Abstract

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC)-derived small extracellular vesicles (sEV) but not fibroblast sEV provide retinal ganglion cell (RGC) neuroprotection both in vitro and in vivo, with miRNAs playing an essential role. More than 40 miRNAs were more abundant in BMSC-sEV than in fibroblast-sEV. The purpose of this study was to test the in vitro and in vivo neuroprotective and axogenic properties of six candidate miRNAs (miR-26a, miR-17, miR-30c-2, miR-92a, miR-292, and miR-182) that were more abundant in BMSC-sEV than in fibroblastsEV. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-2 expressing a combination of three of the above candidate miRNAs were added to heterogenous adult rat retinal cultures or intravitreally injected into rat eyes one week before optic nerve crush (ONC) injury. Survival and neuritogenesis of βIII-tubulin+ RGCs was assessed in vitro, as well as the survival of RBPMS+ RGCs and regeneration of their axons in vivo. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness (RNFL) was measured to assess axonal density whereas positive scotopic threshold response electroretinography amplitudes provided a readout of RGC function. Qualitative retinal expression of PTEN, a target of several of the above miRNAs, was used to confirm successful miRNA activity. AAV2 reliably transduced RGCs in vitro and in vivo. Viral delivery of miRNAs in vitro showed a trend towards neuroprotection but remained insignificant. Delivery of selected combinations of miRNAs (miR-17–5p, miR-30c-2 and miR-92a; miR-92a, miR-292 and miR-182) before ONC provided significant therapeutic benefits according to the above measurable endpoints. However, no single miRNA appeared to be responsible for the effects observed, whilst positive effects observed appeared to coincide with successful qualitative reduction in PTEN immunofluorescence in the retina. Viral delivery of miRNAs provides a possible neuroprotective strategy for injured RGCs that is conducive to therapeutic manipulation.

Keywords: Retinal ganglion cells, miRNA, Optic nerve crush, Exosomes, PTEN, Adeno-associated virus, neuroprotection

1. Introduction

Neurons of the mammalian central nervous system (CNS) suffer from an intrinsic inability to regenerate their axons after injury, a characteristic that underpins the associated functional deficits. Due to the diencephalic origin of the optic vesicles during development, the retina is considered an outgrowth of the brain and thus, a CNS structure. Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are the final stage in the phototransductive pathway and their axons make up the optic nerve. Damage to the optic nerve may lead to irreversible blindness and is often used not just as a model for traumatic optic neuropathy but also for spinal cord injury.

Delivery of neurotrophic factors (NTF) has proven inefficient in promoting long-term neuroprotection, likely because of two reasons: (1), the need for frequent administration and in combination; and (2), the subsequent down-regulation of their receptors after treatment. Delivery of cells, those that release NTF naturally (Johnson et al., 2010; Mead et al., 2016; Mead et al., 2013) or those that have been modified to release glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and ciliary neurotrophic factor (Flachsbarth et al., 2018) addresses the longevity issue. In contrast, to address the receptor down-regulation problem, delivery of a virus to induce the expression of both brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor TrkB in RGCs promotes neuroprotection after ONC and laser-induced glaucoma (Osborne et al., 2018). We recently demonstrated that cell therapy, namely bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSC), are effective at protecting RGCs from death via the exosomes/small extracellular vesicles (sEV) they secrete and in particular, the microRNAs (miRNAs) contained within (Mead et al., 2018; Mead and Tomarev, 2017).

miRNAs are short non-coding RNA that mediate the knockdown and silencing of mRNA via the guiding of Argonaute (AGO) proteins to target sites complementary to the miRNA sequence (Reviewed in Gebert and MacRae, 2018). Approximately 2500 miRNAs have been identified in humans and their importance is underpinned by the lethality of Dicer/Drosha knockout. Drosha is necessary for the conversion of pri-miRNA to pre-miRNA whereas Dicer cleaves the premiRNA into mature miRNA ready for loading into the AGO complex. The most highly expressed of the AGO proteins is AGO2 and is considered the integral component of the RNA-induced silencing complex (Liu et al., 2004). Knockdown of AGO2 perturbs the neuroprotective and neuritogenic efficacy of BMSC exosomes on injured RGCs (Mead et al., 2018; Mead and Tomarev, 2017; Zhang et al., 2016).

Deviations in the expression of miRNA have been associated with several neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson’s, Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s disease (Reviewed in Rajgor, 2018). For example, in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, release of miR-218 from motor neurons can disrupt the function of nearby astrocytes and contribute to the disease pathology (Hoye et al., 2018). In experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, lumbar motor neurons and retinal neurons displayed a differential expression of 14 miRNA in comparison to healthy animals (Juźwik et al., 2018).

While miRNAs downregulate mRNA and thus subsequently the encoded proteins, the overall effect can still be an activation of discrete signalling pathways. One relevant example in the field of axon regeneration is phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), a suppressor of the pro-regenerative mTOR/PI3K/Akt pathway. PTEN knockdown promotes axon regeneration in the CNS (Reviewed in Berry et al., 2016). Several miRNAs have been found to target PTEN and subsequently activate the mTOR pathway including miR-214 (Bera et al., 2017), miR-1908 (Xia et al., 2015), miR-494 (Wang et al., 2010) and miR-21 (Sayed et al., 2010). Indeed exosomes derived from MSC promote regeneration of cortical neurons via activation of the mTOR pathway (Zhang et al., 2016). In a model of glaucoma, inhibitors of miR-149 were shown to be RGC neuroprotective along with an associated upregulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway (Nie et al., 2018). Delivery of miRNA via Schwann cell-derived exosomes into cultured neurons promoted neuritogenesis, evident by the lack of effect if exosomes were ablated of RNA (Ching et al., 2018). Candidate miRNAs included miR-21, miR-222, miR18a and miR182.

In the present study we expressed combinations of six candidate miRNAs (miR-26a, miR-17, miR-30c-2, miR92a, miR-292, and miR-182) using self-complimentary adeno-associated virus (AAV)-2 in the RGCs of rats that have undergone a crush injury to the optic nerve and assessed survival, regeneration and functional preservation. These candidates were chosen based on their abundance in the neuroprotective BMSC-derived sEV in comparison to the ineffective fibroblast-derived sEV.

2. Materials and Methods

All reagents were purchased from Sigma (Allentown, PA) unless otherwise specified.

2.1. Animals

Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 200–220 g (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were maintained in accordance with guidelines described in the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, using protocols approved by the National Eye Institute Committee on the Use and Care of Animals.

Animals were kept at 21°C and 55% humidity under a 12 hours light and dark cycle, given food/water ad libitum and were under constant supervision from trained staff. Animals were euthanized by rising concentrations of CO2 before extraction of retinae.

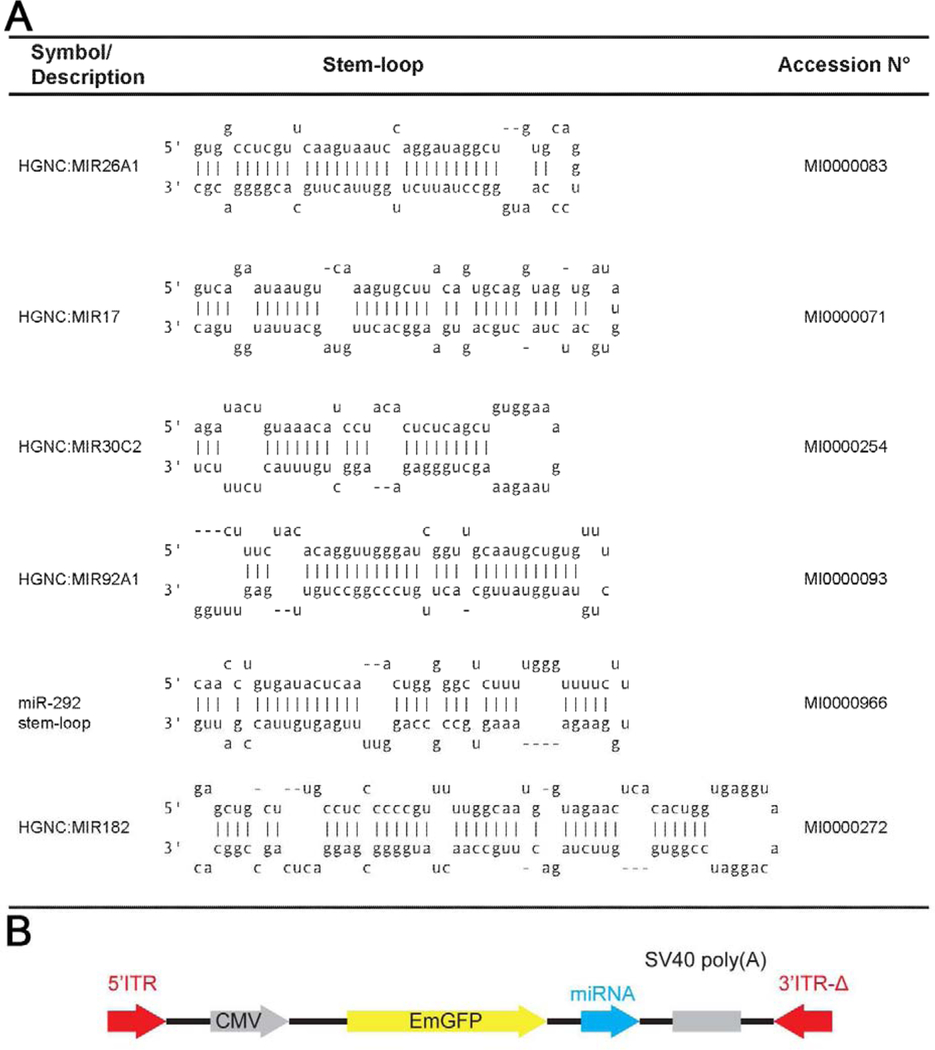

2.2. Plasmid and AAV production

Backbone for all miRNA constructs is the pscAAV-CMV-ΔelD, modified plasmid used in a previous publication (Kole et al., 2018) but lacking the D-element in 3’ITR sequence. Cassette of EmGFPmiR_NegControl (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cincinnati, OH; #K4936–00) was subcloned into pscAAV-CMV -ΔelD using Gateway® recombination reactions. miRNA loci tested (Table 1) were obtained from miRBase http://mirbase.org/. Individual loci containing a single miRNA stem-loop were generated as PCR primers containing a complementary single-stranded DNA sequence and extended via high-fidelity PCR as one cycle of 15 seconds at 95°C followed by annealing for 15sec at 62°C and extension at 72°C for 15 sec. Double stranded sequences were subcloned using restriction enzymes SalI and EcoRV into pscAAV-CMVEmGFPmiR_NegControl-ΔelD vector by replacing the miR_NegControl sequence. Each miRNA sequence was validated by sequencing analysis. Self-complementary AAV production were generated as described (Kole et al., 2018). Importantly, self-complementary AAV vectors induce replication/translation much faster (2 days) than conventional AAV vectors (4 weeks). While conventional AAV vectors require the host cell to synthesize the second complementary strand from its palindromic inverted terminal repeats, self-complementary AAV vectors include this second strand and thus ignore this rather significant rate-limiting step (McCarty, 2008). Briefly, HEK 293T cells were triple transduced with pHelper, pAAV2cap, and pscAAV2-CMV-(GFPmiRNA) plasmids using polyethylenimine. For increasing the screening scale, each viral batch contained the combinations of three different pscAAV2-CMV-(GFPmiRNA) constructs and are referred to as virus collection A-E in Table 2. The iso-molar combination of plasmids is expected to generate same number of viral particles of each GFPmiRNA. Cells were harvested 48 h after transduction. Viral particles were purified by centrifugation through iodixanol gradient (15, 25, 40, and 60%). The 40% fraction containing the AAV viral particles was collected and passed through the column for desalting. Viral particles were suspended and stored in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 0.001% pluronic (Thermo Fisher Scientific; #24040) which prevents attachment of virus to pipette or tube. Titers (viral genomes per ml - vg/ml) were determined by real time PCR using the primers targeting the CMV promoter: 5’-ATGCGGTTTTGGCAGTACAT-3’ and 5’-GTCAATGGGGTGGAGACTTG-3’.

