Abstract

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake among US adolescents is primarily dependent on the intent of their parents. An analysis quantifying parental intent to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series in the US at both the national and state level has so far been missing. Our aims were to determine national and state-level estimates of parental intent to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series and to identify reasons for lack of intent to series initiation and completion.

Methods

This cross-sectional study utilizes data from the 2017–2018 National Immunization Survey-Teen of US adolescents aged 13–17 years. Study participants were parents/caregivers, who were most knowledgeable about the adolescents’ immunization status. Outcomes were measured as parental intent to vaccinate the adolescent in the next 12 months and reasons for lack of intent to initiate and complete the series. We computed national and state-level estimates for parental lack of intent to initiate and to complete the vaccine series. Population-level estimates were derived using survey weights. A survey design-adjusted Wald F test was used for bivariate analysis. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to examine the association between provider recommendation and parental intent. Analyses were stratified by history of provider recommendation to initiate the HPV vaccine series.

Findings

In 2017–2018, 37·1% (equating to 7·7 million of 20·8 million) US adolescents were unvaccinated and 10·8% (2·2 million of 20·8 million) received only one HPV vaccine dose (i.e., initiators). Parents of 58·0% (4·3 million of 7·3 million) unvaccinated adolescents had no intention to initiate the HPV vaccine series with safety issues being the most frequently cited (22·8%) concern. Over 65% parents of unvaccinated adolescents in Idaho, Kansas, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Utah had no intention to initiate the HPV vaccine series. Parents of 23·5% (0·5 million of 2·2 million) initiators had no intention to complete the HPV vaccine series; the majority (22·2%) of these parents cited lack of provider recommendation as the main reason for no intent. Lack of intent to complete the HPV vaccine series was relatively higher (over 30%) in Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Utah, and West Virginia. In comparison, in the District of Columbia (11·2%) and Rhode Island (20·4%) parental lack of intent was relatively low. Receipt of a provider recommendation was associated with higher odds of parental intent to initiate the HPV vaccine series (odds ratio 1·11 [95% CI 1·01–1·22]). About 45·5% (3·3 million of 7·3 million) of parents of unvaccinated adolescents had reportedly received an HPV vaccine recommendation. Parents of 60·6% (2·0 million of 3.3 million) unvaccinated adolescents had no intention to initiate the series despite a provider recommendation.

Interpretation

Lack of parental intent to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series for adolescents is a major public health concern in the US. Combating vaccine safety concerns and strong recommendations from healthcare providers could improve the currently suboptimal HPV vaccination coverage.

Funding

US National Cancer Institute

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 34 800 human papillomavirus (HPV) associated cancers (i.e., cervical, oropharyngeal, anal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar cancers) were diagnosed annually in the United States (US) during 2012–2016.1 In the era of universal decline in cancer incidence, the collective burden of HPV-associated cancers continues to rise in the US, mainly attributable to a marked increase (nearly 3% annually) in oropharyngeal and anal cancer incidence rates in recent years.1,2 The HPV vaccine is an effective intervention for the prevention of anogenital HPV infections and associated cancers.3,4 Although currently not licensed for oropharyngeal cancer prevention (due to lack of efficacy data from randomized clinical trials), observational studies suggest that the vaccine may also protect against oral HPV infection.5,6

The US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends a 2-dose HPV vaccine regimen for girls and boys initiating the series before their 15th birthday and a 3-dose regimen thereafter.7 Timely initiation and completion of the series is critical to optimize immune response to the HPV vaccine.8 However, only half of the US adolescents had completed the vaccine series and nearly 32% were unvaccinated in 2018.9 The variation in HPV vaccine series completion across all states was also substantial (with highest completion rates in Rhode Island [78%] and lowest in Mississippi [28%]).10

Initiation and completion of the HPV vaccination series by adolescents is largely dependent on the intent of their parents. Theoretical models have identified intention as the most important construct for behavioral change, making parental vaccination behavior a primary focus for vaccine-promoting interventions.11,12 Parental attitudes towards the HPV vaccine might be driven by vaccine naivety in unvaccinated adolescents.13 In comparison, having experienced their adolescents receive the first HPV vaccine dose, factors driving parents’ decision to complete (or not to complete) the series may be different. Herein, we present national and state-level estimates of parents’ intention to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series in adolescents using the 2017–2018 National Immunization Survey (NIS)-Teen data. We also identified reasons for parental lack of intent for series initiation and completion.

METHODS

Data Source

We analyzed the 2017–2018 NIS-Teen, an annual random-digit-dial (RDD) survey of adolescents aged 13 to 17 years living in the US. Procedure for 2017–2018 data consolidation is described in Appendix 1. Each year, households with adolescents are identified. An adult respondent (i.e., parent/caregiver) most knowledgeable about the teen’s vaccination history is interviewed by phone after obtaining informed consent. Subsequently, an extensive review of the data is performed for completeness, and sampling weights are calculated after adjustment for sub-sampling and non-response to achieve an accurate representation of the adolescent population. A subset of participants in the NIS-Teen (approximately 51%) consented to contact their health care providers, and immunization history for these participants was subsequently verified by mailing requests for medical records. For the purpose of this study, we utilized the entire sample of adolescents with data on parental intent and reasons. The subset with provider-verifiable data was utilized to examine the robustness of estimates. Details regarding the sampling methodology, data processing, and estimation of the survey weights are available in Appendix 1 and on the NIS-Teen website.14

Sociodemographic characteristics

The NIS-Teen survey collects data regarding age, sex of the adolescent, race/ethnicity, and their relationship with parent/caregiver. Data regarding the poverty status of the adolescents, insurance status, and state of residence are also reported.

HPV immunization questionnaire

All respondents (i.e., parents/caregivers) were asked whether they recalled the adolescent receiving the HPV vaccine (“Has teen ever received any human papillomavirus shots?”). Those who responded “yes” were asked to report the total number of HPV vaccine doses received. Respondents who reported “no” were assigned zero for the total number of doses received. We categorized adolescents as ‘unvaccinated’ (teens who received zero HPV vaccine doses) and ‘initiators’ (teens who received only one HPV vaccine dose).

Parental intent to vaccinate was based on the question, “How likely it is that teen will receive HPV shots in the next 12 months?” with response options “Very Likely”, “Somewhat likely”, “Not too likely”, “Not likely at all”, and “Not sure/Don’t know”. This question was asked to all parents regardless of whether the adolescent had received the HPV vaccine. Parents who responded “Not too likely” or “Not likely at all” were categorized as having a lack of intention to vaccinate their adolescents. During the survey, parents were also asked, “What is the MAIN reason teen will not receive ANY HPV shots in the next 12 months?” (if zero doses of the HPV vaccine were received); otherwise, “What is the MAIN reason teen will not receive ALL HPV shots in the next 12 months?” (if >0 doses were received). Parents selected the main reason from a list of predefined reasons; if unlisted, the response was elicited in an open-ended manner. In the final dataset, all reasons were recoded into 28 unique yes/no questions by the NIS-Teen staff.

Statistical Analysis

We identified unvaccinated adolescents and adolescents who received only the first HPV vaccine series dose (i.e., initiators) from the 2017–2018 NIS-Teen survey data. Descriptive statistics were used to examine the sociodemographic characteristics of unvaccinated and vaccine-initiating adolescents; the Wald F test and t test were utilized to examine differences in categorical and continuous variables, respectively. National and state-level estimates for parental lack of intent to initiate and to complete the vaccine series were computed using survey-weighted frequency procedures. A survey design-adjusted Wald F test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used for bivariate analysis that compared the proportion of parents of unvaccinated and vaccine-initiating adolescents selecting a given reason as the ‘main’ reason for their lack of intent. Parental reasons for not initiating versus completing the HPV vaccine series were stratified by adolescents’ sex. The subset of adolescents with provider-verified information was utilized for sensitivity analysis.

