Abstract

Background

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors have been studied in association with a variety of risk factors. The aim of the present study was to determine if suicidal ideation in childhood was associated with genes previously associated with suicidal behaviors in adult samples and to determine if childhood aggression was associated with suicidal ideation.

Methods

A longitudinal study of children who were either from high or low risk for alcohol and other substance use disorders by familial background were assessed. The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) aggression scale scores with derived subtypes (physical and relational), and genetic variation (ANKK1, DRD2, COMT, SLC6A4, HTR2C) were used as predictors of the presence and onset of suicidal ideation in childhood using survival analysis. Structural equation models (SEM) were fit to determine the relative importance of the predictors controlling for background variables.

Results

Three SNPs in the HTR2C gene, one SNP in the ANKK1 gene, and two haplotypes, AAAC in the ANKK1-DRD2 complex and the CCC haplotype of the HTR2C gene and CBCL aggression, were significantly associated with the presence and onset of childhood suicidal ideation. Follow up in young adulthood showed a significant relationship between presence of suicidal ideation in childhood and young adult depression. SEM results showed improved prediction of suicidal ideation when genetic variation was combined with measures of aggression.

Conclusions

Genetic variation and presence of elevated aggression scores from the childhood CBCL are significant predictors of childhood suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation in childhood and being female are predictors of young adult depression.

Keywords: Suicidal Ideation, aggression, COMT, 5-HTTLPR, DRD2, ANKK1, HTR2C, depression

Introduction

The World Health Organization reports that annually approximately 800,000 lives are lost world-wide due to suicide (WHO, 2014). In 2016, the National Center for Health Statistics reported that the US suicide risk had surged to the highest levels in 30 years (Curtin et al., 2016). A recent report on suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STB) in teens shows an alarming increase between 2007 and 2015 with a doubling of the suicide rate for girls 15–19, reaching the highest point in 40 years (Curtin et al., 2017).

Among the known risk factors for adult suicidal behaviors is the presence of a psychiatric disorder as it occurs in over 90% of those attempting or dying by suicide (Qin, 2011). However, the genetic diathesis for suicidal behavior and the presence of psychiatric disorders appear to be distinct (Brent and Mann, 2006). The most common disorders associated with suicide are major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and substance use disorders (Nock et al., 2010; Bachmann, 2018).

Accordingly, elucidating the impact of childhood STB on later development of psychiatric disorders, especially depression in young adulthood, is important for prevention efforts. This relationship has been studied only infrequently from a longitudinal perspective. However, one longitudinal study found childhood STBs to be a robust predictor of adult STBs, though adult psychiatric conditions including depression appeared to be accounted for by additional factors (Copeland et al 2017)..

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors have been studied in association with a variety of risk factors (Franklin et al., 2017). Although suicidal thoughts have lesser severity than suicide attempts, there is evidence to suggest that in both adults (Kessler et al., 1999; Nock et al., 2008) and in adolescents (Reinherz et al.,2006) suicidal thoughts are on a continuum of suicidal risk having important clinical implications. Importantly, an earlier age of onset of suicidal thoughts is significantly associated with greater risk of having a suicide plan and/or making an attempt among those with ideation (Nock et al., 2008). Accordingly, assessment of suicidal thoughts early in the lifespan may provide important information on risk for later development of other STBs.

Aggression is a behavioral trait that has been associated with elevated suicidal behaviors in both adults (Turecki, 2005; Swogger et al., 2014; Singh and Rao, 2018) and in child/adolescent samples (See Hartley et al., 2018 for review). It has been suggested that impulsive-aggressive traits are part of a developmental cascade that increases risk for suicidal behaviors among some subsets of individuals (Turecki, 2005). Follow-up of Finnish boys who bullied others at age 8 found increased rates of depression and suicidal ideation during their Finnish military call-up examination at age 18 (Klomek et al 2008), supporting the idea that aggressive traits are part of the risk for STB.

Identification of genetic risk factors and endophenotypes associated with suicidal behaviors offers the potential for improved screening by predicting which individuals may need greater surveillance. Candidate gene and genome-wide association (GWAS) methods offer complementary approaches to uncovering the genetic contribution to common diseases and behavioral disorders. Both approaches have been utilized to uncover possible associations between suicidal behavior and specific genetic variants offering the potential to provide information useful in drug discovery and behavioral interventions for prevention of suicidal behaviors.

Candidate gene studies of suicidal behaviors have largely focused on the serotonergic and dopaminergic pathways. Allelic variation in the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4 (5HTTLPR) gene confers lower expression (S + LG) while LA increases expression. Low expressing alleles and genotypes are associated with increased risk STBs (Young et al., 2008; Haberstick et al., 2016; Rahikainen et al., 2017; Sarmiento-Hernández et al., 2017) though the L allele (unspecified LG or LA) has also been reported to be associated with increased risk (Shinozaki et al., 2013; Daray et al., 2018) in others. A meta-analysis of 15,341 subjects suggests that inconsistency may be due to variation in the subtypes studied (Fanelli and Serretti, 2019). These included whether the suicidal behavior (attempts) occurred in substance abusers and whether the suicide attempts were violent.

Dopaminergic involvement in suicidal behavior has been shown for the DRD2 gene (Jasiewicz et al., 2014; Preuss et al., 2015; Genis-Mendoza et al., 2017). Two polymorphisms in the DRD2 gene (rs6275 and rs179978) and nearby ANKK1 gene (rs1800497) analyzed for association with suicide attempts found a 3-fold increase in attempts for those with the ANKK1 TT genotype (Genis-Mendoza et al., 2017). Similarly, DRD2-ANKK1 haplotypes studied in alcohol dependent participants showed a significant relationship to history of suicide attempts (Jasiewicz et al., 2014).

Variation in the Catechol-o-Methyltransferase (COMT) gene, the enzyme involved in breakdown of the precursor of dopamine, has been studied with suicidal behavior (Sun et al., 2016; Ru et al., 2017; Bernegger et al., 2018; González-Castro et al., 2018). The Val allele shows protective effects in some studies (Ru et al., 2017; González-Castro et al., 2018) but is associated with greater suicide attempts in others (Baud et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2016) and no effect in one (Zhang et al., 2019). In those with affective disorders and a history of childhood maltreatment, one COMT haplotype appears to increase suicidal behaviors (Bernegger et al., 2018). Interestingly, the Met allele has been reported to increase the likelihood of aggressive behavior (Rujescu et al., 2003; Nedic et al., 2011) and to increase the likelihood of violent suicide attempts (Nedic et al., 2011).

A recent GWAS study compared 6,569 adult suicide attempters with either major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia to 17,232 to adults without attempts finding one genome-wide significant result for each of the disorders (Mullins et al., 2019). However, a significant replication in independent samples could not be found. Interestingly, four previous GWAS studies have also reported significant results within but not across studies (Perlis et al., 2010; Schosser et al., 2011; Willour et al., 2012; Mullins et al., 2014).

