Abstract

Data show that children are less severely affected with SARS-Covid-19 than adults; however, there have been a small proportion of children who have been critically unwell. In this systematic review, we aimed to identify and describe which underlying comorbidities may be associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 disease and death. The study protocol was in keeping with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A total of 1726 articles were identified of which 28 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The 28 studies included 5686 participants with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection ranging from mild to severe disease. We focused on the 108 patients who suffered from severe/critical illness requiring ventilation, which included 17 deaths. Of the 108 children who were ventilated, the medical history was available for 48 patients. Thirty-six of the 48 patients (75%) had documented comorbidities of which 11/48 (23%) had pre-existing cardiac disease. Of the 17 patients who died, the past medical history was reported in 12 cases. Of those, 8/12 (75%) had comorbidities.

Conclusion: Whilst only a small number of children suffer from COVID-19 disease compared to adults, children with comorbidities, particularly pre-existing cardiac conditions, represent a large proportion of those that became critically unwell.

|

What is Known: • Children are less severely affected by SARS-CoV-2 than adults. • There are reports of children becoming critically unwell with SARS-CoV-2 and requiring intensive care. | |

|

What is New: • The majority of children who required ventilation for SARS-CoV-2 infection had underlying comorbidities. • The commonest category of comorbidity in these patients was underlying cardiac disease. |

Keywords: Paediatric, Adolescent, COVID-19, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), Critically unwell, Comorbidities

Introduction

A cluster of cases of pneumonia of unknown cause was reported in Wuhan, China in December 2019 leading to the identification of a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-Co-V-2) [1]. The virus has spread rapidly, causing wide outbreaks of the associated disease coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) throughout the globe [2].

In adults, the spectrum of disease is well described ranging in severity from asymptomatic carriage to respiratory failure and death [3]. Following the diagnosis of the first paediatric patient with SARS-CoV-2 in China on January 20, 2020, children across the world have been infected [4]. Data show that children are less severely affected than adults, representing approximately 5% of those infected and less than 1% of hospital admissions [5, 6]. However; there have been a small proportion of children who have been critically unwell requiring intensive care with reported fatalities in children under the age of 18. A recent systemic review assessing the clinical features and management of children with SARS-CoV-2 infection reported that children were most likely to have mild symptoms, predominantly respiratory with a minority reporting gastrointestinal symptoms. Only 1 patient was identified with severe disease requiring intensive care, and no data was available on the role of comorbidities in the severity of paediatric COVID-19 [7].

There is a dearth of studies describing an association between risk factors and comorbidities and severe SARS-CoV-2 disease in children. This is relevant; as we move to the recovery phase of the pandemic and shielding restrictions are being relaxed, it is vital to identify patients who are at high risk of severe disease to be able to advise appropriately. In this systematic review, we aimed to identify and describe which underlying comorbidities may be associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 disease and death in children.

Methods

Search strategy and data sources

To identify studies reporting clinical features of children who were critically unwell, defined as requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, with laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, we systematically searched the MEDLINE (PubMed) electronic database from December 1st 2019 to 31st May 2020 using key terms “covid 19 OR coronavirus OR sars-cov2 AND children OR adolescents OR neonate OR infant”. We hand searched the reference lists from retrieved studies and reviews to find additional studies and contacted experts in the field. We also included some additional studies from June 2020 that were found through reading research bulletins so as to not miss key data in this rapidly developing research area.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of all citations for eligibility and retrieved those that met the inclusion criteria. If insufficient information was available in the abstract to decide on eligibility, the whole article was retrieved for review. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and by involving a third reviewer when necessary.

We included case reports, case series, and other observational studies in children under the age of 18. We excluded studies for which the full article was not available and studies that did not contain any original data such as review articles, commentaries and correspondence. Papers reporting information on both children and adults were included only if paediatric data could be retrieved. We excluded studies that focused on other serotypes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. We excluded papers presenting cases of paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (PIMS-TA).

The study protocol was in keeping with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Data extraction

A structured data extraction form was piloted and then used to extract data for all included studies by two reviewers in duplicate. For all articles that we included, if available, we extracted the following data: first author, title, year of publication, country, study design, number of cases, gender, age of patients, comorbidities, clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, radiological findings, treatments and outcomes.

