Abstract

In mycobacteria, phosphatidylinositol (PI) acts as a common lipid anchor for key components of the cell wall, including the glycolipids phosphatidylinositol mannoside (PIM), lipomannan (LM) and lipoarabinomannan (LAM). Glycolipids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis, are important virulence factors that modulate the host immune response. The identity-defining step in PI biosynthesis in prokaryotes, unique to mycobacteria and few other bacterial species, is the reaction between CDP-diacylglycerol and inositol-phosphate to yield phosphatidylinositol-phosphate, the immediate precursor to PI. This reaction is catalyzed by the CDP-alcohol phosphotransferase phosphatidylinositol-phosphate synthase (PIPS), an essential enzyme for mycobacterial viability. Here we present structures of PIPS from Mycobacterium kansasii (MkPIPS) with and without evidence of donor and acceptor substrate binding obtained using a crystal engineering approach. MkPIPS is 86% identical to the ortholog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and catalytically active. Functional experiments guided by our structural results allowed us to further characterize the molecular determinants of substrate specificity and catalysis in a new mycobacterial species. This work provides a framework to strengthen our understanding of phosphatidylinositol-phosphate biosynthesis in the context of mycobacterial pathogens.

Keywords: Crystallography, tuberculosis, inositol-phosphate, CDP-alcohol phosphotransferase

Introduction

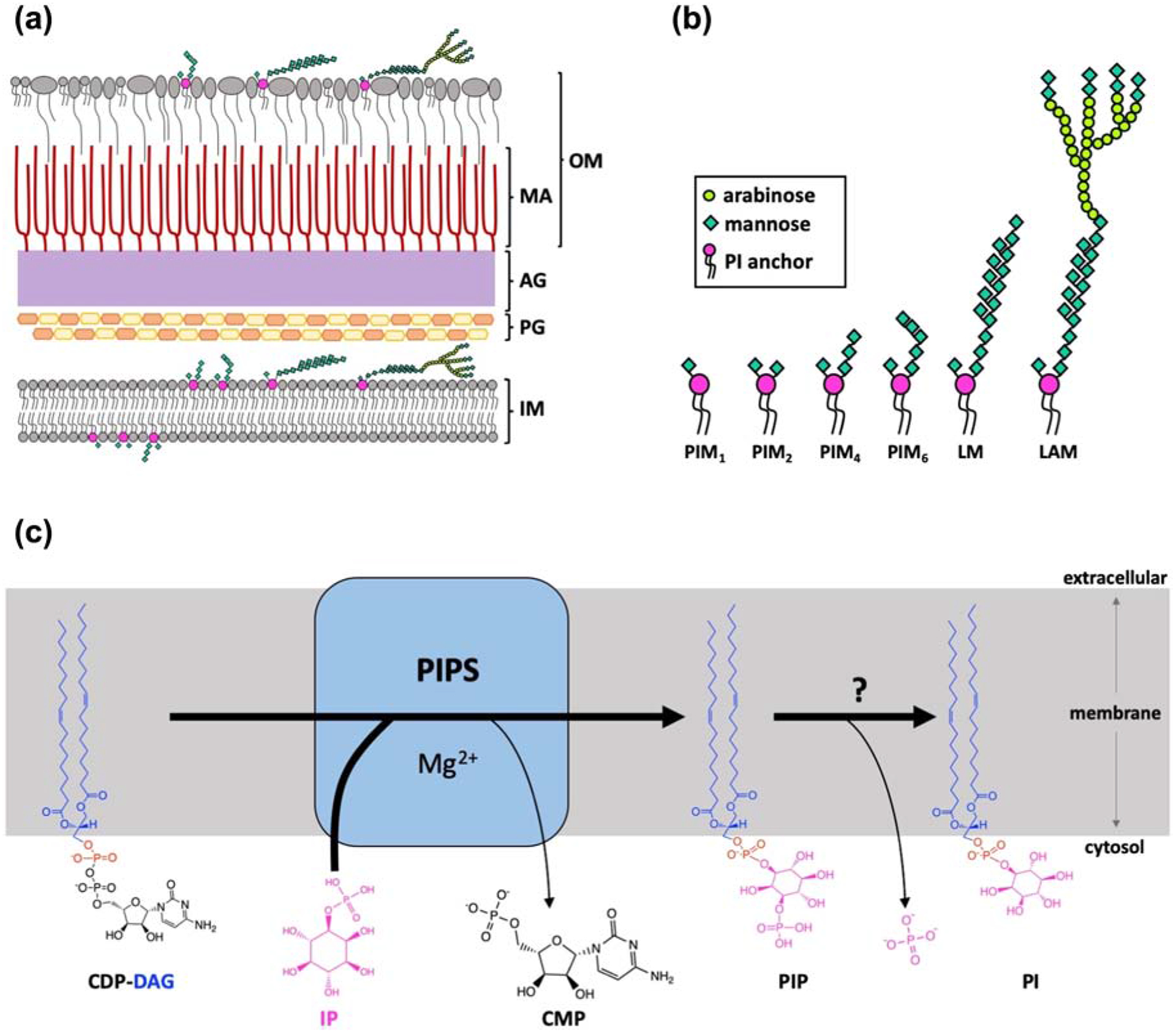

Tuberculosis (TB) is a global health concern that is exacerbated by the emergence of drug resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative pathogen of the disease [1, 2]. As opposed to gram-negative or gram-positive bacteria, mycobacteria are classified as acid fast, as they exhibit low absorbance, but high retention of laboratory stains [3]. This staining pattern is due to the complex mycobacterial cell wall [3], which results in a waxy, impermeable barrier that is a hurdle for antibiotic development [4]. The cell wall of mycobacteria has an inner lipid bilayer, blanketed with a peptidoglycan mesh similar to gram-negative bacteria. However, in mycobacteria, this mesh is covalently linked to another layer consisting of arabinogalactan branched sugars, which are then covalently attached to mycolic acids, forming the inner leaflet of the outer membrane (Figure 1A). The outer leaflet is populated by an uncommon lipid array, including a variety of acyltrehaloses, phenolic glycolipid and phthiocerol dimycocerosate [5]. Mycobacteria also contain different glycolipid classes whose sugar chains are embedded throughout the cell wall. These include phosphatidylinositol mannosides (PIMs), lipomannans (LMs) and lipoarabinomannans (LAMs), which can act as virulence factors and modulators of the host immune system [6] (Figure 1A & B). For example, there is evidence that mannose-capped LAM and PIM6 (PI linked to six mannose moieties; Figure 1B) mediate binding to receptors on macrophages and dendritic cells, initializing phagocytosis, a key step in bacterial survival and establishment of latent infection [7, 8]. Many first-line anti-TB treatments inhibit enzymes that are involved in the synthesis of key elements of the complex cell wall. These include ethambutol, which targets the formation of arabinogalactan, and isoniazid, which acts by disrupting fatty acid elongation during the biosynthesis of mycolic acids [5, 9].

Figure 1 |. Characteristics of the mycobacterial cell wall and the biosynthetic role of the PIPS enzyme.

A) Illustration of the mycobacterial cell wall structure (IM, inner membrane; PG, peptidoglycan; AG, arabinogalactan; MA, mycolic acid; OM, outer membrane) showing the distribution of common PI-anchored lipids, illustrated with more detail in (B) (PIM, phosphatidylinositol mannosides; LM, lipomannan; LAM, lipoarabinomannan). C) PIPS catalyzes the reaction between CDP-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG), a lipidic substrate, and inositol-phosphate (IP), a water-soluble substrate, in the presence of a divalent cation (Mg2+) forming the lipid phosphatidylinositol-phosphate (PIP) and CMP. Panel A and B made with reference to [6, 29–31].

PIMs, LMs and LAMs share a common lipid anchor, phosphatidylinositol, which has been demonstrated to be of vital importance for growth and viability of mycobacteria [10] (Figure 1B). The key enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of phosphatidylinositol in mycobacteria is the CDP-alcohol phosphotransferase (CDP-AP) phosphatidylinositol-phosphate synthase (PIPS) [10]. Members of the CDP-AP enzyme family, including PIPS, catalyze common reactions, transferring a chemical moiety from a CDP-linked donor to an alcohol acceptor in the presence of a divalent cation, resulting in a phosphodiester-linked product. CDP-AP enzymes share an absolutely conserved eight amino acid signature motif (D1xxD2G1xxAR…G2xxxD3xxxD4) shown to be involved in cytidine-diphosphate and metal binding, as well as in catalysis per se [11–14]. PIPS catalyzes the reaction between CDP-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG) and inositol-phosphate (IP), yielding phosphatidylinositol-phosphate (PIP; Figure 1C), which is subsequently dephosphorylated by an as yet uncharacterized enzyme to produce PI. In prokaryotes, PI is unique to mycobacteria and few species of bacteria. In all eukaryotes, including humans, PI is instead synthesized directly from CDP-DAG and myo-inositol and the inositol-based substrates are not interchangeable [15]. In addition, using a conditional knockout, PIPS has been shown to be essential for the growth and viability of Mycobacterium smegmatis and is the major biosynthetic enzyme for PI production in mycobacteria [10, 15]. For these reasons, PIPS represents a promising target for the development of novel anti-TB drugs [16].

