Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Professionalism and medical ethics are a vital quality for doctors, which has been taken into account seriously in recent years. Perception of the factors affecting professionalism may help develop more efficient approaches to promote this quality in medical education. This study was aimed to explain the role of hidden curriculum in the formation of professional ethics in Iranian medical students.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This qualitative study was performed on 15 medical interns of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences in 2019, using grounded theory. Sampling was started by purposive sampling and continued through theoretical sampling until complete data saturation. Data collection and analysis were done simultaneously. Data were interpreted by a constant comparative method according to Strauss and Corbin's approach.

RESULTS:

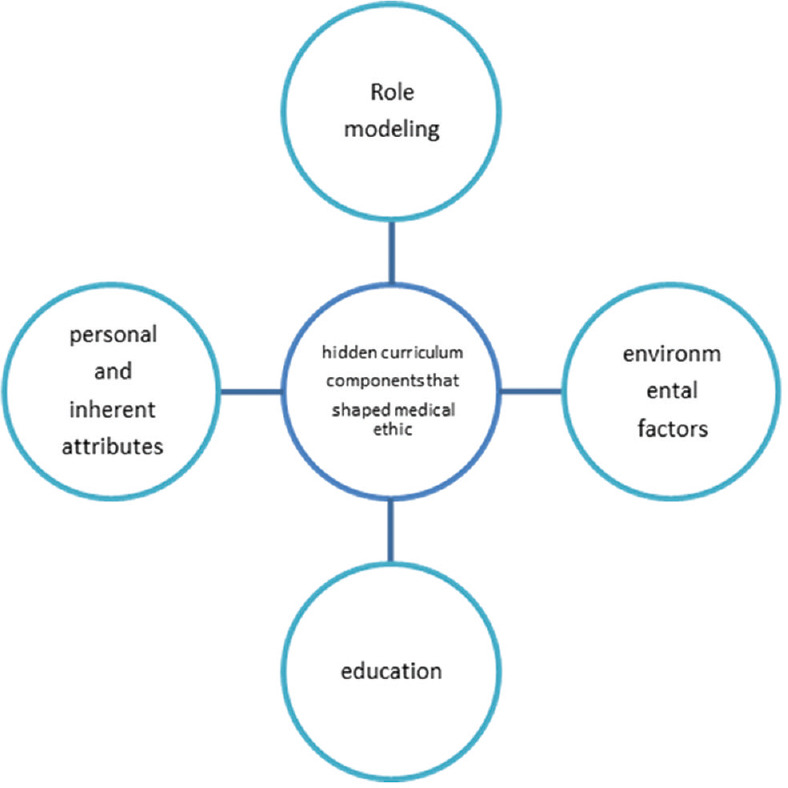

The analysis of the participants’ interviews and reduction of findings using common themes yielded one class and four categories as well as a number of concepts as the role of hidden curriculum in the formation of professional ethics in medical students. The categories included the role of modeling in the formation of professional ethics, role of education in the formation of professional ethics, role of environmental factors in the formation of professional ethics, and role of personal and inherent attributes in the formation of professional ethics.

CONCLUSION:

Curriculum developers and medical education authorities need to proceed in line with the findings of the present study to provide a proper learning environment, in which the modeling, learning, and teaching conditions and supportive environmental atmosphere are taken into account in accordance with the inherent and individual characteristics of the learners in order to guarantee the formation of professional ethics in medical students.

