Abstract

Copper binding to α-synuclein (α-Syn), the major component of intracellular Lewy body inclusions in substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons, potentiate its toxic redox-reactivity and plays a detrimental role in the etiology of Parkinson disease (PD). Soluble α-synuclein-Cu(II) complexes possess dopamine oxidase activity and catalyze ROS production in the presence of biological reducing agents via Cu(II)/Cu(I) redox cycling. These metal-centered redox reactivities harmfully promote the oxidation and oligomerization of α-Syn. While this chemistry has been investigated on recombinantly expressed soluble α-Syn, in vivo, α-Syn is acetylated at its N-terminus and is present in equilibrium between soluble and membrane-bound forms. This post-translational modification and membrane-binding alter the Cu(II) coordination environment and binding modes and are expected to affect the α-Syn-Cu(II) reactivity. In this work, we first investigated the reactivity of acetylated and membrane-bound complexes, and subsequently addressed whether the brain metalloprotein Zn7-metallothionein-3 (Zn7MT-3) possesses a multifaceted-role in targeting these aberrant copper interactions and consequent reactivity. Through biochemical characterization of the reactivity of the non-acetylated/N-terminally acetylated soluble or membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes towards dopamine, oxygen, and ascorbate, we reveal that membrane insertion dramatically exacerbates the catechol oxidase-like reactivity of α-Syn-Cu(II) as a result of a change in the Cu(II) coordination environment, thereby potentiating its toxicity. Moreover, we show that Zn7MT-3 can efficiently target all α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes through Cu(II) removal, preventing their deleterious redox activities. We demonstrate that the Cu(II) reduction by the thiolate ligands of Zn7MT-3 and the formation of Cu(I)4Zn4MT-3 featuring an unusual redox-inert Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster is the molecular mechanism responsible for the protective effect exerted by MT-3 towards α-Syn-Cu(II). This work provides the molecular basis for new therapeutic interventions to control the deleterious bioinorganic chemistry of α-Syn-Cu(II).

Keywords: alpha-synuclein, Parkinson’s disease, copper dysregulation, metallothionein-3, reactive oxygen species, dopamine oxidation

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder (ND), after Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and the most common neurodegenerative movement disorder. Affecting approximately 1% of people aged over 65 years and 4% of people over 85 years, PD patients experience progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain substantia nigra, leading to symptoms such as tremors, slowness of movement, rigidity, and eventually, dementia [1]. The histological hallmark of PD is the presence of intraneuronal inclusions called Lewy bodies (LB), primarily composed of aggregated and fibrillar forms of the protein alpha-synuclein (α-Syn) [2], [3]. Mutations in the α-Syn gene (SNCA) are linked to familial and early-onset forms of PD and overexpression of α-Syn in mice causes LB pathology and neurodegeneration [4]. These hallmarks link α-Syn aggregation to the development of PD pathology.

Physiologically, α-Syn is a soluble 14-kDa (140-residue) cytosolic protein that in vivo exists predominantly as an N-terminally acetylated unstructured monomer (NAcα-Syn) localized in the presynaptic termini of dopaminergic neurons [5]-[8]. While the physiological function of α-Syn is still under debate, it has been demonstrated to facilitate SNARE complex assembly and regulate vesicle fusion, exocytosis, and synaptic vesicle-mediated release of the neurotransmitter dopamine [5], [9]-[11]. In the presence of lipid vesicles, the N-terminal region of α-Syn assumes an amphipathic helical conformation due to seven imperfect 11-amino acid repeats in its sequence, forming by two curved α-helices (Val3-Val37 and Lys45-Thr92) connected by a short linker (Leu38-Thr44), followed by an extended region (Gly93-Gly97) and an unstructured mobile tail (Asp98-Ala140) [12]-[14]. Acidic residues line the outer surface of the helix while basic residues point sideward and interact with negatively charged headgroups of lipids. This leaves the inner portion of the curved helix hydrophobic, which moves past the charged headgroups and interacts with tails of lipids [12], [15]. Membrane-binding and insertion is consistent with the presynaptic localization of α-Syn and its membrane-related functions [13], [14].

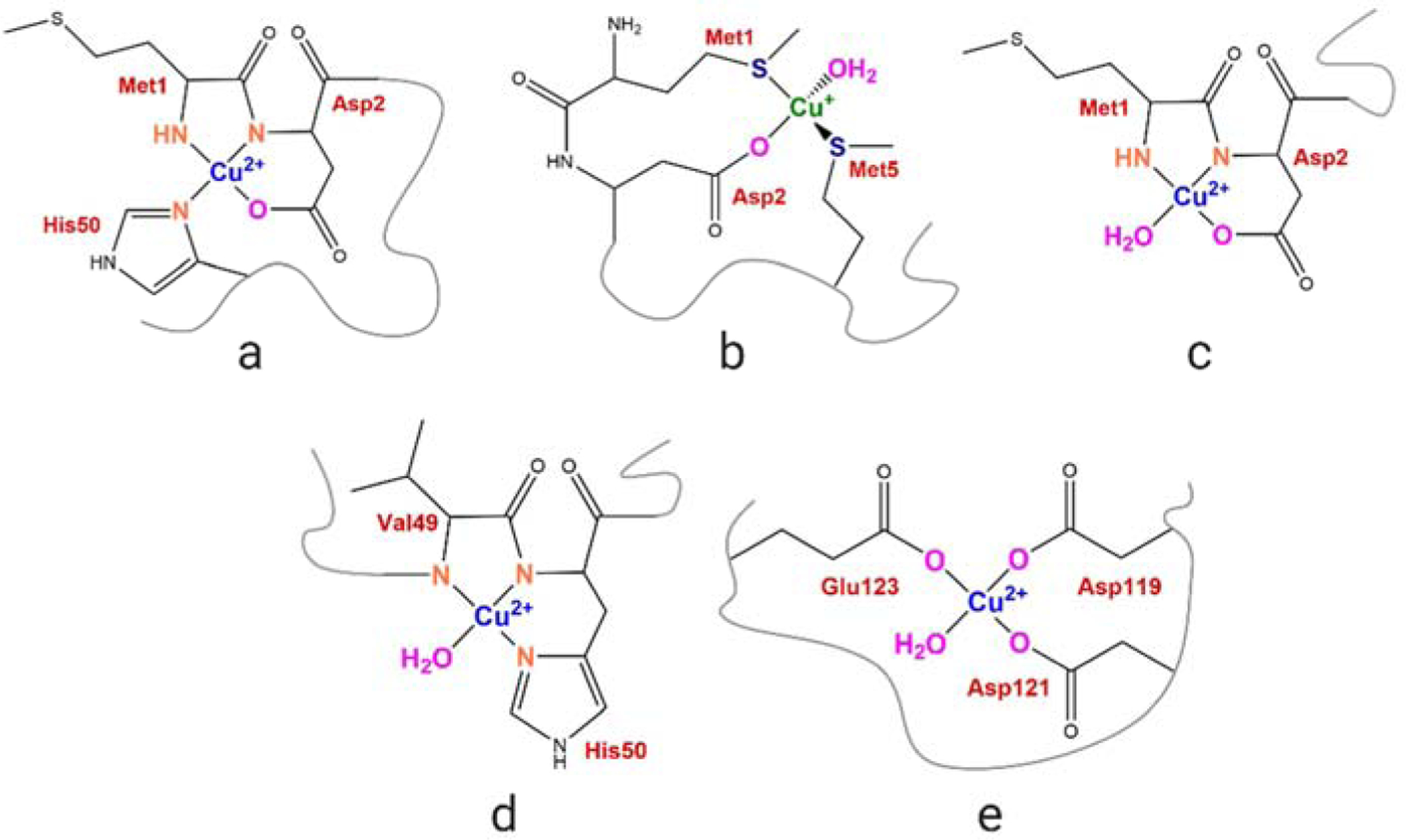

In PD, α-Syn misfolds into soluble oligomers or insoluble fibrillar/non-fibrillar aggregates, gaining toxic functions. Increasing evidence suggests the role of transitional metals, which are found to be dysregulated in NDs, in aberrantly binding to amyloidogenic proteins including α-Syn, thereby promoting aggregation and potentiating oxidative stress [16]-[19]. Copper is a transition metal present in high concentrations in the brain and shows a dysregulated metabolism in PD [20]-[23]. Copper can bind to non-acetylated recombinant α-Syn (NH2α-Syn) to form α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes which can catalyze toxic reactions such as dopamine oxidation, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production through catalytic Cu(I)/Cu(II) redox-cycling, amino acid side chain oxidation, and oligomer formation-processes that contribute to neuronal death and disease progression [23]-[28]. In agreement, Cu(II) is the most effective transition metal in promoting α-Syn self-oligomerization in vitro [29]. NH2α-Syn can bind copper at three sites: (1) a high-affinity N-terminal site centered on Met1-Asp2, (Figure 1a–c) (2) a lower-affinity site centered at His50 (Figure 1d) and (3) a partially-populated low-affinity C-terminal site anchored at D121 (Figure 1e) [17], [28], [30]-[37]. At the N-terminal high-affinity (Kd=10−9) binding site, NH2α-Syn coordinates Cu(II) in a square planar/distorted tetragonal geometry with the N-terminal amino nitrogen (NH2) of Met1, the deprotonated backbone amide (N−) and carboxylate oxygen of Asp2, and the imidazole nitrogen of His50 (at physiological pH of 7.4) as the main anchoring equatorial residues; axial coordination by Met1 side chain resulting in a square pyramidal complex was recently proposed [30], [31], [37] (Figure 1a). However, in physiologically N-terminally acetylated α-Syn, Cu(II) binding to the α-amino nitrogen at Met1 in the N-terminal high affinity site shifts to the lower affinity binding site centered at His50 and D121 [38], [39]. Recent investigation via electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analysis of the Cu(II) binding mode of NAcα-Syn was found to be consistent with N2O2/N3O1 coordination as suggested by DFT calculations [39], [40]. Cu(II) square planar coordination by backbone nitrogen atoms of Val49 and His50, the imidazole ring of His50, and a water molecule was proposed (Figure 1d), though the partial involvement of N-terminal ligands cannot be completely excluded [39]. NAcα-Syn also binds Cu(I) at its N-terminus, coordinated by the thioethers of Met1 and Met5 [32] (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Proposed copper coordination modes in α-Syn. (a) Cu(II) coordination at the high-affinity N-terminal site in soluble α-Syn at physiological pH; (b) Cu(I) coordination at the N-terminal site; (c) high affinity N-terminal site in membrane-bound form; (d) NAcα-Syn high-affinity site centered at His50; and (E) low-affinity C-terminal site.

In addition to the soluble form, when inserted in lipid bilayers, non-acetylated α-Syn was found to bind Cu(II) with similar affinity but assuming a different coordination environment. The membrane-embedded helical conformation spatially separates His50 from the N-terminus by about 75 Å, preventing its contributing to the Cu(II) coordination shell (Figure 1c) [41]. Whereas the ability of NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) to catalyze catechol oxidation and ROS production in the presence of biological reducing agents (e.g. ascorbate) and oxygen is established [26], [27], and the redox reactivity of an α-Syn-Cu(I)/Cu(II) peptide model (α-Syn1–15, both with free NH2 and N-acetylated) in the presence of SDS detergent micelles has been investigated [42], how the altered Cu(II) coordination environments in acetylated and membrane-bound full-length α-Syn forms affect the redox properties of α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes compared to NH2α-Syn remain to be further investigated. Moreover, how aberrant Cu(II) binding to these complexes can be targeted by protective endogenous metal chelators is elusive.

The neuronal metalloprotein Zn7-metallothionein-3 (Zn7MT-3) can target and silence the redox activity of soluble NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) [26]. Zn7MT-3 (also known as Growth Inhibitory Factor, GIF) is an intra/extracellular metal- and cysteine-rich protein that is highly expressed in the human brain, where it conducts central roles in the homeostasis of the essential metal ions Cu(I) and Zn(II) and in the regulation of neuronal outgrowth [43]-[46]. Previous investigations revealed that the expression levels and radical-scavenging potency of metallothionein-3 are reduced, contributing to the acceleration of disease progression [47], [48]. Zn7MT-3 contains two Zn-thiolate clusters (Zn3CysS9 and Zn4CysS11) in two separate protein domains (N-terminal β-domain and C-terminal α-domain, respectively) where metals are coordinated by a conserved array of 20 Cys residues [43]. We previously demonstrated that MT-3 plays important roles in controlling aberrant metal protein/peptide interactions through metal-swap reactions. Metal exchange and copper reduction occurs between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) bound to target peptide/protein-metal complexes in aberrant biding sites. ZnMT metal-thiolate clusters can efficiently reduce Cu(II) to Cu(I) and bind it to form Cu(I)4Zn4MT via cooperative formation of a redox-silent Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster in its N-terminal β-domain with partial zinc release [49]. Cu(I) binds to the β-domain with a much higher affinity (Kd= 10−19 M) than zinc [50]. This reaction can target high affinity protein-Cu(II) complexes such as amyloid-β-Cu(II) (Aβ-Cu(II)), α-Syn-Cu(II), and prion protein-Cu(II) (PrP-Cu(II)) complexes, thereby preventing their toxicity [26], [51]-[54]. While this reactivity was investigated for soluble non-acetylated α-Syn-Cu(II), the capability of MT-3 in targeting aberrant copper binding sites in the acetylated and membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) forms, thereby silencing their reactivities, remain to be established.

