Abstract

Background

Recently, molecular classifications of gastric cancer (GC) have been proposed that include TP53 mutations and their functional activity. We aimed to demonstrate the correlation between p53 immunohistochemistry (IHC) and TP53 mutations as well as their clinicopathological significance in GC.

Methods

Deep targeted sequencing was performed using surgical or biopsy specimens from 120 patients with GC. IHC for p53 was performed and interpreted as strong, weak, or negative expression. In 18 cases (15.0%) with discrepant TP53 mutation and p53 IHC results, p53 IHC was repeated.

Results

Strong expression of p53 was associated with TP53 missense mutations, negative expression with other types of mutations, and weak expression with wild-type TP53 (p<.001). The sensitivity for each category was 90.9%, 79.0%, and 80.9%, and the specificity was 95.4%, 88.1%, and 92.3%, respectively. The TNM stage at initial diagnosis exhibited a significant correlation with both TP53 mutation type (p=.004) and p53 expression status (p=.029). The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for 109 stage II and III GC cases showed that patients with TP53 missense mutations had worse overall survival than those in the wild-type and other mutation groups (p=.028). Strong expression of p53 was also associated with worse overall survival in comparison to negative and weak expression (p=.035).

Conclusions

Results of IHC of the p53 protein may be used as a simple surrogate marker of TP53 mutations. However, negative expression of p53 and other types of mutations of TP53 should be carefully interpreted because of its lower sensitivity and different prognostic implications.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, p53, TP53, Next-generation sequencing, Immunohistochemistry

TP53 is a tumor suppressor gene that encodes the protein p53, which is involved in cell cycle arrest in damaged cells that require DNA repair or in cases of damage beyond repair, triggering apoptosis. A defect in TP53 is a crucial step in carcinogenesis. Previous studies noted that either a defect of the TP53 gene itself or of a gene upstream or downstream of TP53 was found in virtually all human cancers [1-3]. In gastric cancer (GC), p53 overexpression has been reported in 37.8%–54% of cases [4-6]. According to those studies, overexpression of p53 was generally associated with worse overall survival (OS) as well as well-known prognostic factors such as vascular invasion and lymph node metastasis.

In 2014, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network Group proposed a molecular classification of GC [6]. The four subgroups were Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive, microsatellite instability, genomic stability, and chromosomal instability. TP53 alteration is a characteristic of the chromosomal instability group. In the following year, the Asian Cancer Research Group (ACRG) presented a different molecular classification that considered the three factors of microsatellite instability, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and TP53 mutation [7]. The four groups classified by those factors exhibited different prognoses. However, one of the limitations of those two studies was that the methodology used requires high-end and high-cost technologies such as next-generation gene sequencing. Different groups have attempted to develop a more practical implementation of the molecular classification of GC in clinical settings based on the biomarkers of TCGA and ACRG studies [8-10]. The immunohistochemistry (IHC) of p53 was used to practically predict the mutation status of TP53, but interpretation of p53 IHC was varied and has yet to be confirmed. Köbel et al. [11] demonstrated that optimal p53 IHC can accurately predict the mutation status of TP53 in ovarian cancer, which can be very useful in diagnosis of high-grade serous carcinoma. This technique has yet to be validated for GC.

In this study, we aimed to measure the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of p53 IHC as a representation of TP53 mutation status and to investigate the correlation between clinicopathologic features and p53 IHC or TP53 mutations in GC. Therefore, we performed next-generation sequencing (NGS) and p53 IHC in 120 GC cases, and the TP53 mutation statuses were compared with the p53 IHC results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Characterization of patients and sample acquisition

The study population was composed of 120 patients treated at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (Seongnam, Korea) from 2009 to 2019. The median age was 60 years (range, 34 to 82 years), and 85 patients (70.8%) were men. Thirty-eight of the 120 cases (31.7%) were stage II at initial diagnosis, 71 (59.2%) cases were stage III, and 11 (9.2%) were stage IV. Among them, 109 stage II and III patients (90.8%) underwent curative radical resection (R0 resection) without preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy. In the 11 stage IV cases, endoscopic biopsy specimen was collected in one case, metastatectomy specimens in four cases, conversion surgery specimens after chemotherapy in five patients, and gastrectomy specimen in one case for the experiments. Analysis according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification [12] revealed that tubular adenocarcinoma accounted for 54.2% (65 cases) of diagnoses, mucinous adenocarcinoma for 3.3% (4 cases), papillary adenocarcinoma for 3.3% (4 cases), poorly cohesive carcinoma for 30.0% (36 cases), and other minor histologic types for 9.2% (11 cases). For survival analysis, 109 patients with stage II and III GC were followed up from the date of surgery to the date of death or final follow-up. The median follow-up period was 42.2 months (range of 5.4-87.7 months).

