Abstract

This pilot study evaluated nutritional status and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) outcomes among head and neck cancer (HNC) outpatients. Data were collected from 19 patients (18 males, 1 female) during three time-points, i.e., once before chemoradiotherapy (CRT) initiation, and 1 and 3 months after CRT. Nutritional status was evaluated using the Scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA©). Malnutrition was defined as PG-SGA Stage B (moderate/suspected malnutrition) or Stage C (severely malnourished). HRQOL was assessed through the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) and its HNC-specific module (QLQ-H&N35). We found that well-nourished patients reported having fewer issues with pain, fatigue, appetite loss, chewing, sticky saliva, coughing, and social eating than those categorized as malnourished (P < 0.05). The association between the global quality of life score and PG-SGA score was statistically significant but weak in strength (r = −0.37, P = 0.012). While PG-SGA identified 70% as either moderately or severely malnourished before treatment initiation, the mean body mass index was in the overweight category (29 ± 5 kg/m2). Compared to pre-treatment, patients reported more severe problems with chewing, swallowing, sticky saliva, dry mouth, speech, social eating, and taste and smell sensations at 1-month follow-up, although issues with dry mouth persisted 3 months post-treatment (P = 0.003). In conclusion, malnourished patients reported having worse HRQOL symptoms compared to well-nourished. Routine nutritional and psychosocial assessment through PG-SGA and EORTC tools might help identify patients in need of nutritional and psychosocial care.

Keywords: malnutrition, head and neck cancer, nutrition station, PG-SGA, quality of life

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) patients are at a high risk of becoming malnourished. An estimated 35% - 60% are reported to be malnourished already at the time of diagnosis.1 Treatment-related side-effects such as dry mouth, decreased appetite, and difficulties with chewing and swallowing compromise oral intake, leading to significant weight loss and malnutrition.2–4 Within the US, malnutrition still goes unrecognized by the clinicians and is associated with longer hospital length of stay and higher morbidity, mortality, and health care costs.5,6

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) assesses patient’s physical, psychological, social, and emotional functioning from their own experience and perspective, therefore identifying individuals who might benefit from clinical interventions.7–9 Prospective studies among HNC patients have shown an association between nutritional status and HRQOL outcomes. For example among oropharyngeal cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy (RT), malnourished patients reported having worse quality of life (QOL) symptoms than well-nourished.10 In another observation, HNC patients who had lost ≥10% body weight in the past 6 months reported having poor HRQOL during treatment and 6 months after the treatment period.11

Although research has shown that malnutrition negatively affects HRQOL,9–14 these data are limited within the US. First, HRQOL outcomes are not evaluated on a regular basis in cancer centers due to a lack of resources and/or personnel assisting with QOL assessment.9,12 Secondly, there are inconsistencies in nutritional screening and assessment practices among outpatient treatment centers within the US and consults with registered dietitians (RDs) are either lacking or dependent on referral. Within the US, while The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations mandates that hospitalized patients be screened for nutritional risk within 24-hours of admission, currently, no clear nutrition screening standards exist for outpatient care centers.15 In some other countries including the Netherlands, Australia, and Canada, nutrition services are more integrated with cancer care and evidence-based oncology guidelines require or recommend routine consultations with RDs.16 Nonetheless, the effectiveness of nutritional counseling and therapy on clinical outcomes has yielded mixed results17 and malnutrition continues to be a global health concern.18–20

Given a lack of knowledge in how nutritional status relates to QOL outcomes within the US, the aim of this prospective exploratory pilot study was to: 1) evaluate the association between malnutrition and HRQOL among advanced HNC outpatients undergoing chemoradiotherapy (CRT), and 2) assess any longitudinal trends in nutritional status and HRQOL up to three months after CRT.

Materials and Methods

Design

This was an observational prospective longitudinal study design. Nineteen outpatients with HNC intending to undergo treatment with chemoradiotherapy (CRT) at Masonic Cancer Clinic and Radiation Oncology Clinic at the University of Minnesota (UMN) were enrolled. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years and a primary diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, or maxillary sinuses. Patients with a history of recurrent disease and/or comorbidities that may influence body weight, including organ failure and uncontrolled hypertension were excluded.

Data were collected when patients were attending their routine clinic appointments and follow-up visits during the following three time-points: within 7 days prior to starting CRT (baseline) and 1 month and 3 months after treatment. The Institutional Review Board and Cancer Protocol Review Committee at the UMN approved the study. Data were entered and managed using the REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the UMN.

In this study, data were collected on nutritional status but the nutritional intervention was not provided based on our findings at any given time-point. Outside the study procedures as part of routine outpatient care, dietitian referrals were provided by oncologists, ear, nose, and throat (ENT) physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, usually once before treatment initiation to educate patients about beginning enteral nutrition support (ENS). However, it was not standard of care to be seen by an RD routinely during CRT treatment, and any future appointments with RDs were directed by clinician referrals based on their judgment if the patient is losing significant body weight or having dysphagia from mucositis. Information about RD referral and how many patients saw an RD for nutritional counseling or therapy within or outside the clinic was not collected during the course of the study.