Structures of PIPS from Renibacterium salmoninarum (RsPIPS) with and without the bound CDP-diacylglycerol substrate have been previously reported [12], providing information on the overall architecture of the enzyme and a structural framework for identification of specific residues responsible for donor substrate specificity and catalysis in a homologous enzyme from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. However, RsPIPS exhibits very low catalytic activity impeding a direct enzymatic characterization of this protein. Furthermore, RsPIPS is evolutionary distant from the enzymes of Mycobacterium (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1), limiting the applicability of this model to future much needed drug-design efforts. From a crystallogenesis perspective, crystals of RsPIPS could only be obtained as genetically engineered fusions with the soluble cytidylyltransferase-like domain (CTD) from Af2299, a related CDP-AP enzyme, acting as a crystallization chaperone (AfCTD) [11, 12]. More recently, a structure of PgsA1, from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MtPgsA1; translated from the same gene as previously named MtPIPS) was published, showing a similar overall architecture and substrate binding as RsPIPS [14]. The solution of this structure allowed the authors to suggest a catalytic mechanism that is consistent with the universal mechanism previously proposed for members of the CDP-AP enzyme family [11]. However, no crystallographic complex with inositol-phosphate has been visualized thus far, limiting, to a certain extent, our structure-based understanding of PIPS function.

Here we present structures of a catalytically active PIPS from Mycobacterium kansasii (MkPIPS), in both the apo state and with evidence of IP and CDP binding. These structures allowed us to define and functionally validate the molecular basis of substrate specificity, setting the premise for future drug design efforts against this target. Moreover, from a protein engineering perspective, we successfully recapitulated the use of the AfCTD as a crystallization chaperone, showing potential of this tool for utilization in a more universal crystallization scheme.

Results

Structural genomics and crystal engineering of functionally validated constructs

To increase the likelihood of producing well-diffracting crystals of a mycobacterial PIPS, we used a multi-pronged approach. This included screening for optimal expression, purification and crystallization of PIPS orthologs from different mycobacterial species, fusion of a crystallization chaperone to the N-terminus of PIPS, and further mutagenesis and optimization of the crystallization conditions to improve diffraction qualities of crystals of the fusion protein. Previous engineering of fusion proteins yielded the structure of RsPIPS [12] and here we recapitulated and expanded this approach. PIPS from 12 mycobacterial species were cloned and genetically fused to AfCTD [11] (Supplementary Figure 2 C & D). The addition of AfCTD to mycobacterial PIPS increased protein expression in E. coli, allowing purification of proteins at appropriate levels for crystallization experiments (Supplementary Figure 2 B & D). Fusion proteins of PIPS from Mycobacterium abscessus and from Mycobacterium kansasii (MkPIPS) purified in detergent and reconstituted in lipidic cubic phase (LCP) yielded initial crystals using commercial screens (Supplementary Figure 3A & B). These crystals diffracted poorly and failed to improve despite extensive rounds of optimization at the protein purification and crystallization level. We hypothesized this might be due to flexibility in the fusion protein between PIPS and AfCTD, making formation of an ordered crystal lattice unfavorable. We thus undertook further rounds of mutagenesis-driven optimization of the expression construct, aimed at decreasing this flexibility.

To rigidify the AfCTD- MkPIPS interface, we focused our efforts on the PIPS TM2–3 loop and the linker region between AfCTD and the enzyme (Supplementary Figure 2C). This led to the design and generation of a considerable number of mutant constructs (Supplementary Table 2). Each mutant was expressed, purified and tested for crystallization, with and without the addition of the lipidic ligand CDP-DAG in the LCP mix. A phenylalanine in the TM2–3 loop region of Af2299 appeared to stabilize the inter-domain region of the AfCTD-RsPIPS fusion, suggesting we should focus our construct engineering crystal optimization efforts on the TM2–3 loop [11, 12]. This approach yielded improvements in diffraction. One construct in particular, with a serine substituted in the homologous position of the phenylalanine (MkPIPS-S79; Supplementary Figure 2E), lead to the best quality crystals (Supplementary Figure 3C & D). Other attempts to change the linker region did not seem to have beneficial effects and more drastic engineering approaches to replace the TM2–3 loop and JM helix with the corresponding residues from RsPIPS resulted in destabilization of the protein and increased aggregation (data not shown). This protein engineering approach ultimately led to the determination of MkPIPS structures in an apo state and in the presence of CDP and IP to 3.1 Å and 2.6 Å resolution, respectively.

Functional assessment of the MkPIPS fusion constructs used for crystallization was performed with radiolabelled IP [12], which revealed activity levels comparable to those previously reported for MtPIPS with and without the N-terminally fused AfCTD [12] (Supplementary Figure 4). Kinetic characterization (Table 2) of AfCTD-MkPIPS fusion (no mutations in respect to the native sequence) gave a KM for inositol-phosphate of 110 μM and a KM for CDP-DAG of 26 μM. AfCTD-MkPIPS-S79 (Supplementary Figure 2E) showed slightly higher KM values for both inositol-phosphate and CDP-DAG (292 μM and 92 μM respectively), though these values are comparable to the previously reported KM values for WT MtPIPS with no fusion (243 μM for inositol-phosphate and 60 μM for CDP-DAG) [12].

Table 2 |.

KM measurements of PIPS from mycobacteria.

| KM (μM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | MkPIPS-fusiona | MkPIPS-S79b | MtPIPS-fusionc | MtPIPSd |

| Inositol-1-Phosphate | 109.6 ± 4.4 | 291.9 ± 8.4 | 122.4 ± 12.3 | 242.6 ± 23.3 |

| CDP-DAG | 25.8 ± 0.9 | 91.6 ± 3.1 | 238.3 ± 35.9 | 60.4 ± 4.5 |

MkPIPS-fusion (AfCTD fusion with no additional mutations)

MkPIPS-S79 (AfCTD fusion used for crystallization—see Supplementary Figure 2E for detailed sequence).

MtPIPS-fusion (AfCTD fusion with no additional mutations), published data from [12].

MtPIPS (without AfCTD-fusion) published data from [12]. The error reported is the standard deviation.

Apo Structure of MkPIPS

AfCTD-MkPIPS-S79 fusion protein was crystallized in the presence of CDP-DAG, producing diffraction of sufficient quality to allow the determination of the structure to 3.1 Å resolution (Table 1). Though CDP-DAG was present in the LCP crystallization mixture of AfCTD-MkPIPS-S79, clear density consistent with CDP-DAG could not be observed in the resulting electron density maps. There was density in the CDP-DAG binding site, which was modeled as a citrate molecule, a component of the crystallization solution. For these crystals, there was also density in the putative IP binding site though no inositol-phosphate was added during the purification or crystallization. This density was not compatible with IP or any other ligand that seemed chemically reasonable from the crystallization solution. This density remained unmodeled since no convincing solution was reached. This structure is referred to as the “apo” structure as neither CDP-DAG or IP are bound.

