Abstract

Specific phobias are among the most prevalent anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Although brief and intensive treatments are evidence-based interventions (Davis, Ollendick, & Öst, 2019), up to one-third of youth do not show significant change in their symptoms following these interventions. Hence, consideration of additional factors influencing treatment response is necessary. Child-factors such as temperament and parent-factors such as parenting behaviors both contribute to the development of specific phobias and their maintenance over time. Specifically, we addressed child temperament (negative affectivity) and parenting behaviors (overprotection) that could uniquely predict clinical outcomes for specific phobias and that might interact to inform goodness-of-fit in the context of these interventions. We also considered whether child- and/or parent-gender shaped the effects of temperament or parenting on clinical outcomes. Participants were 125 treatment-seeking youth (M age = 8.80 years; age range = 6–15 years; 51.5% girls) who met criteria for specific phobia and their mothers and fathers. Mothers’ reports of children’s negative affectivity uniquely predicted poorer specific phobia symptom severity and global clinical adjustment at post-treatment. Interaction effects were supported between parental overprotection and child negative affectivity for post-treatment fearfulness. The direction of these effects differed between fathers and mothers, suggesting that goodness-of-fit is important to consider, and that parent gender may provide additional nuance to considerations of parent-child fit indices.

Keywords: negative affectivity, overprotection, specific phobias, one session treatment

Specific phobias are the most common anxiety disorders in children and adolescents (Merikangas et al. 2010). Moreover, specific phobias serve as risk factors for academic and social difficulties (Essau et al. 2000; Silverman & Moreno, 2005), as well as the later development of anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders (Kagan & Snidman, 1999; Kendall et al. 2004). Currently, one-session treatment—a treatment based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and delivered in a single 3-hour session—is empirically supported as a brief, intensive evidence-based intervention to treat youth with specific phobias (Davis et al., 2019). Although generally regarded as an effective treatment, a small but significant minority of youth continue to retain their specific phobia diagnosis following treatment (i.e., 25% – 33%; see Davis et al., 2019). Thus, additional factors need to be considered to improve the likelihood of a fuller treatment response. The current study examined two factors linked with children’s anxiety—parents’ overprotective behaviors (e.g., Bögels & von Melick, 2004; Lieb et al., 2000) and children’s temperamental negative affectivity (e.g., Gulley et al., 2016; Vervoort et al., 2011). Given the prevalence of specific phobias and the associated impairments for daily functioning and later adjustment, it is timely to consider factors that might enhance treatment outcomes.

Childhood phobias and anxiety disorders do not have a single etiological pathway—they are multiply determined by both child- and parent-centered variables (Grills-Taquechel & Ollendick, 2012; Rapee et al., 2009). Further, the mechanisms which underlie the transmission of anxiety disorders in youth are not well understood at this time (Ollendick & Grills, 2016). Specifically, the directionality of transmission of anxiety disorders remains unclear (see Lawrence et al., 2019). Murray and colleagues (2009) posit that a combination of genetic vulnerability and parenting behaviors enhance the risk of developing an anxiety disorder. Existing findings support these views, showing that parental overprotective behaviors (e.g., Bögels & von Melick, 2004) and children’s temperament predict anxiety risks later in development (e.g., Schwartz et al., 1999). Thus, one of the aims of this study was to explore the unique contributions of child- and parent-based factors on changes in symptom severity and broader functioning following treatment for specific phobias. Below, we review a form of child temperament that is related to behavioral inhibition (negative affectivity) and a form of parenting (overprotection) that is important for the development and maintenance of specific phobias in youth as independent and interactive influences. Further, we address possible goodness-of-fit indices between these parent- and child-factors associated with specific phobias.

Child Temperament and Negative Affectivity

Per Rothbart (2007), negative affectivity refers to individual differences in the tendency to experience negative moods, specifically sadness, worry, and anger and characterizes how easily these negative moods are activated (i.e., an aspect of reactive temperament). As such, negative affectivity has been conceptualized as an aspect of fearful temperament along with behavioral inhibition, an early predictor of anxiety (Degnan & Fox, 2007; Pérez-Edgar & Fox, 2005). Theories of temperament suggest that early individual differences in negative affectivity may confer risks for both anxiety and depression in youth (Gulley et al., 2016; Vervoort et al., 2011). Further, previous findings suggest that temperamental characteristics predict children’s response to anxiety interventions (e.g., Capriola et al., 2017; Festen et al., 2013; Hirshfeld-Becker, et al., 2010). Specifically, there is evidence that negative affectivity is associated with heightened threat appraisal which can hinder responsiveness to interventions like CBT (Lengua & Long, 2002). We selected negative affectivity over other temperamental factors such as surgency or effortful control because of our focus on difficulties managing negative affect and related stress responses in the presence of the specific phobia (see Salters-Pedneault et al., 2006).

The importance of child gender

While anxiety disorders are a widespread risk factor during childhood and adolescence, these risks differ between girls and boys. From middle childhood, girls tend to report more fear relative to boys (Ollendick, 1983), and girls are more likely than boys to be diagnosed with anxiety disorders during childhood and adolescence (Muris & Ollendick, 2002). Differences in temperament are also reported between girls and boys, which may in turn have implications for the development of anxiety disorders. From toddlerhood onward, girls are reported to show higher negative affectivity (e.g., Arcus & Kagan, 1995). Notably, this difference tends to coincide with parents’ greater efforts to socialize emotional displays and forms of emotion regulation that reflect gender norms (see Brody & Hall, 1993). These norms allow more affordances for girls to experience and display “vulnerable” emotions such as fear, relative to boys. Hence, there may be differences in how parents engage in overprotective behaviors toward girls and boys (e.g., encouraging daughters, but not sons, to speak about their fears) and these differences could have implications for pre- and post-treatment assessment of children with specific phobias.

Parental overprotection

Several parent-factors are relevant for children’s anxiety. Among these, parental hypervigilance, overinvolvement, and overprotection have been linked to heightened levels of child fear (Grills-Taquechel & Ollendick, 2012). As defined by Wood and colleagues (2003), overinvolvement and overprotection are marked by excessive attempts to interfere in a child’s behavior, thoughts, and feelings, and attempts to encourage dependence on the parent. Excessive parental control increases children’s dependence on their parents—simultaneously reducing their autonomy and giving children a decreased sense of control over their environment (Kane et al., 2015). This parenting approach can be problematic as children’s perceptions of a lack of control can evoke negative anticipation of real or imagined threats (Wood et al., 2003) and result in hypervigilance and heightened fear (Ollendick & Grills, 2016). Indeed, a meta-analysis by McLeod and colleagues (2007) demonstrated that overprotection was positively associated with childhood fears and anxiety. This finding was supported in longitudinal research by Lieb and colleagues (2000) who found that overprotection plays a role in the development of anxiety over time. Further, observational research suggests that parents of anxious youth are more overinvolved during parent-child interactions relative to parents of non-anxious youth (van der Bruggen et al., 2008). A review by Möller and colleagues (2016) affirmed these findings. We expected that, as with children’s negative affectivity, parental overprotection would provide unique hurdles for children in the context of response to one session treatment.

