Highlights

-

•

This research explores the managers’ adaptation strategies resulting from BYOD usage by employees.

-

•

The authors operationalize and enrich the coping model of user adaptation (CMUA).

-

•

This research sheds light on the decisional processes in the adoption of coping strategies.

-

•

The impact of the CMUA constructs varies according to the pre- or post-implementation period.

-

•

This work helps managers for maximizing BYOD-related benefits and maintaining satisfactory corporate information security.

Keywords: BYOD, Reversed IT adoption, CMUA, Coping, Emotion-focused

Abstract

The adoption of Bring Your Own Device (BYOD), initiated by employees, refers to the provision and use of personal mobile devices and applications for both private and business purposes. This bottom-up phenomenon, not initiated by managers, corresponds to a reversed IT adoption logic that simultaneously entails business opportunities and threats. Managers are thus confronted with this unchosen BYOD usage by employees and consequently adopt different coping strategies. This research aims to investigate the adaptation strategies embraced by managers to cope with the BYOD phenomenon. To this end, we operationalized the coping model of user adaptation (CMUA) in the organizational decision-making context to conduct a survey addressing 337 top managers. Our main results indicate that the impact of the CMUA constructs varies according to the period (pre- or post-implementation). The coping strategies differ between those who have already implemented measures to regulate BYOD usage and those who have not. We contribute to theory by integrating the perception of BYOD-related opportunities and threats and by shedding light on the decisional processes in the adoption of coping strategies. The managerial contributions of this research correspond to the improved protection of corporate information and the maximization of BYOD-related benefits.

1. Introduction

The BYOD phenomenon, i.e., Bring Your Own Device, refers to the provision and use of personal mobile devices and applications by employees for both private and business purposes (Cho & Ip, 2018; Hovav & Putri, 2016; Middleton, Scheepers, & Tuunainen, 2014). As opposed to the classic top-down adoption usually imposed by top management, the BYOD phenomenon is considered to be a disruptive event that is often a bottom-up process, in other words, reversed IT adoption starting with employees (Leclercq-Vandelannoitte & Bertin, 2018).

Since its early period 10–15 years ago, BYOD has undergone major changes. The first evolution related to the devices themselves, which were initially limited to mobile phones and laptops and now include smartphones (approximately 90 %), tablets, and connected devices. The second evolution corresponds to the power and increased connectivity of devices: today’s smartphones can include up to 10 cores, offering performance similar to low-end laptops. In terms of connectivity, if the speed of Internet connections underwent dramatical acceleration,1 the range of networks now includes hi-speed Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and NFC.2 Elaborated applications can operate on personal devices, ranging from emails to critical business applications, such as CRM and ERPs (Ding et al., 2014). In addition, access to cloud-based applications and storage has reinforced even more the variety and sophistication of applications. Operating systems have also evolved from proprietary and often secured solutions (e.g., Blackberry phones) to more open and democratized platforms, such iOS and Android.

However, although all of these evolutions increase significantly the opportunities offered by mobile and connected devices, they also involve higher risks. BYOD opportunities are reflected by recent figures showing that companies favoring BYOD obtain an annual savings of $350 per year per employee (Cisco, 2016). Using portable devices for work tasks can also increase productivity by 34 % (Frost and Sullivan, 2016). BYOD threats relate to additional security breaches, mainly data leakage and malware infiltration. For example, in 2017, employeeowned devices were culpable in 51 % of corporate data breaches (AT and T, 2017). Such breaches not only endanger the firm itself but also allow access to companies’ external partners through the Internet or other digital exchanges, dramatically increasing their vulnerability to cyber-attacks (Lowry, Dinev, & Willison, 2017; McLeod & Dolezel, 2018; Sokolova, Perez, & Lemercier, 2017). However, despite laws and regulations, there is a lack of effective security measures regarding the specificity of BYOD: for instance, only 40 % of employees are subject to regulations regarding personal device usage (Kemper, 2018).

These figures emphasize the importance of this phenomenon, all the more so because BYOD is increasingly used in businesses and often spontaneously introduced by employees without any regulations to prevent security issues (Weeger et al., 2020). Employees have an individualistic perception of BYOD opportunities, and their security concerns are mainly focused on privacy issues. However, managers go beyond these individual issues and must consider the organizational impacts of BYOD. Unfortunately, managers do not necessarily perceive the actual opportunities and threats that “rogue” adoption of BYOD represents for their organizations. Since they can barely prohibit its usage within the firm (Baillette, Barlette, & Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, 2018), especially because the company does not own the devices, they often make reactive decisions according to their own subjective perceptions of BYOD opportunities and threats (Hu, Dinev, Hart, & Cooke, 2012; Puhakainen & Siponen, 2010).

The previous research regarding the perception of BYOD-related opportunities has mainly focused on individuals and has highlighted a set of factors determining the adoption of mobile tools by employees (Hoehle, Zhang, & Venkatesh, 2015; Middleton et al., 2014; Weeger, Wang, & Gewald, 2016). In terms of BYOD-related threats, the literature has addressed issues related to employee privacy (Garba Bello, Murray, & Armarego, 2017; Pentina, Zhang, Bata, & Chen, 2016) and employee compliance with information security (ISS) policies (Cho & Ip, 2018; Palanisamy, Norman, & Mat Kiah, 2020). Academic research studying how managers cope address bottom-up adoption of BYOD and the types of decisions that they consequently make has been scarce (Baillette et al., 2018; Baker & Singh, 2019; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte & Bertin, 2018; Tu & Yuan, 2015).

Therefore, obtaining insights into managers’ coping strategies is important to better understand how they can address and regulate BYOD usage, i.e., maximizing the benefits and mitigating the threats. This understanding will also enable managers to better administer and adapt policy and regulatory measures. This article thus investigates the following research question: what adaptation strategies do managers adopt to cope with the BYOD phenomenon? This implies the investigation of (a) managers’ perception of BYOD opportunities and threats; and (b) the coping strategies they decide to adopt accordingly.

We use the coping model of user adaptation (CMUA, Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005, 2010), based on Lazarus’ coping theory (1966). This model allows us to investigate the determinants of managers’ “behaviors that occur before, during, and after the implementation of a new IT” (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005, p. 2) and their resulting coping strategies. It also fits individual, as well as organizational, contexts (Tobler, Colvin, & Rawlins, 2017). However, the research has seldom used this model, with mostly qualitative methods (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2010; Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005; Elie-Dit-Cosaque & Straub, 2011; Tobler et al., 2017). In this article, we test the CMUA framework through a quantitative study of 337 managers.

Our article contributes to the academic literature in IS by offering insights into managers’ perceptions of BYOD adoption by employees, encompassing both opportunities and threats and the decisions stemming from these perceptions. Four types of coping strategies are investigated and discussed, hereby extending the literature on IT adoption, reversed IT adoption, and information security. An important managerial implication of this paper is the identification of a “stop-and-start” process, reflecting evolution of managers’ perceptions before and after addressing BYOD usage in their companies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the theoretical background of BYOD and the CMUA. In Section 3, we present the research model and develop hypotheses. Section 4 describes the research methods that we use to determine the decisions stemming from managers’ perceptions of BYOD implementation and set forth how we complement the CMUA framework. The results are presented in Section 5. This analysis is followed in Section 6 by a discussion of the findings; the contributions to theory, practice and policies; and the study’s limitations and suggestions for future research.

2. Theoretical background

Researchers and practitioners agree that BYOD is illustrative of the IT consumerization trend (Jarrahi, Crowston, Bondar, & Katzy, 2017; Koch, Yan, & Curry, 2019; Köffer, Ortbach, Junglas, Niehaves, & Harris, 2015; Weeger et al., 2020; Zhang, Mouritsen, & Miller, 2019). By reversing the traditional IT adoption logic (Baillette et al., 2018), BYOD creates a disruption in adoption practices (Köffer et al., 2015; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte & Bertin, 2018; Steelman, Lacity, & Sabherwal, 2016) and requires new managerial decisions and behaviors (Koch et al., 2019). One challenge for researchers is shedding light on this phenomenon. To do so, in the first subsection, we present the theoretical underpinnings of BYOD opportunities and threats. We then detail the possible interventions (at technological or behavioral levels) and focus on the importance of adopting suitable managerial behaviors to address the organizational issues involved in BYOD usage. In the second subsection, we introduce the CMUA framework, which allows us to investigate the behaviors (coping strategies) resulting from managers’ appraisals of opportunities and threats.