Results

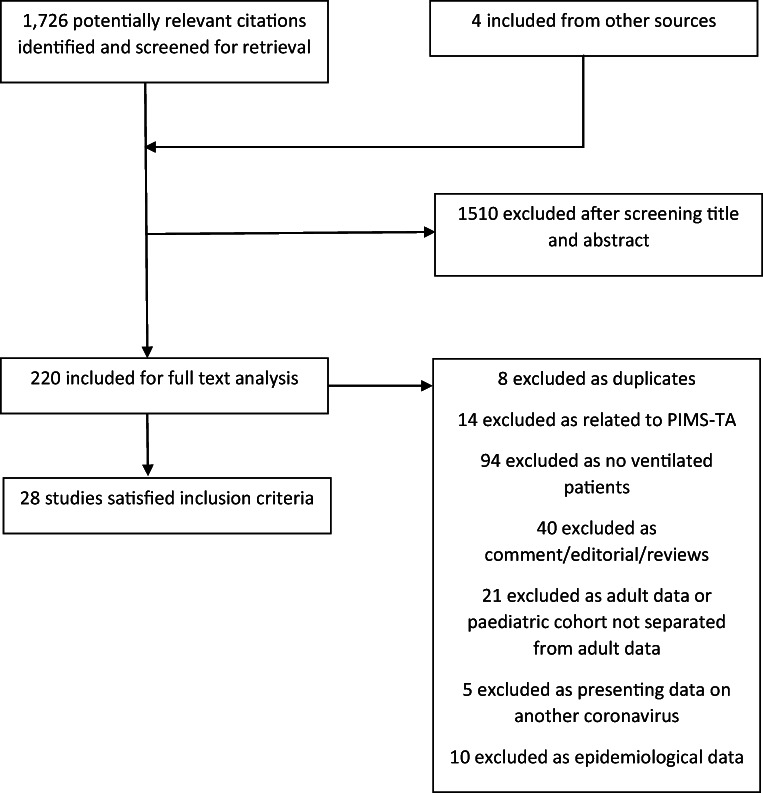

A total of 1,726 articles were retrieved from the electronic search and another 4 were included from a research bulletin recommended by an expert in the field. One thousand five hundred ten articles were excluded after previewing the title and abstract. The remaining 220 papers were retrieved for full text review. A total of 28 papers met the inclusion criteria and were included for analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Quorum diagram

We found a total of 5,686 paediatric cases of SARS-CoV, of which a total of 108 (1.9%) had severe SARS-CoV-2 requiring mechanical ventilation including 17 (0.3%) deaths. Not all studies reported details of patient comorbidities. Of the 108 children who were mechanically ventilated, the medical history was available for 48 patients. Thirty-six of the 48 (75%) had documented comorbidities and 12 (25%) were previously fit and well. Of the 17 patients who died, the past medical history was available for 12 patients; 8 had comorbidities (75%) and 4 (25%) did not (Table 1). One of the children who died was not intubated due to pre-existing comorbidities.

Table 1.

Number of patients in included studies that required ventilation and/or died and their associated comorbidities

| First author | Country | Ventilated patients n | Comorbidities in those ventilated n (%) | Details of comorbidities | Co-infection | Age of those mechanically ventilated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabrero-Hernandez [8] | Spain | 1 | 0 | NA | 12 years | |

| CDC [9] | USA | 15 | Not stated | Not stated | ||

| Chao [10] | USA | 6 | 6 (100%) |

Pt 1 metastatic cancer Pt 2 seizures, asthma Pt 3 congenital heart disease Pt 4 obesity Pt 5 seizures, quadreparesis Pt 6 HTN and OSA |

