Abstract

This article outlines the role of African civil society in safeguarding gains registered to date in sexual and reproductive health and the response to HIV. The case is made for why civil society organizations (CSOs) must be engaged vigilantly in the COVID-19 response in Africa. Lockdown disruptions and the rerouting of health funds to the pandemic have impeded access to essential sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and social protection services. Compounded by pre-existing inequalities faced by vulnerable populations, the poor SRH outcomes amid COVID-19 call for CSOs to intensify demand for the accountability of governments. CSOs should also continue to persevere in their aim to rapidly close community-health facility gaps and provide safety nets to mitigate the gendered impact of COVID-19.

Keywords: Africa, COVID-19, Civil society, CSOs, Gender, Sexual and reproductive health

Introduction

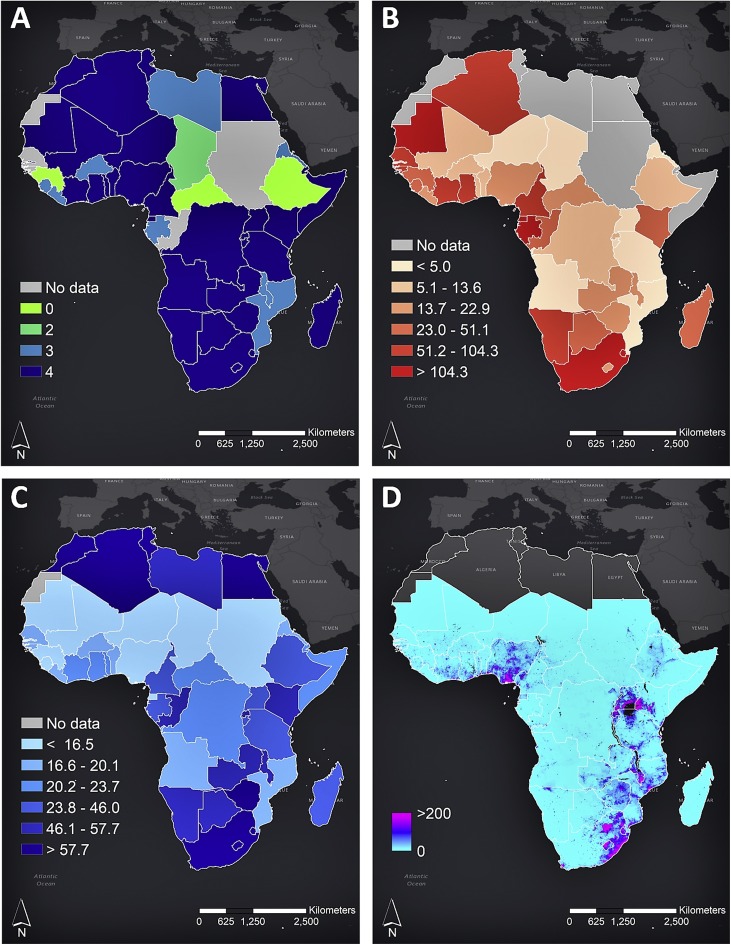

The emergence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Africa has presented the most severe public health challenge for the continent in recent history, placing 1.2 billion people at risk (El-Sadr and Justman, 2020). Health systems in Africa are already strained (Medinilla et al., 2020) as a result of other infectious diseases, such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis (TB) (Mhango et al., 2020). Currently, South Africa – one of the countries with the highest number of people living with HIV and with one of the largest TB burdens in the world (Hansoti et al., 2019, WHO, 2019) – has the highest number COVID-19 infections on the continent (Isilow, 2020) (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

(A) The durations of lockdowns in African countries. (B) COVID-19 attack rate per 100 000 people per country. (C) Estimates of contraceptive prevalence (any method and modern methods) for women aged 15–49 years in 2015. (D) Population density of people living with HIV (density per 5 km × 5 km pixel resolution).

The gendered impact of COVID-19, threatening sexual and reproductive health

COVID-19 does not discriminate, but its impact does. Africa has pre-existing inequalities that have resulted in economic and social injustices and poor health outcomes due to the extensive disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Experiences from the Ebola epidemic demonstrated a long-term adverse impact on sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes. This occurs when countries are concerned with emerging disease outbreaks (Chattu and Yaya, 2020) and reroute limited resources to contain epidemics while neglecting other essential health needs of their populations. In low and middle-income countries, public health disruption as a result of COVID-19 has been associated with a potential annual impact of a 10% decline in SRH service access, in particular by girls and women (Oladele et al., 2020, Riley et al., 2020).

