Abstract

Introduction

Despite a recent meta-analysis including 31 randomised controlled trials comparing methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder, important knowledge gaps remain regarding the long-term effectiveness of different treatment modalities across individuals, including rigorously collected data on retention rates and other treatment outcomes. Evidence from real-world data represents a valuable opportunity to improve personalised treatment and patient-centred guidelines for vulnerable populations and inform strategies to reduce opioid-related mortality. Our objective is to determine the comparative effectiveness of methadone versus buprenorphine/naloxone, both overall and within key populations, in a setting where both medications are simultaneously available in office-based practices and specialised clinics.

Methods and analysis

We propose a retrospective cohort study of all adults living in British Columbia receiving opioid agonist treatment (OAT) with methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone between 1 January 2008 and 30 September 2018. The study will draw on seven linked population-level administrative databases. The primary outcomes include retention in OAT and all-cause mortality. We will determine the effectiveness of buprenorphine/naloxone vs methadone using intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses—the former emulating flexible-dose trials and the latter focusing on the comparison of the two medication regimens offered at the optimal dose. Sensitivity analyses will be used to assess the robustness of results to heterogeneity in the patient population and threats to internal validity.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol, cohort creation and analysis plan have been approved and classified as a quality improvement initiative exempt from ethical review (Providence Health Care Research Institute and the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics). Dissemination is planned via conferences and publications, and through direct engagement and collaboration with entities that issue clinical guidelines, such as professional medical societies and public health organisations.

Keywords: substance misuse, epidemiology, primary care, public health, statistics & research methods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

British Columbia’s single-payer system represents an ideal setting for direct comparisons at the population level and within key subgroups.

An intent-to-treat analysis with both instrumental variable and high-dimensional propensity score matching techniques will emulate trials featuring flexible dosing regimens.

A per-protocol analysis, implemented with G-estimation methods, will provide a direct comparison of the treatment regimens administered at clinical guideline-recommended doses and other guideline-recommended clinical practices.

Potential uncontrolled confounding and other threats to validity will be assessed via a range of sensitivity analyses and bias analysis.

Introduction

Evidence supporting the use of opioid agonist treatment (OAT) for long-term treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) is well established.1 Nonetheless, a consensus study report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, with support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, recently highlighted the need for further studies to determine the most appropriate medication for key population subgroups and the comparative effectiveness of different medications over the long term.2 The report further noted the refining of treatment protocols for effective use of existing medications as a priority topic. This is due in part to the fact that much of the existing evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) has been generated using protocols not representative of current clinical practice guidelines (which themselves are based on limited evidence) and within restrictive study cohorts over short durations (eg, ranging from 6 to 52 weeks) that do not account for the chronic nature of OUD. The lack of consistent, high-quality evidence, therefore, continues to challenge informed decision-making when determining the best treatment option for individuals with OUD.

Numerous RCTs have indicated that buprenorphine and methadone are effective treatments for OUD.3–5 The effectiveness of methadone as a therapeutic treatment for OUD is the most established among the various forms of OAT.6 Methadone is a synthetic opioid agonist with high μ-opioid receptor binding affinity,7 but has a narrow therapeutic index, long elimination half-life and potential for interactions with alcohol and other drugs; properties which increase its risk of toxicity and other adverse effects.8 Buprenorphine is a safe and effective alternative to methadone treatment,9 working as a partial agonist with high affinity at the μ-opioid receptor and an antagonist at the κ-opioid receptor. Compared with methadone, buprenorphine features an improved safety profile with shorter induction; a milder side effect profile; milder withdrawal symptoms and fewer drug interactions; decreased risk of overdose due to a partial agonist ‘ceiling effect’ and reduced risks of respiratory depression.8 Buprenorphine additionally may offer a decreased risk of injection, and therefore, harms related to diversion when taken in the buprenorphine/naloxone formulation. As a result, most settings have allowed more flexible and take-home dosing schedules earlier in the course of treatment.8

Regarding the comparative effectiveness of OAT regimens, evidence from randomised studies is mixed and dependent on whether a fixed or flexible dosing schedule was assigned.4 Retention in buprenorphine was less effective than methadone when dosing was flexible (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.95); however, these differences were not observed when buprenorphine dosages were fixed at medium (7–16 mg/day) (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.10) and high (≥16 mg/day) doses (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.20 to 3.16).4 ‘Flexible-dose’ studies were also conducted where doses were adjusted to individual need; however, several RCTs using such protocols reported maximum dose limits below the recommended effective maintenance or induction dosage for buprenorphine.4 Many of the flexible-dose studies yielded equivalent results for buprenorphine compared with methadone; although this finding was not supported in a systematic review integrating earlier studies with more recent trials.4 The implications of these findings are unclear as fixed-dosing regimens are not recommended in the clinical practice. Further, substantial heterogeneity across studies included in this meta-analysis with respect to participant selection and exclusion criteria, disease severity, study design, dosing protocols, observation times and how retention is measured limits generalisability, particularly to key populations excluded from the RCTs. Consequently, there are several factors which limit conclusions drawn from previous studies in the comparative effectiveness between buprenorphine and methadone, and challenge their applicability to clinical practice.

Restricted participant inclusion criteria in previous RCTs meta-analysed by Mattick et al4 have resulted in an unrepresentative sample of the population living with OUD included in these studies. People with OUD (PWOUD) have been observed to have a high prevalence of comorbid conditions, such as mental health disorders, other substance use disorders, respiratory illness, chronic pain, Hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV/AIDS.10–12 We previously reported a high prevalence of mental health disorders (66%), chronic pain (53%), substance use disorders (43%) and alcohol use disorders (20%) in a recent population-based study of PWOUD in British Columbia (BC).13 A majority of the RCTs included in the Cochrane review excluded individuals with major psychiatric medical conditions, other serious conditions, previous receipt of OAT and those with codependence on other substances, such as stimulants, alcohol, cannabis and sedatives. Additionally, a vast majority of these studies investigated treatment among heroin users before the era of fentanyl and the dramatic rise in synthetic opioid use. Furthermore, most of the RCTs did not investigate OAT effectiveness among special populations outlined in the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) guidelines, particularly through the exclusion of pregnant women and youth. A prior Cochrane review conducted by Minozzi et al14 investigating OAT efficacy in pregnant women with OUD, reported insufficient evidence to draw firm conclusions about the equivalence of the treatments for all outcomes including retention.

