Abstract

Background:

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis, Canada’s provincial chief medical officers of health (CMOHs) have provided regular updates on the pandemic response. We sought to examine whether their messaging varied over time and whether it varied across jurisdictions.

Methods:

We conducted a qualitative study of news releases from Canadian provincial government websites during the initial phases of the COVID-19 outbreak between Jan. 21 and Mar. 31, 2020. We performed content analysis using a predefined data extraction framework to derive themes.

Results:

We identified 290 news releases. Four broad thematic categories emerged: describing the government’s preparedness and capacity building, issuing recommendations and mandates, expressing reassurance and encouraging the public, and promoting public responsibility. Most of the news releases were prescriptive, conveying recommendations and mandates to slow transmission. Cross-jurisdictional variations in messaging reflected local realities, such as evidence of community transmission. Messaging also reflected changing information about the pandemic over time, shifting from a tone of reassurance early on, to a sudden emphasis on social distancing measures, to a concern with public responsibility to slow transmission.

Interpretation:

Messaging across jurisdictions was generally consistent, and variations in the tone and timing of CMOH messaging aligned with different and changing realities across contexts. These findings indicate that when evaluating CMOHs’ statements, it is critical to consider the context of the information they possess, the epidemiologic circumstances in their jurisdiction and the way the province has structured the CMOH role.

Provincial chief medical officers of health (CMOHs) in Canada have multiple roles, including advising elected officials and speaking on their behalf as trusted scientific experts during emergencies.1,2 During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis, CMOHs have become household names, providing regular updates on the pandemic and the government’s response to it. Public opinion data from the COVID-19 outbreak indicate that Canadians have a high degree of trust in CMOHs and strongly value the role of scientific evidence and medical advice in government decision-making and emergency response.3 The confidence placed in these officials underscores the importance of understanding the messages they convey to the public.

Although CMOHs have received praise for their handling of the crisis, they have also faced scrutiny over issues such as the consistency of their messaging across jurisdictions and over time.4–7 We analyzed the key messages that provincial CMOHs conveyed to the public during the initial phases of the COVID-19 crisis. We sought to examine whether and how their messaging differed across jurisdictions and as the crisis evolved.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a qualitative study of all news releases on provincial government websites that were published by, with, or referencing the authority of provincial CMOHs during the early weeks of the COVID-19 outbreak (Jan. 21 to Mar. 31, 2020). This study design was intended to enable the development of a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the key themes communicated in CMOHs’ official messaging and to examine differences across jurisdictions and over time.

Setting

In Canada, each provincial government has a CMOH who is a senior public health official for their province; the 10 provincial CMOHs in this position at the time of our study constituted our study population. Although the title of the senior public health official varies by jurisdiction, the most common term in Canadian provinces is chief medical officer of health. We therefore use this term to refer collectively to the provincial officials occupying this position. A similar position exists at the federal level, but because the federal chief public health officer (CPHO) has relied primarily on daily press conferences rather than news releases to communicate with the public, we included only provincial CMOHs in our analysis to maximize comparability.

The CMOH position is designed to have a central role in the government’s response to infectious disease outbreaks, including by acting as a government spokesperson with credible scientific authority.1,2 Our previous work examining the role of the CMOH from a legal, public administration and public health perspective led us to formulate several expectations about CMOHs’ communications in a pandemic.1,2 We would expect CMOHs, as part of the government response team, to convey information about public health measures to contain the pandemic and not act as independent critics of those measures.2 We would also expect them, as the face of medical expertise within government, to refer to the latest evidence and signal the level of risk and appropriate response to the population. However, we would also expect variations in messaging across provinces given the local epidemiologic context and the different communication roles of CMOHs.1 As local circumstances and information about the virus change, we would also expect messaging to vary over time.

Data sources

We (L.A.W., A.C.) searched news releases from the list of official news releases kept by all provincial governments on their official websites between Mar. 19 and Apr. 3, 2020.8–18 Although CMOHs have used various communication channels throughout the pandemic, we focused solely on news releases because they were consistently employed across most provinces and, as highly regulated communications, can be presumed to reflect CMOHs’ official positions.

We excluded the 3 territories (Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Yukon). Although they also have CMOHs, at the time of our analysis these jurisdictions had very few cases of COVID-19. In light of the different nature of the pandemic between the provinces and territories during our study period, we focused our analysis on provincial messaging. In addition, owing to the different nature of their roles, we did not include messaging from CMOHs whose mandates focus on specific subpopulations, such as the chief medical officer of the First Nations Health Authority in British Columbia.

