Abstract

Background

Off-target drift of pesticides from farms increases the risk of pesticide exposure of people living nearby. Cholinesterase inhibitors (i.e. organophosphates and carbamates) are frequently used in agriculture and inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity. Greenhouse agriculture is an important production method, but it is unknown how far pesticide drift from greenhouses can extend and expose people living nearby.

Methods

This study included 1156 observations from 3 exams (2008, Apr 2016 and Jul-Oct of 623 children aged 4-to-17 years living in agricultural communities in Ecuador. AChE, a physiological marker of cholinesterase inhibitor exposure, was measured in blood. Geographic positioning of greenhouses and homes were obtained using GPS receivers and satellite imagery. Distances between homes and the nearest greenhouse edge, and areas of greenhouse crops within various buffer zones around homes were calculated. Repeated-measures regression adjusted for hemoglobin and other covariates estimated change in AChE relative to distance from greenhouses.

Results

The pooled mean (SD) of AChE activity was 3.58 U/mL (0.60). The median (25th-75th %tile) residential distance to crops was 334 m (123, 648) and crop area within 500 m of homes (non-zero values only) was 18,482 m2 (7115, 61,841). Residential proximity to greenhouse crops was associated with lower AChE activity among children living within 275m of crops (AChE difference per 100m of proximity [95% CI]= −0.10 U/mL [−0.20, −0.006]). Lower AChE activity was associated with greater crop area within 500m of homes (AChE difference per 1000m2 [95% CI]= −0.026 U/mL [−0.040, −0.012]) and especially within 150m (−0.037 U/mL [−0.065, −0.007]).

Conclusions

Residential proximity to floricultural greenhouses, especially within 275m, was associated with lower AChE activity among children, reflecting greater cholinesterase inhibitor exposure from pesticide drift. Analyses of residential proximity and crop areas near homes yielded complementary findings. Mitigation of off-target drift of pesticides from crops onto nearby homes is recommended.

Keywords: Pesticide drift, area, residential proximity, organophosphate, carbamate, Ecuador

Introduction

Cholinesterase inhibitor insecticides, such as organophosphates (OP) and carbamates, are widely used pesticides in agriculture. Children growing up near agricultural crops are at increased risk of OP exposure due to off-target drift from pesticides. Residential proximity to treated crops has been shown to play a significant role in pesticide exposure of its residents. For instance, residential proximity to treated crops was found to be associated with greater OP pesticide present in home dust and air (Lu et al., 2000; McCauley et al., 2001; Quandt et al., 2004; Ramaprasad et al., 2009; Simcox et al., 1995), and with higher urinary biomarkers of OP exposure among children (Coronado et al., 2011; Loewenherz et al., 1997; Lu et al., 2000). However, these associations were not observed in all studies (Curl et al., 2002; Koch et al., 2002). These existing studies have focused on open-field agriculture. However, a considerable amount of agriculture occurs within greenhouses, in which pesticide fumigation is concentrated within the greenhouse. The aerosolized pesticides can escape through air circulation openings in the greenhouse structure and, therefore, have the potential to reach homes nearby.

Cholinesterase inhibitor insecticides act by inhibiting the activity of both butyrylcholinesterase and acetylcholinesterase (AChE). Erythrocytic AChE activity measurement is a standard assessment of cholinesterase inhibitor monitoring for agricultural workers, and has been found to be a valid marker of exposure in epidemiological studies of children (Suarez-Lopez et al., 2012; Jose R. Suarez-Lopez et al., 2013; Suarez-Lopez et al., 2017). Compared with OP metabolites in urine, AChE is much more stable marker of exposure and has small intraindividual variation over time (Bradman et al., 2013; Lefkowitz et al., 2007). To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the association between household distance from treated agricultural fields (including open or greenhouse agriculture) and AChE activity as biomarkers of cholinesterase inhibitor pesticide exposure in children.

OP exposure has been associated with a multitude of negative health effects in children. Prenatal and early life exposure to OP pesticides have been associated with cognitive and neurobehavioral deficits (Bouchard et al., 2011; Engel et al., 2007; Lizardi et al., 2008; Marks et al., 2010; Rauh et al., 2015; Jose R Suarez-Lopez et al., 2013), and respiratory impairments (Raanan et al., 2015). Additionally, we recently observed that residential proximity to greenhouse agriculture was associated with altered blood pressure and neurobehavioral performance of children (Friedman et al., 2019; Suarez-Lopez et al., 2018) after adjustment for multiple covariates.

In this study, we aimed to characterize the associations between residential proximity to greenhouse flower crops and AChE activity. We hypothesized that closer proximity of children’s homes to crops where pesticides are used and greater areas of crops near homes were associated with lower AChE activity (indicating greater pesticide exposure) among children living in agricultural communities in Pedro Moncayo County, Pichincha, Ecuador.

Methods

Study description

The study of Secondary Exposures to Pesticides among Children and Adolescents (ESPINA, Exposición Secundaria a Plaguicidas en Niños y Adolescentes) is a prospective cohort study of children, established in 2008, aimed at understanding the effects of subclinical pesticide exposure on child development in Pedro Moncayo County, Pichincha, Ecuador. The ESPINA study was developed in response to community needs defined through participatory processes. Ecuador is one of the largest exporters of roses and much of the country’s production is situated in Pedro Moncayo County, employing approximately 21% of adults (Suarez-Lopez et al., 2012). Flower plantations frequently use various pesticides including insecticides (organophosphates, neonicotinoids and pyrethroids), fungicides and, to lesser extent, herbicides (Grandjean et al., 2006; Handal et al., 2016; Harari, 2004; Suarez-Lopez et al., 2017). Rose production within Pedro Moncayo County is carried out within greenhouses that have air circulation vents or windows, which can allow the escape of fumigated pesticides during and after spraying. In 2016, there were no organic flower plantations in Ecuador registered with the Ministry of Agriculture and Cattle Raising.

