Abstract

Evasion of programmed cell death represents a critical form of oncogene addiction in cancer cells. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underpinning cancer cell survival despite the oncogenic stress could provide a molecular basis for potential therapeutic interventions. Here we explore the role of pro-survival genes in cancer cell integrity during clonal evolution in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We identify gains of MCL-1 at high frequency in multiple independent NSCLC cohorts, occurring both clonally and subclonally. Clonal loss of functional TP53 is significantly associated with subclonal gains of MCL-1. In mice, tumour progression is delayed upon pharmacologic or genetic inhibition of MCL-1. These findings reveal that MCL-1 gains occur with high frequency in lung adenocarcinoma and can be targeted therapeutically.

Subject terms: Non-small-cell lung cancer, Non-small-cell lung cancer

Cancer cells frequently harbour genetic aberrations that protect them from programmed cell death. Here, the authors show in non-small cell lung cancer that the anti-apoptotic gene MCL-1 is subject to copy number gains and that deletion of MCL-1 reduces tumour formation.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide1. Despite the identification of genotype-directed targeted therapies and the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors, lung cancer is still associated with substantial morbidity and mortality1.

Based on its histology, lung cancer is divided into small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with the latter representing about 85% of total cases. Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) are the most common subtypes of NSCLC2.

Approximately 33% of adenocarcinoma harbour activating mutations in KRAS3, which remain clinically difficult to target. A novel class of inhibitors against mutant KRAS has just started to be tested in clinical trials4,5, while targeting signalling elements downstream of KRAS, such as MAPK, has yielded unsatisfactory results in clinical trials6,7. Therefore, patients with KRAS-mutant lung cancer often relapse indicating a substantial unmet medical need for these patients2,4. Loss of the TP53 tumour suppressor is another common event in lung cancer3. Loss of TP53 function has been observed in 46% of lung cancer patients and is often detected in combination with additional mutations in common oncogenic drivers, such as gain-of-function mutations in the epithelial growth factor receptor, EGFR3. TP53 protects cells from tumorigenesis by activating a variety of anti-proliferative and stress-response pathways, including apoptosis, senescence, cell cycle arrest, and the coordination of DNA damage repair8,9.

Protection against programmed cell death pathways, like apoptosis, represents a critical form of oncogene addiction in cancer cells: the substantial cellular stress that cancer cells experience during their transformation and uncontrolled proliferation requires a reliance on signalling pathways that secure their continued survival10.

Apoptosis is largely regulated by a balance between pro-survival and pro-apoptotic members of the B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) protein family. Accordingly, pharmacologic inhibitors targeting pro-survival BCL-2 proteins have been developed to induce apoptosis in cancer cells11. Various malignancies show recurrent genetic amplifications affecting pro-survival members of this family. For example, analysis of somatic copy number alterations of different human cancer specimens and cell lines revealed genomic amplifications of the chromosomal region containing the anti-apoptotic gene Myeloid Cell Leukaemia 1 (MCL-1) in various cancer types12,13. Antisense oligonucleotides targeting MCL-1 were able to induce apoptosis in certain NSCLC cell lines, suggesting a functional relevance for MCL-1 in NSCLC survival14,15. However, little is known about the role of MCL-1 during lung cancer clonal evolution and maintenance.

We provide evidence that the selective pressure for the evasion of apoptosis during tumour evolution results in recurrent genomic gains of MCL-1 with high frequency in NSCLC patients. Functionally, we demonstrate that Mcl-1 deletion impairs the development of Kras-driven tumour and that pharmacologic inhibition of MCL-1 in fully established Kras-mutated p53-deleted murine lung cancers slows tumour progression. Together, these data identify MCL-1 as a rational target for the treatment of NSCLC patients.

Results

Genomic and protein gains of MCL-1 in lung cancer

To understand the preponderance of genomic gains of the pro-survival gene MCL-1 in cancer, we analysed genomic data of 24 different cancer entities from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). In line with previous data12,13, MCL-1 was significantly gained and highly expressed in 22 cancer types (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. Genomic MCL-1 gains in cancer.

a Number of significantly gained and expressed genes located on chromosome arm 1q in the TCGA cohort. The bars pointing to the right demonstrate the number of significant genes identified in up to 1 to 24 cancer types (right bars). The numbers are represented as cumulative counts, which means that genes significant in two cancer types were also counted in for one cancer type. MCL-1 was found to be significantly gained and expressed in 22 cancer types among 140 other genes. b MCL-1 gains (CNA, copy number aberrations) in TCGA LUAD samples. LLG low-level gain, HLG high-level gain. n = 652. c Correlation between MCL-1 CNA and mRNA levels in TCGA LUAD samples. n = 456 (289 gain and 167 no gain, p = 1e−07, W = 17,081). d MCL-1 gains (CNA) in TCGA LUSC samples. n = 652. e Correlation between MCL-1 CNA and mRNA levels in TCGA LUSC samples. n = 441 (164 gain and 277 no gain, p = 1.6e−04, W = 18,066). f, g CNA expressed as frequency in TRACERx LUAD (f, n = 61) and LUSC (g, n = 32) tumours. Shading indicates clonal status. Dashed purple lines represent threshold for frequent gains and losses. h, i Correlation between CNA and mRNA levels of MCL-1 in TRACERx LUAD (h) and LUSC (i) tumour regions. For LUAD, n = 93 (60 gain and 33 no gain, p = 0.017, W = 1256). For LUSC, n = 50 (22 gain and 28 no gain, p = 0.0028, W = 448). Data in (c, e, h, and i) are presented as box plot and were analysed by a one-sided Wilcoxon test. In the box plots, the centre line represents the median value, the limits represent the 25th and 75th percentile, the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum value of the distribution excluding outliers defined by the inter-quartile range (IQR) rule. The points represent the individual experimental values.

We further analysed the TCGA dataset for LUAD and LUSC in order to specifically understand the role of MCL-1 in lung cancer. Analysis of LUAD samples revealed MCL-1 gains in 417 out of 652 LUAD samples (64%), of which 70/417 (11%) were high-level gains (>2 × ploidy, Fig. 1b). We detected a positive correlation between MCL-1 genomic gain and mRNA levels (Fig. 1c), suggesting a functional significance of the genomic gains. Analysis of LUSC samples showed MCL-1 gains in 211 out of 652 samples (32%), of which 28/211 (4%) were high-level (Fig. 1d). Although MCL-1 was less frequently gained in LUSC, we still identified a consistent correlation with its mRNA levels (Fig. 1e).

To further dissect the impact of MCL-1 in lung cancer, we took advantage of the TRACERx study16 (patient information in Supplementary Fig. 1). Analysis of LUAD samples revealed MCL-1 copy number gains in 46/61 (75%) tumours, of which 10/46 (22%) were high-level (Fig. 1f). Similar results were detected in LUSC tumours, 19/32 (59%) tumours showed MCL-1 gains and 1/19 (5%) was classified as a high-level gain (Fig. 1g). MCL-1 maps to the human chromosome 1q21, a region that is frequently altered in pre-neoplastic lesions and malignant diseases17. Analysis of the size of genomic segments affected by copy number alterations revealed that MCL-1 is subject to both focal and broad level gains, with focal events (<20 Mb) exhibiting a higher preponderance of high-level gains compared to broad ones (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The correlation between genomic gain and mRNA levels was confirmed in these cohorts (Fig. 1h, i). A similar relationship was observed for additional 316 genes for LUAD and 276 genes for LUSC located on chromosome 1 (Supplementary Data 1–2 and Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). This suggests that the gain of this genomic segment impacts upon the expression of a large set of genes, including 14 genes that have been previously linked to cancer (Supplementary Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 1). However, MCL-1 falls within the peak of frequently gained segments on 1q21 identified by GISTIC2 of the TRACERx LUAD data (−log10(q value) = 4.03, Supplementary Fig. 3d, e). No significant peak on 1q21 was detected in TRACERx LUSC tumours. For this reason and due to its higher incidence2, we focused on MCL-1 gains in LUAD.