Next-generation sequencing

Targeted sequencing of 170 cancer-related gene panels was performed using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue (FFPE) samples as previously described [13]. All FFPE materials had a short cold ischemic time not exceeding 2 hours, fixation time ranging from 8 to 72 hours, and were aged between 0 and 9 years.

In brief, approximately 3 µg of genomic DNA was extracted from FFPE tumor tissues, and the sequencing library was prepared using an Agilent SureSelect Target Enrichment Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. High-throughput sequencing was performed using the HiSeq 2500 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) (Macrogen Inc., Seoul, Korea). After quality control of the FASTQ files, sequencing reads were aligned to the reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner-MEM (BWA-MEM) [14]. Single nucleotide variants and small insertions and deletions (INDELs) were detected using the MuTect2 algorithm [15]. SnpEff and SnpSift v4.3i [16] with dbNSFP v2.9.3 [17] were used for variant annotation with various databases including the OncoKB [18] and ClinVar archives [19].

IHC staining

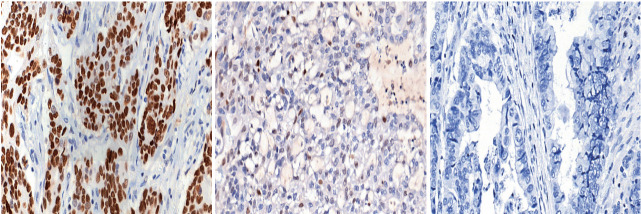

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for p53 (DO7, mouse monoclonal, Dako, Agilent Technologies) was performed on 3-μm-thick slides using an automated immunostainer (BenchMark XT, Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The p53 IHC was interpreted in three tiers: strong nuclear staining in more than 10% of the tumor cells was considered strong positivity, samples without any nuclear staining of tumor cells (complete absence) were interpreted as negativity, and cases exhibiting weak, scattered, or patchy positivity were regarded as weak positivity. Representative images for each category are shown in Fig. 1. Cut-offs of 20% and 30% nuclear positivity were additionally applied for validation of the results.

Fig. 1.

Representative images of strong expression (A), weak expression (B), and loss of expression (C).

For cases where gene mutation and protein expression status did not match (18 cases or 15.0%), p53 IHC was repeatedly performed and interpreted. In most cases (17 out of 18 or 94.4%), repeated immunohistochemical assays did not alter the initial interpretation. Tumor heterogeneity accounted for the change in one case. Initially, strong nuclear expression of p53 was observed in some areas of the tumor (<10%) but was not sufficient to be classified as strong expression. Subsequent IHC was performed on another section of the same tumor, exhibiting overall strong expression of p53.

EBV in-situ hybridization

The EBV status was tested using EBV in-situ hybridization as previously described [20]. A fluorescein-conjugated EBV encoded small RNA (EBER) oligonucleotide probe (INFORM EBVencoded RNA probe, Ventana Medical Systems) was used, and positive cases were defined as diffuse nuclear reactivity for EBER in tumor cells.

Microsatellite instability analysis

Representative tumor tissues and matched normal gastric mucosal tissues were selected for microsatellite instability (MSI) testing. Five NCI markers (BAT-26, BAT-25, D5S346, D17S250, and S2S123) amplified through polymerase chain reaction were analyzed using an automated sequencer (ABI 3731 Genetic Analyzer; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). MSI-high was defined as two or more markers with unstable peaks, MSI-low was defined as one unstable marker, and microsatellite stable was defined as no unstable marker.

Statistical analyses

Chi-square or Fisher exact tests were used to assess significant differences in the distribution of TP53 mutations and p53 expression. For univariate survival analysis, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted in 109 patients with stage II and III GC cases. The survival differences were compared using the log-rank test. For multivariate survival analysis, the Cox regression model was used. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics ver. 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Gene mutation and protein expression correlation

Table 1 summarizes the p53 IHC results according to TP53 mutations. TP53 mutations were present in 52 cases (43.3%), of which missense mutations were the most common (33 of 52 cases, 63.5%). Strong expression was observed in 34 cases (28.3%) and negative expression was observed in 27 cases (22.5%). When TP53 mutations were compared with p53 IHC, 30 of the 33 missense mutation cases (90.9%) exhibited strong p53 expression, but negative expression of p53 was the dominant pattern (15 cases, 78.9%) among the 19 cases of other types of mutations (p<.001). Based on clinical significance, 37 cases (30.1%) had pathogenic or likely pathogenic TP53 mutations, of which 22 cases (59.5%) exhibited strong expression of p53, 13 cases (36.1%) negative expression, and two cases (5.4%) weak expression (p<.001). Nevertheless, most cases of uncertain significance (62.5%) and conflicting interpretations (85.7%) also showed strong expression of p53 by IHC.