Our selection criteria considered all communications posted on these lists to constitute news releases for the purpose of this study. In our search parameters, news releases were considered to be about COVID-19 if they were listed in COVID-19–specific repositories or contained terms such as “COVID-19,” “coronavirus,” “pandemic,” “cases,” “travel restrictions,” “school closures,” “state of emergency” and “personal protective equipment.” If there was any ambiguity associated with the headline, we reviewed the full text to confirm relevance. Given the evolving nature of cases associated with COVID-19, corrections to case numbers were occasionally issued in the form of an updated news release indicating a correction. In the few instances where this occurred, the most recent, corrected version was used. We included all COVID-19–related news releases in our data set and excluded news releases on other topics. Information on social distancing (or physical distancing) measures was also collected from provincial government websites.

We (L.A.W., A.C.) additionally searched the Government of Canada website to identify any news releases issued during our study period by the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health (CCMOH). We used the search terms “Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health” and “CCMOH.”

Data extraction

We examined the headlines for each news release issued during our study period (L.A.W. examined headlines for news releases in English and A.C. did so for news releases in French). Included news releases were then read and coded in their entirety by L.A.W. (English news releases) and A.C. (French news releases). The 2 coders worked in conversation with each other. Any differences of opinion were discussed and resolved by consensus.

Data analysis

We used content analysis guided by the 5 iterative stages of qualitative analysis (compiling, disassembling, reassembling, interpreting and concluding) to derive themes.19 Each news release was read in its entirety and coded in an electronic spreadsheet according to the key messages it contained. A data extraction framework was developed by all co-authors a priori (Box 1). The framework was informed by our above-mentioned expectations based on previous research on the CMOH role.1,2 Emergent themes were also identified inductively during data analysis.

Box 1: A priori data extraction framework.

Metadata

Date

Article title

Measure being reported (e.g., school closure, state of emergency)

Individual or institution issuing statement

Statement issued by the chief medical of health alone or jointly with other officials

Illustrative excerpts

Key thematic indicators

Recommendations, requests or legal requirements for public action

Expressions of need for calm, concern or increased vigilance

References to new or evolving evidence about coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

Guidance from the World Health Organization or federal government

References to coordination or contrasts with other jurisdictions

All co-authors discussed initial findings and constructed conceptual themes to connect similar messages under common headings and facilitate more meaningful interpretation and analysis. This involved an iterative process of discussing conceptual themes, verifying our interpretation using the extracted data and refining our conclusions. We conducted a comparative analysis by comparing the percentage of news releases mentioning a particular theme across jurisdictions and over time.

Ethics approval

This study analyzed publicly available news releases and did not require ethics approval.

Results

We identified 290 news releases issued by or with provincial CMOHs between Jan. 21 and Mar. 31, 2020 (Table 1). We did not identify any news releases issued by the CCMOH during this time. Provincial governments began issuing official news releases about COVID-19 at different times, and the number of news releases varied. The earliest news releases were identified in British Columbia (Jan. 21), Quebec (Jan. 22) and Ontario (Jan. 25). The largest number of news releases was identified in BC (56), followed by Manitoba (44); Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador released the fewest (15 and 7, respectively). Although CMOHs occasionally issued news releases alone, they most commonly issued joint releases with elected officials.

Table 1:

Coding summary of provincial news releases issued by and with chief medical officers of health, Jan. 21 to Mar. 31, 2020

| No. (%) of news releases; province | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC n = 56 |

AB n = 23 |

SK n = 29 |

MB n = 44 |

ON n = 41 |

QC n = 15 |

NB n = 25 |

NS n = 29 |

PE n = 20 |

NL n = 7 |

Total n = 290 |

|

| Date of first COVID-19 news release | Jan. 21 | Mar. 14 | Feb. 13 | Jan. 28 | Jan. 25 | Jan. 22 | Mar. 1 | Feb. 28 | Feb. 28 | Mar. 10 | – |

| News releases primarily issued by CMOHs alone, primarily issued jointly with other officials or issued in mixed fashion (sometimes alone and sometimes jointly) | Joint | Joint | Joint | Joint | Mixed | Joint | Mixed | Joint | Solo | Joint | – |

| Describing preparedness and capacity building | |||||||||||

| Efforts to increase and improve testing and case identification | 19 (34) | 2 (9) | 7 (24) | 9 (20) | 4 (10) | 3 (20) | 5 (20) | 9 (31) | 1 (5) | – | 59 (20) |

| Emergency preparedness and contingency planning | 17 (30) | 1 (4) | 11 (38) | 12 (27) | 21 (51) | 4 (27) | 6 (24) | 13 (45) | 3 (15) | – | 88 (30) |

