Abstract

Introduction

Telemedical lifestyle programmes for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) provide an opportunity to develop a healthier lifestyle and consequently to improve health outcomes. When implementing new programmes into standard care, considering patients’ preferences may increase the success of the participants. This study aims to examine the preferences of people with T2DM with respect to telemedical lifestyle programmes, to analyse whether these preferences predict programme success and to explore the changes that may occur during a telemedical lifestyle intervention.

Methods and analysis

We outline the protocol of the development and assessment of a discrete choice experiment (DCE) to examine patient preferences in a telemedical lifestyle programme with regard to the functions of the online portal, communication, responsibilities, group activities and time requirements. To develop the design of the DCE, we conducted pilot work involving healthcare experts and in particular people with T2DM using cognitive pretesting. The final DCE is being implemented within a randomised controlled trial for investigating whether participation in a telemedical lifestyle intervention programme sustainably improves the HbA1c values in 850 members of a large German statutory health insurance with T2DM. Preferences are being assessed before and after participants complete the programme. The DCE data will be analysed using regression and latent class analyses.

Ethics and dissemination

The DCE study has been approved by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of the Heinrich Heine University Duesseldorf, registration number 2018-242-ProspDEuA, registered on 6 December 2018. The TeLIPro trial is registered at the US National Library of Medicine, registration number NCT03675919, registered on 15 September 2018. We aim to disseminate our results in peer-reviewed journals, at national and international conferences and among interested patient groups and the public.

Keywords: telemedicine, statistics & research methods, protocols & guidelines, health economics, general diabetes, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We are using a discrete choice experiment (DCE) to assess the preferences of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus participating in TeLIPro, a telemedical lifestyle programme, before and after they complete the programme.

Programme preferences may be used to further develop the TeLIPro Health Programme.

DCE data will enable us to retrieve relative preference weights from which we can learn which components of a telemedical lifestyle programme are most important to the participants.

Since the DCE was developed on the basis of the TeLIPro trial, the transferability of the DCE to other telemedical lifestyle programmes will be limited.

Introduction

The prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in the world is continuously increasing.1 In 2019, more than 9.5 million adults were diagnosed with diabetes in Germany, most of them with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).2 Besides antihyperglycaemic treatment, an effective T2DM therapy includes programmes aimed at lifestyle changes, including changes in dietary habits and improvements in physical activity. Since these programmes have significantly reduced T2DM participants’ haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, they may help to reduce the progression of the disease.3–7 Thus, lifestyle programmes have been included in clinical guidelines and international position statements for the treatment of people with T2DM.8–10

Digital health technologies and coaching approaches are playing increasingly important roles in healthcare in diabetes.11–17 Telemedical health programmes offer up-to-date easy access and most notably a location-independent way to support patients in managing their diabetes, using technical aids such as apps, internet platforms and mobile measurement devices and often including a personal health coach.11–14 A proof of concept study showed that participation in a telemedical health intervention programme that focused on eating behaviour, but also included support from a personal health coach, led to significant reductions in HbA1c, weight, blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors in people with T2DM.12

Little is known about the underlying decision-making process regarding the participation and adherence of the target groups to telemedical lifestyle programmes. One promising approach to examine why some people participate and succeed in lifestyle-changing programmes and others do not is to ask patients about their preferences for these programmes. As one integral part of the multidimensional concept of patient-centeredness,18 preferences determine which alternative is most favourably evaluated by patients (eg, which type of lifestyle programme is preferred).

Preferences can be determined not only for entire programmes but also for different components that make up a programme (eg, the duration or intensity of a programme). These components might be evaluated differently by participants. Multi-attribute methods, such as the discrete choice experiment (DCE),19–21 can help to identify preferred components, which are important for achieving better programme outcomes. To date, studies using a DCE to elicit preferences in people with diabetes have mostly examined preferences regarding treatment22–26 and lifestyle changes.27–29 Thus, there remains a need to clarify patients’ preferences regarding the relative importance of components with respect to telemedical lifestyle programmes and coaching approaches (eg, involvement of the coach, internet platforms, mobile measurement instruments or type of support). Knowledge of these preferences and the identification of groups of patients with similar preferences may be helpful for identifying new programme participants and for developing new or adapting existing health programmes by designing them in a more tailored and preference-oriented way.