Outside the study procedures, patients were also seen by speech-language pathologists (SLPs). SLPs did not follow patients weekly while on therapy at the current treatment center. SLPs were more aligned with the ENT surgery team and saw patients along with ENT surgeons before treatment initiation, occasionally in the middle of CRT, and six weeks after treatment completion. The SLPs assessed speech and swallow evaluation and provided recommendations on swallowing exercises and on the types of foods patients could eat. However, thorough nutritional counseling and discrete nutrition recommendations were not provided by SLPs.

Health-related Quality of Life (HRQOL)

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) (version 3.0) and its head and neck cancer-specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) were used to assess HRQOL.21 These tools assess multiple QOL domains, and data are self-reported by the patients. Research has shown these measures to be reliable and valid for use among HNC patients.21–23

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a 30-item questionnaire with one global health status scale (global QOL), five multi-item functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social), three multi-item symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and pain), and six single-item measures (dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulties).

The EORTC QLQ-H&N35 is a 35-item questionnaire assessing symptoms and side effects of treatment, social function, and body image/sexual issues. It consists of seven multi-item scales (pain, swallowing, sense of taste and smell, speech, social eating, social contact, and sexual function) and eleven single-item measures (teeth problems, issues with opening mouth, dry mouth, sticky saliva, coughing, feeling ill, use of pain killers, nutritional supplements, feeding tube use, weight loss, and weight gain).

Since the EORTC does not assess chewing issues, the following three questions were asked in addition14: 1) How much difficulty did you experience while eating solid food (like meat/hard bread)? 2) How much difficulty did you experience while eating dry food (like cookies)? 3) How much difficulty did you experience while eating soft food (like soft bread)?

Using the EORTC Group scoring guidelines,24 each scale and single-item was scored from 0 – 100. Higher scores in the global QOL or functional scales implied better QOL or function; higher scores in the symptom scales/items indicated worsening of symptoms. Chewing-related symptoms were assessed using the EORTC guidelines; higher scores suggested more issues with chewing.

Malnutrition

Malnutrition was assessed during all time points using the Scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA©, 1996 FD Ottery).25 The patient component of the PG-SGA includes four boxes addressing weight history, food intake, nutrition impact symptoms, and activities and function. The professional component of the PG-SGA includes five worksheets, addressing scoring of weight loss, disease and its relation to nutritional requirements, metabolic demand, physical examination, and PG-SGA Global Assessment category rating.26 Patients were rated as being well-nourished (PG-SGA A), moderate/suspected malnutrition (PG-SGA B), or severely malnourished (PG-SGA C). Subsequently, nutritional status was dichotomized into well-nourished or malnourished categories.

Based on the scores from all boxes and worksheets, a total numerical PG-SGA score was calculated.26 PG-SGA scores between 4 – 8 points require intervention by an RD in conjunction with a nurse or physician as indicated by the nutrition impact symptoms, while scores ≥9 imply a critical need for improved symptom management and/or nutrition intervention.26

Statistical Analysis

Clinical and demographic characteristics were summarized as frequencies (percent) for categorical covariates and means ± standard deviations for continuous variables. Pearson’s correlation examined the association between variables. One-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed to assess changes in mean EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35 scores over time (i.e., before treatment, 1- and 3-months post-treatment). A post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni’s adjustment was done for multiple pairwise comparisons.

To investigate whether or not malnutrition had any effect on HRQOL scores, nutritional status was included as a covariate in a repeated measures model adjusted for time period and within-subject interdependence was accounted. Here, the coefficient estimate (CE) and standard error of the estimate (SE) evaluated how the mean PG-SGA and EORTC scores differ between malnourished and well-malnourished participants.

Significance level was set at P ≤ 0.05. Data were analyzed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Figure was constructed using GraphPad Prism version 8.2.1 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Baseline data are presented in Table 1. All patients identified themselves as Caucasian; 18 were male and 1 female, mean age was 59 ± 7 years. Fifteen (79%) were diagnosed with Stage IV cancer and four (21%) had Stage III cancer. Most tumors were localized at the oropharynx (58%) and oral cavity (16%). Mean body mass index was 29 ± 5 kg/m2; 74% were categorized as either overweight or obese. Thirteen (68%) underwent tumor resection surgery prior to starting CRT.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline (n = 19).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years ± SD) | 59 ± 7 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 18 (95) |

| Female | 1 (5) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2 ± SD) | 29 ± 5 |

| Normal (18.5 – 24.9) | 5 (26) |

| Overweight (25.0 – 29.9) | 6 (32) |

| Obese (≥ 30) | 8 (42) |

| Tumor staging | |

| Stage III | 4 (21) |

| Stage IV | 15 (79) |

| Primary tumor site | |

| Oropharynx | 11 (58) |

| Oral cavity | 3 (16) |

| Larynx | 2 (11) |

| Maxillary sinuses | 2 (11) |

| Paranasal sinuses | 1 (5) |

| Surgery* | 13 (68) |

Participants who had tumor resection surgery prior to beginning their treatment.