The gendered impact of COVID-19 is illustrated by an upsurge in violence against women and girls in Africa (Ajayi, 2020, UN Women, 2020), specifically sexual gender-based violence (SGBV) and unintended pregnancies (The World Bank Group, 2020). Women and girls under stringent lockdown rules have had limited access to social protection, threatening their SRH rights (UN Women et al., 2020, United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2020). In Kenya, thousands of school girls have become pregnant during the lockdown period (Wadekar, 2020), and many pregnant women have had abruptly reduced options for care, as health centres that they normally access have shut down, with health care providers assigned to the pandemic response (MSF, 2020). In Tunisia, a survey illustrated that approximately 50% of SRH services have been either reduced or suspended since the onset of the pandemic (OECD, 2020b). It is anticipated that the COVID-19 lockdowns, which have continued for about 6 months, will have reduced access to contraceptives for approximately 47 million women in 114 low and middle-income countries, contributing to an additional seven million unintended pregnancies. Furthermore, it is anticipated that this will lead to about 13 million child marriages between 2020 and 2030 that would not otherwise have occurred (UNFPA, 2020). Likewise, access to HIV medicines by women and girls living with HIV and to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for female sex workers have been compromised. A recent mathematical modelling study predicted that disruption of the reliable antiretroviral therapy supply for individuals in need could lead to more than 500 000 additional deaths in sub-Saharan Africa in 2020–2021 (AVAC, 2020, UNAIDS, 2020b).

The gendered impact of COVID-19 is intensified by interrupted access to education (Burzynska and Contreras, 2020), skills development, and learning spaces, affecting adolescent girls and young women (AGYW). AGYW are expected to continue their education and learning through either online or home-based facilities, neither of which are accessible to more than 90% of learners on the African continent (da Silva, 2020). The education system across the continent is still far from ready to cope with the new delivery methods (Association for the Development of Education in Africa, 2020). As a result, AGYW on the continent have been derailed from their educational trajectory, while at the same time having impeded access to comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) and contraceptives, as well as increased exposure to SGBV, early and unintended pregnancy, female genital mutilation, poor menstrual hygiene management (Yamakoshi et al., 2020), and forced or child marriage. This adverse impact on SRH outcomes for AGYW has contributed to an increase in poor mental and psychosocial well-being, characterized by anxiety, depression, frustration, and feelings of isolation, and this has been compounded by their exposure to poverty and hunger (Plan International, 2020b).

The multidimensional poverty index (MPI) has worsened due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with 57.5% of the population of sub-Saharan Africa being already categorized as poor by the MPI before the pandemic (Alkire et al., 2020). This has exacerbated the risk of poor SRH outcomes for AGYW. Alongside the COVID-19 crisis, there has emerged a hunger crisis (United Nations, 2020, WHO, 2020) and an economic recession crisis (International Monetary Fund, 2020). The loss of access to income, food price increases, and weakened food chain supplies, coupled with the adverse impact of the climate crisis on agriculture and subsistence farming, have grossly reduced livelihood security for a high proportion of families in Africa (Blanke, 2020, FAO, 2020). Many have resorted to marrying off girl-children as a form of survival and security for the girl-child (Batha, 2020). Keeping girls in school is a proven strategy for achieving good SRH outcomes, as determined over a decade before the advent of COVID-19 (Haberland and Rogow, 2015, Kimera et al., 2019, UNFPA, 2013). Unfortunately, this preventative strategy is under serious threat by the pandemic.

