Abstract

Background:

A polygenic hazard score (PHS)—the weighted sum of 54 SNP genotypes—was previously validated for association with clinically significant prostate cancer and for improved prostate cancer screening accuracy. Here, we assess the potential impact of PHS-informed screening.

Methods:

UK population incidence data (Cancer Research UK) and data from the Cluster Randomized Trial of PSA Testing for Prostate Cancer were combined to estimate age-specific clinically significant prostate cancer incidence (Gleason≥7, stage T3–T4, PSA ≥10, or nodal/distant metastases). Using hazard ratios estimated from the ProtecT prostate cancer trial, age-specific incidence rates were calculated for various PHS risk percentiles. Risk-equivalent age—when someone with a given PHS percentile has prostate cancer risk equivalent to an average 50-year-old man (50-years-standard risk)—was derived from PHS and incidence data. Positive predictive value (PPV) of PSA testing for clinically significant prostate cancer was calculated using PHS-adjusted age groups.

Results:

The expected age at diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer differs by 19 years between the 1st and 99th PHS percentiles: men with PHS in the 1st and 99th percentiles reach the 50-years-standard risk level at ages 60 and 41, respectively. PPV of PSA was higher for men with higher PHS-adjusted age.

Conclusions:

PHS provides individualized estimates of risk-equivalent age for clinically significant prostate cancer. Screening initiation could be adjusted by a man’s PHS.

Impact:

Personalized genetic risk assessments could inform prostate cancer screening decisions.

Keywords: prostate cancer, screening, polygenic hazard score, genetic risk

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second-most-common malignancy in men worldwide with nearly 1.3 million cases diagnosed globally in 20181. It was the third leading cause of European male cancer mortality in 2018, following mortality from lung and colorectal cancers2. Prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing can reduce mortality3, but universal screening may cause overdetection of cancers that would never become clinically apparent in a man’s life-time and overtreatment of indolent disease. Guidelines recommend that individual men participate in informed decision making about screening, taking into account factors such as their age, race/ethnicity, family history, and preferences4–6.

Assessment of a man’s genetic risk of developing prostate cancer has promise for guiding individualized screening decisions7,8. We previously developed and validated a polygenic hazard score (PHS)—a weighted sum of 54 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotypes—as significantly associated with age at diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer, defined as cases where any of the following applied: Gleason score ≥7, clinical stage T3–T4, PSA ≥10, or where there were nodal or distant metastases9. Risk stratification by the PHS also improved the screening performance of PSA testing; the positive predictive value of PSA testing for clinically significant prostate cancer increased as PHS increased9.

Here, we apply the prostate cancer PHS to population data to assess its potential impact on individualized screening. Specifically, we combine genetic risk, measured by PHS, and known population incidence rates to estimate a risk-equivalent age: e.g., the age at which a man with a given PHS will have the same risk of clinically significant prostate cancer as a typical man at age 50 years. Such genetic risk estimates can guide individualized decisions about whether—and at what age—a man might benefit from prostate cancer screening.

Methods

Polygenic hazard score (PHS)

Full methodologic details of the development and validation of the prostate cancer PHS have been described previously9. Briefly, the PHS was developed using PRACTICAL consortium clinical and genetic data from 31,747 men of European ancestry as a continuous survival analysis model10 and found to be associated with age at prostate cancer diagnosis9. Validation testing was performed in an independent, separate dataset consisting of 6,411 men from the United Kingdom (UK) ProtecT study11,12. PHS was calculated as the vector product of a patient’s genotype (Xi) for n selected SNPs and the corresponding parameter estimates (βi) from a Cox proportional hazards regression (equation 1):

| (1) |

The 54 SNPs included in the model, and their parameter estimates, have been published9 and are also shown in Supplemental eTable 1.

Population age-specific incidence

Age-specific prostate cancer incidence data were obtained for men aged 40–70 years from the United Kingdom, 2013–2015 (Cancer Research UK)13. Men may be less likely to be screened outside this age range3,14. The log of the prostate cancer incidence data were fit using linear regression to develop a continuous model of age-specific prostate cancer incidence in the UK (Iall).

The UK age-specific proportion of incidence classified as clinically significant prostate cancer was estimated using data from the Cluster Randomized Trial of PSA Testing for Prostate Cancer (CAP). The CAP trial evaluated the impact of a single, low-intensity PSA screening intervention on prostate cancer-specific mortality in the UK15. CAP was linked to the ProtecT study, which included men aged 50–69 at randomization15; ProtecT compared management options including surgery, radiotherapy, and active surveillance in patients with PSA-detected prostate cancer12. The clinical and demographic features of the CAP and ProtecT studies have been previously described12,15. Clinically significant prostate cancer was defined as cases often ineligible for active surveillance (consistent with the definition used in the PHS development). These are cases with Gleason score ≥7, clinical stage T3–T4, PSA ≥10, or with nodal/distant metastases9,16,17. Men in the intervention arm of the CAP trial who were diagnosed with any prostate cancer were divided into 5-year age intervals at prostate cancer detection (n=8,054)15. The proportion of clinically significant disease in each age interval was calculated as the number of clinically significant prostate cancer diagnoses, divided by the total number of prostate cancer diagnoses in the CAP cohort for whom PSA and clinical stage information were available (n=6,388)15. The total (all ages) proportion of clinically significant prostate cancer was similarly calculated from CAP data. The age-specific prostate cancer incidence curve, Iall, was multiplied, within each 5-year age range, by the corresponding age-specific proportion of CAP clinically significant prostate cancer diagnoses, to yield a continuous estimate of age-specific, clinically significant prostate cancer incidence (Iclinically significant). A similar calculation was done to estimate age-specific, more aggressive prostate cancer incidence (using a stricter definition of clinically significant disease that corresponds to clinical high risk or above by NCCN guidelines: clinical stage T3–T4, PSA>20, Gleason score ≥8, or with nodal/distant metastases9,16,17) as Imore-aggressive. Finally, clinically insignificant prostate cancer incidence (Iclinically insignificant) was estimated as the difference between Iall and Iclinically significant.