LUAD encompasses 40% of the lung cancer patients and its 5-year overall survival across all subgroups rate averages at only 18%18, highlighting the need of a better understanding of its molecular mechanisms in order to design new therapeutic approaches. First, we analysed MCL-1 genomic gains during tumour evolution, taking further advantage of the TRACERx study. Notably, the design of this prospective study allows the analysis of intra-tumour heterogeneity and the evolutionary trajectory of tumour genomes (Supplementary Fig. 4a). We detected clonal MCL-1 amplifications in 34/46 (74%) LUAD (e.g. CRUK034, Supplementary Fig. 4b). In 12/46 (26%) adenocarcinomas, MCL-1 gains appeared subclonally on the branches of the tumour’s phylogenetic trees (e.g. CRUK001, Supplementary Fig. 4c). Given its relatively high frequency as a late event, these data suggest that the overall frequency of MCL-1 gains may be underestimated.

We then classified the LUAD samples according to TP53 status (mutant vs wild-type, Fig. 2a, b) and explored MCL-1 genomic gains in these cohorts. While the total (clonal and subclonal) MCL-1 gains were not different in these cohorts, we detected a higher frequency of subclonal events in the TP53 mutant cohort (Fig. 2c). To further analyse whether TP53 mutational status affects other genes located on chromosome 1q21, we analysed the segment size detecting no significant differences (Fig. 2d). The same analysis performed for mutant KRAS and EGFR showed no differences (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Fig. 2. TP53 mutation associates with subclonal MCL-1 gains.

a, b CNA expressed as frequency in TRACERx LUAD grouped for TP53 wild-type (WT) (a) and mutant (b). Shading indicates clonal status. n = number of patients. c Frequency distribution of MCL-1 gain in TP53 wild-type or clonal mutant TRACERx LUAD patients. Data were analysed by Pearson’s chi-squared test with continuity correction (p = 0.007, chi-square(2) = 9.885). d Comparison of MCL-1- segment sizes between clonal and subclonal MCL-1 gains for TP53 mutant and WT samples. Two-sided Wilcoxon testing showed no significant differences. TP53 mut n = 54 (34 clonal and 20 subclonal gains, p = 0.89, W = 348) TP53 WT n = 69 (57 clonal and 12 subclonal gains, p = 0.53, W = 302). n = number of samples. The data are presented as box plot, where the centre line represents the median value, the limits represent the 25th and 75th percentile, the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum value of the distribution, and the points represent the individual experimental values.

To confirm MCL-1 genomic gains in a different cohort, we used fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) with MCL-1 probes on two tissue microarrays (TMA) of 56 and 24 primary human LUAD tissue samples. FISH analysis revealed polysomies of chromosome 1q21 and high- and low-level gain of MCL-1 in 48.8% of the samples (Fig. 3a, b). We analysed MCL-1 protein levels in the second TMA, detecting a strong staining intensity for 10 out of 25 (40%) samples and an intermediate staining intensity in 10/25 (40%) (Fig. 3c–e). Due to the restricted sample size no significant correlation was detected between MCL-1 genomic gains and MCL-1 protein expression (Fig. 3f). However, none of the samples showing MCL-1 high- or low- level gain by FISH had a weak MCL-1 protein staining intensity (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 3. MCL-1 is over-expressed in human LUAD.

a, b Quantification of FISH analysis for MCL-1 in LUAD TMA in all the samples (a) or divided by grade (b). n = 80. HLG high-level gain, LLG low level gain. c, d Representative images (c) and quantification (d) of MCL-1 staining in TMA of LUAD (n = 25). MCL-1 staining intensity was assessed and classified as low, intermediate (int.), or high. e Comparison of MCL-1 staining intensities between different histological grades of LUAD (G2, n = 13; G3, n = 12). Data were analysed with the Pearson’s chi-squared test with continuity correction (ns, p = 0.0930, chi-square(2) = 4.750). f Association between FISH and IHC analyses on TMA samples. A two-sided Fisher’s exact test was applied as statistical test (ns, p = 0.75). g–h Representative images (g) and quantification (h) of MCL-1 staining in LUAD and paired normal tissue (n = 11). Data were analysed by Pearsonʼs chi-squared rest with continuity correction (p = 1.385E−36, chi-square(4) = 174.1). Scale bar is 1 mm or 100 µm. BE bronchial epithelium.

To understand whether MCL-1 is differentially expressed in cancer vs healthy tissue, we analysed MCL-1 protein levels in 11 primary LUAD patient samples and matched healthy lung tissue. Notably, MCL-1 expression intensity was significantly higher in LUAD tissue than in healthy adjacent tissue (Fig. 3g, h). These results are consistent with previous reports on MCL-1 protein abundance in lung cancer14,19,20.

Taken together, these data indicate that MCL-1 clonal and subclonal gains correlate with higher MCL-1 mRNA and MCL-1 protein levels and frequently occur in human pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

Dissecting MCL-1 role in lung cancer-cell line survival

To test whether MCL-1 gain represents a common feature also in cell lines, we first took advantage of online available data (COSMIC Cell Lines Project). We detected MCL-1 genomic gains, which correlated with high MCL-1 mRNA levels in the entire cohort of LUAD cancer-cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Then, we used 11 different human NSCLC-derived cell lines (9 LUAD and 2 large cell cancer, characteristics reported in Supplementary Table 3) to test for a functional role for MCL-1 in cancer-cell survival. Genomic DNA was extracted from all the cell lines and used for sequencing and gene copy number analysis to identify genomic gains of chromosome 1q21 and specific gains of MCL-1. We detected a correlation between MCL-1 genomic gains, MCL-1 mRNA, and MCL-1 protein levels. This correlation was even stronger, when we focused our analysis only on LUAD cell lines (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 7).

Fig. 4. MCL-1 secures survival of lung cancer derived cell lines.

a MCL-1 copy number variation, MCL-1 mRNA, and MCL-1 protein levels in the cell lines used for this study. Data in the bottom panel are presented as mean ± SEM. b Relative viability of the indicated cell lines after 72 h treatment with 5 µM S63945, as determined by CellTiter-Glo®. Results were normalised to vehicle treated (control) cells. c Simple linear regression between MCL-1 protein levels (AU, arbitrary units) and cell viability after S63945 treatment (dashed lines 95% confidence interval; R2 = 0.5441, p = 0.0233). d Relative viability of the cell lines after 72 h treatment with 3 µM ABT-737, as determined by CellTiter-Glo®. Results were normalised to vehicle treated (control) cells (one-way ANOVA p = 4.540E−6, F(2,26) = 20.49). e Relative viability of the indicated cell lines 24 h after induction of the expression of the different BIMS variants, as determined by FACS analysis. Percentage of viable untreated cells was assigned as 100% (one-way ANOVA: NCI-H358: p = 2.317E-12, F(3,24) = 75.45; NCI-H1975: p = 1.354E−13, F(3,24) = 97.82; NCI-H2170: p = 3.334E–12, F(3,20) = 70.48). In figure are reported the p value from the post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction. Data in panel (b, d, and e) are presented as box plots, where the centre line represents the median value, the limits represent the 25th and 75th percentile, and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum value of the distribution, excluding outliers defined using the IQR rule. Each cell line was assayed at least in three independent experiments.