Forty-seven independent study visits were completed, and ten data points were missing. Reasons for missed visits included declining to further participate in the study procedures after the first visit for one participant, four no-show appointments, and three individuals who died during the course of the study because of disease-related complications.

Nutrition Status and Health-related Quality of Life (HRQOL)

Nutritional status and HRQOL symptoms were evaluated for all observations across all time points (Table 2). After accounting for within-subject correlations and adjusting for time-period, the PG-SGA score for well-nourished patients was on average 7.6 points lower than for the malnourished (SE = 1.2, P < 0.001). The global QOL score for well-nourished patients was 14.5 points higher than for the malnourished (SE = 5.0, P = 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Nutritional status and quality of life estimates* for well-nourished patients (n = 7) (PG-SGA A) compared to malnourished patients (PG-SGA B or C) (n = 40) for all observations across all time-points.

| Variable | Coefficient Estimate | Standard Error | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PG-SGA score | −7.6 | 1.2 | <0.001 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | |||

| Global QOL | 14.5 | 5.0 | 0.01 |

| Functional scales | |||

| Physical functioning | 1.1 | 4.2 | 0.80 |

| Role Functioning | 6.5 | 11.0 | 0.56 |

| Emotional functioning | 4.5 | 5.9 | 0.45 |

| Cognitive functioning | 13.4 | 6.9 | 0.07 |

| Social functioning | 12.5 | 7.7 | 0.12 |

| Symptom scales/Items | |||

| Fatigue | −26.5 | 10.2 | 0.02 |

| Nausea and vomiting | −7.7 | 5.5 | 0.18 |

| Pain | −29.7 | 10.1 | 0.01 |

| Dyspnea | 9.8 | 7.4 | 0.21 |

| Insomnia | −11.6 | 9.6 | 0.24 |

| Appetite loss | −34.3 | 11.1 | 0.01 |

| Constipation | 4.1 | 9.4 | 0.66 |

| Diarrhea | −13.9 | 7.4 | 0.08 |

| Financial difficulties | −5.2 | 9.9 | 0.61 |

| QLQ-H&N35 | |||

| Pain | −11.0 | 8.6 | 0.21 |

| Swallowing | −8.3 | 5.5 | 0.15 |

| Senses problems | −3.4 | 13.8 | 0.81 |

| Speech problems | −3.2 | 5.4 | 0.56 |

| Trouble with social eating | −19.7 | 8.1 | 0.03 |

| Trouble with social contact | −1.8 | 3.9 | 0.64 |

| Sex interest | −22.8 | 12.5 | 0.08 |

| Teeth problems | −5.7 | 7.3 | 0.44 |

| Trouble opening mouth wide | 5.3 | 10.9 | 0.63 |

| Dry mouth | −17.3 | 8.9 | 0.07 |

| Sticky saliva | −32.1 | 10.4 | 0.01 |

| Coughing | −18.4 | 7.6 | 0.03 |

| Felt ill | −20.9 | 8.1 | 0.02 |

| Pain killers | −51.9 | 14.7 | 0.002 |

| Nutritional supplements | −60.3 | 19.5 | 0.01 |

| Feeding tube | −53.3 | 20.9 | 0.02 |

| Weight loss | −55.5 | 19.5 | 0.01 |

| Weight gain‡ | - | - | - |

| Chewing problems¶ | −30.5 | 11.9 | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: EORTC QLQ, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; PG-SGA, Scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment; QLQ-H&N35, Head and neck cancer-specific module; QOL, Quality of life

The Coefficient Estimate evaluated how mean PG-SGA and QOL scores differed between well-nourished and malnourished participants.

Scale assessing problems with chewing is not included in the QLQ-H&N35.

Insufficient data to calculate the estimate.

Compared to malnourished, well-nourished patients reported having less pain (P = 0.01) and fatigue (P = 0.02), and fewer issues with appetite loss (P = 0.01), chewing (P = 0.02), coughing (P = 0.03), sticky saliva (P = 0.01), and social eating (P = 0.03). Malnourished patients reported more weight loss (P = 0.01), felt ill (P = 0.02), and using more pain killers (P = 0.002), nutritional supplements (P = 0.01), and feeding tube (P = 0.02) than well-nourished (Table 2). The association between global QOL score and PG-SGA score was statistically significant but weak in strength (r = −0.37, P = 0.012).

Longitudinal Changes

PG-SGA categorized 68% (13/19) as either moderate/suspected malnutrition (PG-SGA B, 11/19) or severely malnourished (PG-SGA C, 2/19) before CRT initiation (baseline). One-month post-treatment, all patients were categorized as malnourished and 92% (12/13) remained malnourished 3 months post-treatment period.

