Abstract

Background

The 5-year survival for Black women with breast cancer in the United States is lower than Whites for stage-matched disease. Our past and ongoing work, and that of others, suggest that symptom incidence, cancer-related distress, and ineffective communication contribute to racial disparity in dose reduction and early therapy termination. While race is perhaps the most studied social determinant of health, it is clear that race alone does not account for all disparities.

Objectives

To present a study protocol of Black and White women prescribed breast cancer chemotherapy. The aims are to: 1)examine and compare chemotherapy received/prescribed over time and in total; 2a) examine and compare symptom incidence, distress, and management, and clinical encounter, including patient-centeredness of care and management experience over time; 2b) correlate symptom incidence, distress, and management experience to Aim 1; and 3) explore the effects of social determinants of health, including age, income, education, zip code, and lifetime stress exposure, on Aims 1, 2a, and 2b.

Methods

A longitudinal, repeated measures (up to 18 timepoints), comparative, mixed-methods design is employed with 179 White and 179 Black women from 10 sites in Western Pennsylvania and Northeast Ohio over the course of chemotherapy and for 2 years following completion of therapy.

Results

The study began in January 2018, with estimated complete data collection by late 2023.

Discussion

This study is among the first to explore the mechanistic process for racial disparity in dosage and delay across the breast cancer chemotherapy course. It will be an important contribution to the explanatory model for breast cancer treatment disparity and may advance potential mitigation strategies for racial survival disparity.

Keywords: breast neoplasms, healthcare disparities, symptom assessment, treatment adherence and compliance

Black women in the United States consistently have the lowest 5-year survival rate for breast cancer (BC) when compared with all other races for stage-matched disease despite adjustment for comorbidity, age, and insurance status (DeSantis et al., 2019). Biologic mechanisms of disease, comorbidity profiles, and late stage at diagnosis are implicated in BC survival disparity, but differences in treatment also play a role. Specifically, during BC chemotherapy, Black women are given a lower relative dose intensity, as well as more frequent delays, dose reductions, and earlier chemotherapy discontinuation, when compared with White women (Griggs et al., 2003; Knisely et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). The underlying reasons for these chemotherapy adherence disparities remain unclear.

The term adherence traditionally describes the extent to which one follows prescribed oral medication regimens and focuses on factors related to the patient’s role. In truth, adherence can refer to any form of medication regimen and is a shared responsibility between health professionals and the patient (Scott & McClure, 2010). Less than full adherence to prescribed BC chemotherapy is often initiated by the healthcare provider, as opposed to the patient, regardless of efforts to involve the patient in treatment decisions. While recent standardized guidelines have helped to equalize chemotherapy prescription across races (Warner et al., 2015), racial disparity in receiving prescribed dosing persists.

Symptom severity is an independent risk factor for chemotherapy completion (Wells et al., 2015). Symptom incidence and severity during BC chemotherapy are worse among Black women compared to White women, particularly pain (Rosenzweig & Wesmiller, 2016) and neuropathy (Bhatnagar et al., 2014). Additionally, cancer-related distress, and ineffective communication on the part of the patient (symptom reporting) and the clinician (symptom assessment) are important contributing factors to racial disparity in BC chemotherapy (Jiang et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2007; von Friederichs-Fitzwater & Denyse, 2012; Yee et al., 2017; Yoon et al., 2008).

Communication between healthcare providers and patients is a challenge, particularly for minority patients in a predominately racially discordant healthcare environment (Cooper et al., 2003). When compared with White patients, Black patients with cancer rate their physicians lower on supportive, partnering, and informative behaviors (Johnson et al., 2004; Sheppard et al., 2013). Patient-centered care (PCC), care that is concordant with the patient’s values, needs, and preferences (Clayton et al., 2011), has the potential to improve outcomes and reduce disparities. Both patients and clinicians can learn to enhance PCC. The Symptom Experience, Management, Outcomes and Adherence according to Race and Social Determinants of Health (SEMOARS) study will provide foundational evidence to inform future intervention development for clinicians to better listen to and interact with patients, who, in turn, will communicate their symptom distress, concerns about quality of life (QoL), and informational needs.