The impact of COVID-19 on African civil society organizations (CSOs)

Most African CSOs pre-COVID-19 were already facing a series of hurdles. As efforts intensify to tackle the pandemic, it is prudent to prevent COVID-19 from potentially becoming ‘the crisis that crumbled CSOs’. Climate crisis, economic meltdowns, food insecurity, political strife, an exodus of skilled human capital (to the Global North), shrinking resource availability, and restrictive policies are among the hurdles navigated daily pre-COVID-19. During COVID-19, these challenges have worsened (Save the Children, 2020). New and different challenges have emerged, including and determining a reengineered mode of operating virtually and remotely as teams, with access to digital assets to enable efficient digital operations, abrupt cost-cutting, and access to cash and resources being the most uncertain (O’Connell, 2020). African CSOs are in jeopardy, as investors may overlook the vital role of CSOs in the continent’s health and development landscape, and hasten to invest only in governments. Aid agencies involved in the SRH and HIV response must continue to deliver on their Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) commitments, by promoting and funding a localization agenda where resources reach local partners, including women-led organizations (Plan International, 2020a). This calls for the need to support CSOs directly, as they hold first-hand knowledge on the needs of communities amid the impact of the pandemic.

Despite the backdrop reported above, African CSOs have continued to persevere with their commitment to advancing equality, safety, and security to the vast populations they support, reflecting the nature of resilience. Achieving the SDGs and United Nations Agenda 2030, specifically targets under SDGs 3, 4, and 10, and sustaining SRH and HIV response gains and saving lives, implicate the critical role CSOs have in the COVID-19 response. CSOs close gaps unmet by governments or aid agencies and provide safety nets for populations left behind. CSOs are best placed to foster an accountability agenda underscoring a human rights-based (HRB) COVID-19 response that recognizes the fundamental right to health (Pūras et al., 2020). CSOs ensure that interventions, reporting of data, and the dispatch of resources are done equitably, in an unbiased and inclusionary manner. When CSOs are engaged in the pandemic response, it becomes localized (Stevens, 2019), more relevant, and sustained (Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments, 2018). Reemphasizing the localization of services aligns with the intent of universal health coverage (UHC) to enable all people to have access to the health services they need, at the time they need them, and wherever they are (local, and not needing to travel far for the services). Meanwhile, supporting CSOs to establish digital accountability networks is imperative to ensure that their role in preventing injustice in the health sector is realized. This has been effective in maintaining SRH and HIV response momentum in the African context (Mullard and Aarvik, 2020), such as the Ushahidi open-source platform and the MobiSAfAIDS application (Pade-Khene et al., 2020).

African CSOs as tipping points in the SRH and HIV response during COVID-19

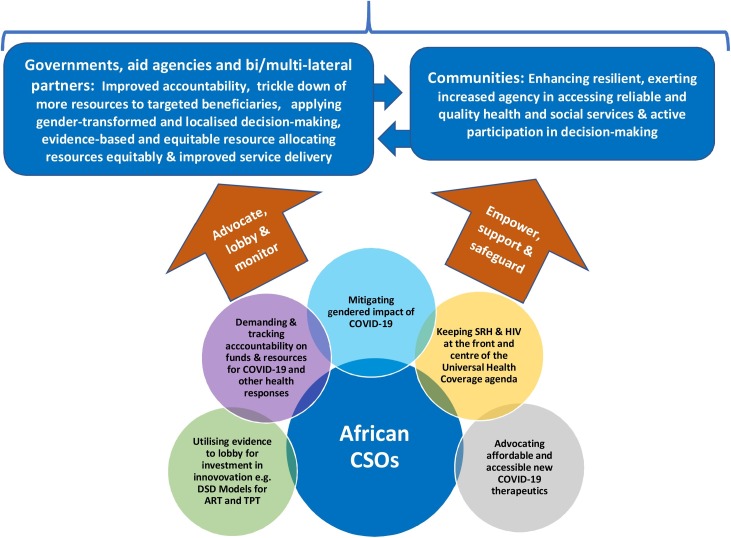

To amplify these comparative advantages and mitigate the detrimental effects of COVID-19 on SRH outcomes, African CSOs are urged to apply the following five principle actions, which are also summarized in Figure 2 .

Figure 2.

Conceptual model showing the role of African civil society organizations (CSOs) in the COVID-19 response.

1. Demanding and tracking the accountability of governments around optimal use of COVID-19 funds and resources. CSOs, as the citizenry, must exert duty-bearer accountability to report transparently on both resource usage and the true impact of the pandemic. Recently in Zimbabwe, the Minister of Health and Child Care was removed from position following allegations of fraud in a COVID-19 equipment deal of over US$ 60 million (Cassim, 2020). South Africa is probing allegations of corruption involving ZAR 500 billion (US$ 26.3 billion) of the COVID-19 relief fund allocated by the government to ease the impact of the pandemic (Hassan Isilow, 2020). Other cases of mismanaged COVID-19 funds have been reported in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, and Kenya (Nyabiage, 2020). These corruption risks were identified before the emergence of the above examples. CSOs must rise to the challenge of vigilantly taking stock of, and promoting, four key areas: public procurement, whistleblowing, free speech and press, and development aid. In addition, lessons learned on corruption during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa (2014–2016) (Transparency International, 2020) should be reinforced.

