Abstract

Immune-related myositis is one of the rare immune-related adverse events whose underlying precise mechanisms are not fully understood. Here, we describe a case of immune-related myositis that developed after four cycles of combination therapy with nivolumab plus ipilimumab for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Negative results of autoimmune antibodies, including anti-acetylcholine receptor and anti-muscle-specific kinase antibodies suggested a T-cell-mediated mechanism. After recovery with steroid therapy, the patient resumed nivolumab monotherapy and survived without any evidence of disease progression or refractory of myositis. Differential diagnosis between T-cell-mediated and B-cell-mediated immune-related myositis and its impact on optimal management are discussed.

Keywords: urinary and genital tract disorders, urological cancer, urological surgery

Background

Advances in our understanding on immune checkpoint mechanisms, which can be exploited by cancer cells to achieve immune resistance, have led to the development of novel anticancer therapy called immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Nivolumab, a programmed death-1 (PD-1) antibody,1 and the combination therapy of nivolumab plus ipilimumab, an anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody,2 have become a mainstay of treatments for advanced renal-cell carcinoma (RCC) based on the overall survival benefit. However, ICIs are associated with unique adverse events called immune-related adverse events (irAEs),3 which can sometimes be severe and life-threatening.

Although irAEs may occur at any organ, the most commonly affected organs are skin, gastrointestinal tract and endocrine glands. Immune-related myositis is a rare irAE and its underlying mechanisms are not fully understood.4 Here, we describe a case of immune-related myositis developed after four cycles of combination therapy with nivolumab plus ipilimumab and five cycles of nivolumab monotherapy for treatment of metastatic RCC, wherein clinical and laboratory findings, including negative autoimmune antibodies, suggested T-cell-mediated mechanisms.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old man was referred to our hospital due to dry cough and weight loss of 6 kg within half a year. The patient had a prior history of hypertension and diabetes, but none of autoimmune disease. A CT scan of the chest and abdomen revealed a left renal tumour 7 cm in size and multiple pulmonary metastases. Positron emission tomography scan detected multiple bone metastases at the left ilium and left femur, and mediastinum lymph node metastases (figure 1). His general status was fine with Karnofsky performance status of 100 and he was categorised into an intermediate-risk group according to International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) risk criteria (one prognostic factor: time from diagnosis to treatment <1 year).5 Therefore, we performed cytoreductive nephrectomy for left renal cancer and pathological diagnosis was clear cell RCC, pT3a, grade 2>3 and Fuhrman grade 2 >3.