Theoretical Framework

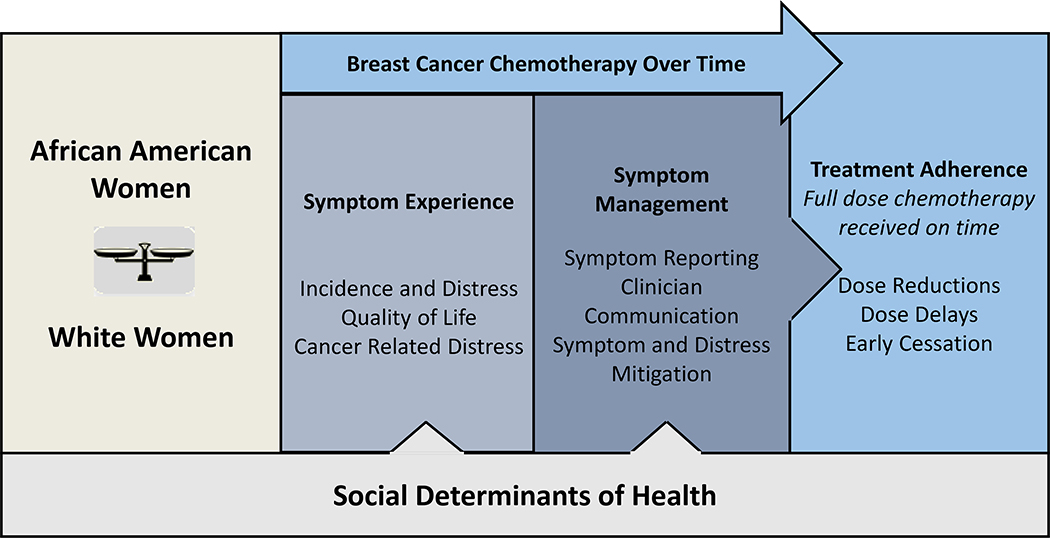

The SEMOARS Model (Figure 1) is informed by the University of California San Francisco Model of Symptom Incidence and Management (Dodd et al., 2001). It is a culmination of the authors’ previous work, modeling the hypothesis that racial disparity in BC treatment occurs because there is racial disparity in the incidence and severity of cancer-related symptoms and distress and a subsequent disparity in symptom reporting and management. This disparity leads to worsening or poorly mitigated symptoms and distress and, ultimately, a decision on the part of the providers to hold, delay, or terminate chemotherapy for Black women or a reluctance on the part of the patient to continue with therapy. Social determinants of health (SDOH), which may add an additional layer of vulnerability, are measured broadly, beyond sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., race, age, education), to include concepts such as health literacy, allostatic load, financial toxicity, self-efficacy, belief in medication, and healthcare trust (Table 2). Each of the SDOH may influence women’s ability to receive full-dose and timely chemotherapy; however, have only been studied in the most superficial fashion. The explication of this process, according to race, is the purpose of our study.

Figure 1.

Proposed SEMOARS Model: The Influence of Cancer Symptom Experience, Management and Outcomes According to Race and Social Determinants

Table 2.

Measures

| Construct/Measures | Aim | Timepoint administered | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Factors | 1,2,3 | baseline | N/A |

| University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing Sociodemographic Questionnaire | |||

| Health Literacy | 3 | baseline | |

| BRIEF Health Literacy Screening Assessment Tool (Wallston et al., 2014) | 0.76–0.80 | ||

| Subjective Numeracy Scale (Fagerlin et al., 2007) | 0.82 | ||

| Perceived Social Support | 3 | baseline | 0.70 |

| Interpersonal Support Evaluation (Sarason et al., 1987) | |||

| Health Care Trust | 3 | baseline | 0.75 |

| . System Distrust Scale (Shea et al., 2008) | |||

| Belief in Medication | 3 | baseline | 0.77 |

| Belief About Medicines Questionnaire (Riekert & Drotar, 2002) | |||

| Self-efficacy | 3 | baseline | 0.76 |

| The General Self-Efficacy Scale (Sherer et al., 1982) | |||

| Allostatic load | 3 | baseline | 0.91 |

| Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983) | |||

| Total Symptom Distress | 2 | pre-chemo | |

| The McCorkle Symptom Assessment (McCorkle, 1987) | 0.82 | ||

| PROMIS for Symptom Assessment (Fries et al., 2005) | 0.97 | ||

| Cancer-Related Distress | 2 | pre-chemo | 0.93 |

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (Mitchell, 2007) | |||

| Quality of Life | 2 | pre-chemo | 0.61–0.90 |

| The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast (FACT–B; Brady et al., 1997) | |||