Compared to pre-treatment, PG-SGA scores increased at 1-month post-treatment period (8 ± 4 vs. 13 ± 4, P = 0.01) (Table 3). Before treatment,42% (8/19) had PG-SGA scores requiring RD intervention (i.e., between 4 – 8 points) while 37% (7/19) scored ≥9, indicating a critical need for improved symptom management and/or nutrition intervention (Table 3). One month after treatment, 20% (3/15) had PG-SGA scores between 4 – 8 points, while 80% (12/15) scored ≥9; three months after treatment completion, 8% (1/13) scored between 4 – 8 points and 92% (12/13) had PG-SGA scores ≥9. Body weight (kg) and BMI (kg/m2) decreased from baseline to post-treatment time points, with the largest average reductions of 7 kg and 2 kg/m2, respectively, between baseline and 1 month after treatment.

Table 3:

| Variable | Before treatment (n = 19) | 1-month post-treatment (n = 15) | 3-months post-treatment (n = 13) | P-value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG-SGA score | 8 ± 4 | 13 ± 4§ | 12 ± 4§ | 0.001 |

| PG-SGA score 4–8, (n) % | 8 (42) | 3 (20) | 1 (8) | |

| PG-SGA score ≥ 9, (n) % | 7 (37) | 12 (80) | 12 (92) | |

| Body weight (kg) | 93 ± 23 | 86 ± 20§ | 88 ± 21§ | 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29 ± 5 | 27 ± 4§ | 27 ± 5§ | < 0.001 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | ||||

| Global QOL | 66 ± 17 | 69 ± 15 | 65 ± 16 | 0.73 |

| Functional scales | ||||

| Physical functioning | 83 ± 26 | 86 ± 13§ | 83 ± 21 | 0.01 |

| Role functioning | 66 ± 34 | 72 ± 26 | 65 ± 25 | 0.37 |

| Emotional functioning | 79 ± 15 | 80 ± 12 | 75 ± 14 | 0.58 |

| Cognitive functioning | 87 ± 16 | 86 ± 18 | 82 ± 20 | 0.13 |

| Social functioning | 68 ± 20 | 73 ± 22 | 64 ± 21 | 0.48 |

| Symptom scales/items | ||||

| Fatigue | 35 ± 26 | 40 ± 13 | 38 ± 20 | 0.61 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 6 ± 13 | 16 ± 25 | 14 ± 16 | 0.17 |

| Pain | 32 ± 28 | 23 ± 24 | 21 ± 24 | 0.36 |

| Dyspnea | 11 ± 22 | 13 ± 17 | 21 ± 26 | 0.06 |

| Insomnia | 33 ± 22 | 29 ± 25 | 26 ± 20 | 0.49 |

| Appetite loss | 33 ± 29 | 47 ± 28 | 46 ± 29 | 0.29 |

| Constipation | 16 ± 23 | 20 ± 17 | 15 ± 17 | 0.31 |

| Diarrhea | 7 ± 18 | 11 ± 16 | 10 ± 16 | 0.53 |

| Financial difficulties | 28 ± 28 | 20 ± 17 | 21 ± 22 | 0.40 |

| QLQ-H&N35 | ||||

| Pain | 25 ± 19 | 31 ± 17 | 24 ± 25 | 0.43 |

| Swallowing problems | 16 ± 18 | 27 ± 27§ | 19 ± 18 | 0.02 |

| Trouble smelling or tasting | 27 ± 35 | 50 ± 28§ | 42 ± 22 | 0.03 |

| Speech problems | 18 ± 23 | 29 ± 27§ | 19 ± 25 | 0.01 |

| Trouble eating socially | 19 ± 23 | 36 ± 25§ | 31 ± 28 | 0.03 |

| Trouble with social contact | 9 ± 9 | 18 ± 22 | 14 ± 13 | 0.09 |

| Sex interest | 22 ± 29 | 31 ± 33 | 28 ± 28 | 0.60 |

| Teeth problems | 14 ± 28 | 5 ± 13 | 13 ± 29 | 0.30 |

| Trouble opening mouth wide | 21 ± 34 | 22 ± 27 | 13 ± 17 | 0.78 |

| Dry mouth | 18 ± 23 | 47 ± 21§ | 49 ± 22§ | 0.003 |

| Sticky saliva | 21 ± 34 | 58 ± 29§ | 38 ± 23 | 0.002 |

| Coughing | 30 ± 19 | 40 ± 29 | 33 ± 27 | 0.65 |

| Felt ill | 14 ± 20 | 22 ± 21 | 23 ± 25 | 0.37 |

| Pain killers | 74 ± 45 | 80 ± 41 | 62 ± 51 | 0.70 |

| Nutritional supplements | 42 ± 51 | 73 ± 46 | 69 ± 48 | 0.11 |

| Feeding tube | 37 ± 50 | 73 ± 46 | 38 ± 51 | 0.06 |

| Weight loss | 58 ± 51 | 33 ± 49 | 46 ± 52 | 0.29 |

| Weight gain | 0 | 20 ± 41 | 23 ± 44 | 0.07 |

| Chewing problems¶ | 30 ± 33 | 57 ± 27§ | 52 ± 26 | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: EORTC QLQ, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; PG-SGA, Scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment; QLQ-H&N35, Head and neck cancer-specific module; QOL, Quality of life

Higher scores in the global QOL and functional scales indicates better QOL or functioning, respectively; higher scores in the symptom scales (or single items) implies worsening of symptoms.