Another approach to increase gene finding is the oversampling of individuals who are at ultra high-risk for psychiatric disorders associated with increased suicidal risk. It is clear that psychiatric disorders are associated with death by suicide with 90% of cases having one or more disorders (Bertolotte et al 2004). Comorbid bipolar and alcohol use disorders increases risk for suicidal behavior (Oquendo et al 2010). However, even when the effect of having a psychiatric disorder is controlled, alcohol and drug use predicts subsequent suicide attempts (Borges et al 2000). Relative to rates for the general population, having an alcohol and drug use disorder elevates the risk for death by suicide 10–14 fold (Wilcox et al 2004).

The present set of analyses were undertaken to utilize data from a valuable cohort selected for longitudinal assessment. The participants were members of families first identified through a proband with multiple relatives with alcohol dependence (AD) (multiplex for alcohol dependence families) or an index case with an absence of AD members (control families). The offspring from the proband generation participated in longitudinal data collection spanning childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. These offspring from multiplex families show an increased risk for developing substance use disorders relative to offspring of controls (Hill et al 2008). The present report is based on data from the longitudinal data collection and genetic analysis of candidate genes.

The offspring cohort provided the opportunity for determining the influence of two factors: (1) aggressive behaviors in childhood/adolescence and (2) selected genetic variants on the incidence of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence. Additionally, the influence of suicidal thoughts and aggressive behavior including their subtypes (relational and physical) from childhood/adolescent follow-ups were tested for their association with young adult depression.

Methods

Participants

The prospective longitudinal family study of third generation offspring included multiple assessments at approximately yearly intervals in childhood and biennially in young adulthood. Families were selected through the parent generation and included collection of data for the 1st generation grandparents. Selection of multiplex families was based on the presence of two same-sex adult siblings with AD within the family. These multiplex families were considered to be at high-risk for transmission of alcohol and other substance use disorders within the family. Control families were selected on the basis of having two same-sex adult siblings and minimal familial psychiatric disorders including substance use disorders within the family. The study has ongoing approval from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. All participants provided consent at each visit. Children provided assent with parental consent.

Follow-Up Samples

Children/adolescents between the ages of 8–18 years who were the offspring of second generation family members were eligible to participate. A total of 478 participants from the local community were enrolled in the child/adolescent follow-up that involved repeated assessments until age 19. A total of 330 individuals with child/adolescent evaluations continued their participation in a young adult follow up. Demographic characteristics of the subsamples are seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants.

| Participants with Childhood Evaluations (N = 478) (%) | Participants with Childhood Evaluations and DNA (N=377) (%) | Participants with Child and Young Adulthood Evaluations (N = 330) (%) | Participants with Child and Young Adulthood Evaluations with Aggression Measure Age 14 (N = 272) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 243 (50.8) | 196 (51.9) | 169 (51.2) | 145 (53.3) |

| Female | 235 (49.2) | 181 (48.0) | 161 (48.8) | 127 (46.7) |

| High Risk | 252 (52.7) | 218 (57.8) | 179 (54.2) | 138 (50.7) |

| Low Risk | 226 (47.2) | 159 (42.2) | 151 (45.8) | 134 (49.3) |

| SES | 41.82 ±12.42 | 40.67 ± 12.39 | 42.33 ± 12.40 | 42.76 ± 12.28 |

| Age First Childhood Visit | 11.57 ± 2.94 | 11.47 ± 2.89 | 12.28 ± 2.61 | 11.34 ± 2.20 |

| Age Last Visit Childhood | 16.34 ± 3.40 | 16.56 ± 2.29 | 17.10 ± 1.71 | 17.22 ± 1.24 |

| Number of Childhood Visits | 4.47 ± 3.06 | 4.73 ± 3.03 | 5.31 ± 2.72 | 6.25 ± 2.49 |

| Age Last Visit Young Adulthood | 26.06 ± 4.59 | 26.27 ± 4.48 | 25.54 ± 4.39 | 25.15 ± 4.12 |

| Number of Young Adult Visits | 2.36 ±1.91 | 2.59 ± 1.92 | 3.02 ±1.64 | 2.55 ± 1.94 |

Chi-square tests were performed to determine if the proportion of males and females and the proportions of high and low-risk participants differed across sub-samples. The proportion of males and females seen in the childhood sample did not differ from the three sub-samples. The proportion of High-Risk and Low-Risk participants seen in childhood did not differ significantly from the three sub-samples.

Clinical Assessment

Clinical diagnoses obtained during childhood/adolescence (before age 19) were determined by administering the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS), (Chambers et al., 1985) followed by a best estimate consensus diagnosis (Hill et al., 2008). To provide normative data for childhood assessment of psychopathology, the Child Behavior Checklist was administered. Young adults (ages 19 and above) were interviewed with a structured psychiatric interview, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Janca et al., 1992) providing DSM-IV diagnoses including major depressive disorder.

CBCL Aggression

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, 1991), a clinician administered instrument was administered to mothers of the child/adolescent participants. The CBCL aggression scale provided T-scores. A score of 50 represents average normal population values, with T-scores equal or greater than 55 considered as potentially problematic.

CBCL Aggression Subtypes

Relational and physical aggression subtypes were constructed from CBCL item responses that were based on subscales originally developed by Ligthart et al (2005) using principal component analysis with varimax rotation. The Relational Aggression scale was derived from 20 items that included responses to “Argues a lot” has “Temper tantrums or a hot temper.” The Direct Aggression (physical aggression) scale was derived from 6 items including “Physically attacks people” and “Destroys things belonging to his/her family or others.” Each item was scored on a 0–2 point scale with 0 indicating the behavior did not occur, 1 indicating that it occurs sometimes and 2 indicating that it always occurs.

Suicidal ideation and Attempts

The K-SADS interview includes questions regarding the presence or absence of suicidal ideation that is scored for increasing severity. Questions concerning suicide attempts, their frequency and seriousness are also covered. These suicidal behaviors are obtained from mother and child separately and a summary score determined based on the clinicians weighting of the information obtained.

Genetic Methods

5-HTTLPR

The 5HTT-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) was amplified using primer sequences described by Wendland et al. (Wendland et al., 2006) to reveal the long (L) and short (S) variant. To test for the more accurate triallelic characterization (Hu et al., 2006), a single nucleotide polymorphism, rs25531, was digested with the restriction endonuclease Hpall and visualized with agarose gel electrophoresis. Genotypes were determined using the L and S variation along with the rs25531 A or G nucleotide (LA, LG, SA, or SG). The three genotypes were: LL (LALA), LS (LALG or LAS), and SS (LGLG, LGS, SASG, or SS).

COMT, DRD2, ANKK1, and HTR2C Genotyping

Genotyping of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism, DRD2, ANKK1 and HTR2C genotypes was completed on a Biotage PSQ 96MA Pyrosequencer (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Each polymorphism was analyzed by PCR amplification incorporating a biotinylated primer. Thermal cycling included 45 cycles at an annealing temperature of 60°C. The Biotage workstation was used to isolate the biotinylated single strand from the double strand PCR product. The isolated product was then sequenced using the complementary sequencing primer.

