Abstract

Significant childhood adversity and chronic life stress are highly prevalent in patients with severe obesity. Such stress has been found to increase risk of adulthood obesity by up to 50% and it can also substantially degrade the effectiveness of evidence-based treatments for this chronic disease condition. Despite general appreciation of these facts, though, stress is not frequently measured in obesity research or routinely assessed during treatment for obesity or obesity-related complications. To address this important issue, we describe several validated tools that can be used for assessing life stress and discuss how information obtained from these instruments can be integrated into obesity treatment and research. Given the ease with which stress can be assessed, we argue that stress assessment and management should be widely included in clinical treatments for obesity, and that stress should be routinely measured in studies examining the long-term effects of obesity and obesity treatment.

Keywords: Obesity, Obesity Treatment, Psychosocial, Life Stress, Stress Management

Obesity, defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2, is a serious chronic health condition experienced by approximately 40% of the U.S. population. The prevalence of severe obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2), in turn, is around 5–10% in the U.S. (1). Understanding risk factors for obesity is thus of paramount concern.

Research and clinical observation both indicate that psychological stress is a highly prevalent but often underappreciated risk factor in obesity (2). In terms of its impact, one longitudinal population study that followed more than 9,300 individuals for 38 years found that stress exposure occurring before age 17 predicted up to a 33% increased risk of obesity at age 45 while controlling for relevant covariates (3). Second, the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study assessed the early adversity exposure of nearly 13,500 adults and found that having ≥4 ACEs was associated with a 60% increased risk of developing severe obesity in adulthood (4). A third population-based study of more than 37,000 Norwegian adults revealed that childhood stressors were associated with lifestyle-related conditions including obesity and diabetes mellitus in a dose-response manner, with greater childhood difficulties predicting worse outcomes (5). Finally, a recent study of nearly 1,000 patients seeking treatment for morbid obesity (BMI ≥35 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities or BMI ≥40 kg/m2) found that 46% of treatment-seekers experienced notable lifetime adversity, with a significantly higher prevalence among women (6). Moreover, this study found that lifetime adversity structured the shared patient-provider decision-making process surrounding treatment, such that patients experiencing substantial lifetime adversity were less likely to be referred for bariatric surgery than those without such stress (6).

The take-home message from this research is that life stress is a consistent predictor of increased risk for obesity and obesity-related complications, and even treatment decisions surrounding obesity. The important question that follows involves how we can best utilize this information to reduce health problems related to obesity and improve obesity treatment.

Life Stress and Obesity Treatment

It is well-established that sustainable weight loss reduces the cardiometabolic risk in persons with obesity. Given the complex biopsychosocial nature of obesity, however, treatment adherence can be challenging and strongly influenced by psychosocial factors like early life or chronic stress, which can degrade the effectiveness of evidence-based treatment for obesity. Conducting psychosocial assessments with patients seeking treatment may be essential for helping to maintain weight loss and improve quality of life following weight-loss treatment, including both behavioral lifestyle interventions and bariatric surgery. Despite the fact that comprehensive psychosocial evaluations are currently recommended as part of conducting multidisciplinary assessments of patients with morbid obesity, though, there is no consensus regarding what psychosocial factors should be assessed (7).

Stress can impact several factors that affect obesity risk, including eating habits, physical activity, and social and emotional processes. Consequently, listening to patients’ experiences and tailoring intervention programs to their unique biographical circumstances is recommended as best practice (7). Although life stress is frequently acknowledged as a contributing factor in a multimorbid disease such as obesity, surprisingly, stress is not routinely assessed in clinical settings. Additionally, there is no consensus regarding how best to integrate assessments of stress into the case conceptualizations or treatment plans of persons with morbid obesity.

One main reason to assess stress is that it can help inform obesity treatment. Current treatments for obesity include lifestyle modification, pharmacological treatment, and bariatric surgery. Bariatric surgery has superior effects on weight, morbidity, and mortality as compared with lifestyle modification alone or pharmacological treatment (8). However, bariatric surgery is also associated with potential complications (9). Preexisting, unresolved issues involving early life or chronic stress may worsen individuals’ chance of benefiting from obesity treatment. Therefore, bariatric surgery may not be the optimal treatment choice for all patients with morbid obesity. As a result, assessing life stress exposure in high-risk groups of patients with severe obesity might facilitate appropriate treatment selection. Assessing stress could also motivate patients to practice stress management strategies like mindfulness-based stress reduction, cognitive behavior therapy, and progressive muscle relaxation, which can help reduce stress and improve patients’ quality of life.

