Abstract

Background:

Pulmonary coagulopathy has become an important therapeutic target in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). We hypothesized that combining intravenous recombinant human antithrombin (rhAT), nebulized heparin and nebulized tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) more effectively improves pulmonary gas exchange than a single rhAT infusion, while maintaining the antiinflammatory properties of rhAT in ARDS. Therefore, the present prospective, randomized experiment was conducted using an established ovine model.

Methods:

Following burn and smoke inhalation injury (40% of total body surface area, 3rd degree flame burn; 4×12 breaths of cold cotton smoke), eighteen chronically instrumented sheep were randomly assigned to receive intravenous saline plus saline nebulization (control), intravenous rhAT (6 IU·kg−1·h−1) started 1h post injury plus saline nebulization (AT i.v.) or intravenous rhAT combined with nebulized heparin (10,000 IU every 4h, started 2h post injury) and nebulized TPA (2 mg every 4h, started 4h post injury) (triple therapy, n=6 each). All animals were mechanically ventilated and fluid resuscitated according to standard protocols during the 48h-study period.

Results:

Both treatment approaches attenuated ARDS compared with control animals. Notably, triple therapy was associated with an improved PaO2/FiO2-ratio (p=0.007), attenuated pulmonary obstruction (p=0.02) and shunting (p=0.025) as well as reduced ventilatory pressures (p<0.05 each) vs. AT i.v. at 48h. However, the antiinflammatory effects of sole AT i.v., namely the inhibition of neutrophil activation (neutrophil count in the lymph and pulmonary polymorphonuclear cells, p<0.05 vs. control each), pulmonary transvascular fluid flux (lymph flow, p=0.004 vs. control) and systemic vascular leakage (cumulative net fluid balance, p<0.001 vs. control), were abolished in the triple therapy group.

Conclusions:

Combining intravenous rhAT with nebulized heparin and nebulized TPA more effectively restores pulmonary gas exchange, but the antiinflammatory effects of sole rhAT are abolished with the triple therapy. Interferences between the different anticoagulants may represent a potential explanation for these findings.

Keywords: acute lung injury, anticoagulants, burn and smoke inhalation injury, fluid accumulation, vascular leakage

Level of Evidence: randomized, controlled, therapeutic, experimental study

Background

Pulmonary coagulopathy has become an important therapeutic target in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (1–3). This treatment strategy is based on the reduction of intrapulmonary coagulation resulting in an improved oxygenation. In addition, anticoagulants, like antithrombin III (AT), also provide multiple antiinflammatory effects (4), thereby targeting the second hallmark of ARDS. Accordingly, numerous experimental and clinical studies have been performed with different compounds (5, 6). However, a definitive treatment recommendation is still lacking (7).

ARDS caused by combined burn and smoke inhalation injury is associated with a distinct and sustained pulmonary coagulopathy (2) resulting in airway cast formation and severe impairment of oxygenation (8, 9). Recently, an intravenous infusion of recombinant human AT (rhAT) reduced pulmonary inflammation and leakage via inhibiting neutrophil activation in an ovine model of burn and smoke inhalation injury (10). In respect to pulmonary gas exchange, however, treated animals still suffered from moderate ARDS after 48h. To improve oxygenation, the combination of rhAT with nebulized anticoagulants might be advantageous over a sole rhAT infusion. In this context, the nebulization of heparin (11, 12) and the nebulization of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) (13, 14) have been shown to improve pulmonary function.

In the present study, we hypothesized that the combined treatment approach using intravenous rhAT, nebulized heparin and nebulized TPA more effectively improves pulmonary gas exchange than a sole rhAT infusion, while maintaining the anti-inflammatory properties of rhAT in a clinically relevant, established ovine model of ARDS (10, 15, 16). Therefore, the present prospective, randomized, controlled laboratory experiment was designed to elucidate the effects of the combined therapeutic approach on pulmonary gas exchange and edema,.

Methods

The study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston and conducted in compliance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health.

Instrumentation and Surgical Procedures

Eighteen female sheep were anesthetized and instrumented for chronic hemodynamic monitoring using an established protocol (10, 15, 16). Details on the instrumentation are provided in the supplemental digital content 1.

Experimental Protocol

After five days of recovery, baseline (BL) measurements were performed. Following tracheostomy and placement of an urinary bladder catheter, sheep were subjected to a 40% of total body surface area, 3rd degree flame burn and 4×12 breaths of cold cotton smoke under deep anesthesia using an established protocol (10, 15, 16). The sheep were then awakened and randomly assigned to the study groups (n=6 each): control (injured, continuous infusion and intermittend nebulization of vehicle [NaCl 0.9%]), AT i.v. (injured, continuous infusion of 6 IU·kg−1·h−1 rhAT (GTC Biotherapeutics, Framingham, MI, USA) from 1h post injury until the end of the study period, intermittend nebulization of vehicle [NaCl 0.9%]), or triple therapy (injured, continuous infusion of 6 IU·kg−1·h−1 rhAT from 1h post injury until the end of the study period, nebulization of heparin (10.000 IU each; American Pharmaceutical Partners, Schaumburg, IL, USA) and TPA (2 mg each; Alteplase, Genentech, San Francisco, CA, USA) every 4 h starting 2h and 4h post injury, respectively). The investigators were unaware of the animals group assignment.

During the experiment, all animals were deprived from drinking water and equally resuscitated with intravenous lactated Ringer’s solution according to the formula: 4 mL·kg−1·% burned body surface area−1 within 24h (17). To compensate for the burn-induced hypovolemia, sheep received 50% of the fluid amount calculated for 24h within the first 8h after injury. In addition, the animals were ventilated according to an established protocol (online methods supplement) to maintain sufficient oxygenation (arterial oxygen saturation >95%, partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) >90 mmHg), whenever possible. ARDS was defined according to the “Berlin Definition” as mild, moderate or severe (18). After 48h, sheep were deeply anesthetized with ketamine and euthanized by injection of 60 mL of saturated potassium chloride.