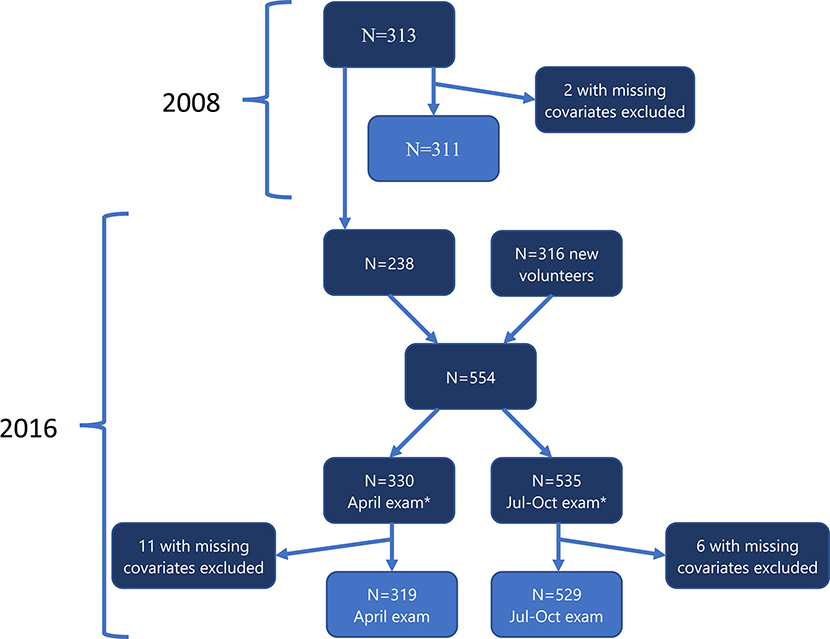

In 2008, we examined 313 boys and girls, ages 4–9 years, between July and August, who resided in the agricultural County of Pedro Moncayo, Pichincha province, Ecuador. In 2016, we examined 554 participants, ages 12–17 years, which included 238 participants examined in 2008 and 316 new volunteers. Of these 554 participants, 535 were examined between July and October 2016, and 331 were examined in April (311 participants were examined in both April and July-October exams). The present analyses include 311 participants examined in 2008, 319 participants examined in April 2016 and 529 participants examined in July-October 2016 who had all covariates of interest (Figure 1). Our longitudinal analyses include information of 623 participants (98.6% of 629), including 1156 observations collected during the 3 exam periods.

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart.

* 311 participants examined in both examinations in 2016

In 2008, most participants were recruited using the 2004 Survey of Access and Demand of Health Services in Pedro Moncayo County. This survey included information of 71% of the County’s population and was conducted by Fundación Cimas del Ecuador in collaboration with the Governments of Rural Parishes of Pedro Moncayo and community residents. Some ESPINA participants were also recruited through community announcements provided by leaders and governing councils, and by word-of-mouth. The ESPINA study sought a balanced distribution of participants living with a flower plantation worker and participants not living with any agricultural workers. To be eligible to participate, participants must have: A) lived with a flower plantation worker for at least one year, or B) never lived with an agricultural worker, never inhabited a house where agricultural pesticides were stored and never have had previous contact with pesticides. Additional details about the 2008 study methodology have been published (Suarez-Lopez et al., 2012). As in 2008, new participants in 2016 were selected and invited to participate using the System of Local and Community Information (SILC) developed by Fundacion Cimas del Ecuador, which includes information of the 2016 Pedro Moncayo County Community Survey (formerly the Survey of Access and Demand of Health Services in Pedro Moncayo County). In 2008 and 2016, all participants reported not working in agriculture.

Data collection

In both the 2008 and 2016 examinations, parents and other adult residents were interviewed at their homes to obtain socioeconomic information, demographic characteristics of household members and prevalence of pesticide use information at the household level. In 2008, children were examined in 7 schools of Pedro Moncayo County during the summer months when school was out of session, to ensure a quiet, familiar, and child-friendly environment that was easily accessible. In 2016, children were examined twice: once in April and again between July and October. As in 2008, examinations were conducted in schools during the summer closure or during weekends.

Examiners were unaware of participants’ pesticide exposure status. Children’s height was measured to the nearest 1 mm following recommended procedures (World Health Organization, 2008), and weight was measured using a digital scale (Tanita model 0108MC; Tanita Corporation of America, Arlington Heights, IL, USA). We calculated height-for age z-scores using the World Health Organization (WHO) growth standards (World Health Organization Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006).

Erythrocyte AChE activity and hemoglobin concentration were measured from a single finger stick blood sample using the EQM Test-mate ChE Cholinesterase Test System 400 (EQM AChE Erythrocyte Cholinesterase Assay Kit 470) Kit 470 (EQM, Cincinnati, OH, USA) in all 3 examination periods.

Geographical coordinates of childrens’ homes were measured using portable global positioning systems (GPS) in 2004, 2006, 2010 and 2016 by Fundacion Cimas del Ecuador, as part of the SILC). Flower plantation edges (areal polygons) were created using satellite imagery from 2006 and 2016. Distance between the child’s home and the nearest point of flower plantation perimeter was calculated using ArcGIS 9.3 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA). To further quantify the amount of potential exposure from pesticide drift, we calculated the areas of flower plantations within 150m, 151–300m, and 301–500m from participants’ homes.

The ESPINA study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Minnesota, The University of California San Diego, Universidad San Francisco de Quito and the Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador and is endorsed by the Local Governments of Pedro Moncayo County. Informed consent, parental authorization of child participation and assent of child participants older than 7 years of age were obtained.

Statistical Analysis

Child participant characteristics were calculated as mean (SD) for normally distributed variables or median (25th-75th percentile) for skewed variables across strata of household distances to the nearest floricultural greenhouse planation edge. P-trends were calculated using simple linear regressions to evaluate a significant change in participants’ characteristics by the log-transformed residential distance to the nearest flower crop assessed as a continuous variable.

The relationship between children’s AChE activity and proximity to treated floricultural greenhouses across all years was evaluated using repeated-measures regression (generalized linear mixed model) using a Toeplitz correlation matrix. To calculate the associations per 100m of residential proximity, we divided the distance variable by 100 and conducted a natural log-transformation given its skewed distribution. This value was then multiplied by −1 to reflect proximity rather than distance. The regression estimates of proximity were then multiplied by ln(2) to calculate the associations per 100m of proximity. We evaluated for threshold effects by stratifying the associations across various categories of distances between 150 and 300m, and the smallest distance category in which an association was observed (0–275m) was selected. We assessed time effect through multiplicative term (exposure time exposure*time). We then characterized the associations between residential distance to crops and AChE activity by distance categories including 0–275m, 276–500m and >500m. We graphed the associations between residential distances to crops and AChE activity by plotting the least squares means adjusted in model 2 (see below), calculated with GLMM as above, of AChE activity for 200 quantiles of distance. Considering the threshold observed in this association, we plotted the association using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) with smoothing=0.5, alpha 0.05, based on the adjusted least squares means data.