In this work, we first investigated the redox properties of the physiologically relevant forms of α-Syn-Cu(II), i.e. acetylated and membrane-bound, and subsequently addressed the ability of Zn7MT-3 in silencing their reactivity. Our work reveals that while the soluble NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) possess similar redox reactivities as the non-acetylated form, membrane-binding drastically exacerbates α-Syn dopamine oxidase activity. Furthermore, we demonstrated that Zn7MT-3 can efficiently remove Cu(II) from all forms and silence the redox reaction catalyzed by α-Syn-Cu(II), thereby playing a broad protective role toward α-Syn-Cu(II) by abolishing its toxic redox chemistry.

Results and discussion

N-terminally acetylated α-Synuclein-Cu(II) exhibits catechol oxidase and redox activity

N-terminally acetylated α-Syn (NAcα-Syn) is the most abundant form of α-Syn in vivo [5]. Extensive characterization of the α-Syn-Cu(II) redox properties has been conducted without post-translational modification due to the use of α-Syn expressed recombinantly in E.Coli-a system that provides high expression yields but without N-terminal acetylation due to the lack of N-α-acetyltransferases (Nat). In this work, we expressed both NH2α-Syn and the physiologically relevant NAcα-Syn using recombinant DNA approach[55], [56]. The NAcα-Syn was expressed by co-transformation of the plasmid encoding for α-Syn with the pNatB plasmid which encodes for the fission yeast NatB complex [56], [57]. NatB is an acetylase that allows N-terminal acetylation of eukaryotic proteins at N-terminal residues (Met-Glu, Met-Gln, and Met-Asp) when expressed in E.Coli [58]. We purified the proteins via osmotic shock followed by ion-exchange and size exclusion chromatography to a final >95% purity (Figure S1). Intact protein mass spectrometry confirmed the correctness of the NH2α-Syn with MW of 14,460 Da and revealed a 42-Da increase in the mass of NAcα-Syn (MW 14,502 Da) which corresponds to a single acetyl group, confirming complete N-terminal acetylation (Figure S1).

We verified the ability of NAcα-Syn to bind stoichiometric amounts of Cu(II) similar to the NH2α-Syn which forms a 1:1 redox-active complex [27], [39]. NH2α-syn and NAcα-syn were incubated with Cu(II) (protein: Cu(II) ratio 1.2:1 (mol/mol), 20 min, 25°C) and unbound Cu(II) was removed using 3-kDa MWCO centrifugal membrane filters. ICP-MS analysis showed that >97% of Cu(II) was bound to both forms, confirming that N-terminal acetylation does not affect Cu(II) binding under the condition used (Table S1). As the high affinity N-terminal Cu(II) binding site is abolished in NAcα-syn, Cu(II) is expected to bind to the lower-affinity site 2 centered at His50 [38].

We subsequently determined how N-terminal acetylation affects the redox properties of α-Syn. α-Syn participates in dopamine metabolism by facilitating the assembly of SNARE complexes and contributes to dopamine synthesis, vesicle uptake, and storage [10], [11], [59]. Dopamine is synthesized in the cytoplasm of dopaminergic neurons where it is sequestered into synaptic vesicles. Dysregulation of its metabolism or defects in its compartmentalization lead to abnormally high cytoplasmic dopamine concentrations. As a consequence, dopamine undergoes auto-oxidation with concomitant formation of toxic molecules including free radicals and reactive quinones [59]-[61]. In the first step of the oxidation pathway, dopamine auto-oxidation leads to formation of dopamine quinone which spontaneously converts into leukoaminochrome. The latter oxidizes to aminochrome and indole-5,6-quinone, eventually leading to the formation of neuromelanin. If not tighly controlled, these reactions promote cellular toxicity via ROS generation [60], [61]. Cu(II) binding to non-acetylated α-Syn can catalyze the first step of dopamine oxidation to dopamine ortho-quinone, coupled to α-Syn oxidation and formation of soluble oligomers [26], [27]. These processes are expected to contribute to the loss of dopaminergic transmission in substantia nigra neurons observed in PD. The dopamine oxidase activity of NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) remain to be extablished.

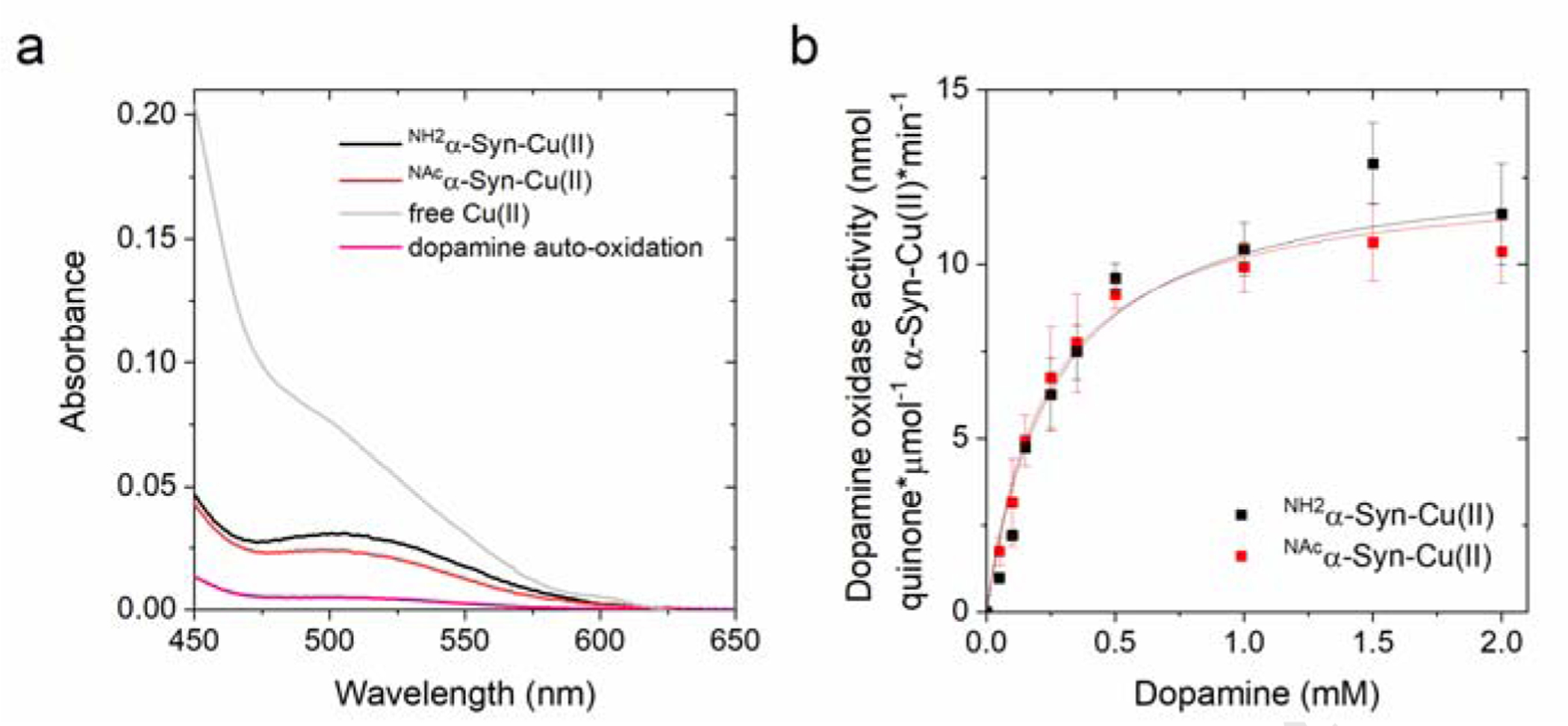

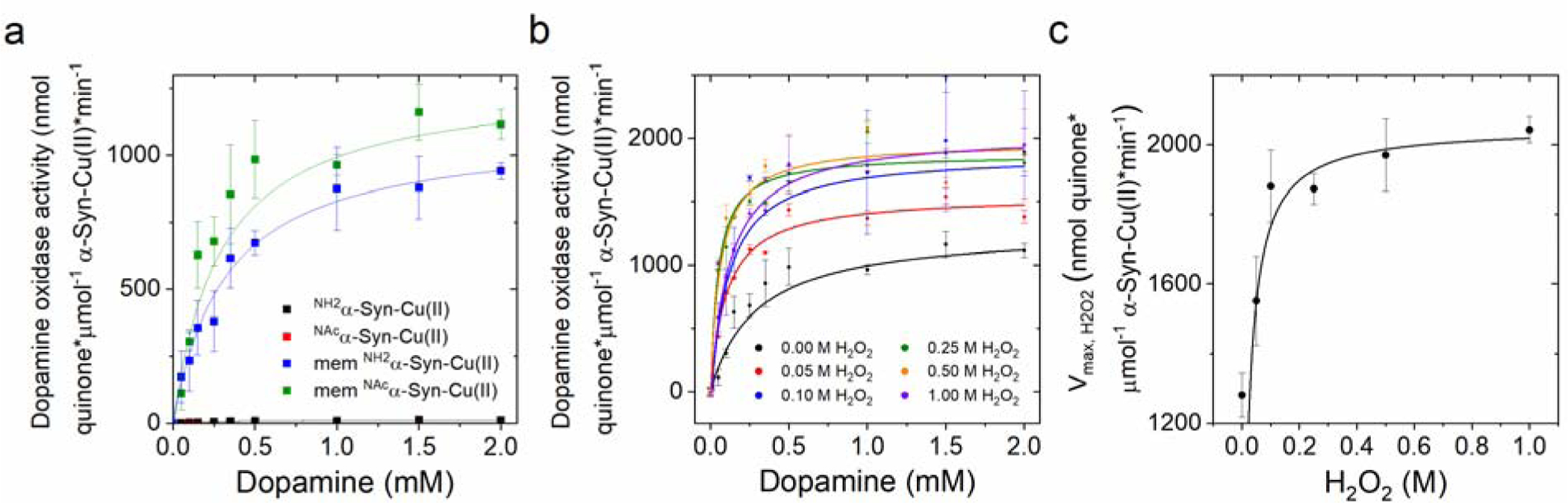

We investigated the catechol oxidase activity towards dopamine of NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) complexes using the colorimetric probe 3-methyl-2-benzothiazolinone hydrazone (MBTH). MBTH reacts with the dopamine ortho-quinone to form a red product that can be quantified by absorption spectrocopy (ε500=32,500 M−1cm−1) [62], [63]. Initial analysis of absorption spectra of MBTH-adduct formation with dopamine ortho-quinone demonstrated that both NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) efficiently catalyze the metal-centered catechol oxidase activity when compared to aerobic dopamine auto-oxidation (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) Absorption spectra recorded after the reaction of NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM; black), NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM; red), or free Cu(II) (10 μM; gray) with dopamine (1 mM) in 20 mM N-ethylmorpholine/100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 at 25°C, in the presence of MBTH (2 mM). Auto-oxidation of dopamine (1 mM) is plotted in pink. (b) Concentration-dependent dopamine oxidase activity of NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM; black) or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM; red) in 20 mM N-ethylmorpholine/100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, determined using MBTH (2 mM) to quantify the dopamine ortho-quinone formed after 120 s reaction (25°C).

We determined the dopamine oxidation rates as a function of substrate concentration (0 – 2.0 mM dopamine) by incubating NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM) with dopamine and followed the reaction for 120 s through quantification of dopamine ortho-quinone formed upon reaction with 2 mM MBTH. A hyperbolic dependency as a function of dopamine concentration was observed, indicative of a metal-centered catalytic mechanism. Data were fitted using a Michaelis-Menten equation and the catalytic parameters extrapolated (Figure 2b and Table 1). The analysis revealed Vmax values of 14.2 ± 2.5 and 12.5 ± 0.6 nmol quinone*μmol−1 α-Syn-Cu(II)*min−1 for NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn, respectively, and Km values of 0.30 ± 0.00 and 0.23 ± 0.03 mM, respectively. These kinetics parameters indicate that N-terminal acetylation does not affect the catechol oxidase activity of α-Syn and suggest that the shift in the Cu(II) coordination environment consequent to N-terminal acetylation generates species still possessing catechol oxidase activity . Notably, α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes show an oxidase activity within the same order of magnitude as free Cu(II) (Vmax= 17.3 ± 0.28 nmol quinone*μmol−1 α-Syn-Cu(II)*min−1; Km = 0.04 ± 0.01 mM). Thus, on one hand, the analysis reveals that Cu(II) binding to α-Syn can partially quench the redox reactivity of unbound Cu(II) and thus act as a protecting factor from free Cu(II) toxicity; on the other hand, the formation of α-Syn-Cu(II) still results in redox-active species that show detrimental dopamine oxidase reactivities and can contribute to toxicity in the physiological context.