Cardiopulmonary hemodynamics, gas exchange and laboratory analyses

Hemodynamic measurements and analyses of arterial blood gases, plasma and lymph samples for determination of AT and protein concentration, nitrites and nitrates (NOx), variables of plasmatic coagulation and neutrophil counts in the lymph were performed at specific time points. Details on these measurements are provided in the supplemental digital content 1.

Histological analyses

Histological analyses and assessment of bloodless lung wet-to-dry weight ratio were performed as reported before (19, 20). Details on these measurements are provided in the supplemental digital content 1.

Statistical Analyses

Sigma Stat 3.1 software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) was used for statistical analyses. After confirming normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and equal variance (Levene test), analysis of variance methodologies appropriate for two factor experiments with repeated measures across time for each animal were used. Each variable was analyzed separately for differences among groups, across time, and for group by time interaction. After confirming the significance of different group effects over time, post hoc pair-wise comparisons among groups were performed using the Student-Newman-Keuls procedure. Compared to other post hoc tests, the Student-Newman-Keuls test is more likely to detect significant differences in multiple testing. Wet-to-dry-weight ratio and histological scores were compared with one-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis. The Holm-Sidak comparison was used, because it is very powerful and can be also used for tests with inhomogeneous variance. All the analyses were performed as two-tailed tests. Data are presented as mean±SEM. Differences were considered as statistically significant, when p was less than 0.05.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

There were no differences among study groups in any of the investigated variables at BL. Mean body weight (control: 34±3kg vs. AT i.v.: 32±2kg vs. triple therapy: 34±2kg, p=0.805) and carboxyhemoglobin values after the smoke inhalation, as an index of the severity of injury, did not differ among groups (control: 60±9% vs. AT i.v.: 63±9% vs. triple therapy: 61±3% p=0.968).