We also characterized associations between areas of flower crops near homes and AChE activity using repeated-measures regression. Areas of crops near homes is a more precise construct of pesticide drift than residential proximity as it is a function of both proximity to crops and the size of the nearby crop (larger crop areas require greater pesticide use and, hence, greater potential for drift). Considering that associations between residential distance to crops and AChE activity were significant within 275m, we assessed the associations between AChE activity and areas of greenhouse crops within 300m of homes. Areas of crops were divided by 1000 to estimate associations per 1000m2. This variable was then natural log-transformed given its skewed distribution. The regression estimates for the area variable was then multiplied by ln(2) to calculate the associations per 1000m2 of crops within 300m of homes. We graphed the associations between areas of greenhouses within 500m and AChE activity association using adjusted least squares means (model 2 in repeated measures regression) for 200 ranked groups and plotted the slope of the association based on the log-transformed area variable without ln(2) multiplication as the areas of crops in the x-axis were expressed as log-transformed units due to the wide range of this variable (0 to 425,006 m2).

All associations were tested using two adjustment models: model 1 adjusted for age, gender, parental education, height-for-age z-score, hemoglobin concentration, and examination year. Model 2 further adjusted for flower worker cohabitation, pesticide use within the residential property lot (including inside the home) for personal or agricultural reasons, neighbor use of pesticides on their property for agricultural purposes (as reported by the parents of participants), and examination date. For the variables of pesticide use in the residence and by neighbors we grouped values in which the respondent did not know if pesticides were use and missing in order to include all participants in the analyses. The number of participants within this combined category are shown in Table 1. This variable was analyzed as a categorical variable in all analyses. We adjusted for examination date to account for seasonal effects on pesticide use considering that floricultural production and pesticide use in Pedro Moncayo County fluctuates according to the demand for flowers for certain holidays (i.e. Thanksgiving, Christmas, Valentine’s Day, and Mother’s Day). This results in heightened flower production and pesticide-use periods from October to April followed by periods of low flower production and pesticide-use from late May to September. Among participants examined in 2008 of the ESPINA study, we previously observed that time after the Mother’s Day harvest was positively associated with acetylcholinesterase activity among children living near floricultural crops (Suarez-Lopez et al., 2017). These findings suggested that the pesticide exposure levels of children examined sooner after the harvest were greater than those of children examined later. Time after the end of the Mother’s Day Harvest (examination date) for 2008 and 2016 was calculated by subtracting the approximate end date of the Mother’s Day Harvest (00:00am on May 8, 2008 or 00:00am on May 5, 2016) from the date and start time of the participant’s examination.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n=623, nobservations= 1156).

| All participants | Quartiles of residential distance to the nearest flower plantation edge (m)* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 0–4827m | 0–122m | 123–330m | 331–641m | 642–4827m | P-trend |

| Nobservations | 1156 |

290 |

287 |

290 |

289 |

|

| Age, years | ||||||

| 2008a | 6.6 (1.6) | 6.7 (1.7) | 6.4 (1.5) | 6.8 (1.6) | 6.4 (1.6) | 0.32 |

| Apr 2016b | 14.2 (1.8) | 14.3 (1.8) | 14.1 (1.9) | 14.3 (1.9) | 14.2 (1.8) | 0.35 |

| Jul-Oct 2016c | 14.5 (1.8) | 14.2 (1.8) | 14.4 (1.8) | 14.6 (1.8) | 14.6 (1.7) | 0.54 |

| Gender, male, % | ||||||

| 2008a | 51 | 53 | 56 | 47 | 46 | 0.51 |

| Apr 2016b | 50 | 50 | 49 | 49 | 53 | 0.58 |

| Jul-Oct 2016c | 49 | 43 | 49 | 50 | 55 | 0.26 |

| Parental education, years | ||||||

| 2008a | 7.5 (3.7) | 6.6 (3.6) | 8.0 (3.4) | 8.1 (4.0) | 6.4 (3.4) | 0.06 |

| Apr 2016b | 8.1 (3.6) | 8.2 (3.5) | 8.2 (4.0) | 8.8 (3.7) | 7.4 (2.9) | 0.03 |

| Jul-Oct 2016c | 8.1 (3.5) | 8.2 (3.4) | 8.0 (3.6) | 8.6 (3.8) | 7.7 (3.0) | 0.34 |

| Lived with flower worker, % | ||||||

| 2008a | 49 | 51 | 54 | 45 | 48 | 0.44 |

| Apr 2016b | 47 | 41 | 44 | 58 | 46 | 0.96 |

| Jul-Oct 2016c | 49 | 46 | 46 | 59 | 48 | 0.93 |

| Pesticide use within the residential property, %** | ||||||

| 2008a | 14 | 5 | 11 | 16 | 22 | 0.10 |

| Apr 2016b | 21 | 15 | 28 | 20 | 24 | 0.83 |

| Jul-Oct 2016c | 20 | 13 | 22 | 18 | 29 | <0.01 |

| Neighbor use of pesticides on their property*** | ||||||

| 2008a | 29 | 23 | 30 | 23 | 39 | 0.04 |

| Apr 2016b | 57 | 46 | 64 | 48 | 72 | 0.10 |

| Jul-Oct 2016c | 53 | 52 | 51 | 41 | 68 | 0.04 |

| Examination date**** | ||||||

| 2008a | 85.0 (10.9) | 85.8 (9.0) | 84.3 (7.5) | 88.1 (9.2) | 81.1 (15.9) | <0.01 |

| Apr 2016b | −12.3 (5.5) | −11.8 (5.6) | −12.0 (4.9) | −10.1 (6.0) | −14.9 (4.2) | 0.07 |

| Jul-Oct 2016c | 102.7 (18.7) | 102.5 (18.7) | 97.4 (14.4) | 104.6 (22.8) | 105.9 (17.3) | 0.22 |