Table 1.

Michaelis-Menten analysis of the dopamine oxidase activity of soluble or membrane-bound NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) determined using MBTH (2 mM) in 20 mM N-ethylmorpholine/100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4.

| VMAX, DOPAMINE (nmol quinone*μmol−1α-Syn Cu(II)*min−1) |

KM, DOPAMINE (mM) | |

|---|---|---|

| NH2α -Syn-Cu(II) | 14.2 ± 2.5 | 0.30 ± 0.00 |

| NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) | 12.5 ± 0.6 | 0.23 ± 0.03 |

| mem NH2a-Syn-Cu(II) | 1094.0 ± 22.5 | 0.32 ± 0.03 |

| mem NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) | 1281.6 ± 63.6 | 0.29 ± 0.05 |

MBTH has been extensively utilized to investigate the reactivity of catechol oxidases and quinone formation. Its chromophore properties allow optimal dopaquinone quantification for relative comparison of the reactivities in α-Syn soluble vs. membrane-bound forms (see below). Previous investigations revealed that α-Syn-Cu(II) model complexes can display overall different reaction rates in the presence or absence of MBTH. MBTH can promote a fast reduction of Cu(II) (the initial reaction to generate Cu/O2 reactive species upon O2 binding to Cu(I) and activation), increasing the initial rate of the oxidation process. In the absence of MBTH, catechols can substitute MBTH in the Cu(II)-to-Cu(I) reduction step [64]. To confirm that the dopamine oxidase reactivity in NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) is mantained also in the absence of MBTH, the oxidase activity was quantified by dopaminochrome detection (ε475 =3,700 M−1cm−1) [65], obtained through dopamine oxidation to dopaquinone (the rate limiting step) and further rapid conversion to dopaminochrome, at substrate concentrations close to saturation (dopamine=2 mM). The results confirmed that, despite the overall rates are partially reduced in the absence of MBTH, the overall oxidation rates are in a similar order of magnitude and follow the same order for free Cu(II) and α-Syn-Cu(II) forms as determined with MBTH (Figure S2, see also below for membrane-bound forms). Thus, in the presence of physiological reducing agents, α-Syn-Cu(II) possesses dopamine oxidase activity.

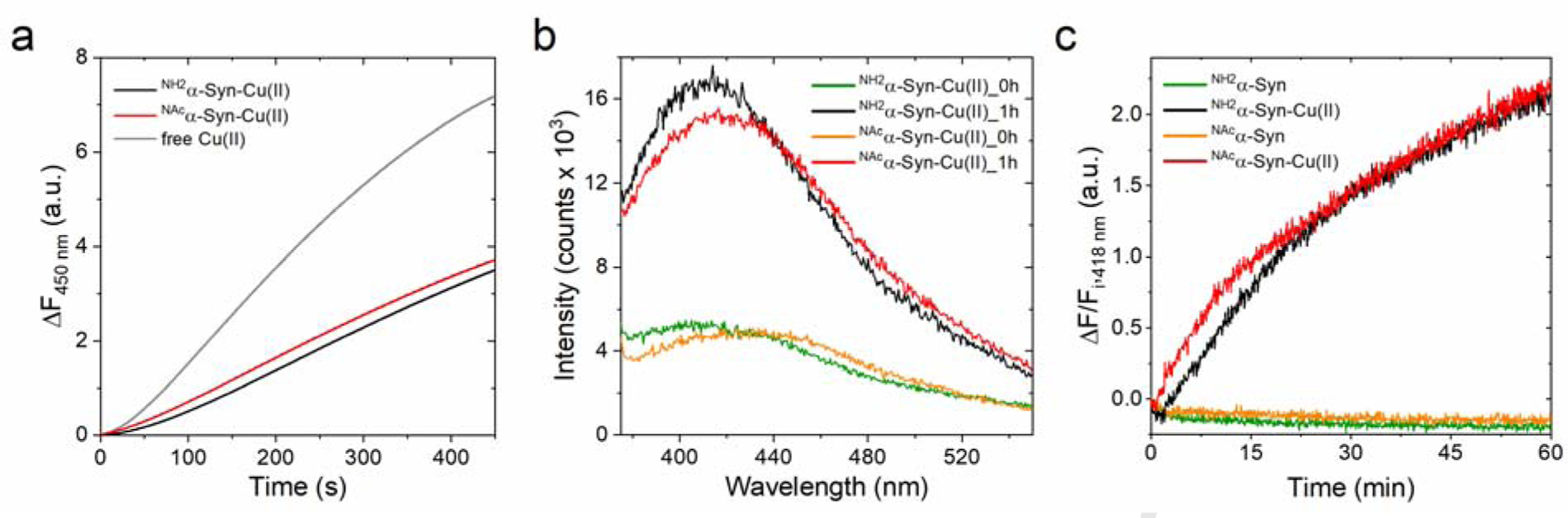

In the presence of molecular oxygen and biological reducing agents such as ascorbate, copper can activate oxygen and catalyze ROS radical production to generate peroxyl radical (HO2•), superoxide radical anion (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (HO•) through redox-cycling via Fenton and Haber Weiss-like reactions [66]. Physiologically, ascorbate is present in the central nervous system (CNS) in high concentrations reaching up to 10 mM in neurons. To determine ROS production catalyzed by α-Syn-Cu(II), we utilized the fluorescent reporter probe 3-coumarin carboxylic acid (3-CCA) and investigated the effect of N-terminal acetylation to the ability of the α-Syn-Cu(II) to catalyze ROS production. 3-CCA scavenges hydroxyl radicals to form the fluorescent product 7-OH-3-CCA (λEx=395nm, λEx=450nm). Because of the non-fluorescent nature of 3-CCA and its high hydroxylation rate constant, the detection of 7-OH-CCA allows real-time measurements of the kinetics of hydroxyl radical generation by α-Syn complexes. We followed the kinetics of formation of hydroxyl radical in the presence of NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (5 μM) and ascorbate (600 μM), and compared it to the rate of catalysis by free Cu(II). Analysis of the fluorescence traces revealed that both forms efficiently catalyze ascorbate-driven hydroxyl radical production at similar rates, which are approximately half of the ones catalyzed by free Cu(II). Thus, N-terminal acetylation results in NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) complexes that can partially quench and protect from the more deleteriuos reactivity of free Cu(II) redox-cycling (Figure 3a), but at the same time can still efficiently and detrimentally catalyze ROS generation through copper redox-cycling and thus mediate toxic reactivities.

Figure 3.

(a) Ascorbate-driven hydroxyl radical production by Cu(II) (5 μM; gray), NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) (5 μM; black), or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (5 μM; red) in the presence of ascorbate (600 μM) and 3-CCA (400 μM), determined by monitoring the formation of the fluorescent product 7-OH-CCA for 450 s at 37°C (λex=395 nm; λem=450 nm). (b) Dityrosine emission spectra (λex=325 nm) recorded forNH2α-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM; green and black) and NAcα-Syn (10 μM; orange and red) before and after 1-h reaction with 1 mM ascorbate (37°C). (c) Kinetic traces monitoring dityrosine formation at 418 nm (λex=325 nm) in NH2α-Syn (green), NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) (black), NAcα-Syn (orange), and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (red). Dityrosine formation is reported as the difference between final and initial fluorescence at 418 nm (ΔF) over the initial fluorescence (Fi).

Catalytic ROS production by α-Syn-Cu(II) results in oxidative modification of amino acid side chains in α-Syn, including the generation of cross-linked species through dityrosine covalent bridges [26], [55], [67], [68]. Dityrosine cross-links form by ortho-ortho coupling of two Tyr39 residues in the presence of oxygen and reducing agent ascorbate, resulting in homodimers that can act as a seed for fibril formation [68]. This process was proposed to occur through copper-oxygen electron transfer resulting in the abstraction of the phenolic hydrogen, followed by radical tautomerism in the aromatic ring resulting in the formation and subsequent coupling of tyrosyl radicals to form dityrosine cross-links [55]. Abeyawardhane et al. revealed that the long range of interaction involving His50 and N-terminus is required to stabilize the Cu(I)/Cu(II) intermediate for the copper-oxygen reactivity to take place [55]. To set the basis for a comparison with membrane-bound α-Syn forms (see below), we also verified here the effect of N-terminal acetylation on α-Syn dityrosine cross-linking by comparing it to the soluble NH2α-Syn form. Dityrosine shows a characteristic fluorescence emission with a maximum at 418 nm (λex=325nm). We initially monitored dityrosine formation by incubating 10 μM NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) in the presence 1 mM ascorbate for 1 h. The recorded emission spectra showed a prominent increase in the emission band characteristic of dityrosine which was absent in NH2α-Syn or NAcα-Syn controls in absence of Cu(II) (Figure 3b). In agreement, analysis of the reaction kinetic traces at 418 nm revealed a progressive increase in the dityrosine emission signal, absent in the control samples, consistent with metal-dependent cross-linking process (Figure 3c). Thus, in agreement with the observations above and previous studies, N-terminal acetylation does not appear to significantly alter the redox properties of α-Syn-Cu(II), resulting in species that catalyze detrimental modifications leading to gain of toxic functions.

Membrane insertion exacerbates the dopamine oxidase activity of α-Synuclein-Cu(II)

In dopaminergic neurons, α-Syn exists in equilibrium between unfolded soluble forms and ampiphatic α-helical membrane-bound species, formed upon interaction of the seven imperfect amino acid repeats (KXKEGV) in its sequence with lipid vesicles [12]-[14]. This interaction is consistent with the physiological role of α-Syn in maintaining functional presynaptic dopamine vesicles. However, the redox properties of α-Syn-Cu(II) inserted in lipid bilayers remain elusive. We aimed to determine how α-Syn-Cu(II) membrane insertion affects its redox activites when compared to soluble forms. Membrane-bound non-acetylated α-Syn (NH2α-Syn) binds Cu(II) with the N-terminal amine nitrogen, the backbone amide, the carboxylate side chain of Asp2 and a water molecule as the coordinating ligands (Figure 1c). His50 is not involved in the coordination shell because it is separated from the N-terminus by the helical portion inserted in the membrane [41]. Moreover, we aimed to determine the effect of N-terminal acetylation to the reactivity of membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) since both the N-terminal amine group and His50 are not availble for coordination and Cu(II) binding might shift to the lower affinity C-terminal site (Figure 1e).

