, 1989‐2010, 2011‐2014) as the best fit of the observed trends in life expectancy. Our joinpoint regression model specification accounted for autocorrelation, with an autocorrelation parameter estimated by the data, and it used the permutation test to select the joinpoints. The results were fairly robust to alternative model specifications. The model identified the same joinpoints when using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to select the joinpoints, but dropped the 1991/1992 joinpoint for women when using a modified BIC that imposes an even harsher penalty than the BIC for identifying joinpoints. 38

Given the strengths of joinpoint regression models for investigating nonmonotonic trends, recent studies have used these models to identify trends in life expectancy and mortality in the United States. 39 , 40 Another benefit of these models is that the linear segments they identify can be used to more meaningfully measure time in our main analyses. In those analyses (described later in the article), we assess the extent to which the slope of each time segment changes once state policy contexts are included in the models.

Approach

We estimated regression models of life expectancy as a function of time, the 18 policy domain measures, and state‐level fixed effects. The fixed effects control for all time‐invariant observed or unobserved state‐level characteristics. They are specified by adding an indicator variable for each state and can be conceptualized as subtracting each year‐specific variable from its overall state‐specific average. This means our models use within‐state variation over time for estimating the association between policies and life expectancy, not differences between states. Consequently, the models can be used to estimate changes in life expectancy within a state from changes in policies within a state. The models weigh the observations by each state's population size in that year and adjust for spatial and temporal correlation of errors (eg, because neighboring states may have similar life expectancies simply due to geographic proximity, and life expectancy in year t is related to life expectancy in year t − 1) using Driscoll and Kraay standard errors 41 and the “xtscc” command in Stata. 42

Despite using state fixed effects and 45 years of panel data, our results are based on observational data and thus reflect statistical associations rather than causal relationships. Our models eliminate bias due to unobserved, time‐invariant characteristics of states and their populations. Although they do not guard against potential bias of unobserved time‐varying characteristics, we minimize this threat by including an extensive data set of time‐varying state policies and an overall policy activity measure that captures any residual policymaking activity (although it does not capture the substance of those policies), as well as controlling for two other time‐varying characteristics that could potentially bias our results. Specifically, all models include the percentage of the state's population that are immigrants—because immigrants generally exhibit a mortality advantage compared to US‐born individuals and the immigrant population has grown more in some states than in others—and supplementary models also include the states’ unemployment rates. (These models are supplementary because state‐level unemployment rates are unavailable before 1976.) These and all other supplementary analyses did not alter our conclusions; we discuss these analyses later.

Results

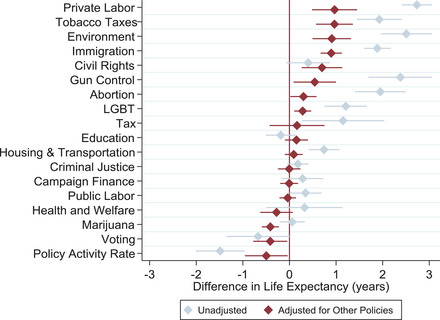

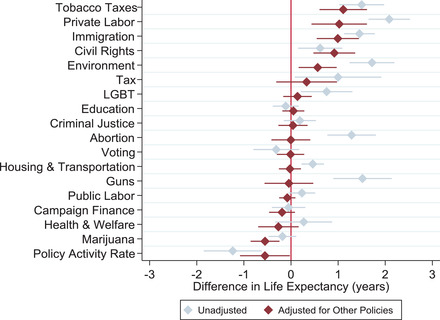

Our first set of models estimate life expectancy from the 18 policy measures, accounting for time, state fixed effects, immigration, and spatial and temporal correlation. The estimates shown in Figures 4 (women) and 5 (men) as gray diamonds are from 18 separate models that each include one of the policy measures. The estimates shown as red diamonds are from a single model that includes all 18 policy measures. The latter model thus takes account of the correlation between policy domains (ie, states with liberal environmental policies tend to have liberal labor policies), so we focus on these estimates. The horizontal lines depict 95% confidence intervals. The models estimate, for example, that female life expectancy would be 2.5 years higher (gray diamond) within a state if it had the most liberal policies on the environment (ie, the environment policy score = 1) than if it had the most conservative (score = 0); however, the increase amounts to 0.9 years (red diamond) when the other 17 policy measures are included. Recall that the 0 and 1 scores are based on the actual, not hypothetical, range of policy liberalism scores during the 1970‐2014 period. Full model results are available in the online appendix Tables A1 for women and A3 for men.

