Abstract

The effect of local anesthetics, particularly those which are hydrophilic, such as tetrodotoxin, is impeded by tissue barriers that restrict access to individual nerve cells. Methods of enhancing penetration of tetrodotoxin into nerve include co-administration with chemical permeation enhancers, nanoencapsulation, and insonation with very low acoustic intensity ultrasound and microbubbles. In this study, we examined the effect of acoustic intensity on nerve block by tetrodotoxin, and compared it to the effect on nerve block by bupivacaine, a more hydrophobic local anesthetic. Anesthetics were applied in peripheral nerve blockade in adult Sprague-Dawley rats. Insonation with 1MHz ultrasound at acoustic intensity greater than 0.5W/cm2 improved nerve block effectiveness, increased nerve block reliability, and prolonged both sensory and motor nerve blockade mediated by the hydrophilic ultrapotent local anesthetic, tetrodotoxin. These effects were not enhanced by microbubbles. There was minimal or no tissue injury from ultrasound treatment. Insonation did not enhance nerve block from bupivacaine. Using an in vivo model system of local anesthetic delivery, we studied the effect of acoustic intensity on insonation-mediated drug delivery of local anesthetics to the peripheral nerve. We found that insonation alone (at intensities greater than 0.5W/cm2) enhanced nerve blockade mediated by the hydrophilic ultra-potent local anesthetic, tetrodotoxin.

Keywords: drug delivery, insonation, peripheral nerve, tetrodotoxin, acoustic intensity

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Administration of anesthetics locally to peripheral nerves (i.e. peripheral nerve blocks) can be an effective adjunct to perioperative pain management and can significantly reduce the use of systemic therapies, such as opioids [1]. The effect of local anesthetics on the function of axons is impeded by tissue barriers, which are ill-defined but can include the surrounding connective tissues, the various nerve sheaths (e.g. epineurium), and perineural cells connected by tight junctions that limit cellular permeability [2]. The effect of these barriers is much more marked on hydrophilic than amphiphilic local anesthetics [3], such as site-one sodium channel blockers (S1SCBs). S1SCBs, which include tetrodotoxin (TTX) and the saxitoxins, are ultrapotent hydrophilic local anesthetics [3–5] and are beginning to be introduced into clinical use [6,7]. The local anesthetic properties of S1SCBs are limited by their hydrophilicity, such that only a very small fraction of a perineurally injected dose penetrates to the surface of nerve cells in a peripheral nerve. Methods of enhancing penetration of TTX into nerve can greatly improve the frequency and duration of successful nerve block. Such methods have included co-administration with chemical permeation enhancers [8,9], or nanoencapsulation [10]. Here we have hypothesized that insonation may enhance the flux of local anesthetics, particularly hydrophilic ones, into the nerve and therefore improve the resulting nerve blockade. We further hypothesize that less hydrophilic local anesthetics would benefit less from insonation. This study could inform our understanding of the differential effects of insonation on local drug delivery to the peripheral nerve based on hydrophilic/hydrophobic balance.

Ultrasound is acoustic waves at frequencies above the range of human hearing. Both low (<100 kHz) and high (>1 MHz) frequency ultrasound, or the combination of both, can enhance drug delivery through biological barriers [11,12]. While low frequency is the most widely studied (particularly in the field of transdermal drug delivery), it may not be safe for all applications [13]. We have previously shown that high-frequency (1 MHz) ultrasound at very low acoustic intensity (0.0016 W/cm2), did not enhance TTX mediated nerve block unless the TTX is co-injected with lipid-based microbubbles [14]. However, it has been reported that higher intensities of 1MHz ultrasound alone can improve diffusion of molecules across skin in vitro [15]. Therefore, we investigated whether increasing acoustic intensity could affect diffusion to the peripheral nerve, using nerve block as a metric.

Here we explore whether at higher acoustic intensities insonation can enhance nerve blockade with TTX, and the role of microbubbles at higher ultrasound intensities. Using 1MHz frequency ultrasound, we examined the effect of increasing acoustic intensity with and without microbubbles on TTX mediated nerve blockade and systemic side effects, including local toxicity to the peripheral nerve and surrounding muscle.

Materials and Methods

Animal Care

Young adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (350–420 g) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and housed in groups of two per cage on a 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. light/dark cycle. All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed. Animals were cared for in compliance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Boston Children’s Hospital, as well as the Guide for the Care and use of Laboratory Animals of the US National Research Council.

Microbubble Preparation

Microbubbles were prepared as described previously [14]. DSPC, DSPE-PEG2k (90:10, molar ratio) were combined and then dissolved in chloroform. Chloroform was then removed by evaporation under vacuum for 2 hours. The lipids were dissolved in a 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) with glycerol: propylene glycol (80:10:10, volume ratio) to create a lipid concentration of 1 mM. The suspension was mixed well and sonicated with a bath sonicator (20 kHz for 3 minutes), followed by sonication by a probe sonicator (40kHz, 16 seconds). Fluorobutane gas was then slowly injected into a glass vial for 20 seconds, and the glass vial was immediately capped. Microbubble size and number-weighted size distribution were determined using a Coulter counter as described [14]. Prior to injection, microbubbles were diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a final concentration of 1×107 per mL.

The microbubbles used in this study were larger (6.54 μm +/− 3.35) than commercially available products (range 2– 4.9 μM) which are small because they are usually used as intravenous ultrasound contrast agents (e.g. Definity, Sonazoid, Optison, perfluorocarbon-exposed sonicated dextrose albumin microbubbles (PESDA). Larger commercially available microbubbles, such as PESDA microbubbles have better enhancement of in vitro and in vivo gene delivery at 1MHz compared to smaller microbubbles [16]. While the size of microbubbles used as ultrasound contrast agents are limited by capillary diameter (7–10 μm), this is not the case for local delivery to the sciatic nerve.

Insonation

Two clinical ultrasound devices were used, both at a resonant frequency of 1MHz in continuous mode. For acoustic intensities of 0.1W/cm2 or 0.5W/cm2 an Intelect Transport Ultrasound therapy unit model 2782 (Chattanooga Group Chattanooga, TN) with a 2.52 cm diameter transducer was used. For 3W/cm2, a Newage Pocket Sonovit Portable ultrasound with a 4.5 cm diameter transducer (New Age Medical Devices, Castel Maggiore, Italy) was used. The acoustic pressure profiles were calibrated using a needle hydrophone (HNC-200; Onda). Transverse scans at 0.7 cm away from the probe centers were acquired in degassed water to estimate the pressure fields of the treated areas.