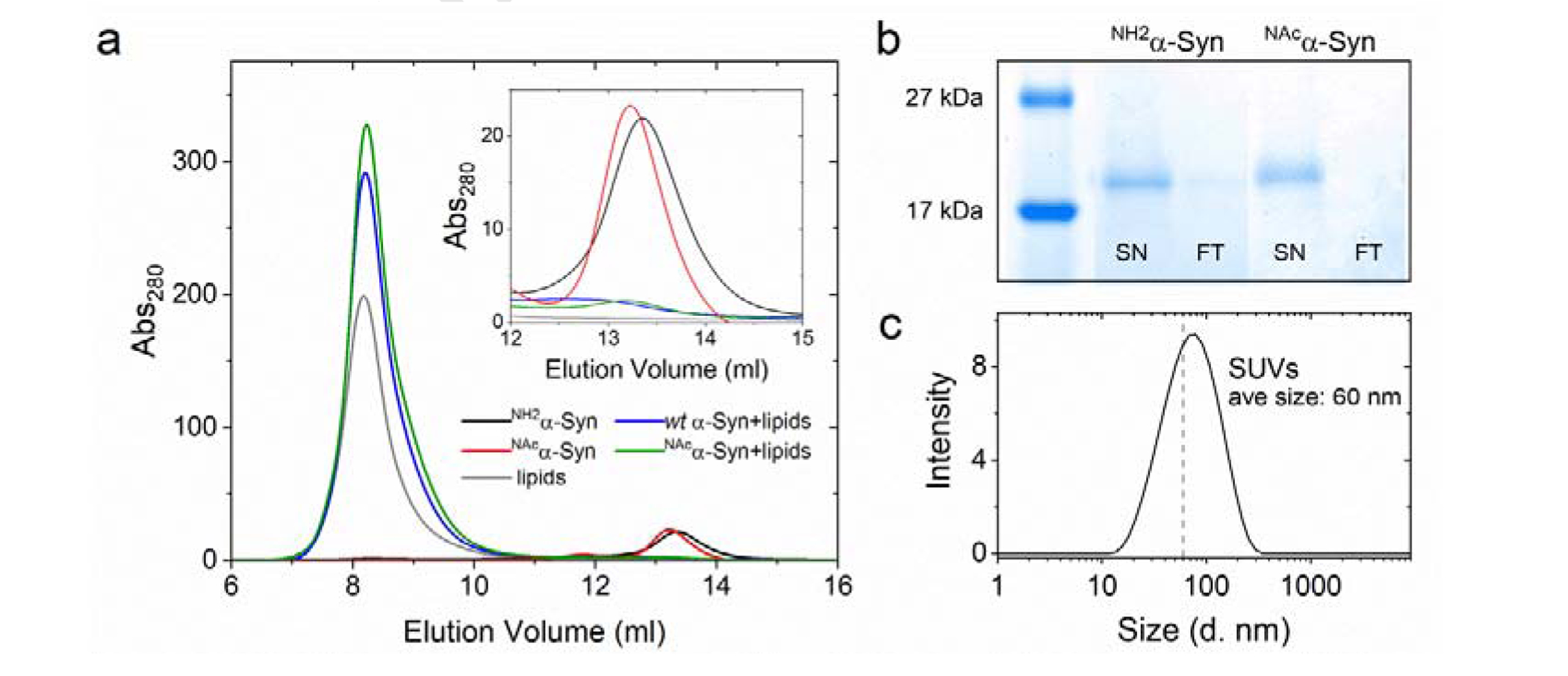

To model α-Syn interactions with lipid membranes, we inserted soluble α-Syn into small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) prepared using a mixture (70:30 w/w) of phosphatidylcholine (zwitterionic) and phospatidylgycerol (negatively charged). This lipid composition reduces the interaction of Cu(II) with lipid head groups [41]. Dynamic light scattering analysis revealed the average vesicle size of 60 nm with a mean polydispersity index of 0.233 (Figure 4c). We used a protein:lipid molar ratio of 1:500 (mol/mol) which was shown to allow α-Syn-Cu(II) formation [41]. Complete α-Syn insertion into lipid bilayers was verified by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 10/300 column) and SDS-PAGE upon separation of vesicles from the supernatatnt using 50-kDa MWCO filters (Figure 4a–b). SEC peak integration revealed that the soluble monomeric NH2α-Syn and NAcα-Syn peaks (~13.3 ml), upon membrane-binding, completely shifted to the column void volume (~8.2 ml) where lipid vesicles elute (Figure 4a and Table S2). Consistent with previous reports [56], although N-terminal acetylation causes a localized increase in helicity in the N-terminal region of α-Syn, it does not significantly affect its structure and membrane-binding to SUVs and synaptosome-derived vesicles.

Figure 4.

(a) Size exclusion chromatogram monitoring membrane insertion of soluble NH2α-Syn (15 μM; black, blue after insertion) or NAcα-Syn (red, green after insertion) using a Superdex 200 column. Lipids (gray) elute at the void volume (~8.2 ml) while soluble α-Syn elutes at 13.3 ml (black and red). Inset: Enlarged portion of the chromatogram showing soluble α-Syn elution. (b) SDS-PAGE of membrane-bound NH2α-Syn and NAcα-Syn, generated after removing soluble protein using 50-kDa MWCO filters (SN: supernatant; FT: filtrate). (c) Dynamic light scattering size distribution analysis of lipid vesicles (0.1 mg/ml lipids) generated by sonication, indicating the formation of SUVs.

To confirm that α-Syn membrane insertion does not prevent Cu(II) binding, we titrated Cu(II) into membrane-bound NH2α-Syn and NAcα-Syn (protein: Cu(II) ratio 1.2:1, mol/mol). We subsequently separated vesicles from unbound Cu(II) and soluble α-Syn-Cu(II) by centrifugation using 50-kDa MWCO filters. ICP-MS analysis showed that >97% of Cu(II) is bound to both membrane-bound NH2α-Syn and NAcα-Syn (Table S1). However, Cu(II) can also bind to lipid phosphate head groups in the absence of α-Syn (Table S1). We thus confirmed Cu(II) binding to membrane-bound α-Syn by EPR spectroscopy. X-band EPR spectra for NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (500 μM) were recorded at 10 K and compared to lipid-Cu(II) complexes (Figure S3). Consistent with with previus reports [41], all species presented axial spectra with lipid-Cu(II) complexes showing a significant signal downshift in both the perpendicular and parallel regions when compared to α-Syn-Cu(II), confirming the formation of membrane-bound stoichiometric α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes (Figure S3).

We subsequently determined the effect of membrane insertion on the dopamine oxidase activity of α-Syn-Cu(II) to generate the dopamine ortho-quinone using MBTH. Initial analysis of absorption spectra of MBTH-adduct formation with dopamine ortho-quinone revealed a drastic increase in the amount of generated ortho-quinone compared to soluble α-Syn-Cu(II), providing evidence for a dramatic potentiation of catechol oxidase-like activity upon α-Syn membrane insertion. Analysis of dopamine oxidation rates as a function of substrate concentration for membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) also revealed an hyperbolic dependency as observed for soluble forms (Figure 5a). Michaelis-Menten analysis resulted in Vmax values of 1094.0 ± 22.5 and 1281.6 ± 63.6 nmol quinone*μmol−1 α-Syn-Cu(II)*min−1 for NH2α-Syn and NAcα-Syn, respectively, and Km values of 0.32 ± 0.03 and 0.29 ± 0.05 mM, respectively (Table 1). Thus, membrane insertion drastically increases the dopamine oxidase acitvity of α-Syn-Cu(II) resulting in complexes possessing similar Km but Vmax values that are approximately one to two two orders of magnitude higher than the corresponsing soluble forms and higher even than Cu(II) bound to lipids (Vmax =992.4 ± 106.7 nmol quinone*μmol−1 (II)*min−1; Km=0.93 ± 0.15 mM; see also Figure S2 for measurements in the absence of MBTH). Moreover, N-terminal acetylation appear to further increase the apparent oxidase catalityc efficiency compared to non-acetylated α-Syn (NH2α-Syn) when bound to membranes. Overall, these resuslts indentify a dramatic detrimental effect resulting from α-Syn membrane insertion and interaction with Cu(II).

Figure 5.

(a) Concentration-dependent dopamine oxidase activity of soluble or membrane-bound NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM; black and blue, respectively) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM; red and green, respectively) in 20 mM N-ethylmorpholine/100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, determined using MBTH (2mM) to quantify the dopaquinone formed. Values were obtained after 120 s reaction for soluble forms and 20 s for the membrane-bound forms (25°C). (b) Concentration-dependent dopamine oxidase activity of membrane-bound NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM) in 20 mM N-ethylmorpholine/100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 at increasing H2O2 concentrations (0 – 1 M), determined using 2 mM MBTH to quantify the dopaquinone formation (20 s, 25°C). (c) Michaelis-Menten analysis to determine Vmax, H2O2 as a function of H2O2 concentrations.

We also determined dopamine oxidase rates as a function of dopamine concentrations at progressively increasing H2O2 concentrations. Addition of H2O2 resulted in a hyperbolic dependency of the rates of dopamine oxidation still consistent with a catalytic metal-centered oxidation and resulted in progressively increasing rates up to approx. 100 mM H2O2 (Figure 5b, Table S3). By analyzing the changes in apparent Vmax versus H2O2 concentrations, a Michaelis-Menten dependency was observed with Vmax, H2O2 of 2,050 ± 387 nmol quinone*μmol−1 α-Syn-Cu(II)*min−1 and Km, H2O2 of 0.08 ± 0.02 M (Figure 5c). The hyperbolic dependency thus suggests a direct involvement of peroxide at the metal center in the catalytic mechanism, when H2O2 is present. A catechol oxidase-like activity towards the catechol-like substrate, 1,2,3-trihydroxylbenzene (THB) was observed previously for the Aβ-Cu(II) complex [62], [69]. Aβ-Cu(II) was proposed to oxidize THB via formation of a transient dinuclear Cu(II) center via two-electron transfers to generate two Cu(I) and ortho-quinone products. The two Cu(I) can bind O2 to form a dinuclear Cu(II)-peroxo center, which oxidizes a second substrate to complete the catalytic cycle in a reaction cycle that mimics Type 3 Cu centers (typical of catechol oxidases). H2O2 can shunt the catalytic cycle, leading to a faster oxidation turnover. It should be noted that membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) forms show catalytic parameters (kcat= ~ 0.1–1.3 min−1, Km,dopamine= ~ 0.3 mM) that are in a similar range as other human catechol oxidases such as tyrosinase (e. g.: kcat= ~ 1.4–49.1 min−1; Km, L-Dopa= ~ 0.23–0.74 mM) [70], while being significantly less efficient than other catechol oxidases from plants [71]. Follow-up studies will be required to determine whether the molecular mechanism for catechol substrate oxidation by membrane-bound full-length α-Syn-Cu(II) proceeds through the expected mononuclear sites or via putative transient dinuclear α-Syn-Cu(II) centers, as proposed for Aβ-Cu(II). Nevertheless, our results reveal that membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes possess potentiated oxidative properties compared to the soluble counterparts and reveal the importance of membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) species in studying copper-mediated neurodegenerative processes.

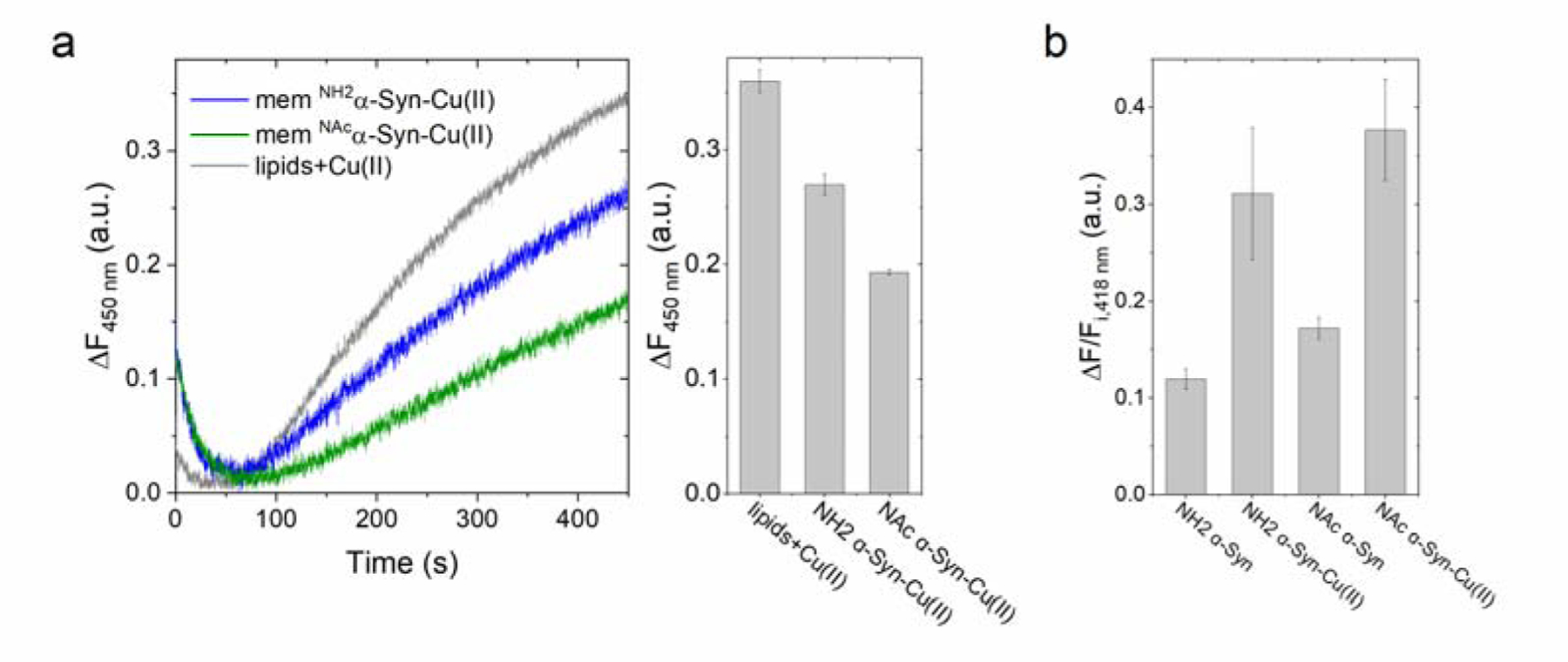

We also investigated the effect of membrane insertion in ascorbate-driven hydroxyl radical formation (with 3-CCA) and dityrosine formation (dityrosine fluorescence) of NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II). Despite lipids effectively quenching ROS and competing with the reporter probe 3-CCA, preventing a direct quantitative comparison with soluble forms, kinetic traces still revealed that both membrane-bound NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) can efficiently catalyze hydroxyl radical production (Figure 6a). In addition, dityrosine cross-link formation was observed by fluorescence spectroscopy to occur also in the membrane-bound forms, though to a lower extent (Figure 6b). Signal intensity reduction was observed, consistent with the knowledge that His50 enhances copper-oxygen reactivity towards dityrosine formation. A change in the Cu(II) binding mode which removes His50 from the coordination shell shifting Cu(II) biding to C-terminal sites result in a transition from predominantly intermolecular to intramolecular dityrosine cross-links [55]. However, also in this case, radical quenching by lipid molecules in the reaction investigated cannot be excluded.

Figure 6.

