Abstract

Palliative care is central to the role of all clinical doctors. There is variability in the amount and type of teaching about palliative care at undergraduate level. Time allocated for such teaching within the undergraduate medical curricula remains scarce. Given this, the effectiveness of palliative care teaching needs to be known.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of palliative care teaching for undergraduate medical students.

Design

A systematic review was prepared according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidance. Screening, data extraction and quality assessment (mixed methods and Cochrane risk of bias tool) were performed in duplicate.

Data sources

Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov, Cochrane and grey literature in August 2019. Studies evaluating palliative care teaching interventions with medical students were included.

Results

1446 titles/abstracts and 122 full-text articles were screened. 19 studies were included with 3253 participants. 17 of the varied methods palliative care teaching interventions improved knowledge outcomes. The effect of teaching on clinical practice and patient outcomes was not evaluated in any study.

Conclusions

The majority of palliative care teaching interventions reviewed improved knowledge of medical students. The studies did not show one type of teaching method to be better than others, and thus no ‘best way’ to provide teaching about palliative care was identified. High quality, comparative research is needed to further understand effectiveness of palliative care teaching on patient care/clinical practice/outcomes in the short-term and longer-term.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018115257.

Keywords: adult palliative care, education & training (see medical education & training), general medicine (see internal medicine), medical education & training

Strengths and limitations of the study.

This was a rigorously conducted systematic review, including ‘grey’ literature, which evaluated the quality of included studies.

Studies using objective measures of assessment were included; with studies only reporting subjective assessments, self-reports and opinions of participants being excluded. Studies using external ratings as assessment of students were included.

Even using a systematic approach, it remains possible that some studies might have been missed.

Publication bias is possible, as studies yielding negative results are less likely to be published and, although ‘grey’ literature was searched, this may not have fully captured unpublished works.

In view of the variability in interventions and outcomes between included studies, a meta-analysis was not possible.

Background

Palliative care is the holistic care of people with advanced, incurable illnesses, and their families.1 The spectrum of patients receiving palliative care is wide reaching, and ranges from care at the point of incurable illness diagnosis, to the care of dying patients.1 Palliative care is interdisciplinary in nature and involves: symptom control; information sharing with patients; advance care planning; coordination of interdisciplinary input; and care for the families of patients.2 The literature informs us these are the key areas which are deemed important to patients when diagnosed with an advanced and incurable illness.

Medical students and doctors require the appropriate knowledge, skills and attitudes to care for patients who have an advanced and incurable illness. For example, in the UK, it is estimated in their first year of working, newly qualified Foundation Year 1 (FY1) doctors will care for approximately 40 dying patients, and a further 120 patients who are in the last months of life.3 The ability to care for, and communicate appropriately with these patients and their families is an essential skill for all doctors.4

Current medical curricula are saturated,5 and competition for teaching time is fierce. There is an increased drive to incorporate palliative care teaching into medical schools,6 in the hope to improve care for patients. Greater integration of palliative care teaching represents the acknowledgement that care of these patients and those who are dying has room for improvement. Furthermore, an ageing, multimorbid population and a growth in the diversity of palliative treatment options also contribute to the surge in recognition of palliative care’s importance.7 8 Given this increased drive to incorporate palliative care teaching, we need to ensure there is an evidence-base around its effectiveness as justification for its inclusion and/or how to best use this time. Despite this, no contemporary examination of palliative care-related teaching methods exists. The efficacy of various methods has not been recently evaluated, and it is therefore difficult to conclude which methods infer the most benefit on medical students.

Aim

The overall aim of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of palliative care teaching on medical students.

Methods

This systematic review was designed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Protocol 2015 guidance,9 and registered with International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, CRD42018115257). It is reported according to PRISMA guidelines.10

Search strategy

A search and associated terms were developed with an information science specialist to determine the best search strategy. Studies of palliative care teaching were searched using the terms ‘palliative care’, ‘medical student’, ‘Education, Medical, Undergraduate’ and ‘teaching’. To increase sensitivity, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free-text terms were used in searches using the electronic databases Embase (Ovid); Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations; PsycINFO (Ovid); Conference Proceedings Citation Index–Science (Web Of Science; Thomson Reuters, New York City, New York); ClinicalTrials.gov (US NIH); ISRCTN registry (BMC); Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Wiley); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Wiley); and Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (Ovid). Searches were also conducted for grey literature using the following online databases: the Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE) (https://www.base-search.net/), OpenGrey (http://www.opengrey.eu/) and Mednar (https://mednar.com/). The Embase search strategy is included as a online supplemental file. Search strategies from all other databases are available on request from the authors. Searches were carried out on 06 August 2019.

bmjopen-2019-036458supp001.pdf (35KB, pdf)

Reference lists of relevant articles (included studies and reviews) were hand searched.11 Authors’ personal files were also searched to make sure that all relevant material has been captured. Finally, we circulated a bibliography of the included articles to the systematic review team, as well as to scholarship palliative care clinicians’ experts identified by the team, to ensure any relevant literature was not missed.

Eligibility criteria

Studies evaluating a palliative care teaching intervention directed towards medical students were included (table 1). Where there were mixed study populations and data, studies were only included if data on medical students could be individually extrapolated. To be included, studies needed to demonstrate an objective measure of knowledge or skills (eg, a test score); studies with only self-opinion/self-perspective, reflective essays and qualitative outcomes were excluded.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for inclusion or exclusion based on key study criteria

| Study design | |

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Randomised studies, non-randomised studies, cluster studies, before and after studies, cohort studies, observational studies, case-control studies and narrative research studies. | Case studies. Opinion pieces (commentaries, letters, editorials). |

| Participants | |

| Studies in medical students. There were no exclusions based on age or course type. | |

| Interventions | |

| Studies of any type of education were considered for inclusion. This included but was not limited to Online (lectures, videos, quiz), workshops, lectures, small group teaching, bedside teaching, reflection, reflective essays. | |

| Comparators | |

| Any comparators were considered for inclusion. Likely to be no, different or less education. | |

| Outcomes | |

| Any outcome measure assessing the effectiveness of palliative care learning and teaching. These might relate to competence/skills, and/or knowledge, and include but not limited to, exam scores. | Studies with only student’s self-opinion/self-perspective, reflective essays and qualitative outcomes were excluded as the primary interest was objective measures of effects of palliative care teaching interventions. |

| Timing | |

| No restrictions on length of follow-up after the teaching was delivered to medical students. | |

| Setting | |

| No restrictions by country or education setting (providing it was to medical students). | |

| Date | |

| No restrictions by date. | |

| Language | |

| No language restrictions for searching studies. Non-English language papers were included in the review and every attempt was made to translate all included foreign language papers. However, if translation was not possible, this was recorded. | |

| Publication status | |

| Published as well as unpublished work was searched for and considered for inclusion. If only an abstract was available, the authors were contacted to attain further information from their study. | |