Provider recommendation is an important mediator for the initiation and completion of the HPV vaccine series.15 Therefore, the analyses were stratified based on the history of provider recommendation to initiate the HPV vaccine. Subsequently, multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for sociodemographic variables were utilized to examine the association between a history of provider recommendation and parental intent, and for stratified analysis.

All analyses were adjusted for strata and weights using the SAS SURVEY procedures to account for the complex survey design. Statistical significance was tested at P<0·05. All analyses were conducted per the analytical guideline for the NIS-Teen data using the SAS® statistical software (version 9·4).16

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

In 2017–2018, of 82 297 eligible adolescents, a total of 30 558 adolescents were unvaccinated (i.e., received 0 doses), while 9073 adolescents had initiated (i.e., received only 1 dose) the HPV vaccine series according to their parents/caregivers. The characteristics of unvaccinated adolescents and those who received 1 dose are presented in Appendix 2. Nationally, 45·5% unvaccinated and 90·5% of those who received the first dose had reported receiving a recommendation to initiate the HPV vaccine series from a healthcare professional. Information on parental intent was available for 29 086 unvaccinated adolescents and 9072 initiators.

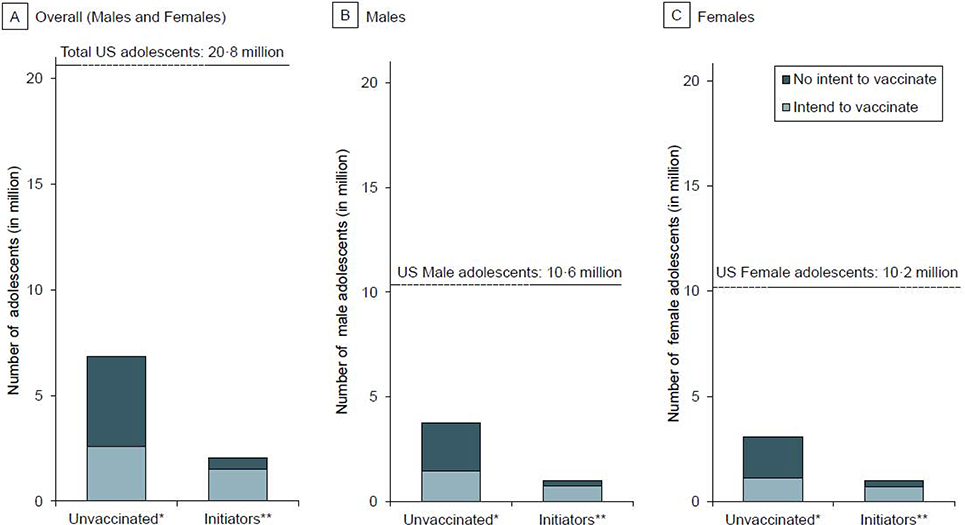

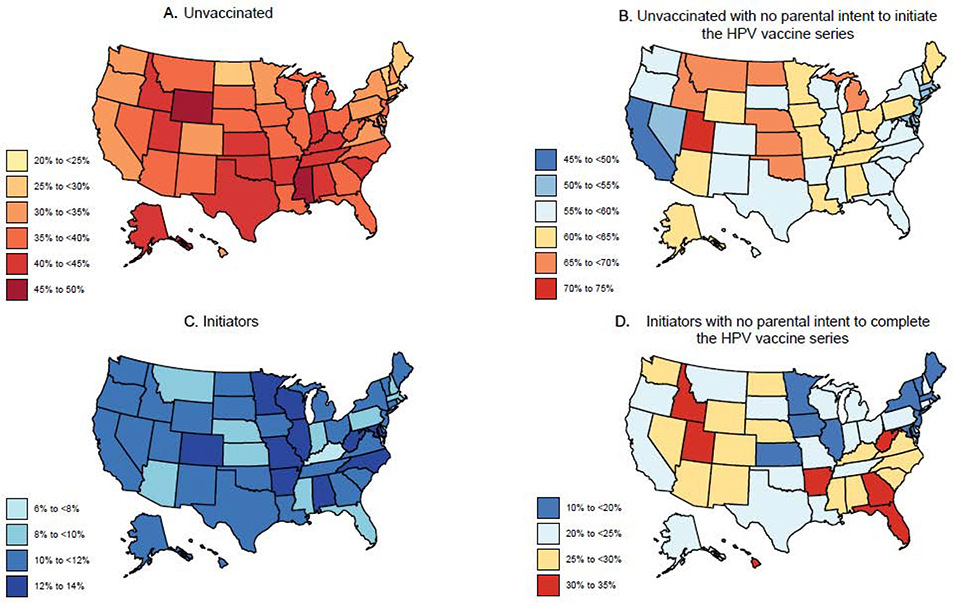

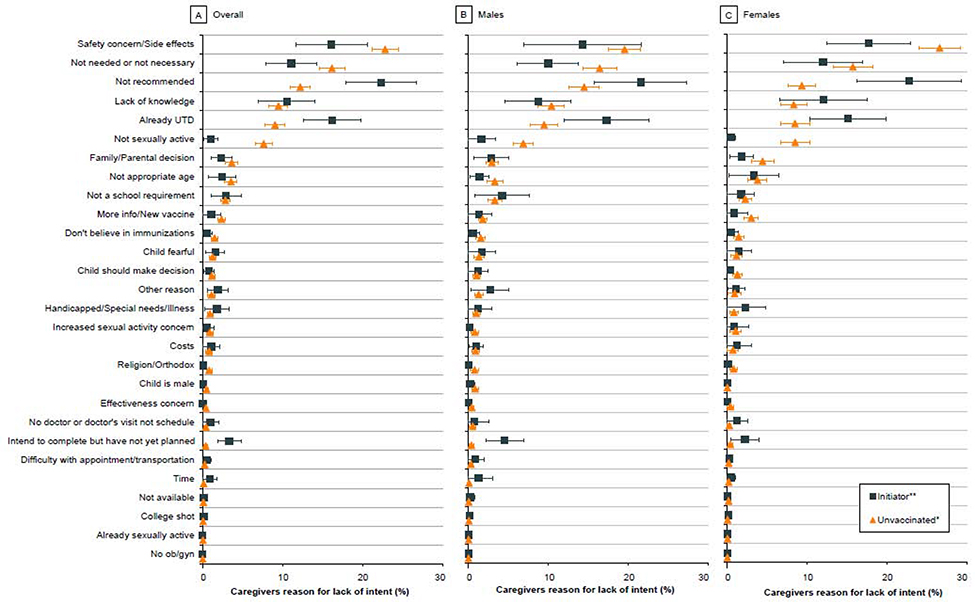

Unvaccinated adolescents constituted 37·1% (equating to 7·7 million) of the US adolescent population aged 13–17 years (20·8 million). Overall, more than half (58·0% [4·3 million of 7·3 million]) of the parents of unvaccinated adolescents did not intend to initiate the HPV vaccine series (Figure 1A). The proportions of unvaccinated boys and girls with parental lack of intent were 57·0% [2·3 million of 4·1 million] and 59·4% [1.9 million of 3·3 million], respectively (Figure 1B and 1C). In the state-specific analysis, parental lack of intent was nearly 50% or over in District of Columbia (DC) and across all states with or without mandates (i.e., a legislative order to receive the HPV vaccine for school entry). Notably, lack of intent in Idaho (69·9% [33 835 of 48 402]) and Utah (72·6% [75 477 of 103 988]) was higher compared to other states (Table 1 and Figure 2). Over 65% of parents of unvaccinated adolescents in Kansas, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Oklahoma had no intention to initiate the HPV vaccine series. In Wyoming and Missisippi (states with lowest vaccination coverage in the nation), 61.9% and 57.1% of parents of unvaccinated adolescents, respectively, did not intend to initiate the series. The top five reasons for parental lack of intent to initiate the HPV vaccine series were—’safety concerns’ (22·8%), ‘not needed/not necessary’ (16·1%), ‘not recommended’ (12·2%), ‘lack of knowledge’ (9·5%), and ‘already up-to-date’ (9·0%) (Figure 3A). Notably, ‘safety concerns,’ ‘not needed/not necessary,’ and ‘not recommended’ accounted for over 50% of all the responses. ‘Safety concern’ was the top reason for lack of intent to initiate the series for both male (19·6%) (Figure 3B) and female (26·6%) adolescents (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 1. Number of US adolescents (overall, males, and females) by HPV vaccination status and parental intent to vaccinate, NIS-Teen 2017–2018.

