Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) is a viable technique for management of non-compressible torso hemorrhage. The major limitation of the current unilobed fully-occlusive REBOA catheters is below-the-balloon ischemia-reperfusion complications. We hypothesized that partial aortic occlusion with a novel bilobed partial (p)REBOA-PRO would result in the need for less intra-aortic balloon adjustments to maintain a distal goal perfusion pressure as compared to currently available unilobed ER-REBOA.

METHODS:

Anesthetized (40–50 kg) swine randomized to control (no intervention), ER-REBOA or pREBOA-PRO underwent supraceliac aortic injury. REBOA groups underwent catheter placement into Zone 1 with initial balloon inflation to full occlusion for 10 minutes followed by gradual deflation to achieve and subsequently maintain half of the baseline below-the-balloon mean arterial pressure (MAP). Physiologic data and blood samples were collected at baseline and then hourly. At 4 hours, the animals were euthanized, total blood loss and urine output were recorded, and tissue samples were collected.

RESULTS:

Baseline physiologic data and basic labs were similar between groups. Compared to control, interventions similarly prolonged survival from a median of 18 to over 240 minutes with comparable mortality trends. Blood loss was similar between partial ER-REBOA (41%) and pREBOA-PRO (51%). Partial pREBOA-PRO required a significantly lower number of intra-aortic balloon adjustments (10 ER-REBOA vs. 3 pREBOA-PRO, p<0.05) to maintain the target below-the-balloon MAP. The partial ER-REBOA group developed significantly increased hypercapnia, fibrin clot formation on TEG, liver inflammation and IL-10 expression compared to pREBOA-PRO.

CONCLUSIONS:

In this highly lethal aortic injury model, use of bilobed pREBOA-PRO for a 4-hour partial aortic occlusion was logistically superior to unilobed ER-REBOA. It required less intra-aortic balloon adjustments to maintain target MAP and resulted in less inflammation.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE:

Not applicable, translational randomized animal study.

Keywords: resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta, partial REBOA, non-compressible truncal hemorrhage, hemorrhage control, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Hemorrhage continues to be the leading cause of preventable death after trauma.1,2 Non-compressible torso hemorrhage is particularly difficult to manage with a significant pre-hospital mortality rate as high as 85.5%.3–6 Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) catheter technology has emerged as a less invasive alternative to thoracotomy and aortic clamping, for rapid control of below-the-balloon hemorrhage and re-establishment of perfusion to above-the-balloon tissues.7,8 This percutaneous approach can be performed proactively in the field by a well-trained physician.7,9–12 However, similar to an aortic clamp, prolonged maintenance of fully-occlusive REBOA is associated with significant complications due to supraphysiologic above-the-balloon blood pressures and below-the-balloon tissue ischemia.9,13 Thus, partial and intermittent REBOA have been proposed as strategies to allow hemorrhage control while mitigating below-the-balloon ischemia;14 with newest reports highlighting the importance of continuous over intermittent below-the-balloon perfusion.15

Studies evaluating partial REBOA have demonstrated that compared to fully-occlusive REBOA, partial aortic occlusion dampens above-the-balloon hypertension, produces less below-the-balloon ischemia and dampens rebound hypotension during deflation of the balloon.9,11,16 While some skilled physicians are gaining confidence with individual versions of partial REBOA,17 no official guidelines for establishment, maintenance or termination of partial REBOA currently exist. Moreover, it has been shown that even with a protocolized balloon volume adjustment and termination, use of currently available unilobed ER-REBOA provides an unpredictable pattern of onset of initial aortic flow, number of deflation steps, increases in below-the-balloon aortic flow and above-the-balloon mean arterial pressure (MAP), which points to complexity of vascular responses and blood flow dynamics.18 A novel bilobed REBOA (pREBOA-PRO) technology holds promise for a better partial aortic occlusion control, with strides19 to attain a better balance between hemorrhage control and below-the-balloon ischemia.

The goal of this study was to compare the logistic requirements of the novel bilobed pREBOA-PRO vs. the currently available unilobed ER-REBOA to reliably establish and maintain a state of partial aortic occlusion after a highly lethal aortic injury. Our hypothesis was that the number of volume adjustments required to maintain partial occlusion and variation of below-the-balloon MAP from a target MAP will be lower in the pREBOA-PRO without effect on survival or blood loss. Secondary endpoints included changes in physiologic parameters, levels of markers of ischemia, inflammation and end organ injury in circulation and end-point tissue samples. The study was designed to further test use of partial REBOA for four hours to replicate scenarios where definitive care is delayed.12,20–22

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview

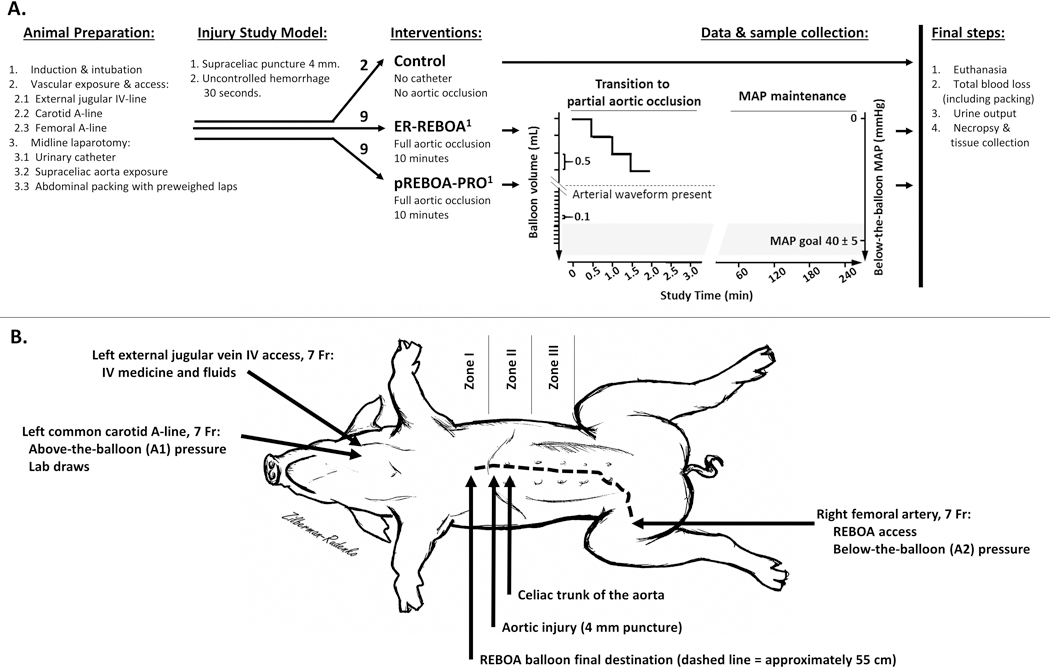

This study was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). All work pertaining to the animals was in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. This study utilized 40–50 kg female Yorkshire swine sourced from a single supplier and acclimated for a minimum of 4 days under veterinary service oversight. Protocol stages are depicted in Figure 1A and described below.

Figure 1: Experimental set up.

(A) Graphic representation of the experimental protocol, where 1-denotes catheter inserted through the right femoral introducer and advanced under direct palpation until the balloon was confirmed above the level of the diaphragm in Zone 1. All study groups received 1000 mL of Lactated Ringer’s during the intervention and a 5 mL/kg/hr rate of maintenance fluids during MAP maintenance stage. (B) Graphical depiction of vascular lines, injury site and the REBOA balloon placement.

Animal Preparation

After a 4–7-day period of acclimatization, female 40–50 kg Yorkshire swine were fasted for 8–10 hours the day before surgery. Water was made available ad libitum. On the day of the experiment, animals were sedated with a dorsal intramuscular injection of 8mg/kg tiletamine/zolazepam (Telazol) and 0.005mg/kg Glycopyrrolate. Anesthesia was induced with 2–5% isoflurane and 100% oxygen via face mask. After orotracheal intubation, animals were mechanically ventilated and maintained with isoflurane at 1–3% as needed throughout the surgical portion of the experiment. Warming blankets were utilized to minimize hypothermia.