Pulmonary function and mechanical ventilation

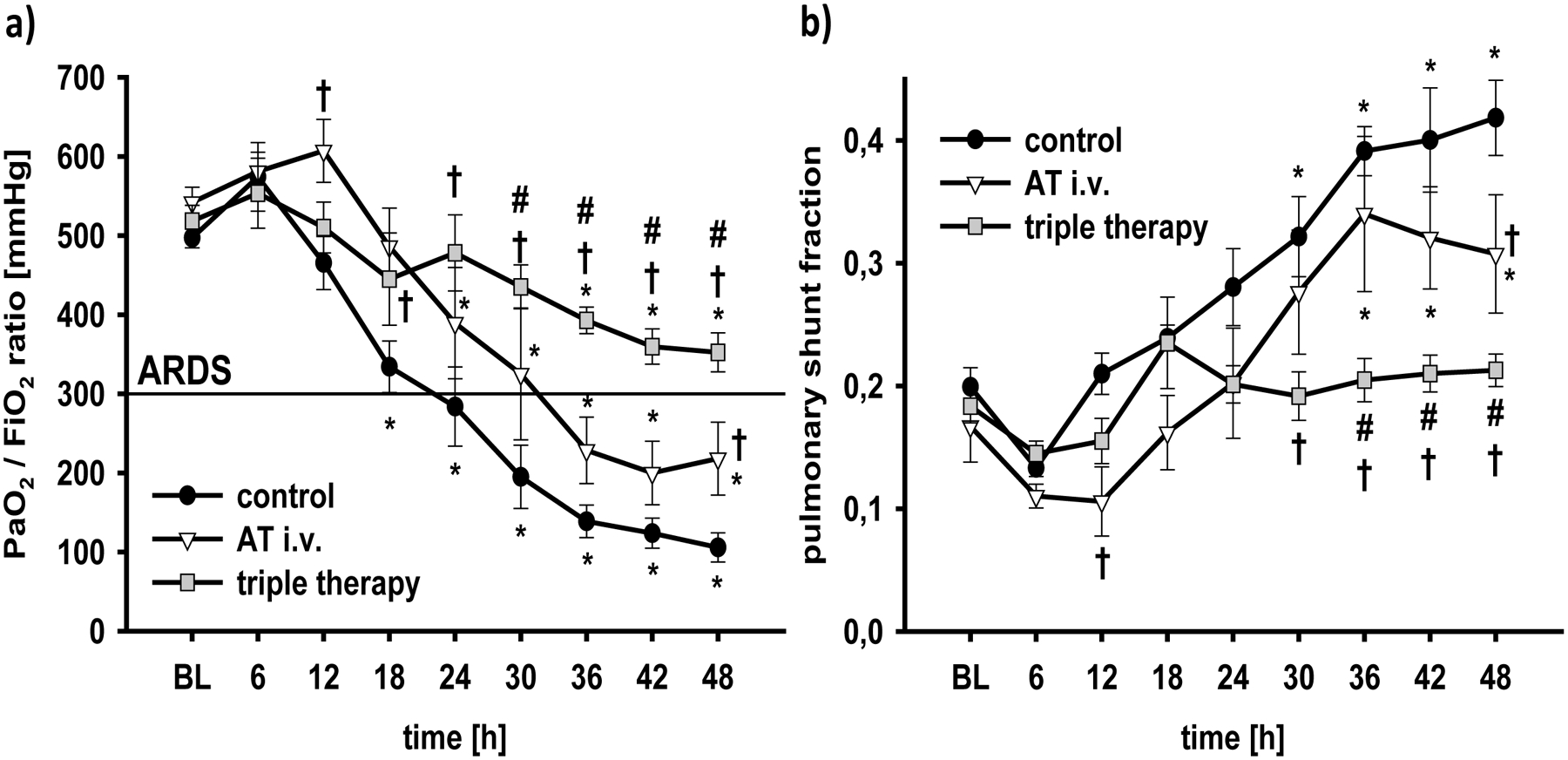

In control animals, burn and smoke inhalation injury decreased the PaO2/FiO2 ratio below the ARDS defining value of 300 mmHg at 24h post injury and to severe ARDS at the end of the 48h-study period (p<0.001 vs. BL, Fig. 1a). Whereas sole AT i.v. attenuated the deterioration of pulmonary gas exchange to moderate ARDS at 48h, the PaO2/FiO2 ratio in the triple therapy group never fulfilled the ARDS criteria and was higher than in both other groups (24–48h: p<0.01 vs. control each; 30–48h: p<0.05 vs. AT i.v. each). In addition, PaO2 (each p<0.05 vs. AT i.v.) and SaO2 (each p<0.05 vs. AT i.v.) in the triple therapy group, but not with sole AT i.v., were significantly higher than in control animals from 36h-48h (Tab.1). Pulmonary shunt fraction was doubled from about 20% to more than 40% in control animals within 48h (48h: p<0.001 vs. BL; Fig. 1b). This increase was attenuated in the AT i.v. group (48h: p=0.013 vs. control). The triple therapy prevented this increase and kept pulmonary shunt fraction at baseline level (36–48h: p<0.05 vs. AT i.v. and control each).

Fig 1. PaO2/FiO2 ratio (a) and pulmonary shunt fraction (b).

*p < 0.05 vs. baseline; †p < 0.05 vs. control; #, p < 0.05 vs. AT i.v. n = 6 per group

BL, baseline; AT, recombinant human antithrombin III; triple therapy, recombinant human antithrombin III i.v., nebulized heparin and nebulized tissue plasminogen activator

To improve oxygenation, airway pressures and the respiratory rate for mechanical ventilation had to be progressively increased in control animals (48h: p<0.001 vs. BL each, Table 1). Whereas the respiratory rate was lower in both treatment groups (48h: p≤0.001 vs. control each), only the triple therapy was associated with significant reductions in peak and plateau pressures (36–48h: p<0.01 vs. control each)

Table 1.

Pulmonary gas exchange and ventilatory parameters

| Variable | Group | BL | 6h | 12 h | 24 h | 36 h | 48 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SaO2 | control | 91 ± 1 | 93 ± 1 | 90 ± 1 | 90 ± 2 | 85 ± 2* | 88 ± 2 |

| (%) | AT i.v. | 93 ± 1 | 94 ± 0 | 95 ± 1† | 90 ± 2 | 89 ± 3 | 93 ± 2 |

| triple | 93 ± 0 | 93 ± 0 | 93 ± 1 | 92 ± 1 | 91 ± 1† | 92 ± 1† | |

| PaO2 | control | 104 ± 3 | 154 ± 12* | 101 ± 6 | 104 ± 11 | 84 ± 6 | 86 ± 6 |

| (mmHg) | AT i.v. | 108 ± 4 | 140 ± 11* | 128 ± 8† | 95 ± 9 | 100 ± 11 | 110 ± 12 |

| triple | 109 ± 4 | 133 ± 10* | 117 ± 7 | 125 ± 11# | 108 ± 8† | 117 ± 5† | |

| PaCO2 | control | 40 ± 1 | 30 ± 2* | 30 ± 1* | 34 ± 3 | 44 ± 8 | 41 ± 8 |

| (mmHg) | AT i.v. | 40 ± 3 | 30 ± 1* | 27 ± 2* | 30 ± 1* | 45 ± 11 | 41 ± 3 |

| triple | 38 ± 0 | 31 ± 2* | 29 ± 1* | 28 ± 1* | 30 ± 2* | 32 ± 2* | |

| Resp. rate | control | 20 ± 0 | 20 ± 0 | 22 ± 2 | 22 ± 1 | 29 ± 3* | 37 ± 4* |

| (breaths∙min−1) | AT i.v. | 20 ± 0 | 20 ± 1 | 20 ± 0 | 20 ± 0 | 24 ± 3 | 27 ± 3*† |

| triple | 20 ± 0 | 20 ± 0 | 22 ± 1 | 22 ± 1 | 22 ± 1† | 23 ± 1† | |

| PPeak | control | 18 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 | 23 ± 2 | 26 ± 3* | 36 ± 2* | 37 ± 1* |

| (cmH2O) | AT i.v. | 19 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 | 21 ± 1 | 24 ± 3 | 28 ± 4* | 32 ± 3* |

| triple | 20 ± 0 | 19 ± 1 | 20 ± 2 | 22 ± 1 | 25 ± 1† | 27 ± 1*† | |

| PPlateau | control | 16 ± 1 | 17 ± 1 | 21 ± 3 | 24 ± 3* | 35 ± 4* | 35 ± 2* |

| (cmH2O) | AT i.v. | 17 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | 20 ± 2 | 26 ± 5* | 31 ± 4* |

| triple | 18 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 | 23 ± 1† | 25 ± 1*† |

p<0.05 vs. BL;

p<0.05 vs. control;

p<0.05 vs. AT i.v. each group n = 6

AT, antithrombin; BL, baseline; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen; PPeak, ventilatory peak pressure; PPlateau, ventilatory plateau pressure; resp, respiratory; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation; triple, intravenous recombinant human antithrombin III combined with nebulized heparin and tissue plasminogen activator