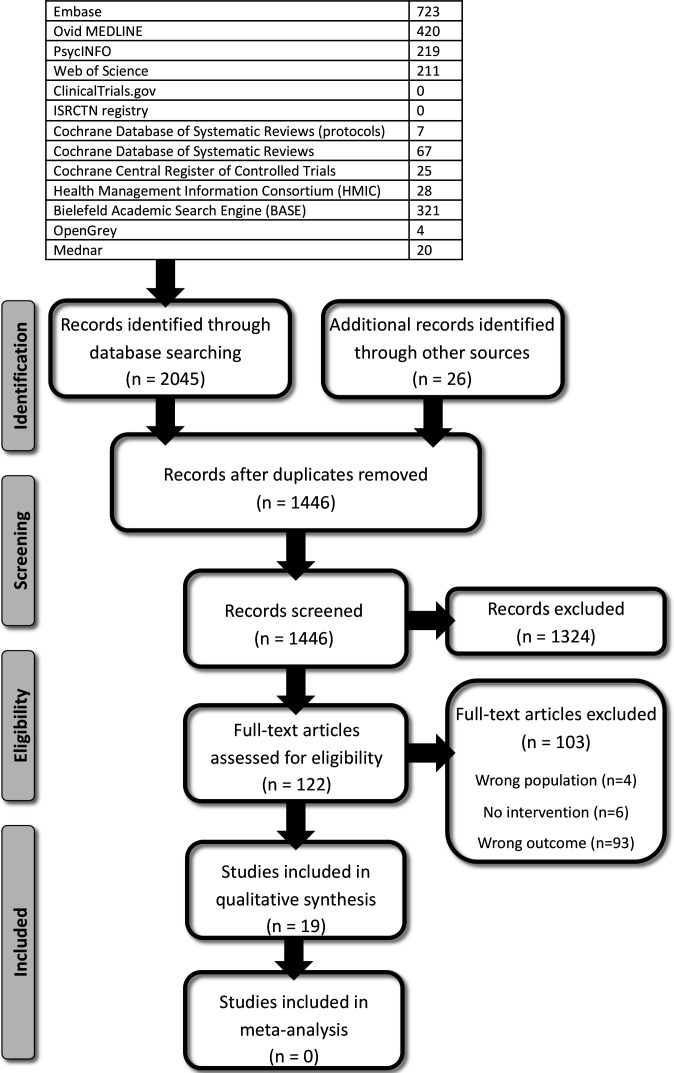

Titles/abstracts and full-text papers were independently screened against pre-defined eligibility criteria (table 1) by two reviewers (JB and either AD/MB). Disagreement at all stages was resolved by consensus and/or with a third reviewer (either JB or AD/MB). The results of the searches were shown in a PRISMA flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram.

Data extraction

Data were extracted in duplicate (JB and either AD/MB) for the aim, study setting, design, population included, educational intervention and comparator, assessment method used, outcomes, Kirkpatrick Model level,12 study quality, strengths/limitations and ideas for further research (determined by the study authors and reviewers) onto pre-prepared templates.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of each study was independently assessed by at least two reviewers (JB and either AD/MB). Disagreement was resolved by consensus and/or with a third reviewer (either AD or MB). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) was used if the study was mixed methods13 and Cochrane risk of bias tool was used if a study was quantitative.14

The MMAT is a critical appraisal tool developed to evaluate studies using both qualitative and quantitative data.15 MMAT was used in line with its original purpose, to appraise mixed methods research and to evaluate non-randomised quantitative research. Two screening questions are asked, before progression to more detailed analysis:

Are there clear research questions?

Do the collected data allow to address the research questions?

In this review, the answer to both of these questions had to be ‘yes’ for a study to qualify for inclusion. Evaluation using MMAT subsequently focussed most heavily on appraising methodology, assessing five core criteria for each study type. These core criteria can be reviewed in detail, with additional usage guidance, using the 2018 iteration of the MMAT tool.15 To aid interpretation of what was meant by the core quality criteria, the research team referred to this expanded guidance. A summary of the core criteria for mixed methods research and non-randomised quantitative research, the ways in which the MMAT was used in this work, are listed in table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) core quality criteria for mixed methods and non-randomised quantitative research, adapted from Hong et al15

| Study design | Core quality criteria |

| Mixed methods research |

|

| Non-randomised quantitative research |

|

NB: when criteria 5 of mixed methods research references adhering to the quality criteria of each method involved, it references the quality criteria listed in other sections of the MMAT of the individual methods used, for example, the quality criteria for non-randomised quantitative research. This research followed this guidance.

The Cochrane risk of bias tool was used to appraise any randomised trial studies; as it is the gold-standard for such evaluation.14 The Cochrane risk of bias tool has more stringent appraisal criteria, focussing on evaluating the presence of several types of bias: selection bias; performance bias; detection bias; attrition bias; reporting bias; and other bias. The plausible bias within studies deemed ‘low risk’ were unlikely to seriously alter results and therefore be accepted. Studies at medium risk of bias imply ‘some confidence that the results represent true effect’. Despite medium risk, the issues with these studies are ‘not sufficient to invalidate results’; these studies were therefore included in our review unproblematically.16 Studies rated as high risk of bias should be considered sceptically.

Data analysis and synthesis

Due to the heterogeneity of results, a narrative data synthesis was performed. A team of researchers were involved in the synthesis and development of themes, and analysis of potential biasses and quality. Four stages took part with all members of the research team: (1) development of a theoretical model, (2) preliminary synthesis, (3) exploration of relationships in the data and (4) assessing the robustness of the final synthesis.17

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the planning or design of this systematic review.

Results

The search identified 1446 titles and abstracts for initial screening against the study’s eligibility criteria. Following this, 122 full-text articles were screened in detail for eligibility. Nineteen studies were included (figure 1). The total number of participants in the 19 studies was 3595, data were gained and used from 3253 participants, with long-term follow-up data (up to 1 year) in 274 participants (from three studies). Publication dates were between 2002 and 2018. The number of participants in the included studies ranged from 40 to 670; with a mean of 171.2 participants per study (table 3).

Table 3.