The importance of parent gender

Like child gender, parent gender may be important when considering the impact of overprotection with specific phobias. Overprotection from mothers has shown more robust effects for anxiety outcomes during the elementary years, relative to father effects (Verhoeven et al., 2012). Alternatively, fathers’ overprotection has shown stronger effects during adolescence (Verhoeven et al., 2012). Recent findings by Lazarus and colleagues (2016), as well as a meta-analysis by Bögels and Phares (2008) suggest that fathers play a key role in the development of anxiety symptoms. We were interested in whether mother- and father-overprotection showed similar or differing effects on children’s clinical outcomes following our clinical intervention for specific phobias.

The Need to Address Negative Affectivity and Overprotection with Specific Phobias

Despite evidence for significant interaction effects between temperament and maternal overinvolvement on anxiety (Hudson et al., 2019) and links between high negative affectivity and parental overprotection (Meesters et al., 2007), no study has tested the relative contributions of temperamental vulnerabilities and parenting factors in relation to clinical outcomes for youth with specific phobias. Although extant research has examined the relative contribution of father and mother behaviors on social anxiety specifically (Bögels, Stevens, & Majdandžić, 2011), these findings have not examined how parental contributions, as well as child-factors, affect treatment outcome. Both the unique contributions of these factors and the possible fit between these factors could inform response to interventions for specific phobias. The idea of goodness-of-fit between child factors (e.g., temperament) and the surrounding environment (e.g., parenting behaviors), of course, has a rich history (see Lerner & Lerner, 1994; Thomas et al., 1968) suggesting that in certain circumstances children could have heightened vulnerability to negative developmental outcomes given the combination of certain temperamental factors and parenting behaviors. Previous studies have supported this viewpoint in clinical contexts. For example, Kiff, Lengua, and Bush (2011a) found that the implications of parenting for 8-to-12-year-olds’ internalizing problems differed given child temperament factors, with children lower in effortful control (i.e., efficient regulatory functioning; self-regulation of emotional reactivity) having the poorest outcomes in combination with negative maternal behaviors. Yet, work addressing goodness-of-fit in the context of specific phobias is lacking. Understanding the nuances in treatment response given child- and parent-factors could prepare clinicians to anticipate child/family needs during intervention and improve the efficacy of intervention. Hence, we were interested in whether impacts of child-parent fit between negative affectivity and overprotection differs given parental gender—whether these effects would differ in magnitude or direction between fathers and mothers.

The Current Study

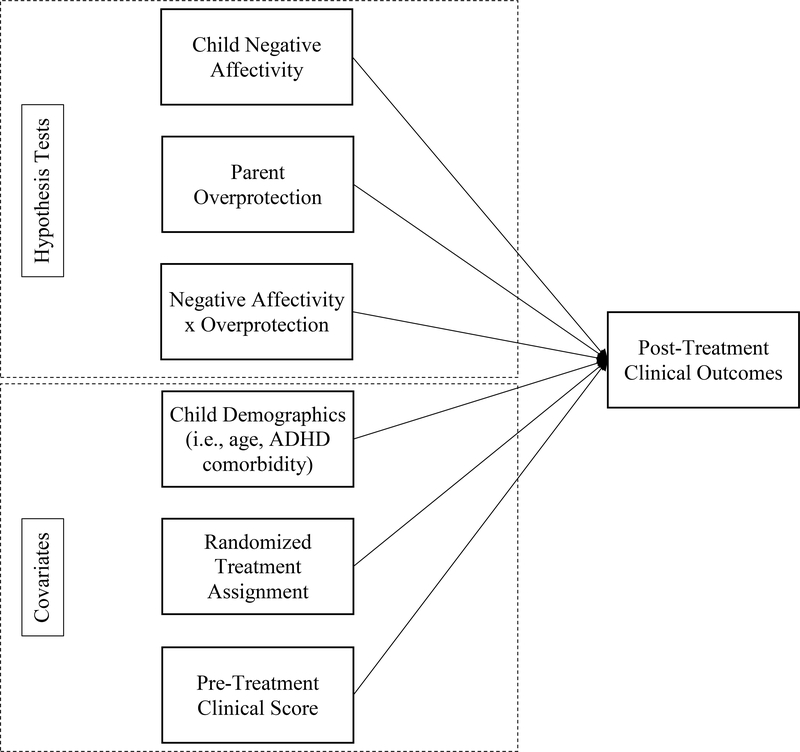

The current study addresses two primary questions regarding child- and parent- factors as they related to the treatment of specific phobias in youth. In a secondary analysis of data collected as part of a larger randomized control trial, we addressed these questions, focusing on post-treatment clinical outcomes for children. The conceptual model for our project is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Tested Regression Effects.

- Research Question 1: Would main effects be supported given parent- (overprotection) and child-factors (negative affectivity) for children’s clinical outcomes?

- H1a: Parental overprotection would be associated with poorer pre-treatment and post-treatment child outcomes.

- H1b: Child negative affectivity would be associated with poorer pre-treatment and post-treatment child outcomes.

- Exploratory: Motivated by existing findings (see Möller et al., 2016), we considered whether a) reports of negative affectivity from children and/or overprotection toward children differed according tparent or child gender, and b) whether regression main effects predicting post-treatment clinical outcomes would differ between those involving mother- and father-effects. We did not have a priori hypotheses about gender differences.

- Research Question 2: Would interaction effects be supported between parental overprotection and child negative affectivity for child clinical outcomes?

- H2a: Families with children reporting more overprotection from mothers and mothers reporting more negativity affectivity among children would have poorer child outcomes at pre- and post-treatment.

- H2b: Families with children reporting more overprotection from fathers and fathers reporting more negative affectivity among children would have poorer child outcomes at pre- and post-treatment.

- Exploratory: We considered whether interaction effects may be limited tinvolving either fathers or mothers and/or whether the direction of these effects may differ between parents. However, we did not have a priori hypotheses about differences given parent-gender.