To examine the functional role of MCL-1 in cancer-cell survival, we treated LUAD cell lines with S6384521, a selective MCL-1 inhibitor. Notably, the cytotoxicity of S63845 correlated with MCL-1 protein level (Fig. 4b, c).

To understand whether the other cancer-related genes identified on amplicon 1q21 (Supplementary Fig. 3c) may play a role in the sensitivity to the MCL-1 inhibitor, we analysed their expression in the cell line cohort. While we still identified a significant correlation with MCL-1 mRNA levels, none was detected for any of the other genes analysed (Supplementary Tables 4, 5).

However, MCL-1 function also heavily depends on the balance with the alternative BCL-2 family proteins. As previously shown in other cancer cohorts12,22, MCL-1 gains did not elicit compensatory dysregulation of other BCL-2 family members in LUAD, irrespective of the cohort analysed (TRACERx or TCGA, Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). We used a pharmacological and a genetic approach in three representative cell lines (NCI-H358, NCI-H1975, and NCI-H2170) to dissect cancer-cell susceptibility to inhibitors of different pro-survival BCL-2 family members. Within these cell lines, we observed a heterogeneous expression pattern of pro-survival BCL-2 proteins: BCL-XL was highly expressed in all cell lines, while MCL-1 and BCL-2 protein levels were variable (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Specifically, NCI-H358 and NCI-H1975 expressed higher MCL-1 levels compared to NCI-H2170. Treatment with ABT-737, a BH3 mimetic able to inhibit BCL-2, BCL-XL, and BCL-W, but not MCL-1, was highly effective in killing the cell lines with low MCL-1 levels (Fig. 4d).

Next, we took advantage of mutant versions of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein BIM. We used doxycycline-inducible expression vectors for four different BIM variants, which are engineered to block: (i) MCL-1 only (BIMS2A), (ii) BCL-2, BCL-XL, and BCL-W (BIMSBAD), (iii) none of the pro-survival BCL-2 proteins (BIMS4E, negative control), or (iv) all pro-survival BCL-2 proteins (BIMSWT, positive control)23. We found that the MCL-1-specific version BIMS2A was significantly more potent in both of the high-MCL-1 cell lines compared to the joint BCL-2, BCL-XL, and BCL-W inhibitor (BIMSBAD). Conversely, in the low-MCL-1 cell line (NCI-H2170) BIMSBAD was more effective than BIMS2A in eliciting cell death (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 8d, e). As expected, BIMSWT was the most effective in inducing apoptosis in all cell lines tested. This suggests that the survival of these lung cancer-cell lines is safeguarded by two or more pro-survival BCL-2 proteins with MCL-1 or BCL-XL being the dominant factor. While we suggest that these effects are driven by the differences in MCL-1 expression, we cannot exclude the involvement of the different histological subtypes (LUAD for NCI-H358 and NCI-H1975 and LUSC for H2170).

Taken together, these data suggest that whenever MCL-1 is highly expressed it becomes critical for the sustained survival of lung cancer cells.

Genetic deletion of Mcl-1 impedes lung tumorigenesis in vivo

We hypothesised that genetic deletion of Mcl-1 would impair with lung tumorigenesis in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we utilised mice harbouring loxP-flanked Mcl-1 alleles for the conditional deletion of Mcl-124. Mcl-1 deletion after adenoviral Cre delivery did not elicit any phenotype in the healthy lung (Supplementary Fig. 9). These mice were crossed to lsl-KrasG12D/+ mice, in which mutant Kras is conditionally expressed in cells after recombination of the lox-stop-lox (lsl) cassette25. We infected lsl-KrasG12D/+ Mcl-1fl/fl and respective controls intra-nasally with adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase (AdCre). In AdCre infected pulmonary epithelial cells, Cre recombinase induces, at the same time, the expression of oncogenic KrasG12D and the deletion of Mcl-1. We performed all the analysis 19 weeks after AdCre infection (Fig. 5a). Genetic deletion of Mcl-1 was confirmed by RNA in situ hybridisation and genomic DNA analysis of primary cultures from tumour lesions (Fig. 5b, c and Supplementary Table 6).

Fig. 5. Pro-survival Mcl-1 is critical for LUAD development.

a Experimental design. b, c Representative images (b) and quantification (c) of Mcl-1 mRNA in situ hybridisation in lesions and adjacent healthy tissue. Inserts are higher magnification of corresponding images. n = number of lesions. Data were analysed by one-way ANOVA (p = 6.600E−9, F(2,39) = 31.73, p values from post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction are reported in figure. d Representative H&E staining of lung tissue sections at 19 weeks after AdCre virus infection. Inserts are higher magnification of indicated areas. Scale bar represents 2 mm, 1 mm, 100 µm, or 10 µm. e Number of lesions per section. n = number of sections. Three sections per animal, separated by 100 µm, were assessed. Data were analysed by Kruskall–Wallis test (p = 5.544E–6, p values from post-hoc analysis with Dunn’s correction are reported in figure). f Representative renderings of the µ-CT analysis. g Quantification of tumour volume expressed as percentage of the lung volume. n = number of mice. Data were analysed by one-way ANOVA (p = 0.0145, F(2,10) = 6.656, p values from post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction are reported in figure). Data in panel (c, e, and g) are representative of four independent experiments and are presented as dot plot and show mean ± SEM. h Representative images of pulmospheres generated from dissected tumour tissue (2 lesions from 2 mice/genotype). Inserts showing individual pulmospheres. Scale bar is 25 µm or 100 µm. i Quantification of pulmosphere area (µm2) over the cultivation period. n = number of pulmospheres. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and were analysed by repeated measure two-way ANOVA (for time, genotype, and interaction effects, p < 0.0001). p values from post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction are reported in the panel (**p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001).

To analyse the impact of Mcl-1 deletion on tumour development, we quantified the number of lesions in all the experimental groups. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that the deletion of Mcl-1 caused a significant reduction in KrasG12D driven malignant lesions compared to animals in which Mcl-1 was not deleted (Fig. 5d, e). This was further confirmed by contrast agent-enhanced high-resolution computed tomography imaging (μ-CT) of tumour-burdened lungs (Fig. 5f, g). Notably, the changes in tumour burden were not accompanied by detectable changes in the proliferation rate across genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). There was also no increase in the numbers of apoptotic cells in the tumours of the different genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 10c, d). This is not unexpected, as apoptotic cells would have been rapidly engulfed by phagocytic cells soon after the loss of MCL-1 protein, masking the effect of Mcl-1 deletion at this late time point. Loss of Mcl-1 did not affect the histological features of the proliferative lesions, such as surfactant protein (SP)-C, CC10, and mucin (Supplementary Fig. 10e–g).

To further examine the role of Mcl-1 in lung tumorigenesis, we analysed pulmonary organoid cultures (termed pulmospheres) generated from all the experimental groups ex vivo. Of note, even loss of a single Mcl-1 allele was sufficient to prevent pulmosphere growth over several days in culture (Fig. 5h, i).

Taken together, these data show that MCL-1 is required for the survival of lung cancer cells.