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| Data Collection | MkPIPS-S79 | MkPIPS-S79 + CDP* + IP |

|---|---|---|

| Space group | P21 | P21 |

| Unit cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 78.338, 60.241, 85.377 | 78.089, 60.856, 85.417 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90.911, 90 | 90, 90.738, 90 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9791 | 0.97918 |

| AIMLESS | ||

| Resolution range | 49.1 – 2.25 (2.33 – 2.25) | 85.26 – 2.35 (2.43 – 2.35) |

| Total no. of reflections | 72278 (7110) | 230116 (21205) |

| No. of Unique Reflections | 37287 (3698) | 33570 (3216) |

| Redundancy | 1.9 (1.9) | 6.9 (6.6) |

| % Completeness | 98.61 (98.88) | 99.6 (97.1) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 4.93 (1.40) | 8.3 (0.6) |

| Rmerge | 0.1122 (0.6492) | 0.185 (3.126) |

| Rmeas | 0.1586 (0.9181) | 0.219 (3.713) |

| Rpim | 0.1122 (0.6492) | 0.116 (1.985) |

| Wilson B factor | 35.75 | 55.3 |

| CC1/2 | 0.97 (0.394) | 0.997 (0.370) |

| Resolution where I/σ(I) drops below 2.0 overall | 3.35 | 3.15 |

| Resolution where I/σ(I) drops below 2.0 (along h) | 2.32 | 2.44 |

| Resolution where I/σ(I) drops below 2.0 (along k) | 2.82 | 3.49 |

| Resolution where I/σ(I) drops below 2.0 (along l) | 2.94 | 2.71 |

| Resolution where CC1/2 drops below 0.5 overall | 3.09 | 2.61 |

| Resolution where CC1/2 drops below 0.5 (along h) | 2.60 | 2.35 |

| Resolution where CC1/2 | 2.85 | 3.28 |

| drops below 0.5 (along k) | ||

| Resolution where CC1/2 drops below 0.5 (along l) | 4.02 | 2.52 |

| STARANISO | ||

| Ellipsoidal resolution (Å) (direction) | 2.78 (0.999 a* + 0.048 b*) | 3.201 (0.999 b* + 0.053 c*) |

| 5.40 (0.524a* + 0.852c*) | 3.381 (b*) | |

| 1.97 (−0.974a* + 0.025b* + 0.225c*) | 2.142 (−0.825a* + 0.080b* + 0.559c*) | |

| Ellipsoidal resolution range (Å) | 49.22 – 1.967 (2.037 – 1.967) | 78.08 – 2.144 (2.221 – 2.144) |

| Total no. of reflections (ellipsoidal) | 71471 (290) | 51956 (138) |

| No. of Unique Reflections (ellipsoidal) | 37482 (183) | 26006 (69) |

| Redundancy (ellipsoidal) | 1.9 (1.6) | 2.0 (2.0) |

| % Completeness (ellipsoidal) | 66.00 (3.27) | 58.72 (1.57) |

| Mean I/σ(I) (ellipsoidal) | 6.23 (0.98) | 9.78 (1.73) |

| Rmerge | 0.1061 (0.64) | 0.07329 (0.4034) |

| Rmeas | 0.1501 (0.9051) | 0.1036 (0.5705) |

| Rpim | 0.1061 (0.64) | 0.07329 (0.4034) |

| Wilson B factor | 25.57 | 41.06 |

| CC1/2 | 0.989 (0.11) | 0.995 (0.594) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution | 49.22 – 1.967 (2.037 – 1.967) | 78.08 – 2.144 (2.221 – 2.144) |

| No. reflections used | 37478 (183) | 25994 (69) |

| Reflections used for Rfree | 1930 (11) | 1297 (3) |

| No. of non-hydrogen atoms | 5682 | 5322 |

| protein | 5119 | 5027 |

| ligands | 460 | 268 |

| solvent | 103 | 27 |

| Rwork | 0.2354 (0.4364) | 0.2252 (0.3076) |

| Rfree | 0.2770 (0.2853) | 0.2691 (0.5353) |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| Bond angles (Å) | 1.10 | 1.15 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Favored regions | 98.19 | 96.99 |

| Allowed regions | 1.81 | 3.01 |

| Outliers | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Clashscore | 9.11 | 7.70 |

| Average B-factor | 33.73 | 45.41 |

| protein | 33.26 | 44.97 |

| ligands | 38.56 | 54.22 |

| solvent | 35.78 | 39.30 |

CDP was included in the crystallization condition and CMP was modeled into the ligand density.

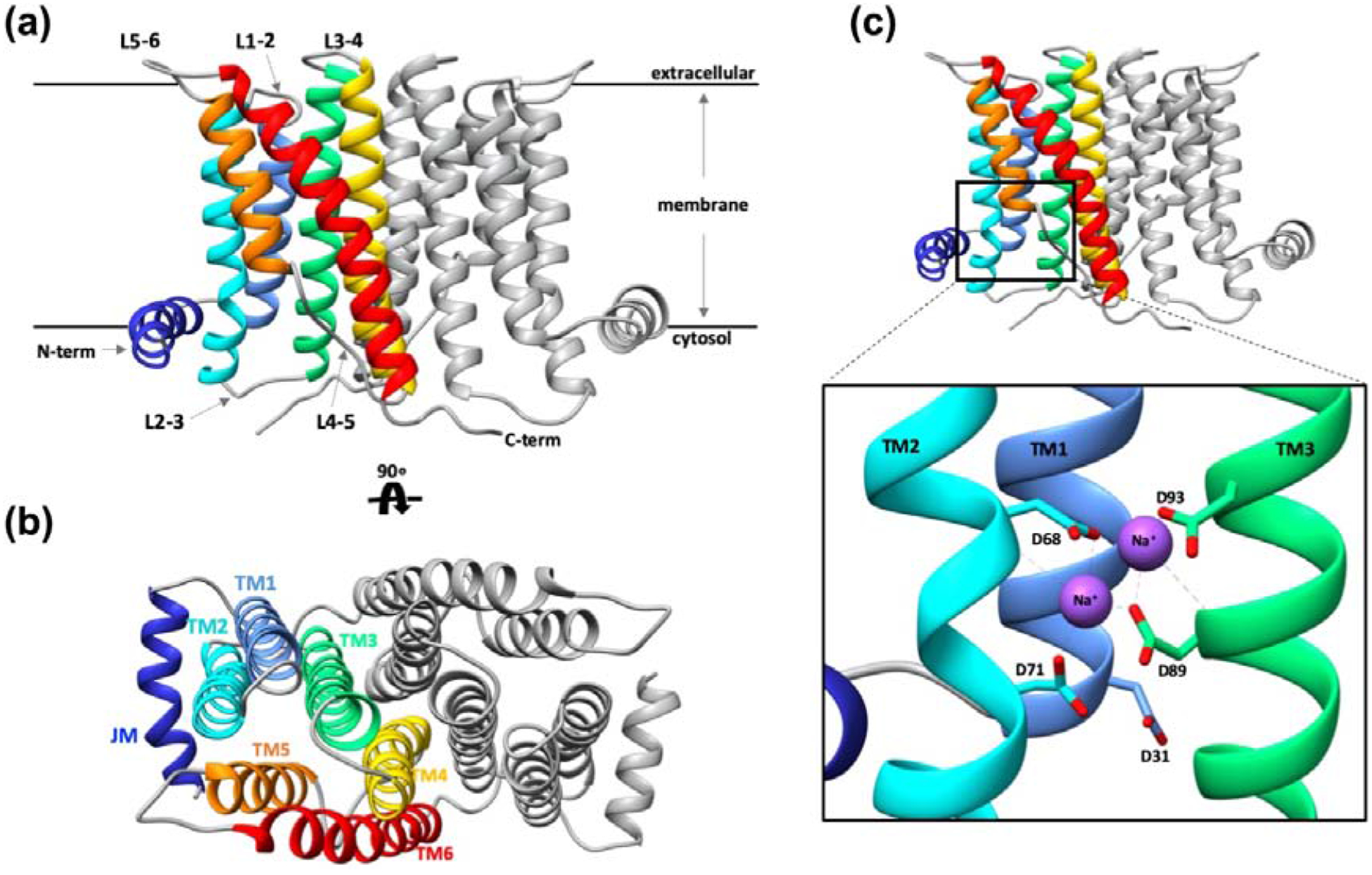

The structure of MkPIPS reveals an overall architecture similar to previously determined CDP-APs [11–14] (Figure 2A & B, Supplementary Table 3). The protein is a dimer, with each monomer consisting of an amphipathic juxtamembrane helix (JM) and six transmembrane (TM) helices (Figure 2B). There are three extracellular loops (L1–2, L3–4, and L5–6), of which L5–6 is notable for its extended conformation compared to all other CDP-AP enzymes for which structures are available (Figure 2A). There are also two cytosolic loops, L2–3 and L4–5 (Figure 2A), which both flank the substrate binding and catalytic sites. L2–3 was the target of the crystal engineering approach described above (Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Table 2). Unique to this structure, the C-terminus is in a conformation that appears to extend away from the six-helix bundle and form a sheet-like interaction with L2–3 of the second protomer (Figure 2A). This C-terminus is resolved to residue 210 of 232 and is disordered thereafter.

Figure 2 |. X-Ray crystallography structure of MkPIPS.

Overall architecture of the MkPIPS dimer with one protomer colored, (juxtamembrane helix, JM, in dark blue; transmembrane helix 1, TM1, in light blue; TM2 in cyan; TM3 in light green; TM4 in yellow; TM5 in orange; TM6 in red) and one protomer in grey presented in two views: A) Looking parallel to the plane of the membrane and B) rotated 90° looking perpendicular to the plane of the membrane. C-terminus, N-terminus, extracellular loops and cytosolic loops are labeled (L1–2 denotes loop between TM1 and TM2, etc.). C) Detailed view of the metal binding site containing four absolutely conserved aspartic acid residues (D68, D71, D89, D93) with bound sodium ions shown in purple. AfCTD used as a crystallization chaperone has been removed for clarity.

