Abstract

Objectives

With the increasing popularity of electronic cigarettes and legalization of recreational marijuana, messaging from websites and social media is shaping product perceptions and use. Quantitative research on the aesthetic appeal of these advertisements from the adolescent and young adult perspective is lacking. We evaluated (1) how adolescents and young adults perceived tobacco and marijuana messaging online and through social media platforms and (2) interactive behaviors related to these messages.

Methods

We interviewed 24 participants from the Tobacco Perceptions Study, a longitudinal study of adolescents’ and young adults’ (aged 17-21) tobacco-related perceptions and tobacco use. We collected qualitative data from October 2017 through February 2018, through individual semi-structured interviews, on participants’ experiences and interactions with online tobacco and marijuana advertisements and the advertisements’ appeal. Two analysts recorded, transcribed, and coded interviews.

Results

Themes that emerged from the interviews focused on the direct appeal of online messaging to adolescents and young adults; the value of trusting the source; the role of general attitudes and personal decision-making related to using tobacco and/or marijuana; the appeal of messaging that includes colors, interesting packaging, and appealing flavors; and the preference of messages communicated by young people and influencers rather than by industry.

Conclusion

These findings suggest the need for increased regulation of social media messaging and marketing of tobacco and marijuana, with a particular focus on regulating social media, paid influencers, and marketing that appeals to adolescents and young adults. The findings also suggest the importance of prevention programs addressing the role of social media in influencing the use of tobacco and marijuana.

Keywords: tobacco, marijuana, social media, JUUL, peer networks

Cigarette use among high school students has declined since 2002.1 However, the prevalence of electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults is high; 27.1% and 19.8% of high school students reported using any tobacco or any marijuana in the past 30 days, respectively, in 2017.2

Research has implicated the marketing of e-cigarettes and marijuana, particularly through social media, as one reason for the observed increase in use.3-7 Tobacco companies use marketing to shape risk perceptions and increase beliefs in the acceptability of tobacco.7,8 Historically, cigarette companies relied heavily on television and print marketing, often targeting adolescents and young adults; such marketing is now heavily regulated.9,10 However, e-cigarette and marijuana marketing, which is largely unregulated, is ubiquitous, with much advertising conducted through online sites and social media.11,12 Such messaging often results in perceptions of reduced health risks, elevated emotional and personal benefits, and increased social acceptability of tobacco.6,13 Often, such social media is driven by adolescents; however, on some sites such as Twitter, 80% of social media is driven by industry.14

Studies have analyzed the number and types of messages involving tobacco and in particular e-cigarettes on social media platforms, such as tracking JUUL-related Twitter posts.15,16 Messaging can also include user-created content, such as memes and vape trick videos, as well as content paid for and produced by tobacco companies. Emerging themes of tobacco product marketing and messaging include freedom of choice and the ability to smoke anywhere.7,17 Marijuana companies are also creatively advertising to young people through social media and health claims.18-20

Generally, researchers have identified themes of tobacco and marijuana messaging or have focused on the content of social media posts. Few studies have directly asked adolescents and young adults about the common themes they have seen in messaging or the appealing aspects of the messages.21-23 Research is also lacking on self-reported interactions with advertisements, such as commenting, sharing, and/or viewing these messages and what adolescents and young adults find appealing about social media messaging. The objective of our qualitative study was to understand and evaluate (1) how adolescents and young adults perceive tobacco and marijuana messaging online and on social media platforms, including whether and what aspects of these advertisements appeal to them, and (2) adolescent and young adult interactive behaviors related to these messages and what influences these interactions. Findings from this study will help form a more complete picture of online tobacco and marijuana messaging to inform regulation and prevention education. With the rapid evolution of tobacco and marijuana in the technological space,24 in both product development and marketing, it is imperative that public health research and policy respond to these advancements.

Methods

In 2017, researchers recruited participants for this qualitative study from the Tobacco Perceptions Study, a longitudinal study conducted from 2014 to 2019 of adolescent and young adult attitudes toward tobacco products, their use, and the role of marketing in perceptions and use.25 The parent project consisted of 772 high school students in 9th and 12th grades (ie, aged 13-19) residing in California who completed consent/assent packets, including consent to be interviewed.