| Issuing recommendations and mandates | |||||||||||

| Cancellations, closures and social distancing recommendations | 26 (46) | 19 (83) | 18 (62) | 22 (50) | 14 (34) | 5 (33) | 13 (52) | 16 (55) | 16 (80) | 5 (71) | 154 (53) |

| Travel-related recommendations and restrictions | 11 (20) | 5 (22) | 12 (41) | 25 (57) | – | 4 (27) | 6 (24) | 26 (90) | 10 (50) | 2 (29) | 101 (35) |

| Enforcement of restrictions | 4 (7) | 5 (22) | – | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | – | 2 (8) | 2 (7) | 6 (30) | – | 22 (8) |

| Characterization of pandemic as serious or emergency situation | 5 (9) | 2 (9) | 5 (17) | 6 (14) | 7 (17) | 3 (20) | 2 (8) | 2 (7) | 3 (15) | 1 (14) | 36 (12) |

| Expressing reassurance and encouraging the public | |||||||||||

| Public reassurance | 27 (48) | 3 (13) | 8 (28) | 9 (20) | 19 (46) | 10 (67) | 5 (20) | 4 (14) | 3 (15) | 1 (14) | 89 (31) |

| Acknowledgement of community cooperation or contributions | 11 (20) | 5 (22) | – | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 8 (53) | 3 (12) | 5 (17) | 3 (15) | – | 38 (13) |

| Promoting public responsibility | |||||||||||

| Discussion of transmission prevention as collective responsibility | 16 (29) | 14 (61) | 4 (14) | 4 (9) | 4 (10) | 6 (40) | 12 (48) | 10 (34) | 1 (5) | 1 (14) | 72 (25) |

| Provision of COVID-19–related information to the public | 9 (16) | 5 (22) | 3 (10) | 12 (27) | 4 (10) | 3 (20) | 9 (36) | 8 (28) | 5 (25) | 2 (29) | 60 (21) |

Note: AB = Alberta, BC = British Columbia, CMOHs = chief medical officers of health, COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, MB = Manitoba, NB = New Brunswick, NL = Newfoundland and Labrador, NS = Nova Scotia, ON = Ontario, PE = Prince Edward Island, QC = Quebec, SK = Saskatchewan.

Themes addressed in communications

The news releases we reviewed fell into 4 broad thematic categories: describing the government’s preparedness and capacity building, issuing recommendations and mandates, expressing reassurance and encouraging the public, and promoting public responsibility.

Describing preparedness and capacity building

News releases in this category communicated government efforts to understand the scope of the pandemic and outlined measures taken to prepare for and address it. They typically relied on epidemiologic data and outlined contingency plans for addressing health care resource scarcity.

Issuing recommendations and mandates

News releases in this category communicated recommendations and restrictions to slow the spread of COVID-19 through social distancing, event cancellations, workplace and school closures, and travel-related self-monitoring and isolation. They also addressed the enforcement of these measures and included cases where CMOHs characterized (or used their statutory authority to declare) the pandemic as a public health emergency that both permitted and required the government to impose stricter regulations.

Expressing reassurance and encouraging the public

This theme emerged in news releases oriented toward reassuring the public and mitigating panic. These news releases generally discouraged fear, encouraged ongoing cooperation with restrictions and praised positive contributions from health care workers and the public. They often referred to the low risk of transmission, particularly at the beginning of the pandemic, and to public health experts who should be relied upon to handle the situation.

Promoting public responsibility

News releases in this category characterized public health as a collective responsibility. They emphasized the importance of changing individual behaviours to prevent disease transmission and called upon everyone to do their part. Statements provided the public with information about COVID-19, including symptoms and methods of prevention. While most of the news releases in this category focused on working together toward a common goal, some reprimanded those who were putting others at risk by failing to heed the restrictions.