Consistent with what has been observed for other enzymes of the same family, the CDP-AP signature motif is divided between TM2 and TM3 towards the cytosolic side of the membrane, with the four absolutely conserved aspartic acid residues (D68, D71, D89, and D93) coordinating two Na+ ions (Figure 2C). Electron density peaks were observed compatible with coordinated metals. Sodium ions were modeled in the catalytic site based on abundance of NaCl in the crystallization solution, as well as distance and geometry with the aid of the CheckMyMetal server [17]. This basic organization of the MkPIPS active site looks similar to that of RsPIPS, but when the two structures are superimposed, there seems to be a significant difference. TM2 regions of MkPIPS and RsPIPS align more poorly than surrounding TM1 and TM3, especially when looking at the region directly surrounding the conserved aspartates (D68 and D71 in MkPIPS numbering; Supplementary Figure 6A & B). These changes in TM2 between MkPIPS and RsPIPS result in differences in the geometry of the active site (Supplementary Figure 6A & B). In fact, there is a characteristic kink in TM2 observed in all CDP-AP structures. In MkPIPS, Af2299 [11] and IPCT/DIPPS [13], this kink in TM2 is flanked by the two conserved aspartic acid residues, which help form the cytidine binding site and active site of the CDP-AP (Supplementary Figure 6C). In RsPIPS [12], however, this kink occurs above these two conserved aspartic acids (Supplementary Figure 6C), contributing to the aforementioned deviation in geometry observed when compared to MkPIPS (Supplementary Figure 6B).

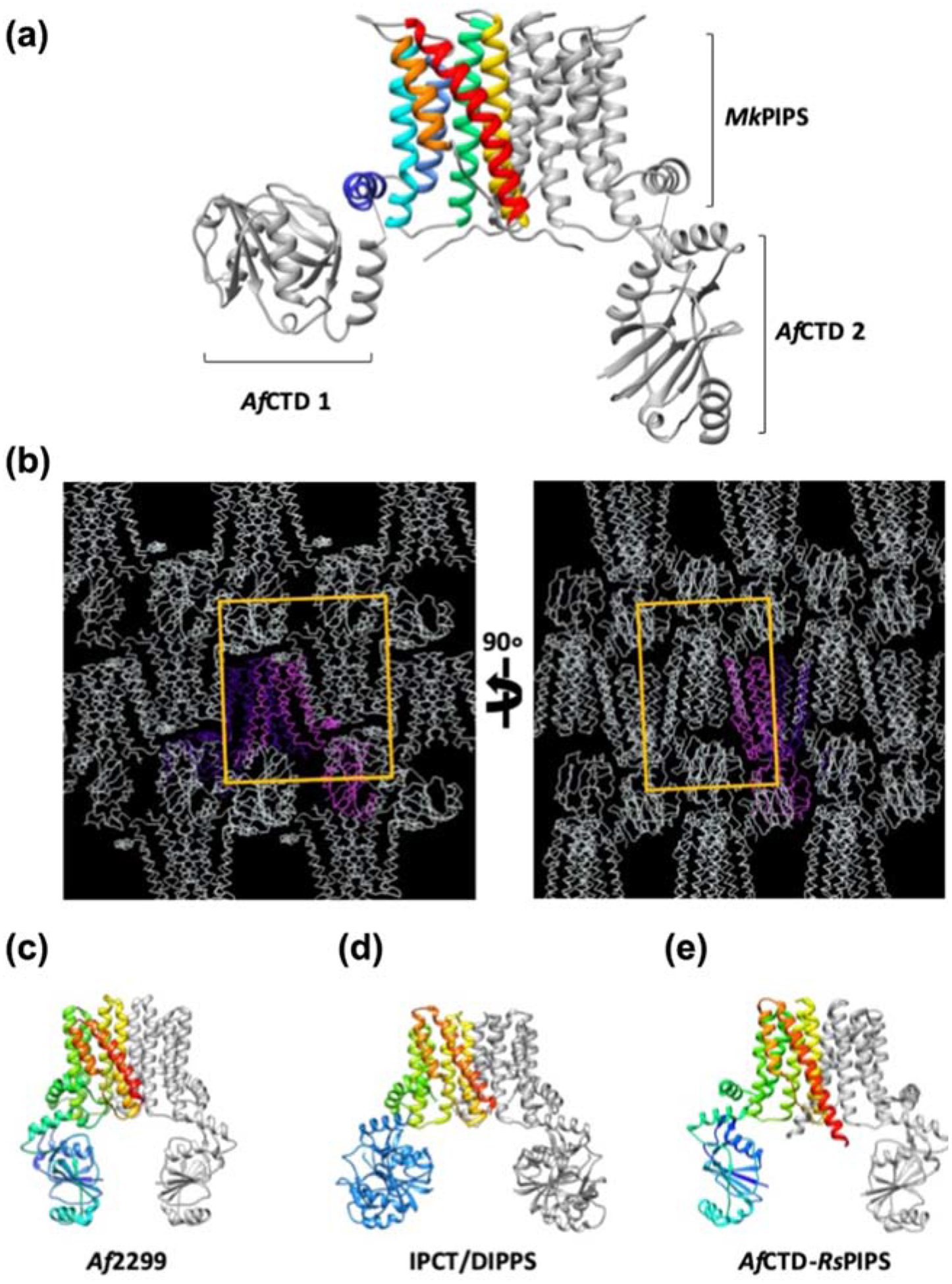

MkPIPS structure reveals unique organization of the crystallization chaperone

For previous CDP-AP enzymes which have been crystallized with soluble domains – whether engineered or as naturally-occurring – the domains have appeared as symmetric (Figure 3C, D and E). Crystal packing of AfCTD-MkPIPS-S79 revealed distinct layers of TM domains and cytosolic domains (Figure 3B), consistent with crystal packing of AfCTD-PIPS shown to occur previously [11–14], while the relative arrangement of soluble domains observed for MkPIPS is surprising. Indeed, in the structure of AfCTD-MkPIPS-S79, within each dimer, the AfCTD domain from each protomer crystallized in a completely different orientation (Figure 3A).

Figure 3 |. Novel AfCTD crystallization chaperone conformation.

(A) AfCTD-MkPIPS dimer is colored as in Figure 1 with the N-terminally fused AfCTDs in grey. The two AfCTDs (AfCTD 1 and AfCTD 2) in the MkPIPS fusion protein dimer adopt different conformations in the crystal lattice. (B) Crystal lattice of AfCTD-MkPIPS shown with one protomer in pink, the other protomer in purple, and symmetric lattice molecules in white with the unit cell illustrated by a yellow box. All other CDP-AP enzymes with a soluble domain (natural or engineered) crystallized with symmetric soluble domains: Af2299 (C; 4O6M) [11], IPCT/DIPPS (D; 4MND) [13], and AfCTD-RsPIPS fusion (E; 5D92) [12].