2.1. Opportunities and threats of BYOD

2.1.1. BYOD and its related opportunities

Since it is usually initiated by employees themselves, BYOD has been shown to increase their autonomy, motivation, satisfaction, innovation and performance (Harris, Ives, & Junglas, 2012; Koch et al., 2014). This employee-chosen adoption leads to easier assimilation and more efficient use, and employees can creatively adapt their own tools and reinterpret workplace tasks (Schmitz, Teng, & Webb, 2016). BYOD improves the quality of employee interactions, helps to recognize employees’ achievements and encourages peer-to-peer employee recognition, in turn favoring employee retention.

Organizations can also benefit from numerous tool-embedded innovations (Cook et al., 2013; Köffer et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019), such as the use of social media, which has proved its efficiency regarding firm performance (Chatterjee & Kar, 2020). For example, employees can use personal apps that initiate new ways to serve the firm’s objectives in terms of work performance (Doargajudhur & Dell, 2019; Junglas, Goel, Ives, & Harris, 2019; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte & Bertin, 2018). By doing so, BYOD enables employees to initiate changes that lead to improving and rethinking some organizational processes (Koch et al., 2019; Köffer et al., 2015). Because these devices are the employees’ property, BYOD reduces organizational costs in terms of tool funding or management (Baillette et al., 2018). Furthermore, some emergency situations, such as those related to pandemics (such as Covid-19), promote the use of BYOD when professional devices are no longer accessible (Davison, 2020; Papagiannidis, Harris, & Morton, 2020; Richter, 2020). BYOD becomes a necessary practice because it enables employees to continue to communicate and work despite social distancing and new working conditions.

Finally, at an organizational level, BYOD opportunities correspond to cost savings (Benlian & Hess, 2011; Steelman et al., 2016); productivity gains (Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, 2015a; Morrow, 2012; Singh, 2012; Steelman et al., 2016); increased innovation, mainly in terms of business process improvement (Aydiner, Tatoglu, Bayraktar, & Zaim, 2019; Law & Ngai, 2007; Zhou, Lu, & Wang, 2010), and performance expectancy (Moore & Benbasat, 1991; Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, & Davis, 2003).

2.1.2. BYOD and its related threats

BYOD and mobile applications involve security issues not only threatening their adoption and diffusion (Balapour, Nikkhah, & Sabherwal, 2020) but also increasing the threats to organizational data, for several reasons. First, hyperconnected BYOD tools increase the complexity of network protection because they can connect to several types of networks (cellular networks, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and NFC), (Breitinger, Tully-Doyle, & Hassenfeldt, 2020; McLeod & Dolezel, 2018; Palanisamy et al., 2020) and to cloud computing resources, thereby increasing the risks (Ding et al., 2014; Gupta, Seetharaman, & Raj, 2013; Lian, Yen, & Wang, 2014; Morrow, 2012; Sultan, 2014). Smartphones and tablets are increasingly connected to applications, storage or other digital services, resulting in greater risks (Mustafa & Kar, 2019). In addition, cloud-based resources are often located in public clouds, which are more prone to malware, viruses (Ali, Shrestha, Soar, & Fosso Wamba, 2018) and unauthorized access by cloud administrators (Kaw et al., 2019). More recently, the explosion of IoT and connected devices brought to work by employees has worsened the risks (Kaw et al., 2019; Tanenbaum, 2016) because connections and even devices themselves are often poorly secured.

Second, the use of personal tools for work also increases the risk that devices will be lost or stolen (Jones & Chin, 2015; Nokia, 2019; Tu, Turel, Yuan, & Archer, 2015), endangering organizational data (Baillette et al., 2018). Third, smartphones have become a lucrative target for cybercriminals (Chatterjee, Kar, Dwivedi, & Kizgin, 2019; Checkpoint, 2020), and corporate data can be corrupted by attacks through hacked or malware-infected smartphones. Fourth, since employees own the devices, their run greater risks when using BYOD than they do when using corporate tools (Hovav & Putri, 2016) or computers (McGill & Thompson, 2017; Thompson et al., 2017). Moreover, it is more difficult to monitor their usage and compliance with organizational policies and regulations (Hovav & Putri, 2016). The risk is even greater for younger generations, mainly digital natives, because they tend to only see the potential benefits of BYOD and neglect the risks to themselves and their institutions (Baillette & Barlette, 2020; Weeger et al., 2020). Employees’ priority is mainly to protect their private information (Mustafa & Kar, 2019), and they might less care about their organizational data since they are less “personally relevant” (Barlette & Jaouen, 2019). Moreover, privacy-protective controls and settings on mobile devices are difficult to find and activate, and employees can be reluctant to enact privacy-protective behaviors (Crossler & Bélanger, 2019).

Therefore, seen from a manager’s perspective, BYOD can harm the organization’s information system security and lead to failure. Failure can correspond to information failure (compromised data security), functional failure and system failure and can eventually lead to service failure from companies (Mustafa, Kar, & Janssen, 2020).

2.1.3. How can managers address BYOD opportunities and threats?

A manager mainly considers the BYOD-related perceived opportunities at the organizational level. Tobler et al. (2017) showed that people in power usually focus on problems and adapt technologies to their own ways of working. Hence, to reap these benefits, managers can guide the required changes in business processes. Managers can also facilitate change and innovation by transforming their management practices (Damanpour, 2014; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, 2015b). They can also simply be supportive, i.e., provide top management support (TMS, Boonstra, 2013) in seizing the benefits of BYOD usage by showing their involvement, being participative and providing resources when necessary (Liu, Wang, & Chua, 2015).

To mitigate the risks stemming from BYOD usage by employees, many IT-based possibilities exist, such as reinforced passwords, system updates and antivirus software. More specific to BYOD, mobile device management (MDM) software can be implemented on the personal tools of employees to improve the security of organizational data. Employees willing to connect to the corporate network can also be granted a restricted access to a “guest” network. Finally, new software solutions, such as cloud access security brokers (CASBs), can provide security for remote workers who are increasingly accessing applications and data in the cloud (Gartner, 2019), especially when working with their personal devices from home (Bitglass, 2020; Papagiannidis et al., 2020). However, better protective technologies are not sufficient (Williams, Wynn, Madupalli, Karahanna, & Dunkan, 2014) to efficiently mitigate BYOD-related security issues; protective behaviors and attitudes are also important (Aurigemma & Mattson, 2019; Balapour et al., 2020). Some security measures can directly affect the company’s management and thus require organizational reflection (Brodin, 2016) and management’s decision making (Jeong, Lee, & Lim, 2019). Hence, managers can also intervene in corporate culture to trigger changes in attitudes toward more compliant and secure employee behaviors. These changes can be initiated by teaching individuals how to improve their security behaviors (Balapour et al., 2020; White, Ekin, & Visinescu, 2017) and awareness-raising campaigns. Employees can be also driven to sign a BYOD-specific charter (Harrington, 1996), specifying the particular risks arising from the use of personal mobile tools, stating responsibilities and explaining what to do in case of device loss, theft or breakdown, for example. Regarding opportunities, to mitigate threats, previous research has unscored the essential impact of TMS on information security behaviors (Barlette & Jaouen, 2019; Herath, Herath, & D’Arcy, 2020; Hu et al., 2012; Puhakainen & Siponen, 2010).

Moreover, Baillette and Barlette (2018) highlighted a twofold security paradox for managers generated by BYOD. The authors show that the perception of BYOD opportunities, i.e., the numerous benefits of BYOD via reversed adoption, outweighs the threats involved. The authors argue that managers overlook BYOD ISS-related issues through either a misperception of the risks or the erroneous feeling that their company is sufficiently protected. Hence, despite a strong concern over ISS, managers may primarily consider the advantages of BYOD without necessarily implementing the required protective actions.