Impact of genetic risk on clinically significant prostate cancer incidence

Men in the ProtecT study with genotype data (n=6,411) were categorized by their PHS percentile ranges (0–2, 2–10, 10–30, 30–70, 70–90, 90–98, and 98–100) to correspond to percentiles of interest (1, 5, 20, 50, 80, 95, and 99, respectively). These percentiles refer to the distribution of PHS in the ProtecT dataset within controls aged <70. Incidence rates of clinically significant prostate cancer were calculated for each percentile range (Ipercentile) using Cox proportional hazards regression (parameter estimate, ß), following the methods published previously9. The reference for each hazard ratio (HR) was taken as the mean PHS among those men with approximately 50th percentile for genetic risk (i.e., 30th-70th percentile of PHS, called PHSmedian), and this median group was assumed to have an incidence of clinically significant disease matching the overall population (Iclinically significant, calculated above). Incidence rates for the other percentiles of interest (Ipercentile) were then calculated by determining the mean PHS among men in the corresponding percentile range (called PHSpercentile) and applying equation 2:

| (2) |

As described in the original validation of this PHS model for prostate cancer9, PHS calculated in the ProtecT dataset will be biased by the disproportionately large number of cases included, relative to incidence in the general population. Leveraging the cohort design of the ProtecT study11, we therefore applied a correction for this bias, using previously published methods18 and the R ‘survival’ package (R version 3.2.2)19,20. The corrected PHS values were used to update PHSpercentile and PHSmedian used in equation 2. Then, 95% confidence intervals for the HRs for each percentile were determined by bootstrapping 1,000 random samples from the ProtecT dataset, while maintaining the same number of cases and controls from the original dataset. The Ipercentile, predicted partial hazard (product of PHSpercentile and the estimated ß), and standard errors (to account for sample weights) were calculated for each bootstrap sample.

Percentile-specific incidence estimates (Ipercentile) were visualized as the corresponding cumulative incidence curves for clinically significant prostate cancer diagnosis for men aged 50–70 years. Analogous HRs and incidence curves were similarly calculated for the annualized incidence rates of clinically insignificant and more aggressive prostate cancer.

An individualized PHS to aid prostate cancer screening decisions in the clinic might be facilitated by a readily interpretable translation of PHS to terms familiar to men and their physicians. The PHS was therefore combined with UK clinically significant prostate cancer incidence data to give a risk-equivalent age: when a man with a given PHS percentile would have the same risk of clinically significant prostate cancer as, say, that of a typical man at 50 years old (50-years-standard risk). We defined ΔAge as the difference between age 50 and the age when prostate cancer risk matches that of a typical 50-year-old man. 95% confidence intervals for the age when a man reaches 50-year-standard risk and ΔAge were determined using the HRs calculated from the 1,000 bootstrapped samples from ProtecT, described above.

Finally, we considered the common clinical scenario of a man presenting to his primary care physician to discuss prostate cancer screening. To illustrate how PHS might influence this discussion, we identified the subset of men in the ProtecT validation dataset who were around the median age of 60 years (55–64), to represent a typical patient. From this subset, we created three groups: those whose prostate cancer risk-equivalent age remained within the selected range (ages 55–64), those whose risk-equivalent age was <55, and those whose risk-equivalent age was ≥65. We then calculated the positive predictive value (PPV) and standard error [SE] of the mean of PSA testing for development of clinically significant prostate cancer in these three PHS-adjusted (prostate cancer risk-equivalent age) groups using methods described previously9. This was done by taking 1,000 random samples (with replacement) of the subjects with elevated PSA (≥3.0 ng/mL) in the dataset, stratified to ensure each random sample matched the distribution of controls and cases reported for men with elevated PSA in ProtecT11,12. Stratification was also used to ensure the proportion of clinically significant cases matched the proportion reported in CAP for the age range of 55–6411, such that the PPV for the sample exactly matched the expected value for the linked ProtecT and CAP trials, but the distribution of genetic risk (PHS) was varied at random within each disease status group (control, clinically significant, clinically insignificant). A similar calculation for PPV of PSA testing for development of any prostate cancer was performed for the three PHS-adjusted age groups.