Research assistants reached out to nearly 60 participants from the Tobacco Perceptions Study for this qualitative study, purposively stratified by users and nonusers of tobacco and/or marijuana products. The final sample (N = 24) ranged in age from 17 to 21 (mean = 19.3); 18 were female, 5 were male, and 1 identified as gender nonbinary. Nine participants were Asian, 8 were non-Hispanic white, 2 were Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, 2 were Hispanic/Latinx, and 3 identified as >1 race. Sixteen participants were users (defined as those who had ever tried using either tobacco and/or marijuana products), and 8 were nonusers (defined as those who had never used either tobacco or marijuana products). Of the 16 participants who self-identified as users, 3 had used tobacco exclusively, 1 had used marijuana exclusively, and 12 had used both tobacco and marijuana. The remaining 36 participants who were contacted to participate in the interviews either declined participation or did not respond.

Research assistants conducted interviews from October 2017 through February 2018. Participants received an email to schedule the interview, which was conducted through Zoom, a video-conferencing platform certified for meetings that involve protected health information. Before each interview began, the interviewer reminded participants that the interview was being recorded and was confidential. The participants received a $25 gift card for their participation. The Stanford University Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

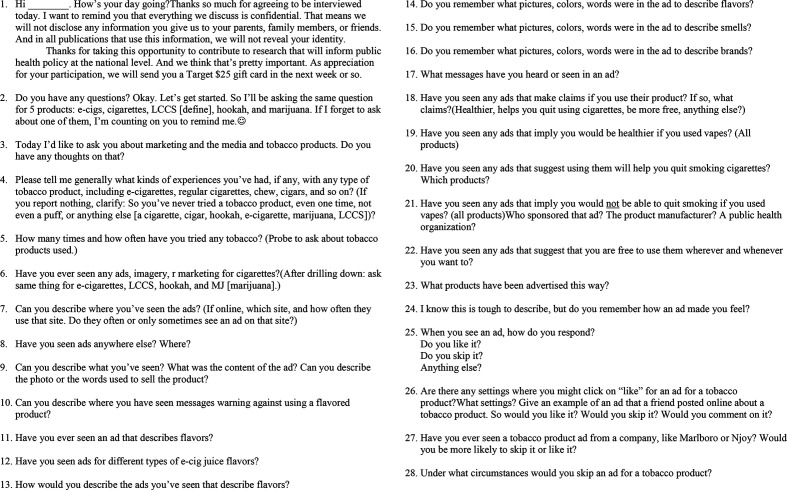

The interview guide was consistent throughout the 24 interviews, with interviewers given the freedom to probe further as warranted (Figure). A third-party transcription service recorded and transcribed the interviews verbatim. Using the software Dedoose, the primary coder (J.L.) identified themes and ideas throughout the interviews that related to the research questions.26 Then, the secondary coder (B.H.F.) together with the primary coder discussed common themes and grouped them into major themes. We extracted and tabulated quotes from the transcriptions that illustrated major themes and subthemes. We initially grouped themes and quotes by users and nonusers; however, because we found that themes and quotes did not differ by users or nonusers, we combined all data. We reached saturation (ie, when redundancy is reached in data analysis) after 24 interviews.

Figure.

Semi-structured interview guide on participants’ experiences with and perceptions of online tobacco and marijuana advertisements used during interviews with 24 participants (aged 19-21) in California, 2017-2018.

Results

Three major themes emerged: how online platforms and social media tools influence interfacing (2 subthemes), direct appeal of messaging to adolescents and young adults (3 subthemes), and source of messaging (4 subthemes) (Table).

Table.

Quotes illustrating the themes emerging from interviews with adolescents and young adults aged 19-21 (N = 24) in California, 2017-2018a

| Subthemes | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| How Online Platforms and Social Media Tools Influence Interfacing | |

| Interactions with online platforms and social media | I would say friends and social media [are] the most influential in getting me to try [tobacco], just because, I mean, it’s what I’m exposed to the most, the people that I choose to follow on Twitter and Instagram and stuff like that. (User A) |

| So, I think on Instagram at least, they just recommend—you can kind of go to a recommended page of images you might like, and it’s just a bunch of things that they compile from, like, depending on what you’ve liked or looked at on Instagram. (User A) | |

| I know some of the people on Instagram will post like that. And then they get some money from the shop for linking the shop’s website in their caption. (Nonuser A) | |

| I have seen some videos, like on Instagram of some people hitting 5 JUULs at once, like crazy hit. (User B) | |

| It’s a meme. I remember specifically this one with [an] old grandma using 50 different [tobacco and marijuana products] and people are just like, “Damn, she’s so cool.” A lot of people will like it and that’s how I saw it, ’cause it was really liked and it was shared to me. (User C) | |