Assessing Stress in Obesity

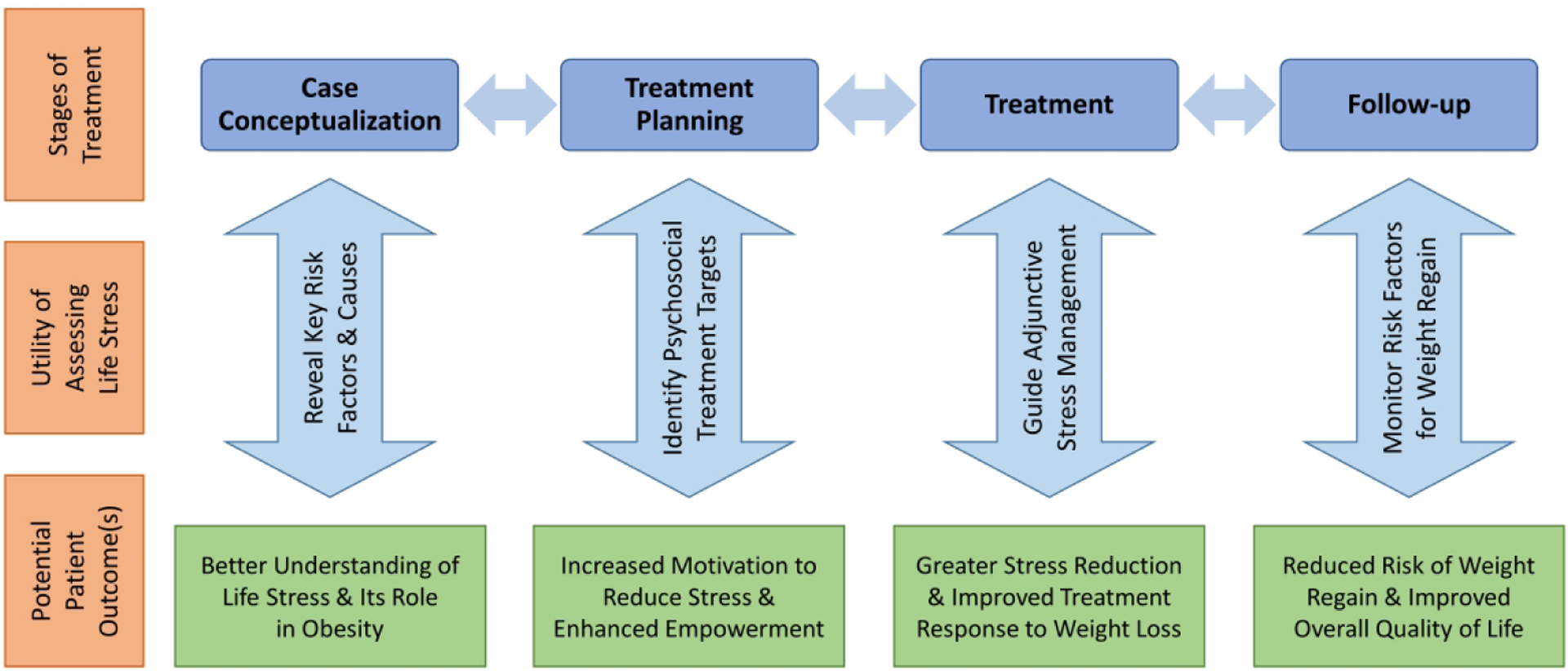

Several instruments exist for assessing stress in obesity research and clinical settings. These include the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), which is a widely used research instrument for measuring patients’ overall perceived stress levels; the ACEs questionnaire, which has been used in many clinical and population-based surveys (4); and the Stress and Advisory Inventory (STRAIN) (10), which is a brief, online stress interview that can be self- or interviewer-administered. Compared with the PSS and ACEs questionnaire, the STRAIN produces 115+ stress exposure summary scores and life charts that characterize individuals’ stress exposure not just over a limited timeframe but across the entire lifespan (see Table 1). Moreover, the STRAIN been found to predict many biological and clinical outcomes including obesity risk (10). Of these instruments, therefore, we believe the STRAIN is most well-suited for helping researchers and treatment providers better understand the role that stress and adversity play in obesity and obesity-related health problems (10). An illustration of how stress assessment and management can be integrated into obesity treatment is depicted in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Instruments for Assessing Life Stress