Results

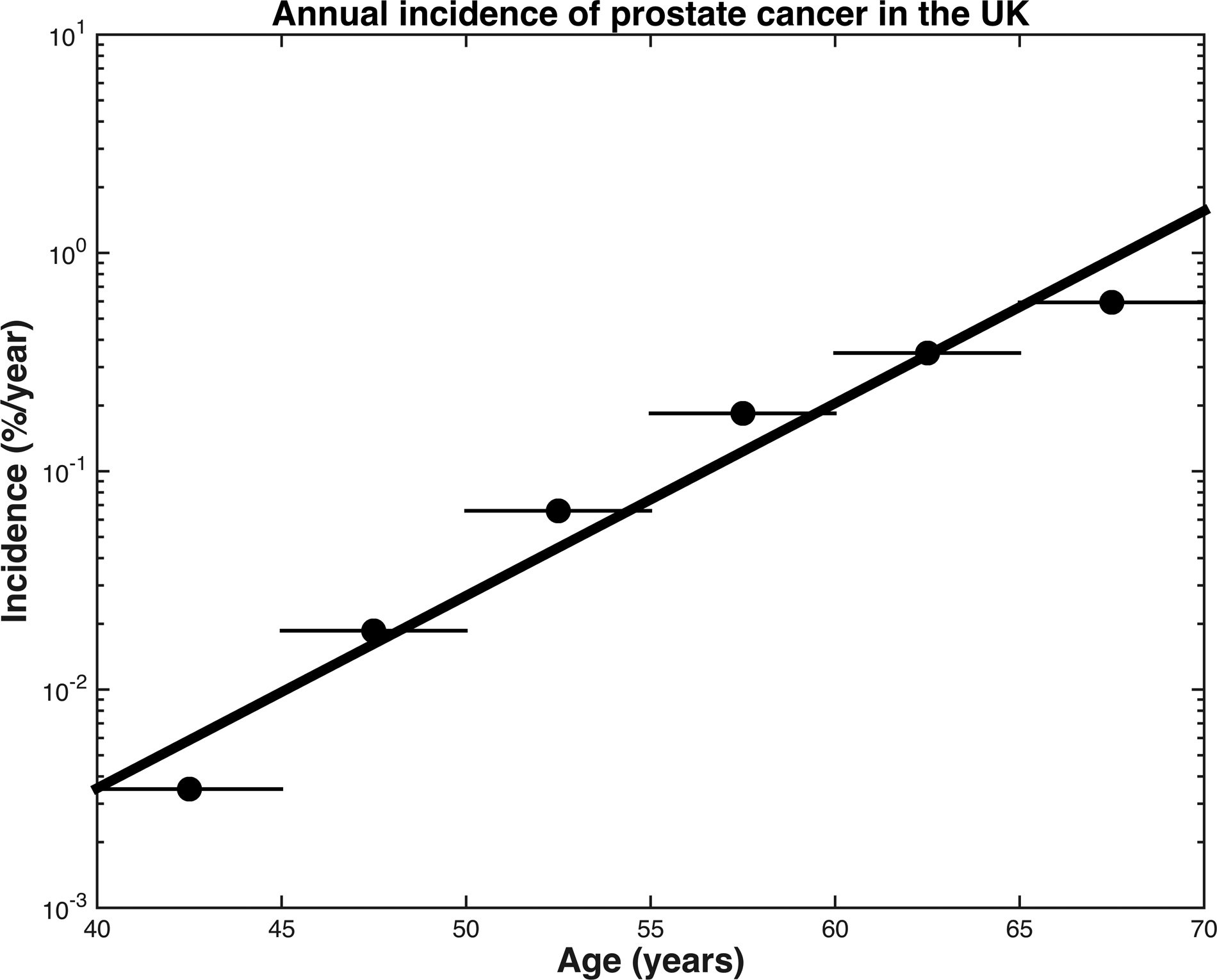

Linear regression yielded a model of prostate cancer age-specific incidence rates (equation 3, R2=0.96 and p=0.001) that was highly consistent with empirical data reported by Cancer Research UK (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual incidence of prostate cancer in the United Kingdom, 2013–2015. Dots represent the raw, age-specific incidence rates of each age range, per 100,000 males. The black line represents the results of linear regression for an exponential curve to give a continuous model of age-specific incidence in the United Kingdom, R2=0.96, p=0.001.

| (3) |

In the CAP study15, the overall proportion of prostate cancer incidence classified as clinically significant disease was 72.3%. The proportions of age-specific, clinically significant disease increased with age: 48.0%, 55.9%, 63.5%, and 79.7% of men aged 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, and 65–69, respectively, were diagnosed with clinically significant prostate cancer. Combining men aged 55–64, the proportion of age-specific, clinically significant prostate cancer was 61.1%.