Table 1:

Sequences for the tested miRNA (A) and diagram of the virus construct used (B).

|

Table 2:

Virus constructs (pscAAV2-CMV-(GFPmiRNA)) used in the present study. Virus collection E refers to a combination of both virus collection A and virus collection D.

| miRNA | Virus (GFP) |

Virus collection A |

Virus collection B |

Virus collection C |

Virus collection D |

Virus collection E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EmGFPmiR | + | |||||

| −NegControl | ||||||

| miR-26a | + | + | ||||

| miR-17 | + | + | + | |||

| miR-30c-2 | + | + | + | + | ||

| miR-92a | + | + | + | + | ||

| miR-292 | + | + | + | |||

| miR-182 | + | + |

2.3. Adult rat retinal cell culture

Eight-well chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were pre-coated with 100 μg/ml poly-D-lysine/20 μg/ml laminin for 60/30 minutes respectively. After culling and ocular dissection, retinal cells were dissociated into single cells using a Papain Dissociation system according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Worthington Biochem, Lakewood, NJ) and as described previously (Logan et al., 2006). Retinal cells were seeded at 125,000 cells/well in 8-well chamber slides and grown in 300μl of supplemented Neurobasal-A (25 ml Neurobasal-A (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1X concentration of B27 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.5 mM of L-glutamine (62.5 μl; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 50 μg/ml of gentamycin (125 μl; Thermo Fisher Scientific)). Cultures were treated with virus collection A, B, C, D, or E which contained 1×1011 vg/ml in sterile PBS, 0.001% pluronic in a final volume of 5 μl (Table 2). All in vitro experiments were run in triplicate from pooled retinae from 2 animals and repeated on three independent occasions (total of 6 separate animals).

Cultures were incubated for 3 days at 37°C before immunocytochemical staining of RGCs with βIII-tubulin to stain cell soma and neurites (Logan et al., 2006). For this study, large spherical βIII-tubulin+ retinal cells, which can be identified by their preferential βIII-tubulin intensity around the axonal base, are referred to as RGCs. Previous immunocytochemical analysis of these cultures demonstrates that 60% of these retinal cells are neurons (neurofilament+/βIII-tubulin+), of which 10% are Thy1+ RGCs (Suggate et al., 2009).

2.4. In vivo experimental design

Twenty female Sprague-Dawley rats (40 eyes) weighing at 200–220g (~8 weeks) were split into 8 groups (5 eyes per group) based on our previous a priori power calculations (Mead et al., 2014). One group was left intact while the other 7 groups received an optic nerve crush (ONC) on day 0. Intravitreal injection of AAV was given 7 days prior to ONC/day 0 and the experiment finished on day 21. Electroretinography (ERG) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) recording were also done 7 days prior to ONC/day 0 as well as on day 20.

2.5. Optic nerve crush

Anaesthesia was induced with 5%/95% Isoflurane/O2 (Baxter Healthcare Corp, Deerfield, IL)/1.5L per minute and maintained at 3.5% throughout the procedure whilst analgesia was provided via an intraperitoneal injection of Buprenorphine (0.3 mg/kg). Intraorbital ONC was performed as previously described (Berry et al., 1996). Briefly, the optic nerve was surgically exposed under the superior orbital margin and crushed using fine forceps 1 mm posterior to the lamina cribrosa, taking care to separate the dura mater and under lying retinal artery before crushing.

2.6. Intravitreal injection

All virus collections (Table 2) were delivered at a concentration of 1×1011 vg/ml and in a final volume of 5 μl in sterile PBS, 0.001% pluronic, 7 days prior to ONC. Intravitreal injections, posterior to the limbus, were performed under isoflurane-induced anaesthesia (described above) using a pulled glass micropipette, produced from a glass capillary rod (Harvard Apparatus, Kent, UK) using a Flaming-Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) with care taken not to damage the lens.

2.7. Confirmation of AAV-miRNA expression

Each AAV expressing Hsa-mir-17, Hsa-mir-30c-2 and Hsa-mir-92a-1 coexpressed with EGFP was intravitreally injected to the left eye of a rat. The right eye was used as the control by injecting PBS. Two weeks later, the retina was dissected and efficiency of transduction was confirmed following the EGFP expression. Total RNA were isolated and served for cDNA synthesis and Q-PCR analysis to analyze the expression of each miRNA.

Three AAV expressing Hsa-mir-17, Hsa-mir-30c-2 or Hsa-mir-92a-1 were selected for the confirmation of miRNA expression. Corresponding AAV were intravitreally injected into the left eye, while the right eye, injected with PBS, was used as the control. Two weeks later, the retina was dissected, and efficiency of transduction was confirmed following the EGFP expression. Total small RNA was isolated from the retina using the mirVana miRNA isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The quality of isolated small RNA and the absence of large RNA contamination were validated using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent). Total small RNA was used as a template for cDNA synthesis. cDNA synthesis and Q-PCR analysis were performed using miRCURY LNA miRNA Custom PCR Assays (Qiagen). Each cDNA sample (retina injected with PBS, Hsa-mir-17-AAV, Hsa-mir-30c-2-AAV or Hsa-mir-92a-1-AAV) was tested for Hsamir-17, Hsa-mir-30c-2 and Hsa-mir-92a-1 expression by Q-PCR. Fold inductions of each miRNA in AAV-injected retina versus PBS-injected retina were calculated based on Ct values. Data normalization was performed using the amount of total small RNAs used for each Q-PCR sample.

2.8. Electroretinography

ERG was recorded using the Espion Ganzfeld full field system (Diagnosys LLC, Lowell, MA) 7 days prior to ONC (baseline) and 20 days post-ONC. Rats were dark adapted for 12 hours overnight and prepared for ERG recording under dim red light (>630nm). Anaesthesia was induced with intraperitoneal injection of Ketamine (100 mg/kg; Putney Inc, Portland, ME)/Xylazine (10 mg/kg; Lloyd Inc, Shenandoah, IA) and eyes dilated with tropicamide. Scotopic flash ERG was recorded from −5.5 log (cd s) m−2 to 1.0 log (cd s) m−2 in 0.5 log unit increments and traces were analyzed using in built Espion software. Traces at a light intensity of −5.0 log (cd s) m−2 were chosen for analysis as they produced a clean, unambiguous positive scotopic threshold (pSTR) at approximately 100 ms after stimulus, of which the peak amplitude was recorded. All readings and analysis were performed by an individual masked to the treatment groups.

2.9. Optical coherence tomography measurements of the retinal nerve fiber layer

OCT was performed on rats under anaesthesia (Ketamine and Xylazine, as above) 7 days prior to ONC (baseline) and 20 days post-ONC. A Spectralis HRA3 confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) was used to image the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) surrounding the optic nerve head and in-built software segmented the RNFL and quantified the thickness. Segmentation was manually adjusted when necessary (by an individual masked to the treatment group) to prevent inclusion of blood vessels that populate the RNFL.

2.10. Tissue preparation

At 21 days post-ONC, animals were sacrificed with CO2 overdose and perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Eyes and optic nerves were dissected and immersion fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for a further 2 hours at 4°C before cryoprotection in 10%, 20% and 30% sucrose solution in PBS for 24 hours and stored at 4°C. Eyes and optic nerves were embedded using optimal cutting temperature embedding medium (VWR International Inc, Bridgeport, NJ) in peel-away mold containers (VWR International Inc) by rapid freezing with ethanol/dry ice before storage at −80°C. Eyes and optic nerves were sectioned on a CM3050S cryostat microtome (Leica Microsystems Inc, Bannockburn, IL) at −22°C at a thickness of 20 μm and 14 μm, respectively, and mounted on positively charged glass slides (Superfrost Plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Parasagittal eye and optic nerve sections were left to dry onto slides overnight at 37°C before storage at −20°C. To ensure RGC counts were taken in the same plane, eye sections were chosen with the optic nerve head visible.

2.11. Immunocytochemistry

Retinal cultures were fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 10 minutes, washed for 3 × 10 minutes of PBS, blocked in blocking solution (3% bovine serum albumin (g/ml), 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 20 minutes and incubated with primary antibody (βIII-tubulin, 1:500, Sigma, #T-8660)) diluted in antibody diluting buffer (ADB; 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.3% Tween-20 in PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature. Cultures were washed for 3 × 10 minutes in PBS, incubated with the secondary antibody (Mouse IgG 488, 1:400, ThermoFisher, #A-11001) diluted in ADB for 1 hour at room temperature, washed for 3 × 10 minutes in PBS, mounted in Vectorshield mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and stored at 4°C.

2.12. Immunohistochemistry

Mounted tissue sections were equilibrated to room temperature, washed in PBS for 2 × 5 minutes, permeabilised in 0.1% Triton x-100 in PBS for 20 minutes and washed for 2 × 5 minutes in PBS. Sections were blocked in blocking buffer (75 μl; 0.5% bovine serum albumin (g/ml), 0.3% Tween-20, 15% normal goat/donkey serum (Vector Laboratories) in PBS) in a humidified chamber for 30 minutes and incubated with primary antibody (RNA-binding protein with multiple splicing (RBPMS), 1:500, ThermoFisher, #ABN-1376; growth associated protein-43 (GAP-43), 1:400, ThermoFisher, #33–5000; AAV, 1:200, ThermoFisher, #AB-PA1–4106) diluted in ADB (15% normal goat serum in place of bovine serum albumin) overnight at 4°C. The following day, slides were washed for 3 × 5 minutes in PBS and incubated with secondary antibody (Mouse IgG 488, 1:400, ThermoFisher, #A11001; Guinea Pig IgG 546, 1:400, ThermoFisher, #A-11074) diluted in ADB for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were washed for 3 × 5 minutes in PBS, mounted in Vectorshield mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and stored at 4°C before microscopic analysis. Negative controls including omission of primary antibody were included in each run and were used to set the background threshold levels prior to image capture.