| Financial Toxicity | 2 | pre-chemo | |

| Comprehensive Score Financial Toxicity (COST; de Souza et al., 2014) | 0.90 | ||

| Measure of Economic Hardship (Conger et al., 1993) | 0.80 | ||

| Patient Centeredness of Care | 2 | post-chemo | 0.61–0.91 0.71 |

| The Interpersonal Processes of Care (IPC) (Johnson et al., 2004) | |||

| Patient Perception of Patient-Centeredness Questionnaire (PCCC) (Stewart et al., 2004) | |||

| Symptom Reporting and Management | 2 | post-chemo | N/A |

| University of Pittsburgh Subject Interview Naming and Reporting Questionnaire | |||

| Clinician Demographics | 2 | once, post-chemo | N/A |

| Clinician Demographic Form | |||

| Communication | 2 | post-chemo | N/A |

| Audio recording | |||

| Clinical factors | 1,2,3 | ongoing, throughout each chemo cycle | N/A |

| Medical Chart Review | |||

| Tumor Characteristics | |||

| Initiation of chemotherapy/% of prescribed chemo/week | |||

| Chemotherapy appointment adherence | |||

| Reasons for non-adherence—appointments, dose reductions/Termination | |||

Note. N/A = not applicable; Pre-chemo = 1–2 days prior to next cycle of chemotherapy; Post-chemo = 5–7 days after chemotherapy administration.

Objectives

The SEMOARS protocol is a longitudinal, repeated measures, comparative, mixed-methods, descriptive study. Human subjects research approval was obtained from the University of Pittsburgh Human Research Protection Office (STUDY19050299). The specific aims are to:

-

1)

Examine and compare chemotherapy received/prescribed over time and in total of matched Black and White women prescribed BC chemotherapy. We hypothesize that Black women will receive a lower percentage of chemotherapy prescribed with more delays and early termination over time compared to White women.

-

2a)

Examine and compare the symptom incidence, distress, and management, and clinical encounter experience, including PCC and symptom management, of matched Black and White women receiving BC chemotherapy over time. We hypothesize that Black women will experience more symptoms, more distress, worse QoL, and less effective symptom management, including PCC, over time compared to White women, affecting their ability to receive the full dose of prescribed chemotherapy.

-

2b)

Compare associations for symptom incidence, distress, and management of matched Black and White women receiving BC chemotherapy to Aim 1. We hypothesize that there will be relationships between symptom incidence, distress, and the ability to receive full dose/on time chemotherapy.

-

3)

Explore the effects of SDOH on Aims 1, 2a, and 2b.

Methods

Community Advisory Board (CAB)

Our team has assembled an advisory group comprised former patients, clinicians, and community volunteers with expertise in BC and disparity, and a commitment to breast health, public education, and support for Black women with BC. The study team consulted with the CAB regarding this clinically focused proposal. Together, many elements were decided, including the informed consent process and selection of study instruments. The CAB and research team will continue to meet annually to discuss study conduct and emerging findings.

Sample and Setting

For this study, 358 (179 White and 179 Black) women diagnosed with early-stage BC will be recruited from 10 sites in Western Pennsylvania and Northeast Ohio. Power analyses were conducted using data from our previous cohort, in which 49.3% of Black women received < 85% of cumulative chemotherapy dose. We will have 80% power to detect a difference as small as 14% for Aim 1 using a likelihood ratio test with a sample of 137 per group (274 total). We will also be able to detect differences in mean adherence as small as d = 0.340 and trajectories using repeated measures with the F-test as small as f = 0.242. Aim 2 has 80% power to detect differences in mean severity rating as small as f = 0.279 assuming autocorrelation between repeated assessments. These calculations assume a two-sided test and α = .05. Allowing for 20% attrition over the course of the study, we anticipate at least 286 (143 Black and 143 White) women for full data collection.

