What is the innovation?

A watch-and-wait (WW) approach in rectal cancer patients after a clinical complete response (cCR) to neoadjuvant therapy (NAT) is the innovation1–3. cCR means no rectal tumor is found by digital exam, endoscopy, and MRI. The WW approach is non-standard, and gives the patient an opportunity to preserve the rectum and avoid surgery. WW has become more widespread as a cCR can occur in ~30% of patients treated with a total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT) approach4 (giving all therapy prior to rectal resection) and can occur in some patients receiving CRT alone, thereby leading to increased patient demand.

What are the key advantages over existing approaches?

Rectal cancer remains a complex disease to treat given multimodal care, including neoadjuvant chemoradiation (CRT), rectal resection (total mesorectal excision (TME)) and adjuvant chemotherapy. Some have opted to give all CRT and chemotherapy before surgery5 (e.g., TNT) addressing the micrometastatic niche immediately while improving chemotherapeutic regimen compliance. After neoadjuvant therapy, standard treatment is to proceed to TME, which places patients at risk for bowel, bladder, or sexual dysfunction as well as a stoma and other potential post-surgical complications (e.g., anastomotic leak). For patients with no clinical evidence of residual tumor, WW offers significant advantages including avoiding TME and maintaining excellent quality of life6. cCR is of course different than no pathologic evidence of tumor (pathologic complete response (pCR)), but clearly a pathological assessment can only be made after TME. The potential downside is that WW patients who do not have sustained complete tumor response are at risk for developing local regrowth2,3, and thus require delayed TME and face increased metastasis risk3 and oncologic outcome compromise.

How will this affect clinical care?

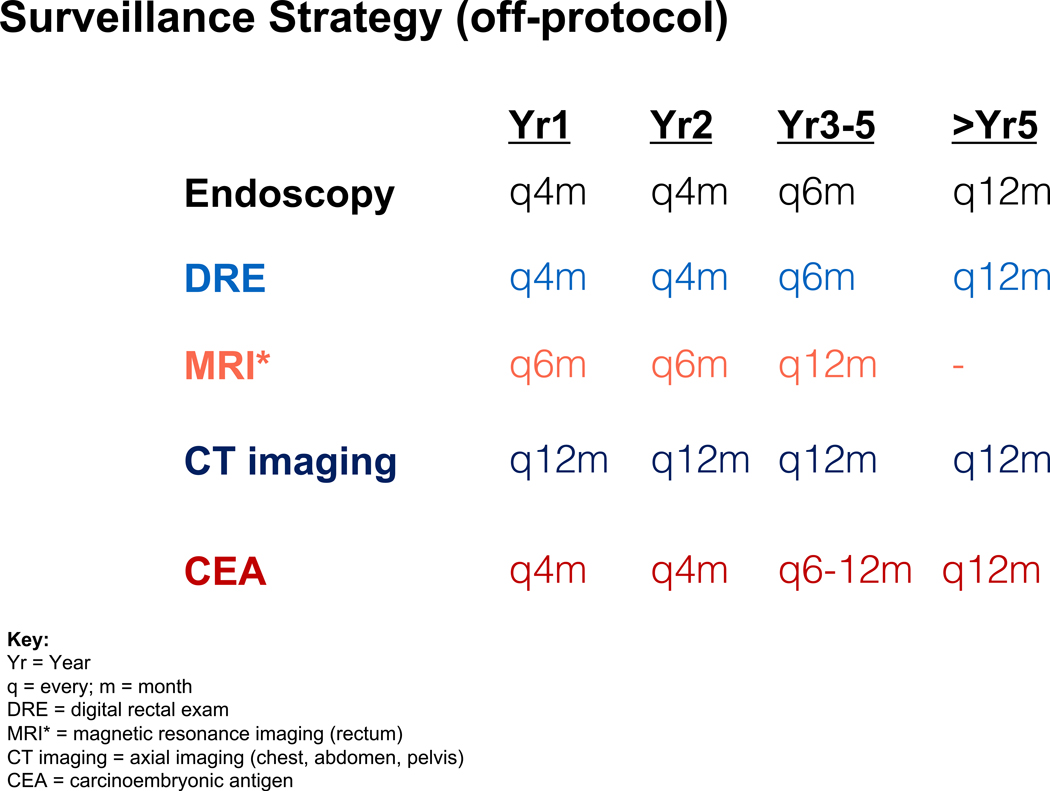

Patients electing WW must undergo strict surveillance for at least five years. Patients are observed for 8–12 weeks post-NAT to determine tumor response. For patients managed ‘off-protocol’ by WW at MSK, an agreement is made between the surgeon and the disease management team to proceed with this non-standard approach, accepting the inherent risks of local regrowth, possible need for salvage surgery, and potential local and/or distant failure3. The surveillance strategy used for those who achieve a cCR after NAT is shown in Figure 1. Patients who cannot handle uncertainty or return for follow-up visits will not be good WW candidates. TME is the best option for those who want to be absolutely certain there is no remaining cancer in the rectum.

Figure 1: Surveillance Strategy for Off-protocol WW patients.

Shown is a surveillance strategy utilized in patients followed after cCR off-protocol. The surveillance includes endoscopy, digital rectal exam and MRI-rectum for the follow-up of patients after they achieve a cCR. In addition, regular CEA checks and axial CT imaging is completed. Suggested intervals are shown. An alternative regimen used by some includes 3 monthly intervals in year 1, extending to 4 monthly intervals in year 2 after cCR is declared for endoscopy, digital exam and MRI-rectum and then extending the intervals to every 6 months for years 3–5.

Is there evidence supporting the benefits of the innovation?