Keywords: Curriculum, medical education, professional ethics, professionalism

Introduction

Professionalism and medical ethics are a vital quality for the doctors, which has been seriously taken into consideration in recent years. Understanding the factors affecting professionalism may help to develop more effective approaches to promote this quality in medical education.[1] Ethics and professionalism are commonly used synonymously in medical education settings. However, there is a narrow difference between these two concepts. That means acting is not ethical unless you are a professional, but having a profession will have no guarantee of ethics.[2] The purposes of formation of medical ethics during the teaching process in the students include creating a professional identity, handling the diversity of religious and existential worldviews, teaching the ethical principles to students, processing difficult clinical experiences, eliminating negative role modeling in doctors in the clinical or training settings, and modifying students’ political attitudes.[3]

Although development of professional ethics among students is one of the responsibilities of medical education,[1] researchers recommend putting students in the situations of simulated but realistic moral dilemma and uses cooperative learning strategies in teaching, including real-life stories, illustrations, and role-playing games,[4] and additional strategies that support social development of students including mobile learning, cooperative learning, and other forms of peer-mediated instruction.[5,6,7] Studies have shown that the teaching method employed to teach professional ethics to the medical students is lecturing, and the learning assessment method is paper-based examination run at the end of the term, and that there is no specific standard for teaching professional ethics.[8] Despite the fact that medical ethics and professionalism are taught to medical students, they perform unethical behaviors, so it is necessary to modify the method used for teaching professional ethics.[9] This process indicates that teaching professional ethics is not ideal. Therefore, it is urgent to prepare and modify the curriculum of professional ethics and include it in the educational content in order to promote the capabilities of the teachers in nurturing professional ethics in the students.[10]

The major values in the medical sciences that are necessary for a doctor are located in the realm of medical professionalism. Professionalism along with other human skills is implicitly considered the components of hidden curriculum in the medical faculties. Evidence shows a strong bond between the hidden curriculum and development of professionalism.[11,12] The term “hidden curriculum” was first defined by Philip Jackson in 1968 to describe the attitudes and beliefs children should learn as a part of socialization to succeed at school, and Hafferty was the first to adopt this concept to the medical domain in 1994. Studies have indicated that doctors not only receive the hidden curriculum but also voluntarily protect the ethical values in their working conditions in accordance with their perception of values.[1] Jerald (2006) reported that hidden curriculum is an implicit curriculum that is indicative of the attitude, knowledge, and behavior that are delivered indirectly and unconsciously by words and practices that constitute parts of the life of everyone in the society.[13] The hidden curriculum involves the unspoken cultural and social knowledge students acquire in the learning environment.[5] Studies have mainly reported the negative effects of the hidden curriculum. Some communicative aspects attributed to the hidden curriculum are related to the informal curriculum. Hidden curriculum in medical education is a subject that has been disregarded to a large extent. It seems that a concept more comprehensive than what was theorized by Hafferty often involves informal curriculum, too. In addition, studies have shown the negative outcomes of hidden curriculum, such as the problem of transfer of professional values and ethics. Future researchers need to concentrate on the positive outcomes as a strategy to compensate for the lost professional ethics.[14]

Hidden curriculum plays a main role in professional learning, formation of professional identity, socialization, moral development and learning values, attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge in learners, so it needs to be managed.[15,16] Blasco believes that beside the formal curriculum, interpersonal interactions and the school governance also send messages to learners that could be sometimes contrary to the intended goals. Blasco argues that if these three factors are controlled, the negative effects of the hidden curriculum can be reduced.[17]

Hidden curriculum is not only a set of unique educational gatherings, but also a systematic educational method that accompanies us every time, everywhere, and in anything we do. Finally, it can be argued that hidden curriculum has a significant impact on the positive and negative ethical values of students. Hence, teachers have to recognize how they act in education. When teachers do not fully understand the meaning of hidden curriculum, they may exert negative effects on their students. On the other hand, if they know the role of hidden curriculum, they can have a positive effect in the classroom. Teachers can influence the students’ behavior, belief, experience, skill, and knowledge through their hidden curriculum in order to help them by various methods such as personal and scientific methods.[8]

Studies have shown that personal factors such as personal and interpersonal characteristics and environmental factors such as organizational culture and formal and informal curricula play a role in developing the professional ethics of the doctors. Accordingly, institutions should consider these factors and make an attempt to promote these elements.[1] In some studies, students reported that they were under the influence of their friends and family members in learning medical ethics, and most of them believed that medical television programs that presented the strategies of medical ethics in cooperation with students were useful for teaching medical ethics.[18] Further, personal factors such as self-efficacy and moral competence are helpful for students’ professional development, and cooperation with the members of the treatment team improves their clinical competence and performance.[19]