Substrate binding to MkPIPS

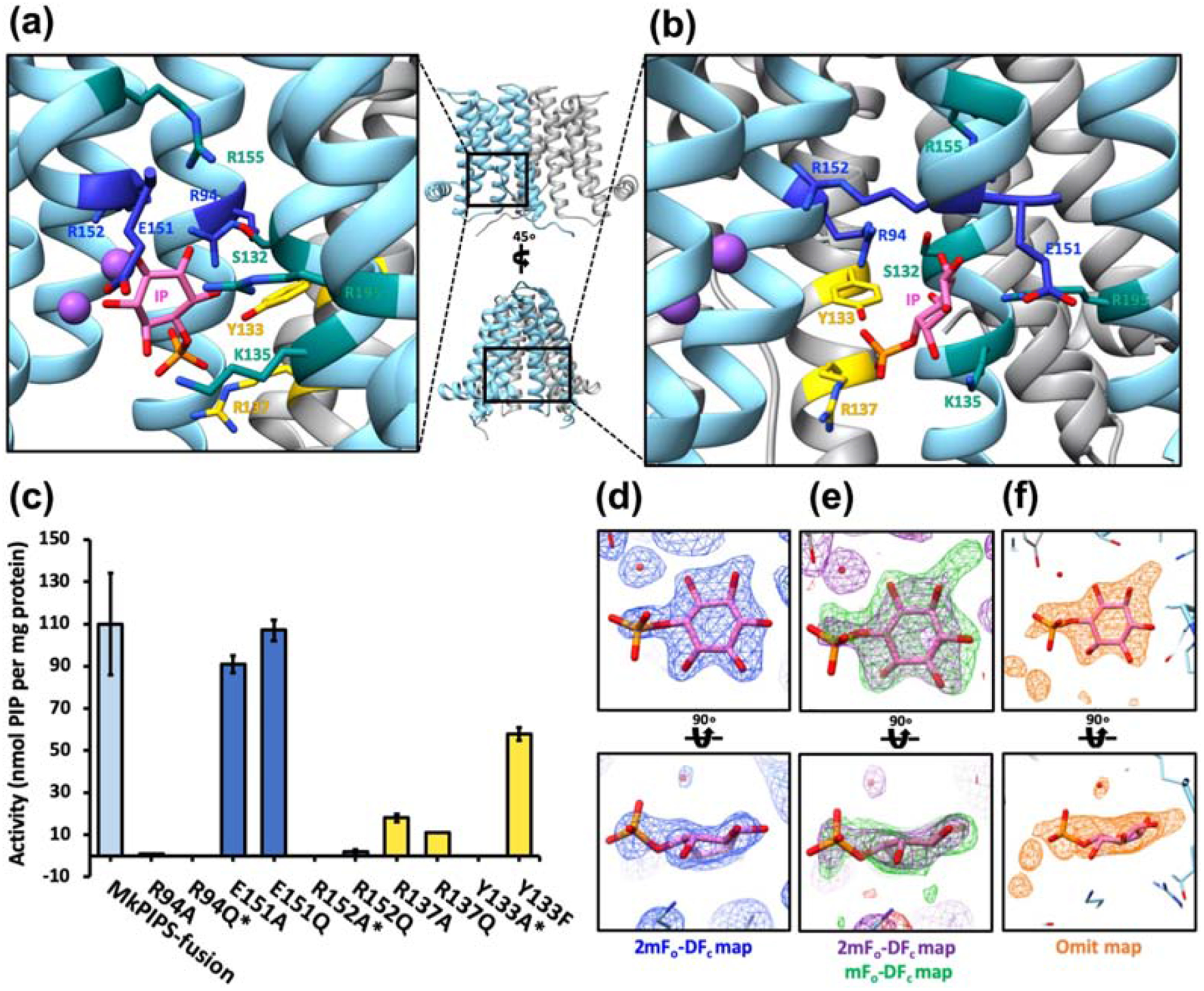

In a previous report we established that CDP-DAG must first be bound to PIPS for IP to efficiently bind, following an ordered bi-bi reaction mechanism, where both substrates must bind sequentially before the product is made [12]. Therefore, we first attempted to co-crystallize active or catalytically inactive (by mutagenesis) AfCTD-MkPIPS variants with both CDP-DAG and IP. However, these experiments did not show evidence of bound IP in the resulting structures. In order to trap the elusive acceptor substrate in the binding pocket, attempting to satisfy the binding requirements, while also preventing catalysis, we co-crystallized catalytically active AfCTD-MkPIPS-S79 with IP and soluble CDP. This approach resulted in a 2.6 Å resolution structure, showing evidence of both ligands bound to PIPS (Figure 4). Putative density for CDP was observed in one monomer and putative density for IP was observed in the opposite monomer (Supplementary Figure 10). Density consistent with the CDP was observed in the CDP-binding pocket of one monomer, but only one phosphate group could be accommodated, so the ligand was modeled as CMP (Supplementary Figure 8). The cytidine binding was consistent with previously observed CDP-DAG binding to RsPIPS [12], CDP/CMP binding to Af2299 [11], and CDP-DAG binding to MtPgsA1 [14].

Figure 4 |. Putative Inositol-1-phosphate (IP) binding to MkPIPS.

The X-Ray crystallography structure of MkPIPS (one protomer in light blue and the other in grey) with evidence of binding to IP and CDP was solved and details of the putative inositol-1-phosphate binding pocket are shown in A and B. Residues that have been previously characterized to play a role in IP binding are shown in teal. Additional putative IP binding residues are shown in blue (protomer 1) and yellow (protomer 2). C) Putative IP binding residues were mutated and tested for activity using a functional assay in which activity is measured by the amount of myo-[14C]inositol-1-phosphate incorporated into the lipid phase. MkPIPS-fusion denotes the recombinant MkPIPS fused N-terminally to AfCTD with no additional mutations (as introduced for crystallization; light blue on bar graph). Single point mutations are indicated. *No detectable activity by this assay. Electron density of putative IP ligand when refined with IP (2mFo-DFc in blue mesh at 1.0 σ; D), when refined without ligand (2mFo-DFc in purple mesh at 1.0 σ, mFo-DFc in green mesh at 2.3 σ; E) and the omit map (orange mesh at 4.5 σ; F).

Previously, residue M69 in MtPIPS was functionally characterized showing loss of function when mutated to a tryptophan and gain of function when mutated to an alanine [12]. We hypothesized that this residue affects CDP-DAG binding efficiency. We tested mutants of MkPIPS, attempting to recapitulate the behavior of MtPIPS, as well as mutants of RsPIPS to see if we could produce a gain-of-function phenotype. We were able to recapitulate the loss of function in MkPIPS when mutating M69 to a bulky tryptophan residue, however we did not observe gain of function in MkPIPS or RsPIPS (Supplementary Figure 9).

Density in the proposed IP binding pocket was modeled as many different potential ligands, and IP seemed to be most consistent with the density considering the components of purification and the crystallization conditions (Figure 4D, E & F). IP is seemingly bound in a polar cytosol-facing pocket surrounded by TM3, TM4, TM5 and TM6 as well as TM4 from the opposite protomer, indicated as TM4’ (Figure 4A and B). Residues previously hypothesized to be involved in IP binding (R155, R195, K135, S1320) [12], all seem to have a role coordinating what we expect to be the inositol sugar group, while previously uncharacterized residues R94, Y133’ and R137’ appear spatially positioned for coordination of the putative phosphate group. Residue E151 on TM5 flanks the top edge of the IP binding pocket, while residue R152 extends from TM5, arching over the pocket. R152 does not seem to play an obvious role in IP binding in the structure, though it has been identified as absolutely conserved in CDP-AP enzymes that utilize inositol-phosphate as the acceptor substrate (along with R94) [11]. R152 is also structurally conserved in all the CDP-AP structures determined [11–14].

To gain a better understanding of the functional role of the residues that coordinate IP in the binding pocket, we designed and generated structure-informed mutants and tested them in a previously established activity assay [12]. Of residues that appear to coordinate the phosphate group of the putative IP, mutants R94A, R94Q and Y133A lead to complete loss of function, R137A and R137Q showed dramatically reduced function, while Y133F has slightly reduced function. R152A and R152Q completely lose function, while E151A and E151Q mutants retain activity comparable to the native enzyme (Figure 4C).

Discussion

PIPS catalyzes the reaction that yields phosphatidylinositol-phosphate, precursor to phosphatidylinositol, which is the essential lipid anchor to the membrane for several components of the mycobacterial cell wall. As a member of the CDP-AP enzyme family, PIPS shares a conserved CDP binding site and geometry of the active site. Interest in its capacity as a drug target has focused on competitive inhibition targeting the binding site of its unique inositol-phosphate substrate [16]. Structures of RsPIPS [12] characterized CDP-DAG binding and identified a putative inositol-phosphate binding pocket. More recently, structures of M. tuberculosis PgsA1 (MtPgsA1) [14], have revealed a similar mode of CDP-DAG binding to a mycobacterial phosphatidylinositol-phosphate synthase and allowed proposal of a catalytic mechanism consistent with those previously proposed for other CDP-AP enzymes [11]. However, to date, all PIPS structures reported have failed to show any evidence of binding of the acceptor substrate inositol-phosphate. Ultimately, a multi-pronged approach consisting of structural genomics, use of crystallization chaperones, and crystal engineering at the protein level has led to the determination of structures of MkPIPS, one of which shows putative inositol-phosphate binding.

Fusion of PIPS to the AfCTD crystallization chaperone was instrumental in improving protein yields and promoting crystal formation, allowing structure determination. Indeed, we observed a universal and dramatic boost in expression of mycobacterial PIPS when these were engineered as fusions with AfCTD (Supplementary Figure 2B and D). The observation that adding an N-terminal fusion domain already selected based on its good expression profile (in E. coli) increases levels of target proteins is not surprising and somewhat anecdotal, however does make AfCTD an appealing crystallization chaperone for future, and possibly more general, use.