It is also important to ask whether preferences are associated with programme success. A match between the preference for and the content of a programme is likely to improve a participant’s adherence to and willingness to participate in a programme and thus the success of the programme in the form of better outcomes. Studies in which participants were matched to entire lifestyle programmes in accordance with their preferences found significant, although small, positive effects on treatment outcomes.30–34 To the best of our knowledge, associations between preferences for certain components of telemedical lifestyle programmes and programme success have not been investigated in diabetes care using DCE methodology. Knowledge of which particular components contribute to the success of telemedical lifestyle programmes may be helpful for modifying programmes accordingly.

Another question that arises is whether participants’ preferences change while they are participating in a telemedical lifestyle programme. In principle, preferences are assumed to be stable.35–37 However, as expressed preferences depend on individual information and experience, they may change as participants receive more information about the programme and its components during participation. Similar effects have been found for preferences with regard to cancer screening. Detailed information about recommended invasive follow-up testing for individuals at risk had negative effects on individuals’ decision to participate in a non-invasive screening.38 Knowledge of changes in preferences in individuals with diabetes participating in telemedical lifestyle programmes would be helpful for adapting the components of a programme as it progresses.

Contribution to the field and aims

With this study, we aim (1) to measure the preferences of people with T2DM regarding telemedical lifestyle programmes and coaching approaches and to analyse the heterogeneity of these preferences, (2) to investigate whether preferences predict programme success and (3) to compare participants’ preferences before and after the intervention.

Methods and analysis

Patient preferences for telemedical lifestyle programmes and coaching approaches are being elicited with a DCE in individuals who are participating in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) for testing the effectiveness of the telemedical lifestyle intervention programme TeLIPro.39 Participants of the RCT are also taking part in the DCE. The DCE uses the infrastructure of the RCT for data collection. However, the DCE does not influence the RCT, the selection of participants, or the randomised assignment of the participants. In the following, we first describe the TeLIPro Health Programme briefly. After this, we outline the development of the DCE and its assessment within the RCT.

The TeLIPro health programme

TeLIPro (TeLIPro Health Programme—Active with Diabetes) is a telemedical lifestyle programme in Germany designed to help people with T2DM implement a healthy lifestyle through patient-centred and personal care.39 Participants receive telemedical devices, access to a secured telemedical online portal and telemedical coaching from a personal health coach who supports and accompanies them for the duration of the programme. The programme is intended to improve blood glucose levels and therefore to improve or maintain the health status and the quality of life of the participants in the long-term. Ultimately, this should reduce the risk for concomitant and secondary diseases. The integration of the technology also supports the scalability of the programme, enabling it to meet the individual preferences and needs of the participants.

Development of the DCE to measure patient preferences

To measure preferences, we are employing a DCE, a stated preference method, which is the predominant method for eliciting patient preferences in all fields of healthcare.40–44 The DCE methodology—based on the Random Utility Theory—allows researchers to estimate and contrast the relative strengths of preferences across a range of particular attributes. The first step in developing a DCE is to define the research problem under consideration (eg, measuring patient preferences for telemedical lifestyle programmes) and to adequately transfer it into an experimental framework.19 20 The task comprises the identification and selection of attributes that reflect all characteristics relevant for a decision in the context of the research problem. The attributes (eg, cost or duration of treatment) of the research problem are further specified by different levels (eg, cost of $50 or $500 and 2, 3 or 4 hours). To construct an experimental design, the levels of the attributes are systematically varied and presented in a series of choice sets each with the same number of alternatives (typically two alternatives). By standard economic theory, it is assumed that individuals will choose the alternative that maximises their utility. The preference weights for attributes and levels (part-worth preference weights) constitute the overall utility of an alternative. Thus, observed choices provide information about the relative weights of preferences for attributes and levels as well as about the overall utility of each alternative.45 We are primarily interested in the preferences of participants who already decided to participate in a telemedical coaching programme. Thus, we did not include an opt-out option because respondents have already chosen to participate in TeLIPro. To identify and select attributes and levels, we followed the current literature on the development of DCEs and implemented the following steps: (1) compilation of evidence, (2) consultation of experts, (3) consultation of people with diabetes as relevant actors, (4) pretest and (5) pilot test.46 47

Compilation of evidence

First, we conducted a literature search to identify attributes used in DCEs to elicit preferences regarding lifestyle changes, coaching and devices (see online supplemental material). Based on the literature search, we summarised attributes regarding how comfortable the devices are to wear, the handling of the devices, the frequency of contact with the general practitioner (GP) or the health coach, emotional support during the programme, responsibility for the physical activity schedule or diet schedule and the time investment. We did not include monetary costs in our summary, because payments for the provision of healthcare in Germany are normally paid directly by the statutory health insurance, and therefore monetary costs are less relevant than the time investment for preferences regarding telemedical lifestyle programmes.