Pulmonary transvascular fluid flux and systemic fluid accumulation

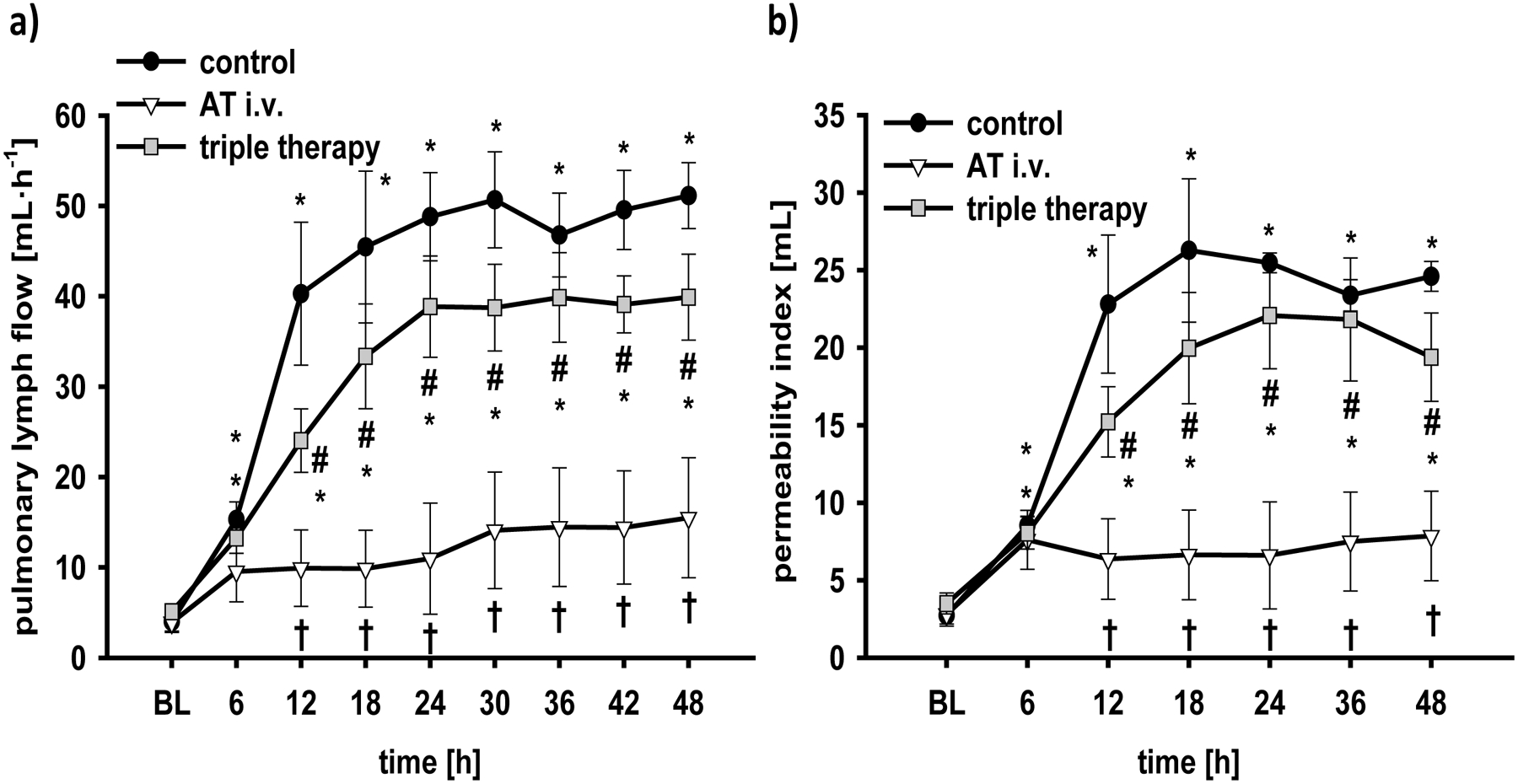

Following the injury, pulmonary lymph flow increased ~10fold in control animals within 24h and stayed at this level during the second day (6–48h: p<0.001 vs. BL each, Fig. 2a). Sole AT i.v. markedly attenuated this increase (12–48h: p<0.01 vs. control each). The triple therapy, however, did not significantly reduce pulmonary lymph flow, resulting in higher lymph flows than in the AT i.v. group (12–48h: p<0.05 each). The calculated pulmonary permeability index revealed similar results for the individual groups (Fig. 2b), i.e. a significant reduction in animals treated with AT i.v. compared with control animals (12–48h: p<0.05 each) and higher values for the triple therapy than for the AT i.v. group (12–48h: p<0.05 each).

Fig 2. Pulmonary lymph flow (a) and pulmonary permeability index (b).

*p < 0.05 vs. baseline; †p < 0.05 vs. control; #, p < 0.05 vs. AT i.v. n = 6 per group

BL, baseline; AT, recombinant human antithrombin III; triple therapy, recombinant human antithrombin III i.v., nebulized heparin and nebulized tissue plasminogen activator