| JUUL just recently came out with a limited-edition flavor. And I personally never saw like a sponsored post by them like promoting that because I also am not subscribing to anything for JUUL. But my friends kind of indirectly promoted it by like posting it on their Snapchat or stuff like that. (User D) | |

| So in Reddit, there are several, I guess, groupings, kind of like a subforum for everyone to post a thread related to one particular topic. So one sub-Reddit is named “trees.” (Nonuser B) | |

| The JUUL website is a really, like—pretty like, well-developed website. . . . The JUUL website is something that people go on very frequently . . . if you’re like, you know, age verified and all that stuff, there’s a couple of things that you have to fill out. But so they make it very easy to like, get another JUUL or to get pods, or to find where those pods are. (User E) | |

| Sharing and privacy of tobacco and marijuana advertisements on social media | But like if it was a smoking- or marijuana-related thing, I probably wouldn’t do that on Facebook anyways, ’cause that’s like, you know, just where family and stuff is. But if I saw like something like that on Twitter, I might @ [“at”] a friend or DM [direct message] them, like a link. (User F) |

| Yeah, I’ll just show it to them in person or I’ll just text them. (User F) | |

| Yeah, I’ve had friends tag me in promotions for like bongs or glassware that they’re giving away. (User G) | |

| Online, I would say—one thing that I remember in particular is after I signed up for the website with JUUL, they sent me emails and they were advertising like another—a new flavor that they had only online. (User H) | |

| Like, “Hey, did you hear about that sale? . . . Let’s all go over to the shop tomorrow. Let’s go buy some.” And then like, you know, posting it on social media and showing it off to other people. (User I) | |

| Direct Appeal of Messaging to Adolescents and Young Adults | |

| Packaging and colors | I think it’s just kinda like . . . innovation. A lot of younger people are like, into new technology, new products, and it just kinda like . . . it’s kind of like the same thing. They wanna try new things, they’re curious. (User I) |

| Very clean cut, like almost like it was based for the millennial, you know, like looking for something that looks really nice design-wise. (User B) | |

| I just remember that for JUULs they use like—of course there would be the word JUUL on it . . . it’s a white background but it’s still minimalistic. There’s not much going on with the ad besides the product itself and the name of the product. (User H) | |

| Right, yeah, so, Pax, I think their logo is just the X, like, at the end of “Pax.” And I think they would market, like, the simplicity of their products. (User A) | |

| I don’t remember any specific text other than it probably said JUUL or whatever. . . . But, yeah, it was more so just a picture. I don’t remember any specific writing. (User B) | |

| I mean I remember that JUUL classifies their flavors by like colors, so like fruit is red, mint is green, tobacco is like brown and like a crème brûlée flavor, that’s yellow. And I think the other one’s actually blue. (User D) | |

| I think it’s also about the message and more just like “This is what I want you to associate with my product. When you see this color and like this texture of color, this is what I want. I want you to think of Swishers when you see like shiny purple.” (User G) | |

| One of my other friends on her 21st birthday, a bunch of my friends got together and gave her some marijuana from a company . . . she got really excited because she was like, “You got me feminist marijuana!” because the [logo] of the marijuana company was a woman, and that’s very rare in the marijuana industry. (User J) | |

| Positive appeal of messages | I’ve seen a lot more advertisements for it, very positive. A lot of it’s like, “Hi, San Diego,” kind of more the uplifting kind of—yeah, just emphasizing a high state of mind and a looseness and a happiness from those advertisements. (Nonuser C) |

| Not necessarily a healing tube, but it’s like, “Oh, it’ll calm you down” or something like that. They advertise it almost as medicine. (User C) | |

| So these advertisements come in for the e-cigs and vapes, showing that this is a healthier alternative, which I do think it is. I still don’t think it’s healthy, but compared to cigarettes, obviously it’s much healthier to use that. (User F) | |

| Flavors and reduced risk | I’ve definitely seen advertisement . . . like the different fruity flavors, to try to make it enticing to you or normalize it a little bit. ’Cause like, you’re familiar with a strawberry. Like, strawberry, that’s like ice cream, that can’t be bad for you. (User H) |

| Juicy, they have juicy as a descriptive word. (User L) | |

| Say you want cotton candy, but you don’t want to go track down someone who is actually selling cotton candy. Well, here’s the liquid for you, something that you can’t usually get, I guess, but you can get a taste of or a little sample of in this product. That’s my reaction and response. (User K) | |

