Abstract

One of the key parameters for a successful treatment with any drug is the use of an optimal dose regimen. Bisphosphonates (BPs) have been in clinical use for over five decades and during this period clinical pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) evaluations have been instrumental for the identification of optimal dose regimens in patients. Ideal clinical PK and PD studies help drug developers explain variability in responses and enable the identification of a dose regimen with an optimal effect. PK and PD studies of the unique and rather complex pharmacological properties of BPs also help determine to a significant extent ideal dosing for these drugs.

Clinical PK and PD evaluations of BPs preferably use study designs and assays that enable the assessment of both short- (days) and long-term (years) presence and effect of these drugs in patients. BPs are mainly used for metabolic bone diseases because they inhibit osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and the best way to quantify their effects in humans is therefore by measuring biochemical markers of bone resorption in serum and urine. In these very same samples BP concentrations can also be measured. Short-term serum and urine data after both intravenous (IV) and oral administration enable the assessment of oral bioavailability as well as the amount of BP delivered to the skeleton. Longer-term data provide information on the anti-resorptive effect as well as the elimination of the BP from the skeleton.

Using PK-PD models to mathematically link the anti-resorptive action of the BPs to the amount of BP at the skeleton provides a mechanism-based explanation of the pattern of bone resorption during treatment. These models have been used successfully during the clinical development of BPs. Newer versions of such models, which include systems pharmacology and disease progression models, are more comprehensive and include additional PD parameters such as BMD and fracture risk.

Clinical PK and PD studies of BPs have been useful for the identification of optimal dose regimens for metabolic bone diseases. These analyses will also continue to be important for newer research directions, such as BP use in the delivery of other drugs to the bone to better treat bone metastases and bone infections, as well as the potential benefit of BPs at non-skeletal targets for the prevention and treatments of soft tissue cancers, various fibroses, and other cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

Introduction

As described extensively in this historic Themed Issue, it has been 50 years since the first full publications on the pharmacological effects of bisphosphonates (BPs), which at that time were described in in vitro models as well as in rodents 1,2,3. These seminal findings were relatively quickly followed by the first human use of a BP, etidronate, in a child with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva4. Soon thereafter a large number of clinical studies followed with various BPs in eventually virtually all metabolic bone diseases, including Paget’s disease of bone, hypercalcemia of malignancy, osteoporosis and metastatic bone disease. BPs have significantly affected the lives of millions of people by improving their bone health and preventing fractures, and we should therefore be most grateful to those who made these crucial initial observations. However, 50 years of use has also taught us that we must be mindful of the dose regimens and safety profile of these drugs, and improvements in our PK/PD understanding offer the opportunity to improve our use of these drugs and to consider their use for the management of additional afflictions and disease states.

Herbert Fleisch and Graham Russell performed some of their seminal studies in Davos, Switzerland. Not far from Davos, in Egg in the Kanton Schwyz, also in Switzerland, another world-renowned physician Theophrastus von Hohenheim, aka Paracelsus, was born around 1493. As he told us five centuries ago: ‘Sola dosis facit venenum’, or ‘Solely the dose makes the poison’. One of the major determinants of efficacy but also toxicity of any drug is the dose. And for any drug the optimal dose regimen for a patient, i.e. the one with an optimal balance between efficacy and toxicity, depends on a number of factors such as the disease itself, patient-related factors such as body weight, renal function and genetics, and drug-related factors such as mechanism of action, potency and mode of administration. The purpose of early phases of clinical drug development is to identify the optimal dose regimens for drugs, while phase 3 trials and subsequent real-world data ultimately reveal how effective and safe these dose regimens really are. Several drug development studies are geared towards identifying factors that influence efficacy and toxicity, and if mechanism-based, these studies often try to describe the concentrations of the drug over time at the site of action, which likely explains efficacy and toxicity. However, these types of studies are difficult in patients. Usually only blood and urine samples are available, and blood and urine is usually not where a drug exert its actions. Another challenging part of drug development is the identification of markers that may inform us about the drug’s effects as well as toxicity in humans. This is especially difficult for new classes of drugs since many of these markers only become available after years of clinical use of the drugs. For BPs, while there are several unique aspects to their profile, these types of challenges are similar to other drugs a and the clinical development of BPs has been and continues to be a case of ever-evolving insight.

Clinical pharmacology studies, defined as studies in healthy volunteers and patients that involve measurements of drug and biomarkers, are an essential part of clinical drug development as they generate insight into the role of the presence of the drug in the treatment’s efficacy and safety. Clinical pharmacology studies, if designed and conducted correctly, help to identify the optimal dose regimen of a drug, both for populations as well as for individual patients. Compared to most other drugs, BPs have several unique properties that determine what a ‘correctly designed and conducted study’ really means. This review paper addresses some of these aspects and will hopefully provide insights important for the clinical pharmacological evaluation of new BPs. This knowledge might also be useful for the further evaluation of existing BPs, as well as help in developing newer applications, such as targeting other drugs to bone, and use in non-bone disorders such as cancers, various fibroses, and other cardiac and neurodegenerative diseases.