Consistency and variation in communications

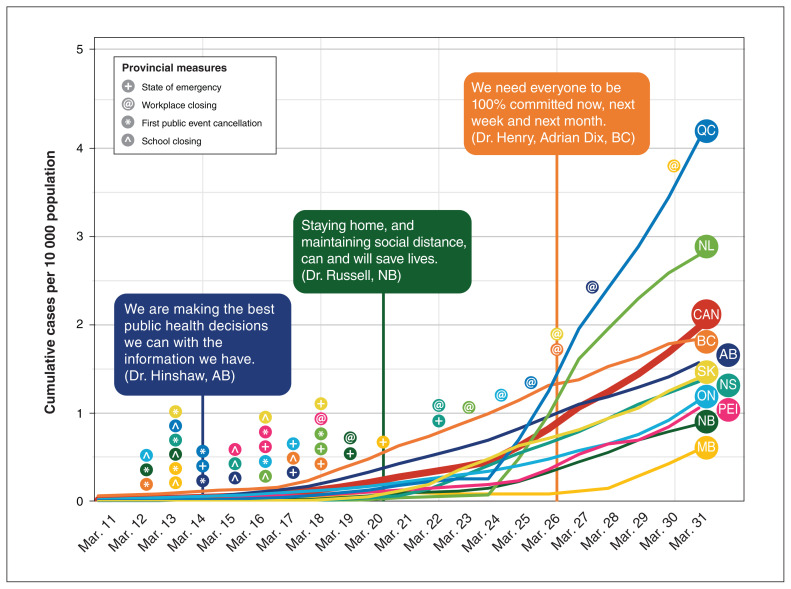

There were many similarities across the provinces in the themes communicated in news releases (Table 1). In particular, prescriptive themes relating to cancellations, closures and other social distancing measures appeared in more than half of the news releases issued by 8 of the 10 provinces and in more than one-third of the releases issued by the remaining 2 provinces. As shown in Figure 1, this consistency was also reflected in the actions that provinces took to address the pandemic.

Figure 1:

Cumulative COVID-19 cases and policy measures by province, Mar. 11–31, 2020. This figure focuses on a subset of our study period that begins when the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic, cases began to increase in Canada and provincial governments began introducing widespread social distancing measures. Cumulative cases per 10 000 population are visually represented as a 3-day rolling average. Case data were obtained from the Government of Canada’s COVID-19 database.20 AB = Alberta, BC = British Columbia, CAN = Canada, COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, MB = Manitoba, NB = New Brunswick, NL = Newfoundland and Labrador, NS = Nova Scotia, ON = Ontario, PE = Prince Edward Island, QC = Quebec, SK = Saskatchewan.

Intergovernmental coordination and integration of chief medical officers of health within government

Our analysis indicates 2 possible reasons for the similarities we observed in the themes communicated in news releases. First, provincial officials consulted common guidelines and coordinated with each other during the pandemic. For example, news releases referred to World Health Organization (WHO) and Public Health Agency of Canada guidance and described ongoing communication among officials across Canada. Second, in keeping with CMOHs’ shared role within government (as opposed to being at arm’s length), statements by and with these officials were used for a broadly similar purpose: they informed the public of the provincial government’s pandemic response rather than questioning or criticizing it. In contrast, there were rare occasions when provincial communications urged a stronger federal response to COVID-19. For example, early in the pandemic, news releases from Quebec called on the federal government to limit entry to foreign visitors, stating that it was inconsistent to ask Quebec’s population to self-isolate after travelling abroad without also restricting incoming travel.21,22

Evolving local circumstances and the design of the chief medical officer of health position

Despite overarching thematic similarities in the content of the news releases, different local circumstances also factored into provincial governments’ messaging. For example, early recommendations often focused on ensuring recent travellers took appropriate precautions upon returning to Canada. These recommendations often broadened to include social distancing measures for everyone once community transmission had been provincially documented. Evidence of community transmission (or lack thereof) was cited as a primary factor in the timing of major policy decisions regarding closures and restrictions in Alberta, Saskatchewan and New Brunswick and was also referenced in relation to widespread social distancing measures in BC, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.23–28 In Alberta, evidence of community transmission was cited as a driving factor in the decision to close schools, childcare facilities and other gathering sites just 2 days after a recommendation was issued that schools should remain open.25 Similarly, in New Brunswick, testing protocols were changed considerably to allow people who had not travelled to be tested as a direct result of the first evidence of community transmission.24

Differences in provincial communications were also consistent with the varying roles of CMOHs across jurisdictions. Although all provincial CMOHs work within the government, provincial governments structure the advisory, management and communications roles of the CMOHs differently, which in turn shapes what these officials can say to the public and how they deliver their message.1,2 In jurisdictions that emphasize the CMOH’s technical advisory role (i.e., Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan), news releases during our study period primarily conveyed factual information about COVID-19 and measures to contain it (Table 1). In provinces that give more emphasis to communicating independent information to the public (i.e., BC, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Ontario), news releases typically covered a wider range of themes, with messages of reassurance or collective responsibility intermingling with messages on containment measures. In provinces where the CMOH’s internal role as a high-level advisor or manager is emphasized (i.e., Alberta, Nova Scotia, Quebec), news releases were less consistent in the content of their messaging, but they were almost exclusively statements issued with elected officials, consistent with the CMOH’s positioning as a loyal public servant.