| I think they were like, oh, like they’re trying to be like hip and like show that like these different flavors are cool and—yeah. (Nonuser K) | |

| Source of Messaging | |

| Celebrities | I could see myself like taking a picture with a marijuana product, you know, like actors, like Seth Rogen and all those other people do them, like, you know, this is fun. (User F) |

| Yeah, but there’s—I remember there actually is like a girl on YouTube and there’s a lot of YouTubers and a lot of Instagrammers that do promote like weed. I don’t know about tobacco, in particular. There’s probably like vape ones but I’ve only seen marijuana and that’s what they specifically advertise, and they get sponsored and they do reviews and stuff. (User L) | |

| But then a lot of times, too, it’s you know just the lifestyle of the artist that is in the video and like they’re just promoting their lifestyle, even if that means some product placement by mistake. (User G) | |

| I like to listen to a lot of music, and definitely hearing other artists that I like and look up to talk about smoking blunts, and smoking—just like really weed product. And I guess like cigarettes too, definitely influenced me on trying these products, and doing them to feel cool, you know? (User F) | |

| One of my favorite artists, Wiz Khalifa, he’s a rapper, a hip-hop rapper, and so I’ve seen him post photos of him[self] like smoking a joint with like some cigars on the table, as well as liquor and cigarettes. (User M) | |

| Lack of trust in industry | ’Cause I just feel like in [the] tobacco industry, there’s just like a lot of lying and corruption. And definitely that’s seeping over into like marijuana, since it’s about to be legalized, but there’s just like more—I feel like there’s more honesty among like—in the marijuana, it’s weird saying industry, ’cause it wasn’t necessarily an industry. But now it like is moving towards that. So, yeah. (User F) |

| Well, if it were from the company, I would be less likely to trust it, because I know that they’re benefiting from selling the product; whereas my friends or like people I follow, I feel like it’s much more like their own opinion and they don’t really have like a lot to gain from like sharing that information. (Nonuser D) | |

| Peers over industry | My friends are people that I, you know, have a personal relationship with, so anyone who I know personally as opposed to some big faraway corporation advertisement I would give more credibility to. (User N) |

| A really large portion of my friends seem to continually pop up and say that they have started to regularly smoke marijuana or a couple of them I have seen or heard of or seen them on social media vaping or JUULing. So although I don’t do it and a couple close friends kind of stay very distant from it, what I’ve observed is just a trend of more and more people doing it. (Nonuser E) | |

| I have smoked marijuana because of course there’s like a lot of pressure from my friends and a lot of other people telling me that it’s beneficial and it’ll help. (User H) | |

| I used to have like very, very negative feelings towards marijuana, but like when I’ve heard my friends have tried it—like it’s made me think that maybe it’s like not as bad as I previously thought, and like people who do use it like aren’t terrible, they’re like just regular people. (Nonuser D) | |

| I guess I see a lot of people that—friends that I have that do use products have a way of glorifying things and making it seem cool, so I guess, yeah, Instagram is very much a way to make your own advertisement of something; the way that you take pictures of something or that setting makes it seem very cool. (Nonuser C) | |

| Agencyb | Never. I feel like everyone has their own freedom of speech, and they should be, no matter what, they should be allowed to say what they think or show what they think, as long as it’s appropriate enough for the world to see. (User M) |

| Because I don’t smoke and because I don’t really have the urge to do drugs, I find that the messages are often kind of not obnoxious but a little frustrating to have them put in front of me because it seems like some higher authority trying to tell me to do something that I know or choose not to do already, so it almost seems extraneous. (Nonuser E) | |

| Why they’re annoying? Okay, I just like—they just sound so preachy and I feel like they don’t necessarily dissuade people who are going to—who are like already indulging in those products and like. . . there’s like a small subset of people who I just feel like the amount of people that could be influenced by this are not that many and I just think they’re like really preachy. (User O) | |

aParticipants were from the Tobacco Perceptions Study, a longitudinal study of adolescents’ and young adults’ (aged 17-21) tobacco-related perceptions and tobacco use in California.

bPersonal choice and the ability to fully make decisions for oneself.

How Online Platforms and Social Media Tools Influence Interfacing

Participants discussed various social media platforms (websites and social media companies) on which they saw tobacco and marijuana messaging. Social media platforms had more individually tailored exposure of messaging and a greater influence on adolescents and young adults than traditional print marketing, especially related to tobacco and marijuana (Table).