Data extraction table

| Author year country | Aim | Study design | Population | Palliative care teaching intervention | Comparator | Assessment method | Outcomes | Kirkpatrick model level | Study quality | Strengths and limitations | Further research |

| Auret 2008 Australia35 |

Identify if a structured clinical instruction module improves students self-rated confidence | Pre and post test design. | 91 sixth year medical students (91/106 students: response rate=86%) Follow-up questionnaire at end of academic year: 30/109 students (response rate=28%) |

2-hour Structured Clinical Instruction Module - nine 15 min stations. Four groups of 30 to 35 students (in groups of four). Taught by one palliative care consultant + team of nurses/doctors/ pharmacist |

Acted as own comparator, pre and post test | Questionnaire – 6-point Likert scale. Pre workshop, immediately post workshop + follow up at end of academic year | Improved knowledge and skill post workshop. Poor rate of completion of follow-up, but sustained improvement. | 2a | Assessed using Cochrane risk of bias tool, medium risk of bias. Risk of attrition bias- 86% initial completion rate dropped to 28% completion at end of academic year. Reasons not fully explored. | Strengths - required less facilitators than some other interventions, ‘practical feel’. Limitations - no statistical reporting, poor response to longer-term follow-up minimising evaluation of knowledge retention. | To formally test knowledge and skill competence following workshop |

| Brand et al 2012 Australia19 |

Evaluate students’ knowledge, attitudes and experience of a palliative care education programme in a graduate entry medical setting | Pre and post test design knowledge and self-efficacy in palliative care | 62 second year graduate med students. 40/62 (64.5%) completed both the pre and the post test Taught by four palliative care consultants + four registrars |

8 hours palliative teaching within 100 hours oncology curriculum. 5 week oncology/palliative care block. Lectures, PBL sessions, bedside/clinic tutorials, visit to inpatient unit, self-directed reading. | Acted as own comparator, pre test and post test | Multiple choice question knowledge test, two validated attitudinal scales, student feedback survey (Likert scale + open ended questions) | No statistical significance in mean improvement in knowledge. Subset statistical improvement in symptom management (p=0.001). improvements in attitudes towards communication, symptom management and MDT care | 2b | Assessed using mixed methods tool- passed all components. | Strengths - mixed methods study. Limitations - possible selection bias – only 64.5% completed pre and post tests and 42% response rate to student evaluation questionnaire, multiple choice questions weren’t independently validated. |

No |

| Brownfield 2009 USA30 |

Examine the feasibility of a 1-week palliative care course incorporated into the medicine clerkship; knowledge and attitudinal changes in students who had completed the course. | Pre and post test design | 84 third year medical students. 53/84 (63%) students completed both pre and post tests |

1-week palliative care curriculum during a 1-year period. Included in-patient and out-patient care, MDT rounds, reflection and didactic teaching around core clinical topics. |

Acted as own comparator, pre test and post test | Survey of attitudes towards palliative care and pre and post course measurements of knowledge. | Statistically significant improvement in knowledge scores (pre-course mean scores 145/230 and 175/230 post-intervention (p<0.01). Improved attitudes. |

2b | Assessed using mixed methods tool- passed all components. | Strengths - mixed methods study. Limitations - 63% response rate even to knowledge tests response bias. |

No |

| Chang et al 2009 China (including Taiwan)31 |

Evaluate the effect of a multimodal teaching programme on preclinical medical students’ knowledge of palliative care and their beliefs relating to ethical decision-making. | Pre and post test design | 118 third year medical students ‘pre-clinical’ in Taiwan as medicine is a 6-year degree. Voluntary participation. Taught by palliative care doctors, clinical social workers, chaplain, nurse practitioner/nurse lead for palliative care. |

1 week, end of life care curriculum developed. Three learning modules. Included bedside teaching, lecture series and small group discussion. | Acted as own comparator, pre test and post test | Assessed knowledge + beliefs regarding decision-making. Instrument constructed based on literature review and national guidance. Validated for use by content expert and tested for reliability- items not meeting reliability statistical cut-off excluded. |

Improved knowledge following intervention by 14.7% (p<0.001). Clinical management knowledge improved the most. Some improvement in beliefs regarding decision-making but not universal. |

2b | Assessed using Cochrane risk of bias tool Medium risk of bias. Selection bias likely to be present students were volunteers, risking self-selection bias. 100% response rate no attrition bias. |

Strengths - validated test tool. Limitations - only 18/32 knowledge items reliable enough for inclusion. Knowledge questions were true/false/not sure. Follow-up immediately after intervention, not testing long-term retention of knowledge. |

None discussed |

| Day et al 2015 USA26 |

Compare the effect of eLearning versus small-group learning | Quasi-randomised controlled trial of web-based interactive education (eDoctoring) compared with small-group education (Doctoring) | 119 Third year medical students. eDoctoring (n=48) or small-group Doctoring (n=71). | Interactive e-learning: eDoctoring on palliative care clinical content over 2 months. No faculty input while taking the course. Small group teaching for 3 hours on communication skills. Year-long course. |

26 Small group sessions on palliative/end of life care. Small group teaching for 3 hours on communication skills. Year-long course (same as intervention arm). |

Pre-test and post-test questionnaires. 27 self-efficacy questions rating confidence. six single best answer knowledge questions relating to curriculum covered by modules completed in eDoctoring. |

Both groups- knowledge questions improved post-test, non-statistical trend present favouring the eDoctoring students. in self-efficacy ratings in both intervention and control, with no differences in improved between the groups. |

2b | Assessed using Cochrane risk of bias tool. Medium risk of bias. Quasi-randomised, low selection bias. Attrition bias possible- more dropouts in Doctoring arm (results excluded from analysis) - reasons not explored. |

Strengths - quasi-randomised Limitations - no long-term measures in knowledge retention. Randomisation did not include technology fluency or viewpoints. |

No |

| Dorner et al 2014 Germany28 |

Explore the feasibility of peer teaching for communication skills training. | Pre and post test study | 37/49 (76%) medical students in the fourth to sixth of medical school. Voluntary participation open to all medical students. Tutors - fifth and sixth year medical students trained by faculty to deliver teaching. |

90 min peer taught workshop teaching nine core communication skills regarding palliative and end of life care, particularly within the intensive care unit. Case based discussions and role play both used. | Own comparator, pre test and post test | External ‘intensivist’ rated students based on a taped role play they conducted with another student. Qualitative analysis of transcripts to see how students spoke about death. Self-rated skills scores. |

Self-rating scores improved following intervention (p<0.001). Mean expert ratings did not differ from student’s own assessment of performance or skills except in one domain |

2b | Assessed using mixed methods tool- passed all points. | Strengths - peer teaching affordable and easily scalable. Limitations - lacks long-term evaluation |

Further work required regarding student’s ability to use the word ‘death’. |

| Ellman et al 2016 USA29 |

Evaluate 4-year curriculum in palliative care. | Mixed method evaluation | First to fourth year medical students. 95 students in the implementation year | 4-year longitudinal, integrated curriculum. Included workshops, hospice experience, modules, communication skills and a year four palliative care observed structured clinical examination (OSCE) station. 2 hours in first year; 4 hours in second year; 15 to 23 hours in third year; 4 hours in fourth year. |

Comparator only for graduating student surveys- compared with national Association of American Medical Colleges questionnaire of US medical schools regarding confidence with palliative care. |

Competency in a palliative care OSCE station at the end of the curriculum. Analysis of student written reflections. Graduating student surveys regarding how prepared students felt following course. |

In implementation year, average score 74% in OSCE palliative care station- lower than average score for other OSCE stations (84%) but felt to be ‘acceptable’. Students undertaking 4-year curriculum felt more prepared in palliative care compared with other US medical schools. | 2b | Assessed using mixed methods tool - passed all points. | Strengths - mixed-methods study, curriculum is well integrated and longitudinal. Limitations - no long-term follow-up data, OSCE station on palliative care scored lower still than OSCE stations on other subjects |