Pharmacokinetics

Short-term

The study of pharmacokinetics does not stand on its own. It should preferably explain effects of drugs, good and bad, observed over time. The pharmacokinetics should thus be relevant for a drug’s action. Chances for this are higher when the pharmacokinetics are able to describe concentrations or amount of drug at the site of action. For BPs, this would be at the bone surface where they are taken up into osteoclasts during osteoclast-mediated bone resorption. Also, note that higher turnover sites on the skeleton take up higher concentrations of BP, which complicates these approximations. One way of estimating the amount of BP delivered to the skeleton is by relating the dose to uptake. A 10 mg intravenous (IV) dose will deliver a higher amount of BP to the skeleton than a 1 mg dose. However, we also know that the fraction of a certain IV BP delivered to the skeleton can be highly variable, sometimes ranging between 10 and 90% of the dose, resulting from differences in, for examples, renal function and pretreatment rate of bone turnover 5. We know this by estimating the so-called Whole Body Retention (WBR) of the BPs, which is the dose of an IV BP minus the amount excreted into urine collected during a certain period after drug administration, usually 24 or 48h 6,7,8. This technique originates from the diagnostic use of BPs, or rather 99mTc-labeled BPs. Early studies with 99mTc-labeled BPs showed that the amount of BP excreted into urine can be used to calculate the amount retained in the body, and that most of that amount is indeed retained in the skeleton. The WBR can thus be used to determine the amount of BP at the skeleton, mainly because most BPs are not metabolized and are either excreted into urine or are retained predominantly in calcified tissue, i.e., the skeleton.

Short-term (24 or 48h) urine collections can also be used to determine the oral bioavailability (F) of a BP, provided a cross-over study design versus IV with ample time for wash-out is applied, and if body retention and renal handling are linear and dose-independent, which seems to be true for most BPs in the clinical dose range. Also for this kind of data analysis it is assumed that intra-patient variability in body retention is low. Several studies do show that WBR has a low intra-patient variability, in sharp contrast to oral bio-availability (F) 9–14.

Study design and the type and timing of samples collected determine how much information about PK that we can gather from each study. Serum and urine (short-term and long-term) data after oral and IV administration in the same patients is the ideal. The serum data enables assessment of maximum serum concentrations reached (Cmax, potentially relevant for toxicity), the time Cmax is reached (tmax), the area under the serum concentration time curve (AUC, also potentially relevant for toxicity) and with the latter the total clearance (Clt). The urine data subsequently enables the calculation of renal clearance (Clr) and nonrenal clearance (Clnr). Initial half-life (t½) can be determined from short-term serum concentrations, and terminal half-life estimated from long-term serum concentrations. With urine data after IV administration the amount of BP retained by the skeleton (WBR) can be calculated. Oral bioavailability (F), can be calculated from the short-term serum data after oral and IV dosing.

If only urine is collected after oral administration (no serum samples and no IV administration) it is hard to accurately estimate the bioavailability of the BP or to estimate how much of the oral drug is delivered to the skeleton. Historical data from earlier studies can be used, as was done for the study with oral alendronate in patients with Crohn’s diseases, but it significantly weakens the accuracy of the assessments15.

When only serum data are available after oral administration only the apparent oral clearance can be calculated and again, it is not really possible to determine the amount delivered to the skeleton. It is also not possible to determine the oral bio-availability, unless serum concentrations after IV administration have also been collected. Having only urine data available, but after both IV and oral administration would enable calculation of the WBR after IV administration, and also oral bioavailability and WBR after oral administration.

For some of these calculations it is assumed that the uptake of the BP into bone is dose- and mode of administration-independent. Having only serum data available but after both IV and oral administration would enable to calculate pretty much everything except the amount of BP retained by the skeleton after either IV or oral administration. Relative F, e.g. comparing two formulations, can be derived from serum concentrations alone using the Area Under the serum concentration time Curve (AUC), and other parameters can be assessed and compared also from such data such as Cmax, tmax and initial half-lives. Comparing serum AUCs as well as amounts excreted into urine after oral administration was used to assess the effect of the calcium chelator EDTA on the oral bioavailability of risedronate and subsequently the influence of concomitant food intake and gastric pH. This data in combination with bone turnover marker and bone mineral density data was used for the development of Atelvia, a risedronate/EDTA formulation that can be taken with food16–18.