Interactions with online platforms and social media

Participants mentioned that Facebook included advertisements from tobacco companies, even though participants did not directly follow or subscribe to the companies. Participants also discussed Instagram and how certain images of JUULs and other e-cigarettes could be viewed easily without having to directly follow related accounts. Participants described Instagram as a place to sell and promote tobacco and marijuana products, not necessarily only products promoted by the companies and industry themselves but rather from individual social media users. This indirect promotion could occur through more extreme images, defined as photos that seem unrealistic and/or hyperbolic, and videos posted by other Instagram users. An example of these extreme images is memes, usually an amusing photo with overlaid text, which are spread widely through online photo-sharing social media platforms. Participants described sharing tobacco- and marijuana-related memes directly with friends. For example, funny memes or images that got a lot of attention and “likes” on social media will commonly get directly shared to other friends’ social media accounts.

Participants described Snapchat, a photo- and video-sharing social media platform, as a method of learning about tobacco products, such as flavored JUUL pods, directly from their friends. Participants mentioned Reddit, a social media platform with subject-specific forums, as containing a marijuana-related forum. Participants also described company websites as a place to receive messaging on tobacco and marijuana. Participants mentioned the JUUL Labs website as a convenient place to gain access to products.

Sharing and privacy of tobacco and marijuana messaging on social media

Adolescents and young adults shared and interacted with tobacco and marijuana messaging in various ways through social media, such as commenting, publicly sharing, or directly messaging to friends. Privacy of sharing was an important consideration, and rather than leaving public comments on social media, participants described direct messages as the most secure and comfortable way to share potentially illicit content about tobacco or marijuana with friends. Participants explained how they would try to share social media content through screenshots and texting with their friends for additional privacy. Participants described tagging, in which a user is notified that he or she has been linked to a post, as a method to relay information about online deals of tobacco or marijuana. Participants said they used tagging to help their friends gain access to more tobacco and marijuana products. Participants also described ways that Eaze, a marijuana delivery company, and JUUL Labs would engage directly with them through online promotional discounts, and then friends would share these promotions on social media.

Direct Appeal of Messaging to Adolescents and Young Adults

The visually appealing messaging generated by the tobacco and marijuana industries and circulated by celebrities and peers meets adolescent and young adult preferences for information delivery and reception. Participants described their generation’s interest in innovative tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, and described these products being advertised in a way to showcase that novelty. Participants also referred to messaging that called JUUL “the Apple of e-cigs” as an example of appealing advertising.

The following characteristics make it apparent that the messages contribute to positive perception of tobacco and marijuana among adolescents and young adults.

Packaging and colors

Participants described liking messages, designs, and product packaging that were simple and colorful. One participant described these designs as “based for the millennial” and helped the participant better remember the tobacco or marijuana product. Participants described how they remembered the subtler aspects of JUUL messages, such as advertisements that lacked text. Participants discussed the attention-grabbing colors in tobacco and marijuana messaging and how these colors were used to bolster the advertising of flavors. Furthermore, having certain themes or common imagery in the advertisements was mentioned as a memorable component, often resulting in the purchasing of marijuana.

Positive appeal of messages

Participants described humorous advertisements as likable and likely to be shared with friends. Having a positive tone was an appealing aspect, especially for marijuana advertisements. Participants noted marijuana was often advertised online as a stress reliever. Even some nonusers described their openness to trying marijuana after viewing positive messaging related to marijuana products. Perceptions of reduced harm were also present in comparisons of e-cigarettes with combustible cigarettes, calling e-cigarettes a “healthier alternative.” Sexual appeal was brought up as notable in social media content on tobacco and marijuana; 1 participant described it as including “hot girls and alcohol.”

Flavors and reduced risk

Many participants described constant messaging on e-cigarettes’ relative safety compared with combustible cigarettes and on flavors that feature familiar fruit and desserts, which make e-cigarettes seem less harmful than combustible cigarettes. These flavors are advertised through associations of images of fruit and descriptive somatosensory language. One participant described flavors as being a convenient way to enjoy the taste of certain sweets, and several participants described flavors as being “cool.”

Source of Messaging

Another major finding from the interviews was the importance of the source of the messaging and how the level of trust participants had toward the source of the messaging influenced their perceptions of tobacco and marijuana messages and, ultimately, the products.

Celebrities

Adolescents and young adults “follow” celebrities and influencers (ie, people who are famous through social media) and responded positively when celebrities and influencers posted about tobacco and marijuana. Sometimes this social media messaging was unsponsored and simply the celebrity showcasing his or her lifestyle and using tobacco or marijuana. A few participants discussed musicians and song lyrics as one way they were exposed to tobacco and marijuana in a positive way. Several participants who “followed” these musicians on various social media platforms saw them smoking cigars and marijuana.