For the Chattanooga transducers, the highest acoustic peak negative pressures measured in the field were 2.8 and 6.2 MPa, for Mode 0.1W/cm2 and 0.5W/cm2, respectively. The acoustic profile at the treated plane is shown in SI Figure 1A. The spatial average acoustic intensity was then calculated as 0.1 and 0.5 W/cm2 (for Mode 0.1W/cm2, and 0.5W/cm2). The Newage probe at the operated parameters produced a more focused field (SI Figure 1B) with a slightly higher pressure at the peak (6.8 MPa, peak negative pressure). The spatial average acoustic intensity was calculated as 0.6 W/cm2 (for Mode 3W/cm2). Ultrasound parameters used for experimentation are listed in Table I.

Table I:

Ultrasound parameters used for experimentation

| Ultrasound | Acoustic Intensity (W/cm2) | Mode | Probe Diameter (cm) | Measured Peak Negative Pressure (MPa) | Spatial Average Acoustic Intensity (W/cm2) | Figure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not applicable | 0 | 1,3 | ||||

| Intelect Transport Model 2782 | 0.1 | Continuous | 2.52 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 1,3 |

| Intelect Transport Model 2782 | 0.5 | Continuous | 2.52 | 6.2 | 0.5 | 1,3 |

| Newage Pocket Sonovit | 3 | Continuous | 4.5 | 6.8 | 0.6 | 1,2,3,4,5 |

Determining device self-heating and change in skin temperature following ultrasound treatment

To determine the potential for thermal effects secondary to ultrasound treatment, we sought to estimate ultrasound probe self-heating at 0.1, 0.5 and 3W/cm2. The temperature of the ultrasound probe was measured immediately prior to and immediately after 5 minutes of continuous use. We measured the temperature with an infrared visible thermometer (Grainger Infrared Visible Thermometer, Model No.: TG165-NIST, Lake Forest, IL).

To determine change in skin temperature at or near the sciatic nerve, rats were anesthetized using isoflurane in oxygen and shaved to provide an adequate coupling surface for ultrasound application. A flexible probe (Temperature K-Type Thermocouple Probe Model HI766F, Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI) of a thermocouple thermometer (K-Type Thermocouple Thermometer Model HI935005, Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI) was inserted 0.7 cm below the surface of the skin, positioned near the greater trochanter, at the level of the sciatic nerve. The probe diameter was 1.5 mm. We then applied the ultrasound probe, directly to the surface of the skin, and applied ultrasound: 1MHz at 0.1, 0.5, or 3W/cm2, for 5 minutes. Please note that the ultrasound probe used to deliver 0.1 and 0.5 W/cm2 was 2.52 cm in diameter, and the ultrasound probe used to deliver 3W/cm2 was 4.5 cm in diameter. The temperature output at the level of the greater trochanter was measured prior to and immediately following continuous ultrasound application (at either 0.1, 0.5, or 3W/cm2) for 5 minutes. Six temperature measurements were obtained at each acoustic intensity.

Preparation of Test Solutions

TTX (C11H17N3O8) stock solutions were made by dissolving 1 mg (>98% purity, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) in 10 mL of 20 mM citrate solution (pH 4.5). TTX was diluted in 300 μL of PBS to a concentration of 30 µM. Stock solutions of bupivacaine hydrochloride (C18H28N2O) (Sigma Aldrich St. Louis, MO) were made in PBS to a concentration of 1.23, 3.08, or 15.4 mM. Stock solutions of sulforhodamine B, (C27H30N2O7S2) (Sigma Aldrich St. Louis, MO), were made in PBS to a concentration of 10 mg/mL.

Sciatic Nerve Blockade Technique

Rats were anesthetized using isoflurane in oxygen. The animal’s fur was removed from the entire left leg/hindquarter by shaving. The skin surface was not degassed prior to experimentation. The ultrasound transducer was held posteromedial to the greater trochanter of the femur pointing in an anteromedial direction for 5 minutes. Treatment duration varies throughout the literature and 5 minutes of continuous ultrasound was chosen based on previous studies [14,17]. Ultrasound gel was used for coupling.

Injections were performed at the left sciatic nerve as described [3,18]. A 23-gauge needle was introduced posteromedial to the greater trochanter of the femur pointed in an anteromedial direction, 0.3 mL of test solution (drug, saline, and/or microbubbles) was injected upon contacting bone, depositing the drug over the sciatic nerve.

Groups of rats (N= 8) were injected at the sciatic nerve with 30 μM TTX or PBS and then treated with ultrasound at 1 MHz for 5 minutes at differing acoustic intensities (0.1W/cm2, 0.5W/cm2, or 3W/cm2). The concentration and dose of TTX were selected so as to provide minimal nerve block (to maximize the potential to detect improvement) with minimal systemic toxicity. PBS was used as a control to assess the effect of insonation in the absence of drug. The intensity of ultrasound was limited to 3W/cm2 or less, the FDA limit to avoid thermal injury [19,20]. After treatment, rats underwent neurobehavioral testing (see Assessment of Sciatic Nerve Blockade) to determine the frequency of successful nerve block, the duration of sensory (thermal nociception; perception of pain) and motor (weight bearing) nerve block. Metrics of systemic toxicity were assessed.

Assessment of Sciatic Nerve Blockade

In all experiments, the person assessing sciatic nerve block duration was blinded to what treatment the rat had received. Neurobehavioral testing of nerve blockade was performed at a distal site in dermatomes innervated by the sciatic nerve (left foot), while the right leg (uninjected) served as an untreated control.

Assessment of sensory blockade (thermal nociception, perception of pain) was performed by a modified hotplate test, as described [3,18]. This is a well-accepted method of testing analgesic responses of a single extremity. In brief, hind paws were exposed in sequence (left then right) to a 56 °C hot plate (Model 39D Hot Plate Analgesia Meter, IITC Inc., Woodland Hills, CA). The time until paw withdrawal was measured with a stopwatch. This test was repeated three times and the average time in seconds was calculated. If the animal did not remove its paw from the hot plate within 12 seconds, it was removed by the experimenter to avoid injury to the animal or the development of hyperalgesia. Testing was conducted every 30 minutes until the nerve blockade resolved. Latencies longer than 7 seconds, the midpoint between baseline thermal latency 2 seconds and maximum latency 12 seconds, were considered to represent effective blocks. The duration of thermal sensory block was calculated as the time for thermal latency to return to a value of 7 seconds.