Procedure

Eligibility Screening and Enrollment

If a woman is recommended to receive chemotherapy and all other inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) are met, clinic staff provides a brief scripted study overview and asks if she is interested in learning more. If so, a research associate is introduced, the study presented, and questions answered. If the patient agrees, informed consent takes place. At the recommendation of the CAB, research staff interacting with participants are racially diverse, helping to create an atmosphere conducive to the enrollment of minority women (Gallups et al., 2016) This approach was successful in the authors’ past research, as evidenced by a 98% recruitment rate. Understandably, the time immediately after BC diagnosis can be overwhelming for women. If the oncologist determines that timing is not optimal to present the study, arrangements are made to meet the patient at a later time and a brochure is provided.

Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Female a | Impaired cognition, as determined by clinician’s assessment |

| Black or White race a | |

| 18 years of age or older | Inability to understand English |

| Diagnosed with invasive (Stages 1–3) breast cancer | Diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer |

| Recommended (prescribed) chemotherapy by participating oncologist | Chemotherapy outside clinic of consent |

| Prior chemotherapy |

Note.

self-reported

Compensation

Participants are paid $10 for each data collection using university-issued reloadable, Mastercard®-branded, stored value payment cards, for a possible total of $180 over the study.

Data

Questionnaire data are managed using Qualtrics© software (Provo, UT) and medical chart data are managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), both hosted at the University of Pittsburgh. In accordance with university data security standards, data and audio files are stored in a password-protected study folder hosted on secure internal servers accessible only by study staff. Measures and their constructs, collection times, related aim, and psychometric properties, if applicable, can be found in Table 2.

Data Collection

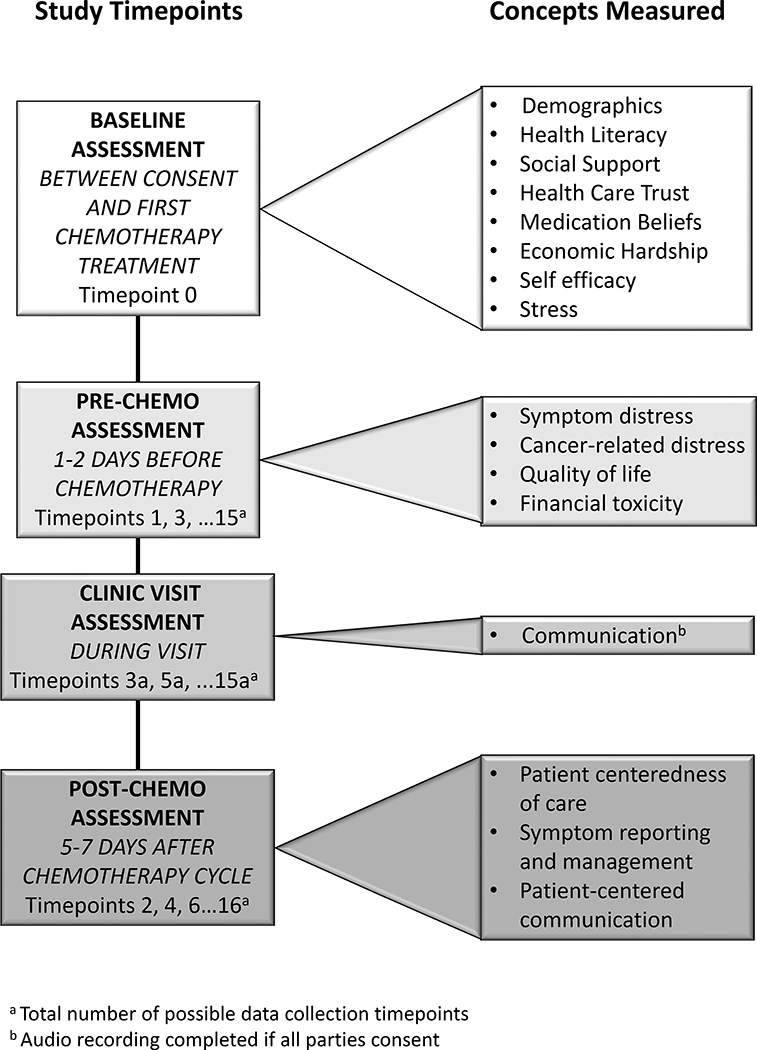

The study employs a prospective, longitudinal design with repeated measures (up to 18 timepoints/patient). Measurement occurs at baseline and then before and after each cycle of chemotherapy (Figure 2). On the rare instance that chemotherapy is given on a different schedule, the data collection is adjusted proportionately. This data collection schedule was chosen based on previous work, showing that 64% of symptom incidence with a severity ≥ 4 (0–10 scale) occurred within the first 7 days of treatment. (Unpublished data, Rosenzweig)

Figure 2.