MCL-1 inhibition delays adenocarcinoma progression in vivo

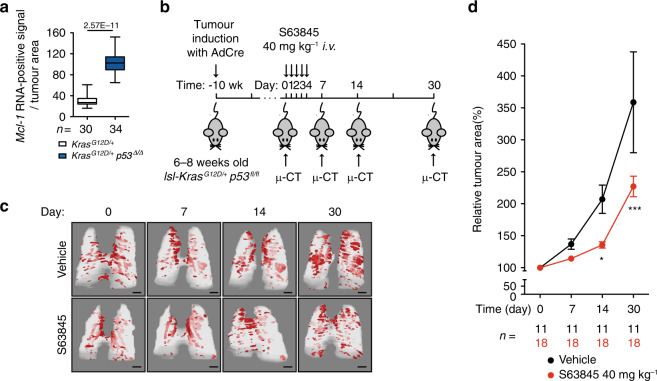

Finally, to evaluate the potential of MCL-1 as a druggable target, we treated tumour-bearing mice with the MCL-1 inhibitor S6384521. To strengthen the potential clinical translation, we used the highly aggressive model of lung cancer driven by a Kras-mutation in combination with p53-deletion. In line with the human data, we detected an increase in Mcl-1 mRNA expression in p53 deleted lesions compared to p53 WT lesions (Fig. 6a). Previous reports showed efficacy and tolerability of S36835 in the treatment of Eμ-Myc lymphoma21 and triple negative (ER/PR/ERBB2 negative) breast cancer xenografts26, the latter suggesting a favourable pharmacokinetic profile, also in solid tumour. Notably, in vivo S36835 treatment was shown to be tolerated even in combination with chemotherapeutics27. lsl-KrasG12D/+ p53fl/fl mice were randomly assigned to control (vehicle) and treatment groups (S63845). Starting at 10 weeks after AdCre infection, these mice were treated with 40 mg kg−1 S63845 or vehicle for 5 days. At day 0 (baseline), 7, 14 and 30, tumour progression was monitored by μ-CT, examining three to five lesions per mouse (Fig. 6b). We observed a significant reduction in tumour size in the treated group compared to the vehicle control group after 14 and 30 days (Fig. 6c, d). Analysis of the lung tissue for Mcl-1 genomic gains and Mcl-1 mRNA levels did not detect any significant differences (Supplementary Fig. 11a–c). This is not unexpected due to the fact that S63845 treatment has been shown to increase MCL-1 protein levels (by delaying its degradation), without affecting Mcl-1 mRNA levels21. This also indicates that the treatment (in this specific settings) did not actively select any specific clones (i.e. those expressing low level of Mcl-1). In addition, this effect was not due to differences in cell proliferation (Ki67) (Supplementary Fig. 11d, e). There was also no marked increase in cleaved caspase 3 staining, presumably because tumour cells undergoing apoptosis are rapidly phagocytosed (Supplementary Fig. 11f, g). Taken together, these data suggest that MCL-1 represents a druggable target to treat LUAD.

Fig. 6. MCL-1 inhibitor delays progression of LUAD in vivo.

a Quantification of Mcl-1 mRNA in situ hybridisation in lesions from lsl-KrasG12D/+ and lsl-KrasG12D/+;p53fl/fl mice. n = number of lesions. Data are presented as box plot and were analysed by two-sided Mann-Whitney test (p = 2.57E−11). In the box plot, the centre line represents the median value, the limits represent the 25th and 75th percentile, and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum value of the distribution. b Experimental design. Wk- week. c Representative rendering of µ-CT analysis. Scale bars represent 2 mm. d Quantification of tumour growth is expressed as percentage of the tumour volume on day 0. n = individual tumours. Three to five tumours per mouse were assessed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and were analysed by repeated measure two-way ANOVA (time effect p < 0.0001, treatment effect p = 0.001, interaction effect p = 0.0006). Post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed a significant effect for treatment at day 14 (*p < 0.05) and day 30 (***p < 0.001).

Discussion

We show that genomic gains of the pro-survival MCL-1 gene occur with high frequency during tumour evolution in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Using murine tumour models, the data provided here demonstrate the suitability of MCL-1 as a rational drug target for the treatment of pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

The chromosome locus 1q21, which harbours the MCL-1 gene, shows frequent copy number gains in lung cancer17. We confirmed these data in three independent cohorts (publicly available datasets TCGA and TRACERx, and an in-house tissue microarray). However, gain in MCL-1 co-occurred with many other genes located on amplicon 1q21. While we do not exclude the involvement of these other genes in cancer initiation and/or progression, we hypothesised that the resistance to apoptosis mediated by MCL-1 serves as a critical oncogene addiction in lung cancer and possibly other cancer entities12,22. We argue that as an addiction, tumours favour the presence of MCL-1 and, when present, they become highly dependent on it.

Gains of MCL-1 were predominantly clonal, occurring on the trunk of each tumour’s phylogenetic tree. Interestingly, we observed higher frequencies of MCL-1 subclonal gains in lung tumours following clonal TP53 mutation. This could therefore simply reflect increased chromosomal instability. However, conceivably, this could also indicate that higher levels of MCL-1 are selected for by the tumour cells in response to mounting oncogenic stress that occurs when TP53 is mutated. This notion is supported by our in vivo data, showing that Mcl-1 levels are higher in established p53 deleted tumours (compared to p53 WT tumours) and MCL-1 inhibition delays tumour progression. Taken together, these data indicate that fully established tumour lesions lacking functional p53 require, at least in part, MCL-1 for sustained survival.

In line with previous reports in alternative cancer cohorts12,22, genomic gains of MCL-1 occurred at higher frequency than any other BCL-2 family member and did not cause compensatory deregulation of other BCL-2 protein family members, as detected in the TCGA and TRACERx datasets. This has already been shown in hepatocellular carcinoma28, B cell-non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma29 and T cell lymphoma23,30,31. However, dependencies on other pro-survival BCL-2 family members may exist depending on the type of cancer and treatment used, as recently reported data on breast cancer showed a positive correlation between not only MCL-1 but also BCL-2A1 expression and an inverse association with BCL-2 expression26. Our in vitro data showed that inhibition of BCL-XL, BCL-W and BCL-2 was less effective than MCL-1 inhibition in killing cell lines expressing high levels of MCL-1, further supporting the addiction of lung tumours to MCL-1.

Notably, gains of MCL-1 were associated with a significant increase in its mRNA and protein expression (in primary samples and cell lines), consistent with functional consequences. Indeed, in vitro data showed that cell line susceptibility to MCL-1 inhibition significantly correlated with MCL-1 expression levels. While recent work showed that solid cancers respond only moderately to MCL-1 inhibitor S36835 single treatment21, we suggest that targeting MCL-1 might be an effective approach on in its own15,20. This is in line with previous reports of successful treatment with S36835 in Eμ-Myc lymphoma21 or triple negative (ER/PR/ERBB2 negative) breast cancer xenografts26. Alternatively, MCL-1 inhibition might be used to lower the apoptotic threshold in combination with other treatment strategies. In line with this notion, Nangia et al. showed that simultaneous inhibition of MCL-1 and MAPK provides better response rates in NSCLC. This approach is based on a MAPK-dependent increase in pro-apoptotic BIM, which can inhibit the non-targeted pro-survival BCL-2 family member(s) present in the tumour cells32. Our data provide evidence that LUAD exhibit elevated MCL-1 levels by genetic amplification per se and not as a result of treatment.

In summary, our data show that genomic gains of MCL-1 during lung cancer evolution represent a frequent and functionally important survival mechanism for pulmonary adenocarcinoma that represents a rational drug target for the treatment of NSCLC.