The figure illustrates the total number of US adolescents aged 13–17 years by HPV vaccination status and parental intent to vaccinate. In 2017–2018 NIS-Teen, 37·1% (7·7 million of 20·8 million) US adolescents were unvaccinated and 10·8% (2·2 million of 20·8 million) received only one HPV vaccine dose (i.e., initiators). Parents of 58·0% (4·3 million of 7·3 million) unvaccinated adolescents did not intend to initiate the vaccine series (Panel A). These constitute of 2·3 million unvaccinated male adolescents (Panel B) and 1·9 million unvaccinated female adolescents (Panel C) whose parents do not intend to initiate the HPV vaccine series. Parents of 23·5% (0·5 million of 2·2 million) US adolescents who received only one HPV vaccine dose had no intention to complete the vaccine series (Panel A); these constitute of nearly 0·2 million adolescent males (Panel B) and 0·3 million adolescent females (Panel C) in the US with no parental intent to complete the series.

Abbreviations: US, United States; HPV, human papillomavirus; NIS, National Immunization Survey

*0 dose

**1 dose only

Table 1:

Parental lack of intent to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series by state in the US, NIS-Teen 2017–2018

| States | Unvaccinated (0 dose) | Initiators (1 dose only) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total unvaccinated* | Unvaccinated with no parental intent to initiate series** | Total initiators† | Initiators with no parental intent to complete series†† | |||||

| n/N | % (95% CI) | n/N | % (95% CI) | n/N | % (95% CI) | n/N | % (95% CI) | |

| Alabama | 130 445/ 312 188 | 41·8 (38·8 to 44·8) | 75 274/ 120 301 | 62·6 (58·0 to 67·2) | 37 466/ 312 188 | 12·0 (10·0 to 14·0) | 11 022/ 37 466 | 29·4 (21·4 to 37·5) |

| Alaska | 20 476/ 48 159 | 42·5 (39·5 to 45·6) | 11 489/ 18 793 | 61·1 (56·3 to 66·0) | 4964/ 48 159 | 10·3 (8·5 to 12·1) | 1161/ 4964 | 23·4 (15·5 to 31·3) |

| Arizona | 181 742/ 465 298 | 39·1 (36·0 to 42·1) | 103 170/ 169 734 | 60·8 (55·8 to 65·7) | 44 529/ 465 298 | 9·6 (7·8 to 11·4) | 11 868/ 44 529 | 26·7 (18·0 to 35·3) |

| Arkansas | 85 803/ 198 438 | 43·2 (40·1 to 46·4) | 48 747/ 81 880 | 59·5 (54·7 to 64·4) | 27 282/ 198 438 | 13·7 (11·5 to 16·0) | 8665/ 27 282 | 31·8 (23·2 to 40·3) |

| California | 842 928/ 2 530 832 | 33·3 (30·2 to 36·5) | 403 726/ 809 415 | 49·9 (44·0 to 55·7) | 272 571/ 2 530 832 | 10·8 (8·7 to 12·8) | 62 582/ 272 571 | 23·0 (14·9 to 31·0) |

| Colorado | 119 671/ 358 660 | 33·4 (30·2 to 36·6) | 63 519/ 112 753 | 56·3 (50·4 to 62·3) | 45 203/ 358 660 | 12·6 (10·3 to 14·9) | 12 165/ 45 203 | 26·9 (18·1 to 35·7) |

| Connecticut | 76 872/ 228 863 | 33·6 (30·6 to 36·6) | 38 559/ 73 706 | 52·3 (46·7 to 57·9) | 26 600/ 228 863 | 11·6 (9·6 to 13·7) | 5595/ 26 600 | 21·0 (13·1 to 29·0) |

| Delaware | 17 550/ 57 868 | 30·3 (27·3 to 33·3) | 9638/ 16 232 | 59·4 (53·3 to 65·4) | 5983/ 57 868 | 10·3 (8·4 to 12·3) | 1227/ 5983 | 20·5 (12·9 to 28·1) |

| DC+++ | 5653/ 25 338 | 22·3 (19·4 to 25·3) | 2469/ 4909 | 50·3 (42·4 to 58·3) | 2843/ 25 338 | 11·2 (9·0 to 13·5) | 319/ 2843 | 11·2 (5·4 to 17·1) |

| Florida | 444 891/ 1 187 483 | 37·5 (34·5 to 40·4) | 238 300/ 424 734 | 56·1 (51·0 to 61·2) | 104 222/ 1 187 483 | 8·8 (7·1 to 10·5) | 34 478/ 104 222 | 33·1 (23·4 to 42·7) |

| Georgia | 281 261/ 721 074 | 39·0 (36·0 to 42·1) | 150 132/ 264 837 | 56·7 (51·7 to 61·7) | 75 100/ 721 074 | 10·4 (8·5 to 12·3) | 24 749/ 75 100 | 33·0 (23·5 to 42·5) |

| Hawaii | 26 201/ 79 013 | 33·2 (30·2 to 36·1) | 14 334/ 24 005 | 59·7 (54·2 to 65·2) | 8060/ 79 013 | 10·2 (8·4 to 12·0) | 2606/ 8060 | 32·3 (23·6 to 41·1) |

| Idaho | 51 625/ 126 133 | 40·9 (37·7 to 44·2) | 33 835/ 48 402 | 69·9 (65·0 to 74·8) | 14 342/ 126 133 | 11·4 (9·2 to 13·6) | 4829/ 14 342 | 33·7 (23·7 to 43·7) |

| Illinois | 318 903/ 833 612 | 38·3 (36·1 to 40·4) | 175 720/ 300 102 | 58·6 (54·9 to 62·2) | 103 266/ 833 612 | 12·4 (11·0 to 13·8) | 18 745/ 103 266 | 18·2 (13·6 to 22·7) |

| Indiana | 189 760/ 449 114 | 42·3 (39·1 to 45·4) | 116 154/ 180 074 | 64·5 (59·8 to 69·2) | 42 138/ 449 114 | 9·4 (7·5 to 11·2) | 8570/ 42 138 | 20·3 (12·4 to 28·3) |