Figure 4.

Estimated Difference in Female Life Expectancy Within a US State When a Policy's Liberalism Score Is 1 vs. 0 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Estimates are from authors’ analysis using state policy scores from Grumbach 21 and state life expectancy from the United States Mortality Database. 17 Horizontal spikes are 95% confidence intervals. Full model results are provided in the online appendix Table A1, Models 1 and 5.

Figure 5.

Estimated Difference in Male Life Expectancy Within a US State When a Policy's Liberalism Score Is 1 vs. 0 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Estimates are from authors’ analysis using state policy scores from Grumbach 21 and state life expectancy from the United States Mortality Database. 17 Horizontal spikes are 95% confidence intervals. Full model results are provided in the online appendix Table A3, Models 1 and 5.

The red diamonds show three noteworthy patterns. First, within a state, more liberal versions of the policies are generally associated with longer life expectancy. Among the ten policy domains with a statistically significant association with life expectancy, a more liberal version of eight domains was associated with longer lives (tobacco, immigration, civil rights, private labor, environment, gun control, LGBT, and abortion; the exceptions were marijuana and voting). Second, the degree to which policy liberalism is related to longevity varies across policy domains. If a policy's liberalism score was 1 instead of 0 within a state, the model estimates that life expectancy within a state would be significantly longer for the following policy measures: tobacco (1.1 years longer for men, 1.0 year longer for women), private labor (1.0 year for both women and men), immigration (1.0 year for men, 0.9 years for women), civil rights (0.9 years for men, 0.7 years for women), environment (0.6 years for men, 0.9 years for women), gun control (0.5 years for women), LGBT (0.3 years for women), and abortion (0.3 years for women). It would be shorter for two domains: marijuana (0.6 years for men, 0.4 years for women) and voting (0.4 years for women). A third noteworthy finding is that women's life expectancy is related to nearly twice as many policies as is men's life expectancy.

The overall amount of policymaking activity within a state during the study period predicts a significantly lower life expectancy, even when including the other 17 policy measures. Specifically, if a state moved from being the least active to the most active in terms of policymaking, the model predicts that life expectancy would be 0.5 years shorter for women and 0.6 years shorter for men.

The overarching implications of the model results for US life expectancy are highlighted in Table 2. If all states’ policies had the maximum liberal score on the policy measures, the model estimates that US life expectancy would be 2.8 years longer among women and 2.1 years longer among men. If all states’ policies were the same as Connecticut in 2014 (Connecticut made the largest shift toward liberal policies between 1970 and 2014), we estimate that US life expectancy would be 2.0 and 1.3 years longer among women and men, respectively. However, if those policies imitated Oklahoma in 2014 (Oklahoma made the largest shift toward conservative policies), US life expectancy would be an estimated 1.0 and 0.5 years shorter among women and men, respectively. In addition, the model estimates that the status quo—allowing the current policy direction of the states to continue—would yield minimal improvement in longevity: US life expectancy would be 0.4 and 0.3 years higher among women and men, respectively. The online appendix Table A5 provides details for all scenarios.

Table 2.

Estimated Change in US Life Expectancy for 11 Hypothetical Policy Contexts

| Estimated Change in Life Expectancy (years) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Policy Context | Women | Men |

| All policy scores = 1 | 2.8 | 2.1 |

| 1. Policies of the state that made greatest movement toward liberal policies from 1970 to 2014 (Connecticut) | 2.0 | 1.3 |

| 2. Policies of five states with highest overall policy liberalism scores in 2014 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

| 3. Policies of five states with highest life expectancy in 2014 | 1.7 | 1.2 |

| 4. Policies of five states with largest gains in life expectancy from 1970 to 2014 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| 5. Current policy direction | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 6. Policies of five states with smallest gains in life expectancy from 1970 to 2014 | −0.7 | −0.3 |

| 7. Policies of five states with lowest life expectancy in 2014 | −1.0 | −0.8 |

| 8. Policies of five states with lowest overall policy liberalism scores in 2014 | −1.2 | −1.0 |

| 9. Policies of the state that made greatest movement toward conservative policies from 1970 to 2014 (Oklahoma) | −1.0 | −0.5 |

| 10. All policy scores = 0 | −2.0 | −1.9 |

Estimates are from authors’ analysis using state policy scores from Grumbach21 and state life expectancy from the United States Mortality Database.17 Detailed description of each policy context and the calculations are provided in the online appendix Table A5.