Values are mean ± standard deviation unless specified otherwise.

Analyzed by one-way repeated measures ANOVA, composite P-values.

Per the Bonferroni post-hoc test, pairwise comparison significant compared to before treatment.

Scale assessing problems with chewing is not included in the QLQ-H&N35.

Of the 19 patients, 18 (95%) underwent a prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement procedure prior to beginning their treatment. Nutritional intake included oral diet and supplements and enteral nutrition support (ENS) feedings. Before treatment, 11% (2/19) were using ENS feedings, one month after treatment, 73% (11/15) were on ENS, while 46% (6/13) continued receiving ENS at the 3-month post-treatment mark.

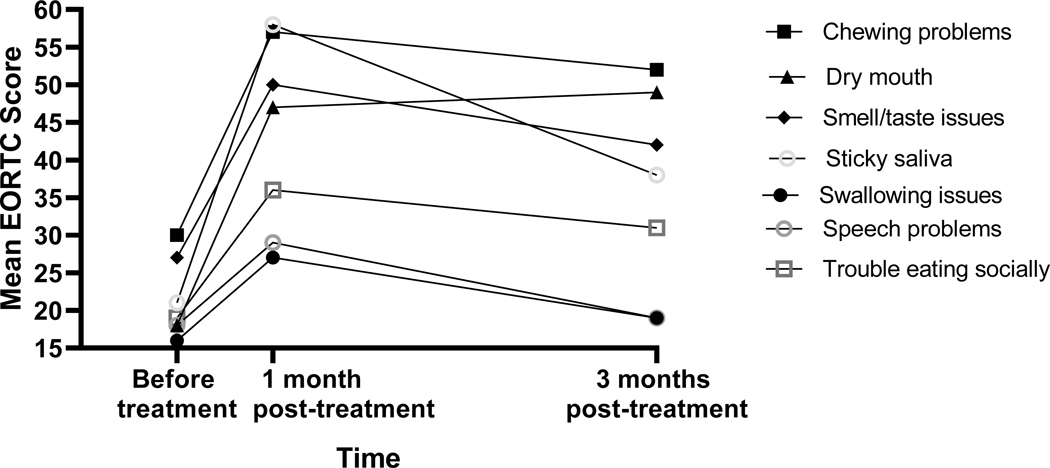

Physical functioning assessed by QLQ-C30 was lower at baseline compared to 1-month post-treatment period (83 ± 26 vs. 86 ± 13, P = 0.007) (Table 3). Compared to pre-treatment, severe problems with chewing (P = 0.02), swallowing (P = 0.02), sticky saliva (P = 0.002), speech (P = 0.01), social eating (P = 0.03), and taste and smell sensations (P = 0.03) were reported at 1-month follow-up in the QLQ-H&N35 (Table 3, Figure). Issues with dry mouth persisted both at 1-month and 3-month follow-up (P = 0.007 and P = 0.003, respectively) (Table 3).

Figure:

Changes in nutrition-impact symptoms across time as indicated by EORTC QLQ-H&N35.

Discussion

The results from this exploratory pilot study indicate an association between malnutrition and HRQOL in a cohort of advanced HNC patients. Malnourished patients reported having worse HRQOL when compared to those well-nourished. Longitudinally, poor HRQOL was reported at 1 month post-treatment period, although most symptoms improved 3 months post-treatment with the exception of dry mouth. While 70% of our sample was identified as either moderately or severely malnourished before treatment initiation, mean BMI was in the overweight category (29 ± 5 kg/m2) and 74% were classified as either overweight or obese. Thus, body weight and BMI are poor predictors of nutritional status as these may mask malnutrition. Before treatment initiation, 42% had PG-SGA scores between 4 – 8 points, suggesting a need for nutritional intervention by an RD, and 37% scored ≥9, indicating a critical need for improved symptom management and/or nutritional intervention.