bmjopen-2020-036995supp001.pdf (131.2KB, pdf)

Consultation of experts

Second, we discussed the attributes with healthcare experts (see ‘Acknowledgements’ section) to ensure that the healthcare perspective, telehealth and the clinical perspective were incorporated in the DCE. This process leads to a preliminary list of attributes (1) considering any possible attribute thought to be relevant to telemedical lifestyle programmes for people with T2DM, (2) including attributes with a special relevance for TeLIPro in order to best adapt patient preferences to the intervention envisaged in the project and (3) including those who could be realistically described in the choice scenario and were potentially amenable to change. This resulted in a list of seven attributes with two to five levels: the functions and handling of the online portal, the contacts to coach compared with GP contacts, the transfer of knowledge about a healthier lifestyle, emotional support, exercise plan, nutrition plan and the total time required for the programme. This list formed the basis for the DCE design. The alternative attributes: communication between coach and doctors, competence of the coach, total number of contacts to coach, duration of the programme, intensity of the exercise programme and exercise in groups or individually were used in the pretest.

Consultation of people with diabetes/pretest

Third, we conducted qualitative interviews in the form of a cognitive pretest with five individuals with diabetes (December 2018 and January 2019). Participants were recruited from the self-help group (n=2) at the German Diabetes Center in Duesseldorf, Germany, and a specialised diabetes care practice (n=3) in Leverkusen, Germany, by email or personal contact. They participated on a voluntary basis and gave written informed consent prior to being included in the study. The interviewers were two researchers from the Institute for Health Services Research and Health Economics. Interviews were conducted face-to-face at the German Diabetes Center, the diabetes care practice and the participants’ homes. All interviews were logged and audiotaped. The individual interviews were conducted in order to ensure that (1) the most important attributes were included in the DCE, (2) none of the chosen attributes was dominant, (3) proper levels were appointed to each of the attributes and (4) the task and the wording used in the questionnaire were comprehensible and feasible.19 45 For the qualitative interviews, we developed a guideline based on cognitive pretesting, including think-aloud methods, demand techniques (understanding individual words), paraphrasing (reproducing tasks) and sorting techniques (attributes were presented to participants on cards, and participants sorted them by personal relevance). In the first part of the interview, we introduced respondents to TeLIPro, and the questionnaire was presented piece by piece. To obtain more insight into how respondents understood the choice task, they were asked to think aloud during the interview. In addition, respondents were told to identify attributes and levels they did not understand or found hard to grasp and to provide suggestions for improvement. In the second part, all seven attributes of the DCE were presented on separate paper cards. Respondents were asked whether they could think of any other attributes that were important but had not been included so far. If so, the interviewer wrote these new attributes on blank cards, and respondents were asked what they considered important about these attributes and what kinds of levels of the attribute they could think of. If no more new attributes were mentioned, the additional cards with the six alternative attributes were laid out and explained to the respondents by the interviewer. Next, respondents were asked if they would swap one or more of the six alternative attributes or—if new attributes were mentioned—if they would swap the new attributes with one or more of the seven attributes in the programme. Two researchers reviewed the interviews and adjusted the DCE after an internal discussion. The attribute ‘emotional support’ was swapped with ‘group activities’, which was also modified to include the non-exercise group activities. The attribute ‘frequency of contacts’ was changed to ‘communication between coach and doctors’. It asks if the coach and doctors have contact with each other instead of the patient to doctor and patient to coach ratios. The attribute named ‘the transfer of knowledge about a healthier lifestyle’ was changed to ‘responsibility for getting acquainted with a healthier lifestyle’. The level ‘4 hours per week’ was removed from the attribute ‘total time required’ because it was deemed unrealistic by respondents. The attributes ‘exercise plan’ and ‘nutrition plan’ were merged into ‘responsibility for setting goals to exercise and menu schedule’ because both attributes targeted the domain of autonomy, and the majority of the respondents swapped out one of these attributes. The description of the task concerning the selection of the choice sets was also rephrased to be more precise. This reduction in the number of attributes to six and the number of levels to two to four ensured an efficient design while also allowing the number of choice sets to be limited to a practicable number to prevent a mental burden that was too high for the participants. It was ensured that one combination of levels reproduced the actual TeLIPro health programme.

