Abstract

Following the devastation of the Greater New Orleans, Louisiana, region by Hurricane Katrina, 25 nonprofit health care organizations in partnership with public and private stakeholders worked to build a community-based primary care and behavioral health network. The work was made possible in large part by a $100 million federal award, the Primary Care Access Stabilization Grant, which paved the way for innovative and sustained public health and health care transformation across the Greater New Orleans area and the state of Louisiana.

After Hurricane Katrina devastated the Greater New Orleans (GNO), Louisiana, area, the US Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) awarded the Primary Care Access Stabilization Grant (PCASG) to the Louisiana Department of Health to be programmatically administered by the Louisiana Public Health Institute.1,2

INTERVENTION

The PCASG was created primarily to fund the transformation of primary care services by supporting community-based health care organizations in improving care access, coordination, quality, and sustainability, while reducing the GNO area residents’ reliance on emergency departments.

PLACE AND TIME

From June 2007 through September 2011, the PCASG was implemented in the GNO area, which comprises four parishes (called “counties” in many states): Jefferson, Orleans, Plaquemines, and St. Bernard.

PERSON

The PCASG was implemented across 25 community-based health care organizations, which served more than 405 000 unduplicated individuals.

PURPOSE

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent failure of the levee system caused significant damage, resulting in health care infrastructure destruction and workforce displacement.3 Local, state, and national stakeholders convened to strategize and create action plans for the most immediate health needs of the GNO area residents and to address the longer term health care infrastructure needs.4

The community agreed that this crisis brought an opportunity to create a health care system that was more responsive to GNO area residents’ needs, particularly residents who were lower income or under- or uninsured. Before Katrina, the Medical Center of Louisiana (formerly Charity Hospital), the state-run public hospital, served the primary care needs of lower income and uninsured GNO area residents in both its emergency departments and outpatient clinics.1

By the end of 2005, the Greater New Orleans Health Planning Group released a framework report that called for increasing community-based clinics in the areas of highest need.1 This report also informed policy development for health care redesign efforts. The Louisiana Healthcare Redesign Collaborative4 convened in 2006; it released a report that informed the plan for rebuilding the health care infrastructure in the hurricane-affected areas of Louisiana and offered public testimony to federal legislators to request that immediate resources be granted to the GNO area. As a result of these efforts, on May 23, 2007, the CMS released the PCASG—a three-year $100 million grant under section 6201(a)(4) of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (Pub L No. 109-171)—to fund the GNO area health care organizations in an effort to transform the primary health care infrastructure.1,2 The PCASG was awarded to the Louisiana Department of Health with the Louisiana Public Health Institute as the local partner.1,2

The Commonwealth Fund reported that restoring health care to how it existed before the storm would have been detrimental to the health of GNO area residents—risking “experiencing the same uneven quality, high utilization, and poor health outcomes [that] historically characterized the state’s health system performance.”5(p2) A new opportunity came from the PCASG to move from a hospital-based system to a community-based primary care network that was well organized and offered high-quality, person-centered care.5

IMPLEMENTATION

The PCASG project team solicited applications from community-based health care organizations that provided primary care services in the GNO area at the time of application. In August 2007, through a noncompetitive grant application process, the PCASG project team awarded grants to 25 of the 42 eligible applicants. To receive the grant, PCASG-participating organizations were required to attest to the grant conditions as well as the following: operating in the GNO area and offering primary care services, serving all residents regardless of ability to pay, and having created a sustainability plan.1,2 The PCASG-participating organizations (see the box on this page) comprised 17 community health centers and eight community behavioral health organizations that separately operated 67 service delivery sites. The number of practice sites steadily grew from 67 to reach a high of 95 sites, and as of June 2011, there were 71 practice sites operating.1 The decrease in site participation was attributable to the organizations being unable to sustain operations without grant funding or to organizations opting not to continue during the no-cost extension period because of the anticipated limited PCASG funding and the continued requirement to comply with grants administration and reporting.

BOX 1. Primary Care Access Stabilization Grant Participating Organizations: Louisiana, 2007–2011.

| Community Health Centers | Community Behavioral Health Organizations |

| Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund | Covenant House New Orleans |

| Children’s Hospital Medical Practice Corp. | Catholic Charities Archdiocese of New Orleans |

| Common Ground Health Clinic | Jefferson Parish Human Services Authority |

| City of New Orleans Health Department | LSU Healthcare Network Behavioral Science Center |

| Daughters of Charity Services of New Orleans | Metropolitan Human Services District |

| EXCELth, Inc. | New Orleans Adolescent Hospital Community Services |

| Jefferson Community Healthcare Centers, Inc. | Odyssey House Louisiana, Inc. |

| Leading Edge Services International, Inc. | Sisters of Mercy Ministries (DBA Mercy Family Center) |

| Lower 9th Ward Health Clinic | |

| LSU Health Sciences Center New Orleans | |

| Medical Center of Louisiana at New Orleans | |

| New Orleans Musicians’ Assistance Foundation | |

| NO/AIDS Task Force | |

| Plaquemines Medical Center | |

| St. Bernard Health Center (now Access Health Louisiana) | |

| St. Charles Community Health Center-Kenner (now Access Health Louisiana) | |

| St. Thomas Community Health Center |

Note. LSU = Louisiana State University.