Lack of trust in industry

Generally, participants had a negative view on industry-created messaging, especially related to tobacco. Participants reported awareness of the tobacco industry’s underlying profit-driven motives, described the importance of trusting the source of messages, and discussed their tendencies to not trust messages that came from the tobacco industry.

Peers over industry

Participants consistently described both the online and in-person messaging of tobacco and marijuana from their peers as more influential than industry messaging and more likely to lead to use. The importance of peer influence is especially true for marijuana, with recreational marijuana being legalized in an increasing number of states. One nonuser described the influence of friends on changing the participant’s negative opinions about marijuana. Another nonuser described how increased exposure to marijuana and JUUL messaging was mainly the result of observing the participant’s friends’ activity and interactions on social media.

Participants described the use of tobacco and marijuana products as a status symbol to appear “cool,” and they posted images of themselves using various products as almost a sign of social status.

Agency

Having agency, or personal choice and the ability to fully make decisions for oneself, was a key theme that emerged through the interviews. Participants described disliking anti-tobacco and/or anti-marijuana messaging, reporting that these messages violate their ability to make their own decision. Participants described thinking that exposure to pro-tobacco and/or pro-marijuana messaging from social media or even song lyrics did not sway their decisions about whether to use tobacco and/or marijuana products.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first qualitative study to examine adolescent and young adult interactions with and perceptions of tobacco and marijuana messaging on social media platforms. Our findings help bridge the gap in the literature that is currently limited to quantitative analyses of tobacco and marijuana messaging on social media platforms.15

We examined ways that adolescents and young adults interact with tobacco and marijuana messaging on various social media platforms and what they find most appealing about these messages. Findings that emerged included the importance of sharing and privacy, the direct appeal of online messaging to adolescents and young adults, the value of trusting the source, and the role of general attitudes and personal choice in decision-making related to using tobacco and marijuana. Adolescents and young adults in our study found messaging that includes colors, interesting packaging, and appealing flavors the most memorable, and they were especially attentive to messages from young people and influencers rather than from the tobacco or marijuana industry.

Studies show that flavors are a powerful influence on adolescents’ and young adults’ decisions to try e-cigarettes, adolescents and young adults view flavored advertisements as targeting them, and flavors contribute to the perception that these products are less harmful than combustible cigarettes.27-30 Our results support these findings. Participants in our study described the attractive packaging and flavors of e-cigarettes, which indicates the need for stricter policies and regulation of tobacco and marijuana marketing than what currently exists. Tobacco and marijuana prevention curricula need to focus more on addressing the harm-reduction messaging that exists online and on how social media platforms can misconstrue the evident risks of these products and misinform adolescents and young adults.31 Qualitative studies have found that this lack of information about emerging products contributes to perceptions of safety for products such as e-cigarettes and marijuana.32,33

In our study, trust in the source of messaging emerged as a key factor in adolescents’ and young adults’ interpretation of online tobacco and marijuana messages. Participants in our study described thinking highly of the ideas spread by friends, social media influencers, musicians, celebrities, and/or role models, which corroborates previous research.3,34 In our study, friends’ posts had the highest credibility, which confirms research suggesting that messaging generated by adolescents, young adults, and influencers can advertise for the tobacco and marijuana industries.11 Recent evidence that companies such as JUUL use celebrities and young-looking influencers plays into this idea of trusting the source.3,7

Because adolescents and young adults reported trusting peers and celebrities more than the industry, popular media figures and influencers could be encouraged to post prevention messaging on tobacco and marijuana products. This counter-marketing should include visually appealing imagery tailored to the target age group, use adolescent and young adult–approved humor, highlight industries’ ulterior motives, and emphasize personal choice. Some weaknesses that adolescents and young adults saw in tobacco and marijuana messaging that should be considered when developing counter-messaging are text-heavy or complicated messaging, sounding “preachy,” and clearly originating from a for-profit company. Creative mass-media campaigns have proven to be effective in tobacco prevention and should continue to include these evidence-based components that appeal to adolescents and young adults.35,36 It is important to incorporate what adolescents and young adults find appealing when developing programs to empower adolescents and young adults with skills to better recognize industry marketing influences.37