Limited observation periods afforded by the RCTs included in the Mattick et al study provided an insufficient timeframe to determine retention and long-term treatment response.15 The evaluation periods for RCTs in the review ranged from 6 to 48 weeks in the flexible-dose trials, 18 to 24 weeks in the low dose RCTs, 13 to 52 weeks in the medium-dose trials and 17 weeks in the one high-dose RCT included. The heterogeneity of study periods across these trials limits conclusions on retention. Further challenging conclusions is the variation in the statistical methods that were employed to investigate this outcome.

Inconsistencies among RCTs regarding the formulation of OAT administered among participants may influence treatment outcomes due to differences in their bioavailability and effectiveness. Mattick et al indicate nearly half of the RCTs included in their analysis used aqueous ethanol-based buprenorphine solutions, which have been reported to have a higher bioavailability resulting in nearly 50% higher peak plasma levels than marketed tablet forms.4 16 In other settings such as BC, buprenorphine/naloxone is predominantly available and prescribed in the sublingual tablet formulation. Only three studies included the buprenorphine/naloxone tablet formulation, (as opposed to buprenorphine alone), further limiting available data for this specific OAT option.

Buprenorphine’s relative inferiority in retention compared with methadone reported in Mattick et al was suggested to have been influenced by inadequate buprenorphine dosage during induction and maintenance in several of the referenced studies.17–19 One study noted their buprenorphine doses may have been too low during the induction phase (2–6 mg during the first week) and not increased quickly enough to retain patients, while rapid induction of doses up to 12–16 mg of buprenorphine may be required to maximise retention.18Another RCT included in the flexible dosing analysis noted that their buprenorphine upper dose limit of 8 mg might have resulted in their high buprenorphine dropout rate.17 Mattick et al report equivalent outcomes in retention between buprenorphine and methadone during fixed-doses of buprenorphine above 7 mg. Seven of the eleven flexible-dose studies found no difference in retention between methadone and buprenorphine, with mean buprenorphine doses ranging from 9 to 16 mg/day.20–24 The other four flexible-dose studies, which reported methadone’s superior retention to buprenorphine, indicated mean buprenorphine doses ranging from 2 to 16 mg/day.17–19 25 These findings may suggest retention is more likely observed at higher buprenorphine dosage even in flexible dosing practice. Whether the same results are observed with the buprenorphine/naloxone formulation will be important to clarify.

Over half of the studies investigating retention included in the Cochrane meta-analysis involved a form of individual or group counselling or cognitive–behavioural therapy; however, the contribution of this treatment to study outcomes is unclear. Numerous studies have indicated that counselling or psychotherapy does not improve buprenorphine retention26–28; however, several studies report contrasting results.29–31 Given the inconsistency across the studies with respect to adjunct psychosocial intervention, it is unclear how these additions may have affected retention and influenced conclusions from the meta-analysis.

In light of these challenges, observational studies may provide additional clarity on the comparative effectiveness of methadone versus buprenorphine, as well as the impacts of flexible dosing and adjunctive psychosocial interventions. Real-world data can provide a powerful basis to improve healthcare decision making and offer valuable insights beyond the restricted scope of RCTs.32 However, findings from observational studies on this topic are limited by confounders, particularly those which are time-variant, requiring advanced statistical methods to account for their effects. Nonetheless, decision-makers are increasingly relying on real-world data for evidence on treatment effectiveness and its relevance to specific populations.32 33 To this end, methadone has demonstrated better retention relative to buprenorphine/naloxone in observational settings in Australia and the USA,34–36though selection bias and uncontrolled (residual) confounding may bias these comparisons.8 This comparison is challenged by uncontrolled confounding, structural differences in the setting of care (opioid treatment programmes for methadone and office-based treatment for buprenorphine in the USA) and the mechanism by which PWOUD are selected, or select themselves into one form of treatment over another.

Buprenorphine/naloxone was made the recommended first-line treatment for OUD in 2017 in BC. However, BC’s guidelines differ from ASAM and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s,37 38 in part due to the conflicting results of the fixed-dosing and flexible-dosing studies as well as differences in medication availability. Specifically, in Canada, methadone is available through primary care physicians and community pharmacies, whereas US regulations limit methadone availability to specialised methadone clinics. Additionally, individuals receiving buprenorphine may safely switch to methadone if buprenorphine’s clinical effect is insufficient, with one study demonstrating their equal efficacy with a stepped care strategy.39 Furthermore, the improved safety profile of buprenorphine/naloxone and resulting reductions in the potential harms from diversion have prompted reduced restrictions on take-home dosing for this treatment modality.8 While this practice may positively influence treatment retention, it was not permitted in the majority of RCTs included in the Cochrane review.

BC is a single-payer system featuring limited copayment for medications, with both forms of OAT available in office-based settings. The availability of all forms of OAT in office-based settings in BC allows for a direct comparison that is not possible in naturalistic settings in the US, given that methadone can be prescribed only in stand-alone opioid treatment programmes. BC is also free of waiver policies, patient limits and other policies that are not supported by evidence or employed for other medical disorders.40 With a population-based linked administrative dataset featuring daily dispensation data for over 78 000 person-years on methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone, we are uniquely positioned to contribute high-quality, real-world evidence to resolve these issues.

During a period of heightened OUD-related mortality, identifying effective treatment options is critical in bridging the gap between research evidence and evidence-based care for the clinical management of OUD. We propose a retrospective cohort study with both intention-to-treat and per-protocol (or in this case per clinical guideline) analytical strategies to determine the effectiveness of buprenorphine/naloxone versus methadone in achieving sustained retention and delaying hospitalisation and mortality. These analytical strategies allow for adequate comparisons to the previous clinical trials, while respecting the underlying data generating process. We aim to determine the comparative effectiveness both overall and within key populations through conducting analyses that reflect real-world practice and adherence to clinical guidelines.