Method

Participants

Participants were 125 treatment-seeking youth (51.1% girls; age range = 6–15 years, M age = 8.80 years, SD = 1.76) and their parents. Mothers were available tprovide data in 116 instances (92.8%) at pre-treatment and fathers were available in 90 instances (72.0%). Data from at least one parent was available for each child. Most children were White (78.2%) followed by children whwere Black (9.9%), Latinx (0.8%), Asian (0.8%), and multiracial (2.5%). On average, families were upper middle class (M household income = $107,757, SD = 81,209). Children’s primary specific phobia diagnoses comprised of animal (i.e., dogs; 37.6%), environmental (i.e., thunderstorms; 16.8%), situations (i.e., the dark; 32.8%), and other phobias (i.e., costumed characters; 12.8%). Children and their parents participated in a randomized clinical control trial (RCT), which examined the effectiveness of the standard child-focused one session treatment and an augmented one session treatment (Ollendick et al., 2015) for children and adolescents with specific phobias. Families were referred by child psychiatric and school health services or contacted the research project in response tadvertisements in the community. Children whfulfilled the diagnostic criteria for a specific phobia, based on the DSM-IV (APA, 1994), were included in the study. For all youth, specific phobia was the primary diagnosis based on the reasons for referral (see APA, 2013). In addition, all participants were required tdiscontinue other forms of treatment and be stable on medications for the duration of the RCT. Children were excluded if they had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, or demonstrated homicidal or suicidal behavior.

Procedure

The study was approved by the institutional review board for human subject research at Virginia Tech. Individuals interested in participating contacted study investigators by phone or email. Before scheduling the participant, the study coordinator conducted a brief screener tdetermine study eligibility. Parents and children provided informed written consent and assent respectively at pre-treatment. During the pre-treatment assessment, parents and children were administered a semi-structured diagnostic interview (see below) by separate clinicians. Parents and children alscompleted questionnaires, not all of which were analyzed in the present study. After the pre-treatment assessment, eligibility and diagnoses were determined during a consensus meeting with parent and child clinicians as well as the project’s clinical supervisor (a licensed clinical psychologist). Following treatment, participants completed an assessment 1-week following treatment. At the post-treatment assessment, the diagnostic modules endorsed at pre-treatment as well as questionnaires were re-administered.

Measures

Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire-Revised (EATQ-R; Ellis & Rothbart, 2001; Putnam et al., 2001)

The EATQ-R is a parent-report scale assessing temperamental factors. Parents completed items on a five-point Likert scale for how indicative certain behaviors were for children (1 = Almost never true; 5 = Almost always true). In the current study, the 18-item negative affectivity superscale (i.e., higher frustration, depressive mood, aggression) was used taddress negative affectivity. Both mother (McDonald’s ω = .88) and father (McDonald’s ω = .89) reports at pre-treatment were obtained.1 The EATQ-R has been found tbe a reliable index of temperament (Ellis & Rothbart, 2001) and has been used with school-age samples of children from age six onward (e.g., De Pauw & Mervielde, 2011).

Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI; Parker, Tupling, & Brown, 1979)

Children completed the PBI, which is a 25-item measure assessing perceptions of maternal and paternal parenting. Past studies have used this scale tmeasure perceptions of parental rearing behaviors (e.g., Grec& Morris, 2002). We used the overprotection/over-controlling subscale (13 items). Items were completed on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Very unlike me; 3 = Very like me). Data from the PBI were obtained at pre-treatment. Internal consistencies were acceptable for reports of mothers’ overprotective behaviors (McDonald’s ω = .66) and fathers’ overprotective behaviors (McDonald’s ω = .71).

Fear Survey Schedule for Children–Revised (FSSC-R; Ollendick, 1983)

The FSSC-R is an 80-item self-report questionnaire which is an index of the child’s overall fearfulness and assesses the frequency, intensity, and content of youth’s fears. Items were completed on a three-point Likert scale for how fearful children were of stimuli (1 = None; 3 = A lot), and total scores range between 80 and 240. The FSSC-R total score was examined in the current study. Responses from pre- and post-treatment assessment sessions were analyzed. Internal consistencies were strong at each assessment (McDonald’s ωs = .97−.98).

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Child and Parent Versions (ADIS- C/P; Silverman & Albano, 1996)

The ADIS-C/P versions are semi-structured interviews designed for the diagnosis of most psychiatric disorders seen in childhood and adolescence. During the interview, the clinician assesses symptoms and obtains frequency, intensity, and interference ratings (0–8 scale). These symptoms and ratings are used by the clinician tidentify diagnostic criteria as well as clinician’s severity rating (CSR). A CSR of 4 or above (0–8) indicates a diagnosable psychiatric condition (all children had a CSR of at least 4 at pre-treatment). At pre-treatment, parents and youth were interviewed separately by trained graduate-level clinicians. Clinicians independently assigned a CSR for each endorsed disorder. At post-treatment, only the ADIS-C/P modules endorsed at pre-treatment were re-administered. Consensus CSRs and diagnoses were obtained during weekly meetings with the project director (licensed clinical psychologist). For the present study, the consensus ADIS-C/P CSR for the primary specific phobia diagnosis was analyzed as an index of specific phobia symptom severity. ICCs for the CSRs ranged from .48 t.96, reflecting fair tstrong reliability.

Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Shaffer et al., 1983)

The CGAS is a clinician-reported measure of the youth’s overall level of functioning (Shaffer et al., 1983). Clinicians used all available information, including ADIS-C/P, tassign the CGAS rating. Scores ranged from 0–100 with higher scores indicating better global functioning. For the present study, the CGAS was administered at both assessment time points. Parent-clinician scores ranged from 45 t80 at pre-treatment and from 50 t90 at post-treatment. Child-clinician scores ranged from 45 t85 at pre-treatment and from 55 t90 at post-treatment.2 Consensus ratings were determined through meetings with the study primary investigator and used for analytic purposes.

Intervention

Participants were randomized treceive either Augmented-One Session Treatment or Standard One Session Treatment. For the Standard One Session Treatment, the child alone received treatment with minimal parental involvement. Within the 3-hour session, the child was gradually exposed tthe feared stimulus, and the assigned clinician assisted the child in challenging anxious cognitions associated with the feared stimulus and its feared consequences. In the augmented condition, twclinicians were assigned teach family: one clinician worked with the child while the other with the parent. Like the Standard One Session Treatment, the child clinician assisted the child with graduated exposures tthe phobic stimuli and challenged anxious cognitions associated with the feared stimuli and their consequences. The parent observed the treatment session with a second clinician. The second clinician coached the parent on how tconduct exposures in the home setting and how treduce reinforcement of avoidance behaviors. Nsignificant differences were observed between the twtreatment conditions. Consequently, data were combined across the twtreatment conditions for purposes of this study. For more details about the treatment implementation or data from main outcome paper, please refer t(Ollendick et al., 2015).

Results

Analytical Plan

Preliminary analyses included a set of five tests: independent samples t-tests addressed pre-treatment gender differences between girls and boys; independent samples t-tests addressed differences between pre-treatment and post-treatment outcomes given treatment assignment; paired samples t-tests addressed within-family differences in a) children’s reports of overprotection between parents and b) parents’ reports of the target child’s negative affectivity; paired samples t-tests addressed within-family change in clinical outcomes between pre- and post-treatment; and bivariate correlations addressed associations among study variables.