Source. Louisiana Public Health Institute.1,2

EVALUATION

The PCASG evaluation consisted of internal programmatic evaluation and monitoring activities at the practice and systems levels conducted by the Louisiana Public Health Institute, as well as external evaluation and research activities being administered by the University of California, San Francisco and the Commonwealth Fund.1 There was no control group.

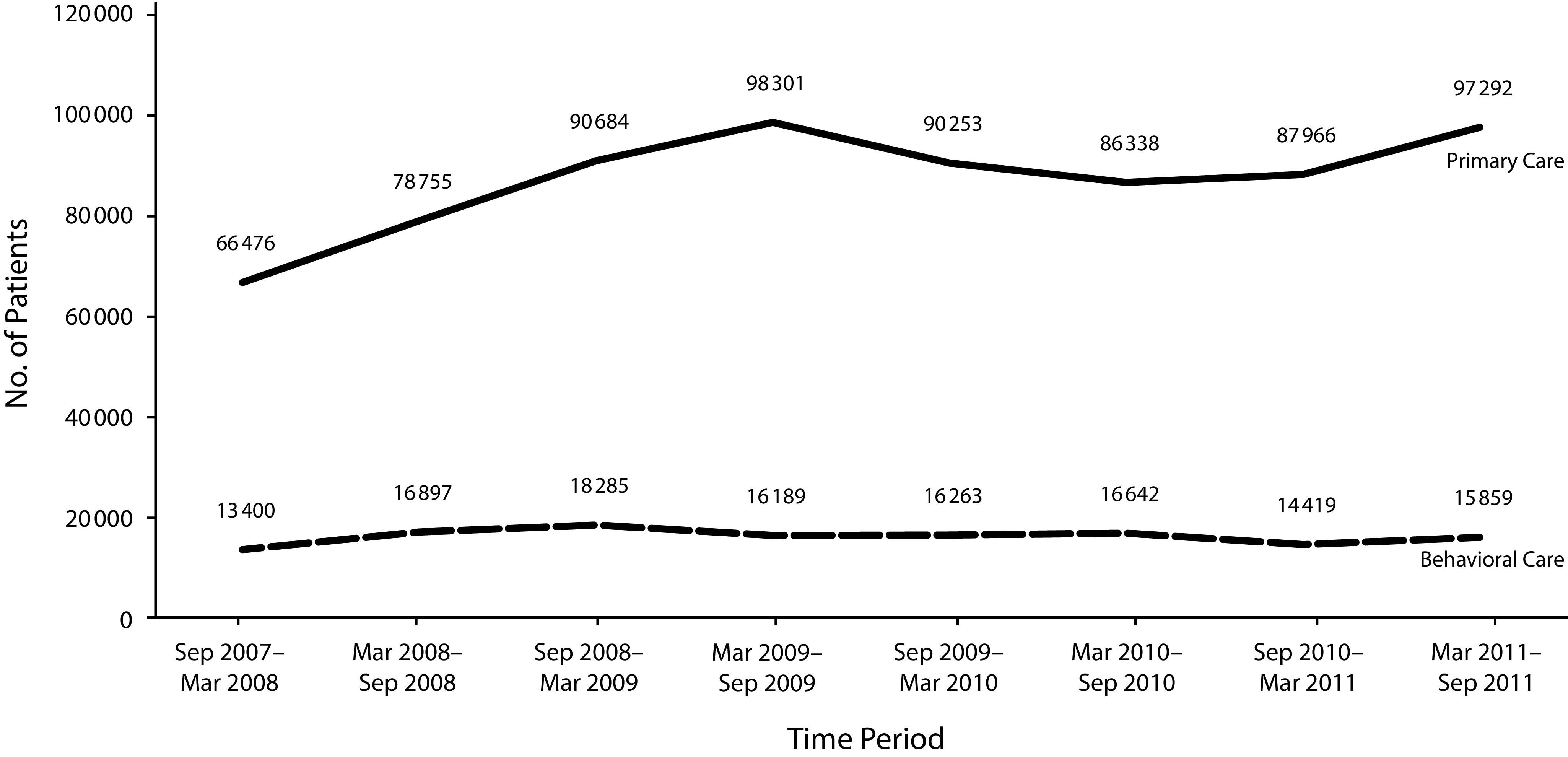

By the end of the PCASG, participating organizations had become an essential source of care for more than 405 000 unduplicated individuals of the region’s population. The PCASG resulted in a steady rise of the number of people served at the awarded grantee practice sites (Figure 1).1

FIGURE 1—

Increases in Patient Volumes in Primary Care Access Stabilization Grant: Louisiana, 2007 to 2011