Pilot test

Fourth, we presented the revised DCE to the members of the self-help group (n=10) at one of their monthly meetings. On a pilot test, they answered a paper–pencil version of the DCE questionnaire and were asked at the end of the questionnaire if they had any suggestions for improvement. On the basis of these results, the attributes and levels, as well as their descriptions in the questionnaire, were not changed. The DCE instructions concerning the selection of the choice sets was again rephrased to clarify that the most preferred or least disliked programme of the two had to be chosen. The final six attributes with their corresponding levels are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Final attributes and corresponding levels included in the DCE

| Attributes | Descriptions | Levels |

| The functions and handling of the online portal | During the coaching programme, you are provided with different devices to measure your weight, your blood glucose and the steps you have walked. These devices automatically transfer your data to an online portal that you and your coach can access. The range of functions and the handling of the online portal can differ for different programmes. The more functions the online portal offers, the more complex the handling becomes. | Extensive functions and more complex handling |

| Less extensive functions and easier handling | ||

| Communication between coach and doctors | Coaching programmes can differ on the basis of whether your coach and your doctors communicate about your treatment, the programme goals you have set, and your data in the online portal. | My coach and my doctors do not communicate |

| My coach and my doctors do communicate | ||

| Responsibility for getting acquainted with a healthier lifestyle | Coaching programmes can provide you with information about various opportunities for lifestyle changes. | I receive information from my doctor |

| I receive information from my coach | ||

| I search for information myself | ||

| Group activities | Some coaching programmes contain activities in groups of 10–15 participants each. The activities include sports activities, cooking together and also the exchanging of experiences by the group members in an online forum. | No group activities |

| Group activities | ||

| Responsibility for setting goals to exercise and menu schedule | One part of the coaching programme is setting goals to exercise and eat well. | My coach sets my goals |

| I set my goals independently | ||

| My coach and I set my goals together | ||

| Total time required | Coaching programmes may differ in the amount of time you have to spend on the programme. This includes the time spent fulfilling your movement goals, talking to your coach, changing your diet and using your devices correctly. The time required for potential group activities is not included. | 12 hours/week |

| 10 hours/week | ||

| 8 hours/week | ||

| 6 hours/week |

DCE, discrete choice experiment.

DCE questionnaire design

The combination of the attributes in the different scenarios of the DCE and the compilation of the scenarios was based on the number and levels of the attributes as well as other content and statistical requirements. SAS macros (SAS V.9.4) were used to define the optimal number of choice sets.48 Particular care was taken to ensure that combinations of levels were realistic. The number of total choice sets takes respondents’ cognitive capacity into account. The efficient factorial fractional design (D-error=0.12) consisted of 12 unique choice tasks. To control for the reliability of the choices that were made, choice set 7 was repeated as choice set 13, resulting in a total of 13 choice sets.

Assessment of the DCE within the RCT

The collecting of the DCE data is integrated into the collecting of the RCT data. Therefore, all RCT participants are asked to respond to the DCE. Next, we first describe the RCT, and then we describe the assessment of the DCE.

The RCT: the TeLIPro trial

The trial is aimed at assessing whether participating in the telemedical lifestyle programme TeLIPro can improve the HbA1c levels of people with T2DM. According to the sample size calculation computed for the RCT, 850 participants were recruited from within the members of a German statutory health insurance (Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse Rhineland/Hamburg, AOK, Germany) via informational letters and reminder telephone calls. Inclusion criteria consist of a T2DM diagnosis, age between 18 and 67 years, HbA1c ≥6.5%, body mass index (BMI) ≥27 kg/m² and a willingness to participate in the study. Participants are given detailed information about the programme and provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria consist of factors that would prevent successful participation in the programme, for example, acute infections, addictions or dementia, as well as insufficient knowledge of the German language. Participants are being randomised (1:1) into an intervention group (IG) and a control group (CG). Participants of the IG are given a scale, a step counter, access to a telemedical online portal, a data hub for transmitting the measured values to the online portal, a glucose metre with test strips for the self-monitoring of blood glucose and telemedical telephone coaching from a personal health coach in addition to routine care. The number and duration of interactions between the health coach and the individuals in the IG are determined by the needs of the participants (on average 14 interactions over the course of the intervention with a duration of 10–30 min each). The health coach encourages the participant, and they set goals together (ie, behavioural changes concerning physical activity and eating). For the IG, the measures of blood glucose are recorded continuously, and pedometer data and weight (on a daily or weekly basis) are automatically transmitted to the online portal by the devices. The data can be viewed by both the participant and the coach. If a previously determined target value is exceeded or not reached, an alert is triggered and the coach may decide to intervene. In addition to the monitoring function, the online portal provides information to support the change in lifestyle and enable participants to manage their illness autonomously, for example, text-based information on illness, nutrition, exercise, motivation and health parameters. Furthermore, functions are available for communication and information exchange between the actors who are involved: participant and coach, as well as the attending GP or relatives with the participant's consent. Therefore, it is easy to exchange information and adapt the therapy. The intervention will last 12 months. Participants of the CG are not accompanied by a coach. Except for this, they receive the same components of the programme as the IG.