CSOs must institute health systems monitoring and assessment, and make recommendations for health systems strengthening, in co-operation with judicial systems, human rights institutions, and parliamentary structures, for the attainment of SRH rights throughout the pandemic. CSOs can further facilitate digital civic participation in social accountability monitoring processes, which are feasible to sustain in the African context. Concurrently, CSOs need to advocate governments to pursue commitments made in alleviating the humanitarian crisis, including strengthening the implementation of the ‘Grand Bargain’, so that resources reach local actors (Development Initiatives, 2020).

2. Keeping SRH and HIV central to the UHC agenda, by ensuring African policymakers and aid agencies do not divert from the UHC commitments amid the pandemic. This requires that the rechannelling of funds to the COVID-19 response does not compromise other essential healthcare and that a minimum initial services package (MISP) continues to be availed to all (Tran et al., 2020). This is particularly critical for settings that are fragile and in the humanitarian state, which characterizes several African countries. Where minimal resources in health care systems have been abruptly rechannelled to the COVID-19 response, services such as SRH and HIV services have been de-prioritized. As such, CSOs must monitor the plight of disadvantaged and at-risk populations (MSF, 2020, The Global Fund, 2020, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2020) amidst pandemic disruptions. They must remain emphatic and bold in their advocacy to government and aid agencies, so that human rights and dignity are upheld and ‘no-one is left behind’ within the pandemic response. CSOs must remind governments of the fundamental right to health, beyond the pandemic, and demand inclusion. A bold example is a stance taken by the Moroccan CSOs, who exerted agency for inclusion upon realising their exclusion from the outpatient management strategy (APA News, 2020).

3. Utilizing evidence in lobbying governments to invest in innovative and good practice models, such as a differentiated service delivery (DSD) approach that facilitates multi-month antiretroviral access in the HIV response, to TB preventative treatment (TBT), within the COVID-19 response. CSOs must vigilantly identify working models, to motivate their replication and scale-up. An example is the leveraging of the HIV Coverage, Quality, and Impact Network (CQUIN) by ICAP to foster a real-time exchange of questions, resources, and lessons learned related to DSD and COVID-19, including the utilization of a special webinar series and a dedicated WhatsApp group (ICAP, 2020). Such initiatives enable South-to-South exchange as network countries confront the pandemic. Another good practice is from Algeria, where people living with HIV (PLHIV) have been identified as a priority population in the national COVID-19 response plan. CSOs play an active role in this plan, by collaborating with the government in enabling continuity of HIV prevention, treatment, and care services, including dispensing multi-month antiretrovirals to PLHIV, using a volunteer method (UNAIDS, 2020a).

Towards this principle, CSOs also have a critical role to play in unlocking barriers to access to information, social protection, and safety nets for communities. Disadvantaged populations, including women, displaced persons, and key populations, would need special attention under the prevailing circumstances. CSOs can galvanize access to communication and prevent physical distancing turning into isolation for populations most vulnerable to poor SRH outcomes.

4. Mitigate the gendered impact of COVID-19, by tracking and input into response designs by governments, to avert gender-based disparities (International Budget Partnership, 2020, ReliefWeb, 2020). This involves ensuring that women participate in COVID-19 response decision-making and that their needs are integrated into policy, service delivery, and investment decisions. Where women and girls have limited access to communication, including data for mobile phones, this has compromised their reporting in the event that they are in unsafe situations, such as violence. CSOs with lay community health cadres can close service gaps for women by facilitating the provision of contraceptives, counselling, and preventative services related to maternal health, thus averting mortality (Roberton et al., 2020). CSO cooperation with other social movements and unions will enhance the clamp down on the gendered impact of the pandemic. An example comes from the Gambia, where the Gambian Teachers Union has media outreach against girl-child marriages, promoting the participation of girls in distance learning and providing telephone hotlines for reporting sexual violence cases (Education International, 2020).