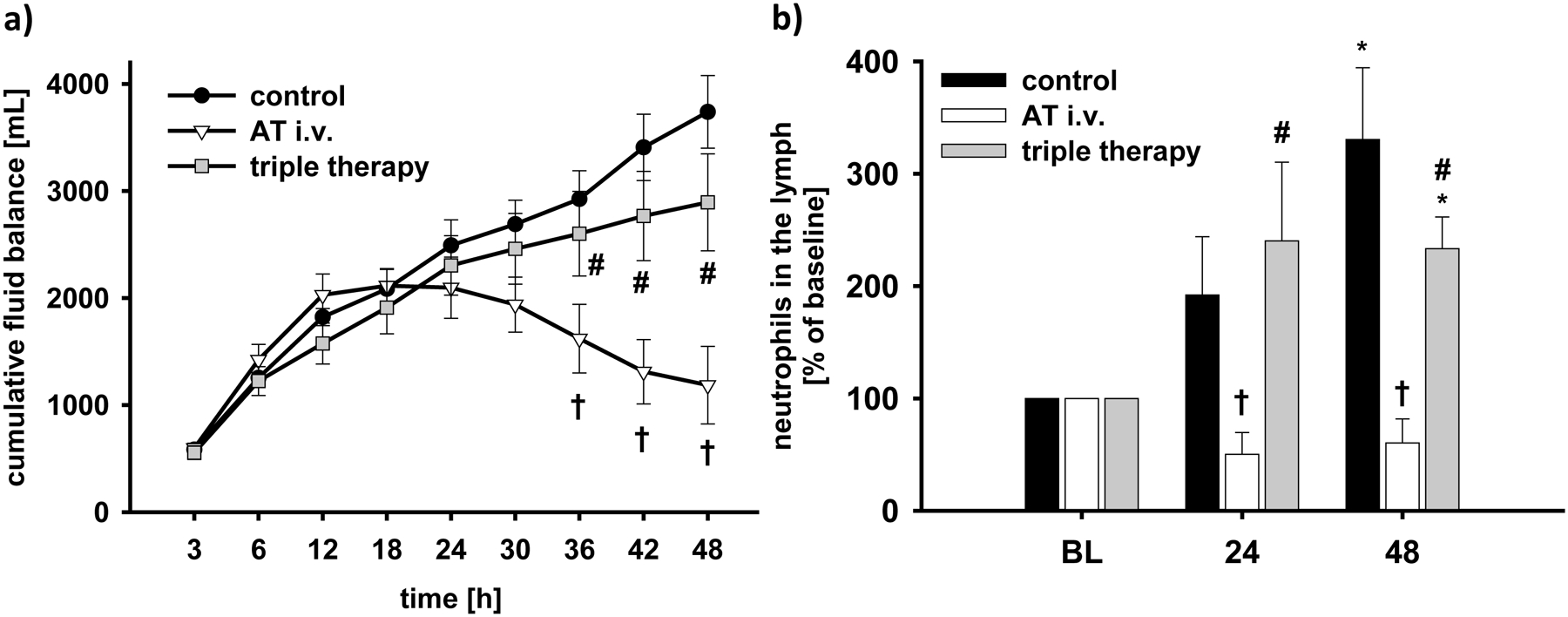

Systemic permeability was evidenced by decreases in plasma protein concentrations in all study groups already at 6h post injury (p<0.001 vs. BL each; Table 2). Whereas plasma protein concentration progressively decreased in the control and triple therapy groups, it did not in AT i.v.-treated animals resulting in higher protein concentrations (24–48h: p<0.05 vs. control and vs. triple therapy, respectively). At the same time, hematocrit was maintained at BL level in all study groups without statistical differences between study groups (Table 2). Whereas fluid substitution was the same for each animal (after adjusting for the individual body weight), urine flow was higher in the AT i.v. group than in both other groups (24–48h: p<0.05 vs. control each; p<0.01 vs. triple therapy each; Table 2). As a consequence, cumulative net fluid balance continuously increased up to almost 4L in control and 3L in triple therapy-treated animals at 48h (Fig. 3a). Contrary, fluid accumulation was reduced in the AT i.v. group (36–48h: p<0.05 vs. control and triple therapy each).

Table 2.

Laboratory analyses and urine flow

| Variable | Group | BL | 6h | 12 h | 24 h | 36 h | 48 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT plasma | control | 100 ± 0 | 79 ± 4* | 77 ± 3* | 64 ± 3* | 65 ± 4* | 69 ± 4* |

| (% of BL) | AT i.v. | 100 ± 0 | 98 ± 3† | 107 ± 3† | 98 ± 5† | 105 ± 6† | 104 ± 5† |

| triple | 100 ± 0 | 101 ± 3† | 97 ± 3† | 93 ± 4† | 96 ± 3† | 95 ± 6† | |

| Hematocrit | control | 24 ± 1 | 25 ± 2 | 27 ± 1 | 28 ± 2 | 30 ± 3* | 28 ± 2 |

| (%) | AT i.v. | 25 ± 2 | 23 ± 2 | 25 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | 26 ± 2 |

| triple | 26 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | 28 ± 2 | 28 ± 1 | 29 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 | |

| Proteinplasma | control | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.1* | 4.6 ± 0.1* | 4.1 ± 0.1* | 3.9 ± 0.2* | 4.0 ± 0.3* |

| (g∙dL−1) | AT i.v. | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.2* | 5.0 ± 0.1* | 4.6 ± 0.1*† | 4.8 ± 0.2*† | 4.9 ± 0.3*† |

| triple | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.2* | 4.5 ± 0.1* | 4.1 ± 0.1*# | 4.2 ± 0.2*# | 3.9 ± 0.2*# | |

| NOxplasma | control | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 7.1 ± 0.5* | 10.7 ± 0.7* | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 0.8* | 7.1 ± 0.6* |

| (μM) | AT i.v. | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 5.1 ± 0.4*† | 4.4 ± 0.4*† | 2.4 ± 0.2† | 2.9 ± 0.1† | 2.3 ± 0.3† |

| triple | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.3*† | 4.5 ± 0.3*† | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.4† | 2.5 ± 0.5† | |

| Urine flow | control | / | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.4 |

| (mL∙kg−1∙h−1) | AT i.v. | / | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.6† | 4.9 ± 0.7† | 3.5 ± 0.3† |

| triple | / | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 0.3# | 1.3 ± 0.3# | 1.2 ± 0.3# |

p<0.05 vs. BL;

p<0.05 vs. control;

p<0.05 vs. AT i.v.; each group n = 6

AT, antithrombin; AT i.v., intravenous recombinant human antithrombin III; BL, baseline; NOx, nitrates and nitrites; triple, recombinant human antithrombin III i.v., nebulized heparin and nebulized tissue plasminogen activator

Fig 3. Cumulative fluid balance (a) and neutrophil count in the lymph (b).

*p < 0.05 vs. baseline; †p < 0.05 vs. control; #, p < 0.05 vs. AT i.v. n = 6 per group

BL, baseline; AT, recombinant human antithrombin III; triple therapy, recombinant human antithrombin III i.v., nebulized heparin and nebulized tissue plasminogen activator

Cardiovascular hemodynamics

Changes in cardiovascular hemodynamics are depicted in the supplemental digital content 2 (Table 1). There were no statistical differences over time or between groups in mean arterial pressure. Heart rate was higher in control animals than in the AT i.v. (24–48h: p<0.05 each) and the triple therapy group (24–48h: p<0.05 each). Cardiac index (12–36h: p<0.05 vs. control and triple therapy each) and stroke volume index (12–48h: p<0.05 vs. control each; 36h: p=0.021 vs. triple therapy) were higher in animals treated with AT i.v. than in both other groups. Mean pulmonary artery pressures and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure increased in all study groups compared to BL without statistical differences between groups (48h: p≤0.01 each).