Statistical Methods

Survival Analyses

Modeling of factors associated with child/adolescent suicidal thoughts was performed using survival analysis that utilized the first age of onset of thoughts during the child/adolescent follow-up period. A Cox Proportional Hazard procedure (SPSS 20) was used to evaluate potential covariates of importance. When a single variable explained substantial variation in outcome, survival analysis was also performed using the Kaplan-Meier procedure and plotted for illustration. Genetic variation was modeled one gene at a time for individual SNPs and for each haplotype block.

Structural Equation modeling (SEM)

SEM was performed using MPlus, version 7.4 (Muthen and Muthen,1998–2012) to model the effects of child/adolescent suicidal ideation, aggression (total, relational, and physical) on the presence of young adult DSM IV depression. CBCL total aggression measures were based on data acquired when the participants were age 13 or 14 years old (one measure per person). Data for 272 participants were available for modeling the joint effects of these variables.

Familial risk for AD, defined in terms of presence/absence of alcohol use disorder (AUD) family membership, gender, and socioeconomic status (SES) in childhood were included in the analyses. SES was determined using the Hollingshead Four Factor Model of SES that is based on job category and education (Hollingshead, 1975). Onset of young adult depression (DSM-IV) was modeled as a latent variable using a discrete time survival model in Mplus (Muthen and Masyn, 2005). Based on data inspection, data for all variables were assumed to be missing at random. The maximum-likelihood parameter estimation used provided unbiased parameter and error estimates.

SEMs were fit with the ANKK1-DRD2 and HTR2C haplotypes, and CBCL aggression T-scores (< = 54 versus >55) on young adult depression. The presence of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence was modeled as a potential mediation effect. Next, aggression subtypes were modeled, replacing the dichotomous CBCL aggression classification with the subtypes of relational and physical aggression.

Genetic Data

Nine SNPs were analyzed: ANKK1–rs4938012, rs4938015, rs1800497; DRD2–rs6277; HTR2C–rs3813929, rs518147, rs6318; COMT–rs4680 and SLC6A4 5-HTTLPR.

Genetic Inference

SNPs were tested for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). None of the 9 SNPs tested were found to have p-values below a Bonferroni adjusted threshold (<0.0056) indicating significant violation of HWE. ANKK1-DRD2 rs4938012-rs4938015-rs1800497-rs6277 and HTR2C rs3813929-rs518147-rs6318 haplotypes were imputed using the program PHASE version 2.1.1 (Stephens et al., 2001; Stephens and Donnelly, 2003). Four haplotype blocks with sample frequency greater than 0.05 were found for ANKK1-DRD2 and three blocks for HTR2C.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

Characteristic for each developmental period and the number of individuals available are presented in Table 1.

Familial Risk for AD and Substance Use Disorder Outcome

Familial risk for AD was significantly associated with development of SUD in childhood/adolescence or young adulthood (Cox survival Wald Χ2 =23.6, df =1, p < 0.0001).

Familial Risk for AD and Aggression

Bivariate correlations for total CBCL aggression, and for relational and physical aggression subtypes, controlling for sex, showed significant associations between familial risk and aggression scores at each age. Significant correlations were seen at age 12: physical aggression (r=0.21, df=1,152, p=0.01) and relational aggression (r=0.27, df =1,152, p=0.001), and similarly, at age 14: physical aggression (r= 0.15, df=1,218, p=0.03) and relational aggression (r= 0.15, df =1,218, p =0.03) were significant.

SUD and Onset of Young Adult Depression

The presence of SUD in childhood/adolescence or young adulthood was significantly associated with young adult depression (Cox survival Wald Χ2 =17.9, df =1, p < 0.0001).

Survival Analysis of Child/Adolescent Suicidal Thoughts and Aggression

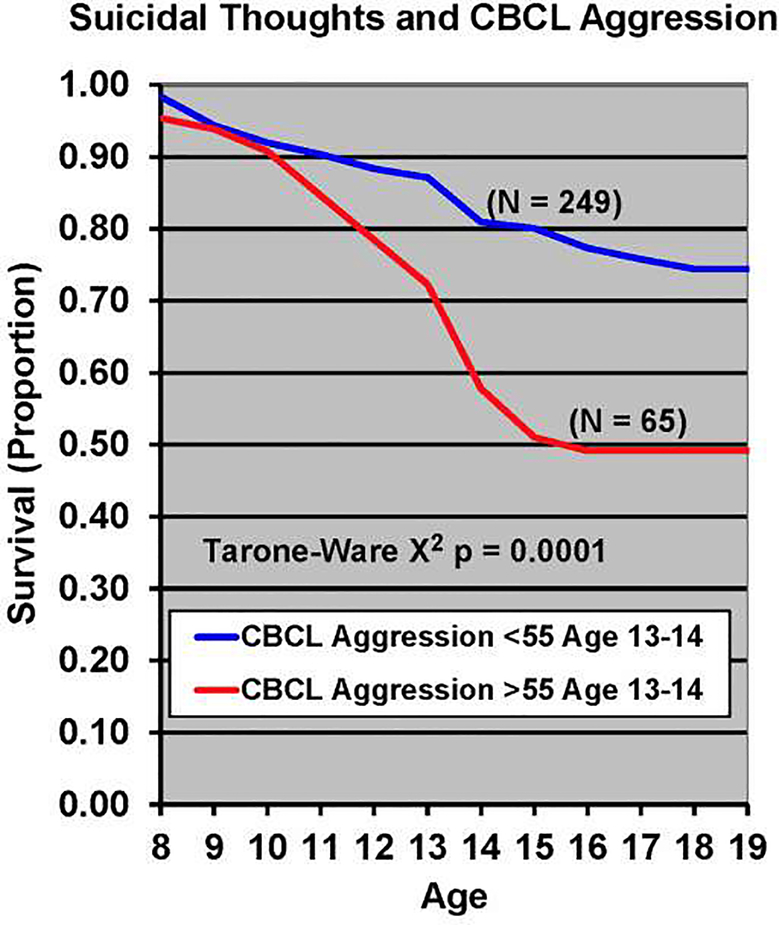

In the sample of 478 participants with suicidal thought data collected between the ages of 8–18, 124 (25.9%) reported having suicidal thoughts at one or more visits. These thoughts occurred for the first time at a mean age of 12.7 ± 2.9 years; range = 8–18 years; median =13 years. Total CBCL aggression scores (< or = T score of 54, or > or = 55, at ages 13 or 14), were used in a Cox survival model. Although children were seen at approximately yearly intervals, not all children had an evaluation at age 14. In order to maximize available cases, scores at either age 13 or 14 were used. Sex and familial risk status were included as covariates. A significant association was seen between elevated aggression (presence of a T score greater than 55) and report of suicidal thoughts during childhood/adolescence (Tarone-Ware, Chi square =17.38, df=1, p<0.0001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed significantly different survival curves for onset of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence with CBCL aggression T scores = or < than 54 versus those that were > 55.