Habr-Gama demonstrated that WW in selected patients, with a sustained cCR, compared to pCR patients who underwent TME that there were no differences in overall survival between the groups, that deferral of surgery was safe in the cCR group, and that local regrowths could be salvaged with R0 TME1. These original findings have been supported by work recently described in an international WW database analysis2. Nonetheless, WW is an alternative treatment strategy. The supporting data is based mainly on institutional case series with the exception of one prospective observational study7. Our work, evaluating 113 patients achieving a cCR after NAT, reflects the largest North American WW assessment and demonstrated four key points3. First, cCR patients accepted WW and were willing to take risk in order to preserve their rectum. Second, we observed a high rate of rectal preservation (79% at 5-years) in those achieving a cCR. Third, WW with careful surveillance and timely surgical salvage after local regrowth detection obtained local control in >90% of the salvage surgery patients and >98% overall. Fourth, distant metastases developed in 8% of WW patients. This metastatic progression rate is comparable to that reported for patients undergoing TME and found to have pCR (6%)8, is similar to WW patients in other series (8–9%)2, and is superior to rectal cancer patients in recent randomized trials (20–25%)9.

What are the barriers to implementing this innovation more broadly?

A main barrier to broad WW implementation is lack of expertise with the surveillance strategies including knowledge of the clinical appearance of cCR by endoscopy, and dedicated radiologists who can assess and reliably interpret MRI-rectum findings after NAT. Challenges to patient adherence include travel for surveillance exams, life interruption and anxiety related to surveillance. Another barrier in the community is lack of insurance coverage for interval endoscopy and MRI since there is not a solid WW endorsement by the NCCN. Other hurdles to broad implementation include non-uniform response definitions regarding cCR, surveillance protocol variations, multiple NAT regimens used, and short follow-up in the retrospective studies to date. It is unclear if a WW approach could be accomplished safely in all community-based settings as most studies to date have occurred in large, tertiary-care centers. Finally, refining patient selection and lowering local regrowth rates would improve acceptance and make this approach more generalizable.

In what time frame will this innovation likely be applied routinely?

The Organ Preservation in Rectal Adenocarcinoma (OPRA) phase II trial is evaluating 3-year disease-free survival in rectal cancer patients treated with CRT plus induction or consolidation chemotherapy and TME or WW10. In OPRA, MRI-staged clinical stage II or III rectal cancer patients amenable to TME are randomized to systemic chemotherapy in an induction approach (pre-CRT) or a consolidation approach (post-CRT). The decision for TME or WW is based on three-tiered tumor response assessment10. TME is required if residual tumor remains; if no tumor is detected, then WW is employed. OPRA will reveal whether implementation of WW using a TNT approach will affect overall oncologic outcome compared to standard treatment. OPRA will illuminate the best way to get patients to cCR; however, given that it is a phase II trial, the findings must be validated in an adequately powered phase III trial. Therefore, it will be 3–4 years before additional level I, prospective data will be available to validate this approach.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding: 5R01-CA182551-04; The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Career Development Award, the Joel J. Roslyn Faculty Research Award, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Limited Project Grant, the MSK Department of Surgery Junior Faculty Award, the Wasserman Colon and Rectal Cancer Fund, the Franklin Martin, MD, FACS Faculty Research Fellowship from the American College of Surgeons and the Colorectal Cancer Alliance and the Berezuk Colorectal Cancer Fund.

Role of Funders: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Smith has received travel support from Intuitive Surgical Inc., for fellow education. Dr. Smith has served as a clinical advisor for Guardant Health, Inc. Dr. Paty has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Garcia-Aguilar has received honoraria from Medtronic Inc., Johnson & Johnson Inc., and Intuitive Surgical Inc..

References:

- 1.Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Nadalin W, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2004;240(4):711–717; discussion 717–8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15383798. Accessed June 8, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Valk MJM, Hilling DE, Bastiaannet E, et al. Long-term outcomes of clinical complete responders after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer in the International Watch & Wait Database (IWWD): an international multicentre registry study. Lancet. 2018;391(10139):2537–2545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31078-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JJ, Strombom P, Chow OS, et al. Assessment of a Watch-and-Wait Strategy for Rectal Cancer in Patients With a Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Therapy. JAMA Oncol. January 2019:e185896. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cercek A, Roxburgh CSD, Strombom P, et al. Adoption of Total Neoadjuvant Therapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. JAMA Oncol. March 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fokas E, Allgäuer M, Polat B, et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Chemoradiotherapy Plus Induction or Consolidation Chemotherapy as Total Neoadjuvant Therapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: CAO/ARO/AIO-12. J Clin Oncol. May 2019:JCO.19.00308. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hupkens BJP, Martens MH, Stoot JH, et al. Quality of Life in Rectal Cancer Patients After Chemoradiation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(10):1032–1040. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appelt AL, Pløen J, Harling H, et al. High-dose chemoradiotherapy and watchful waiting for distal rectal cancer: a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):919–927. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00120-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park IJ, You YN, Agarwal A, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment response as an early response indicator for patients with rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1770–1776. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rödel C, Graeven U, Fietkau R, et al. Oxaliplatin added to fluorouracil-based preoperative chemoradiotherapy and postoperative chemotherapy of locally advanced rectal cancer (the German CAO/ARO/AIO-04 study): final results of the multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):979–989. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00159-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JJ, Chow OS, Gollub MJ, et al. Organ Preservation in Rectal Adenocarcinoma: a phase II randomized controlled trial evaluating 3-year disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with chemoradiation plus induction or consolidation chemotherapy, and total. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):767. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1632-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]