Table 1.

Comparison between TP53 genetic mutations and p53 immunohistochemistry

| TP53 mutation | p53 expression by IHC |

Total | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | Negative | Weak | |||

| Mutation status | < .001 | ||||

| Wild-type | 1 (2.9) | 12 (44.4) | 55 (93.2) | 68 (56.7) | |

| Mutation present | 33 (97.1) | 15 (55.6) | 4 (6.8) | 52 (43.3) | |

| Variant summary | < .001 | ||||

| Wild-type | 1 (2.9) | 12 (44.4) | 55 (93.2) | 68 (56.7) | |

| Missense | 30 (88.2) | 0 | 3 (5.1) | 33 (27.5) | |

| Other | 3 (8.9) | 15 (55.6) | 1 (1.7) | 19 (15.8) | |

| Stop-gained | 2 (5.9) | 3 (11.1) | 1 (1.7) | 6 (5.0) | |

| Splice region | 0 | 5 (18.5) | 0 | 5 (4.2) | |

| Frameshift | 0 | 7 (25.9) | 0 | 7 (5.8) | |

| In-frame deletion | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.8) | |

| Clinical significancea | < .001 | ||||

| Wild-type | 1 (2.9) | 12 (44.4) | 55 (93.2) | 68 (56.7) | |

| Pathogenic or likely pathogenic | 22 (64.7) | 13 (48.1) | 2 (3.4) | 37 (30.1) | |

| Uncertain significance | 5 (14.7) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (1.7) | 8 (6.7) | |

| Conflicting interpretation | 6 (17.6) | 0 | 1 (1.7) | 7 (5.8) | |

| Total | 34 | 27 | 59 | 120 | |

Values are presented as number (%).

According to the ClinVar and OncoKB databases accessed on March 18, 2020.

Detailed information about TP53 mutations and p53 expression status is shown in Table 2. Two mutations were observed in three cases, of which one representative mutation was included in this table. One among seven cases with TP53 mutations of conflicting interpretations regarding pathogenicity had weak expression of p53 (case No. 27 in Table 2). There have been reports suggestive of the “likely benign” and “uncertain significance” nature of this mutation. The mutations c.659A>G, c.742C>T, c.817C>T, c.796G>A, c.1024C>T, and c.375G>A were found in two cases, and c.818G>A mutation was found in three cases. The IHC results matched in cases with the same mutation. In 44 cases with single nucleotide polymorphism, C:G to T:A conversion was observed in 32 (72.7%), C:G to A:T in four (9.1%), C:G to G:C in two (4.5%), T:A to C:G in four (9.1%), and T:A to G:C in two (4.5%).

Table 2.

Detailed information of TP53 mutation and p53 expression status in gastric cancer patients with any TP53 mutation

| Case No. | Effect | Nucleic acid alteration | Amino acid alteration | Clinical significancea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Missense_variant | c.422G > A | p.Cys141Tyr | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 2 | Missense_variant | c.422G > T | p.Cys141Phe | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 3 | Missense_variant | c.455C > T | p.Pro152Leu | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 4 | Missense_variant | c.524G > A | p.Arg175His | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 5 | Missense_variant | c.535C > G | p.His179Asp | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 6 | Missense_variant | c.542G > A | p.Arg181His | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 7 | Missense_variant | c.659A > G | p.Tyr220Cys | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 8 | Missense_variant | c.659A > G | p.Tyr220Cys | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 9 | Missense_variant | c.701A > G | p.Tyr234Cys | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 10 | Missense_variant | c.725G > A | p.Cys242Tyr | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 11 | Missense_variant | c.734G > A | p.Gly245Asp | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 12 | Missense_variant | c.742C > T | p.Arg248Trp | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 13 | Missense_variant | c.742C > T | p.Arg248Trp | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 14 | Missense_variant | c.743G > A | p.Arg248Gln | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 15 | Missense_variant | c.772G > A | p.Glu258Lys | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 16 | Missense_variant | c.817C > T | p.Arg273Cys | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 17 | Missense_variant | c.817C > T | p.Arg273Cys | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 18 | Missense_variant | c.818G > A | p.Arg273His | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 19 | Missense_variant | c.818G > A | p.Arg273His | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 20 | Missense_variant | c.818G > A | p.Arg273His | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 21 | Missense_variant | c.380C > T | p.Ser127Phe | Conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity |

| 22 | Missense_variant | c.473G > C | p.Arg158Pro | Conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity |

| 23 | Missense_variant | c.481G > A | p.Ala161Thr | Conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity |

| 24 | Missense_variant | c.613T > C | p.Tyr205His | Conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity |

| 25 | Missense_variant | c.796G > A | p.Gly266Arg | Conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity |

| 26 | Missense_variant | c.796G > A | p.Gly266Arg | Conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity |

| 27 | Missense_variant | c.1015G > A | p.Glu339Lys | Conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity |

| 28 | Missense_variant | c.329G > A | p.Arg110His | Uncertain significance |

| 29 | Missense_variant | c.380C > A | p.Ser127Tyr | Uncertain significance |

| 30 | Missense_variant | c.476C > T | p.Ala159Val | Uncertain significance |

| 31 | Missense_variant | c.797G > T | p.Gly266Val | Uncertain significance |

| 32 | Missense_variant | c.400T > G | p.Phe134Val | Uncertain significance |

| 33 | Missense_variant | c.470T > G | p.Val157Gly | Uncertain significance |

| 34 | Frameshift_variant | c.331_332insAG | p.Leu111fs | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 35 | Frameshift_variant | c.381_391delCCCTGCCCTCA | p.Pro128fs | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 36 | Frameshift_variant | c.635_669delTTCGACATAGTGTGGTG GTGCCCTATGAGCCGCCT | p.Phe212fs | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 37 | Frameshift_variant | c.660_661delTG | p.Tyr220fs | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 38 | Frameshift_variant | c.747delG | p.Arg249fs | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 39 | Frameshift_variant | c.1169delC | p.Pro390fs | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 40 | Frameshift_variant | c.778_779delTC | p.Ser260fs | Uncertain significance |

| 41 | Conservative_inframe_deletion | c.529_546delCCCCACCATGAGCGCTGC | p.Pro177_Cys182del | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 42 | Stop_gained | c.159G > A | p.Trp53* | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 43 | Stop_gained | c.437G > A | p.Trp146* | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 44 | Stop_gained | c.586C > T | p.Arg196* | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 45 | Stop_gained | c.637C > T | p.Arg213* | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 46 | Stop_gained | c.1024C > T | p.Arg342* | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 47 | Stop_gained | c.1024C > T | p.Arg342* | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 48 | Splice_region_variant&synonymous_variant | c.375G > A | p.Thr125Thr | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 49 | Splice_region_variant&synonymous_variant | c.375G > A | p.Thr125Thr | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 50 | Splice_region_variant&synonymous_variant | c.375G > C | p.Thr125Thr | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic |

| 51 | Splice_acceptor_variant&intron_variant | c.920 - 1G > A | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic | |

| 52 | Splice_donor_variant&intron_variant | c.96 + 1G > A | Uncertain significance (no report) |

IHC, immunohistochemistry.

According to the ClinVar and OncoKB databases accessed on March 18, 2020.

Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of p53 IHC for predicting TP53 mutations

In general, nonsynonymous mutations detected using NGS were related to strong p53 expression in IHC. Similarly, all other types of mutations tended to show negative expression, of p53 while cases with wild-type TP53 exhibited weak protein expression. The sensitivity of strong expression of p53 by IHC for predicting nonsynonymous TP53 mutations was 90.9%, sensitivity of negative expression for other types of mutations was 79.0%, and the sensitivity of weak expression for wild-type TP53 was 80.9% (Table 3). The specificity for each category was 95.4%, 88.1%, and 92.3%, respectively. The accuracy for each category was 94.2%, 86.7%, and 85.8%, respectively. In addition, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of p53 IHC at 20% and 30% cut-offs are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The sensitivity of strong expression of p53 for nonsynonymous TP53 mutations was highest at the 10% cut-off.

Table 3.

The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of p53 immunohistochemistry for predicting TP53 mutation, cut-off 10%

| TP53 mutation | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsynonymous mutation by p53 strong expression | 90.9 | 95.4 | 94.2 |

| Other type mutation by negative expression of p53 | 79.0 | 88.1 | 86.7 |

| Wild-type by weak expression of p53 | 80.9 | 92.3 | 85.8 |

Clinicopathological variables and protein expression correlations

The correlation between clinicopathological characteristics and TP53 mutations or p53 expression status is summarized in Table 4. TNM stage at initial diagnosis was the only variable that showed significant correlation with both TP53 mutation type and p53 expression status (p=.004 and p=.029, respectively). Of the 38 stage II gastric cancer cases, 27 (71.1%) did not exhibit any detectable mutations in the TP53 gene, but five nonsynonymous (13.2%) and six other types of mutations (15.8%) were found. Strong p53 expression was found in seven of the 38 stage II cases (18.4%). Among the stage III cases, which accounted for 71 cases, the proportions of nonsynonymous gene mutations and strong expression of p53 mutations increased to 39.4% (28 cases) and 38.0% (27 cases), respectively. On the other hand, the proportions of wild-type TP53 cases and weak expression cases decreased from 71.0% to 45.0% and from 55.2% to 43.6%, respectively.

