Abstract

Background:

Anxiety symptoms are common in adolescence and are often considered developmentally benign. Yet for some, anxiety presents with serious comorbid non-anxiety psychopathology. Early identification of such “malignant” anxiety presentations is a major challenge. We aimed to characterize anxiety symptoms suggestive of risk for depression and suicidal ideation (SI) in community youth.

Methods:

Cross-sectional associations were evaluated in community youths (n=7,054, mean age 15.8) who were assessed for anxiety, depression and SI. We employed factor and latent class analyses to identify anxiety clusters and subtypes. Longitudinal risk of anxiety was evaluated in a subset of 330 youths with longitudinal data on depression and SI (baseline mean age 12.3, follow-up mean age 16.98).

Outcomes:

Almost all (92%) adolescents reported anxiety symptoms. Data driven approaches revealed anxiety factors and subtypes that were differentially associated with depression and SI. Cross-sectional analyses revealed that panic and generalized anxiety symptoms showed the most robust associations with depression and SI. Longitudinal, multivariate analyses revealed that panic symptoms during early adolescence, and not generalized anxiety symptoms, predict depression and SI years later, particularly in males.

Interpretation:

Anxiety is common in youth, with certain symptom clusters/subtypes predicting risk for depression and SI. Panic symptoms in early adolescence, even below disorder threshold, predict high risk for late adolescent depression and SI.

Keywords: Anxiety, Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort, Adolescent Depression, Suicidal Ideation, Factor Analysis, Latent Class Analysis

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are often the first presentation of psychopathology in youth, and are considered the most common psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents (Beesdo, Knappe, & Pine, 2011; Costello, Copeland, & Angold, 2011; Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Merikangas et al., 2010; Taylor, Lebowitz, & Silverman, 2017); one in three adolescents in the US meet criteria for a lifetime anxiety disorder (Costello et al., 2011; Kessler et al., 2012; Merikangas et al., 2010; Van Bockstaele et al., 2014). Adolescent anxiety is highly comorbid with other psychiatric conditions, including depression (Costello et al., 2003) and suicidal ideation (SI), above and beyond co-occurring depression (O’Neil Rodriguez & Kendall, 2014). Furthermore, longitudinal studies suggest that anxiety in youth is linked to subsequent psychiatric disorders and impaired functioning (Beesdo-Baum & Knappe, 2012). Yet, the majority of children with an anxiety disorder have never received treatment (Chavira, Stein, Bailey, & Stein, 2004). The low rates of youth receiving treatment for anxiety may be related to an under-appreciation of the impairment caused by anxiety (Coles & Coleman, 2010) and lack of awareness that anxiety is often a harbinger of non-anxiety psychopathology (Foley, Goldston, Costello, & Angold, 2006). As such, there is a clinical need to identify specific anxiety manifestations suggestive of non-anxiety serious psychiatric conditions so as to help clinicians understand the seriousness of anxiety symptoms and conduct research that can help flag the symptoms most associated with serious non-anxiety psychiatric conditions, like depression and SI (i.e., malignant anxiety symptoms).

Despite the significant heterogeneity of anxiety disorders (Williams et al., 2016), there is substantial overlap in the manifestation and treatment of anxiety across anxiety disorders in youth (Rey, 2006; Taylor et al., 2018). Indeed, past work suggests that for preadolescents, the strong overlap among anxiety symptoms may obscure the presence of specific types of anxiety (Ferdinand, Lang, Ormel, & Verhulst, 2006). Thus, anxiety symptomology in youth likely cuts across categorical anxiety disorders, complicating attempts to pinpoint specific anxiety symptoms most predictive of serious psychiatric comorbidities. Furthermore, most studies have investigated associations of anxiety disorders that meet DSM criteria; as such, little is known of how anxiety symptoms uniquely relate to other psychiatric conditions, such as depression and SI, in youth.

Data-driven approaches may be particularly helpful in identifying youth at risk for psychopathology and suicidal behavior (Carli et al., 2014) and elucidating symptom-level relationships among anxiety, depression, and SI in youth (Hankin et al., 2016). Because some, but not all, anxiety symptom profiles may be associated with depression or SI, data driven approaches can help uncover patterns in anxiety symptoms, reducing the phenotypic heterogeneity, and differentiate more “malignant” from more “benign” anxiety symptoms or subtypes. To meet this challenge, we employed several data driven approaches in a large (N=7,054) community-based youth cohort with comprehensive clinical phenotyping that included anxiety symptoms across anxiety disorders: agoraphobia, specific phobia, social anxiety, separation anxiety, panic, and generalized anxiety. First, we identified domains of anxiety symptoms using factor analysis; next we identified specific, yet common classes of anxiety presentations using latent class analysis; then we examined how these anxiety symptom domains and classes are associated with depression, suicidal ideation, and impairment in function. We also conducted network analyses to examine the nature of relationships between anxiety symptoms, SI, and impaired functioning. Lastly, drawing form the data-driven approaches, we then examined whether “malignant” anxiety manifestations pose a risk for later adolescent depression and SI in a subset of youths with available longitudinal data. We hypothesized that (1) several anxiety symptom domains and classes would emerge as malignant, having a strong association with depression/SI while others would show a more benign standing; (2) the malignant symptoms themselves would have a stronger association to depression/SI than a known risk factor (i.e., family history of depression and SI); (3) malignant anxiety symptoms would predict later depression/SI in a longitudinal sample; (4) given the known sex and age differences in anxiety (Kessler et al., 2012; Taylor, Lebowitz, & Silverman, 2017), we hypothesized that the relationship between the malignant anxiety factors and outcome variables would be stronger in females and older youth. Thus, the current paper uses data driven methods to help stratify anxious youth with specific anxiety symptoms into different levels of risk for depression and SI later in adolescence.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants (N=7,054, age 11–21 years, 46% male, 56% Caucasian) are from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort (PNC), a collaboration between the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and the Brain Behavior Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania (Calkins et al., 2015). The sample is racially and socioeconomically diverse (Moore et al., 2016), and includes participants who were directly interviewed (youths under age 11, with only parent report, were not included). Notably, participants were recruited from the pediatric care network and not from psychiatric clinics, and the sample is not enriched for individuals who seek psychiatric help. Enrollment criteria included: ambulatory in stable health, proficiency in English, physical and cognitive capability of participating in an interview and performing the neurocognitive assessment. Written informed consent was obtained from participants aged ≥ 18, and written assent and parental permission were obtained from children aged <18. University of Pennsylvania and CHOP’s Institutional Review Boards approved all procedures.