Survival Analysis of Child/Adolescent Suicidal Attempts and Aggression

From the total of 478 children assessed, data for attempts was available for 477. A total of 17 children (3.6%) had made an attempt during the child/adolescent follow-up period (ages 8–18) at a mean age of 14.9 ± 1.7 years (range 12–17 years). Of these, 10 children (4.1%) with aggression data had made an attempt by age 19, the end of the childhood follow-up. Aggression was modeled using values obtained at ages 11–12 (N=243) as a potential antecedent of suicide attempt. A Cox Survival analysis found childhood aggression was significantly associated with suicide attempts (Wald = 6.02,df=1, p=0.01) but sex and familial risk status was not. Because the Cox proportional hazards model assumes equal likelihood of the hazard across the observation window, and this could not be directly tested, a non-parametric survival analysis (Kaplan-Meier) was also performed. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis confirmed that having CBCL aggression T scores > 55 was associated with suicide attempts during the child/adolescent follow-up (Chi square = 8.86, df =1, p=0.003).

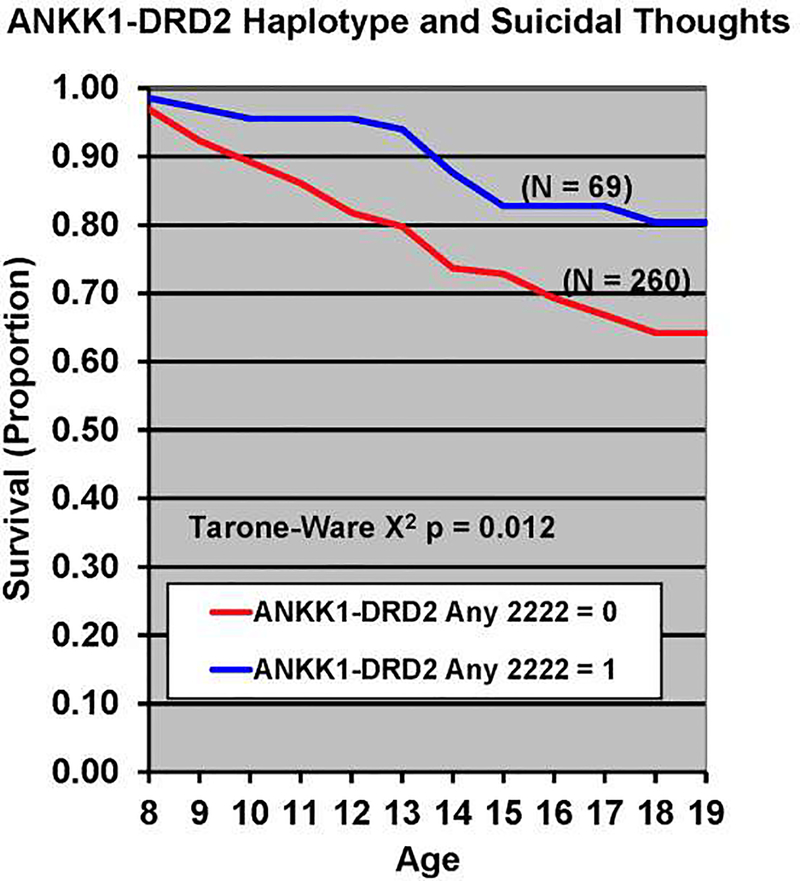

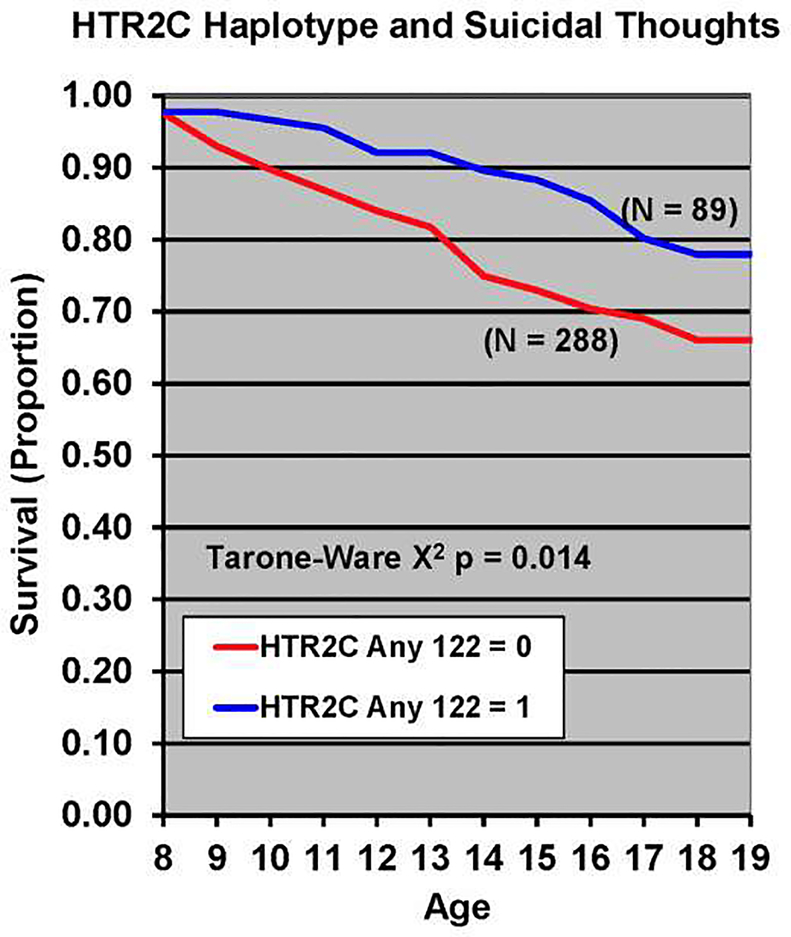

Survival Analysis of Child/Adolescent Suicidal Thoughts- Genetic Variation

The age of onset for suicidal thoughts in childhood revealed both nominally significant and non-significant effects for individual SNPs (Table 2). Specific haplotypes within the ANKK1-DRD2 and HTR2C were tested as potential predictors of suicidal thoughts in childhood and found to have statistically significant protective effects. The ANKK1-DRD2 A-A-A-C haplotype and the HTR2C C-C-C haplotype (Table 2) were significantly associated with the absence of suicidal thoughts in childhood. The ANNK1-DRD2 effect is illustrated in Figure 2 and HTR2C in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Genetic variance associated with childhood suicidal ideation based on survival analysis (Cox Proportional Hazards).

| Gene | SNP/Haplotype | Chromosome | Location (GRCh38.p12) | Intron/Exon | Major Nucleotide | Minor Nucleotide | Risk Nucleotide | p = |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANKK1 | rs4938012 | 11 | 111,388,932 | Intron 1 | G | A | - | ns |

| ANKK1 | rs4938015 | 11 | 113,393,922 | Intron 2 | G | A | - | ns |

| ANKK1 | rs1800497 | 11 | 113,400,106 | Exon 9 | G | A | A | 0.009a |

| DRD2 | rs6277 | 11 | 113,412,737 | Exon 10 | T | C | nsb | |

| COMT | rs4680 | 22 | 19,963,748 | Exon 8 | G | A | - | ns |

| HTR2C | rs3813929 | X | 114,584,047 | Promoter | C | T | - | ns |

| HTR2C | rs518147 | X | 114,584,109 | Exon 1 | G | C | C | nsc |

| HTR2C | rs6318 | X | 114,731,326 | Exon 5 | G | C | C | 0.027d |

| SLC6A4 | 5HTLPR | 17 | 30,237,328 | Promoter | La | Lg or S | Lg or S | ns e |

| ANKK1-DRD2 | Haplotype | 11 | rs4938012- rs49383015- rs1800497- rs6277 | AAACf | 0.018 | |||

| HTR2C | Haplotype | X | rs3813929-rs518147- rs6318 | CCCf | 0.029 | |||

Genotyype difference = 0.009; presence of A nucleotide =0.01.