To start, participants register in the online portal and are asked for sociodemographic factors (sex, age, employment status and education) and the duration of their diabetes. Afterwards, the intervention begins. Participants are given devices and the IG is contacted by the personal health coach. In the online portal, all participants answer questionnaires about their health-related quality of life (Short-Form-Health Survey 12; SF-12), impairment due to depressive symptoms (German version of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale; CES-D Scale), eating behaviour (German version of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire; FEV) and exercise behaviour (Global Physical Activity Questionnaire; GPAQ)49–52 at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 1 year (completion of the intervention), 15 months (follow-up phase) and 18 months (follow-up phase) after baseline. If a questionnaire is not answered within 2 weeks, participants are reminded by a telephone call from the online portal service staff. On a quarterly basis, the participants’ HbA1c level, BMI, fasting blood glucose, blood pressure, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL)/low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, antihyperglycaemic treatment and blood pressure medication are assessed by asking the attending GP. Body weight is recorded weekly, and walked steps are recorded daily by the devices for both groups. For the IG, blood glucose is monitored daily. The primary outcome is the HbA1c level. Secondary outcomes include cardiovascular risk factors, health-related quality of life and medication. The analysis of the effectiveness and health economic evaluation of the TeLIPro trial will be the topic of a later publication.

Assessment of the DCE

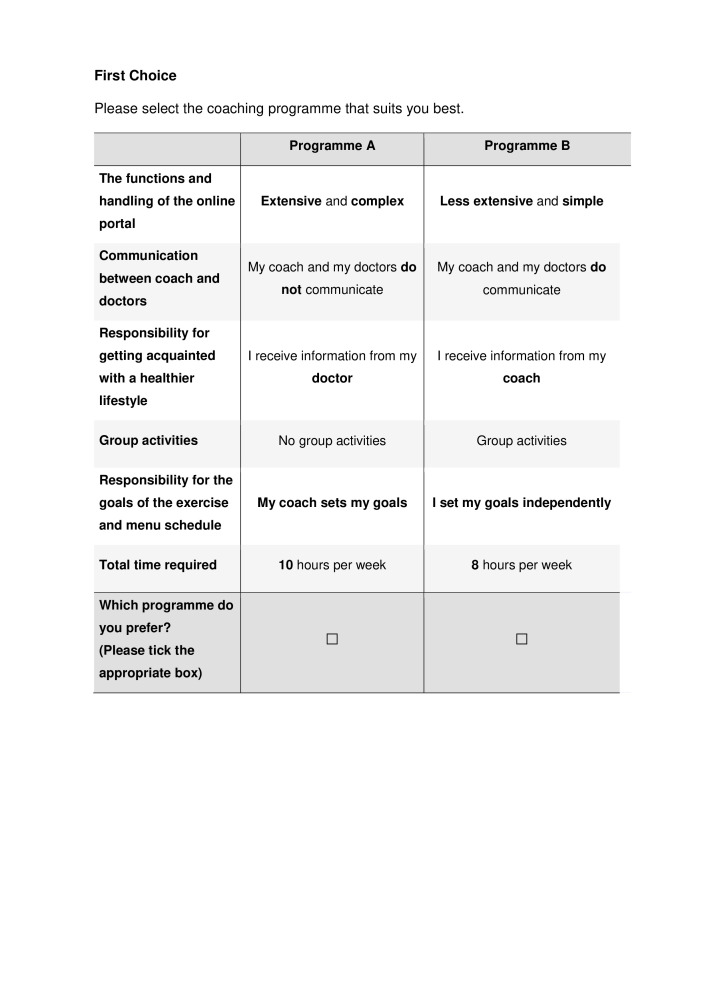

To address the DCE, respondents are provided with an extensive explanation of the meanings of all attributes and levels as well as information on how to deal with a choice set, accompanied by an example. Afterwards, respondents are told that they need to choose between two lifestyle programmes in the following choice sets. They are told that 13 choice sets are best suited for determining what type of lifestyle programme is preferred. Respondents are told to always choose their personally best-suited or least-rejected lifestyle programme and that there are no right or wrong answers. They are also reminded that they always opt for a programme with all the features listed. Every choice task is accompanied by the invitation: ‘Please select the coaching programme that suits you best’. Then both programmes (Programmes A and B) are presented (see figure 1) followed by the question: ‘Which programme do you prefer? (Please tick the appropriate box)’. Figure 1 presents an example of a choice task as included in the questionnaire. The DCE is measured before the start of the intervention and after one year when the intervention has been completed. Data collection for the DCE began in January 2019 and is anticipated to take place until December 2020.