Study Flow Diagram: Data Collection

Note: Patients have varied numbers of prescribed chemotherapy cycles from 4–8.

Quantitative data collection

For surveys, participants choose their preferred data collection method: over the phone; on paper and returned using a postage paid envelope; or online using the university’s research-approved Qualtrics® software.

Qualitative data collection

The participant’s medical oncology clinic visits are audiotaped, with the permission of all involved parties. This includes the patient, her healthcare providers, and any family member(s) or friend(s) who may be present during the clinic visit. Recordings occur from the time the healthcare provider (nurse practitioner, physician assistant, and/or physician) enters the exam room until the provider leaves. Audiotapes are transcribed using the University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR) Qualitative Data Analysis Program (QDAP) services. They are then coded according to the Four Habits Coding Scheme (Krupat et al., 2006), and analyzed by two research staff blinded to patient identification.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data are analyzed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary NC) for descriptive and exploratory analyses and repeated measures modeling. Mplus (version 8.3, Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA) will be used for possible mediation and moderated mediation analyses. Unless otherwise specified, two-sided hypothesis testing is used with α = .05, and confidence intervals are computed at 95% for point estimates.

Post hoc propensity scores will be estimated for each subject and will be derived via logistic regression methods considering all suspected confounding variables, including SDOH as well as prescribed chemotherapy. Estrogen receptor status is not considered a potential confounder since women will not receive endocrine therapy while receiving chemotherapy.

Data analysis strategy for Aim 1

Repeated-measures modeling (e.g., mixed-effects regression modeling; marginal modeling) will be used to examine changes in chemotherapy adherence over time and whether changes differ between racial groups. For each adherence variable, graphs will be constructed displaying each participant’s responses as a function of time since initial assessment for the total sample and by racial group. In general, mixed-effects regression models (Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006) will be used to analyze the longitudinally assessed outcomes of interest in this study. If the normality assumption for model errors cannot be reasonably satisfied, alternate versions of mixed-effects regression models will be considered. Models will initially be developed, allowing for random intercepts and trends over time. The models will then be expanded to consider participants’ race as a moderating factor by adding a main effect for race and ultimately one or more interaction terms depending on the complexity of the modeling of the time effect. To further balance the distribution of observed characteristics between the racial groups, mixed-effects regression models will be adjusted by propensity scores. Additionally, possible clustering effects (e.g., site) will also be considered when modeling. Maximum likelihood (ML; or restricted ML [REML]) techniques will be used for parameter estimation. From these fitted models, regression coefficients will be estimated to summarize the average response trajectory for the amount of chemotherapy received and timeliness of chemotherapy doses, as well as individual-specific deviations from the average time trend for each outcome variable. Main effects for time and racial group and interaction effects between time variables and racial group will be tested using F-statistics; individual regression parameters will be tested using the ratio of the estimated regression parameters to their asymptotic standard errors, which follow a t-distribution. Model assessment will entail the assessment of residuals and identification of possible influential observations. Sensitivity analyses will be used to assess the extent of influence of the identified observations.

Data analysis strategy for Aim 2

A repeated measures modeling approach, similar to that described in Aim 1, will be applied to the intermediate outcome variables of symptom incidence and distress experienced over the course of chemotherapy. Secondary outcome variables will include cancer-related distress, financial toxicity, and QoL. To test the associated hypothesis that symptom experience differs between Black and White women with Black women reporting more symptoms and more distress over the course of chemotherapy, race by time interactions will be examined. If the normality assumption cannot be satisfied, alternate versions of mixed-effects regression models assuming nonnormal error distributions will be considered. A similar repeated-measures modeling approach, as outlined for Aim 1, will be applied to the intermediate outcome variables of patient perception and understanding of symptom communication, self-care, and symptom management strategies to explore changes over the course of chemotherapy and whether these changes differ between Black and White women with BC. Audiotaped and transcribed medical visits will be coded according to the patient centeredness of care. These tapes and transcripts will be analyzed by two research staff blinded to patient identification. Inter-rater reliability will be determined for each analysis (Ritchie et al., 2014).