2.13. Microscopy and analysis

All fluorescently stained sections were analysed by an operator blinded to the treatment groups. For immunocytochemistry, wells were divided into 40 equal boxes and 12 were selected at random. βIII-tubulin+ retinal cells (identified by their staining morphology and referred to from here on as RGCs), with or without neurites, were counted in each selected box. Fluorescently stained cells were analysed using a Zeiss Z1 epifluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc, Thornwood, NY). Neurite outgrowth was measured by dividing the well into 9 equal sectors and the length of the longest neurite of each RGC in each sector was measured using Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss Inc). All in vitro experiments were run in triplicate from pooled retinae from 2 animals and repeated on three independent occasions (total of 6 separate animals).

For immunohistochemistry of retina, RBPMS+ RGCs were counted in 20 μm-thick sections (imaged using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal laser-scanning microscope) along a 250 μm linear region of the ganglion cell layer (GCL) either side of the optic nerve as previously described (Mead et al., 2014). Six sections per retina and 5 retinae (from 5 different animals) per treatment group were quantified. For immunohistochemistry of the optic nerve, GAP-43+ axons were counted in 14 μm thick longitudinal sections, imaged using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal laser-scanning microscope and image composites created using Photoshop CS6 (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA). Note that GFP staining was only present in the RGC soma, not the axon. The number of axons were quantified at 100, 200 and 500 μm distance intervals extending proximal and distal to the laminin+ crush site. Three sections per optic nerve and 5 optic nerves (from 5 different animals) per treatment group were quantified. The diameter of the nerve was measured at each distance to determine the number of axons/mm width. This value was then used to derive ∑ad, the total number of axons extending distance d in an optic nerve with radius r using:

2.14. Statistics

Animal numbers were determined beforehand using a power calculation (Faul et al., 2007; Mead et al., 2014). All statistical tests were performed using SPSS 17.0 (IBM SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) and data presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) with graphs constructed using Graphpad Prism (La Jolla, CA). Normal distribution was verified by Shapiro-Wilkes test prior to parametric testing using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey post-hoc test. Statistical differences were considered significant at p values <0.05.

3. Results

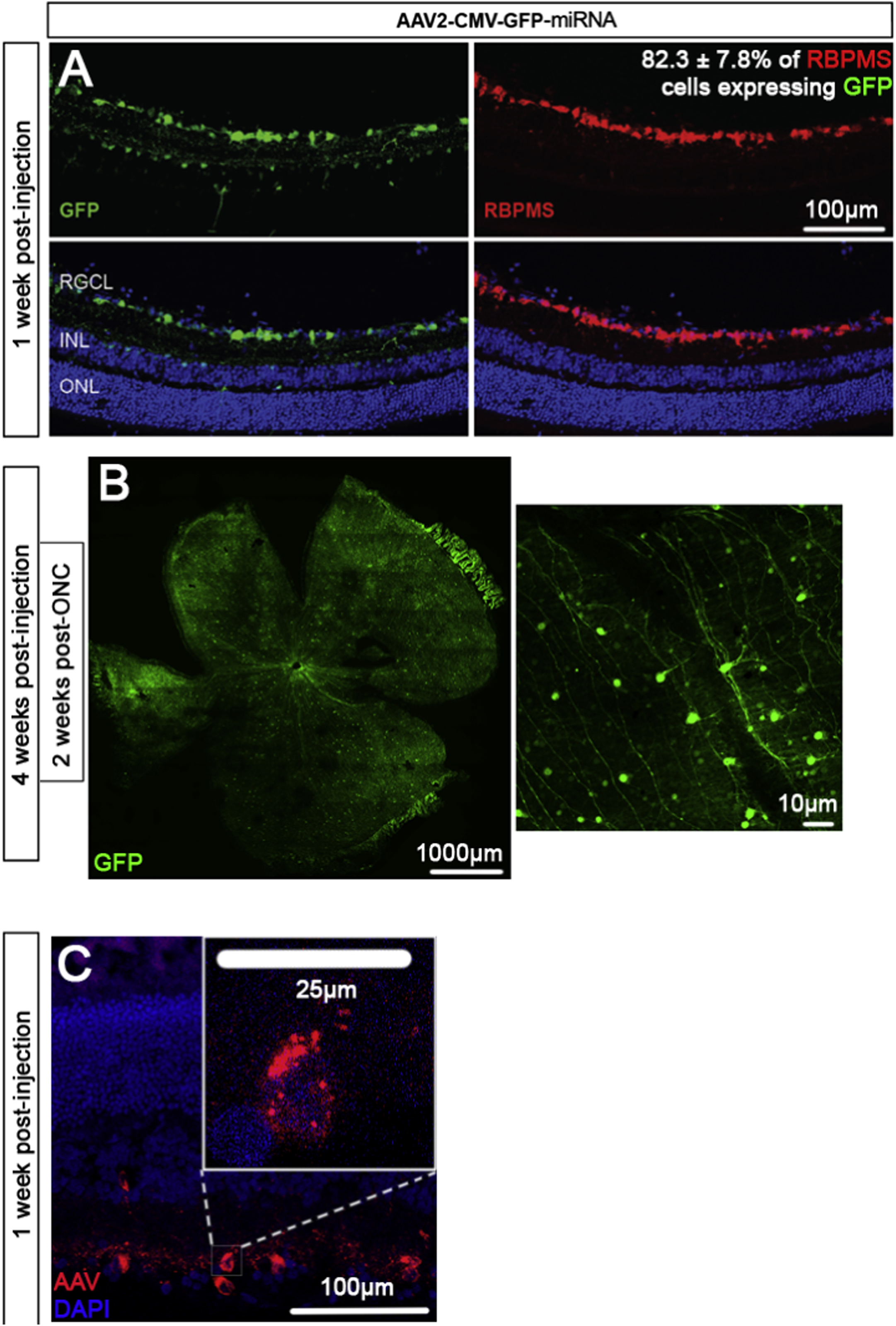

Six miRNAs were selected for testing their therapeutic efficacy. Their selection was based on their abundance in neuroprotective BMSC-derived sEV versus lower abundance in fibroblast-derived sEV. Several of the selected miRNAs (miR-26a, miR-17–5p, miR-92a) were implicated in the down-regulation of PTEN expression (Ding et al., 2017; Li and Yang, 2012; Zhang et al., 2014) and PTEN knockdown was shown to promote RGC neuroprotection and axon regeneration after ONC (Park et al., 2008). Instead of testing the miRNA individually, we combined three miRNA into one AAV collection with a total of 5 different collections/AAV treatments (Table 2). RGCs, like other cells, can be transduced by multiple viral particles. Based on the number of viral particles (5×108) and the number of RGCs in a Sprague Dawley rat (82818 ± 3949) (Salinas-Navarro et al., 2009), there are approximately 6000 particles available per RGC. The actual value is likely considerably lower as it assumes AAV2 is 100% preferential towards the transduction of RGCs and no other retinal cells. Despite this, AAV staining confirms the presence of multiple AAV molecules present per RGC (Figure. 2C) strongly indicating RGCs are transduced by all three miRNA.

Figure 2:

Retinal GFP expression. Representative images and transduction efficiency of retinal sections (A) and retinal wholemounts (B) treated with AAV2 virus expressing GFP (green). Retinal sections are from animals 1-week post-AAV2 injection and counterstained with RBPMS (red) whereas wholemounts are from animals 4-weeks post-AAV2 injection and 2 weeks post-optic nerve crush (ONC). Finally, retinal sections 1-week post-AAV2 injection stained for AAV are shown (C), with a magnified inset demonstrating the extent of transduction in a retinal ganglion cell. Retinal ganglion cell layer (RGCL), inner nuclear layer (INL), and outer nuclear layer (ONL) are labeled. Images representative of 5 animals per group.

3.1. Viral delivery of miRNA promotes a trend towards RGC neuroprotection/neuritogenesis in mixed primary retinal cultures

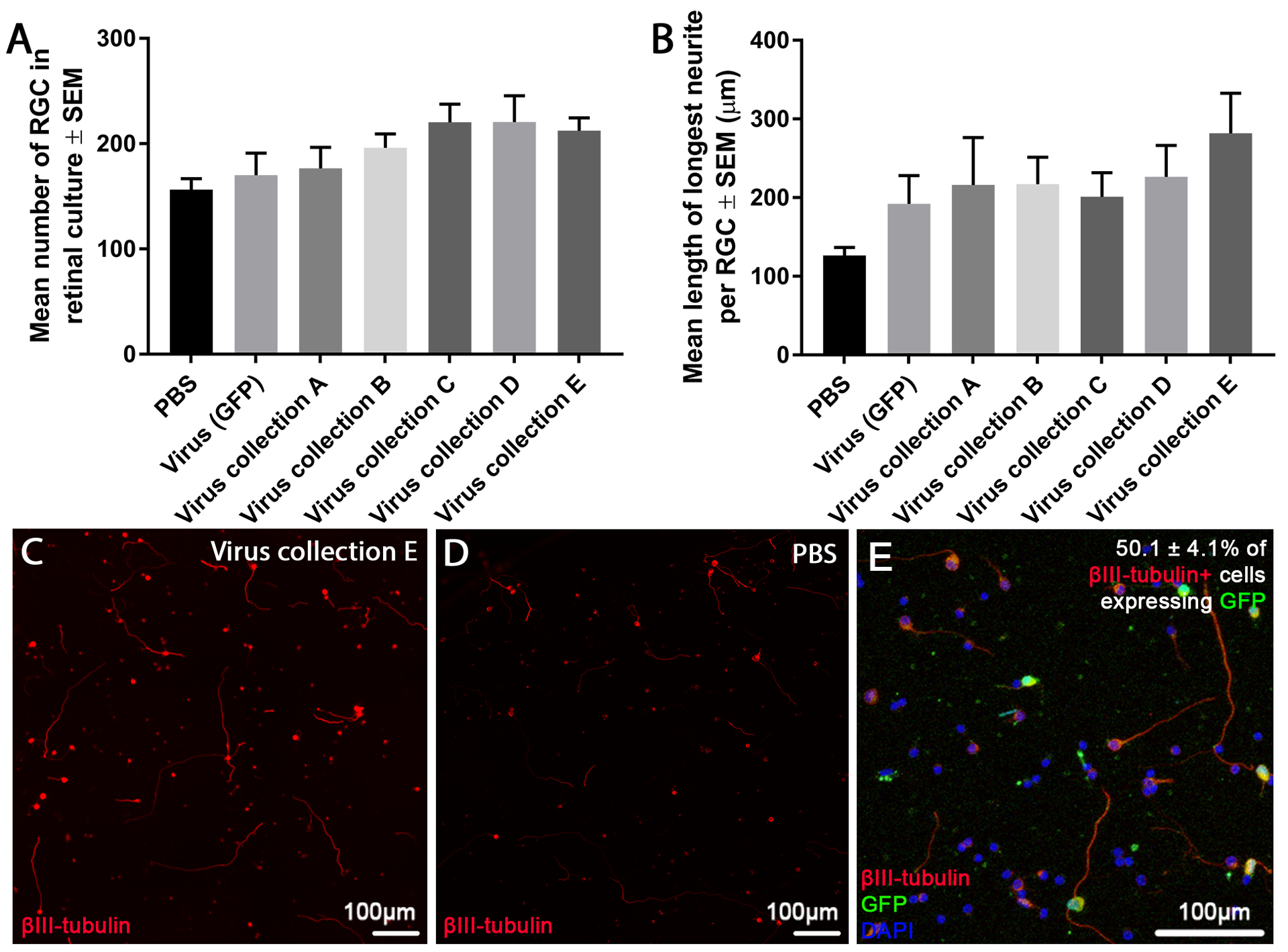

Mixed primary retinal cultures infected with different recombinant AAV were used to test neuroprotective effects of miRNA in vitro. Cultures were kept for 3 days before analysis, in which substantial loss of RGCs is expected. Control experiments showed that AAV2 virus expressing GFP transduced 50.1 ± 4.1% of RGCs (βIII tubulin+ cells) in retinal cultures (Figure. 1E).