Clinical Assessment

Lifetime psychopathology symptoms were evaluated by trained and supervised assessors (Bachelor’s and Master’s level who underwent rigorous standardized training and certification) using a structured screening interview (Calkins et al., 2015), based on Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS) (Kaufman et al., 1997). Lifetime history of anxiety disorders and depressive episodes was determined present if symptoms were endorsed with frequency and duration approximating DSM-IV episode criteria, accompanied by significant distress and/or impairment. Lifetime SI was determined through a direct question regarding having thoughts of killing oneself. Level of function (for the past 6 months) was evaluated using the Occupational Functioning Scale (N6) of the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (Miller et al., 1999). A score greater than zero on this item represents difficulties in age-appropriate role functions (e.g., school performance, difficulties in relationships). First degree family histories of depression and suicide (completed or attempted) were also recorded during the interview using an abbreviated version of the Family Interview for Genetic Studies (see online Supplementary Methods) (Maxwell, 1996).

Assessment of Anxiety Symptoms

For each anxiety section in the clinical interview (i.e., agoraphobia, specific phobia, panic, social, separation, and generalized anxiety), participants were first asked a series of screener (yes/no) items for each disorder (31 screener items in total). If the participant endorsed a screener item, additional questions were asked to assess number, frequency, and duration of specific symptoms to determine disorder status. For the factor and latent class analyses, we only used data from the screener anxiety items from the child’s direct interview (Table 1).

Table 1-.

Anxiety symptoms included in the clinical assessment and their loadings in the factor analysis.

| Category | Screener Item | Anxiety Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phobia | Social | Separation | Panic | Generalized | ||

| AGR | Nervous/afraid of going over bridges or through tunnels | 0.71 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| PHB | Nervous/afraid of flying or airplanes | 0.63 | 0 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.11 |

| PHB | Nervous/afraid of animals or bugs, like dogs, snakes, or spiders | 0.62 | 0 | −0.05 | −0.19 | 0.13 |

| AGR | Nervous/afraid of using public transportation | 0.6 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.2 | −0.11 |

| PHB | Nervous/afraid of storms, thunder, or lightning | 0.56 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.11 | 0.07 |

| PHB | Nervous/afraid of being in really high places, like a roof or tall building | 0.56 | 0.06 | −0.09 | −0.09 | 0.09 |

| AGR | Nervous/afraid of traveling by yourself | 0.53 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.02 | −0.1 |

| AGR | Nervous/afraid of traveling in a car | 0.52 | −0.1 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.1 |

| PHB | Nervous/afraid of closed spaces, like elevators or closets | 0.52 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.1 |

| AGR | Nervous/afraid of being in an open field | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.19 | −0.13 |

| PHB | Nervous/afraid of water of situations involving water, such as a swimming pool, lake, or ocean | 0.46 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.07 |

| AGR | Nervous/afraid of traveling away from home | 0.45 | 0.1 | 0.44 | 0.04 | −0.08 |

| PHB | Nervous/afraid of any other things or situations | 0.43 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

| PHB | Nervous/afraid of doctors, needles, or blood | 0.37 | 0.1 | 0.01 | −0.16 | 0.13 |

| AGR | Nervous/afraid of going to public places (such as a store or shopping mall) | 0.36 | 0.35 | −0.02 | 0.35 | −0.13 |

| SOC | Afraid/uncomfortable when you had to do something in front of a group of people | −0.07 | 0.87 | 0.02 | −0.1 | 0.03 |

| SOC | Afraid/uncomfortable acting, performing, giving a talk/speech, playing a sport or doing a musical performance, or taking an important test or exam | 0.02 | 0.8 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.06 |

| SOC | Afraid/uncomfortable because you were the center of attention and you were concerned something embarrassing might happen | −0.01 | 0.79 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| SOC | Really shy with people, like meeting new people, going to parties, or eating or drinking, writing or doing homework in front of others | 0.01 | 0.78 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| SOC | Afraid/uncomfortable talking on the telephone or with people your own age who you don’t know very well | 0.06 | 0.61 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0 |

| AGR | Nervous/afraid of being in crowds | 0.36 | 0.39 | −0.07 | 0.31 | −0.09 |

| SEP | Very upset and worried when away from home or attachment figure(s) | 0.03 | 0 | 0.77 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| SEP | Wanted to stay home from school or not go to other places without your attachment figure(s) | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.74 | −0.04 | 0.06 |

| SEP | A lot of worries about your attachment figure(s) and upset/got sick when you were away from him/her | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.67 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| SEP | Scared to be alone in your room (or any place in your house) or need your attachment figure(s) to stay with you while you fell asleep | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.13 |

| SEP | Worry/had bad dreams about something terrible happening to attachment figure | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.41 | 0.18 | 0.11 |

| PAN | Very scared or uncomfortable, your chest hurt, couldn’t catch your breath, heart beat fast, felt shaky, and sweaty/tingly/numb in your hands/ feet | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.77 | 0.04 |

| PAN | All of a sudden, you felt that you were losing control, something terrible was going to happen, that you were going crazy, or going to die | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.75 | 0.1 |

| PAN | Very scared, even though there was nothing around to frighten you and you can’t breathe/heartbeat fast | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0 | 0.71 | 0.18 |

| GAD | You worry a lot and often feel nervous, anxious or unable to relax. You have times when you worry a lot more than usual | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.8 |

| GAD | You worry a lot more than most children/people your age | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.74 |

Most salient loadings of symptoms to factors are in bold. Abbreviations: AGR= agoraphobia symptoms; PHB= specific phobia symptoms; SOC= social anxiety symptoms; SEP= separation anxiety symptoms; PAN= panic disorder symptoms; GAD= generalized anxiety disorder symptoms.

Longitudinal Assessment of Depression and Suicidal Ideation

Review of CHOP electronic health records revealed that Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A) (Johnson, Harris, Spitzer, & Williams, 2002) data were available for a subset of participants (n=330, mean age 12.4 at PNC assessment and 17 years at PHQ-A, 47.6% male, 38.5% Caucasian, see Supplemental Table S1 for additional demographics). The PHQ-A was administered as part of an adolescent wellness check for almost all participants in the subsample (n=323, 97.9%), which screened for depressive symptoms in the last 2-weeks. We used a cutoff score of ten as an indication of depression status as it was recently validated diagnosing adolescent depression (Levis, Benedetti, Thombs, & DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration, 2019). In addition, patients were asked a separate question regarding presence of SI in the last month. The longitudinal subsample had similar gender distribution and clinical characteristics with an age-matched group from the PNC cohort, but differed in racial distribution and SES (see Supplemental Table S2).