Methods

Study design

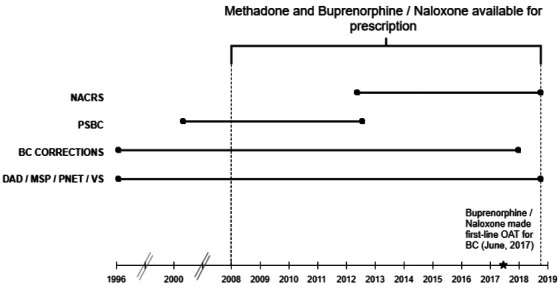

The study is a retrospective observational study based on a provincial cohort of all BC OAT recipients from 1 January 2008 to 30 September 2018. The study period (figure 1), corresponds to the period in which buprenorphine/naloxone, was available for prescription in BC, although we have methadone prescription records since 1 January 1996. The cohort will be defined using a validated list of Drug Identification Numbers specific to OAT medications. OAT episodes will be determined from dispensed prescription database records throughout the study period. The current iteration of the cohort features seven linked population-level administrative databases, including the Medical Services Plan (capturing physician billing records),41 the Discharge Abstract Database (hospitalisations),42 PharmaNet (drug dispensations),43 Vital Statistics (death and their underlying causes),44 BC Corrections (capturing incarceration in provincial prisons),45 the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System database (capturing all emergency department visits),46 and the Perinatal database (maternal and child health for all provincial births).47 Additional information on datasets is provided in online supplementary appendix table A1. Eligibility for inclusion in the study cohort will be individuals with receipt of OAT (either methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone) during the study period. As of the most recent data update, 30 September 2018, our study cohort (individuals initiating OAT after 1 January 2008) consisted of 47 563 individuals with an average duration of follow-up of 60 months (from first OAT dispensation to death, administrative censorship or the end of study follow-up period).

Figure 1.

Study-specific dates, databases and their data extraction period. Data extraction time window: BC, British Columbia, Canada; BC corrections (1 January 1996–31 December 2017); DAD, discharge Abstract database (1 January 1996–30 September 2018); MSP, medical services plan (1 January 1996–30 September 2018); NACRS, national ambulatory care reporting system (1 April 2012–30 September 2018); OAT, opioid agonist treatment; PNET, PharmaNet (1 January 1996–30 September 2018); PSBC, perinatal services British Columbia (10 March 2000–14 August 2012); VS, vital statistics (1 January 1996–30 September 2018).

bmjopen-2019-036102supp001.pdf (91.1KB, pdf)

We will apply specific exclusion criteria in sensitivity analyses for comparison with recent RCTs, and to generate evidence accounting for heterogeneity in key populations identified in the ASAM National Practice guidelines, including pregnant women, individuals with pain, adolescents, individuals with co-occurring mental disorders and individuals in the criminal justice system.48 Case-finding algorithms, applied to address possible misclassification in outpatient and hospital International Classification of Diseases 9th/10th revision (ICD-9/10 codes), will be used to attribute other, OUD-related chronic conditions, including mental health conditions, other substance use disorders, HIV, HCV and chronic pain (online supplementary appendix tables A2, A3).

Outcomes

The primary exposure is a binary indicator for receipt of at least one dispensation of OAT (either methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone). Retention can then be measured at daily, weekly or monthly time intervals. The primary outcomes of interest are (1) length of continuous retention in OAT; (2) hospitalisation and (3) all-cause mortality. If a prescription was supplied for more than 1 day of OAT medication, we assumed that the individual received OAT for the duration of days that the medication was prescribed. We defined continuous OAT retention (OAT episode) as the time interval during which an individual received OAT with no breaks in days dispensed lasting longer than 5 days for methadone and no longer than 6 days for buprenorphine/naloxone. These objective discontinuation criteria were based on BC guidelines recommending resetting starting doses after these durations of non-compliance to ensure safety.11 Our data do not capture OAT receipt in inpatient settings, and therefore, we assumed that those who started OAT prior to their hospitalisation were retained in treatment throughout the duration of their hospitalisation. Initiation and subsequent reinitiation of OAT receipt will be determined from medication dispensation records in PharmaNet and all-cause mortality from vital statistics data.

Follow-up

Each individual will be followed from OAT initiation until either administrative lost to follow-up or death. To account for out-of-province migration, administrative lost to follow-up will be defined as no health service utilisation record in any of the linked databases for at least 66 months prior to the end of study follow-up. The 66-month cut-off was empirically determined based on the distribution of gaps between hospitalisation records, physician billing records and drug dispensations over the entire data extraction time frame.13 49

Analysis plan

Our aim is to assess the effectiveness of buprenorphine/naloxone versus methadone in achieving sustained retention and delaying mortality, and we propose to conduct intention-to-treat and per-protocol (per-clinical guideline) analyses. We will report the comparative effectiveness as a relative risk in order for our results to be comparable with clinical evidence from RCTs. An intention-to-treat analysis allowing for flexible dosing schedules as set by prescribing physicians will focus on an individual’s outcome at the end of follow-up, adjusting for selection bias. High-dimensional propensity score (hdPS) matching and instrumental variables (IVs) estimation will control for measured and unmeasured factors that may systematically influence the selection of either buprenorphine/naloxone or methadone. However, in the presence of suboptimal dosing, the intention-to-treat effect is less meaningful for clinical decision making.50 A longitudinal per-protocol analysis, which censors patients once they deviate from the study protocol, will be used to estimate the comparative effectiveness of each medication regimen when offered at the recommended dose per clinical guidelines.51

Intention-to-treat approach

Accounting for factors that may influence which individuals receive buprenorphine/naloxone versus methadone is one of the key challenges for estimating the causal relationship between treatment and outcome in the comparative effectiveness of methadone versus buprenorphine/naloxone. An intention-to-treat approach, allowing for dosing schedules as set by prescribing physicians, therefore emulating a flexible-dose trial, will focus explicitly on adjusting for uncontrolled confounders that influence treatment selection. We propose two complementary estimation strategies—hdPS matching and IVs—based on different assumptions to account for unmeasured confounders that may influence the selection of either buprenorphine/naloxone or methadone. As these assumptions are not explicitly testable, concordance in findings will strengthen our inferences.

hdPS estimation

Like covariate adjustment in standard multiple regression, propensity score matching is a means of controlling for potential bias due to measured confounders. The probability of treatment selection is modelled as a function of measured covariates among individuals. Controls are matched to treated individuals based on their estimated propensity score, which is the individual probability of receiving the medication.