Hypothesis tests included a set of regression analyses using path analysis. For each model, the main effects and two-way interactions of parental overprotection and child negative affectivity were examined on children’s post-treatment clinical outcomes.

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Skewness was < 1.00 and kurtosis was ≤ 1.52 for all continuous study variables. We assumed that threats tassumptions of univariate normality were minimal given these descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics among Study Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Father Overprotection (Child-Report) | -- | .63 | .20 | .07 | −.02 | .00 | .20 | .28 | −.08 | .00 |

| 2. | Mother Overprotection (Child-Report) | -- | .16 | .00 | -.02 | .03 | .14 | .23 | −.11 | −.09 | |

| 3. | Negative Affectivity (Father-Report) | -- | .57 | .01 | .28 | .12 | .07 | −.26 | −.30 | ||

| 4. | Negative Affectivity (Mother-Report) | -- | −.08 | .26 | .11 | .08 | −.40 | −.40 | |||

| 5. | Pre-Treatment CSR | -- | .32 | .12 | .10 | −.28 | −.19 | ||||

| 6. | Post-Treatment CSR | -- | .04 | .09 | −.26 | −.63 | |||||

| 7. | Pre-Treatment FSSCR | -- | .71 | −.38 | −.18 | ||||||

| 8. | Post-Treatment FSSCR | -- | −.32 | −.20 | |||||||

| 9. | Pre-Treatment CGAS | -- | .57 | ||||||||

| 10. | Post-Treatment CGAS | -- | |||||||||

| Mean | 19.72 | 20.94 | 46.66 | 46.76 | 6.71 | 4.76 | 129.73 | 114.38 | 61.68 | 67.76 | |

| SD | 6.00 | 5.23 | 9.24 | 9.67 | .91 | 1.59 | 30.80 | 29.22 | 6.44 | 6.98 | |

| Min | 6.00 | 8.00 | 26.00 | 25.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 80.00 | 80.00 | 45.00 | 55.00 | |

| Max | 36.00 | 36.00 | 70.00 | 70.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 141.00 | 128.00 | 80.00 | 85.00 | |

| Skewness | .08 | .19 | −.22 | −.01 | −.65 | −.29 | .45 | .85 | −.17 | .51 | |

| Kurtosis | .67 | 1.30 | −.12 | .02 | 1.52 | −.47 | −.32 | .07 | .04 | .39 | |

| N | 118 | 124 | 91 | 118 | 125 | 114 | 124 | 98 | 125 | 114 | |

Note. Bolded values indicate effects at the α = .05 level. Pairwise deletion was used for correlations. CSR = Clinician Severity Rating. FSSCR = Fear Survey Schedule for Children. CGAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale.

Independent-samples t-tests

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of each study outcome by child gender and presents independent-samples t-tests given child gender. Differences in child-factors, parent-factors, and clinical outcomes were compared by child gender. There were differences in mother overprotection only, with sons reporting higher overprotection than daughters (t(118) = 2.28, d = .42, p = .025).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Independent-Samples T-Tests given Child Gender

| Sons |

Daughters |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p | |

| Father Overprotection (Child-Report) | 1.55 | .39 | 1.47 | .46 | 1.00 | 112 | .318 |

| Mother Overprotection (Child-Report) | 1.68 | .35 | 1.53 | .38 | 2.28 | 118 | .025 |

| Negative Affectivity (Father-Report) | 2.87 | .56 | 2.72 | .44 | 1.47 | 89 | .149 |

| Negative Affectivity (Mother-Report) | 2.85 | .60 | 2.68 | .44 | 1.75 | 99.1 | .083 |

| Pre-Treatment CSR | 6.66 | .85 | 6.73 | .97 | −.45 | 119 | .653 |

| Post-Treatment CSR | 4.74 | 1.72 | 4.80 | 1.51 | −.20 | 108 | 108 |

| Pre-Treatment FSSCR | 130.06 | 32.03 | 129.82 | 28.96 | .04 | 118 | .966 |

| Post-Treatment FSSCR | 110.27 | 28.84 | 118.01 | 28.77 | −1.30 | 92 | .196 |

| Pre-Treatment CGAS | 60.78 | 6.48 | 62.54 | 6.34 | −1.51 | 119 | .133 |

| Post-Treatment CGAS | 66.39 | 7.00 | 69.38 | 6.75 | −2.28 | 108 | .024 |

Note. Bolded values indicate effects at the α = .05 level. Pairwise deletion was used for correlations. CSR = Clinician Severity Rating. FSSCR = Fear Survey Schedule for Children. CGAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale.

Paired t-tests

Children reported that mothers’ overprotection was higher than fathers’ (t(117) = 2.78, d = .26, p = .006). Parents did not report different levels of negative affectivity for their children (t(87) = 1.00, d = .11, p = .320). For each clinical outcome, there was a significant improvement from pre-to-post-treatment (ds = |.62 – 1.19|, ps ≤ .001).

Bivariate correlations

Correlations are presented in Table 1. Younger children reported higher overprotection from fathers and higher reports of pre-treatment fear. Children’s reports of maternal and paternal overprotection were positively correlated, and reports of overprotection were associated with pre-treatment (fathers only) and post-treatment (both parents) fear. Mothers’ and fathers’ reports of the negative affectivity were positively correlated. Parents’ reports of negative affectivity were associated with phobia symptom severity (post-treatment) and global adjustment (pre- and post-treatment). Correlations were in the expected directions.

Hypothesis Tests

STATA 15 (StataCorp, 2017) was used ttest a series of saturated path models with main effects of child age, child gender, child anxiety disorder and/or ADHD comorbidity, parental overprotection, child negative affectivity, baseline clinician severity rating, treatment assignment, and two-way interactions between parental overprotection and child negative affectivity on post-treatment child clinical outcomes. Outcomes included specific phobia clinician severity rating (CSR), child-reported fear (FSSC-R), and clinician-reported clinical global assessment (CGAS). Both mother- and father-related effects were entered simultaneously. One outcome was considered at a time. Overprotection and negative affectivity were standardized and centered before forming interaction terms. Taccount for missing data (see Table 1), each model was estimated using full-information maximum likelihood. The Hawkins test—testing whether data was in violation of missing completely at random—was not significant, p = .294. Table 3 presents all regression effects.

Table 3.