Data analysis strategy for Aim 3

To explore the possible moderation by SDOH (e.g., allostatic load, social support, healthcare trust), the repeated measures models estimated for Aims 1 through 3—considering race as a moderator of time effects for the aim-specific outcome variable—will be expanded to consider each SDOH individually as a moderator of race by time interactions. As for Aim 2, parameter estimation of moderated moderation effects (point and interval) rather than formal hypothesis testing will be the primary focus of this investigation.

Further exploratory analyses

Additionally, we will explore the possible mediation illustrated in Figure 1, using latent growth curve modeling methods, specifically full longitudinal mediation. Each of the longitudinal outcome variables (identified in Aims 1, 2, and 3) will first be modeled using univariate latent curve modeling. Then, using multivariate latent trajectory models, we will explore whether symptom management factors (listed in Figure 1) are longitudinal mediating variables for the outcome of interest, chemotherapy adherence. As tenable, longitudinal mediation models will be “stacked” (i.e., simultaneously fitted) through multigroup analyses to explore race-specific differences (i.e., moderated mediation). The goodness of fit of the fitted models will be evaluated using standard summary indices (e.g., root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI)) as well as through residual analysis.

Results

Participant recruitment and enrollment began in January 2018. We anticipate final enrollment by August 2021 and complete data collection by February 2022. Baseline analyses will be performed, with full results expected following study completion.

Discussion

The main purpose of SEMOARS is to create an important explanatory model of racial differences in symptom experience, reporting, management, and outcomes, including the ability to receive full dose of chemotherapy. This study is among the first to incorporate the effect of SDOH on symptom experience and outcomes through a racial lens. This study is particularly innovative and patient-centered in four ways:

The focus on symptoms and distress as etiologic factors in dose disparity in BC, measured by thorough, longitudinal assessment of symptoms, distress, and QoL and an exact accounting of the clinical encounter over the course of BC treatment as compared by race;

the acknowledgment that the clinical encounter, incorporating the assessment of PCC, is an important opportunity for the examination of racial treatment disparity and potential area for mitigation for both patient and clinician;

the exploration of the relationship between SDOH, including novel measurements of the effect of poverty and patient outcomes, specifically the ability to receive full-dose chemotherapy; and

the statistical analysis approach of propensity score methods to better control for sociodemographic factors and ultimately better tailor interventions.

Limitations

We comment on a few limitations in our study. First, the decision was made not to include the clinician’s perceptions of the clinical encounter. We considered adding a debriefing interview with clinicians to ascertain real-time reasons for dose alterations; however, it is unlikely that the clinician will recall additional information beyond notes included in the medical record or acknowledge any bias in a debriefing interview. Additionally, we had concerns about potential contamination in future interactions.

A multitude of “omic” pathways could be tested as possible pharmacoethnic influences on chemotherapy and/or symptom experience (O’Donnell & Dolan, 2009). Biologic factors may be an important determinant of symptom experience severity and may influence the metabolism of chemotherapy and symptom mitigating medications. We have taken advantage of this research infrastructure and have received additional funding for genomic and metabolomic analysis (National Institutes of Health UL1TR001857).

There is a possibility of the Hawthorne Effect (Nguyen et al., 2018). In order to avoid site contamination, the description of the study and recruitment requests from the study team to clinical staff will emphasize the longitudinal measurement of symptoms for women beginning chemotherapy. We do not emphasize the comparison of racial groups. Finally, measures which encourage symptom reporting may artificially enhance the amount of patient symptom reporting that occurs throughout chemotherapy. We acknowledge that this threat is present, but there is no evidence that the effect will occur in a racially discordant manner.

Conclusion

This study has the goal of creating an important explanatory model, according to race and SDOH, regarding symptom experience, reporting, management, and outcomes leading to the ability of women with BC to receive the full dose of prescribed chemotherapy. Defining barriers to receiving timely and full-dose chemotherapy is important when considering strategies for mitigating treatment and survival disparity. If these relationships and racial differences are confirmed and the mediating factors identified as actionable targets, this information will fill a critical gap in the quality care literature, advancing the understanding and potential mitigation strategies for the static racial survival disparity in BC. These identified targets hold implication for cancer care and public health more broadly.