Motor nerve block was assessed by a weight-bearing test to determine the motor strength of the rat’s hindpaw, as described [3,21]. In brief, the rat was positioned with one hindpaw on a digital balance and was allowed to bear its weight. The maximum weight that the rat could bear without the ankle touching the balance was recorded. Motor block was considered achieved when the motor strength was less than half-maximal, as described [3,21].

Any animal that died following injection and treatment was not included in the calculation of the percentage of animals blocked, duration of sensory/motor block, or assessment of contralateral block but was included in the estimation of systemic toxicity and death.

Lateral Tail Vein Blood Draws

Animals were injected at the sciatic nerve with 50 μL of sulforhodamine B (10 mg/mL) then treated with or without insonation at 3W/cm2 for 5 minutes. At predetermined time points (15 min, 30 min, and 60 min) following injection, blood was sampled from the lateral tail vein using a heparinized 23 gauge butterfly catheter and syringe. Time frames of testing were determined by serial blood draws and measurement of sulforhodamine levels as described previously[22], resulting in levels being drawn every 15 minutes. Samples were kept on ice and were centrifuged at 4000 x g for 15 minutes. To extract the sulforhodamine B, the supernatant was collected, methanol was added in a 1:1 volumetric ratio, samples were left at 4°C overnight, and then centrifuged at 16000 x g for 15 minutes. The supernatant was collected and the concentration of sulforhodamine B dye was analyzed by fluorescence (excitation/emission: 560/580 nm) (Agilent Varian Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer, Santa Clara, CA). For each animal, all data points are presented and the area under the curve was calculated (using built-in analysis Graph Pad Prism Software, San Diego, CA).

Sciatic Nerve Homogenization

Animals were injected at the sciatic nerve with 50 μL of sulforhodamine B (10mg/mL) then treated with or without insonation at 3W/cm2 for 5 minutes. Animals were sacrificed 1 h after injection, and both the left and right sciatic nerves were harvested, cut to a length of 1 cm, and weighed. Sciatic nerves were sonicated for 2 minutes on ice in 500 μL 5% Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich St. Louis, MO). To extract the sulforhodamine B, 500 μL of methanol was then added and the samples were sonicated using a Vibra-Cell Processor and 20 kHz probe (CV334) (Sonics Newtown, CT) continuously for two minutes. Samples were then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 minutes (Microfuge 22R Centrifuge, Beckman Coulter, CA, USA). Supernatants were collected and analyzed by fluorescence spectrometry (excitation/emission: 560/580 nm) (Agilent, CA, USA). The fluorescence intensity per nerve segment was measured and expressed as the intensity per mass of nerve (a.u./μg).

Tissue Harvesting and Histology

Animals were euthanized with carbon dioxide, and the sciatic nerves and adjacent tissues were harvested for histology. Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin using standard techniques. Tissues were harvested 4 days or 14 days after injections. Muscle samples were scored for inflammation (0–4 points) and myotoxicity (0–6 points) as described [23].

Statistical Analysis

Neurobehavioral data, fluorescence intensity, and histology data are reported as medians with interquartile ranges (i.e. 25th to 75th percentile) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. This method was selected because the data are ordinal (inflammation scores, myotoxicity scores), or showed departures from a normal distribution, as judged by the Kolmogorov-Smirov goodness-of-fit statistic (neurobehavioral data). The effect of treatment on systemic effects and death were compared with the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test for comparing independent binary proportions. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 11 SE (StataCorp College Station, Texas) software.

Results:

Effect of acoustic intensity on nerve blockade from TTX

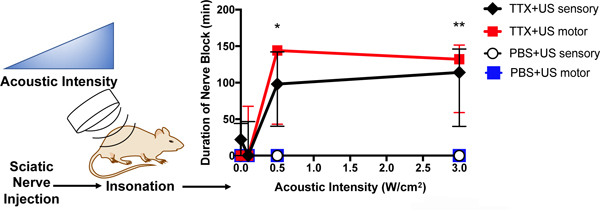

Rats injected with 30 μM TTX without insonation had a sensory nerve block success rate of 50% and a median duration of sensory nerve blockade of 25 [0–50] minutes (median [interquartile range]) (Figure 1 and SI Figure 2A). Insonation at 0.1W/cm2 did not statistically significantly improve the percentage of successful sensory blocks nor did it result in a prolongation of sensory nerve blockade (Figure 1 and SI Figure 2A). Insonation at 0.5W/cm2 and 3W/cm2 after injection of TTX resulted in a greater percentage of successful sensory nerve blocks compared to animals injected with TTX without insonation. For example, injection with TTX and insonation at 3W/cm2 resulted in 100% success rates for sensory nerve block, two-fold higher rate than animals without insonation (SI Figure 2A). Insonation with an intensity greater than 0.5W/cm2 also resulted in a statistically significant prolongation of sensory nerve block (Figure 1). Insonation at 3W/cm2 ultrasound resulted in a sensory nerve block of 116 [47–160] minutes, 4.6-fold longer than in animals treated with TTX without insonation (p = 0.0025 by Mann-Whitney U test).

Figure 1:

Effect of ultrasound (US) acoustic intensity on (A) duration of sensory and motor nerve blockade from 30 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Data are medians with interquartile ranges. (B) Effect of ultrasound (US) acoustic intensity on percentage of incidence of systemic side effects from 30 μM TTX. *p<0.05, **p<0.001 comparing to the group injected with TTX and without ultrasound treatment (acoustic intensity 0W/cm2).

No animal injected with PBS (no TTX) then insonated at any intensity exhibited sensory or motor nerve block (Figure 1).

There was less variability in the durations of sensory nerve blockade in animals insonated at 0.5 and 3W/cm2, as assessed by the ratio of the interquartile range to median nerve block (SI Figure 2B). This ratio is analogous to the coefficient of variation (standard deviation / mean): the larger the ratio, the more variability.

Effect of acoustic intensity on drug spread

In rats injected with local anesthetics, contralateral hindlimb deficits, respiratory distress, and/or death, suggest systemic distribution. Animals treated with TTX and insonated at either 0.5 or 3W/cm2 had a statistically significantly greater percentage of contralateral deficits than those animals injected with TTX without ultrasound (Figure 1B) (0.5W/cm2: p = 0.0011, 3W/cm2: p = 0.0011, by two tailed Fischer’s exact test). The incidence of respiratory distress or mortality was low in all groups, without statistically significant differences (Figure 1B).