In order to evaluate longer-term effect of curriculum, team are planning a survey of former students now in postgraduate training. |

| Gerlach et al 2015 Germany20 |

Evaluate the effects of the Mainz undergraduate palliative care education on students’ self-confidence regarding important domains in palliative care. | Prospective questionnaire-based cohort study with a pre–post design. Knowledge test only at end of module. | 329 fifth year medical students. All students took knowledge test. 156 (47%) students completed matched surveys at both points of measurement Facilitators: physicians, palliative care nurses, bereaved family members. |

Mandatory palliative care module over one term. 7×90 min sessions. Included pain lecture hospice home care through use of videoed live interview with bereaved family member. Small group discussion. |

Knowledge scores: historic test scores from before the intervention within Mainz examined same test so comparison is likely acceptable. Self-confidence scores, comparison with cohort from 2011 in Mainz who did not receive module. |

Multiple choice electronic knowledge exam after module 21 item, single best choice answer. Pre and post testing of students’ self-confidence. |

All passed knowledge exam, average scores >90%. Compared with historic cohort: increased in correct answers for pain (40%), symptom control (69%), and psychosocial knowledge (33%). Self-reported confidence improved. |

2b | Assessed using Cochrane risk of bias tool. Medium risk of bias. Attrition bias: 47% of surveys matched for pre and post test results, so data lost. Reasons are clear - incomplete form completion, effect of this is unclear. |

Strengths - Intervention acceptable, enjoyed interdisciplinary input. Limitations - only 47% of surveys pre and post intervention matched and used (due to local policy), unknown if increases in knowledge and self-confidence are linked. |

Whether or not the course provided only an instant or a long-term effect - research underway. Further research needed regarding any effect on patient outcomes. |

| Goldberg et al 2011 USA18 |

To assess the effect of a required clinical rotation in palliative medicine | Historical control trial | 117 fourth year medical students (month prior to graduation) Taught by two interdisciplinary teams, each with an: attending physician, fellow in palliative medicine/geriatrics/oncology, a nurse practitioner, and a social worker staff (clinical team portion) + social worker, chaplain, & massage therapist |

n=59 (51% of students from class of 2008) Addition of a required 1 week clinical rotation in palliative medicine (integrated in 12 week IM-Geriatrics clerkship) – multiple venues, time spent with consult team + formal didactic lectures on palliative care issues | n=58 (55% of students from class of 2007)=historical control group (received didactics but no clinical rotation in palliative medicine) | Survey: self-rated skills performance and interest, student educational experience, 30-question MCQ exam 2008 cohort also had two open-ended questions Components of Association of American Medical Colleges annual graduate questionnaire |

No statistical difference in mean scores for knowledge questions Higher skills self-ratings in 2008 cohort Association of American Medical Colleges questionnaire: 2008 cohort more experience in palliative care |

2b | Assessed using mixed methods tool - passed all points. | Strengths - mixed methods study, utilised historical control group Limitations - diversity of exposure with clinical rotations, not controllable |

Further research into qualitative findings - how might reported skills be applied Exploring different venues of palliative care (outpatient) for clinical rotations |

| Green 2010 USA25 |

Pilot study evaluating the effectiveness of a computer-based decision aid for teaching medical students about advance care planning. | Prospective, randomised controlled design | 133 second year medical students. 121/133 (91%) of students agreed to have their data used in study - 60 in the Decision Aid Group and 61 in the Standard Group. |

Computer-based decision aid for student use to help patients with advanced care planning (to help patient complete advance directive). Multimedia tool, uses educational material and exercises to help patient clarify values and priorities, help students explain end of life conditions and treatments and then helps synthesise this into an advance directive. |

Prior to intervention all students received instruction in advanced care planning lectures, reading material, small group discussion. | Knowledge assessed using a 17-item true/false and MCQ. Self-rated satisfaction, confidence and perceived knowledge of patient wishes. Patients’ evaluation of student assessed using 12-items addressing students’ communication skills, helpfulness and perceived understanding of their wishes. Patients’ satisfaction assessed by measure of global satisfaction |

High baseline knowledge for advance care planning. Students in decision aid group more improved (84% to 88%, p<0.01) Student confidence increased following interventions in both groups but more in decision aid group. Student satisfaction higher in decision aid group. Patients significantly more satisfied with student performance and global impression in decision aid group. |

3 | Assessed using Cochrane risk of bias tool. High risk of bias. No discussion of how students were randomised so unclear if selection bias is present. patient bias - students were responsible for recruiting patients and these were eligible to be family/friends- patient rating scales may well be biassed. |

Strengths - tool easy to roll out and applicable within other institutions. High levels of student and patient satisfaction. Limitations - pilot study so not powered. Selection of patients determined by students. No full data regarding student interactions with patients, time spent. Confounding factors within this that could have impacted results. Measures used within the study not validated. |

National study comparing this computer programme with current approaches to advance care planning. |

| Jackson 2002 USA34 |

Evaluate a palliative medicine curriculum developed for medical students in the required third-year clerkship in family medicine at the University of Tennessee. | Pre and post test design with the post-test assessment 7 weeks later. | 69 third year medical students on their family medicine clerkship | Four-hour curriculum. Prior to session students were sent reading concerning palliative care. During session- discussion, role play, information giving via PowerPoint and lecture. |

Acted as own comparator, pre test and post test | 20 item pre-test and post-test for palliative care knowledge. One item confidence question regarding palliative care clinical skills. |

Significant knowledge gain post-test (37% pre-test to 55% post-test); (p<0.0001). Small but statistically significant increase in self-reported confidence (p=0.031). |

2b | Assessed using Cochrane risk of bias tool. No bias noted in any domains. Low risk of bias. |

Strengths -Popular with students on course evaluation. Limitations - other palliative care education at institution. |

long-term retention of knowledge and the development of instruments to measure the translation of a theoretical knowledge base into actual clinical skill sets. |

| Paneduro et al 2014 Canada33 |

Develop and evaluate a pain management and palliative care seminar for medical students during surgical clerkship | Pre and post test design with the post-test assessment at 1 year | 292 third and fourth year medical students in surgical clerkship 95% (n=277) completed post test immediately following the seminar and 31% (n=90) completed the follow-up test via email. |

4-hour seminar on pain management and palliative care Taught by faculty from pain medicine, surgery and palliative care |

Acted as own comparator, pre test and post test | 10-item knowledge test Comments on seminar |

Significant knowledge improved; maintained at 1 year. mean pre-test, post-test and 1 year follow-up test scores were 51%, 75% and 73%, respectively. No difference between third and fourth year students |

2b | Assessed using mixed methods tool - passed all points. | Strength - relatively short items to respond to in order to facilitate participant, collaboratively designed seminar Limitations - high attrition rate at 1 year. Hard to control for seminar impact specifically, at long-term follow-up |