| Iowa | 73 889/ 203 209 | 36·4 (33·1 to 39·6) | 42 723/ 70 562 | 60·5 (55·0 to 66·1) | 23 033/ 203 209 | 11·3 (9·1 to 13·6) | 4559/ 23 033 | 19·8 (12·1 to 27·5) |

| Kansas | 88 048/ 198 146 | 44·4 (41·1 to 47·7) | 56 968/ 85 905 | 66·3(61·6 to 71·0) | 19 075/ 198 146 | 9·6 (7·6 to 11·7) | 3223/ 19 075 | 16·9 (9·2 to 24·6) |

| Kentucky | 118 937/ 283 853 | 41·9 (38·7 to 45·1) | 67 620/ 112 709 | 60·0 (55·0 to 65·0) | 22 431/ 283 853 | 7·9 (6·2 to 9·6) | 5897/ 22 431 | 26·3 (16·3 to 36·2) |

| Louisiana | 111 258/ 303 252 | 36·7 (33·6 to 39·8) | 63 003/ 105 026 | 60·0 (55·0 to 65·0) | 344 35/ 303 252 | 11·4 (9·3 to 13·5) | 8437/ 34 435 | 24·5 (16·2 to 32·8) |

| Maine | 21 371/ 74 585 | 28·7 (25·8 to 31·5) | 12 599/ 20 338 | 61·9 (56·1 to 67·8) | 8852/ 74 585 | 11·9 (9·8 to 13·9) | 1642/ 8852 | 18·6 (11·8 to 25·3) |

| Maryland | 120 865/ 380 108 | 31·8 (28·6 to 35·0) | 66 126/ 11 6043 | 57·0 (50·8 to 63·2) | 48 004/ 380 108 | 12·6 (10·4 to 14·9) | 8416/ 48 004 | 17·5 (10·0 to 25·1) |

| Massachusetts | 111 433/ 404 253 | 27·6 (24·6 to 30·5) | 53 117/ 105 652 | 50·3 (43·8 to 56·7) | 40 036/ 404 253 | 9·9 (8·1 to 11·7) | 4772/ 40 036 | 11·9 (5·8 to 18·0) |

| Michigan | 230 629/ 640 624 | 36·0 (33·0 to 39·0) | 146 778/ 221 560 | 66·2 (61·2 to 71·3) | 70 979/ 640 624 | 11·1 (9·0 to 13·1) | 14 802/ 70 979 | 20·9 (12·8 to 28·9) |

| Minnesota | 120 616/ 362 205 | 33·3 (30·0 to 36·6) | 70 476/ 113 724 | 62·0 (56·1 to 67·9) | 46 432/ 362 205 | 12·8 (10·6 to 15·1) | 8400/ 46 432 | 18·1 (10·9 to 25·3) |

| Mississippi | 97 122/ 202 835 | 47·9 (44·7 to 51·1) | 51 119/ 89 549 | 57·1 (52·5 to 61·7) | 19 319/ 202 835 | 9·5 (7·6 to 11·4) | 5417/ 19 319 | 28·0 (18·9 to 37·2) |

| Missouri | 149 056/ 391 150 | 38·1 (35·1 to 41·2) | 87 185/ 141 188 | 61·8 (56·7 to 66·8) | 51 973/ 391 150 | 13·3 (11·1 to 15·4) | 10 973/ 51 973 | 21·1 (13·8 to 28·4) |

| Montana | 24 924/ 62 969 | 39·6 (36·2 to 42·9) | 15 879/ 23 341 | 68·0 (62·8 to 73·3) | 5721/ 62 969 | 9·1 (7·1 to 11·0) | 1188/ 5721 | 20·8 (12·1 to 29·5) |

| Nebraska | 48 299/ 131 112 | 36·8 (33·6 to 40·1) | 29 926/ 45 760 | 65·4 (59·8 to 7·0) | 12 782/ 131 112 | 9·7 (7·9 to 11·6) | 3271/ 12 782 | 25·6 (16·8 to 34·3) |

| Nevada | 72 550/ 191 859 | 37·8 (35·0 to 40·6) | 36 331/ 66 145 | 54·9 (50·1 to 59·8) | 21 300/ 191 859 | 11·1 (9·3 to 12·9) | 5529/ 21 300 | 26·0 (18·8 to 33·1) |

| New Hampshire | 25 478/ 78 928 | 32·3 (29·2 to 35·4) | 15 427/ 24 810 | 62·2 (56·5 to 67·9) | 7175/ 78 928 | 9·1 (7·2 to 11·0) | 1627/ 7175 | 22·7 (13·3 to 32·0) |

| New Jersey | 225 339/ 572 770 | 39·3 (36·5 to 42·1) | 111 274/ 213 928 | 52·0 (47·4 to 56·6) | 63 625/ 572 770 | 11·1 (9·3 to 13·0) | 9631/ 63 625 | 15·1 (9·5 to 20·8) |

| New Mexico | 51 514/ 137 077 | 37·6 (34·4 to 40·7) | 28 265/ 48 519 | 58.3 (52·9 to 63·6) | 14 305/ 137 077 | 10·4 (8·4 to 12·5) | 4203/ 14 305 | 29·4 (19·3 to 39·5) |

| New York | 394 656/ 116 1100 | 34·0 (31·8 to 36·2) | 215 903/ 373 994 | 57·7 (53·7 to 61·7) | 119 229/ 1 161 100 | 10·3 (8·9 to 11·6) | 21 570/ 119 229 | 18·1 (12·2 to 24·0) |

| North Carolina | 237 911/ 661 275 | 36·0 (33·0 to 39·0) | 131 368/ 226 684 | 58·0 (52·9 to 63·0) | 80 294/ 661 275 | 12·1 (10·0 to 14·2) | 20 889/ 80 294 | 26·0 (17·5 to 34·5) |

| North Dakota | 13 036/ 43 927 | 29·7 (26·7 to 32·6) | 8151/ 12 363 | 65·9 (60·2 to 71·7) | 4845/ 43 927 | 11·0 (8·9 to 13·1) | 1241/ 4845 | 25·6 (16·7 to 34·5) |

| Ohio | 296 063/ 750 640 | 39·4 (36·5 to 42·4) | 176 868/ 280 093 | 63·1 (58·5 to 67·8) | 85 456/ 750 640 | 11·4 (9·4 to 13·4) | 20 896/ 85 456 | 24·5 (16·3 to 32·6) |

| Oklahoma | 116 684/ 264 705 | 44·1 (41·1 to 47·0) | 71 793/ 109 853 | 65·4 (60·9 to 69·8) | 28 814/ 264 705 | 10·9 (9·0 to 12·7) | 7186/ 28 814 | 24·9 (17·1 to 32·8) |

| Oregon | 84 505/ 243 710 | 34·7 (31·6 to 37·8) | 46 060/ 81 295 | 56·7 (51·0 to 62·3) | 25 255/ 243 710 | 10·4 (8·4 to 12·3) | 5846/ 25 255 | 23·1 (14·4 to 31·9) |

| Pennsylvania | 262 586/ 769 845 | 34·1 (31·4 to 36·9) | 158 981/ 253 640 | 62·7 (57·9 to 67·5) | 72 623/ 769 845 | 9·4 (7·8 to 11·0) | 16 110/ 72 623 | 22·2 (14·1 to 30·3) |

| Rhode Island+++ | 13 579/ 60 307 | 22·5 (19·7 to 25·4) | 6645/ 12 290 | 54·1 (46·5 to 61·7) | 5191/ 60 307 | 8·6 (76·8 to 10·4) | 1061/ 5191 | 20·4 (11·6 to 29·3) |