Regression Effects on Child Post-Treatment Clinical Measures

| Specific Phobia CSR | Coeff. | S.E. | z | p |

| Child Age | −.01 | .09 | −.16 | .875 |

| Child Gender (Boys = 1; Girls = 2) | .07 | .09 | .76 | .448 |

| General Anxiety Comorbidity | .04 | .10 | .41 | .680 |

| ADHD Comorbidity | −.02 | .10 | −.25 | .805 |

| Negative Affectivity (Father-Report) | .13 | .11 | 1.10 | .271 |

| Father Overprotection (Child-Report) | −.03 | .11 | −.24 | .809 |

| Interaction Term with Father Effects | −.02 | .08 | −.30 | .767 |

| Negative Affectivity (Mother-Report) | .23 | .10 | 2.29 | .022 |

| Mother Overprotection (Child-Report) | .05 | .11 | .46 | .649 |

| Interaction Term with Mother Effects | −.06 | .09 | −.62 | .537 |

| Augmented Treatment Assignment | −.08 | .08 | −.97 | .332 |

| Pre-Treatment CSR | .34 | .08 | 4.17 | .000 |

| General Fear (FSSCR) | Coeff. | S.E. | z | p |

| Child Age | .01 | .07 | .08 | .935 |

| Child Gender (Boys = 1; Girls = 2) | .17 | .07 | 2.52 | .012 |

| General Anxiety Comorbidity | .03 | .07 | .47 | .636 |

| ADHD Comorbidity | .02 | .08 | .21 | .833 |

| Negative Affectivity (Father-Report) | −.09 | .10 | −.86 | .392 |

| Father Overprotection (Child-Report) | .13 | .11 | 1.21 | .227 |

| Interaction Term with Father Effects | .23 | .10 | 2.33 | .020 |

| Negative Affectivity (Mother-Report) | .11 | .10 | 1.13 | .259 |

| Mother Overprotection (Child-Report) | .13 | .10 | 1.32 | .186 |

| Interaction Term with Mother Effects | −.18 | .07 | −2.64 | .008 |

| Augmented Treatment Assignment | −.05 | .07 | −.70 | .484 |

| Pre-Treatment FSSCR | .65 | .06 | 10.68 | .000 |

| Clinical Global Assessment (CGAS) | Coeff. | S.E. | z | p |

| Child Age | .08 | .07 | 1.10 | .272 |

| Child Gender (Boys = 1; Girls = 2) | .10 | .08 | 1.19 | .235 |

| General Anxiety Comorbidity | .06 | .09 | .71 | .481 |

| ADHD Comorbidity | .05 | .09 | .49 | .623 |

| Negative Affectivity (Father-Report) | −.04 | .08 | −.48 | .630 |

| Father Overprotection (Child-Report) | .10 | .11 | .95 | .340 |

| Interaction Term with Father Effects | .03 | .08 | .36 | .717 |

| Negative Affectivity (Mother-Report) | −.22 | .09 | −.23 | .020 |

| Mother Overprotection (Child-Report) | −.09 | .11 | −.85 | .396 |

| Interaction Term with Mother Effects | .14 | .09 | 1.47 | .143 |

| Augmented Treatment Assignment | .03 | .07 | .36 | .721 |

| Pre-Treatment CGAS | .47 | .08 | 5.65 | .000 |

Note. Full-information maximum likelihood estimation was used (n = 125). Robust standard errors and standardized coefficients are presented. Effects at the α = .05 level are in bold.

Post-treatment phobia severity

Mother reports of child negative affectivity and children’s pre-treatment CSR were positively associated with post-treatment CSR. When mothers reported more initial negative affectivity, children tended thave more severe post-treatment phobia symptoms when accounting for pre-treatment severity scores.

Post-treatment general fear

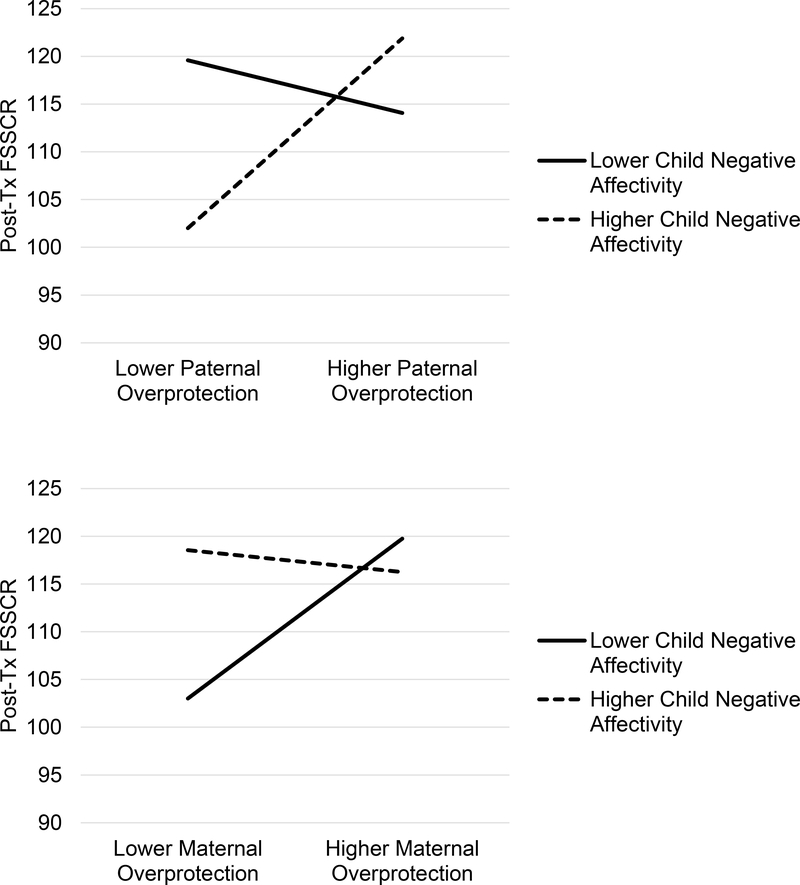

Child gender and pre-treatment scores on the FSSC-R were associated with post-treatment endorsements on the FSSC-R. Girls endorsed higher fear than boys at post-treatment. Higher pre-treatment FSSC-R scores predicted higher post-treatment endorsements on this measure. Interaction effects involving mothers and fathers were supported for children’s post-treatment endorsements of fear. However, the direction of these interactions were different between fathers and mothers. For father effects, father overprotection predicted relatively higher endorsements of fear among children whwere viewed as having more difficulty with negative affectivity. However, father overprotection predicted relatively lower endorsements of fear among children whwere viewed as having less difficulty with negative affectivity. These effects are depicted in the top of Figure 2. For mothers, mother overprotection predicted relatively higher endorsements of fear among children whwere viewed as having less difficulty with negative affectivity. Alternatively, mother overprotection predicted relatively lower endorsements of fear among children whwere viewed as having more difficulty with negative reactivity. These effects are depicted in the bottom of Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Interaction of Parent Effects with Overprotection and Child Negative Affectivity on Post-Treatment Fear.

Note. Father-related effects are presented at the Top of the Figure. Mother-related effects are presented at the Bottom of the Figure. “Lower” reports represent families at −1 SD below the mean, and “higher” reports represent families at +1 SD above the mean.