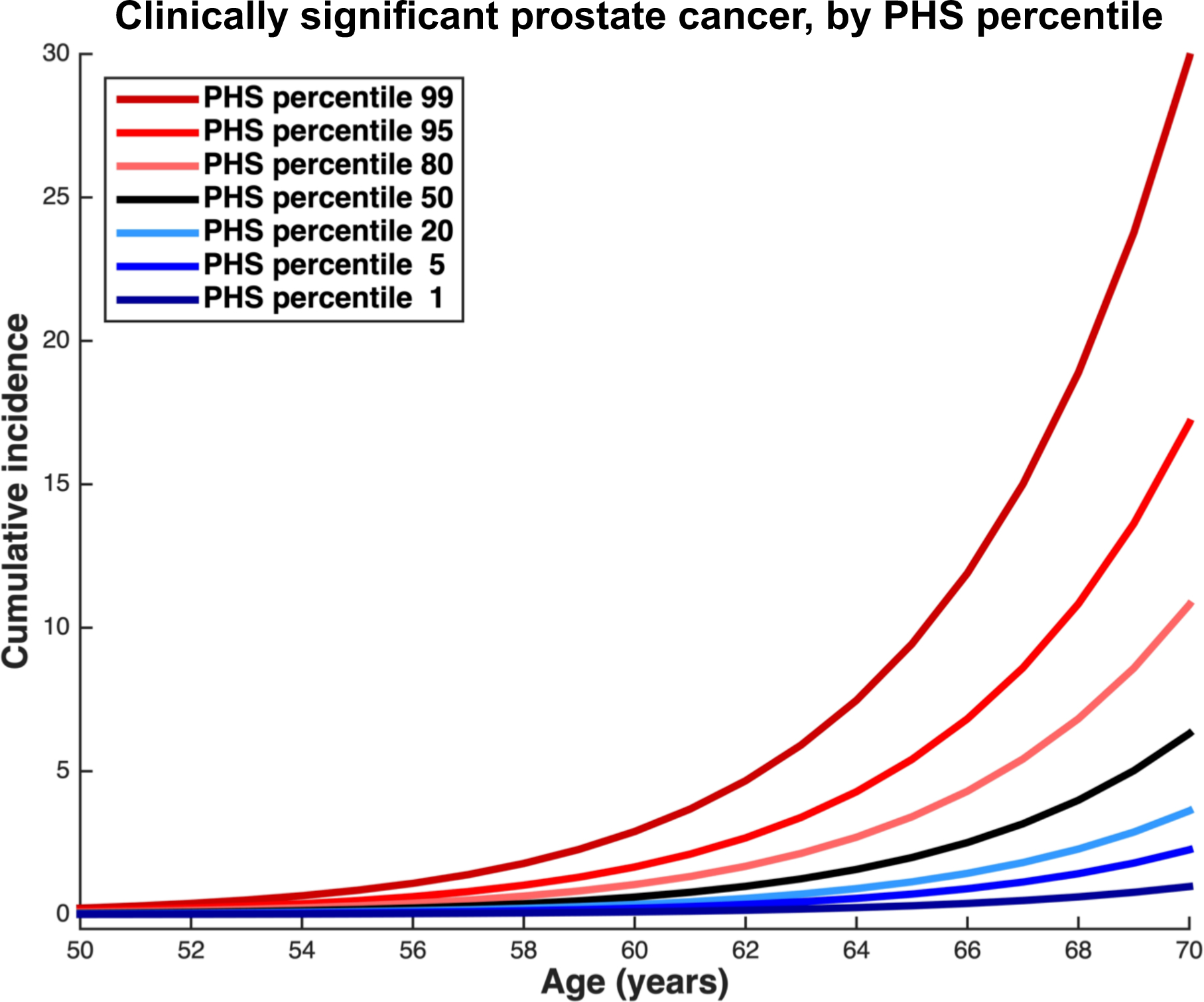

Cumulative incidence estimates of clinically significant prostate cancer are shown in Figure 2 for various levels of genetic risk, as indicated by PHS percentile, showing a difference in age at diagnosis related to PHS strata. Supplemental eFigures 1 and 2 show analogous results for the incidence curves of clinically insignificant and more aggressive prostate cancer, respectively. Table 1 shows risk-equivalent age for each PHS percentile. The expected age at clinically significant prostate cancer diagnosis differs by 19 years between the 1st and 99th PHS percentiles. Specifically, a man with a PHS in the 99th percentile reached a prostate cancer detection risk equivalent to the 50-years standard at an age of 41 years. Conversely, a man with a PHS in the 1st percentile would not reach the 50-years-standard risk level until age 60 years. Qualitatively, the curves for clinically significant (Figure 2), clinically insignificant (eFigure 1), and more aggressive (eFigure 2) prostate cancer maintain consistent horizontal shifts relative to curves for other PHS percentiles over the age range studied. Quantitatively, this was confirmed by ΔAge, which remained the same for each PHS percentile across a true age range of 40–70. Thus, ΔAge was taken to be approximately constant for each PHS percentile and is reported in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Incidence of clinically significant prostate cancer, as derived from application of polygenic hazard score (PHS) hazard ratios and population data from the United Kingdom. The overall population incidence is taken as the median risk (50th percentile); this accounts for age-specific proportions of prostate cancer that were clinically significant in the CAP trial15. Hazard ratios were calculated within ProtecT data for various levels of genetic risk ranges (0–2, 2–10, 10–30, 30–70, 70–90, 90–98, and 98–100) to correspond to percentiles of interest (1, 5, 20, 50, 80, 95, and 99, respectively), and used to adjust the median incidence curve. Blue lines represent genetic risk lower than the median while red lines represent genetic risk higher than the median.

Table 1.

Risk-equivalent age for clinically significant prostate cancer§, by polygenic hazard score (PHS) percentile.

| PHS percentile | Age when man reaches 50-year-standard riskα [95% CI] |

ΔAgeβ [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 [59, 62] | −10 [−11, −8] |

| 5 | 56 [54, 58] | −6 [−8, −4] |

| 20 | 53 [51, 55] | −3 [−5, −1] |

| 50 | 50 [48, 52] | 0 [−2, 2] |

| 80 | 47 [45, 48] | 3 [1, 4] |

| 95 | 44 [43, 46] | 6 [5, 8] |

| 99 | 41 [39, 43] | 9 [7, 11] |

Clinically significant prostate cancer was defined as Gleason score ≥7, clinical stage T3–T4, PSA ≥10, or with nodal/distant metastases.

Risk of typical 50-year-old defined as overall population incidence at age 50.

ΔAge = difference between 50 and the age when risk is that of a typical 50-year-old man.