As the tobacco industry has known for years, adolescents and young adults are susceptible to emotional appeals, social influences, and mere exposure to product advertisements.10,38,39 The tobacco industry has a history of using marketing strategies that are attractive to adolescents and young adults, and it continues to use these strategies.4,5,40 Current online tobacco and marijuana messaging still includes these characteristics, and participants described these advertisements as appealing and memorable. Social media platforms have policies to exclude tobacco marketing,41 yet these methods prove insufficient if adolescents and young adults are directly sharing content with their peers.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the sample size was small. A similar study with a larger sample size would add to the literature. Second, all participants had attended high school in California; as such, the results from this sample may not be generalizable to all populations, especially in states with less restrictive tobacco control policies or in states that have not legalized recreational marijuana. The fact that all participants were from California may also affect the exposure to advertising and social media messages, as well as general attitudes toward marijuana and smoking. Despite these limitations, this study provides novel information on adolescent and young adult interaction behaviors with tobacco and marijuana messaging on popular social media platforms and communicates the perspectives of this population.

Conclusion

Fast-evolving technology allows companies to advertise on newer, more effective platforms compared with traditional print and media marketing. The effect of these newer forms of marketing is most evident in JUUL’s ability to gain popularity and spread throughout social media.11,16 It is imperative that public health research and policy respond to these advancements. Despite their highly unregulated nature, social media and online campaigns can also be a powerful tool in delivering future health interventions.35,36,42 If adolescents and young adults are educated about their role in propagating tobacco and marijuana industries’ tactics through social media, adolescents and young adults can be taught to better understand what and why they are influenced. Ultimately, the importance that agency, or personal choice, has for adolescents and young adults in their decision-making processes can empower them to positively influence their peer networks, both in person and online.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Trace Kershaw, PhD, the department chair of social and behavioral sciences at the Yale School of Public Health, for his review of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this article was supported by grant no. 1P50CA180890 from the National Cancer Institute and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products and grant no. U54 HL147127 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the FDA.

ORCID iD

Jessica Liu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8455-0127

References

- 1. Johnston LD., Miech RA., O’Malley PM., Bachman JG., Schulenberg JE., Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2018: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Institute for Social Research; 2019. Accessed April 27, 2020 http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2018.pdf

- 2. Kann L., McManus T., Harris WA. et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1-114. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Phua J., Jin SV., Hahm JM. Celebrity-endorsed e-cigarette brand Instagram advertisements: effects on young adults' attitudes towards e-cigarettes and smoking intentions. J Health Psychol. 2018;23(4):550-560. 10.1177/1359105317693912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Allem JP., Cruz TB., Unger JB., Toruno R., Herrera J., Kirkpatrick MG. Return of cartoon to market e-cigarette-related products. Tob Control. 2019;28(5):555-557. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coombs J., Bond L., Van V., Daube M. Below the line: the tobacco industry and youth smoking. Australas Med J. 2011;4(12):655-673. 10.4066/AMJ.2011.1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pokhrel P., Fagan P., Herzog TA. et al. Social media e-cigarette exposure and e-cigarette expectancies and use among young adults. Addict Behav. 2018;78:51-58. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grana RA., Ling PM. “Smoking revolution”: a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(4):395-403. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lovato C., Linn G., Stead LF., Best A. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;4:CD003439. 10.1002/14651858.CD003439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Landman A., Ling PM., Glantz SA. Tobacco industry youth smoking prevention programs: protecting the industry and hurting tobacco control. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):917-930. 10.2105/AJPH.92.6.917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ling PM., Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):908-916. 10.2105/AJPH.92.6.908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang J., Duan Z., Kwok J. et al. Vaping versus JUULing: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tob Control. 2019;28(2):146-151. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fiala SC., Dilley JA., Firth CL., Maher JE. Exposure to marijuana marketing after legalization of retail sales: Oregonians’ experiences, 2015-2016. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(1):120-127. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bernat D., Gasquet N., Wilson KO., Porter L., Choi K. Electronic cigarette harm and benefit perceptions and use among youth. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(3):361-367. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clark EM., Jones CA., Williams JR. et al. Vaporous marketing: uncovering pervasive electronic cigarette advertisements on Twitter. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0157304. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Allem JP., Dharmapuri L., Unger JB., Cruz TB. Characterizing JUUL-related posts on Twitter. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;190:1-5. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kavuluru R., Han S., Hahn EJ. On the popularity of the USB flash drive–shaped electronic cigarette JUUL. Tob Control. 2019;28(1):110-112. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramamurthi D., Gall PA., Ayoub N., Jackler RK. Leading-brand advertisement of quitting smoking benefits for e-cigarettes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(11):2057-2063. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moreno MA., Gower AD., Jenkins MC. et al. Social media posts by recreational marijuana companies and administrative code regulations in Washington State. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e182242. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bierut T., Krauss MJ., Sowles SJ., Cavazos-Rehg PA. Exploring marijuana advertising on Weedmaps, a popular online directory. Prev Sci. 2017;18(2):183-192. 10.1007/s11121-016-0702-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krauss MJ., Sowles SJ., Sehi A. et al. Marijuana advertising exposure among current marijuana users in the U.S. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;174:192-200. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jackler RK., Ramamurthi D. Unicorns cartoons: marketing sweet and creamy e-juice to youth. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):471-475. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thrul J., Lisha NE., Ling PM. Tobacco marketing receptivity and other tobacco product use among young adult bar patrons. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(6):642-647. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCausland K., Maycock B., Leaver T., Jancey J. The messages presented in electronic cigarette–related social media promotions and discussion: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(2):e11953. 10.2196/11953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McKelvey K., Halpern-Felsher B. From tobacco-endgame strategizing to Red Queen’s race: the case of non-combustible tobacco products. Addict Behav. 2019;91:1-4. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roditis M., Delucchi K., Cash D., Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ perceptions of health risks, social risks, and benefits differ across tobacco products. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(5):558-566. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dedoose [web application for managing data]. Version 8.0.35. Dedoose; 2018.