Applications with investigator-selected covariates have found this approach controls confounding comparably to traditional multiple regression.52 Residual confounding due to unmeasured variables is an obvious limitation of both approaches, however. hdPS is a semiautomated data-driven approach to identify potentially important proxy variables from administrative data for inclusion in propensity score models.53 It identifies covariates collected for billing and routine administrative purposes as proxies for uncontrolled confounders, eliminating those with very low prevalence and minimal potential for controlling bias. In the final hdPS step, propensity score techniques are used to adjust for the selected investigator-specified covariates and proxy variables identified as important by the hdPS algorithm. Comparisons of the performance of the hdPS against investigator-specified propensity scores constructed with health administrative and clinical registry-based data have generally found improved performance, approaching that of clinical registry-based analyses.54

IV estimation

IV methods are a common approach to handling unmeasured confounders, where selection into a treatment group (ie, those accessing buprenorphine/naloxone compared with methadone) is influenced by factors that may not be observed.55 The goal of IV methods is to reduce confounding bias without measuring all factors driving treatment decisions. Typical IV methods require a variable—the ‘instrument’—that meets three conditions: (1) the instrument is monotonically associated with the treatment; (2) the instrument does not affect the outcome except through treatment (also known as the exclusion restriction assumption) and (3) the instrument does not share any uncontrolled causes with the outcome (is not itself confounded).

Physician preference has been used as an IV in prior comparative effectiveness applications.56 In a recent analysis on the determinants of treatment selection, we found unexplained (residual) between-physician variance accounted for 28.4% of the explained variation in the odds of selecting buprenorphine/naloxone whereas the unexplained between-individual variance accounted for 18.5%.57 Physician preference will be measured in our application by the prescriber’s selection of medication regimen (methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone) for their most recent OAT-naïve clients. This IV will serve as a starting point for our analysis, although we will compare the relative performance of this measure (and similar variations, ie, preference in the past 20 naïve patients, etc), with other instruments noted in a recent review.56

We will follow current methodological standards for selection, validation and reporting of IVs.55 Validation entails an empirical assessment of condition 1 above, and we will conduct F-tests from the first-stage regression to support this condition. However, there is less consensus on assessing conditions 2 and 3. In following Swanson and Hernán,55 we propose to assess condition 2 using clinical knowledge of a scientific advisory committee to build a case that the instrument does not affect the outcome except through treatment (ie, that one individual’s potential outcomes are not affected by the choice of medication for other individuals). For condition 3, we propose to show empirically that the proposed IVs are not associated with the available covariates listed in (table 1).24 55 56 58–74 We will also consider alternative empirical approaches for assessing conditions 2 and 3, consistent with recommendations of Glymour et al.75

Table 1.

Potential confounding variables affecting opioid agonist treatment retention

| Covariate | Association* | Quality of evidence†† (source) | Available? |

| Individual-related characteristics | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age | +MET retention | Level I15 | Yes |

| Marital status (married) | +MET retention | Level I15 | No§ |

| Employment status (employed) | +MET retention | Level I15 | Yes†,‡ |

| Gender (female) | +MET retention | Level I15 | Yes |

| Duration of treatment | +MET retention | Level I15 | Yes |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic or African American) |

- BUP retention | Level II58 | No§ |

| Living in rural area | - MET retention | Level II59 | Yes |

| Family history of addiction | - MET retention | Level II60 | No§ |

| Homelessness | - MET/BNX retention | Level II11 | Yes†,‡ |

| Incarceration | - MET/BNX retention | Level II11 | Yes |

| History of overdose | Risk factor for overdose | Level III1 | Yes‡ |

| Concurrent conditions | |||

| Psychiatric comorbidity: major depression |

+BUP retention | Level II61 | Yes¶ |

| Schizophrenia | - BUP retention | Level II61 | Yes¶ |

| Personality disorders | - BUP retention | Level II61 | Yes¶ |

| Severe withdrawal at beginning of treatment |

- BUP retention | Level I24 | No§ |

| Hepatitis C virus | +BUP retention | Level II11 | Yes¶ |

| Other substance use disorders | - BUP retention | Level II62 | Yes¶ |

| Severe chronic pain | Risk factor for overdose | Level III1 | Yes¶ |

| Respiratory disease | Risk factor for overdose | Level III1 | Yes¶ |

| Cocaine use on admission to OAT |

- BNX retention | Level II63 | No§ |

| Past-month injection drug use | - BNX retention | Level II83 | Yes** |

| Medication history | |||

| Use of sedatives within past 30 days of OAT |

- BUP retention | Level II65 | Yes |

| No of previous MET/BNX episodes | +MET retention | Level II66 | Yes |

| Previous receipt of MET/BNX | +BUP/MET retention | Level II67 | Yes |

| Receipt of psychiatric medication‡‡ | +BUP retention | Level II68 | Yes |

| Receiving high opioid prescription doses§§ |

Risk factor for overdose | Level III1 | Yes |

| Healthcare utilisation | |||

| Emergency department visits | - BUP retention | Level II62 | Yes |

| Psychiatric hospitalisations | - BUP retention | Level II62 | Yes |

| Treatment-related and contextual factors | |||

| Service provision | |||

| OAT in integrated care | +BUP retention | Level I69 | Yes |

| Behavioural therapy | +BUP/MET retention | Level I29 31 | Yes‡ |

| Positive relationships with service staff | +MET retention | Level II70 | No§ |

| Contextual factors | |||

| Poor availability and quality of heroin in drug supply |

+MET/BUP retention | Level II71 | No§ |

| OAT dosing | |||

| Insufficient BUP maintenance dose¶¶ | - BUP retention | Level II72 | Yes |

| Sufficient BUP maintenance dose*** | +BUP retention | Level I4 | Yes |

| High MET maintenance dose††† | +MET retention | Level I73 | Yes |

| Flexible-dose strategies (compared with fixed dosing) |

+MET retention | Level I73 | Yes |

+positive association; −negative association.

*Significant factors identified in studies.

†Plan I/C/G/Coverage (low-income Pharmacare coverage programme);.

‡Proxy variable.

§Factor not captured in datasets to be included in bias analysis.

¶Concurrent condition identified via ICD-9/10 diagnostic codes.