Methods

Clonal evolution of MCL-1 during lung cancer progression

To determine the clonal status of MCL-1 gains during tumour evolution, multi-region copy number data from the TRACERx study16 was used. The TRACERx study was conducted under the favourable opinion from the NRES Committee London—Camden & Islington Research Ethics Committee16. The copy number values were adjusted by ploidy and log-transformed. This leads to the identification of gains as genomic segments exhibiting a copy number state > log2(2.5/2). Gains with a copy number state > log2(4/2) were classified as high-level gains. Clonal gains were ubiquitously identified across every tumour region sequenced from a given tumour, while subclonal gains were identified as present in at least one tumour region, but not all. Based on presence or absence within individual regions, gains were mapped to previously described phylogenetic trees16. To identify significant frequent gains and losses across the cohort, the 95% quantile of the corresponding null distribution was used as a threshold. The null distributions for gains and losses respectively were calculated under the assumption that gains and losses occur randomly along the genome. A threshold of 20 Mb was used to distinguish between focal and broad gains. In order to check which of the genes located in the gained area around MCL-1 show an increase in expression, the RNAseq data from the TRACERx cohort were analysed. The mRNA levels were measured as TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million) values. A one-sided Wilcoxon test was applied to test for a significant difference between expression levels of samples with gains versus no gains. A combined list of previously reported lung cancer genes16 was used to find putative cancer genes in the significant differentially expressed genes.

Mice

The previously established lox-STOP-lox-KrasG12D (lsl-KrasG12D)25, Mcl-1floxed 24, and p53floxed33 mice were used to generate lsl-KrasG12D;Mcl-1floxed mice and lsl-KrasG12D;p53floxed mice. Mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions and assigned to experimental groups based on their genotype after birth. There were no other factors that determined group selection. All mice were housed up to five per cage at 20–22 °C, 45–60% humidity, kept on a 12‐h light/dark cycle and were given ad libitum access to food and water. We randomly assigned mice to a specific group depending only on the genotype. No mice were excluded from the statistical analyses. All animal experiments were conducted in compliance with protocols approved by the District Government of Upper Bavaria in line with the animal ethics committee guidelines (Az: 55.2-1-54-2532- 55-12 and ROB-55.2-2532.Vet_02-14-69).

TCGA data analysis

The genomic data of 24 different cancer types (BLCA, BRCA, CESC, CHOL, DLBC, ESCA, GBM, HNSC, LGG, LIHC, LUAD, LUSC, MESO, OV, PAAD, PCPG, PRAD, READ, SARC, STAD, TGCT, THCA, THYM, UCE, UCS) of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) was analysed in order to understand the preponderance of genomic gains of MCL-1 in cancer. Copy number gains and losses were classified in the same way as in the TRACERx dataset. Normalised mRNA counts were used in addition to the copy number classification to identify genes that are significantly gained and expressed on chromosome arm 1q. The resulting genes were then compared between cancer types to identify how commonly MCL-1 is significantly gained and expressed across cancer types.

The TCGA data of the NSCLC subtypes LUAD and LUSC has been further analysed to identify the frequency of high- and low-level gains of MCL-1, respectively. A one-sided Wilcoxon test was applied to test for a significant difference between MCL-1 expression levels of samples with gains versus no gains.

To build the heatmap for BCL-2 family, the expression data from TGCA-LUAD were medium centralized (both row and column, range −3 to 3) and then complete-linkage clustered before being plotted into the heatmap. The unit of expression is “log2(count + 1)” and the count represents RSEM34 normalised count. Accessed on 20.10.2017.

TMA-construction

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumour samples were assembled into a tissue microarray (TMA) using a Tissue Microarrayer (Alpha Metrix Biotech, Rödermark, Germany), extracting tumour samples with a core size of 1 mm per tumour block and case. All samples of a respective tumour region were extracted from areas exhibiting a high tumour/stroma ratio. Obvious inflammatory hotspots (such as lymph follicles or areas of ulceration) were avoided. The first investigated TMA was provided by Lungbiobank Heidelberg, member of the Biomaterialbank Heidelberg (BMBH) and the biobank platform of the German Centre for Lung Research (DZL). The TMA contained 102 tumour samples from 56 pulmonary adenocarcinomas, resected between 2005 and 2008 at the Thoraxklinik Heidelberg, Germany and this study had been approved by the local human ethics committee (no. 206/2005). The second study investigated TMA contained 75 tumour samples from 25 pulmonary adenocarcinomas. For this study, materials from the archive of the Institute of Pathology of the TUM was used, anonymised and provided by the MRI/TUM-biobank (approved by ethical committee Nr. 553/15 S). All patients had given written consent to the use of surgically removed tissue for scientific purposes.

MCL-1 fluorescence in situ hybridisation

MCL-1 gene copy number status was investigated using the ZytoLight SPEC MCL-1/1p12 Dual Colour Probe (Zytovision, Bremerhaven, Germany), which was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The probe contained green-labelled polynucleotides (ZyGreen: excitation at 503 nm and emission at 528 nm, similar to FITC), which target the human MCL-1 gene in 1q21.3, and orange-labelled polynucleotides (ZyOrange: excitation at 547 nm and emission at 572 nm, similar to rhodamine), which target sequences in the chromosomal region 1p12. MCL-1 gene gain was defined as MCL-1/1p12 ratio ≥2.0, with high-level gain defined as ≥4.0 and low level gain defined as ≥2.0 and ≤4.0. Polysomy was defined as average MCL-1 gene copy number >3 signals/cell. At least 20 neoplastic cells per core were evaluated. Areas with overlapping tumour cells were excluded from the analysis.

MCL-1 immunohistochemistry and evaluation

Primary LUAD tissues were stained with antibodies against MCL-1 (1:400, Proteintech,16225-1-AP) using an automated staining system (Bond Max, Leica microsystems). Expression was quantified with respect to the number of positive tumour cells. Staining intensity was assessed in a semi-quantitative manner by experimenters blinded to the diagnosis taking alveolar macrophages as reference for strong staining, as they showed a diffuse and distinct MCL-1 positivity throughout all cases. Representative images of strong, intermediate, and low intensity staining of MCL-1 are reported in Fig. 3c.

In vitro experiments

Human NSCLC cell lines: A549, NCI-H23, NCI-H358, NCI-H1437, NCI-H1650, NCI-H1975, NCI-H2087, NCI-H2126, NCI-H661, NCI-H1299, and NCI-H2170 were obtained from ATCC and HCC44 was purchased from Leibniz Institute DSMZ. The cell lines were authenticated with STR profiling analysis by ATCC. HCC44 was analysed with STR profiling and verified by DSMZ profile database35. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in complete media in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 (RPMI medium 1640 plus 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-Glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.15% sodium bicarbonate, 25 mM glucose, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin).