Intravenous (IV) access, for medications and IV fluids, was achieved by antegrade cannulation of the left external jugular vein with a 7 French (Fr) sheath and cephalad ligation (Figure 1B). Proximal arterial access, for lab draws and above-the-balloon blood pressure monitoring (A1 tracing), was gained by retrograde cannulation of the common carotid artery with a 7 Fr sheath and distal ligation.

A 7 Fr introducer for insertion of the REBOA catheter was inserted into the right femoral artery after a cut-down was performed. A midline laparotomy and cystostomy were performed and a 14 Fr Foley catheter (Bard Medical, Covington, Georgia) was secured in the bladder. Concurrently, the abdominal viscera were rotated in a left-to-right manner and the supraceliac aorta exposed (Supplemental Digital Content 1). Next, animals randomized to REBOA arms had either an ER-REBOA or pREBOA-PRO catheter inserted through the right femoral introducer and advanced under direct palpation until the balloon was confirmed above the diaphragm (approximately 55cm; Figure 1B). The area surrounding the aortic exposure was packed with five pre-weighed laparotomy pads and both above-the-balloon (A1) and below-the-balloon (A2) arterial lines were connected to the monitor and arterial wave tracings confirmed.

Injury

With the abdominal viscera rotated, a 4 mm punch biopsy (McKesson Medical Surgical Inc., Richmond, Virginia) was used to create a direct aortic injury immediately above the celiac trunk (Figure 1B). Uncontrolled hemorrhage was allowed for 30 seconds into a pre-weighed aspiration canister.

Interventions

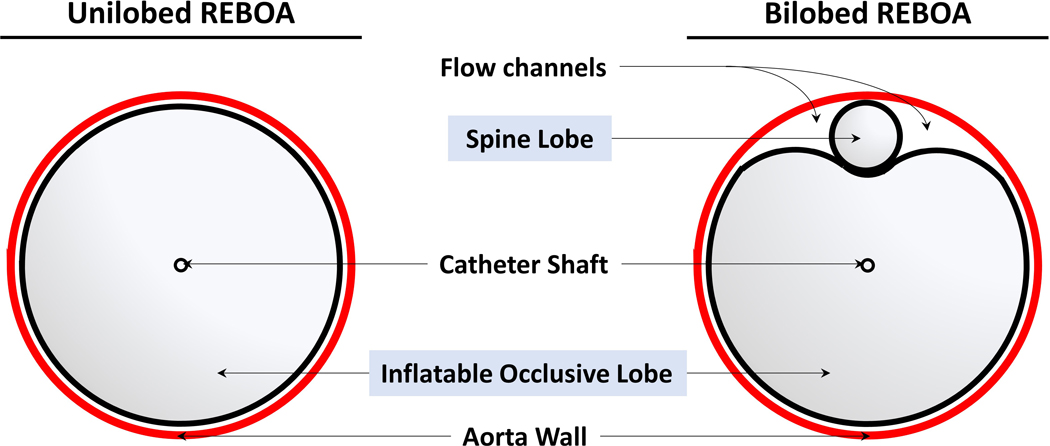

The protocol used in this study was adapted from a protocol published by Johnson et al,7 utilizing established unilobed ER-REBOA and a novel bilobed pREBOA-PRO catheters (Figure 2), both of which were provided by Prytime Medical (Boerne, TX). After 30 seconds of uncontrolled hemorrhage, a resuscitative bolus of 1L lactated Ringer’s solution was administered. In the intervention arms, the aortic occlusion balloons were inflated to full-aortic-occlusion defined by elimination of the A2 waveform on the monitor and held at full occlusion for 10 minutes to attain downstream clot stabilization.17 After 10 minutes the aortic occlusion balloons were gradually deflated in step-wise fashion to create a state of partial REBOA, defined as approximately 50% reduction in aortic flow which corresponds to about a 50% MAP gradient.7,11,19 The baseline mean arterial pressure (MAP) range for our animals was 60–86 mmHg, thus we set the below-the-balloon MAP goal to 40±5 mmHg with a visible A2 arterial waveform. When transitioning from full-aortic-occlusion to the target MAP, balloon volumes were initially decreased by 0.5mL steps at 30 second intervals until the appearance of the A2 waveform then by 0.1mL steps to goal below-the-balloon MAP. The below-the-balloon pressure was subsequently maintained at the goal for an additional 240 minutes by making balloon adjustments as necessary while data and samples were collected.

Figure 2: Schematic representation REBOA catheters used in this study.

Left, currently on the market unilobed ER-REBOA. Right, a novel bilobed pREBOA-PRO with controlled below-the-balloon flow channels.

Observation and Data Collection

During the MAP goal maintenance stage, the animals were continued under general anesthesia with 1–3% inhaled isoflurane on a ventilation strategy targeting an EtCO2 of 40±5 mmHg with maintenance IV fluids at a rate of 5mL/kg/hr. As previously stated, a below-the-balloon MAP of 40±5 mmHg with a pulsatile arterial line tracing was targeted for partial REBOA. If the below-the-balloon MAP deviated outside of this range, the balloon volume was adjusted accordingly and each adjustment recorded. Occlusion balloons were never put back to full occlusion, even in the face of ongoing hemorrhage. Physiologic data including core body temperature, heart rate, above-and below-the-balloon MAPs, respiratory rate, tidal volume, SpO2, ECG tracing, and EtCO2 were recorded hourly using a multi-channel data acquisition system (Biopac Systems Inc., Goleta, CA).

Whole blood was collected at baseline and hourly thereafter. Arterial blood gas, lactate, hemoglobin, hematocrit and chemistry panel were measured using an i-STAT (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL). Thromboelastography (TEG) tests were performed on fresh whole blood in a kaolin activated cup using the TEG-5000 Hemostasis Analyzer (Haemonetics, Braintree, MA). Plasma samples were also collected every hour and were immediately frozen. At the time of euthanasia, the abdomen was re-opened and the pre-weighed laparotomy pads were removed and used in calculation of the total blood loss. Total urine output was recorded at time of euthanasia and necropsy was performed to harvest tissue samples from neck muscle, thigh adductor muscle, kidney, liver, and small bowel.

Cytokines

Multiplex Luminex assay (Millipore, Burlington, MA) was used to quantify cytokine content in plasma samples according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Histology

Tissue specimens were rehydrated in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, paraffin embedded, sliced at 5 micrometers, and stained with H&E. Three fields per slide were visualized and quantified by a pathologist in a blinded fashion. Histological samples were graded for pathological severity as follows: none=0, mild=1, moderate=2 and severe=3. Presence of acute neutrophilic inflammation over background lymphoplasmacytic/eosinophilic inflammation provided an additional score of 0.5.

Statistical Analysis

Referencing the study by Russo et al.,11 expected primary outcomes were estimated for power analysis via a two tailed t-test (90% power, alpha 0.05), determining that 9 animals would be needed per study group. Results were collected and analyzed from exactly 9 animals for each partial REBOA study group.

Physiologic data are presented as median values with interquartile ranges unless otherwise specified and differences at each time point were evaluated with Wilcox Rank-Sum tests. Laboratory and TEG data were reported as median values with interquartile ranges and evaluated with a mixed-effects regression model with the empirical robust “sandwich” standard error estimator to compensate for missing data time points. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to evaluate differences in median survival between groups. Incidences of pathologies per group were compared using chi-square test. Where applicable, Hochberg statistical correction for multiple comparisons was performed. Two fully-occlusive REBOA controls were run for the entire experimental protocol during model development for reference, but were not included in the data analysis as a study arm.