Figure 1:

Effects of virally delivered miRNA on RGC neuroprotection/neuritogenesis in culture. The number of surviving βIII-tubulin+ RGCs (A) and the average length of their longest neurite (B) in heterogeneous adult rat retinal cultures treated with different viruses are shown. No significant differences between virus treated and virus (GFP) treated groups was seen. Representative images of retinal cultures treated with virus collection E (C) or PBS (D) are shown. Finally, transduction efficiency is shown via representative in vitro retinal cultures 3 days post-AAV2 treatment, counter stained with βIII-tubulin (green) and DAPI (blue). Images are representative of the 3 separate cultures/3 repeats per culture. Sections were stained with βIII-tubulin (red; scale bar: 100 μm).

Viral delivery of miRNA to these cultures elicited a non-significant trend towards RGC neuroprotection with virus collection C and D promoting the highest (220.3 ± 17.4, 220.6 ± 25.1 RGCs/well, respectively) followed by virus collection A, B and E (176.6 ± 20.1, 196.1 ± 13.2, 212.4 ± 12.3 RGCs/well) in comparison to PBS and virus (GFP) treated controls (156.3 ± 10.5, 170.0 ± 21.1 RGCs/well; Figure. 1A).

Neuritogenesis was measured as the average length of the longest neurite (Figure. 1B). While viral delivery of miRNA (virus collection A, B, C, D and E) trended towards a neuritogenic effect (216.1 ± 60.3, 217.1 ± 34.4, 201.0 ± 30.9, 226.6 ± 40.0, 282.0 ± 50.0 μm, respectively) in comparison to PBS treated controls (126.4 ± 10.3 μm), they did not in comparison to virus (GFP) treated controls (192.1 ± 35.9 μm). Virus (GFP) controls also trended to be more neuritogenic than PBS treated controls. No statistically significant differences were seen.

3.2. Viral delivery of miRNA in vivo

To confirm expression of miRNA after AAV transduction, four groups of RNA samples, from total retina injected with PBS, hsa-mir-17-AAV, hsa-mir-30c-2-AAV and hsa-mir-92a-1-AAV, were tested for each hsa-mir-17, hsa-mir-30c-2 and hsa-mir-92a-1 expression in separate Q-PCR analysis. The injection of hsa-mir-17-AAV did not increase the amount of hsa-mir-17 (Supplementary Figure 1, left), while the injection of hsa-mir-92a-1 increased the amount of hsamir-17. This shows that the hsa-mir-92a-1 may regulate hsa-mir-17 expression. The amount of hsa-mir-30c-2-AAV (middle) and hsa-mir-92a-1 (right) were not changed by any of the tested mir-AAV injection.

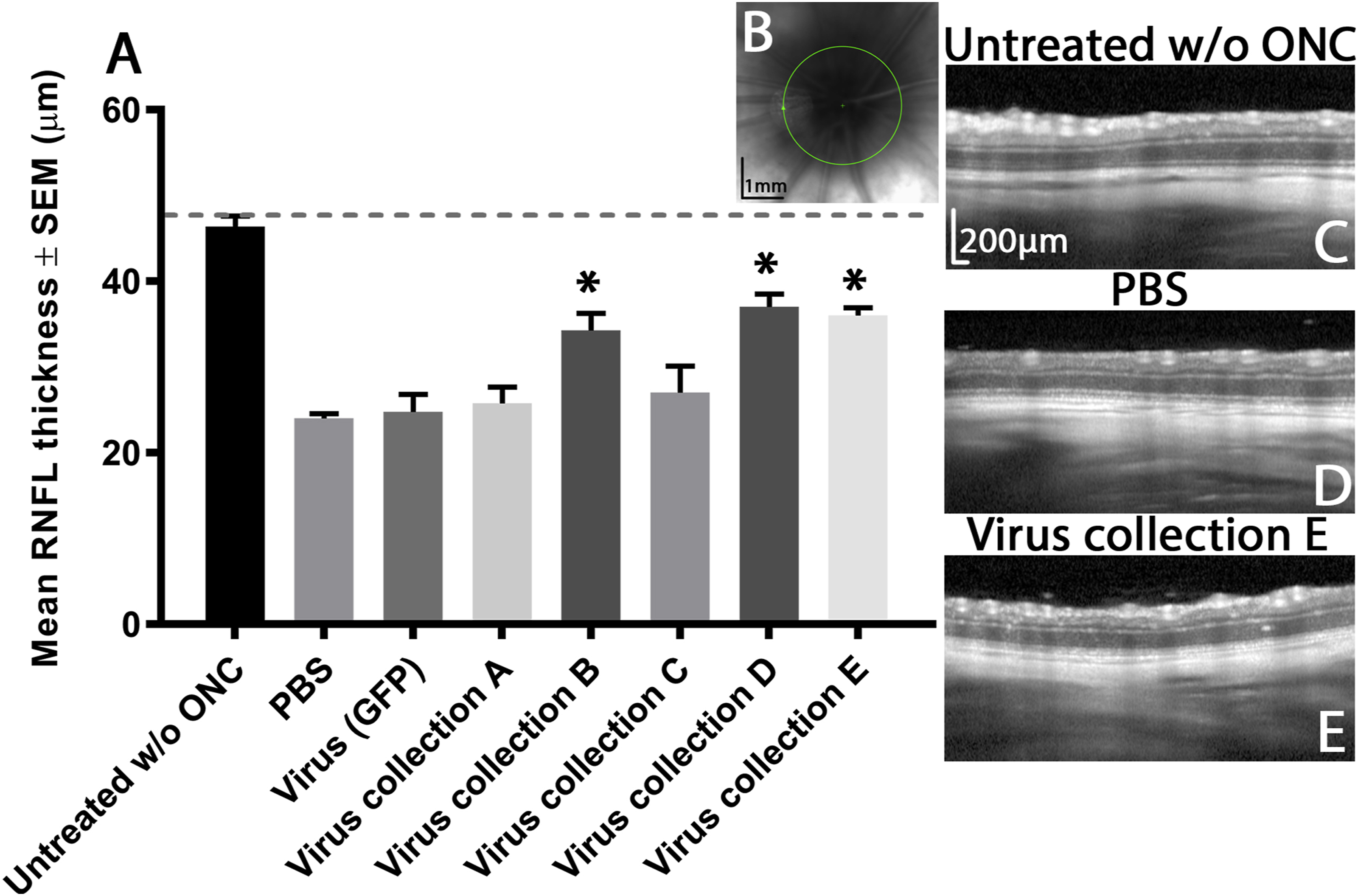

3.3. Viral delivery of miRNA preserves RNFL thickness after ONC

To test neuroprotective effects of miRNA in vivo, an ONC injury model was used with tissues analysed 21 days post-crush. Control experiments demonstrated that AAV2 expressing GFP, administered 7 days before the ONC, transduced 82.3 ± 7.8% RGCs after intravitreal injection in our conditions (Figure. 2A, B).

The thickness of the RNFL was used as a measure of RGC axonal density (Figure. 3) and was recorded as the mean ± SEM (n=5), as were all subsequent in vivo endpoints. Measurements were taken at 7 days before ONC and 20 days post-crush. RNFL thickness measurements accurately correlate with the extent of RGC degeneration after ONC(Mead and Tomarev, 2016). In untreated animals without ONC, RNFL thickness (46.4 ± 1.3 μm) was no different from baseline (47.1 ± 0.5 μm; baseline was day 0 measurement from all animal groups). In animals receiving virus collection A and C, RNFL thickness (25.8 ± 1.9, 27.0 ± 3.1 μm, respectively) was not significantly different from PBS and virus (GFP) treated control animals (24.0 ± 0.6, 24.8 ± 2.1 μm, respectively). In contrast, in virus collection B, D and E treated animals, RNFL thickness (34.3 ± 2.1, 37.0 ± 1.5, 36.0 ± 1.0 μm, respectively) was significantly higher than PBS and virus (GFP) treated control animals.

Figure 3:

RNFL thickness after ONC. Graph depicting the mean average (± SEM) RNFL thickness (μm) of animals before (dashed grey line), and 21 days after ONC (A). Asterisks indicate significant differences (p<0.05) from PBS and virus (GFP) control treated animals. To encapsulate the entirety of the RNFL as it courses towards the optic nerve head, measurements were recorded at this region (B; scale bar 1 mm) and representative images from the 5 animals per group are shown (C,D and E; scale bars 200 μm).

