Abstract

Background

Cardiac hypertrophic growth is mediated by robust changes in gene expression, as well as changes that underlie the increase in cardiomyocyte size. The former is regulated by RNA polymerase (pol) II de novo recruitment or loss, while the latter involves incremental increases in the transcriptional elongation activity of pol II that is preassembled at the transcription start site (TSS). The differential regulation of these distinct processes by transcription factors remains unknown. Forkhead box protein (Fox)O1 is an insulin-sensitive transcription factor, which is also regulated by hypertrophic stimuli in the heart, however, the scope of its gene regulation remains unexplored.

Methods

To address this, we performed FoxO1 chromatin immunoprecipitation-deep sequencing (ChIP-Seq) in mouse hearts following 7-day isoproterenol injections (Iso- 3 mg/kg/day), transverse aortic constriction (TAC), or vehicle injection/sham surgery.

Results

Our data demonstrate increases in FoxO1 chromatin binding during cardiac hypertrophic growth, which positively correlate with extent of hypertrophy. To assess the role of FoxO1 on pol II dynamics and gene expression, the FoxO1 ChIP-Seq results were aligned with those of pol II ChIP-Seq across the chromosomal coordinates of sham- or TAC-operated mouse hearts. This uncovered that FoxO1 binds to the promoters of 60% of cardiac-expressed genes at baseline and 91% post-TAC. Interestingly, FoxO1 binding is increased in genes regulated by pol II de novo recruitment, loss, or pause-release. In vitro, endothelin (Et-)1- and, in vivo, pressure overload, -induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophic growth is prevented with FoxO1 knockdown or deletion, which was accompanied by reductions in inducible genes, including Comtd1, in vitro, and Fstl1 and Uck2, in vivo.

Conclusions

Together, our data suggest that FoxO1 may mediate cardiac hypertrophic growth via regulation of pol II de novo recruitment and pause-release, as the latter represents the majority (59%) of FoxO1-bound, pol II regulated genes following pressure overload. These findings demonstrate the breadth of transcriptional regulation by FoxO1 during cardiac hypertrophy, information that is essential for its therapeutic targeting.

Keywords: Forkhead box protein (Fox)O1, RNA polymerase (pol)II, Transcription, Gene expression, Cardiac hypertrophy, Transverse aortic constriction (TAC), Endothelin (Et-)1, Chromatin immunoprecipitation-deep sequencing (ChIP-Seq)

INTRODUCTION

Alterations in gene expression are essential to the molecular mechanisms that drive cardiac hypertrophic growth. These include robust up or downregulation of certain genes, for example those involved in fetal gene reprogramming1. In addition to these substantial changes, there are underlying increases in the expression of the vast majority of cardiac-expressed genes that are essential to match the increase in cardiomyocyte size2. These include, for example, certain metabolic enzymes, ion channel constituents, and cell surface proteins. The distinction between these categories of genes becomes critical when designing novel therapies directed at transcriptional machinery, which is of much interest. Inhibition of general transcription factor (TF)IIB3, histone deacetylases (HDAC)4, 5, and bromodomain-containing protein (Brd)46, to name a few examples, have all proven beneficial for the attenuation of cardiac hypertrophy in mouse models. Moreover, loss of pro-hypertrophic transcription factors, such as MEF2D7, or gain of anti-hypertrophic transcription factors, such as forkhead box protein (Fox)O1 or 38, also prevent pathological hypertrophic growth. It remains important, however, to understand the scope of these transcription regulators and the mechanisms by which they target various gene subsets during physiology and pathology. This information is critical as we aim to inhibit pathological gene expression while sparing adaptive growth.

Variations in RNA polymerase (pol)II recruitment and elongation distinguish between up or downregulated genes versus incrementally increased genes during cardiac hypertrophy2. Those that are upregulated are defined as having de novo pol II recruitment to the transcription start site (TSS) and gene body. Conversely, those that are downregulated have loss of pol II in these gene regions. Those that are incrementally increased to parallel an increase in cardiomyocyte size are regulated by pol II pause-release2. Specifically, paused pol II describes preassembled pol II at the TSS under basal conditions. Upon induction of hypertrophy, this paused pol II is released into the gene body to increase transcription concurrent with growth2, 9. Pol II pausing is widespread in the heart and >50% of genes are reported to be regulated by pause-release following hypertrophy2. In general, pause-release is thought to rapidly and synchronously regulate transcription in response to various stimuli9. In fact, in D. melanogaster pause-release has been shown to drive gene expression in response to heat-shock10, 11, and in human colorectal cancer cells in response to hypoxia12. Thus, it is presumed that cardiac paused pol II will be released in response to numerous stimuli, yet the extent, loci specificity, and functionality have yet to be determined. Moreover, the signals that differentially drive pol II de novo recruitment, loss, and pause-release, especially in the heart during physiological and pathophysiological growth, remain unclear. Again, understanding these differences is central for novel transcriptional therapeutic strategies.

As mentioned above, FoxO1 is a transcription factor that has been shown to be anti-hypertrophic, largely via its activation of atrophic genes such as Fbxo32. Acute stimulation with hypertrophic agonists yields FoxO1 nuclear export, preventing Fbxo32 transcription and leading to a hypertrophic phenotype in cardiomyocytes8, 13. Fbxo32 encodes atrogin-1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which has also been shown to target and inhibit calcineurin and, therefore, downstream hypertrophic NFAT activity. Thus, its loss stabilizes calcineurin/NFAT signaling and hypertrophy8. Additionally, FoxO1 overexpression prevented angiotensin II-mediated cardiomyocyte hypertrophy8. Accordingly, FoxO1 has been proposed as a therapeutic target for hypertrophic cardiomyopathies. Importantly, however, the localization and function of FoxO1 following more chronic hypertrophic stress, with desensitization of the receptors that mediate its upstream signaling, is unknown. Further, the scope and patterns of FoxO1 binding during basal and hypertrophic conditions are also unknown. Addressing these gaps in knowledge is critical for targeting transcriptions factors, such as FoxO1. Thus, they were the focus of our study.

Through genome-wide analyses, we uncovered the widespread binding of FoxO1 and its indiscrimination with regard to differential pol II regulation during cardiac hypertrophy. This work is noteworthy as it challenges the notion of FoxO1 as a desirable therapeutic target under these conditions. Consistently, it underscores the value of understanding the scope and mechanistic effects of other transcription factors and machinery for their therapeutic targeting.

METHODS

The methods and materials used for completion of these studies, as well as the data generated, will be made available to researchers seeking to replicate the procedures or results. The raw and unprocessed FoxO1 ChIP-Seq data have been deposited into GEO (GSE144011). All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Temple University. Detailed methods can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Statistical Analyses.

Significant differences between the means of two sample groups were calculated using t-test (equal variance, two-tailed), while 1- or 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post-hoc testing was used for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

FoxO1 chromatin binding positively correlates with cardiac hypertrophy.