(a) Ascorbate-driven hydroxyl radical production of membrane-bound NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) (5 μM; blue), membrane-bound NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (5 μM; green), or Cu(II) bound to lipids (5 μM; gray), determined in the presence of 600 μM ascorbate and 400 μM 3-CCA by monitoring the formation of fluorescent product 7-OH-CCA (λex=395 nm; λem=450 nm; 450 s; 37°C.) (b) Ascorbate-driven dityrosine formation of membrane-bound NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (5 μM), determined by monitoring dityrosine fluorescence at 418 nm (λex=325 nm) upon incubation with 3 mM ascorbate for 3 h (37°C). Dityrosine formation is reported as the difference between final and initial fluorescence at 418 nm (ΔF) divided by initial fluorescence (Fi).

Overall, our work reveals a dichotomic “Yin and Yang” role for α-Syn-Cu(II). First, Cu(II)-binding to α-Syn can reduce and partially quench the redox reactivity of free Cu(II) thereby providing a line of protection under condition of uncontrolled Cu(II) homeostasis. On the other hand, α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes do not completely silence the Cu(II) redox reactivity and are capable of catalyzing detrimental redox processes. In our work, we demonstrate that, despite partially quenching the reactivity of free Cu(II), N-terminal acetylation and membrane insertion dramatically potentiate the catechol oxidase activity of α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes compared to α-Syn-Cu(II) soluble forms and involve a metal-centered Cu(II)/Cu(I) redox cycle. N-terminal acetylation plays a role in localization of the protein in the plasma membrane when compared to NatB-deficient cells which are more localized in the cytosol [72]. However, other than an increase in transient helical propensity at the N-terminus of the acetylated form, there is minimal change in the proteins’ hydrodynamic radius and long-range interactions. Moreover, both the non-acetylated and acetylated forms have similar aggregation propensities and ability to bind to synaptosomal membranes [56]. However, the Cu(II) coordination environment is altered upon N-terminal acetylation in soluble and membrane-bound forms. In soluble non-acetylated form, the high affinity site in the N-terminus involves the N-amino nitrogen in binding the Cu(II); however, in the soluble acetylated form, this site is blocked and Cu(II) binding shifts to a lower affinity site that includes His50 [38]-[40]. On the other end, characterization of Cu(I) binding to the acetylated α-Syn showed that Cu(I) is bound exclusively to the N-terminus with the N-terminal acetyl group, Met1, Asp2 and Met5 as source of ligands for binding [32]. Cu(I) is a softer ion and prefers coordination by soft bases such as cysteines and methionines. In the reactivities that we analyzed, copper cycles between oxidation states, and a coordination sphere that would allow for the stabilization of both states is expected. The long range of interaction involving His50 and N-terminus appears required to stabilize the Cu(I)/Cu(II) intermediate for the copper-oxygen reactivity to take place [55]. Therefore, in light of the comparable reactivity observed in both in acetylated and non-acetylated soluble forms, we assume similar Cu(I)/Cu(II) coordination shells involving His50 and possibly upstream (N-terminal) ligands that can stabilize this Cu(I)/Cu(II) intermediate.

Contrarily, we show in our work that membrane-binding drastically increases the dopamine oxidase activity of α-Syn-Cu(II), suggesting potential differences in the dopamine oxidation reaction mechanism. In the membrane-bound NH2α-Syn-Cu(II), Cu(II) is bound to the N-terminal residues with the same binding affinity (Kd ~ 0.1 nM) as the soluble form. Cu(II) binding does not alter the α-helical conformation of α-Syn when interacting with membranes and its energetics of membrane release [41]. Unlike the soluble NH2α-Syn form, membrane insertion removes His50 from the Cu(II) coordination shell. On the other hand, the membrane-bound NAcα-syn-Cu(II) is not well studied but similar to the NH2α-Syn, His50 also cannot contribute in the Cu(II) coordination shell in this form. The absence of His50 in the coordination appear to correlate with the potentiation of the catechol oxidase reactivity of the membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes. Moreover, in the membrane-bound NAcα-Syn, the blocking of the N-terminal amino group by acetylation resulted in further increase in the catechol oxidase activity compared to NH2α-Syn. A possible shift to Cu(II) coordination in the low affinity C-terminal site, might contribute to this effect [39]. Overall, this suggests that the shift in Cu(II) coordination environment that remove His50 from the coordination shell is responsible for an increased catechol oxidase activity.

To note, the coordination at His50 has been considered important since the discovery of the H50Q mutant in familial forms of PD. Interestingly, evidence show that in the presence of Cu(II), the H50Q mutant aggregates faster than the wild-type and forms amorphous instead of fibrillar aggregates [73]. This suggests that Cu(II) binding in His50 plays a role in modulating aggregation, possibly by inducing a local turn-like structure that favors β-sheet nucleation, whereas its absence leads to Cu(II)-induced aggregation that forms amorphous aggregates [74]. Moreover, substitution of the His50 residue with a disease relevant Gln50 mutation abolishes intermolecular dityrosine cross-linking and limits the copper-oxygen promoted cross-linking to the C-terminal region [55]. Such a dramatic change in reaction behavior establishes a role for His50 in facilitating intermolecular cross-linking. Future work addressing the effect of His50 mutation on the dopamine oxidase activity will provide additional insight of His50 coordination in the redox properties of membrane-bound NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) complexes.

Zn7metallothionein-3 targets soluble and membrane-bound α-Synuclein-Cu(II) complexes, abolishing their redox activity.

Our work substantiates that α-Syn can partially quench and protect from the toxicity of free Cu(II) [42]. However, copper binding to amyloidogenic peptide/proteins, including α-Syn, can still contribute to neurodegenerative processes in light of their demonstrated redox reactivities. Considering the role played by MT-3 in maintaining copper homeostasis and preventing aberrant copper-protein interactions, we investigated the reactivity between Zn7MT-3 and NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) or NAc -Syn-Cu(II). Zn7MT-3 occurs both intracellularly and extracellularly, and was initially discovered to be able to quench the toxic reactivity of the Aβ-Cu(II) complexes in AD by scavenging Cu(II), reducing it to Cu(I) with concomitant formation of intramolecular disulfides, and binding Cu(I) in a redox-stable cluster, thereby abolishing ROS production [51]. This reactivity was also demonstrated to occur with soluble NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) where Zn7MT-3 was shown to completely quench dopamine oxidation, ROS production, α-Syn oxidation and oligomerization [26].

With the evidence that α-Syn exists physiologically in acetylated and membrane-bound forms and the discovery that membrane insertion exacerbates the dopamine oxidase activity of α-Syn-Cu(II) compared to soluble forms, we sought to determine whether soluble Zn7MT-3 can also target these complexes and abolish their toxic reactivities.

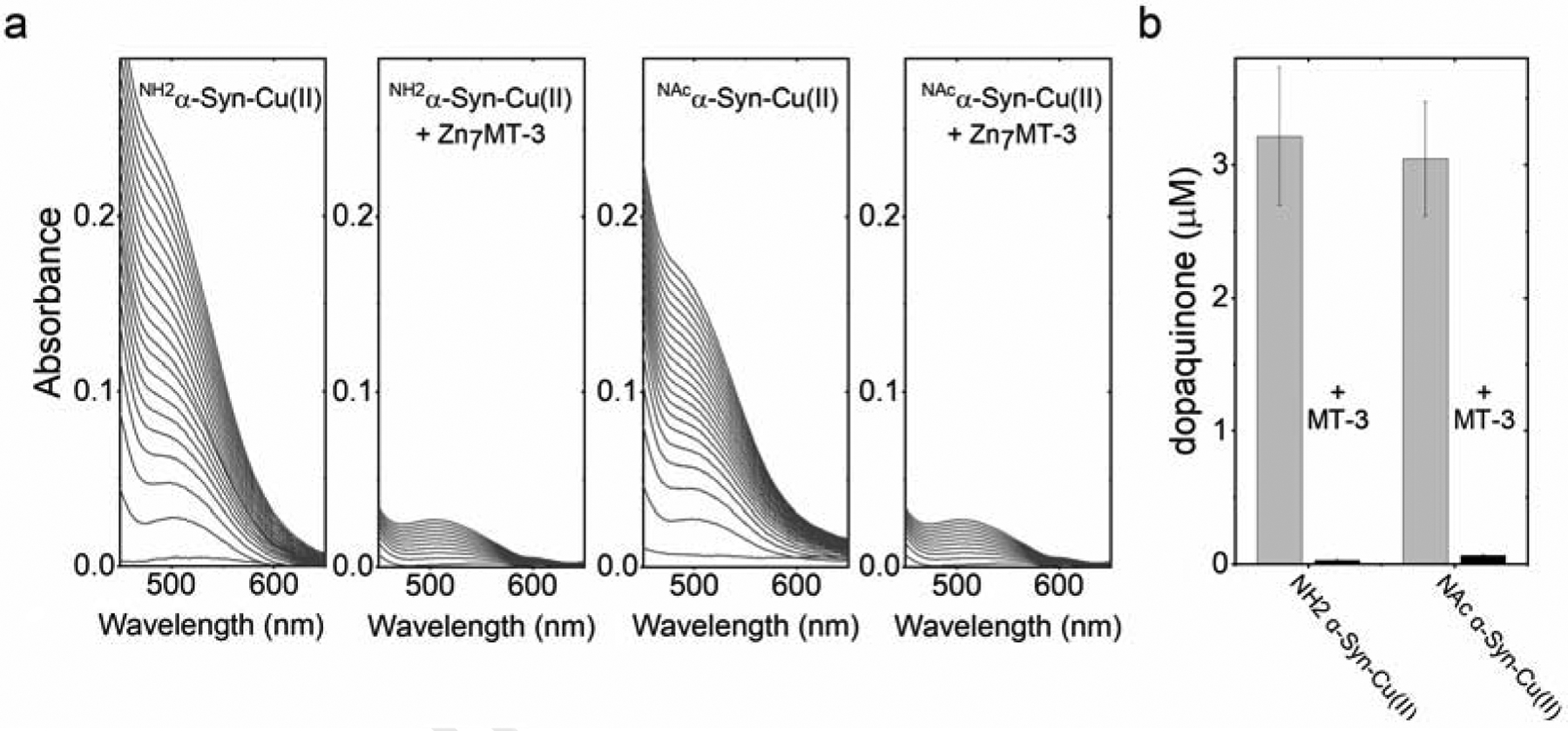

We first determined the effect of Zn7MT-3 on the dopamine oxidase activity of the soluble α-Syn-Cu(II) forms. We reacted the α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes with Zn7MT-3 (0.25 eq., 1 h, 25°C) and followed dopamine ortho-quinone formation using 2 mM MBTH upon incubation with 1 mM dopamine. By analyzing the absorbance development for the MBTH-quinone adduct at 450–650 nm for 100 min, we observed that that dopamine oxidase activity of both NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) was completely abolished in the presence of Zn7MT-3 and reverted to the background levels of dopamine auto-oxidation (Figure 7a and Figure S4).

Figure 7.

(a) Catalytic dopamine (1 mM) oxidation by NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM) in 20 mM N-ethylmorpholine/100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, in the presence 2 mM MBTH (100 min, 25°C). The dopamine oxidase activity is quenched upon addition of Zn7MT-3 (0.25 eq., 1 h) prior to the addition of dopamine. (b) Quenching of the dopamine oxidase activity of membrane-bound NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM) upon reaction with Zn7MT-3 (0.25 eq.). The dopaquinone formed was quantified after 20 s (25°C) using 2 mM MBTH.

Since MT-3 is a soluble metalloprotein, the demonstrated reactivity with soluble α-Syn-Cu(II) does not allow extrapolation on whether this reaction occurs when α-Syn is inserted into lipid bilayers. We thus conducted similar dopamine oxidation experiments with the membrane-bound forms of α-Syn-Cu(II) upon reaction with Zn7MT-3. Upon incubation of the membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) forms with Zn7MT-3 (4:1 α-Syn: MT-3, mol/mol) for 1 h before dopamine addition, the formation of the dopamine ortho-quinone monitored using 2 mM MBTH was also completely abolished. The results reveal that Zn7MT-3 can also target and silence the dopamine oxidase activity of membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes (Figure 7b).

To verify the molecular mechanism underlying the quenching effect, we investigated whether Zn7MT-3 can remove Cu(II) from α-Syn-Cu(II) and whether a redox reaction is involved in the process. Pearson HSAB (Hard and Soft Acid and Bases) theory predicts that Cu(II) would preferentially bind to “harder” N/O-ligands, whereas Cu(I) to “soft” thiolate ligands like the cysteine thiolate ligands contained in MTs. We thus verified whether Zn7MT-3 can reduce Cu(II) and bind it as Cu(I) in its N-terminal β-domain to form Cu(I)4Zn4MT-3 as previously demonstrated for soluble Aβ-Cu(II), NH2α-Syn-Cu(II), and PrP-Cu(II) complexes [26], [51], [52].