Functional characterization of the MkPIPS constructs utilized for crystallization show similar activity and substrate binding affinities to MtPIPS (Table 2, Supplementary Figure 4). The similarity in kinetics between MkPIPS and MtPIPS validated our approach, and suggests that conclusions drawn from MkPIPS fusion structures, can directly inform understanding of native MtPIPS.

The lack of symmetry observed in the orientation of the AfCTD soluble domains in the crystals (Figure 3A) was unexpected, since the crystal engineering approach was intended to stabilize, and hence rigidify the interface between the soluble AfCTD and PIPS. It seems that our efforts to optimize crystallization actually introduced more flexibility and freedom between domains, resulting in the unique arrangement observed. The assertion that the AfCTD domain is flexible in solution is supported by higher average B-factors of the AfCTD compared to the PIPS component in the structures presented. Based on our structures, we hypothesized that the C-terminus may have contributed to the inability of MkPIPS to form the stable interface with AfCTD that was previously observed in a PIPS fusion protein [12]. However, truncations of the presumably unstructured C-terminus (such as in MkPIPS-Δ24C-D93N) still crystallized in the same way, with an asymmetric arrangement of AfCTD domains, and did not lead to an improvement in diffraction. Ultimately, the benefits to protein expression and the fact that the AfCTD-PIPS fusion still crystallized in this novel, asymmetrical conformation allows us to propose the use of the AfCTD as a general expression level enhancer and versatile crystallization chaperone, with potential applicability beyond the CDP-AP family of enzymes.

The structure presented here in Figure 2 showed no binding of CDP-DAG, though this ligand was present in the crystallization condition. This could be due to CDP-DAG being available in insufficient amounts to show occupancy. We designated this structure as “apo” as it showed no binding of its known substrates. However, density consistent with citrate was observed in the CDP-DAG binding site and density which we could not assign was observed in the inositol-phosphate binding pocket.

One of the lingering questions in light of the observed structural similarities is why RsPIPS and MkPIPS differ so substantially in levels of activity when they share similar overall architecture and seem to share identity in regions important for substrate binding and catalysis. A comparison of the structures of RsPIPS and MkPIPS revealed first a difference in geometry of the active site (Supplementary Figure 6A and B). This difference in structure may contribute to the reduced activity of RsPIPS, an assertion strengthened by the fact that RsPIPS appears as a structural outlier in the spatial arrangement of the absolutely conserved aspartic acid residues relative to the characteristic bend of TM2 (Supplementary Figure 6C).

The MkPIPS structure presented here has revealed details of putative substrate binding to PIPS in the context of an active enzyme relevant to a pathogenic Mycobacterium. Co-crystallization of CDP and IP with MkPIPS was performed using a construct expressing an active enzyme (MkPIPS-S79). Co-crystallization with the soluble CDP, lacking the DAG lipid component, seemingly allowed for high enough occupancy of the nucleotide binding site to in turn allow IP binding without generating the catalytic product. Coordination of the cytidine group in this model was consistent with previously observed CDP-conjugate substrates binding to CDP-AP enzymes, but the β-phosphate group was not resolved (Supplementary Figure 8). The recent MtPgsA1 structure bound to CDP-DAG presented by Grave, et al. [14] suggests that CDP-DAG binding induces a slight conformational shift centered around the TM2 helical bend. This is not observed in the structure of AfCTD-MkPIPS-S79 bound to soluble CDP, likely due to the soluble substrate used in crystallization lacking lipid tails. The coordination of the cytidine group, however, is incredibly close between the two structures (Supplementary Figure 12). Furthermore, both MkPIPS structures presented here most closely align to architectures of MtPgsA1 without bound CDP-DAG (PDB ID: 6H53 and PDB ID: 6H5A; Supplementary Table 3).

The structure of MkPIPS-S79 with evidence of IP and CDP binding revealed density for different substrates in each protomer of the dimer (Supplementary Figure 10). This could be consistent with some cooperativity of binding between the protomers of the dimer. Though there are no explicit functional data to support this, we have previously shown that the presence of CDP-DAG increases IP binding [12], so it is possible that CDP-DAG binding could have an allosteric effect that promotes IP binding in the adjacent protomer. This has not been previously observed, nor hypothesized, for PIPS or members of the CDP-AP family, however it is important to note that MtPgsA1 also showed different substrate occupancy between protomers of the same structure (PDB ID: 6H5A) as well as different metal coordination in different protomers (“tight” and “relaxed” states) despite having CDP-DAG bound in both ligand sites (PDB ID: 6H59) [14]. The structure of MkPIPS putatively bound to CDP and IP has revealed a plausible substrate orientation given the previously proposed enzyme mechanism. Grave, et al. predict two binding modes for IP to MtPgsA1 based on computational docking, with one being more favorable [14]. Our model of putative IP binding to MkPIPS is more consistent with the described “binding mode #2” with the phosphate of IP closer to the SO4 (2) binding site, although the phosphate of IP does not directly align with this sulfate binding position, presumably as the sugar group might affect the final binding mode. Instead, the IP appears to bind between the two sulfate binding sites (PDB ID: 6H59; Supplementary Figure 11) described by Grave et al., very similar to the citrate binding mode (PDB ID: 6H5A; Supplementary Figure 11).

More of the MtPgsA1 C-terminus was resolved in the Mn-citrate bound structure than in the MkPIPS structures presented here and, the C-terminus of MtPgsA1 appears to occlude the CDP-DAG binding site (PDB ID: 6H5A, chain A). However, there is no direct evidence that this C-terminus has any role in function or substrate binding. In fact, our C-terminal truncated construct (AfCTD-MkPIPS-Δ24C) was active at the same levels as other AfCTD-MkPIPS fusion constructs (Supplementary Figure 4). In the Mn-citrate bound MtPgsA1 (PDB ID: 6H5A), the JM helix shows a bend towards the membrane and appears to interact more with the catalytic pocket. The authors suggest this conformation is stabilized by the presence of Mn and citrate molecules, but whether these interactions might have a functional relevance remains to be determined [14].

Finally, we used previously established functional assays [12] combined with targeted mutations of MkPIPS based on the structure, to characterize residues important for IP binding. Our results (Figure 4A) seem to suggest that R94 and R137 are important for direct coordination of IP, while Y133 may have a role in inositol-phosphate binding as it contributes to the overall chemical environment of the binding pocket, or may also have a role as a structural residue, where the aromatic ring plays an important role at the dimer interface. E151A and E151Q mutants retain activity comparable to the native enzyme, suggesting that they are likely neither important for substrate binding nor catalysis. We believe the models presented here are consistent with the model of catalysis proposed by Sciara, et al. [11] and Grave, et al. [14].

The MkPIPS structural and functional data presented here, of which we determined using a crystal engineering approach with unanticipated results, add strength to previous studies on PIPS. We contribute further evidence toward understanding the spatial arrangement of substrates in the active site, including a putative binding mode for the elusive donor substrate inositol-phosphate to this enzyme, though there is objectively still much to be learned. This characterization of a mycobacterial PIPS enzyme contributes to a strong foundation for efforts of anti-tuberculosis drug development.

Methods

Target identification and cloning of PIPS from mycobacteria

PIPS from 12 mycobacterial species were identified and cloned from genomic DNA (provided by NYCOMPS/COMPPÅ) into a pET-based expression vector (pMCSG7) with an N-terminal decahistidine tag separated from the gene with a Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease cleavage site [18]. These were cloned using Gibson assembly [19], both in their “native” form (meaning without a fusion) and with the soluble domain from the Af2299 CDP-alcohol phosphotransferase enzyme (cytidylyltransferase-like domain; AfCTD; residues 1–135 of UniProt O27985) recombinantly fused at the N-terminus separated by a GSGS linker (Supplementary Figure 2). Three mutations were then introduced into each fusion construct in an attempt to replicate the minimal interface between the AfCTD and TM domains observed in the structure of RsPIPS [12]. These mutations were based on sequence alignment with Af2299 and RsPIPS and include 79F, 77L, 17L (numbering of MtPIPS). This was accomplished using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent). The Uniprot IDs and species of the sequences identified were as follows: 1: P9WPG6, Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv; 2: A0A1M8UW79, Mycobacterium abscessus L984; 3: B2HM76, Mycobacterium marinum (strain ATCC BAA-535 / M); 4: A0A202FYW3, Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis; 5: A0A0J6YQ88, Mycobacerium chubuense; 6: A4TD07, Mycobacterium gilvum; 7: X8CIT8, Mycobacterium intracellulare; 8: X7Y109, Mycobacerium kansasii; 9: A0A024QPA5, Mycobacterium neoaurum; 10: A1T870, Mycobacterium vanbaalenii; 11: S4ZCZ8, Mycobacterium yongonense; 12: A0A0H3MFZ3, Mycobacterium bovis strain AF.