Genotype was not significant; presence of any T nucleotide = 0.082

Genotype was not significant; presence of C nucleotide = 0.032

Genotype was significant at 0.027; presence of any C nucleotide = 0.029

Genotype was not significant; presence of Lg or S =0.065

This is a protective haplotype associated with lesser suicidal ideation.

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed significantly different survival curves for onset of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence for those with the AAAC haplotype (presence =1) and those without this haplotype (absence =0).

Figure 3:

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed significantly different survival curves for onset of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence for those with the CCC haplotype (presence =1) in comparison to those without this haplotype (absence =0).

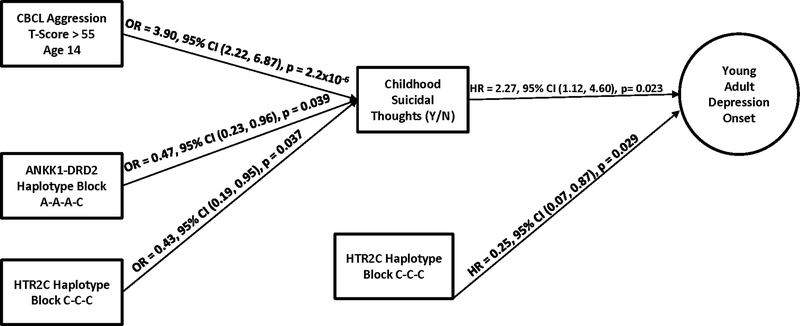

Structural Equation Model (SEM) Results

Based on the results of survival analyses that tested each SNP and haplotype for association with child/adolescent suicidal ideation, those with significant results were incorporated into SEM models. No gender effect, familial risk effect, or effect of parental socioeconomic status in childhood was found in the aggression models of suicidal thought onset. Two significant haplotypes, ANKK1-DRD2 and HTR2C reported in Table 2 were considered together with CBCL aggression.

A test of an additive model was performed that included the ANKK1-DRD2 A-A-A-C haplotype block and the binary status (yes/no) CBCL aggression T-Score = or > 55. Those with the ANKK1-DRD2 A-A-A-C haplotype had a reduced hazard (HR = 0.44, p = 0.031) for suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence. Those with greater CBCL aggression had an increased hazard of suicidal ideation (HR = 3.80, p = 4.5 × 10−6). A second additive model was tested with the HTR2C C-C-C haplotype block and the binary CBCL aggression T-Scores (=< 54 versus => 55). Those with the HTR2C C-C-C haplotype had a reduced hazard of having suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence (HR = 0.41, p = 0.027). Those with greater CBCL aggression showed an increased hazard (HR = 3.67, p = 1.9 × 10−6).

When the ANKK1-DRD2 A-A-A-C and HTR2C C-C-C haplotypes were considered jointly (Figure 4), the haplotype estimates were essentially unchanged with ANKK1-DRD2 A-A-A-C haplotype estimate (OR = 0.47, p = 0.039) and HTR2C C-C-C haplotype estimate (OR = 0.43, p = 0.037). The CBCL aggression T-Score estimate in the joint haplotype model was consistent with the estimates obtained when evaluated alone, namely increased risk for having suicidal ideation in association with greater aggression scores. Aggression scores combined with the genetic variation in the ANKK1-DRD2 A-A-A-C and HTR2C C-C-C haplotypes (presence or absence of the haplotype) revealed an overall odds ratio of 3.90, p = 2.2 × 10−6 for developing suicidal ideation in childhood.

Figure 4:

Structural equation modeling revealed a significant relationship between CBCL aggression scores and childhood suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation in childhood/adolesecence along with being female predicted the presence of depression in young adulthood.

Onset of Young Adult Depression, Suicidal Ideation, and Aggression

The presence or absence of depression in young adulthood included 330 cases among those having childhood data. A total of 44 cases (13.3%) were positive for depression. The mean age of onset was 23.3 years ± 3.2 years; median =22.0 years with range of 19–33 years. The presence of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence was significantly associated with elevation in depression in young adulthood (20.6%) relative to those without thoughts (10.3%); Kaplan-Meier survival difference (Tarone-Ware Χ2 = 6.58, df=1, p=0.01).

CBCL total aggression in the context of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence was a significant predictor of young adult depression. The age of onset for meeting criteria for depression was utilized in the SEM model (Figure 4) that included a survival parameter. This analysis also included genetic variants reducing the number of cases (N=272) (Table 1). A possible mediating relationship of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence on the relationship between child/adolescent aggression and the presence or absence of depression and its onset was also considered. CBCL aggression T-Score = > 55 (yes/no) was associated with increased odds of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence (OR = 6.37, p = 5.4 × 10−7). The presence of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence was significantly associated with depression and its onset in young adulthood (HR = 3.58, p = 0.004). Having a CBCL aggression T-Scores over 55 was not a significant predictor of depression onset in young adulthood, though an indirect effect of CBCL total aggression mediated by suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence was found (HR = 1.71, p = 0.013). The total effect of CBCL aggression was not significant. Sex (female) was associated with a greater hazard for young adult depression, HR = 3.12, p = 0.005. Familial risk for AD or childhood SES were not significant in these models.

A second model tested the effect of the subtypes of aggression, physical and relational (ages 13–14) on the age of onset of depression in young adulthood. Higher relational aggression was associated with increased odds of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence (OR = 1.16, p = 0.002) but physical aggression was not. Importantly, the presence of suicidal thoughts in childhood/adolescence was associated with depression onset in young adulthood (HR = 3.59, p = 0.004). Additionally, an indirect effect of relational aggression was found, mediated by childhood/adolescence suicidal thoughts (HR = 1.03, p = 0.022). The total effect of relational aggression on young adult depression onset showed a significant elevation (HR = 1.08, p = 0.037). Being female was also associated with a greater hazard for young adult depression, HR = 3.49, p = 0.002. No effect of familial risk for alcohol dependence was seen in this model.

Discussion

The present analyses were undertaken to elucidate the possible association of childhood/adolescent aggression and its subtypes, physical and relational, in combination with genetic variation with the presence of suicidal ideation in childhood/adolescence. A second goal was to utilize our longitudinal data to determine if suicidal ideation during this period is a predictor of young adult depression. Because the presence of depression is a risk for suicidal behaviors, identifying precursors of young adult depression could aid in identifying those with increased risk.