| Instrument | Assesses | Timeframe | Summary Scores | Upside | Downside |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSS | General stress perception | Past month | 1 score, indexing total recent perceived stress level |

|

|

| ACEs | Stressor exposure | Before age 18 | 1 score, indexing total early life stress exposure level |

|

|

| STRAIN | Stressor perception & exposure | Lifetime | 115 scores, indexing 17 different types of lifetime acute and chronic stress exposure |

|

|

Note: PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; ACEs = Adverse Childhood Experiences questionnaire; STRAIN = Stress and Adversity Inventory

Figure 1.

Assessing stress in obesity treatment. Stress assessment can be helpful at all stages of the treatment process, including case conceptualization, treatment planning, treatment, and follow-up. It can help reveal potential risk factors and causes of obesity and obesity comorbidities, identify modifiable psychosocial treatment targets, guide adjunctive stress management strategies, and help patients and treatment providers monitor risk factors for relapse and weight regain. Potential patient outcomes can include a better understanding of life stress and the role it plays in obesity, increased motivation to reduce stress and enhanced empowerment to make beneficial lifestyle changes, greater stress reduction and improved treatment response to weight loss interventions, and a reduced risk of weight regain and improved overall quality of life following treatment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, an abundance of evidence demonstrates that early life and chronic stress are clearly implicated but infrequently measured in obesity. The question of whether assessing and reducing stress levels may lead to sustainable weight loss in patients with obesity remains unknown. It is nevertheless likely that stress lowers an individual’s resilience to the embedded counter regulation to long-term weight loss that is suspected to be partly responsible for weight regain. Life stress and related negative cognitive or emotional processes might prevent patients with obesity from engaging in or maintaining behavioral changes that are known to have beneficial effects on health. Stress management is furthermore likely to influence the complex decision-making process regarding treatment, as well as the outcome of obesity treatment. We therefore suggest that stress assessment and management be included in prospective studies examining the long-term effects of obesity treatment and in clinical settings treating this chronic condition.

Funding:

GMS was supported by a Society in Science—Branco Weiss Fellowship, NARSAD Young Investigator Grant #23958 from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, and National Institutes of Health grant K08 MH103443 to George M. Slavich. These organizations had no role in writing this article or deciding to submit it for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosures: GMS developed the STRAIN, which is described in the paper.

References

- 1.Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, & Ogden CL Trends in obesity and severe obesity prevalence in US youth and adults by sex and age, 2007–2008 to 2015–2016. JAMA 2018;319:1723–1725. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Razzoli M, Pearson C, Crow S, & Bartolomucci A Stress, overeating, and obesity: Insights from human studies and preclinical models. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 2017;76:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas C, Hypponen E, & Power C Obesity and type 2 diabetes risk in midadult life: The role of childhood adversity. Pediatrics 2008;121:e1240–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, & Marks JS Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomasdottir MO, Sigurdsson JA, Petursson H, Kirkengen AL, Krokstad S, McEwen B, Hetlevik I, & Getz L Self reported childhood difficulties, adult multimorbidity and allostatic load. A cross-sectional analysis of the Norwegian HUNT study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ronningen R, Wammer ACP, Grabner NH, & Valderhaug TG Associations between lifetime adversity and obesity treatment in patients with morbid obesity. Obes. Facts 2019;12:1–13. doi: 10.1159/000494333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yumuk V, Tsigos C, Fried M, Schindler K, Busetto L, Micic D, Toplak H; Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the Study of Obesity. European guidelines for obesity management in adults. Obes. Facts 2015;8:402–424. doi: 10.1159/000442721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sjostrom L Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J.Intern.Med 2013;273:219–234. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakobsen GS, Smastuen MC, Sandbu R et al. Association of bariatric surgery vs medical obesity treatment with long-term medical complications and obesity-related comorbidities. JAMA 2018;319:291–301. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slavich GM and Shields GS Assessing lifetime stress exposure using the Stress and Adversity Inventory for Adults (Adult STRAIN): An overview and initial validation. Psychosom. Med 2018;80:17–27. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]