| Height-for-age Z-score, SD | ||||||

| 2008a | −1.25 (0.98) | −1.21 (0.99) | −1.38 (0.98) | −1.31 (0.95) | −1.01 (1.01) | 0.20 |

| Apr 2016b | −1.59 (0.95) | −1.50 (0.99) | −1.62 (0.87) | −1.66 (0.89) | −1.58 (1.02) | 0.55 |

| Jul-Oct 2016c | −1.49 (0.93) | −1.40 (0.92) | −1.50 (0.93) | −1.51 (0.84) | −1.55 (1.02) | 0.23 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | ||||||

| 2008a | 12.6 (1.2) | 12.7 (1.1) | 12.6 (1.1) | 12.9 (1.2) | 12.3 (1.2) | 0.01 |

| Apr 2016b | 13.0 (1.3) | 13.1 (1.2) | 12.9 (1.1) | 12.9 (1.3) | 13.1 (1.5) | 0.70 |

| Jul-Oct 2016c | 13.0 (1.2) | 12.9 (1.0) | 13.0 (1.3) | 13.0 (1.2) | 12.9 (1.2) | 0.81 |

| Crop areas within quartiles of distances from homes (m)***** | ||||||

| 0–150ma, (n=60) | 989 (492, 3014) | 1809 (785, 4458) | 261 (43.4, 879.) | - | - | - |

| 0–150mb, (n=105) | 3496 (1495, 9915) | 4377 (2007, 13626) | 633 (300, 645) | - | - | - |

| 0–150mc, (n=96) | 3496 (1468, 9915) | 4149 (2039, 10958) | 633 (300, 645) | - | - | - |

| 151–300ma, (n=127) | 3617 (1121,10620) | 4650 (600, 20826) | 3554 (1232, 5982) | - | - | - |

| 151–300mb, (n=158) | 8421 (2654, 42492) | 21910 (2762, 67942) | 5972 (2353, 16797) | - | - | - |

| 151–300mc, (n=145) | 8480 (2847, 42492) | 24815 (2654, 67892) | 6325 (2847, 17971) | - | - | - |

| 301–500ma, (n=180) | 6965 (2107, 223912) | 18119 (6716, 56582) | 7116 (3357, 23744) | 25612 (592, 7246) | - | - |

| 301–500mb, (n=184) | 20592 (7884, 912223) | 91223 (16521, 190586) | 15148 (7116, 55150) | 10254 (2196, 16840) | - | - |

| 301–500mc, (n=171) | 21425 (7922, 91223) | 91223 (18300,188636) | 19759 (7845, 55150) | 10254 (2196,16840) | - | - |

Values are mean (SD), percent or median (25th–75th percentile).

Quartile cut-offs based on the pooled values for all exam periods.

Proportion calculations exclude 58 (5%) participants who did not know if they used pesticides at home or had missing values.

Proportion calculations exclude 152 (13%) participants who did not know if their neighbors used pesticides for agricultural purposes or had missing values.

Days after the Mother’s Day flower harvest (end of a peak pesticide spray period).

Among participants with non-zero crop area values

Summer examination in 2008 N= 311

April examination in 2016 N= 319

July-October examination in 2016 N= 529

Results

Participant characteristics

Both the pooled crude mean AChE activity and age-and-hemoglobin-adjusted pooled mean AChE activity of participants were 3.58 U/mL (SD= 0.60). The median (25th-75th %tile) of residential distance to homes was 330 m (121, 645) and of crop areas within 500 m of homes was 18,482 m2 (7115, 61841, among those with non-zero values, Nobs=716). When compared with the WHO Child Growth Standards, children in our study were shorter for their age across the three examination periods with mean height-for-age z-scores of −1.25 SD (SD=0.98) in 2008 and −1.49 SD (SD=0.93) in 2016 (World Health Organization Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group 2006). In 2008, there were 681 hectares of greenhouses in Pedro Moncayo County, and in 2016 the land area of greenhouses almost tripled in size (1534 hectares).

In all three examinations, we observed inverse associations of parental education and examination date with residential distance to the nearest flower plantation edge, whereas positive associations were observed with pesticide use within the residential property and neighbor use of pesticides. There were no statistically significant differences in participants’ age, gender, cohabitation with flower workers, or height-for-age z-score by residential distance to the nearest flower crop (Table 1).