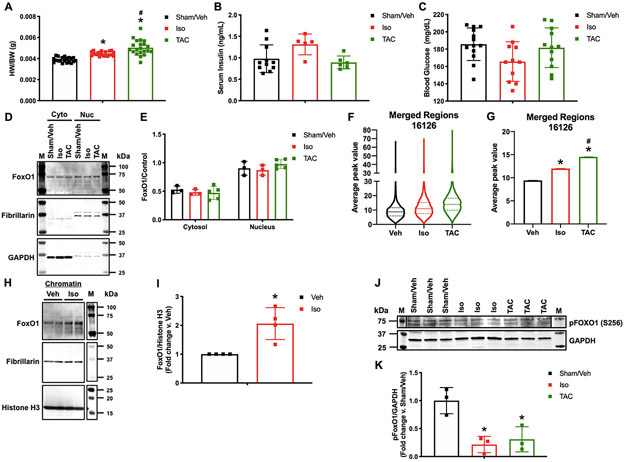

To begin to understand the role of FoxO1 in cardiac hypertrophy, we examined its nuclear localization and binding to the cardiac genome. For this, we subjected wild type C57Bl/6 mice to sham operation and vehicle injections, isoproterenol injections (3 mg/kg/day), or transverse aortic constriction (TAC) over 7 days. Isoproterenol-treated and TAC hearts were hypertrophic at 7 days, as indicated by a significant increase in heart weight-to-body weight ratios (HW/BW) (15.9 and 25.4%, respectively) (Figure 1A). Importantly, however, there were no significant differences in cardiac function, as determined by echocardiographic analyses of ejection fraction and fractional shortening, between any of the tested groups (Figure IA-B in the Supplement). Success and consistency of TAC were confirmed by significant increases in aortic mean (2.8-fold) and peak (11.4-fold) pressure gradients versus sham-operated mice (Figure IC in the Supplement). Moreover, there were no significant differences in serum insulin or blood glucose levels (Figure 1B-C). Subcellular fractionation and Western blotting was then performed and no significant difference in nuclear or cytosolic FoxO1 was observed in any of the tested groups (Figure 1D-E). As a positive control for nuclear-to-cytosolic shuttling, mouse hearts were fractionated and Western blotting for FoxO1 was performed following 1 hour vehicle or insulin (1 unit/kg) stimulation (Figure IIA in the Supplement). To examine FoxO1 genomic binding, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-Seq) for FoxO1 in murine hearts 7 days after sham operation/vehicle treatment, isoproterenol treatment, or TAC. Interestingly, the data reveal an increase in the total amount of FoxO1 binding across the genome (total sequence tags) in hearts following isoproterenol treatment (52.4%) or TAC (56.5%). Importantly, however, there are decreases in the total number of FoxO1-bound regions (filtered peaks or merged regions) following isoproterenol treatment (27.7 or 26.6%, respectively) or TAC (6.5 or 8.3%, respectively), suggesting a rearrangement and enrichment of chromatin-bound FoxO1 peaks under these conditions (Table I in the Supplement). We, next, examined the extent of FoxO1 binding at these FoxO1-bound regions (merged regions), and observed an increase in the median average peak value at these sites with isoproterenol (20.8%) or TAC (37.6%) versus sham/vehicle control hearts (Figure 1F). This corresponded to significant increases in the mean of the average peak values at these sites with isoproterenol (21.5%) or TAC (35.2%) versus sham/vehicle control (Figure 1G). Notably, the extent of binding positively correlates with HW/BW. This increase in FoxO1 binding was confirmed in chromatin fractions from neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (NRVM) with adenoviral expression of FoxO1 and treatment with vehicle or isoproterenol (10 μM) at 0 and 24 hours (h), with collection at 48 h (Figure 1H-I). Consistently, we observed reductions in FoxO1 phosphorylation at serine (S)256 in murine hearts following isoproterenol treatment (78.6%) or TAC (69.2%) (Figure 1J-K). Phosphorylation of FoxO1 at S256 has been shown to reduce its DNA-binding affinity14. Together, these data demonstrate that while there is no detectable nuclear-to-cytosolic shuttling of FoxO1 under hypertrophic conditions, there are alterations in its chromatin binding. Specifically, an increase in FoxO1 binding correlates with increased cardiac hypertrophic growth.

Figure 1. FoxO1 chromatin binding positively correlates with cardiac hypertrophy.

Adult (12-week-old), male C57Bl/6 mice were treated with isoproterenol (Iso) (3 mg/kg/day) or subjected to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) surgery for 7 days. Controls were sham operated and injected with vehicle (Sham/Veh) for 7 days. A Hearts were harvested and weighed. Heart weights (HW) were normalized to body weights (BW) and plotted as a ratio (HW/BW) in grams (g). n=20, 20, 21 (Sham, Iso, TAC). B Serum insulin levels were assessed using ELISA for mouse insulin. Concentrations are plotted as ng/mL. n=7, 7, 4 (Sham, Iso, TAC). C Blood glucose levels were assessed using glucose meter. Concentrations are plotted as mg/dL. n=13, 11, 12 (Sham, Iso, TAC). D-E Hearts were harvested, lysed, and the cytosolic (Cyto) or nuclear (Nuc) fractions extracted. Lysates were subjected to Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Signals from the different proteins were quantified using densitometry, normalized to loading controls (GAPDH or Fibrillarin for cytosolic or nuclear fractions, respectively) and plotted. n=3, 3, 5 (Sham, Iso, TAC). F-G 5 hearts per group (Sham/Veh, Iso, TAC) were pooled, fixed, processed for chromatin extraction, and subjected to forkhead box protein (Fox)O1 ChIP-Seq. Average peak values were plotted for all merged regions and represented as violin plots showing the median, quartiles, and distribution (F) or as bar graphs representing the mean (G). H-I NRVM were cultured, infected with Ad.FoxO1 (MOI=1), and treated with 10 μM Iso or Veh control at 0 and 24 h. Chromatin fractions were extracted at 48 h and subjected to Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Signals from the different proteins were quantified using densitometry and FoxO1 was normalized to histone H3 and plotted as fold change versus Veh. n=4, 4 (Veh, Iso). J-K Hearts were harvested, lysed, and subjected to Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Signals from the different proteins were quantified using densitometry, normalized to the GAPDH loading control and plotted. n=3, 3, 3 (Sham, Iso, TAC). Error bars represent SEM. *p<0.05 Iso or TAC versus Sham/Veh and #p<0.05 TAC versus Iso using 1-way ANOVA. *p<0.05 Iso versus Veh using t-test. M=marker.

FoxO1 is primarily detected at the TSS of genes.

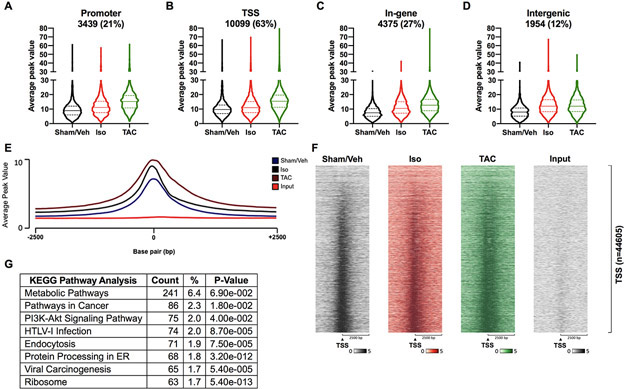

In addition to the extent of FoxO1 binding, the ChIP-Seq results provide spatial data for its binding. For the first time, we demonstrate that FoxO1 binding is widespread, as peaks were observed in promoter (−1000 to −10,000 base pairs (bp) relative to the TSS), TSS (−1000 to +1000 bp relative to the TSS), in-gene, and intergenic regions. Importantly, 63% of FoxO1-bound regions were at TSS, versus 21, 27, and 12% for promoter, in-gene, and intergenic regions, respectively (Figure 2A-D). Moreover, there were increases in the median and mean average peak value in isoproterenol or TAC groups versus sham/vehicle controls in each genomic region (Figure 2A-D and Figure IIIA-D in the Supplement). It is important to note that while there was an overall increase in FoxO1 binding with cardiac hypertrophy, there were subsets of genes with decreased binding following isoproterenol treatment or TAC in each genomic region (Figure IV-V and VI-VII in the Supplement, respectively). These subsets, however, represent small fractions (12, 16, 11, and 9% in promoter, TSS, in-gene, and intergenic regions, respectively) of the total amount of FoxO1 bound to each region for isoproterenol-treated hearts. This compares to 50, 40, 60, and 64%, which have increased FoxO1 binding, respectively (Figure IV and V in the Supplement). Following TAC, there is a greater disproportion between those genes with decreased (6, 6, 7, and 11%, respectively) versus increased (74, 69, 71, and 63%, respectively) FoxO1 binding (Figure VI and VII in the Supplement). When specifically examining the TSS-containing region, which had the highest percentage of FoxO1 binding, it was evident that the majority of binding occurred at the TSS (Figure 2E-F). TSS binding of FoxO1 also increased with isoproterenol treatment or TAC, and positively correlated with HW/BW (Figure 2E-F). KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were also performed for genes with TSS-bound FoxO1 and showed that genes involved metabolism were the most highly represented (Figure 2G and Table II in the Supplement). Additionally, to confirm the specificity of FoxO1 binding during hypertrophy, genes with increased binding following isoproterenol treatment or TAC were compared and show significant overlap. Specifically, 76.7, 82.7, and 52% of genes with increased FoxO1 binding following isoproterenol treatment are shared with those following TAC in promoter, TSS, and in-gene regions, respectively (Figure VIII in the Supplement). Moreover, pathway analyses of these overlapping genes with TSS-bound FoxO1 reveals metabolic pathways as the most highly represented term (Table III in the Supplement). Overall, these data demonstrate that FoxO1 is primarily detected at the TSS of genes, where it increases with cardiac hypertrophy.

Figure 2. FoxO1 is primarily detected at transcription start sites of genes.

Forkhead box protein (Fox)O1 ChIP-Seq was performed as described in Figure 1. A-D FoxO1-bound merged regions were sorted by genomic region. Promoter represents −1000 to −10000 bp relative to the transcription start site (TSS). TSS represents −1000 to +1000 bp relative to the TSS. Intergenic represents those no represented in the promoter, TSS, or In-gene. Average peak values were plotted and represented as violin plots showing the median, quartiles, and distribution. Percentages represent the fraction of FoxO1 bound to a particular genomic region relative to all of the FoxO1-bound merged regions (16126). Merged regions can be present in one or more genomic regions. E Average peak values (y-axis) were plotted versus sequencing tags across the TSS (−2500 bp to +2500 bp relative to the TSS) (x-axis) (EaSeq software). F Sequencing tags distribution (y-axis) across the TSS (−2500 bp to +2500 bp relative to the TSS) (x-axis) are represented as heatmaps. G KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed using The Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) for the merged regions containing FoxO1 at the TSS (B), for Sham/Vehicle (Veh), isoproterenol (Iso), and transverse aortic constriction (TAC). Shown are the top 8 most highly represented pathways. PI3K=Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; HTLV-1=Human T-cell leukemia virus 1.

To further understand the nature of FoxO1 binding in our ChIP-Seq studies, motif analyses were performed for the promoter, TSS, in-gene, and intergenic regions in our sham/vehicle, isoproterenol, or TAC datasets. The results reveal the discovery of Fox motifs within the top two identified de novo motifs in the promoter, in-gene, and intergenic regions of the sham/vehicle, isoproterenol, and TAC datasets. No Fox motifs were identified, however, at the TSS of any of these groups (Table 1). These data suggest direct binding of FoxO1 at the promoter, in-gene, and intergenic regions, and indirect binding at the TSS. This is not surprising as eukaryotic transcription factors are known to bind distal enhancers and, via multi-protein complexes, loop to the TSS to regulate pol II and gene transcription15-17. Genome-wide de novo motif analyses were also performed in the sham/vehicle, isoproterenol, and TAC datasets and the results are represented as sequence logos (Table IV in the Supplement).