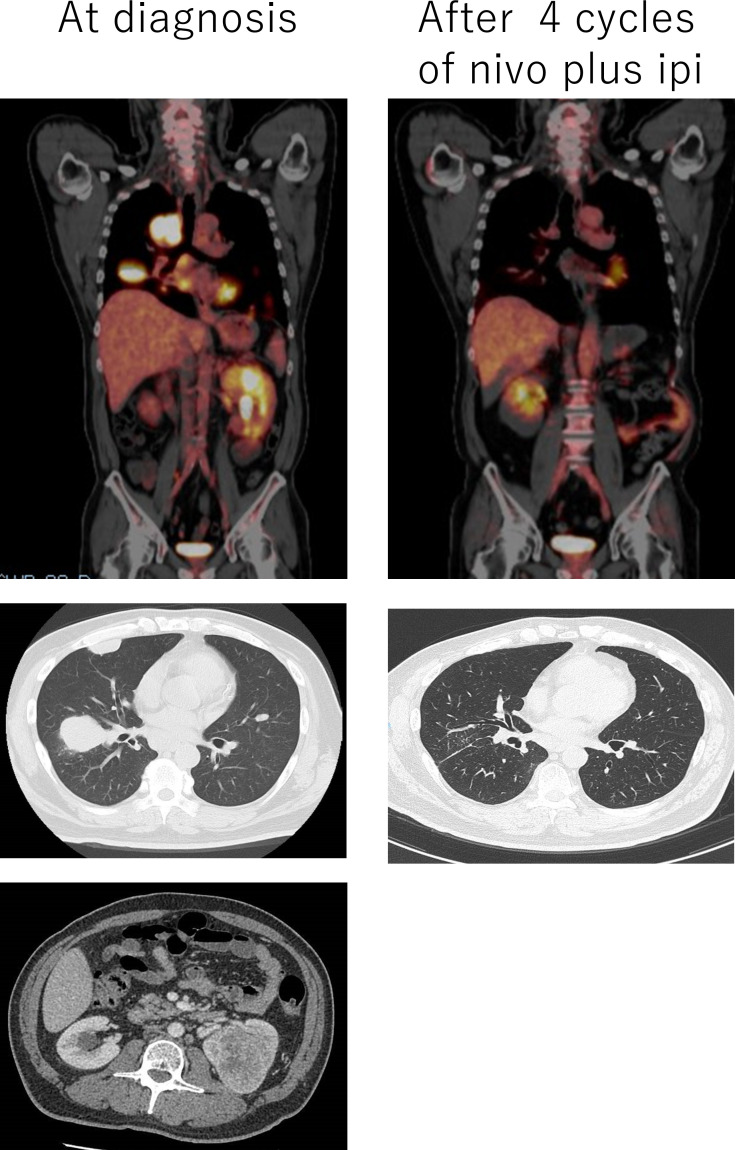

Figure 1.

CT scan and positron emission tomography scan findings before and after four cycles of combination therapy with nivolumab plus ipilimumab.

Combination therapy with nivolumab plus ipilimumab was started under-diagnosis of metastatic RCC, pT3aN0M1 (pulmonary, osseous, and lymph nodes metastases). After the initial four cycles of combination therapy, objective partial responses in pulmonary metastases and mediastinum lymph nodes were observed (figure 1). However, the patient developed malaise and joint pain. Although there was no definitive diagnosis of irAE, corticosteroid therapy (prednisone 30 mg/day) was empirically started. As these symptoms improved promptly, we continued nivolumab monotherapy. After five cycles of nivolumab monotherapy, the patient noticed weakness and myalgia in the lower extremity. As irAEs, such as immune-related myositis or myasthenia gravis, were suspected, the patient was immediately hospitalised.

Investigations

Manual muscle× test findings were as follows: gluteus maximus (4), gluteus medius (4) and iliopsoas muscle (4). Eye movement disorder and ptosis were not observed. Laboratory tests showed elevated levels of white cell count (13.3×109L, reference range: 3.3–8.6×109/L), aspartate aminotransferase (86 U/L, reference range: 13–30 U/L), creatinine (2.16 mg/dL, reference range: 0.65–1.07 mg/dL), creatine kinase (CK: 9117 U/L, reference range: 59–248 U/L), CK-myocardial band (CK-MB 62 U/L reference range:<25 U/L) and C reactive protein (CRP: 27.64 mg/dL, reference range:<0.14 mg/dL). Tests for serologic paraneoplastic antibodies, including antiacetylcholine receptor (AchR), antimuscle-specific kinase (MuSK), anti-Jo-1 and antiaminoacyl-tRNA synthetase antibodies, were negative. ECG revealed no abnormal findings. The MRI study revealed high signal intensity at quadriceps muscle under short-TI inversion recovery conditions, indicating myositis. As immune-related myositis was highly suspected, a muscle biopsy was omitted, although muscle biopsy may provide additional information such as the infiltration of inflammatory cells.

Differential diagnosis

The patient’s clinical symptoms (weakness and myalgia in lower proximal extremity), neurologic findings (proximal myopathy), laboratory tests (elevated creatinine, CK and CRP) and MRI findings (inflammation at quadriceps muscle) concordantly suggested the possibility of immune-related myositis. Negative findings of autoantibodies and the absence of eye movement disorder and ptosis indicated that myasthenia gravis was not likely. Relatively low CK-MB level compared with the extremely high CK level and normal ECG findings excluded the possibility of myocarditis.

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy and diabetic myopathy are a possible differential diagnosis of ICI-induced myopathy. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy, such as dermatomyositis and polymyositis, may have an overlap of clinical and laboratory findings with ICI-induced myositis because both of these are autoimmune-related conditions. Myositis autoantibodies could be negative in ICI-induced myositis, whereas up to 80% of patients with idiopathic myopathy have positive autoantibodies; however, these two conditions could not be differentiated by the presence of autoantibodies because a subset of ICI-induced myositis are B-cell-mediated (discussed below). ICI-induced myositis has a more sudden onset without fluctuation of symptoms, compared with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy.4

Diabetic myopathy, a failure to preserve muscle mass and function, is a common feature of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Although the detailed mechanisms of muscular injury in diabetic patients were not fully elucidated, the impact of hyperglycemic osmotic stress is postulated.6 As diabetic myopathy is not associated with autoimmune inflammation, it could be differentiated from ICI-induced myopathies.