Modify seminar to better target attitudes/beliefs |

| Porter-Williamson et al 2004 USA23 |

Assess impact of a hospice curriculum for medical students, in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes | Pre and post test study | 127 third year medical students | 32 hours, 4 day curriculum | Acted as own comparator, pre test and post test | 26-item self-assessment of competency, a 20-item self-report of concerns, a 50-item MCQ knowledge test and qualitative assessment of course curriculum | 23% improved knowledge 56% improved competence 29% improved for concerns (all p<0.0001). No changes for attitudes (p=0.35) (already had appropriate attitudes) |

2b | Assessed using mixed methods tool- passed all points. | Strength - multiple measures of curricular evaluation, curriculum could be applied at other universities Limitations - no long-term follow-up |

Link specific clinical encounters with clinical knowledge changes, for explanation; longitudinal re-examining |

| Schulz-Quach et al 2018 Germany22 |

Evaluate an eLearning course ‘Palliative Care Basics’ in terms of student acceptance, exam performance and competence | Cross-sectional study | 670 undergraduate medical students (three cohorts). 569 (96%) used eLearning as preparation for the exam; 23 did not. | eLearning course (five teachings domains over 10 teaching units). Virtual patient contact, didactic teaching, e-lectures, patient case vignettes | Students who did not access the eLearning course. 23 students | Questionnaire of self-assessment Course evaluation, with ratings and free response section 20-item MCQ exam |

Knowledge improved (p=0.02). High approval of eLearning tool – easy to approach topics, increased interest | 2b | Assessed using mixed methods tool- passed all points. | Strength - mixed methods Limitations - no baseline measurements, very small comparator group |

Further assessment of eLearning tools in blended curriculum |

| Tai et al 2014 Australia21 |

Assess whether a 1-week palliative care placement improves student performance and knowledge. Explore student views on palliative care rotation, particular for building confidence | Consecutive cohort retrospective analysis, pre and post test mixed methodology | 84 fifth year medical students (who enrolled in palliative care placement). 72 (86%) completing both pre and post course multiple-choice questions |

1 week palliative care placement Combination of didactic and interactive tutorials with experiential attachment such as ward rounds |

Acted as own comparator, pre test and post test/course | Knowledge-based questions (16 MCQs) Post-course satisfaction ratings (10-closed item questions + 2 open-ended questions) |

Improved knowledge: average 58% to 74% (p<0.001). Most reported value of course and wanted more palliative care education |

2b | Assessed using mixed methods tool- passed all points. | Strength - mixed methods. Limitations - measures not validated; reduced sample size due to exclusion of students who did not complete both parts of study |

Assess value of different length palliative care placements (1 week might not be enough) |

| Tan et al 2013 Canada36 |

Determine whether virtual patient case in palliative care could offer students acceptable alternative to real-life experiences | Mixed methods pre and post survey | 137 third year medical students 95% (130/137) consented to have their results analysed. knowledge score assessed in 127 |

Virtual patient clinical case, mandatory exercise in family medicine rotation Average time spent with virtual patient case=0.93 hours, SD=0.65 |

Acted as own comparator, pre test and post test | Knowledge test and level-of-preparedness survey (self-assessment of clinical skills), plus student feedback on virtual patient case/usage and general feedback | Knowledge scores increased (48%–63%: p<0.001) virtual patient case was realistic (91%), and educational (86%) Students spending >20 min on case reported more engagement |

2b | Assessed using mixed methods tool- passed all points. | Strength - mixed methods approach for evaluation Limitations - hard to correlate time spent on case with outcomes, limited info about students’ experiences with real patients |

Expanding knowledge component of study to better understand specific changes in knowledge |

| Tsai et al 2008 China32 |

Assess the impact of a 4-hour multimodule curriculum on knowledge and attitudes of end of life care | Prospective cross-sectional pre and post test survey | 259 fifth year medical students | 4-hour course included: 1 hour lecture by specialist, 1 hour patient visit at unit, 1 hour literature reading, 1 hour discussion | Acted as own comparator, pre test and post test | Questions on knowledge, demographics and ethical beliefs | Knowledge improved (55% to 70%) (p<0.0001). Principles of palliative care scores improved (58% to 73%). Clinical management improved (59% to 68%) |

2b | Cochrane risk of bias tool - low risk of bias, no bias evident in any domains. | Strength - easy to implement curriculum. correlation analysis across items Limitations - hard to control for confounding variables like maturation effect |

Further assessment of medical training (residency and clinical practice) – follow-up studies Longitudinal study to better understand changes over time |

| Tse 2017 USA27 |

Explore the application of online learning tool with hospice experience | Randomised prospective pre and post study | 152 second year medical students completed the survey (response rate 51%) 56% (n=85) completed the online module |

Addition of 30 min online module to hospice experience. Taught by hospice care physician or nurse) in hospice setting |

Randomised to receive module prior to hospice experience (YES module) versus after experience (NO module) | 23-item electronic survey: 10 attitude-assessing statements from FATCOD, 8 multiple choice knowledge questions | Higher scores on knowledge questions for students completing the online module (p=0.006). No statistical difference in attitudes |

2b | Assessed using Cochrane risk of bias tool, medium risk of bias. Self-selection bias as voluntary participation, could suggest already motivated regarding palliative care. Randomisation not described | Strengths - mixed methods study, focussed on assessing blended learning experiences Limitations - single site study, survey was relatively few items |

Expanding scope of study for more institutions (generalisability) More survey items → more comprehensive assessment |

| von Gunten et al 2012 USA24 |

Assess impact, retention and magnitude of effect of a required didactic and experiential palliative care curriculum | Prospective pre and post study | 487 third year medical students | Specified palliative care curriculum designed for 1 day/week for 4 weeks (during the ambulatory block of the 12 week IM clerkship) Taught by IM faculty. participation was compulsory |

Self-comparator over time (pre test and post test). knowledge compared with national cross-sectional study comparing residents at progressive training levels |

36-item knowledge test, self-assessment of competency, & self-assessment of attitudes + written surveys | Knowledge: improved 52% to 67% (national residents, average score 62%). 56% improved confidence (higher than resident national averages). 29% decrease in concern. (All p<0.001). All maintained at 1 year. |

2b | Assessed using mixed methods tool- passed all points. | Strength - mixed methods, assess various levels of effect, national comparison Limitations - evaluation instruments designed for specific learning objectives of course. Documentation of long-term follow-up unclear |

None outlined by study |

IM, Internal Medicine; MDT, Multidisciplinary Team Meeting; PBL, Problem Based Learning.

Quality appraisal

The quality of mixed methods studies were assessed using the MMAT (n=11),13 and purely quantitative studies using a trial type of methodology were assessed using Cochrane risk of bias tool (n=8).14

Overall the 11 mixed method studies included met all required components of quality using the MMAT (table 3).