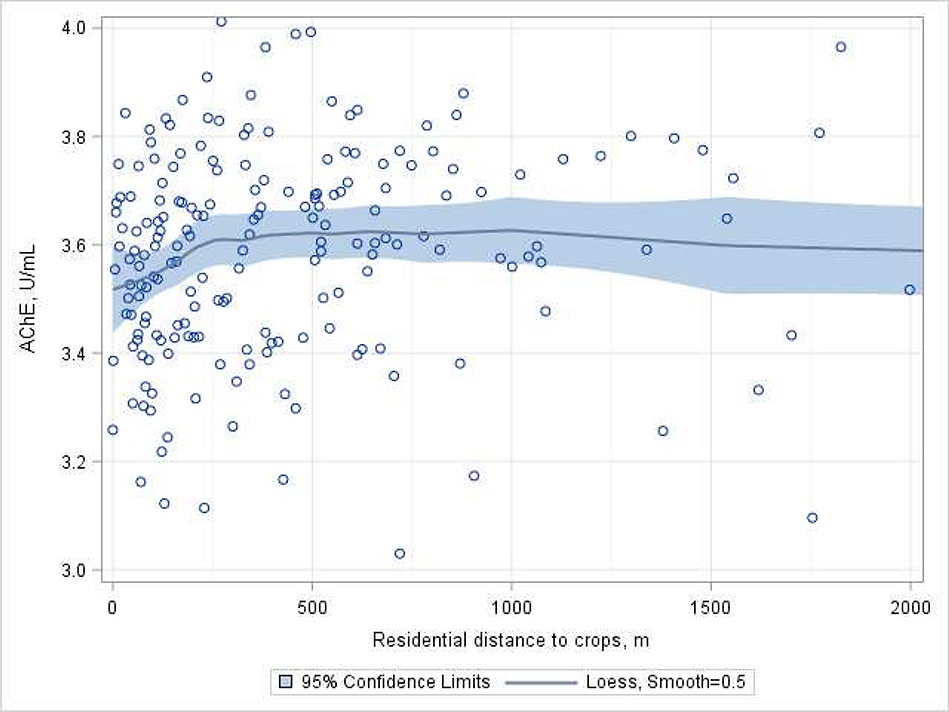

AChE activity and household proximity to the nearest greenhouse crop

Overall, AChE activity was not significantly associated with residential proximity to the nearest flower crops (Table 2). However, in our exploration of threshold effects, we observed that residential proximity to crops was statistically inversely related to AChE activity among participants who lived within 275 m from crops (Model 2: AChE difference per 100 m of proximity [95% CI] = −0.10 U/mL [−0.200, −0.006]). This threshold was also evident in Figure 2. Associations were not observed among participants living farther than 275m from crops. There was no effect of time on this association overall (pdistance*time =0.16) nor among only among participants living within 275m of a crop (pdistance*time =0.39).

Table 2.

Longitudinal associations between AChE activity and household proximity to the nearest flower crop perimeter among children.

| Difference of AChE activity in U/mL (95% CI) per 100m of residential proximity to crops |

||

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Overall (N=623, Nobs=1156) | −0.015 (−0.046, 0.016) | −0.015 (−0.046, 0.015) |

| By categories of residential proximity to greenhouse crops | ||

| ≤275m (N=300, Nobs=538) | −0.096 (−0.197, 0.004) | −0.103 (−0.200, −0.006) |

| 276 – 500m (N=137, Nobs=192) | −0.004 (−0.541, 0.532) | −0.230 (−0.751, 0.290) |

| >500 m (N=253, Nobs=426) | 0.061 (−0.516, 0.661) | 0.094 (−0.010, 0.178) |

Model 1 adjustments: age, gender, parental education, height-for-age z-score, hemoglobin concentration and examination year.

Model 2 adjustments: Model 1 + cohabitation with a floricultural worker, pesticide use within the residential property lot, neighbor use of pesticides on their property, and examination date (days after a peak exposure period).

Figure 2.

Associations between residential distance to the nearest flower crop and AChE activity among children (N=621, Nobs= 1149). Data points for children living at >2000m from a crop are not displayed.

Circles represent the least squared means (based on repeated-measures GEE) of AChE activity for 200 quantiles of distance, adjusted for age, gender, parental education, height-for-age z-score, hemoglobin concentration, examination year, cohabitation with a floricultural worker, pesticide use within the residential property, neighbor use of pesticides on their property lot and examination date (days after a peak exposure period). The line represents the adjusted slope of the association (LOESS) based on the adjusted least squared means, and blue areas represent the 95% CI.

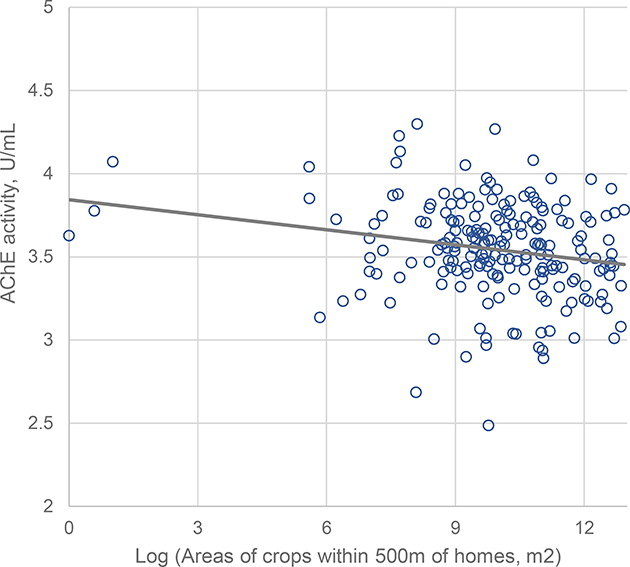

AChE activity and surface area of greenhouse crops within buffers around homes

AChE activity was inversely associated with areas of flower crops within 500 m of homes in both models 1 and 2 (Table 3 and Figure 3). This association was strongest among participants who lived within 150m of crops (for every 1000m2 increase in crop areas there was a decrease in AChE activity by 0.037 U/mL (95% CI: −0.065, −0.007). Significant but weaker associations were observed among children who lived within 151–300m and 301–500m (Model 2, AChE difference per 1000 m2 crops areas ≈ −0.027 U/mL for both distance categories). There was no effect of time on this association among participants living within 150m (pareas*time =0.16) nor 500m (pareas *time =0. 61).

Table 3.

AChE activity difference and areas of greenhouse crops within buffers of various sizes around homes (n=623, n observations=1156).

| Buffer radius around homes | Difference of AChE activity (U/mL) per 1000m2 of areas of crops within various buffer zones, β (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| 0–150m | −0.034 (−0.065, −0.004) | −0.037 (−0.065, −0.007) |

| 151–300 m | −0.027 (−0.045, −0.008) | −0.026 (−0.043, −0.007) |

| 301–500 m | −0.028 (−0.043, −0.013) | −0.027 (−0.042, −0.013) |

| 0–500 m | −0.027 (−0.041, −0.013) | −0.026 (−0.040, −0.012) |

Model 1 adjustments: age, gender, parental education, height-for-age z-score, hemoglobin concentration and examination year.

Model 2 adjustments: Model 1 + cohabitation with a floricultural worker pesticide use within the residential property lot, neighbor use of pesticides on their property, and examination date (days after a peak exposure period).

Figure 3.

Longitudinal associations between areas of flower crops within 500m of homes and AChE activity among children (N=621, Nobs= 1149).

Circles represent the least squared means (based on repeated-measures GEE) of AChE activity for 200 quantiles of crop areas, adjusted for age, gender, parental education, height-for-age z-score, hemoglobin concentration, examination year, cohabitation with a floricultural worker, pesticide use within the residential property lot, neighbor use of pesticides on their property and examination date (days after a peak exposure period). The line represents the adjusted slope of the linear association.