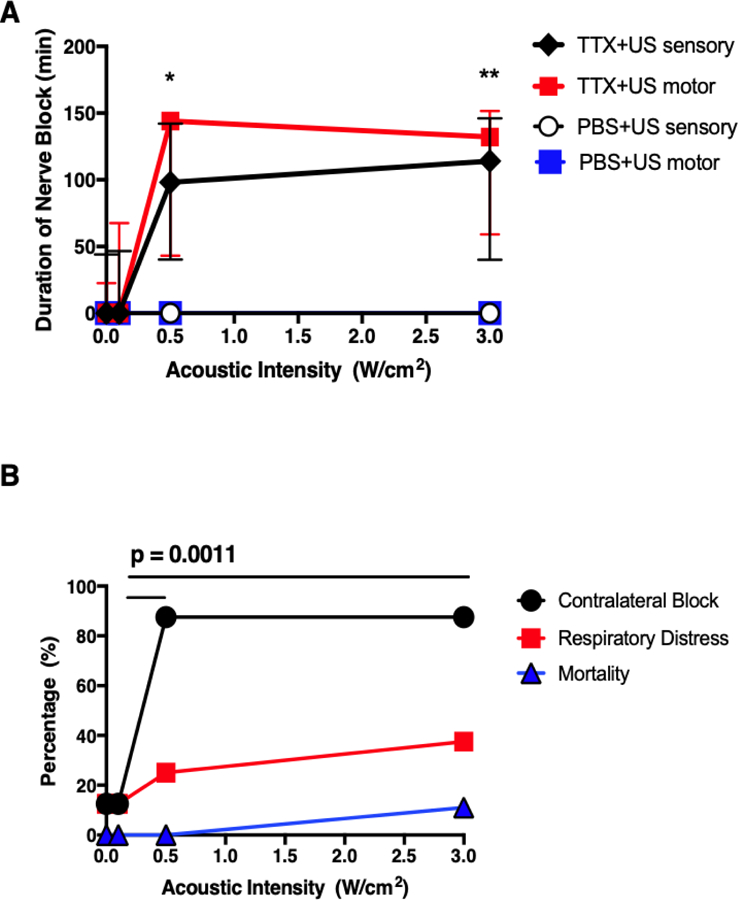

Ultrasonication can promote drug delivery by several mechanisms. One such mechanism is derived from the oscillatory motion of the insonated fluid and can occur in the absence of cavitation. The oscillating fluid increases the effective diffusivity of molecules; thus the transport of any drug, whether free or bound to a carrier within blood, cells, or extracellular fluids [24]. The increased incidence of contralateral block following insonation suggested that ultrasound was causing spread of TTX to the peripheral nerve, but also possibly to nearby blood vessels and other structures. To test this hypothesis, sulforhodamine B, a hydrophilic dye, was injected at the sciatic nerve and animals were treated with or without insonation at 3W/cm2 for 5 minutes (N = 6). Peripheral blood was obtained and the concentration of sulforhodamine B was assessed. The time course for fluorescence in blood was plotted and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. Insonation with 3W/cm2 resulted in a three-fold increase in fluorescence detected 30 minutes after injection compared to animals not treated with ultrasound (p = 0.0079 by Mann-Whitney U test) and 1.8-fold greater AUC compared to animals that were not insonated (Figure 2A, p = 0.034 by two tailed unpaired t test). One hour after injection, sciatic nerves were harvested, homogenized, and fluorescence was measured and expressed as fluorescence per nerve tissue mass (a.u./μg; Figure 2B). Insonation at 3W/cm2 resulted in significantly more fluorescence detected compared to animals without insonation (p = 0.0152 by Mann-Whitney U test).

Figure 2:

Effect of 3W/cm2 ultrasound (US) on distribution of fluorescence after injection of sulforhodamine B at the sciatic nerve. (A) Time course of fluorescence in peripheral blood at 15, 30, and 60 minutes after injection. Data are medians with interquartile ranges. **p<0.01 comparing US to No US at each time point. (B) Fluorescence in homogenized sciatic nerve 1 h after injection. Data are medians with interquartile ranges.

To determine the potential for thermal effects secondary to ultrasound treatment, we sought to estimate ultrasound probe self-heating and changes in skin temperature at or near the sciatic nerve after 5 minutes of continuous ultrasound treatment at 0.1, 0.5 and 3W/cm2. Ultrasound probe self-heating, as well as small increases in skin temperature were appreciated following treatment with each ultrasound device, with the 3W/cm2 probe resulting in the greatest increase in both self-heating (SI Figure 3A) and skin temperature increase (SI Figure 3B, SI Table I).

Effect of acoustic intensity and microbubbles on nerve blockade from TTX

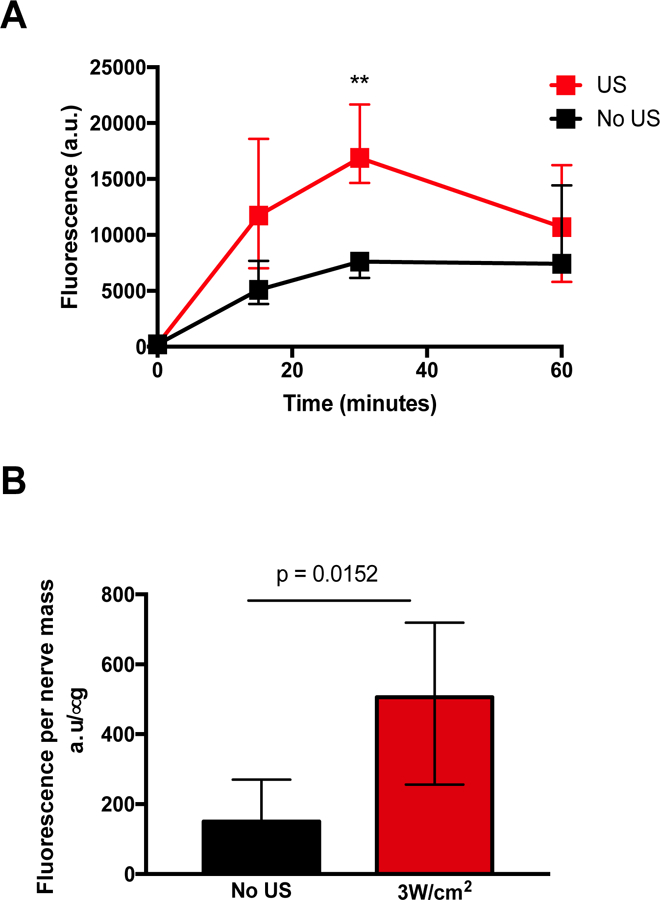

We have previously demonstrated that at very low acoustic intensity (0.0016W/cm2), microbubbles markedly improved TTX block frequency and duration of nerve blockade [14]. To study the effect of higher acoustic intensity on microbubble-enhanced nerve blockade, rats were injected at the sciatic nerve with 30 μM TTX with or without microbubbles then treated with or without insonation at 0.1W/cm2, 0.5W/cm2, or 3W/cm2 for five minutes (N = 8). Microbubbles were made by the thin-film method and had a mean size of 6.8 μm +/− 1.9 μm.

