Abstract

The use of π-conjugated polymers (CPs) in conductive hydrogels remains challenging due to the water-insoluble nature of most CPs. Conjugated polyelectrolytes (CPEs) are promising alternatives because they have tunable electronic properties and high water-solubility, but they are often difficult to synthesize and thus have not been widely adopted. Herein, we report the synthesis of an anionic poly(cyclopentadienylene vinylene) (aPCPV) from an insulating precursor under mild conditions and in high yield. Functionalized aPCPV is a highly water-soluble CPE that exhibits low cytotoxicity, and we found that doping hydrogels with aPCPV imparts conductivity. We also anticipate that this precursor synthetic strategy, due to its ease and high efficiency, will be widely used to create families of not-yet-explored π-conjugated vinylene polymers.

Keywords: ring-opening metathesis polymerization, conjugated polyelectrolytes, conducting polymers, conductive hydrogels, insulating precursor

Graphical Abstract

A novel class of π-conjugated polyelectrolyte is synthesized from an insulating hydrophobic precursor made via ring-opening metathesis polymerization. Anionic poly(cyclopentadienylene vinylene) can be made with a variety of side chains, is conductive, non-toxic, and can easily be formulated into conductive hydrogels due to its high water-solubility.

Introduction

Conductive hydrogels, water-rich networks capable of moving charge when subjected to an electric field, have significant potential for use in tissue engineering and bioelectronics. Conductive hydrogels have been used as therapeutic patches or cell scaffolds in cardiac,[1–7] neural,[8–10] and skeletomuscular applications.[11] They have also been used with electronic devices to improve the generation of ionic current and to bridge the mechanical mismatch between electronic devices and biological tissue.[12,13] Common conductive agents of conductive hydrogels include metals, carbon-based nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes, and conjugated polymers (CPs) such as polypyrrole[14–16] and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly (styrene sulfonate).[17–20] CPs are particularly attractive because the redox behavior of the material can be paired with electrolytes in solution to convert electric currents from electronic devices to ionic current for biological applications.[12]

Despite the potential of CPs in conductive hydrogels, most CPs are water-insoluble and thus require specialized fabrication techniques to incorporate them into hydrogels, including “in-gel” polymerizations and coatings,[16,21] advanced blending techniques such as dispersion or emulsification,[4,5,14,20–22] and ionic liquid exchange[19]. Despite the use of these fabrication techniques, some CPs still show limited biological integration, exhibit cytotoxicity, and induce post-implantation inflammation.[3] Additionally, due to the water-insoluble nature of most CPs, controlling conductivity without altering the mechanical properties of the gel remains an inherent challenge. Higher CP loading onto the hydrogel can increase conductivity but also impacts its hydrodynamic elasticity, affecting the survival and differentiation of encapsulated stem cells.[23,24]

Conjugated polyelectrolytes (CPEs), CPs with a high density of charged side chains, are water-soluble alternatives to hydrophobic CPs as conductive agents in conductive hydrogels.[25–27] However, the syntheses of CPEs add additional layers of complexity to the already difficult syntheses of CPs, such as solvent incompatibilities or additional deprotection steps. Additionally, commonly used aromatic monomers such as thiophenes often require high temperatures, long reaction times, and the use of air- and water-sensitive catalysts for cross-coupling chemistries. Some of these reaction conditions can be incompatible with peptides that are often incorporated in hydrogels to facilitate biological integration. Additionally, commonly used cross-coupling monomers, such as organostannanes, are toxic[28] and must be rigorously removed before medical use.[25,29] Some CPEs are cytotoxic due to high charge density,[27,30–32] but limited synthetic accessibility of CPEs prevent rapid iterations with a wide array of side chains to develop biocompatible CPE hydrogels. Thus, there remains a critical unmet need for the synthesis of a simple CPE that can be synthesized on large-scale and formulated into biocompatible CHs without the need for advanced fabrication techniques.