The Cochrane risk of bias tool was used to appraise any randomised trial studies. Included studies showed a range of bias; one was high risk of bias, five were medium risk of bias and two were low risk of bias (table 3).

Context of included studies

Demographics

The selected studies took part in many countries; nine USA, three Australia, three Germany, two Canada and two China (including Taiwan).

Study designs

Fourteen of the included studies tested knowledge before and after a teaching intervention, in a pre–post design. The post test was immediately post intervention in all but four studies, with one study conducting its post test at 7 weeks, and the other three at approximately 1 year post intervention. Most of these pre–post designed studies were cohort-type studies; one was randomised and three included a mixed methods design. The other five included studies used a randomised controlled design, quasi-randomised controlled trial, historical control trial and two cross-sectional design studies (table 3).

Types of teaching interventions

The included studies had a wide variety of teaching methods and teaching hours. The main shared descriptor of palliative care teaching interventions in the included studies was the duration. Studies could be largely summarised as ‘small’ scale teaching interventions (interventions with a duration of hours) or as ‘large’ scale teaching interventions (interventions that took place over the course of days). Included studies were categorised into these durations, and durations were decided comparatively by the researchers. In addition to these small and large interventions, a third descriptive category was determined: eLearning interventions. Because the nature of eLearning is often associated with uncertain measures of time (depending on student use outside of learning environment), eLearning interventions were considered to be different than small or large face-to-face teaching interventions. Given the variance in shared descriptors, the decision was made to synthesise results based on the type of intervention: small, large or eLearning.

Different assessment methods

The studies used different assessment methods and some studies used multiple methods of assessment (table 3); this made it difficult to assimilate study outcomes. Most commonly, multiple choice questions (MCQs) were used to test knowledge18–24 or a combination of MCQs and true/false questions.25 The number of items testing knowledge differed between studies. These ranged from 6 single best answer items,26 8 MCQs27 to 50 MCQs.23 Other methods of assessments included an ‘external intensivist’ rating student performance based on a taped role play28 and observed structured clinical examination (OSCE) station assessment.29 Some studies also assessed student attitudes and confidence in a pre–post format.19 21 24 25 27 30 31

Synthesis of results

Smaller teaching interventions

Seven of the included studies evaluated a ‘small’ palliative care teaching intervention; these included a range of interventions of different sizes, from 1.5 to 10.5 hours, with a median of 4 hours.19 20 28 32–35 Six of the seven included studies showed statistically significant improvements in knowledge assessment outcomes (table 3),20 28 32–35 and one of these studies included a 1-year follow-up, with knowledge retention demonstrated.33 Although one study did not show overall improvement in knowledge scores, it did demonstrate statistically significant improvements in symptom management scores in a subset analysis.19

Larger teaching interventions

Seven of the included studies evaluated a ‘large’ palliative care teaching intervention, with interventions ranging from 4 to 5 days, with a median of 5 days (table 3). Six of the seven large scale studies demonstrated statistically significant improvements in knowledge assessment outcomes; although one of these had a poor comparator.29 One study failed to demonstrate an improvement in knowledge from mandatory participation in a clinical palliative care module compared with didactic teaching alone.18 There were critical limitations in the comparator used in the study by Ellman et al.29 Ellman et al developed a new palliative care OSCE to assess student knowledge regarding symptom management, communication and the psychosocial, spiritual and cultural aspects of care. Competency in this OSCE station was deemed adequate by the authors (average score 74%) although the level attained at this station was below that of other OSCE stations; which was on average 84%.29 There was also no pre and post intervention testing, thus it is unclear if this intervention improved knowledge or not.

eLearning teaching interventions

Five studies evaluated the effect of eLearning on knowledge in palliative care, with all these studies demonstrating statistically significant improvements in knowledge scores (table 3). The specific type of eLearning varied, but included: a virtual patient clinical case,36 a computer-based decision aid for advance care planning content,25 a flipped classroom online module coupled with a hospice care experience,27 and an eLearning course.22 The fifth study, an interactive e-learning course, is notable because it reported equivalence in increasing knowledge scores, when compared with small-group teaching sessions.26 Of the eLearning studies included, this is the only one to provide a comparator to the eLearning resource. However, the study still considered the eLearning intervention to be ‘successful,’ as it was determined to be less faculty intensive to run but imparted the same degree of knowledge as ‘traditional’ teaching.26 Overall, all eLearning interventions offered flexibility for students.

Summary

Overall, the majority (n=17) of the included studies demonstrated an improvement in knowledge. Small amounts of specific teaching improved knowledge in six out of seven studies. Similarly, large amounts of teaching improved knowledge in six out of seven studies. All eLearning interventions improved assessment outcomes in tests of knowledge. No included study directly compared small and large teaching interventions and, as study outcomes were heterogenous, it was not possible to evaluate whether small or large interventions were ‘better.’

Discussion

This systematic review presents a contemporary overview of the literature regarding the effectiveness of palliative care teaching to medical students. All types of teaching intervention (small-scale and large-scale teaching, clinical and eLearning) improved knowledge scores for medical students. No method appeared to be superior in improving knowledge. Few studies explored knowledge retention, skills or attitudes. No studies explored the impact of teaching on clinical care for patients. Significant heterogeneity of teaching approaches continues to exist, and is increasing, as new teaching methods (such as eLearning) develop and grow in popularity. Further contributing to the heterogeneity was the inconsistency of overall teaching approaches and methods of assessment in all included studies. This leads to the hypothesis that, regardless of the style of teaching, improvement in palliative care knowledge scores is possible following teaching. Study designs, too, differed significantly, with no consistent approach to long-term follow-up. In view of the multifaceted heterogeneity evident in both study design and outcomes, the data gathered systematically were synthesised narratively.17

Outcomes and constructive alignment considerations

Examining the intervention efficacy with an educational theory lens was the logical first step in performing a narrative synthesis of included articles in this particular review. One of the first theories to consider in any study measuring knowledge via assessment is Biggs’ theory of constructive alignment.37 38 Constructive alignment argues that there needs to be alignment of learning outcomes, teaching methods and assessment measures, otherwise, true learning may not occur. For example, if an educator presents learning outcomes to students related to palliative care, but then teaches a session on dermatology, and gives an assessment with questions concerning cardiology, you would expect students to not pass their assessment, and conclude learning did not occur. However, in this admittedly bizarre example, learning might have occurred; it just may have been related to palliative care, or most likely dermatology. Yet, because these educational components are not constructively aligned, it would be impossible to actually comment on learning. This same reasoning can be applied to the studies included in this review. Many studies determined learning occurred, as exemplified by improvement in knowledge scores. However, one issue when conducting this review was the inability to know with any certainty how related teaching and assessment were to one another. It was not made clear by the analysed studies how constructively aligned their assessment was to the palliative care teaching delivered. It was clear that some short interventions were geared to improve a specific aspect of palliative care (eg, advanced care planning),25 but most larger interventions (where details were published and we could discern more exact content of the teaching), covered a range of topics in the palliative care curriculum. Poor detail regarding the content of assessment, and limited assessment regimens, makes it seem likely only some of these topics were formally assessed.