**Identified via case-finding algorithm.74

††Quality of evidence ratings: level I: systematic reviews, meta-analyses and randomised controlled trials; level II: cohort studies, case–control studies, case studies; level III: case reports, ideas, editorials, opinions (source: Cochrane review library https://consumers.cochrane.org/levels-evidence).

‡‡Antidepressant, antianxiety, antipsychotic and mood stabilising medications.

§§>90 morphine equivalents.

¶¶Maximum of 8 mg/day.

***Fixed dosing at medium (7–15 mg/day) or high doses (≥16 mg/day).

†††≥60 mg/day.

BNX, buprenorphine/naloxone; BUP, buprenorphine; iOAT, injectable opioid agonist treatment; MET, methadone; OAT, opioid agonist treatment.

The use of IVs is controversial, in part because conditions (2) and (3) listed above are not explicitly testable for unmeasured confounders.55 Others have warned of bias amplification if instruments are controlled in a conventional manner,76 and counterarguments have been made regarding the use of physician preference as an instrument.77 The choice between propensity score and IV approaches depends on whether the selection mechanism for treatment is identifiable or not, respectively. While both approaches have faced criticism, concordance in their results will strengthen the inference, while discordance (overall or within a given subgroup) may indicate a need for additional, possibly experimental, studies to validly estimate effects.

Per-protocol approach

G-methods including marginal structural modelling, use of the parametric G-formula (or G-computation) and G-estimation of structural nested models offer the advantage of controlling for time-varying confounders that may be acting as both a confounder and intermediate variable, simultaneously.78 In this application, a daily dose at or above the minimum effective dosing threshold may be the result of spending sufficient time in treatment to titrate up to this dose, among other considerations (including individual-level, prescriber-level and facility-level factors). In turn, higher daily dosing is associated with longer retention—the key aspect of the estimation problem requiring G-methods.

Of the three G-methods listed above, G-estimation of structural nested models is most appropriate in this application,79 80 as we are explicitly concerned with the comparative effect of methadone versus buprenorphine/naloxone at the optimal dose (≥80 mg/day for methadone; ≥16 mg/day for buprenorphine/naloxone).8 37 81 The interaction between dosage and time-varying factors can obscure the causal effect of treatment on the outcome, which necessitated the use of G-estimation. Specifically, we propose a structural nested accelerated failure time model.82 This model postulates that the length of time to the outcome (see the Section 2.2) under continuous exposure (treatment type at optimal dose) to be accelerated/decelerated by a factor to the length of time to the outcome if continuously unexposed83 (ie, on MET as opposed to BNX).

Taking as given the assumption of conditional exchangeability, the estimation procedure is a two-step iterative process that exploits the conditional independence between the exposure and potential outcomes. The first step estimates the counterfactual time-to-event outcome under no exposure as a function of observed variables, and the second step finds the G-estimate, the effect-parameter value that results in the treatment being unrelated to the potential outcome.82 83 The procedure is repeated at each time step, beginning at the final observation, moving backward until treatment initiation.

We will apply G-estimation on continuous OAT episodes to obtain the treatment effects of methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone, at the optimal dose, on the study outcomes. For each OAT episode, we will specify a model for the levels of OAT dosage to perform G-estimation, and then estimate the potential outcomes with a structural accelerated failure time model. To address for effect modification between time-varying factors, we will follow the setup presented by Vansteelandt and Sjolander.84

Covariate selection

While the assumption of no uncontrolled confounding cannot be verified in observational settings, we adjust for all potential confounders available within our linked database.85 We identified these covariates by conducting a systematic literature review for articles published up to 2 September 2019 to identify factors associated with OAT retention. The following search string was included in PubMed: (“‘opiate substitution treatment”[MeSH] OR “opioid agonist treatment’”[MeSH] OR “buprenorphine”[MeSH] OR “methadone”[MeSH]) AND (“retention”[MeSH] OR “determinants”[MeSH] OR “factors”[MeSH] OR “predictor”[MeSH]). The search was restricted to studies on humans reported in English and published after 31 December 2000 to ensure findings were relevant to current treatment options. A total of 55 articles resulted from this search, which were screened for inclusion. Table 1 highlights fixed and time-varying individual, contextual and treatment-related factors associated with OAT retention, whether these factors were positively or negatively associated with OAT retention and the quality of the underlying evidence. We specify factors captured (directly or with reasonable proxies) and not captured within our database, with the latter serving as candidates for probabilistic bias analysis. Alternately, machine learning algorithms will be used for covariate selection within the intention-to-treat analysis with hdPS, as described above. Additionally, we will consider the flexibility buprenorphine allows for take-home use (which was not permitted in the majority of RCTs included in the Cochrane review).

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

We will conduct a range of subgroup and sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our results and heterogeneity in treatment effects across key client subgroups. We specify a priori targets focusing on cohort restriction, timeline restriction, variable classification and model specification in table 2.34 86–89 Applicable results will be presented in tornado diagrams centred on the baseline relative risk from each analytical strategy. Secondary outcomes such as psychiatric hospitalisations, emergency department visits and incarceration may also be considered in additional sensitivity analysis. Any post hoc additions to this protocol will be identified as such in final reports.

Table 2.

Proposed subgroup and sensitivity analyses

| Proposed sensitivity analysis | Rationale | Application |

| Sample restriction | ||

| Pregnant women | To assess heterogeneity in the key populations identified in The American Society of Addiction Medicine national practice guidelines.48 | All |

| PWOUD with pain | All | |

| Adolescents | All | |

| PWOUD with mental health disorders* | All | |

| Individuals in the criminal justice system | All | |

| PWOUD with history of PO prescription prior to diagnosis | May provide indirect evidence of treatment effect for those who primarily misuse PO. | All |

| PWOUD in regions with highest fentanyl concentrations† | May provide indirect evidence of treatment effect for those who primarily misuse fentanyl. | All |

| PWOUD receiving care in Community Health Centres‡ | Assesses heterogeneity of treatment effect across clinical settings. | All |

| PWOUD receiving care in stand-alone physician practices§ | All | |

| Timeline restriction | ||

| Buprenorphine/naloxone as first-line OAT in BC¶ | To account for potential influence of this BC policy change on OAT selection.8 | All |

| Variable classification | ||

| Episode discontinuation: 3 days (MET) | Alternative discontinuation thresholds have been defined at 3 or 7 days (MET) and 4 or 14 days (BUP) in other studies and guidelines34 86 87 as opposed to discontinuation thresholds of 5 days (MET) and 6 days (BUP).8 | All |