Acknowledgement

This project is supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities R01MD012245 and Genentech Grant G-52266. The project described was also supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number UL1TR001857. M. McCall is also supported by National Institute of Nursing Research (T32NR009759; PI: Conley); Doctoral Degree Scholarship in Cancer Nursing (DSCN-19– 049-01) from the American Cancer Society; the Rockefeller University Heilbrunn Family Center for Research Nursing through the generosity of the Heilbrunn Family; and a Research Doctoral Scholarship from the Oncology Nursing Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, Genentech, the American Cancer Society, Rockefeller University/Heilbrunn Family Center, or the Oncology Nursing Foundation.

The authors wish to thank the Community Advisory Board for their guidance.

This research is conducted ethically and approved by the Human Research Protection Office (IRB) at the University of Pittsburgh (STUDY19050299).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Clinical Trial Registration: Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Bethany D. Nugent, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

Maura K. McCall, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

Mary Connolly, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

Susan R. Mazanec, Case Western Reserve University Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Cleveland, OH.

Susan M. Sereika, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

Catherine M. Bender, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

Margaret Q. Rosenzweig, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

References

- Bhatnagar B, Gilmore S, Goloubeva O, Pelser C, Medeiros M, Chumsri S, Tkaczuk K, Edelman M, & Bao T (2014). Chemotherapy dose reduction due to chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant settings: A single-center experience. SpringerPlus, 3, 366 10.1186/2193-1801-3-366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR, Deasy S, Cobleigh M, & Shiomoto G (1997). Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast quality-of-life instrument. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 15, 974–986. 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton MF, Latimer S, Dunn TW, & Haas L (2011). Assessing patient-centered communication in a family practice setting: How do we measure it, and whose opinion matters? Patient Education and Counseling, 84, 294–302. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, & Whitbeck LB (1993). Family economic stress and adjustment of early adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology, 29, 206–219. 10.1037/0012-1649.29.2.206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, & Powe NR (2003). Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139, 907–915. 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, Wroblewski K, Ratain MJ, Cella D, & Daugherty CK (2014). The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer, 120, 3245–3253. 10.1002/cncr.28814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, & Siegel RL (2019). Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69, 211–233. 10.3322/caac.21555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd M, Janson S, Facione N, Faucett J, Froelicher ES, Humphreys J, Lee K, Miaskowski C, Puntillo K, Rankin S, & Taylor D (2001). Advancing the science of symptom management. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33, 668–676. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01697.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA, Jankovic A, Derry HA, & Smith DM (2007). Measuring numeracy without a math test: Development of the subjective numeracy scale. Medical Decision Making, 27, 672–680. 10.1177/0272989X07304449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries JF, Bruce B, & Cella D (2005). The promise of PROMIS: Using item response theory to improve assessment of patient-reported outcomes. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 23, S53–S57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallups SF, Connolly M, Simon J, & Rosenzweig MQ (2016). Quantifying the relational dimensions of study staff in a randomized controlled trial among African American women recommended to receive breast cancer chemotherapy. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship, 7, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Griggs JJ, Sorbero MES, Stark AT, Heininger SE, & Dick AW (2003). Racial disparity in the dose and dose intensity of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 81, 21–31. 10.1023/A:1025481505537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, & Gibbons RD (2006). Longitudinal data analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 10.1002/0470036486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Sereika SM, Bender CM, Brufsky AM, & Rosenzweig MQ (2016). Beliefs in chemotherapy and knowledge of cancer and treatment among African American women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 43, 180–189. 10.1188/16.ONF.180-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, & Cooper LA (2004). Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 2084–2090. 10.2105/AJPH.94.12.2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knisely AT, Michaels AD, Mehaffey JH, Hassinger TE, Krebs ED, Brenin DR, Schroen AT, & Showalter SL (2018). Race is associated with completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Surgery, 164, 195–200. 10.1016/j.surg.2018.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupat E, Frankel R, Stein T, & Irish J (2006). The four habits coding scheme: Validation of an instrument to assess clinicians’ communication behavior. Patient Education and Counseling, 62, 38–45. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCorkle R (1987). The measurement of symptom distress. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 3, 248–256. 10.1016/S0749-2081(87)80015-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ (2007). Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorders. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 4670–4681. 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VNB, Miller C, Sunderland J, & McGuiness W (2018). Understanding the Hawthorne effect in wound research—A scoping review. International Wound Journal, 15, 1010–1024. 10.1111/iwj.12968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell PH, & Dolan ME (2009). Cancer pharmacoethnicity: Ethnic differences in susceptibility to the effects of chemotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research, 15, 4806–4814. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson LC, Wang W, Hartzema AG, & Wagner S (2007). The role of health-related quality of life in early discontinuation of chemotherapy for breast cancer. Breast Journal, 13, 581–587. 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riekert KA, & Drotar D (2002). The beliefs about medication scale: Development, reliability, and validity. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 9, 177–184. 10.1023/A:1014900328444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Lewis J, McNaughton Nicholls C, & Ormston R (Eds.). (2014). Qualtitative research practice: A guide for social science students (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig MQ (2019). The ACTS intervention to reduce breast cancer treatment disparity. Unpublished raw data. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig MQ, & Wesmiller S (2016, March). Racial differential in pain and nausea during breast cancer chemotherapy In Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 25 American Association of Cancer Research; 10.1158/1538-7755.DISP15-C11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR, & Sarason IG (1987). Interrelations of social support measures: Theoretical and practical implications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 813–832. 10.1037/0022-3514.52.4.813 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott AB, & McClure JE (2010). Engaging providers in medication adherence: A health plan case study. American Health & Drug Benefits, 3, 372–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea JA, Micco E, Dean LT, McMurphy S, Schwartz JS, & Armstrong K (2008). Development of a revised health care system distrust scale. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23, 727–732. 10.1007/s11606-008-0575-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard VB, Isaacs C, Luta G, Willey SC, Boisvert M, Harper FWK, Smith K, Horton S, Liu MC, Jennings Y, Hirpa F, Snead F, & Mandelblatt JS (2013). Narrowing racial gaps in breast cancer chemotherapy initiation: The role of the patient-provider relationship. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 139, 207–216. 10.1007/s10549-013-2520-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer M, Maddux JE, Mercandante B, Prentice-Dunn S, Jacobs B, & Rogers RW (1982). The Self-Efficacy Scale: Construction and validation. Psychological Reports, 51, 663–671. 10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.663 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M, Meredith L, Ryan BL, & Brown JB (2004). Working paper series: The patient perception of patient-centeredness questionnaire (PPPC). Centre for Studies in Family Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- von Friederichs-Fitzwater MM, & Denyse RT (2012). The unmet needs of African American women with breast cancer. Advances in Breast Cancer Research, 1, 1–6. 10.4236/abcr.2012.11001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallston KA, Cawthon C, McNaughton CD, Rothman RL, Osborn CY, & Kripalani S (2014). Psychometric properties of the brief health literacy screen in clinical practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29, 119–126. 10.1007/s11606-013-2568-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, Ottesen RA, Wong Y-N, Edge SB, Theriault RL, Blayney DW, Niland JC, Winer EP, Weeks JC, & Partridge AH (2015). Racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: Mediating effect of tumor characteristics and sociodemographic and treatment factors. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33, 2254–2261. 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JS, Strickland OL, Dalton JA, & Freeman S (2015). Adherence to intravenous chemotherapy in African American and white women with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer Nursing, 38, 89–98. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee MK, Sereika SM, Bender CM, Brufsky AM, Connolly MC, & Rosenzweig MQ (2017). Symptom incidence, distress, cancer-related distress, and adherence to chemotherapy among African American women with breast cancer. Cancer, 123, 2061–2069. 10.1002/cncr.30575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J, Malin JL, Tisnado DM, Tao ML, Adams JL, Timmer MJ, Ganz PA, & Kahn KL (2008). Symptom management after breast cancer treatment: Is it influenced by patient characteristics? Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 108, 69–77. 10.1007/s10549-007-9580-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, King J, Wu X-C, Hsieh M-C, Chen VW, Yu Q, Fontham E, Loch M, Pollack LA, & Ferguson T (2019). Racial/ethnic differences in the utilization of chemotherapy among stage I–III breast cancer patients, stratified by subtype: Findings from ten National Program of Cancer Registries states. Cancer Epidemiology, 58, 1–7. 10.1016/j.canep.2018.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]