Variations in messaging over time

During the study period, government communications issued with or by the CMOHs shifted in tandem with changing information about the virus and its local prevalence (Table 2). News releases issued early in the pandemic frequently expressed reassurance. This theme appeared in a considerable proportion of news releases in Quebec (67%), BC (48%) and Ontario (46%), but less often in Alberta (13%), Nova Scotia (14%), Newfoundland and Labrador (14%) and Prince Edward Island (15%) (Table 1). Reassurance also appeared less frequently over time, even among provinces that expressed it most frequently, with steep declines over the study period in BC, Manitoba and Ontario.

Table 2:

Variation in messaging during different phases of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic25,29–36

| Late January–early March 2020 Local reassurance | Mid-March 2020 Public action | Late March 2020 Collective duty |

|---|---|---|

| Je tiens à réitérer que le réseau de la santé est prêt et bien préparé à faire face à une apparition de cas au Québec. La population ne doit pas s’inquiéter. Bien que les cinq cas soient infirmés, comme la situation épidémiologique évolue rapidement, il est attendu et normal que d’autres cas soient investigués. Le Québec a mis en place un système de détection efficace et fiable, et demeure proactif et vigilant. – Dr. Arruda, Quebec (Jan. 24) |

Dr. Heather Morrison has confirmed the first positive case of COVID-19 in the province, and urges Islanders to follow recommendations to limit the potential number of cases and spread of the virus. … It is strongly recommended that Islanders follow the advice of the Chief Public Health Office and … reconsider attending social gatherings where a 2-m distance between people is not possible, especially if elderly or immune-compromised people are present. – Prince Edward Island news release citing Dr. Morrison (Mar. 14) |

We have to protect our health-care workers, so they can carry on with this important work. … When we take actions to limit the spread of this disease, among those we are protecting are the front-line workers that are so valuable in this situation. When you stay home and practise social distancing, you are not only protecting yourselves, you are protecting the people who may soon be saving your life. – Dr. Russell, New Brunswick (Mar. 23) |

| While the risk to residents in Saskatchewan remains low, we are working closely with the Public Health Agency of Canada on preparedness, procedures and reporting to quickly identify and manage any cases that present for care. … Canada has multiple systems in place to prepare for, detect and respond to the spread of serious infectious diseases like novel coronavirus. – Dr. Shahab, Saskatchewan (Feb. 13) |

The new cases that have emerged today, particularly those demonstrating transmission into communities and school settings, mean we need to put in place additional restrictions for schools, day cares, continuing care facilities, and worship gatherings. These decisions are not made lightly, and I know they will have a tremendous impact on Albertans’ day-to-day lives, particularly parents, children, and seniors. But it is crucial we do everything possible to contain and limit the spread of COVID-19. – Dr. Hinshaw, Alberta (Mar. 15) |

Given the number of returning travellers, including snowbirds, and more testing being done, an increase in cases is expected. … We’re 3 weeks into our response and I know this is hard for everyone. Please continue to be part of flattening the curve by following public health advice and direction. – Dr. Strang, Nova Scotia (Mar. 28) |

| The government and public health officials are reminding Manitobans the risk of acquiring COVID-19 in Manitoba remains low, but is increasing given events occurring in Canada and around the world. We must continue to prepare for this virus in Manitoba. – Dr. Roussin, Manitoba (Mar. 10) |

This death is further evidence of the increasing seriousness of the situation we are in, which is why the province has been taking decisive steps to manage the spread of COVID-19 in Ontario. Earlier today, the Ontario government enacted a declaration of emergency closing all facilities providing indoor recreational programs, public libraries, private schools, licensed child care centres, theatres, cinemas, concert venues and bars and restaurants, except to the extent that such facilities provide takeout food and delivery. – Dr. Williams, Ontario (Mar. 17) |

We are at a critical juncture in our provincial COVID-19 response. Every British Columbian has a part to play to flatten the curve. We must all do the right thing and be 100% committed. Dr. Henry and Adrian Dix (Minister of Health), British Columbia (Mar. 31) |

Reflecting growing national and international concern, as well as consistently timed action across provinces (Figure 1), references to cancellations and social distancing recommendations emerged suddenly in the week of Mar. 8–14, 2020, for all provinces except BC, where the theme appeared 1 week earlier. Similarly, mentions of collective responsibility were concentrated later in the study period in nearly all jurisdictions. In Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador, all news releases mentioning this theme were released on or after Mar. 15, 2020. There were similar trends in BC, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

News releases often referenced the rapidly changing epidemiologic and information landscape to explain the government’s latest response and advice. This contextualization was particularly pronounced early in the study period, when officials emphasized the novelty of the situation, the daily increase in knowledge about the virus and its transmission, and the adjustments to governments’ response on the basis of new evidence.