Table 1. Motif identification in the FoxO1 ChIP-Seq data.

Forkhead box protein (Fox)O1 ChIP-Seq was performed as described in Figure 1. Sequences from the promoter, transcription start site (TSS), in-gene, and intergenic regions were used as input for identification of de novo motifs. The top three identified motifs are listed for each region for Sham/Vehicle (Veh), Isoproterenol (Iso), or Transverse aortic constriction (TAC). Also listed are the predicted binding proteins for each motif (Best Guess), the percentage of targets containing the listed motif (% Targets), the percentage of background sequences containing the listed motif (% Background), and the P-value.

| Motif | Best Guess | % Targets | % Background | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham/Veh | Promoter | ACTACAAHTCCC | GFY | 14.84 | 0.81 | 1.00E-130 |

| TTGTTTAC | FOXO3 | 10.87 | 1.97 | 1.00E-44 | ||

| HCAHTTCCGGYY | FLI1 | 35.06 | 17.64 | 1.00E-38 | ||

| TSS | GGGADTTGTAGT | GFY | 47.29 | 0.95 | 1e-658 | |

| TTCCCAGAATGC | ZNF143 | 23.35 | 1.37 | 1.00E-205 | ||

| TGCCGGAA | ELK1 | 49 | 25.28 | 1.00E-57 | ||

| In-gene | NBTGTTTACN | FOXO4 | 22.55 | 2.71 | 1.00E-129 | |

| ACAGGAARYS | ERG | 31.73 | 9.97 | 1.00E-77 | ||

| ACTACAATTCCC | GFY | 3.98 | 0.32 | 1.00E-28 | ||

| Intergenic | ACTACAATTCCC | GFY | 19.98 | 0.83 | 1.00E-200 | |

| HGTAAACA | FOXI1 | 14.13 | 1.47 | 1.00E-88 | ||

| SABTTCCGGY | FLI1 | 48.74 | 25.23 | 1.00E-56 | ||

| Iso | Promoter | ACTACAAYTCCC | GFY | 16.6 | 0.8 | 1.00E-153 |

| GTAAACAA | FOXO3 | 19.47 | 5.12 | 1.00E-55 | ||

| RRCCGGAAGT | ETV1 | 33.5 | 14.3 | 1.00E-50 | ||

| TSS | GGGANTTGTAGT | GFY | 53.96 | 1.14 | 1e-749 | |

| TTCTGGGAAATG | STAT5A/B | 23.67 | 1.36 | 1.00E-209 | ||

| GGCATTCTGG | ZNF143 | 41.83 | 10.02 | 1.00E-150 | ||

| In-gene | DGTAAACA | FOXO4 | 34.33 | 6 | 1.00E-154 | |

| ACTTCCTGTY | ETS1 | 39.36 | 10.53 | 1.00E-121 | ||

| VBAACAATRG | SOX9 | 19.01 | 6.82 | 1.00E-35 | ||

| Intergenic | ACTACAAYTCCC | GFY | 21.36 | 0.74 | 1.00E-227 | |

| TGTTTACD | FOXI1 | 22.48 | 3.31 | 1.00E-111 | ||

| CCGGAAGT | ETS | 48.97 | 20.49 | 1.00E-86 | ||

| TAC | Promoter | ACTACAATTCCC | GFY | 12.01 | 0.76 | 1.00E-98 |

| TGTAAACARG | FOXO1 | 9.28 | 1.73 | 1.00E-37 | ||

| CTTCCGGT | ETS | 48.44 | 30.95 | 1.00E-29 | ||

| TSS | GGGANTTGTAGT | GFY | 39.14 | 1.34 | 1e-446 | |

| TTCCCAGMATGC | ZNF143 | 15.82 | 0.98 | 1.00E-133 | ||

| TCSCGTAA | CEBPD | 66.87 | 39.01 | 1.00E-70 | ||

| In-gene | GTAAACAVVN | FOXO4 | 24.29 | 4.35 | 1.00E-103 | |

| ACTTCCTG | ERG | 44.59 | 20.32 | 1.00E-64 | ||

| AACAACAACA | FOXK1 | 16.33 | 7.45 | 1.00E-19 | ||

| Intergenic | ACTACAATTCCC | GFY | 16.38 | 0.83 | 1.00E-150 | |

| GTAAACAVCN | FOXO6 | 16.68 | 3.05 | 1.00E-68 | ||

| NACCGGAAGT | FLI1 | 41.35 | 17.69 | 1.00E-66 | ||

FoxO1 aligns with pol II at the TSS of genes.

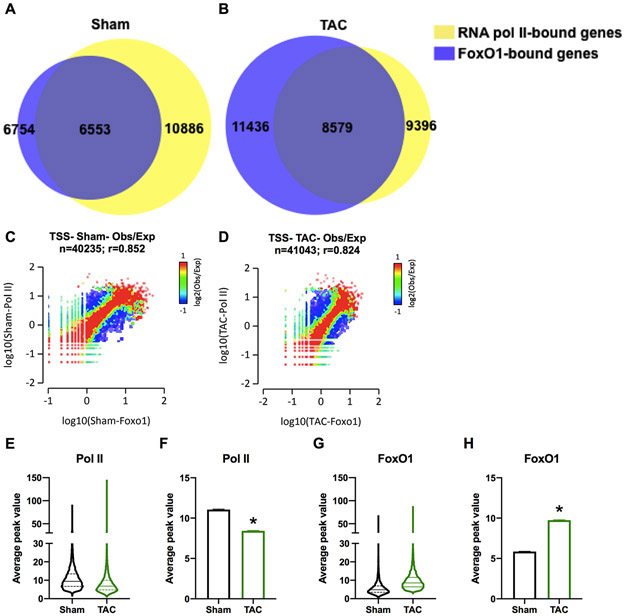

Since FoxO1 is primarily detected at the TSS of genes, we aimed to assess its role in the regulation of pol II dynamics and gene expression. We, therefore, aligned our FoxO1 ChIP-Seq data with pol II ChIP-Seq data from murine hearts following sham-operation or TAC for 7 days (GEO: GSE50637). The data demonstrate significant overlap between FoxO1 and pol II binding at the TSS of genes following sham-operation or TAC. Specifically, 97% and 75% of FoxO1-bound genes contain pol II, in this region, post-sham and –TAC, respectively (Figure 3A-B). Additionally, pathway analyses of the overlapping genes show that those of the metabolic pathways were most represented (Table V and VI in the Supplement). Overlap between FoxO1 and pol II bound to the TSS of genes was also observed at correlation coefficients for observed over expected (Obs/Exp) values, r=0.852 and 0.824 in sham and TAC, respectively (Figure 3C-D). In contrast, promoter-distal and in-gene regions showed correlation coefficients for FoxO1 versus pol II that were relatively lower, r=0.500, 0.525, 0.525, 0.554 for promoter sham, promoter TAC, in-gene sham, and in-gene TAC, respectively (Figure IXA-D in the Supplement). Notably, while there is an overall increase in FoxO1 binding at the TSS during TAC, there is an overall decrease in pol II binding in this region during hypertrophic growth (Figure 3E-H). Furthermore, these data not only demonstrate the overlap between FoxO1 and pol II at the TSS, but also the extensiveness of FoxO1 binding. From Figure 3A-B, we calculate that 60.2% of cardiac-expressed genes contain FoxO1 at the TSS at baseline, a figure that increases to 91.3% post-TAC. Thus, the data show that FoxO1 binding is widespread and aligns with pol II at the TSS of genes.

Figure 3. FoxO1 aligns with pol II at the TSS.

Forkhead box protein (Fox)O1 and RNA polymerase (pol)II ChIP-Seq were performed in Sham and transverse aortic constriction (TAC) hearts as described in Figure 1. A-B Venn diagrams demonstrate the overlap between FoxO1- (blue) and pol II-bound (yellow) merged regions in Sham (A) and TAC (B) at the transcription start site (TSS). C-D 2-dimensional (2D) histograms showing the distribution of fragments calculated from their overall frequencies in the ChIP-Seq of FoxO1 (x-axis) versus Pol II (y-axis), surrounding the TSS (−2000 to +2000 bp). The x- and y-axes were segmented into 75 bins, and the number of fragments within each bin was counted, color coded, and plotted. The bar to the right of the plot illustrates the relationship between count and coloring. The plots represent pseudo-colored 2D matrices showing observed/expected distribution, calculated from the overall frequencies of fragments on each of the axes. This plot shows the relation between FoxO1 and Pol II, relative to what is expected if they occurred by chance. The pseudo-color corresponds to the observed-to-expected ratio (Obs/Exp), and the color intensity is proportional to the log10 of the number of observed fragments within each bin. These plots suggest that there is a positive correlation between the binding of those 2 molecules, where the red indicates that this occurs more frequently than expected by chance, as denoted by the correlation coefficient listed above the histogram. These figures were generated using EaSeq software. E-H Average peak values for all merged regions of expressed genes (pol II sequencing tags > 35 in Sham or TAC at the TSS) containing FoxO1 (FoxO1 sequencing tags > 35 in Sham or TAC at the TSS) were plotted for pol II (E) or FoxO1 (F) at the TSS during Sham or TAC. The data are represented as violin plots showing the median, quartiles, and distribution (E and G) or as bar graphs representing the mean (F and H). Error bars represent SEM. *p<0.05 TAC versus Sham using t-test.