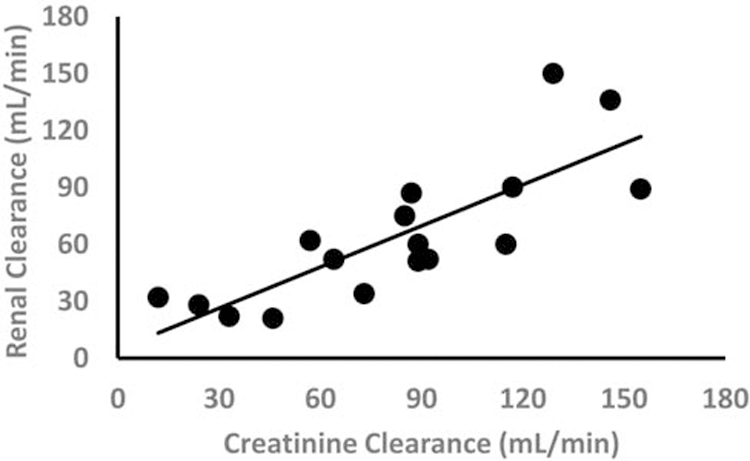

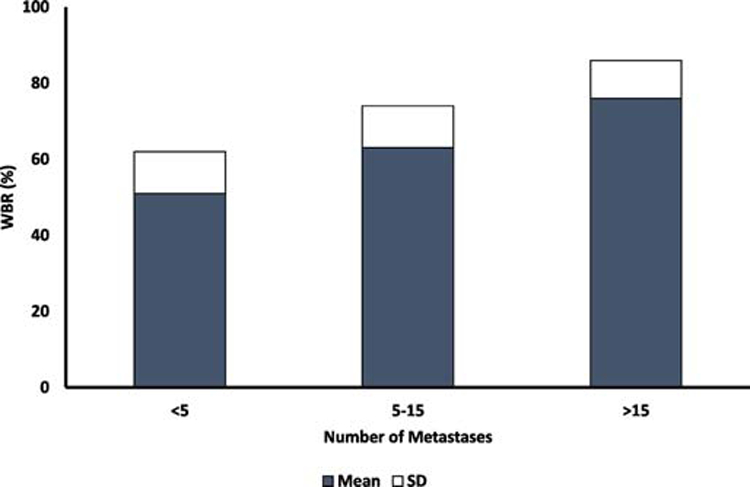

When studied in populations with different grades of renal impairment, the influence of renal function on the PK of the BP can be assessed, most clearly illustrated by the strong correlation between calculated creatinine clearance and renal clearance of pamidronate (figure 1)19. Although this data suggests that glomerular filtration is the main mode of renal excretion, other processes such as tubular secretion might also occur 12,20,21. The relative contributions of various renal excretion processes are likely dependent on the BP, species, and concentration. When studied in different metabolic bone diseases the influence of the disease on the PK of BPs can be determined, and this is nicely illustrated by the association of number of bone metastases with WBR of pamidronate in cancer patients (figure 2) as well as the pretreatment uNTX levels with WBR of olpadronate in patients with Paget’s disease of bone5,22. Another factor potentially affecting binding of BPs to bone as well as renal handling of BPs, is protein binding, albeit to our knowledge there are no clinical studies correlating protein binding to WBR in patients. Short-term urine data also indicate that binding properties of the BPs themselves determine how much of the BP is delivered to the skeleton. We and others previously concluded that BPs with better binding properties seem to have a higher WBR in patients 23.

Figure 1:

Linear relation between renal clearance of pamidronate disodium (CLr) and creatinine clearance (CLcr) in cancer patients receiving 90 mg of pamidronate disodium administered as a 4-hour infusion (r=0.81) (Reproduced from Berenson et al. 19)

Figure 2:

Whole Body Retention (WBR0-24h) according to the number of bone metastases in patients with bone metastases. N=6 patients < 5 metastases, N=22, 5-15 metastases and N=8 >15 metastases (Reproduced from Leyvraz et al22)

Depending on study design, mode of administration and whether only serum or urine or both are collected, short-term studies (up to 24 or 48) hours can thus provide useful pharmacokinetic information on BPs. The ideal study design is cross-over with several IV and oral doses and the collection of both serum and urine samples.

Long-term

It is a relatively more straightforward calculation to estimate the amount of BP delivered to the skeleton. But, it is still more complicated to estimate the amount of BP that remains on bone surfaces and within the skeleton over time. BPs are known to have long-term effects, which are likely related to a long-term presence of the drugs in the skeleton. Long-term presence of BPs could be determined by investigating the PK of BPs for longer than 24–48 hours. Given what we know about the long-term half-lives of BPs, caused by slow dissociation andrelease from a slowly decreasing depot of BP in the bone during osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, long-term PK of BPs is properly explored by collecting samples for years after termination of treatment. A study design that does not collect long-term PK data will not be able to adequately determine the BP’s true long-term half-lives and may therefore never explain why and when the anti-resorptive effect of BPs wears off. In addition, the use of an assay that is not able to quantify low levels of BPs in long-term samples also leads to underestimation of long-term half-lives. BPs are excreted into urine and most BPs can be quantified longer in urine than in serum samples as the levels in urine are usually higher for a longer period of time after drug administration presumably due to replenishment by drug slowly coming off the skeleton.

An ideal study design to explore long-term PK of BPs therefore consists of sampling for at least one year but preferably longer after termination of treatment. Sensitive assays should be used to quantify the BPs and if possible, both serum and urine samples should be collected.

There are several studies that successfully investigated long-term PK of BPs. The earliest study was sponsored by Merck and was conducted in Sheffield in the UK with IV alendronate, a formulation that was only brought to market in Japan 24. In this study in women with low bone mass, urine samples were collected over the 5 consecutive days of infusions and for a period of 1.5 years thereafter. Alendronate was quantified in the urine samples by HPLC. This study determined the amount of BP delivered to the skeleton and also showed that long-term excretion of alendronate in urine had a multi-exponential decline with a terminal half-life of 1–10 years. Another study investigating both short- and long-term serum and urinary PK was done in Leiden with five consecutive doses of IV olpadronate in patients with Paget’s disease of bone 5. Samples were collected during the infusions and for a period of 1 year thereafter. Again, the terminal half-life, determined from urinary data, was >1 year. The BP was not detectable in serum a day or two after the infusion, illustrating the usefulness of long-term urine data. The short-term urine data provided the amount of BP delivered to the skeleton, which was shown to be associated with both renal function and pretreatment rate of bone turnover. A third, very small, study was performed in pediatric osteoporosis patients who had had been administered pamidronate and had stopped treatment for three to twelve years25. The drug was still detectable in urine up to eight years after stop of treatment with decreasing concentrations related to the years after stop of treatment, again illustrating the power of long-term urinary data.