Figure 1.

Example of a choice task used in the discrete choice experiment.

Data analysis for the DCE

To derive the preferences of people with T2DM regarding telemedical lifestyle programmes (ie, relative preference weights for attributes and levels), the obtained baseline DCE data will be analysed using a conditional logit model. Preference weights describe the relative strength of each attribute and level in comparison with all other attributes and levels, respectively. Furthermore, the preference weights will be expressed as time equivalents (willingness to invest time) by calculating the trade-off or marginal rates of substitution between attributes and the attribute that focuses on the time required by the programme. To investigate possible preference heterogeneity, we will conduct a latent class analysis (LCA). The number of classes is determined by the Bayesian information criterion as well as an examination of the interpretation of the latent classes. The following covariates will be incorporated into the LCA: sociodemographic factors (sex, age, employment status and education), disease-related characteristics (HbA1c level, duration of diabetes and BMI), exercise behaviour, depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life. Because the IG and CG are not expected to differ at baseline due to randomisation, the analysis will be based on the full sample.

We will investigate the effect of latent classes of preferences at the beginning of the study on programme success at the end of the study. This will be done by means of an LCA with a distal outcome, where programme success is regressed on latent preference classes. This approach will allow us to explore whether programme preferences differ with respect to distal outcomes such as programme success. This type of analysis may lead to additional information about heterogeneity in the (study) population.

To investigate changes due to participation, preference weights before and after participation in the programme will be compared descriptively and analysed using time equivalents. The analysis will be outlined separately for the IG and the CG as their experiences during the intervention phase will differ substantially.

Sample size calculation for the DCE

As no initial estimates about parameter values in the target population are available, we applied a rule of thumb to determine the sample size instead of a parametric approach. According to de Bekker-Grob et al,53 one frequently used rule of thumb suggests, n>500 c/(t×a) where c is the largest number of levels among attributes, t is the number of choice tasks and a is the number of alternatives per choice task. This was later refined by Orne54 to n>1000 c/(t×a), which resulted in a sample size of n=167 for our design. The recruitment of 850 participants for the RCT will likely lead to a large enough sample that can be stratified for the IG and CG.

Patient and public involvement

Patient involvement during the various stages of the development of the DCE (qualitative interviews, pilot tests) ensured that the research question relied on the actual preferences of people with T2DM participating in telemedical lifestyle programmes.

Ethics and dissemination

The DCE study has been approved by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of the Heinrich Heine University Duesseldorf, registration number 2018-242-ProspDEuA, registered on 6 December 2018. The TeLIPro trial isregistered at the US National Library of Medicine, registration number NCT03675919, registered on 15 September 2018. Patient consent to participate was obtained for the RCT as well as for the DCE. Data analysis will be done according to the principles of good scientific research on DCEs developed by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcome Research (ISPOR). We aim to disseminate our results in peer-reviewed journals, at national and international conferences and to interested patient groups and the public.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the team of the TeLIPro trial: the AOK Rhineland/Hamburg statutory health insurance (leader of the trial consortium), the German Institute for Telemedicine and Health Promotion GmbH (DITG), the Private Institute for Applied Care Research GmbH (inav) and the Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians of North Rhine-Westphalia (cooperation partner). We acknowledge the work of the DITG in programming and implementing the DCE at the online platform. We thank the diabetes care practice Kaltheuner, Schultens-Kaltheuner, Hannig, Marenbach, and their staff from Leverkusen, Germany, for their support. We also thank the volunteers from the self-help group at the German Diabetes Center in Duesseldorf, Germany, and the diabetes care practice in Leverkusen, Germany, for participation in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: MV and AI contributed to the initial grant application. All authors contributed to the design of the study and are involved in the implementation of the project. JS wrote the first draft of the protocol. JS, JD, SG, VG, MV, MR and AI contributed to the drafting and editing of the protocol. All authors read and approved the final protocol.