Academic environments, faculty workload, and teaching responsibility also affect the teaching of medical ethics. Conventionally, regular communication between medical students and teachers is expected to occur spontaneously, which provides the training needs and medical ethics of the medical students. However, more accurate monitoring and evaluation methods are needed for teaching professional ethics, and ethical content should be included in the curriculum.[20] In a review in English-speaking countries, mainly in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia, on the weak and strong points of the methods and ethical content of medical education, the following three major challenges were identified: adverse effects of hidden curriculum, teaching ethics in clinical practice, and development of a correct personality in the future doctors.[21]

Some studies have emphasized the effectiveness of indirect teaching of medical ethics. In a study, medical students reported that they often faced ethical conflicts during education, against which education has been partly helpful but inadequate. Students highlighted the importance of teaching ethics using positive role models, confirmed the clinical methods as preferred learning methods, and emphasized the direct monitoring of the faculty.[22] This education is effective when it is included in the formal curriculum of the faculties.[23] Although we can teach professional ethics formally in the class and informally in small groups, standardization of the professional ethics curriculum is a burdensome task due to unique professional experiences and interactions.[24]

Despite the development of standards, turning points, and competencies related to professionalism, studies have shown no consensus on the specific objectives of medical ethics, knowledge, and basic skills expected by students and the best educational methods and processes for the implementation of optimal strategies. Although it may be appropriate to modify the teaching and assessment methods, teaching medical ethics should eventually fulfill the expressed principled expectations.[25] Role modeling is a significant activity for students in clinical education environments. The clinical teachers’ knowledge of their professional features, attitudes, and behaviors can help to create better learning experiences.[26] Role modeling is a crucial component of clinical training that encourages students to observe and reflect on the benefits and drawbacks of their preceptors’ behaviors and emulate those which they feel are important, and role modeling is similarly essential for students’ professional development. However, if role modeling refers to a conscious or unconscious unselective imitation of a role model's behaviors and/or to an uncritical conformity with the formal (institutional culture) and unacknowledged (hidden curriculum) messages of the learning environment, then its benefits should be weighed against its unintended harm.[27] As it is important to study medical ethics, the present study aimed to explain the role of hidden curriculum in the formation of professional ethics in the students of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences.

Materials and Methods

The study was performed using grounded theory method. Grounded theory is a well-known methodology employed in many research studies. Grounded theory sets out to discover or construct theory from data, systematically obtained and analyzed using comparative analysis.[28] This qualitative study was conducted on all medical interns of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. The approach of this study was inductive. The sample selection was initiated by purposive sampling and continued by theoretical sampling until complete data saturation. The purposeful sampling is a technique widely used in qualitative research for the identification and selection of information-rich cases for the most effective use of limited resources. This involves identifying and selecting individuals or groups of individuals that are especially knowledgeable about or experienced with a phenomenon of interest.[29] The study sample included 15 final-year medical interns (8 females and 7 males). The mean age of the participants was[24] 27 ± 1.27 years. Nine of them were nonnative and six of them were native. Further, ten of them were single and five of them were married. Data were collected by semi-structured interviews. Prior to the interview, each participant was contacted by telephone, and in a separate face-to-face meeting, participants’ satisfaction and intimacy were established. Researchers were provided with necessary explanations for the purpose and explained that they could be aware of the results of this study. Interviews were conducted at Imam Reza, Mohammad Kermanshahi, Farabi Hospitals, and Kermanshah Medical Schools. The average duration of each interview was 70 min (minimum 55 and maximum 90 min).