Data Analyses

Factor Analysis

To investigate anxiety symptom domains, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA; least-squares extraction, with oblimin oblique rotation) was performed on tetrachoric correlations among all 31 anxiety items. Number of factors extracted was determined by a combination of five empirical methods: parallel analysis with Glorfeld correction (Glorfeld, 1995), Zoski multiple regression procedure (Zoski & Jurs, 1993), Cattell-Nelson-Gorsuch method (Cattell, R. B., Gorsuch, R. L., & Nelson, 1981), minimum Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)(Schwarz, 1978), and minimum average partial (Velicer, 1976). These methods suggested 5, 4, 3, 7, and 5 factors, respectively. We used the median number (5) for the number of factors to extract, which agreed with subjective examination of the scree plot (also suggesting 5 factors). Mplus and R were used for analyses.

Latent Class Analysis

To investigate individual profiles of anxiety symptoms, latent class analysis (LCA) was used to discover classes of youth displaying similar symptomatology profiles across multiple anxiety symptoms and categories. To determine the number of classes to extract, we first tried minimum Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (Schwarz, 1978), which suggested extracting >10 classes, Lo-Mendel-Rubin suggests 6 classes, bootstrapped LR test suggested >10 classes. Because the ten classes would clearly be an over-extraction and the methods listed above for EFA are not available for LCA, we based our choice of the number of classes on interpretability. That is, this approach was exploratory with some subjective clinical judgment used to determine the optimal solution. Mplus and R were used for analyses.

Network Analysis

Description of the symptom-level links with depression, SI, and functioning were also examined using network analysis using the qgraph package (Epskamp, Cramer, Waldorp, Schmittmann, & Borsboom, 2012) in R (https://www.r-project.org/). Relations among nodes were estimated in a network with all items of interest (i.e., anxiety symptoms and dependent variables). See online supplementary methods for a graphical depiction of the network results (Supplemental Figure S1) as well as additional information on the analyses.

Cross-sectional Association of Anxiety Phenotypes with Depression/SI

Following the factor analysis, we conducted a series of binary logistic regressions to test the hypothesis that certain anxiety factors would be strongly related to depression/SI/impaired functioning, while other anxiety factors would have a more benign association. Participants were considered as belonging to each anxiety domain if they endorsed at least one symptom within a given factor. This approach was used, as opposed to the participants’ factor scores from the EFA, to better aid in clinical interpretation. Symptoms that loaded across factors were included in the factor for which they had the highest loading. For symptoms that had a cross loading ≥ .3, sensitivity analyses were conducted that either included the symptoms in all factors for which they loaded or removed them from all factors. These sensitivity analyses revealed that the results remained the same no matter how the cross-loading symptoms were handled. Separate regressions were performed with all anxiety domains as independent variables and a single binary dependent variable (depression/SI/impaired functioning), co-varying for age, sex and socioeconomic status (SES). Interactions between anxiety domains and sex or age were tested in separate models.

Similarly, exploratory analyses were conducted to examine how panic and generalized anxiety domains, above and beyond a known risk factor (i.e., family history), are associated with depression/SI. Binary logistic regressions were conducted with panic/generalized anxiety domains and family history of depression/suicide (attempted or completed) as independent variables with depression/SI as dependent variables, co-varying for age, sex and SES.

After conducting the latent class analysis, a similar series of binary logistic regressions were performed with each anxiety class contrasted with the low anxiety class as the independent variables, and depression/SI/impaired functioning as the dependent variables, co-varying for age, sex and SES. Binary regressions were conducted in SPSS version 26 (IBM).

Longitudinal Analysis

The last set of analyses examined the longitudinal associations between early adolescent anxiety domains and late adolescent depression/SI. Binary regression models were conducted with panic or generalized anxiety domains (the domains with the highest magnitude of cross-sectional association with depression/SI, hypothesized to be predictive of negative outcomes) at baseline as independent variables and with PHQ-A depression/SI at longitudinal assessment as the dependent variable, co-varying for age, sex, race, SES; and for baseline depression/SI and family history of depression/SI in separate models. We used the domains estimated from the FA in the larger sample in the smaller sample. Interactions between anxiety domains and sex or age were tested in separate models.

Results

Prevalence of anxiety symptoms and factor analysis

The vast majority of PNC youths endorsed at least one anxiety screener symptom (N=6,487, 92% of sample), while 2,892 (41% of sample, of which >30% were phobias) fulfilled DSM criteria for at least one lifetime anxiety disorder. The five-factor model (Table 1) categorizes anxiety screener items into five symptom domains: phobia (including both agoraphobia and specific phobia items), panic, social, separation, and generalized anxiety. Table 2 presents prevalence of youth endorsing at least one item in each anxiety domain, as well as prevalence of youth meeting DSM criteria for each of the anxiety disorders. Additionally, Supplemental Table S3 includes the matrix of inter-item tetrachoric correlations, to three decimal places for replication purposes. The scree plot of eigenvalues from this matrix is shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

Table 2.

Rates and characteristics of participants with anxiety symptoms (A, upper panel) and anxiety disorders (B, lower panel)

| A. | Endorsement of Anxiety Symptoms (N=7054) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | Any Anxiety Symptoms | Phobia Symptoms | Social Anxiety Symptoms | Separation Anxiety Symptoms | Panic Symptoms | Generalized Anxiety Symptoms | No Anxiety Symptoms | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 6487 | 92 | 5512 | 78.10 | 4051 | 57.40 | 3682 | 52.20 | 1907 | 27.00 | 3800 | 53.90 | 454 | 6.40 | |

| Sex-female | 3595 | 94.40 | 3179 | 83.50 | 2316 | 60.80 | 2128 | 55.90 | 1200 | 31.50 | 2328 | 61.20 | 173 | 4.50 | |

| Sex-male | 2892 | 89.10 | 2333 | 71.90 | 1735 | 53.40 | 1554 | 47.90 | 707 | 21.80 | 1472 | 45.30 | 281 | 8.70 | |

| Race, white | 3616 | 92.60 | 2990 | 77.40 | 2101 | 54.80 | 1976 | 52.20 | 1038 | 26.50 | 2244 | 57.20 | 289 | 7.40 | |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (yrs) | 15.21 | 2.67 | 15.16 | 2.67 | 15.26 | 2.66 | 15.12 | 2.67 | 15.62 | 2.66 | 15.38 | 2.68 | 15.03 | 2.8 | |

| SES, Z-score | −0.001 | 0.998 | −0.0319 | 1 | −0.082 | 1.03 | −0.0384 | 1 | −0.0446 | 1 | 0.0613 | 0.976 | 0.1704 | 0.931 | |