As clinics reached the end of their PCASG funds, there was a decline in the number of patients served. In 2010, after the Greater New Orleans Community Health Connection was established (see the “Sustainability” section), the number of patients seen increased again. By the end of the PCASG, a majority of individuals seen in PCASG-participating organizations were uninsured (44%), covered by Medicaid (24%), or privately insured (14%).1 As a result of PCASG funding, progress was made in developing a higher quality community-based health care system.6 Individuals served in the PCASG network reported greater access to high-quality health care and more confidence in their health care providers than do most US adults.5

ADVERSE EFFECTS

The PCASG funded most of the services delivered by the PCASG-participating organizations, and the individuals served remained uninsured. “Implementing new models of care became a second-tier priority after simply keeping the clinics doors open.”6(p1736) This suggests that without Medicaid expansion this investment initially doubled down on what was a two-tiered system of health care delivery statewide. Today, that infrastructure is largely being used as part of what is envisioned to be a unified health care ecosystem serving all populations; however, in many places there is still a two-tiered system based on who is willing to accept Medicaid beneficiaries. Some of this is driven by the same reimbursement challenges felt nationwide, but the historical comfort with a two-tiered system in Louisiana, which this work unintentionally reinforced, has meant there is less urgency felt about the need to address this issue.

SUSTAINABILITY

Today, 504HealthNet, a local membership and advocacy organization, supports most of the PCASG-participating organizations that remain. As a result of PCASG network outcomes, in August 2010 Louisiana applied and was approved for a CMS 1115 demonstration waiver to create the Greater New Orleans Community Health Connection, which expanded insurance coverage to the area’s residents aged 19 to 64 years.1 The Greater New Orleans Community Health Connection was intended to bridge funding to Louisiana’s 2016 statewide Medicaid expansion, which to date has provided coverage for nearly a half million previously ineligible Louisiana residents, more than 110 000 of whom reside in the GNO area, according to the Louisiana Department of Health.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

The PCASG investments were significant for public health, locally and nationally, and acted as a catalyst to sustain these services for the region’s residents and funding to community-based health care organizations. Studies conducted on the cost and effectiveness of the PCASG-participating organizations that became the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s patient-centered medical homes can be used to guide policy to support public health and health systems transformation efforts across the country.6,7 The PCASG program offers the following lessons learned to state and local jurisdictions that have experienced a disaster: the importance of (1) policy and advocacy efforts, (2) cross-sector and public–private partnerships, and (3) using grant funding to create enduring health care systems infrastructure to support the health of all residents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Primary Care Access Stabilization Grant (PCASG; grant 1M0CMS030175/01) was funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (June 2007–September 2011) and awarded to the Louisiana Department of Health with the Louisiana Public Health Institute as the local partner.

To our knowledge, this article has never before been published. Data were originally presented in the PCASG final report and accomplishments document produced by the Louisiana Public Health Institute, were made available online, and have been cited in this article.

We are grateful to our partners who still work to achieve health equity for our residents through their current initiatives, and we would like to acknowledge the local, state, and national partners who worked tirelessly to support the PCASG program, including but certainly not limited to the leadership of the PCASG-participating organizations, the Louisiana Department of Health (formerly known as the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals), the City of New Orleans Leadership, the Louisiana Public Health Institute Leadership and PCASG Project Team, the Commonwealth Fund, the Kaiser Family Foundation, and Louisiana Health Care Redesign Collaborative Participants. We have learned many lessons as we respond to the COVID-19 pandemic from the foundation that was laid by this program after Hurricane Katrina.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Primary Care Access and Stabilization Grant Final Report. Public–Private Partnerships Working Together to Recover, Strengthen and Expand Medical Homes for the People of New Orleans. New Orleans, LA: Louisiana Public Health Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.A New Model for the Primary Care Safety Net: Accomplishments From the Greater New Orleans Primary Care Access and Stabilization Grant. New Orleans, LA: Louisiana Public Health Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeSalvo KB, Sachs BP, Hamm LL. Healthcare infrastructure in post-Katrina New Orleans: a status report. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336(2):197–200. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181813332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillam M, Fischbach S, Wolf L, Azikiwe N, Tegeler P. After Katrina: rebuilding a healthier New Orleans. Final conference report of the New Orleans Health Disparities Initiative. 2007. Available at: https://www.prrac.org/pdf/rebuild_healthy_nola.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

- 5.Doty MM, Abrams MK, Mika S, Rustgi S, Lawlor G. Coming out of crisis: patient experiences in primary care in New Orleans, four years post-Katrina: findings from the Commonwealth Fund 2009 Survey of Clinic Patients in New Orleans. 2010. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2010_jan_coming_out_of_crisis_1354_doty_coming_out_of_crisis_new_orleans_clinics.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- 6.Rittenhouse DR, Schmidt LA, Wu KJ, Wiley J. The post-Katrina conversion of clinics in New Orleans to medical homes shows change is possible, but hard to sustain. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1729–1738. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shao H, Brown L, Diana ML et al. Estimating the costs of supporting safety-net transformation into patient-centered medical homes in post-Katrina New Orleans. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(39):e4990. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]