RESULTS

There were no significant differences in baseline physiologic parameters between the three study groups (Supplemental Digital Content 2), nor fully-occlusive REBOA controls that were used in the model development only (data not shown). All groups had comparable arterial blood gas, hemoglobin/hematocrit and basic metabolic panel values. Post-injury, controls without REBOA intervention quickly developed tachycardia, tachypnea and acute respiratory acidosis. Partial REBOA intervention with either ER-REBOA or pREBOA-PRO lead to comparable levels of stable tachycardia and mild tachypnea, with stable above-and below-the-balloon MAPs and SpO2 (Table 1). There were no significant differences in any of the physiologic parameters between the two catheter groups.

TABLE 1:

Data and Labs Overtime.

| grp. | Baseline | 1-Hour | 2-Hour | 3-Hour | 4-Hour | N | p-values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physiologic parameters | ||||||||

| Temperature (°C) | 1 | 37 (36.4, 37.6) | 36.6 (36, 36.9) | 37.4 (36.2, 37.9) | 37.6 (37, 38.6) | 38.2 (37.2, 38.7) | 18 | 0.30 |

| 2 | 37.4 (36.3, 37.7) | 36.1 (35.3, 36.7) | 36.2 (35.8, 37.2) | 36.8 (36.3, 38.4) | 37.4 (36.1, 38.3) | |||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 1 | 97 (85, 113.5) | 120 (112.5, 139.5) | 137 (119.5, 167.5) | 147 (115.3, 170.3) | 144 (112.3, 162.8) | 18 | 0.84 |

| 2 | 96.5 (86, 101.8) | 125 (102.5, 198) | 139 (105.5, 157.5) | 118.5 (97.8, 144.5) | 124 (102.3, 134.5) | |||

| Respiratory rate | 1 | 24 (17.5, 28) | 25 (17.5, 29) | 22 (17.5, 30.5) | 23 (17.3, 34.5) | 22.5 (17.3, 34) | 18 | 0.09 |

| 2 | 21 (18.5, 24.8) | 20 (18, 23.5) | 22 (20, 22) | 22 (20, 22) | 22 (21.5, 24.3) | |||

| SpO2 | 1 | 98 (96, 99) | 95 (93.5, 98) | 93 (90.5, 98) | 96.5 (89.8, 98) | 96.5 (95, 98.8) | 18 | 0.51 |

| 2 | 97 (96.3, 97.8) | 97 (96.5, 98) | 97 (97, 98) | 97 (94.5, 98.3) | 96.5 (90.8, 98) | |||

| MAP Above | 1 | 64 (61.5, 65.5) | 52 (48, 68) | 65 (40, 81) | 80 (46, 90.8) | 64.5 (38.8, 80.5) | 18 | 0.88 |

| 2 | 71.5 (62.5, 84.8) | 56 (45.5, 83.5) | 58.5 (30.8, 86.8) | 63 (37.8, 94.3) | 49 (32, 91.3) | |||

| MAP Below | 1 | - | 37 (28, 39) | 39 (28, 41.5) | 36 (30, 40.8) | 36 (25.8, 38.8) | 18 | 0.22 |

| 2 | - | 29 (18, 40.5) | 29 (14.3, 42) | 37 (24, 40) | 35 (21.5, 41.3) | |||

| Basic Labs | ||||||||

| pH | 1 | 7.4 (7.4, 7.6) | 7.3 (7.2, 7.4) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.5) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.5) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.5) | 18 | 0.71 |

| 2 | 7.5 (7.4, 7.5) | 7.3 (7.2, 7.4) | 7.4 (7.2, 7.5) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.5) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.5) | |||

| HCO3 | 1 | 32.2 (31.2, 34) | 23.6 (20.4, 27.4) | 29.1 (22.3, 30.6) | 31.4 (26.3, 32.5) | 31.5 (25.7, 32.9) | 18 | 0.18 |

| 2 | 31.7 (31.2, 34.1) | 19.4 (16, 28.9) | 22.1 (10.7, 31.4) | 27.1 (19.9, 32.9) | 28.8 (21.4, 33.5) | |||

| pCO2 | 1 | 45.9 (37.1, 54.9) | 47.4 (42.6, 56.8) | 43.8 (38.8, 57.6) | 47.5 (42.5, 54.8) | 47.7 (40.8, 53.8) | 18 | 0.03 |

| 2 | 43.1 (39.2, 50.2) | 39.4 (34.3, 44.6) | 39.2 (26.9, 45.4) | 42.4 (37.5, 46.7) | 42.2 (37, 47.8) | |||

| pO2 | 1 | 369 (249, 403) | 214 (150, 348.5) | 194 (151, 312.5) | 189.5 (145.3, 251.8) | 188.5 (162, 246) | 18 | 0.90 |

| 2 | 384 (244, 435) | 248 (187.5, 292) | 203.5 (113, 267.8) | 209 (103.8, 277.3) | 206 (117.8, 268.8) | |||

| Lactate | 1 | 1.7 (1.5, 1.9) | 7.7 (6.3, 11.3) | 3.9 (3.3, 10.7) | 2.5 (2.2, 7.4) | 2.2 (2, 7) | 18 | 0.19 |

| 2 | 2.3 (1.4, 2.7) | 11.8 (4.2, 14.6) | 9.8 (2.3, 17.3) | 5.1 (2.1, 11.9) | 4 (1.8, 10.7) | |||

| Anion gap | 1 | 12 (10.5, 14.5) | 19 (16, 21.5) | 16 (12, 20.5) | 13 (12, 18) | 14 (12, 17.3) | 18 | 0.17 |

| 2 | 12 (11, 14) | 21 (14.5, 24) | 19.5 (13, 26.5) | 17 (13, 22.8) | 14 (11.8, 21) | |||

| Hemoglobin | 1 | 8.2 (7.9, 9) | 6.8 (5.2, 7.5) | 6.8 (5.5, 7.7) | 6.7 (5.9, 7.6) | 7 (5.9, 8) | 18 | 0.25 |

| 2 | 8.2 (6.8, 8.7) | 5.8 (5, 6.8) | 5.6 (5, 7.4) | 6.6 (5.6, 7.9) | 6.7 (5.6, 7.8) | |||

| Hematocrit | 1 | 24 (23, 26.5) | 20 (15.5, 22) | 20 (16, 22.5) | 19.5 (17.3, 22.5) | 20.5 (17.3, 23.5) | 18 | 0.26 |

| 2 | 24 (20, 25.5) | 17 (15, 20) | 16.5 (15, 21.8) | 19.5 (16.5, 23.3) | 19.5 (16.5, 22.8) | |||

| Ionized Calcium | 1 | 1.4 (1.4, 1.4) | 1.3 (1.3, 1.3) | 1.4 (1.3, 1.4) | 1.4 (1.4, 1.4) | 1.4 (1.3, 1.4) | 18 | 0.65 |

| 2 | 1.4 (1.3, 1.4) | 1.4 (1.3, 1.4) | 1.4 (1.3, 1.4) | 1.4 (1.4, 1.4) | 1.4 (1.3, 1.4) | |||

| BUN | 1 | 5 (3.5, 7) | 5 (4, 9) | 6 (5, 10.5) | 8 (4.5, 12.3) | 8.5 (5.5, 14.3) | 18 | 0.66 |

| 2 | 5 (4, 8) | 6 (4, 8.5) | 5.5 (4.3, 7.8) | 6 (5.8, 8.5) | 7.5 (6.8, 8.8) | |||

| Creatinine | 1 | 1.3 (1.2, 1.4) | 1.7 (1.5, 1.8) | 2 (1.8, 2) | 2.3 (2.2, 2.4) | 2.7 (2.5, 2.8) | 18 | 0.30 |

| 2 | 1.2 (1.2, 1.5) | 1.7 (1.5, 1.9) | 2 (1.7, 2) | 2.4 (2.2, 2.6) | 2.7 (2.5, 2.9) | |||

| Potassium | 1 | 4 (3.8, 4.3) | 4.2 (4, 4.3) | 4.8 (4.4, 5.2) | 5.3 (4.9, 6) | 5.7 (5.4, 7.3) | 18 | 0.15 |

