To the Editor: Increasing evidence supports a causal relationship between severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and cutaneous manifestations.1 , 2 However, interpretation of SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR)/antibody results in dermatology patients with probable coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection remains difficult because of lack of data to inform optimal test timing.

Our international registry for cutaneous manifestations of COVID-191 , 3 asked providers to report time between dermatologic symptom onset and positive or negative COVID-19 laboratory results. From April 8 to June 30, 2020, 906 laboratory-confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases with dermatologic manifestations were reported, 534 of which were chilblains or pernio. Among PCR-tested patients, 57% (n = 208) of overall cases and 15% (n = 23) of chilblains and pernio ones were PCR positive. Antibody positivity was 37% (n = 39) overall and 19% (n = 15) for chilblains and pernio.

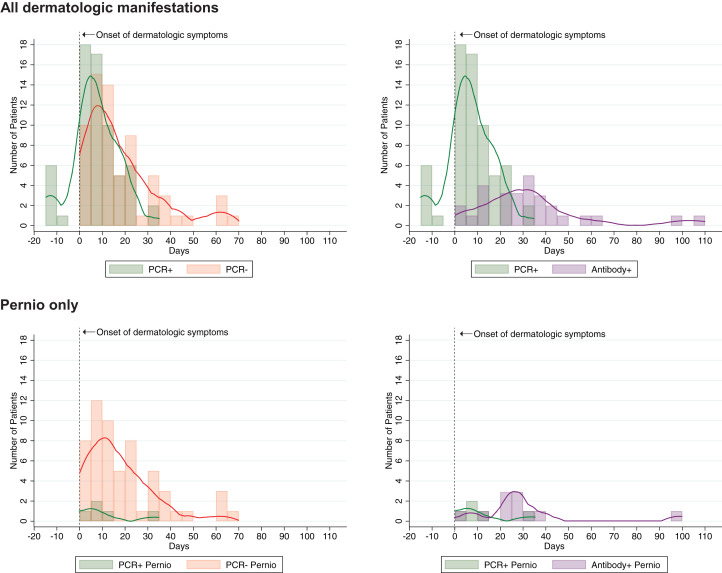

We evaluated the subgroup of 163 patients (representing the full spectrum of dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19)1 with information on timing of PCR testing, antibody testing, or both (Table I , Supplemental Table I [available via Mendeley at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/yhc38v2fk9/1]). For patients with suspected COVID-19 and any cutaneous manifestation, PCR positivity occurred a median of 6 days (interquartile range [IQR] 1-14 days) after dermatologic symptoms started, whereas PCR negativity occurred a median of 14 days later (IQR 7-24 days) (Fig 1 ). For patients with pernio or chilblains, PCR positivity was noted 8 days (IQR 5-14 days) after symptoms and negativity a median of 14 days later (IQR 7-28 days) (Supplemental Fig 1). Antibody testing result (immunoglobulin M or IgG) was positive a median of 30 days (IQR 19-39 days) after symptom onset for all dermatologic manifestations and 27 days (IQR 24-33 days) after chilblains or pernio.

Table I.

Distribution and timing of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 polymerase chain reaction and coronavirus disease 2019 antibody test results in relation to dermatologic manifestations

| Testing characteristic | Chilblains/pernio |

Nonchilblains/pernio |

All dermatologic conditions, including pernio and nonpernio |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of pernio patients | No. of pernio patients with timing data | Pernio onset to testing interval, median (IQR), days | No. of nonpernio patients | No. of nonpernio patients with timing data | Nonpernio dermatologic symptom onset to testing interval, median (IQR), days | No. of patients | No. of patients with timing data | Dermatologic symptom onset to testing interval, median (IQR), days | |

| PCR testing | |||||||||

| PCR+ | 23 | 5 | 8 (5–14) | 185 | 62 | 6 (1–15) | 208 | 67 | 6 (1–14) |

| PCR– | 134 | 58 | 14 (7–28) | 27 | 10 | 9 (5–13) | 161 | 68 | 14 (7–24) |

| SARS-CoV-2–positive antibody testing | |||||||||

| IgM+/IgG+ | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| IgM+/IgG– | 7 | 7 | 24 (23–28) | — | — | — | 7 | 7 | 24 (23–28) |