FoxO1 binding is increased at the TSS in all subsets of genes regulated by pol II during cardiac hypertrophy.

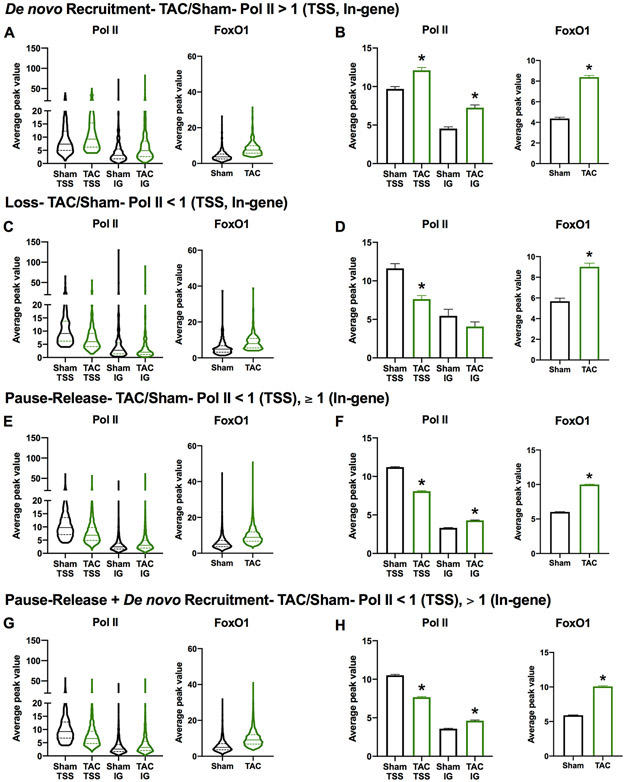

To continue investigating the role of TSS-bound FoxO1 in regulating pol II dynamics and gene expression, we examined FoxO1 binding in distinct subsets of genes regulated by pol II. Genes that are characterized by de novo pol II recruitment were defined as having an increase in pol II at the TSS and in-gene regions (>1) following TAC (Figure 4A-B). De novo pol II recruitment is associated with an upregulation of gene expression under these conditions2. Conversely, genes that are characterized by pol II loss have reduced pol II at the TSS and in-gene regions (<1) following TAC (Figure 4C-D). Pol II loss is associated with downregulation of gene expression under these conditions2. These two subsets of genes (upregulated and downregulated), however, only represent 5.94 and 2.22% of genes regulated during cardiac hypertrophic growth. The majority of genes (55.76%) are regulated by pol II pause-release with another group (23.54%) being regulated by a combination of pol II de novo recruitment and pause-release (Table 2). Pol II pause-release genes are defined by reduced pol II at the TSS (<1) and unchanged or increased pol II at in-gene regions (≥1) following TAC (Figure 4E-F). Pol II pause-release is associated with incremental increases in transcription and gene expression that match an increase in cardiomyocyte size2. Finally, the gene subset that is defined by pol II de novo recruitment and pause-release is characterized by an decrease in pol II at the TSS (<1) and an increase in pol II in the in-gene region (>1) following TAC (Figure 4G-H). This category is associated with an upregulation of gene expression under these conditions2. When we examined overall FoxO1 binding in each of these gene subsets, it was significantly increased (Figure 4A-H). Interestingly, however, a larger percentage of genes regulated by pol II pause-release or de novo recruitment plus pause-release contain FoxO1 (95.51 and 95.87%, respectively) versus de novo recruitment or pol II loss (79.28 and 71.89%, respectively) (Table 2). It should also be noted that the majority of genes in any group have increased FoxO1 binding (78.23, 69.48, 93.55, and 94.24% for pol II de novo recruitment, loss, pause-release, or de novo recruitment+pause-release, respectively) versus decreased (11.26, 2.41, 1.9, and 1.55% for pol II de novo recruitment, loss, pause-release, or de novo recruitment+pause-release, respectively) (Table 2). Overall, these data reveal that FoxO1 binding increases in all subsets of pol II-regulated genes during cardiac hypertrophy. This suggests that FoxO1 is not a defining factor for these gene categories, but may play a role in the regulation of each subset.

Figure 4. FoxO1 is increased at the TSS in all subsets of genes regulated by pol II during cardiac hypertrophy.

A-H Forkhead box protein (Fox)O1 and RNA polymerase (pol)II ChIP-Seq were performed in Sham and transverse aortic constriction (TAC) hearts as described in Figure 1. Average peak values for all merged regions of expressed genes (pol II sequencing tags > 35 in Sham or TAC at the transcription start site (TSS)) containing FoxO1 (FoxO1 sequencing tags > 35 in Sham or TAC at the TSS) were plotted for pol II (left panels) at the TSS or in-gene (IG) regions, or FoxO1 (right panels) at the TSS during Sham or TAC. The data are represented as violin plots showing the median, quartiles, and distribution (A, C, E, and G) or as bar graphs representing the mean (B, D, F, and H). Groups were defined as indicated. Error bars represent SEM. *p<0.05 TAC versus Sham using t-test.

Table 2. Pol II-regulated gene subsets during cardiac hypertrophy.

Gene subsets representing pol II de novo recruitment (TAC/Sham- pol II > 1 (TSS, in-gene)), loss (TAC/Sham- pol II < 1 (TSS, in-gene)), pause-release (TAC/Sham- pol II < 1 (TSS) and ≥ 1 (in-gene)), and pause-release + de novo recruitment (TAC/Sham- pol II < 1 (TSS) and > 1 (in-gene)) are reported as numbers of genes per group (# of genes/group) or a percentage (% of total) of the overall expressed genes (pol II tags > 35 at TSS in Sham or TAC) (11213 genes). The number of genes that bind forkhead box protein (Fox)O1 (FoxO1 tags > 35 at TSS in Sham or TAC) for each group is also reported (# of genes/group (FoxO1 binding)) and displayed as percentages (%). 35 was selected as a stringent cutoff as input DNA tags averaged 31 and 9 at the TSS in the pol II and FoxO1 ChIP-Seq datasets, respectively. Of these FoxO1-bound genes, the number of genes per group with increased (TAC/Sham- FoxO1 > 1) or decreased (TAC/Sham- FoxO1 < 1) FoxO1 binding following TAC (# of genes/group (FoxO1 increased) or # of genes/group (FoxO1 decreased), respectively) was also reported and displayed with their respective percentages (%).

| # of genes/group |

% of Total (11213 genes) |

# of genes/group (FoxO1 binding) |

% | # of genes/group (FoxO1 increased) |

% | # of genes/group (FoxO1 decreased) |

% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De novo Recruitment | 666 | 5.94 | 528 | 79.28 | 521 | 78.23 | 75 | 11.26 |

| Loss | 249 | 2.22 | 179 | 71.89 | 173 | 69.48 | 6 | 2.41 |

| Pause-Release | 6252 | 55.76 | 5971 | 95.51 | 5849 | 93.55 | 119 | 1.90 |

| Pause-Release + De novo Recruitment | 2639 | 23.54 | 2530 | 95.87 | 2487 | 94.24 | 41 | 1.55 |

FoxO1 knockdown prevents hypertrophic gene expression and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro.

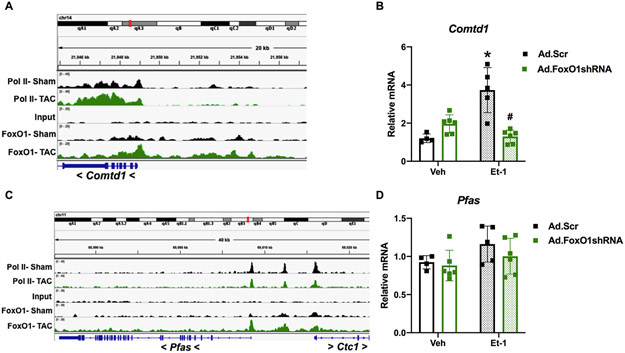

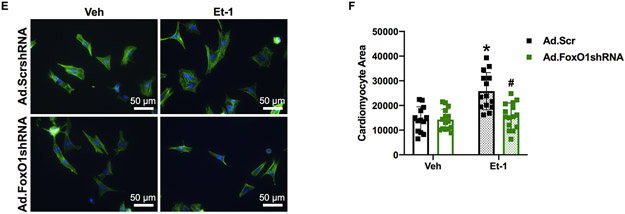

Next, we evaluated the role of FoxO1 in hypertrophic gene expression. We began by examining the groups of genes regulated by pol II de novo recruitment and pause-release, as these represent the largest percentages pol II-regulated genes during hypertrophy (Table 2). Shown in Figure 5A is a representative gene, regulated by both pol II de novo recruitment and pause-release, as defined above. Catechol-O-methyltransferase domain containing (Comtd)1 is a putative catechol-O-methyltransferase, which belongs to a family of enzymes that catalyze catecholamine degradation and are, therefore, critical in opposing catecholamine-induced stress18. Comtd1 has increased FoxO1 binding at the TSS, upstream, and in-gene regions following TAC (Figure 5A). We evaluated the expression of this gene in NRVM treated with endothelin (Et-)1 for 48 h. Et-1 is a prototypical hypertrophic agonist previously implicated in pathological cardiac growth19. As expected, we observed an increase (3.1-fold) in Comtd1 mRNA levels with Et-1 treatment, which was prevented with pretreatment of cells with adenovirus expressing short hairpin (sh)RNA against FoxO1 (Figure 5B). Similarly, we examined the expression of phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase (Pfas), a gene involved in de novo purine biosynthesis20 and regulated by pol II pause-release, as defined above. Pfas also has increased FoxO1 binding at the TSS, upstream, and in-gene regions following TAC (Figure 5C). As expected, there were no significant changes in Pfas mRNA levels with Et-1 treatment or FoxO1 shRNA expression (Figure 5D). Again, this is due to the fact that genes regulated by pol II pause-release have an increase in expression that matches an increase in cardiomyocyte size2. Thus, there are no apparent differences in expression via techniques that normalize to cellular size, such as quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Finally, we evaluated the role of FoxO1 in Et-1-induced hypertrophy in NRVM. As expected, Et-1 treatment for 24 hours increased cardiomyocyte size, an effect that is prevented with adenoviral expression of FoxO1 shRNA (Figure 5E-F). Together, these data suggest that FoxO1 may play a positive role in the regulation of pol II de novo recruitment and pause-release, and, therefore, is critical in cardiomyocyte hypertrophic growth.