The current findings suggest that aggressive behaviors identified as early as childhood/adolescence may be useful in identifying those at increased risk for STBs and in turn those at increased risk for young adult depression, a risk factor for suicidal behaviors. Additionally, relational aggression, or the tendency to malign or bully others without directly displaying physical aggression, appeared to be more salient in its association with increasing risk for STB in our cohort. These findings have implications for identification of children with greater tendencies to aggression because parents and teachers may find it easier to recognize physically aggressive children than those who plot to turn other children against each other.

Previous studies have shown an association between aggressive traits and elevated risk for suicidal behaviors in adults (Turecki, 2005; Swogger et al 2014; Singh and Rao, 2018). Fewer studies have assessed the relationship between aggression and STB in children and adolescents. A meta-analysis of 4,693 children and adolescents (Hartley et al 2018) reported a statistically significant association between reactive aggression (physical) and suicidal behaviors, though most studies included did not directly measure subtypes of aggression. Many used the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory that provides measures of physical and verbal aggression, anger and hostility (Buss and Perry, 1992) but does not directly measure relational aggression as defined by Ligthart et al 2005. In others, a relationship between physical aggression (reactive aggression) but not relational aggression (proactive) (Fite et al 2009; Greening et al 2010) was reported though based on the six item Dodge and Cole (1987) questionnaire. Notably, these studies were conducted with psychiatric inpatients and may represent children with more severe psychopathology. Unlike results of these studies, we find relational aggression associated with STBs possibly as a result of differing instrumentation and source of participants.

A comment is needed regarding the absence of significance of familial risk for addiction in the SEM model. Our participants were community-dwelling volunteers assessed in the context of a research design that included offspring from families with multiple cases of addiction and those selected to be a low risk by family background. Familial risk was associated with development of SUD. However, not all high risk offspring developed SUD in the course of the study. When the SUD of the participant was entered into a survival model, we do find it to be a significant antecedent of young adult depression.

In the present analyses, the genetic variants identified as being associated with childhood/adolescent ideation are not novel as they have been reported in previous studies. Indeed, our candidate genes were selected largely based on reports of their association with suicidal behaviors in adults. Our results suggest specific genetic variation is associated with childhood/adolescent suicidal behaviors.

Our results for the serotonin transporter gene, though not statistically significant, did show a trend (p=0.065) for the Lg or S variants to be associated with suicidal ideation in childhood, consistent with reports in adult samples (Young et al 2008; Rahkainen et al 2017; Sarmiento-Hernández et al., 2017). The other serotonergic variant, HTR2C was assessed using three SNPs: (1) rs3813929, a variant in the promoter region; (2) rs518147, a SNP located in exon 1; and (3) rs6318 located in exon 5, with significance found for one of these, rs6318. Analysis that focused on presence or absence of the minor allele revealed the C nucleotide as a risk allele for suicidal ideation.

We investigated the role of the dopaminergic pathway in child/adolescent suicidal ideation by including COMT, ANKK1 and DRD2. COMT variation did not show significant results for suicidal ideation in childhood/adolescence though a number of studies have reported an association with suicidal behavior in adults. Adult affective disorder patients with retrospective report of childhood maltreatment have revealed COMT haplotypes associated with suicidal behaviors (Bernegger et al 2018). However, a meta-analysis of COMT involving 17 studies reported mixed results with increased risk found for the Val allele in males and a protective effect for females (Gonzalez-Castro et al 2018). Although we did not find an association between COMT variation and childhood suicidal ideation, only one SNP, rs4680, was studied.

The ANKK1 gene has frequently been studied in the context of DRD2 variation due to their adjacent location on chromosome 11 and evidence of a functional synergism. Haplotypes of the ANKK1-DRD2 complex have been shown to be associated with suicide attempts in alcohol dependent individuals (Jasiewicz et al 2014). The present study investigated the DRD2-ANKK1 region for potential association with suicidal ideation in a sample of children half of whom were at high risk for developing alcohol dependence because of their familial loading. The ANKK1 gene (rs1800497) revealed a significant association with suicidal ideation. Including familial risk for alcohol dependence as a covariate in the survival model did not alter the significance. These results are consistent with the report of Genis-Mendoza et al 2017 in which individuals with the ANKK1 TT genotype had a 3-fold greater likelihood of having made a suicide attempt.

The current study has some limitations. First, in view of large-scale meta-analyses, the sample size utilized here is quite modest. Second, the study did not use a population-based ascertainment strategy but rather chose those who were at greater risk of developing a substance use disorder because of their familial risk for addiction or those from control families with minimal risk for developing a substance use disorder based on the constellation of relatives.

Although the absence of a large scale population-based strategy is a limitation, the strengths of our study include the deep phenotyping performed across an extended longitudinal data collection procedure. Data were collected from the same individuals who provided frequent, approximately annual multi-modal assessments across childhood and adolescence and biennial evaluations in young adulthood.

Third, child/adolescent assessments were conducted between 1990 and 2010. (The assessment window exceeded 10 years [8–18] in order to include all siblings as they aged into the study). The rates of suicidal behaviors observed in our cohort may be an underestimate of what would be seen today because of the increased trends in STBs seen in the past decade. Rates of suicidal thoughts and attempts have been growing in youth based on emergency room visits. Using data from 30,000 ER visits, Burstein et al (2019) analyzed diagnostic codes (suicidal ideation or attempt) to track changes between 2007–2015 reporting an increase from 2.8% and 3.5% during this period (Burstein et al 2019).

Finally, one additional positive feature of the study is its focus on a sample enriched in terms of familial risk for alcohol use disorders and a comparison group selected for low familial AUD risk providing an unusual opportunity to evaluate genetic, socioeconomic, and aggressive behavior of childhood while taking into account familial risk for AUD, itself a well-established indicator of elevated risk for suicidal behavior.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that specific haplotypes within ANKK1-DRD2 and HTR2C genes confer risk or resilience to the development of suicidal ideation in childhood depending on the individuals’ genetic background. Prediction of which children will develop suicidal ideation is aided by determination of overall levels of CBCL aggression and particularly the relational aggression component. The importance of childhood aggression in STBs is emphasized by the significant association of aggression scores and suicidal attempts in childhood, though admittedly based on a small number of cases. The results further suggest that suicidal ideation in childhood/adolescence is a mediator for depression in young adulthood. These observations have the potential to provide a framework for precision medicine that utilizes both genetic variation and phenotypic markers for early intervention and treatment. Prospective follow up of this cohort may provide new insights about the persistence or amelioration of associated suicidal behaviors.

Highlights.

ANKK1-DRD2, HTR2C and aggression are associated with childhood suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation predicts young adult depression

Acknowledgments

We want to express our sincere appreciation to the research participants who have taken the time to make multiple visits to our lab over the years. We thank the many members of our research team involved in the longitudinal data collection that has spanned over two decades. We are especially grateful for the support of Jeannette Wellman, Nicholas Zezza and Brian Holmes. Also, we want to thank NIAAA for the long term funding to make the research possible.