| South Carolina | 131 361/ 310 476 | 42·3 (39·2 to 45·4) | 71 254/ 125 342 | 56·8 (52·0 to 61·7) | 34 101/ 310 476 | 11·0 (9.1 to 12·9) | 10 018/ 34 101 | 29·4 (20·8 to 37·9) |

| South Dakota | 20 465/ 56 744 | 36·1 (32·9 to 39·2) | 11 302/19 238 | 58·7 (53·0 to 64·5) | 6128/ 56 744 | 10·8 (8·9 to 12·7) | 1457/ 6128 | 23·8 (15·2 to 32·3) |

| Tennessee | 178 205/ 425 537 | 41·9 (38·6 to 45·2) | 105 846/ 169 414 | 62·5 (57·4 to 67·6) | 45 957/ 425 537 | 10·8 (8·8 to 12·8) | 10 174/ 45 957 | 22·1 (13·3 to 30·9) |

| Texas | 854 553/ 2 046 196 | 41·8 (40·1 to 43·4) | 443 104/ 805 224 | 55·0 (52·4 to 57·7) | 211 651/ 2 164 196 | 10·3 (9·4 to 11·3) | 49 387/ 211 651 | 23·3 (19·4 to 27·3) |

| Utah | 107 908/ 254 060 | 42·5 (39·2 to 45·7) | 75 477/ 103 988 | 72·6 (68·1 to 77·1) | 27 586/ 254 060 | 10·9 (8·8 to 12·9) | 8891/ 27 586 | 32·2 (23·2 to 41·3) |

| Vermont | 8847/ 35 063 | 25·2 (22·3 to 28·2) | 4659/ 8349 | 55·8 (49·0 to 62·6) | 3815/ 35 063 | 10·9 (8·7 to 13·1) | 513/ 3815 | 13·5 (5·7 to 21·2) |

| Virginia+++ | 177 858/ 525 439 | 33·8 (29·9 to 37·8) | 99 832/ 171 464 | 58·2 (51·0 to 65·5) | 58 666/ 525 439 | 11·2 (8·4 to 14·0) | 14 905/ 58 666 | 25·4 (14·3 to 36·5) |

| Washington | 143 067/ 450 493 | 31·8 (28·6 to 34·9) | 78 095/ 134 017 | 58·3 (52·2 to 64·4) | 49 897/ 450 493 | 11·1 (8·9 to 13·2) | 12 554/ 49 897 | 25·2 (15·4 to 34·9) |

| West Virginia | 41 417/ 106 186 | 39·0 (36·0 to 42·0) | 22 967/ 39 652 | 57·9 (52·9 to 62·9) | 13 164/ 106 186 | 12·4 (10·3 to 14·5) | 4263/ 13 098 | 32·5 (24·1 to 41·0) |

| Wisconsin | 132 507/ 371 040 | 35·7 (32·7 to 38·7) | 73 132/ 127 251 | 57·7 (52·1 to 62·8) | 47 455/ 371 040 | 12·8 (10·7 to 14·9) | 9953/ 47 455 | 21·0 (13·8 to 28·1) |

| Wyoming | 17 620/ 36 714 | 48·0 (44·7 to 51·3) | 10 609/ 17 143 | 61·9 (57·3 to 66·5) | 4239/ 36 714 | 11·5 (9·4 to 13·7) | 1073/ 4239 | 25·3 (17·3 to 33·3) |

Acronym: DC, District of Columbia

States with HPV vaccine mandate (i.e., a legislative order to receive the human papillomavirus [HPV] vaccine for school entry)

Percentage of unvaccinated adolescents = (number [n] of unvaccinated US adolescents aged 13–17 years ÷ number [N] of US adolescents aged 13–17 years) × 100· Population estimates of US adolescents in 2017–2018 were derived using National Immunization Survey (NIS)-Teen survey weights·

Percentage of unvaccinated adolescents with no parental intent = (number [n] of unvaccinated US adolescents aged 13–17 years with no parental intent ÷ number [N] of unvaccinated US adolescents aged 13–17 years with non-missing data on parental intent) × 100· Data on parental intent was missing for approximately 5% unvaccinated adolescents· Population estimates of US adolescents in 2017–2018 were derived using National Immunization Survey (NIS)-Teen survey weights·

Percentage of initiators = (number [n] of US adolescents aged 13–17 years who received 1 HPV vaccine dose only ÷ number [N] of US adolescents aged 13–17 years) × 100· Population estimates of US adolescents in 2017–2018 were derived using National Immunization Survey (NIS)-Teen survey weights·

Percentage of initiators with no parental intent = (number [n] of US adolescents aged 13–17 years who received 1 HPV vaccine dose only with no parental intent ÷ number [N] of US adolescents aged 13–17 years who received 1 HPV vaccine dose only with non-missing data on parental intent) × 100· Population estimates of US adolescents in 2017–2018 were derived using National Immunization Survey (NIS)-Teen survey weights.

FIGURE 2. Parental lack of intent to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series by states in the US, NIS-Teen 2017–2018.

The figure illustrates the proportion of unvaccinated and those who received only one HPV vaccine dose (i.e., initiators), and the proportion of parents with a lack of intent to vaccinate across US. Panel A illustrates the proportion of unvaccinated adolescents. Panel B illustrates parental lack of intent to initiate the HPV vaccine series. Panel C illustrates the proportion of adolescents who one dose only. Panel C illustrates parental lack of intent to complete the HPV vaccine series.

Abbreviations: US, United States; HPV, human papillomavirus; NIS, National Immunization Survey

FIGURE 3. Parental reasons for lack of intent to vaccinate by HPV vaccination status of the adolescent, NIS-Teen 2017–2018.

The figure illustrates the 28 reasons for lack of intent included in the NIS-Teen survey and the proportion of parents who responded ‘Yes’ for each listed reason. Parents were asked to identify the ‘main’ reason; therefore, responses are mutually exclusive. Panel A illustrates the main reasons for the overall adolescent population. The top reason for parental lack of intent to initiate the HPV vaccine in unvaccinated (i.e., received 0 HPV vaccine dose) adolescents was ‘safety concern’. The top reason for parental lack of intent to complete the series among initiators (i.e., received 1 HPV vaccine dose only) was ‘lack of a provider recommendation’. Panels B and C illustrate parental reasons for lack of intent to initiate versus to complete the series in male and female adolescents, respectively. Analyses were restricted to adolescents with information on parental reasons for no intent to vaccinate.

Abbreviations: US, United States; HPV, human papillomavirus; NIS, National Immunization Survey.

*0 dose

**1 dose only

Initiators (i.e., those who received 1 dose) constituted 10·8% (equating to 2·2 million) of the adolescent population aged 13–17 years (20·8 million) during 2017–2018. Parents of 23·5% [0·5 million of 2·2 million] of these adolescents did not intend to complete the series (Figure 1A). The proportions of boys and girls with parental lack of intent were 22·9% [0·2 million of 1·1 million] and 24·1% [0·3 million of 1·1 million], respectively (Figure 1B and 1C). In the state-specific analysis, parental lack of intent to complete the HPV vaccine series was relatively high for initiators in Idaho (33·7% [4829 of 14 342] (Table 1 and Figure 2) compared to other states. Lack of intent to complete the HPV vaccine series was over 30% in Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Utah, and West Virginia. In DC (11·2% [319 of 2843]) and Rhode Island (20·4% [1061 of 5191]), where HPV vaccine is mandated, lack of intent to series completion was relatively low. ‘Not recommended’ (22·2%) was the most common reason for the lack of intent to complete the vaccine series (Figure 3A). ‘Safety concerns’ (16·1%), ‘already up-to-date’ (16·1%), ‘not needed/not necessary (11·1%), and ‘lack of knowledge’ (10·5%) were also among the top five reasons for the lack of intent to complete the vaccine series. In both males (21·6%) and females (22·8%) (Figures 3B and 3C), ‘not recommended’ was cited by most parents as the main reason for lack of intent to complete the HPV vaccine series.