Figure 5. FoxO1 knockdown prevents hypertrophic gene expression and cardiomyocyte hypertophy in vitro.

A-D Forkhead box protein (Fox)O1 and RNA polymerase (pol)II ChIP-Seq were performed in Sham and transverse aortic constriction (TAC) hearts as described in Figure 1. A and C Integrated Genomics Viewer (IGV) software was used to view the fragment densities of pol II and FoxO1 (y-axis) aligned along the gene coordinates (x-axis). Shown are exemplary images for the indicated genes. B and D-F NRVM were treated with vehicle (Veh) or 100 nM endothelin (Et)-1 and/or Ad.FoxO1shRNA or scrambled (Scr) control at an MOI of 10 for 48 h. B and D Total RNA was extracted and qPCR was performed for the indicated genes. The results were plotted. n=4, 5, 6, 6 (Veh, Et-1, Ad.FoxO1shRNA, Ad.FoxO1shRNA+Et-1). E-F Cells were fixed and stained with 488 phalloidin (FITC) and DAPI. Representative images are shown in E. Cell area was quantified using ImageJ software and plotted (F). Cardiomyocytes imaged=13, 14, 15, 15 (Veh/Ad.Scr, Veh/Ad.FoxO1shRNA, Et-1/Ad.Scr, Et-1/Ad.FoxO1shRNA). Error bars represent SEM. *p<0.05 versus Veh/Ad.Scr and #p<0.05 versus Et-1/Ad.Scr using 2-way ANOVA. Ad=adenovirus; shRNA=Short hairpin RNA; Comtd1=Catechol-O-methyltransferase domain containing 1; Pfas=Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase.

FoxO1 knockdown prevents hypertrophic gene expression and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vivo.

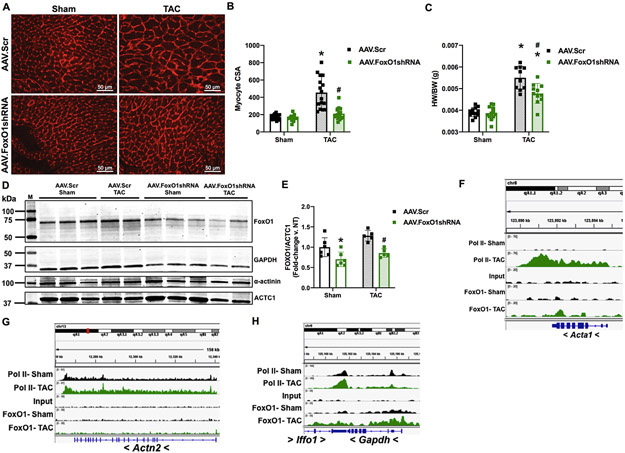

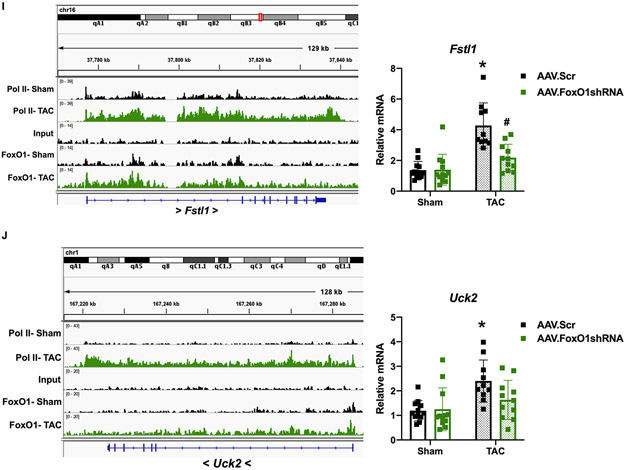

Similar to what we observed in vitro, we show here that FoxO1 knockdown prevents pressure overload-mediated cardiac hypertrophic growth in vivo. Pretreatment of mice with adeno-associated virus (AAV)9-expressing shRNA against FoxO1 (AAV.shFoxO1) normalized TAC-induced increases cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area (CsA) (Figure 6A-B), and partially prevented increases in HW/BW (Figure 6C), versus scrambled control-expressing AAV9 (AAV.Scr). Importantly, there are no significant changes in cardiac FoxO1 expression levels post-TAC in AAV.Scr-treated control mice, and extent of its knockdown is similar in AAV.shFoxO1-treated, sham or TAC-operated mice (29.8 and 33.3%, respectively) (Figure 6D-E). Quantitation of FoxO1 proteins levels is normalized to cardiac α-actin (ACTC1), which does not bind appreciable amounts of FoxO1 (Figure 6F) and, accordingly, is not reduced with FoxO1 knockdown (Figure 6D). Similarly, α-actin lacks detectable FoxO1 binding (Figure 6G) and is not altered with FoxO1 knockdown (Figure 6D). Conversely, Gapdh, which has considerable amounts of FoxO1 binding (Figure 6H), is decreased following FoxO1 knockdown (Figure 6D). Notably, following 2 (Figure XA-B in the Supplement) or 9 (Figure XC-D in the Supplement) days of AAV.Scr or AAV.shFoxO1 treatment, we do not observe any differences in cardiac function, as assessed by EF or FS. As shown above, we do not observe changes in cardiac function following one week of TAC versus sham-operated controls (Figure IA-B and XC-D in the Supplement), and this is also not altered with AAV.Scr or AAV.shFoxO1 treatment (Figure XC-D in the Supplement). Moreover, aortic mean and peak pressure gradients were similar in sham-operated mice, and equally increased post-TAC, between AAV.Scr (21.7-fold and 20.0-fold increased, respectively) and AAV.shFoxO1 (26.3-fold and 26.8-fold increased, respectively) -treated groups (Figure XE-F in the Supplement). A table with all major echocardiographic parameters including heart rate, systolic and diastolic diameter, left ventricular (LV) mass, systolic and diastolic LV anterior wall (LVAW) thickness, and systolic and diastolic LV posterior wall (LVPW) thicknesses is also included (Figure XG in the Supplement).

Figure 6. FoxO1 knockdown prevents hypertrophic gene expression and cardiomyocyte hypertophy in vivo.

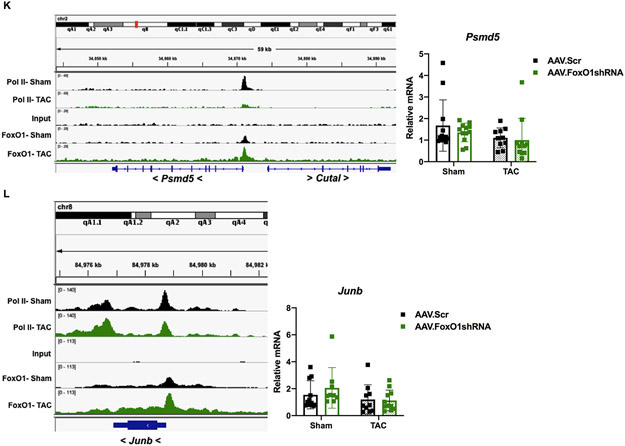

A-E, I-L Adult (12-week-old), male mice were injected with adeno-associated virus (AAV).Scr or AAV.FoxO1shRNA (1x1012 GC/mL) for two days and then subjected to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) or sham surgery for 7 days. A-B Hearts were harvested, fixed, and stained with 594 WGA. Representative images are shown in A. Cell cross-sectional area (CSA) was quantified using ImageJ software and plotted (B). Cardiomyocytes imaged= 16, 16, 16, 16 (Sham/AAV.Scr, Sham/AAV.FoxO1shRNA, TAC/AAV.Scr, TAC/AAV.FoxO1shRNA). C Hearts were harvested and weighed. Heart weights (HW) were normalized to body weights (BW) and plotted as a ratio (HW/BW) in grams. n=12, 12, 10, 11 (Sham/AAV.Scr, Sham/AAV.FoxO1shRNA, TAC/AAV.Scr, TAC/AAV.FoxO1shRNA). D-E Hearts were harvested, lysed, and subjected to Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Signals for forkhead box protein (Fox)O1 were quantified using densitometry, normalized to the cardiac alpha-actin (ACTC1) loading control, and plotted. n=6, 6, 5, 5 (Sham/AAV.Scr, Sham/AAV.FoxO1shRNA, TAC/AAV.Scr, TAC/AAV.FoxO1shRNA). F-L FoxO1 and RNA polymerase (pol)II ChIP-Seq were performed in Sham and TAC hearts as described in Figure 1. IGV software was used to view the fragment densities of pol II and FoxO1 (y-axis) aligned along the gene coordinates (x-axis). Shown are exemplary images for the indicated genes. I-L Hearts were harvested, total RNA was extracted, and qPCR was performed for the indicated genes. The results were plotted (Right panels). n=12, 12, 10, 11 (Fstl1, Uck2, Psmd5) and n=11, 9, 10, 11 (Junb) (Sham/AAV.Scr, Sham/AAV.FoxO1shRNA, TAC/AAV.Scr, TAC/AAV.FoxO1shRNA). Error bars represent SEM. *p<0.05 versus Sham/AAV.Scr and #p<0.05 versus TAC/AAV.Scr using 2-way ANOVA. M=marker; Scr=Scrambled; shRNA=Short hairpin RNA; NT=Non-treated; Acta1=Actin alpha 1; Actn2=Actinin alpha 2; Fstl1=Follistatin-related protein 1; Uck2=Uridine-cytidine kinase 2.