At 0.1W/cm2, co-injection with microbubbles significantly increased sensory (Figure 3A) and motor (Figure 3B) nerve blockade durations over those from TTX alone. At 0.5W/cm2 and 3W/cm2, the presence of microbubbles did not have a statistically significant effect on the durations of sensory or motor nerve block durations. Animals injected with TTX and microbubbles without insonation had a sensory nerve block duration of 0 [0–46] minutes, similar to durations observed in the TTX only group. Animals injected with microbubbles only did not develop nerve block (0 [0–0] minutes).

Figure 3:

Effect of ultrasound (US) acoustic intensity and microbubbles (MB) on duration of (A) sensory and (B) motor nerve block from 30 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX). Data are medians with interquartile ranges. *p <0.05, **p<0.001, comparing TTX+US+MB to TTX+US group at each acoustic intensity.

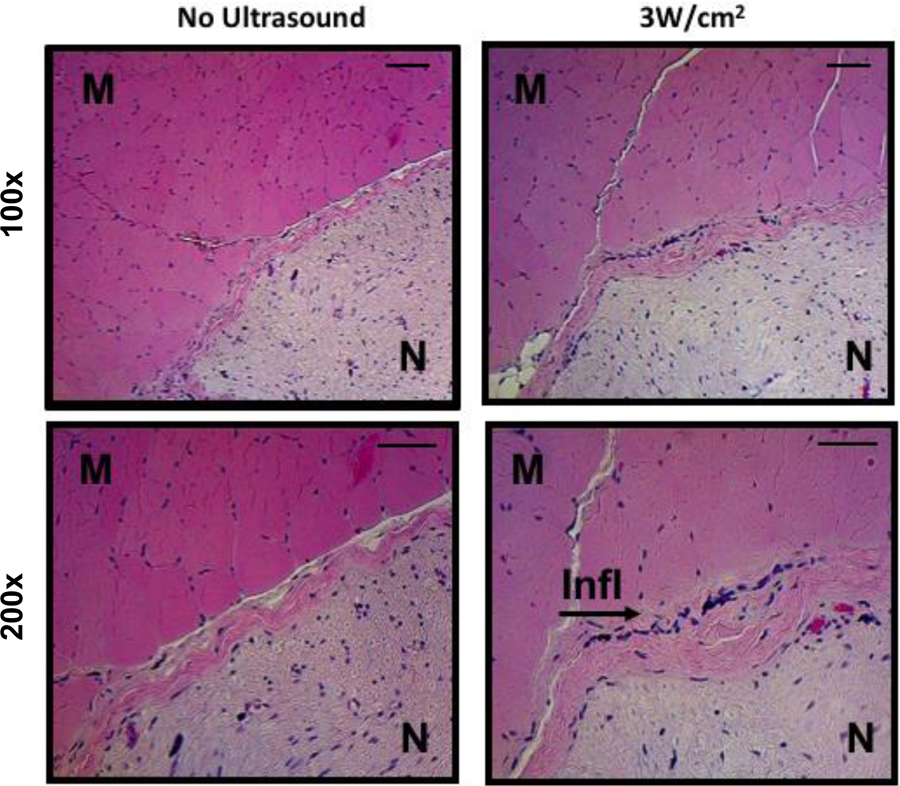

Tissue reaction to high-intensity high-frequency ultrasound

Rats (N = 6) injected with 30 μM TTX and treated with or without insonation at 3W/cm2 (the highest acoustic intensity) were examined for evidence of local tissue toxicity. Four or 14 days after injection, animals were euthanized and tissue reaction was assessed by examination of hematoxylin & eosin stained sections of the injection site (Figure 4). The two time points can reflect acute and chronic inflammation respectively. Inflammation and myotoxicity were scored as described [23] (Table II). Treatment with TTX with or without insonation at 3W/cm2 both resulted in no or minimal inflammation and myotoxicity on days 4 and 14. There was no statistically significant difference in inflammation or myotoxicity scores between animals with or without insonation at either time point (Table II).

Figure 4:

Representative (of four separate samples per group) photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin stained tissues at the site of injection 4 days after injection with 30 μM tetrodotoxin and treatment with and without 3W/cm2 ultrasound, shown at 100x and 200x magnification. M: muscle, N: nerve, Infl: inflammation. Scale bars are 50 μm.

Table II:

Perineural myotoxicity and inflammation scores a

| Days following injection | ||

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 14 | |

| Inflammation | ||

| TTX | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| TTX+US | 1 (1–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| p value | 0.48 | >0.99 |

| Myotoxicity | ||

| TTX | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| TTX+US | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| p value | 0.5 | >0.99 |

TTX: tetrodotoxin; 30 μM, US: ultrasound; 3W/cm2.

Data are medians with interquartile range. The range of scores is 0–4 for inflammation and 0–6 for myotoxicity. p values were determined by Mann-Whitney U test.

All animals (whether treated with TTX, microbubbles, or ultrasound) had complete resolution of both sensory and motor nerve blockade. In addition, we did not observe clinical evidence of nerve damage (e.g. abnormal ambulation) following treatment during the 14 day observation period following injection, suggesting permanent nerve damage was unlikely.