Table 4.

Clinicopathologic characteristics according to TP53 mutation and p53 expression status

| Characteristic | Total |

TP53 mutation |

p53 expression |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | Other | Wild | p-value | NS | Other | Wild | p-value | ||

| No. | 120 | 33 | 19 | 68 | 34 | 27 | 59 | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.248 | 0.470 | |||||||

| < 65 | 69 (57.5) | 15 (45.5) | 11 (57.9) | 43 (63.2) | 17 (50.0) | 15 (55.6) | 37 (62.7) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 51 (42.5) | 18 (54.5) | 8 (42.1) | 25 (36.8) | 17 (50.0) | 12 (44.4) | 22 (37.3) | ||

| Sex | 0.117 | 0.285 | |||||||

| Male | 85 (70.8) | 27 (81.8) | 15 (78.9) | 43 (63.2) | 27 (79.4) | 20 (74.1) | 38 (64.4) | ||

| Female | 35 (29.2) | 6 (18.2) | 4 (21.1) | 25 (36.8) | 7 (20.6) | 7 (25.9) | 21 (35.6) | ||

| Location of tumor center | 0.940 | 0.856 | |||||||

| Lower third | 53 (44.2) | 15 (45.5) | 10 (52.6) | 28 (41.2) | 16 (47.1) | 11 (40.7) | 26 (44.1) | ||

| Middle third | 33 (27.5) | 9 (27.3) | 4 (21.1) | 20 (29.4) | 7 (20.6) | 8 (29.6) | 18 (30.5) | ||

| Upper third | 34 (28.3) | 9 (27.3) | 5 (26.3) | 20 (29.4) | 11 (32.4) | 8 (29.6) | 15 (25.4) | ||

| TNM at initial diagnosis | 0.004 | 0.029 | |||||||

| II | 38 (31.7) | 5 (15.2) | 6 (31.6) | 27 (39.7) | 7 (20.6) | 10 (37.0) | 21 (35.6) | ||

| III | 71 (59.2) | 28 (84.8) | 11 (57.9) | 32 (47.1) | 27 (79.4) | 13 (48.1) | 31 (52.5) | ||

| IV | 11 (9.2) | 0 | 2 (10.5) | 9 (13.2) | 0 | 4 (14.8) | 7 (11.9) | ||

| WHO classification | 0.733 | 0.596 | |||||||

| Papillary | 4 (3.3) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| Tubular WD/MD | 28 (23.3) | 10 (30.3) | 6 (31.6) | 12 (17.6) | 10 (29.4) | 6 (22.2) | 12 (20.3) | ||

| Tubular PD | 37 (30.8) | 9 (27.3) | 7 (36.8) | 21 (30.9) | 10 (29.4) | 8 (29.6) | 19 (32.2) | ||

| PCC | 36 (30.0) | 8 (24.2) | 3 (15.8) | 25 (36.8) | 7 (20.6) | 7 (25.6) | 22 (37.3) | ||

| Mucinous | 4 (3.3) | 2 (6.1) | 0 | 2 (2.9) | 2 (5.9) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| Others | 11 (9.2) | 3 (9.1) | 2 (10.5) | 6 (8.8) | 4 (11.7) | 3 (11.1) | 4 (6.8) | ||

| Lauren classification | 0.065 | 0.587 | |||||||

| Intestinal | 45 (37.5) | 14 (42.4) | 11 (57.9) | 20 (29.4) | 15 (44.1) | 10 (37.0) | 20 (33.9) | ||

| Non-intestinal | 75 (62.5) | 19 (57.6) | 8 (42.1) | 48 (70.6) | 19 (55.9) | 17 (63.0) | 39 (66.1) | ||

| EBV | 0.215 | 0.036 | |||||||

| Negative | 105 (87.5) | 31 (93.9) | 18 (94.7) | 56 (82.4) | 30 (88.2) | 27 (100) | 48 (81.4) | ||

| Positive | 15 (12.5) | 2 (6.1) | 1 (5.3) | 12 (17.6) | 4 (11.8) | 0 | 11 (18.6) | ||

| MSI | 0.258 | 0.010 | |||||||

| MSS/MSI-L | 112 (93.3) | 32 (97.0) | 19 (100) | 61 (89.7) | 34 (100) | 27 (100) | 51 (86.4) | ||

| MSI-H | 8 (6.7) | 1 (3.0) | 0 | 7 (10.3) | 0 | 0 | 8 (13.6) | ||

Values are presented as number (%).