| Episode discontinuation: 7 days (MET) | ||

| Episode discontinuation: 4 days (BUP) | ||

| Episode discontinuation: 14 days (BUP) | ||

| Episode discontinuation: Dose tapering** | To account for individuals discontinuing treatment after completing dose tapering, defined as ≤5 mg/day for MET and ≤2 mg/day BNX on the last day of OAT receipt. | All |

| Secondary outcome: drug-related hospitalisations | Treating hospitalisations by other causes as competing risks may provide a more direct effect of exposure on outcome. | All |

| Secondary outcome: Drug-related deaths | Treating deaths by other causes as competing risks may provide a more direct effect of exposure on outcome. | All |

| Application of alternate clinical guidelines | Pertaining to both minimum effective daily doses and policies surrounding dose carries. To be executed to tailor PP analyses to other settings. | PP |

| Allowing for medication switching †† | To account for individuals receiving BUP who switch to MET if withdrawal symptoms are not alleviated,39 and to account for individuals switching from MET to BUP. | All |

| Model specification | ||

| Bias analysis | To measure the association necessary to explain the observed treatment–outcome association attributable to unmeasured factors identified in table 1.88 | All |

| Determining the association between IVs and covariates | To empirically verify that our IVs do not share common observed causes with the outcomes. | ITT-IV |

| Leveraging prior causal assumptions | To determine whether the data are compatible with prior valid assumptions of residual confounding of positive residual confounding. | ITT-IV |

| Overidentification tests | To assess performance of multiple IVs. | ITT-IV |

*Conditions outlined in online supplementary appendix tables A2, A3.

†Restricted to the lower mainland Vancouver area after 1 April 2016 (declaration of public health emergency).

‡Physicians practising in community health centres are remunerated on the province’s ‘Alternative payment plan’89 as opposed to as indicated by the absence of physician billing record supporting OAT pharmacy dispensations.

§As indicated by prescription renewals from single physicians with low (<20 clients) OAT treatment loads.

¶From 5 June 2017 onwards.

**OAT episodes with completed tapers (with no record of reversion for at least 4 weeks) will be censored at the start of the tapering.

††Allowing continuous OAT episodes to account for switching from buprenorphine/naloxone to methadone, or from methadone to buprenorphine/naloxone as indicated by BC guidelines. If prescribed doses (during switching) do not follow BC guidelines, the observation will be censored in per-protocol analysis. We note that medication switches are intended to be captured within baseline ITT analyses.

BC, British Columbia; BUP, buprenorphine; ITT-IV, intention-to-treat instrumental variable; MET, methadone; OAT, opioid agonist treatment; PO, prescription opioid; PP, per-protocol; PWOUD, people with opioid use disorder.

Ethics and dissemination

This linked database was made available to the research team by BC Ministries of Health and Mental Health and Addiction as part of the response to the provincial opioid overdose public health emergency, and classified as a quality improvement initiative. Providence Health Care Research Institute and the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics determined the analysis met criteria for exemption per Article 2.5 of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans.90

This study will follow international guidelines for study conduct and reporting, including Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines,91 and the administration of the ‘Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies-of Interventions’ tool to a multidisciplinary scientific advisory committee for ex post evaluation. Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals electronically and in print.

This study will generate robust evidence on how competing forms of OAT compare in real-world practice over the long term, in the interest of improving retention in these essential92 and life-saving93 medications.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in the design of this study. Findings will be shared in consultation with local advocacy organisations of people who use drugs and people who have accessed OAT following completion of the analysis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MP conducted literature reviews and wrote the first draft of the article. TT, EK, NH and BN wrote key methodological components of the article and provided critical revisions. JB, SG, PG, EK, LCM, MM, RWP, US, MES, JIT, EW and BN aided in the methodological development and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. BN conceptualised and secured funding for the study. All authors approved the final draft.

Funding: This work was supported by a Health Canada Substance Use and Addictions Program Grant No. 1819-HQ-000036.