Funding: This work was supported by the Innovation Fund coordinated by the Innovation Committee of the Federal Joint Committee (funding period 2018–2021) grant number 01NVF17033 under the consortium leadership of the AOK Rhineland/Hamburg.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018;138:271–81. 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Diabetes Federation IDF diabetes atlas. 9th edn Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cradock KA, ÓLaighin G, Finucane FM, et al. Diet behavior change techniques in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1800–10. 10.2337/dc17-0462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greaves CJ, Sheppard KE, Abraham C, et al. Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Public Health 2011;11:119. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim EL, Hollingsworth KG, Aribisala BS, et al. Reversal of type 2 diabetes: normalisation of beta cell function in association with decreased pancreas and liver triacylglycerol. Diabetologia 2011;54:2506–14. 10.1007/s00125-011-2204-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steven S, Taylor R. Restoring normoglycaemia by use of a very low calorie diet in long- and short-duration type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2015;32:1149–55. 10.1111/dme.12722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umpierre D, Ribeiro PAB, Kramer CK, et al. Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2011;305:1790–9. 10.1001/jama.2011.576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association 4. lifestyle management: standards of medical care in Diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care 2018;41:P38–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Diabetes Federation Clinical guidelines task force. global guideline for type 2 diabetes. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paulweber B, Valensi P, Lindström J, et al. A European evidence-based guideline for the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res 2010;42:S3–36. 10.1055/s-0029-1240928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bollyky JB, Bravata D, Yang J, et al. Remote lifestyle coaching plus a connected glucose meter with certified diabetes educator support improves glucose and weight loss for people with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res 2018;2018:1–7. 10.1155/2018/3961730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kempf K, Altpeter B, Berger J, et al. Efficacy of the telemedical lifestyle intervention program TeLiPro in advanced stages of type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2017;40:863–71. 10.2337/dc17-0303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar S, Moseson H, Uppal J, et al. A diabetes mobile APP with In-App coaching from a certified diabetes educator reduces A1c for individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2018;44:226–36. 10.1177/0145721718765650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wayne N, Perez DF, Kaplan DM, et al. Health coaching reduces HbA1c in type 2 diabetic patients from a lower-socioeconomic status community: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e224. 10.2196/jmir.4871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cahn A, Akirov A, Raz I. Digital health technology and diabetes management. J Diabetes 2018;10:10–17. 10.1111/1753-0407.12606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hood M, Wilson R, Corsica J, et al. What do we know about mobile applications for diabetes self-management? A review of reviews. J Behav Med 2016;39:981–94. 10.1007/s10865-016-9765-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunt CW. Technology and diabetes self-management: an integrative review. World J Diabetes 2015;6:225–33. 10.4239/wjd.v6.i2.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, et al. An integrative model of patient-centeredness - a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e107828. 10.1371/journal.pone.0107828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:661–77. 10.2165/00019053-200826080-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mühlbacher A, Johnson FR. Choice experiments to quantify preferences for health and healthcare: state of the practice. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2016;14:253–66. 10.1007/s40258-016-0232-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig BM, Lancsar E, Mühlbacher AC, et al. Health preference research: an overview. Patient 2017;10:507–10. 10.1007/s40271-017-0253-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flood EM, Bell KF, de la Cruz MC, et al. Patient preferences for diabetes treatment attributes and drug classes. Curr Med Res Opin 2017;33:261–8. 10.1080/03007995.2016.1253553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen EM, Longo DR, Bardsley JK, et al. Education and patient preferences for treating type 2 diabetes: a stratified discrete-choice experiment. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017;11:1729–36. 10.2147/PPA.S139471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jendle J, Torffvit O, Ridderstråle M, et al. Willingness to pay for health improvements associated with anti-diabetes treatments for people with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:917–23. 10.1185/03007991003657867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joy SM, Little E, Maruthur NM, et al. Patient preferences for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a scoping review. Pharmacoeconomics 2013;31:877–92. 10.1007/s40273-013-0089-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mühlbacher A, Bethge S. What matters in type 2 diabetes mellitus oral treatment? a discrete choice experiment to evaluate patient preferences. Eur J Health Econ 2016;17:1125–40. 10.1007/s10198-015-0750-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salampessy BH, Veldwijk J, Jantine Schuit A, et al. The predictive value of discrete choice experiments in public health: an exploratory application. Patient 2015;8:521–9. 10.1007/s40271-015-0115-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veldwijk J, Lambooij MS, van Gils PF, et al. Type 2 diabetes patients’ preferences and willingness to pay for lifestyle programs: a discrete choice experiment. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1099. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wanders JOP, Veldwijk J, de Wit GA, et al. The effect of out-of-pocket costs and financial rewards in a discrete choice experiment: an application to lifestyle programs. BMC Public Health 2014;14:870. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swift JK, Callahan JL. The impact of client treatment preferences on outcome: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol 2009;65:368–81. 10.1002/jclp.20553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uebelacker LA, Weinstock LM, Battle CL, et al. Treatment credibility, expectancy, and preference: prediction of treatment engagement and outcome in a randomized clinical trial of hatha yoga vs. health education as adjunct treatments for depression. J Affect Disord 2018;238:111–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delevry D, Le QA. Effect of treatment preference in randomized controlled trials: systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Patient 2019;12:593–609. 10.1007/s40271-019-00379-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwan BM, Dimidjian S, Rizvi SL. Treatment preference, engagement, and clinical improvement in pharmacotherapy versus psychotherapy for depression. Behav Res Ther 2010;48:799–804. 10.1016/j.brat.2010.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le QA, Doctor JN, Zoellner LA, et al. Effects of treatment, choice, and preference on health-related quality-of-life outcomes in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Qual Life Res 2018;27:1555–62. 10.1007/s11136-018-1833-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rigby D, Burton M, Pluske J. Preference stability and choice consistency in discrete choice experiments. Environ Resource Econ 2016;65:441–61. 10.1007/s10640-015-9913-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price J, Dupont D, Adamowicz W. As time goes by: examination of temporal stability across stated preference question formats. Environ Resource Econ 2017;68:643–62. 10.1007/s10640-016-0039-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.San Miguel F, Ryan M, Scott A. Are preferences stable? the case of health care. J Econ Behav Organ 2002;48:1–14. 10.1016/S0167-2681(01)00220-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benning TM, Dellaert BGC, Severens JL, et al. The effect of presenting information about invasive follow-up testing on individuals’ noninvasive colorectal cancer screening participation decision: results from a discrete choice experiment. Value Health 2014;17:578–87. 10.1016/j.jval.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.TeLIPro Aktiv MIT diabetes, 2019. Available: https://www.telipro-aok.de/ [Accessed Dec 2019].