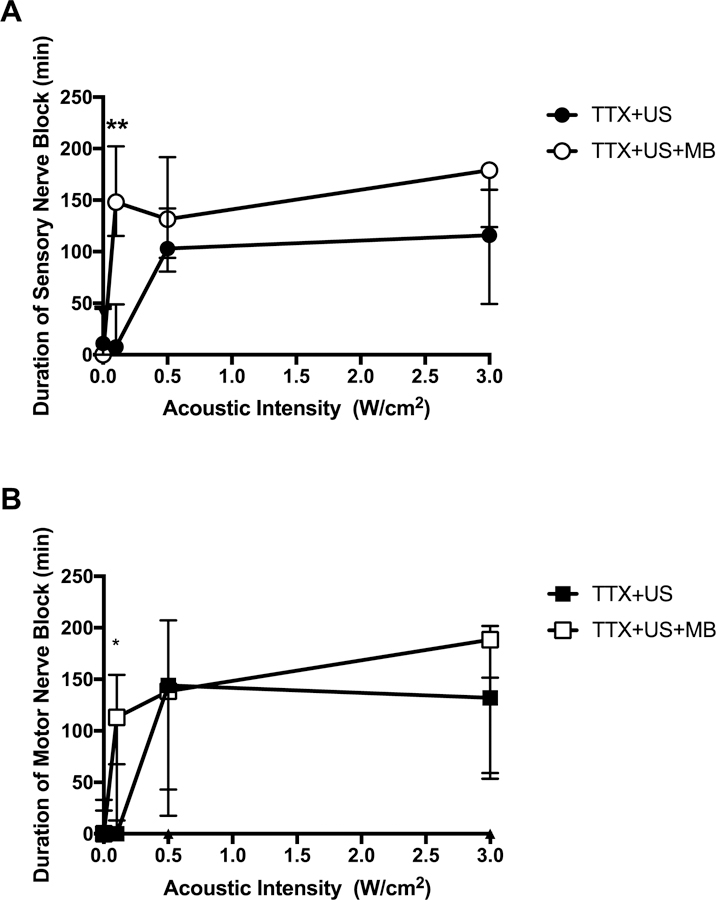

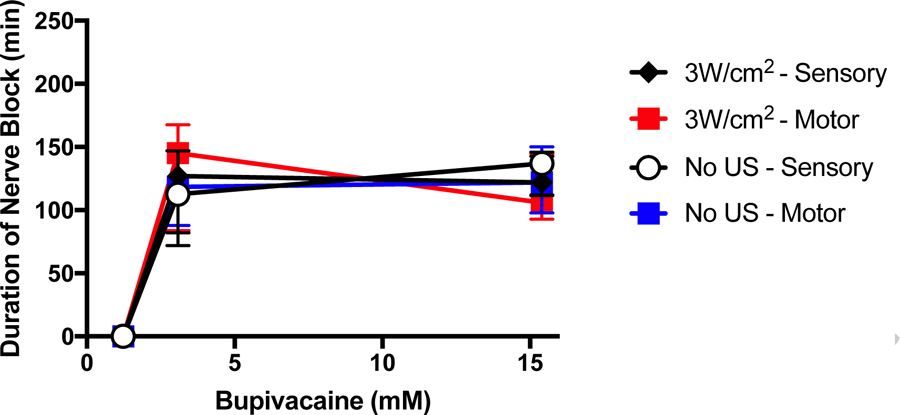

High-intensity high-frequency ultrasound does not enhance nerve block mediated by bupivacaine

We tested the hypothesis that a less hydrophilic local anesthetic would be less affected by insonation than would the very hydrophilic TTX. We tested bupivacaine; a potent amino-amide local anesthetic in common clinical use, an amphiphilic small molecule with a tertiary amine and an aromatic group. There is an equilibrium between the state where the tertiary amine is protonated (and the molecule is hydrophilic) and not (hydrophobic). In the latter from, bupivacaine can cross cell membranes (e.g. to reach its receptor site on the cytosolic side of a sodium channel) [25], and other biological barriers [26,[26]. Animals (N = 6) were injected at the sciatic nerve with 1.23, 3.08, or 15.4 mM bupivacaine, with or without insonation at 3W/cm2, the highest acoustic intensity used here. The concentrations of bupivacaine used correspond to 0.4, 0.1, and 0.5% w/v respectively (the units in which they are used clinically). Insonation did not extend sensory or motor nerve blockade (Figure 5).

Figure 5:

Effect of 3W/cm2 ultrasound (US) on duration of sensory and motor nerve block from bupivacaine. Data are medians with interquartile ranges.

Sensory vs. Motor nerve block

The relative preponderance of sensory and motor nerve block is a clinically important parameter. There were no statistically significant differences in the incidence or duration of sensory or motor nerve block in any group of animals.

Discussion:

Ultrasound-mediated drug delivery disrupts vascular and cell membranes and creates changes in local fluid flow patterns, which can propel substances across biological barriers [24,27] including through the sclera [28], the blood brain barrier [29,30], and transdermally [31,32]. Many groups have demonstrated the value of microbubbles [33–35] or stable cavitation agents [36] to enhance ultrasound mediated delivery of many drugs including chemotherapeutics [30,37,38]and therapeutic plasmids [39]. It is known that flux across barriers is proportional to the intensity of ultrasound delivered [15,24]. Here, we found that increasing acoustic intensity alone, was sufficient to enhance TTX mediated nerve block at the peripheral nerve. We observed that at higher acoustic intensities, microbubbles did not further enhance nerve block. The most likely explanation is that at a sufficient ultrasound intensity penetration of TTX to the axonal surface has been maximized with insonation alone, and so microbubbles would not be expected to have any effect. There are analogous situations, where chemical permeation enhancers (CPEs) and vasoconstrictors both enhance the duration of effect of TTX (also presumably by enhancing TTX to the axonal surface), but at high enough doses of each, the two together are not better than each individually [9].

In contrast, insonation did not enhance nerve block from the amino-amide local anesthetic bupivacaine. We hypothesize that this difference relates to the fact that TTX is very hydrophilic (Log P −6.21 [40]), while bupivacaine is in a pH-dependent equilibrium between the cationic protonated form (which is water soluble) and a neutral form (which is hydrophobic) (with a Log P of 3.4 [41]). These findings are congruent with previous findings that CPEs enhance nerve block from TTX but not bupivacaine [8,9]. Both with CPEs and sonication, we postulated that enhancement of TTX occurs because hydrophilic drugs have difficulty crossing biological barriers, whereas hydrophobic or amphiphilic drugs do not, and therefore are not enhanced by CPE or sonication. The current study suggests that the effect of sonication on local drug delivery to the peripheral nerve also depends on hydrophilic/hydrophobic balance.

In this study insonation increased the incidence of contralateral nerve deficits from TTX, suggesting systemic drug distribution. The view that insonation increased systemic distribution was supported by the fact that insonation increased the blood levels of sulforhodamine injected at the sciatic nerve. This finding is in contrast to the effects of CPEs, which were not associated with increased systemic toxicity at the concentrations of TTX and CPEs tested [8,9]. The increased systemic drug distribution with insonation may be attributable to the drug being physically spread, so that the surface area from which it is absorbed is increased. Alternatively, ultrasound may enhance flux of drug across blood vessel walls into the circulation, or increase uptake from tissue by increasing local blood flow [42]. It is likely that the systemic toxicity associated with TTX, with or without insonation, would be reduced in larger animals/humans, since the systemic toxicity of a given dose of a drug tends to be inversely related to the size of the animal, while the local effect of a given dose of anesthetic is not [3].