Off-target drift of pesticides from greenhouses may reach people living nearby Cholinesterase inhibitor pesticides inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity We examined 623 children (3 exams: 1156 observations) living near agriculture Home proximity to crops (within 275m) was associated with lower child AChE activity Greater crop areas within 500m (especially <150m) of homes associated with lower AChE

Discussion

Our study provides compelling longitudinal evidence of off-target pesticide drift from floricultural greenhouses onto homes nearby by way of a biomarker of exposure. We found that two constructs of agricultural pesticide drift onto nearby homes (greater home proximity to crops and area of flower crops around homes) were significantly associated with lower AChE activity, a stable physiological marker of exposure to cholinesterase inhibitor pesticides, assessed from childhood through adolescence. These associations remained independent after controlling for potential confounders, including other plausible exposure sources such as cohabitation with agricultural workers and length of examination time after a known peak pesticide spray season. This is the first study to characterize greenhouse pesticide agricultural drift using a biomarker of exposure to our knowledge. In this setting, it is appropriate to estimate that most greenhouses receive pesticide treatments as the greenhouses are used almost exclusively for the production of roses requiring frequent pesticide fumigations, and in 2016 there were no registered organic flower plantations in Ecuador.

We observed that residential proximity to greenhouse crops was inversely related to AChE activity, but only among children living within 275 m (approximately 1.5–3 city blocks) of a crop. The distance of pesticide drift observed in our study is within the range of distances within which prior studies observed increased quantitative markers of exposures in homes and humans (Coronado et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2000; Simcox et al., 1995; Ward et al., 2006). The distance of pesticide drift varies by crop and location. For instance, in Washington state, the median concentration of pesticide metabolites in children’s urine and the median pesticide concentrations in home dust were significantly higher among children living within 60m to treated tree fruits orchards than those who lived farther (Lu et al., 2000). However, the off-target pesticide drift in that area likely extends beyond 60m as the orchards were not confined within greenhouses and there was a 20% reduction in urinary pesticide metabolites for each mile of residential distance to treated orchards (Coronado et al., 2011). Greater areas of corn and soybean crops within 750 m from children’s home homes have also been associated higher agricultural herbicide concentrations in household dust in the United States (Ward et al., 2006). Our study findings support the growing evidence that off-target drift is an important source of pesticide exposure for people living in agricultural communities and provides new data on greenhouse agriculture. The Ecuadorian flower industry uses greenhouses to protect their production which can reduce the amount of off-target drift of pesticides into their surroundings as compared with open air crops. Nonetheless, greenhouses have ventilation openings that do allow air to circulate through and out of green houses and drift enough pesticides onto homes nearby. Worldwide, many types of crops involve the use of greenhouses such as flowers, tomatoes, cucumbers, mixed greens, bell peppers, and eggplants. The findings from our study may be applicable to such agricultural production.

We also observed that AChE activity was inversely associated to a related but different construct of pesticide drift: areas of pesticide-treated greenhouse crops within various distances (buffer zones) between homes. As hypothesized, the strongest associations were observed among participants living closest to the crops (0–150m buffer), but it was noteworthy that areas of greenhouse crops were still inversely associated with AChE activity on categories as far as 500m. These findings suggest that areas of crops near homes is a good and, perhaps, more sensitive construct of pesticide drift than residential proximity, considering that AChE associations with the latter variable were only observed within 275m. The consistency of findings between these 2 distinct but related constructs of exposure strengthens our findings. Residential proximity to crops and areas of crops near homes are useful constructs of chronic pesticide exposure in agricultural settings and provide practical information about the distances in which populations may have an increased risk of pesticide exposure and/or adverse health.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate the extent of pesticide drift from agricultural greenhouses onto nearby homes, and the first to characterize this association longitudinally using AChE activity, a physiological marker of exposure. Erythrocytic AChE activity is a more stable indicator of exposure to cholinesterase inhibitors from the application sites than pesticides metabolites in bodily fluids. (Lefkowitz et al., 2007; Suarez-Lopez et al., 2017) and is a better indicator of long-term exposure as it is estimated that it may take up to 82 days for AChE levels to return to baseline levels after irreversible inhibition by organophosphates (Mason, 2000). Considering that in agriculture mixtures of multiple classes of pesticides are frequently used, it is plausible that AChE activity may also be indirectly marking exposure to other classes of pesticides besides cholinesterase inhibitors.

Children in agricultural communities have an increased risk of pesticide exposures due to their distinct physical, behavioral, and developmental characteristics. Additionally children have lower levels of detoxifying enzymes that breakdown neurotoxicants which rendered them more susceptible to pesticide exposure (Faustman et al., 2000; Holland et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2002). Prenatal and childhood exposure to OP pesticides have been associated with deficits in cognition, neurobehavior and alterations in lung function (Bouchard et al., 2010; Lizardi et al., 2008; Marks et al., 2010; Raanan et al., 2015). Furthermore, studies (including ESPINA) have described alterations in neurocognitive performance, developmental delays, autism spectrum disorders and blood pressure among children living close to agricultural crops where pesticides were sprayed (Carmichael et al., 2014; Ehrenstein et al., 2019; Friedman et al., 2019; Gunier et al., 2016; Rowe et al., 2016; Samsuddin et al., 2016; Shelton et al., 2014; Suarez-Lopez et al., 2018).

The present analyses have some limitations. Firstly, we did not account for the effect of prevailing winds and rain on these associations. This provides potential for non-differential misclassification of the amount of pesticide drift from greenhouses to homes and may have biased our findings towards the null (Gordis, 2014). Also, while most floricultural production in Pedro Moncayo County consists of roses which are grown inside greenhouses, production of other flowers can also occur in non-enclosed fields which may be located near the greenhouses. It is, therefore, plausible that some of the pesticide drift from crops, and hence the associations observed in this study, may be a result of both greenhouse and open field floricultural production. However, the effect of this is expected to be small as the amount of open-field floricultural production in this County is small compared to that of rose production in greenhouses. An additional limitation is the lack of geospatial information of other non-floricultural crops that use pesticides, the adjustment of which would improve the precision of the present findings.

Further studies to characterize the associations between metabolites/parent compounds of organophosphates and other pesticides in urine or dust are warranted to understand which specific pesticides are more prone to drift from crops. The floricultural industry in Pedro Moncayo frequently uses various pesticides including insecticides (organophosphates, neonicotinoids and pyrethroids), many classes of fungicides and to lesser extent, herbicides (Grandjean et al., 2006; Handal et al., 2016; Harari, 2004; Suarez-Lopez et al., 2017).