Therefore, the necessity for managers to address BYOD-related opportunities and threats deserves more attention. However, there has been a lack of research about opportunity appraisal and its consequences for behaviors, mainly regarding managers (Baillette et al., 2018). Academic research has also been scarce about threat appraisal and how managers can address information security threats. The previous literature has repeatedly examined ISS-related employee behaviors, including adoption by employees of more secure behaviors, such as antivirus updates, backups (Boss, Galletta, Lowry, Moody, & Polak, 2015) or behaviors related to compliance with ISS policies (D’Arcy & Teh, 2020; Karjalainen, Sarker, & Siponen, 2019; Moody, Siponen, & Pahnila, 2018; Yazdanmehr & Wang, 2016) including theories such as deterrence theory (Xu, Lu, & Hsu, 2020). The behavioral research has integrated threat appraisal as a particularly influencing construct to consider. For instance, threat appraisal has been included as a building block in technology threat avoidance theory (TTAT, Liang & Xue, 2010), the health belief model (HBM, Ng, Kankanhalli, & Xu, 2009) and protection motivation theory (PMT, Rogers, 1983; Crossler, Andoh-Baidoo, & Menard, 2019; Wall & Warkentin, 2020). Business managers are the ultimate decision makers in resource allocation in ISS (Menon & Siponen, 2020). In addition, their decisions are very specific because they are primarily based on preventing loss, the best outcome being that “nothing happens” (Menon & Siponen, 2020). However, the ISS literature has rarely focused on manager behavior (Berry & Berry, 2018; Fielder, Panaousis, Malacaria, Hankin, & Smeraldi, 2016) and on their important role in developing and implementing protective measures, regulations or an ISS culture (Barlette, Gundolf, & Jaouen, 2017; Dojkovski, Lichtenstein, & Warren, 2007; Feng, Zhu, Wang, & Liang, 2019; Indihar Štemberger, Manfreda, & Kovačič, 2011).

Hence, while BYOD entails crucial issues in terms of decision-making to address or not the related opportunities or threats, the interest of the academic research remains recent and has mainly focused on theoretical approaches (Leclercq-Vandelannoitte & Bertin, 2018). Hence, more empirical studies are required to explore how managers can address BYOD adoption by employees (Baillette et al., 2018). The CMUA constitutes a relevant theoretical framework to investigate managers’ behaviors related to the perception of opportunities and threats when they become aware that BYOD has been introduced in their company by employees.

2.2. The CMUA framework

Beaudry and Pinsonneault (2005) based their coping model of user adaptation (CMUA) on Lazarus’ (1966, 2000) coping theory from the psychology literature. Coping theory describes the process by which individuals cope with disruptive events in their environment such as the introduction of a new IT (Fang, Benamati, & Lederer, 2011a; Fang, Benamati, & Lederer, 2011b). Coping corresponds to “the cognitive and behavioral efforts exerted to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 141). Internal demands relate to personal desires or obligations (e.g., need for achievement), and external demands are imposed by the external environment (e.g., social pressures). Such demands can be considered disruptive events if they exceed one’s resources to manage them (Bhattacherjee, Davis, Connolly, & Hikmet, 2018; Elie-Dit-Cosaque & Straub, 2011).

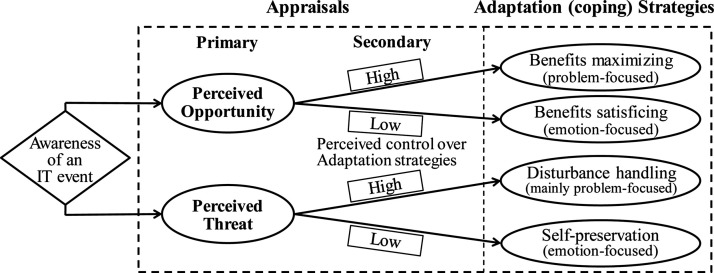

Beaudry and Pinsonneault (2005) adapted the coping theory to investigate behaviors that occur before, during, and after an IT event. The CMUA postulates that the perception of an IT event triggers adaptive behaviors, based on two key subprocesses. The primary appraisal consists of assessing the potential consequences and the personal significance of the event, perceived as a threat and/or an opportunity (Folkman, 1992). The secondary appraisal corresponds to the evaluation of the coping strategies available that will guide the individual’s choice. This choice will depend on the individual’s level of perceived control over the situation. Further studies have since confirmed the insights offered by the CMUA (Bhattacherjee et al., 2018; Elie-Dit-Cosaque & Straub, 2011). The CMUA itself is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Original CMUA model (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005).

To better contextualize the four coping strategies in this research, we define the individual of interest as the manager. The IT event that we address corresponds to when managers become aware of BYOD usage by employees within the firm. They personally assess the threats and opportunities related to BYOD for their organizations (primary appraisal). The situation that we explore consists of the personal decisions of managers to implement organizational measures to address this BYOD usage (coping strategies). The secondary appraisal corresponds to the manager’s perceived control over the situation and its organizational outcomes, either to maximize the benefits or to reduce the threats stemming from the usage of BYOD.

2.2.1. Primary appraisal

Primary appraisal begins when an individual becomes aware of the potential consequences of an IT event and assesses its personal and/or professional relevance and importance (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005; Folkman, 1992). For example, individuals may think that a new tool (hardware or software) will improve their efficiency or their ability to interact with others; thus, they may integrate that new hardware or software into their work routines, which may require (self-)training in the use of the new tool. However, this new tool will appear to be a threat to individuals if they feel insufficiently skilled to use it or if its use may endanger their privacy. Most IT events are multifaceted, and an individual may consider them threats, opportunities or both (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005). In the latter case, it is their relative importance that will influence the choice of adaptation efforts to be made (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Some elements may influence this assessment such as whether the tool is perceived as concrete or the potential criticality of the consequences of its use. Similarly, the level of ‘task-technology fit’ or expected performance may result in a negative (if it is low) or positive (if it is high) perception. This primary appraisal leads to a secondary appraisal (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

2.2.2. Secondary appraisal and the four coping strategies

The individual’s perception of an IT event as beneficial and/or threatening (i.e., primary appraisal) is followed by the evaluation of the available options (i.e., secondary or coping appraisal), which guide the choice of coping strategies. The CMUA identifies four coping strategies (Table 1 ), reflecting the coping efforts required to reduce the emotional stress resulting from the situation and adapt to this situation (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005, 2010). The choice of strategies is based on the individual’s level of perceived behavioral control (low or high).

Table 1.

The four coping strategies.

| Control | Low | High |

|---|---|---|

| Appraisal | (emotion-focused) | (mainly problem-focused) |

| Opportunity | Benefits satisficing | Benefits maximizing |

| Threat | Self-preservation | Disturbance handling |

(Adapted from Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005).

A high level of perceived control will cause the individual to adopt mainly problem-focused (i.e., active) coping strategies (benefits maximizing and disturbance handling). Conversely, a low level of perceived control will mainly cause the individual to adopt emotion-focused (i.e., rather passive) coping strategies (benefits satisficing and self-preservation). Interestingly, while problem-focused strategies (i.e., “active” behaviors) have often been investigated, emotion-focused strategies (i.e., “passive” behaviors) remain under-researched (Liang, Xue, Pinsonneault, & Wu, 2019).

The benefits maximizing strategy occurs when managers perceive the IT event (i.e., BYOD usage by employees) as beneficial, and their perceived control over the coping options available is high. In this case, managers feel able to manage the use of BYOD by their employees. Therefore, managers adopt a problem-focused coping strategy, and they aim to maximize the benefits offered by the situation. For example, managers can implement processes to maximize cost reduction, improve their companies’ efficiency and foster new ways of working through BYOD.

The benefits satisficing strategy corresponds to passively enjoying the benefits of BYOD. In this case, managers perceive BYOD usage as beneficial, and they do not feel any emotional distress, so there is no need to act to restore their psychological balance. Moreover, since managers’ perceived control is low, they will adopt emotion-focused coping strategies, such as being simply satisfied with the use of BYOD by their employees.

The disturbance handling strategy occurs when managers perceive BYOD usage as threatening, and they have a high level of perceived behavioral control. In this case, managers feel able to implement protective measures in their companies. Therefore, their coping efforts will be mainly problem focused to mitigate perceived threats and prevent potential negative outcomes.

The self-preservation strategy corresponds to the case in which managers perceive BOYD to be a potential threat, but they have limited control. They do not feel able to solve the potential problems, and this situation generates emotional stress. To restore their psychological balance, they adopt emotion-focused coping strategies, such as minimization of consequences, passive acceptance, denial and distancing themselves from the stressful situation.