Disclaimer: The funding source was independent of the design of this study and did not have any role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, writing, or decision to submit results. All authors had full access to the results in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analysis.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet 2019;393:1760–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine Medications for opioid use disorder save lives, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmadi J. Methadone versus buprenorphine maintenance for the treatment of heroin-dependent outpatients. J Subst Abuse Treat 2003;24:217–20. 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. . Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;66:CD002207 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson RE, Eissenberg T, Stitzer ML, et al. . A placebo controlled clinical trial of buprenorphine as a treatment for opioid dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995;40:17–25. 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01186-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dole VP, Nyswander M. A medical treatment for Diacetylmorphine(heroin) addiction. A clinical trial with methadone hydrochloride. JAMA 1965;193:646–50. 10.1001/jama.1965.03090080008002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tetrault JM, Fiellin DA. Current and potential pharmacological treatment options for maintenance therapy in opioid-dependent individuals. Drugs 2012;72:217–28. 10.2165/11597520-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.British Columbia Centre on Substance Use (BCCSU) A guideline for the clinical management of opioid use disorder, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson RE, Jaffe JH, Fudala PJ. A controlled trial of buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence. JAMA 1992;267:2750–5. 10.1001/jama.1992.03480200058024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sproule B, Brands B, Li S, et al. . Changing patterns in opioid addiction: characterizing users of oxycodone and other opioids. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:e695:68–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Socías ME, Wood E, Kerr T, et al. . Trends in engagement in the cascade of care for opioid use disorder, Vancouver, Canada, 2006-2016. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;189:90–5. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen S, Lintzeris N, Bruno R, et al. . Benzodiazepine use among chronic pain patients prescribed opioids: associations with pain, physical and mental health, and health service utilization. Pain Med 2015;16:356–66. 10.1111/pme.12594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piske M, Zhou H, Min JE, et al. . The cascade of care for opioid use disorder: a retrospective study in British Columbia, Canada. Addiction 2020;115:1482–93. 10.1111/add.14947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minozzi S, Amato L, Bellisario C, et al. . Maintenance agonist treatments for opiate-dependent pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;12:Cd006318. 10.1002/14651858.CD006318.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farmani F, Farhadi H, Mohammadi Y. Associated factors of maintenance in patients under treatment with methadone: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict Health 2018;10:41–51. 10.22122/ahj.v10i1.488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nath RP, Upton RA, Everhart ET, et al. . Buprenorphine pharmacokinetics: relative bioavailability of sublingual tablet and liquid formulations. J Clin Pharmacol 1999;39:619–23. 10.1177/00912709922008236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer G, Gombas W, Eder H, et al. . Buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance for the treatment of opioid dependence. Addiction 1999;94:1337–47. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattick RP, Ali R, White JM, et al. . Buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance therapy: a randomized double-blind trial with 405 opioid-dependent patients. Addiction 2003;98:441–52. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00335.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petitjean S, Stohler R, Déglon JJ, et al. . Double-Blind randomized trial of buprenorphine and methadone in opiate dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2001;62:97–104. 10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00163-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson RE, Chutuape MA, Strain EC, et al. . A comparison of levomethadyl acetate, buprenorphine, and methadone for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1290–7. 10.1056/NEJM200011023431802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lintzeris N, Nielsen S, Benzodiazepines NS. Benzodiazepines, methadone and buprenorphine: interactions and clinical management. Am J Addict 2010;19:59–72. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magura S, Lee JD, Hershberger J, et al. . Buprenorphine and methadone maintenance in jail and post-release: a randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;99:222–30. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neri S, Bruno CM, Pulvirenti D, et al. . Randomized clinical trial to compare the effects of methadone and buprenorphine on the immune system in drug abusers. Psychopharmacology 2005;179:700–4. 10.1007/s00213-005-2239-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soyka M, Zingg C, Koller G, et al. . Retention rate and substance use in methadone and buprenorphine maintenance therapy and predictors of outcome: results from a randomized study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2008;11:641–53. 10.1017/S146114570700836X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kristensen Øistein, Espegren O, Asland R, et al. . [Buprenorphine and methadone to opiate addicts--a randomized trial]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2005;125:148–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ling W, Amass L, Shoptaw S, et al. . A multi-center randomized trial of buprenorphine-naloxone versus clonidine for opioid detoxification: findings from the National Institute on drug abuse clinical trials network. Addiction 2005;100:1090–100. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01154.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss RD, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, et al. . Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence: a 2-phase randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:1238–46. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore BA, Fiellin DA, Cutter CJ, et al. . Cognitive behavioral therapy improves treatment outcomes for prescription opioid users in primary care buprenorphine treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 2016;71:54–7. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voelker R. App AIDS treatment retention for opioid use DisorderApp AIDS treatment retention for opioid use DisorderNews from the food and drug administration. JAMA 2019;321:444–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen W, Hong Y, Zou X, et al. . Effectiveness of prize-based contingency management in a methadone maintenance program in China. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;133:270–4. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hser Y-I, Li J, Jiang H, et al. . Effects of a randomized contingency management intervention on opiate abstinence and retention in methadone maintenance treatment in China. Addiction 2011;106:1801–9. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03490.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berger ML, Sox H, Willke RJ, et al. . Good practices for real-world data studies of treatment and/or comparative effectiveness: recommendations from the joint ISPOR-ISPE special Task force on real-world evidence in health care decision making. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2017;26:1033–9. 10.1002/pds.4297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Medication-Assisted treatment for opioid use disorder study (MAT study). Available: https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/Medication-Assisted-Treatment-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Study.html

- 34.Bell J, Trinh L, Butler B, et al. . Comparing retention in treatment and mortality in people after initial entry to methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Addiction 2009;104:1193–200. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02627.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burns L, Gisev N, Larney S, et al. . A longitudinal comparison of retention in buprenorphine and methadone treatment for opioid dependence in New South Wales, Australia. Addiction 2015;110:646–55. 10.1111/add.12834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saxon AJ. Commentary on burns et al. (2015): retention in buprenorphine treatment. Addiction 2015;110:656–7. 10.1111/add.12865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kampman K, Jarvis M. American Society of addiction medicine (ASAM) national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. J Addict Med 2015;9:358–67. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment Medication-Assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs.(treatment improvement protocol (tip) series, no. 43. Rockville (MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), 2005. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64164/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kakko J, Grönbladh L, Svanborg KD, et al. . A stepped care strategy using buprenorphine and methadone versus conventional methadone maintenance in heroin dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:797–803. 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.College of Pharmacists of BC Opioid Agonist Treatment, 2019. Available: https://www.bcpharmacists.org/opioid-agonist-treatment

- 41.British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] Medical Services Plan (MSP) Payment Information File. British Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH, 2018. Available: http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/data/

- 42.British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations). British Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH, 2018. Available: http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/data/

- 43.British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] PharmaNet. British Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH, 2018. Available: http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/data/

- 44.BC Vital Statistics Agency [creator] Vital Statistics Deaths. British Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH, 2018. Available: http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/data/

- 45.Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General (PSSG) [creator] BC Corrections Dataset. British Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH, 2018. Available: http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/data/

- 46.British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS). British Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH, 2018. Available: http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/data/

- 47.Perinatal Services BC [creator] British Columbia Perinatal Data Registry. British Columbia Ministry of Health [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH, 2018. Available: http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/data/