One strategy to produce CPs is to synthesize a nonaromatic precursor polymer that can be transformed into a CP or CPE in a single post-polymerization modification step. In this strategy, milder synthetic conditions can be used for monomer functionalization and polymerization due to the lack of monomer aromaticity, potentially allowing for the incorporation of pendant peptides as polymer side chains. Ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) is a particularly attractive polymerization method for the synthesis of these precursor polymers because it is a well-studied living polymerization with high functional group tolerance, and the residual backbone alkenes of ROMP-based polymers can participate in π-conjugation. However, some attempts to convert a ROMP precursor into a CP or CPE require extremely high temperatures (≥200 °C) or the use of acids that are incompatible with the incorporation of peptide or protein side chains.[33–39] Additionally, many of these polymers are insoluble post-heat treatment. More recent efforts have been made to use milder acidic[39] or basic conditions[40] or even mechanochemical activation.[41,42]

Herein we report an operationally simple synthetic route to anionic poly(cyclopentadienylene vinylene) (aPCPV) via a soluble, easily accessible, and modular polymeric precursor. We synthesized a halogenated polynorbornene precursor polymer and convert this polymer into a CPE under mild conditions and in high yield (Scheme 1). The resulting polymer is negatively charged due to the deprotonation of an acidic proton from the cyclopentadiene repeat unit generated in situ as well as the deprotonation of the acid groups generated from imide hydrolysis. aPCPV is highly water-soluble, displays visible light absorption up to 610 nm, is conductive, and exhibits low cytotoxicity. aPCPV is oxidized in water but can be reversed either electrochemically or chemically. Due to these properties, we believe aPCPV will be an extremely useful class of polymers for tissue engineering applications.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of insulating hydrophobic precursor poly(1) and its conversion into π-conjugated poly(2).

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of insulating precursor polymer and conversion to π-conjugated aPCPV.

We sought to synthesize a halogenated precursor polymer that could undergo dehydrohalogenation under basic conditions to yield the necessary alkenes for a π-conjugated polymer backbone. For our initial design, we hypothesized that a polymer with allylic bromines would undergo facile elimination. Thus, we synthesized an oxanorbornene monomer via a [4+2] cycloaddition with 2,5-dibromofuran as the diene. Unfortunately, we could not detect any polymerization of these oxanobornenes by 1H NMR spectroscopy. We then attempted to synthesize oxanorbornene monomers with halogens one carbon further away from the alkene with furan and dihalogenated dienophiles for the [4+2] cycloaddition. However, these monomers could not be isolated in high yield. Instead, we used cyclopentadiene, a more reactive diene and were able to synthesize a panel of dihalogenated norbornene monomers on gram scale using cyclopentadiene and dichloromaleimides. In this report, we focus on three side chains of varying hydrophobicity, M(1a-c).

We polymerized M(1a-c) using Grubbs 2nd generation catalyst. Complete conversion of all three norbornene monomers was observed within 90 min by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 1a) and the polymers were purified by precipitation. Polymers with target degree of polymerization (DP) 50 and DP 200 both exhibited aggregation in dimethylformamide and tetrahydrofuran at concentrations as low as 2.5 mg/mL (Figure S1). As such, the molecular weight of poly(1a-c) could not be determined by size exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure identification of poly(2c). a1H NMR of M(1c) in CDCl3 (top) and poly(1c) in acetone-d6 (bottom). bStructures and CP-MAS 13C NMR spectra of poly(1c) (left structure, top spectrum) and poly(2c) (right structure, bottom spectrum). cATR-FTIR spectra of poly(1c) (solid) and poly(2c) (dotted) zoomed in on the carbonyl region.

Poly(1a-c) were converted to their conjugated aromatic forms by the addition of base. We screened a variety of bases of varying steric bulk from tert-butoxide to sodium hydride in a variety of organic solvents. However, due to its high charge density, aPCPV exhibits limited solubility in these organic solvents. We found that slow addition of 0.1 M aqueous KOH into a solution of poly(1c) in DMSO resulted in complete conversion of poly(1c) to poly(2c) while keeping the polymer soluble during the reaction. Solution 1H NMR spectroscopy could not be used to monitor this reaction because both the reaction mixture and the purified polymer exhibited extreme line broadening (Figure S2). Therefore, we used solid state cross-polarization magic-angle spinning (CP-MAS) 13C NMR analysis to confirm the structure of the final purified polymer (Figure 1b). Three differences in the NMR spectra are consistent with conversion of poly(1c) to poly(2c). First, the NMR spectrum of poly(2c) shows the complete disappearance of the C3 signals at 53.8 ppm which arises from the C-Cl bond. Second, the spectrum of poly(2c) shows complete disappearance of alkyl signals which arises from C7 only in poly(1c). Third, the appearance of a new peak in the carbonyl region can be attributed to a new carboxylic acid that forms from imide hydrolysis.