There has always been a discussion about if and how the different physicochemical characteristics of BPs translate into differences in the clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. As mentioned, we previously collated data that suggest WBR loosely correlates with binding properties23. However, much of that work compares data from different studies, which inherently is imprecise due to inter-study variability. Much of the above-mentioned discussion has been about the differences between alendronate and risedronate with the general idea that risedronate has weaker binding properties, and therefore has a lower WBR and perhaps a shorter long-term presence in the bone. This appears to be supported by bone turnover marker data from two separate studies that suggest that the anti-resorptive effect of risedronate is less and that it also wears off quicker after several years off treatment 26,27. Two groups of investigators decided to study this directly by comparing risedronate and alendronate in head-to-head studies.

The first study, performed by the group at the University of Sheffield, compared the bone turnover markers during and after alendronate, risedronate (and ibandronate) treatment in a single head-to-head study (TRIO and TRIO-offset) 28,29. As discussed elsewhere in this Themed Issue, the TRIO study showed that 2 years of oral weekly risedronate indeed results in less suppression of bone resorption than 2 years of oral alendronate (and ibandronate) treatment28. However, the TRIO-offset study showed that stopping treatment resulted in similar bone resorption marker patterns for all three BPs. Bone resorption markers increased slowly during 2 years to a level that was similar for all three BPs but lower than pretreatment baseline29.

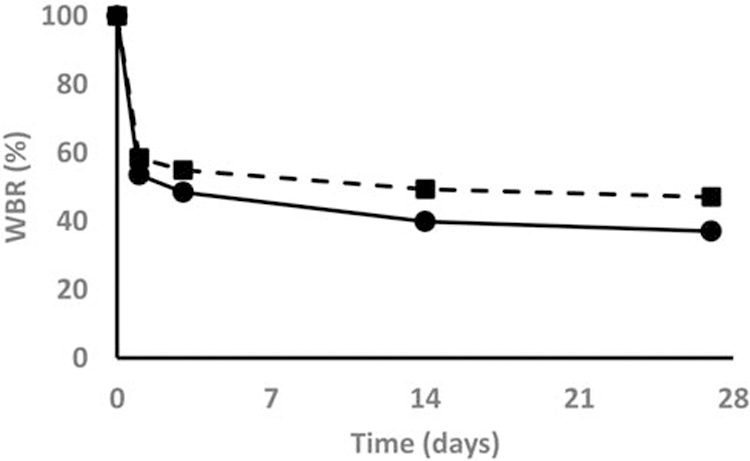

The second study investigating short- and long-term pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of alendronate and risedronate was performed by a group at P&GP (Roger Phipps, Brad Keck, Barbara Kuzman, Darrell Russell, Lu Sun, David Burgio) in collaboration with Bob Lindsay (Columbia University) and Claus Christiansen (University of Copenhagen). This data was unfortunately never published, except some of it in abstract form30, and so here we will present some details of its findings. In this study a single 14C-labeled IV dose of either alendronate (n=17) or risedronate (n=15) was administered to postmenopausal women with an average age of 60 years and low bone mass or osteoporosis in a dose equivalent to the amount that would normally reach systemic circulation after an oral weekly dose of each bisphosphonate. This was followed by the respective weekly oral doses of the same drug (not 14C-labeled) for 52-weeks (risedronate 35 mg and alendronate 70 mg). Urine and blood samples were collected during the 52 weeks and in those samples 14C-labeled alendronate and risedronate, and biochemical markers of bone turnover were quantified, the former by accelerator mass spectrometry. The pharmacokinetics of this study was therefore from IV alendronate and risedronate while the pharmacodynamics reflected the effect of weekly oral treatment with these drugs. After the 1 year of treatment a second dose of IV 14C-labeled alendronate or risedronate was given at the same dose as at the start of the study, followed by blood and urine sampling for an additional period of 28 days. Again 14C-labeled drugs were quantified to compare PK after a first dose in BP naïve patients (or those who had not been on any BPs or other bone drug for at least 1 year) and after one year of oral weekly treatment. Exclusion criteria for this IRB-approved study included renal impairment and other metabolic bone diseases.

Serum CTX and NTX concentrations, determined in samples collected at baseline, day 14, 28, 90, 182 and 363, were decreased by both alendronate and risedronate treatment, with lower concentrations for alendronate, albeit differences between groups were not statistically significant for any of the time points. For bone specific alkaline phosphatase, there were significant decreases at 6 and 12 months with alendronate and at 6 months with risedronate, but again the differences were not significant at either time point. The lack of statistical difference might be related to the small number of patients in both study groups.