| B. | Fulfill DSM Criteria (N=7054) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Anxiety Disorder | Agoraphobia | Specific Phobia Disorder | Social Anxiety Disorder | Separation Anxiety Disorder | Panic Disorder | Generalized Anxiety Disorder | No Anxiety Disorder | ||||||||||

| n | % | N | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 2882 | 40.90 | 424 | 6.10 | 2148 | 32.60 | 920 | 13.00 | 294 | 4.20 | 114 | 1.60 | 184 | 2.60 | 4122 | 58.40 | |

| Sex-female | 1801 | 47.30 | 297 | 70.00 | 1381 | 64.30 | 554 | 14.60 | 203 | 5.30 | 77 | 2.00 | 133 | 3.50 | 1986 | 52.20 | |

| Sex-male | 1081 | 33.30 | 127 | 30.00 | 827 | 25.50 | 366 | 11.30 | 91 | 2.80 | 37 | 1.10 | 51 | 1.60 | 2136 | 65.80 | |

| Race, White | 1521 | 52.80 | 158 | 37.30 | 1127 | 52.50 | 586 | 52.80 | 182 | 61.90 | 64 | 56.10 | 117 | 63.60 | 2421 | 58.70 | |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (yrs) | 15.88 | 2,64 | 15.55 | 2.68 | 15.77 | 2.63 | 16.22 | 2.56 | 16.02 | 2.65 | 16.49 | 2.69 | 16.92 | 2.42 | 15.72 | 2.80 | |

| SES, Z-score | −0.07 | 1.01 | −0.41 | 1.03 | −0.85 | 1.01 | −0.07 | 1.01 | 0.13 | 0.94 | −0.14 | 1.07 | 0.16 | 0.90 | 0.06 | 0.99 | |

In upper panel (A), numbers (n) in each factor represent total participants who endorsed at least 1 symptom in a factor. In lower panel (B), numbers (n) represent total participants who fulfill DSM criteria for the index anxiety disorder. SES= socioeconomic status based on geocode and US Census data.

Cross-sectional associations of anxiety factors with depression, suicidal ideation and impaired functioning

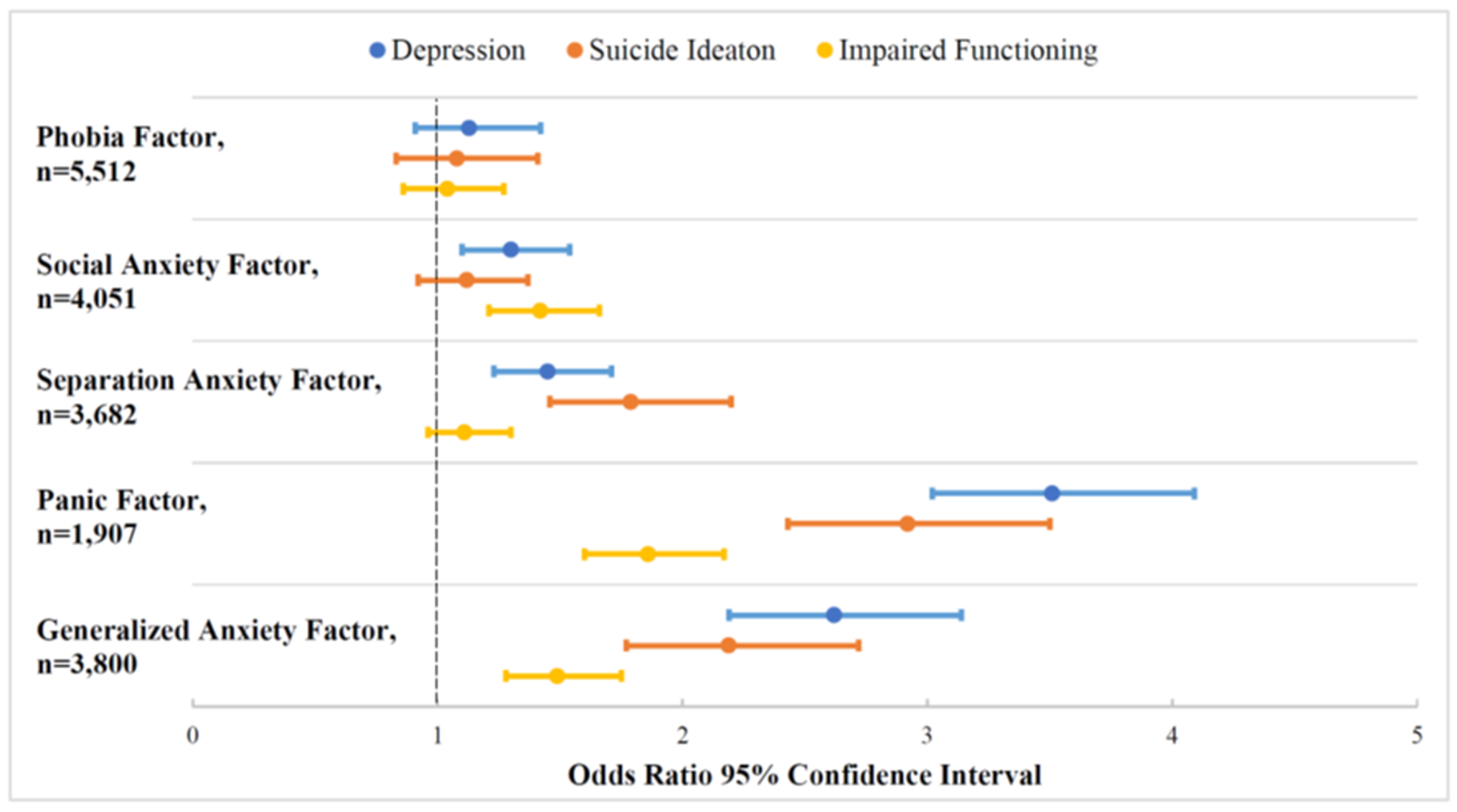

We next investigated the association between endorsing symptoms from each of the anxiety domains with lifetime history of major depressive episode or SI and with current (previous six months) impaired functioning (Figure 1; Supplemental Table S4). All anxiety symptom domains except for phobia were significantly associated with depression. The panic domain showed the highest odds ratio (OR=3.51) followed by generalized anxiety (OR=2.62). Associations with SI were significant for panic (OR=2.92), generalized anxiety (OR=2.19), and separation anxiety (OR=1.79) domains, but not for phobias or social anxiety domains. Lastly, panic (OR=1.86), generalized anxiety (OR=1.49) and social anxiety (OR=1.42) domains were significantly associated with impaired functioning. Regarding sex and age interactions, the panic domain showed greater cross-sectional association with SI in females (panic X sex interaction, Wald=4.19, p=0.04). The social anxiety domain showed greater association with impaired functioning in later adolescence (social anxiety X age interaction, Wald=5.02, p=0.025). No other significant sex or age interactions emerged in any model (supplementary Table S3).