Interpretation

Throughout the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the news releases issued by or with provincial CMOHs were prescriptive, offering recommendations and mandates to slow transmission. The content of news releases was consistent overall, which may reflect the broadly similar purpose of news releases, reference to federal guidance and ongoing communication among officials across jurisdictions. Although we did document variations in the tone and timing of certain messaging, this aligned with different and changing realities across contexts. The trajectory and severity of the COVID-19 pandemic has not been uniform across jurisdictions, and provinces’ differing demographic characteristics and health care capacities create different underlying risk profiles.

Our analysis adds an important dimension to the literature on the roles of CMOHs.1,2 We show how CMOHs’ statutory duty to communicate with the public played out in practice during an emergency that unfolded differently across jurisdictions and evolved rapidly over time.1 Our study demonstrates that their messages should be understood in the context of the information at their disposal, circumstances in their jurisdiction and the role in which they are cast. These findings suggest there is value in having provincial-level CMOHs who can tailor their responses to their jurisdiction’s local context while also sharing information and coordinating measures at the pan-Canadian level. The variation we identified in messaging also suggests that it may prove important for CMOHs to maximize transparency regarding the information and events driving their decisions, particularly in a federation like Canada, where varying messages across provinces — however appropriate locally — might generate confusion.

Our findings also demonstrate that, as previous research has identified, the integration of the CMOH position within government involves trade-offs.1,2 There is an expectation within the public health community that CMOHs serve as autonomous experts who provide the public and policymakers with the best available scientific evidence and, in some cases, act as independent critics of government policy.1,2 These expectations are inconsistent with the realities of emergency situations for 2 reasons. First, the COVID-19 experience has made clear that CMOHs are not the only voices that bring evidence to bear on the pandemic response. They are part of a broader government scientific advisory system. In the high-stakes environment of the COVID-19 pandemic, experts and nonspecialists outside of government have publicly challenged the evidence underlying government advice and policy choices.37–40 Second, the expectation that CMOHs serve as independent communicators breaks down in emergency situations. Whereas during noncrisis situations some CMOHs may have autonomy to comment on the public health agenda, during emergencies they are called on to be team players who contribute to a rapid and unified government response. Our analysis demonstrates that during the early months of the COVID-19 crisis, CMOHs’ communications were highly interconnected with those of elected officials and routinely delivered as joint statements. This creates a tension in the role, because the more the CMOH is integrated into communications issued by the government, the greater the likelihood that they will be perceived as a government spokesperson, potentially also implying endorsement of policy decisions. This is consistent with their formal status as public servants but may compromise the degree to which they are viewed as independent experts during noncrisis situations.2,41,42

In light of these challenges, governments should consider how to optimize the CMOH role for both crisis and noncrisis situations. Particular consideration should be given to whether it is possible for 1 person to credibly act as an independent voice during noncrisis situations and the face of the government response during emergencies.

Limitations

Because we focused on official news releases issued on government websites by or with provincial CMOHs, we did not capture messaging delivered through other channels, such as social media. In provinces that favoured other communication methods or did not explicitly include the CMOH in their communications, relatively fewer news releases were available for analysis. Although we read through the headlines of all news releases listed on official provincial government websites and read the full text when there was ambiguity, it is possible that we missed news releases if they were not posted in official repositories. In addition, although we read through news releases in full during the coding process and the 2 coders worked together closely, there remains the possibility of coding errors or inconsistencies. Our analysis was also limited to provincial CMOHs as we did not include news releases from the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Yukon because of the low number of COVID-19 cases reported in these territories during our study period.

Conclusion

Although the Canadian response to COVID-19 has generally been praised, it has also been criticized for a lack of cross-provincial uniformity. Our analysis indicates that CMOHs’ messaging was generally consistent across provinces in the early months of the crisis. Variations aligned with local differences in the epidemiologic context and the CMOH role. Tailoring a pandemic response to the different provincial experiences of the outbreak may be more appropriate than a one-size-fits-all approach. CMOHs’ ability to issue recommendations that align with their provinces’ circumstances may be viewed as a strength rather than evidence of a lack of coordination.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: Steven Hoffman is scientific director of the Institute of Population and Public Health at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Patrick Fafard and Steven Hoffman conceived the study. Lindsay Wilson and Adèle Cassola analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to study design and interpretation, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (no. 312902) and the Government of Canada’s New Frontiers in Research Fund (grant no. NFRFR-2019-00003).