The models also provided information for estimating the degree to which state policies may have contributed to national trends in life expectancy during 1970‐2014. Specifically, we compared the coefficient for each linear time segment before and after including the 18 policy measures (ie, we compared the relevant time segment coefficients between Models 2 and 5 of the online appendix Tables A1 for women and A3 for men). During the 1970‐1978 segment, US female longevity increased by an average of 0.318 years per calendar year, controlling for immigration, but that slope was reduced to 0.308 years after also controlling for the 18 policy measures. This implies that changes in state policies during this period statistically accounted for just 3.1% [100(0.318 − 0.308)/0.318] of the increase in US female longevity, and any policy changes that improved longevity outweighed any that harmed it. We then formally tested whether the two slopes, 0.318 and 0.308, were statistically different from each other at p < 0.05 (using a seemingly unrelated regression test of cross‐model coefficients with the “suest” command in Stata) and found that they are not. Thus, the modest attenuation of the time segment slope, combined with the nonsignificant difference in the slopes, indicates that state policies during the 1970s were not a major influence on female longevity trends during that time. Some of the strongest evidence for the role of state policies with regard to female longevity is in 2002‐2009. Accounting for the 18 policy measures reduced the slope during this time from 0.180 to 0.147, a statistically significant 18% reduction. Again, it seemed that policy changes that improved female longevity during this segment outweighed those that harmed it.

Importantly, we find some evidence that changes in state policies during the 1980s and after 2010 suppressed increases in life expectancy among women and men, perhaps contributing to the US health disadvantage relative to other high‐income countries. For instance, our models suggest that the longevity slope during 2010‐2014 would have been 25% steeper for women and 13% steeper for men if state policies had not changed as they did. Although these differences are not statistically significant (perhaps due to the short time window), their magnitude is sizable and noteworthy. Online appendix Figure A1 shows the percentage change in the longevity slope for all time periods.

Supplementary Analyses

We conducted additional analyses to assess the robustness of our findings to alternative model specifications. We first examined whether using indicator variables for each calendar year instead of the linear time segments would alter our findings. However, our findings are robust, implying that there is no loss of information or bias introduced when using the linear time segments. One coefficient marginally changed and became statistically significant (the LGBT policy coefficient for men increased from 0.1 to 0.3), but the increase itself was not significant at p < 0.05. We also reestimated the models using a 2‐year time lag, so that the policy measures preceded the life expectancy measures. Again, the results were robust; any changes in the policy coefficients were small in size and retained their directional association (positive or negative) with life expectancy.

We also assessed whether any policy domains exhibited nonlinear relationships with life expectancy by adding quadratic terms for each policy measure to the model. Although the results showed a statistically significant nonlinearity between a few policy scores and life expectancy, the magnitude was quite small and did not materially change our findings. The one noteworthy finding is that increasingly liberal environmental policies within a state had little association with longevity until the policy score was around 0.5, after which there was a steep positive association.

To further test our models, we selected several policies that should not have an effect on life expectancy (sometimes called a “placebo test”). Specifically, from Table 1, we a priori chose beer keg registration and animal cruelty felony policies (on the list of Other policies) and reporters’ rights to source confidentiality (on the list of civil rights and liberties policies). We then estimated life expectancy from each individual policy, adjusting for time and immigration (as done in Model 1 from Tables A1 and A3), and, as expected, found no significant association between these policies and life expectancy at p < 0.05. For beer keg registration, the policy coefficients and their standard errors were 0.19 (0.11) for women and 0.18 (0.12) for men; for animal cruelty felony, the coefficients and standard errors were −0.12 (0.10) for women and −0.07 (0.09) for men; and for source confidentiality, the estimates were −0.10 (0.07) for women and 0.08 (0.07) for men.

Last, although the models accounted for time‐invariant characteristics of states and their populations, we nevertheless included the state's annual unemployment rates in supplementary analyses to assess whether accounting for macroeconomic conditions altered our findings (extant studies find a relationship between state‐level unemployment and mortality rates). 43 For these analyses, we used the subset of calendar years (1976‐2014) for which data on state‐specific unemployment rates were available. Our findings remain the same, which likely reflects the large amount of information included in the models and the relative stability of states’ rankings on unemployment rates. The analyses for all robustness checks are available in the online appendix Tables A2 and A4.