Figure 1-.

Association of anxiety domains with depression, suicidal ideation, and impaired function

Odds ratios were calculated based on binary logistic regression models including all anxiety symptom domains, controlling for age, sex, and socioeconomic status.

We next sought to validate the robust association of panic and generalized anxiety symptom domains with depression/SI through comparing these associations to a known risk factor like family history of depression/SI. In all models, the association between panic or generalized anxiety domains with concurrent depression and SI were robust, even when covarying for family history of depression/SI (all OR>2.5 for both panic and generalized anxiety, p’s<0.001). Notably, both of the anxiety domains showed more robust associations with depression than did family history of depression (OR=2.9/3.8 for panic/generalized and OR=1.4 for depression family history, p’s<=0.001).

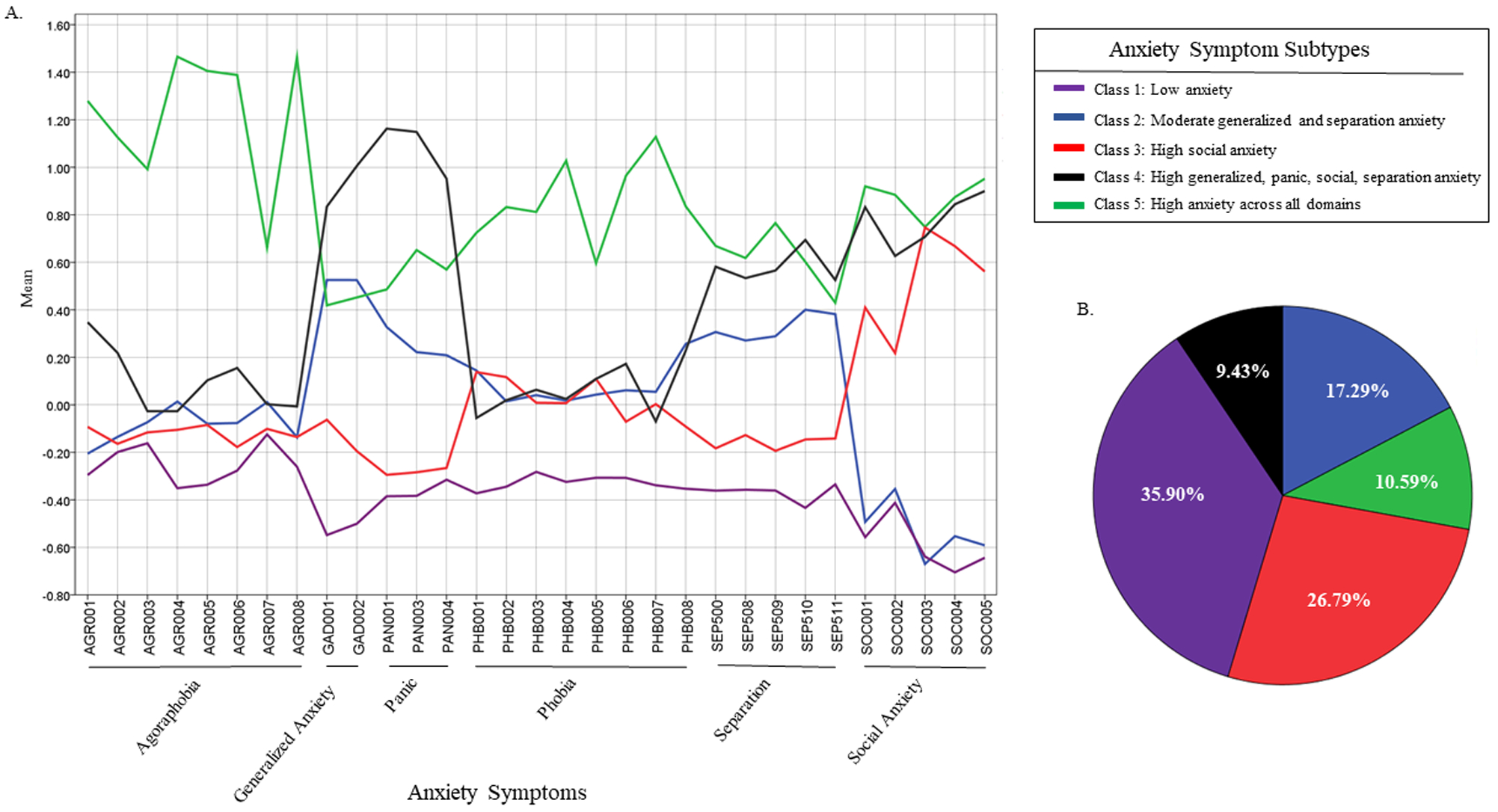

Latent class analyses of anxiety symptoms

Latent class analysis of the anxiety screening items revealed five classes (Figure 2 panel A, where y-axis is mean z-score of the item). In this model, youth are assigned a probability score of belonging to each of the 5 classes: a low anxiety symptom group (class 1: mean probability=0.90, SD=0.15), moderate generalized and separation anxiety symptoms (class 2: mean probability=0.82, SD=0.17); high social anxiety (class 3: mean probability=0.85, SD=0.16); high generalized anxiety and panic (class 4: mean probability=0.81, SD=0.18); and high anxiety symptoms across all domains, with moderate GAD and panic symptoms (class 5: mean probability=0..87, SD=0.17). Note the above probabilities are the means across participants assigned to that cluster, not the mean across the whole sample. Entropy (Ramaswamy, Desarbo, Reibstein, & Robinson, 1993) for the 5-class solution is 0.78. Using the arbitrary but common cutoff of 0.80, class membership probabilities were acceptable, while entropy was borderline. Note that LCAs with entropy values <0.80 (even <0.70) are very common in the literature, and a safe approach here would be to use the class membership probabilities only to assign class membership, not as continuous indicators in subsequent analyses. See (Masyn, 2013) for general review and (Morgan, 2015) for a thorough review of fit indices.

Figure 2 -.

Latent classes of anxiety symptomatology in youth

Anxiety classes across symptoms (A) and percentile distribution of class membership (B) based on participants’ highest probability of class assignment. The y-axis in Figure 2A represents mean z-score of the item within a class. Model entropy = 0.78; Bayesian Information Criterion = 182651.76; Akaike Information Criterion = 181528.06.