Percent cumulative excretion (A’e) over the first 27 days after IV administration was significantly greater with risedronate compared with alendronate (62% vs 52%, table 1). Although these differences were smaller than reported earlier23, this observation is in line with the weaker binding properties of risedronate, resulting in less retention, at least during the first four weeks. Other PK parameters were calculated from both serum and urine data collected during 12 months and are listed in table 2. Some of these parameters such as Cmax, AUC and Ae (absolute) were higher for alendronate simply because the standard dose of alendronate (0.45 mg IV, mimicking 70 mg PO) was higher than the standard dose of risedronate (0.23 mg IV, mimicking 35 mg PO). Clearance, both renal and nonrenal, were also higher for alendronate, which is in line with higher uptake of alendronate by the bone and suggests slightly different renal handling of the compounds. Most interesting though was that there was no difference in apparent volume of distribution, and that the terminal half-life of both drugs was the same (2731 and 2746h, respectively). Therefore, while initially there was a small but clear difference in retention between the drugs, long-term elimination was similar for both drugs, and therefore any difference that exists shortly after the beginning of treatment is likely to persist. This might explain why K-PD models work so well to describe the effects of BPs: Dose and potency are the two key-parameters that determine the effects of BPs in these models (see below). This important study also, for once, suggests that there might be no difference in long-term pharmacokinetics between BPs.

Table 1:

Cumulative urinary excretion (%) over 27 days after first and second IV dose

| Risedronate | Alendronate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | Day | |||||||

| 1 | 3 | 14 | 27 | 1 | 3 | 14 | 27 | |

| 1st IV Dose | 46.46 | 51.56 | 60.08 | 62.88 | 41.50 | 45.06* | 50.62* | 52.88* |

| 2nd IV Dose | 46.61 | 51.90 | 60.82 | 64.64 | 45.63 | 50.03 | 59.83 | 63.41 |

| Ratio | 1.003 | 1.007 | 1.012 | 1.028 | 1.100 | 1.110 | 1.182* | 1.200* |

Mean cumulative excretion as % administered dose at 1,3,14 and 27 days after 1st and 2nd IV dose of 14C-labeled drugs

Numbers for excretion: risedronate, n=15 for 1st and n=14 for 2nd; alendronate, n=17 for 1st and n=14 for 2nd dose

Paired data only for ration: risedronate n=14 for all days; alendronate n=14 for days 1 and 3, n=14 for days 14 and 27

P<0.05 corresponding dose of risedronate to alendronate

Table 2:

Pharmacokinetic parameters post 1st dose calculated from data collected during 12 months.

| Parameter | Risedronate | Alendronate | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ae (ug) | 164.18 | 289.59 | <0.0001 |

| A’e (%) | 72.2 | 63.18 | 0.0177 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | |||

| AUC(h*pg/mL) | 61,131 | 83,167 | <0.0001 |

| CL/BW (L/h/kg) | 0.056 | 0.084 | <0.0001 |

| CLnr/BW (L/h/kg) | 0.017 | 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| CLr/BW (L/h/kg) | 0.04 | 0.053 | 0.0038 |

| t½,z (h) | 2731 | 2746 | 0.6548 |

| Vss/BW (L/kg) | 32.82 | 35.67 | 0.1890 |

Least-squares geometric means are presented for AUC, CL/BW, CLr/BW

Least-squares arithmic means for Ae, CLnr/BW

Medians are presented for A’e, t½,z, Vss/BW

Ae is the cumulative amount of bisphosphonate excreted in urine over the designated time interval; A’e is the cumulative percentage of the IV dose of bisphosphonate excreted in urine over the designated time interval; CL/BW is the clearance per kg of body weight; CLnr is nonrenal clearance; CLr is renal clearance; t½,z is the half-life of the terminal exponential phase; Vss is the apparent volume of distribution at steady state

Interestingly, there was no difference in A’e between the first and the second IV administration for risedronate, in contrast to alendronate for which there was a small but significantly higher A’e with the second IV administration. The differences were small, but this observation does suggest that in contrast to risedronate, one year of alendronate treatment decreases the number of potential BP binding sites likely due to lower turnover rates, resulting in slightly less retention. This data may also be relevant to the discussion on saturation of binding sites for BPs, which at one time was only deemed relevant for high doses of etidronate 31. Our data suggest that this discussion might also extend to other BPs and at considerably lower doses.

There were no significant correlations between percent change in NTX, CTX or BAP and in change in Ae or A’e. This suggests that the described PK after IV administration might not have been relevant for the PD during oral treatment with alendronate and risedronate. Complementary data might result in a more complete picture and perhaps identification of these correlations. Serum and urine data after oral treatment would be such data, which would enable assessment of oral availability and other PK parameters, which is of course also a major determinant of the amount of BP delivered to the skeleton after oral administration. The application of some PK-PD modeling to this data might also reveal some more complex relationships between PK and PD of the BPs and perhaps differences between them (see below).

In 2011, Peris et al apparently had an opposing observation 32. This team compared long-term release of alendronate and risedronate in urine of women with osteoporosis and tried to correlate their findings with bone turnover marker data in the same patients. Their data suggested that risedronate was non-detectable in urine samples sooner than alendronate, possibly explaining why the anti-resorptive effect of risedronate wore off faster as reflected by increasing bone turnover marker levels. Two major limitations of this study were the much smaller number of patients on risedronate (n=7) compared with alendronate (n=36), and the use of a more sensitive assay for alendronate than for risedronate. Combined with a higher oral absolute dose of alendronate, these results may therefore have been overinterpreted, albeit that overall the data is in line with most other studies, including one previously described in more detail.