Variables of coagulation, nitrosative stress and neutrophil migration

Following the injury, AT plasma levels decreased in control animals (6–48h: p<0.001 vs. BL; Table 2). The infusion of 6 IU·kg−1·h−1 rhAT maintained AT plasma levels at BL level in both treatment groups (6–48h: p<0.01 vs. control each). Measurements of activated clotting time, prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time did not reveal any persistent significant differences among study groups (supplemental digital content 2: Table 2). There only was a higher prothrombin time in the AT i.v. group than in the triple therapy group at 12h (p=0.045).

NOx plasma concentrations showed a biphasic increase in control animals with a first peak at 12h and a second one at 48h (p<0.001 vs. BL each; Table 2). Both treatment regimes attenuated the first increase (6–12h: p<0.01 vs. control each) and prevented the second one (36–48h: p<0.01 vs. control each).

Neutrophil counts in the lymph significantly increased in control and triple therapy-treated animals over the study period (48h: p<0.01 vs. BL each), but not in the AT i.v. group (24+48h: p<0.05 vs. control and triple therapy each; Fig. 3b). The amount of polymorphonuclear cells in the lung was lower in animals treated with AT i.v. than in control animals (p=0.048, Table 3).

Table 3.

Wet-to-dry-weight ratio and histological analyses

| Variable | control | AT i.v. | triple |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-to-dry-weight ratio | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.3† | 4.8 ± 0.2† |

| Obstruction bronchi (score) | 11.7 ± 2.2 | 4.6 ± 0.4† | 2.8 ± 0.5†# |

| Obstruction bronchioli (score) | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2† | 1.1 ± 0.2† |

| Alveolar edema (score) | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1† | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| Pulmonary PMN (score) | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.06 ± 0.05† | 0.13 ± 0.06 |

p<0.05 vs. control;

p<0.05 vs. AT i.v.; each group n = 6

AT i.v., intravenous recombinant human antithrombin III; PMN, polymorphonuclear cells triple, recombinant human antithrombin III i.v., nebulized heparin and nebulized tissue plasminogen activator

Airway obstruction and pulmonary edema

Scores for histological analyses are listed in Table 3. Both treatment strategies significantly reduced obstruction scores for bronchi and bronchioli compared with control animals (p≤0.01 vs. control each). In addition, triple therapy resulted in a lower obstruction score for bronchi than sole AT i.v. (p=0.02).

Bloodless wet-to-dry weight ratios of the lungs were significantly lower in both treatment groups than in control animals. The degree of alveolar edema was attenuated in both treatment groups as compared to control animals. However, the difference only reached statistical significance for the AT i.v. group (p=0.038), but not for the triple therapy group (p=0.087).

Discussion

The major findings of the present study are that the triple therapy combining intravenous rhAT with nebulized heparin and nebulized TPA reduced airway obstruction and pulmonary shunting thereby improving oxygenation and preventing the development of ARDS following burn and smoke inhalation in a clinically relevant ovine model, whereas the sole rhAT infusion did not. On the down side, the triple therapy failed to inhibit neutrophil activation thereby abolishing the reduction in pulmonary transvascular fluid flux and systemic fluid accumulation evidenced with sole rhAT infusion.

There is currently no “magic bullet” to effectively interfere with the complex interaction between coagulation and inflammation in ARDS. Thus, combined treatment approaches seem reasonable and have already been shown to be more effective than single therapies (8, 21). However, these therapeutic strategies need to be carefully tested for potential interactions in experimental trials before transferring them into the clinical setting. In the present study, a continuous rhAT infusion compensated for the burn-associated decrease in AT plasma levels, a known factor correlating with mortality in these patients (22). In addition, rhAT has been shown to reduce pulmonary and systemic inflammation via inhibition of neutrophil activation resulting in marked reductions of pulmonary edema and systemic fluid accumulation (10). These results are supported in the current study.

In the triple therapy group, rhAT infusion was combined with nebulized heparin and TPA. Due to its local anticoagulant effects and the prevention of cast formation, nebulized heparin has repeatedly been shown to improve pulmonary oxygenation in different experimental models of ARDS (8, 21, 23, 24) and clinical trials (11, 12, 25). The interval of 4h with a dose of 10,000 IU heparin for each nebulization has also been established in the experimental (21) and clinical setting as well (11, 25). Notably, higher doses did not provide any additional benefit, but were associated with impairment of systemic coagulation parameters (12, 26). However, no effects of nebulized heparin on inflammation were described (23). In addition, potential interactions between heparin and AT have to be taken into consideration. Whereas the anticoagulant effects of AT are promoted by heparin (27), the antiinflammatory properties are inhibited due to blockade of the pentasaccharide binding site of AT (28), the syndecan-4 receptor (29). To minimize this interaction, rhAT (intravenous) and heparin (nebulized) were administered via different routes.

TPA was added to dissolve already formed fibrin clots and cast formations. The effectiveness of nebulized TPA to increase fibrinolysis in the airways has been demonstrated not only in ARDS caused by smoke inhalation (13) but also pneumonia (14). The dose of 2 mg TPA for each nebulization was based on a previous study demonstrating beneficial effects on pulmonary coagulopathy only for 2 mg but not for 1 mg TPA (13). In summary, the triple therapy approach in the present study was expected to prevent and treat pulmonary coagulation via nebulization of heparin and TPA as well as to treat pulmonary and systemic inflammation via intravenous rhAT.

In agreement with this hypothesis, triple therapy more effectively improved pulmonary oxygenation by reducing pulmonary shunt fraction and airway obstruction in the larger airways compared with control and sole AT i.v.-treated animals. Accordingly, mechanical ventilation (airway pressures, respiratory rates) was significantly less invasive in the triple therapy than in both other groups. Interestingly, the benefits on oxygenation were more pronounced than with a dual approach of combined intravenous rhAT and nebulized heparin in a previous study in the same model (8) (PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 352±25mmHg vs. <250 mmHg after 48h, respectively) suggesting an additional benefit of nebulized TPA. Based on our present data, however, this hypothesis remains speculative, since it is not valid to compare results from different trials.