Genomic DNA from the cell lines was extracted with the Blood & Cell Culture DNA Kit kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Genomic DNA from peripheral mononuclear blood cells of a healthy individual was used as control. Library preparation was performed with an average of 200 ng DNA per sample using the NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina. Samples were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq system, resulting in ~20 Mio. single-end, 59 bp long, reads per sample. Resulting sequencing reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic and mapped to the human reference genome GRCh38.p12 using bwa mem. The GATK toolkit was used for base recalibration. Copy number alterations were called by HMMCopy. Total RNA isolation from the cell lines was performed using the Direct-zol MiniPrep Plus kit (Zymo Research) according to manufacturer´s instructions. cDNA was synthetised with QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) and was analysed by qRT-PCR using the GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega) on the LightCycler® 480 Instrument (Roche Life Science). The following primers were used: actin (for: AGAAAATCTGGCACCACACC, rev: AGAGGCGTACAGGGATAGCA), ABL2 (for: CACAGAGACCGGCTTCAATA, rev: TCATTTAGTGCCTGGGGTTC), ARNT (for: AGGGCTGGATTTTGATGATG, rev: CGCCGTTCAATTTCACTGT), BCL9 (for: GAAGACTCCAGCCAAAGTGG, rev: GTGTGTTCAGAGGCGCTGT), CDC73 (for: AATCTGTAACGGAGGGTGCAT, rev: AAGAGGTGGTAGCTGCAGGA), MCL-1 (for: AGAAAGCTGCATCGAACCAT, rev: CCAGCTCCTACTCCAGCAAC), MLLT11 (for: AGGCCTGGGTCTGTCAGATA, rev: CAATGGGAGCTCTCCAGAAG), PDE4DIP (for: CCACACCCTGGATGAGAGAT, rev: GGAGGGCCTCGATCTTTAGT), PRCC (for: AGGAAAGAGCCCGTGAAGAT, rev: CAGGTTTTTAGGTTGGGGAAG), RIT-1 (for: AGTTCATCAGCCACCGATTC, rev: CATATACTGGTCCCGCATGG), SETDB1 (for: CCGGCCTACAGAAATAATTGA, rev: CCTGGGAACTGCTCTTCTTG), SDHC (for: TCAAACCGTCCTCTGTCTCC, rev: AGAGACCCCTGCACTCAAAG), TPM3 (for: AAACTCAAGGAGGCAGAGACC, rev: AGGTCAAGCAGGGTCTGGT), TPR (for: TGAGCAGCTTGAGAAACTTCA, rev: TGCTTTTGAGTTGTGGCAGT).

Total protein extracts were prepared using RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling cat# 9806) containing protease inhibitors (complete protease inhibitor cocktail, Roche) and protein concentrations were determined by using the BCA assay (Thermo Scientific cat# 23225). Antibodies used were: anti-MCL-136 (1:1000, 19C4-15, rat monoclonal, gift from David Huang, WEHI), anti-BCL-236 (1:1000, Bcl-2-100, produced at WEHI), BCL-XL (1:1000, BD Bioscience, cat# 610212), BIM (1:1000, Enzo Life Science, cat# ADI-AAP-33-E), Caspase-3 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, cat# 9662), and KRAS (1:1000, SigmaAldrich, cat #MABS194, clone# 234-4.2). β-actin (1:40000, Cell Signaling, cat #4970, clone #13E5) and α-tubulin (1:5000, Cell Signaling, cat#9099) were used as loading controls. Uncropped gel images are provided as Supplementary Figs. 12–15.

For the pharmacological treatment, the cell lines were seeded into 96-well plates. They were exposed for 72 h to 3 µM ABT-737 (Active Biochem, A-1002) or 5 µM S63845 (Active Biochem, A-6044). Cell viability was determined by using the CellTiter-Glo® assay (Promega, cat# G7175).

The doxycycline-responsive lentiviral vector pFTRE3G_pGK3G_GFP encoding different BIMs variants have been previously described23. The lentivirally transduced NSCLC cells were seeded and on the next day treated with 1 µg/mL doxycycline to induce the expression of the BIMS variants. After 24 and 48 h, cells were collected in FACS buffer (PBS + 3% FBS) and the percentage of viable cells was determined by propidium iodide (PI) staining (3 µg/mL) and FACS analysis. PI-negative and green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive cells were considered to be live cells (gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Fig. 16).

In vivo experiments

At 6–8 weeks of age, mice were infected with 5 × 106 plaque forming units (PFU) of AdCre37 in two 62.5 µL intranasal instillations25. For the experiments reported in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figs. 9–10, mice of the different genotypes (KrasG12D/+;Mcl-1+/+, Kras G12D/+;Mcl-1Δ/+, and KrasG12D/+;Mcl-1Δ/Δ) were analysed 19 weeks after infection. Ethics approval number: 55.2-1-54-2532-55-12. For the experiments reported in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 11, KrasG12D/+p53Δ/Δ mice were randomised into two different groups at 10 weeks after infection: treatment with S63845 (40 mg kg−1 body weight per day for 5 consecutive days) and vehicle. S63845 (from Active Biochem, A-6044) was formulated in 25 mM HCl, and 20% 2-hydroxy propyl β-cyclodextrin (SigmaAldrich) and administered intravenously (i.v.)21. Ethics approval number: ROB-55.2-2532.Vet_02-14-69.

Mcl-1 analysis in mouse lungs

In order to check Mcl-1 mRNA expression in the lesions, RNA in situ hybridisation based RNAscope® 2.0 FFPE assay was used with the target probe (mmMcl-1, cat# 317241) according to the manual (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Inc, Rev 20120921)38. mmUBC, cat# 310771 and dapB, cat# 310043 served as technical positive and negative controls, respectively. Quantification of ISH was carried out manually by experimenters blinded to the genotype. The positive signal for Mcl-1 mRNA was measured in individual 2000 µm2 lesion areas (approximately 20 cells each).

In order to evaluate Mcl-1 copy number in lesion from KrasG12D/+p53Δ/Δ deletion, we extracted genomic DNA from lesion from FFPE slides with the prepGEM Universal (MicroGEM International) following the manufacturer´s instructions. Extracts were diluted to 5 ng/µL and analysed by Taqman® assay, as described below.

Tumour burden analysis

All lungs were sectioned into 3 step-sections at 100 µm intervals. The third sections of each step-sections were H&E stained and used for tumour burden analysis. The sections were scanned with a SCN400 slide scanner (Leica microsystems) and the area (µm2) of individual proliferative lesions and total lung area (µm2) on the sections were determined by manually defining the lesion within a lung area using the free-hand mode of the Tissue IA image analysis software and/or Aperio imagescope (Leica microsystems). The total numbers of the lesions on each section were also counted. Three H&E stained sections per animal were analysed.

Ex vivo micro-computed tomography (µ-CT)

The commercial lab-based system Zeiss Xradia 500 Versa by Carl Zeiss (Carl Zeiss Microscopy) was used for X-ray µ-CT analysis. The system was driven with a tube voltage of 40 kV and a current of 63 μA. The detector assembly includes a switchable-objective lens unit (×0.39, ×0.4, ×20) coupled to a charge coupled device (CCD) camera made of 2048 × 2048 pixels for a pixel size of 13.5 μm. With the 0.39x-demagnifying objective and adequate settings of the distances from the sample to source and detector, instantaneously, the samples of 1–1.5 cm in size were entirely recorded across the field of view (FOV) granted by the detector. Accordingly, the scans were completed with effective pixel sizes in a range of 12–13 μm by recording 1201 projections over 360 degrees. The reconstruction of the tomograms was set to occur automatically with the dedicated software and performed properly after each measurement. The tumour burden was assessed by experimenters blinded to the genotype for segmentation owing to the substantial contrast expressed between the lung healthy lung tissue and the lung lesions. For the purpose of quantitative analysis, the segmentation was performed with VGStudioMax2 2.1 (Volume Graphics GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany).