| 2 | 3.9 (3.8, 4) | 4.2 (3.8, 5) | 4.8 (4.4, 5.6) | 5.5 (5.2, 6.8) | 6.6 (6, 8.3) | |||

| Thromboelastography Values | ||||||||

| R (min) | 1 | 7.9 (5.9, 8.8) | 3.7 (3.6, 4.3) | 3.8 (3.4, 4.9) | 4 (3, 5) | 4.3 (3, 4.6) | 18 | 0.27 |

| 2 | 7.4 (6.5, 9.1) | 4.4 (3.4, 5.1) | 3.7 (2.8, 4.7) | 3.4 (2, 10.7) | 3.5 (−10, 6.6) | |||

| K (min) | 1 | 1.4 (1.3, 1.8) | 0.9 (0.9, 1.1) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) | 1 (0.8, 1) | 1 (0.8, 1.1) | 18 | 0.03 |

| 2 | 1.6 (1.3, 1.8) | 1 (1, 1.3) | 1 (0.8, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.9, 1.2) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | |||

| Angle (degrees) | 1 | 75.6 (73.6, 77.2) | 79.5 (78.4, 79.7) | 79.7 (78.4, 80.3) | 79.7 (78.9, 80.8) | 79.9 (78.8, 81.5) | 18 | 0.05 |

| 2 | 73.9 (71.8, 76) | 78.5 (75.1, 79.3) | 78.9 (74.2, 80.3) | 78.4 (66.3, 80.9) | 78.2 (74.5, 80.7) | |||

| MA (mm) | 1 | 80.1 (78.7, 81.2) | 76.5 (72.8, 79.1) | 77.2 (74.9, 78.9) | 77.9 (74.7, 78.6) | 77.4 (72.2, 80.9) | 18 | 0.13 |

| 2 | 79 (76.9, 81.5) | 74.7 (66, 77.2) | 75.4 (57.4, 78.4) | 77.4 (55.5, 81.8) | 75.9 (72.7, 78.1) | |||

| LY30 (%) | 1 | 1.7 (1.2, 2.9) | 1.8 (1.4, 3.6) | 1.6 (1.6, 2.9) | 2.2 (1.3, 2.4) | 2.9 (1.4, 3.5) | 18 | 0.69 |

| 2 | 1.4 (0.7, 2.6) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.5) | 2.2 (0.9, 3.6) | 1.1 (0.7, 2) | 2.2 (1.2, 4.7) | |||

Key: grp. = partial REBOA groups, 1 = partial ER-REBOA, 2 = partial pREBOA-PRO.

Values are reported as median values with interquartile ranges and evaluated with a mixed-effects regression model with the empirical robust “sandwich” standard error estimator to compensate for missing data time points.

ER-REBOA use lead to increased hypercapnia (pCO2) as compared to pREBOA-PRO (Table 1). Both partial REBOA groups experienced a significant increase in bicarbonate (HCO3) and anion gap, but neither developed significant acidosis. Otherwise, there were no statistically significant differences in lactate, hemoglobin, hematocrit, ionized calcium, BUN, creatinine, or potassium across time for either catheter group from baseline nor between the two catheter groups. After an initial drop immediately post-injury, with 30 seconds of uncontrolled hemorrhage and a liter fluid bolus, hemoglobin and hematocrit stayed stable for the remainder of the study in both of the partial REBOA groups. Both groups exhibited comparable levels of lactate, creatinine and potassium elevation. Of note, fully-occlusive REBOA controls rapidly developed metabolic acidosis with an anion gap over twenty and lactate levels trending up in double digits. One of the no intervention controls, that survived past the median of 18 minutes, maintained normal pH, pCO2 and lactate levels with only a mild drop in hematocrit and continuous mild rise in creatinine.

On TEG profiles, both partial REBOA groups exhibited similarly shortened R times and elevated max amplitudes (MA) post injury (Table 1). Both groups had a propensity for shorter K and steeper angle post injury, with ER-REBOA overall having significantly more robust fibrinogen clot formation parameters as compared to pREBOA-PRO. Fibrinolytic measure (LY30) was within normal limits for both partial REBOA groups. Fully-occlusive controls had normal R, K and LY30 with mild elevation of the angle that normalized and then went up again at the later timepoints and an MA that started high and normalized by the 4th hour of the experiment. No intervention controls had normal R, K and LY30, and elevated angle and MA to a comparable degree as partial REBOA groups.

Without intervention, our aortic injury study model led to American College of Surgeons Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) Class 4 hemorrhage with a median loss of 59% of total blood volume (Table 2). Two fully-occlusive REBOA controls had decreased estimated blood loss (25% and 31% for ER-REBOA and pREBOA-PRO, respectively). When utilized as partial REBOA, ER-REBOA and pREBOA-PRO use resulted in similar blood loss (41% and 50%, respectively); which was not statistically different from no intervention controls. Partial REBOA groups received comparable levels of total fluid resuscitation and produced comparable total urine output. The median difference of the below-the-balloon MAP from the target of 40 mmHg was not significantly different between the partial REBOA groups over the course of the experiment. (Table 2). However, the median number of adjustments required to maintain partial REBOA at the target below-the-balloon MAP was significantly lower in the pREBOA-PRO group compared to the ER-REBOA group (3 vs 10, p = 0.01) (Table 2).

TABLE 2:

Survival time, total outputs and inputs and REBOA balloon volume adjustments post injury.

| Total Values | Control | Partial ER-REBOA | Partial pREBOA-PRO | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival time (min) | 18 (0, 240) | 240 (231, 244.5) | 242 (120, 245.5) | 0.98 |

| Total blood loss (mL) | 1990 (1490,2800) | 1355 (1258,1985) | 1680 (1040,2460) | 0.96 |

| Total blood loss (%) | 59 (44,83) | 41 (38,59) | 50 (32,73) | 0.91 |

| Total fluids (mL) | 1074 (0,2000) | 1960 (1938,2013) | 1966 (1487,1988) | 0.38 |

| Total urine output (mL) | 50 (0,55) | 30 (25,68) | 30 (15,34) | 0.25 |

| Maintenance of below-the-balloon MAP | Partial ER-REBOA | Partial pREBOA-PRO | p-values | |

| Number of required adjustments | 10 (7.5, 12.5) | 3 (1, 5) | 0.01 | |

| Difference in below-the-balloon MAP from Goal: | ||||

| 1-Hour | −3 (−12, −1) | −11 (−22, 0.5) | 0.45 | |

| 2-Hour | −1 (−12, 1.5) | −11 (−25.8, 2) | 0.29 | |

| 3-Hour | −4 (−10, 0.8) | −3 (−16, 0) | 0.80 | |

| 4-Hour | −4 (−14.3, −1.3) | −5 (−18.5, 1.3) | 0.85 | |

Values are reported as Medians with Interquartile Ranges. Differences evaluated with Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test.

Median survival times for the no intervention controls, ER-REBOA and pREBOA-PRO groups were 18, 242 and 240 minutes, respectively (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in survival trends between the two partial REBOA experimental arms with a log-rank p-value of 0.893 (Supplemental Digital Content 3).

Tissue histology results and representative images per group are reported in Table 3 and Supplemental Digital Content 4, respectively. Use of pREBOA-PRO lead to significantly lower levels of hepatic periportal inflammation (p=0.035) and incidence of neutrophilic periportal (p=0.018) and subcapsular inflammation (p=0.018). Similarly, incidence and severity of neutrophilic capsulitis with fibrosis were significantly lower in pREBOA-PRO (p=0.016 and 0.050, respectively).