Data sharing: Data were derived from publicly available sources but can be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research or the Government of Canada.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/8/3/E560/suppl/DC1

References

- 1.Fafard P, McNena B, Suszek A, et al. Contested roles of Canada’s Chief Medical Officers of Health. Can J Public Health. 2018;109:585–9. doi: 10.17269/s41997-018-0080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fafard P, Forest P-G. The loss of that which never was: evaluating changes to the senior management of the Public Health Agency of Canada. Can Public Adm. 2016;59:448–66. doi: 10.1111/capa.12174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy EB, Vikse J, Chaufan C, et al. Canadian COVID-19 social impacts survey: rapid summary of results #1 — risk perceptions, trust, impacts, and responses. Toronto: York University; 2020. [accessed 2020 Apr. 28]. Technical report no 004. Available: https://figshare.com/articles/Canadian_COVID-19_Social_Impacts_Survey_-_Summary_of_Results_1_Risk_Perceptions_Trust_Impacts_and_Responses/12121905. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Picard A. To combat the coronavirus, we need a unified message from coast to coast. Globe and Mail [Toronto] [accessed 2020 May 5]. Available: www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-to-combat-the-coronavirus-we-need-a-unified-message-from-coast-to/

- 5.Mendleson R. Should we wear masks to slow COVID-19? Canada’s top public health doctor now says non-medical masks could prevent some spread. Toronto Star [Toronto] [accessed 2020 May 5]. Available: www.thestar.com/news/canada/2020/04/03/should-we-all-wear-masks-to-slow-covid-19-some-experts-are-shifting-their-advice.html.

- 6.Hua J. Changing advice on non-medical masks and COVID-19 protection from B.C. health officials [video] Global News Hour at 6 BC. 2020. Apr. [accessed 2020 June 19]. Available: https://globalnews.ca/video/6787120/changing-advice-on-non-medical-masks-and-covid-19-protection-from-b-c-health-officials.

- 7.Payne E. Political messaging to Ontarians struggles to keep pace with rapid-moving COVID-19. Ottawa Citizen. 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 June 19]. Available: https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/political-messaging-to-ontarians-struggles-to-keep-pace-with-rapid-moving-covid-19.

- 8.Older COVID-19 news releases. Regina: Government of Saskatchewan; 2020. [accessed 2020 June 25]. Available: www.saskatchewan.ca/government/health-care-administration-and-provider-resources/treatment-procedures-and-guidelines/emerging-public-health-issues/2019-novel-coronavirus/latest-updates/step-details/news-releases/older-covid-19-news-releases#march-2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Communiqués [news releases] Québec: Santé et services sociaux Québec; 2020. [accessed 2020 June 25]. Available: www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/ministere/salle-de-presse/communiques/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Communiqués [news releases] Québec: Premier of Québec; 2020. [accessed 2020 June 25]. Available: www.quebec.ca/en/premier/actualites/communiques/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.BC Gov News [main page] Victoria: Government of British Columbia; [accessed 2020 June 25]. Available: https://news.gov.bc.ca. [Google Scholar]

- 12.COVID-19 news [news releases] St. John’s: Government of Newfoundland and Labrador; [accessed 2020 June 25]. Available: www.gov.nl.ca/releases/covid-19-news/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.COVID-19 media releases [news releases] Winnipeg: Government of Manitoba; [accessed 2020 June 25]. Available: www.gov.mb.ca/covid19/media.html. [Google Scholar]