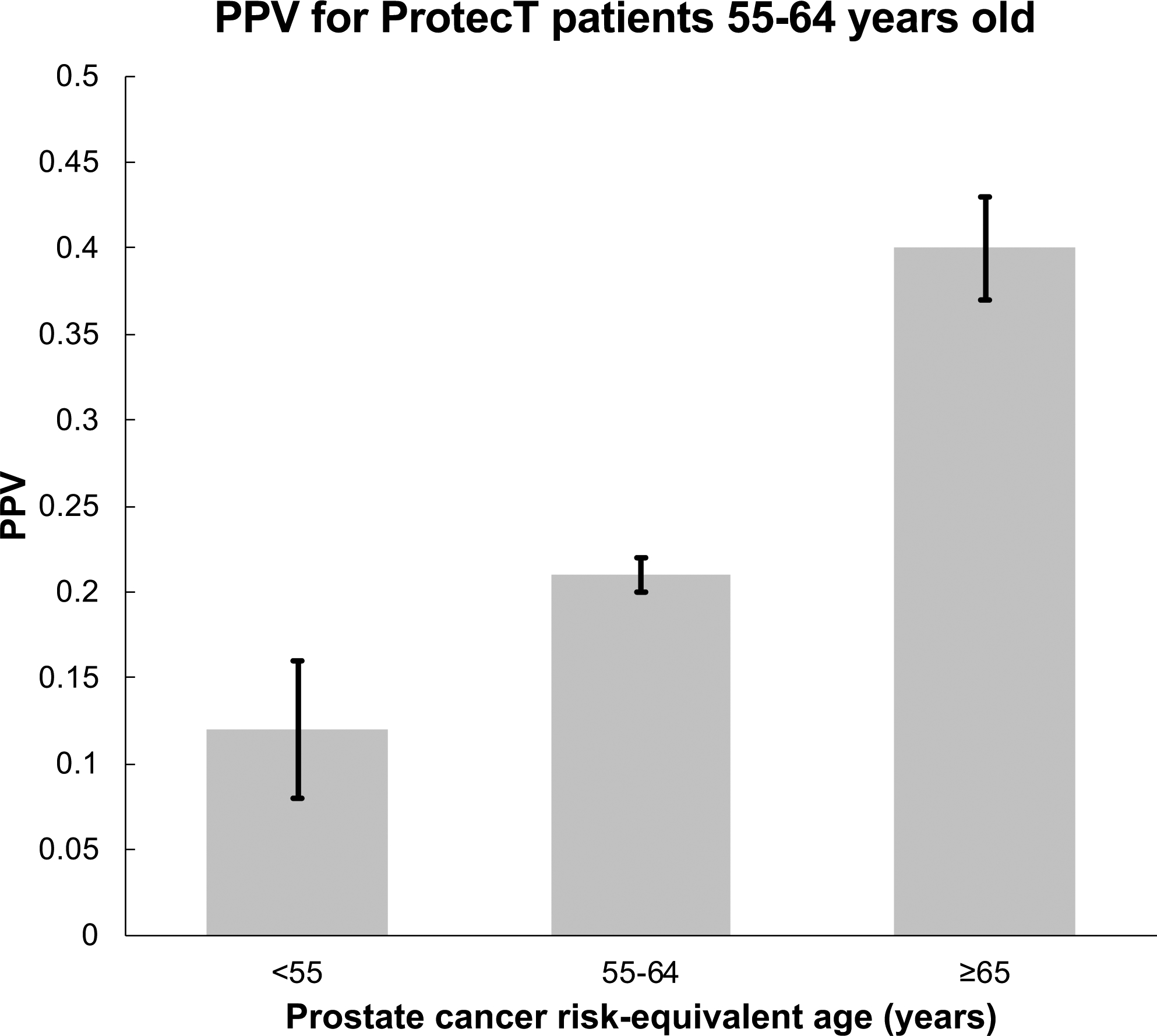

Figure 3 shows the PPV of PSA testing for clinically significant prostate cancer was 0.21 (SE: 0.01) for men approximately 60 years old (data derived from a total of 1,395 ProtecT men aged 55–64: 283 with clinically significant prostate cancer, 127 with clinically insignificant prostate cancer, and 575 controls with a PSA≥3.0 ng/mL). PPV was lower for those with a prostate cancer risk-equivalent age <55 years (0.12, SE: 0.04) and higher for those with prostate cancer risk-equivalent age ≥65 years (0.40, SE: 0.03).

Figure 3.

Application of prostate cancer risk-equivalent age to the clinical scenario of whether to screen a 60-year-old man (median age from ProtecT). The risk-equivalent age is the patient’s true age adjusted by PHS level. This plot shows results for all men from ProtecT aged approximately 60 years old (range: 55–64), grouped by their calculated prostate cancer risk-equivalent age: <55, 55–64, or ≥65. The positive predictive value (PPV) of PSA testing for clinically significant prostate cancer and the corresponding standard errors of the mean of PSA testing are shown for each of these 3 groups.

The PPVs of PSA testing for any prostate cancer were 0.18 (SE: 0.05), 0.37 (SE: 0.01), and 0.61 (SE: 0.03) in men with a prostate cancer risk-equivalent age <55 years, between 55–64 years, and ≥65 years, respectively. These PPVs, in combination with the PPVs of PSA for clinically significant prostate cancer, indicate that in the older prostate cancer-risk equivalent age group (≥65 years), 40% of positive PSA tests are from clinically significant disease, 21% are from clinically insignificant disease, and 39% are false positives. The false positive rates for men with a prostate cancer risk-equivalent age <55 years and between 55–64 years are 82% and 63%, respectively.