We further corroborated the polymer structure by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. We observed loss of the prominent absorbance at 1714 cm−1, which corresponds to the poly(1c) imide. We also observed the appearance of new absorbances from 1500–1750 cm−1 (Figure 1c). The shift into lower wavenumbers is consistent with the formation of the carboxylate from imide hydrolysis, as well as the weakening of the C-O bond via favored anionic “enolates” resonance structures which are only possible in the conjugated form.

The use of a norbornene framework offered advantages over an oxanorbornene framework. In polynorbornene, the elimination of the two chlorides results in a new acidic proton in situ which can be deprotonated to create the cyclopentadiene anion repeat unit that can impart high water solubility without the need for water-solubilizing side chains. As expected, due to the anionic backbone and acid side chain, poly(2a-c) are readily soluble in water despite the hydrophobic side chains in poly(2a) and poly(2b). We dissolved poly(2c) in water and found the pH to be 4–4.5 with concentrations as low as 0.15 mg/mL, consistent with the low pKa of both the cyclopentadiene anion and the acid side chains. Poly(2a) also exhibits pH-dependent solubility: poly(2a) crashes out of solution upon acidification to pH 1 with 1 M HCl and redissolves upon addition of 1 M KOH to pH 14 (Figure S3).

Characterization of the optical, electronic, and redox behavior of poly(2).

In its fully reduced state, poly(2c) absorbs light up to 610 nm (Figure 2a), which corresponds to an optical band gap of 2.03 eV. The UV-Vis spectrum of poly(2c) shows 3 λmax values and irradiation of the polymer at each of its three λmax results in a unique fluorescence emission (Figure 2a).

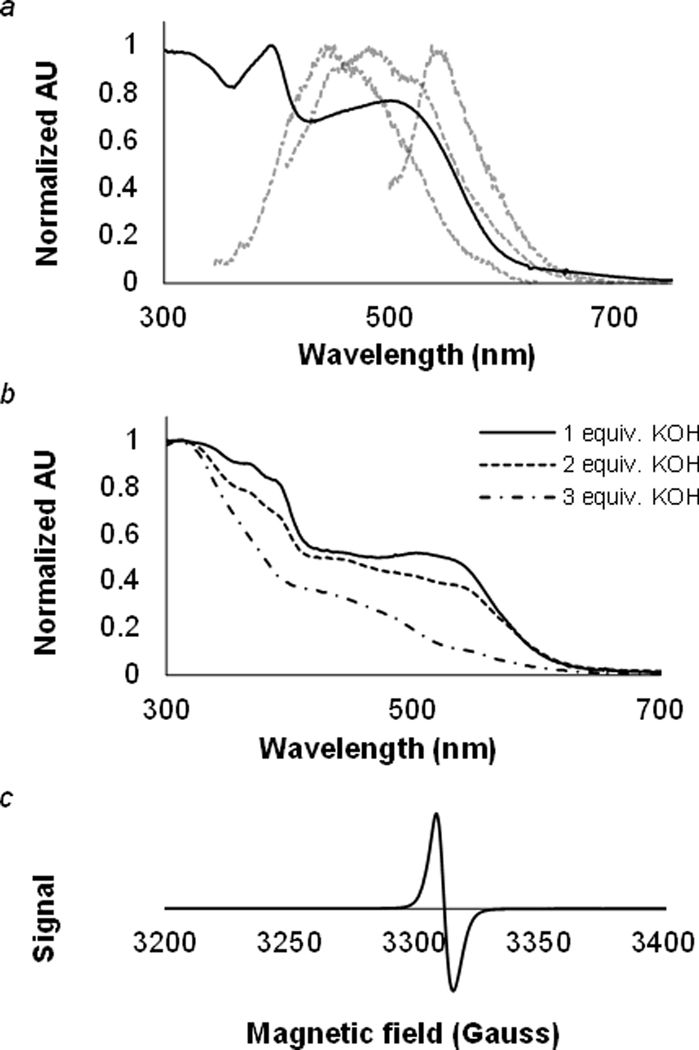

Figure 2.