Applying 1MHz ultrasound (at acoustic intensities greater than 0.5W/cm2) was associated with pressures exceeding 6MPa, in which cavitation in the absence of microbubbles and tissue damage may occur [43]. We have shown previously that insonation using these parameters did not cause nerve damage [22]. However, the potential for tissue damage should be considered and closely monitored with longer insonation times or at higher pressures. Very high acoustic intensities (>35W/cm2) can cause severe tissue injury (e.g. complete axonal degeneration) and can have intrinsic effects on neuronal function (e.g. neuromodulation through neuronal suppression) [44–46]).

The use of imaging ultrasound to guide injection of local anesthetics for peripheral nerve blocks is commonplace. Clinical imaging is typically performed using ultrasound at acoustic intensities of 0.05 to 0.5W/cm2, similar to acoustic intensities tested in these experiments [47]. Therefore, it is possible that the ultrasound devices and parameters already used when performing peripheral nerve injections may enhance permeation of hydrophilic medications, with or without microbubbles.

This proof-of-principle study did not seek to determine the mechanism of how acoustic intensity enhances TTX mediated nerve block. In this model, it is possible that both thermal and nonthermal effects contribute to enhanced drug flux. We found evidence of device self-heating and small increases in tissue temperature following treatment with each device. It is conceivable that local tissue heating from insonation could increase regional blood flow [42,48,49]. We, therefore, cannot rule out the possibility of thermal effects. We note, however, that it is vasoconstriction, not vasodilation (the typical response to heating) that usually results in prolongation of nerve block with TTX. Local heating also could have increased lipid membrane permeability and therefore enhanced drug flux into nerve [50]. Non-thermal effects (cavitation, microstreaming, altered membrane permeability, pore formation or endocytosis) may also be contributing to increased drug flux and therefore enhanced nerve blockade [51,52].

Using an in vivo model system of local anesthetic delivery, we studied the effect of acoustic intensity on insonation-mediated drug delivery of local anesthetics to the peripheral nerve. We found that at ultrasound intensities (≥ 0.5W/cm2), insonation alone enhanced nerve blockade mediated by the hydrophilic ultra-potent local anesthetic, TTX.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health R35 GM131728 (to DSK).