Age of ventilated patients 4 months–15 years (mean 11.7 years) | |

| Climent [11] | Spain | 1 | 1 (100%) | Muccopolysacharidosis type 1 | 5 m | |

| Cook [12] | UK | 1 | 1 (100%) | Ex-preterm | Staph epidermis in blood culture | 8 weeks |

| Coronado Munoz [13] | USA | 1 | 0 | NA | 3 weeks | |

| Craver [14] | USA | 1 | 0 | NA | 17 years | |

| DeBiasi [15] | USA | 2 | 1 (50%) | Microcephaly, GDD, seizures gastrostomy | 4 years and 16 years | |

| Dong [16] | China | 13 | Not stated | |||

| Garcia-Salido [17] | Spain | 2 | 1 (50%) | Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | 8 years and 12 years | |

| Garazzino [18] | Italy | 2 | 2 (100%) |

Pt 1 ex preterm n = 1 (50%) Pt 2 congenital heart disease n |

Neonate and 2 months old | |

| Kanthimathinathan [19] | UK | 1 | 1 (100%) | Congenital heart disease | Infant | |

| Latimer [20] | USA | 1 | 1 (100%) | 18q deletion and epilepsy | 18 years | |

| Li [21] | China | 1 | 1 | Surgery for nephroblastoma | Mycoplasma | 1 year |

| Lu [22] | China | 3 | 3 (100%) |

Pt 1 hydronephrosis Pt 2 leukaemia on maintenance chemotherapy Pt 3 intussusception |

Not stated | |

| Mannheim [23] | USA | 7 | 4 (57%) |

Cardiac/congenital heart disease n = 2 (50%) Chronic lung disease n = 1 (25%) Trisomy 21 n = 2 (50%) Immunodeficiency n = 1 (25%) |

Infants represented 4 (40%) hospitalized children and 4 (57%) ICU patients | |

| Oualha [24] | France | 9 | Not stated |

One patient blood culture positive for Fusobacterium necrophorum and Strep. constellatus. One patient blood culture and CSF positive for Staph. aureus |

||

| Parri [25] | Italy | 1 | 1 (100%) | Epileptic encephalopathy | 14 years 5 months | |

| Patel [26] | USA | 1 | 0 | NA | 12 years | |

| Peng [27] | China | 1 | Not stated | Not stated | ||

| Qiu [28] | China | 1 | 1 (100%) | Cardiac surgery and recurrent pneumonia | 8 months | |

| Shaw [29] | USA | 1 | 1 (100%) | DORV D-malposed great arteries, subpulmonary ventricular septal defect (VSD), type A interrupted aortic arch, hypogammaglobulinemia immunodeficiency previous tracheostomy | 3 years | |

| Shekerdemian [30] | USA | 18 | Number of ventilated patients with comorbidities not stated (but 40/48 (83%) of patients admitted to PICU had underlying conditions) | |||

| Tagarro [31] | Spain | 1 | Not stated | Not stated | ||

| Tullie [32] | UK | 3 | 1 (33%) | Mild asthma | Children who were ventilated aged 8–14 (mean 11 years) | |

| Wang [33] | China | 3 | Not stated | . | Not stated | |

| Zachariah [34] | USA | 9 | 8 (89%) |

Obesity 6 (67%) Asthma 2 (22%) Immunosuppression 1 (11%) Neurological 1 (11%) Sickle cell disease 1 (11%) Cardiac 1 (11%) diabetes 2 (22%) genetic syndromes 2 (22%) |

Infants less severely affected | |

| Zheng [35] | China | 2 | 2 (100%) |

Pt 1 congenital heart diseases, malnutrition, and suspected hereditary metabolic diseases Pt 2 congenital heart disease |

One patient positive for Enterobacter aerogenes | Both infant age group (8 and 11 months) |

NA not applicable, PICU paediatric intensive care unit, HTN hypertension, OSA obstructive sleep apnoea, GDD global developmental delay, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

Comorbidities

The details of documented comorbidities of those children who required mechanical ventilation with SARS-CoV-19 are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Documented comorbidities in mechanically ventilated children with SARS-CoV-19 (some patients had more than one comorbidity)

| Cardiovascular | |

| Cardiovascular including congenital heart disease and cardiomyopathy | 10/48 (21%) |