Visible light spectroscopy of poly(2c) and its oxidation state. aUV-Vis absorbance (black) and fluorescence (grey) of poly(2c). λmax excitation/fluorescence pairs: 315/448 nm, 393/485 nm, 493/545 nm. bUV-Vis measurements of poly(2c) with 1, 2, or 3 equivalents of KOH supplied via a 0.1 M solution of KOH. cPowder ESR spectrum of poly(2c) shows the presence of an organic radical.

We attempted to monitor the conversion of poly(1c) to poly(2c) by UV-Vis spectroscopy because solution 1H NMR spectroscopy proved ineffective. Although 3 equivalents of KOH are needed per repeat unit for full aromatization to the cyclopentadiene anion, we noticed that addition of 1 equivalent of KOH resulted in UV-Vis absorption of the fully conjugated polymer. We also observed a loss of long wavelength absorption with addition of aqueous KOH (Figure 2b). We initially expected that as more KOH is added to the solution, poly(2c) would absorb more long-wavelength light, as more of the polymer becomes conjugated. The counterintuitive results can be explained in two parts. First, addition of 1 equivalent likely resulted in aromatization of 1/3 of the repeat units instead of elimination of one chloride from each repeat unit, and 1/3 of the polymer length exceeds the persistence length of the polymer. Elimination of one chloride from a repeat unit makes every proton on that repeat unit more acidic, resulting in accelerated aromatization. Second, the loss of long wavelength absorption is likely due to oxidation of aPCPV from water and dissolved oxygen.

We confirmed the presence of an organic radical, consistent with oxidation of the repeat unit from a (−1) state to a neutral radical, by electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy (Figure 2c). CP-MAS 13C NMR analysis corroborates oxidation of poly(2c). We originally expected there to be complete disappearance of signals in the δ = 30–50 ppm range due to the completely sp2 hybridized carbon backbone of poly(2c). We attribute the signals at δ = 30–50 ppm to oxidation of poly(2c) under experimental conditions, which would give rise to allylic signals from C1,2,3,7.

Cyclic voltammetry data are also consistent with the oxidized state of poly(2c). Poly(2c) exhibits electrochemical activity with reducing potential with the onset at −0.42 V vs. Ag/AgCl and a peak of −0.72 V vs. Ag/AgCl (Figure 3a).[43] However, no electrochemical oxidation current can be detected by cyclic voltammetry.

Figure 3.

aCV of poly(2c) at 5 mM with respect to monomer repeat unit in a solution of 100 mM KCl. CVs were taken at different scanning speeds. Background scan of 100 mM KCl with no polymer was taken at 100 mV/sec (grey). bStacked overlay of UV-Vis spectra of poly(2c) exposed to 100 equivalents of sodium ascorbate in 0.1 M KOH (top). Poly(2c) starting spectrum is a dotted. Bottom figure is a plot of the absorbance values at 393 nm (solid) and 493 nm (dotted).

We hypothesize that the lack of electrochemical oxidation of poly(2c) is due to its facile oxidation by water, given the significant overlap between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of poly(2c) and the lowest occupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of water. The energy level of the poly(2c) HOMO can be calculated using its reduction potential. Common n-type semiconductors become negatively charged because electron injection occurs at its LUMO; thus, the reduction potential is commonly used to determine the energy level of its LUMO. However, we believe poly(2) houses its negative charge in the aromatic cyclopentadiene anion HOMO, and that the reduction of poly(2c) at −0.72 V v. Ag/AgCl is due to an electron injection into the HOMO of poly(2c). A scan of 100 mM KCl solution without polymer shows that water is reduced at −0.75 V v. Ag/AgCl via electron injection into its LUMO. That the HOMO of poly(2c) coincides with the LUMO of water is consistent with our hypothesis that water can oxidize poly(2c).

Mechanistically, we envision that oxidation of poly(2c) results in cyclopentadiene radicals and that quickly terminate each other. But due to the resonance stabilization of the radicals, the termination is readily reversible. Two key pieces of experimental data are consistent with this. First, although we can detect the presence of an unpaired electron by ESR spectroscopy, extremely high concentrations (> 50 mg/mL) are needed to observe any signal. Although it is common to use low concentrations of organic radicals due to intermolecular quenching, poly(2) can quench itself intramolecularly and thus high concentrations only improves signal. The low concentration of radicals can be explained by the reversible radical-radical coupling between repeat units.