Discussion

The changing policy contexts of US states since the 1970s may have played a sizable role in shaping US life expectancy. Indeed, this study's findings are consistent with the proposition that changes in state policy contexts 21 , 22 have contributed to the growing gap in life expectancy across states since 1980 19 and suppressed overall gains in US life expectancy. This is particularly striking during the last five years of our study period (2010‐2014), in which we estimated that the shallow upward trend in US life expectancy would have been 25% steeper for women and 13% steeper for men had state policies not changed as they did.

A central thesis in our findings is that state policies matter. Researchers show that state policy contexts began to hyperpolarize after 1970. 21 , 22 Some states implemented more liberal policies across multiple domains that were associated with longer lives, and some states did the opposite. We found that policies on tobacco, labor, immigration, civil rights, and the environment were strongly associated with longevity among women and men, with more liberal versions of each policy within a state predicting a nearly 1‐year increase in that state's life expectancy. Other studies have similarly found that policies offering more generous income supports and social services predict lower risks of mortality and morbidity. 11 , 44 Other policies also mattered. For instance, more liberal policies on abortion and gun control predicted longer life expectancy among women, while more conservative marijuana policies predicted longer lives for both women and men. A review of the effect of marijuana policies on outcomes such as usage and marijuana‐involved emergency room episodes reported both null and negative effects, and suggested that the evidence was inconclusive given the difficulty in measuring the heterogeneity in marijuana policies. 45 Taking these findings together, the slow gains in US longevity may partly reflect the national shift toward some conservative policies that are negatively associated with longevity (eg, abortion restrictions, reductions in gun control) offsetting the national shift toward some liberal policies that are positively associated with longevity (eg, environment and civil rights protections). 21

We estimated that altering state policies might change US life expectancy by a magnitude of approximately two years. Altering all of the state policies that we examined to attain the maximum liberalism score predicted that US longevity would be 2.8 years longer among women and 2.1 years longer among men, while altering them to have the minimum score predicted a 2.0‐year reduction in life expectancy among women and a 1.9‐year reduction in life expectancy among men. Because our estimates were based on the actual range of policy liberalism across US states, they are smaller than those reported in one recent study, which estimated that US life expectancy would increase by 3.8 years if the country had the average level of generosity in the social policies of a comparison set of 17 high‐income countries. 11

The causal mechanisms linking state policies to life expectancy are complex. For example, environmental laws can shape exposure to toxic substances that damage respiratory and cardiovascular function, affect gene expression, disrupt endocrine function, and increase the risk of death. 46 Civil rights laws may help protect individuals from the pernicious mental and physical health effects of racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination. 47 Living in a US state with weak protections for lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations may elevate rates of generalized anxiety disorder, post‐traumatic stress disorder, and dysthymia among these populations. 48 Labor policies such as higher minimum wage and paid family leave can improve economic well‐being, health behaviors, birth outcomes, and access to prenatal care, and can decrease mortality rates. 28 , 31 , 49 , 50 Tobacco control policies, such as higher excise taxes and indoor smoking bans, have reduced the prevalence of smoking. 34 Restrictive abortion policies have been linked with women's poverty, reduced employment, anxiety, poor physical health, and violence from the man involved in the pregnancy. 51 And finally, access to firearms in the home is associated with greater risks of gun‐related homicide (particularly for female victims, thought to reflect partner victimization) and suicide. 52 Collectively, these studies indicate that the mechanisms are numerous and complex and shape nearly all aspects of people's lives.