3. Hypotheses development and research model

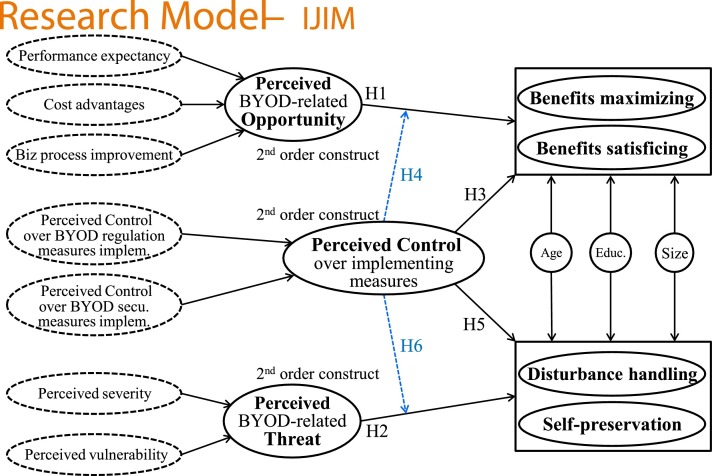

At the end of this section, the research model (see Fig. 2 3 ) provides an overview of the hypotheses.

Fig. 2.

Enriched CMUA model and hypotheses.

3.1. Primary appraisal: opportunity and threat

3.1.1. Effect of perceived opportunity on coping strategies

The previous IS research has shown that perceived benefits have a positive influence on the use of IT devices and applications (Benlian & Hess, 2011; Gupta, Yousaf, & Mishra, 2020; Kim, Jang, & Yang, 2017; Moser, Bruppacher, & Mosler, 2011; Zhou, Jin, Fang, & Vogel, 2015). According to the CMUA, the perceived opportunity of an IT event fosters the adoption of benefits maximizing and benefits satisficing strategies (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005; Elie-Dit-Cosaque & Straub, 2011).

Top management can perceive BYOD as offering valuable business opportunities and initiate IT-driven changes (Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, 2015b). Managers that perceive the most clearly BYOD-related business opportunities tend to capitalize on employees’ initiatives and to regulate and standardize their practices. A high perception of BYOD-related benefits has also been found to favor engagement behavior and satisfaction (Kim, Kim, & Wachter, 2013). Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1a-b

The perception of BYOD usage as an opportunity will positively influence the manager’s adoption of the (a) benefits maximizing strategy and (b) benefits satisficing strategy.

3.1.2. Effect of perceived threat on coping strategies

As previously underscored (see 2.1.2.), using organizational data through personal devices involves important threats related to cybersecurity and information risks (Ali et al., 2018; Baillette et al., 2018; Mustafa & Kar, 2019). Moreover, the perception of threat related to security is the central construct in the behavioral stream of research on security because it affects user intentions and behaviors (Balapour et al., 2020). The previous IS research showed that IT events perceived as threats (Lee & Larsen, 2009; Vance, Siponen, & Pahnila, 2012) cause managers to adopt more cautious behaviors (Barlette & Jaouen, 2019; Bulgurcu, Cavusoglu, & Benbasat, 2010). In the context of mobile devices, the perception of a threat exerts a positive and significant influence on the intention to implement ISS protections (Gu, Xu, Xu, Zhang, & Ling, 2017; Koohikamali, French, & Kim, 2019; Liu & Varshney, 2020; Tu et al., 2015; Wottrich, van Reijmersdal, & Smit, 2018; Zhou, Kang, Zhang, & Lai, 2016). Therefore, managers will tend to address employees’ practices, and top management expectations will correspond to problem-focused behavior, i.e., the development of clear IT policies and the implementation of BYOD-related protection measures (Jarrahi et al., 2017; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, 2015b). However, when a threat is perceived, but managers have limited control, they will adopt more passive and emotion-focused behaviors, i.e., self-preservation strategies (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005; Elie-Dit-Cosaque & Straub, 2011; Jarrahi et al., 2017). Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2a-b

Manager’s perception of BYOD usage as a threat will positively influence the adoption of the (a) disturbance handling strategy and (b) self-preservation strategy.

3.2. Secondary appraisal: influence of perceived behavioral control

As the initial CMUA model was qualitative, no indication was given about the effect of perceived behavioral control (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005). Consequently, we hypothesized that perceived behavioral control exerts direct and moderating effects on coping behavior.

3.2.1. Perceived control over addressing BYOD opportunities

This variable reflects the level of control perceived by managers over the implementation of organizational measures to benefit from the use of BYOD by employees. According to the CMUA, they can adopt problem-focused and/or emotion-focused coping responses (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005; Elie-Dit-Cosaque & Straub, 2011). When BYOD is perceived as an opportunity, and their perceived control is high, managers will mainly adopt problem-focused strategies to achieve better performance (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005; Elie-Dit-Cosaque & Straub, 2011; Harris et al., 2012), i.e., benefits maximizing strategies.

Conversely, when the behavioral control perceived by managers over the situation is low since no tension emanates from a beneficial situation (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005; Folkman, Lazarus, Gruen, & DeLongis, 1986), they will passively enjoy the advantages of BYOD use by employees, i.e., adopt an emotion-focused coping strategy corresponding to simply being satisfied. Hence, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3a-b

(direct effect): When a manager appraises a situation as an opportunity, the more perceived control that s/he has over implementing measures to regulate BYOD usage: (a) the more inclined that s/he will be to adopt a benefits maximizing strategy; and (b) the less inclined that s/he will be to adopt a benefits satisficing strategy.

Hypothesis 4a-b

(moderating effect): When a manager appraises a situation as an opportunity, the level of perceived control that s/he has over implementing regulation measures will: (a) positively moderate the relationship between the BYOD-related opportunity and the benefits maximizing strategy; and (b) negatively moderate the relationship between the BYOD-related opportunity and the benefits satisficing strategy.

3.2.2. Perceived control over addressing BYOD threats

When BYOD usage is perceived as a threat, this variable corresponds to the degree to which managers believe they can implement protective measures (Vance et al., 2012). Prior research has found that, when individuals perceive greater threats related to IT, their protection motivation increases (Li et al., 2019; Thompson, McGill, & Wang, 2017) and can result in protective and nonprotective responses (Baillette & Barlette, 2020; Moser et al., 2011). Increased coping efficacy fosters protective responses (i.e., disturbance handling strategy) (Crossler, Bélanger, & Ormond, 2019; Donalds & Osei-Bryson, 2020; Li et al., 2019) and decreases non-protective responses (Moser et al., 2011). Conversely, low levels of perceived control increase nonprotective responses (i.e., self-preservation strategy), aiming to regulate or reduce the emotional distress triggered by the threat appraisal (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005; Folkman et al., 1986; Jex, Bliese, & Buzzell, 2001; Srivastava & Tang, 2015). Consequently, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 5a-b

(direct effect): When a manager appraises BYOD usage as a threat, the more perceived control s/he has over implementing security measures, (a) the more s/he will adopt disturbance handling strategies and (b) the less s/he will adopt self-preservation strategies.

Hypothesis 6a-b

(moderating effect): When a manager appraises BYOD usage as a threat, the level of perceived control s/he has over implementing security measures will (a) positively moderate the relationship between the BYOD-related threat and the disturbance handling strategy and (b) negatively moderates the relationship between the BYOD-related threat and the self-preservation strategy.

The original CMUA in Fig. 1 has been enriched in two stages. The first stage corresponds to adding hypotheses H3 to H6 related to the effect of perceived control on the four coping strategies (Section 3.2). The second stage corresponds to adding seven constructs (dotted in Fig. 2), permitting a quantitative measurement of perceived opportunities and threats (primary appraisal) and perceived control (secondary appraisal). The details of this second step can be found in Section 4.2, which explains the construct operationalization and measures.

4. Research method

4.1. Research design

To investigate the coping strategies adopted by managers resulting from their perceptions of BYOD usage, we conducted a questionnaire-based survey. We used measurement scales borrowed from the previous literature (see 4.3.). The questions were first discussed and adapted to the BYOD context at three professional seminars held by the authors. The questionnaires were then pretested in face-to-face exchanges with managers (N = 17). Based on their feedback, through six rounds, the authors ensured the understandability and readability of the questions, mostly by removing redundancies. This process led to the final questionnaire (see Appendix A). The questionnaire was managed using the Qualtrics web-based software platform. In the questionnaire introduction, a text presented the objectives of the survey and defined the main terms (information security, personal device, BYOD, etc.). Participation in the survey was voluntary, and the authors clearly assured respondents that their responses would be treated anonymously and confidentially. We added a question to check whether managers intended to implement or had already implemented BYOD measures to address BYOD usage in their companies (Meissonier & Houzé, 2010). Although the question of period (pre- or post-implementation) is important in the MIS literature (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005; Karahanna, Straub, & Chervany, 1999; Marler, Fisher, & Ke, 2009; Taylor & Todd, 1995; Thompson, Compeau, & Higgins, 2006; Veiga, Keupp, Floyd, & Kellermanns, 2014), it does not address the issue of BYOD during these two periods. For this purpose, two slightly different sub-versions of the questionnaire were created, using the past or future tense depending on the actual or planned implementation of measures framing BYOD usage.

