Acute pancreatitis is the most common major complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), occurring in 3–15% of cases and in up to 40% of procedures if preventive measures are not employed. About 5% of patients who develop pancreatitis after ERCP have a severe course, characterized by local and systemic complications, prolonged hospitalization, and occasional death.1 Considering that approximately 600,000 ERCPs are performed annually in the United States, ERCP-related pancreatitis is an important and costly clinical problem.

Rectally administered non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have come to play a central role in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. In 2008, a meta-analysis of exploratory trials suggested benefit associated with rectal indomethacin or diclofenac.2 In 2012, a confirmatory randomized trial, on which one of us (BJE) was an author, demonstrated that a single 100 mg dose of indomethacin given at the time of ERCP reduced the incidence of pancreatitis by approximately 50%.3 Following the publication of this and other trials, as well as changes to professional society guidelines,4 the use of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis has substantially increased.

Unlike other indications for which NSAIDs are effective by any route of delivery, post-ERCP pancreatitis appears to be prevented only by rectal administration immediately before, during, or after the procedure.5 The underlying reasons are unclear, but first-pass liver metabolism of oral NSAIDS and drug disposition by the rectal microbiome may be important factors. Although both indomethacin and diclofenac are effective, rectal diclofenac is not commercially available in the US. Thus, there is no alternative to rectal indomethacin for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