- 27. Zare S., Nemati M., Zheng Y. A systematic review of consumer preference for e-cigarette attributes: flavor, nicotine strength, and type. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194145. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morean ME., Butler ER., Bold KW. et al. Preferring more e-cigarette flavors is associated with e-cigarette use frequency among adolescents but not adults. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0189015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harrell MB., Loukas A., Jackson CD., Marti CN., Perry CL. Flavored tobacco product use among youth and young adults: what if flavors didn’t exist? Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(2):168-173. 10.18001/TRS.3.2.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Camenga DR., Fiellin LE., Pendergrass T., Miller E., Pentz MA., Hieftje K. Adolescents’ perceptions of flavored tobacco products, including e-cigarettes: a qualitative study to inform FDA tobacco education efforts through videogames. Addict Behav. 2018;82:189-194. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu J., Halpern-Felsher B. The JUUL curriculum is not the jewel of tobacco prevention education. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(5):527-528. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roditis ML., Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ perceptions of risks and benefits of conventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and marijuana: a qualitative analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(2):179-185. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Getachew B., Payne JB., Vu M. et al. Perceptions of alternative tobacco products, anti-tobacco media, and tobacco regulation among young adults: a qualitative study. Am J Health Behav. 2018;42(4):118-130. 10.5993/AJHB.42.4.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shadel WG., Tharp-Taylor S., Fryer CS. How does exposure to cigarette advertising contribute to smoking in adolescents? The role of the developing self-concept and identification with advertising models. Addict Behav. 2009;34(11):932-937. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crosby K., Santiago S., Talbert EC., Roditis ML., Resch G. Bringing “The Real Cost” to life through breakthrough, evidence-based advertising. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(2 suppl 1):S16-S23. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brubach AL. The case and context for “The Real Cost” campaign. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(2 suppl 1):S5-S8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Douglas M., Chan A., Sampilo M. Youth advocates’ perceptions of tobacco industry marketing influences on adolescent smoking: can they see the signs? AIMS Public Health. 2016;3(1):83-93. 10.3934/publichealth.2016.1.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Padon AA., Maloney EK., Cappella JN. Youth-targeted e-cigarette marketing in the US. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(1):95-101. 10.18001/TRS.3.1.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arnett JJ., Terhanian G. Adolescents’ responses to cigarette advertisements: links between exposure, liking, and the appeal of smoking. Tob Control. 1998;7(2):129-133. 10.1136/tc.7.2.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McKelvey K., Baiocchi M., Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ and young adults’ use and perceptions of pod-based electronic cigarettes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183535. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jackler RK., Li VY., Cardiff RAL., Ramamurthi D. Promotion of tobacco products on Facebook: policy versus practice. Tob Control. 2019;28(1):67-73. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Villanti AC., Johnson AL., Ilakkuvan V., Jacobs MA., Graham AL., Rath JM. Social media use and access to digital technology in US young adults in 2016. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(6):e196. 10.2196/jmir.7303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]