| Hypertension | 1/48 (2%) |

| Mucopolysacharidosis with cardiac failure | 1/48 (2%) |

| Neurological | |

| Epilepsy, neurodegenerative disorders and cerebral palsy | 5/48 (10%) |

| Respiratory | |

| Asthma or reactive airway disease | 5/48 (10%) |

| Recurrent chest infections | 1/48 (2%) |

| OSA | 1/48 (2%) |

| Immunosuppressed/Oncology/Haematology | |

| Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | 1/48 (2%) |

| Leukaemia on maintenance chemotherapy | 1/48 (2%) |

| Immunodeficiency | 3/48 (6%) |

| Sickle cell disease | 1/48 (2%) |

| Metastatic cancer | 1/48 (2%) |

| Nephroblastoma | 1/48 (2%) |

| Genetic syndromes | |

| Genetic syndrome unspecified | 2/48 (4%) |

| T21 | 2/48 (4%) |

| 18q deletion | 1/48 (2%) |

| Endocrine | |

| Diabetes | 2/48 (4%) |

| Obesity | 7/48 (15%) |

| Other | |

| Prematurity | 2/48 (4%) |

| Intussusception | 1 (2%) |

| Hydronephrosis | 1 (2%) |

| No comorbidity | 12 (25%) |

Age

Many of the articles either did not report explicitly on the age of the patients with severe disease. For the patients who required mechanical ventilation or died for whom this data was available, 13 were < 1 year of age and 25 were > 1 year of age. Specifically, looking at the patients who died from SARS-CoV-19, age was documented in 13/17, of whom 2 were under the age of one (Table 3). The youngest patient to require mechanical ventilation was an ex preterm neonate in Italy and the youngest death reported was in a 5-month-old infant from Spain who had a history of muccopolysacharidosis type 1 and pre-existing cardiac failure.

Table 3.

Demographics of patients who died with SARS-CoV-19

| First author | Number who died | Age | Sex | Ethnicity | Comorbidities | Other details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC | 3 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Chao | 1 | 11 y | M | Black | Metastatic cancer | Family chose to withdraw care after a period of invasive mechanical ventilation |

| Climent | 1 | 5 m | M | – | Mucopolysaccharidosis with heart failure | Was on ACE inhibitor prior to admission |

| Craver | 1 | 17 y | M | African American | Nil | Eosinophilic myocarditis on post mortem examination |

| Dong | 1 | 14 y | M | – | – | – |

| Lu | 1 | 10 m | – | – | Intussusception | |

| Oualha | 5 | 16 y | F | Nil | ||

| 16 y | M | – | Nil | Sphenoidal sinusitis with cavernous sinus thrombosis. Blood culture positive for Fusobacterium necrophorum and Strep. constellatus. Left middle cerebral artery stroke. | ||

| 6 y | F | – | Nil | Myocarditis and septic shock. Blood culture and CSF-positive for Staph aureus. Underwent ECMO and suffered massive brain haemorrhage. | ||

| 4 y | M | – | Chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | ARDS and multiorgan failure | ||

| 17 y | F | – | Epilepsy and major neonatal encephalopathy | Not intubated due to mutual decision to withdraw care | ||

| Shekerdemian | 2 | 12 y | – | – | Had comorbidities but no details given | Multiorgan failure |

| 17 y | – | – | Had comorbidities but no details given | Multiorgan failure | ||

| Wang | 1 | 8 y | M | – | ALL in remission | |

| Zachariah | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

M male, F female, y year, m month

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first systematic review of children who have suffered critical illness following SARS-CoV-2 infection and in whom past medical history has been reported. In keeping with previous reports, the data presented show that the absolute risk of critical illness in children is low with intensive care treatment an infrequent occurrence. However, we have identified for the first time, that children with comorbidities have an increased relative risk of critical illness; this group comprising the majority of children who have required mechanical ventilation and the majority of children who have died. The comorbidities identified encompass a broad spectrum of diseases, cardiac disease being the most frequent. This is in keeping with a recent systematic review which looked specifically at cardiac disease in paediatric patients with SARS-CoV-19 and concluded that previous cardiac surgery is related with the risk of a more severe form of the disease [36].

Interpretation

There are two fascinating features of SARS-CoV-2 as pertaining to disease in children; the risk of acquiring the infection appears to be lower than in adults (1% v 3.5%), and once infected, the risk of severe disease is almost 25 times lower than in adults [6]. The immune mechanisms underlying the duel phenomena of enhanced resistance to infection and enhanced resistance to severe disease are yet to be elucidated; however, the magnitude of this effect appears sufficient to protect most children with comorbidities from severe disease. Indeed, the data presented showed that only a small number of children with comorbidities actually suffered from critical illness, though data on pre-existing comorbidities was only available in 48 of the 108 patients who required mechanical ventilation.