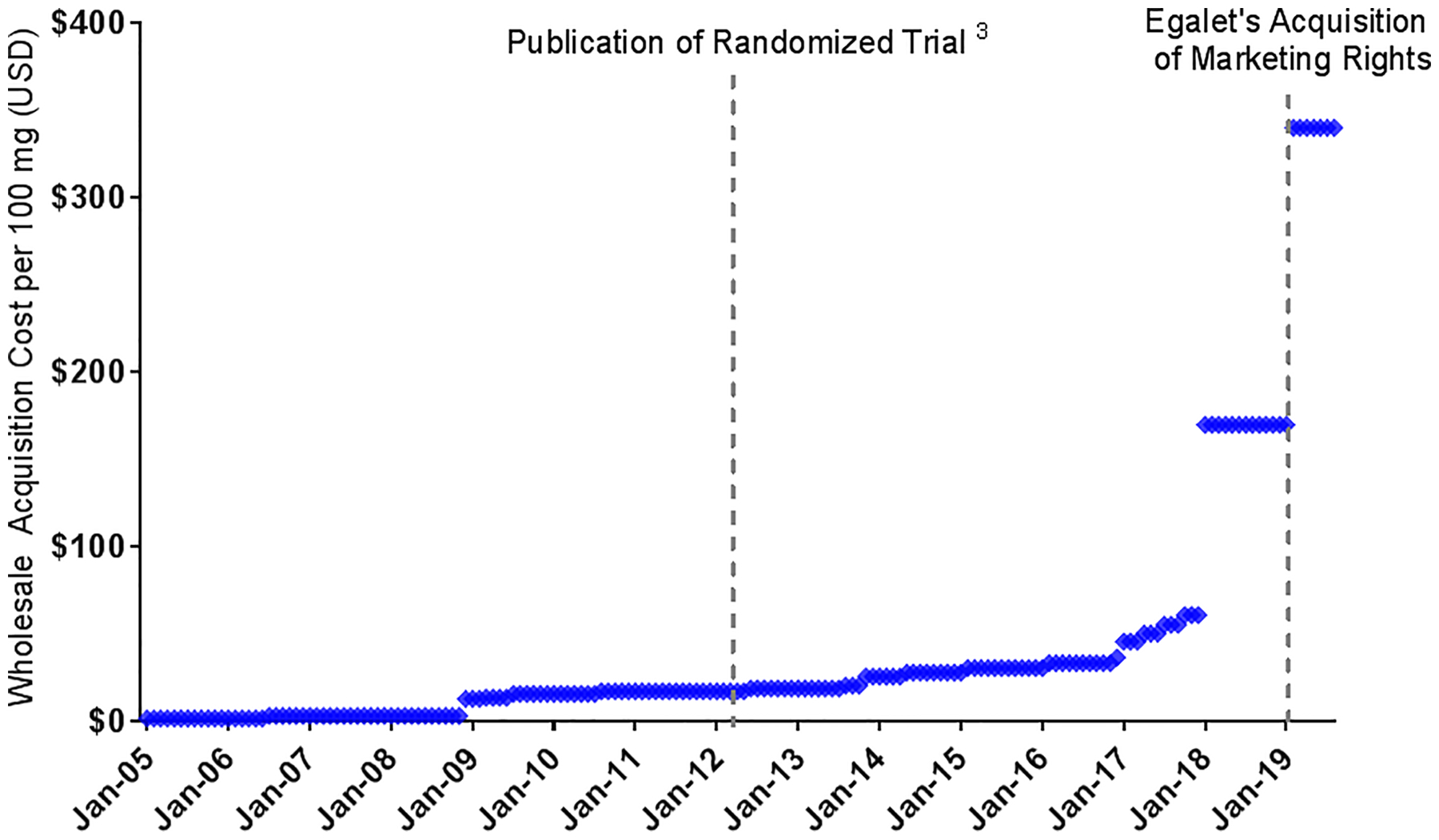

In 1965, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first approved indomethacin; in 1984 it approved a suppository formulation.6 Due to the widespread availability of oral alternatives, indomethacin suppositories had limited use for many years. Only one manufacturer and one distributor supplied a small commercial market. In 2005, the wholesale acquisition cost of a 100 mg dose was approximately $2 (Figure). In 2012, when the effectiveness of rectal indomethacin for post-ERCP pancreatitis was demonstrated, the price had risen to $17. By 2019, the price was $340, representing an approximate 20-fold increase from 2012. By comparison, the average retail cost of widely used generic drugs in the US dropped during this time period.7

Figure.

100 mg Dose of Rectal Indomethacin, January 2005 to September 2019. Data Source: AnalySource® - Data are reprinted by AnalySource with permission by First Databank, Inc (http://www.fdbhealth.com/policies/drug-pricing-policy/) and all rights reserved. © 2019

In theory, increasing demand for a single-source medication, such as rectal indomethacin, should lead additional suppliers to enter the market, lowering prices through competition. However, since the market for a drug to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis is relatively small, potential profits from the sale of rectal indomethacin have been insufficient to encourage additional companies to manufacture and distribute rectal indomethacin. Thus, one manufacturer has a de facto monopoly.

In the case of indomethacin suppositories, the drug was sold for years by Iroko Pharmaceuticals (Philadelphia, PA), which quintupled its price from $34 to $170 per 100 mg dose in 2017 (Figure). The reasons for this sharp price increase are not clear. Then, at the beginning of 2019, the company sold 4 of its drugs, including indomethacin suppositories, to a small company named Egalet [Wayne, PA], which was in the midst of bankruptcy proceedings. After closing this deal in the first quarter of 2019, Egalet – now named Zyla Life Sciences – doubled the wholesale acquisition cost of indomethacin suppositories, along with the prices of other drugs it acquired.8

Two issues complicate the pricing of rectal indomethacin. First, the medication is not FDA approved for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. The impetus for the 2012 investigator-initiated (and NIH-sponsored) trial of indomethacin for ERCP was scientific and not commercial. Because there was no intent to change the prescribing information, the FDA, granted an exemption from filing an investigational new drug (IND) application. In the absence of FDA approval of an IND, the use of rectal indomethacin for preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis remains off-label, which means that insurers may not provide coverage. Thus, patients may directly bear the financial burden of these sizeable price increases.

Second, rectal indomethacin is often subject to hospital pharmacy upcharges. When a medication such as indomethacin suppositories is administered in a hospital outpatient department (where most ERCPs are performed), it is are subject to the hospital’s chargemaster. Thus, the hospital’s charge for the medication may be double or triple the list price, or more in some cases. For example, in a review of publicly reported 2019 hospital chargemasters in California, we found that the price of 100 mg of rectal indomethacin at five hospitals that disclosed these charges ranged from $650 to over $5000.9 Although pharmacy upcharges are intended to support infrastructure and personnel to store and dispense the medication, these charges are often inflated during price negotiations with insurers, who ultimately pay a fraction of the listed charge. For the off-label use of drugs that are not covered by insurance, or Medicare Part B (which does not pay for hospital outpatient drugs like indomethacin that are considered ‘usually self-administered’10), the patient may be billed the full hospital chargemaster price.