5. Advocate that African governments remain vigilant in securing access to new therapeutics at reasonable cost from the global market and ensure that biomedical solutions are not monopolized or restrained by trade or export bans and restrictions (OECD, 2020a). This is particularly crucial in light of the anticipated reduction in Africa’s GDP growth in 2020 (McKinsey and Company, 2020). Simultaneously, it should be ensured that anti-meritocracy measures are consciously applied in order to mitigate inequitable access as new medicines are made available. COVID-19 is an opportunity for instituting more equitable systems that leave no-one behind.

A key ingredient to effectively applying the five principle actions and increasing the legitimacy of African CSOs is to perform an introspective examination of their operative shortcomings and unique competencies. CSOs will be better positioned to execute the mandates outlined above amid COVID-19 if they adopt the following: (i) organized coordination and defined cooperation between CSOs within and between countries; (ii) strengthened transparency; and (iii) the engagement of human capital, including people who are additionally skilled in integrating digital innovation into the SRH and HIV response.

African CSOs have an opportunity to capitalize on the global pause-button activated as a result of the pandemic. They can leverage this opportunity to define a new norm that enables a more sustained SRH response that can withstand crises and new hazards post-COVID-19. As such, this will enable better continental preparedness in potential future shocks and preserve the trajectory towards achieving the SDGs by 2030 and the African Union Agenda 2063. Out of the looming crisis, a reframed social contract that places health at its centre could be a legacy of COVID-19 (The Lancet, 2020).

Funding

No funding to declare.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Disclaimer

The conclusions in this viewpoint are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of their employers.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Rouzeh Eghtessadi: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Zindoga Mukandavire: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Farirai Mutenherwa: Writing - review & editing. Diego Cuadros: Visualization, Writing - review & editing. Godfrey Musuka: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

References

- Ajayi T. 2020. Violence against Women and Girls in the Shadow of Covid-19: Insights from Africa. Available from: https://kujenga-amani.ssrc.org/2020/05/20/violence-against-women-and-girls-in-the-shadow-of-covid-19-insights-from-africa/ [Google Scholar]

- Alkire S., Dirksen J., Nogales R., Oldiges C. 2020. Multidimensional Poverty and COVID-19 Risk Factors: A Rapid Overview of Interlinked Deprivations across 5.7 Billion People. Available from: https://ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/B53_Covid-19_vs3-2_2020_online.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- APA News . 2020. Moroccan CSOs seek role in Covid-19 response plans. Available from: http://apanews.net/en/pays/maroc/news/moroccan-csos-seek-role-in-covid-19-response-plans. [Accessed 24 August 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Association for the Development of Education in Africa . 2020. Delivering education at home in African member states amid the Covid-19 pandemic: Country status report. Available from: http://www.adeanet.org/sites/default/files/report_education_at_home_covid-19.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- AVAC . 2020. We need DSD now more than ever: The frontier of human rights-centered services for HIV treatment & prevention. Available from: https://www.avac.org/blog/dsd-human-rights-centered-services-hiv-tx-px. (Accessed 22 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Batha E. 2020. Coronavirus could put 4 million girls at risk of child marriage. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/coronavirus-early-child-marriage-covid19-pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Blanke J. 2020. Economic impact of COVID-19: Protecting Africa’s food systems from farm to fork. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2020/06/19/economic-impact-of-covid-19-protecting-africas-food-systems-from-farm-to-fork/ [Google Scholar]

- Burzynska K., Contreras G. Gendered effects of school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1968. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31377-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassim J. 2020. Zimbabwe health minister fired over $60M COVID-19 graft. Available from: Zimbabwe health minister fired over $60M COVID-19 graft. [Google Scholar]

- Chattu V.K., Yaya S. Emerging infectious diseases and outbreaks: implications for women’s reproductive health and rights in resource-poor settings. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-0899-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva I.S. 2020. Covid-19 reveals digital divide as Africa struggles with distance learning. Available from: https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/covid-19-reveals-digital-divide-as-africa-struggles-with-distance-learning-37299. [Google Scholar]

- Development Initiatives . 2020. Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2020. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-humanitarian-assistance-report-2020. [Google Scholar]