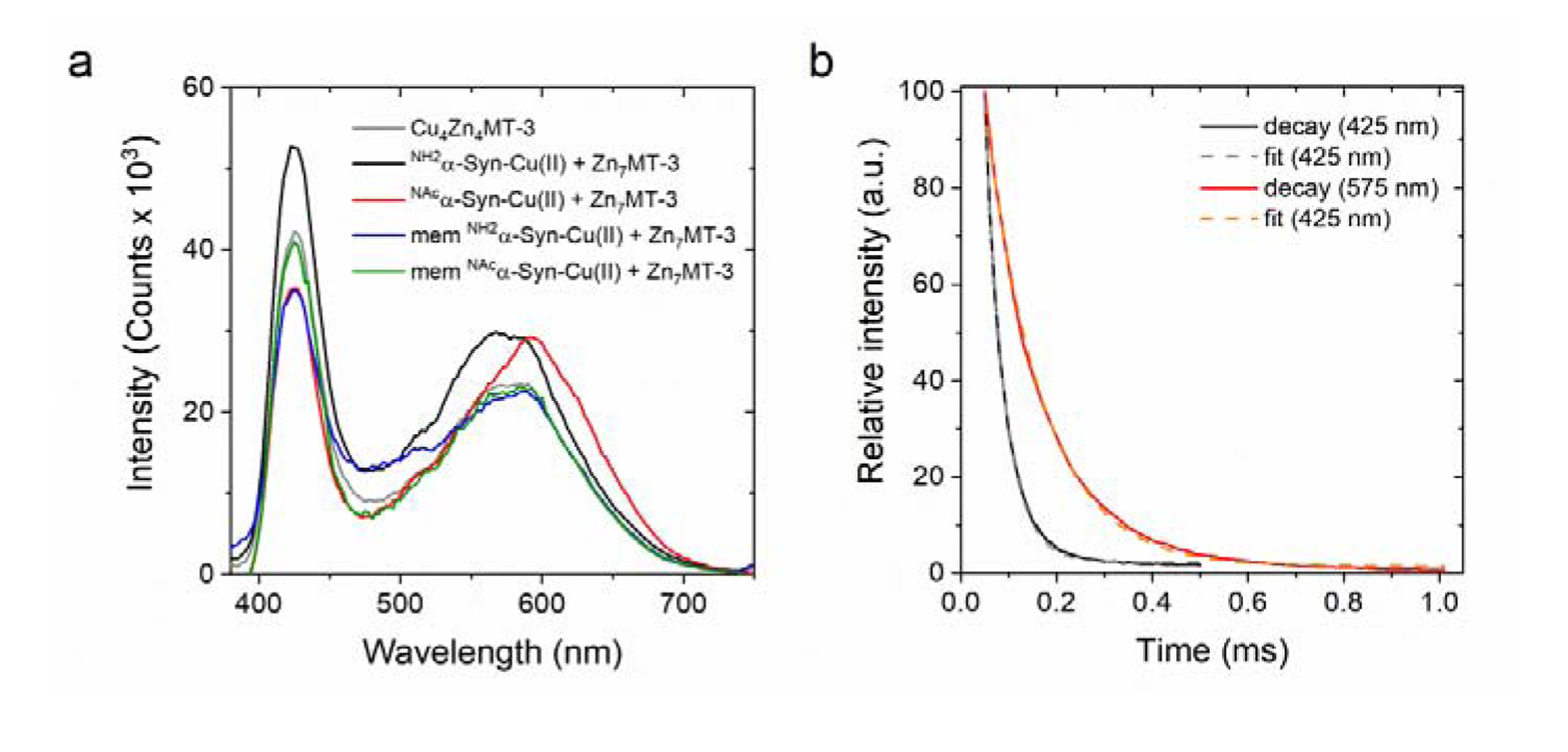

At 77 K, Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 shows a characteristic luminescence emission spectrum (λex=320 nm) with two emissive bands centered at 425 nm and 575 nm with lifetimes (τ) of 40 and 120 μs, respectively, that are diagnostic of the formation of a Cu(I)4 thiolate cluster in MT-3 structure [49], [75]. The presence of two emissive bands in Cu(I)4 clusters is correlated with short internuclear Cu···Cu distances (<2.8 Å). The low energy band at 575 nm is assigned to a triplet charge transfer (CT) origin, while the high energy band at 425 nm to a cluster-centered (CC) origin [49]. The presence of the high-energy emissive band indicates that peculiar metal-metal interactions in this cluster exist allowing a d10-d10 orbital overlap and metal-metal bonding character, which results in an exceptional stability toward molecular oxygen (unusual for Cu(I)-thiolate clusters) and is critical for redox silencing [49].

Upon reaction of NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM) with Zn7MT-3 (2.5 μM) for 1 h, the samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and emission spectra recorded at 77 K (λex=320 nm). The presence of two emission bands that match in position and lifetimes (Figure 8, Table S4) with the ones of Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 are diagnostic of Cu(II) removal from α-Syn-Cu(II) and concomitant reduction to Cu(I) to form a redox-silent Cu(I)4 cluster in Cu(I)4Zn(II)4 MT-3. The same characteristic Cu(I)4Zn(II)4 emission spectra at 77 K was also obtained upon reaction between membrane-bound NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) and Zn7MT-3, confirming that the Cu(I)4 cluster in MT-3 β-domain was formed also in the case of membrane-bound α-Syn forms (Figure 8, Table S4). To quantitatively verify the metal scavenging reaction, we quantified the Cu(I) bound to MT-3 by using 50-kDa MWCO filters to separate membrane-bound α-Syn vesicles (supernatant) from MT-3 (filtrate) and subsequently analyzed metal content by ICP-MS. In agreement with the luminescence spectra, ICP-MS analysis revealed >80% of Cu(I) in the filtrate bound to MT-3. Moreover, evidence of a partial metal swap reaction between α-Syn SUVs and MT-3 was obtained by analyzing the zinc content in the two fractions. The presence of zinc in the high molecular weight fraction upon the swap reactions confirmed that Zn(II) is released upon Cu(I) binding in MT-3 resulted in Zn(II) binding to α-Syn SUVs (Figure S5).

Figure 8.

(a) Low-temperature (77 K) luminescence emission spectra of the products of the reaction (1 h; 25°C) between soluble and membrane-bound NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM; black and blue, respectively) or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM; red and green, respectively) with Zn7MT-3 (2.5 μM). The reference spectra of Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 (2.5 μM) is plotted for comparison (gray). (b) Emission lifetime determination of the product of reaction between membrane-bound NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) and Zn7MT-3 at 425 nm (black) and 575 nm (red). Lifetime values were determined by fitting using single exponential decay function (gray and orange, respectively).

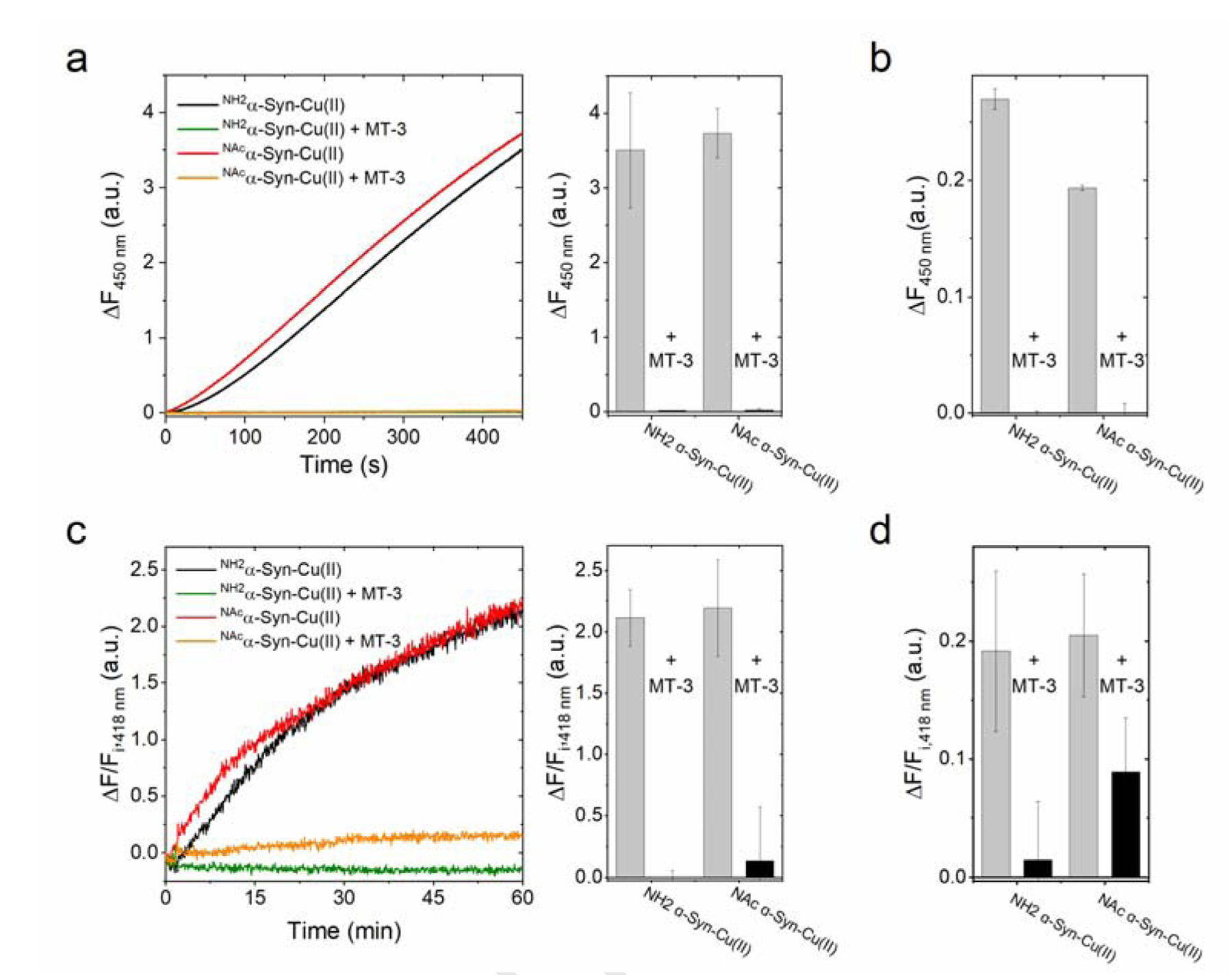

To further verify that Cu(II) reduction and scavenging by Zn7MT-3, generating the redox-inert Cu(I)4Zn4MT-3, abolishes the α-Syn Cu(II) redox properties, ROS production and concomitant tyrosine cross-linking were investigated. Upon incubation of soluble or membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes with Zn7MT-3 (0.25 eq.) and monitoring the hydroxyl radical production with 3-CCA in the presence of ascorbate (600 μM), no development of 7-OH-3-CCA fluorescence (λex=395 nm; λem=450 nm) was observed (Figure 9a–b). Similarly, upon reaction between Zn7MT-3 and soluble and membrane-bound forms of α-Syn-Cu(II), the formation of dityrosine in the presence of ascorbate (1 or 3 mM) was significantly reduced (Figure 9c–d). Thus, Zn7MT-3 is able to remove Cu(II) from soluble NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II), and membrane-bound NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) complexes, completely abolishing their reactivities.

Figure 9.

(a) Quenching of ascorbate-driven hydroxyl radical production of 5 μM soluble NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) (black) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (red) by 0.25 eq. Zn7MT-3 (green and orange lines, respectively) incubated for 1 h before reaction with 1 mM ascorbate. Hydroxyl radical production was monitored by following the formation of the fluorescent product 7-OH-CCA (λex=395 nm; λem=450 nm) for 450 s (37°C). (b) Hydroxyl radical quenching by Zn7MT-3 (1.25 μM) in the membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) forms (5 μM). (c) Quenching of ascorbate-driven dityrosine formation of soluble NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) (black) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (red) by Zn7MT-3 (green and orange lines, respectively), incubated for 1 h before reaction was initiated by addition of ascorbate (1 mM). Dityrosine formation was determined by monitoring dityrosine fluorescence at 418 nm (λex=325 nm) after 1 h reaction (37°C), reported as the difference between final and initial fluorescence (ΔF) divided by initial fluorescence (Fi). (d) Quenching of dityrosine formation by Zn7MT-3 (1.25 μM) in the membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) forms (5 μM), after following the reaction for 3 h upon the addition of ascorbate (3 mM). Values are corrected for ΔF/Fi, 418nm of membrane-bound α-Syn forms in the absence Cu(II).

Overall, our work demonstrated a protective effect of Zn7MT-3 from α-Syn-Cu(II) reactivity originating from the redox coupling of Cu(II)/Cu(I) and thiolate/disulfide pairs. The reaction allows Cu(II) scavenging and redox silencing of aberrantly bound copper to α-Syn-Cu(II) via formation of a redox-inert and oxygen-stable Cu(I)-thiolate cluster in MT-3. MT-3, which is highly expressed in neurons and possesses a higher selectivity bias and affinity for Cu(I) compared to other MT isoforms, is emerging as a major player in copper homeostasis in the CNS and acting as a gatekeeper in controlling aberrant metal-protein interactions [20], [23]. The MT-3 function in neurodegenerative processes has been implicated in light of its down-regulation in AD. MT-3 was discovered as growth inhibitory factor (GIF) deficient in the AD brain which prevents abnormal sprouting of neurons. Upon purification and sequencing, GIF was classified as belonging to MT family [45], [46]. Compared to ubiquitously expressed MT-1 and MT-2, in vivo metalation experiments confirmed its higher copper-thionein character [76]. Isoform-specific residues in MT-3, such as its unique CPCP motif in the β-domain, and the acidic hexapeptide insert in its α-domain have been identified to be critical in fine-tuning its selectivity bias towards copper. As consequence, less-stable Zn(II) clusters and more-stable Cu(I) clusters are formed in its β-domain when compared to MT-2 [50]. Its affinity towards Cu(I) (Kd =10−19 M) has been found to be correlating to the copper buffering range in cells, further supporting its gatekeeping role in controlling copper homeostasis in the brain.