Evaluation of proliferative lesion histology

One slide per mouse, in total 8–11 mice per genotype, were analysed histologically and classified as hyperplasia, adenoma or adenocarcinoma25,39. Specifically, hyperplasia is defined by increased cellularity without atypia, enlarged cells, and normal architecture of bronchioles and alveoli; adenoma is characterised by well circumscribed areas consisting of cuboidal to columnar cells lining alveoli, uniform population of epithelial cells with round nuclei, size less than 5 mm in diameter, and absence of vascular invasion; adenocarcinoma is defined by nuclear enlargement and prominent nucleoli, increased mitotic rate, size over 5 mm in diameter, and invasion of vessels. If not otherwise indicated, proliferative lesions included hyperplasia, adenoma, and adenocarcinoma.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using an automated staining system, Bond Max (Leica microsystems). Antibodies against the following target proteins were used: Ki67 (1:200, ThermoFisher, cat #RM-9106, clone #SP6), cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175) (1:300, Cell Signaling, cat# 9661), CC10 (T18) (1:100, Santa-Cruz, cat #sc-9772), SP-C (C19) (1:500, Santa-Cruz, cat #sc-7705). For quantification of staining and image acquisition, slides were scanned using a SCN400 slide scanner (Leica microsystems) and analysed using Tissue IA image analysis software (Slidepath, Leica microsystems) and/or Imagescope Aperio (Leica micropsystems) by experimenters blinded to the genotype.

Primary culture and 3D lung organoids (pulmosphere) culture

Single cells were generated from freshly excised lung tumours. The primary cells were cultured in complete PneumaCult™-Ex medium (STEMCELL technology, cat# 05008) at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Genomic DNA was extracted from these primary cultures with the prepGEM Universal (MicroGEM) following the manufacturer’s instructions. To evaluate Mcl-1 copy number, we used Taqman@ copy number assays (ThermoFischer) with the Mcl-1 probe (assay ID: Mm00544723_cn) and the reference probe Tfrc (cat#: 4458366). Data were analysed with CopyCaller® software (Applied Biosystems).

1000 live cells were re-suspended in 100 µL of PneumaCult™-Ex Medium on ice. The cell-matrigel mixture was then plated in µ-Plate 96-well ibiTreat (ibidi) and incubated at 37 °C for half an hour. The semi-solid culture was topped with another 200 µL of PneumaCult™-Ex medium and incubated for 3 days. The pulmospheres were observed in Leica microscope for 8 days, the position of pulmosphere was fixed with defined x and y axis and then the growth was monitored on day 1, 2, 4 and 8.

In vivo µ-CT of S63845/vehicle treated mice

Mice were anesthetised with 2% isoflurane as maintenance dose after induction with 4% isoflurane. µ-CT images of free-breathing animals were acquired using an in vivo µ-CT scanner (Skyscan 1176, Bruker, Kontich, Belgium). Animals were scanned at 50 kV X-ray source voltage and 180 µA source current combined with 0.5 mm aluminium filter, acquiring 7 projections/position with 0.7° increments over 180°. This resulted in a scanning time of approximately 8 min with 35 µm image resolution. Image-based data sorting using DataViewer software (Version 1.5.6.2, Bruker, Kontich, Belgium) was employed yielding four 3D reconstructed datasets corresponding to four different phases of the breathing cycle. The breathing cycles were determined using a coupled camera using thorax movements. Subsequently, µ-CT data were retrospectively reconstructed using NRecon (Version 1.7.3.2, Bruker, Kontich, Belgium), DataViewer and CTAnalyser (Version 1.17.7.2, Bruker, Kontich, Belgium) for the generation of 3D model representing the tumour burden in the lung. Ethics approval number: ROB-55.2-2532.Vet_02-14-69. The reconstructed images were viewed and measured with Horos software by experimenters blinded to the treatment. The area (mm2) of individual tumour was determined by manually defining the biggest tumour area using pencil tool of the software. Three to five tumour lesions that were visible at every time point were selected per mouse. The baseline measurement of individual tumour was assigned as 100%.

Statistical analysis and data presentation

The data are presented as dot plot or box plot. For the dot plots, mean and SEM are reported in figure. In the box plots, the centre line represents the median value, the limits represent the 25th and 75th percentile, and the whiskers extend from the box to the largest and lowest value no further than 1.5 * IQR away from the box, where IQR is the inter-quartile range.

The data analysis was performed in the R statistical environment version > = 3.3.1 and with GraphPad Prism software. Comparisons between two groups were made using one-sided Wilcoxon test, whereas for more than two groups one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction was used unless differently stated. A permutation method was applied to calculate the null distributions for the frequency of gains and losses followed by 95% quantile calculation to identify frequently gained and lost events. A list of published cancer driver genes16 was used to check which of the identified differentially expressed genes were reported previously. For analyses of distribution, the chi-squared test was used. For analysis of the effects of genotype (pulmosphere) or treatment (S63845) across time, repeated measure two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis was used. All values are presented as means ± SEM if not otherwise indicated. For all statistical tests statistical significance was determined if the p value was less than 0.05, unless otherwise stated.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of the TRACERx consortium for participating in this study. The results published here are in part based upon data generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas pilot project established by the NCI and the National Human Genome Research Institute. The authors would like to thank S Schwamberger and I Konrad for mouse handling, and Life Science Editors for editing assistance. We thank David Huang for gift of antibodies. The authors would like to thank Gewebebank des Klinikums rechts der Isar und der Technischen Universität München, A Terron Kwiatkowski, A Jacob, R. Öllinger, and G Sannino for the excellent technical support. We thank Martin Schuler for critical discussion of the data. Grant Support Grant support by the Mildred Scheel Professorship program from the Deutsche Krebshilfe (program #70113247), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation – FOR 2036, SFB 1335 (Project-ID 360372040), SFB 1371), German Consortium for Translational Cancer Research (DKTK) to P.J.J.; the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation - SFB 1335 (Project-ID 360372040), SFB 1371) to K.S. A.S. is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grant 1143105, NHMRC program grant 1016701, NHMRC fellowship 1020363, Cancer Council of Victoria (CCV) project grant 1052309 and a CCV Venture Grant. N.M is a Sir Henry Dale Fellow, jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (Grant Number 211179/Z/18/Z), and also receives funding from Cancer Research UK Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence, Rosetrees, and the NIHR BRC at University College London Hospitals. F.B. receives grants from the European Research Commission (project BCM-UPS, grant #682473) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 1335 and SFB1243).

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: P.J.J., N.M., E.M., M.D.; Investigation: E.M., M.D., C.B., D.A., M.J., P.B., M.B., S.U., U.H., A.M., A.W., P.S.P.P., S.L., M.S., X.W.; Resources: M.A., N.P., I.H., R.B., R.M., A.W., T.M., S.F., K.S., J.S.H., M.v.G., F.P., R.R., G.T.S., J.R., F.B., W.W., A.S., M.H., C.S., P.J.J., N.M.; Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: E.M., M.D., C.B., P.J.J., N.M., C.S.; Study supervision: P.J.J., N.M., C.S.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas pilot project established by the NCI and the National Human Genome Research Institute was downloaded. The data were retrieved through database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) authorisation (accession no. phs000854.v3.p8). Information about TCGA and the investigators and institutions who constitute the TCGA research network can be found at https://cancergenome.nih.gov/. The genomic TRACERx data can be downloaded from the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA), which is hosted by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) and the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), under the accession number EGAS00001002247. The data have been processed as described in ref. 16. The remaining data are available within the Article, Supplementary Information or available from the authors upon request.

Code availability

The data collection and processing were performed in the R statistical environment version >= 3.3.1. Code for the data analysis can be downloaded from https://github.com/McGranahanLab/MCL1amplification.