Treatment

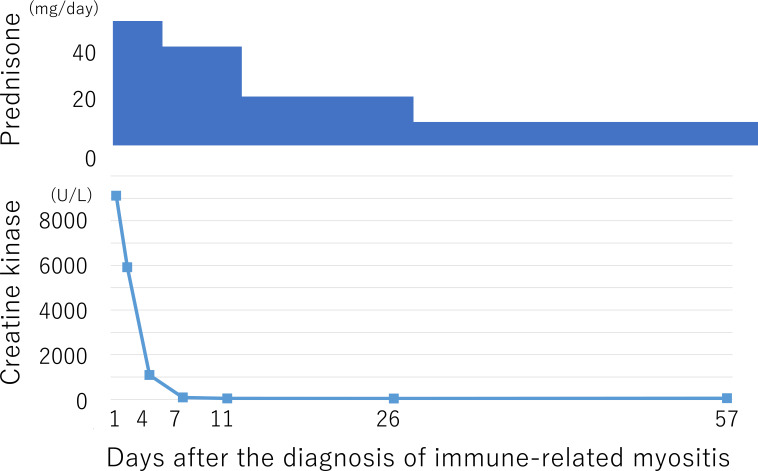

The patient started corticosteroid therapy at an initial dose of prednisone 50 mg/day (1 mg/kg/day), and his symptoms promptly improved. Corticosteroid therapy was tapered to 5 mg/day within 1 month and continued at this dose as maintenance therapy (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trend in creatine kinase levels after corticosteroid therapy.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient remained on nivolumab monotherapy and maintenance steroid therapy. He survived without any evidence of disease progression or refractory of myositis for 9 months at the time of this publication.

Discussion

Although ICIs have shown great promise in the treatment of various cancers, their use can be limited by the occurrence of severe irAEs. Immune-related myositis is one of the rare irAEs with a reported incidence of 0.76%,7 and it could be severe and life-threatening. As it has been infrequently documented in clinical trials, most of our knowledge come from case reports. The precise mechanisms of immune-related myositis induced by ICIs remain to be elucidated. Currently, both T-cell-mediated responses directed against unidentified muscle antigens and B-cell-mediated mechanisms with positive autoantibodies are considered to be responsible for this rare toxicity. It is also known that immune-related myositis induced by ICIs may coincide with myasthenia gravis (or myasthenic syndrome) and myocarditis. Shah et al reported six cases of ICI-related myositis, in which two cases were accompanied by myasthenic syndrome, and one had cardiomyositis. As autoantibody was detected only in two of the six cases, the T-cell-mediated mechanism was mostly suspected for these cases.8 In the current case, negative results of serologic paraneoplastic antibodies, and other clinical findings also, suggested a T-cell-mediated mechanism.

Several authors have reported the case of ICI-induced T-cell-mediated myositis. Johnson et al reported two cases of myocarditis accompanied with fulminant myositis, in which the T-cell-mediated mechanism was confirmed by muscle biopsy.9 Valenti-Azcarate et al also reported a case of T-cell-mediated myositis and myocarditis induced by nivolumab and ipilimumab, wherein screening tests for autoantibodies were negative and T-cell infiltration was proven by muscle biopsy.10 Sometimes, patients with T-cell-mediated immune-related myositis may develop similar symptoms to myasthenia gravis. In such cases, these symptoms were described as ‘myasthenia-like’ symptoms. Notably, all these patients do not present with typical myositis antibodies, suggesting that this is not merely an exacerbation of the pre-existing autoimmune disease.

In contrast, ICI-induced immune-related myositis considered to be mediated by B-cell functions have also been reported. Bilen et al reported the case of rhabdomyolysis with severe polymyositis following ipilimumab-nivolumab treatment in urothelial cancer patients with pre-existing antistriated muscle (SM) antibody.11 Likewise, Shirai et al reported ICI-induced myasthenia gravis with myositis and myocarditis in a melanoma patient with pre-existing anti-AchR and anti-SM antibodies.12 In these cases, ICIs may exacerbate underlying autoimmune conditions, as evidenced by elevated pre-existing autoantibodies. Further studies are needed, however, to determine whether these patients with pre-existing autoantibodies are at a higher risk of developing myositis with ICIs.