MT-3 expression is found to be altered in a number of NDs, including PD [48]. In light of its protective role in metal-dependent neurodegenerative processes, MT-3 induction is currently investigated as a possible therapeutic option to control copper-induced neurodegenerative processes [23]. Roy et al. (2017) investigated the effect of small molecule compounds in inducing MT-3 expression and revealed that benzothialozone-2 can enhance MT-3 expression levels with minimal cytotoxic effects [77]. Moreover, dexamethasone was demonstrated to induce MTs expression and observed to suppress Cu(II)-mediated α-Syn aggregate formation in vivo [78]. Our work provides mechanistic evidence that MT-3 is capable of targeting all physiologically relevant α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes-the acetylated and membrane-bound forms. By removing Cu(II) from α-Syn and consequent reduction to Cu(I) to form a stable and redox-inert cluster, MT-3 abolishes deleterious redox chemistry catalyzed by α-Syn-Cu(II). As a result of this reaction, the dopamine oxidase activity is quenched and ROS production abolished, providing the molecular basis of the protective effect of MT-3 against Cu(II)-catalyzed α-Syn-Cu(II) reactions.

Conclusions

In this work, we investigated the redox reactivity of α-Syn-Cu(II) in the physiologically relevant acetylated and membrane-bound forms. While the redox reactivity of the soluble NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes has been previously shown to promote catalytic dopamine oxidation, ROS formation, and α-Syn aggregation [26], [27], the role of N-terminal acetylation and membrane insertion on the reactivity remained to be further investigated.

Our analysis reveals that, in all forms, Cu(II) binding to α-Syn reduces the toxic redox reactivity of free copper, thereby representing a potential line of protection in the case of Cu(II) altered homeostasis. On the other hand, α-Syn-Cu(II) still possesses detrimental catalytic redox properties. In this work, we reveal that membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes possess an exacerbated catechol oxidase activity compared to soluble forms, which can contribute to cellular toxicity in light of the relevance of membrane-binding to the physiological functions of α-Syn. The altered Cu(II) coordination environment in the membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II), where His50 is not involved in coordination, and the resulting shift to lower affinity sites appears central to the observed reactivity. Moreover, we show that these Cu(II) complexes can be efficiently targeted and silenced by the neuronal protein metallothionein-3. On one hand, the work provides additional evidence for the general gatekeeping role of Zn7MT-3 in controlling aberrant protein-copper interactions in the central nervous system. On the other, the gained knowledge provides an extension of the molecular rationale for therapeutic intervention in the treatment of PD aimed at increasing MT-3 levels in the brain.

Methods

Expression and purification of recombinant human α-Syn and preparation of the α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes.

NH2α-Syn was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells using a pET-3d plasmid (GenScript) encoding for the human α-Syn sequence. Transformed cells were grown overnight in LB media with 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37°C. The overnight pre-culture was used to inoculate fresh media (1000-fold dilution), and the cells were grown at 37°C until OD600=0.3. Protein expression was induced by adding 1 mM IPTG for 3.5 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation (6000 xg, 25 min, 4°C; Thermo Scientific LYNX 6000) and then resuspended in osmotic shock buffer to release periplasmic proteins following the method of Huang et al. [79]. The protein was purified through anion exchange chromatography using a HiPrep DEAE FF 16/10 column connected to an ӒKTA Pure chromatographic system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) using a linear gradient of 100 to 300 mM NaCl in 20 mM tris-HCl pH 8.0, followed by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 75 column eluted in 20 mM N-ethylmorpholine buffer, pH 7.4. The N-terminally acetylated α-synuclein (NAcα-Syn) was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells upon co-transformation of the NH2α-Syn plasmid and the pNatB plasmids (pACYCduet-naa20-naa25, Addgene plasmid # 53613) encoding for the NatB N-acetylase. Expression and purification was performed similarly to NH2α-Syn, except for the addition of 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol to the growth media. Correctness of expression and acetylation was confirmed by ESI-MS and the purity confirmed by SDS-PAGE. Protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically using ε280 =5,960 M−1cm−1 (Agilent Cary 300 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer). To prepare the soluble α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes, α-Syn was titrated with Cu(II) (protein: Cu ratio 1.2:1, mol/mol) using a 10 mM CuCl2 stock and incubated for 20 min.

To generate membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes, small unilamellar vesicles were prepared following the method of Dudzik (2013) [41]. Briefly, a mixture of 70% phosphatidylcholine (POPC) and 30% phosphatidylglycerol (POPG) (Avanti Polar Lipids) was dried overnight, resuspended in water, and sonicated with a tip sonicator (Fisher) at 40% power, 30 s/40 s sonication/resting time on ice, for a total of 5 min sonication time. The vesicle size was determined using a Malvern Zetasizer Nanoseries on 100 μg/ml lipid samples (25°C). α-Syn was inserted to lipid vesicles by incubating α-Syn and lipids in a molar ratio of 1:500 (α-Syn: lipids, mol/mol) with shaking at 25°C (12 h). Insertion into vesicles was confirmed by size exclusion chromatography in 20 mM N-ethylmorpholine buffer, pH 7.4 using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column. To prepare the membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes, membrane-inserted α-Syn was reacted with Cu(II) (protein: Cu ratio 1.2:1, mol/mol) using a 10 mM CuCl2 stock and incubating for 20 min.

To confirm Cu(II) binding to membrane-bound α-Syn, 500 μM membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) samples in 20 mM N-ethylmorpholine pH 7.4 buffer and 25% (v/v) glycerol were flash frozen using liquid nitrogen. The EPR spectra were subsequently obtained using a Bruker EMX EPR Spectrometer at approximately 10 K using υ=9.35 GHz, microwave power of 0.77 mW, modulation amplitude of 10.0 G, and sweep width of 1200 G. Cu(II) bound to α-Syn was quantified by using centrifugal membranes (3-kDa MWCO filters for the soluble forms and 50-kDa MWCO for the membrane-bound forms) to separate unbound Cu(II). The copper content in the filtrate and supernatant were quantified via ICP-MS analysis (Agilent 7900) in samples digested in 1% HNO3.

Expression and purification of Zn7MT-3

Recombinant human MT-3 was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLys using codon optimized pET-3d plasmid encoding for the human MT-3 sequence (Novagen). Following the method of Faller (1999) [80], the proteins were expressed and purified as Cd proteins by adding 0.4 mM CdSO4 30 minutes after expression induction with IPTG (1 mM). The apo MTs were then generated by addition of HCl following the method of Vasak (1991) [81] and reconstituted to the Zn7MT form by adding ZnCl2 and adjusting the pH to 8.0 using 1 M Tris base. The protein concentration was determined photometrically (Agilent Cary 300 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer) in 0.1 mM HCl using ε220 =53,000 M−1 cm−1 [49] Cysteine-to-protein ratios were determined by photometric quantification of sulfhydryl groups (CysSH) upon reaction with 2,2-dithiodipyridine in 0.2 M sodium acetate/1 mM EDTA (pH 4.0) using ε343=7,600 M−1 cm −1[82]. Metal-to-protein ratios were determined by ICP-MS (Agilent 7900) using samples digested in 1% HNO3. For the ZnMTs, CysSH-to-protein ratios of 20 ± 3 and zinc-to-protein ratios of 7.0 ± 0.4 were obtained.

Measurement of dopamine oxidase activity using 3-methyl-2-benzothiazolinone hydrazone (MBTH)

To determine dopamine oxidase activity, NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM) were incubated with 1 mM dopamine in the presence of 2 mM MBTH. The absorption spectra (450–650 nm) were recorded after 100 min (Agilent Cary 300 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer). The absorption spectrum of 1 mM dopamine (dopamine auto-oxidation) without α-Syn-Cu(II)) was recorded and subtracted to obtain the net rates. Concentration-dependent dopamine oxidase activity was determined by incubating α-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM) with increasing dopamine concentrations (0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.25, 0.35, 0.50, 1.00, 1.50, 2.00 mM, freshly prepared before addition) in the presence of 2 mM MBTH in 20 mM N-ethylmorpholine/100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl (25°C). The absorbance at 500 nm was determined after 120 s for soluble forms and 20 s for membrane-bound forms. Using ε500=3.25 × 104 M−1cm−1, the rates of dopamine oxidation were calculated as nmol quinone*μmol−1 α-Syn-Cu(II)*min−1 and plotted against the dopamine concentration to obtain Km and Vmax. The effect of H2O2 to the rate of dopamine oxidation was determined by addition of increasing H2O2 concentrations (0.01 – 1.00 M) to the reaction mixture immediately before addition of dopamine. Quenching by Zn7MT-3 was determined by incubating the α-Syn-Cu(II) complex with Zn7MT-3 (4:1 mol/mol) for 1 h at 25°C before initiating the reaction with dopamine.

Measurement of dopamine oxidase activity in the absence of MBTH

To determine dopamine oxidase activity, soluble or membrane-bound NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) or NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM) were incubated with 2 mM dopamine in the absence of 2 mM MBTH, and the kinetics of dopaminochrome formation followed by absorption spectroscopy at 475 nm (ε=3,700 M−1 cm−1) [42], [64], [65]. The absorbance at 475 nm was determined after 10 min for soluble forms and 2 min for membrane-bound forms and the rates of dopamine oxidation were calculated as nmol dopaminochrome*μmol−1 α-Syn-Cu(II)*min−1.

Determination of ROS generation by monitoring hydroxyl radical production and dityrosine formation

The formation of hydroxyl radical was determined using an SX20 Stopped-Flow spectrometer (Applied Photophysics). α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes (5 μM) were mixed with ascorbate (600 μM) and 3-CCA (400 μM), and the formation of the fluorescent product 7-OH-3-CCA was followed by monitoring fluorescence emission at 450 nm (λex=395 nm) for 450 s (37°C). To determine redox silencing by Zn7MT-3, the α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes were incubated with Zn7MT-3 (4:1 mol/mol) for 1 h at 25°C before addition of ascorbate.

Dityrosine formation was determined by incubating soluble NH2α-Syn-Cu(II) and NAcα-Syn-Cu(II) complexes (10 μM) with 1 mM ascorbate for 1 h at 37°C. The emission spectra (λex=325 nm) were subsequently recorded (375–550 nm) and compared to spectra of samples in absence of Cu(II). The kinetics of dityrosine formation was then followed by mixing 10 μM α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes with ascorbate (1 mM for soluble forms, 3 mM for membrane-bound form) and the fluorescence emission at 418 nm (λex=325 nm) monitored for 1 h (soluble forms) or 3 h (membrane-bound forms) at 37°C. To determine quenching by Zn7MT-3, the α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes were incubated with Zn7MT-3 (4:1 mol/mol) for 1 h at 25°C prior to ascorbate addition.

Low-temperature luminescence characterization of the products of α-Syn-Cu(II) and Zn7MT-3 interactions

Low-temperature luminescence spectra and lifetime decays were collected using a FluoroMax-4 spectrofluorometer (Horiba Scientific). α-Syn-Cu(II) (10 μM) complexes were reacted with Zn7MT-3 (0.25 eq.) for 1 h. The samples were then placed in quartz tubes with 2 mm inner diameter and immersed in a cylindrical quartz Dewar filled with liquid nitrogen. Emission spectra (380–750 nm, 5 nm slit) were obtained at 77 K with λex=320 nm (5 nm slit), using 10 μs initial delay and 300 μs sample window. Lifetime measurements were performed for the emissive bands at 425 nm and 575 nm using 50 μs initial delay and a 300 μs sample window. 10 μs and 20 μs delay increments and 500 μs and 1000 μs maximum delays were used for the 425 nm and 575 nm bands, respectively. Lifetime values were determined by fitting with a single exponential decay function.