Failure to explicitly acknowledge constructive alignment within any of the included studies makes it difficult to accurately assess the efficacy of any (especially the large) teaching interventions. Reproducibility of the value of the interventions will likely largely depend on specific variables relating to constructive alignment. Utilisation of constructive alignment in teaching intervention design and assessment may have been an influencing factor as to whether an intervention improved knowledge scores. However, without discussion of this in any of the studies, it is not possible to know whether constructively aligned learning outcomes, teaching and assessment are important to effective palliative care teaching.

Impact of teaching interventions

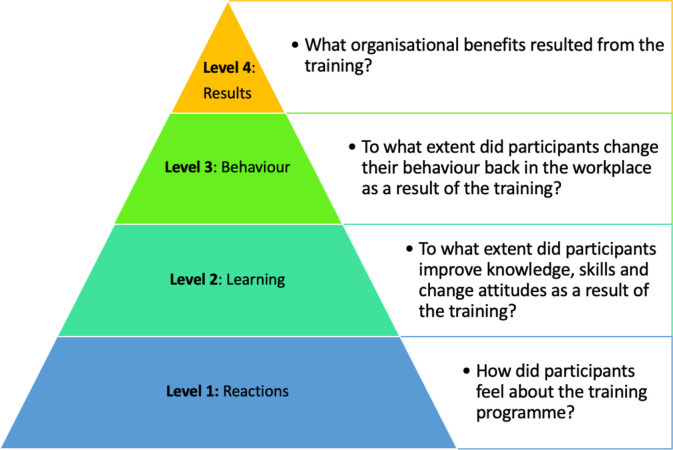

Kirkpatrick’s Four-Level Training Evaluation Model is used to evaluate the results of educational programmes, which are divided into four levels (figure 2).12 This model was used to evaluate the impact of interventions in the included studies.

Figure 2.

Kirkpatrick’s four-level training evaluation model. Reproduced from.41

Included studies in this review were mostly at level 2 of Kirkpatrick’s Four-Level Training Evaluation Model; what students have learnt.12 The only study to assess Behaviour (Level 3) was by Green et al25 where patient satisfaction was evaluated in an advance directive scenario. This introduces the concept that for many of these teaching interventions, their potential efficacy has really only been assessed from a limited viewpoint. Although changes in knowledge and attitude are important, they do not guarantee the educational experience will change behaviour/practice. Measuring the clinical impact of a teaching intervention requires rigorous long-term follow-up, and such follow-up was not performed by any studies within this review. Thus, no conclusions regarding the impact of these palliative care teaching interventions on clinical practice or patient outcomes can be made. This is particularly important as with growing demands and need for quality palliative care in practice, it is important to understand if medical school interventions are actually improving later clinical practice, or long-term decisions of medical students. Studies suggest there are many misconceptions by lay and healthcare professionals of what palliative care is/hospices are, and thus one of the main aims of undergraduate teaching should be to try and dispel these.39 40 This was not explored in any of the studies.

Heterogeneity might indicate wide possibilities for curricular design

While the effect of palliative care teaching on clinical practice could not be elucidated from this review, there was significant information relating to potential knowledge gain and exposure via palliative care teaching interventions. While there was significant heterogeneity in how knowledge was measured in these studies, interesting findings were identified. Both small amounts of specific teaching and larger scale interventions improved knowledge, which may support the argument that institutions should investigate integrating some level of teaching palliative care, even if small, as these can prove beneficial to the knowledge base for students. This is supported by the fact that in these studies, regardless also of the teaching method, improvement in palliative care knowledge scores was possible following instruction. Again, this provides more evidence that while there seems to be no identifiable ‘best practice’ for teaching palliative care in medical education (as no studies compared this or asked this question, and knowledge scores used by different studies was not the same), this means that institutions can adapt from a variety of methods that may work best for their curriculum. eLearning also appeared to improve knowledge scores in studies included in this review. One study demonstrated the potential value of integrated eLearning with existing clinical experiences; a small, online module provided to students prior to a hospice experience demonstrated improved knowledge among these students.27 This study, and the others relating to eLearning, contribute to the possibility that any type of palliative care teaching may be very beneficial, even with the need for more focussed and detailed research.

Strengths and limitations of the systematic review

This is a rigorously conducted systematic review designed using PRISMA Protocol 2015 guidance,9 and reported according to PRISMA guidelines.10 It included ‘grey’ literature and evaluated quality of the studies and impact on clinical practice. However, it is possible some studies might have been missed and publication bias is possible, as if studies were not available then they would not have been included. Different reviewer expertise brought diversity to the team and ensured a multi-angled perspective. The systematic review drew on the international literature studying medical student education about palliative care. As such, it is generalisable and applicable to an international audience.

In view of the variability in interventions and outcomes between included studies a meta-analysis was not possible, and a narrative synthesis was performed. Risk of bias was assessed by two different tools, depending on the study type. The mixed methods tool was used if the study was mixed methods as this tool was not applicable to purely quantitative work.13 Cochrane risk of bias tool was used if a study was purely quantitative.14 The Cochrane risk of bias is designed for randomised controlled trials so some aspects of appraisal, like allocation concealment, often weren't applicable for the included quantitative studies.14

This review primarily used objective measures of assessment and excluded subjective assessments, self-report and opinions of participants. However, studies using self-report of external people were included. External rating is still subjective but is an external outcome measure.

Limitations of included studies

The main limitation of the included studies is that none assessed effect on clinical practice and patient outcomes. Thus, the effect on clinical practice of each teaching intervention is unknown. Only three studies undertook follow-up and collected long-term data; this was on 274 students. Thus, only a small portion of participants are represented in this data. ‘Long-term’ in this sense encompasses follow-up within 1 year. No studies provided follow-up data beyond this point, a limitation of all included studies. None of the included studies compared the impact of small versus large scale interventions, meaning that, although most interventions were effective, it is unknown whether large-scale or small-scale teaching or eLearning interventions are more effective in instilling palliative care knowledge.

Future work

Our review highlights the need for future research to evaluate the differential impact of small and large interventions, whether interventions elicit behavioural changes and the impact of teaching on clinical practice during long-term follow-up. Impact of teaching on patient care also requires study and could be based on markers of clinical assessment, management and patient/family feedback.

Conclusions

Most types of palliative care teaching interventions conducted with medical students improve knowledge. This provides useful information for medical schools when considering the teaching they currently provide, or aim to provide, in the future. The effect of undergraduate palliative care teaching on clinical practice has not been studied and warrants investigation. For all teaching approaches, constructive alignment and the communication of constructive alignment in educational studies should be considered to ensure adequate teaching impact. Further research into palliative care teaching should explicitly detail this alignment to allow for evaluation as to whether constructive alignment, not the teaching method, may be responsible for any effect of palliative care teaching interventions.