Some prior work finds that states have a greater influence on women's than men's mortality, implying that changes in US state contexts since the 1970s may help explain the alarming trends in female life expectancy. 1 , 33 Many state policies, such as minimum wage, the earned income tax credit, abortion laws, paid family leave, and Medicaid, are particularly salient to women given that they are more likely than men to be employed in low‐wage jobs, raising children, caring for aging parents, and interfacing with medical institutions, among other such obstacles. This is consistent with our results, which also suggest greater vulnerability among women. Compared to men's life expectancy, women's life expectancy was significantly associated with nearly twice as many policies (six policies for men, ten for women), including policies concerning gun control and abortion, which have, on a national level, shifted in recent decades in a direction associated with lower female life expectancy. We also find that, after 2010, gains in women's life expectancy appeared to be hindered more so than gains in men's life expectancy by the changes in state policies.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study used an extensive set of state policies, 45 years of panel data, and robust statistical methods; however, some shortcomings exist. First, as mentioned previously, the analyses do not prove that state policies have a causal effect on life expectancy. Our analyses were intended to estimate changes in life expectancy within a state from changes in a large set of policies within a state, without making definitive causal claims. Although our findings are consistent with a large body of evidence derived from quasi‐experimental and other robust causal methods that shows many of the policies included in our study have a causal effect on health and longevity (see, for example, Carpenter and Cook, Komro et al., Lenhart, Muennig et al., Rossin, Sommers et al., and Van Dyke et al.), 28 , 29 , 31 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 our findings should be considered suggestive evidence and should be replicated.

Second, our analyses did not include the substance of all possible policies that differ across states, so our findings may be considered a lower bound on the extent to which the state policy environment shapes life expectancy. It included the substance of a large set of 121 policies, plus a measure of policy activity that helps capture residual policymaking. We did not include design controls for nonpolicy factors that consistently differ across states, such as smoking norms, as our models removed the effects of such factors by using fixed effects for states. We also did not include all possible nonpolicy factors that vary over time (we included the percentage of immigrants in a state, and in sensitivity analyses, also unemployment rates). Many such factors, like education level or poverty rates, are better understood as mechanisms through which state policies mediate effects on longevity. This study aimed to assess how the overall policy contexts of states are associated with longevity, not to map out causal pathways, an important priority for future research. Last, another possible limitation is that the scores for the policy domains make some assumptions (eg, that each policy is weighted equally important), which Grumbach 21 acknowledged while outlining how the strengths of the measure outweigh its limitations.

As in any analysis of geographic inequalities of health, interstate migration could influence the results. Although this possibility should not be ignored, extant studies suggest that migration is unlikely to have a material impact on our findings. Recent work finds that state of residence, not state of birth, is the main driver of adult mortality risk, and that this applies across sex and educational attainment. 57 In addition, although movers tend to be healthier than stayers, the characteristics of destination states (eg, foreclosure rates, school rankings, income, homicide rates) tend to be similar or worse than origin states. 58 , 59 This may explain why recent research concluded that interstate mortality trends are not explained by a healthy migrant effect or interstate migration patterns. 58 The reasons for these collective findings are unclear, but a study of rural‐to‐urban migration may shed some light. It found that, although movers had an initial health advantage compared to stayers, they developed a higher risk of death than stayers because they engaged in the lifestyles (eg, smoking, alcohol) of the destination environment. 60 In sum, while we cannot definitively rule out migration effects, available evidence indicates that any such effects do not materially alter our findings.

More work is needed to examine whether the findings differ by population subgroup, such as by race/ethnicity and educational attainment level. The only demographic characteristic available in the data was sex. As state policies may disproportionately affect certain groups, future analyses that examine these differential impacts may be informative. For instance, changing state policy contexts may help explain the disproportionate increase in mortality rates observed among low‐educated adults, 61 , 62 which has been pronounced in certain states and nonexistent in others. 57 Additional insights into the role of state policies on longevity may also emerge by examining whether the 18 policy measures have synergistic effects. For example, the association between labor policies and life expectancy may be stronger in states with certain tax policies. Investigating such synergies is beyond the scope of this paper and requires a methodology for handling the large number of potential synergies (eg, 153 possible two‐way interactions and 816 possible three‐way interactions among the 18 policy measures).

Policy Implications

States have become a battleground for policymaking, 21 , 22 with potentially profound implications for the health and well‐being of Americans. The striking differences in states’ policy contexts today have deep roots and a robust momentum with many individual, corporate, and organizational stakeholders. 22 , 63 In fact, a study of US policymaking during 1981‐2006 reported that wealthy individuals and organized groups representing business interests were the driving forces behind US public policy, while average Americans had little impact on public policy. 64 Hertel‐Fernandez reached a similar conclusion, claiming that US state policymaking had become “captured” by small groups of well‐resourced individuals and groups with a pro‐business policy agenda. 22 This phenomenon may have escalated in the past decade. For instance, the 2010 midterm elections marked a watershed moment, with a rapid adoption across conservative states of nearly identical state‐level policies on issues such as limited labor protections, voter identification requirements, and stand‐your‐ground laws. 22 Our findings imply that geographic disparities in life expectancy will grow even larger if US state policy contexts move increasingly to more liberal or conservative extremes. Moreover, they imply that some state policies could be cutting lives short and increasing morbidity and disability, which could ultimately raise medical care costs and adversely affect the states’ economies.