‘Safety concerns’ (P<0·001) and ‘not needed/not necessary’ (P<0·001) were more frequently cited as main reasons by parents for their lack of intent to initiate the HPV vaccine versus that for completion of the vaccine series. In comparison, ‘not recommended’ (P<0·001) and ‘already up-to-date’ (P<0·001) were more frequently reported by parents as reasons for lack of intent to complete the vaccine series versus that for initiating the series (Appendix 3). Statistically significant differences between unvaccinated adolescents and initiators by sex are presented in Appendix 4 (males) and Appendix 5 (females). In sensitivity analysis restricted to provider-verifiable sample, the top five reasons for parental lack of intent among unvaccinated and initiators were the same as those in the main analysis (Appendix 6).

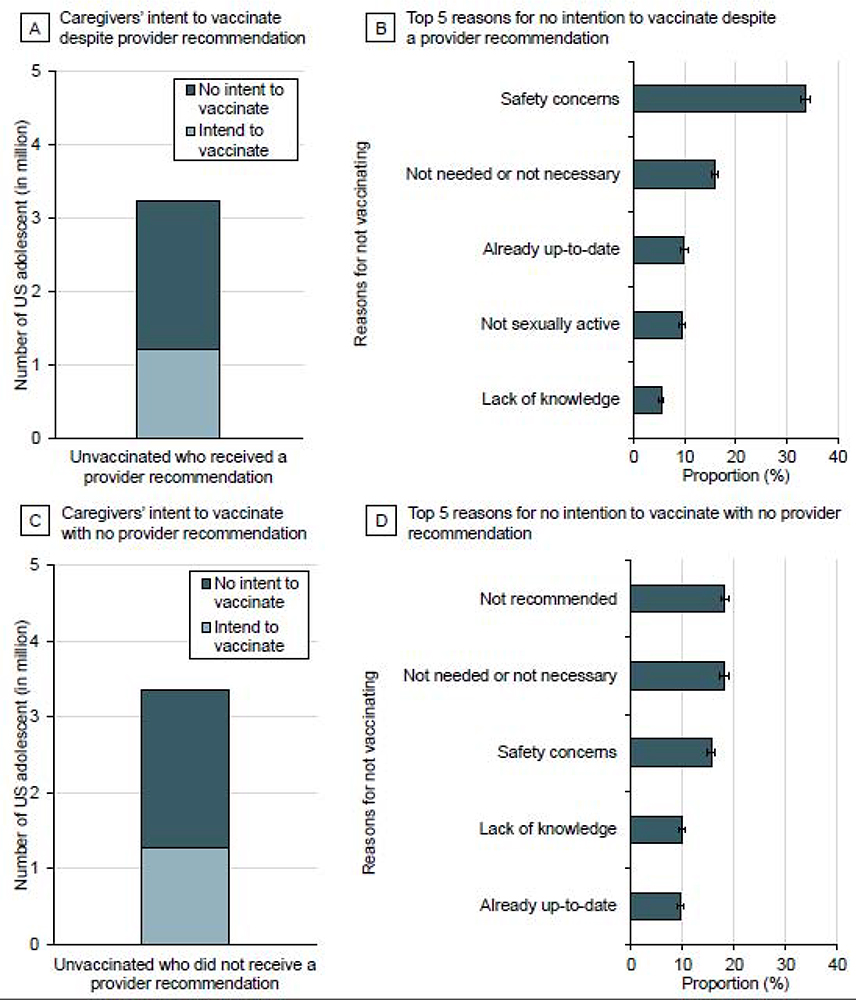

Results for the unvaccinated group were further stratified by provider recommendations. Despite a provider recommendation, 60·6% (2·0 million of 3·3 million) parents of unvaccinated adolescents had no intention to initiate the HPV vaccine series (Figure 4A) and the majority (33·7%) cited ‘safety concerns’ as their primary reason for lack of intent (Figure 4B). Similarly, 56·5% (2·1 million of 3·7 million) parents of unvaccinated adolescents who did not receive a provider recommendation had no intention for series initiation (Figure 4C); among these parents, ‘not recommended’ was the main reason (18·2%) for not completing the series (Figure 4D). In multivariate analysis, parents who had reportedly received a recommendation from a provider to initiate the HPV vaccine were more likely to intend to vaccinate their adolescent (odds ratio, OR=1·11 [95% CI, 1·01–1·22]) (Appendix 7).

FIGURE 4. Intent and top 5 reasons for lack of intent among parents of unvaccinated adolescents stratified by history of a provider recommendation to initiate the HPV vaccine series.

Panel A illustrates the number of US adolescents with no parental intent to vaccinate (2.0 million) despite a provider recommendation to initiate the HPV vaccine series (3·3 million); Panel B illustrates the top 5 reasons for no parental intent. Panel C illustrates the number of US adolescents with no parental intent to vaccinate (2·1 million) with no provider recommendation (3.7 million); Panel D illustrates the top 5 reasons for no parental intent.

Among those who reportedly had received a recommendation to initiate the HPV vaccine series from a provider, increasing age, female sex, non-Hispanic White race, and higher household income (>$75 000) were associated with lower odds of parental intent to vaccinate (Appendix 8). Similarly, among those who did not receive a provider recommendation to initiate the HPV vaccine series, increasing age, White race, and household income >$75 000 were associated with lower odds of parental intent. Having the survey respondent be a mother caregiver (versus father) was associated with lower odds of parental intent to vaccinate among those who received a provider recommendation, while father caregiver was associated with lower intent among those who did not receive a provider recommendation.

DISCUSSION

Our study, to our knowledge, is the first to comprehensively describe parental intent to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series as well as reasons for parental lack of intent in the US. Nationally, over one-half of parents of unvaccinated adolescents did not intend to initiate the HPV vaccine series. In addition, parents of nearly one-fourth of the adolescents who had received the first HPV vaccine dose had no intention to complete the series. These findings are troubling given that parental intent is an important determinant of HPV vaccine initiation and completion in adolescents.

In our state-specific analysis, we found that in Mississippi and Wyoming (states where HPV vaccine series completion rates are lowest in the nation: 28·8% and 30·9%, respectively),10 nearly 60% of the parents of unvaccinated adolescents had no intention to initiate the vaccine series. These findings have important public health implications. If the parental lack of intent continues to persist in these states, the triad of poor initiation rates, poor series completion rates, and a history of poor HPV vaccine coverage might compromise herd immunity. As a result, these states may face a disproportionately higher burden of HPV-associated cancers in future decades. Our state-specific findings also highlight the importance of HPV vaccination mandates. In DC and Rhode Island, where HPV vaccine is mandated, the proportions of unvaccinated adolescents were lowest in the nation, and parental lack of intent for series completion was also lower than the national average. These findings suggest that such mandates have been effective in overcoming HPV vaccine hesitancy and improving HPV vaccination coverage.