Medical students can learn about palliative care using a variety of methods; there is no definitive ‘best’ way to learn about palliative care. We have the responsibility to not just train medical students to pass exams, but to be safe and knowledgeable doctors. Given this, future research needs to assess the effect of teaching on clinical practice, including some analysis of patient-related outcomes, in order to discern the real-world impact of palliative care teaching interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Helen Elwell, clinical librarian, for her guidance and assistance on the use and refinement of search terms and searches.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Megan_EL_Brown, @gabs_finn

Contributors: JB designed the study, performed the searches, led on data collection, data analysis and drafted the article. MB and AD contributed to data collection, data analysis and writing of the article. JG and GF contributed to study design, analysis and writing of the article. All authors were responsible for approval of the final report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence End of life care for adults, 2017. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs13 [Accessed 3 Aug 2019].

- 2.World Health Organization WHO definition of palliative care, 2018. Available: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ [Accessed 3 Aug 2019].

- 3.APM Curriculum for undergraduate medical education, 2014. Available: http://www.apmuesif.phpc.cam.ac.uk/index.php/apm-curriculum [Accessed 7 Aug 2019].

- 4.General medical Council. Outcomes for graduates, 2018. Available: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/dc11326-outcomes-for-graduates-2018_pdf-75040796.pdf [Accessed 19 Aug 2019].

- 5.Walker S, Gibbins J, Paes P, et al. Preparing future doctors for palliative care: views of course organisers. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2018;8:299–306. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2017-001319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzpatrick D, Heah R, Patten S, et al. Palliative care in undergraduate medical Education-How far have we come? Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017;34:762–73. 10.1177/1049909116659737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med 2017;15:102. 10.1186/s12916-017-0860-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kingston A, Robinson L, Booth H, et al. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: estimates from the population ageing and care simulation (PACSim) model. Age Ageing 2018;47:374–80. 10.1093/ageing/afx201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, et al. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2012;1:2. 10.1186/2046-4053-1-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craane B, Dijkstra PU, Stappaerts K, et al. Methodological quality of a systematic review on physical therapy for temporomandibular disorders: influence of hand search and quality scales. Clin Oral Investig 2012;16:295–303. 10.1007/s00784-010-0490-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rouse DN. Employing Kirkpatrick's evaluation framework to determine the effectiveness of health information management courses and programs. Perspect Health Inf Manag 2011;8:1c. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pluye P, Gagnon M-P, Griffiths F, et al. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:529–46. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inform 2018;34:285–91. 10.3233/EFI-180221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, et al. Current methods of the US preventive services Task force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med 2001;20:21–35. 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00261-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg GR, Gliatto P, Karani R. Effect of a 1-week clinical rotation in palliative medicine on medical school graduates' knowledge of and preparedness in caring for seriously ill patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:1724–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brand AH, Harrison A, Kumar K. "It Was Definitely Very Different": An evaluation of palliative care teaching to medical students using a mixed methods approach. J Palliat Care 2015;31:21–8. 10.1177/082585971503100104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerlach C, Mai S, Schmidtmann I, et al. Does interdisciplinary and multiprofessional undergraduate education increase students' self-confidence and knowledge toward palliative care? Evaluation of an undergraduate curriculum design for palliative care at a German academic Hospital. J Palliat Med 2015;18:513–9. 10.1089/jpm.2014.0337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tai V, Cameron-Taylor E, Clark K. A mixed methodology retrospective analysis of the learning experience of final year medical students attached to a 1-week intensive palliative care course based at an Australian university. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2014;31:636–40. 10.1177/1049909113496451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz-Quach C, Wenzel-Meyburg U, Fetz K. Can elearning be used to teach palliative care? - medical students' acceptance, knowledge, and self-estimation of competence in palliative care after elearning. BMC Med Educ 2018;18:82. 10.1186/s12909-018-1186-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porter-Williamson K, von Gunten CF, Garman K, et al. Improving knowledge in palliative medicine with a required hospice rotation for third-year medical students. Acad Med 2004;79:777–82. 10.1097/00001888-200408000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Gunten CF, Mullan P, Nelesen RA, et al. Development and evaluation of a palliative medicine curriculum for third-year medical students. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1198–217. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green MJ, Levi BH. Teaching advance care planning to medical students with a computer-based decision aid. J Cancer Educ 2011;26:82–91. 10.1007/s13187-010-0146-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Day FC, Srinivasan M, Der-Martirosian C, et al. A comparison of web-based and small-group palliative and end-of-life care curricula: a quasi-randomized controlled study at one institution. Acad Med 2015;90:331–7. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tse CS, Ellman MS. Development, implementation and evaluation of a terminal and hospice care educational online module for preclinical students. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:73–80. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorner L, Schwarzkopf D, Skupin H, et al. Teaching medical students to talk about death and dying in the ICU: feasibility of a peer-tutored workshop. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:162–3. 10.1007/s00134-014-3541-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellman MS, Fortin AH, Putnam A, et al. Implementing and evaluating a four-year integrated end-of-life care curriculum for medical students. Teach Learn Med 2016;28:229–39. 10.1080/10401334.2016.1146601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brownfield E, Santen S. A short palliative care experience: beginning to learn. Med Educ 2009;43:1111–2. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03486.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang H-H, Hu W-Y, Tsai SSL, et al. Reflections on an end-of-life care course for preclinical medical students. J Formos Med Assoc 2009;108:636–43. 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60384-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai SSL, Hu W-Y, Chang H-H, et al. Effects of a multimodule curriculum of palliative care on medical students. J Formos Med Assoc 2008;107:326–33. 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60094-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paneduro D, Pink LR, Smith AJ, et al. Development, implementation and evaluation of a pain management and palliative care educational seminar for medical students. Pain Res Manag 2014;19:230–4. 10.1155/2014/240129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson WC, Connor DPD, Tavernier L. Antemortem care in an afternoon: a successful four-hour curriculum for third-year medical students. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2002;19:338–43. 10.1177/104990910201900511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auret K, Starmer DL. Using structured clinical instruction modules (SCIM) in teaching palliative care to undergraduate medical students. J Cancer Educ 2008;23:149–55. 10.1080/08858190802043302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan A, Ross SP, Duerksen K. Death is not always a failure: outcomes from implementing an online virtual patient clinical case in palliative care for family medicine clerkship. Med Educ Online 2013;18:22711. 10.3402/meo.v18i0.22711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biggs J, Tang C. Applying constructive alignment to outcomes-based teaching and learning, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang JTH, Schembri MA, Hall RA. How much is too much assessment? Insight into assessment-driven student learning gains in large-scale undergraduate microbiology courses. J Microbiol Biol Educ 2013;14:12–24. 10.1128/jmbe.v14i1.449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of clinical oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:880–7. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hui D, Bruera E. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:159–71. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirkpatrick DKJ. Evaluating training programs: the four levels. 3rd edn, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-036458supp001.pdf (35KB, pdf)