- Education International . 2020. The Gambia: Social Dialogue at Heart of COVID-19 Response. Available from: https://www.ei-ie.org/en/detail/16831/the-gambia-social-dialogue-at-heart-of-covid-19-response. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sadr W.M., Justman J. Africa in the Path of Covid-19. N Eng J Med. 2020;383(3):e11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO . 2020. Smallholder Producer Organizations and family farmers are paramount to keep food systems alive in Africa. Available from: http://www.fao.org/africa/news/detail-news/en/c/1295148. (Accessed 23 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments . 2018. Local and Regional Governments report to the High Level Political Platform (HLPF) Available from: https://www.uclg.org/sites/default/files/towards_the_localization_of_the_sdgs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Haberland N., Rogow D. Sexuality education: emerging trends in evidence and practice. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(1 Suppl):S15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansoti B., Mwinnyaa G., Hahn E., Rao A., Black J., Chen V. Targeting the HIV Epidemic in South Africa: The Need for Testing and Linkage to Care in Emergency Departments. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;15:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan Isilow S. 2020. Africa probing graft allegations over COVID-19 funds. Anadolu Agency. [Google Scholar]

- ICAP . 2020. The CQUIN Project for Differentiated Service Delivery.https://cquin.icap.columbia.edu/network-focus-areas/covid-19/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- International Budget Partnership . 2020. Let’s protect each other: IBP South Africa’s COVID-19 response. Available from: https://www.internationalbudget.org/2020/04/covid-19-in-south-africa/. (Accessed 24 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund . 2020. Regional Economic Outlook. Sub-Saharan Africa: COVID-19: An unprecedented threat to development. Available from: https://www.imf.org/∼/media/Files/Publications/REO/AFR/2020/April/English/ch1.ashx?la=en. [Google Scholar]

- Isilow H.S. 2020. Africa bears 5th largest COVID-19 global case. Independent Press2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kimera E., Vindevogel S., Rubaihayo J., Reynaert D., De Maeyer J., Engelen A.M. Youth living with HIV/AIDS in secondary schools: perspectives of peer educators and patron teachers in Western Uganda on stressors and supports. SAHARA J: J Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Res Alliance. 2019;16(1):51–61. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2019.1626760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey and Company . 2020. Tackling COVID-19 in Africa. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/middle-east-and-africa/tackling-covid-19-in-africa#. (Accessed 24 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Medinilla A., Byiers B., Apiko P. 2020. African Regional Responses to COVID-19. Available from: https://ecdpm.org/wp-content/uploads/African-regional-responses-COVID-19-discussion-paper-272-ECDPM.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mhango M., Chitungo I., Dzinamarira T. COVID-19 Lockdowns: Impact on Facility-Based HIV Testing and the Case for the Scaling Up of Home-Based Testing Services in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Behav. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02939-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MSF . 2020. Women and Girls Face Greater Dangers during COVID-19 pandemic. Available from: https://www.msf.org/women-and-girls-face-greater-dangers-during-covid-19-pandemic. (Accessed 24 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Mullard S., Aarvik P. 2020. Supporting Civil Society during the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Potentials of online Collaborations for Social Accountability. Available from: https://www.u4.no/publications/supporting-civil-society-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nyabiage J. 2020. Coronavirus: African Nations Battle Corruption, Profiteering linked to PPE, test kits. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3096635/coronavirus-african-nations-battle-corruption-profiteering. (Accessed 24 August 2020) [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell S. 2020. How to Reform NGO Funding so we can deal with threats like COVID-19. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/how-to-reform-ngo-funding-so-we-can-deal-with-threats-like-covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2020. COVID-19 and Africa: Socio-Economic Implications and Policy Responses. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-and-africa-socio-economic-implications-and-policy-responses-96e1b282/. (Accessed 24 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2020. COVID-19 crisis in the MENA Region: Impact on Gender Equality and Policy Responses. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-crisis-in-the-mena-region-impact-on-gender-equality-and-policy-responses-ee4cd4f4/. (Accessed 24 August 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Oladele T.T., Olakunde B.O., Oladele E.A., Ogbuoji O., Yamey G. The impact of COVID-19 on HIV financing in Nigeria: a call for proactive measures. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pade-Khene C., Sieborger I., Ngwerume P., Rusike C. 2020. Enabling Digital Social Accountability Monitoring of Adolescent Sexual Reproductive Health Services: MobiSAfAIDS. Available from: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2020_rp/36. [Google Scholar]