Funding Source and Role:

This research was supported in part by awards from the National Institute of Health/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) awards: AA 05909, AA 08082, AA015168 and AA021746. The NIH/NIAAA did not influence the design of the study or the preparation of the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement:

Data described in this manuscript will not be made available because public availability would compromise participant privacy. Data were collected before the era of data sharing so consent forms did not include a statement that data would be shared. We are in the process of attempting contact and collection of consent for sharing but currently do not have permission to share the data described herein.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM, 1991. Manual for Child Behavior Checklist/ 4–18 and 1991 Profile Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann S, 2018. Epidemiology of suicide and the psychiatric perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 1425 10.3390/ijerph15071425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baud P, Courtet P, Perroud N, Jollant F, Buresi C, Malafosse A, 2007. Catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism (COMT) in suicide attempters: a possible gender effect on anger traits. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet 144B, 1042–1047. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A, 1979. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 47, 343–352. 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernegger A, Kienesberger K, Carlberg L, Swoboda P, Ludwig B, Koller R, Inaner M, Zotter M, Kapusta N, Aigner M, Haslacher H, Kasper S, Schosser A, 2018. The impact of COMT and childhood maltreatment on suicidal behaviour in affective disorders. Sci. Rep 8, 692 10.1038/s41598-017-19040-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotte JM, Fleischmann A, De Leo D, Wasserman D, 2004. Psychiatric diagnoses and suicide: revisiting the evidence. Crisis 25: 147–155. 10.1027/0227-5910.25.4.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Walters E, Kessler RC, 2000. Associations of substance use, abuse and dependence with subsequent suicidal behavior. Am. J. Epidem 151, 781–789. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Mann JJ, 2006. Familial pathways to suicidal behavior-understanding and preventing suicide among adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med 355, 2719–2721. 10.1056/NEJMp068195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein B, Agostino H, Greenfield B 2019. Suicidal attempts and ideation among children and adolescents in US emergency departments 2007–2015. JAMA Pediatr 173, 598–600. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Perry M,1992. The aggression questionnaire. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol, 63, 452–459. 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers W, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, Paez P, Ambrosini P, Tabrizi MA, Davies M, 1985. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview: test-retest reliability of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children, present episode version. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 42, 696–702. 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Goldston DB, Costello EJ, 2017. Adult associations of childhood suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A prospective, longitudinal analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 56, 958–965. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin S, Hedegaard H, Minino A, Warner M, Simon T, 2017. QuickStats: Suicide rates for teens aged 15–19 years, by sex - United States, 1975–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 66, 816 10.15585/mmwr.mm6630a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin S, Warner M, Hedegaard H, 2016. Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999–2014 NCHS data brief, no 241. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db241.htm (accessed 3 December 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Daray FM, Arena AR, Armesto AR, Rodante DE, Puppo S, Vidjen P, Portela A, Grendas LN, Errasti AE, 2018. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism as a predictor of short-term risk of suicide reattempts. Eur. Psychiatry 54, 19–26. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JD, 1987. Social-information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol, 53, 1146–1158. 10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli G, Serretti A, 2019. The influence of the serotonin transporter gene 5-HTTLPR polymorphism on suicidal behaviors: a meta-analysis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 88, 375–387. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fite PJ, Stoppelbein L, Greening L, 2009. Proactive and reactive aggression in a child psychiatric inpatient population. J. Clin. Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38, 199–2005, 10.1080/15374410802698461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, Musacchio KM, Jaroszewski AC, Chang BP, Nock MK, 2017. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol. Bull 143, 187–232. 10.1037/bul0000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genis-Mendoza AD, López-Narvaez ML, Tovilla-Zárate CA, Sarmiento E, Chavez A, Martinez-Magaña JJ, González-Castro TB, Hernández-Díaz Y, Juárez-Rojop IE, Ávila-Fernández Á, Nicolini H, 2017. Association between polymorphisms of the DRD2 and ANKK1 genes and suicide attempt: a preliminary case-control study in a Mexican population. Neuropsychobiology 76, 193–198. 10.1159/000490071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Castro TB, Hernández-Díaz Y, Juárez-Rojop IE, López-Narváez ML, Tovilla-Zárate CA, Ramírez-Bello J, Pérez-Hernández N, Genis-Mendoza AD, Fresan A, Guzmán-Priego CG, 2018. The role of COMT gene Val108/158 Met polymorphism in suicidal behavior: systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat 14, 2485–2496. 10.2147/NDT.S172243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greening L, Stoppelbein L, Luebbe A, Fite PJ, 2010. Aggression and risk for suicidal behaviors among children. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior 40, 337–345. 10.1521/suli.2010.40.4.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberstick BC, Boardman JD, Wagner B, Smolen A, Hewitt JK, Killeya-Jones LA, Tabor J, Halpern CT, Brummett BH, Williams RB, Siegler IC, Hopfer CJ, Mullan Harris K, 2016. Depression, stressful life events, and the impact of variation in the serotonin transporter: findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). PLoS One. 11, e0148373 10.1371/journal.pone.0148373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley CM, Pettit JW, Castellanos D, 2018. Reactive aggression and suicide-related behaviors in children and adolescents: a review and preliminary meta-analysis. Suicide Life Threat. Behav 48, 38–51. 10.1111/sltb.12325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Shen S, Lowers L, Locke-Wellman J, Matthews AG, McDermott M, 2008. Psychopathology in offspring from multiplex alcohol dependence families with and without parental alcohol dependence: a prospective study during childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry Res 160, 155–166. 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB, 1975. Four factor index of social status, New Haven, CT: Department of Sociology, Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Hu XZ, Lipsky RH, Zhu G, Akhtar LA, Taubman J, Greenberg BD, Xu K, Arnold PD, Richter MA, Kennedy JL, Murphy DL, Goldman D, 2006. Serotonin transporter promoter gain-of-function genotypes are linked to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet 78, 815–826. 10.1086/503850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janca A, Robins LN, Cottler LB, Early TS, 1992. Clinical observation of assessment using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): An analysis of the CIDI field trials - wave II at the St. Louis site. Br. J. Psychiatry 160, 815–818. 10.1192/bjp.160.6.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasiewicz A, Samochowiec A, Samochowiec J, Małecka I, Suchanecka A, Grzywacz A, 2014. Suicidal behavior and haplotypes of the dopamine receptor gene (DRD2) and ANKK1 gene polymorphisms in patients with alcohol dependence - preliminary report. PLoS One 9, e111798 10.1371/journal.pone.0111798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE, 1999. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National comorbidity sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56,617–626. 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomek AB, Sourander A, Kumpulainen K, Piha J, Tamminen T, Moilanen I, Almqvist F, Gould MS, 2008. Childhood bullying as a risk for later depression and suicidal ideation among Finnish males. J Affect Disord 109, 47–55. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligthart L, Bartels M, Hoekstra RA, Hudziak JJ, Boomsma DI, 2005. Genetic contributions to subtypes of aggression. Twin Res. Hum. Genet 8, 483–491. 10.1375/183242705774310169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins N, Bigdeli TB, Børglum AD, Coleman JRI, Demontis D, Mehta D, et al. , 2019. GWAS of suicide attempt in psychiatric disorders and association with major depression polygenic risk scores. Am. J. Psychiatry 176, 651–660. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18080957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins N, Perroud N, Uher R, Butler AW, Cohen-Woods S, Rivera M, Malki K, Euesden J, Power RA, Tansey KE, Jones L, Jones I, Craddock N, Owen MJ, Korszun A, Gill M, Mors O, Preisig M, Maier W, Rietschel M, Rice JP, Müller-Myhsok B, Binder EB, Lucae S, Ising M, Craig IW, Farmer AE, McGuffin P, Breen G, Lewis CM, 2014. Genetic relationships between suicide attempts, suicidal ideation and major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide association and polygenic scoring study. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet 165B, 428–437. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Masyn K, 2005. Discrete-time survival mixture analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat 30, 27–58. 10.3102/10769986030001027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO, 1998–2012. Mplus User’s Guide 7th ed Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Nedic G, Nikolac M, Sviglin KN, Muck-Seler D, Borovecki F, Pivac N, 2011. Association study of a functional catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) Val108/158 Met polymorphism and suicide attempts in patients with alcohol dependence. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 14, 377–388. 10.1017/S1461145710001057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, de Giorlamo G, Gluzman S, de Graaf R, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang Y, Karam E, Kessler RC, Lepine JP, Levinson D, Medina-Mora ME, Ono Y, Posada-Villa J, Williams D, 2008. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br. J. Psychiatry 192, 98–105. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC, 2010. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol. Psychiatry 15, 868–876. 10.1038/mp.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Currier D, Liu S, Hasin D, Grant B, Blanco C 2010. Increased risk for suicidal behaviors in comorbid bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorders. J Clin. Psychiatry 71:902–909. 10.4088/JCP.09m05198gry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Huang J, Purcell S, Fava M, Rush AJ, Sullivan PF, Hamilton SP, McMahon FJ, Schulze TG, Potash JB, Zandi PP, Willour VL, Penninx BW, Boomsma DI, Vogelzangs N, Middeldorp CM, Rietschel M, Nöthen M, Cichon S, Gurling H, Bass N, McQuillin A, Hamshere M, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Bipolar Disorder Group, Craddock N, Sklar P, Smoller JW, 2010. Genome-wide association study of suicide attempts in mood disorder patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 1499–1507. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss UW, Koller G, Samochowiec A, Zill P, Samochowiec J, Kucharska-Mazur J, Wong J, Soyka M, 2015. Serotonin and dopamine candidate gene variants and alcohol- and non-alcohol-related aggression. Alcohol Alcohol 50, 690–699. 10.1093/alcalc/agv057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P, 2011. The impact of psychiatric illness on suicide: differences by diagnosis of disorders and by sex and age of subjects. J. Psychiatr. Res 45, 1445–1452. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahikainen AL, Majaharju S, Haukka J, Palo JU, Sajantila A 2017. Serotonergic 5HTTLPR/rs25531 s-allele homozygosity associates with violent suicides in male citalopram users. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet 174, 691–700. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Tanner R, Berger SR, Beardslee WR, Fitzmaurice GM, 2006. Adolescent suicidal ideation as predictive of psychopathology, suicidal behavior, and compromised functioning at age 30. Am J Psychiatry, 163, 1226–1232. 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ru W, Fang P, Wang B, Yang X, Zhu X, Xue M, Shen G, Gao X, Gong P, 2017. The impacts of Val158Met in Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene on moral permissibility and empathic concern. Pers. Individ. Dif 106, 52–56. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rujescu D, Giegling I, Gietl A, Hartmann AM, Möller HJ, 2003. A functional single nucleotide polymorphism (V158M) in the COMT gene is associated with aggressive personality traits. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 34–39. 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01831-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento-Hernández EI, Ulloa-Flores RE, Camarena-Medellín B, Sanabrais-Jiménez MA, Aguilar-García A, Hernández-Muñoz S, 2019. Association between 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, suicide attempt and comorbidity in Mexican adolescents with major depressive disorder. Actas. Esp. Psiquiatr 47, 1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schosser A, Butler AW, Ising M, Perroud N, Uher R, Ng MY, Cohen-Woods S, Craddock N, Owen MJ, Korszun A, Jones L, Jones I, Gill M, Rice JP, Maier W, Mors O, Rietschel M, Lucae S, Binder EB, Preisig M, Perry J, Tozzi F, Muglia P, Aitchison KJ, Breen G, Craig IW, Farmer AE, Müller-Myhsok B, McGuffin P, Lewis CM, 2011. Genomewide association scan of suicidal thoughts and behaviour in major depression. PLoS One 6, e20690 10.1371/journal.pone.0020690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki G, Romanowicz M, Passov V, Rundell J, Mrazek D, Kung S, 2013. State dependent gene-environment interaction: serotonin transporter gene-child abuse interaction associated with suicide attempt history among depressed psychiatric inpatients. J. Affect. Disord 147, 373–378. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PK, Rao VR, 2018. Explaining suicide attempt with personality traits of aggression and impulsivity in a high risk tribal population of India. PLoS One 13, e0192969 10.1371/journal.pone.0192969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M, Donnelly P, 2003. A comparison of bayesian methods for haplotype reconstruction from population genotype data. Am. J. Hum. Genet 73, 1162–1169. 10.1086/379378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P, 2001. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am. J. Hum. Genet 68, 978–989. 10.1086/319501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SH, Hu X, Zhang JY, Qiu HM, Liu X, Jia CX, 2016. The COMT rs4680 polymorphism and suicide attempt in rural Shandong, China. Psychiatr. Genet 26, 166–171. 10.1097/YPG.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swogger MT, Van Orden KA, Conner KR, 2014. The relationship of outwardly-directed aggression to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts across two high-risk samples. Psychol. Violence 4, 184–195. 10.1037/a0033212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turecki G, 2005. Dissecting the suicide phenotype: the role of impulsive-aggressive behaviours. J. Psychiatry Neurosci 30, 398–408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland JR, Martin BJ, Kruse MR, Lesch KP, Murphy DL, 2006. Simultaneous genotyping of four functional loci of human SLC6A4, with a reappraisal of the 5-HTTLPR and rs25531. Mol. Psychiatry 11, 224–226. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox HC, Conner KR, Caine ED, et al. : 2004. Association of alcohol and drug use disorder and completed suicide: an empirical review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend 76:S11–S19. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willour VL, Seifuddin F, Mahon PB, Jancic D, Pirooznia M, Steele J, et al. , 2012. A genome-wide association study of attempted suicide. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 433–444. 10.1038/mp.2011.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2014. Preventing suicide: A global imperative Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; https://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/ (accessed 3 December 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Young KA, Bonkale WL, Holcomb LA, Hicks PB, German DC, 2008. Major depression, 5HTTLPR genotype, suicide and antidepressant influences on thalamic volume. Br. J. Psychiatry 192, 285–289. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Hu XZ, Benedek DM, Fullerton CS, Forsten RD, Naifeh JA, Li X, Biomarker Study Group., 2019. Genetic predictor of current suicidal ideation in US service members deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. J. Psychiatr. Res 113, 65–71. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]