Data collection and analyses were done concurrently. Interviews were started with simple and general questions and continued with more detailed questions. All interviews were recorded and noted down concurrently and confirmed by the participants. The data obtained from each interview were transcribed to be coded and interpreted by a constant comparative method according to Strauss and Corbin's approach. Strauss and Corbin, inspired by pragmatic thinkers, believe that there are multiple facts and that the outside world is a symbolic representation. Currently, this approach is used as a theoretical framework in qualitative research.[30] After each interview, the tapes were transcribed, read line by line, and coded using the keywords or phrases from the transcripts or inferred by the researcher. Three stages of open, axial, and selective coding were done on the data. During the study, different methods were applied to ensure the accuracy and reliability of data. An attempt was also made to gain the trust of the participants and add to the perception of the research environment by long-term communication and contact with the research locations. Three persons coded the data to ascertain the accuracy and objectivity of the data and codes. After coding, the transcripts were returned to some participants to confirm the accuracy of the extracted codes and interpretations.

Results

The study sample included 15 final-year medical interns (8 females and 7 males). The mean age of the participants was 25.27 ± 1.27 years. Nine of them were nonnative and six of them were native. Further, ten of them were single and five of them were married. The data obtained from the interviews were promoted to more abstract levels following detailed analyses and constant comparisons based on meaning similarities and were finally included in general classes. According to what the participants stated, each of these classes was described and adapted to the literature of the subject concurrently. The primary codes were gathered in a collection depending on their congruity and research question and were given a conceptual label. The concepts were then allocated to categories based on the message they contained. Each of these concepts had their special meaning and was differentiated from one another by the concepts it supported. The categories also constituted the classes. The researcher classified the categories into four classes based on the role of hidden curriculum in the formation of professional ethics. In fact, there is an inductive process in this classification which moves from the raw data to the concepts, categories, and abstract classes and normally emerges from the platform of data.

Based on the analysis of the participants’ interviews and reduction of results using the common concepts, four categories were obtained as the roles of hidden curriculum in the formation of professional ethics in the medical students, which are presented below.

Role of modeling in the formation of professional ethics: The participants stated that they learned professional ethics from their teachers, doctors, classmates, family members, society, and relatives. Some instances of participants’ remarks included: “I have emulated the doctors I am friend with outside the hospital not in the hospital (code 102),” “My parents have played a role in my lifestyle (code 1o7),” “The teachers’ morality and behaviors are instilled in my mind and are considered a model for me (code 110),” “My first model is my uncle and then my brothers (code 111),” “I have learned medical ethics from my teacher's behavior, some teachers’ behaviors had a great impact on me and they were good models for me (code 115),” “The morality of classmates definitely influences us. I have lived in the dormitory and have experienced this. My friends’ morality affects me (code 112)”

Role of education in the formation of professional ethics: This category included concepts such as direct ethical education; training by a well-known and popular person and individuals with scientific and experimental background; training via workshops, conferences, and in practice, observational education, and concurrency of words and action. Some examples were: “If a bad-tempered and impatient person gives me ethical advice, it will not certainly influence me (code 104),” “If popular teachers teach, students will learn better (code 114),” “Running educational workshops by the role model teachers (101),” “In an environment in which the patient is insulted or bribery and favoritism are prevalent, I cannot resist and will be influenced. Even many of my friends said they visited the patients for free but they annoyed them (code 103),” “He/she should be a well-known and approved person. He/she should be really considerate and have good behaviors, he/she should not insult the patients and their companions (code 106),” and “I think conference and workshop can be effective (code 108)”

Role of environmental factors in the formation of professional ethics: This category involved concepts such as managers’ expectations, coercion, culture, atmosphere, social approval, organizational factors, law and regulations, ethnic prejudices, and interactive effect of behavior in the ward. Some examples of participants’ opinions were: “environment has a great impact on the formation of ethics (code 109),” “I believe for a doctor family has little role in the formation of professional ethics and university has a greater impact. All criticisms are targeted at the educational environment (code 113),” “Hospital and university environments should be model environments (code 105),” “and Ninety percent of the behaviors are formed before university. The curriculum has not much to influence the students (code 105)”