Metal Exchange Determination by ICP-MS

The metal exchange between membrane-bound α-Syn and Zn7MT-3 were quantified by ICP-MS (Agilent 7900). Membrane-bound α-Syn-Cu(II) complexes (10 μM) were incubated with Zn7MT-3 (4:1 mol/mol) for 1 h at 25°C. 50-kDa MWCO centrifugal membranes were used to separate α-Syn from Zn7MT-3. The Cu(II) and Zn(II) content in the supernatant and filtrate were determined by ICP-MS (Agilent 7900) on samples digested in 1% HNO3.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Non-acetylated/N-acetylated α-synuclein-Cu(II) possess detrimental redox activities

Membrane-binding dramatically exacerbates α-synuclein-Cu(II) dopamine oxidase activity

Metallothionein-3 targets and silences the redox reactivity of α-synuclein-Cu(II)

MT-3 protection stems from Cu(II)/Cu(I) and thiolate/disulfide redox coupling

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (Grant: AT-1935-20170325 to G.M), by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R35GM128704 (to G.M.) and by funds of the University of Texas at Dallas. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Sheena D’Arcy and Dr. Kyle Murray (Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Texas at Dallas) for initial mass spectrometry analysis. We thank Jonathan Garcia Martinez, Sophia Kontos, and Luciano Perez-Medina for their supports with part of the experimental work.

Abbreviations

- PD

Parkinson’s Disease

- AD

Alzheimer’s Disease

- ND

neurodegenerative disease

- LB

Lewy bodies

- α-Syn

alpha-synuclein

- NH2α-Syn

non-acetylated alpha-synuclein

- NAcα-Syn

N-terminally acetylated alpha-synuclein

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- MT-3

metallothionein-3

- GIF

Growth Inhibitory Factor

- Aβ

amyloid-beta

- PrP

prion protein

- MW

molecular weight

- MWCO

molecular weight cut-off

- ICP-MS

Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry

- MBTH

3-methyl-2-benzothiazolinone hydrazone

- CNS

central nervous system

- 3-CCA

3-coumarin carboxylic acid

- SUVs

small unilamellar vesicles

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- THB

1,2,3-trihydroxylbenzene

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].de Lau LML and Breteler MMB, Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease, Lancet Neurol, 5, 6, 525–535, 2006, doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, and Goedert M, α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies, Nature, 388, 6645, 839–840, 1997, doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, and Goedert M, α-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, 95, 11, 6469–6473, 1998, doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stefanis L, α-Synuclein in Parkinson’s disease, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med, 2, 2, 1–23, 2012, doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Anderson JP et al. , Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of α-synuclein in familial and sporadic lewy body disease, J. Biol. Chem, 281, 40, 29739–29752, 2006, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bartels T, Choi JG, and Selkoe DJ, α-Synuclein occurs physiologically as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation, Nature, 477, 7362, 107–111, 2011, doi: 10.1038/nature10324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Moriarty GM, Janowska MK, Kang L, and Baum J, Exploring the accessible conformations of N-terminal acetylated α-synuclein, FEBS Lett, 587, 8, 1128–1138, 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].González N et al. , Effects of alpha-synuclein post-translational modifications on metal binding, J. Neurochem, 150, 5, 507–521, 2019, doi: 10.1111/jnc.14721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Öhrfelt A et al. , Identification of novel α-synuclein isoforms in human brain tissue by using an online NanoLC-ESI-FTICR-MS method, Neurochem. Res, 36, 11, 2029–2042, 2011, doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0527-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Logan T, Bendor J, Toupin C, Thorn K, and Edwards RH, α-Synuclein promotes dilation of the exocytotic fusion pore, Nat. Neurosci, 20, 5, 681–689, 2017, doi: 10.1038/nn.4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Burré J, Sharma M, Tsetsenis T, Buchman V, Etherton MR, and Südhof TC, α-Synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro, Science, 329, 5999, 1663–1667, 2010, doi: 10.1126/science.1195227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ulmer TS, Bax A, Cole NB, and Nussbaum RL, Structure and dynamics of micelle-bound human α-synuclein, J. Biol. Chem, 280, 10, 9595–9603, 2005, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Davidson WS, Jonas A, Clayton DF, and George JM, Stabilization of α-Synuclein secondary structure upon binding to synthetic membranes, J. Biol. Chem, 273, 16, 9443–9449, 1998, doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jao CC, Der-Sarkissian A, Chent J, and Langen R, Structure of membrane-bound α-synuclein studied by site-directed spin labelling, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 101, 22, 8331–8336, 2004, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400553101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dedic J, Rocha S, Okur HI, Wittung-Stafshede P, and Roke S, Membrane-Protein-Hydration Interaction of α-Synuclein with Anionic Vesicles Probed via Angle-Resolved Second-Harmonic Scattering, J. Phys. Chem. B, 123, 5, 1044–1049, 2019, doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b11096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Valensin D, Dell’Acqua S, Kozlowski H, and Casella L, Coordination and redox properties of copper interaction with α-synuclein, J. Inorg. Biochem, 163, 292–300, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Atrián-Blasco E, González P, Santoro A, Alies B, Faller P, and Hureau C, Cu and Zn coordination to amyloid peptides: From fascinating chemistry to debated pathological relevance, Coord. Chem. Rev, 371, submitted, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].George J et al. , Targeting the Progression of Parkinsons Disease, Curr. Neuropharmacol, 7, 1, 9–36, 2009, doi: 10.2174/157015909787602814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Acevedo K, Masaldan S, Opazo CM, and Bush AI, Redox active metals in neurodegenerative diseases, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem, 24, 8, 1141–1157, 2019, doi: 10.1007/s00775-019-01731-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McLeary F et al. , Switching on Endogenous Metal Binding Proteins in Parkinson’s Disease, Cells, 8, 2, 179, 2019, doi: 10.3390/cells8020179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Davies KM et al. , Copper pathology in vulnerable brain regions in Parkinson’s disease, Neurobiol. Aging, 35, 4, 858–866, 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Arnal N, Cristalli DO, de Alaniz MJT, and Marra CA, Clinical utility of copper, ceruloplasmin, and metallothionein plasma determinations in human neurodegenerative patients and their first-degree relatives, Brain Res, 1319, 118–130, 2010, doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Okita Y, Rcom-H’cheo-Gauthier AN, Goulding M, Chung RS, Faller P, and Pountney DL, Metallothionein, copper and alpha-synuclein in alpha-synucleinopathies, Front. Neurosci, 11, April, 1-9, 2017, doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Paik SR, Shin H-J, and Lee J-H, Metal-Catalyzed Oxidation of α-Synuclein in the Presence of Copper(II) and Hydrogen Peroxide, Arch. Biochem. Biophys, 378, 2, 269–277, 2000, doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Davies P et al. , The synucleins are a family of redox-active copper binding proteins, Biochemistry, 50, 1, 37–47, 2011, doi: 10.1021/bi101582p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Meloni G and Vasak M, Redox activity of alpha-synuclein-Cu is silenced by Zn(7)-metallothionein-3, Free Radic Biol Med, 50, 11, 1471–1479, 2011, doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wang C, Liu L, Zhang L, Peng Y, and Zhou F, Redox reactions of the α-Synuclein-Cu2+ complex and their effects on neuronal cell viability, Biochemistry, 49, 37, 8134–8142, 2010, doi: 10.1021/bi1010909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Binolfi A et al. , Bioinorganic chemistry of Parkinson’s disease: Structural determinants for the copper-mediated amyloid formation of alpha-synuclein, Inorg. Chem, 49, 22, 10668–10679, 2010, doi: 10.1021/ic1016752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Paik SR,Shin H-J,Lee J-H,Chang C-S, and Kim J, Copper(II)-induced self-oligomerization of α-synuclein, Biochem. J, 340, 3, 821, 1999, doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3400821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dudzik CG, Walter ED, and Millhauser GL, Coordination features and affinity of the Cu2+ site in the α-synuclein protein of Parkinson’s disease, Biochemistry, 50, 11, 1771–1777, 2011, doi: 10.1021/bi101912q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kowalik-Jankowska T, Rajewska A, Jankowska E, and Grzonka Z, Copper(ii) binding by fragments of α-synuclein containing M 1-D2- and -H50-residues; A combined potentiometric and spectroscopic study, Dalt. Trans, 42, 5068–5076, 2006, doi: 10.1039/b610619f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gentile I et al. , Interaction of Cu(i) with the Met-X3-Met motif of alpha-synuclein: binding ligands, affinity and structural features, Metallomics, 10, 10, 1383–1389, 2018, doi: 10.1039/c8mt00232k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Drew SC et al. , Cu2+ binding modes of recombinant alpha-synuclein--insights from EPR spectroscopy., J. Am. Chem. Soc, 130, 24, 7766–7773, 2008, doi: 10.1021/ja800708x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sung Y, Rospigliosi C, and Eliezer D, NMR mapping of copper binding sites in alpha-synuclein, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Proteins Proteomics, 1764, 1, 5–12, 2006, doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].De Ricco R et al. , Remote His50 Acts as a Coordination Switch in the High-Affinity N-Terminal Centered Copper(II) Site of α-Synuclein, Inorg. Chem, 54, 10, 4744–4751, 2015, doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Binolfi A et al. , Site-specific interactions of Cu(II) with $α$ and $β$-synuclein: Bridging the molecular gap between metal binding and aggregation, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 130, 35, 11801–11812, 2008, doi: 10.1021/ja803494v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Rodríguez EE et al. , Role of N-terminal methionine residues in the redox activity of copper bound to alpha-synuclein, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem, 21, 5–6, 691–702, 2016, doi: 10.1007/s00775-016-1376-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Moriarty GM, Minetti CASA, Remeta DP, and Baum J, A revised picture of the Cu(II)-α-synuclein complex: The role of N-terminal acetylation, Biochemistry, 53, 17, 2815–2817, 2014, doi: 10.1021/bi5003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Abeyawardhane DL, Heitger DR, Fernández RD, Forney AK, and Lucas HR, C-Terminal Cu II Coordination to α-Synuclein Enhances Aggregation, ACS Chem. Neurosci, 10, 3, 1402–1410, 2019, doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ramis R, Ortega-Castro J, Vilanova B, Adrover M, and Frau J, Copper(II) Binding Sites in N-Terminally Acetylated α-Synuclein: A Theoretical Rationalization, J. Phys. Chem. A, 121, 30, 5711–5719, 2017, doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.7b03165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dudzik CG, Walter ED, Abrams BS, Jurica MS, and Millhauser GL, Coordination of Copper to the Membrane-Bound Form of α-Synuclein, 2013, doi: 10.1021/bi301475q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Dell’Acqua S et al. , Copper(I) Forms a Redox-Stable 1:2 Complex with α-Synuclein N-Terminal Peptide in a Membrane-Like Environment, Inorg. Chem, 55, 12, 6100–6106, 2016, doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b00641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Vasák M and Hasler DW, Metallothioneins: new functional and structural insights., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol, 4, 2, 177–183, 2000, doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(00)00082-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Vasak M and Meloni G, Chemistry and biology of mammalian metallothioneins, J Biol Inorg Chem, 16, 7, 1067–1078, 2011, doi: 10.1007/s00775-011-0799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Uchida Y, Takio K, Titani K, Ihara Y, and Tomonaga M, The growth inhibitory factor that is deficient in the Alzheimer’s disease brain is a 68 amino acid metallothionein-like protein, Neuron, 7, 2, 337–347, 1991, doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Uchida Y and Tomonaga M, Neurotrophic action of Alzheimer’s disease brain extract is due to the loss of inhibitory factors for survival and neurite formation of cerebral cortical neurons, Brain Res, 481, 1, 190–193, 1989, doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Miyazaki I et al. , Expression of metallothionein-III mRNA and its regulation by levodopa in the basal ganglia of hemi-parkinsonian rats, Neurosci. Lett, 293, 1, 65–68, 2000, doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hozumi I, Asanuma M, Yamada M, and Uchida Y, Metallothioneins and Neurodegenerative Diseases, J. Heal. Sci, 50, 4, 323–331, 2004, doi: 10.1248/jhs.50.323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Meloni G, Faller P, and Vašák M, Redox silencing of copper in metal-linked neurodegenerative disorders: Reaction of Zn7metallothionein-3 with Cu2+ ions, J. Biol. Chem, 282, 22, 16068–16078, 2007, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Calvo JS, Lopez VM, and Meloni G, Non-coordinative metal selectivity bias in human metallothioneins metal-thiolate clusters, Metallomics, 10, 12, 1777–1791, 2018, doi: 10.1039/c8mt00264a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Meloni G et al. , Metal swap between Zn7-metallothionein-3 and amyloid-beta-Cu protects against amyloid-beta toxicity, Nat Chem Biol, 4, 6, 366–372, 2008, doi: 10.1038/nchembio.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Meloni G et al. , The Catalytic Redox Activity of Prion Protein-Cu II is Controlled by Metal Exchange with the Zn II-Thiolate Clusters of Zn 7Metallothionein-3, ChemBioChem, 13, 9, 1261–1265, 2012, doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Atrian-Blasco E, Santoro A, Pountney DL, Meloni G, Hureau C, and Faller P, Chemistry of mammalian metallothioneins and their interaction with amyloidogenic peptides and proteins, Chem. Soc. Rev, 46, 24, 7683–7693, 2017, doi: 10.1039/c7cs00448f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Pedersen JT et al. , Rapid exchange of metal between Zn(7)-metallothionein-3 and amyloid-beta peptide promotes amyloid-related structural changes, Biochemistry, 51, 8, 1697–1706, 2012, doi: 10.1021/bi201774z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]