Discussion

We applied the PHS to population incidence data to estimate age-specific risk of clinically significant prostate cancer. The resulting age-specific incidence rates (displayed as incidence curves in Figure 2) demonstrate clinically meaningful differences across various levels of genetic risk, as estimated by PHS. By combining these population curves with an individual’s genetic risk and true age, we demonstrate calculation of a risk-equivalent age at diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer. This age relates a man’s current prostate cancer risk to that of the age-specific population average. The incidence curves for clinically significant prostate cancer are modulated by 19 years between the 1st and 99th percentiles of PHS. Moreover, the PPV of PSA testing in three PHS-adjusted (prostate cancer risk-equivalent age) groups demonstrated that PPV is significantly higher in men with higher risk-equivalent ages of prostate cancer diagnosis. These results have important implications for clinicians considering discussions of whether—and when—to initiate prostate cancer screening in an asymptomatic man.

Prostate cancer can cause considerable mortality and morbidity but is curable if detected early. Determination of age of clinically significant disease diagnosis is thus highly relevant. Data from the CAP study shown here confirm prior findings of increasing risk of clinically significant prostate cancer as men age21–24. The proportion of new prostate cancer diagnoses classified as clinically significant in CAP is higher than some older studies that were limited to men with low PSA and normal digital rectal exam25–27, while another modern population study shows similar or higher proportions with clinically significant disease21. Taken together, these results suggest that screening delayed to an older age will yield a higher incidence of clinically significant disease.

The primary screening tool, PSA testing, is associated with a small absolute decreased risk of death from prostate cancer3, but carries a risk of overdetection and harm from overtreatment in men who would never have experienced clinical manifestations of their prostate cancer28. Thus, universal screening comes at a high cost—both in burden on healthcare systems and in the sequelae arising from elevated PSA in men with indolent disease: unnecessary biopsy procedures, overdetection, and treatment-related morbidities4,5. Conversely, there are some men who will develop clinically significant prostate cancer and would benefit from screening, possibly even at a relatively young age. Screening guidelines recommend individualized decision-making, but the available quantitative or objective data to guide these decisions are insufficient. For instance, family history provides some guidance, but, genetic risk has been shown to be more strongly associated with age of clinically significant prostate cancer diagnosis than patient-provided family history9,29.

PHS, in conjunction with other informative factors such as family history, may help identify men who may develop the highest-risk cancers12. Incorporating a risk-adjusted age in an electronic medical record could reduce burden for general practitioners. The risk-adjusted age can be based on whatever threshold of risk for clinically significant prostate cancer is considered optimal. Here, we have used the typical risk at age 50. Waiting until the man whose risk-adjusted screening age reached 60 would be much more likely to avoid overdiagnosis and overtreatment than to miss an clinically significant prostate cancer. This is supported by the clinically significant-specific incidence rates reported here for CAP in the UK and also by recently reported absolute age-specific incidence rates in Norway21. One way a risk-stratified approach addresses overdetection is by providing a quantifiable, objective, and accurate rationale to not screen many men until they reach sufficient risk (in which time, their competing risks also have a chance to manifest; these could also inform screening and management decisions, especially if they affect life expectancy). The concern for overtreatment is also a critical consideration. As demonstrated in the ProtecT study, lower-risk disease does not need to be treated aggressively at diagnosis and can be monitored with active surveillance and routine PSA checks12. Additionally, other major trials have demonstrated that the risks of biopsy can be mitigated by using multiparametric prostate magnetic resonance imaging30–32. These important mitigating factors are not directly related to polygenic risk, but they do decrease the risks associated with a prostate cancer screening program.

The stratification of men based on their genetic risk is of particular interest in the primary care setting, where the majority of prostate cancer screening discussions take place. Shared decision-making between patient and physician has long been recommended in discussions of prostate cancer screening5,33, and physicians are tasked with determining an individual’s risk based on factors such as his family history and ethnicity. However, physicians demonstrate different attitudes towards screening, with some screening all men proactively to avoid underdiagnoses, some screening only those men who request it, and some who attempt to weigh the costs and benefits of PSA screening on a case-by-case basis34,35. General practitioners, who are already limited by time constraints and their patients’ other health issues, must carefully discuss the complex risks and benefits of PSA screening with their patients36. However, efficiently identifying men at higher risk of clinically significant disease is important because detection of prostate cancer at an early stage allows for definitive treatment to prevent cancer progression or metastases12.

Quantitative risk stratification could guide physicians in their screening conversations with patients by providing an objective risk-equivalent age for the development of clinically significant disease. This allows for simpler and more standardized informed decision-making regarding whether an individual man might benefit from prostate cancer screening. For example, physicians who normally initiate screening discussions at some age (e.g., 50–55) could shift the timing according to the prostate cancer risk-equivalent age. Some men might need to begin prostate cancer screening at a younger age to detect early-onset clinically significant disease. The PHS has previously demonstrated high PPV of PSA testing for clinically significant prostate cancer in men with progressively higher scores9.