Role of personal and inherent attributes in the formation of professional ethics: This category consisted of concepts such as religious beliefs, sense of commitment, intrinsic professional ethics, role of family origin, human will, and adherence to ethics. Some instances of the participants’ remarks included: “I believe if a human has a pure nature (101),” “Many ethical attributes exist in a person's nature or family (code 115),” “A person who takes care of a patient has definitely a series of restraints that are related to his/her personal beliefs and commitment (code 107),” “I think one part of it is inherent, i.e., a person has grown with a series of beliefs (code 113),” “Ethics is inherent, i.e., a tree that is growing has roots, if you cut its branches and leaves, they grow again, if you pick up its fruits, it yields fruits again (code 108),” “You cannot convert an apple tree into an orange tree. You cannot change someone's nature (105),” “The main issue is childhood rather than adolescence or youth, during which a person's personality is formed. If it is formed well, that's great, but if it is formed poorly, it will not be possible to form the personality again or guide the person (code 111).” These results are presented in Table 1 as classes, categories, and main concepts derived from the axial coding. All findings as professional lessons learned by students from the hidden curriculum are presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Classes, categories, and major concepts related to the role of hidden curriculum in the formation of professional ethics

| Class | Categories | Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Role of hidden curriculum in the formation of professional ethics in the medical students | Role of modeling in the formation of professional ethics | Emulating the doctors outside the hospital, emulating the teachers, learning professional ethics due to improper behavior of other doctors, effect of classmates on observing professional ethics, observability of professional ethics (it is taught through behavior), family as the main factor and guarantee of professional ethics, learning professional ethics from the relatives, learning professional ethics from the society and family (something out of formal curriculum), teaching medical ethics by a person who is an agent, concurrency of words and action in teaching professional ethics, presenting professional ethics by popular and well-known teachers |

| Role of education in the formation of professional ethics | Learning professional ethics in the classroom, effect of experience on professional ethics (self-control), learning medical ethics from the residents, role of direct education in the promotion of professional ethics, concurrent effect of ethics and knowledge, role of preaching in professional ethics, effect of educational conditions and university on the formation of professional ethics, efficacy of teaching ethical content with scientific support, efficacy of teaching ethical content with experimental support, efficacy of the recommendations of teachers responsible for ethical values in role-playing, efficacy of teaching professional ethics via conference and workshop, creating conditions for observing patients with acute conditions (physical, economic, etc.), reinforcing learning via on-the-job training, guiding the students toward motivation and goals to guarantee ethics, caring for the students to develop professional ethics | |

| Role of environmental factors | Effect of environment on professional ethics, effect of authorities’ expectations on observing professional ethics, effect of coercion on observing professional ethics, effect of culture on professional ethics, effect of atmosphere on professional ethics, social approval as a factor for observing professional ethics, role of organizational factors in professional ethics, role of law and regulations in professional ethics, role of ethnic biases in professional ethics, effect of culture on professional ethics, interactive effect of behavior in the wards | |

| Role of personal and inherent attributes | Effect of religious beliefs, sense of commitment to the profession and patients, belief in the pure nature of human and observing all ethical values, naturalness of professional ethics, naturalness of the sense of philanthropy, role of family origin in commitment to professional ethics, effect of human will on the modification of professional ethics, maintaining a doctor’s dignity to guarantee professional ethics, nonlimitation of ethical commitment to religious beliefs |

Figure 1.