Second, poly(2) can be chemically reduced by sodium ascorbate under high pH conditions. Sodium ascorbate is known to be a proton-coupled electron transfer agent.[44] Poly(2c) was dissolved in 0.1 M KOH and 100 equivalents of sodium ascorbate were added. The reaction progress was monitored by following the absorption at λ = 393 nm and λ = 493 nm. Ascorbate quenches the radical on aPCPV and the bridgehead proton can be deprotonated again by hydroxide to regenerate the fully anionic polymer (Scheme 2). The absorbance at 393 nm initially spikes upon addition of ascorbate due to the absorption by ascorbate (Figure 3b). The absorbance at λ = 393 nm continues to increase due to the re-reduction of the polymer but the monotonic decrease after 15 seconds is likely due to the degradation of the sodium ascorbate. The reduction of the polymer can be more accurately monitored by the increase in the absorption λ = 493 nm which is unique to the polymer. However, 100 equivalents of sodium ascorbate are consumed within 105 minutes and the polymer starts to oxidize again, as seen by a reduction in decrease in 493 nm absorption at 120 minutes. The increased absorption at λ = 493 nm could not be achieved in PBS 7.4 buffer, suggesting that the strong reducing power of deprotonated ascorbate and subsequent deprotonation are essential to restore the polymer. We also explored the use of other common in-vivo reductants including reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, glutathione, and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine. However, the other reductants did not result in any changes to the UV-Vis absorption spectrum of poly(2c) (data not shown). That a strong proton-coupled electron transfer reducing agent could reduce the polymer is consistent with our hypotheses that poly(2c) oxidation results in radicals and that the termination processes are readily reversible.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism of poly(2) reduction by sodium ascorbate under high pH conditions.

The same reducing conditions were used to determine the effect of oxidation state on the molecular weight of poly(2c). Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) analysis of poly(2c) in water “as is” showed multimodal traces and was consistent with the presence of crosslinked high molecular weight species due to interpolymer radical-radical termination events. We hypothesized that reduction of poly(2c) by sodium ascorbate under high pH conditions would result in loss of crosslinks and formation of lower molecular weight species. Poly(2c) was treated with sodium ascorbate and hydroxide and analyzed by GPC after a 15-minute incubation. As expected, the polymer was reduced and the molecular weight of poly(2c) decreased (Figure S4). After an additional 30 minutes, another small aliquot was taken for GPC analysis. Poly(2c) again showed the formation of high molecular weight species, consistent with reformation of crosslinks between the cyclopentadienyl radical repeat units. Light scattering (LS) traces are shown instead of differential refractive index (dRI) traces because the dRI traces are dominated by the small molecule ascorbate signal and LS is more sensitive to the large molecular weight species.

Because poly(2c) is oxidized quickly by water, we sought alternative solvents to dissolve poly(2c). However, polar solvents such as acetonitrile, dioxane, dimethylformamide, dimethyl sulfoxide, and tetrahydrofuran could not fully dissolve poly(2c) without the addition of at least 5–10 vol% water. Thus, we decided to continue to use poly(2c) “as is.” We could not obtain a uniform film of poly(2c) for 4-point probe measurements and thus we dropcast poly(2c) onto FTO-coated glass substrates and determined current-voltage characteristic curves by a point scan in conductive AFM (Figure 4a).

Figure 4. Electrical behavior and cytotoxicity of poly(2c).

aIV curve determined by a conductive AFM on a dropcast film on FTO functionalized glass. bCytotoxicity assays of poly(2c) determined by AlamarBlue assay for NIH 3T3 fibroblasts in standard cell culture conditions and cell culture conditions doped with Matrigel (top). Cytotoxicity assays of poly(2a), poly(2b), and poly(2c) for primary neural progenitor cells in standard cell culture conditions (bottom).

Preparation of conductive hydrogels.