TABLE 3:

Tissue Histology Analysis.

| Pathology Severity

Scores |

Percent Pathology

Incidence |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | (1) Partial ER-REBOA | (2) Partial pREBOA-PRO | p-values | Control | (1) | (2) | p-values | ||

| Liver | Atrophy Centrilobular Cords | 0 (0, 1.5) | 1.5 (0, 1.5) | 1.5 (0.8, 1.5) | 0.772 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 88.9 | 0.256 |

| Necrosis Centrilobular | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 1.3) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.471 | 0.0 | 22.2 | 0.0 | 0.134 | |

| Fibrosis | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | >0.999 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.304 | |

| Degeneration Centrilobular | 0 (0, 0) | 1.5 (0, 2.3) | 0 (0, 1.3) | 0.087 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 0.157 | |

| Increased Circulating Neutrophils | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.206 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 0.058 | |

| Periportal Inflammation | 1 (0, 1) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.5) | 1 (0.5, 1.3) | 0.035 | 66.7 | 100.0 | 77.8 | 0.134 | |

| Neutrophilic inflammation | 0.0 | 77.8 | 22.2 | 0.018 | |||||

| Background Inflammation | 66.7 | 22.2 | 55.6 | 0.147 | |||||

| Subcapsular Inflammation | 0 (0, 0) | 1 (0.5, 1) | 0 (0, 0.5) | 0.057 | 0.0 | 77.8 | 22.2 | 0.018 | |

| Neutrophilic inflammation | 0.0 | 77.8 | 22.2 | 0.018 | |||||

| Background Inflammation | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | >0.999 | |||||

| Capsulitis, neutrophilic, with fibrin | 0 (0, 0) | 1 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.050 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 11.1 | 0.016 | |

| Hemorrhage | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | >0.999 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.304 | |

| Congestion Centrilobular | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0.8) | 0 (0, 1.8) | 0.327 | 0.0 | 22.2 | 44.4 | 0.317 | |

| Kidney | Tubular Degeneration | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | >0.999 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | >0.999 |

| Tubular necrosis | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0.5) | 0 (0, 1) | >0.999 | 0.0 | 22.2 | 33.3 | 0.599 | |

| Interstitial nephritis | 1 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) | 1 (0, 1) | 0.637 | 66.7 | 44.4 | 66.7 | 0.343 | |

| Congestion | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | >0.999 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 0.304 | |

| Small intestine | Overall Inflammation Severity | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 1) | 1 (1, 2) | 0.577 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1.000 |

| Background Inflammation | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1.000 | |||||

| Edema of Lamina Propria | 2 (2, 2) | 2 (2, 2) | 2 (2, 2) | >0.999 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1.000 | |

| Muscularis Mucosa inflammation | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | >0.999 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.304 | |

| Skeletal muscle, Above | Degeneration | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 0.5) | 0.577 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 22.2 | 0.510 |

| Necrosis | 0 (0, 1) | 1 (0.5, 2) | 1 (0, 1.5) | 0.388 | 33.3 | 77.8 | 55.6 | 0.317 | |

| Regeneration | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0.5) | 0 (0, 0) | >0.999 | 0.0 | 22.2 | 11.1 | 0.527 | |

| Skeletal muscle, Below | Degeneration | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0.5) | >0.999 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 22.2 | 0.527 |

| Necrosis | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) | >0.999 | 33.3 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 1.000 | |

| Regeneration | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | >0.999 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | >0.999 | |

Pathology severity scores are reported as medians with interquartile values. Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test was used to compare severity scores and chi2-test was used to compare incidences of pathology in pREBOA-PRO and ER-REBOA groups.

Key: 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe; Background inflammation = lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic.

There were no significant differences in kidney, small intestine or skeletal muscle above-or below-the-balloon between ER-REBOA and pREBOA-PRO groups. There was an equal level of mild multifocal lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis across REBOA groups and no intervention controls. Only REBOA groups exhibited comparable incidences of tubular necrosis (pREBOA-PRO 33% vs. ER-REBOA 22%; p=0.599). All groups experienced lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic small intestine inflammation and edema of the lamina propria. One of the ER-REBOA animals developed inflammation down to the muscularis mucosa. No neutrophilic small intestine inflammation was noted in any of the groups. Both partial pREBOA-PRO and ER-REBOA exhibited comparable levels of mild-moderate skeletal muscle necrosis below the device insertion site as well as occasional mild necrosis above the device insertion site.

Both partial REBOA groups had a progressive inflammatory response post injury with increasing levels of IL-6, TNFα, IL-1Rα, IL-12, IL-8, IL-10, IL-18, IFNγ, IL-2 and GM-CSF (Supplemental Digital Content 5 and Table 4). Use of partial ER-REBOA resulted in increased levels of IL-10 as compared to the partial pREBOA-PRO group (p=0.006), with the greatest differences in the 2nd and 3rd hour of the experiment. The statistically significant difference in IL-10 trends stayed valid post Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons. IL-10 rise in both groups significantly correlated with increases in TNFα and IFNγ (Supplemental Digital Content 6).

Table 4:

Cytokine trend analysis post injury using AUCs.

| Cytokine Trends | Partial ER-REBOA | Partial pREBOA-PRO | p-values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early immune response | IL-1β | 0.43 (0.29, 1.34) | 0.16 (0.07, 0.43) | 0.246 |

| IL-6 | 1.54 (0.85, 2.51) | 1.15 (0.21, 2.05) | 0.232 | |

| TNFα | 0.29 (0.16, 0.47) | 0.15 (0.08, 0.34) | 0.128 | |

| Potentiation | IL-1α | 0.12 (0.07, 0.21) | 0.06 (0.03, 0.13) | 0.130 |

| IL-1rα | 114.5 (48.36, 174.7) | 9.72 (0.38, 101.79) | 0.077 | |

| IL-12 | 4.4 (2.74, 5.12) | 3.46 (1.25, 3.66) | 0.160 | |

| Neutrophil and NK regulation | IL-8 | 0.26 (0.16, 0.32) | 0.21 (0.08, 0.25) | 0.433 |

| IL-10 | 1.06 (0.73, 1.71) | 0.51 (0.2, 0.77) | 0.006 | |

| IL-18 | 4.18 (2.36, 8.29) | 2.59 (0.51, 4.18) | 0.135 | |

| IFNγ | 51.7 (35.2, 102.2) | 31.5 (18.4, 67.7) | 0.232 | |

| Late immune response | IL-2 | 0.51 (0.31, 0.92) | 0.23 (0.16, 0.63) | 0.065 |

| IL-4 | 0.75 (0.32, 1.3) | 0.29 (0.16, 0.96) | 0.193 | |

| GM-CSF | 0.11 (0.09, 0.17) | 0.13 (0.07, 0.19) | 0.960 | |

| Cytokine Trend Ratios | ||||

| IL-6 : IL-10 | 3.75 (2.24, 10.6) | 8.07 (3.86, 15.25) | 0.181 | |

| TNFα : IL-10 | 0.89 (0.7, 1.56) | 0.74 (0.45, 1.29) | 0.446 | |

| IFNγ : IL-10 | 217.3 (206.5, 527.5) | 299.4 (126.3, 500.6) | 0.761 | |

Abbreviations: AUC -area under the curve, NK -natural killer cells.

Values are expressed as median AUC and interquartile ranges. Cytokine expression trends between partial REBOA types are compared using Wilcox rank-sum. Cytokines groupings in this table are do not address full nuance of immune pathways.

We then calculated ratios of IL-6/IL-10 and TNFα/IL-10 ratios, as elevations in these ratios have been shown to be predictive of worse outcomes in thoraco-abdominal injuries23 and other post-ischemic inflammatory states. Both partial REBOA interventions led to comparable elevation trends of IL-6/IL-10 and TNFα/IL-10 ratios (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

While the REBOA concept was developed in the 1950s,24 its use in humans in the United States was not approved by Food & Drug Administration until late 2015. In the optimal setting, when performed by skilled hands, REBOA has a great potential to bridge a trauma patient to definitive care, as long as its use to occlude the aorta does not exceed the recommended 30 minutes.12,25 Partial REBOA trials show potential to prolong balloon time with normalization of the above-the-balloon pressure while mitigating below-the-balloon ischemia by allowing partial distal perfusion in animal studies9,11,16 as well as in patients.26 It was shown superior to intermittent REBOA, which was also proposed as an alternative to fully-occlusive REBOA,14,27 by normalizing pressures and reducing small intestine edema.15 However, partial REBOA was found less useful an hour into hemorrhagic shock in trauma animal models with concomitant traumatic brain injury,28 suggesting the importance of intervention timing and overall understanding of traumatic physiology.