Competing interests

S.F. has had a consulting or advisory role, received honoraria, research funding, and/or travel/accommodation expenses from the following for-profit companies: Bayer, Roche, Amgen, Eli Lilly, PharmaMar, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. W.W. has attended Advisory Boards and served as speaker for Roche, MSD, BMS, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Merck, Lilly, Boehringer, Novartis, Takeda, Amgen and Astellas. W.W. receives research funding from Roche, MSD, BMS and Bruker. A.S. is an employee at The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, which receives milestone payments and royalties from Genentech and AbbVie for the development of Venetoclax. A.S. has collaborations with Servier for the development of MCL-1 inhibitors for cancer therapy. N.P. has had a consulting or advisory role for Novartis. C.S. has had a consulting or advisory role, received honoraria, research funding, and/or travel/accommodation expenses from: Pfizer, AstraZeneca, BMS, Roche Ventana, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, BMS, Celgene, Illumina, Sarah Canon Research Institute, Genentech, Roche Ventana, GRAIL, Medicxi, and Dynamo Therapeutics. C.S. has stock options in Apogen Biotechnologies, Epic Bioscience, GRAIL. C.S. is co-founder and has stock options in Achilles Therapeutics. N.M. has stock options and has received consultancy fees from Achilles Therapeutics. P.J.J. has had a consulting or advisory role, received honoraria, research funding, and/or travel/accommodation expenses from: Abbvie, BMS, Boehringer, Novartis, Pfizer, Servier, and Celgene. All the other authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks David Barbie, Anton Berns and Maria Teresa Landi for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Enkhtsetseg Munkhbaatar, Michelle Dietzen.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Nicholas McGranahan, Philipp J. Jost.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-18372-1.

References

- 1.Bray F, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clinicians. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2018;553:446–454. doi: 10.1038/nature25183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostrem JM, Shokat KM. Direct small-molecule inhibitors of KRAS: from structural insights to mechanism-based design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:771–785. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lito P, Solomon M, Li L-S, Hansen R, Rosen N. Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. Science. 2016;351:604. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jänne PA, et al. Selumetinib plus docetaxel compared with docetaxel alone and progression-free survival in patients with kras-mutant advanced non–small cell lung cancer: The select-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:1844–1853. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumenschein JGR, et al. A randomized phase II study of the MEK1/MEK2 inhibitor trametinib (GSK1120212) compared with docetaxel in KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC)†. Ann. Oncol. 2015;26:894–901. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janic A, et al. DNA repair processes are critical mediators of p53-dependent tumor suppression. Nat. Med. 2018;24:947–953. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieschke, E., Wang, Z., Kelly, G. L. & Strasser, A. Discussion of some “knowns” and some “unknowns” about the tumour suppressor p53. J. Mol. Cell Biol.11, 212–223 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Luo J, Solimini NL, Elledge SJ. Principles of cancer therapy: oncogene and non-oncogene addiction. Cell. 2009;136:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts AW, et al. Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beroukhim R, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Marrero Y, Spinner S, Kaufmann T, Jost PJ. Survival control of malignant lymphocytes by anti-apoptotic MCL-1. Leukemia. 2016;30:2152–2159. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borner MM, et al. Expression of apoptosis regulatory proteins of the Bcl-2 family and p53 in primary resected non-small-cell lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 1999;79:952–958. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, et al. Mcl-1 is critical for survival in a subgroup of non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2011;30:1963–1968. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamal-Hanjani M, et al. Tracking the evolution of non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:2109–2121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craig RW, et al. Human and mouse chromosomal mapping of the myeloid cell leukemia-1 gene: MCL1 maps to human chromosome 1q21, a region that is frequently altered in preneoplastic and neoplastic disease. Genomics. 1994;23:457–463. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zappa C, Mousa SA. Non-small cell lung cancer: current treatment and future advances. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5:288–300. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2016.06.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wesarg E, et al. Targeting BCL-2 family proteins to overcome drug resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J. Cancer. 2007;121:2387–2394. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song L, Coppola D, Livingston S, Cress D, Haura EB. Mcl-1 regulates survival and sensitivity to diverse apoptotic stimuli in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2005;4:267–276. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.3.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotschy A, et al. The MCL1 inhibitor S63845 is tolerable and effective in diverse cancer models. Nature. 2016;538:477–482. doi: 10.1038/nature19830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zack TI, et al. Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/ng.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly GL, et al. Targeting of MCL-1 kills MYC-driven mouse and human lymphomas even when they bear mutations in p53. Genes Dev. 2014;28:58–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.232009.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Opferman JT, et al. Development and maintenance of B and T lymphocytes requires antiapoptotic MCL-1. Nature. 2003;426:671–676. doi: 10.1038/nature02067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson EL, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell KJ, et al. MCL-1 is a prognostic indicator and drug target in breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:19. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0035-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brinkmann K, et al. The combination of reduced MCL-1 and standard chemotherapeutics is tolerable in mice. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:2032. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber, A. et al. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of the anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1 triggers proliferation and hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Hepatology (Baltimore. Md.) 51, 1226–1236 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Grabow S, Delbridge AR, Aubrey BJ, Vandenberg CJ, Strasser A. Loss of a single Mcl-1 allele inhibits MYC-driven lymphomagenesis by sensitizing Pro-B cells to apoptosis. Cell Rep. 2016;14:2337–2347. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grabow S, Delbridge ARD, Valente LJ, Strasser A. MCL-1 but not BCL-XL is critical for the development and sustained expansion of thymic lymphoma in p53-deficient mice. Blood. 2014;124:3939. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-601567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spinner S, et al. Re-activation of mitochondrial apoptosis inhibits T-cell lymphoma survival and treatment resistance. Leukemia. 2016;30:1520–1530. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nangia, V. et al. Exploiting MCL-1 dependency with combination MEK + MCL-1 inhibitors leads to induction of apoptosis and tumor regression in KRAS mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov.8, 1598–1613 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Marino S, Vooijs M. van Der Gulden, H., Jonkers, J. & Berns, A. Induction of medulloblastomas in p53-null mutant mice by somatic inactivation of Rb in the external granular layer cells of the cerebellum. Genes Dev. 2000;14:994–1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dirks WG, et al. Cell line cross-contamination initiative: an interactive reference database of STR profiles covering common cancer cell lines. Int. J. Cancer. 2010;126:303–304. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen L, et al. Differential targeting of prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins by their BH3-only ligands allows complementary apoptotic function. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anton M, Graham FL. Site-specific recombination mediated by an adenovirus vector expressing the Cre recombinase protein: a molecular switch for control of gene expression. J. Virol. 1995;69:4600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.69.8.4600-4606.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang F, et al. RNAscope: a novel in situ RNA analysis platform for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. J. Mol. Diagn. 2012;14:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nikitin AY, et al. Classification of proliferative pulmonary lesions of the mouse: recommendations of the mouse models of human cancers consortium. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2307–2316. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas pilot project established by the NCI and the National Human Genome Research Institute was downloaded. The data were retrieved through database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) authorisation (accession no. phs000854.v3.p8). Information about TCGA and the investigators and institutions who constitute the TCGA research network can be found at https://cancergenome.nih.gov/. The genomic TRACERx data can be downloaded from the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA), which is hosted by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) and the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), under the accession number EGAS00001002247. The data have been processed as described in ref. 16. The remaining data are available within the Article, Supplementary Information or available from the authors upon request.

The data collection and processing were performed in the R statistical environment version >= 3.3.1. Code for the data analysis can be downloaded from https://github.com/McGranahanLab/MCL1amplification.