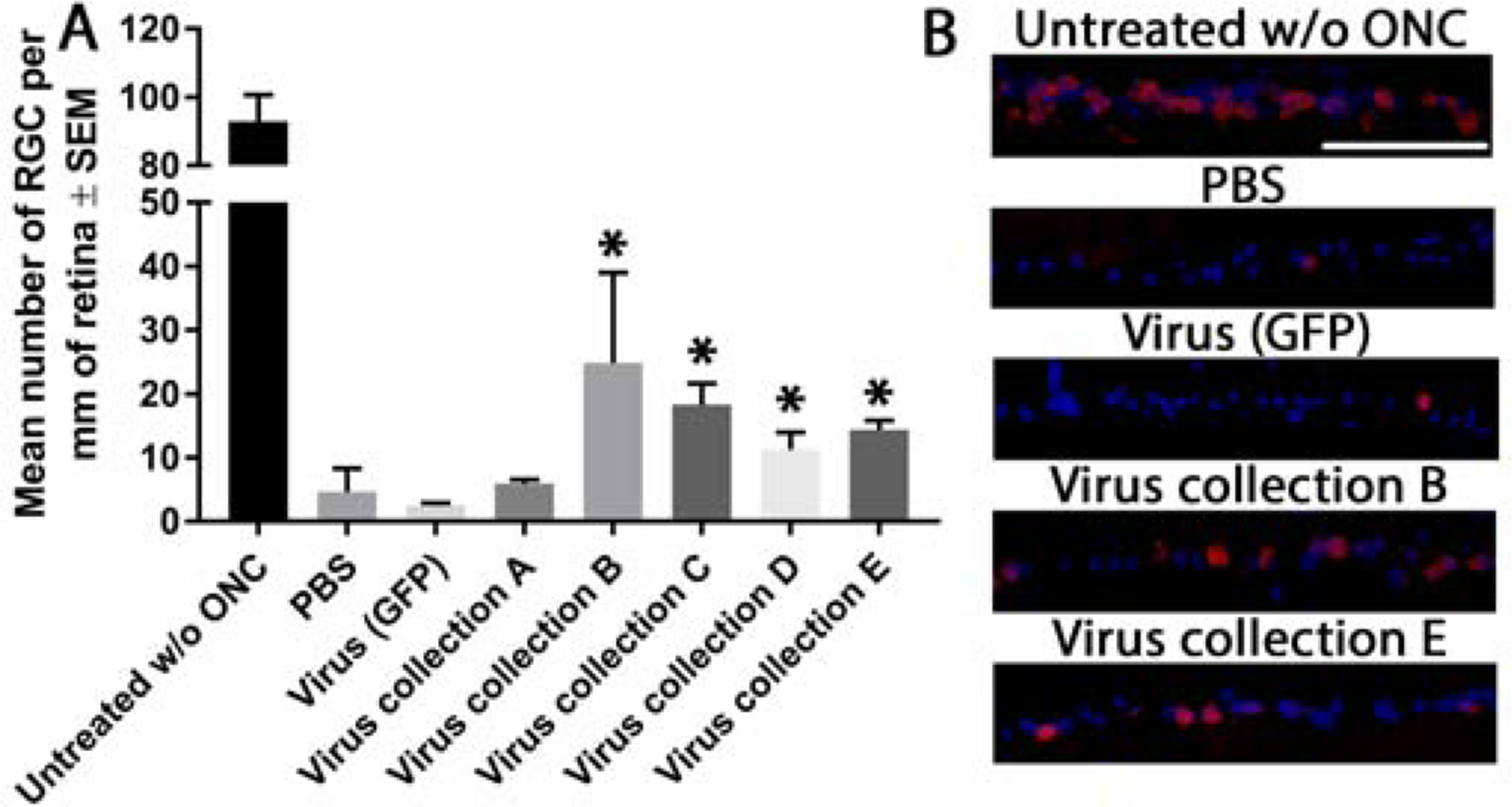

3.4. Viral delivery of miRNA promotes neuroprotection of RGCs following ONC

ONC is characterised by the selective and rapid loss of RGCs. ONC (PBS and virus (GFP) treated control) induced a significant loss of RBPMS+ RGCs by day 21 (4.7 ± 3.7 and 2.5 ± 0.5/mm of retina, respectively) compared to untreated controls without ONC (93.0 ± 7.8/mm of retina; Figure. 4). While intravitreal delivery of virus collection A yielded no neuroprotective effect (6.0 ± 0.6/mm of retina), virus collection B, C, D and E provided significant neuroprotection of RBPMS+ RGCs (24.9 ± 14.2, 18.3 ± 3.4, 11.3 ± 2.7, 14.4 ± 1.5/mm of retina, respectively) compared to PBS and virus (GFP) treated controls.

Figure 4:

RBPMS+ RGC counts after ONC. Graph depicting the number of RBPMS+ RGCs (per mm or retina) 21 days after ONC (A). Asterisks indicate significant differences (p<0.05) from PBS and virus (GFP) control treated animals. Representative images of the ganglion cell layer of retina stained for RBPMS (green) and DAPI (blue) from the 5 animals per groups are shown (B; scale bar 100μm)

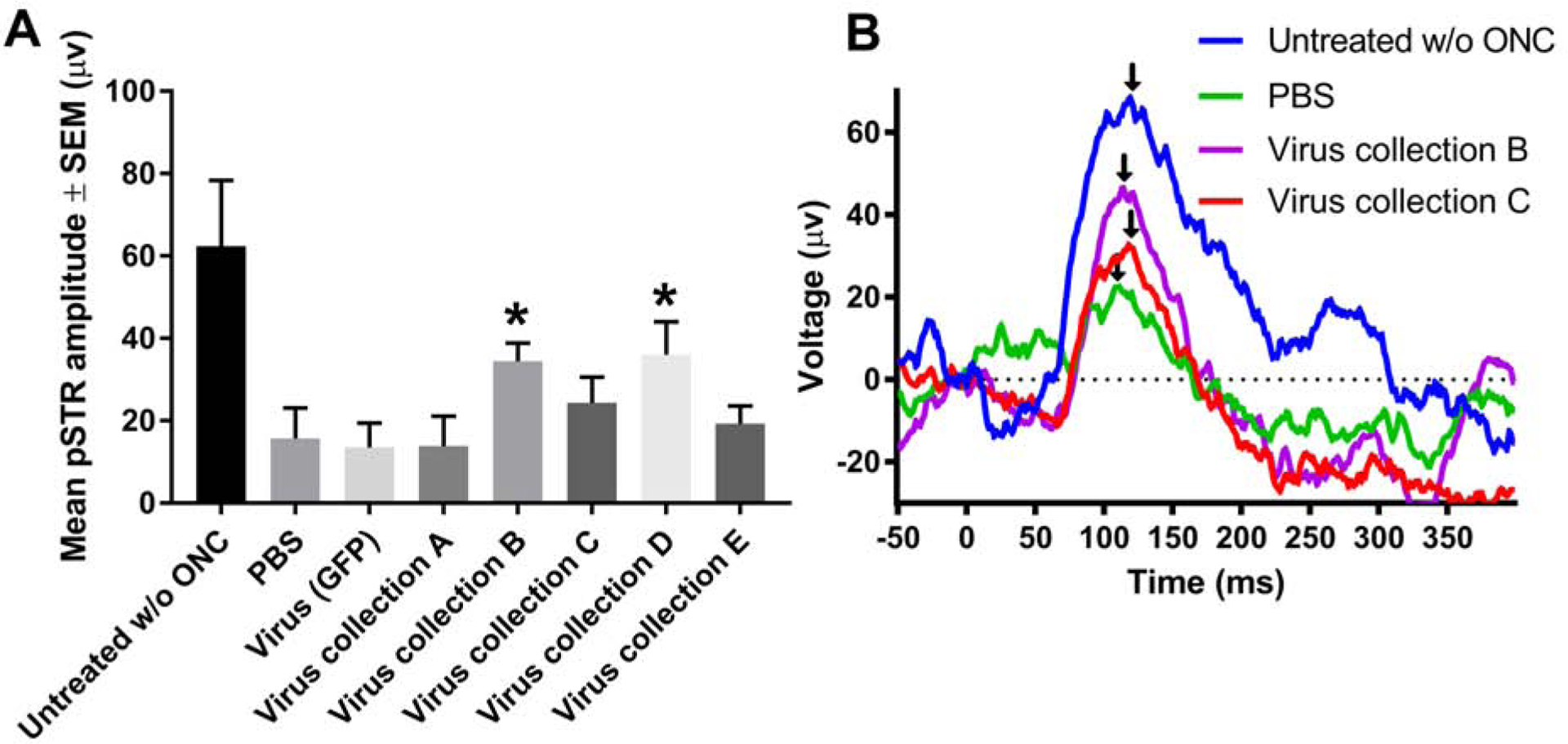

3.5. Viral delivery of miRNA preserves RGC function

The amplitude of the pSTR was used as a measure of RGC function, which (Figure. 5), which deteriorates rapidly after ONC. Measurements were taken at 7 days before ONC and 20 days post-crush. In PBS and virus (GFP) treated control animals, pSTR amplitude decreased significantly (15.7 ± 7.4, 13.5 ± 5.9 μv, respectively) compared to untreated animals without ONC (62.4 ± 16.0 μv). While intravitreal delivery of virus collection A, C and E yielded no significant preservation of pSTR amplitude (13.9 ± 7.3, 24.4 ± 6.2, 19.3 ± 4.3 μv, respectively), virus collection B and D significantly preserved pSTR amplitude (34.5 ± 4.4, 36.0 ± 8.0 μv, respectively) compared to PBS and virus (GFP) treated controls.

Figure 5:

pSTR amplitude after ONC. Mean pSTR amplitude measured with ERG 21 days after ONC (A). Asterisks indicate significant differences (p<0.05) from PBS and virus (GFP) control treated animals. Representative traces from the 5 animals per group are shown (B). Black arrows indicate peak amplitude that was recorded as the pSTR.