We returned to our original motivations for synthesizing a water-soluble conjugated polymer for the purposes of simplifying fabrication procedures for CHs. Because the reduced state of poly(2c) cannot be maintained in water, we used poly(2c) “as is.” The polymer was formulated into 2.5 wt% agarose hydrogels in water at a final concentration of 2.5 mg/mL polymer simply by pipette mixing a stock solution of poly(2c) with a stock solution of warm agarose gel. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate was used as a nonconjugated polyelectrolyte control. We measured the resistances of the hydrated and dehydrated gels 10 times for each sample with a 4-point probe (Table 1). The hydrated gels showed higher conductivities than the control conditions. Interestingly, the dehydrated gels doped with poly(2c) exhibited far less resistance at a high salt concentration which suggests that ion concentration may heavily influence the electrochemical behavior of aPCPV, a commonly observed phenomenon in CPs due to their ion-charge coupling and the basis of organic electrochemical transistors.[45]

Table 1.

Resistance values determined by 4-point probe of hydrated and dehydrated agarose hydrogels doped with different polymers.

| +150 mM HBSS | −150 mM HBSS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance (ohms) | Resistance (ohms) | ||

| Gel only | 101.56 | 1.56 * 104 | |

| Hydrated | Gel + PSS | 98.43 [a] | 0.487 * 104 [b] |

| Gel + poly(2c) | 91.87 [a] | 0.401 * 104 [b] | |

| Gel only | > 2 * 108 | > 2 * 108 | |

| Dehydrated | Gel + PSS | > 2 * 108 | > 2 * 108 |

| Gel + poly(2c) | 3.14 * 107 | > 2 * 108 | |

p < 0.001 by one-tail t-test

p < 0.005 by one-tail t-test.

Cytotoxicity assay for aPCPV.

The cytotoxicity of Poly(2c) was determined by AlamarBlue assay after incubating poly(2c) with NIH 3T3 fibroblasts at various concentrations for 12 hours. The IC50 of poly(2c) under normal cell culture conditions was 8.4 mg/mL and in 1:60 dilution of Matrigel was 7.3 mg/mL (Figure 4c, top). We hypothesize that the toxicity could be due to the extremely high salt concentration from the aPCPV. Cytotoxicity assays were repeated with poly2(a-c) on neural progenitor cells isolated from the forebrains of 8-week old mice. Poly(2c) exhibited high biocompatibility while poly(2a) and poly(2b) exhibited extreme cytotoxicity, likely due to interactions of the hydrophobic side chains with the cell membrane. (Figure 4c, bottom).

Conclusion

We report our initial efforts in the synthesis, characterization, and application of a new class of water-soluble conjugated polyelectrolyte. aPCPV displays UV-Vis absorption up to 610 nm, is conductive, and exhibits low cytotoxicity. Due to its high water-solubility, aPCPV can easily be mixed into hydrogel formulations without advanced fabrication techniques, and thus we believe that this new class of polymer will be readily adopted in the field of tissue engineering. Additionally, this insulating precursor approach can be used to synthesize families of not-yet-explored π-conjugated vinylene polymers from insulating precursor polymers made via ROMP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Robert F. Rushmer Professorship at the University of Washington and NIH 2R01NS064404.