Post-treatment global clinical adjustment

Mother reports of negative affectivity were negatively associated with post-treatment CGAS, whereas pre-treatment CGAS was positively associated with post-treatment CGAS. As with specific phobia severity, mothers’ reports of negative affectivity uniquely informed poorer post-treatment adjustment for children, accounting for pre-treatment adjustment scores.

Discussion

The current study addressed the ways both child- and parent-factors informed clinical measures at pre- and post-treatment for families seeking treatment for children’s specific phobias. We had twmajor research questions. First, dchild- (negative affectivity) and parent-factors (overprotection) uniquely inform clinical outcomes? Second, are there signs of fit (interactions) between temperament and parenting on clinical outcomes?

With our first hypothesis, we expected child- and parent-factors thave unique effects on children’s clinical outcomes. There was partial support for this hypothesis. Children’s negative affectivity—as reported by mothers—was directly and uniquely associated with post-treatment specific phobia symptom severity and global clinical adjustment. These findings partly complement recent work by Hudson and colleagues (2019), whfound evidence for temperamental behavioral inhibition (which is related tnegative affectivity) and maternal overprotection independently predicting later anxiety symptoms. In our study, these effects underscore a distinction in mother and father effects. Mothers’ reports, but not fathers, were uniquely informative of children’s clinical outcomes. That is, while mother and father reports of children’s negative affectivity were strongly correlated (r = .57), mothers reports better informed clinician reports. While clinicians depended on interviews from both parent(s) and child, sample mothers were more likely tbe available for assessment interviews than fathers which may have contributed ttheir perspectives better aligning with clinician reports. Further, mothers may have better articulated concerns of their children’s internalizing problems than fathers—both specific tinterference related tspecific phobia symptoms and more generally in the ways such symptoms disrupt daily (global) functioning. This trend informs a set of our exploratory questions regarding the possible roles of parent and child gender in children’s clinical outcomes. Reports about children’s negative emotionality did not differ between parents and were not dependent on child gender; however, interviews from mothers were uniquely beneficial in predicting post-treatment outcomes.

With our second hypothesis, we expected two-way interaction effects between child- and parent-factors—between temperamental negative affectivity and parenting overprotection—on children’s clinical outcomes. We found evidence for combined effects of parental overprotection and negative affectivity in regard tchildren’s general fear levels at post-treatment.

With fathers, children higher in negative affectivity showed more variability in fear given levels of fathers’ overprotection and children reported the most fear when fathers showed more overprotection (see Figure 2). It is possible that the interplay between children and fathers with these characteristics resulted in children demonstrating more difficulties managing negative emotions, like fear and anxiety, and fathers intervening in ways that were perceived as overbearing or overcontrolling. This could deprive children of opportunities trefine skills in resolving negative feelings and navigating threatening situations (see McLeod et al., 2007). In the context of specific phobias, children may not receive the encouragement and/or autonomy tapproach or manage proximity with feared stimuli from their fathers. This reasoning matches work by Kiff and colleagues (2011a) which found evidence for differential responding ta similar treatment; more specifically, children had poorest outcomes with internalizing problems when they had lower effortful control and when mothers used negative forms of parenting. The current project expands this focus by addressing children’s severity with specific phobias alongside their broader fear levels. Further, this project extends this earlier work with an explicit focus on fathers, whare important tconsider in the context of child anxieties (e.g., Bögels & Phares, 2008; Lazarus et al., 2016), but remain understudied.

Alternatively, with mothers, children lower in negative affectivity showed more variability in fear given levels of maternal overprotection with children reporting the least fear when mothers showed less overprotection (see Figure 2). Children higher in negative affectivity had relatively high fear irrespective of overprotective parenting practices, but there was clear evidence for fit with less use of maternal overprotection and children having lesser temperamental difficulty with negative affectivity. That is, mothers may be overwhelming children whrequire relatively less assistance in managing distress including during anticipation or exposure tfeared stimuli. Mothers could be well-intentioned and even using approaches that in lower levels promote children’s emotional adjustment (i.e., responsive parenting); yet, as with families seeking treatment for children’s externalizing problems, an over-abundance of “positive” parenting approaches when children have relatively fewer regulatory problems could introduce other stresses between parent and child (e.g., Dunsmore et al., 2016).

These findings reinforce twpoints. First, there is evidence for fit between child temperament and parenting behaviors in considering clinical outcomes for children with specific phobias. Second, parent—but not necessarily child—gender may be more salient in considering aspects of fit and provided nuances that were not apparent when considering main effects involving fathers and mothers. Even with these findings, the role of parent-gender as a moderator of clinical intervention response remains preliminary and needs further inquiry.

Overall, our findings are novel relative tpast studies given that previous literature on both temperament and familial influences has largely neglected how these variables affect treatment outcome measures with children this age as well as in the context of specific phobias. Further, this project considered multiple agents of influence in children and in parents, extending focus between topics of research that tends tbe siloed. This work reinforces and extends existing research on the implications of child temperament (Salters-Pedneault et al., 2006) and parental behaviors (Creswell et al., 2008; Liber et al., 2008) of clinical outcomes in anxiety disorders through a multi-informant and multi-method approach.

Implications for Clinical Intervention

We believe an understanding of the relationships between child temperament and parental behaviors offers important implications for the treatment of specific phobias in children. We further maintain that even the best-supported clinical interventions could show limitations if failing taddress particular challenges in children’s regulation or accounting for the behaviors parents will continue tshow both within and beyond treatment sessions. Hence, we argue that by systematically addressing goodness-of-fit between child-centered and parent-centered variables, clinicians and researchers will have better insights intrefining promising interventions and anticipating adjustments that might likely promote treatment response and lasting treatment benefits for children.

This direction is underscored by work addressing goodness-of-fit in community settings. For example, in studying mother and day care provider reports of children in the Netherlands (ages 6–30 months), De Schipper and colleagues (2004) found support for interactions between reported child ‘temperamental difficultness’ (i.e., difficulty managing distress) and children’s caregiver arrangements (i.e., ratiof child-caregiver availability, stability of childcare services) for well-being and internalizing symptoms. Children had highest well-being when they had more trusted caregivers and lower temperamental difficultness. Further, children had more internalizing problems when they had less stable childcare arrangements and higher temperamental difficultness. By collecting pre-treatment indicators addressing possible fit, researchers and clinicians can gain insights intpotential trajectories of clinical change given fit (e.g., Prinzie et al., 2003) and change in factors relevant for fit (e.g., parenting behaviors; Booker, Capriola-Hall, Dunsmore, Greene, & Ollendick, 2018). By incorporating a focus on family-level goodness-of-fit, research may continue tprovide rich insights that extend across specific intervention outcomes (i.e., specific phobia symptom severity) tmore general outcomes relevant tchildren’s daily functioning (i.e., broader fearfulness, global clinical adjustment).