Safety concern was the main reason for parental lack of intent to initiate the HPV vaccine series. In several countries, including Japan, Ireland, Denmark, and Columbia, safety scare led to substantial declines in HPV vaccine uptake.17–20 A recent literature review of determinants of HPV vaccine hesitancy in Europe identified vaccine safety concerns as one of the most important reasons (48% in the UK and Italy, 69% in the Netherlands, 60% in Romania, and 54% in Greece) for parental lack of intent.21 Our findings suggest that HPV vaccination in the US also suffers from high parental refusal or deferral largely driven by safety scare. Social media (including YouTube videos, twitter, and blogs) has been recognized as a major source of unsubstantiated content related to vaccine safety in the US.22,23 In a recent survey of 1263 American parents, nearly one-third had heard stories about HPV vaccine harms from social media. Notably, these parents were more likely to refuse (OR=8·9 [95% CI, 4·1–19·3]) the HPV vaccine compared to the parents who had never heard of such stories.24 Additionally, a prior systematic literature review also identified safety concerns as a major barrier to HPV vaccination in the US.15 To counter misinformation and tackle safety scare in the US, national informational campaigns (similar to those launched in Ireland and Denmark) are urgently needed.18,25 Healthcare providers can also play a vital role in combatting misinformation by educating parents about HPV vaccine safety and benefits, thereby, reducing vaccine hesitancy among parents.

The main reason for not intending to complete the HPV vaccine series was a lack of provider recommendation for subsequent doses. This finding may be partly explained by knowledge gaps regarding the HPV vaccination dosing schedule among US physicians. A recent national survey of US pediatricians and family physicians showed that at least one-third of health care professionals had incorrect knowledge or reported not knowing about the number of doses recommended by ACIP.26 The use of reminder systems at the point of care may help mitigate this issue. However, in the same national survey, <50% of US physicians were reportedly using evidence-based methods (e.g., standing orders and alerts in the medical record), prompting the need for vaccination at the point of care.27 Our findings, along with these data, highlight the need for increased use of these reminder systems to improve HPV vaccine series completion.

Lack of knowledge and not needed/not necessary were other major reasons for parental lack of intent to initiate and complete the series. Knowledge gaps regarding HPV is prevalent among US adults: while 45% of men and women in a recent national study had never heard about HPV and the HPV vaccine, less than 25% of adults knew that HPV causes anal, penile, and head and neck cancers.28 The reasons parents do not recognize the need of HPV vaccine or believe it is not necessary is unclear. It is possibly a combined effect of individuals’ knowledge of HPV, attitude, personal beliefs, social influences, and lack of provider recommendation.29 A strong recommendation from a healthcare provider can substantiate the need for the HPV vaccine. In particular, high-quality recommendation (one that is strongly endorsed, has a cancer prevention message, and emphasizes urgency) can help improve HPV vaccine initiation and completion rates.30

Our findings regarding lack of knowledge and parental vaccine hesitancy are consistent with data from Europe. Insufficient knowledge has been reported as a major barrier to vaccination among parents in Romania (81% in 2015), Netherlands (67% in 2009–2011), and Denmark (70% in 2010).21 Similar to the US, lack of a provider recommendation is also an issue contributing towards parental vaccine hesitancy in Europe. Studies from Spain, Italy, France, and Denmark reported that nearly one-third of hesitant parents never received any HPV vaccine recommendation, while an average of 26% of hesitant parents in studies from Spain and Italy and 19% parents in a study from Germany reported having been advised against HPV vaccine by their health care providers.21 Collectively, these reasons, in addition to safety concerns, maybe contributing towards the growing sentiment of vaccine hesitancy that the World Health Organization has identified as one of the top ten threats to global health.31

An important finding that emerged from our stratified analysis was that despite having received a recommendation from a healthcare provider, a substantial proportion (over 60%) of parents had no intention to initiate the HPV vaccination in 2017–2018 with the majority reporting safety as their primary concern. This finding is troubling when compared to data from a 2010 NIS-Teen study; the proportion of parents with no intent despite provider recommendation in 2010 was 43%. The increasing number (nearly 40% rise from 2010 to 2018) of parents who are reluctant to vaccinate their adolescents despite provider recommendation reflects a strong and growing sentiment of hesitancy towards the HPV vaccine in the US. The same study showed that parental hesitancy towards other vaccines was relatively low—16·1% for Tetanus, Diphtheria, Pertussis Vaccine, 9·7% for Meningococcal conjugate vaccines—in 2010, indicating that HPV vaccine hesitancy is more acute compared to other adolescent vaccines.32

Our study has certain limitations. First, respondents in the NIS-Teen survey are parents/caregivers of adolescents. Although the survey protocol seeks to identify the parent who is most knowledgeable regarding the teenager’s immunization status, it is possible that few respondents did not comply with this protocol. Second, a small fraction of parents of adolescents with HPV vaccine contraindication may have cited ‘not recommended’ as a reason for not intending to vaccinate. Information regarding vaccine contraindication is unavailable in the NIS-Teen; therefore, estimates pertaining to ‘not recommended’ should be interpreted within the context of this caveat. Third, missing data in the NIS-Teen could be partly attributable to the items being collected and not entirely missing at random, which could lead to under or overestimation of some parameters. Next, survey responses are prone to social desirability and recall bias. However, at least two previous studies have reported high concordance between parent- and provider-reported HPV vaccine series initiation (84%−92%) in the NIS-Teen survey concluding that parents’ responses are reasonably accurate.33,34 Finally, the survey asks parents to report only the ‘main’ reason for their lack of intent; parents of some adolescents may have had more than one reason for lack of intent. Nevertheless, capturing the primary reason allowed us to identify the most heavily weighted concern by parents for their hesitancy towards the HPV vaccine. Despite these limitations, the principal strength of our study is that it is generalizable to the US adolescent population and provides the most comprehensive information on parental intent for HPV vaccination.

Our findings show that HPV vaccine hesitancy is prevalent in the US. Safety concerns and lack of provider recommendations are significant contributing factors for parental lack of intent to HPV vaccine series initiation and completion, respectively. Although initial success has been made in boosting HPV vaccination rates, coverage in 2018 did not improve among female adolescents aged 13–17 years (53·1% in 2017 and 53·7% in 2018) and adults aged 18–26 years (21·6% in 2017 and 21·5% in 2018).7,35 Our findings lead to a sobering conclusion that parental reluctance towards the HPV vaccine may be a major impediment to achieving optimal vaccination coverage in the US. If these trajectories continue, the Healthy People 2020 goal of achieving 80% HPV vaccination coverage among US adolescents will be far beyond reachable, particularly in states with low vaccination coverage and high parental hesitancy. Aggressive and coordinated efforts among healthcare providers, parents, media, policymakers, and state health agencies are urgently needed to combat HPV vaccine hesitancy.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

According to the 2019 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, nearly half of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine-eligible US adolescents are not up-to-date on vaccination. Given the lack of mandates (i.e., a legislative order to receive the HPV vaccine for school entry) in most states, HPV vaccination in US adolescents is mainly dependent on the intent of their parents. We searched PubMed for studies published from January 1, 2007 to March 15, 2020, with the search terms “Human papillomavirus vaccine OR “HPV vaccine,” AND “parental intent” OR “lack of intent,” AND “hesitancy,” AND “reasons for hesitancy.” We restricted the search to publications in English. Our search found no previous studies that have examined national and state-level estimates of parental intent to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series in the US. Prior US studies have described parental reasons for lack of intent for HPV vaccination. However, national estimates of reasons for lack of intent to initiation and completion are unavailable.