Despite the low absolute risk of critical disease in children, the data presented show an increased relative risk for children with comorbidities. Chronic cardiac disease, respiratory disease and obesity are prominent comorbidities associated with critical disease. Interestingly, these comorbidities are also described as risk factors for severe disease in adults. In a large prospective observational cohort study of adults with severe COVID-19 infection, the most frequent comorbidities identified were chronic cardiac disease (29%), diabetes (19%), non-asthmatic chronic pulmonary disease (19%), asthma (14%) and obesity (11%) [37].

In contrast to adult data, immunological, haematological and oncological disease (with presumed immunosuppression) comprises 17% of comorbidities in the children described. This is surprising as it is thought that immunosuppression may have a protective effect in adults through interference with the aberrant inflammatory response associated with severe disease in adults [38]. Furthermore, studies of paediatric cohorts on immunosuppression have reported no increase in risk of severe disease [38–40]. Discerning an influence of immunosuppression may be difficult due to a relatively small effect, the influence of the underlying disease itself and the differing influences of different types of immunosuppression. Indeed, only a small number of immunosuppressed children identified in this study had critical disease implying that the absolute risk of critical disease associated with immunosuppression is small.

Older age has been found to be an important risk factor for severe disease in adults [37]. In children being less than 1 year of age has been reported to be a risk factor for severe disease [16]. In this review, we found that 35% of all children mechanically ventilated were infants under 1 year of age which suggests under 1’s are disproportionately affected by severe COVID-19. This is in keeping with a large European multi-centre study that found 29% of patients under 18 year of age infected with COVID-19 were in the infant age group and 48% of those admitted to ICU were under 2 years of age [41].

In the UK and the USA, countries with ethnically diverse populations, mortality is disproportionately high in adult populations of ethnic minority groups, and those of lower socio-economic status [42]. The complex factors underlying the relationship between COVID-19 and these demographic features are yet to be fully defined. We were unable to explore if these factors are important in severity of disease in children as socio-economic, and ethnicity data was rarely reported in the included studies.

The main weakness of this study was the potential missing data from studies that reported combined adult and paediatric data, where we were unable to extract the relevant paediatric data. Another weakness was that information on comorbidities was only available in 48 of the 108 patients who required mechanical ventilation, and more detail on the demographics and past medical history of all patients included would strengthen the conclusions and avoid selection bias. We are also aware that in this rapidly developing research area, new data is being published daily that may complement the data in this review. We must also stress that this data cannot be used to estimate individual risk as there is no universal testing; we cannot be sure how many children in a population are infected with COVID-19 at any one time. The majority of the included studies are from developed countries, and the impact on the developing world needs to be further studied. The key strength of this systematic review is that it is the largest study to date to look at the effect of comorbidities in children with severe COVID-19 and may be able to contribute to the discussion on social distancing and shielding in this population.

Conclusion

Children with comorbidities have a predisposition to critical illness following infection with COVID-19 although the absolute risk remains low. These data are important in the assessment of risk with regard to the planned relaxation of social distancing measures for these children and their families. Prospective data collection is required to better define risk factors for severe disease including comorbidities, age, ethnicity and socio-economic status.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- PIMS-TA

Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Authors’ contributions

Data collection (screening papers/data extraction) NW, TR, PA

Interpretation: NW, TR, PA, JC, KH, AG

Original draft preparation: NW

Review and editing: TR, PA, JC, KH, AG

All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nia Williams, Email: nia.williams00@imperial.ac.uk.

Trisha Radia, Email: trisharadia@nhs.net.

Katharine Harman, Email: K.Harman1@nhs.net.

Pankaj Agrawal, Email: Pankaj.agrawal@nhs.net.

James Cook, Email: jwa.cook@nhs.net.