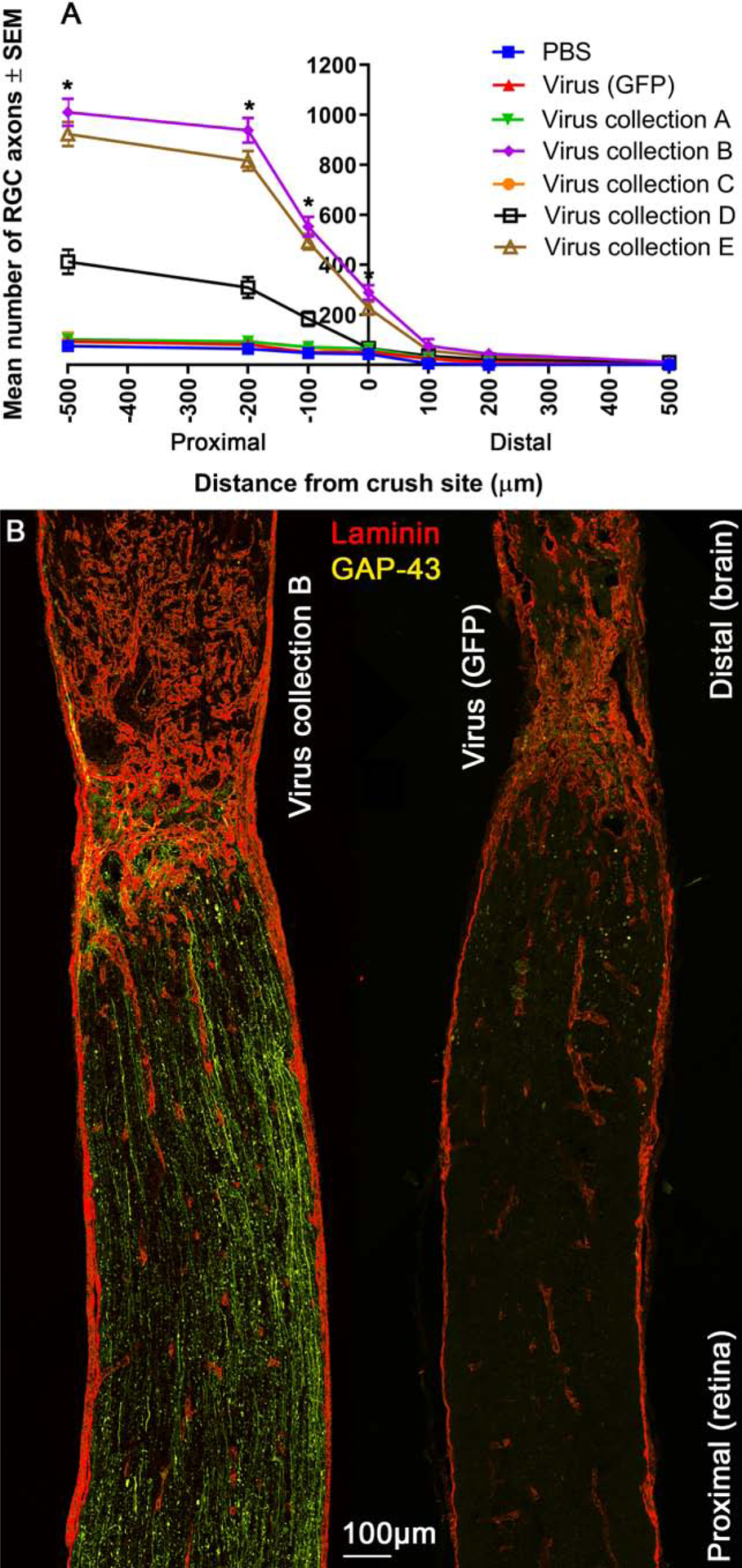

3.6. Viral delivery of miRNA promotes limited sprouting/protection of RGC axons, but not regeneration

Axons attempt, but ultimately fail to regenerate in animals after ONC, and this is amenable to candidate axogenic treatments. No significant long-distance axon regeneration beyond the crush site was observed in the experimental groups tested at day 21 (Figure. 6). Proximal to the crush site, virus collection B, D, and E treatment yielded more GAP-43+ axons at 500 μm (1010.2 ± 54.2, 413.0 ± 48.7, 923.2 ± 48.5 axons, respectively), 200 μm (938.0 ± 49.6, 309.5 ± 41.4, 816.0 ± 39.9 axons, respectively), and 100 μm (553.2 ± 39.7, 184.5 ± 28.4, 492.0 ± 31.2 axons, respectively) as well as at the crush site (290.0 ± 29.9, 66.9 ± 18.5, 227.0 ± 26.7 axons, respectively) in comparison to virus (GFP) treated controls (93.3 ± 15.9, 81.3 ± 11.8, 50.9 ± 10.5, 53.8 ± 11.4 axons, respectively). Distal to the laminin+ crush site, the number of axons was significantly higher only after virus collection B treatment and only at 100 μm from the crush site (76.1 ± 27.9 axons) compared to virus (GFP) treated controls (24.4 ± 8.1 axons).

Figure 6:

Protection against axonal degeneration in the optic nerve. Mean number of GAP-43+ axons at 100–500 μm distances proximal and distal to the laminin+ crush site (A). Asterisks indicate significant differences (p<0.05) from PBS and virus (GFP) control treated animals. Representative image (from 5 animals) of an optic nerve from animals treated with virus B or virus (GFP) control, immunohistochemically stained for laminin (red) and GAP-43 (yellow) are shown (B; scale bar 100μm).

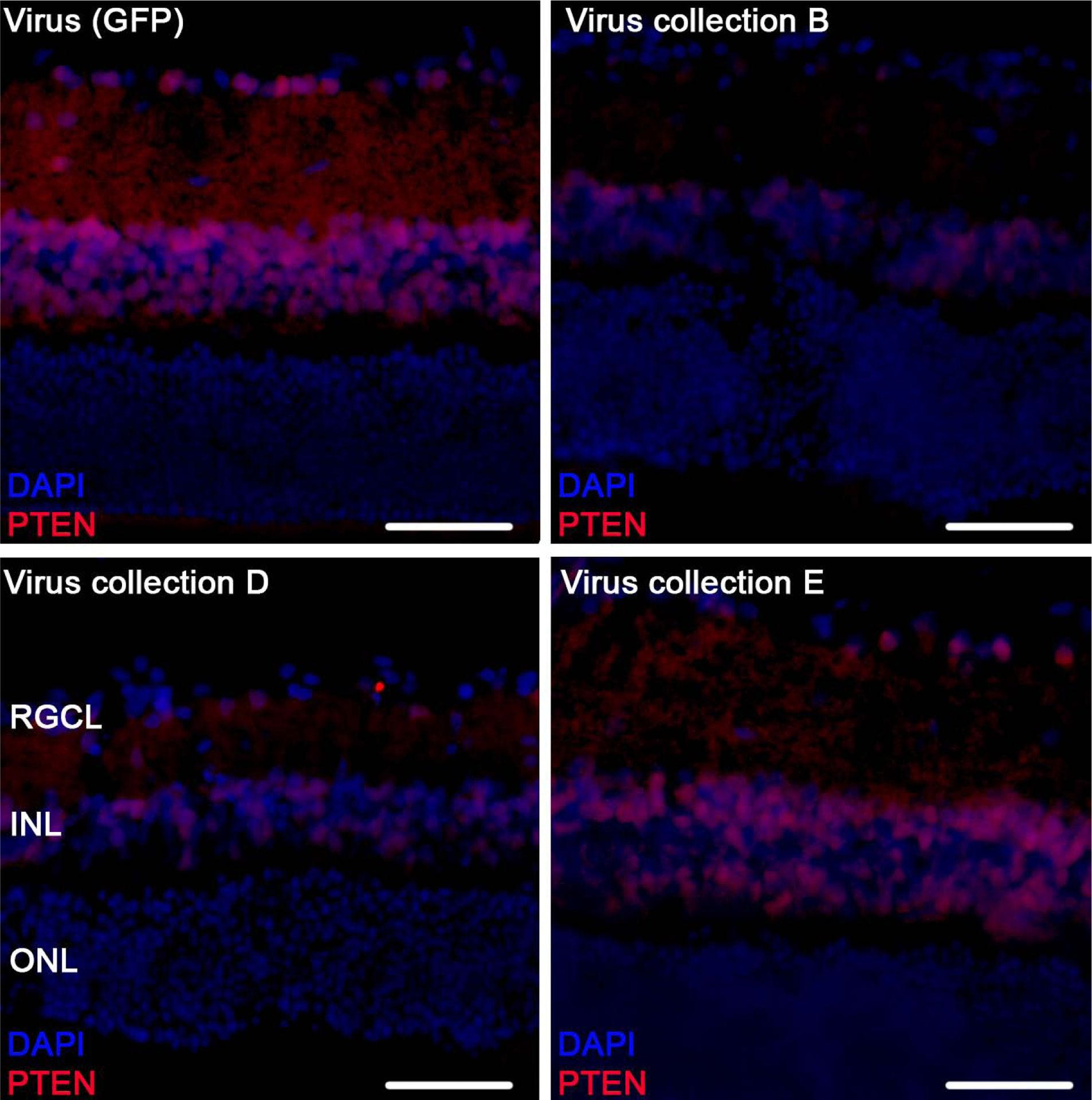

3.7. Viral delivery of selective miRNA promoted downregulation of PTEN

Many of the delivered miRNA target PTEN including miR-26a (Ding et al., 2017), miR-17–5p (Dhar et al., 2015; Li and Yang, 2012), and miR-92a (Ke et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2017; Serr et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2014), discussed further below. Immunohistochemical staining of retinal sections demonstrated that PTEN immunofluorescence was qualitatively reduced after treatment with virus collection B and D in comparison to virus (GFP) delivery (Figure. 7).

Figure 7:

Retinal PTEN expression after ONC. Representative images of parasagittal retinal sections stained for PTEN (red) and DAPI (blue), from 5 animals treated with virus (GFP) control, virus B, virus D and virus E. Retinal ganglion cell layer (RGCL), inner nuclear layer (INL), and outer nuclear layer (ONL) are labeled (scale bar 100μm).