Added value of this study

Using data from a nationally representative survey of US adolescents (the National Immunization Survey-Teen), we determined national and state-level estimates of parental intent to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series and discerned reasons for parental lack of intent for series initiation and completion. Nationally, over one-half of the parents of unvaccinated adolescents had no intention to initiate the HPV vaccine series. In Idaho, Kansas, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Utah, over 65% of parents of unvaccinated adolescents had no intention to initiate the HPV vaccine series. Moreover, 61·9% parents of unvaccinated adolescents in Wyoming and 57·1% in Mississippi (states with some of the lowest HPV vaccine coverage in the nation) did not intend to initiate the series. Nationally, almost a quarter of the parents of adolescents who received the first dose of the vaccine had no intention to complete the series. In Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Utah, and West Virginia, over 30% of the parents had no intention to complete the HPV vaccine series. In the District of Columbia and Rhode Island, where HPV vaccination is mandated, lack of parental intent to complete the vaccine series was 11·2% and 20·4%, respectively. Most parents cited ‘safety concern’ as the main reason for not intending to initiate the series. In comparison, the majority of parents cited ‘lack of provider recommendation’ as the main reason for not intending to complete the HPV vaccine series.

Implications of all the available evidence

Given the lack of HPV vaccine mandate in most states, addressing reasons for parental lack of intent for HPV vaccine series initiation and completion is critical to the improvement of HPV vaccine coverage in the US.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from the US National Cancer Institute (R01CA232888). The funder had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US National Cancer Institute. We would like to thank the reviewers and the editor for their constructive comments. We also thank Yueh-Yun Lin and Haluk Damgacioglu for their statistical support.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: ARG support from Merck & CO, Inc, outside the submitted work for her role as a member of several advisory boards and speaker at conference symposia. AAD received consulting fee from Merck on unrelated projects.

Data sharing/availability: The NIS-Teen data, documentation, and codebook is available for download at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/nis/datasets-teen.html. Statistical code is available at request from Dr. Sonawane (Kalyani.B.Sonawane@uth.tmc.edu).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, Thomas CC, Markowitz LE, Benard VB. Trends in Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers - United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(33): 918–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deshmukh AA, Suk R, Shiels MS, et al. Recent trends in squamous cell carcinoma of the anus incidence and mortality in the United States, 2001–2015. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonawane K, Nyitray AG, Nemutlu GS, Swartz MD, Chhatwal J, Deshmukh AA. Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus Infection by Number of Vaccine Doses Among US Women. JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2(12): e1918571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villa A, Patton LL, Giuliano AR, et al. Summary of the evidence on the safety, efficacy, and effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccines: Umbrella review of systematic reviews. J Am Dent Assoc 2020; 151(4): 245–54 e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonawane K, Suk R, Chiao EY, et al. Oral Human Papillomavirus Infection: Differences in Prevalence Between Sexes and Concordance With Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection, NHANES 2011 to 2014. Ann Intern Med 2017; 167(10): 714–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaturvedi AK, Graubard BI, Broutian T, et al. Effect of Prophylactic Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination on Oral HPV Infections Among Young Adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(3): 262–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, Unger ER, Romero JR, Markowitz LE. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Adults: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019; 68(32): 698–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iversen OE, Miranda MJ, Ulied A, et al. Immunogenicity of the 9-Valent HPV Vaccine Using 2-Dose Regimens in Girls and Boys vs a 3-Dose Regimen in Women. JAMA 2016; 316(22): 2411–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019; 68(33): 718–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(33): 909–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dempsey AF, Zimet GD, Davis RL, Koutsky L. Factors that are associated with parental acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccines: a randomized intervention study of written information about HPV. Pediatrics 2006; 117(5): 1486–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn JA, Ding L, Huang B, Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL, Frazier AL. Mothers’ intention for their daughters and themselves to receive the human papillomavirus vaccine: a national study of nurses. Pediatrics 2009; 123(6): 1439–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downs JS, de Bruin WB, Fischhoff B. Parents’ vaccination comprehension and decisions. Vaccine 2008; 26(12): 1595–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Immunization Survey-Teen. A User’s Guide for the 2017 Public-Use Data File. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/nis/downloads/NIS-TEEN-PUF17-DUG.pdf.

- 15.Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr 2014; 168(1): 76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Statistical Methodology of the National Immunization Survey, 2005–2014. National Center for Health Statistics.. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imzmanagers/nis/methods.html. [PubMed]

- 17.Hanley SJ, Yoshioka E, Ito Y, Kishi R. HPV vaccination crisis in Japan. Lancet 2015; 385(9987): 2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corcoran B, Clarke A, Barrett T. Rapid response to HPV vaccination crisis in Ireland. Lancet 2018; 391(10135): 2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suppli CH, Hansen ND, Rasmussen M, Valentiner-Branth P, Krause TG, Molbak K. Decline in HPV-vaccination uptake in Denmark - the association between HPV-related media coverage and HPV-vaccination. BMC Public Health 2018; 18(1): 1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castro CJ. The Unbelievable Story of the HPV Vaccination Program in Colombia...From a Beautiful Dream to a Nightmare! 2018; 4(Supplement 2): 169s–s. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karafillakis E, Simas C, Jarrett C, et al. HPV vaccination in a context of public mistrust and uncertainty: a systematic literature review of determinants of HPV vaccine hesitancy in Europe. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019; 15(7–8): 1615–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Briones R, Nan X, Madden K, Waks L. When vaccines go viral: an analysis of HPV vaccine coverage on YouTube. Health Commun 2012; 27(5): 478–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keelan J, Pavri V, Balakrishnan R, Wilson K. An analysis of the Human Papilloma Virus vaccine debate on MySpace blogs. Vaccine 2010; 28(6): 1535–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margolis MA, Brewer NT, Shah PD, Calo WA, Gilkey MB. Stories about HPV vaccine in social media, traditional media, and conversations. Prev Med 2019; 118: 251–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen PR, Schmidtblaicher M, Brewer NT. Resilience of HPV vaccine uptake in Denmark: Decline and recovery. Vaccine 2020; 38(7): 1842–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kempe A, O’Leary ST, Markowitz LE, et al. HPV Vaccine Delivery Practices by Primary Care Physicians. Pediatrics 2019; 144(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Community Guide. Vaccination programs: provider reminders. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/vaccination-programs-provider-reminders (accessed April 2020).

- 28.Suk R, Montealegre JR, Nemutlu GS, et al. Public Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus and Receipt of Vaccination Recommendations. JAMA Pediatr 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen JD, Othus MK, Shelton RC, et al. Parental decision making about the HPV vaccine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19(9): 2187–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016; 12(6): 1454–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The World Health Organization: Ten Threats to global health in 2019. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- 32.Darden PM, Thompson DM, Roberts JR, et al. Reasons for not vaccinating adolescents: National Immunization Survey of Teens, 2008–2010. Pediatrics 2013; 131(4): 645–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dorell CG, Jain N, Yankey D. Validity of parent-reported vaccination status for adolescents aged 13–17 years: National Immunization Survey-Teen, 2008. Public Health Rep 2011; 126 Suppl 2: 60–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirth J, Kuo YF, Laz TH, et al. Concordance of adolescent human papillomavirus vaccination parental report with provider report in the National Immunization Survey-Teen (2008–2013). Vaccine 2016; 34(37): 4415–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.NCHS Data Brief: Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Among Adults Aged 18−26, 2013−2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db354-h.pdf (accessed March 2020). [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.