| IgM–/IgG+ | 1 | 1 | 99 | 5 | 5 | 31 (14–32) | 6 | 6 | 32 (14–35) |

| IgM unknown/IgG+ | 3 | 3 | 35 (25–40) | 10 | 7 | 38 (14–46) | 12 | 10 | 37 (25–40) |

| Ig+ (isotype unknown) | 1 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 60 (30–107) | 5 | 4 | 45 (20–84) |

| SARS-CoV-2–negative antibody testing | |||||||||

| IgM–/IgG– | 17 | 5 | 37 (21–42) | 1 | — | — | 18 | 5 | 37 (21–42) |

| IgM unknown/IgG– | 35 | 16 | 38 (33–50) | 2 | 2 | 14 (0–27) | 37 | 18 | 36 (28–49) |

| Ig- (isotype unknown) | 11 | 6 | 34 (21–60) | — | — | — | 11 | 6 | 34 (21–60) |

IgM, Immunoglobulin M; IQR, interquartile range; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; +, positive; –, negative; —, no cases reported.

Fig 1.

Distribution of positive and negative coronavirus disease 2019 test results in relation to onset of dermatologic symptoms, including polymerase chain reaction–positive/negative test results and polymerase chain reaction–positive/antibody-positive test results. Individual cases graphed as 5-day bins, defined by date of laboratory testing. PCR, Polymerase chain reaction.

PCR test results earlier in the disease course were more likely to be positive, even when date of onset was defined by cutaneous manifestations rather than systemic symptoms. Positive predictive values for COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab PCR are influenced by kinetics of nasopharyngeal shedding, which are difficult to assess in nonrespiratory presentations.4 This study highlights the low frequency of SARS-CoV-2 PCR-positive testing in COVID-19 patients with cutaneous manifestations.

Most published COVID-19 antibody data reflect systemically ill patients; kinetics of antibody production in mild to moderate COVID-19 infections remain unclear.5 We detected positive antibodies a median of 30 days from disease onset, beyond the typical 14- to 21-day testing window. In outpatients with true infection, many factors influence the likelihood of positive antibody results: antibody production, assay sensitivity, and timing of care seeking. These variables influence interpretation of individual test results and understanding of the association between skin findings and COVID-19. Repeated serosurveys are needed to identify optimal antibody testing windows.

We acknowledge limitations inherent to a provider-reported registry. There is selection bias because providers likely preferentially entered laboratory-confirmed cases. Test timing could be influenced by type of symptoms (patients with systemic symptoms might have been tested earlier than those with skin-only manifestations), inpatient versus outpatient care, and geographic location. We relied on providers' judgment that the dermatologic manifestation was related to COVID-19, so the laboratory-result-negative group may have included patients without SARS-CoV2 infection. Complicating the interpretation of negative test results are reports of PCR/antibody-negative patients whose skin biopsies contain detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA (Supplemental references).

More population-level testing data are needed to fully understand the expected timing between disease symptoms and test positivity or negativity. Positive identification of COVID-19 in minimally symptomatic patients, including patients with skin findings, remains critical to the public health effort.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: Drs Freeman, Hruza, Lipoff, and Fox are part of the American Academy of Dermatology COVID-19 Ad Hoc Task Force. Dr French is the President of the International League of Dermatologic Societies. Dr Freeman is an author of COVID-19 dermatology for UpToDate. Dr Fassett and Author McMahon have no conflicts of interest to declare.

IRB approval status: The registry was reviewed by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board and was determined not to meet the definition of Human Subjects Research.

Reprints not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Freeman E.E., McMahon D.E., Lipoff J.B., et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hubiche T, Le Duff F, Chiaverini C, Giordanengo V, Passeron T. Negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR in patients with chilblain-like lesions. Lancet Infect Dis. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30518-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Freeman E.E., McMahon D.E., Fitzgerald M.E., et al. The AAD COVID-19 Registry: crowdsourcing dermatology in the age of COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):509–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sethuraman N., Jeremiah S.S., Ryo A. Interpreting diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2249–2251. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbiani D.F., Gaebler C., Muecksch F., et al. Convergent antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent individuals. Nature. 2020;584(7821):437–442. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]