Abstract

Background:

Mailed fecal immunochemical test (FIT) outreach effectively increases colorectal cancer (CRC) screening but is underutilized. This pilot aimed to determine the use of FIT for CRC screening among Medicare Advantage enrollees when offered via mailed outreach and the factors associated with FIT return.

Methods:

Our pilot study included Medicare Advantage enrollees who were 50–75-years old, not up to date with CRC screening, and had a billable primary care encounter in the prior 3 years. Eligible patients received a letter containing information about CRC screening and a FIT kit, screening status by FIT was then assessed using the electronic health record.

Results:

Of the 1142 patients identified, 945 were eligible for outreach. On 12-month follow up, 29% of patients (n = 276) completed CRC screening via FIT, with a median return time of 140 days [interquartile range (IQR) 52–257]; 6% (n = 17) of the completed tests were positive, and 53% (n = 9) of patients have completed a diagnostic colonoscopy. Patients with primary encounter <12 months prior to mailed outreach were most likely to complete a FIT. Over the 12-month study period, CRC screening rates increased by 5% (63–68%).

Conclusions:

Mailed FIT outreach in a Medicare Advantage population was feasible and led to a 5% increase in CRC screening completion. Our pilot revealed rare incorrect patient addresses and high lab discard rate; both important factors that were addressed prior to larger-scale implementation of a mailed FIT program. Further research is needed to understand the potential impact of multilevel interventions on CRC screening in this healthcare system.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, fecal immunochemical test, Medicare Advantage

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is preventable but remains a leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States (US),1 largely due to underutilization of screening.2 An estimated 200,000 deaths could be prevented in the US over the next 20 years if 80% of eligible adults were screened,3 yet among adults ages 50–75, 70% report being up to date with CRC screening.4 While colonoscopy remains the primary modality for CRC screening in the US,5 there is increased uptake of fecal immunochemical test (FIT) in large integrated health systems6 and in resource-constrained settings such as safety-net populations, who also may have a preference7 for non-invasive screening modalities.

FIT is a yearly, stool-based, CRC screening test that can be completed at home, returned by mail, and is inexpensive and scalable across large populations.8 When compared with the traditional 3-sample fecal occult blood test (FOBT), FIT has superior test performance characteristics9 and adherence.10 For these reasons, FIT-based outreach programs have proven to be an effective means of increasing CRC screening in low-income11–14 as well as insured populations.6,15 Our recent systematic review revealed that mailed FIT outreach consistently improved CRC screening completion, but the magnitude of impact varied across patient populations and healthcare settings.16

In 2018, over 20 million people—representing 34% of all Medicare beneficiaries—were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans.17 Medicare Advantage plans are incentivized by publicly reported annual star ratings that consumers can use when selecting plans. Preventive services, including CRC screening, are included in the measures used to calculate star ratings. In July 2017, 63% of Medicare Advantage enrollees in our healthcare system were up to date with CRC screening, below the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable goal of 80%.18 As such we sought to determine the impact of a mailed FIT outreach program in a Medicare Advantage population within a predominantly colonoscopy-based CRC screening program. Our pilot was designed to inform increased utilization of mailed FIT outreach as part of a multilevel intervention to improve system-wide CRC screening rates.

Methods

Study setting

We performed a prospective pilot study in an urban academic-community practice, the University of Washington (UW) Medicine. UW Medicine is a comprehensive, integrated health system in the Pacific Northwest that includes five clinic networks and 39 primary care clinics, including 7 safety-net clinics. These clinics are integrated with a single electronic health record (EHR) system and share a centralized clinical laboratory for FIT processing.

The study observed the clinical implementation of a system-wide quality improvement project to increase uptake of several screening examinations, of which colorectal cancer screening was one. Because colorectal cancer screening within this population is recommended by U.S. medical societies and a quality metric for the payer plan, our study was deemed a quality improvement effort, not human subjects research, and did not require Institutional Review Board approval according to institutional regulations.

Individual informed consent was not required for this study because it was considered not human subjects research.