3.8. Predicted targets of miRNA

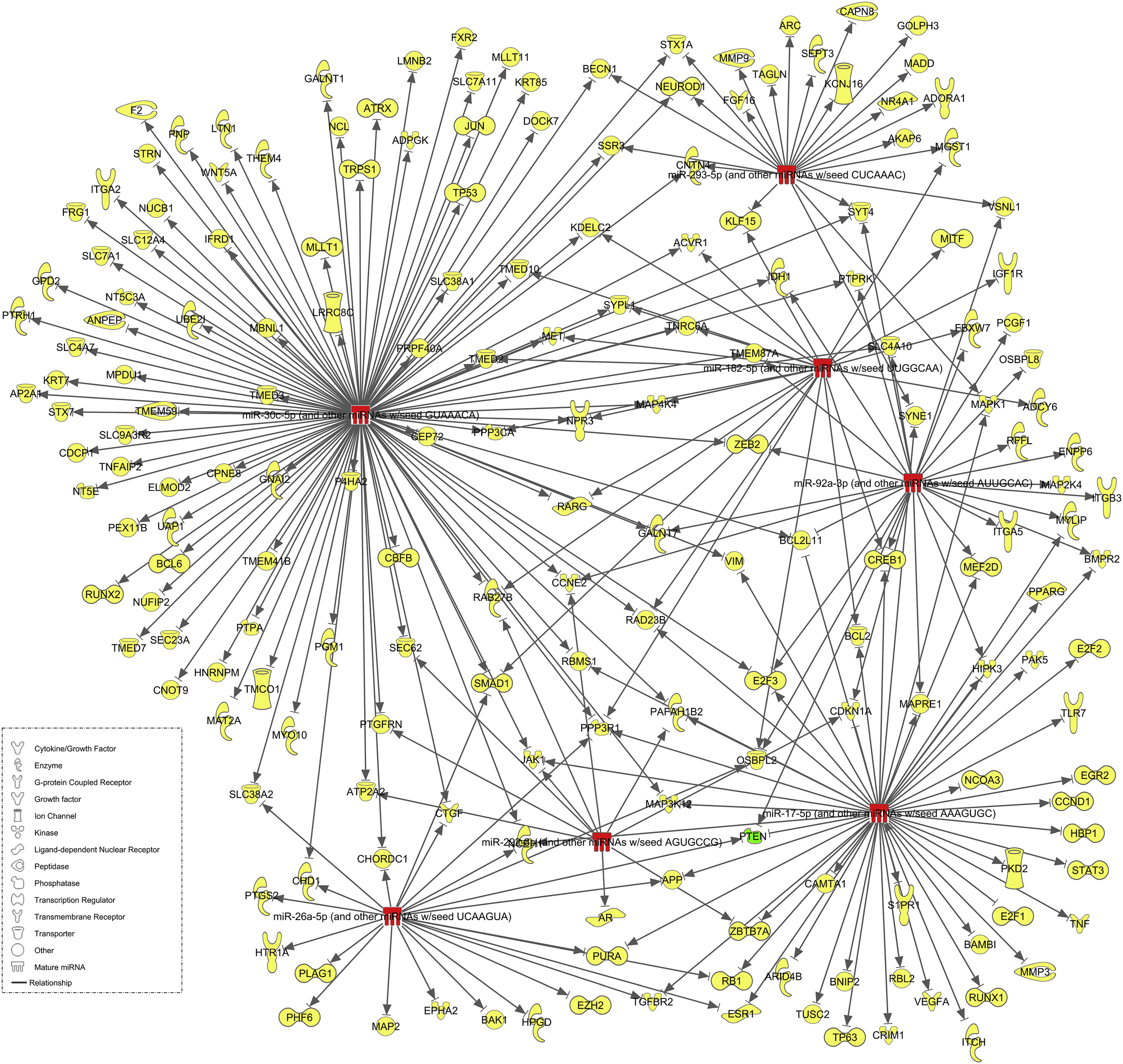

Utilizing Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, we analyzed the targets of the 6 miRNA we delivered. Since each miRNA is a stem loop that is broken into two mature miRNA, a 5p and 3p copy, mRNA targeting was performed for all 12 mature miRNA. In total we found 6818 predicted mRNA targets, 5815 targets that are present in both rat and human, 1551 of these which are highly predicted, and 189 of these which have been experimentally observed (Figure. 8). Many of these proteins are related to survival and regeneration and include Bcl proteins, STAT3, and PTEN. In particular, PTEN was an experimentally observed target to three of the miRNA: miR-26a-5p, miR-17–5p, and miR-92a-3p. Note that while all 12 of the miRNA have predicted targeting information, only 7 have experimentally observed targets.

Figure 8:

mRNA targets of delivered miRNA. Experimentally observed targets for virally delivered miRNA, obtained through Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software, are shown. Of the 6 miRNA stem loops and subsequent 12 mature miRNA sequences, 7 (red) have experimentally observed targets totaling at 189 mRNA (yellow) which includes the confirmed knocked down target mRNA PTEN (green).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to test neuroprotective and axogenic properties of six candidate miRNAs that have been previously identified as more abundant in BMSC-sEV than in fibroblast sEV (Mead et al., 2016; Mead and Tomarev, 2017).

Various combinations of these miRNAs were preferentially expressed in the RGCs of adult rats using an AAV2 viral vector. AAV serotypes have varying preference for cell types with AAV2 being the optimal serotype for delivery into RGCs. AAV2 transduces approximately 85% of RGCs after delivery into the vitreous body (Harvey et al., 2002; Martin et al., 2003). Comparable efficacy was also observed in our experiments with all viruses confirmed to transduce >80% of RGCs in vivo in the present study (Figure. 2). Previous studies using BAX knockout mice suggest that transduction is still possible in RGCs injured by ONC (Nickells et al., 2017), we decided to transduce 1 week prior to the ONC as it has been shown that AAV2-GFP takes 1 week before optimal in vivo expression is seen in RGCs (Smith and Chauhan, 2018). The relatively short amount of time between injection of AAV and in vivo expression is a consequence of our use of self-complementary AAV, which do not require host cell second strand synthesis, a significant rate-limiting step(McCarty, 2008). Intravitreal delivery of AAV2 shows no detrimental effects on RGCs, as measured by ERG (pSTR and nSTR) as well as OCT (RNFL) (Smith and Chauhan, 2018). While we could not confirm the over expression of every miRNA, likely due to the high endogenous expression already present in retinal tissue, AAV-mir-92a-1 led to a trend towards mir-92a-1 over expression and significant overexpression of mir-17. It is important to highlight that Q-PCR was done on total retina whereas AAV preferentially transduced RGC and is thus a likely reason for our inability to demonstrate significant differences in miRNA. We were still able to detect some differences however as well as PTEN reductions, demonstrating that AAV-miRNA was exerting a biological effect.

The ability of miRNA to downregulate a multitude of different mRNA(Gebert and MacRae, 2018) makes them a strong candidate as non-synthetic neuroprotective treatments for RGCs. They can be easily delivered into the vitreous to provide an immediate and direct effect on RGCs, although this avenue of research, utilizing miRNA as a treatment in the eye, is still poorly studied in the literature(Klingeborn et al., 2017). Delivery of miR-93–5p to RGCs in culture provides neuroprotection from NMDA-induced death and this miRNA was chosen based on its NMDA-induced downregulation (Li et al., 2018). Another miRNA downregulated in glaucoma is miR-200a, based on RT-qPCR of retinal samples from wildtype and microbead-induced glaucomatous mice (Peng et al., 2018). Intravenous injection of miR-200a mimics into a microbead mouse model of glaucoma provides significant neuroprotection of RGCs as well as preservation of RNFL thickness, likely through the knockdown of FGF7. A recent experiment utilized 12-week DBA/2J mice that received an injection of glutamate to induce RGC excitotoxicity. Intravitreal delivery of a virus expressing miR-141–3p led to a significant increase in RGC survival along with downregulation of apoptotic signalling pathways such as Bax and caspase-3 (Zhang et al., 2018).

A widely published target of many miRNA is PTEN (Bermúdez Brito et al., 2015), in large part due to PTEN being a tumor suppressor protein implicated in a number of cancers (Chalhoub and Baker, 2009). In the field of neuroregeneration and neuroprotection, PTEN knockdown significantly promotes both (Berry et al., 2016; Park et al., 2008) via activation of the mTOR/PI3K pathway. The treatment of RGCs in culture with the above mentioned miR-93–5p promoted neuroprotection through its targeting of PTEN (Li et al., 2018).

Many of the candidate miRNAs used in the present experiment target PTEN including miR-26a, demonstrated in gastric cancer cells (Ding et al., 2017), miR-17–5p, demonstrated in glioblastoma cells (Li and Yang, 2012) and prostate cancer cells (Dhar et al., 2015), and miR-92a, demonstrated in a variety of paradigms (Ke et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2017; Serr et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2014). Delivery of virus collection B (miR-17–5p, miR-30c-2 and miR-92a) and virus collection D (miR-92a, miR-292 and miR-182) promoted significant neuroprotection, preservation of RNFL thickness as measured by OCT, and preservation of RGC function, as measured by ERG. These effects coincided with a qualitative reduction in PTEN immunofluorescence within the retina, in contrast to virus (GFP) controls where PTEN was expressed in the GCL and inner nuclear layer. In virus collection B treated animals, the most substantial neuroprotection of RGCs was seen alongside minor axonal sprouting. Given that significant more axons were seen in this treatment group proximal to the lesion site in comparison to virus (GFP) treated control, it is likely the effect is not on regeneration but on preventing axonal degeneration. Nevertheless, the enhanced effect of virus collection B over D can be explained by the presence of miR-17–5p and miR-30c-2 in virus collection B but not virus collection D, which may target SOCS6 (Wu et al., 2014) and BCL9 (Jia et al., 2011), amongst many other predicted targets. Interestingly these miRNA were expressed in virus collection A yet showed no therapeutic effect, demonstrating that their combination with miR-92a is required to elicit the positive effects seen. Virus collection A also contained miR-26a which targets GSK3β, a kinase whose downregulation is expected to lead to CNS axon regeneration (Guo et al., 2016) yet this was not observed in the present study. Virus collection E contained all 6 miRNAs yet did not give the most pronounced effects with significance only seen for RNFL thickness and RGC survival. It can be suggested that because virus collection E was a combination of 2 virus batches each expressing 3 miRNAs, a competitive effect was observed leading to sub-threshold levels of each miRNA being delivered. This hypothesis is demonstrated by the lack of PTEN downregulation in virus collection E treated animals.

While the in vitro experiment demonstrated a trend towards neuroprotection/neuritogenesis, no significant effects were seen. This could be explained by the shorter duration afforded for successful transduction in vitro and the subsequently reduced transduction efficiency (50.1 ± 4.1%) on RGCs that we observed (Figure. 1). We also noticed a trending neuritogenic effect by AAV-GFP control in comparison to PBS control, suggesting the virus itself was having a confounding effect on the results and promoting neuritogenesis irrespective of the miRNA. This observation was not seen in vivo.

In conclusion we have demonstrated that virally delivered miRNA can significantly protect RGCs and their axons from degeneration and dysfunction. The mechanism of action is likely multifaceted, with several miRNA playing a role. PTEN, a confirmed target of many of the delivered miRNA was qualitatively reduced and coincided with the therapeutic effects observed. Further study is required to determine exactly which miRNA (and through which mRNA targets) exert greatest therapeutic efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Fold expression of miRNA. Fold change in the expression of Hsa-mir-17, Hsa-mir-30c-2 and Hsa-mir-92a-1 in four groups of retina injected with either PBS or AAV expressing Hsa-mir-17, Hsa-mir-30c-2 and Hsa-mir-92a-1. Data normalization was performed using the amount of total small RNAs used for each Q-PCR sample.