- 40.Jan S, Usherwood T, Brien JA, et al. What determines adherence to treatment in cardiovascular disease prevention? protocol for a mixed methods preference study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000372. 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker RC, Morton RL, Tong A, et al. Patient and caregiver preferences for home dialysis-the home first study: a protocol for qualitative interviews and discrete choice experiments. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007405. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spinks J, Chaboyer W, Bucknall T, et al. Patient and nurse preferences for nurse handover-using preferences to inform policy: a discrete choice experiment protocol. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008941. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong SF, Norman R, Dunning TL, et al. A protocol for a discrete choice experiment: understanding preferences of patients with cancer towards their cancer care across metropolitan and rural regions in Australia. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006661. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quaife M, Eakle R, Cabrera M, et al. Preferences for ARV-based HIV prevention methods among men and women, adolescent girls and female sex workers in Gauteng Province, South Africa: a protocol for a discrete choice experiment. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010682. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janssen EM, Segal JB, Bridges JFP. A framework for instrument development of a choice experiment: an application to type 2 diabetes. Patient 2016;9:465–79. 10.1007/s40271-016-0170-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janssen EM, Bridges JFP. Art and science of instrument development for Stated-Preference methods. Patient 2017;10:377–9. 10.1007/s40271-017-0261-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janssen EM, Hauber AB, Bridges JFP. Conducting a discrete-choice experiment study following recommendations for good research practices: an application for eliciting patient preferences for diabetes treatments. Value Health 2018;21:59–68. 10.1016/j.jval.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuhfeld WF. Marketing research methods in SAS: experimental design, choice, conjoint, and graphical techniques. SAS document TS-694. Available: http://support.sas.com/techsup/tech_note/ts694.pdf [Accessed 2 Mar 2007].

- 49.Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, et al. Cross-Validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 health survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA project. International quality of life assessment. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1171–8. 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00109-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hautzinger M, Bailer M. Allgemeine depressionsskala (ADS). Weinheim, Germany: Beltz, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 1985;29:71–83. 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Armstrong T, Bull F. Development of the world Health organization global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ). J Public Health 2006;14:66–70. 10.1007/s10389-006-0024-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Jonker MF, et al. Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: a practical guide. Patient 2015;8:373–84. 10.1007/s40271-015-0118-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orme B. Getting started with conjoint analysis: strategies for product design and pricing research. 2nd edn Madison: Research Publishers LLC, 2010: 64. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-036995supp001.pdf (131.2KB, pdf)