Findings from this study highlight the need for regular nutritional and psychosocial assessment. Routine administration of PG-SGA and EORTC tools would help identify patients in need of nutritional and psychosocial care as both tools provide unique data from the patient’s experience and perspective that augments clinician assessment. Recently, the self-administered “PG-SGA Short Form” has been shown to be a feasible and quick (< 5 minutes) method to screen HNC patients for nutritional risk and increase patient awareness of malnutrition.27 Thus, all oncology outpatients must be screened for malnutrition risk and thorough nutrition assessment be conducted by an RD for high-risk patients for appropriate nutritional intervention and symptom management. Indeed, the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Clinical Practice Guidelines28 for adult anticancer treatment recommend regular nutritional screening for patients with cancer. Therefore, it is important to have a dedicated full-time nutrition staff in the outpatient oncology centers within the US.16

Nutrition Status and Health-related Quality of Life

Patients categorized as malnourished by the PG-SGA tool (i.e., PG-SGA B or C) scored lower on the global QOL scale than well-nourished; total PG-SGA score and global QOL score were weakly correlated to each other. Previously in a cohort of cancer patients including HNC, Isenring et al29 also found an association between the PG-SGA and global QOL scores; here, 26% of the variation in global QOL score was explained by a change in the PG-SGA score.

In our study, malnourished patients reported higher EORTC scores on scales/items that were likely to impact oral intake such as fatigue, appetite loss, coughing, sticky saliva, and problems with chewing. Among patients with gastric cancers,30 PG-SGA-identified malnourished patients also scored higher in the EORTC symptom scales, including appetite loss, nausea and vomiting, pain, and insomnia. Taken together, these results suggest an association between malnutrition identified by the PG-SGA tool and HRQOL outcomes.

In the past, treatment modality has also affected nutritional and QOL symptoms. For example, CRT patients have reported more issues with fatigue, nausea and vomiting, appetite loss, and sticky saliva one month after treatment when compared to those receiving RT alone or RT with surgery.31–33 Our cohort had advanced disease and underwent aggressive CRT that could have progressively diminished their QOL. Thus, it is debatable whether the association between nutrition status and HRQOL was mediated by the severity of disease and/or treatment modality rather than suggesting a causal relationship between nutritional and QOL outcomes. Nonetheless, patients have benefited from regular nutritional counseling provided by an RD during various phases of cancer treatment.32,34–36 This is supported by a recent trial where HNC patients receiving RD counseling showed improvements in nutritional status (indicated by lower PG-SGA scores) and body weight, had fewer treatment interruptions, and reported higher HRQOL as measured by EORTC.34

Longitudinal Changes

Longitudinally, deficits in nutrition status were found as measured by the PG-SGA. Almost 70% were categorized as malnourished before treatment initiation, and the PG-SGA score implied a need for intervention by an RD with a mean score of 8 ± 4, with 42% scoring between 4 – 8 points. PG-SGA score was ≥ 9 for most patients after the post-treatment period, suggesting a critical need for symptom management and/or nutrition intervention. Nutritional deficits were also indicated by a decline in body weight and BMI. The largest decline in body weight was found 1-month post-treatment period with an average of 8% weight loss from baseline, indicating a clinically severe loss.

While body weight showed improvements 3 months post-treatment, patients did not regain their pre-treatment weight. An observation in the Netherlands37 found that HNC patients can lose up to 5% of their pre-treatment body weight during treatment, two-thirds of which is lean tissue; interestingly, loss of body weight and lean tissue occurred despite “sufficient” intake of calories (≥35 kcal/kg) and protein (≥1.5 grams/kg). Prevention of weight loss can improve morbidity, mortality, tolerance to cancer treatment, and overall QOL.38,39 Thus, more insights are needed to understand optimal nutrient delivery in cancer to prevent loss of body weight and muscle mass.

When compared to pre-treatment symptoms, patients reported more issues with smelling or tasting, chewing, swallowing, sticky saliva, speech, and social eating one-month post-treatment. Of note, the majority (73%) of patients were using ENS at the one-month post-treatment mark, and malnutrition with compromised oral intake could have contributed to worsening of QOL symptoms at this time-point.

Most symptoms improved at 3 months post-treatment period except dry mouth. While HRQOL significantly declines immediately after HNC treatment, symptoms tend to reach near baseline levels within 12 months post-treatment period with some exceptions.33 More specifically, certain nutritional-impact symptoms including dry mouth, swallowing and chewing problems, and taste and smell issues may continue to hinder intake one year after treatment, and in some cases, these symptoms are less likely to recover even at the 3-year post-treatment mark.8,40,41 Additionally, patient recovery to baseline HRQOL levels does not necessarily imply “better” QOL, as most HNC patients begin treatment with an impaired QOL near baseline.8 Hence, there is benefit in assessing longitudinal HRQOL for timely clinical intervention particularly among HNC patients. 1,3,41,42

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. A small sample size limits the statistical significance of our findings. Our follow-up time of 3 months post-treatment period was also relatively short, given that some HRQOL symptoms might persist several years after cancer diagnosis. Another limitation was missing data because of patient dropouts and deaths which could have introduced bias; over the course of the study we lost one-third of our patients of which 33% were malnourished at baseline. While missing data is a recognized challenge in longitudinal QOL research, several factors have been shown to predict low participation rates including stage IV disease, older age, adjuvant radiation, and poor HRQOL.8 This study also did not track patients who might have received nutritional counseling or therapy by an RD during the course of their treatment, thereby potentially impacting nutritional outcomes and introducing bias in our findings.