- 14.News [news releases] Edmonton: Government of Alberta; [accessed 2020 June 25]. Available: www.alberta.ca/news.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 15.News [news releases] Fredericton (NB): Government of New Brunswick; [accessed 2020 June 25]. Available: www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/news/featured_news.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.News [news releases] Halifax: Government of Nova Scotia; [accessed 2020 June 25]. Available: https://novascotia.ca/news/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.News [news releases] Charlottetown: Government of Prince Edward Island; [accessed 2020 June 25]. Available: www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/news. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newsroom: top stories [news releases] Toronto: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; [accessed 2020 June 25]. Available: https://news.ontario.ca/media/en. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin RK. Qualitative research from start to finish. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): outbreak update. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; [accessed 2020 Apr. 14]. modified 2020 Aug. 4. Available: www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le gouvernement du Québec annonce la fermeture des écoles, des cégeps, des universités et des services de garde. Québec: Premier of Québec; 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 Mar. 31]. Available: www.quebec.ca/en/premier/actualites/detail/le-gouvernement-du-quebec-annonce-la-fermeture-des-ecoles-des-cegeps-des-universites-et-des-services/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le gouvernement du Québec déclare l’état d’urgence sanitaire, interdit les visites dans les centres hospitaliers et les CHSLD et prend des mesures spéciales pour offrir des services de santé à distance. Québec: Premier of Québec; 2020. Mar 14, [accessed 2020 Apr. 2]. Available: www.quebec.ca/en/premier/actualites/detail/le-gouvernement-du-quebec-declare-l-etat-d-urgence-sanitaire-interdit-les-visites-dans-les-centres-h/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saskatchewan keeping schools open for now. Regina: Government of Saskatchewan; 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 Mar. 24]. Available: www.saskatchewan.ca/government/news-and-media/2020/march/15/keeping-schools-open-for-now. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Twelve new cases of COVID-19; one previously confirmed has recovered [news release] Fredericton (NB): Government of New Brunswick; 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 Apr. 5]. Available: www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/news/news_release.2020.03.0159.html. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Update 2: COVID-19 pandemic in Alberta (March 15 at 4:30 pm) [news release] Edmonton: Government of Alberta; 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 Mar. 24]. Available: www.alberta.ca/release.cfm?xID=69818C355F188-C2A3-F5C6-875A2A33929D5C05. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joint statement on update on new and existing COVID-19 cases in B.C. [news release] Victoria: Government of British Columbia; 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 Mar. 20]. Available: https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2020HLTH0077-000484. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Twenty new cases of COVID-19 in Nova Scotia [news release] Halifax: Government of Nova Scotia; 2020. Mar 31, [accessed 2020 Mar. 31]. Available: https://novascotia.ca/news/release/?id=20200331001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prince Edward Island confirms seven additional COVID-19 cases [news release] Charlottetown: Government of Prince Edward Island; 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 Mar. 31]. Available: www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/news/prince-edward-island-confirms-seven-additional-covid-19-cases. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aucun cas de coronavirus pour l’instant au Québec — le Québec demeure vigilant et proactif [news release] Québec: Santé et services sociaux Québec; 2020. Jan. [accessed 2020 Apr. 2]. Available: www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/ministere/salle-de-presse/communique-2014/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coronavirus information for public and healthcare providers at saskatchewan. ca [news release] Regina: Government of Saskatchewan; 2020. Feb. [accessed 2020 Mar. 24]. Available: www.saskatchewan.ca/government/news-and-media/2020/february/13/coronavirus-information. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Province working with other jurisdictions to purchase personal protective equipment for health workers and patients [news release] Winnipeg: Government of Manitoba; 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 Mar. 25]. Available: https://news.gov.mb.ca/news/?archive=&item=46925. [Google Scholar]

- 32.PEI confirms first positive case of COVID-19 [news release] Charlottetown: Government of Prince Edward Island; 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 Mar. 31]. Available: www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/news/pei-confirms-first-positive-case-covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Death in Ontario potentially related to COVID-19 [news release] Toronto: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 Mar. 26]. Available: https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2020/03/first-death-in-ontario-related-to-covid-19.html. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Update on COVID-19 [news release] Fredericton (NB): Government of New Brunswick; 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 Mar. 24]. Available: www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/news/news_release.2020.03.0150.html. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joint statement on Province of B.C.’s COVID-19 response, latest updates [news release] Victoria: Government of British Columbia; 2020. Mar. [accessed 2020 Apr. 2]. Available: https://news.gov.bc.ca/21923. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Twenty new cases of COVID-19 in Nova Scotia [news release] Halifax: Government of Nova Scotia; 2020. Mar 28, [accessed 2020 Mar. 30]. Available: https://novascotia.ca/news/release/?id=20200328002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roman K. Missed opportunities to address COVID-19 early may prolong response measures, experts say. CBC News. 2020. Apr. [accessed 2020 May 4]. Available: www.cbc.ca/news/politics/covid-19-canada-federal-response-1.5529263.

- 38.Vipond J. The case for mandatory mask-wearing in Canada. Macleans. 2020. Apr. [accessed 2020 May 4]. Available: www.macleans.ca/society/health/the-case-for-mandatory-mask-wearing-in-canada/

- 39.Viner RM, Russell SJ, Croker H, et al. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:397–404. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30095-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirkey S. COVID-19 modelling numbers are scary. Have we mortgaged our future on an inexact science? National Post [Toronto] 2020. Apr. [accessed 2020 May 4]. Available: https://nationalpost.com/news/covid-19-modelling-numbers-are-scary-have-we-mortgaged-our-future-on-an-inexact-science.

- 41.Salvet JM. Les combats d’Arruda et l’indépendance de la santé publique. Le Soleil [Québec] 2020. Apr. [accessed 2020 June 19]. updated 2020 Apr. 29. Available: www.lesoleil.com/chroniques/jean-marc-salvet/les-combats-darruda-et-lindependance-de-la-sante-publique-6622e83b60a62d610f9e3049088126bd.

- 42.Macpherson D. Horacio Arruda, spin doctor. Montreal Gazette [Montréal] 2020. May 8, [accessed 2020 June 19]. Available: https://montrealgazette.com/opinion/columnists/macpherson-horacio-arruda-spin-doctor.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.