NS, nonsynonymous; Other, other type mutation; wild, wild-type; WHO, World Health Organization; WD, well-differentiated; MD, moderately differentiated; PD, poorly differentiated; PCC, poorly cohesive carcinoma; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable; MSI-L, microsatellite instability-low; MSI-H, microsatellite instability-high.

TP53 mutations were more frequently observed in intestinaltype GC (25 of 45 cases, 55.6%) compared to the non-intestinal type (27 of 75 cases, 36.0%), but with borderline statistical significance (p=.065). Other clinicopathological variables such as sex, age, tumor location, and WHO classification were not statistically significant.

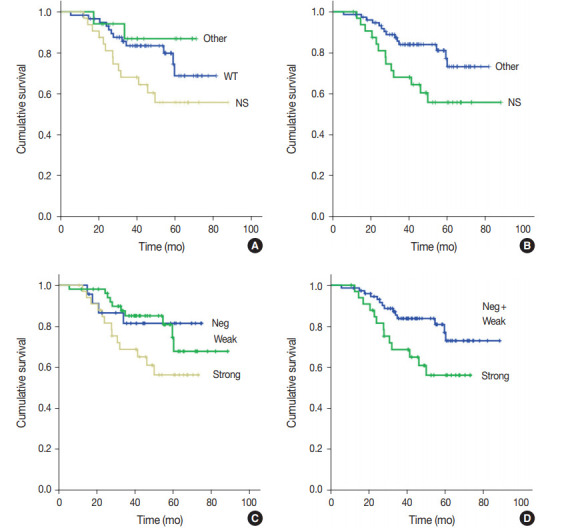

Survival analysis

One hundred nine patients with stage II and III GC at initial diagnosis were selected for survival analysis. The patients underwent curative surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with any TP53 mutations tended to have worse OS compared to those without mutations, although the difference was not statistically significant (p=.227). When OS was analyzed based on TP53 mutation type, patients with nonsynonymous mutations had the worst OS, and the wild-type and other types of mutations exhibited similar OS (p=.074) (Fig. 2A). This trend became statistically significant when the nonsynonymous mutation group was compared to the combined wild-type and other mutation groups (p=.028) (Fig. 2B). The expression pattern of p53 was not significantly associated with patient OS (p=.107) (Fig. 2C), but it was statistically significant when strong expression of p53 was compared to the combined negative and weak expression cases (p=.035) (Fig. 2D). Patients with abnormal— negative and strong expression—expression did not exhibit a statistically significant survival difference compared to patients with weak expression (p=.208). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves of p53 expression status at 20% and 30% cut-offs were additionally plotted in Supplementary Fig. S1. The difference in survival was largest at the 30% cut-off. Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that strong expression of p53 was associated with patient OS independent of stage with borderline significance (p=.070, data not shown). The presence of nonsynonymous missense mutations of TP53 was not an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis (p=.130).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of cumulative survival rate versus follow-up months after surgery according to mutation status (A, B) and immunohistochemistry results (C, D). (A) Nonsynonymous mutations (NS, beige) versus wild-type (WT, green) versus other types of mutations (other, green) (p=.074). (B) Nonsynonymous mutations (NS, green) versus combined wild-type and other types of mutations (other, blue) (p=.028). (C) Strong (beige) versus weak (green) versus negative expression (Neg) (p=.107). (D) Strong (green) versus combined weak and negative expression (Neg+Weak, blue) (p=.035).

DISCUSSION

TP53 is the most well-known tumor suppressor gene, and p53 IHC is a method used in daily practice as a surrogate marker in various cancer patients. In this study, we performed targeted deep sequencing for detecting various TP53 mutations and IHC for p53 using a commercially available and validated primary antibody with an automatic immunostainer. Strong expression of p53 could predict nonsynonymous missense mutations of TP53 with a sensitivity of 90.9%, specificity of 95.4%, and accuracy of 94.2%. However, weak expression of p53 was less specific (80.9%) for predicting wild-type TP53, and negative expression was less sensitive (79.0%) for predicting other mutations of TP53. These results suggest that p53 IHC can be used as a surrogate marker in predicting TP53 mutations, especially for strong expression, to predict nonsynonymous mutations. There have been recent attempts to use IHC for molecular classifications, and their clinicopathological significance has been increasingly important in GC [8,10]. Our results will be helpful for these new molecular classifications although negative expression should be cautiously interpreted.