With the caveat that our results do not prove that state policies have a causal effect on longevity, our findings point to potential policy levers that may improve life expectancy, notably those that protect the environment, provide tobacco and firearm regulations, and ensure labor, reproductive, and civil rights. However, we caution that this does not imply that other policies are inconsequential. Some policies may have needed to vary over time even more than they did during the study period in order for our models to have detected an association with life expectancy (for a display of the variation over time, see online appendix Figure A2). Although the importance of any specific domain in our study should be interpreted cautiously, the overarching conclusion is clear: states that have invested in their populations’ social and economic well‐being by enacting more liberal policies over time tend to be the same states that have made considerable gains in life expectancy.

Monitoring health, well‐being, and life expectancy at the subnational level is crucial. The high‐profile annual reports on life expectancy from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention focus on national trends and can give a false sense of stability. Even the recent reports of declining US life expectancy mask more dramatic declines occurring at the state level. We recommend that national health reports prominently feature information by state. We also recommend that large‐scale efforts to track US health and longevity, as well as international comparisons in scientific research, include data on US states. Several such scorecards have recently been developed. 17 , 65 , 66

Conclusions

Americans’ opportunities and constraints for living a healthy life are strongly shaped by structural conditions. Other factors such as individual behaviors and medical care are also important and must be part of a comprehensive strategy to improve population health and reduce inequalities; nevertheless, as McCartney and colleagues argued, “there should be no pretense or illusion that health inequalities can be eliminated, or even meaningfully reduced, without a primary focus on structural factors.” 67 (p225) This study focused on US state policy contexts as an increasingly important structural factor. Our findings underscore that progress in understanding—and reversing—the troubling trends and growing disparities in US life expectancy requires attention to state policy contexts, their dynamic changes in recent decades, and the forces behind those changes.

Funding/Support: This research was supported in part by grant R01AG055481, “Educational Attainment, Geography, and U.S. Adult Mortality Risk,” awarded by the National Institute on Aging (PI: Montez), and an Andrew Carnegie Fellowship awarded by the Carnegie Foundation of New York (PI: Montez).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No conflicts were reported.

Acknowledgments: We thank the three reviewers for insightful comments and critiques. We also thank the members of the Policy, Place, and Population Health (P3H) Lab at Syracuse University for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Supporting information

Table A1. Coefficients (Standard Errors) Predicting Female Life Expectancy, 1970–2014

Table A2. Coefficients (Standard Errors) Predicting Female Life Expectancy From Ancillary Analyses

Table A3. Coefficients (Standard Errors) Predicting Male Life Expectancy, 1970–2014

Table A4. Coefficients (Standard Errors) Predicting Male Life Expectancy From Ancillary Analyses

Table A5. Policy Scores for 11 Hypothetical Policy Contexts

Figure A1. Percentage Change in the Slope of US Life Expectancy After Adjusting for State Policy Contexts

Figure A2. Variability in Policy Scores Across States, 1970–2014

References

- 1. National Research Council . Explaining Divergent Levels of Longevity in High‐Income Countries. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ho JY, Hendi AS. Recent trends in life expectancy across high income countries: retrospective observational study. BMJ. 2018;362:k2562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Research Council . US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Avendano M, Kawachi I. Why do Americans have shorter life expectancy and worse health than do people in other high‐income countries? Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:307‐325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banks J, Marmot M, Oldfield Z, Smith JP. Disease and disadvantage in the United States and in England. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2037‐2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McGinnis JM, Williams‐Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2002;21(2):78‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ho J. Mortality under age 50 accounts for much of the fact that US life expectancy lags that of other high‐income countries. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2013;30(3):459‐467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martinson ML, Teitler JO, Reichman NE. Health across the life span in the United States and England. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(8):858‐865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Avendano M, Kok R, Glymour M, et al. Do Americans have higher mortality than Europeans at all levels of the education distribution? a comparison of the United States and 14 European countries In: Crimmins EM, Preston SH, Cohen B, eds. International Differences in Mortality at Older Ages: Dimensions and Sources. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010:313‐332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bambra C, Smith KE, Pearce J. Scaling up: the politics of health and place. Soc Sci Med. 2019;232:36‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beckfield J, Bambra C. Shorter lives in stingier states: social policy shortcomings help explain the US mortality disadvantage. Soc Sci Med. 2016;171:30‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deregulation Montez JK., devolution, and state preemption laws’ impact on U.S. mortality trends. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(11):1749‐1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Montez JK, Hayward MD, Zajacova A. Educational disparities in U.S. adult health: U.S. states as institutional actors on the association. Socius. 2019;5:1‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zajacova A, Montez JK. Macro‐level perspective to reverse recent mortality increases. Lancet. 2017;389(10073):991‐992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bradley EH, Taylor LA. The American Health Care Paradox: Why Spending More Is Getting Us Less. New York, NY: Public Affairs; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bradley EH, Sipsma H, Taylor LA. American health care paradox—high spending on health care and poor health. QJM. 2017;110(2):61‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. United States Mortality Database . https://usa.mortality.org/. Accessed June 15, 2019.