The questionnaire administration was outsourced to a panel company and conducted during May 2018. We chose this company because our previous collaborations were satisfying due to the company’s rigor. It has a specific division specializing in academic, quantitative and qualitative studies Hence, panel members are used to respond to scholarly questionnaires. It also uses specific methods of online data collection (CAWI in our case) and meets the standards of qualification criteria and quotas. Our criteria corresponded to the respondents’ range of ages, and positions (CEOs, top managers or executive and managers in charge of their own service/department/business units, with at least one employee to manage, with hierarchical responsibility). The respondents had to be in positions and active (non-retired) and not prohibited from BYOD usage.

Our criteria for questionnaire rejection were based on several elements. First, we removed incomplete and invalid responses. Second, all questionnaires with excessively short duration were removed because respondents may have not read and carefully answered our questions. Third we used the respondents’ IP addresses to control for duplicate submissions and to check if more than one manager had responded, for a specific location. A total of 384 responses were collected, and after applying our rejection criteria, 337 usable responses were retained.

We ensured the sample size sufficiency using the G*Power tool (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009) via a priori and post-hoc power analyses. For that purpose, we adopted a lower bound R² value of 0.10, a statistical power of 95 % and three predictors (benefits maximizing, benefits satisficing, disturbance handling and self-preservation constructs have the highest numbers of predictors). The a priori G*Power results indicated that a minimal sample size of 143 was required. In addition, the post-hoc G*Power results for a lower bound R² of 0.10, a sample size of 143, and three predictors showed that the statistical power was 0.95. These results exceed Cohen’s (1988) recommendations and support the sufficiency of our sample size.

4.2. Construct operationalization and measures

The CMUA is conceptually derived from the “coping” theory (Lazarus, 1966). However, this theory is “mute regarding what elements of a disruption are used in primary appraisal” (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005, p. 498). Therefore, to assess this primary appraisal, that is, managers’ perceptions of opportunities and threats related to BYOD usage by employees, we complemented the CMUA by adding constructs borrowed from the previous research.

To render our model more parsimonious and easier to apprehend (Hair, Sarstedt, Ringle, & Gudergan, 2018, p. 40), we created two higher-order4 constructs (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2017). Higher-order constructs allow for overcoming the jangle fallacy, and they are better predictors of broadly defined behaviors, (Hair et al., 2018).

Hence, BYOD-related opportunity and BYOD-related threat were operationalized as two higher-order constructs composed of several lower-order reflective constructs. We used the same logic to assess the secondary appraisal, based on perceived behavioral control.

These higher-order constructs were modeled as formative because they are defined by their lower-order constructs (see Fig. 2), with each lower-order construct constituting one of its facets (Lee & Cadogan, 2013; Petter, Straub, & Rai, 2007). In addition, the higher-order constructs must be modeled as formative in this case because: (a) the lower-order constructs cannot covary since the themes that they represent are distinctive (Petter et al., 2007); and (b) the lower-order constructs are not conceptually identical5 . For each of the three higher-order constructs, the corresponding lower-order constructs are presented in the following subsections.

4.2.1. Primary appraisal: measurement of BYOD-related threat

BYOD-related threat is measured using two lower-order reflective constructs, perceived severity and perceived vulnerability, borrowed from the threat appraisal constructs of another coping-based framework: the protection motivation theory (PMT) (Rogers, 1983). The PMT has been adapted to the ISS context (Aurigemma & Mattson, 2019; Lee & Larsen, 2009; Siponen, Mahmood, & Pahnila, 2014; Vance et al., 2012) and more specifically to smartphone protection (Tu et al., 2015) and smartphone-related threats (Weeger et al., 2016; Whitten, Hightower, & Sayeed, 2014).

In line with the PMT and in the context of BYOD usage, we assessed the managers’ personal perceptions of vulnerability and severity to security breaches, affecting organizational data.

-

-

Perceived vulnerability is the probability that an unwanted ISS incident (such as loss of data availability, data loss, etc.) occurs (Vance et al., 2012) if no coping behavior is undertaken.

-

-

Perceived severity is the level of the potential impact of the threat (Vance et al., 2012) resulting from insufficient or ineffective ISS measures to manage the threat. This perception of potential impacts is important when considering suitable corrective actions to implement (Mustafa et al., 2020) and reinforce the threat appraisal (Siponen et al., 2014).

In our model, BYOD-related threat appraisal corresponds to a higher-order construct composed of Perceived vulnerability and Perceived severity (see Fig. 2).

4.2.2. Primary appraisal: measurement of BYOD-related opportunity

We assessed the managers’ perceived benefits related to BYOD usage by employees as a composite formed by Business process improvement (Law & Ngai, 2007), Cost advantages (Benlian & Hess, 2011) and Performance expectancy (Moore & Benbasat, 1991; Venkatesh et al., 2003).

-

-

Business process improvement corresponds to the simplification and improvement of business practices and processes through re-engineering (Law & Ngai, 2007), resulting in tangible benefits related to BYOD usage by employees (Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, 2015a; Steelman et al., 2016). Kim, Jang, and Yang (2017) showed that this construct had a strong and significant effect on perceived opportunity.

-

-

Cost advantages: Many managers seek to take advantage of the potential benefits of BYOD usage, such as cost savings (Steelman et al., 2016). Permitting the use of BYOD allows companies to avoid buying mobile devices. In addition, companies can also save money when free or low-cost mobile consumer apps are integrated into the corporate infrastructure by employees or when employees store corporate data externally, in the cloud, for example (Weiss & Leimeister, 2012). Benlian and Hess (2011) highlighted cost advantages as the strongest driver influencing managers’ perceptions of opportunities.

-

-

Performance expectancy is “the degree to which using an innovation is perceived as being better than using its precursor” (Moore & Benbasat, 1991, p. 196). Another perceived opportunity is the increase of productivity and innovation stemming from BYOD, resulting in better performance (Tu & Yuan, 2015).

Opportunity appraisal was modeled as a higher-order construct composed of these three dimensions (see Fig. 2).

4.2.3. Secondary appraisal: measurement of perceived behavioral control

The CMUA postulates that the coping strategies depend on the perception of the event (opportunity and/or threat) and on the perceived behavioral control (high or low) over the individual’s resulting coping behavior (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005). Perceived behavioral control was modeled as a higher-order variable composed of two dimensions (see Fig. 2):

-

-

Control over BYOD regulations measures implementation: when the primary appraisal is associated with an opportunity, this perceived control relates to the implementation of processes and regulations in order to maximize the benefits of BYOD usage;

-

-

Control over BYOD-related security measures implementation: when the primary appraisal is associated with a threat, this perceived control relates to the implementation of protective measures in order to reduce either the tensions or the risks emanating from BYOD usage.

4.3. Questionnaire and scales

The questionnaire and the scales used in this research (see Appendix A) were adapted from previous studies:

-

-

The business process improvement (BPI) items were adapted from Law and Ngai (2007), the cost advantages (CA) scales came from Benlian and Hess (2011), and performance expectancy (PERF) was borrowed from Moore and Benbasat (1991);

-

-

The perceived severity (SEV) and perceived vulnerability (VULN) scales were adapted from Vance et al. (2012) and Siponen et al. (2014);

-

-

The perceived control over BYOD regulation measures implementation and over BYOD-related security measures implementation scales were adapted from Elie-Dit-Cosaque and Straub (2011) and Vance et al. (2012), respectively; and

-

-

The items used to assess the four coping strategies were adapted from Beaudry and Pinsonneault (2005); Elie-Dit-Cosaque and Straub (2011) and Workman, Bommer, and Straub (2008).

Most of the Likert-type scales we used originally contained seven-point scales. Following the advice of Goodwin and Goodwin (2016), we aligned all of our construct measurements on seven-point scales anchored at 1 (Strongly disagree) and 7 (Strongly agree). We included in the model three control variables (CVs) (see Fig. 2): Size represents the company’s size; Age represents the respondent’s age; and Education (EDUC) represents the highest degree achieved by the respondent.