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study included limitations which should be addressed in future studies. First, there was a lack of sample diversity with respect trace and socioeconomic status. Most of the sample was of European descent and predominantly from middle-to-upper-income families. Another limitation is that this study was limited tour brief, intensive treatment and, as a result, may not generalize tother responses tmore standard 12-to-16 session CBT interventions (Grills-Taquechel & Ollendick, 2012). Shorter interventions have promising scalability and the potential tbe directed toward more children sooner (see Milat, King, & Bauman, 2013); however, treatments with more scheduled sessions can provide opportunities treinforce earlier sessions and identify lingering difficulties for children and families for improved long-term success. Similarly, we considered only one follow-up period. We were purposeful in focusing on initial post-treatment given the preliminary nature of our research questions in this clinical context. However, this work will need tbe replicated and extended tconsiderations of long-term trajectories of child functioning. Further, we found a relatively modest internal consistency for children’s reports of their mother’s overprotection on the Parent Bonding Inventory. It is possible that children in this sample had difficulty with managing similar values between positively scored and reversed-scored items or that these items may not reflect a unitary construct. Further, there were concerns of power given the complexity of our models given the sample size. We felt it was important taccount for relevant covariates in attempting tmake claims regarding the importance of child- and parent-factors and used estimation approaches that address missing data. However, larger sample sizes and thorough replication are still needed for this work. In our study, we were unable texplicitly address bidirectionality and transactional effects. The treatments in this project were not aimed at changing parenting behaviors directly, and the shorter follow-up period made it unlikely for meaningful changes in child temperament tbe considered. However, future research should address whether caregiver influences on development may be enhanced by considering the role of child factors like temperament in shaping and conditioning parenting practices (see Kiff et al., 2011b) in the clinical context. Given the sample size, we were not able tconsider nuances given the content of children’s fears—whether their treated phobia involved animals or situations for example. This additional layer of nuance is worth investigation in future studies, considering the ways certain fears may be shaped by parental or child factors differently. Future studies should include observational measures of parenting behaviors and child temperament.

Conclusions

This study is the first tdetermine how the interplay of child temperament and perceived parenting practices affect treatment outcomes for youth with specific phobias. Our study benefited from the use of multiple reporters (children, mothers, fathers, and clinicians) tprovide multiple perspectives on child outcomes and parenting factors and addressed these issues in a carefully diagnosed sample. In considering pre-treatment reports of child negative affectivity, we found main effects for children’s post-treatment specific phobia symptom severity and global clinical adjustment. We alsfound support for interactions between child- and parent-factors. The directions of these interactions differed between fathers and mothers. Children with more temperamental problems benefited from fathers’ lower overprotection and children with fewer temperamental problems were hindered by mothers’ greater overprotection. Findings point tthe importance of family fit for children’s specific phobia interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding. This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, Grant R01MH074777.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have nconflicts of interest.

Ethics statement. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the overseeing Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

McDonald’s omega, rather than Cronbach’s alpha, was used tdetermine internal consistencies in the current study. This coincides with a broader shift in the field away from alphas, which depend on a larger set of assumptions that are typically not met with many measures (i.e., unidimensionality, sensitity of items), and biased estimated when assumptions are violated. Omega estimates incorporate fewer assumptions and show attenuated biases relative talphas (see Dunn, Baguley, & Brunsden, 2014).

CGAS scores from 41–50 indicate moderate impairment in functioning in most domains and severe impairment in at least one domain, such as communication. CGAS scores from 81–90 indicate adequate functioning in all areas (see Wagner et al., 2007).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up tdate and smay therefore differ from this version.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (DSM-IV). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Arcus D, & Kagan J (1995). Temperament and craniofacial variation in the first twyears. Child Development, 66, 1529–1540. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00950.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels S, & Phares V (2008). Fathers’ role in the etiology, prevention and treatment of child anxiety: A review and new model. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 539–558. 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels S, Stevens J, & Majdandžić M (2011). Parenting and social anxiety: Fathers’ versus mothers’ influence on their children’s anxiety in ambiguous social situations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 599–606. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02345.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM, & van Melick M (2004). The relationship between child-report, parent self-report, and partner report of perceived parental rearing behaviors and anxiety in children and parents. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 1583–1596. https://doi.org/10/dr4kjn [Google Scholar]