This study has several strengths. The ESPINA study is among the largest prospective studies of children growing up in agricultural settings and the present analyses involve data from 3 examination periods over an 8-year follow-up from childhood thru adolescence. As a result of ESPINA’s recruitment plan, this study has a wide distribution of participants’ residential distance to crops, with many children living in close proximity (<100m) to flower crops which allowed us to estimate effect sizes at short distances. Additionally, our analyses account for date of AChE assessment in relation to time after a known pesticide spray season (examination date after the Mother’s Day harvest), which refines the estimate of the association considering the interplay between peak pesticide spray periods and higher amounts of off-pesticide drift from crops. Apart from the April 2016 examination and children examined in October 2016, participants examined in 2008 (July through August) and between July through September 2016 were examined during periods of relatively low and homogeneous flower production and pesticide use. The relatively low use of pesticides during those times may have resulted in lower potential for pesticide drift and the observed associations in this study may be lower than during other times of the year when pesticides are used more heavily.

Conclusions

This is the first study to estimate the extent of pesticide drift from agricultural greenhouses onto nearby homes, and the first to characterize this association using a physiological marker of exposure. Our findings indicate that the amount of pesticide drift from floricultural greenhouses is enough to lower the AChE activity of children living nearby (especially within 275 m). The present analyses involve data from 3 examination periods over an 8-year follow-up from childhood to adolescence and is one of the largest studies of children growing up in agricultural communities. The findings of this study can inform the planning of floricultural land use and residential zoning policy considerations. Added precautions to reduce the off-target drift of pesticides from greenhouse crops onto nearby homes are recommended.

Acknowledgments

The ESPINA study received funding from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (1R36OH009402) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES025792, R21ES026084). We thank ESPINA study staff in particular Julie Denenberg, Danilo Martinez, Janeth Barros, and Cecilia Cardenas, Fundación Cimas del Ecuador and its staff, the Parish Governments of Pedro Moncayo County, community members of Pedro Moncayo and the Education District of Pichincha-Cayambe-Pedro Moncayo counties and Cheyenne Rose for their contributions and support on this project.

Declaration of Interests / Funding: Funding for the ESPINA study: NIEHS (R01ES025792, R21ES026084), NIOSH (1R36OH009402).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bouchard MF, Bellinger DC, Wright RO, Weisskopf MG, 2010. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and urinary metabolites of organophosphate pesticides. Pediatrics 125, e1270–7. 10.1542/peds.2009-3058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard MF, Chevrier J, Harley KG, Kogut K, Vedar M, Calderon N, Trujillo C, Johnson C, Bradman A, Barr DB, Eskenazi B, 2011. Prenatal exposure to organophosphate pesticides and IQ in 7-year-old children. Environ. Health Perspect 119, 1189–95. 10.1289/ehp.1003185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradman A, Kogut K, Eisen EA, Jewell NP, Quirós-Alcalá L, Castorina R, Chevrier J, Holland NT, Barr DB, Kavanagh-Baird G, Eskenazi B, 2013. Variability of organophosphorous pesticide metabolite levels in spot and 24-hr urine samples collected from young children during 1 week. Environ. Health Perspect 121, 118–24. 10.1289/ehp.1104808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael SL, Yang W, Roberts E, Kegley SE, Padula AM, English PB, Lammer EJ, Shaw GM, 2014. Residential agricultural pesticide exposures and risk of selected congenital heart defects among offspring in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Environ. Res 135, 133–8. 10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronado GD, Holte S, Vigoren E, Griffith WC, Barr DB, Faustman E, Thompson B, 2011. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and residential proximity to nearby fields: evidence for the drift pathway. J. Occup. Environ. Med 53, 884–91. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318222f03a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curl CL, Fenske RA, Kissel JC, Shirai JH, Moate TF, Griffith W, Coronado G, Thompson B, 2002. Evaluation of take-home organophosphorus pesticide exposure among agricultural workers and their children. Environ. Health Perspect 110, A787–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenstein OS Von, Ling C, Cui X, Cockburn M, Park AS, Yu F, Wu J, Ritz B, 2019. Prenatal and infant exposure to ambient pesticides and autism spectrum disorder in children : population based case-control study 1–10. 10.1136/bmj.l962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Engel SM, Berkowitz GS, Barr DB, Teitelbaum SL, Siskind J, Meisel SJ, Wetmur JG, Wolff MS, 2007. Prenatal organophosphate metabolite and organochlorine levels and performance on the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale in a multiethnic pregnancy cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol 165, 1397–404. 10.1093/aje/kwm029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustman EM, Silbernagel SM, Fenske RA, Burbacher TM, Ponce RA, 2000. Mechanisms underlying Children’s susceptibility to environmental toxicants. Environ. Heal … 108 Suppl, 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman E, Hazlehurst MF, Loftus C, Karr C, McDonald KN, Suarez-Lopez JR, 2019. Residential proximity to greenhouse agriculture and neurobehavioral performance in Ecuadorian children. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 10.1016/j.ijheh.2019.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Harari R, Barr DB, Debes F, 2006. Pesticide exposure and stunting as independent predictors of neurobehavioral deficits in Ecuadorian school children. Pediatrics 117, e546–56. 10.1542/peds.2005-1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunier RB, Bradman A, Harley KG, Kogut K, Eskenazi B, 2016. Prenatal Residential Proximity to Agricultural Pesticide Use and IQ in 7-Year-Old Children. Environ. Health Perspect 10.1289/EHP504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handal AJ, Hund L, Páez M, Bear S, Greenberg C, Fenske RA, Barr DB, 2016. Characterization of Pesticide Exposure in a Sample of Pregnant Women in Ecuador. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol 70, 627–639. 10.1007/s00244-015-0217-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari R, 2004. Seguridad, salud y ambiente en la floricultura. IFA, PROMSA, Quito. [Google Scholar]