Professional lessons learned by students from the hidden curriculum

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of hidden curriculum in the formation of professional ethics among medical students of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. The results showed that the following four factors are involved in the formation of professional ethics: the role of modeling in the formation of professional ethics, the role of education in the formation of professional ethics, the role of environmental factors, and the role of personal and intrinsic attributes. The findings showed that professional ethics was influenced by the hidden curriculum. Ethical modeling was a factor affecting hidden curriculum in this study. That is students learned part of medical professional ethics through modeling. In line with this finding, previous studies have reported the role of positive ethical roles in the formation of professional ethics in students.[19] Role modeling is a crucial component of clinical training that encourages students to observe and reflect on the benefits and drawbacks of their preceptors’ behaviors and emulate those which they feel are important, and role modeling is similarly essential for students’ professional development. However, if role modeling refers to a conscious or unconscious unselective imitation of a role model's behaviors and/or to an uncritical conformity with the unacknowledged (hidden curriculum) messages of the learning environment, its benefits should be weighed against its unintended harm.[23] Although role modeling is important for students in clinical education environments, this method has been unsuccessful in positive ethical learning and is not considered the professional behavior modeling due to stereotypical roles and teachers’ pretense nature to be models.[24] It seems that students perceive teachers’ behaviors differently as they differentiate the real behavior from stereotypical behavior and pretended ethical behavior. These studies have shown that the teachers themselves should follow the ethical values and be reputed in the society. Given the effective role of modeling education, it is suggested that this approach be used in ethics education. Role modeling is not a single method in this study. Rather, it is taught as an educational approach involving a set of methods such as role playing, modeling, and observing behavior consciously or unconsciously in the form of a hidden curriculum.

The results of this study showed that teaching and learning affect medical professional ethics and professional ethics has to be taught directly in the classroom using different methods. These methods include conference, workshop, patient observation, and on-the-job training. In line with the results of this study, some studies have highlighted the effectiveness of direct teaching of medical ethics and have emphasized ethical education through clinical methods as the preferred learning method under direct monitoring of the faculty; however, they have considered it inadequate.[19] Therefore, more accurate monitoring and assessment methods are required to teach professional ethics, and ethical content should be included in the curriculum.[31] Moreover, the effects of hidden curriculum on the content of ethical education in clinical practice to form the correct personality of future doctors should not be disregarded.[18] Yet, this education is effective when it is included in the formal curriculum of the faculties.[19,32] Some claim that standardization of the professional ethics curriculum is a difficult task because of unique professional experiences and interactions.[21] In a study, the medial students reported that they often encountered ethical conflicts during schooling, against which education was helpful to some extent, but it was sufficient.[19] Another study considered medical television programs that presented the strategies of medical ethics in cooperation with students to be useful for teaching medical ethics.[32] The findings of this study and previous studies show that although some direct teaching methods partly affect the students’ learning of professional ethics, a major part of learning is related to the unplanned lessons which are located in the framework of hidden curriculum. Hence, curriculum developers and teachers need to pay attention to the other factors found in the present study in addition to planning and setting goals for the development of professional ethics in students. According to the findings of this study, it seems that although direct teaching of ethical issues to students is not very effective, exposing students to ethical issues is not without effect. This is the same process as the hidden curriculum. The difference between the results of this study and previous studies is that in previous studies, indirect methods in teaching ethics have been used.[9,10,23] However, the results of this study suggest that although direct education is less effective, exposing students to ethical training alongside other environmental stimuli in the form of a hidden curriculum can be effective in shaping professional ethics.

One of the findings of this study was the role of the environment in medical ethics. These factors included authorities’ expectations, culture, environment, social approval, organizational factors, law and regulations, ethnic biases, and interactive effect of behavior in the wards. Studies have indicated that environmental factors such as organizational culture play a role in the professional ethics of doctors.[1,30] In a study, students reported that they were influenced by their friends and family members while learning medical ethics.[14] Moreover, academic environments, faculty workload, and teaching responsibilities influence medical ethics.[31] An issue that did not appear in previous studies and appears to be related to the social culture of individuals was the issue of social confirmation, the ethnic bias that results from this study. These seem to be related to the culture of Iranian society, especially among the people of Kermanshah. Accordingly, institutions need to consider these factors and try to promote these elements.