Expression and purification of mycobacterial PIPS

To express the target protein, BL21 (DE3) PLysS E. coli were transformed with the PIPS target construct in pMCSG7 expression vector. These transformants were used to inoculate a starter culture (2xYT containing 100 μg/ml Ampicillin and 35 μg/ml Chloramphenicol). Starter cultures were grown overnight at 37°C. The next day, 2xYT containing 100 μg/ml Ampicillin and 35 μg/ml Chloramphenicol was inoculated with 8 ml of starter culture per 800 mL. Cultures were grown to an OD600 between 0.8 and 1.0. Cultures were induced at room temperature by adding a final concentration of 200 μM IPTG and incubated overnight at 22°C. In the morning cultures were harvested at 4°C and 4000g.

Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgSO4, RNase, DNase, PMSF, Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 1mM TCEP) and lysed by pressure using an Avestin Emulsiflex C3. n-Dodecyl-ß-D-Maltopyranoside (DDM) was added to lysed samples to a final concentration of 1% to solubilize and extract the target proteins from the membrane. Solubilization was carried out for 1.5 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation. Samples were then spun at 134,000g at 4°C for 30 minutes to separate the insoluble fraction. The supernatant was added to Ni-NTA resin, which had been pre-equilibrated with buffer containing 20mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl and 0.1% DDM. Imidazole was added to a final concentration of 40mM to reduce non-specific binding to the nickel resin. Samples were incubated for 1–2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation. The resin was washed with 10 column volumes (C.V.) of wash buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 60 mM Imidazole, 0.1% DDM) and eluted with 3–4 C.V. of elution buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 300 mM Imidazole, 0.05 % DDM). His tagged SuperTEV protease [20] was added to the samples to remove the His tag from PIPS and the samples were then dialyzed overnight against buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl and 0.05% DDM to remove Imidazole. Subsequently, the samples were added to fresh pre-equilibrated Ni-NTA resin and incubated for 30 minutes to 1 hour at 4°C with gentle agitation or rotation. The flow through containing the cleaved target protein was collected for analysis by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) or for use in crystallization experiments.

Crystallization

Proteins purified in large scale were used for crystallization either without SEC analysis to prevent further delipidation of the proteins. After purification, proteins were concentrated to between 10 and 60 mg/ml using a centrifugal concentrator with a 100 kDa cutoff (Amicon) at 10,000 x g at 4°C. The concentrated protein sample was centrifuged at 16,100 x g at 4°C to clear any insoluble aggregates. For lipidic cubic phase crystallization, the protein was then mixed with monoolein (Sigma) with or without CDP-DAG additive lipid in a 1:1.5 protein to lipid ratio (w/w). For crystals grown in the presence of lipid CDP-DAG (Avanti), CDP-DAG dissolved in chloroform was added to monoolein to a final concentration of 2–3% (w/w). Chloroform was evaporated off the lipid mixture under a stream of inert argon gas and the lipid mixture was dried overnight using a vacuum desiccator. Using the LCP Mosquito (TTP Labtech) 80 nl of protein-lipid mix was deposited on a glass LCP plate, covered with 750 nl of precipitant solution (from a commercial screen or in-house screen) and sandwiched with a glass coverslip. Commercial screens used include MemGold, MemGold II, MemMeso, and Wizard Cubic LCP from Molecular Dimensions, as well as JCSG+ and NeXtal CubicPhase II from Qiagen. Crystals usually appeared after 2–3 days, but plates were stored at 22°C until crystals were at optimal size and quality, generally 3–4 weeks. When ready to freeze and ship to the synchrotron, a tungsten carbide glass-cutter (Hampton Research) was used to cut open the glass cover slip and crystals were harvested using 35–100 μm MicroLoops (MiTeGen). Crystals were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen without the use of additional cryoprotectant for the collection of X-Ray diffraction data.

Optimization procedures described in detail in the next sections yielded well-diffracting crystals of MkPIPS-S79 (Supplementary Figure 2) used to solve the apo structure presented in this paper. These crystals were grown in the following precipitant condition: 100 mM Sodium citrate, pH 6, 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 22% PEG 400. Concentrated protein was mixed with monoolein doped with 2% CDP-DAG.

Optimization of crystals

Optimization screens were designed by varying concentrations of components from the initial crystallization condition. Generally, pH and PEG concentration were increased and decreased around the initial condition in a 96 well array. Generally, repeats of these screens would be made with varying salt concentrations as well. Other optimization strategies were also used, such as varying the identity of the PEG or salt counter ion. Optimization screens were designed using the Dragonfly Designer software and made using the Dragonfly liquid handling robot (TTP Labtech). Crystal optimization was performed iteratively, reassessing the optimization strategy depending on the quality of crystallization and diffraction of such crystals from any given screen.

Design and production of mutants for crystal optimization

Mutants to stabilize the PIPS-AfCTD interface were designed using homology models based on the RsPIPS structure. It was observed from the RsPIPS structure that a key phenylalanine residue in the loop between TM2 and TM3 (F77 in RsPIPS numbering) made contacts essential for stable interface formation [12]. We recapitulated this in early crystallization trials by mutating the homologous residue in different mycobacterial PIPS to phenylalanine along with two key leucine residues [12]. In later optimization on the PIPS with the best diffracting crystals (MkPIPS), this residue and surrounding residues within the TM2-TM3 loop region, which were hypothesized to have an effect on the formation of the AfCTD-PIPS interface were mutated to improve diffraction. The linker length between AfCTD and MkPIPS was also varied in an attempt to stabilize the interface, a factor that also seemed to effect resolution in RsPIPS [12].

After having determined the first MkPIPS structure it was noted that the long C-terminus seemed to be interfering with the formation of the previously observed PIPS-AfCTD interface. Based on this, we made different C-terminal truncations, including AfCTD-MkPIPS-Δ30C, AfCTD-MkPIPS-Δ24C, and AfCTD-MkPIPS-Δ21C. All truncations were made using site directed mutagenesis to introduce a stop codon after the indicated residue (202 for Δ30C, 208 for Δ24C, and 211 for Δ21C). See Supplementary Table 2 for a complete list of MkPIPS mutants made in the optimization phase.

All point mutants were generated using the site directed mutagenesis Quick Change Lightening Kit (Agilent) and transformed into XL10 Gold Ultracompetent E. coli cells (Agilent). Variations of the linker region were cloned using Gibson Assembly (in house enzyme mix) [21] with just one amplicon with overhang regions containing the altered linker. Mutations, deletions and insertions were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Co-crystallization of MkPIPS with substrates

Purified protein was concentrated to between 30 and 35 mg/ml using a centrifugal concentrator (Millipore) with a 100 kDa MWCO. LCP mix was prepared with monoolein (Sigma) at a 1:1.5 protein to lipid ratio. A Mosquito LCP (TTP Labtech) was used to dispense a volume of 80 nl of LCP mixture onto a 96-well glass plate, which was covered with 750 nl of precipitant solution and sealed with a glass cover slip. Initial crystals appeared within 3 days, and were grown to optimal conditions up to 1 month in the following conditions: 100 mM NaCl, 100 mM Sodium Citrate, pH 6.1, 40 mM MgCl2, 29% PEG 400, 500 uM L-myo-inositol-1-phosphate (prepared in house at ITQB from glucose by coupling hexokinase from Thermoproteus tenax and L-myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus as described previously [12]), 2.5 mM CDP (Sigma) (MkPIPS-S79 bound to CDP and IP).

Data collection and structure determination of MkPIPS-S79

All data were collected at NE-CAT beamline 24-ID-E at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory (Lemont, IL, USA). For the initial MkPIPS-F79S structure, data were indexed, integrated and scaled with XDS [22] and AIMLESS [23]. Data were phased with molecular replacement, using a strategy to search separately for two copies of the AfCTD soluble domain (PDB ID: 4O6M, residues 1–134) and one copy of the TM dimer from RsPIPS (PDB ID: 5D91, residues 8–205) using PHASER [24]. Density modification, including solvent flattening, histogram matching and non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging, was performed using PARROT [25]. The model was completed in Coot [26] with aid of the CheckMyMetal server [17].

Diffraction appeared anisotropic, so in an attempt to improve map density, the STARANISO server developed by Global Phasing Ltd [27] was used to apply an anisotropic correction to the scaled data (without a resolution cutoff) and initial structures were refined against these corrected data (Supplementary Figure 5). Using a global I/σ(I) average to define the resolution cutoff produces spherical cutoffs for data in reciprocal space. For data that are anisotropic, this can exclude good quality reflections and include weak reflections. STARANISO applies a resolution cutoff based on local I/σ(I) averages, then performs Bayesian estimation of structure amplitudes followed by the application of an anisotropic correction factor to the data. STARANISO produced a best-resolution limit of 1.97 Å and a worst-resolution limit of 5.4 Å using a I/σ(I) cutoff of 1.2. Multiple rounds of model building in Coot and refinement with PHENIX [28] were carried out to a final Rwork/Rfree of 0.2339/0.2760. Complete data collection and refinement statistics can be found in Table 1.