In some cases, discrimination between T-cell-mediated and B-cell-mediated myositis might be difficult due to overlapping clinical symptoms. Elevated CK, muscle inflammation on MRI, a myopathic pattern on electromyogram (EMG) and inflammatory myopathy findings with T-cell infiltration on muscle biopsy can confirm the diagnosis of T-cell-mediated immune-related myositis.13 Meanwhile, the presence of autoantibodies such as anti-AchR, anti-SM and anti-MuSK antibodies, positive response to cholinesterase inhibitors, decremental responses to repetitive nerve stimulation or abnormal single fibre EMG support the diagnosis of B-cell-mediated immune-related myositis accompanied by myasthenia gravis.13

Management of irAEs is generally based on corticosteroids and other immunomodulating therapies. Early recognition and prompt treatment with a multidisciplinary approach are crucial for improving clinical outcomes. For T-cell-mediated myositis, high-dose corticosteroids therapy (1–2 mg/kg/day) is generally recommended. For patients with necrotising myopathy, aggressive immunosuppressive therapy is required due to their grave prognosis.7 As for B-cell-mediated myositis, corticosteroid therapy is also recommended as first-line therapy. However, for those who do not respond well to steroid therapy, more intensive therapies, including plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, azathioprine, cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil, should be considered.13

Rechallenge with ICIs is a debatable topic because patients who developed irAEs are at high risk for developing severe toxicities again on rechallenge with ICIs, despite the fact that those patients may derive clinical benefit from this approach. Although there has been no solid consensus, the use of astandard dose of ICIs concurrent with prophylactic immunosuppressive therapy is recommended at rechallenge.14 The current case received rechallenge of nivolumab monotherapy with maintenance steroid therapy, and then survived without progression of the disease and refractory of myositis, suggesting the role of rechallenge with ICIs after irAEs. Moreira et al reported that 9 of the 38 cases of immune-related myositis induced by ICIs successfully treated with rechallenge.4

Learning points.

Immune-related myositis is a rare, but important immune-related adverse events (irAEs) could be induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Although its precise mechanisms are not fully understood, both T-cell-mediated and B-cell-mediated mechanisms seem to exist.

Screening for serologic paraneoplastic antibodies would be useful in discriminating T-cell-mediated and B-cell-mediated mechanism, and may help in optimal management of this rare irAE.

Footnotes

Contributors: The patient was under the care of AN. Acquisition and interpretation of data were done by NO and TK. The report was written by NO and TK, and was supervised by TK.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1803–13. 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1277–90. 10.1056/NEJMoa1712126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-Related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 2018;378:158–68. 10.1056/NEJMra1703481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreira A, Loquai C, Pföhler C, et al. Myositis and neuromuscular side-effects induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer 2019;106:12–23. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heng DYC, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5794–9. 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernández-Ochoa EO, Vanegas C. Diabetic myopathy and mechanisms of disease. Biochem Pharmacol 2015;4:5. 10.4172/2167-0501.1000e179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liewluck T, Kao JC, Mauermann ML. PD-1 inhibitor-associated myopathies: emerging immune-mediated myopathies. J Immunother 2018;41:208–11. 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah M, Tayar JH, Abdel-Wahab N, et al. Myositis as an adverse event of immune checkpoint blockade for cancer therapy. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2019;48:736–40. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1749–55. 10.1056/NEJMoa1609214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valenti-Azcarate R, Esparragosa Vazquez I, Toledano Illan C, et al. Nivolumab and Ipilimumab-induced myositis and myocarditis mimicking a myasthenia gravis presentation. Neuromuscul Disord 2020;30:67–9. 10.1016/j.nmd.2019.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilen MA, Subudhi SK, Gao J, et al. Acute rhabdomyolysis with severe polymyositis following ipilimumab-nivolumab treatment in a cancer patient with elevated anti-striated muscle antibody. J Immunother Cancer 2016;4:36. 10.1186/s40425-016-0139-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirai T, Kiniwa Y, Sato R, et al. Presence of antibodies to striated muscle and acetylcholine receptor in association with occurrence of myasthenia gravis with myositis and myocarditis in a patient with melanoma treated with an anti-programmed death 1 antibody. Eur J Cancer 2019;106:193–5. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Astaras C, de Micheli R, Moura B, et al. Neurological adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: diagnosis and management. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2018;18:3. 10.1007/s11910-018-0810-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haanen J, Ernstoff M, Wang Y, et al. Rechallenge patients with immune checkpoint inhibitors following severe immune-related adverse events: review of the literature and suggested prophylactic strategy. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000604. 10.1136/jitc-2020-000604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]