- 18. Life expectancy at birth: total (years) . The World Bank website. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sp.dyn.le00.in?name_desc=false. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- 19. Wilmoth JR, Boe C, Barbieri M. Geographic differences in life expectancy at age 50 in the United States compared with other high‐income countries In: Crimmins EM, Preston SH, Cohen B, eds International Differences in Mortality at Older Ages: Dimensions and Sources. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011:333‐366. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Avendano M, Kawachi I. Invited commentary: the search for explanations of the American health disadvantage relative to the English. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(8):866‐869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grumbach JM. From backwaters to major policymakers: policy polarization in the states, 1970–2014. Perspectives on Politics. 2018;16(2):416‐435. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hertel‐Fernandez A. State Capture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Conlan TJ. From New Federalism to Devolution: Twenty‐five Years of Intergovernmental Reform. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carr D, Adler S, Winig B, Montez JK. Equity‐first: a normative framework for assessing the role of preemption in public health. Milbank Q. 2020;98(1):131‐149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Riverstone‐Newell L. The rise of state preemption laws in response to local policy innovation. Publius. 2017;47(3):403‐425. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huizar L, Lathrop Y. Fighting Wage Preemption: How Workers Have Lost Billions in Wages and How We Can Restore Local Democracy. New York, NY: National Employment Law Project; 2019. https://www.nelp.org/publication/fighting-wage-preemption/. Accessed September 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Isaacs J, Healy O, Peters HE. Paid Family Leave in the United States. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Komro KA, Livingston MD, Markowitz S, Wagenaar AC. The effect of an increased minimum wage on infant mortality and birth weight. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(8):1514‐1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rossin M. The effects of maternity leave on children's birth and infant health outcomes in the United States. J Health Econ. 2011;30(2):221‐239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stearns J. The effects of paid maternity leave: evidence from temporary disability insurance. J Health Econ. 2015;43:85‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Van Dykea ME, Komrob KA, Shaha MP, Livingstonc MD, Kramera MR. State‐level minimum wage and heart disease death rates in the United States, 1980–2015: a novel application of marginal structural modeling. Prev Med. 2018;112:97‐103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Erikson RS, MacKuen MB, Stimson JA. The Macro Polity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Montez JK, Zajacova A, Hayward MD. Explaining inequalities in women's mortality between U.S. states. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:561‐571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Farrelly MC, Loomis BR, Han B, et al. A comprehensive examination of the influence of state tobacco control programs and policies on youth smoking. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):549‐555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boehmke FJ, Skinner P. State policy innovativeness revisited. State Politics & Policy Quarterly. 2012;12(3):303‐329. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boehmke FJ, Brockway M, Desmarais B, et al. State Policy Innovation and Diffusion (SPID) Database v1.0 . Harvard Dataverse; 2018. 10.7910/DVN/CVYSR7. Accessed July 16, 2019. [DOI]

- 37. Joinpoint Regression Program . Version 4.7.0.0. Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute; 2019.

- 38. Joinpoint Help Manual 4.7.0.0 . Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute; 2019. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/Joinpoint_Help_4.7.0.0.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- 39. Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Buchanich JM, Bobby KJ, Zimmerman EB, Blackburn SM. Changes in midlife death rates across racial and ethnic groups in the United States: systematic analysis of vital statistics. BMJ. 2018;362:k3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959–2017. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996‐2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Driscoll JC, Kraay AC. Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Rev Econ Statist. 1998;80:549‐560. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16 . StataCorp LLC; 2019.