To examine the role of FoxO1 in the expression of pol II de novo recruitment- and pause-release-regulated genes in vivo, we measured their mRNA levels in murine hearts following TAC, with or without FoxO1 knockdown. Follistatin-related protein (FSTL)1 is a cardiac-secreted glycoprotein that is increased in cardiomyocytes following TAC, where it prevents hypertrophic remodeling and subsequent failure21. Uridine-cytidine kinase (UCK)2 is the enzyme that catalyzes the rate-limiting step of the pyrimidine-nucleotide biosynthetic salvage pathway22. Both Fstl1 and Uck2 are regulated by pol II de novo recruitment following TAC, as observed by increase in pol II binding, as described above (Figure 6I-J). These genes also have increased FoxO1 binding at their TSS and throughout their gene bodies (Figure 6I-J). As expected, this correlated with an increase in cardiac Fstl1 and Uck2 mRNA expression post-TAC (3.1- and 2.0-fold, respectively) that was normalized with FoxO1 knockdown (Figure 6I-J). As negative controls, we measured the expression of genes that are regulated by pol II de novo recruitment during TAC, but that do not bind considerable amounts of FoxO1, such as natriuretic peptide A (Nppa) and actin alpha (Acta)1 (Figure XIA-B in the Supplement). As expected, there in an increase in the expression of these genes post-TAC (7.1 and 7.9-fold, respectively), which are not normalized with FoxO1 knockdown. There is, however, a reduction in their expression, albeit non-significant, with FoxO1 knockdown, which is likely secondary to the partial rescue of cardiac hypertrophy (Figure XIA-B in the Supplement). Next, we examined genes that are regulated by pol II pause-release post-TAC, such as Psmd5 and Junb. Psmd5 encodes a regulatory, non-ATPase subunit of the 26S proteasome23, while Junb is a transcription factor that has been shown to be upregulated 15 minutes post-TAC, but returns to baseline within 6 hours24. These genes also have increased FoxO1 binding at their TSS and throughout their gene bodies (Figure 6K-L). As expected, we do not see any changes in the expression of Psmd5 or Junb 7 days post-TAC, nor do we detect any alterations with FoxO1 knockdown (Figure 6K-L). Again, these data suggest that FoxO1 may positively regulate cardiac hypertrophic growth, in vivo, via positive regulation of pol II de novo recruitment and pause-release.

FoxO1 deletion prevents cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vivo.

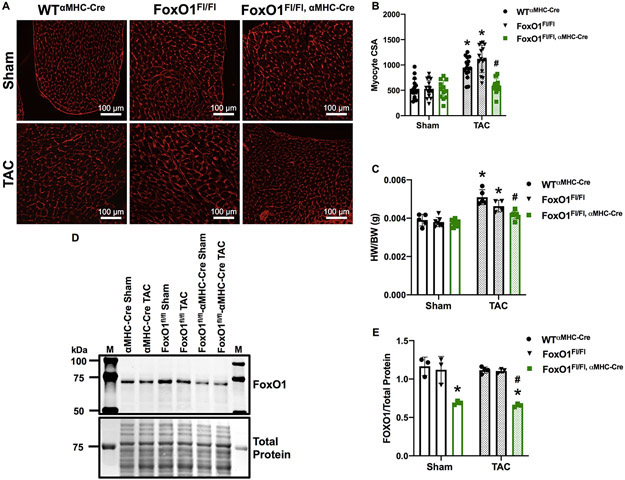

To corroborate our findings that AAV-mediated FoxO1 knockdown prevents pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, we measured cardiac hypertrophic growth in mice with cardiac-specific deletion of FoxO1 (FoxO1Fl/Fl,αMHC-Cre). Mimicking our observations with AAV.shFoxO1 treatment, FoxO1 knockout prevented TAC-induced increases in cardiomyocyte CsA versus controls (wild type (WT)αMHC-Cre or FoxO1Fl/Fl) (Figure 7A-B). Consistently, FoxO1 deletion prevented TAC-inducible increases in HW/BW versus controls (Figure 7C). Again, there were no significant changes in cardiac FoxO1 expression levels post-TAC versus sham-operated controls, and the extent of FoxO1 knockout was similar in sham or TAC-operated mice (40.8% and 43.7%, respectively) versus WT αMHC-Cre controls (Figure 7 D-E). Of note, we do not observe any differences in cardiac function, as assessed by EF and FS, at baseline (Figure XIIA-B in the Supplement) or 7 days post-TAC (Figure XIIC-D in the Supplement). Moreover, aortic mean and peak pressure gradients were similar in sham-operated mice, and equally increased post-TAC (12.9-fold and 14.0-fold for WTαMHC-Cre, 20.4-fold and 20.6-fold for FoxO1Fl/Fl, and 16.3-fold and 16.9-fold for FoxO1Fl/Fl,αMHC-Cre, respectively) (Figure XIIE-F in the Supplement). Tables with all major echocardiographic parameters including heart rate, systolic and diastolic diameter, LV mass, systolic and diastolic LVAW thickness, and systolic and diastolic LVPW thicknesses are also included (Figure XIIG in the Supplement).

Figure 7. FoxO1 deletion prevents cardiomyocyte hypertophy in vivo.

A-E Adult (12-week-old), male WTαMHC-Cre, FoxO1FL/FL, and FoxO1FL/FL,αMHC-Cre mice were subjected to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) or sham surgery for 7 days. A-B Hearts were harvested, fixed, and stained with 594 WGA. Representative images are shown in A. Cell cross-sectional area (CSA) was quantified using ImageJ software and plotted (B). Cardiomyocytes imaged= 16, 16, 12, 16, 15, 16 (WTαMHC-Cre-Sham, FoxO1FL/FL-Sham, FoxO1FL/FL,αMHC-Cre-Sham, WTαMHC-Cre-TAC, FoxO1FL/FL-TAC, and FoxO1FL/FL,αMHC-Cre-TAC). C Hearts were harvested and weighed. Heart weights (HW) were normalized to body weights (BW) and plotted as a ratio (HW/BW) in grams. n=5, 7, 9, 5, 4, 7 (WTαMHC-Cre-Sham, FoxO1FL/FL-Sham, FoxO1FL/FL,αMHC-Cre-Sham, WTαMHC-Cre-TAC, FoxO1FL/FL-TAC, and FoxO1FL/FL,αMHC-Cre-TAC). D-E Hearts were harvested, lysed, and subjected to Western blotting using the indicated antibody. Signals for forkhead box protein (Fox)O1 were quantified using densitometry, normalized to total protein, and plotted. n=3, 3, 3, 4, 3, 3 (WTαMHC-Cre-Sham, FoxO1FL/FL-Sham, FoxO1FL/FL,αMHC-Cre-Sham, WTαMHC-Cre-TAC, FoxO1FL/FL-TAC, and FoxO1FL/FL,αMHC-Cre-TAC). Error bars represent SEM. *p<0.05 versus WTαMHC-Cre-Sham and #p<0.05 versus WTαMHC-Cre-TAC using 2-way ANOVA. M=marker; WT=Wild type; αMHC=Alpha myosin heavy chain.

DISCUSSION

FoxO1 was reported to be an atrophic transcription factor, due to it’s targeting of Fbxo32. Moreover, its phosphorylation and nuclear export following adrenergic or angiotensin II receptor stimulation is pro-hypertrophic8, 13. On the other hand, our data uniquely show that in more chronic settings of hypertrophic stimulation, such as 7 days of catecholaminergic- or pressure overload-induced stress, FoxO1 remains localized to the nucleus. One possibility is that FoxO1 nuclear export is uncoupled from upstream signaling, through G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) kinase (GRK)-dependent receptor desensitization25. Consistently, beta-adrenergic receptor downregulation has been seen as early as 1 week post-TAC26. Furthermore, FoxO1 phosphorylation and nuclear export is also observed following insulin receptor stimulation, a regulatory mechanism that is lost during conditions of insulin resistance or diabetes27.