Data collection and structure determination of MkPIPS-S79 crystallized in the presence of CDP and IP

All data were collected at NE-CAT beamline 24-ID-E at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory (Lemont, IL, USA). For the structure of MkPIPS-F79S bound to CDP and IP, data were indexed, integrated and scaled with XDS [22] and AIMLESS [23]. Data were phased by molecular replacement strategy utilizing the initial MkPIPS-S79 dimer structure as a search model using PHASER [24]. Density modification, including solvent flattening, histogram matching and non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging, was performed using PARROT [25]. The model was completed in Coot [26] with the aid of the CheckMyMetal server [17].

Diffraction was observed to be anisotropic, so in an attempt to improve map density, the STARANISO server developed by Global Phasing Ltd [27] was used to apply an anisotropic correction to the scaled data (without a resolution cutoff) and initial structures were refined against these corrected data. STARANISO produced a best-resolution limit of 2.14 Å and a worst-resolution limit of 3.38 Å using a I/σ(I) cutoff of 1.2. Multiple rounds of model building in Coot and refinement with PHENIX [28] were carried out to a final Rwork/Rfree of 0.2262/0.2718. Complete data collection and refinement statistics can be found in Table 1.

Functional characterization of MkPIPS mutants

MkPIPS variants were tested for activity using membrane isolates from E. coli expressing recombinant MkPIPS constructs using an established functional assay [12]. Briefly, protein in membranes was added to a reaction mixture containing radiolabeled L-myo-[14C]inositol-1-phosphate, L-myo-inositol-1-phosphate with no labeling, and CDP-dioleoylglycerol (CDP-DAG). The reaction was incubated at 37 °C and stopped after 1 hour. The aqueous and organic phases of the reaction were separated, and the radiolabeled enzymatic product (phosphatidylinositol-phosphate) in the organic layer was quantified using scintillation counting. The KM of MkPIPS for IP and CDP-DAG was determined as previously described for MtPIPS [12], using the same functional assay, while varying radiolabeled L-myo-[14C]inositol-1-phosphate concentration (to calculate KM of MkPIPS for IP) or CDP-DAG concentration (to calculate KM of MkPIPS for CDP-DAG) and stopping the reactions at different time points in a series.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Previous PIPS structures have not captured a complete view of substrate binding.

We present structures of catalytically active PIPS from Mycobacterium kansasii.

One structure of MkPIPS presented shows evidence of substrate binding.

Functional assays measured effect of key residue mutations on PIPS activity.

These structures add to the current knowledge of PIPS and its enzyme family.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Tomasek, Brian Kloss, Larry Shapiro and Leora Hamberger for their helpful contributions. This work was funded by NIH grants R21 AI119672, R35 GM132120 and R01 GM111980 to F.M and in part by project PTDC/BIA-BQM/31031/2017 (Lisboa-01-0145-FEDER-031031) from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal. This work also used the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team (NE-CAT) beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), which are funded by NIGMS from the NIH (P30 GM124165). The Pilatus 6M detector on 24-ID-C is funded by NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10 RR029205) and the Eiger 16M detector on 24-ID-E beamline is funded by a NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10 OD021527). APS is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated by Argonne National Laboratory with U.S. DOE support under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Some of the initial cloning and small-scale expression tests were performed at the Center for Membrane Protein Production and Analysis (COMPPAÅ; P41 GM116799 to Wayne Hendrickson). We dedicate this work to the memory of our colleague and friend Kanagalaghatta Rajashankar (“Raj”), who recently left us prematurely.

Abbreviations

- CDP

cytidine diphosphate

- CDP-AP

CDP-alcohol phosphotransferase

- CDP-DAG

CDP-diacylglycerol

- CMP

cytidine monophosphate

- CTD

cytidylyltransferase-like domain

- IP

inositol-phosphate

- LAM

lipoarabinomannan

- LCP

lipidic cubic phase

- LM

lipomannan

- PI

phosphatidylinositol

- PIM

phosphatidylinositol mannoside

- PIPS

phosphatidylinositol-phosphate synthase

- TB

tuberculosis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession codes and deposition

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes 6WM5 (apo) and 6WMV (with substrate binding).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no financial conflict of interest.

References:

- [1].Fogel N Tuberculosis: a disease without boundaries. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2015;95:527–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Poce G, Biava M. Overcoming drug resistance for tuberculosis. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:1735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Vilcheze C, Kremer L. Acid-Fast Positive and Acid-Fast Negative Mycobacterium tuberculosis: The Koch Paradox. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Favrot L, Ronning DR. Targeting the mycobacterial envelope for tuberculosis drug development. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012;10:1023–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jackson M The mycobacterial cell envelope-lipids. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Angala SK, Belardinelli JM, Huc-Claustre E, Wheat WH, Jackson M. The cell envelope glycoconjugates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;49:361–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Driessen NN, Ummels R, Maaskant JJ, Gurcha SS, Besra GS, Ainge GD, et al. Role of phosphatidylinositol mannosides in the interaction between mycobacteria and DC-SIGN. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4538–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vergne I, Gilleron M, Nigou J. Manipulation of the endocytic pathway and phagocyte functions by Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoarabinomannan. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Goude R, Amin AG, Chatterjee D, Parish T. The arabinosyltransferase EmbC is inhibited by ethambutol in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4138–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jackson M, Crick DC, Brennan PJ. Phosphatidylinositol is an essential phospholipid of mycobacteria. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30092–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sciara G, Clarke OB, Tomasek D, Kloss B, Tabuso S, Byfield R, et al. Structural basis for catalysis in a CDP-alcohol phosphotransferase. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Clarke OB, Tomasek D, Jorge CD, Dufrisne MB, Kim M, Banerjee S, et al. Structural basis for phosphatidylinositol-phosphate biosynthesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nogly P, Gushchin I, Remeeva A, Esteves AM, Borges N, Ma P, et al. X-ray structure of a CDP-alcohol phosphatidyltransferase membrane enzyme and insights into its catalytic mechanism. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Grave K, Bennett MD, Hogbom M. Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis phosphatidylinositol phosphate synthase reveals mechanism of substrate binding and metal catalysis. Commun Biol. 2019;2:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Morii H, Ogawa M, Fukuda K, Taniguchi H, Koga Y. A revised biosynthetic pathway for phosphatidylinositol in Mycobacteria. J Biochem. 2010;148:593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Morii H, Okauchi T, Nomiya H, Ogawa M, Fukuda K, Taniguchi H. Studies of inositol 1-phosphate analogues as inhibitors of the phosphatidylinositol phosphate synthase in mycobacteria. J Biochem. 2013;153:257–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zheng H, Cooper DR, Porebski PJ, Shabalin IG, Handing KB, Minor W. CheckMyMetal: a macromolecular metal-binding validation tool. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2017;73:223–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cesaratto F, Burrone OR, Petris G. Tobacco Etch Virus protease: A shortcut across biotechnologies. J Biotechnol. 2016;231:239–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA 3rd, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Correnti CE, Gewe MM, Mehlin C, Bandaranayake AD, Johnsen WA, Rupert PB, et al. Screening, large-scale production and structure-based classification of cystine-dense peptides. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25:270–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gibson DG. Enzymatic assembly of overlapping DNA fragments. Methods Enzymol. 2011;498:349–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kabsch W. Integration, scaling, space-group assignment and post-refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:133–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Evans PR, Murshudov GN. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69:1204–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cowtan K Recent developments in classical density modification. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:470–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ian J Tickle CF, Keller Peter, Paciorek Wlodek, Shraff Andrew, Smart Oliver, Vonrhein Slements, Bricogne Gérard. STARANISO. Global Phasing Ltd.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Abrahams KA, Besra GS. Mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis: a multifaceted antibiotic target. Parasitology. 2018;145:116–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mishra AK, Driessen NN, Appelmelk BJ, Besra GS. Lipoarabinomannan and related glycoconjugates: structure, biogenesis and role in Mycobacterium tuberculosis physiology and host-pathogen interaction. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:1126–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kallenius G, Pawlowski A, Hamasur B, Svenson SB. Mycobacterial glycoconjugates as vaccine candidates against tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:456–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sievers F, Higgins DG. Clustal omega. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2014;48:3 13 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.