The above-mentioned analyses are mainly focused on using non-compartmental pharmacokinetic analyses. Using model-based analysis of the drug concentration data such as multi-compartmental analyses can sometimes improve the data analysis and may sometimes be able to describe in more detail what the concentration of the BPs in the various bone compartments are over time 33. However, although these models enable a more extensive analysis of the same data set than non-compartmental analysis, the need for serum and urine data after both IV and oral administration remains clear for an optimal description of the pharmacokinetics of BPs.

Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacokinetics of BPs have been studied extensively and they might explain some effects of the drugs, wanted and unwanted. Relationships between effects and pharmacokinetics, also known as pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) relationships of BPs have been studied at various levels, ranging from relatively simple correlations to highly complex systems pharmacology analyses33.

Examples of simple correlative studies include the above-mentioned study comparing the PK and PD of alendronate and risedronate. Both absolute as well as relative changes of CTX and NTX during oral treatment were compared with absolute and relative amounts of BP retained after an IV dose. One study that tried to do the same included urinary excretion and the changes of NTX during and after five consecutive days of olpadronate treatment in patients with Paget’s disease of bone5. This study failed to demonstrate any correlations between amount of BP excreted in urine and changes in bone resorption markers, probably because NTX levels were maximally suppressed in all patients for the entire duration of the study (i.e. 1 year). The study was conducted at the very high end of the dose response curve, which is never optimal for the study of PK-PD relationships. Similar studies such as with IV pamidronate and zoledronate in cancer did show correlations between dose and suppression of bone resorption34,35. It is not clear if this data was ever analyzed as a correlation between WBR of zoledronate and decrease of bone resorption levels. The then perceived safety of BPs though led zoledronate’s developer, and perhaps also other pharmaceutical companies, to select dose regimens that were on the high side for their subsequent clinical development studies, ensuring that most, if not all, patients would have a high suppression of bone resorption during treatment. This has of course turned out to be good in terms of efficacy but less so for safety, especially with the intense dose regimens used for the treatment of bone metastases that are associated with a higher incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw, albeit this serious potential side effect of BPs is still rare and not fully understood 36.

One of the first examples of a PK-PD model in patients was that of three-monthly IV pamidronate in patients with osteoporosis with urinary hydroxyproline as bone resorption marker 37. This study set the tone for the use of modeling and simulation to try to explain some the bone turnover marker observations over time during and after the administration of drugs. The main components of these mathematical models, which are derived from both short- and long-term serum and urine BP and bone turnover marker data, is that they describe the amount and sometimes concentration of the BPs at the bone and that they link this to an anti-resorptive effect, most often by inhibiting the production of the bone resorption markers. While difficult, some of these models have been validated and they seem to perform well, estimating the true concentration of the BPs at the bone 38,39. This is relevant conceptually as BP embedded in bone is not metabolized and is not pharmacologically active until release. It is the BP that is being released from bone during osteoclast-mediated bone resorption that is primarily responsible for the pharmacological activity observed in vivo. Amounts of BP in the various bone compartments are a driver of this concentration of BP at the bone surface, which is probably the reason why models that determine the amount of BP at skeletal surfaces are good descriptors of the pharmacokinetics of BPs as well as good descriptors of bone resorption markers during BP treatment. The most reliable models are derived from studies that collected the PK and the PD data simultaneously and were validated prospectively. One of the best validated PK-PD models was developed by Roche Pharma for ibandronate 40. Using large datasets both PK and PD could be adequately described and the models were subsequently used in support of the further clinical validation of Ibandronate 41. Worth noting is that the investigators ended up fully developing a K-PD model rather than a PK-PD model for ibandronate. This was partly because there was only limited long-term PK data available for ibandronate. A K-PD model for BPs uses dose as its major PK parameter to estimate the amount of BP at the bone and subsequently uses only PD observations to link the estimated amount of BP at the skeleton to the bone turnover marker patterns. Validation studies demonstrated that this approach works quite well to describe and simulate bone turnover marker data. Interestingly, given the probably very similar long-term half-lives of all clinically used BPs, as described above for alendronate and risedronate, this K-PD approach might therefore be correct. To be able to derive good PK-PD (and K-PD) models, data should come from studies with a range of doses and therefore differences in the extent of bone resorption reduction induced by the BP. The study duration should preferably also see resolution of the effect of the BP. This approach can for example be derived from the earlier mentioned zoledronate in cancer studies, and enables a good capture of the various parameters of so-called inhibitory indirect effect models, which form the PD section of many of the K-PD and PK-PD models.

Finally, Riggs et al. and others have taken PK-PD modeling and simulation for BPs and other drugs to a whole new level by quantitatively linking every process that is known to take place in bone and having drugs, hormones, minerals and vitamins have a quantitative effect of these systems42. These systems pharmacology models, which are already used for development in other drug classes, will become more comprehensive for BPs with each new data set that is factored in to them33. Some of these improvements might include new insights into the exact biodistribution and mechanisms of action of BPs such as the penetration into the osteocyte network and the effects BPs have on these cells 43–45. Again, the concentration at some sites on the bone surface, particularly the higher turnover sites where pharmacodynamics should be driven, likely exceed the average concentration of BP on the total skeleton, and thus provides unique challenges to PK/PD estimates. The systems pharmacology models might also be useful to explain and perhaps predict what happens during simultaneous and sequential therapy of BPs with other drugs such as denosumab and PTH. In addition, these and the aforementioned PK-PD models might be useful for the development of other BPs, including those that have a predominant effect on osteoblasts, and those that can be used as carriers to bring other drugs to the bone such as antibiotics and anti-cancer drugs, the dose regimens of which will be quite challenging 46,47.