The current study also revealed potential pitfalls of the triple therapy approach. The antiinflammatory benefits of sole AT i.v., such as the reduction of pulmonary transvascular fluid flux, vascular leakage and systemic fluid accumulation, were abolished in the triple therapy group. The most probable explanation for this finding represents an interference of rhAT with heparin in the pulmonary and systemic compartment resulting in a blockade of rhAT-associated antiinflammatory effects. Thus, heparin must have leaked into the circulation. Although heparin plasma levels were not measured in the present experiment, this hypothesis is supported by the small size of heparin molecules (mean molecular weight 4–6 kDa) and previous reports about the impairment of systemic parameters of coagulation by nebulized heparin (6, 12).

Contrary to the present results, the combination of intravenous rhAT and nebulized heparin resulted in a significant reduction in pulmonary lymph flow and systemic fluid accumulation in a study of Enkhbaatar et al. in the same model (8) suggesting no significant interaction of rhAT and heparin. A potential explanation for these conflicting findings is the addition of TPA in the triple therapy group. The improved airway clearance might have promoted the leakage of heparin into the circulation. This hypothesis, however, needs to be confirmed in future trials, since we did dot investigate a combined rhAT and heparin group.

Another finding, that seems to be contradictive at the first sight, is the fact that not all the antiiflammatory effects of rhAT were abolished. The reduction in NOx plasma levels, for example, was comparable between both treatment groups. In this context, it is important to consider that rhAT provides both anticoagulant-dependant, i.e. mediated by a lower activity of coagulant factors such as thrombin, and anticoagulant-independant antiinflammatory effects mediated by interaction with the syndecan-4 receptor, for example (4). The anticoagulant-independant antiinflammatory effects, like the inhibition of neutrophil activation, were blocked by heparin, as suggested by the higher number of neutrophils in the pulmonary lymph and higher histological scores for polymorphonuclear cells in the lungs of the triple therapy group as compared to the AT i.v. group. Accordingly, the reduction of nitric oxide production probably represents an anticoagulant-dependant effect, that is not impaired by heparin. This hypothesis is supported by studies reporting thrombin-induced increases of nitric oxide production in endothelial cells (30, 31).

This study has some limitations that we want to acknowledge. Determination of plasma concentrations of heparin would have been helpful to support the hypothesis of heparin leakage into the systemic circulation. However, this has already been demonstrated previously (6). In addition, the experimental design with only two control groups limits the strength of our conclusion. A therapeutic approach consisting of three combined compounds would require numerous treated (single and dual therapies) and untreated control groups. Such an experimental design, however, would be confusing and the data presentation would be almost impossible. In addition, all of the three used compounds have been studied by our group as sole or as dual therapies in the same model before. Against this background, we decided to refer in our discussion to our previous work instead of increasing the number of control groups (especially since it was the same research group and the same model). Therefore, if appropriate, conclusions were worded as hypotheses in the discussion section. Considering the present experiment as part of a greater context, i.e. designing an optimized anticoagulant therapy for acute lung injury, several important questions answered and new hypotheses were raised with the present work. Another limitation represents the use of previously healthy animals, whereas the majority of patients typically suffer from co-morbidities. Finally, despite using statistical methods to adjust for multiple testing, the risk of false positive results in a study with numerous outcome variables and time points has to be taken into consideration.

In summary, this study demonstrates for the first time the benefits and pitfalls of combining an intravenous infusion of rhAT with nebulized heparin and nebulized TPA for the treatment of combined burn and smoke inhalation injury. Whereas the development of ARDS is prevented by improving oxygenation and airway clearance, the antiinflammatory effects of rhAT are lost due to a potential interaction with heparin and the subsequent failure of rhAT to inhibit neutrophil activation. The leakage of heparin into the systemic circulation might have been promoted by TPA. Future research is warranted to further optimize anticoagulant therapy for the treatment of ARDS before it is transferred into clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

1. Detailed methods

This file provides detailed information about the intrumentation, mechanical ventilation, hemodynamic monitoring, western blots as well as laboratory and immunohistochemical analyses.

2. Additional data:

This file provides tables with additional data that were recorded or determined during the experiment, but were of minor relevance for the discussion.

Acknowledgements

This work is dedicated to Prof. D.L. Traber, who significantly contributed to this manuscript, but passed away in September, 2012. The authors thank the technicians of the Investigational Intensive Care Unit for expert technical assistance during the study.

Founding: This work was supported by Shriners of North America (grant no. 85500, 85220 and 84050) and NIH (T32-GM8256, GM097480-2).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Meetings at which some content of this manuscript was presented:

Annual meeting of the American Burn Association

Annual meeting of the American Thoracic Society

References

- 1.Hofstra JJ, Haitsma JJ, Juffermans NP, Levi M, Schultz MJ. The role of bronchoalveolar Hemostasis in the pathogenesis of acute lung injury. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2008;34(5):475–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofstra JJ, Vlaar AP, Knape P, Mackie DP, Determann RM, Choi G, van der Poll T, Levi M, Schultz MJ. Pulmonary activation of coagulation and inhibition of fibrinolysis after burn injuries and inhalation trauma. J Trauma. 2011;70(6):1389–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz MJ, Haitsma JJ, Zhang H, Slutsky AS. Pulmonary coagulopathy as a new target in therapeutic studies of acute lung injury or pneumonia--a review. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3):871–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rehberg S, Traber DL, Enkhbaatar P. Update on antithrombin for the treatment of burn and smoke inhalation injury In: Vincent JL, editor. Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2010. p. 285–96. [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacLaren R, Stringer KA. Emerging role of anticoagulants and fibrinolytics in the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(6):860–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuinman PR, Dixon B, Levi M, Juffermans NP, Schultz MJ. Nebulized anticoagulants for acute lung injury - a systematic review of preclinical and clinical investigations. Crit Care. 2012;16(2):R70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehberg S, Enkhbaatar P, Traber DL. Anticoagulant therapy in acute lung injury: a useful tool without proper operating instruction? Crit Care. 2008;12(5):179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enkhbaatar P, Esechie A, Wang J, Cox RA, Nakano Y, Hamahata A, Lange M, Traber LD, Prough DS, Herndon DN, et al. Combined anticoagulants ameliorate acute lung injury in sheep after burn and smoke inhalation. Clin Sci (Lond). 2008;114(4):321–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rehberg S, Maybauer MO, Enkhbaatar P, Maybauer DM, Yamamoto Y, Traber DL. Pathophysiology, management, and treatment of smoke inhalation injury. Expert Rev Resp Med. 2009;3(3):283–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rehberg S, Yamamoto Y, Sousse LE, Jonkam C, Zhu Y, Traber LD, Cox RA, Prough DS, Traber DL, Enkhbaatar P. Antithrombin attenuates vascular leackage via inhibiting neutrophil activation in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2013;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon B, Schultz MJ, Smith R, Fink JB, Santamaria JD, Campbell DJ. Nebulized heparin is associated with fewer days of mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14(5):R180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon B, Santamaria JD, Campbell DJ. A phase 1 trial of nebulised heparin in acute lung injury. Crit Care. 2008;12(3):R64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enkhbaatar P, Murakami K, Cox R, Westphal M, Morita N, Brantley K, Burke A, Hawkins H, Schmalstieg F, Traber L, et al. Aerosolized tissue plasminogen inhibitor improves pulmonary function in sheep with burn and smoke inhalation. Shock. 2004;22(1):70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofstra JJ, Cornet AD, Declerck PJ, Dixon B, Aslami H, Vlaar AP, Roelofs JJ, van der Poll T, Levi M, Schultz MJ. Nebulized fibrinolytic agents improve pulmonary fibrinolysis but not inflammation in rat models of direct and indirect acute lung injury. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enkhbaatar P, Connelly R, Wang J, Nakano Y, Lange M, Hamahata A, Horvath E, Szabo C, Jaroch S, Holscher P, et al. Inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase in ovine model of acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(1):208–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westphal M, Enkhbaatar P, Schmalstieg FC, Kulp GA, Traber LD, Morita N, Cox RA, Hawkins HK, Westphal-Varghese BB, Rudloff HE, et al. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibition attenuates cardiopulmonary dysfunctions after combined burn and smoke inhalation injury in sheep. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baxter CR, Shires T. Physiological response to crystalloid resuscitation of severe burns. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;150(3):874–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camporota L, Antonelli M, Anzueto A, Beale R, Brochard L, Brower R, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, et al. The Berlin definition of ARDS: an expanded rationale, justification, and supplementary material. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(10):1573–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox RA, Burke AS, Soejima K, Murakami K, Katahira J, Traber LD, Herndon DN, Schmalstieg FC, Traber DL, Hawkins HK. Airway obstruction in sheep with burn and smoke inhalation injuries. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29(3 Pt 1):295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearce ML, Yamashita J, Beazell J. Measurement of Pulmonary Edema. Circ Res. 1965;16:482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enkhbaatar P, Cox RA, Traber LD, Westphal M, Aimalohi E, Morita N, Prough DS, Herndon DN, Traber DL. Aerosolized anticoagulants ameliorate acute lung injury in sheep after exposure to burn and smoke inhalation. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(12):2805–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavrentieva A, Kontakiotis T, Bitzani M, Papaioannou-Gaki G, Parlapani A, Thomareis O, Tsotsolis N, Giala MA. Early coagulation disorders after severe burn injury: impact on mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(4):700–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofstra JJ, Vlaar AP, Cornet AD, Dixon B, Roelofs JJ, Choi G, van der Poll T, Levi M, Schultz MJ. Nebulized anticoagulants limit pulmonary coagulopathy, but not inflammation, in a model of experimental lung injury. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2010;23(2):105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murakami K, McGuire R, Cox RA, Jodoin JM, Bjertnaes LJ, Katahira J, Traber LD, Schmalstieg FC, Hawkins HK, Herndon DN, et al. Heparin nebulization attenuates acute lung injury in sepsis following smoke inhalation in sheep. Shock. 2002;18(3):236–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller AC, Rivero A, Ziad S, Smith DJ, Elamin EM. Influence of nebulized unfractionated heparin and N-acetylcysteine in acute lung injury after smoke inhalation injury. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30(2):249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murakami K, Enkhbaatar P, Shimoda K, Mizutani A, Cox RA, Schmalstieg FC, Jodoin JM, Hawkins HK, Traber LD, Traber DL. High-dose heparin fails to improve acute lung injury following smoke inhalation in sheep. Clin Sci (Lond). 2003;104(4):349–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olson ST, Bjork I, Sheffer R, Craig PA, Shore JD, Choay J. Role of the antithrombin-binding pentasaccharide in heparin acceleration of antithrombin-proteinase reactions. Resolution of the antithrombin conformational change contribution to heparin rate enhancement. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(18):12528–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Justus AC, Roussev R, Norcross JL, Faulk WP. Antithrombin binding by human umbilical vein endothelial cells: effects of exogenous heparin. Thromb Res. 1995;79(2):175–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woods A Syndecans: transmembrane modulators of adhesion and matrix assembly. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(8):935–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin CC, Shih CH, Yang YL, Bien MY, Lin CH, Yu MC, Sureshbabu M, Chen BC. Thrombin induces inducible nitric oxide synthase expression via the MAPK, MSK1, and NF-kappaB signaling pathways in alveolar macrophages. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;672(1–3):180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thors B, Halldorsson H, Thorgeirsson G. eNOS activation mediated by AMPK after stimulation of endothelial cells with histamine or thrombin is dependent on LKB1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813(2):322–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1. Detailed methods

This file provides detailed information about the intrumentation, mechanical ventilation, hemodynamic monitoring, western blots as well as laboratory and immunohistochemical analyses.

2. Additional data:

This file provides tables with additional data that were recorded or determined during the experiment, but were of minor relevance for the discussion.