The trauma community recognizes the unmet need of pre-hospital interventions for hemorrhage control and the potential of the new REBOA techniques.20,22,29 While the majority of clinical reports on REBOA use are from the in-hospital setting,26,30–32 there are recent reports of successful prehospital REBOA use in Zone 333,34 and Zone 1.35 The US Military has proposed the use of prehospital REBOA and whole blood, Acute Resuscitative Care, as a combined method to mitigate the extremely high mortality of hemorrhagic shock and highlighted this issue in their research objectives.27,36 This has fueled our interest in the combined utility of pre-hospital partial REBOA specifically for austere environments on the battlefield and in rural areas where definitive hemorrhage control may be a number of hours away.

The goal of our study was to test the utility of a specially designed bilobed partial REBOA catheter in early stages of a Class 3–4 hemorrhage animal model. Similar to work by other groups,7,16 our study showed that following a brief period of full-aortic-occlusion in Zone 1, transition to partial aortic occlusion allowed restoration of proximal physiologic parameters, including heart rate and mean arterial pressure, which could then be sustained far beyond ‘the golden hour’. Similar to the original report by Russo et al.,11 both partial REBOA groups provided protective effects against development of small intestinal necrosis and lactic acidosis that was seen with complete occlusion controls. Our study demonstrated that use of the bilobed pREBOA-PRO lead to similar mortality, blood loss, and variation of below-the-balloon MAP from target, while requiring significantly fewer balloon volume manipulations as compared to unilobed partial ER-REBOA. We also found that pREBOA-PRO use lead to a lower overall inflammatory state, which may be of benefit clinically.

Endothelial injury during extensive aortic manipulation in endovascular aortic aneurysm repair, has been shown to lead to a number of downstream inflammatory responses.37 These include development of fever, cytokine production, increased neutrophil chemotaxis to tissues and systemic inflammatory response.38 In our study, both of the partial REBOA groups showed an acute inflammatory phenotype. Partial ER-REBOA specifically had significantly higher fibrinogen-dependent clot formation on TEGs, which could be indicative of the release of this acute phase reactant. Animals with partial ER-REBOA furthermore had significantly increased hypercapnia, which may be related to the systemic inflammatory response and increased dead space.

IL-10 levels were increased in the ER-REBOA group. In aortic aneurysm repairs, IL-10 cytokine increase is reported to follow a biphasic curve,39 rising with ischemia and falling during reperfusion with persistent high IL-10 levels significantly associated with longer intensive care unit and hospital stays.40 In the presence of stress, IL-10 is produced by activated macrophages as well as liver cells, including hepatocytes, sinusoidal endothelial cells, Kupffer cells and liver-associated lymphocytes. While classically IL-10 is thought of as primarily an anti-inflammatory cytokine, studies over the years have shown that in certain pathologic stresses, IL-10 can switch to the STAT1-pathway producing a pro-inflammatory response.41 This was especially evident in human studies when injection of IL-10 as an intended therapeutic lead to an exacerbated inflammatory response.42 During this aberrant switch, IL-10 promotes IFNγ expression and has been shown to fail to suppress neutrophil activator, TNFα. Expression of both IFNγ and TNFα strongly correlated with IL-10 expression in both partial REBOA groups.

Hepatic sinusoid microcirculation can suffer disproportionally to a total decrease and fluctuation in circulating blood volume.43,44 This subsequently results in a cascade of events including an adrenergic response that leads to a decrease in sinusoidal diameter further compromising liver perfusion and leading to leukocytic congestion, leukocyte activation and adhesion to the endothelium.43,45,46 The liver has a dual blood supply from the proper hepatic artery branch of the celiac trunk and the portal vein returning blood from the gastrointestinal system. It has been proposed that use of an occlusive unilobed REBOA may lead to major reduction in both arterial and venous inflow.47 This has further been demonstrated in a non-trauma swine study using phase-contrast MRI, showing a significant decrease in blood flow in the inferior vena cava, hepatic vein and portal vein in the presence of an occlusive REBOA.48 In our study, partial aortic occlusion for 240 minutes using ER-REBOA led to significantly higher levels of hepatic neutrophilic inflammation vs. pREBOA-PRO. While there are no published hepatopathy observations in the partial REBOA trials, it is possible that a combined effect of high blood volume loss and endothelial damage produced due to aorta manipulation during multiple balloon volume adjustments may result in vascular tone alterations and immunologic responses that lead to the hepatic pathology seen in our study. Further studies would need to be completed to investigate this effect further.

Part of the variability between partial REBOA studies, is the personalized definitions of the partial REBOA itself. For our study we followed the report by Russo et al., where the partial REBOA setting was defined as unilobed balloon inflation until half of the above-the-balloon MAP is achieved below-the-balloon.11 Partial REBOA with about 50% below-the-balloon MAP showed clear benefit in preventing distal ischemia and tissue pathology after 90 minutes;7,11 with significantly less ongoing hemorrhage than that seen in the presence of a more liberal 60–70% below-the-balloon MAP.16 In a recent study using bilobed pREBOA-PRO, a strong correlation between the below-the-balloon flow rate and both proximal and distal MAP was shown and specifically identified a middle of the range flow rate that correlated with about 40–49% of the MAP gradient and was associated with the least mortality as compared to both more liberal and more stringent flow settings.19 Further studies are needed to fully determine the optimal balloon volume and pressure gradient to find balance between hemorrhage control and below-the-balloon perfusion.

The rationale of partial REBOA function depends on an assumption that a clot will be able to form around the source of hemorrhage, thus the blood flow allowed below-the-balloon will mitigate distal ischemia and help normalize proximal pressure preventing rebleeding.49,50 In our study, after a transient 10 minutes of full occlusion to permit clot stabilization,7,17 we gradually deflated our balloons to the goal MAP. Subsequently, significant balloon manipulation was required to maintain the goal MAP, which combined with vasospasm49 could potentially lead to disruption of the formed clot and thus ongoing hemorrhage and even embolization of thrombi. The correlation between below-the-balloon flow rates and rebleeding has been reported and interestingly the flow rate that correlated with the most rebleeding is within the range of the flow rate that was associated with the most survival;19 but there is no data about REBOA balloon adjustments and related flow perturbations. This limits the conclusions concerning the physiologic benefits of less manipulations of pREBOA-PRO. However, in austere or battlefield conditions, there is a clear logistical benefit of a catheter that requires less manipulations.

The level of hemorrhage in our study provided both a unique setting as well as a limitation, as severe hemorrhage can potentially lead to a number of the physiologic vascular responses to shunt remaining blood to the vital organs and mask some of the REBOA effects. The majority of the studies on REBOA limit blood loss to 10–30 percent of total blood volume,11,15,16,19; with one study with 35 percent blood loss looking specifically at inflammatory sequalae of REBOA use.13 In our study, the median blood loss in the partial REBOA groups was above 40 percent, which can make a drastic difference for organ perfusion and injury, especially the liver as discussed.

Our study is limited by the overall duration of the study, as it is difficult to know what the findings developed by the 3rd and 4th hour in either of the partial REBOA groups could translate to for subjects in the long term. This includes requirements for further resuscitation during the recovery period after discontinuation of partial REBOA and survival of animals past the defined 240-minute post-intervention period.

While this was not part of the primary goal, the comparison between partial REBOA groups and no intervention group was limited by the lower power of the control group and high lethality of the injury. Similarly, fully-occlusive REBOA controls were only used as part of the model development and thus could not be fully compared to either of partial REBOA groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Specially designed bilobed pREBOA-PRO catheter is non-inferior to unilobed ER-REBOA used for partial aortic occlusion to control hemorrhage while allowing perfusion below-the-balloon. This new technology provides superior below-the-balloon goal MAP maintenance as it requires less adjustments and may potentially lead to decreased inflammatory sequalae.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1: Supraceliac aortic exposure.