The potential utility of prostate cancer risk-equivalent age in the clinic is additionally demonstrated by its impact on PPV of PSA testing for clinically significant prostate cancer. Suppose a 60-year old man presents to his physician to inquire about prostate cancer screening. If this man has a prostate cancer risk-equivalent age close to his true age (55–64), the PPV of a PSA test (for prediction of clinically significant prostate cancer) for him is approximately 24%. If his risk-equivalent age is <55, the PPV decreases to 13%, and he might be reassured in foregoing PSA testing. Postponing—or even forgoing—screening in men with low PHS percentiles to when they reach their risk-equivalent age could decrease the harms associated with screening, or early detection and treatment of prostate cancer4,5. Other men may choose to delay the initiation of PSA testing until they are older and have increased risk. Conversely, if this same man has a risk-equivalent age ≥65, the PPV of PSA testing increases substantially to 45%, implying that screening may be more informative for him. Of note, the increase in PPV in this illustration exceeds that of the reported effect of carrying a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA237.

Cost-effectiveness is another concern regarding prostate cancer screening. Use of PHS, a one-time test valid for a man’s entire life, can improve screening efficiency while reducing overall costs. The genotyping chip assay requires only a saliva sample and can be run for costs similar to those for single-gene testing (e.g. the BRCA mutation). Genotyping also informs genetic risks for other diseases, possibly allowing multiple tests to be run on the same genotype results38,39. PSA screening (and subsequent prostate biopsy) could be offered only to those men at higher risk of clinically significant disease. PHS might increase the efficiency of any prostate cancer screening program by incorporating knowledge that there are some men with higher baseline genetic risks of developing clinically significant prostate cancer, even at a younger age, while others have a low baseline genetic risk.

Limitations of this work include that the PHS did not incorporate genotypic data from men of non-European ancestry during its development9, a reflection of the available data, which may affect the potential use of the PHS for screening decision-making in men from other ethnic groups. This is noteworthy, as disparities in prostate cancer incidence and survival show that in the USA, men with African ancestry are more likely to develop prostate cancer and to die from their disease40. Our group and others are studying the application of genetic scores to non-European ancestry groups. Additionally, we used incidence data from a single country (the UK) with relatively low rates of screening. While the epidemiological data used in this work are of high quality and draw from the same UK population as was previously used for the validation of the PHS model9, further work should evaluate the PHS in other populations. Finally, there are now over 140 SNPs reported to have associations with prostate cancer, identified using a meta-analysis that included ProtecT data41, but not all of these SNPs are represented on the custom array used to develop the original PHS. Furthermore, the PHS model was validated using independent data from ProtecT; the inclusion of those other SNPs associated with prostate cancer would have introduced circularity into the validation. Adding more SNPs to further improve the model is an area of active investigation. If we, or others, succeed in developing a further optimized PHS, we expect the range of ΔAge to expand.

We conclude that clinically meaningful risk stratification can be achieved through application of a PHS that is associated with age at clinically significant prostate cancer diagnosis to UK population data. PHS can also be used to calculate estimates of risk-equivalent age for the development of clinically significant prostate cancer for individual men. The PPV of PSA was higher for men with higher PHS-adjusted prostate cancer-equivalent ages. Assessing personalized genetic risk via PHS could assist patients and physicians, alike, with the important decision of whether, and when, to initiate prostate cancer screening.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This study was funded in part by a grant from the United States National Institute of Health/National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (#K08EB026503) to T.M. Seibert, United States Department of Defense (#W81XWH-13-1-0391) to A.M. Dale and T.M. Seibert, the Research Council of Norway (#223273) to O.A. Andreassen, KG Jebsen Stiftelsen to O.A. Andreassen, and South East Norway Health Authority to O.A. Andreassen. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The CAP trial was funded by grants C11043/A4286, C18281/A8145, C18281/A11326, C18281/A15064, and C18281/A24432 from Cancer Research UK. The UK Department of Health, National Institute of Health Research provided partial funding. R.M. Martin is supported by a Cancer Research UK Programme Grant, the Integrative Cancer Epidemiology Programme (C18281/A19169), and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Bristol Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Funding for the PRACTICAL consortium member studies is detailed in the Supplemental Material.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no support from any organization for the submitted work except as follows:

A.M. Dale and T.M. Seibert report a research grant from the US Department of Defense. O.A. Andreassen reports research grants from KG Jebsen Stiftelsen, Research Council of Norway, and South East Norway Health Authority.

Authors declare no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years except as follows, with all of these relationships outside the present study:

T.M. Seibert reports honoraria from Multimodal Imaging Services Corporation for imaging segmentation, honoraria from WebMD, Inc. for educational content, as well as a past research grant from Varian Medical Systems. A.S. Kibel reports advisory board memberships for Sanofi-Aventis, Dendreon, and Profound. O.A. Andreassen reports speaker honoraria from Lundbeck.

Authors declare no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work except as follows:

O.A. Andreassen has a patent application # U.S. 20150356243 pending; A.M. Dale also applied for this patent application and assigned it to UC San Diego. A.M. Dale has additional disclosures outside the present work: founder, equity holder, and advisory board member for CorTechs Labs, Inc.; founder and equity holder in HealthLytix, Inc., advisory board member of Human Longevity, Inc.; recipient of nonfinancial research support from General Electric Healthcare. O.A. Andreassen is a consultant for HealthLytix, Inc.

Additional acknowledgments for the PRACTICAL consortium and contributing studies are described in the Supplemental Material.

Additional members from the Prostate Cancer Association Group to Investigate Cancer Associated Alterations in the Genome consortium (PRACTICAL, http://practical.icr.ac.uk/) are provided in the Supplemental Material.