- 48.The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) The ASAM national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pearce LA, Min JE, Piske M, et al. . Opioid agonist treatment and risk of mortality during opioid overdose public health emergency: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2020;368:m772. 10.1136/bmj.m772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S. Beyond the intention-to-treat in comparative effectiveness research. Clin Trials 2012;9:48–55. 10.1177/1740774511420743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murray EJ, Hernán MA. Adherence adjustment in the coronary drug project: a call for better per-protocol effect estimates in randomized trials. Clin Trials 2016;13:372–8. 10.1177/1740774516634335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shah BR, Laupacis A, Hux JE, et al. . Propensity score methods gave similar results to traditional regression modeling in observational studies: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:550–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneeweiss S, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, et al. . High-Dimensional propensity score adjustment in studies of treatment effects using health care claims data. Epidemiology 2009;20:512–22. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a663cc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Austin PC, Wu CF, Lee DS, et al. . Comparing the high-dimensional propensity score for use with administrative data with propensity scores derived from high-quality clinical data. Stat Methods Med Res 2020;29:568–88. 10.1177/0962280219842362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swanson SA, Hernán MA. Commentary: how to report instrumental variable analyses (suggestions welcome). Epidemiology 2013;24:370–4. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828d0590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davies NM, Smith GD, Windmeijer F, et al. . Issues in the reporting and conduct of instrumental variable studies: a systematic review. Epidemiology 2013;24:363–9. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828abafb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Homayra F, Hongdilokkul N, Piske M, et al. . Determinants of selection into buprenorphine/naloxone among people initiating opioid agonist treatment in British Columbia. Drug Alcohol Depend 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weinstein ZM, Kim HW, Cheng DM, et al. . Long-Term retention in office based opioid treatment with buprenorphine. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017;74:65–70. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang F, Lin P, Li Y, et al. . Predictors of retention in community-based methadone maintenance treatment program in pearl River delta, China. Harm Reduct J 2013;10:3. 10.1186/1477-7517-10-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pickens RW, Preston KL, Miles DR, et al. . Family history influence on drug abuse severity and treatment outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend 2001;61:261–70. 10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00146-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gerra G, Leonardi C, D'Amore A, et al. . Buprenorphine treatment outcome in dually diagnosed heroin dependent patients: a retrospective study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2006;30:265–72. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Manhapra A, Rosenheck R, Fiellin DA. Opioid substitution treatment is linked to reduced risk of death in opioid use disorder. BMJ 2017;357:j1947. 10.1136/bmj.j1947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Apelt S, Scherbaum N, Soyka M. Induction and switch to buprenorphine-naloxone in opioid dependence treatment: predictive value of the first four weeks. Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 2014;16:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dayal P, Balhara YPS. A naturalistic study of predictors of retention in treatment among emerging adults entering first buprenorphine maintenance treatment for opioid use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017;80:1–5. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cox J, Allard R, Maurais E, et al. . Predictors of methadone program non-retention for opioid analgesic dependent patients. J Subst Abuse Treat 2013;44:52–60. 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nosyk B, MacNab YC, Sun H, et al. . Proportional hazards frailty models for recurrent methadone maintenance treatment. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:783–92. 10.1093/aje/kwp186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee CS, Liebschutz JM, Anderson BJ, et al. . Hospitalized opioid-dependent patients: exploring predictors of buprenorphine treatment entry and retention after discharge. Am J Addict 2017;26:667–72. 10.1111/ajad.12533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Integrating buprenorphine maintenance therapy into federally qualified health centers: real-world substance abuse treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131:127–35. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruger JP, Chawarski M, Mazlan M, et al. . Cost-Effectiveness of buprenorphine and naltrexone treatments for heroin dependence in Malaysia. PLoS One 2012;7:e50673. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lions C, Carrieri MP, Michel L, et al. . Predictors of non-prescribed opioid use after one year of methadone treatment: an attributable-risk approach (ANRS-Methaville trial). Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;135:1–8. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Degenhardt L, Conroy E, Day C, et al. . The impact of a reduction in drug supply on demand for and compliance with treatment for drug dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;79:129–35. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gryczynski J, Mitchell SG, Jaffe JH, et al. . Leaving buprenorphine treatment: patients' reasons for cessation of care. J Subst Abuse Treat 2014;46:356–61. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bao Y-P, Liu Z-M, Epstein DH, et al. . A meta-analysis of retention in methadone maintenance by dose and dosing strategy. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2009;35:28–33. 10.1080/00952990802342899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Janjua NZ, Islam N, Kuo M, et al. . Identifying injection drug use and estimating population size of people who inject drugs using healthcare administrative datasets. Int J Drug Policy 2018;55:31–9. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Glymour MM, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Robins JM. Credible Mendelian randomization studies: approaches for evaluating the instrumental variable assumptions. Am J Epidemiol 2012;175:332–9. 10.1093/aje/kwr323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ding P, VanderWeele TJ, Robins JM. Instrumental variables as bias amplifiers with general outcome and confounding. Biometrika 2017;104:291–302. 10.1093/biomet/asx009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hernán MA, Robins JM. Instruments for causal inference: an epidemiologist's dream? Epidemiology 2006;17:360–72. 10.1097/01.ede.0000222409.00878.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hernan MA, Robins JM. Causal inference. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hernán MA, Robins JM. Per-Protocol analyses of pragmatic trials. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1391–8. 10.1056/NEJMsm1605385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Murray EJ, Hernán MA. Improved adherence adjustment in the coronary drug project. Trials 2018;19:158. 10.1186/s13063-018-2519-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Naimi AI, Cole SR, Kennedy EH. An introduction to G methods. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:756–62. 10.1093/ije/dyw323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Picciotto S, Neophytou AM. G-estimation of structural nested models: recent applications in two subfields of epidemiology. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2016;3:242–51. 10.1007/s40471-016-0081-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hernán MA, Cole SR, Margolick J, et al. . Structural accelerated failure time models for survival analysis in studies with time-varying treatments. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14:477–91. 10.1002/pds.1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vansteelandt S, Sjolander A. Revisiting g-estimation of the effect of a time-varying exposure subject to time-varying confounding. Epidemiol Method 2016;5:37–56. 10.1515/em-2015-0005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.VanderWeele TJ. Principles of confounder selection. Eur J Epidemiol 2019;34:211–9. 10.1007/s10654-019-00494-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morgan JR, Schackman BR, Leff JA, et al. . Injectable naltrexone, oral naltrexone, and buprenorphine utilization and discontinuation among individuals treated for opioid use disorder in a United States commercially insured population. J Subst Abuse Treat 2018;85:90–6. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Australian Government Department of Health Clinical guidelines and procedures for the use of methadone in the maintenance treatment of opioid dependence, 2003. Available: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/drugtreat-pubs-meth-toc~drugtreat-pubs-meth-s3~drugtreat-pubs-meth-s3-3.5

- 88.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:268–74. 10.7326/M16-2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Government of British Columbia Alternative payments program. Available: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/physician-compensation/alternative-payments-program

- 90.Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural sciences and engineering Research Council of Canada, social sciences and humanities Research Council of Canada . Ethical conduct for research involving humans. Tri-council policy statement, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 91.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:344–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.World Health Organization WHO model Lists of essential medicines, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. . Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2017;357:j1550. 10.1136/bmj.j1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-036102supp001.pdf (91.1KB, pdf)