Aorta (red arrow), cranial (blue asterisk).

Supplemental Digital Content 3: Survival trends.

Kaplan-Meier analysis displaying time to death from injury for no intervention control, partial ER-REBOA and partial pREBOA-PRO. Two full-occlusion ER-REBOA and pREBOA-PRO controls were included from the study model development.

Supplemental Digital Content 5: Cytokine trends per partial REBOA type.

Asterisk denotes statistically significant difference between trends.

Supplemental Digital Content 6: Cytokine trend correlations. Raw values were plotted and correlated using Spearman test. A Spearman coefficient (Rs) with a value larger than 0.7 indicates a strong correlation.

Supplemental Digital Content 4: Photomicrographs of representative histologic sections of tissues from animals’ post supraceliac aortic injury that have undergone no intervention (Control), partial ER-REBOA or partial pREBOA-PRO. Tissues stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin stain and visualized at (A) 20X or (B) 10X magnification. Liver sections with diffuse mild atrophy of centrilobular hepatic cords in Control, centrilobular degeneration and necrosis with increased circulating neutrophils in ER-REBOA and mild neutrophilic inflammation over background lymphoplasmacytic/eosinophilic (l/e) inflammation in pREBOA-PRO. Kidneys with similar level of background l/e interstitial nephritis in all three groups and mild levels of acute tubular necrosis in ER-REBOA. Essentially normal neck (Above) and thigh adductor (Below) skeletal muscles in Control. Both partial pREBOA-PRO and ER-REBOA with comparable levels of occasional mild necrosis Above and mild-moderate skeletal muscle necrosis Below the device insertion site. Small intestine sections with similar background diffuse l/e inflammation and lamina propria edema in all three groups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the veterinary services from the Division of Comparative Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, for technical support with animal studies.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Zilberman-Rudenko is a Ruth L. Kirschstein Fellow (F31HL13623001).