Abbreviations

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- S1SCB

site-one sodium channel blocker

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- MHz

megahertz

- W/cm2

Watt/centimeter2

- CPE

chemical permeation enhancer

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Joshi G, Gandhi K, Shah N, Gadsden J, Corman SL. Peripheral nerve blocks in the management of postoperative pain: challenges and opportunities. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:524–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piña-Oviedo S, Ortiz-Hidalgo C. The normal and neoplastic perineurium: a review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15:147–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohane DS, Yieh J, Lu NT, Langer R, Strichartz GR, Berde CB. A re-examination of tetrodotoxin for prolonged duration local anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohane DS, Lu NT, Gökgöl-Kline AC, Shubina M, Kuang Y, Hall S, et al. The local anesthetic properties and toxicity of saxitonin homologues for rat sciatic nerve block in vivo. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000;25:52–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hille B The receptor for tetrodotoxin and saxitoxin. A structural hypothesis. Biophys. J. 1975;15:615–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Navarro AJ, Lagos N, Lagos M, Braghetto I, Csendes A, Hamilton J, et al. Neosaxitoxin as a local anesthetic: preliminary observations from a first human trial. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lobo K, Donado C, Cornelissen L, Kim J, Ortiz R, Peake RWA, et al. A Phase 1, Dose-escalation, Double-blind, Block-randomized, Controlled Trial of Safety and Efficacy of Neosaxitoxin Alone and in Combination with 0.2% Bupivacaine, with and without Epinephrine, for Cutaneous Anesthesia. Anesthes. The American Society of Anesthesiologists; 2015;123:873–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simons EJ, Bellas E, Lawlor MW, Kohane DS. Effect of chemical permeation enhancers on nerve blockade. Mol. Pharm. American Chemical Society; 2009;6:265–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santamaria CM, Zhan C, McAlvin JB, Zurakowski D, Kohane DS. Tetrodotoxin, Epinephrine, and Chemical Permeation Enhancer Combinations in Peripheral Nerve Blockade. Anesth. Analg. Anesthesia and analgesia; 2017;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Liu Q, Santamaria CM, Wei T, Zhao C, Ji T, Yang T, et al. Hollow Silica Nanoparticles Penetrate the Peripheral Nerve and Enhance the Nerve Blockade from Tetrodotoxin. Nano Lett. American Chemical Society; 2017;18:32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberli MA, Schoellhammer CM, Langer R, Blankschtein D. Ultrasound-enhanced transdermal delivery: recent advances and future challenges Ther Deliv. 6 ed. Future Science Ltd; London, UK; 2014;5:843–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang R, Wei T, Goldberg H, Wang W, Cullion K, Kohane DS. Getting Drugs Across Biological Barriers. Adv. Mater. Weinheim. 2017;29:1606596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmadi F, McLoughlin IV, Chauhan S, ter-Haar G. Bio-effects and safety of low-intensity, low-frequency ultrasonic exposure. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2012;108:119–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cullion K, Santamaria CM, Zhan C, Zurakowski D, Sun T, Pemberton GL, et al. High-frequency, low-intensity ultrasound and microbubbles enhance nerve blockade. J Control Release. 2018;276:150–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiwari SB, Pai RM, Udupa N. Influence of ultrasound on the percutaneous absorption of ketorolac tromethamine in vitro across rat skin. Drug Deliv. Taylor & Francis; 2004;11:47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qin S, Caskey CF, Ferrara KW. Ultrasound contrast microbubbles in imaging and therapy: physical principles and engineering. Phys Med Biol. IOP Publishing; 2009;54:R27–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin J, Kong C, Cho JS, Lee J, Koh CS, Yoon M-S, et al. Focused ultrasound-mediated noninvasive blood-brain barrier modulation: preclinical examination of efficacy and safety in various sonication parameters. Neurosurg Focus. American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 2018;44:E15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohane DS, Sankar WN, Shubina M, Hu D, Rifai N, Berde CB. Sciatic nerve blockade in infant, adolescent, and adult rats: a comparison of ropivacaine with bupivacaine. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1199–208–discussion10A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azagury A, Amar-Lewis E, Yudilevitch Y, Isaacson C, Laster B, Kost J. Ultrasound Effect on Cancerous versus Non-Cancerous Cells. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2016;42:1560–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guan L, Xu G. Damage effect of high-intensity focused ultrasound on breast cancer tissues and their vascularities. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thalhammer JG, Vladimirova M, Bershadsky B, Strichartz GR. Neurologic evaluation of the rat during sciatic nerve block with lidocaine. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:1013–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rwei AY, Paris JL, Wang B, Wang W, Axon CD, Vallet-Regí M, et al. Ultrasound-triggered local anaesthesia. Nat Biomed Eng. Nature Publishing Group; 2017;1:644–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padera R, Bellas E, Tse JY, Hao D, Kohane DS. Local myotoxicity from sustained release of bupivacaine from microparticles. Anesthesiology. The American Society of Anesthesiologists; 2008;108:921–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitt WG, Husseini GA, Staples BJ. Ultrasonic drug delivery--a general review. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. Taylor & Francis; 2004;1:37–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ragsdale DS, McPhee JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of state-dependent block of Na+ channels by local anesthetics. Science. 1994;265:1724–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang R, Saarinen R, Okonkwo OS, Hao Y, Mehta M, Kohane DS. Transtympanic Delivery of Local Anesthetics for Pain in Acute Otitis Media. Mol. Pharm. 2019;16:1555–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzu-Yin W, Wilson KE, Machtaler S, Willmann JK. Ultrasound and microbubble guided drug delivery: mechanistic understanding and clinical implications. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2013;14:743–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suen W-LL, Wong HS, Yu Y, Lau LCM, Lo AC-Y, Chau Y. Ultrasound-mediated transscleral delivery of macromolecules to the posterior segment of rabbit eye in vivo. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. The Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology; 2013;54:4358–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raymond SB, Treat LH, Dewey JD, McDannold NJ, Hynynen K, Bacskai BJ. Ultrasound enhanced delivery of molecular imaging and therapeutic agents in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Bush AI, editor. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ting C-Y, Fan C-H, Liu H-L, Huang C-Y, Hsieh H-Y, Yen T-C, et al. Concurrent blood-brain barrier opening and local drug delivery using drug-carrying microbubbles and focused ultrasound for brain glioma treatment. Biomaterials. 2012;33:704–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitragotri S, Edwards DA, Blankschtein D, Langer R. A mechanistic study of ultrasonically-enhanced transdermal drug delivery. J Pharm Sci. 1995;84:697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prausnitz MR, Langer R. Transdermal drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1261–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman CMH, Bettinger T. Gene therapy progress and prospects: ultrasound for gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2007;14:465–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panje CM, Wang DS, Willmann JK. Ultrasound and microbubble-mediated gene delivery in cancer: progress and perspectives. Invest Radiol. 2013;48:755–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoon CS, Park JH. Ultrasound-mediated gene delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. Taylor & Francis; 2010;7:321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas RG, Jonnalagadda US, Kwan JJ. Biomedical Applications for Gas-Stabilizing Solid Cavitation Agents. Langmuir. American Chemical Society; 2019;35:10106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treat LH, McDannold N, Zhang Y, Vykhodtseva N, Hynynen K. Improved anti-tumor effect of liposomal doxorubicin after targeted blood-brain barrier disruption by MRI-guided focused ultrasound in rat glioma. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2012;38:1716–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujii H, Matkar P, Liao C, Rudenko D, Lee PJ, Kuliszewski MA, et al. Optimization of Ultrasound-mediated Anti-angiogenic Cancer Gene Therapy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2013;2:e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen S, Ding J-H, Bekeredjian R, Yang B-Z, Shohet RV, Johnston SA, et al. Efficient gene delivery to pancreatic islets with ultrasonic microbubble destruction technology. PNAS. 2006;103:8469–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US EPA; Jan. 2019, Estimation Program Interface (EPI) SuiteTM for Microsoft® Windows, v4.11. United States Environmental Protection Agencym, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansch C, Leo A, Hoekman D. 1995. Exploring QSAR: Hydrophobic, electronic, steric constants. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morishita K, Karasuno H, Yokoi Y, Morozumi K, Ogihara H, Ito T. Effects of Therapeutic Ultrasound on Intramuscular Blood Circulation and Oxygen Dynamics. Journal of the Japanese Physical Therapy Association. 2014;17:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maxwell AD, Cain CA, Duryea AP, Yuan L, Gurm HS, Xu Z. Noninvasive thrombolysis using pulsed ultrasound cavitation therapy - histotripsy. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2009;35:1982–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foley JL, Little JW, Vaezy S. Effects of high-intensity focused ultrasound on nerve conduction. Muscle Nerve. Wiley Subscription Services, Inc., A Wiley Company; 2008;37:241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foley JL, Little JW, Starr FL, Frantz C, Vaezy S. Image-guided HIFU neurolysis of peripheral nerves to treat spasticity and pain. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2004;30:1199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foley JL, Little JW, Vaezy S. Image-Guided High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound for Conduction Block of Peripheral Nerves. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. Kluwer Academic Publishers-Plenum Publishers; 2006;35:109–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warden SJ. A new direction for ultrasound therapy in sports medicine. Sports Med. Springer International Publishing; 2003;33:95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noble JG, Lee V, Griffith-Noble F. Therapeutic ultrasound: the effects upon cutaneous blood flow in humans. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2007;33:279–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fabrizio PA, Schmidt JA, Clemente FR, Lankiewicz LA, Levine ZA. Acute effects of therapeutic ultrasound delivered at varying parameters on the blood flow velocity in a muscular distribution artery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. JOSPT, Inc. JOSPT, 1033 North Fairfax Street, Suite 304, Alexandria, VA 22134–1540; 1996;24:294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sundaram J, Mellein BR, Mitragotri S. An experimental and theoretical analysis of ultrasound-induced permeabilization of cell membranes. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3087–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou B, Leung BYK, Sun L. The Effects of Low-Intensity Ultrasound on Fat Reduction of Rat Model. Biomed Res Int. Hindawi; 2017;2017:4701481–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mehier-Humbert S, Bettinger T, Yan F, Guy RH. Plasma membrane poration induced by ultrasound exposure: implication for drug delivery. J Control Release. 2005;104:213–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.