Our cohort had advanced disease and underwent aggressive CRT that could have impacted nutritional and HRQOL findings. For instance, research has shown that patients undergoing RT only report lower prevalence of malnutrition and better HRQOL compared to those receiving CRT.33 Therefore studies comparing the effect of various treatment modalities on nutritional and HRQOL outcomes (for example, surgery alone vs. surgery with postoperative CRT or RT; CRT vs. RT alone, etc.) would be informative.

While our results are not generalizable, data are mostly consistent with previous findings in HNC with malnutrition negatively impacting HRQOL and patients reporting worsening of nutrition-impact symptoms as treatment progresses.4,10,33,43 This pilot study provides useful data, but rigorous randomized controlled trials with more patients and longer follow-up periods are specifically warranted within the US.

As mentioned earlier, HRQOL assessment is not routine in care and such data are usually gathered for research purposes.9,44 Similarly, standards for nutritional screening and assessment are not consistent in outpatient care facilities within the US. An important next step would be to integrate outpatient nutritional and HRQOL assessment in clinical practice and identifying dedicated staff members who would help administer these assessments.9,12,45 Doing so, timely identification of patients in need of nutritional and psychosocial care would be possible. This will also help future studies aiming to investigate the effect of nutrition intervention on QOL symptoms and the relation between HRQOL and survival outcomes.46

Acknowledgments

Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000114. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research was also supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and the Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station, Project MIN-18-104, Hatch Funding.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Harriët Jager-Wittenaar is a co-developer of the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA)-based “Pt-Global” app/web tool, a global platform and mobile application used to promote the PG-SGA tool.

References:

- 1.Alshadwi A, Nadershah M, Carlson ER, Young LS, Burke PA, Daley BJ. Nutritional considerations for head and neck cancer patients: a review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(11):1853–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bressan V, Stevanin S, Bianchi M, Aleo G, Bagnasco A, Sasso L. The effects of swallowing disorders, dysgeusia, oral mucositis and xerostomia on nutritional status, oral intake and weight loss in head and neck cancer patients: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;45:105–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bressan V, Bagnasco A, Aleo G, et al. The life experience of nutrition impact symptoms during treatment for head and neck cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(5):1699–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gellrich NC, Handschel J, Holtmann H, Krüskemper G. Oral cancer malnutrition impacts weight and quality of life. Nutrients. 2015;7(4):2145–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vest MT, Papas MA, Shapero M, McGraw P, Capizzi A, Jurkovitz C. Characteristics and outcomes of adult inpatients with malnutrition. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2018;42(6):1009–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tappenden KA, Quatrara B, Parkhurst ML, Malone AM, Fanjiang G, Ziegler TR. Critical role of nutrition in improving quality of care: an interdisciplinary call to action to address adult hospital malnutrition. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(9):1219–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy BA, Ridner S, Wells N, Dietrich M. Quality of life research in head and neck cancer: a review of the current state of the science. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;62(3):251–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rathod S, Livergant J, Klein J, Witterick I, Ringash J. A systematic review of quality of life in head and neck cancer treated with surgery with or without adjuvant treatment. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(10):888–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferlito A, Rogers SN, Shaha AR, Bradley PJ, Rinaldo A. Quality of life in head and neck cancer. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123:5–7 (Editorial). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Citak E, Tulek Z, Uzel O. Nutritional status in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiotherapy: a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(1):239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Berg M, Rasmussen-Conrad E, van Nispen L, van Binsbergen J, Merkx MA. A prospective study on malnutrition and quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2008;44(9):830–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oates J, Clark JR, Read J, Reeves N, Gao K, O’Brien CJ. Integration of prospective quality of life and nutritional assessment as routine components of multidisciplinary care of patients with head and neck cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78(1–2):34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers SN, Ahad SA, Murphy AP. A structured review and theme analysis of papers published on ‘quality of life’ in head and neck cancer: 2000–2005. Oral Oncol. 2007;43(9):843–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jager-Wittenaar H, Dijkstra PU, Vissink A, van der Laan BF, van Oort RP, Roodenburg JL. Malnutrition and quality of life in patients treated for oral oropharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2011;33(4):490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Joint Commission. Provision of Care, Treatment, and Services: Nutritional and Functional Screening - Requirement. https://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/jcfaqdetails.aspx?StandardsFAQId=1604&StandardsFAQChapterId=29&ProgramId=0&ChapterId=0&IsFeatured=False&IsNew=False&Keyword=. Accessed November 11, 2019.