Based on the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, strong expression of p53 was significantly associated with worse OS compared to weak and negative expression of p53 in this study. Previous studies that investigated any relationship between p53 overexpression and survival reported p53 overexpression as a poor prognostic factor [21-23], similar to the findings from our study. Some studies did not reveal the prognostic significance of p53 overexpression in GC, but a meta-analysis demonstrated that it is a poor prognostic factor [24]. In those studies, the median cut-off value was 10% [24]. Therefore, we applied a cut-off value of 10% for defining strong expression of p53. In addition to the 10% cutoff, we applied 20% and 30% cut-offs in this study. Although the survival difference was largest at the 30% cut-off, the sensitivity of strong expression of p53 for predicting nonsynonymous TP53 mutation was highest at the 10% cut-off. Therefore, further studies are needed to validate various cut-offs.

For interpretation of p53 IHC, Köbel et al. [11,25] proposed a three-tiered scoring system, including overexpression, complete absence, and normal or wild-type pattern in ovarian cancer. The scoring system exhibited good correlation with TP53 mutation status: overexpression with nonsynonymous mutation; complete absence with stop gain, frameshift, and splicing mutations; and a normal pattern with the wild-type TP53 gene [11]. Shin et al. [26] investigated the prognostic roles of p53 expression status in patients with GC. They defined group 0 as complete absence, group 1 as weak staining in <50%, group 2 as strong staining in 50%–90%, and group 3 as strong staining in >90%. When the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed, group 1 was associated with better survival than groups 0, 2, and 3, but with borderline statistical significance. Our results showed a similar relationship between p53 IHC and TP53 mutation status to those of previous studies. If weak expression in this study was defined as a normal or wild-type pattern, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves did not show a significant difference between normal and abnormal expression patterns. Furthermore, patients with GC having nonsynonymous TP53 mutations had significantly worse prognosis compared to patients with other types of mutations and the wild-type TP53 group. Similarly, strong expression of p53, which was related to nonsynonymous TP53 mutations, was shown to be a poor prognostic factor. The complete absence of p53 expression or other types of TP53 mutations might not be significant for predicting prognosis.

There were 17 cases (14.2%) with discrepant results between p53 IHC and TP53 mutations. Most discrepant cases had negative expression of p53 and wild-type TP53. Weak expression of p53 was observed in four missense mutation cases and one stop gain mutation case. These findings might be due to tumor heterogeneity or tissue quality issues, such as specimen ischemic time or archival age. In addition, there was one case with weak p53 expression and a missense mutation of conflicting pathogenic interpretation. Considering this case was conflicting between uncertain significance and likely benign significance, one of the possible reasons for the discrepancy is a non-pathogenic mutation. To discriminate functional and nonfunctional p53, Nenutil et al. [27] performed IHC for p53, Ki67, MDM2, and p21 in human cancers, and overexpressed p53 without increased MDM2 indicated inactivating mutations in their study. p21, a transcriptional target of p53, was considered to reflect p53 activity and could decrease false-positive results of p53 expression [28]. The ACRG considered a TP53-activity signature using p21 and MDM2 genes [7]. Therefore, in addition to p53 IHC, IHC for p21 and MDM2 would be helpful for evaluating the functional status of p53. The need for these additional analyses reflects a potential limitation of this study, necessitating further research.

In a total of 120 gastric cancer cases, 52 (43.3%) had TP53 mutations, including nonsynonymous missense, frameshift, stop gain, in-frame deletion, and splice region mutations. Hot spot mutations within the central core (R175, G245, R248, R273, and R282) were observed in a minority of cases (10 out of 120 or 8.3%). In accordance with our results, a previous study reported hot spot mutations in 6.2% of gastric cancer cases [29]. Therefore, sequencing (Sanger or NGS) is suggested as a suitable method for detecting TP53 mutations in gastric cancer.

In summary, we investigated the relationship between p53 expression and TP53 mutation status to predict TP53 mutations by p53 IHC and reveal their prognostic significance. TP53 mutations were observed in 43.3% of cases. Strong p53 expression could predict nonsynonymous missense mutations with high sensitivity and specificity, but only half of the p53 negative cases (55.6%) exhibited other types of TP53 mutations. Protein overexpression and nonsynonymous genetic mutations of TP53 significantly predicted worse OS. p53 IHC could be regarded as a simple surrogate marker of TP53 mutations, but negative expression of p53 and other types of TP53 mutations should be cautiously considered in daily practice or scientific research. Overall, our study results will be informative for simple molecular classification of patients with GC.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB number: B-2001/591-105). Written informed consent was waived by the IRB.

Author contributions

Conceptionalization: WHK, HSL. Data curation: HJH, HSL. Formal analysis: HJH, HSL. Funding Acquisition: HSL. Investigation: HJH, YP, HP, JK, HYN, YK, HSL. Methodology: HJH, SKN, HP, HSL. Supervision: HSL. Writing—original draft: HJH, HSL. Writing—review & editing: HJH, WHK, HSL. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

W.H.K. and H.S.L., contributing editors of the Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine, were not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (No. 2019R1A2C1086180).