Figure 2 (panel B) shows the distribution of each class if participants are assigned to their highest probability group. We next investigated the association of probability of assignment to each of the four anxiety classes contrasted against the low anxiety class, with depression, SI and impaired functioning. All four anxiety classes were significantly associated with all three outcomes (Supplemental Table S5); however, individuals in class 4 (high panic and generalized anxiety) and class 5 (high anxiety across all anxiety domains) had significantly greater lifetime association with depression and SI and greater functional impairment.

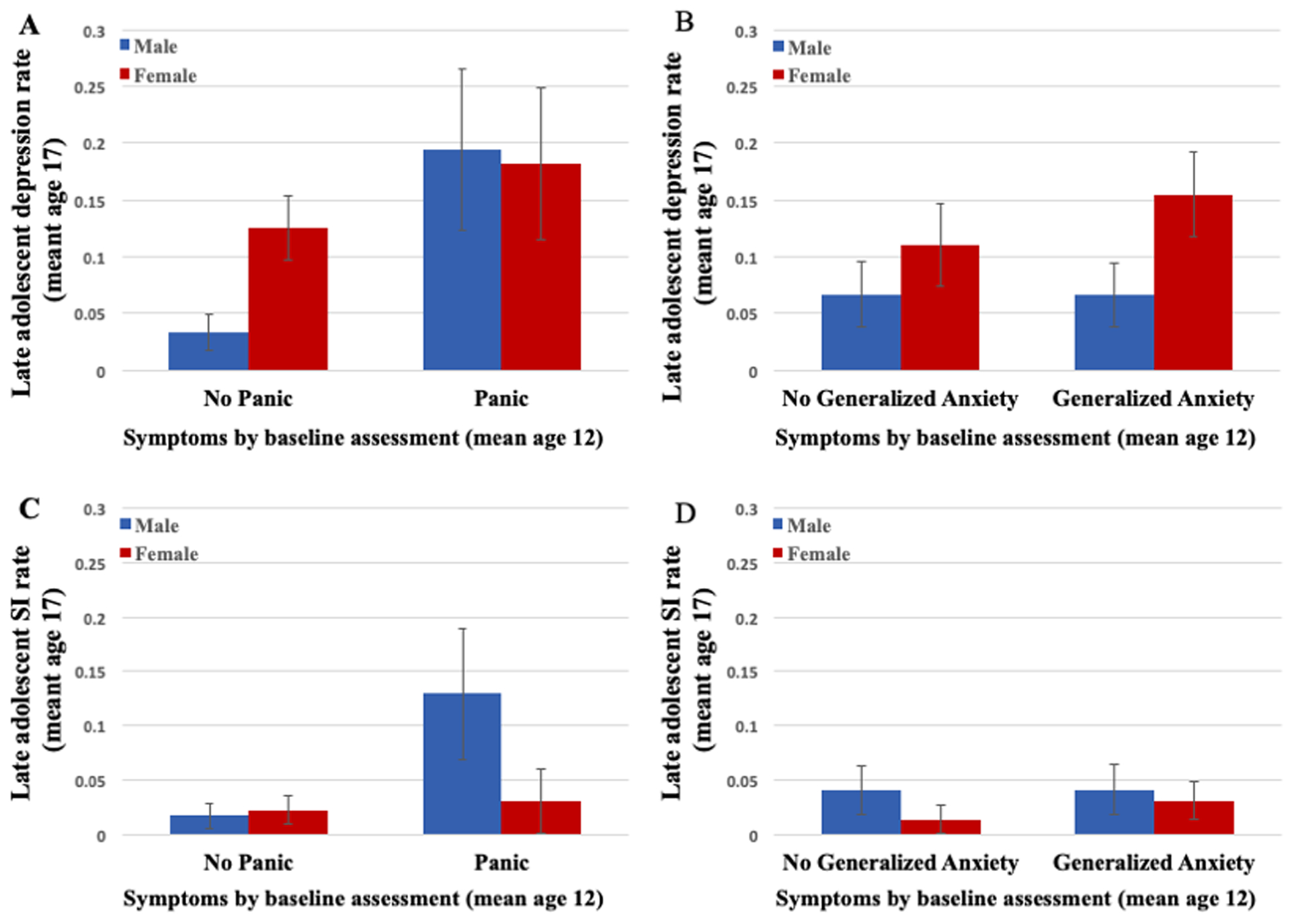

Longitudinal associations of panic and generalized anxiety symptoms with depression/SI

Longitudinal data on depression/SI screening from electronic health records was obtainable for a subset of participants (n=330, mean age 17 years at longitudinal assessment). Of this sample, thirty-three youths (10%) screened positive for current depression (PHQ-A>=10) and ten (3%) for current SI. Predictive modeling adjusting for sex, SES, race, and duration of follow-up revealed that having panic symptoms in early adolescence was a significant predictor of late adolescent depression (OR=2.48, p=0.03) and SI (OR=4.27, p=0.036) (Supplemental Table S6). After additionally adjusting for family history of depression/SI and baseline depression/SI, early adolescent panic symptoms predicted subsequent SI (OR=9.36, p=0.01); however, the association between early adolescent panic symptoms and subsequent depression was reduced to a trend (OR=2.34, p=0.06). There was a significant sex interaction, such that the presence of early adolescent panic symptoms increased the risk of later depression more so in males than females (Wald =4.31, p=0.038), co-varying for demographics, baseline depression and family history of depression (Figure 3, supplementary Table S5). The generalized anxiety symptom domain did not predict depression/SI in late adolescence and showed no significant sex interactions.

Figure 3-.

Baseline panic and generalized symptoms by preadolescence and the risk for late adolescent depression and suicidal ideation (SI).

Longitudinal risk of panic (A,C) and generalized anxiety symptoms (B,D) to depression (A,B) and SI (C,D). Abbreviation: SI, suicidal ideation. Error bars represent standard errors.

Discussion

We found a high lifetime prevalence of anxiety symptoms (~92%), suggesting anxiety symptoms are part of typical development (Beesdo-Baum & Knappe, 2012), and usually sub-clinical. The large sample (N=7,054) and comprehensive phenotyping (31 anxiety screener items) allowed investigation of specific anxiety phenotypes and enabled the parsing of anxiety phenotypic heterogeneity using three data driven approaches (factor analysis, latent class analysis, and network analyses). Examination of concurrent (lifetime) and future associations among anxiety presentations, depression and SI revealed several notable findings. First, anxiety symptoms and anxiety subclasses are robustly associated with depression, SI, and impaired functioning; however, the magnitude of association varies by anxiety domain/class. For instance, panic and generalized anxiety symptoms had the most robust associations with concurrent depression and SI. Second, a similar pattern of results emerged for longitudinal associations between panic symptoms and later depression and SI. Since the current analyses categorized individuals by symptoms, and not disorders, these results suggest that the comorbidities associated with anxiety manifestations, even at a subclinical or symptom level, can be high and severe. Moreover, our work uniquely extends the findings from previous large population-based studies, like the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (Kessler et al., 2012) because our study focuses on anxiety symptoms in youth, as opposed to anxiety disorders. Specifically, our findings highlight the potential importance of screening for and monitoring panic symptoms, even when DSM criteria for panic disorder are not met.