A preliminary version of this work was presented in abstract form at the Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, February 14–16, 2019, San Francisco, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:356–387. doi: 10.1016/J.EJCA.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and Prostate-Cancer Mortality in a Randomized European Study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1320–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.eeh.2004.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1901–1913. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf AMD, Wender RC, Etzioni RB, et al. American Cancer Society Guideline for the Early Detection of Prostate Cancer: Update 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(2):70–98. doi: 10.3322/caac.20066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Health Service [NHS]. Prostate cancer - PSA testing. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/prostate-cancer/psa-testing/. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- 7.Witte JS. Personalized prostate cancer screening: Improving PSA tests with genomic information. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(62):62ps55. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pashayan N, Duffy SW, Chowdhury S, et al. Polygenic susceptibility to prostate and breast cancer: Implications for personalised screening. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(10):1656–1663. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seibert TM, Fan CC, Wang Y, et al. Polygenic hazard score to guide screening for aggressive prostate cancer: Development and validation in large scale cohorts. BMJ. 2018;360:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desikan RS, Fan CC, Wang Y, et al. Genetic assessment of age-associated Alzheimer disease risk: Development and validation of a polygenic hazard score. Brayne C, ed. PLoS Med. 2017;14(3):e1002258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane JA, Donovan JL, Davis M, et al. Active monitoring, radical prostatectomy, or radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer: Study design and diagnostic and baseline results of the ProtecT randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(10):1109–1118. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70361-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10-Year Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415–1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cancer Research UK. Prostate cancer incidence statistics. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/prostate-cancer/incidence. Accessed August 15, 2018.

- 14.Parker C, Gillessen S, Heidenreich A, Horwich A, ESMO Guidelines Committee. Cancer of the prostate: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:v69–v77. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin RM, Donovan JL, Turner EL, et al. Effect of a low-intensity PSA-based screening intervention on prostate cancer mortality: The CAP randomized clinical trial. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2018;319(9):883–895. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Prostate Cancer. Version 1 2019.

- 17.American College of Radiology. PI-RADS TM Prostate Imaging-Reporting and Data System 2015 Version 2. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/RADS/Pi-RADS/PIRADS-V2.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2018.

- 18.Therneau TM, Li H. Computing the Cox Model for Case Cohort Designs. Lifetime Data Anal. 1999;5(2):99–112. doi: 10.1023/A:1009691327335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. In: Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; ; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huynh-Le MP, Myklebust TÅ, Feng CH, et al. Age dependence of modern clinical risk groups for localized prostate cancer—A population-based study. Cancer. 2020;126(8):1691–1699. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muralidhar V, Ziehr DR, Mahal BA, et al. Association between older age and increasing gleason score. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13(6):525–530e3. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Draisma G, Postma R, Schröder FH, Van Der Kwast TH, De Koning HJ. Gleason score, age and screening: Modeling dedifferentiation in prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(10):2366–2371. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao YH, Demissie K, Shih W, et al. Contemporary risk profile of prostate cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(18):1280–1283. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. Long-term survival of participants in the prostate cancer prevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(7):603–610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The Influence of Finasteride on the Development of Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(3):215–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, et al. Effect of Selenium and Vitamin E on Risk of Prostate Cancer and Other Cancers. JAMA. 2009;301(1):39. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ilic D, Neuberger MM, Djulbegovic M, Dahm P. Screening for prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD004720. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004720.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen H, Liu X, Brendler CB, et al. Adding genetic risk score to family history identifies twice as many high-risk men for prostate cancer: Results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. Prostate. 2016;76(12):1120–1129. doi: 10.1002/pros.23200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasivisvanathan V, Rannikko AS, Borghi M, et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy for Prostate-Cancer Diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(19):1767–1777. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouvière O, Puech P, Renard-Penna R, et al. Use of prostate systematic and targeted biopsy on the basis of multiparametric MRI in biopsy-naive patients (MRI-FIRST): a prospective, multicentre, paired diagnostic study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):100–109. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30569-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed HU, El-Shater Bosaily A, Brown LC, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet. 2017;389(10071):815–822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32401-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Urological Association. Early Detection of Prostate Cancer. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-early-detection-(2013-reviewed-for-currency-2018). Accessed November 20, 2018.

- 34.Ilic D, Murphy K, Green S. What do general practitioners think and do about prostate cancer screening in Australia? Aus Fam Phys. 2013;42(12):904–908. www.prostate.org.au/articleLive/attachments/1/. Accessed November 19, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pickles K, Carter SM, Rychetnik L. Doctors’ approaches to PSA testing and overdiagnosis in primary healthcare: A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e006367. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunn AS, Shridharani KV, Lou W, Bernstein J, Horowitz CR. Physician-patient discussions of controversial cancer screening tests. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(2):130–134. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00288-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Page EC, Bancroft EK, Brook MN, et al. Interim Results from the IMPACT Study: Evidence for Prostate-specific Antigen Screening in BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. Eur Urol. 2019:1–12. doi: 10.1016/J.EURURO.2019.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michailidou K, Hall P, Gonzalez-Neira A, et al. Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):353–361. doi: 10.1038/ng.2563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torkamani A, Wineinger NE, Topol EJ. The personal and clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19(9):581–590. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0018-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: Progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):290–308. doi: 10.3322/caac.21340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schumacher FR, Al Olama AA, Berndt SI, et al. Association analyses of more than 140,000 men identify 63 new prostate cancer susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):928–936. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0142-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.