- Holland N, Furlong C, Bastaki M, Richter R, Bradman A, Huen K, Beckman K, Eskenazi B, 2006. Paraoxonase polymorphisms, haplotypes, and enyzme activity in Latino mothers and newborns. Environ. Health Perspect 10.1289/ehp.8540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch D, Lu C, Fisker-Andersen J, Jolley L, Fenske RA, 2002. Temporal association of children’s pesticide exposure and agricultural spraying: Report of a longitudinal biological monitoring study. Environ. Health Perspect 10.1289/ehp.02110829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz LJ, Kupina JM, Hirth NL, Henry RM, Noland GY, Barbee JY, Zhou JY, Weese CB, 2007. Intraindividual stability of human erythrocyte cholinesterase activity. Clin. Chem 53, 1358–63. 10.1373/clinchem.2006.085258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizardi PS, O’Rourke MK, Morris RJ, 2008. The effects of organophosphate pesticide exposure on Hispanic children’s cognitive and behavioral functioning. J. Pediatr. Psychol 33, 91–101. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenherz C, Fenske R. a, Simcox NJ, Bellamy G, Kalman D, 1997. Biological monitoring of organophosphorus pesticide exposure among children of agricultural workers in central Washington State. Environ. Health Perspect 105, 1344–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Fenske RA, Simcox NJ, Kalman D, 2000. Pesticide exposure of children in an agricultural community: evidence of household proximity to farmland and take home exposure pathways. Env. Res 84, 290–302. 10.1006/enrs.2000.4076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks AR, Harley K, Bradman A, Kogut K, Barr DB, Johnson C, Calderon N, Eskenazi B, 2010. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and attention in young Mexican-American children: the CHAMACOS study. Environ. Health Perspect 118, 1768–74. 10.1289/ehp.1002056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason HJ, 2000. The recovery of plasma cholinesterase and erythrocyte acetylcholinesterase activity in workers after over-exposure to dichlorvos. Occup. Med. (Lond) 50, 343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley LA, Lasarev MR, Higgins G, Rothlein J, Muniz J, Ebbert C, Phillips J, 2001. Work characteristics and pesticide exposures among migrant agricultural families: a community-based research approach. Environ. Health Perspect 109, 533–538. 10.1289/ehp.01109533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MD, Marty MA, Arcus A, Brown J, Morry D, Sandy M, 2002. Differences between children and adults: Implications for risk assessment at California EPA. Int. J. Toxicol 10.1080/10915810290096630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Rao P, Snively BM, Camann DE, Doran AM, Yau AY, Hoppin JA, Jackson DS, 2004. Agricultural and residential pesticides in wipe samples from farmworker family residences in North Carolina and Virginia. Environ. Health Perspect 112, 382–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raanan R, Harley KG, Balmes JR, Bradman A, Lipsett M, Eskenazi B, 2015. Early-life exposure to organophosphate pesticides and pediatric respiratory symptoms in the CHAMACOS cohort. Environ. Health Perspect 123, 179–85. 10.1289/ehp.1408235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaprasad J, Tsai MG-Y, Fenske RA, Faustman EM, Griffith WC, Felsot AS, Elgethun K, Weppner S, Yost MG, 2009. Children’s inhalation exposure to methamidophos from sprayed potato fields in Washington State: exploring the use of probabilistic modeling of meteorological data in exposure assessment. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol 19, 613–23. 10.1038/jes.2008.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauh V, Arunajadai S, Horton M, Perera F, Hoepner L, Barr DB, Whyatt R, 2015. Seven-year neurodevelopmental scores and prenatal exposure to chlorpyrifos, a common agricultural pesticide, in: Everyday Environmental Toxins: Childrens Exposure Risks. 10.1201/b18221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe C, Gunier R, Bradman A, Harley KG, Kogut K, Parra K, Eskenazi B, 2016. Residential proximity to organophosphate and carbamate pesticide use during pregnancy, poverty during childhood, and cognitive functioning in 10-year-old children. Environ. Res 150, 128–137. 10.1016/j.envres.2016.05.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsuddin N, Rampal KG, Ismail NH, Abdullah NZ, Nasreen HE, 2016. Pesticides Exposure and Cardiovascular Hemodynamic Parameters Among Male Workers Involved in Mosquito Control in East Coast of Malaysia. Am. J. Hypertens 29, 226–33. 10.1093/ajh/hpv093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JF, Geraghty EM, Tancredi DJ, Delwiche LD, Schmidt RJ, Ritz B, Hansen RL, Hertz-Picciotto I, 2014. Neurodevelopmental disorders and prenatal residential proximity to agricultural pesticides: the CHARGE study. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 1103–9. 10.1289/ehp.1307044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simcox NJ, Fenske RA, Wolz S. a, Lee IC, Kalman DA, 1995. Pesticides in household dust and soil: exposure pathways for children of agricultural families. Env. Heal. Perspect 103, 1126–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Lopez JR, Butcher CR, Gahagan S, Checkoway H, Alexander BH, Al-Delaimy WK, 2017. Acetylcholinesterase activity and time after a peak pesticide-use period among Ecuadorian children. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 10.1007/s00420-017-1265-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Lopez JR, Hong V, McDonald KN, Suarez-Torres J, López D, De La Cruz F, 2018. Home proximity to flower plantations and higher systolic blood pressure among children. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 221, 1077–1084. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Lopez JR, Jacobs DR, Himes JH, Alexander BH, Lazovich D, Gunnar M, 2012. Lower acetylcholinesterase activity among children living with flower plantation workers. Environ. Res 114, 53–9. 10.1016/j.envres.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Lopez Jose R., Jacobs DR Jr., Himes JH, Alexander BH, 2013. Acetylcholinesterase activity, cohabitation with floricultural workers, and blood pressure in Ecuadorian children. Environ. Health Perspect 121, 619–624. 10.1289/ehp.1205431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Lopez, Jose R, Jacobs DR Jr., Steffes M, Lee D-H, 2013. Presentation: Background persistent organic pollutants and altered glucose homeostasis over time: The CARDIA study, in: The Environmental Health Conference Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Ward MHH, Lubin J, Giglierano J, Colt JSS, Wolter C, Bekiroglu N, Camann D, Hartge P, Nuckols JRR, 2006. Proximity to crops and residential exposure to agricultural herbicides in iowa. Environ. Health Perspect 114, 893–7. 10.1289/ehp.8770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2008. Training Course on Child Growth Assessment 7, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006. World Health Organization Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr. 450, 76–85. [Google Scholar]