In a classical top-down adoption process, implementation is decided by the company managers. We can assume that managers’ opportunity and threat appraisals may differ when BYOD is adopted by employees through a reversed adoption logic. For instance, managers can overestimate the risks before addressing BYOD usage, and their appraisal can also evolve after having experimented with BYOD adoption by employees. Meissonier and Houzé (2010) showed that managers must anticipate the outcomes resulting from the adoption of a technology. Given that individuals’ strategies and behaviors can evolve according to the pre- or post-adoption stage (Gupta et al., 2020; Meissonier & Houzé, 2010), we can hypothesize that the managers’ coping strategies can also differ before and after addressing BYOD usage in their companies. Through the variable PAST (0=Before; 1=After implementation), we assessed whether they had implemented measures addressing BYOD usage.

5. Data analysis and results

To validate the measurements and test the hypotheses, we used partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) analyses. PLS-SEM should be selected when the structural model is complex and includes many constructs, indicators and/or model relationships. In addition, our model includes one or more higher-order constructs and formatively measured constructs (Hair, Risher, Sarstedt, & Ringle, 2019, p. 5). Finally, the PLS-SEM approach has a broad scope and is flexible regarding theory and practice (Hair et al., 2019).

5.1. Descriptive statistics

The average manager’s age is 42 years old. In terms of gender, the sample was balanced (51 percent male vs. 49 percent female). The companies included 74.1 % SMEs (32.5 % very small, 22.9 % small, 19.6 % medium enterprises) and 25.9 % large enterprises. Among the 337 valid responses, 159 were before and 178 were after BYOD implementation.

5.2. Model assessment

We adopted a two-stage approach because reflective-formative higher-order constructs (HOCs) and moderator variables were part of the model (Hair et al., 2018, p. 53–54). During the first stage, the scores of the independent and moderator variables were computed. We used the repeated indicators approach to compute the scores of lower-order latent constructs (LOCs), which were added to the data set. The second stage used the LOC scores as indicators of the HOCs and built the interaction terms for the moderator variables. After this two-stage process, we assessed the measurement model; for this purpose, we ran bootstrapping with 5000 iterations to assess the path coefficients’ significance and evaluate their values (Hair et al., 2018, 2019).

Indicator Reliability and Constructs’ Internal Consistency Reliability (see Table C1 in Appendix C): All of the composite reliability values are greater than 0.7, and all of the AVEs (average variance extracted) exceed 0.5, indicating good convergent validity (Hair et al., 2019). Indicator loadings exhibited satisfactory values (see Appendix B).

Discriminant Validity (see Table C2 in Appendix C): All heterotrait-monotrait ratios of correlations (HTMT) are less than the threshold of 0.85 (Hair et al., 2019; Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015), exhibiting good discriminant validity6 .

Reflective-formative higher-order construct assessment: The two-stage approach results in weights corresponding to the path coefficients between the LOCs and their corresponding HOCs, i.e., BYOD-related opportunity, BYOD-related threat and perceived behavioral control. For LOCs, all of the tests exhibit satisfactory results (see Appendix D), showing satisfactory internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. All of the VIFs (variance inflation factors) are less than 5 (Hair et al., 2018, p. 62); hence, potential collinearity between the LOCs forming the HOCs is not problematic. Finally, all of the paths between LOCs and HOCs are positive, highly significant and relatively balanced (see Table D in Appendix D).

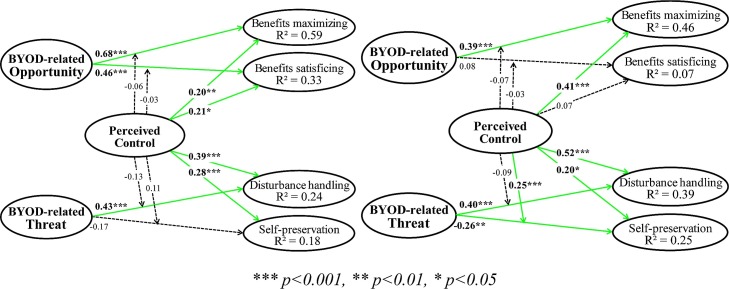

As shown in Table 2 , the full model exhibits 11 of 12 significant path coefficients. Meissonier and Houzé (2010) used a “before-after” investigation of IT pre- and post-implementation resistance. Several authors have proved the relevance of distinguishing the two stages to shed light on differences in perception between the two phases (Gupta et al., 2020; Meissonier & Houzé, 2010) and on the changes affecting coping strategies over time (Tobler et al., 2017). Hence, to analyze coping strategies related to BYOD adoption in greater depth, we distinguished between managers having actually implemented measures to address BYOD usage and those having planned this implementation.

Table 2.

Comparison of the constructs’ effects for the full sample (n = 337) and before (n = 159) and after (n = 178) implementation of measures.

| Past = 0 (159) Past = 1 (178) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructs' effects | Path Coeffs (Full) | p-values n = 337 | Path Coeffs (past = 0) | p-values n = 159 | Path Coeffs (past = 1) | p-values n = 178 | Path Coeffs Delta (past 0 vs.1) | p-values of Delta | ||

| Opportunity appraisal | Direct effects | H1a: Opportunity -> Benef Maximizing | 0.54 | 0.000 | 0.68 | 0.000 | 0.39 | 0.000 | 0.29 | 0.001 |

| H1b: Opportunity -> Benef Satisficing | 0.24 | 0.000 | 0.46 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.527 | 0.38 | 0.008 | ||

| H3a: Perceived Control -> Benef Maximizing | 0.28 | 0.000 | 0.20 | 0.001 | 0.41 | 0.000 | −0.22 | 0.024 | ||

| H3b: Perceived Control -> Benef Satisficing | 0.18 | 0.010 | 0.21 | 0.015 | 0.07 | 0.579 | 0.15 | 0.165 | ||

| Moderating effects | H4a: Perceived Control/ Opport -> Benef Maximizing | −0.08 | 0.026 | −0.06 | 0.402 | −0.07 | 0.118 | 0.01 | 0.455 | |

| H4b: Perceived Control/ Opport -> Benef Satisficing | −0.07 | 0.277 | −0.03 | 0.796 | 0.03 | 0.687 | −0.05 | 0.672 | ||

| Threat appraisal | Direct effects | H2a: Threat -> Disturbance Handling | 0.45 | 0.000 | 0.43 | 0.000 | 0.40 | 0.000 | 0.03 | 0.384 |

| H2b: Threat -> Self-preservation | −0.23 | 0.000 | −0.17 | 0.068 | −0.26 | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.237 | ||

| H5a: Perceived Control -> Disturbance Handling | 0.40 | 0.000 | 0.39 | 0.000 | 0.52 | 0.000 | −0.14 | 0.194 | ||

| H5b: Perceived Control -> Self-preservation | 0.23 | 0.000 | 0.28 | 0.001 | 0.20 | 0.043 | 0.08 | 0.286 | ||

| Moderating effects | H6a: Perceived Control/ Threat -> Disturb Handling | −0.12 | 0.050 | −0.13 | 0.070 | −0.09 | 0.237 | −0.04 | 0.652 | |

| H6b: Perceived Control/ Threat -> Self-preservation | 0.15 | 0.007 | 0.11 | 0.223 | 0.25 | 0.000 | −0.14 | 0.200 | ||

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

5.3. Multigroup analysis: distinguishing between pre- and post-implementation

We conducted a multigroup analysis distinguishing between before and after measures implementation to address BYOD usage. First, to ensure measurement invariance, we applied the MICOM procedure (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2016). We checked configural invariance and then parametric tests with 1000 permutations, which showed that compositional invariance is also established. Therefore, conducting multigroup analysis is meaningful for our study. The sample is balanced as 159 respondents (47 %) had intended to implement and 178 (53 %) had actually implemented measures in their company.

Even if all but one of the path coefficients were significant for the full sample, some of them become nonsignificant for the subgroups, due to smaller populations. Table 2 below illustrates the main discrepancies when comparing before (past = 0) and after (past = 1) implementation. The p-values in the last column indicate whether the differences between path coefficients7 before and after implementation (‘path coeffs delta’) are significant.

Below, we discuss the impact of ‘before’ and ‘after’ implementation of measures by managers on the type of coping strategies adopted, first, for the appraisal of BYOD usage as an opportunity, and, second, as a threat. Then, the explanation of R square discrepancies will provide additional insights.