Furthermore, the results showed the role of personal and inherent attributes in the formation of professional ethics in doctors. These attributes consisted of the effect of religious beliefs, sense of commitment to the profession and patients, belief in the pure nature of human, naturalness of professional ethics, role of family origin, and effect of human will. In line with this study, some studies have considered some personal factors such as students’ self-efficacy and ethical competence as effective for their professional development and determination for cooperation with the treatment team to improve their clinical competence and performance.[32] Further, forming correct personality in the future doctors has been taken as one of the methods to accomplish medical ethics.[31] Studies have indicated that personal and interpersonal factors are involved in doctors’ professional ethics.[1] Factors in and adherence to religious beliefs, belief in the pure nature of human, and the role of the family can be attributes of religious communities that are common in the Iranian society.[30] Belief in the naturalness of medical ethics was a different result obtained in the present study. According to some beliefs of Iranians, which are originated from the literature and culture of this region, good and evil are part of human nature and intertwined with the religious beliefs, giving them a special sanctity. If we believe that human is born with good or evil, belief in the effect of educational interventions is diminished. Although these beliefs are not backed up scientifically, they are influential.

Conventionally, it is expected that ongoing communications between medical students and their teachers occur spontaneously and fulfill the pedagogical and ethical requirements of medical students,[33] but this is not true in practice. In line with the findings of the present study, curriculum developers and medical education authorities should proceed to provide appropriate learning environments in which modeling, teaching, and learning conditions and supportive atmosphere are considered in accordance with the personal and inherent attributes of learners in order to guarantee the formation of professional ethics in medical students.

It may not be possible to change people's personal and intrinsic characteristics, but it is possible to train educators with acceptable moral characteristics in creating an educational model, and also by providing a favorable educational and clinical environment in which the existing barriers to professional ethics are removed. In addition, in teaching professional ethics, appropriate teaching–learning methods to provide the ground for creating the dignity of professional ethics can be used.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that hidden curriculum is involved in the formation of professional ethics. The influential factors included modeling, teaching, and learning; environmental factors; and inherent attributes of individuals. These factors can be a good guide to achieving the goals of professional ethics in physician training and education programs. Hence, curriculum developers and medical education authorities are recommended to include these components in the medical ethics curriculum in order to ensure the formation of professional ethics in medical students. It is, therefore, recommended that curriculum planners, education policymakers, and teachers plan and implement a professional ethics curriculum in light of these factors.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education, Tehran, Iran with ethical approval number 950036. During the research, it was attempted to ensure the confidentiality and freedom of the participants to participate in the research or exit must be observed. I thank the undergraduate medical students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences for collaborating with the researchers.