Damage to the optic nerve leads to permanent loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGC)

Neuroprotective strategies are required to prevent loss of RGC and function

The ability of miRNA to down-regulate mRNA makes them a candidate treatment

Here we deliver multiple miRNA to retinae of animals prior to optic nerve crush

Combinations of miRNA are able to prevent RGC loss and preserve their function

5. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Eye Institute. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 749346.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

6. References

- Bera A, Das F, Ghosh-Choudhury N, Mariappan MM, Kasinath BS, Ghosh Choudhury G, 2017. Reciprocal regulation of miR-214 and PTEN by high glucose regulates renal glomerular mesangial and proximal tubular epithelial cell hypertrophy and matrix expansion. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology 313, C430–C447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez Brito M, Goulielmaki E, Papakonstanti EA, 2015. Focus on PTEN Regulation. Frontiers in oncology 5, 166–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M, Ahmed Z, Morgan-Warren P, Fulton D, Logan A, 2016. Prospects for mTOR-mediated functional repair after central nervous system trauma. Neurobiol Dis 85, 99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M, Carlile J, Hunter A, 1996. Peripheral nerve explants grafted into the vitreous body of the eye promote the regeneration of retinal ganglion cell axons severed in the optic nerve. J Neurocytol 25, 147–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalhoub N, Baker SJ, 2009. PTEN and the PI3-kinase pathway in cancer. Annual review of pathology 4, 127–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching RC, Wiberg M, Kingham PJ, 2018. Schwann cell-like differentiated adipose stem cells promote neurite outgrowth via secreted exosomes and RNA transfer. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar S, Kumar A, Rimando AM, Zhang X, Levenson AS, 2015. Resveratrol and pterostilbene epigenetically restore PTEN expression by targeting oncomiRs of the miR-17 family in prostate cancer. Oncotarget 6, 27214–27226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding K, Wu Z, Wang N, Wang X, Wang Y, Qian P, Meng G, Tan S, 2017. MiR-26a performs converse roles in proliferation and metastasis of different gastric cancer cells via regulating of PTEN expression. Pathology - Research and Practice 213, 467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A, 2007. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods 39, 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flachsbarth K, Jankowiak W, Kruszewski K, Helbing S, Bartsch S, Bartsch U, 2018. Pronounced synergistic neuroprotective effect of GDNF and CNTF on axotomized retinal ganglion cells in the adult mouse. Experimental Eye Research 176, 258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebert LFR, MacRae IJ, 2018. Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Snider WD, Chen B, 2016. GSK3β regulates AKT-induced central nervous system axon regeneration via an eIF2Bε-dependent, mTORC1-independent pathway. eLife 5, e11903–e11903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AR, Kamphuis W, Eggers R, Symons NA, Blits B, Niclou S, Boer GJ, Verhaagen J, 2002. Intravitreal Injection of Adeno-associated Viral Vectors Results in the Transduction of Different Types of Retinal Neurons in Neonatal and Adult Rats: A Comparison with Lentiviral Vectors. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 21, 141–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoye ML, Regan MR, Jensen LA, Lake AM, Reddy LV, Vidensky S, Richard J-P, Maragakis NJ, Rothstein JD, Dougherty JD, Miller TM, 2018. Motor neuron-derived microRNAs cause astrocyte dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 141, 2561–2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia W, Eneh JO, Ratnaparkhe S, Altman MK, Murph MM, 2011. MicroRNA-30c-2* Expressed in Ovarian Cancer Cells Suppresses Growth Factor–Induced Cellular Proliferation and Downregulates the Oncogene BCL9. Molecular Cancer Research 9, 1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TV, Bull ND, Hunt DP, Marina N, Tomarev SI, Martin KR, 2010. Neuroprotective Effects of Intravitreal Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Experimental Glaucoma. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 51, 2051–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juźwik CA, Drake S, Lécuyer M-A, Johnson RM, Morquette B, Zhang Y, Charabati M, Sagan SM, Bar-Or A, Prat A, Fournier AE, 2018. Neuronal microRNA regulation in Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Scientific Reports 8, 13437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke T-W, Wei P-L, Yeh K-T, Chen WT-L, Cheng Y-W, 2015. MiR-92a Promotes Cell Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer Through PTEN-Mediated PI3K/AKT Pathway. Annals of Surgical Oncology 22, 2649–2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingeborn M, Dismuke WM, Rickman CB, Stamer WD, 2017. Roles of Exosomes in the Normal and Diseased Eye. Progress in retinal and eye research 59, 158–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kole C, Klipfel L, Yang Y, Ferracane V, Blond F, Reichman S, Millet-Puel G, Clérin E, Aït-Ali N, Pagan D, Camara H, Delyfer M-N, Nandrot EF, Sahel J-A, Goureau O, Léveillard T, 2018. Otx2-Genetically Modified Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Rescue Photoreceptors after Transplantation. Mol Ther 26, 219–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Yang BB, 2012. Stress response of glioblastoma cells mediated by miR-17–5p targeting PTEN and the passenger strand miR-17–3p targeting MDM2. Oncotarget 3, 1653–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Jin Y, Li Q, Sun X, Zhu H, Cui H, 2018. MiR-93–5p targeting PTEN regulates the NMDA-induced autophagy of retinal ganglion cells via AKT/mTOR pathway in glaucoma. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 100, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, Marsden CG, Thomson JM, Song J-J, Hammond SM, Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ, 2004. Argonaute2 Is the Catalytic Engine of Mammalian RNAi. Science 305, 1437–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan A, Ahmed Z, Baird A, Gonzalez AM, Berry M, 2006. Neurotrophic factor synergy is required for neuronal survival and disinhibited axon regeneration after CNS injury. Brain 129, 490–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CJ, Shan ZX, Hong J, Yang LX, 2017. MicroRNA-92a promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition through activation of PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in non-small cell lung cancer metastasis. Int J Oncol 51, 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KRG, Quigley HA, Zack DJ, Levkovitch-Verbin H, Kielczewski J, Valenta D, Baumrind L, Pease ME, Klein RL, Hauswirth WW, 2003. Gene Therapy with Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor As a Protection: Retinal Ganglion Cells in a Rat Glaucoma Model. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 44, 4357–4365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty DM, 2008. Self-complementary AAV Vectors; Advances and Applications. Mol Ther 16, 1648–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead B, Amaral J, Tomarev S, 2018. Mesenchymal Stem Cell–Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Promote Neuroprotection in Rodent Models of Glaucoma. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 59, 702–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead B, Hill LJ, Blanch RJ, Ward K, Logan A, Berry M, Leadbeater W, Scheven BA, 2016. Mesenchymal stromal cell-mediated neuroprotection and functional preservation of retinal ganglion cells in a rodent model of glaucoma. Cytotherapy 18, 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead B, Logan A, Berry M, Leadbeater W, Scheven BA, 2013. Intravitreally transplanted dental pulp stem cells promote neuroprotection and axon regeneration of retinal ganglion cells after optic nerve injury. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54, 7544–7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead B, Thompson A, Scheven BA, Logan A, Berry M, Leadbeater W, 2014. Comparative evaluation of methods for estimating retinal ganglion cell loss in retinal sections and wholemounts. Plos One 9, e110612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead B, Tomarev S, 2016. Evaluating retinal ganglion cell loss and dysfunction. Exp Eye Res 151, 96–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead B, Tomarev S, 2017. BMSC-derived exosomes promote survival of retinal ganglion cells through miRNA-dependent mechanisms. Stem cells translational medicine 6, 1273–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickells RW, Schmitt HM, Maes ME, Schlamp CL, 2017. AAV2-Mediated Transduction of the Mouse Retina After Optic Nerve Injury. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 58, 6091–6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie X-G, Fan D-S, Huang Y-X, He Y-Y, Dong B-L, Gao F, 2018. Downregulation of microRNA-149 in retinal ganglion cells suppresses apoptosis through activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in mouse with glaucoma. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne A, Khatib TZ, Songra L, Barber AC, Hall K, Kong GYX, Widdowson PS, Martin KR, 2018. Neuroprotection of retinal ganglion cells by a novel gene therapy construct that achieves sustained enhancement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor/tropomyosin-related kinase receptor-B signaling. Cell Death & Disease 9, 1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KK, Liu K, Hu Y, Smith PD, Wang C, Cai B, Xu B, Connolly L, Kramvis I, Sahin M, He Z, 2008. Promoting Axon Regeneration in the Adult CNS by Modulation of the PTEN/mTOR Pathway. Science 322, 963–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Sun Y-B, Hao J-L, Lu C-W, Bi M-C, Song E, 2018. Neuroprotective effects of overexpressed microRNA-200a on activation of glaucoma-related retinal glial cells and apoptosis of ganglion cells via downregulating FGF7-mediated MAPK signaling pathway. Cellular Signalling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajgor D, 2018. Macro roles for microRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases. Non-coding RNA Research 3, 154–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Navarro M, Mayor-Torroglosa S, Jimenez-Lopez M, Aviles-Trigueros M, Holmes TM, Lund RD, Villegas-Perez MP, Vidal-Sanz M, 2009. A computerized analysis of the entire retinal ganglion cell population and its spatial distribution in adult rats. Vision Res 49, 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed D, He M, Hong C, Gao S, Rane S, Yang Z, Abdellatif M, 2010. MicroRNA-21 Is a Downstream Effector of AKT That Mediates Its Antiapoptotic Effects via Suppression of Fas Ligand. The Journal of biological chemistry 285, 20281–20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serr I, Fürst RW, Ott VB, Scherm MG, Nikolaev A, Gökmen F, Kälin S, Zillmer S, Bunk M, Weigmann B, Kunschke N, Loretz B, Lehr C-M, Kirchner B, Haase B, Pfaffl M, Waisman A, Willis RA, Ziegler A-G, Daniel C, 2016. miRNA92a targets KLF2 and the phosphatase PTEN signaling to promote human T follicular helper precursors in T1D islet autoimmunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, E6659–E6668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Chauhan BC, 2018. In vivo imaging of adeno-associated viral vector labelled retinal ganglion cells. Scientific Reports 8, 1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suggate EL, Ahmed Z, Read ML, Eaton-Charnock K, Douglas MR, Gonzalez AM, Berry M, Logan A, 2009. Optimisation of siRNA-mediated RhoA silencing in neuronal cultures. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 40, 451–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang X, Ren X-P, Chen J, Liu H, Yang J, Medvedovic M, Hu Z, Fan G-C, 2010. MicroRNA-494 Targeting both Pro-apoptotic and Anti-apoptotic Proteins Protects against Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced Cardiac Injury. Circulation 122, 1308–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Luo G, Yang Z, Zhu F, An Y, Shi Y, Fan D, 2014. miR-17–5p promotes proliferation by targeting SOCS6 in gastric cancer cells. FEBS Letters 588, 2055–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia XW, Li Y, Wang WB, Tang F, Tan J, Sun LY, Li QH, Sun L, Tang B, He SQ, 2015. MicroRNA-1908 functions as a glioblastoma oncogene by suppressing PTEN tumor suppressor pathway. Mol Cancer 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Yu WF, Hu KZ, Li MQ, Chen JW, Li ZC, 2017. miR-92a promotes tumor growth of osteosarcoma by targeting PTEN/AKT signaling pathway. Oncol Rep 37, 2513–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Zhou H, Xiao H, Liu Z, Tian H, Zhou T, 2014. MicroRNA-92a Functions as an Oncogene in Colorectal Cancer by Targeting PTEN. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 59, 98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L-Q, Cui H, Yu Y-B, Shi H-Q, Zhou Y, Liu M-J, 2018. MicroRNA-141–3p inhibits retinal neovascularization and retinal ganglion cell apoptosis in glaucoma mice through the inactivation of Docking protein 5-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Journal of cellular physiology 0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chopp M, Liu XS, Katakowski M, Wang X, Tian X, Wu D, Zhang ZG, 2016. Exosomes Derived from Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Promote Axonal Growth of Cortical Neurons. Mol Neurobiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Fold expression of miRNA. Fold change in the expression of Hsa-mir-17, Hsa-mir-30c-2 and Hsa-mir-92a-1 in four groups of retina injected with either PBS or AAV expressing Hsa-mir-17, Hsa-mir-30c-2 and Hsa-mir-92a-1. Data normalization was performed using the amount of total small RNAs used for each Q-PCR sample.