Conflict of interest: Dr. Behrens received consultancy stipend from Grifols. Dr. Holcomb is a co-founder and on the Board of Directors of Decisio Health, on the Board of Directors of QinFlow and Zibrio, a Co-inventor of the Junctional Emergency Tourniquet Tool, an adviser to Arsenal Medical, Cellphire, Spectrum, and PotentiaMetrics. Dr. Schreiber received consultancy payments from Haemonetics, Arsenal Medical and Velico Medical to Oregon Health & Science University. Oregon Health & Science University received an unrestricted grant from Prytime Medical, the manufacturer of the ER-REBOA and pREBOA-PRO, for this research. Potential conflicts of interest have been reviewed and managed by the Oregon Health and Science University Conflict of Interest in Research Committee.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Drake SA, Holcomb JB, Yang Y, Thetford C, Myers L, Brock M, Wolf DA, Cron S, Persse D, McCarthy J, et al. Establishing a Regional Trauma Preventable/Potentially Preventable Death Rate. Ann Surg. 2020;271(2):375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvin JA, Maxim T, Inaba K, Martinez-Aguilar MA, King DR, Choudhry AJ, Zielinski MD, Akinyeye S, Todd SR, Griffin RL, et al. Mortality after emergent trauma laparotomy: A multicenter, retrospective study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(3):464–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrison JJ, Stannard A, Rasmussen TE, Jansen JO, Tai NRM, Midwinter MJ. Injury pattern and mortality of noncompressible torso hemorrhage in UK combat casualties. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(2 Suppl 2):S263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, Cantrell J, Tops T, Uribe P, Mallett O, Zubko T, Oetjen-Gerdes L, Rasmussen TE, et al. Death on the battlefield (2001–2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6 Suppl 5):S431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sauaia A, Moore FA, Moore EE, Moser KS, Brennan R, Read RA, Pons PT. Epidemiology of trauma deaths: a reassessment. J Trauma. 1995;38(2):185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudery M, Clark J, Wilson MH, Bew D, Yang G-Z, Darzi A. Traumatic intra-abdominal hemorrhage control: has current technology tipped the balance toward a role for prehospital intervention? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(1):153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson MA, Neff LP, Williams TK, DuBose JJ , EVAC Study Group. Partial resuscitative balloon occlusion of the aorta (P-REBOA): Clinical technique and rationale. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(5 Suppl 2 Proceedings of the 2015 Military Health System Research Symposium):S133–S137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore LJ, Martin CD, Harvin JA, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for control of noncompressible truncal hemorrhage in the abdomen and pelvis. Am J Surg. 2016;212(6):1222–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson MA, Williams TK, Ferencz S-AE, Davidson AJ, Russo RM, O’Brien WT, Galante JM, Grayson JK, Neff LP. The effect of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta, partial aortic occlusion and aggressive blood transfusion on traumatic brain injury in a swine multiple injuries model. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(1):61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson AJ, Russo RM, DuBose JJ, Roberts J, Jurkovich GJ, Galante JM. Potential benefit of early operative utilization of low profile, partial resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (P-REBOA) in major traumatic hemorrhage. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2016;1(1):e000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russo RM, Neff LP, Lamb CM, Cannon JW, Galante JM, Clement NF, Grayson JK, Williams TK. Partial Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta in Swine Model of Hemorrhagic Shock. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(2):359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russo RM, Neff LP, Johnson MA, Williams TK. Emerging Endovascular Therapies for Non-Compressible Torso Hemorrhage. Shock Augusta Ga. 2016;46(3 Suppl 1):12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrison JJ, Ross JD, Markov NP, Scott DJ, Spencer JR, Rasmussen TE. The inflammatory sequelae of aortic balloon occlusion in hemorrhagic shock. J Surg Res. 2014;191(2):423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler FK, Holcomb JB, Shackelford S, Barbabella S, Bailey JA, Baker JB, Cap AP, Conklin CC, Cunningham CW, Davis M, et al. Advanced Resuscitative Care in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 18–01:14 October 2018. J Spec Oper Med. 2018;18(4):37–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson MA, Hoareau GL, Beyer CA, Caples CA, Spruce M, Grayson JK, Neff LP, Williams TK. Not ready for prime time: Intermittent versus partial resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for prolonged hemorrhage control in a highly lethal porcine injury model. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88(2):298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russo RM, Williams TK, Grayson JK, Lamb CM, Cannon JW, Clement NF, Galante JM, Neff LP. Extending the golden hour: Partial resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in a highly lethal swine liver injury model. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(3):372–378; discussion 378–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DuBose JJ. How I do it: Partial resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (P-REBOA). J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(1):197–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidson AJ, Russo RM, Ferencz S-AE, Cannon JW, Rasmussen TE, Neff LP, Johnson MA, Williams TK. Incremental balloon deflation following complete resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta results in steep inflection of flow and rapid reperfusion in a large animal model of hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(1):139–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forte DM, Do WS, Weiss JB, Sheldon RR, Kuckelman JP, Eckert MJ, Martin MJ. Titrate to equilibrate and not exsanguinate! Characterization and validation of a novel partial resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta catheter in normal and hemorrhagic shock conditions. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87(5):1015–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang R, Fox EE, Greene TJ, Eastridge BJ, Gilani R, Chung KK, DeSantis SM, DuBose JJ, Tomasek JS, Fortuna GR, et al. Multicenter retrospective study of noncompressible torso hemorrhage: Anatomic locations of bleeding and comparison of endovascular versus open approach. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(1):11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gifford SM, Arthurs ZM. Damage Control Vascular Surgery in the Austere Environment. Curr Trauma Rep. 2016;2(1):42–47. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holcomb JB. Transport Time and Preoperating Room Hemostatic Interventions Are Important: Improving Outcomes After Severe Truncal Injury. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(3):447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taniguchi T, Koido Y, Aiboshi J, Yamashita T, Suzaki S, Kurokawa A. The ratio of interleukin-6 to interleukin-10 correlates with severity in patients with chest and abdominal trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(6):548–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes CW. Use of an intra-aortic balloon catheter tamponade for controlling intra-abdominal hemorrhage in man. Surgery. 1954;36(1):65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenner M, Bulger EM, Perina DG, Henry S, Kang CS, Rotondo MF, Chang MC, Weireter LJ, Coburn M, Winchell RJ, et al. Joint statement from the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS COT) and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) regarding the clinical use of Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA). Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018;3(1):e000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumura Y, Matsumoto J, Kondo H, Idoguchi K, Ishida T, Kon Y, Tomita K, Ishida K, Hirose T, Umakoshi K, et al. Fewer REBOA complications with smaller devices and partial occlusion: evidence from a multicentre registry in Japan. Emerg Med J EMJ. 2017;34(12):793–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser JJ, Fisher AD, Shackelford SA, Butler F, Rasmussen TE. A contemporary report on US military guidelines for the use of whole blood and resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta: J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87:S22–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams AM, Bhatti UF, Dennahy IS, Graham NJ, Nikolian VC, Chtraklin K, Chang P, Zhou J, Biesterveld BE, Eliason J, et al. Traumatic brain injury may worsen clinical outcomes after prolonged partial resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in severe hemorrhagic shock model. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86(3):415–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thabouillot O, Bertho K, Rozenberg E, Roche N-C, Boddaert G, Jost D, Tourtier J-P. How many patients could benefit from REBOA in prehospital care? A retrospective study of patients rescued by the doctors of the Paris fire brigade. J R Army Med Corps. 2018;164(4):267–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brenner ML, Moore LJ, DuBose JJ, Tyson GH, McNutt MK, Albarado RP, Holcomb JB, Scalea TM, Rasmussen TE. A clinical series of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for hemorrhage control and resuscitation: J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(3):506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duchesne J, Costantini TW, Khan M, Taub E, Rhee P, Morse B, Namias N, Schwarz A, Graves J, Kim DY, et al. The effect of hemorrhage control adjuncts on outcome in severe pelvic fracture: A multi-institutional study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87(1):117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer DE, Mont MT, Harvin JA, Kao LS, Wade CE, Moore LJ. Catheter distances and balloon inflation volumes for the ER-REBOATM catheter: A prospective analysis. Am J Surg. 2020;219(1):140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadek S, Lockey DJ, Lendrum RA, Perkins Z, Price J, Davies GE. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in the pre-hospital setting: An additional resuscitation option for uncontrolled catastrophic haemorrhage. Resuscitation. 2016;107:135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lendrum R, Perkins Z, Chana M, Marsden M, Davenport R, Grier G, Sadek S, Davies G. Pre-hospital Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) for exsanguinating pelvic haemorrhage. Resuscitation. 2019;135:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamhaut L, Qasim Z, Hutin A, Dagron C, Orsini J-P, Haegel A, Perkins Z, Pirracchio R, Carli P. First description of successful use of zone 1 resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in the prehospital setting. Resuscitation. 2018;133:e1–e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin MJ, Holcomb JB, Polk T, Hannon M, Eastridge B, Malik SZ, Blackman VS, Galante JM, Grabo D, Schreiber M, et al. The “Top 10” research and development priorities for battlefield surgical care: Results from the Committee on Surgical Combat Casualty Care research gap analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87(1S Suppl 1):S14–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsilimigras DI, Sigala F, Karaolanis G, Ntanasis-stathopoulos I, Spartalis E, Spartalis M, Patelis N, Papalampros A, Long C, Moris D. Cytokines as biomarkers of inflammatory response after open versus endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a systematic review. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39(7):1164–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnaoutoglou E, Kouvelos G, Koutsoumpelis A, Patelis N, Lazaris A, Matsagkas M. An Update on the Inflammatory Response after Endovascular Repair for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:945035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziegenfuss T, Wanner GA, Grass C, Bauer I, Schüder G, Kleinschmidt S, Menger MD, Bauer M. Mixed agonistic-antagonistic cytokine response in whole blood from patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(3):279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bown MJ, Nicholson ML, Bell PR, Sayers RD. Cytokines and inflammatory pathways in the pathogenesis of multiple organ failure following abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg Off J Eur Soc Vasc Surg. 2001;22(6):485–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mühl H. Pro-Inflammatory Signaling by IL-10 and IL-22: Bad Habit Stirred Up by Interferons? Front Immunol. 2013;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Döcke W-D, Asadullah K, Belbe G, Ebeling M, Höflich C, Friedrich M, Sterry W, Volk H-D. Comprehensive biomarker monitoring in cytokine therapy: heterogeneous, time-dependent, and persisting immune effects of interleukin-10 application in psoriasis. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85(3):582–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koo A, Liang IYS. Blood flow in hepatic sinusoids in experimental hemorrhagic shock in the rat. Microvasc Res. 1977;13(3):315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veith NT, Histing T, Menger MD, Pohlemann T, Tschernig T. Helping prometheus: liver protection in acute hemorrhagic shock. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(10):206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clemens MG, Bauer M, Pannen BHJ, Bauer I, Zhang JX. Remodeling of hepatic microvascular responsiveness after ischemia/reperfusion. Shock. 1997;8(2):80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marzi I, Bauer M, Secchi A, Bahrami S, Redi H, Schlag G. Effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha on leukocyte adhesion in the liver after hemorrhagic shock: an intravital microscopic study in the rat. Shock Augusta Ga. 1995;3(1):27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lallemand MS, Moe DM, McClellan JM, Smith JP, Daab L, Marko S, Tran N, Starnes B, Martin MJ. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for major abdominal venous injury in a porcine hemorrhagic shock model. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(2):230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Izawa Y, Hishikawa S, Matsumura Y, Nakamura H, Sugimoto H, Mato T. Blood flow of the venous system during resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta: Noninvasive evaluation using phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88(2):305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hörer T, DuBose JJ, Rasmussen TE, White JM, Davidson A, Williams T, eds. Partial REBOA In: Endovascular Resuscitation and Trauma Management. Hot Topics in Acute Care Surgery and Trauma. Cham: Springer; 2020:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sondeen JL, Coppes VG, Holcomb JB. Blood pressure at which rebleeding occurs after resuscitation in swine with aortic injury. J Trauma. 2003;54(5 Suppl):S110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1: Supraceliac aortic exposure.

Aorta (red arrow), cranial (blue asterisk).

Supplemental Digital Content 3: Survival trends.

Kaplan-Meier analysis displaying time to death from injury for no intervention control, partial ER-REBOA and partial pREBOA-PRO. Two full-occlusion ER-REBOA and pREBOA-PRO controls were included from the study model development.

Supplemental Digital Content 5: Cytokine trends per partial REBOA type.

Asterisk denotes statistically significant difference between trends.

Supplemental Digital Content 6: Cytokine trend correlations. Raw values were plotted and correlated using Spearman test. A Spearman coefficient (Rs) with a value larger than 0.7 indicates a strong correlation.

Supplemental Digital Content 4: Photomicrographs of representative histologic sections of tissues from animals’ post supraceliac aortic injury that have undergone no intervention (Control), partial ER-REBOA or partial pREBOA-PRO. Tissues stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin stain and visualized at (A) 20X or (B) 10X magnification. Liver sections with diffuse mild atrophy of centrilobular hepatic cords in Control, centrilobular degeneration and necrosis with increased circulating neutrophils in ER-REBOA and mild neutrophilic inflammation over background lymphoplasmacytic/eosinophilic (l/e) inflammation in pREBOA-PRO. Kidneys with similar level of background l/e interstitial nephritis in all three groups and mild levels of acute tubular necrosis in ER-REBOA. Essentially normal neck (Above) and thigh adductor (Below) skeletal muscles in Control. Both partial pREBOA-PRO and ER-REBOA with comparable levels of occasional mild necrosis Above and mild-moderate skeletal muscle necrosis Below the device insertion site. Small intestine sections with similar background diffuse l/e inflammation and lamina propria edema in all three groups.