DCL thanks Michael De Siena, Elizabeth R. Canarie, and Prof. Stefan Stoll for discussions about paramagnetism and help with electron spin resonance spectroscopy. DCL thanks Lucas Q. Flagg and Prof. David S. Ginger for discussions, training on spectroelectrochemistry, and conductive AFM data. DCL also thanks Adrienne Roehrich for help with CP-MAS 13C NMR and accommodating scheduling.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1].Zhou J, Chen J, Sun H, Qiu X, Mou Y, Liu Z, Zhao Y, Li X, Han Y, Duan C, et al. , Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Martins AM, Eng G, Caridade SG, Mano F, Reis RL, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Balint R, Cassidy NJ, Cartmell SH, Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2341–2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Borriello A, Guarino V, Schiavo L, Alvarez-Perez MA, Ambrosio L, J. Mater. Sci. Mater Med 2011, 22, 1053–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liu B, Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1783–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ronaldson-Bouchard K, Ma SP, Yeager K, Chen T, Song L, Sirabella D, Morikawa K, Teles D, Yazawa M, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Nature 2018, 556, 239–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yoshida S, Sumomozawa K, Nagamine K, Nishizawa M, Macromol. Biosci. 2019, 1900060, 1900060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Xu B, Bai T, Sinclair A, Wang W, Wu Q, Gao F, Jia H, Jiang S, Liu W, Mater. Today Chem. 2016, 1–2, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Koppes AN, Keating KW, McGregor AL, Koppes RA, Kearns KR, Ziemba AM, McKay CA, Zuidema JM, Rivet CJ, Gilbert RJ, et al. , Acta Biomater. 2016, 39, 34–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhou L, Fan L, Yi X, Zhou Z, Liu C, Fu R, Dai C, Wang Z, Chen X, Yu P, et al. , ACS Nano 2018, 12, 10957–10967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sirivisoot S, Pareta R, Harrison BS, Interface Focus 2014, 4, DOI 10.1098/rsfs.2013.0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yuk H, Lu B, Zhao X, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 1642–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Abidian MR, Martin DC, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 573–585. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Liu M, Xu N, Liu W, Xie Z, RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 84269–84275. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Collier JH, Camp JP, Hudson TW, Schmidt CE, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 50, 574–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mihic A, Cui Z, Wu J, Vlacic G, Miyagi Y, Li SH, Lu S, Sung HW, Weisel RD, Li RK, Circulation 2015, 132, 772–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lu B, Yuk H, Lin S, Jian N, Qu K, Xu J, Zhao X, Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, DOI 10.1038/s41467-019-09003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhu B, Luo SC, Zhao H, Lin HA, Sekine J, Nakao A, Chen C, Yamashita Y, Yu HH, Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Liu Y, Liu J, Chen S, Lei T, Kim Y, Niu S, Wang H, Wang X, Foudeh AM, Tok JBH, et al. , Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 3, 58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Feig VR, Tran H, Lee M, Bao Z, Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lee JY, Bashur CA, Goldstein AS, Schmidt CE, Biomaterials 2009, 30, 4325–4335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Han J, Wu Q, Xia Y, Wagner MB, Xu C, Stem Cell Res. 2016, 16, 740–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE, Cell 2006, 126, 677–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jeffords ME, Wu J, Shah M, Hong Y, Zhang G, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 11053–11061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhu C, Liu L, Yang Q, Lv F, Wang S, Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4687–4735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wang D, Gong X, Heeger PS, Rininsland F, Bazan GC, Heeger AJ, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 49–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu B, Bazan GC, Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 4467–4476. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lowe D, “A Farewell to Tin | In the Pipeline,” can be found under http://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2007/07/22/a_farewell_to_tin, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Das S, Chatterjee DP, Ghosh R, Nandi AK, RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 20160–20177. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mendez E, Moon JH, Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 6048–6050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lee J, Twomey M, Machado C, Gomez G, Doshi M, Gesquiere AJ, Moon JH, Macromol. Biosci. 2013, 13, 913–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fernando LP, Kandel PK, Yu J, Mcneill J, Christine P, a Christensen K, Biomacromolecules 2011, 11, 2675–2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bott DC, Brown CS, Chai CK, Walker NS, Feast WJ, S Foot PJ, Calvert PD, Billingham NC, Friend RH, Synth. Met. 1986, 14, 245–269. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Road C, Road S, Sciences M, Road M, Synth. Met. 1986, 14, 245–269. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Foot PJS, Calvert PD, Billingham NC, Brown CS, Walker NS, James DI, Polymer (Guildf). 1986, 27, 448–454. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fischer W, Stelzer F, Heller C, Leising G, Synth. Met. 1993, 55–57, 815–820. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Schimetta M, Stelzer F, Macromolecules 1994, 27, 3769–3772. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schimetta M, Leising G, Stelzer F, Synth. Met. 1995, 74, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Taylor MS, Swager TM, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8480–8483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Seo J, Lee SY, Bielawski CW, Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 6401–6412. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chen Z, Mercer JAM, Zhu X, Romaniuk JAH, Pfattner R, Cegelski L, Martinez TJ, Burns NZ, Xia Y, Science (80-. ). 2017, 357, 475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yang J, Horst M, Romaniuk JAH, Jin Z, Cegelski L, Xia Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6479–6483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Creutz C, Inorg. Chem. 1981, 20, 4449–4452. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Warren JJ, Tronic TA, Mayer JM, Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6961–7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Flagg LQ, Giridharagopal R, Guo J, Ginger DS, Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 5380–5389. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.