Atul Gupta, Email: atul.gupta@kcl.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS, China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19 Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19: 11 March 2020. Published March 11, 2020. Accessed 30th June 2020

- 3.Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, Villamizar-Peña R, Holguin-Rivera Y, Escalera-Antezana JP, Alvarado-Arnez LE, Bonilla-Aldana DK, Franco-Paredes C, Henao-Martinez AF, Paniz-Mondolfi A, Lagos-Grisales GJ, Ramírez-Vallejo E, Suárez JA, Zambrano LI, Villamil-Gómez WE, Balbin-Ramon GJ, Rabaan AA, Harapan H, Dhama K, Nishiura H, Kataoka H, Ahmad T, Sah R, Latin American Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019-COVID-19 Research (LANCOVID-19). Electronic address: https://www.lancovid.org Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;34:101623. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y et al (2020) Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 13]. JAMA Intern Med 180(7):1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(6):1088–1095. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castagnoli R, Votto M, Licari A, Brambilla I, Bruno R, Perlini S, Rovida F, Baldanti F, Marseglia GL (2020) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents: a systematic review [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 22]. JAMA Pediatr. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cabrero-Hernández M, García-Salido A, Leoz-Gordillo I, Alonso-Cadenas JA, Gochi-Valdovinos A, González Brabin A, de Lama Caro-Patón G, Nieto-Moro M, de-Azagra-Garde AM, Serrano-González A. Severe SARS-CoV-2 infection in children with suspected acute abdomen: a case series from a tertiary hospital in Spain [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 26] Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:e195–e198. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC COVID-19 Response Team Coronavirus disease 2019 in children - United States, February 12-April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):422–426. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chao JY, Derespina KR, Herold BC, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized and critically ill children and adolescents with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at a tertiary care medical center in New York City [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 11] J Pediatr. 2020;S0022-3476(20):30580–30581. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Climent FJ, Calvo C, García-Guereta L, Rodríguez-Álvarez D, Buitrago NM, Pérez-Martínez A. Fatal outcome of COVID-19 disease in a 5-month infant with comorbidities [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 27] Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2020;S1885-5857(20):30172–30179. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook J, Harman K, Zoica B, Verma A, D'Silva P, Gupta A. Horizontal transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 to a premature infant: multiple organ injury and association with markers of inflammation [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 19] Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;S2352-4642(20):30166–30168. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30166-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coronado Munoz A, Nawaratne U, McMann D, Ellsworth M, Meliones J, Boukas K. Late-onset neonatal sepsis in a patient with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):e49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craver R, Huber S, Sandomirsky M, McKenna D, Schieffelin J, Finger L (2020) Fatal eosinophilic myocarditis in a healthy 17-year-old male with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2c). Fetal Pediatr Pathol 39(3):263–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.DeBiasi RL, Song X, Delaney M, et al. Severe COVID-19 in children and young adults in the Washington, DC metropolitan region [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 13] J Pediatr. 2020;223:199–203.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, Qi X, Jiang F, Jiang Z, Tong S. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20200702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Salido A, Leoz-Gordillo I, Martínez de Azagra-Garde A et al (2020) Children in critical care due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: experience in a Spanish hospital [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 27]. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Garazzino S, Montagnani C, Donà D, et al. Multicentre Italian study of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents, preliminary data as at 10 April 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(18):2000600. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.2000600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanthimathinathan HK, Dhesi A, Hartshorn S et al (2020) COVID-19: a UK children’s hospital experience. Hosp Pediatr 10(9):802–805 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Latimer G, Corriveau C, DeBiasi RL, et al. Cardiac dysfunction and thrombocytopenia-associated multiple organ failure inflammation phenotype in a severe paediatric case of COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 18] Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;S2352-4642(20):30163–30162. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30163-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Cao J, Zhang X, Liu G, Wu X, Wu B. Chest CT imaging characteristics of COVID-19 pneumonia in preschool children: a retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):227. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02140-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu X, Zhang L, Du H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):1663–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mannheim J, Gretsch S, Layden JE, Fricchione MJ (2020) Characteristics of hospitalized pediatric COVID-19 cases - Chicago, Illinois, March - April 2020 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 1]. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Oualha M, Bendavid M, Berteloot L, Corsia A, Lesage F, Vedrenne M, Salvador E, Grimaud M, Chareyre J, de Marcellus C, Dupic L, de Saint Blanquat L, Heilbronner C, Drummond D, Castelle M, Berthaud R, Angoulvant F, Toubiana J, Pinhas Y, Frange P, Chéron G, Fourgeaud J, Moulin F, Renolleau S. Severe and fatal forms of COVID-19 in children. Arch Pediatr. 2020;27(5):235–238. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2020.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parri N, Lenge M, Buonsenso D (2020) Coronavirus infection in pediatric emergency departments (CONFIDENCE) Research Group. Children with Covid-19 in pediatric emergency departments in Italy. N Engl J Med 383(2):187–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Patel PA, Chandrakasan S, Mickells GE, Yildirim I, Kao CM, Bennett CM. Severe pediatric COVID-19 presenting with respiratory failure and severe thrombocytopenia [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 4] Pediatrics. 2020;146:e20201437. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng H, Gao P, Xu Q, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in children: characteristics, antimicrobial treatment, and outcomes [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 7] J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104425. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu L, Jiao R, Zhang A, Chen X, Ning Q, Fang F, Zeng F, Tian N, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Sun Z, Dhuromsingh M, Li H, Li Y, Xu R, Chen Y, Luo X (2020) A typical case of critically ill infant of coronavirus disease 2019 with persistent reduction of T lymphocytes [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 1]. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 10.1097/INF.0000000000002720 Publish Ahead of Print [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Shaw R, Tighe N, Odegard KC, Alexander P, Emani S, Yuki K. Intubation precautions in a pediatric patient with severe COVID-19. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2020;58:101495. doi: 10.1016/j.epsc.2020.101495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shekerdemian LS, Mahmood NR, Wolfe KK, Riggs BJ, Ross CE, McKiernan CA, Heidemann SM, Kleinman LC, Sen AI, Hall MW, Priestley MA, McGuire JK, Boukas K, Sharron MP, Burns JP, for the International COVID-19 PICU Collaborative (2020) Characteristics and outcomes of children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection admitted to US and Canadian pediatric intensive care units [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 11]. JAMA Pediatr. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Tagarro A, Epalza C, Santos M et al (2020) Screening and severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Children in Madrid, Spain [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 8]. JAMA Pediatr:e201346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Tullie L, Ford K, Bisharat M, et al. Gastrointestinal features in children with COVID-19: an observation of varied presentation in eight children [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 19] Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;S2352-4642(20):30165–30166. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30165-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Zhu F, Wang C (2020) The risk of Children Hospitalized With Severe COVID-19 in Wuhan [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 6]. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 10.1097/INF.0000000000002739 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Zachariah P, Johnson CL, Halabi KC, Ahn D, Sen AI, Fischer A, Banker SL, Giordano M, Manice CS, Diamond R, Sewell TB, Schweickert AJ, Babineau JR, Carter RC, Fenster DB, Orange JS, McCann TA, Kernie SG, Saiman L, for the Columbia Pediatric COVID-19 Management Group (2020) Epidemiology, clinical features, and disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a children’s hospital in New York City, New York [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 3]. JAMA Pediatr:e202430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Zheng F, Liao C, Fan QH, et al. Clinical characteristics of children with coronavirus disease 2019 in Hubei, China. Curr Med Sci. 2020;40(2):275–280. doi: 10.1007/s11596-020-2172-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanna G, Serrau G, Bassareo PP, Neroni P, Fanos V, Marcialis MA. Children’s heart and COVID-19: up to date evidence in the form of a systematic review. Eur Journal Paed. 2020;179:1079–1087. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03699-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO clinical characterisation protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warraich R, Amani L, Mediwake R, Tahir H. Immunosuppression drug advice and COVID-19: are we doing more harm than good. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2020;81(6):1–3. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2020.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marlais M, Wlodkowski T, Vivarelli M, Pape L, Tönshoff B, Schaefer F, Tullus K. The severity of COVID-19 in children on immunosuppressive medication [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 13] Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(7):e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30145-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner D, Huang Y, Martín-de-Carpi J, Aloi M, Focht G, Kang B, Zhou Y, Sanchez C, Kappelman MD, Uhlig HH, Pujol-Muncunill G, Ledder O, Lionetti P, Dias JA, Ruemmele FM, Russell RK. Corona virus disease 2019 and paediatric inflammatory Bowel diseases: global experience and provisional guidance (March 2020) from the Paediatric IBD Porto Group of European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70(6):727–733. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gotzinger, et al. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: a multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolescent Health. 2020;4:653–661. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(20)30177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus COVID-19 related deaths by ethnic group, England and Wales: 2 March 2020 to 10 April 2020. Accessed June 30th 2020 (https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/coronavirusrelateddeathsbyethnicgroupenglandandwales/2march2020to10april2020