Study population

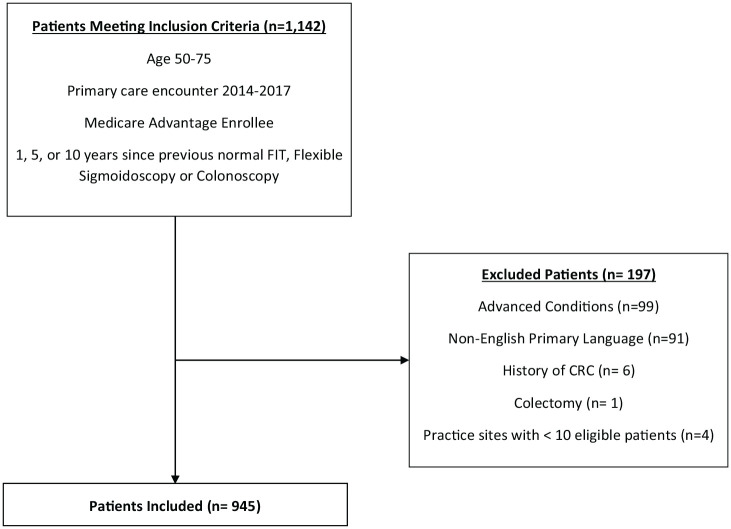

Patients age 50–75 who were Medicare Advantage enrollees, not up to date with CRC screening and with a billable primary care encounter in the prior 3 years were eligible. Primary care encounters included primary care clinic visits, laboratory testing, radiologic imaging, telemedicine, home visits, and other EHR encounters linked to the patient’s primary care practice for billing purposes. Previously screened patients were eligible for outreach 1 year after previous negative FIT, 5 years after previous normal sigmoidoscopy, and 10 years after previous normal colonoscopy. Patients were excluded if they were enrolled in non-Medicare Advantage health plans, were primary non-English speakers, belonged to a practice site with less than 10 patients eligible for CRC screening, had a history of CRC, colectomy, or advanced comorbidities (inflammatory bowel diseases, advanced cardiopulmonary diseases and metastatic cancer; Figure 1). The baseline CRC screening rate among Medicare Advantage enrollees in our health system at the beginning of the pilot was 63%, consistent with data from the National Health Interview Survey that found 69% of patients with Medicare were up to date with CRC screening.19

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included and excluded patients.

CRC, colorectal cancer.

Study intervention

Outreach included a letter with basic information about CRC and the rationale for CRC screening signed by the Division Head of Gastroenterology, a FIT kit, and a prepaid return envelope. Patients who did not return their FIT kit within 2 weeks of the initial mailing, received up to two bi-weekly reminders. Reminders included a postcard, a patient phone call, a patient electronic portal message or a combination depending on patient response, staffing and available resources. In rare instances, when patients were found to have an upcoming appointment through chart review, providers were sent electronic messages to encourage patients to complete FIT kits during the visit. Written materials for this pilot were only provided in English. The FIT brand used in the health system was OC-Auto FIT (Polymedco CDP, LLC, Cortlandt Manor, NY, US) and a positive result was reported when there was >100 ng/ml of hemoglobin detected or >20 µg hemoglobin/gram of stool.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome of FIT screening status was determined by laboratory test completion and results populated into the EHR, which has been previously validated.20,21 Secondarily, we assessed factors associated with FIT completion and extracted endoscopy and pathology results to determine post-screening clinical outcomes. Pathology reports were reviewed for the following: cancer; advanced adenoma; advanced neoplasia; and non-advanced adenoma. The procedure for reporting pathologic findings has been previously described.22 Briefly, advanced adenomas are polyps (sessile serrated lesions or tubular adenomas) ⩾10 mm or any size polyp with villous features or high-grade dysplasia. Advanced neoplasia are cancers or advanced adenomas, while non-advanced adenomas are polyps (sessile serrated lesions or tubular adenomas) <10 mm.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographic information was described as proportions or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Days from mailed to completed FIT and abnormal FIT to endoscopy completion were described using medians and IQR. Differences between groups were assessed using chi-square and student’s t-test, as appropriate. Multivariable analysis was performed to determine the factors associated with completion of mailed FIT kit, adjusting for age, sex, race, ethnicity, last primary care encounter and primary care clinic network. Accompanying odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence interval (CI), and p values were reported in all instances and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used Stata/SE (version 16.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, US) statistical software for all analyses.

Results

Of the 1142 patients identified based on age and CRC screening eligibility, 945 met criteria for outreach based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. The median age was 68 years, 54% (n = 509) were female, 73% White, 10% Black, 6% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 1% American Indian/Alaskan Native; 2% were Hispanic and 81% (n = 767) had a primary care clinic encounter in the prior 12 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients who received mailed FIT outreach.

| Overall (n = 945) | FIT completed (n = 276) | FIT not completed (n = 669) | aOR* | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median | 68 | 68 | 68 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 | 0.537 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 436 (46%) | 115 | 321 | − | − | − |

| Female | 509 (54%) | 161 | 348 | 1.27 | 0.94–1.71 | 0.112 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 691 (73%) | 211 | 480 | − | − | − |

| Black | 98 (10%) | 22 | 76 | 0.69 | 0.39–1.23 | 0.212 |

| Asian | 58 (6%) | 21 | 37 | 1.40 | 0.78–2.49 | 0.256 |

| Other | 22 (2%) | 6 | 16 | 0.78 | 0.29–2.06 | 0.611 |

| Unknown | 76 (8%) | 16 | 60 | 1.04 | 0.46–2.37 | 0.925 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 832 (88%) | 250 | 582 | − | − | − |