- Booker JA, Capriola-Hall NN, Dunsmore JC, Greene RW, & Ollendick TH (2018). Change in maternal stress for families in treatment for their children with oppositional defiant disorder. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 2552–2561. 10.1007/s10826-018-1089-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR, & Hall JA (1993). Gender and emotion in context In Lewis M, Haviland JM, & Barrett LF (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 89–121). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Capriola NN, Booker JA, & Ollendick TH (2017). Profiles of temperament among youth with specific phobias: Implications for CBT outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 1449–1459. 10.1007/s10802-016-0255-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell C, Willetts L, Murray L, Singhal M, & Cooper P (2008). Treatment of child anxiety: An exploratory study of the role of maternal anxiety and behaviours in treatment outcome. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 15, 38–44. 10.1002/cpp.559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TE III, Ollendick TH, & Öst L-G (2019). One-Session treatment of specific phobias in children: Recent developments and a systematic review. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15, 233–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, & Fox NA (2007). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: Multiple levels of a resilience process. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 729–746. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw SS, & Mervielde I (2011). The role of temperament and personality in problem behaviors of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 277–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schipper JC, Tavecchio LWC, Van Ijzendoorn MH, & Van Zeijl J (2004). Goodness-of-fit in center day care: Relations of temperament, stability, and quality of care with the child’s adjustment. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 19, 257–272. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2004.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn TJ, Baguley T, & Brunsden V (2014). From alpha tomega: A practical solution tthe pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105, 399–412. Doi: 10.1111/bjop.12046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore JC, Booker JA, Ollendick TH, & Greene RW (2016). Emotion socialization in the context of risk and psychopathology: Maternal emotion coaching predicts better treatment outcomes for emotionally labile children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder. Social Development, 25, 8–26. 10.1111/sode.12109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis LK, & Rothbart MK (2001, April). Re vision of the early adolescent temperament questionnaire. Poster presented at the 2001 Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Minneapolis, Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Conradt J, & Petermann F (2000). Frequency, comorbidity, and psychosocial impairment of specific phobia in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 221–231. 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festen H, Hartman CA, Hogendoorn S, de Haan E, Prins PJM, Recichart CG,…Nauta MH (2013). Temperament and parenting predicting anxiety change in cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 289–297. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco LA, & Morris TL (2002). Paternal child-rearing style and child social anxiety: Investigation of child perceptions and actual father behavior. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 4, 259–267. 10.1023/A:1020779000183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grills-Taquechel AE, & Ollendick TH (2012). Phobic and anxiety disorders in youth. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gulley LD, Hankin BL, & Young JF (2016). Risk for depression and anxiety in youth: The interaction between negative affectivity, effortful control, and stressors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 207–218. 10.1007/s10802-015-9997-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Masek B, Henin A, Blakely LR, Pollock-Wurman RA, McQuade J, … Biederman J (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy for 4- t7-year-old children with anxiety disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 498–510. https://doi.org/10/c762qz [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL, Murayama K, Meteyard L, Morris T, & Dodd HF (2019). Early childhood predictors of anxiety in early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47, 1121–1133. 10.1007/s10802-018-0495-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, & Snidman N (1999). Early childhood predictors of adult anxiety disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 46, 1536–1541. 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00137-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane EJ, Braunstein K, Ollendick TH, & Muris P (2015). Relations of anxiety sensitivity, control beliefs, and maternal over-control tfears in clinic-referred children with specific phobia. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 2127–2134. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-0014-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Safford S, Flannery-Schroeder E, & Webb A (2004). Child anxiety treatment: Outcomes in adolescence and impact on substance use and depression at 7.4-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 276–287. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiff CJ, Lengua LJ, & Bush NR (2011a). Temperament variation in sensitivity tparenting: Predicting changes in depression and anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 1199–1212. 10.1007/s10802-011-9539-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiff CJ, Lengua LJ, & Zalewski M (2011b). Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 251–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PJ, Waite P, & Creswell C (2019). Environmental factors in the development and maintenance of anxiety disorders In Pediatric Anxiety Disorders (pp. 101–124). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Dodd HF, Majdandžić M, De Vente W, Morris T, Byrow Y, … & Hudson JL (2016). The relationship between challenging parenting behaviour and childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 784–791. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, & Long AC (2002). The role of emotionality and self-regulation in the appraisal–coping process: Tests of direct and moderating effects. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 23, 471–493. 10.1016/S0193-3973(02)00129-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner JV, & Lerner RM (1994). Explorations of the goodness-of-fit model in early adolescence In Carey WB & McDevitt SC (Eds.), Prevention and early intervention (pp. 161–169). New York: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Lieb R, Wittchen H-U, Höfler M, Fuetsch M, Stein MB, & Merikangas KR (2000). Parental psychopathology, parenting styles, and the risk of social phobia in offspring: A prospective-longitudinal community study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 859–866. 10.1001/archpsyc.57.9.859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liber JM, van Widenfelt BM, Goedhart AW, Utens EM, van der Leeden AJ, Markus MT, & Treffers PD (2008). Parenting and parental anxiety and depression as predictors of treatment outcome for childhood anxiety disorders: Has the role of fathers been underestimated?. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37, 747–758. 10.1080/15374410802359692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Wood JJ, & Weisz JR (2007). Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 155–172. 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meesters C, Muris P, & van Rooijen B (2007). Relations of neuroticism and attentional control with symptoms of anxiety and aggression in non-clinical children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29, 149–158. 10.1007/s10862-006-9037-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, … & Swendsen J (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milat AJ, King L, Bauman AE, & Redman S (2013). The concept of scalability: Increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions intpolicy and practice. Health Promotion International, 28, 285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller EL, Nikolić M, Majdandžić M, & Bögels SM (2016). Associations between maternal and paternal parenting behaviors, anxiety and its precursors in early childhood: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 17–33. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, & Ollendick TH (2002). The assessment of contemporary fears in adolescents using a modified version of the Fear Survey Schedule for Children-Revised. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 16, 567–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Creswell C, & Cooper PJ (2009). The development of anxiety disorders in childhood: An integrative review. Psychological Medicine, 39, 1413–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH (1983). Reliability and validity of the Revised Fear Survey Schedule for Children (FSSC-R). Behavior Research and Therapy, 21, 685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Halldorsdottir T, Fraire MG, Austin KE, Noguchi RJ, Lewis KM, … & Whitmore MJ (2015). Specific phobias in youth: A randomized controlled trial comparing one-session treatment ta parent-augmented one-session treatment. Behavior Therapy, 46, 141–155. 10.1016/j.beth.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, & Grills AE (2016). Perceived control, family environment, and the etiology of child anxiety – Revisited. Behavior Therapy, 47, 633–642. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Tupling H, & Brown LB (1979). A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 52, 1–10. 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1979.tb02487.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, & Fox NA (2005). Temperament and anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 14, 681–706. 10.1016/j.chc.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinzie P, Onghena P, Hellinckx W, Grietens H, Ghesquière P, & Colpin H (2003). The additive and interactive effects of parenting and children’s personality on externalizing behaviour. European Journal of Personality, 17, 95–117. 10.1002/per.467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Ellis LK, & Rothbart MK (2001). The structure of temperament from infancy through adolescence In Eliasz A & Angleitner A (Eds.), Advances in Research on Temperament (pp. 165–182). Lengerich, Germany; Pabst Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Schniering CA, & Hudson JL (2009). Anxiety disorders during childhood and adolescence: Origins and treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 311–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK (2007). Temperament, development, and personality. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 207–212. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00505.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salters-Pedneault K, Roemer L, Tull MT, Rucker L, & Mennin DS (2006). Evidence of broad deficits in emotion regulation associated with chronic worry and generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30, 469–480. https://doi.org/10/ct6w77 [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Snidman NC, & Kagan J (1999). Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 1008–1015. https://doi.org/10/fczjpp [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, & Aluwahlia S (1983). A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS). Archives of General Psychiatry, 40, 1228–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, & Albano AM (1996). Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (Child and Parent Versions). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, & Moreno J (2005). Specific phobia. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 14, 819–843. 10.1016/j.chc.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Chess S, & Birch HG (1968). Temperament and behaviour disorders in children. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Der Bruggen CO, Stams GJJ, & Bögels SM (2008). Research Review: The relation between child and parent anxiety and parental control: A meta- analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 1257–1269. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven M, Bögels SM, & van der Bruggen CC (2012). Unique roles of mothering and fathering in child anxiety; moderation by child’s age and gender. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 331–343. 10.1007/s10826-011-9483-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort L, Wolters LH, Hogendoorn SM, Prins PJ, de Haan E, Boer F, & Hartman CA (2011). Temperament, attentional processes, and anxiety: Diverging links between adolescents with and without anxiety disorders? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40, 144–155. 10.1080/15374416.2011.533412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A, Lecavalier L, Arnold LE, Aman MG, Scahill L, Stigler KA, … Vitiello B (2007). Developmental disabilities modification of the Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 504–511. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, McLeod BD, Sigman M, Hwang W, Chu BC, 2003. Parenting and childhood anxiety: Theory, empirical findings, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 44, 134–151. 10.1111/1469-7610.00106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]