References

- 1.Hafferty FW, O’ Donnell JW. The hidden curriculum in health professional education. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press; 2014. ISBN: 978-1-61168-659-6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn M. On the relationship between medical ethics and medical professionalism. J Med Ethics. 2016;42:625–6. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thulesius HO, Sallin K, Lynoe N, Löfmark R. Proximity morality in medical school-medical students forming physician morality “on the job”: Grounded theory analysis of a student survey. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maxwell B, Schwimmer M. Professional ethics education for future teachers: A narrative review of the scholarly writings. J Moral Educ. 2016;45:354–71. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sulaimani MF, Gut DM. Hidden curriculum in a special education context: The case of individuals with autism. J Educ Res Pract. 2019;9:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safari Y, Meskini H. The Effect of Metacognitive Instruction on Problem Solving Skills in Iranian Students of Health Sciences. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8:150–6. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n1p150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safari Y, Afzali B, Ghasemi S, Sharafi K, Safari M. Comparing the effect of short message service (SMS) and pamphlet instruction methods on women's knowledge, attitude and practice about breast cancer (2014) Acta Med Mediterranea. 2016;32:1927–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkabba AF, Hussein GM, Kasule OH, Jarallah J, Alrukban M, Alrashid A. Teaching and evaluation methods of medical ethics in the Saudi public medical colleges: Cross-sectional questionnaire study. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:122. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadav H, Jegasothy R, Ramakrishnappa S, Mohanraj J, Senan P. Unethical behavior and professionalism among medical students in a private medical university in Malaysia. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:218. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1662-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safari Y, Yoosefpour N. Dataset for assessing the professional ethics of teaching by medical teachers from the perspective of students in Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Iran (2017) Data Brief. 2018;20:1955–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2018.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozolins I, Hall H, Peterson R, Ozolins I, Hall H, Peterson R. The student voice: Recognising the hidden and informal curriculum in medicine. Med Teach. 2008;30:606–11. doi: 10.1080/01421590801949933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar Gh S, Kumar A. Building professionalism in human dissection room as a component of hidden curriculum delivery: A systematic review of good practices. Anat Sci Educ. 2019;12:210–221. doi: 10.1002/ase.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alsubaie MA. Hidden curriculum as one of current issue of curriculum. J Educ Pract. 2015;6:125–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raso A, Marchetti A, D'Angelo D, Albanesi B, Garrino L, Dimonte V, et al. The hidden curriculum in nursing education: A scoping study. Med Educ. 2019;53:989–1002. doi: 10.1111/medu.13911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbasi M, Khalajinia Z, Abbasinia M, Shojaei S, Nasiri M. Explaining the experiences of nurses about barriers of religious care in hospitalized patients: A qualitative study. Health, Spirit Med Ethics J. 2018;5:36–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ludmerer KM. Time to heal: American medical education from the turn of the century to the era of managed care. New York, NY: Oxford Univ Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blasco M. Aligning the hidden curriculum of management education with PRME: An inquiry-based framework. J Manag Educ. 2012;36:364–88. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giubilini A, Milnes S, Savulescu J. The Medical Ethics Curriculum in Medical Schools: Present and Future. J Clin Ethics. 2016;27:129–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.AlMahmoud T, Hashim MJ, Elzubeir MA, Branicki F. Ethics teaching in a medical education environment: Preferences for diversity of learning and assessment methods. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:13282571–9. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2017.1328257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollins LL, Wolf M, Mercer B, Arora KS. Feasibility of an ethics and professionalism curriculum for faculty in obstetrics and gynecology: A pilot study. J Med Ethics. 2019;45:806–10. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2018-105189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly AM, Mullan PB. Designing a curriculum for professionalism and ethics within radiology: Identifying challenges and expectations. Acad Radiol. 2018;25:610–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrese JA, Malek J, Watson K, Lehmann LS, Green MJ, McCullough LB, et al. The essential role of medical ethics education in achieving professionalism: The Romanell Report. Acad Med. 2015;90:744–52. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayasuriya-Illesinghe V, Nazeer I, Athauda L, Perera J. Role Models and Teachers: Medical students perception of teaching-learning methods in clinical settings, a qualitative study from Sri Lanka. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:52. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0576-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benbassat J. Role modeling in medical education: The importance of a reflective imitation. Acad Med. 2014;89:550–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palinkas L A, Horwitz S M, Green C A, Wisdom J P, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42:533–44. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratnapalan S. Qualitative approaches: Variations of grounded theory methodology. Can Fam Physician. 2019;65:667–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safari Y. Clarifying evidence-based medicine in educational and therapeutic experiences of clinical faculty members: A qualitative study in Iran. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7:62–8. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v7n7p62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:1–8. doi: 10.1177/2050312118822927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Safari Y, Alikhani A, Safari A. Comparison of blended and e-learning approaches in terms of acceptability in-service training health care workers of Kermanshah University of medical sciences. Int J Pharmacy Techno. 2016;8:12893–902. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Safari Y, Yoosefpour N. Data for professional socialization and professional commitment of nursing students - A case study: Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Data Brief. 2018;21:2224–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2018.11.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rose GL, Rukstalis MR. Imparting medical ethics: The role of mentorship in clinical training. Mentoring Tutoring: Partn Learn. 2008;16:77–89. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weaver R, Wilson I. Australian medical students’ perceptions of professionalism and ethics in medical television programs. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Safari Y, Yoosefpour N. Evaluating the relationship between clinical competence and clinical self-efficacy of nursing students in Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. Indian J Public Health Res Develop. 2017;8:380–5. [Google Scholar]