The story of rectal indomethacin demonstrates once again the failure of the market alone to ensure sufficient supply and competition for single-source drugs in the US. The FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 created a pathway for the designation of drugs with inadequate competition as ‘Competitive Generic Therapies,’ meaning there are no generic medications or only one generic version available, as is the case for indomethacin suppositories. This designation provides for expedited approval of new generic drugs and additional incentives for market entry. Such regulatory incentives, however, do not guarantee the entry of additional suppliers to the market. Other policy solutions have been proposed, including the importation of medications from other countries in instances of inadequate generic competition with associated price hikes, and government or non-profit manufacturing of drugs.

Another approach would be to source rectal indomethacin from compounding pharmacies, which, based on our inquiries when writing this article, charge as little as $2 for a 100 mg dose. If large numbers of hospitals were to use compounding pharmacies as their source of indomethacin suppositories, the manufacturer might reconsider its pricing strategy. The market for indomethacin suppositories, however, may not be large enough to elicit the expected response. Moreover, the widespread use of compounding pharmacies may raise concerns about medication quality and patient safety. Although concerns about the safety of compounded medications have usually applied to injectable products, these pharmacies have less regulatory oversight than drug manufacturers. Moreover, the FDA has typically limited widespread compounding when an approved product is available.

Rectal indomethacin is yet another example of a single-source drug whose price has been markedly increased by companies seeking to maximize profits in a regulatory environment that does not prevent them from doing so. Other recent and well-publicized examples of such price increases include those by Turing Pharmaceuticals and Valeant Pharmaceuticals; both companies abruptly raising prices on several newly acquired generic drugs after judging the market too small to sustain additional competition. The story of indomethacin suppositories, however, has unique features, given the medication’s off-label status and its administration in hospital outpatient departments. Given the intense and ongoing scrutiny of both drug pricing and hospital costs, effective solutions are needed to ensure access to rectal indomethacin without exorbitant prices that are often borne by patients.

Funding/Support:

Dr. Hernandez is funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (grant number K01HL142847).

Footnotes

Financial Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Elmunzer is a consultant for Takeda Pharmaceuticals but has no financial conflicts of interest related directly to rectal indomethacin.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: This work represents the opinions of the authors alone and does not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

References

- 1.Kochar B, Akshintala VS, Afghani E, et al. Incidence, severity, and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review by using randomized, controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:143–149 e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elmunzer BJ, Waljee AK, Elta GH, et al. A meta-analysis of rectal NSAIDs in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gut 2008;57:1262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA, et al. A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1414–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Elmunzer BJ, et al. Prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - updated June 2014. Endoscopy 2014;46:799–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubiliun NM, Adams MA, Akshintala VS, et al. Evaluation of Pharmacologic Prevention of Pancreatitis After Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography: A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=017814. Accessed 1/2/2020.

- 7.Schondelmeyer SW, Purvis L. Trends in Retail Prices of Generic Prescription Drugs Widely Used by Older Americans: 2017 Year-End Update: AARP RxPrice Watch Report. April 2019. Available at: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/04/trends-in-retail-prices-of-generic-prescription-drugs-widely-used-by-older-americans.pdf.Lastaccessed1/2/2020.

- 8.Herman B Drug company raises price of pain reliever by 70%. Axios. February 14, 2019. Available at: https://www.axios.com/drug-company-egalet-zorvolex-price-hike-6aceeecf-9a36-40e2-9297-bc23cfef3ffe.html.Lastaccessed1/2/2020.

- 9.California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. 2019 Chargemasters. Accessed on December 13, 2019 Available at https://oshpd.ca.gov/data-and-reports/cost-transparency/hospital-chargemasters/2019-chargemasters/.

- 10.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General (OIG). OIG Policy Statement Regarding Hospitals That Discount or Waive Amounts Owed by Medicare Beneficiaries for Self-Administered Drugs Dispensed in Outpatient Settings. October 29, 2015 Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/alerts/guidance/policy-10302015.pdf. Accessed on December 13, 2019. [Google Scholar]