Interestingly, while we did not find any significant alterations in cytosolic versus nuclear localization of FoxO1 during cardiac hypertrophy, we did observe an overall increase in FoxO1 chromatin binding under these conditions. Consistently, we measured a reduction in FoxO1 phosphorylation at S256, a site, which when phosphorylated, has been shown to reduced FoxO1-DNA binding affinity14. Together, these data suggest that there is an unbound nuclear pool of FoxO1, which is not unprecedented for transcription factors and other transcriptional machinery. C-Fos, for example, is sequestered to the inner nuclear membrane during serum starvation via lamin A/C, which prevents its association with c-Jun and, therefore, the activity of this heterodimeric transcription factor, activating protein (AP-)128. Another example is positive transcription elongation factor (P-TEF)b, which is comprised of the cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk)9/Cyclin T complex necessary for pol II phosphorylation and elongation9. P-TEFb has been shown to bind hexamethylene bisacetamide-inducible (HEXIM) proteins, which sequester it to small nuclear RNA-protein (snRNP) complexes and inhibit its catalytic function29. Thus, it is possible that during cardiac hypertrophic stress, FoxO1 is released from nucleoplasmic or nuclear membranous pools to bind chromatin and regulate gene expression. It is also possible that ChIP-Seq is more sensitive technique in detecting FoxO1 changes versus tissue fractionation and Western blotting. Importantly, however, we did confirm an increase in chromatin-bound FoxO1 in cardiomyocytes stimulated with isoproterenol for 48 h via Western blotting, albeit with exogenous FoxO1 expression.

In addition to confirming an increase in FoxO1 chromatin binding in vitro, other steps were taken to ensure the high quality of our ChIP-Seq data. First, our ChIP was performed using a ChIP-Seq-validated antibody against FoxO1. The resultant data was then evaluated for the fraction of all reads that are present within peaks (FRiP). Generally, the guidelines outlined by the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia specify that a FRiP > 1% indicates reliable ChIP-Seq data30. The FRiP for our data was 5.3, 2.3, and 3.1% for sham/vehicle, isoproterenol, and TAC, respectively. The quality of the pol II ChIP-Seq antibody and dataset was also confirmed2. Additionally, our data was compared with FoxO1 ChIP-Seq performed in livers from wild type and FoxO1 knockout mice31. Notably, our peaks of FoxO1 enrichment overlapped with peaks found in genes that are also expressed in liver, such as Pdk4 (data not shown). These peaks were lost in the FoxOl knockout mouse liver ChIP-Seq data31. Finally, it should be noted that our data shows increased FoxO1 binding in two independent models of cardiac hypertrophy, namely isoproterenol treatment and TAC, and that the extent of increase correlates well with extent of hypertrophy in these models. Thus, we are confident in the quality of our FoxO1 ChIP-Seq data and subsequent conclusions.

From these data, the majority of chromatin-bound FoxO1 was detected at the TSS of genes, where it aligns with pol II. Thus, we hypothesize its role in the regulation of pol II dynamics and gene expression. It is important to note that TSS-detected FoxO1 is likely due to chromatin looping from promoter, in-gene, and intergenic genomic regions15, 17, as is supported by our motif analyses. This fact, however, does not affect our hypothesis regarding its function. Since FoxO1 binding is widespread and increases in genes regulated by pol II de novo recruitment, loss, and pause-release during hypertrophy, we speculated its role in the regulation of these subsets of genes. Not surprisingly, FoxO1 knockdown prevented the upregulation of Comtd1, Fstl1, and Uck2, which are genes that are regulated by pol II de novo recruitment and have increased FoxO1 binding during hypertrophy. Although FoxO1 also increases within genes regulated by pol II pause-release (i.e. Pfas, Psmd5, or Junb), the changes in their mRNAs are not measureable as they increase incrementally in parallel with the increase in cellular size2. Their inhibition by FoxO1 knockdown or knockout, however, is reflected in the inhibition of Et-1- or TAC-induced increases in cardiomyocyte size, particularly, since these genes represent a relatively large fraction (55.8%) of the pol II-regulated genes following pressure-overload, versus those regulated by de novo recruitment (5.9%) (see Table 2). It should be noted that Comtd1, Fstl1, and Uck2 are exemplary genes regulated by pol II de novo recruitment and Pfas, Psmd5, and Junb are exemplary genes regulated by pol II pause-release. These are part of a much larger FoxO1-mediated gene programs that represent hundreds and thousands of genes, respectively, of which the net effect of their transcriptional activation is prohypertrophic.

Regarding the mechanism, it is likely that FoxO1 indirectly regulates pol II and P-TEFb recruitment via intermediary molecules. Indirect recruiment may occur via molecules such as P300, FoxA1/2, or Brd4. P300 is a transcriptional coactivator with histone acetyltranferase (HAT) activity, which has been shown bind and acetylate FoxO1, with conflicting reports associating acetyl-FoxO1 with enhanced versus reduced transcriptional activity32-34. P300 contains a bromodomain that recognizes acetylated lysine residues35, as well as directly binds pol II36. It is, therefore, possible that P300 mediates FoxO1-dependent recruitment of pol II during cardiac hypertrophy. Interestingly, the role of histone acetylation, via P300 or other HATs, and its interplay with FoxO1 and pol II recruitment has yet to be investigated and likely plays a critical role. Notably, a recent set of studies demonstrates the requirement of FoxA1/2 binding to FoxO1 for chromatin relaxation and recruitment of pol II37, 38. Moreover, Brd4, another bromodomain-containing protein, has been show to be required for FoxO1-mediated transcription in certain cancers39, 40. Thus, Brd4 may also play a role on FoxO1-dependent pol II recruitment during cardiac growth.

While it is likely that FoxO1 indirectly regulates pol II or P-TEFb recruitment, via molecules such as P300, FoxA1/2, or Brd4, its differential regulation of pol II de novo recruitment, loss, and pause-release is not understood. One possibility is that the protein complexes that contain FoxO1, pol II, and P-TEFb have varying composition at differentially regulated loci. It is also possible that similar factors are involved but display temporal variation or differ in extent of binding. It is the elucidation of these crucial mechanistic details that will allow us to specifically target cardiomyopathy genes versus those that underlie adaptive growth.

In conclusion, our study is the first to outline the full extent of transcriptional regulation by FoxO1 in the heart. We demonstrated that through its regulation of a broad range of constitutively expressed genes, inhibition or loss of FoxO1 has the capacity to mitigate pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophic growth. We propose, however, that its utility as a therapeutic target for cardiac hypertrophy or failure requires further investigation, since inhibiting the increase in cardiac mass would increase wall stress, and thus be counterproductive. In accordance, the genome-wide approach that we applied to this study underscores the necessity for comprehensively identifying the genomic bindings of transcriptional machinery and their rearrangements during disease, as well as the mechanisms by which they mediate their effects. This information will allow for the design of more precise therapies to target transcription.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

What is new?

This study is the first to demonstrate that FoxO1 genomic binding is widespread in both the healthy and diseased heart, and increases during pathological hypertrophic growth.

This is also the first study to show that cardiac FoxO1 knockdown or deletion prevents hypertrophic growth induced by pressure overload.

Together, the data suggest that FoxO1 may contribute to cardiac hypertrophic growth via the regulation of RNA pol II de novo recruitment and pause-release, or the regulation of inducible and essential, incrementally increased genes.

What are the clinical implications?

These findings challenge the therapeutic targeting of FoxO1 during pathological cardiac hypertrophy, as it may regulate the transcription of a subset of inducible genes, as well as a subset of incrementally increased genes, which underlie adaptive cardiac growth.

This study underscores the necessity for understanding the full spectrum of targets and functions of transcription factors for their clinical targeting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is supported in part by NIH grants R37 HL061690, P01 HL075443, P01 HL091799, and P01 HL13460801 (to W.J.K.) and F32 HL139031 (to J.P.). W.J.K. is the William Wikoff Smith Endowed Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine and a 2018 MERIT Awardee from the American Heart Association (AHA). We would also like to thank Dr. Maha Abdellatif for kindly providing the adenoviruses.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the NIH [Grant Numbers: HL061690, HL075443, HL091799, and HL1346080 (to W.J.K.) and HL139031 (to J.P.)], the American Heart Association (AHA) [Grant Number: 18MERIT33900036 (to W.J.K.)], and the AHA and the Kahn Family Postdoctoral Fellowship in Cardiovascular Research [Grant Number: 18POST34060150 (to I.D.K)].

NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AAV

Adeno-associated virus

- Acta1

Actin alpha 1

- Actn2

Actinin alpha 2

- ACTC1

Cardiac alpha-actin

- Ad

Adenovirus

- AP-1

Activating Protein 1

- Brd4

Bromodomain-containing protein 4

- Cdk

cyclin-dependent kinase

- ChIP-Seq

Chromatin immunoprecipitation-deep sequencing

- Comtd1

Catechol-O-methyltransferase domain containing 1

- EF

Ejection Fraction

- Et-1

Endothelin-1

- FoxO1

Forkhead box protein O1

- FRiP

Fraction of reads in peaks

- FS

Fractional shortening

- FSTL1

Follistatin-related protein 1

- GFY

Golgi associated olfactory signaling regulator

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- GRK

G-protein coupled receptor kinase

- HAT

Histone acetyltranferase

- HDAC

Histone deacetylase

- HEXIM

Hexamethylene bisacetamide-inducible proteins

- HTLV1

Human T-cell leukemia virus 1

- IG

In-gene

- IGV

Integrated genome viewer

- Ins

Insulin

- Iso

Isoproterenol

- LVAW

Left ventricular anterior wall

- LVPW

Left ventricular posterior wall

- αMHC

Myosin heavy chain, alpha

- Nppa

Natriuretic peptide A

- NRVM

Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes

- Pfas

Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- Pol II

RNA polymerase II

- P-TEFb

Positive transcription elongation factor b

- Scr

Scramble

- TAC

Transverse aortic constriction

- TFIIB

General transcription factor IIB

- TSS

Transcription start site

- Uck2

Uridine-cytidine kinase 2

- Veh

Vehicle

- WGA

Wheat germ agglutinin

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no relevant disclosures or conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taegtmeyer H, Sen S and Vela D. Return to the fetal gene program: a suggested metabolic link to gene expression in the heart. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1188:191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sayed D, He M, Yang Z, Lin L and Abdellatif M. Transcriptional regulation patterns revealed by high resolution chromatin immunoprecipitation during cardiac hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:2546–2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sayed D, Yang Z, He M, Pfleger JM and Abdellatif M. Acute targeting of general transcription factor IIB restricts cardiac hypertrophy via selective inhibition of gene transcription. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:138–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao DJ, Wang ZV, Battiprolu PK, Jiang N, Morales CR, Kong Y, Rothermel BA, Gillette TG and Hill JA. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors attenuate cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4123–4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ooi JY, Tuano NK, Rafehi H, Gao XM, Ziemann M, Du XJ and El-Osta A. HDAC inhibition attenuates cardiac hypertrophy by acetylation and deacetylation of target genes. Epigenetics. 2015;10:418–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand P, Brown JD, Lin CY, Qi J, Zhang R, Artero PC, Alaiti MA, Bullard J, Alazem K, Margulies KB et al. BET bromodomains mediate transcriptional pause release in heart failure. Cell. 2013;154:569–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim Y, Phan D, van Rooij E, Wang DZ, McAnally J, Qi X, Richardson JA, Hill JA, Bassel-Duby R and Olson EN. The MEF2D transcription factor mediates stress-dependent cardiac remodeling in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:124–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ni YG, Berenji K, Wang N, Oh M, Sachan N, Dey A, Cheng J, Lu G, Morris DJ, Castrillon DH et al. Foxo transcription factors blunt cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting calcineurin signaling. Circulation. 2006;114:1159–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X, Kraus WL and Bai X. Ready, pause, go: regulation of RNA polymerase II pausing and release by cellular signaling pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40:516–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen EB and Lis JT. In vivo transcriptional pausing and cap formation on three Drosophila heat shock genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7923–7927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rougvie AE and Lis JT. The RNA polymerase II molecule at the 5’ end of the uninduced hsp70 gene of D. melanogaster is transcriptionally engaged. Cell. 1988;54:795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galbraith MD, Allen MA, Bensard CL, Wang X, Schwinn MK, Qin B, Long HW, Daniels DL, Hahn WC, Dowell RD et al. HIF1A employs CDK8-mediator to stimulate RNAPII elongation in response to hypoxia. Cell. 2013;153:1327–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Yano N, Deng M, Mao Q, Shaw SK and Tseng YT. beta-Adrenergic receptor-PI3K signaling crosstalk in mouse heart: elucidation of immediate downstream signaling cascades. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Gan L, Pan H, Guo S, He X, Olson ST, Mesecar A, Adam S and Unterman TG. Phosphorylation of serine 256 suppresses transactivation by FKHR (FOXO1) by multiple mechanisms. Direct and indirect effects on nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling and DNA binding. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45276–45284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng H and Bartholomew B. Emerging roles of transcriptional enhancers in chromatin looping and promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:13786–13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert SA, Jolma A, Campitelli LF, Das PK, Yin Y, Albu M, Chen X, Taipale J, Hughes TR and Weirauch MT. The Human Transcription Factors. Cell. 2018;175:598–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadauke S and Blobel GA. Chromatin loops in gene regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krakoff LR, Buccino RA, Spann JF Jr. and De Champlain J. Cardiac catechol O-methyltransferase and monoamine oxidase activity in congestive heart failure. Am J Physiol. 1968;215:549–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki T, Hoshi H and Mitsui Y. Endothelin stimulates hypertrophy and contractility of neonatal rat cardiac myocytes in a serum-free medium. FEBS Lett. 1990;268:149–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mangold CA, Yao PJ, Du M, Freeman WM, Benkovic SJ and Szpara ML. Expression of the purine biosynthetic enzyme phosphoribosyl formylglycinamidine synthase in neurons. J Neurochem. 2018;144:723–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimano M, Ouchi N, Nakamura K, van Wijk B, Ohashi K, Asaumi Y, Higuchi A, Pimentel DR, Sam F, Murohara T et al. Cardiac myocyte follistatin-like 1 functions to attenuate hypertrophy following pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E899–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki NN, Koizumi K, Fukushima M, Matsuda A and Inagaki F. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of human uridine-cytidine kinase 2. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:1477–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shim SM, Lee WJ, Kim Y, Chang JW, Song S and Jung YK. Role of S5b/PSMD5 in proteasome inhibition caused by TNF-alpha/NFkappaB in higher eukaryotes. Cell Rep. 2012;2:603–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rockman HA, Ross RS, Harris AN, Knowlton KU, Steinhelper ME, Field LJ, Ross J, Jr. and Chien KR. Segregation of atrial-specific and inducible expression of an atrial natriuretic factor transgene in an in vivo murine model of cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:8277–8281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi DJ, Koch WJ, Hunter JJ and Rockman HA. Mechanism of beta-adrenergic receptor desensitization in cardiac hypertrophy is increased beta-adrenergic receptor kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17223–17229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrino C, Naga Prasad SV, Mao L, Noma T, Yan Z, Kim HS, Smithies O and Rockman HA. Intermittent pressure overload triggers hypertrophy-independent cardiac dysfunction and vascular rarefaction. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1547–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aoyama H, Daitoku H and Fukamizu A. Nutrient control of phosphorylation and translocation of Foxo1 in C57BL/6 and db/db mice. Int J Mol Med. 2006;18:433–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivorra C, Kubicek M, Gonzalez JM, Sanz-Gonzalez SM, Alvarez-Barrientos A, O’Connor JE, Burke B and Andres V. A mechanism of AP-1 suppression through interaction of c-Fos with lamin A/C. Genes Dev. 2006;20:307–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobbi L, Demey-Thomas E, Braye F, Proux F, Kolesnikova O, Vinh J, Poterszman A and Bensaude O. An evolutionary conserved Hexim1 peptide binds to the Cdk9 catalytic site to inhibit P-TEFb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:12721–12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landt SG, Marinov GK, Kundaje A, Kheradpour P, Pauli F, Batzoglou S, Bernstein BE, Bickel P, Brown JB, Cayting P et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome Res. 2012;22:1813–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin DJ, Joshi P, Hong SH, Mosure K, Shin DG and Osborne TF. Genome-wide analysis of FoxO1 binding in hepatic chromatin: potential involvement of FoxO1 in linking retinoid signaling to hepatic gluconeogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11499–11509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perrot V and Rechler MM. The coactivator p300 directly acetylates the forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 and stimulates Foxo1-induced transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2283–2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuzaki H, Daitoku H, Hatta M, Aoyama H, Yoshimochi K and Fukamizu A. Acetylation of Foxo1 alters its DNA-binding ability and sensitivity to phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11278–11283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daitoku H, Sakamaki J and Fukamizu A. Regulation of FoxO transcription factors by acetylation and protein-protein interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1954–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mujtaba S, Zeng L and Zhou MM. Structure and acetyl-lysine recognition of the bromodomain. Oncogene. 2007;26:5521–5527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho H, Orphanides G, Sun X, Yang XJ, Ogryzko V, Lees E, Nakatani Y and Reinberg D. A human RNA polymerase II complex containing factors that modify chromatin structure. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5355–5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schill D, Nord J and Cirillo LA. FoxO1 and FoxA1/2 form a complex on DNA and cooperate to open chromatin at insulin-regulated genes. Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;97:118–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yalley A, Schill D, Hatta M, Johnson N and Cirillo LA. Loss of Interdependent Binding by the FoxO1 and FoxA1/A2 Forkhead Transcription Factors Culminates in Perturbation of Active Chromatin Marks and Binding of Transcriptional Regulators at Insulin-sensitive Genes. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:8848–8861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gryder BE, Yohe ME, Chou HC, Zhang X, Marques J, Wachtel M, Schaefer B, Sen N, Song Y, Gualtieri A et al. PAX3-FOXO1 Establishes Myogenic Super Enhancers and Confers BET Bromodomain Vulnerability. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:884–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagarajan S, Bedi U, Budida A, Hamdan FH, Mishra VK, Najafova Z, Xie W, Alawi M, Indenbirken D, Knapp S et al. BRD4 promotes p63 and GRHL3 expression downstream of FOXO in mammary epithelial cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:3130–3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brinks H, Boucher M, Gao E, Chuprun JK, Pesant S, Raake PW, Huang ZM, Wang X, Qiu G, Gumpert A et al. Level of G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2 determines myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via pro- and anti-apoptotic mechanisms. Circ Res. 2010;107:1140–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martini JS, Raake P, Vinge LE, DeGeorge BR Jr., Chuprun JK, Harris DM, Gao E, Eckhart AD, Pitcher JA and Koch WJ. Uncovering G protein-coupled receptor kinase-5 as a histone deacetylase kinase in the nucleus of cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12457–12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graham FL and Prevec L. Manipulation of adenovirus vectors. Methods Mol Biol. 1991;7:109–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.