Conclusion and future perspective

Clinical PK and PK-PD studies with BPs in humans have helped improved understanding of these most useful drugs for metabolic bone diseases. Optimal studies are characterized by the collection of short-and long-term PK and PD data in serum and urine during various dose regimens with different effects, combined with mathematical modeling and simulation techniques. These studies have been and continue to be useful for the development of BPs for other metabolic bone diseases that include the study of off bone effects of BPs and the use of BPs for targeting other drug actives to bone. Newer potential indications for BPs include neurodegenerative diseases, infectious diseases, cardiovascular disease and cancer. Optimizing dose regimens for these applications will require such models to also study BP distribution and effects away from the skeleton as well as for the target and release kinetics of BP drug conjugates 48, which may be quite challenging for the average bone researcher, but will also be very rewarding.

Figure 3:

28 day cumulative urinary excretion after first IV dose of Alendronate (Squares) and Risedronate (Circles)

Acknowledgements

FHE is supported by grant R42-DE025789-02 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), grant 2R44 AI125060-02 from the NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and grant R43AR073727 from the NIH National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS).

SC is supported by grant UL1TR001873 from the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Serge Cremers, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY 10032, United States of America.

Frank (Hal) Ebetino, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY 14627, United States of America and Chief Scientific Officer, BioVinc, Pasadena, CA 91107, United States of America.

Roger Phipps, School of Pharmacy, Husson University, Bangor, ME 04401, United States of America.

References

- 1.Fleisch H, Russell RG & Francis MD Diphosphonates inhibit hydroxyapatite dissolution in vitro and bone resorption in tissue culture and in vivo. Science 165, 1262–1264, doi: 10.1126/science.165.3899.1262 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleisch H, Russell RG, Simpson B & Muhlbauer RC Prevention by a diphosphonate of immobilization “osteoporosis” in rats. Nature 223, 211–212, doi: 10.1038/223211a0 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francis MD, Russell RG & Fleisch H Diphosphonates inhibit formation of calcium phosphate crystals in vitro and pathological calcification in vivo. Science 165, 1264–1266, doi: 10.1126/science.165.3899.1264 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassett CA et al. Diphosphonates in the treatment of myositis ossificans. Lancet 2, 845, doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)92293-4 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cremers SC et al. Relationships between pharmacokinetics and rate of bone turnover after intravenous bisphosphonate (olpadronate) in patients with Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res 18, 868–875, doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.5.868 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fogelman I et al. The use of whole-body retention of Tc-99m diphosphonate in the diagnosis of metabolic bone disease. J Nucl Med 19, 270–275 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyldstrup L, McNair P, Finn Jensen G, Borg Mogensen N & Transbol I Measurements of whole body retention of diphosphonate and other indices of bone metabolism in 125 normals: dependency on age, sex and glomerular filtration. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 44, 673–678, doi: 10.3109/00365518409083629 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyldstrup L, Mogensen N, Jensen GF, McNair P & Transbol I Urinary 99m-Tc-diphosphonate excretion as a simple method to quantify bone metabolism. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 44, 105–109, doi: 10.3109/00365518409161390 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen T et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zoledronic acid in cancer patients with bone metastases. J Clin Pharmacol 42, 1228–1236, doi: 10.1177/009127002762491316 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skerjanec A et al. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zoledronic acid in cancer patients with varying degrees of renal function. J Clin Pharmacol 43, 154–162, doi: 10.1177/0091270002239824 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cremers SC et al. Skeletal retention of bisphosphonate (pamidronate) and its relation to the rate of bone resorption in patients with breast cancer and bone metastases. J Bone Miner Res 20, 1543–1547, doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050522 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett J, Worth E, Bauss F & Epstein S Ibandronate: a clinical pharmacological and pharmacokinetic update. J Clin Pharmacol 44, 951–965, doi: 10.1177/0091270004267594 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell DY et al. Risedronate pharmacokinetics and intra- and inter-subject variability upon single-dose intravenous and oral administration. Pharm Res 18, 166–170, doi: 10.1023/a:1011024200280 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gertz BJ et al. Studies of the oral bioavailability of alendronate. Clin Pharmacol Ther 58, 288–298, doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90245-7 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cremers SC et al. Absorption of the oral bisphosphonate alendronate in osteoporotic patients with Crohn’s disease. Osteoporos Int 16, 1727–1730, doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1911-7 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.FDA. FDA clinical pharmacology and biopharmaceutics review - Atelvia, <https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2010/022560orig1s000clinpharmr.pdf> (2010).