The most robust and consistent finding that emerged from the current set of results was the association between youth panic symptoms, and to a somewhat lesser extent generalized anxiety symptoms, and depression and SI. Indeed, the association between these anxiety symptoms with depression in youth was stronger than that of a family history of depression. Our longitudinal findings showing that panic symptoms in early adolescence (mean age 12), but not generalized anxiety, predict late adolescent depression and SI, make a specific contribution to the effort to identify predictors of adolescent depression and suicide trajectories (Shore, Toumbourou, Lewis, & Kremer, 2018). Moreover, early adolescent panic symptoms predicted late adolescent SI (and late adolescent depression at statistical trend level), even after adjusting for family history of SI/depression and baseline SI/depression. Our results might suggest that screening youth for panic symptoms, and not just depression symptoms, may improve clinicians’ ability to identify and stratify youth at risk for subsequent depression and SI. These findings add to prior work reporting that panic attacks in mid-adolescence are a risk factor for later serious psychopathology (Goodwin et al., 2004) and pose an additive risk for future depression and SI, above and beyond any other anxiety disorder at baseline (Bittner et al., 2004).

Latent class analysis revealed five anxiety classes ranging from low anxiety across all anxiety categories, to high anxiety in specific symptom categories, to high anxiety across all anxiety areas. This finding adds to the field of developmental psychopathology, as prior work in pre-adolescents reported no distinct subclasses of specific anxiety disorder symptoms in community children (Ferdinand et al., 2006). Our sample comprised older adolescents (mean age 15 years). It is possible that in younger children, the overlap in anxiety symptoms cuts across different anxiety domains such that no specific anxiety subtypes or classes are prominent; whereas in adolescence, anxiety symptoms appear to cluster in specific classes. This pattern might implicate mid-adolescence as the first developmental window during which specific brain circuitries can be linked to anxiety subtypes. The finding has implications for anxiety clinical trials, as pediatric anxiety trials often combine anxiety disorders (Compton et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2018), and our findings suggest that while such an approach may be appropriate in children, it may require revisiting in adolescent populations.

Notable sex differences emerged in the associations of anxiety symptoms with depression and SI in the current study. In the cross-sectional analyses, panic symptoms showed greater association with SI in females; while the longitudinal analysis suggests a trend that early adolescent panic symptoms posed higher risk for later depression in males. These sex differences may be due to important developmental differences in relations between anxiety and depression/SI (the cross-sectional cohort had a mean age of 15, the longitudinal cohort had a mean age of 12 at baseline). Perhaps in mid-to-late adolescence, panic symptoms represent a nonspecific presentation of depression that is over represented in females, whereas in early adolescence, panic symptoms represent a pre-morbid clinical phenotype that is indicative of future depression risk only in males. In addition, we cannot rule out that the different phenotypes (i.e., depression versus SI), are affected differently by the sex/gender of youths with panic symptoms.

Our results should be viewed considering certain limitations. The first limitation pertains to the longitudinal analysis. The longitudinal data was only obtainable for a convenience subsample of the cohort who had a routine well visit check-up in the CHOP system during adolescence. Moreover, this subsample was younger and enriched for lower SES than the full sample, and the longitudinal measurements are limited compared to the robust phenotyping at baseline. Notably, our longitudinal models co-varied for age and SES, somewhat addressing this limitation. In addition, the limited longitudinal phenotyping should have reduced power to predict outcomes (only n=33 met depression criteria and n=10 were suicide ideators), despite this we found that panic symptoms pose a clinically meaningful risk for later depression and SI. However, we may not have had power to detect other small effects. Furthermore, although longitudinal data was based on a routine well visit doctor’s appointment, it is unclear if the longitudinal sample was enhanced for depression and suicidal ideation; however, this sample did not differ from an age-matched control group on baseline anxiety, depression, or SI. Second, the baseline evaluation assessed lifetime, not current, symptoms. As such, beyond the limitation of cross-sectional analyses, the temporal relations among comorbidities reported in the cross-sectional analysis are unknown. Third, the baseline clinical evaluation of suicidal ideation included a single direct question (thought about killing oneself), without detailed probes for additional data such as history of suicide attempts. Notably, a recent study reported high sensitivity and specificity of using a single item regarding SI compared to more elaborate assessment of suicide related measures (Millner, Lee, & Nock, 2015). Fourth, the study predominantly includes youths from urban US, representing the sociodemographic landscape of Greater Philadelphia, and may be enriched for phenomena unique to the sociodemographic characteristics of the cohort. Fifth, it is possible that the order of item administration in the present study inflated the coherence of items within disorder. That is, because the K-SADS is based on DSM criteria and items are administered in an order corresponding to symptom hierarchies within one disorder at a time, it is possible that inter-item correlations within an interview section (e.g. panic disorder) are biased upwards. Nonetheless, we report rates of panic and generalized anxiety disorders (the symptoms of which are of highest clinical significance in the current study) that are consistent with prior literature (Merikangas et al., 2010). Finally, for the LCA analyses, since analytic methods tended to suggest over 10 classes, the classes determined were based largely on interpretability from a team of experts; this may have influenced the current pattern of results.

Conclusion

Recent data on increasing rates of teen suicide in the US (Ruch et al., 2019) highlight the need to improve early identification of youths with mental health burden in the community. The current study underscores the high prevalence of teen anxiety in community youths, and points to symptoms from the panic and generalized anxiety taxonomy as “red flags” for concurrent depression and SI. Moreover, panic symptoms in early adolescence are a risk factor for later adolescent depression and SI, and might therefore, when present, merit a more thorough mental-health evaluation and follow up. Findings may have substantial implications for mental health services and public health, suggesting that awareness should be placed to timely identify panic symptoms early in adolescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institute Of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23MH-120437, MH-R01107235, MH-R01089983, MH-R01096891, MH-P50MH06891, KL2TR-001879, the Dowshen Neuroscience fund, and the Lifespan Brain Institute of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Penn Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Barzilay serves on the scientific board and reports stock ownership in ‘Taliaz Health’, with no conflict of interest relevant to this work. All other authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Data analyzed in this study can be accessed through the publicly available dbGaP database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000607.v3.p2).