5.3.1. Opportunity appraisal

After organizational measures implementation (past = 1), all but one direct effect decreases, and the moderating effects are not significant regarding the adoption of benefits maximizing and benefits satisficing strategies. The effect of perceived BYOD-related opportunity on the adoption of benefits maximizing strategies decreases (® = 0.68*** ⇨ 0.39***) but remains strong while the effect on benefits satisficing strategies (® = 0.46*** ⇨ 0.08NS) becomes nonsignificant. The influence of perceived control increases (® = 0.20** ⇨ 0.41***) for benefits maximizing strategies and becomes quasi-null for benefits satisficing strategies (® = 0.21* ⇨ 0.07NS). These results reflect that managers’ initial expectations of BYOD-related opportunities may be reduced after implementation of measures. The managers’ coping strategies aim to increase benefits, capabilities and performance (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Path coefficients and significance for Past = 0 (159 managers) and for Past = 1 (178 managers).

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

5.3.2. Threat appraisal

Regarding perceived threats, other noticeable while less significant differences appear between the two subgroups. After implementation, the effects of perceived control are much more differentiated for both the disturbance handling and the self-preservation strategies (respectively, ® = 0.52*** and 0.20*) than before implementation (respectively, ® = 0.39*** and 0.28***). The effect of perceived threat remains unchanged after implementation for disturbance handling (® = 0.43*** ⇨ 0.40***), and it becomes significantly negative for self-preservation (®=−0.17NS ⇨ -0.26**). This influence is reinforced by the moderating effect of perceived control on the relationship between threat appraisal and the adoption of a self-preservation strategy. While this effect is not significant before implementation (® = 0.11NS), it becomes much more important (® = 0.25***) after implementation.

This finding may reflect the fact that certain managers stop implementing security measures after a certain time. Interestingly, after retesting the items for the ‘after implementation’ subgroup, the most influential item is “potential risks resulting from BYOD cannot affect my company’s information security” (SP2) while “I gave up taking precautions” (SP1) becomes less relevant.

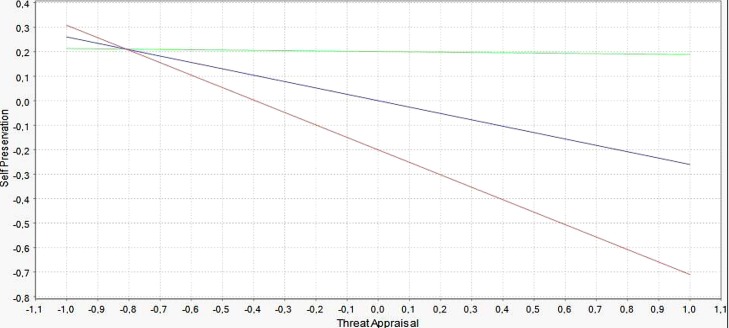

Fig. 4 represents the “simple slope analysis” of the moderating effect of perceived control on the relationship between threat appraisal and the adoption of a self-preservation strategy (®= −0.26**). Three lines correspond to moderating effect, at one standard deviation above the mean of the moderator (upper line, +1 SD, +0.25), at the mean of the moderator (central line, null effect, i.e., direct effect of threat only), and at one standard deviation below the mean of the moderator (lower line, −1 SD, −0.25), respectively.

Fig. 4.

Interaction plots for high (+1 SD) and low (-1 SD) Perceived Control over security measures implementation.

Hence, for high levels of control over the implementation of security measures, managers may believe they are sufficiently protected. This result is illustrated by the upper line in Fig. 4 (slope ∼ −0.26 + 0.25= −0.01).

In contrast, low perceived control over the implementation of security measures strongly and negatively influences managers’ self-preservation behavior. The lower line in Fig. 4 exhibits a steeper negative slope (∼−0.26–0.25= −0.51). Hence, the effect of threat combined with the moderating effect of perceived control (−0.51) compensates for the direct effect of perceived control on self-preservation (® = 0.20*). Consequently, when they perceive low control over the implementation of security measures, managers are discouraged from adopting self-preservation strategies.

All these discrepancies exert cumulative effects on the R square values for the adopted coping strategies (see Table 3 ).

Table 3.

R square discrepancies before and after implementation.

| R square (past = 0) | R square (past = 1) | Delta R² | p-Value Delta R² | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits Maximizing | 0.59 | 0.46 | −0.13 | 0.061 |

| Benefits Satisficing | 0.33 | 0.07 | −0.26 | 0.005 |

| Disturbance Handling | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.115 |

| Self-preservation | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.388 |

5.3.3. Analysis of r square discrepancies

The most significant result is the vast decrease in the explanatory power of the model for the benefits satisficing strategy (R² = 0.33 ⇨ 0.07) after implementation. This result is explained by the influences of opportunity appraisal and control over implementation in the adoption of benefits satisficing strategies that were strong before implementation and became nonsignificant after (® = 0.46*** ⇨ 0.08NS and ® = 0.21* ⇨ 0.07NS, respectively).

Referring to the enriched model (see Fig. 2), performance expectancy, cost advantages, and business process improvement become insufficient to satisfy managers. Concretely, maximizing the use of BYOD in their companies becomes their main purpose.

We can assume that after implementation, managers are less engaged in benefits satisficing strategies. The explanatory power of the model before implementation is higher because of high expectations as reflected by the stronger impact of opportunity appraisal.

After implementation, the explanatory power for taking security measures increases (for disturbance handling, R² = 0.24 ⇨ 0.39), mainly due to the increase in perceived control over implementation. For self-preservation, the explanatory power also increases (R² = 0.18 ⇨ 0.25), mainly due to the higher moderating effect of perceived control over implementation on the relationship between threat and the self-preservation coping strategy. We can assume that some managers, while having more control over the implementation of security measures, adopt more passive strategies because they think they have reached a satisfactory level of security.

After computing the average value of both perceived control variables, it is clear that before implementation, perceived control is below average8 whereas it increases after implementation (See Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Average value of perceived control constructs before and after implementation.

| Before | After | |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived control over regulation measures implementation | 3.83 | 5.04 |

| Perceived control over security measures implementation | 3.48 | 4.49 |

In our overall model, we noted that while exhibiting strong and significant values, the results for H3b, H5b and H6b were all opposite to what was hypothesized; hence, these hypotheses were not supported. The examination of Table 2, Table 4 allows us to provide another explanation that relativizes our initial hypotheses. We observed that the perception of a threat discourages the adoption of self-preservation strategies (more passive) and encourages the adoption of disturbance handling strategies (i.e., implementing security measures). In contrast, perceived control tends to foster (direct and moderating effects) self-preservation strategies. The higher overall influence of perceived control may reflect the fact that, after the implementation of security measures, managers tend to presume a high level of security, as reflected in both retained indicators for the self-preservation strategy: the “potential risks resulting from BYOD cannot affect my company’s information security” (SP2); therefore, “I gave up taking precautions” (SP1).

Consequently, we can assume a “stop-and-start process” restarted by the threat appraisal, which leads to the implementation of information security measures (disturbance handling strategies), results in higher perceived control, and leads to a (false?) sense of immunity, after which no more precautions are implemented (self-preservation strategies). However, the perception of new threats restarts the implementation of new security measures; hence, a cycle is quite possible.

5.4. Common method bias (CMB) assessment

Our results could be subject to common method bias since the survey data were self-reported, and behavior was not actually measured since it resulted from self-assessments by managers (Straub, Limayem, & Karahanna-Evaristo, 1995). Consequently, we adopted the following measures to assess and minimize potential CMB. First, we integrated the a priori procedural remedies recommended by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff (2012). We used pre-tests to improve our scale items and reduce potential ambiguities, and we broke the routine of questions based on Likert scales by regularly including multiple-choice questions. Second, the path coefficients of the structural model exhibit different levels of significance. Third, we applied Lindell and Whitney’s (2001) correlational approach. Hence, we included in our model the blue attitude construct as an a priori “ideal” marker variable (MV) (Simmering, Fuller, Richardson, Ocal, & Atinc, 2015, p. 491), which is theoretically uncorrelated with the other variables included in the model (see Appendix A). The results (see Appendix E) show that the highest correlation between the MV and the latent variables included in our model is 3.46 %, which is far less than the threshold of 9 % (Siemsen, Roth, & Oliveira, 2010). These three elements allow us to believe that CMB is not a critical issue in our study.

6. Discussion

6.1. Implications for theory

The effectiveness of BYOD-related changes depends not only on users’ acceptance but also on how managers react to and incorporate employees’ initiatives to introduce and use their own devices for business purposes (Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, 2015b). This research builds on this issue and makes several theoretical contributions.