- 17.Kim JS, Jang SW, Son M, Kim BM & Kang MJ Enteric-coated tablet of risedronate sodium in combination with phytic acid, a natural chelating agent, for improved oral bioavailability. Eur J Pharm Sci 82, 45–51, doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.11.011 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClung MR et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel delayed-release risedronate 35 mg once-a-week tablet. Osteoporos Int 23, 267–276, doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1791-y (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berenson JR et al. Pharmacokinetics of pamidronate disodium in patients with cancer with normal or impaired renal function. J Clin Pharmacol 37, 285–290, doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04304.x (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Troehler U, Bonjour JP & Fleisch H Renal secretion of diphosphonates in rats. Kidney Int 8, 6–13, doi: 10.1038/ki.1975.70 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin JH, Chen IW, Deluna FA & Hichens M Renal handling of alendronate in rats. An uncharacterized renal transport system. Drug Metab Dispos 20, 608–613 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leyvraz S et al. Pharmacokinetics of pamidronate in patients with bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst 84, 788–792, doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.10.788 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cremers S, Drake MT, Ebetino FH, Bilezikian JP & Russell RGG Pharmacology of bisphosphonates. Br J Clin Pharmacol 85, 1052–1062, doi: 10.1111/bcp.13867 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan SA et al. Elimination and biochemical responses to intravenous alendronate in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 12, 1700–1707, doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.10.1700 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papapoulos SE & Cremers SC Prolonged bisphosphonate release after treatment in children. N Engl J Med 356, 1075–1076, doi: 10.1056/NEJMc062792 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Black DM et al. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA 296, 2927–2938, doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2927 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eastell R, Hannon RA, Wenderoth D, Rodriguez-Moreno J & Sawicki A Effect of stopping risedronate after long-term treatment on bone turnover. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96, 3367–3373, doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0412 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naylor KE et al. Response of bone turnover markers to three oral bisphosphonate therapies in postmenopausal osteoporosis: the TRIO study. Osteoporos Int 27, 21–31, doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3145-7 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naylor KE et al. Effects of discontinuing oral bisphosphonate treatments for postmenopausal osteoporosis on bone turnover markers and bone density. Osteoporos Int 29, 1407–1417, doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4460-6 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phipps R et al. Head-to-head comparison of risedronate and alendronate pharmacokinetics at clinical doses. Bone 34, S81–S82 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasting GB & Francis MD Retention of etidronate in human, dog, and rat. J Bone Miner Res 7, 513–522, doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070507 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peris P et al. Prolonged bisphosphonate release after treatment in women with osteoporosis. Relationship with bone turnover. Bone 49, 706–709, doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.06.027 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riggs MM & Cremers S Pharmacometrics and systems pharmacology for metabolic bone diseases. Br J Clin Pharmacol 85, 1136–1146, doi: 10.1111/bcp.13881 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berenson JR et al. A Phase I, open label, dose ranging trial of intravenous bolus zoledronic acid, a novel bisphosphonate, in cancer patients with metastatic bone disease. Cancer 91, 144–154 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berenson JR et al. A phase I dose-ranging trial of monthly infusions of zoledronic acid for the treatment of osteolytic bone metastases. Clin Cancer Res 7, 478–485 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khosla S et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res 22, 1479–1491, doi: 10.1359/jbmr.0707onj (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cremers S et al. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic model for intravenous bisphosphonate (pamidronate) in osteoporosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 57, 883–890, doi: 10.1007/s00228-001-0411-8 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sedghizadeh PP et al. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling for assessing risk of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 115, 224–232, doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.08.455 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones AC & Sedghizadeh PP Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws is caused by dental procedures that violate oral epithelium; this is no longer a mysterious disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 117, 392–393, doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.09.076 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pillai G et al. A semimechanistic and mechanistic population PK-PD model for biomarker response to ibandronate, a new bisphosphonate for the treatment of osteoporosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 58, 618–631, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02224.x (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zaidi M, Epstein S & Friend K Modeling of serum C-telopeptide levels with daily and monthly oral ibandronate in humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1068, 560–563, doi: 10.1196/annals.1346.058 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peterson MC & Riggs MM A physiologically based mathematical model of integrated calcium homeostasis and bone remodeling. Bone 46, 49–63, doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.08.053 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roelofs AJ et al. Fluorescent risedronate analogues reveal bisphosphonate uptake by bone marrow monocytes and localization around osteocytes in vivo. J Bone Miner Res 25, 606–616, doi: 10.1359/jbmr.091009 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roelofs AJ, Thompson K, Ebetino FH, Rogers MJ & Coxon FP Bisphosphonates: molecular mechanisms of action and effects on bone cells, monocytes and macrophages. Curr Pharm Des 16, 2950–2960, doi: 10.2174/138161210793563635 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roelofs AJ et al. Influence of bone affinity on the skeletal distribution of fluorescently labeled bisphosphonates in vivo. J Bone Miner Res 27, 835–847, doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1543 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang H et al. Synthesis of a Bone-Targeted Bortezomib with In Vivo Anti-Myeloma Effects in Mice. Pharmaceutics 10, doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10030154 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sedghizadeh PP et al. Design, Synthesis, and Antimicrobial Evaluation of a Novel Bone-Targeting Bisphosphonate-Ciprofloxacin Conjugate for the Treatment of Osteomyelitis Biofilms. J Med Chem 60, 2326–2343, doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01615 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reid IR et al. Effects of Zoledronate on Cancer, Cardiac Events, and Mortality in Osteopenic Older Women. J Bone Miner Res 35, 20–27, doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3860 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]