- 16.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Examining Access to Nutrition Care in Outpatient Cancer Centers: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldwin C The effectiveness of nutritional interventions in malnutrition and cachexia. Proc Nutr Soc. 2015;74(4):397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curtis LJ, Bernier P, Jeejeebhoy K, et al. Costs of hospital malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(5):1391–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kruizenga H, Van Keeken S, Weijs P, et al. Undernutrition screening survey in 564,063 patients: Patients with a positive undernutrition screening score stay in hospital 1.4 d longer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(4):1026–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sauer AC, Goates S, Malone A, et al. Prevalence of Malnutrition Risk and the Impact of Nutrition Risk on Hospital Outcomes: Results From nutritionDay in the U.S. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjordal K, De Graeff A, Fayers PM, et al. A 12 country field study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H and N35) in head and neck patients. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(14):1796–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bjordal K, Kaasa S, Mastekaasa A. Quality of life in patients treated for head and neck cancer: a follow-up study 7 to 11 years after radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;28(4):847–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammerlid E, Bjordal K, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, et al. Prospective, longitudinal quality-of-life study of patients with head and neck cancer: a feasibility study including the EORTC QLQ-C30. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116(6):666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual (3rd Edition). 2001; Published by: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Brussels. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ottery F Definition of standardized nutritional assessment and interventional pathways in oncology. Nutrition. 1996;12(1):S15–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jager-Wittenaar H, Ottery FD. Assessing nutritional status in cancer: role of the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2017;20(5):322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jager-Wittenaar H, de Bats HF, Welink-Lamberts BJ, et al. Self-Completion of the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment Short Form Is Feasible and Is Associated With Increased Awareness on Malnutrition Risk in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. Nutr Clin Pract. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.August DA, Huhmann MB. American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) Board of Directors. ASPEN clinical guidelines: nutrition support therapy during adult anticancer treatment and in hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2009;33(5):472–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isenring E, Bauer J, Capra S. The scored Patient-generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) and its association with quality of life in ambulatory patients receiving radiotherapy. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(2):305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Correia M, Cravo M, Marques-Vidal P, et al. Serum concentrations of TNF-alpha as a surrogate marker for malnutrition and worse quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. Clin Nutr. 2007;26(6):728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Leeuw J, van den Berg MGA, van Achterberg T, Merkx MA. Supportive care in early rehabilitation for advanced-stage radiated head and neck cancer patients. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(4):625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiss NK, Krishnasamy M, Loeliger J, Granados A, Dutu G, Corry J. A dietitian-led clinic for patients receiving (chemo)radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(9):2111–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein J, Livergant J, Ringash J. Health related quality of life in head and neck cancer treated with radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy: a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(4):254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Britton B, Baker AL, Wolfenden L, et al. Eating As Treatment (EAT): A Stepped-Wedge, Randomized Controlled Trial of a Health Behavior Change Intervention Provided by Dietitians to Improve Nutrition in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer Undergoing Radiation Therapy (TROG 12.03). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;103(2):353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van den Berg MG, Rasmussen-Conrad EL, Wei KH, Lintz-Luidens H, Kaanders JH, Merkx MA. Comparison of the effect of individual dietary counselling and of standard nutritional care on weight loss in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiotherapy. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(6):872–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langius JA, Zandbergen MC, Eerenstein SE, et al. Effect of nutritional interventions on nutritional status, quality of life and mortality in patients with head and neck cancer receiving (chemo) radiotherapy: a systematic review. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(5):671–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jager-Wittenaar H, Dijkstra PU, Vissink A, et al. Changes in nutritional status and dietary intake during and after head and neck cancer treatment. Head Neck. 2011;33(6):863–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langius JA, van Dijk AM, Doornaert P, et al. More than 10% weight loss in head and neck cancer patients during radiotherapy is independently associated with deterioration in quality of life. Nutr Cancer. 2013;65(1):76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petruson KM, Silander EM, Hammerlid EB. Quality of life as predictor of weight loss in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2005;27(4):302–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammerlid E, Silander E, Hörnestam L, Sullivan M. Health-related quality of life three years after diagnosis of head and neck cancer--a longitudinal study. Head Neck. 2001;23(2):113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jager-Wittenaar H, Dijkstra PU, Vissink A, van Oort RP, van der Laan BF, Roodenburg JL. Malnutrition in patients treated for oral or oropharyngeal cancer-prevalence and relationship with oral symptoms: an explorative study. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(10):1675–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kubrak C, Olson K, Jha N, et al. Clinical determinants of weight loss in patients receiving radiation and chemoirradiation for head and neck cancer: a prospective longitudinal view. Head Neck. 2013;35(5):695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loorents V, Rosell J, Willner HS, Börjeson S. Health-related quality of life up to 1 year after radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer (HNC). SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sayed SI, Elmiyeh B, Rhys-Evans P, et al. Quality of life and outcomes research in head and neck cancer: a review of the state of the discipline and likely future directions. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35(5):397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oates JE, Clark JR, Read J, et al. Prospective evaluation of quality of life and nutrition before and after treatment for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(6):533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Nieuwenhuizen AJ, Buffart LM, Brug J, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. The association between health related quality of life and survival in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]