Supplementary Materials

The Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2020.06.01.

References

- 1.Junttila MR, Evan GI. p53: a Jack of all trades but master of none. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:821–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartkova J, Horejsi Z, Koed K, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–70. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starzynska T, Bromley M, Ghosh A, Stern PL. Prognostic significance of p53 overexpression in gastric and colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:558–62. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakeji Y, Korenaga D, Tsujitani S, et al. Gastric cancer with p53 overexpression has high potential for metastasising to lymph nodes. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:589–93. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maehara Y, Tomoda M, Hasuda S, et al. Prognostic value of p53 protein expression for patients with gastric cancer: a multivariate analysis. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1255–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–9. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cristescu R, Lee J, Nebozhyn M, et al. Molecular analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. Nat Med. 2015;21:449–56. doi: 10.1038/nm.3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Setia N, Agoston AT, Han HS, et al. A protein and mRNA expressionbased classification of gastric cancer. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:772–84. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn S, Lee SJ, Kim Y, et al. High-throughput Protein and mRNA Expression-based classification of gastric cancers can identify clinically distinct subtypes, concordant with recent molecular classifications. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:106–15. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koh J, Lee KW, Nam SK, et al. Development and validation of an easy-to-implement, practical algorithm for the identification of molecular subtypes of gastric cancer: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Oncologist. 2019;24:e1321–30. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobel M, Piskorz AM, Lee S, et al. Optimized p53 immunohistochemistry is an accurate predictor of TP53 mutation in ovarian carcinoma. J Pathol Clin Res. 2016;2:247–58. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukayama M, Rugge M, Washington MK. Tumours of the stomach. In: Lokuhetty D, White VA, Watanabe R, Cree IA, editors. WHO classification of tumours. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2019. pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koh J, Nam SK, Roh H, et al. Somatic mutational profiles of stage II and III gastric cancer according to tumor microenvironment immune type. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2019;58:12–22. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011;17:10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cingolani P, Patel VM, Coon M, et al. Using Drosophila melanogaster as a model for genotoxic chemical mutational studies with a new program, SnpSift. Front Genet. 2012;3:35. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Wu C, Li C, Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP v3.0: a one-stop database of functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:235–41. doi: 10.1002/humu.22932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips SM, et al. OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00011. 2017: 10.1200/PO.17.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, et al. ClinVar: public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D862–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park Y, Koh J, Na HY, et al. PD-L1 testing in gastric cancer by the combined positive score of the 22C3 PharmDx and SP263 assay with clinically relevant cut-offs. Cancer Res Treat. doi: 10.4143/crt.2019.718. 2020 Jan 10 [Epub]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song KY, Jung CK, Park WS, Park CH. Expression of the antiapoptosis gene survivin predicts poor prognosis of stage III gastric adenocarcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:290–6. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mrena J, Wiksten JP, Kokkola A, Nordling S, Ristimaki A, Haglund C. COX-2 is associated with proliferation and apoptosis markers and serves as an independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer. Tumour Biol. 2010;31:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13277-009-0001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zha Y, Cun Y, Zhang Q, Li Y, Tan J. Prognostic value of expression of Kit67, p53, TopoIIa and GSTP1 for curatively resected advanced gastric cancer patients receiving adjuvant paclitaxel plus capecitabine chemotherapy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1327–32. doi: 10.5754/hge12204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yildirim M, Kaya V, Demirpence O, Gunduz S, Bozcuk H. Prognostic significance of p53 in gastric cancer: a meta- analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:327–32. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.1.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobel M, Reuss A, du Bois A, et al. The biological and clinical value of p53 expression in pelvic high-grade serous carcinomas. J Pathol. 2010;222:191–8. doi: 10.1002/path.2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin YJ, Kim Y, Wen X, et al. Prognostic implications and interaction of L1 methylation and p53 expression statuses in advanced gastric cancer. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:77. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0661-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nenutil R, Smardova J, Pavlova S, et al. Discriminating functional and non-functional p53 in human tumours by p53 and MDM2 immunohistochemistry. J Pathol. 2005;207:251–9. doi: 10.1002/path.1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe G, Ishida T, Furuta A, et al. Combined immunohistochemistry of PLK1, p21, and p53 for predicting TP53 status: an independent prognostic factor of breast cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1026–34. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tahara T, Shibata T, Okamoto Y, et al. Mutation spectrum of TP53 gene predicts clinicopathological features and survival of gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:42252–60. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.