- Plan International . 2020. The impacts of Covid-19 on girls in crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Plan International . 2020. Living under Lockdown: Girls and COVID-19. Available from: https://plan-international.org/publications/living-under-lockdown. [Google Scholar]

- Pūras D., de Mesquita J.B., Cabal L., Maleche A., Meier B.M. The right to health must guide responses to COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1888–1890. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31255-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ReliefWeb . 2020. USAID-Supported Moroccan Civil Society Organizations Respond and Adapt to the COVID-19 Outbreak. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/morocco/usaid-supported-moroccan-civil-society-organizations-respond-and-adapt-covid-19. (Accessed 24 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Riley T., Sully E., Ahmed Z., Biddlecom A. Estimates of the Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sexual and Reproductive Health In Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int Perspect Sexual Reprod Health. 2020;46:73–76. doi: 10.1363/46e9020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberton T., Carter E.D., Chou V.B., Stegmuller A.R., Jackson B.D., Tam Y. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(7) doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30229-1. e901-e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children . 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on African civil society organizations: Challenges, responses and opportunities. Available from: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/impact-covid-19-african-civil-society-organizations-challenges-responses-and-opportunities. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens I.L. 2019. Healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa: What are the answers? [Google Scholar]

- The Global Fund . 2020. COVID-19 Information Note: Considerations for Global Fund Support for HIV. [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet COVID-19: remaking the social contract. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1401. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30983-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank Group . 2020. Gender Dimensions of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available from: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/618731587147227244/pdf/Gender-Dimensions-of-the-COVID-19-Pandemic.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Tran N.T., Tappis H., Spilotros N., Krause S., Knaster S. Not a luxury: a call to maintain sexual and reproductive health in humanitarian and fragile settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(6) doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30190-X. e760-e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transparency International . 2020. Corruption risks in Southern Africa’s response to the coronavirus. Available from: https://www.transparency.org/en/news/corruption-risks-in-africas-response-to-the-coronavirus#. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women . 2020. COVID-19 and the link to Violence against Women and Girls. Available from: https://africa.unwomen.org/en/news-and-events/stories/2020/04/covid-19-and-the-link-to-violence-against-women-and-girls. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women, IDLO, UNDP, UNODC . Justice for Women amidst COVID-19. 2020. World Bank, The Pathfinders. Available from: https://www.idlo.int/sites/default/files/pdfs/publications/idlo-justice-for-women-amidst-covid19_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . 2020. COVID-19 and HIV Lessons learned, country actions and responses by the Joint Programme. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/PCB46_COVID19_CRP1.pdf. (Accessed 24 August 2020) [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . 2020. Global AIDS update 2020. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_global-aids-report_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA . 2013. The State of World Population 2013. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/EN-SWOP2013-final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA . 2020. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender-based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/COVID-19_impact_brief_for_UNFPA_24_April_2020_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition. Available from: https://namibia.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/sg_policy_brief_on_covid_impact_on_food_security.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner . 2020. COVID-19 and Women’s Human Rights: Guidance. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/COVID-19_and_Womens_Human_Rights.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs . 2020. Global Humanitarian Response Plan Covid-19. Available from: https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/Global-Humanitarian-Response-Plan-COVID-19.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wadekar N. 2020. Kenya’s Teen Pregnancy Crisis: More than COVID-19 is to blame. Available from: https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2020/07/13/Kenya-teen-pregnancy-coronavirus. [Accessed 24 August 2020] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2019. Global Tuberculosis Report 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. As more go Hungry and Malnutrition persists, achieving Zero Hunger by 2030 in doubt, UN report warns. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/13-07-2020-as-more-go-hungry-and-malnutrition-persists-achieving-zero-hunger-by-2030-in-doubt-un-report-warns. [Accessed 22 July 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakoshi B., Burgers L., Sagan S., Muralidharan A., Mahon T., Barrington D. 2020. Brief: Mitigating the Impacts of COVID-19 and Menstrual Health and Hygiene. Available from: https://api.research-repository.uwa.edu.au/portalfiles/portal/78218515/2020_Brief_on_mitigating_the_impacts_of_COVID_19_on_menstrual_health_and_hygiene_with_logos_27_April_2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]