First, our results show that adopted behaviors exhibit significant differences before and after implementation. Before implementing regulating measures, managers can have overrated expectations related to BYOD benefits, and after implementation, these expectations diminish, making way for greater influence of control over implementation, with a positive effect on benefits maximizing strategies and negative effects on benefits satisficing strategies. Hence, after implementation, perceived opportunity only fosters benefit maximization, and benefits satisficing strategies are abandoned. After implementation, the threat appraisal fosters disturbance handling and restrains self-preservation strategies. A stop-and-start process occurs whereby managers implement security measures, gain perceived control and tend to stop implementing other security measures until new threats are perceived. In addition, the explanatory power of our models is increased after the implementation of coping strategies related to threats, while it decreases for opportunistic coping strategies. These results emphasize the importance of integrating pre- versus post-implementation periods into such studies. Although the previous literature has highlighted the interest of the period (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005; Karahanna et al., 1999; Marler et al., 2009; Taylor & Todd, 1995; Thompson et al., 2006; Veiga et al., 2014; Vieru & Rivard, 2014), it has not investigated the differences between BYOD-related practices before and after IT implementation. Hence, the results of this study make an interesting theoretical contribution to the existing work on MIS linked to specific and ever-growing BYOD practices.

Second, we also extend the current literature on reversed IT adoption and BYOD through the investigation of managers’ adaptation strategies to cope with the BYOD phenomenon. Contrary to a classical top-down IT adoption process, BYOD leads managers to react and adapt themselves to a reversed adoption logic over which their control is limited, mainly because they do not own the devices. Their coping strategies reflect how they can address BYOD usage to maximize (or not) the benefits that they perceive —related to BYOD usage by employees— and to minimize (or not) the BYOD-related threats, depending on their own perceptions of the BYOD phenomenon and their perceived control over the regulation measures that they may/should implement.

Third, while the prior research on information security has mainly examined individual compliance and security behaviors, the current study extends this knowledge by investigating the implementation of security measures at an organizational level by managers. On the one hand, this approach provides a more holistic view of BYOD policies which is relatively scarce in the current literature focused on the BYOD usage phenomenon. On the other hand, this approach allows setting the focus on decision-makers in terms of BYOD-related policies and practices.

Fourth, our research extends the previous research on the CMUA. While Beaudry and Pinsonneault (2005) stated that an IT event could be perceived both as an opportunity and as a threat, the qualitative interviews that they conducted with 6 account managers linked each respondent with one coping strategy. Hence, this study has separately investigated opportunities and threats. However, since IT events are multifaceted and encompass both opportunities and threats, they are likely to result in distinctive adaptation strategies (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Our work extends the current research because it integrated both types of appraisals by exploring a continuum from threat to opportunity perceptions and permitted us to shed light on the resulting coping strategies. This process also allowed us to identify the differentiated impacts of opportunities and threats on the corresponding strategies. A quantitative study from Elie-Dit-Cosaque and Straub (2011) addressed 168 students: the authors assessed the primary appraisal through scenarios, and the secondary appraisal (level of control) was reduced to a control/no control assessment. Since the authors used scales, they computed the means of their constructs’ indicators for each case, instead of conducting more sophisticated analyses, such as structural equation modeling. Our work confirms some of their results: When an IT event is perceived as an opportunity, we can note an important prevalence of benefits maximizing over benefits satisficing strategies. In the case of a threat, the strategies are much closer, and disturbance handling is mainly adopted in the case of high control. However, we do not confirm the link between low behavioral control and the adoption of self-preservation strategies. Several explanations can be proposed. First, the population is different (students vs. executives in charge of a team). Executives might react differently than students do. Second, they examined different strategies, with their threat appraisal leading to coping strategies related to lack of interest in new software (self-preservation) or failure to achieve better performance with this software (disturbance handling), while we focused on strategies to address information security risks (implementing measures for DH and disengagement and denial for SP). Moreover, since their scenarios could distinguish opportunities and threats, the authors could not assess a precise level for the primary appraisal. Using additional constructs for the primary appraisal measurements, we could enrich the CMUA model (see also our last and methodological implication) and obtain a more precise assessment. We contribute to the literature by showing that the primary appraisal exerts a stronger effect on the choice between coping strategies than behavioral control does (secondary appraisal). Bhattacherjee et al. (2018) used the CMUA to investigate individuals’ behaviors in the context of mandated IT use. They replaced the usual coping strategies with a typology of behaviors ranging from resistance to acceptance, which reduced the possibilities of comparison with our research. However, they confirmed that emotional and behavioral reactions can coexist and coemerge in response to IT events. Our results underscore that individuals can adopt a spectrum of different types of behaviors (problem and emotion focused) to address specific situations, even in a context of reversed IT adoption. We thus extend the prior research, which mainly considered one type of behavior, such as the intensity of (non-)compliance.

Fifth, we contribute to the literature on emotion-focused (benefits satisficing and self-preservation) strategies (Liang et al., 2019). These more passive behaviors have been seldom investigated in comparison with more active and problem-focused strategies (i.e., benefits maximizing or disturbance handling by implementing information security measures) in the context of IT adoption and in the context of ISS. Theoretical contributions on passive behavior are even more important to consider given that a company’s employees have an increasingly strong action on the choice of tools they use in a professional context. As a result, the rational proactive actions of managers give greater importance to passive behaviors according to an IT reversed adoption logic (Baillette et al., 2018; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte & Bertin, 2018; Tu & Yuan, 2015).

Finally, from a methodological point of view, this paper fully operationalizes the CMUA through structural equations and extends it through several latent constructs: using formative higher-order constructs, the CMUA was extended to opportunity appraisals with three reflective lower-order constructs borrowed from Kim et al. (2017) and Moore and Benbasat (1991) and to threat appraisals with two reflective lower-order constructs adapted from Rogers’ (1983) protection motivation theory (Siponen et al., 2014). In addition, while the prior research has been more qualitative (Beaudry & Pinsonneault, 2005, 2010; Bhattacherjee et al., 2018) or has used calculated average values to distinguish high from low control (Elie-Dit-Cosaque & Straub, 2011), we operationalized the CMUA’s “perceived behavioral control” with moderating and direct effects. Significant influences could be identified for the two types of effects with a prevalence of direct influences over moderating effects.

6.2. Implications for practice

Even if the adoption of BYOD is initiated by employees, managers are aware, but only to some extent, of the opportunities and threats associated with BYOD. Our results showed that, when anticipating BYOD adoption by employees, certain managers can expect “just” enjoying the benefits of more performance, limited expenses and improved business processes. However, after having addressed BYOD usage in their company or service, managers are more sensitive to actually maximizing these benefits. Bhattacherjee et al. (2018) showed that the perception of an IT event as an opportunity when feeling great control over the situation was also synonymous with engagement, which is very important in terms of top management support (Barlette & Jaouen, 2019; Boonstra, 2013). Hence, initially raising managers’ awareness and providing guidance regarding concrete means to optimize company performance and enhance business processes with BYOD, while reducing costs, would trigger TMS and thus save time in reaping the benefits from BYOD introduction in their companies.

On the side of BYOD-related threats, addressing the risks is harder. Even if we could identify a stop-and-start process relaunched by the threat appraisal, self-preservation behaviors corresponding to denial – “Risks cannot affect me”– and distancing – “I gave up taking precautions” (see Appendix A) still exist. These behaviors may result not only from higher perceived control over protective behaviors but also from a certain amount of overconfidence, which is common among managers. Managers may not be aware of BYOD-related security issues potentially detrimental to their companies because they are not always actually experienced (Kankanhalli, Teo, Tan, & Wei, 2003). Managers also have difficulties mastering technological innovations that they consider to be the responsibility of IT leaders. For instance, demonstrating through real-life examples the most common security issues and the actual impacts that they had on companies would help to increase managers’ perceptions of potential threats (Schuetz, Lowry, Pienta, & Thatcher, 2020). Hence, raising managers’ awareness will enhance their disturbance handling behaviors, resulting in greater information security for their firms. Managers may also make decisions to improve information security in their company by observing other organizations making the same investment decisions and mimicking their decisions (Shao, Siponen, & Liu, 2020).

Given the importance of achieving a shared understanding of information security policies and measures in companies (Samonas, Dhillon, & Almusharraf, 2020), even if managers are not technically skilled, through higher engagement and top management support (Feng et al., 2019; Indihar Štemberger et al., 2011; Kankanhalli et al., 2003), they could provide more funding and could champion the implementation of security measures, charters, training sessions or awareness-raising campaigns (Herath et al., 2020; Soomro, Shah, & Ahmed, 2016). In addition, TMS would optimize this implementation and favor the adherence of employees (Tobler et al., 2017).

6.3. Implications for policies