- 43. Tapia Granados JA, House JS, Ionides EL, Burgard S, Schoeni RS. Individual joblessness, contextual unemployment, and mortality risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(3):280‐287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bradley EH, Canavan M, Rogan E, et al. Variation in health outcomes: the role of spending on social services, public health, and health care, 2000–2009. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):760‐768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pacula RL, Smart R. Medical marijuana and marijuana legalization. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13:397‐419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Birnbaum LS, Jung P. From endocrine disruptors to nanomaterials: advancing our understanding of environmental health to protect public health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(5):814‐822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McGowan AK, Lee MM, Meneses CM, Perkins J, Youdelman M. Civil rights laws as tools to advance health in the twenty‐first century. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:185‐204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State‐level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2275‐2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Meltzer DO, Chen Z. The impact of minimum wage rates on body weight in the United States In: Grossman M, Mocan N, eds. Economic Aspects of Obesity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2011:17‐34. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Strully KW, Rehkopf DH, Xuan Z. Effects of prenatal poverty on infant health: state earned income tax credits and birth weight. Am Sociol Rev. 2010;75(4):534‐562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Turnaway Study . ANSIRH website. https://www.ansirh.org/research/turnaway-study. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 52. Anglemyer A, Horvath T, Rutherford G. The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:101‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carpenter C, Cook PJ. Cigarette taxes and youth smoking: new evidence from national, state, and local Youth Risk Behavior Surveys. J Health Econ. 2008;27(2):287‐299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Muennig PA, Mohit B, Wu J, Jia H, Rosen Z. Cost effectiveness of the earned income tax credit as a health policy investment. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(6):874‐881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lenhart O. The effects of state‐level earned income tax credits on suicides. Health Econ. 2019;28:1476‐1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. New Engl J Med. 2012;367:1025‐1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Montez JK, Zajacova A, Hayward MD, Woolf S, Chapman D, Beckfield J. Educational disparities in adult mortality across U.S. states: how do they differ and have they changed since the mid‐1980s? Demography. 2019;56(2):621‐644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fenelon A. Geographic divergence in mortality in the United States. Popul Dev Rev. 2013;39(4):611‐634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hernández‐Murillo R, Ott LS, Owyang MT, Whalen D. Patterns of interstate migration in the United States from the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Fed Reserve Bank St Louis Rev. 2011;93(3):169‐185. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Johnson JE, Taylor EJ. The long run health consequences of rural‐urban migration. Quant Econom. 2019;10(2):565‐606. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Case A, Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non‐Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(49):15078‐15083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Montez JK, Hummer RA, Hayward MD, Woo H, Rogers RG. Trends in the educational gradient of U.S. adult mortality from 1986 through 2006 by race, gender, and age group. Res Aging. 2011;33(2):145‐171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. MacLean N. Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right's Stealth Plan for America. New York, NY: Viking; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gilens M, Page BI. Testing theories of American politics: elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspect. Politics. 2014;12(3):564‐581. [Google Scholar]

- 65. The health of the states (HOTS) . Center on Society and Health, Virginia Commonwealth University website. https://societyhealth.vcu.edu/work/the-projects/the-health-of-the-states.html. Published October 26, 2016. Accessed May 6, 2020.

- 66. Berenson J, Li Y, Lynch J, Pagán JA. Identifying policy levers and opportunities for action across states to achieve health equity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1048‐1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. McCartney G, Collins C, Mackenzie M. What (or who) causes health inequalities: theories, evidence, and implications? Health Policy. 2013;113:221‐227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table A1. Coefficients (Standard Errors) Predicting Female Life Expectancy, 1970–2014

Table A2. Coefficients (Standard Errors) Predicting Female Life Expectancy From Ancillary Analyses

Table A3. Coefficients (Standard Errors) Predicting Male Life Expectancy, 1970–2014

Table A4. Coefficients (Standard Errors) Predicting Male Life Expectancy From Ancillary Analyses

Table A5. Policy Scores for 11 Hypothetical Policy Contexts

Figure A1. Percentage Change in the Slope of US Life Expectancy After Adjusting for State Policy Contexts

Figure A2. Variability in Policy Scores Across States, 1970–2014