References

- Beesdo-Baum K, & Knappe S (2012). Developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 21(3), 457–478. 10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Knappe S, & Pine DS (2011). Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32(3), 483–524. 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002.Anxiety [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner A, Goodwin RD, Wittchen HU, Beesdo K, Höfler M, & Lieb R (2004). What characteristics of primary anxiety disorders predict subsequent major depressive disorder? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 10.4088/JCP.v65n0505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins ME, Merikangas KR, Moore TM, Burstein M, Behr MA, Satterthwaite TD, … Gur RE (2015). The Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort: constructing a deep phenotyping collaborative. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(12), 1356–1369. 10.1111/jcpp.12416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carli V, Hoven CW, Wasserman C, Chiesa F, Guffanti G, Sarchiapone M, … Wasserman D (2014). A newly identified group of adolescents at “invisible” risk for psychopathology and suicidal behavior: Findings from the SEYLE study. World Psychiatry. 10.1002/wps.20088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattell RB, Gorsuch RL, & Nelson J (1981). Cng scree test: An objective procedure for determining the number of factors. In Annual Meeting of the Society for Multivariate Experimental Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Chavira DA, Stein MB, Bailey K, & Stein MT (2004). Child anxiety in primary care: Prevalent but untreated. Depression and Anxiety. 10.1002/da.20039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles ME, & Coleman SL (2010). Barriers to treatment seeking for anxiety disorders: Initial data on the role of mental health literacy. Depression and Anxiety. 10.1002/da.20620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton SN, Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini JC, Birmaher B, Sherrill JT, … March JS (2010). Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS): Rationale, design, and methods. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 4, 1 10.1186/1753-2000-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Copeland W, & Angold A (2011). Trends in psychopathology across the adolescent years: What changes when children become adolescents, and when adolescents become adults? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02446.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, & Angold A (2003). Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, & Borsboom D (2012). Qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software. 10.18637/jss.v048.i04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinand RF, Lang NDJV, Ormel J, & Verhulst FC (2006). No distinctions between different types of anxiety symptoms in pre-adolescents from the general population. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley DL, Goldston DB, Costello EJ, & Angold A (2006). Proximal psychiatric risk factors for suicidality in youth the great smoky mountains study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glorfeld LW (1995). An improvement on Horn’s Parallel Analysis Methodology for selecting the correct number of factors to retain. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 55(3), 377–393. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Lieb R, Hoefler M, Pfister H, Bittner A, Beesdo K, & Wittchen HU (2004). Panic attack as a risk factor for severe psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Snyder HR, Gulley LD, Schweizer TH, Bijttebier P, Nelis S, … Vasey MW (2016). Understanding comorbidity among internalizing problems: Integrating latent structural models of psychopathology and risk mechanisms. Development and Psychopathology, 28(4pt1), 987–1012. 10.1017/S0954579416000663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2002). The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 30(3), 196–204. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11869927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, … Ryan N (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, … Merikangas KR (2012). Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD, & DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. (2019). Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 365, l1476 10.1136/bmj.l1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masyn KE (2013). Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling In Little T (Ed.), Oxford handbook of quantitative methods. Oxford University Press; 10.1093/OXFORDHB/9780199934898.013.0025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell ME Manual for the Family Interview for Genetic Studies (1996). Bethesda. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, … Swendsen J (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication-adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, Stein K, Driesen N, Corcoran CM, … Davidson L (1999). Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. In Psychiatric Quarterly. 10.1023/A:1022034115078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millner AJ, Lee MD, & Nock MK (2015). Single-item measurement of suicidal behaviors: Validity and consequences of misclassification. PLOS ONE, 10(10), e0141606 10.1371/journal.pone.0141606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Martin IK, Gur OM, Jackson CT, Scott JC, Calkins ME, … Gur RC (2016). Characterizing social environment’s association with neurocognition using census and crime data linked to the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort. Psychological Medicine, 46(3), 599–610. 10.1017/S0033291715002111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan GB (2015). Mixed mode latent class analysis: An examination of fit index performance for classification. Structural Equation Modeling, 22(1), 76–86. 10.1080/10705511.2014.935751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil Rodriguez KA, & Kendall PC (2014). Suicidal ideation in anxiety-disordered youth: Identifying predictors of risk. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 10.1080/15374416.2013.843463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy V, Desarbo WS, Reibstein DJ, & Robinson WT (1993). An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Marketing Science. INFORMS 10.2307/183740 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rey JM (2006). IACAPAP Textbook of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. In The Lancet. [Google Scholar]

- Ruch DA, Sheftall AH, Schlagbaum P, Rausch J, Campo JV, & Bridge JA (2019). Trends in suicide among youth aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1975 to 2016. JAMA Network Open, 2(5), e193886 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G (1978). Estimating the Dimension of a Model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. 10.1214/aos/1176344136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shore L, Toumbourou JW, Lewis AJ, & Kremer P (2018). Review: Longitudinal trajectories of child and adolescent depressive symptoms and their predictors - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 23(2), 107–120. 10.1111/camh.12220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JH, Lebowitz ER, Jakubovski E, Coughlin CG, Silverman WK, & Bloch MH (2018). Monotherapy insufficient in severe anxiety? Predictors and moderators in the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 10.1080/15374416.2017.1371028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JH, Lebowitz ER, & Silverman WK (2017). Anxiety Disorders In Martine A, Bloch MH, & Volkmar FR (Eds.), Lewis’s child and adolescent psychiatry: A comprehensive textbook. (5th ed, pp. 509–518). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer -- Medknow Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele B, Verschuere B, Tibboel H, De Houwer J, Crombez G, & Koster EHW (2014). A review of current evidence for the causal impact of attentional bias on fear and anxiety. Psychological Bulletin. 10.1037/a0034834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF (1976). Determining the number of components from the matrix of partial correlations. Psychometrika, 41(3), 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Williams LM, Goldstein-Piekarski AN, Chowdhry N, Grisanzio KA, Haug NA, Samara Z, … Yesavage J (2016). Developing a clinical translational neuroscience taxonomy for anxiety and mood disorder: Protocol for the baseline-follow up Research domain criteria Anxiety and Depression (“RAD”) project. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1). 10.1186/s12888-016-0771-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoski K, & Jurs S (1993). Using multiple regression to determine the number of factors to retain in factor analysis. Multiple Linear Regression Viewpoints, 20(1), 5–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.