| Hispanic | 15 (2%) | 4 | 11 | 0.69 | 0.21–2.26 | 0.544 |

| Unknown | 98 (10%) | 22 | 76 | 0.90 | 0.45–1.81 | 0.769 |

| Last primary care encounter | ||||||

| No encounter | 63 (7%) | 6 | 57 | − | − | − |

| <12 months | 764 (80%) | 254 | 510 | 4.74 | 1.91–11.79 | 0.001 |

| 13–24 months | 71 (8%) | 11 | 60 | 1.82 | 0.60–5.48 | 0.287 |

| 25–36 months | 47 (5%) | 5 | 42 | 1.13 | 0.31–4.13 | 0.857 |

| Primary care clinic | ||||||

| Clinic network A | 509 (54%) | 155 | 354 | − | − | − |

| Clinic network B | 162 (17%) | 43 | 119 | 0.98 | 0.62–1.57 | 0.947 |

| Clinic network C | 209 (22%) | 62 | 147 | 0.89 | 0.62–1.28 | 0.529 |

| Clinic network D | 65 (7%) | 16 | 49 | 0.82 | 0.44–1.51 | 0.520 |

Characteristics of patients who received mailed FIT outreach and multivariable logistic regression of characteristics associated with mailed FIT completion.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, last primary care encounter and assigned primary care clinic.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; FIT, fecal immunochemical test.

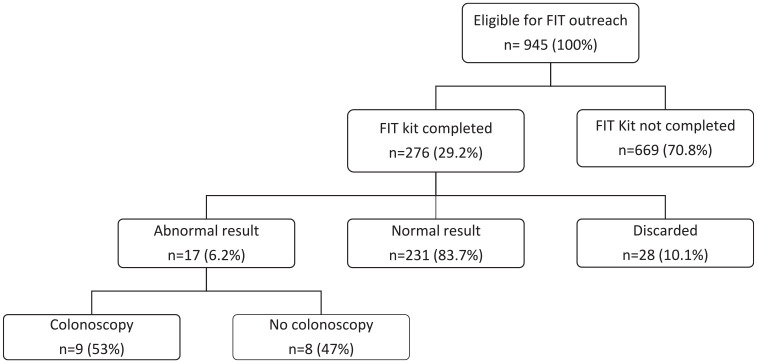

On 12-month follow up, 29% of patients (n = 276) had returned their FIT; 84% (n = 231) were negative, 10% (n = 28) were discarded by the lab due to illegible patient writing on labels, and 6% (n = 17) were positive (Figure 2). The median time from mailed to returned FIT kit was 140 days (IQR 52–257). Of the 276 patients who returned their FIT kit, 117 returned the FIT kit without any reminders; 86 received a postcard only, 27 received a postcard and phone call, 23 received a postcard and patient portal message, 9 received only a phone call, and 14 received only a reminder to their PCP’s office before a scheduled appointment. In total, reminders led to an additional 159 FIT kits returned. Considering all patients that received reminders, 28% (109/400) completed a FIT after one reminder and 13% (50/392) after two reminders. Incorrect patient addresses leading to undelivered FIT kits were rare (n = 1).

Figure 2.

Outcome of mailed FIT outreach.

FIT, fecal immunochemical test.

Compared with patients without a primary care encounter prior to mailed outreach, patients with an encounter within the previous 12 months were more likely to return the FIT (33% versus 10%, OR 4.73, 95% CI 2.01–11.12, p < 0.001). There was also a trend toward FIT completion among patients with a primary care encounter 13–24 months prior to outreach (15% versus 10%, OR 1.74, 95% CI 0.60–5.02, p = 0.304), but this did not reach statistical significance. FIT return by assigned clinic network ranged from 25% to 30%; however, these differences were not statistically significant (Table 1). Overall, women were more likely than men to return a mailed FIT kit (32% versus 26%, OR 1.29, CI 0.97–1.71, p = 0.077) and Asian patients had the highest proportion of returned FIT compared with all other races (36% versus 22–31%); neither of these differences were statistically significant.

Our multivariable logistic model adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, last primary care encounter, and assigned primary care clinic network. In this model, a primary care encounter <12 months prior to mailed outreach continued to remain positively associated with FIT completion (OR 4.74, 95% CI 1.91–11.79, p < 0.01). Other factors (age, sex, race, ethnicity, and clinic network) did not impact FIT completion (Table 1). In a pre-post-intervention analysis, CRC screening rates among Medicare Advantage enrollees increased by 5% (63–68%) between July 2017 and June 2018.

Within 12 months of an abnormal FIT result, 53% (9/17) of patients completed a diagnostic colonoscopy. The median time from abnormal FIT result to colonoscopy completion was 42 days (IQR 34–73). While no patients in this cohort were diagnosed with CRC, 22% (2/9) had advanced neoplasia and 44% (4/9) had non-advanced adenomas. Among patients who completed a colonoscopy, the bowel preparation was adequate during the first colonoscopic examination in 78% (Table 2). Of the patients with an abnormal result that did not complete a colonoscopy within 12 months, EHRs revealed the majority were delayed due to other competing health priorities (7/8), and one patient died due to an unrelated cause.

Table 2.

Summary of colonoscopy findings among patients with abnormal FIT results.

| Patient | Sex | Days to colonoscopy | Pathology finding | Bowel preparation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | F | 73 | NAA | n/a |

| 02 | F | 71 | − | Adequate |

| 03 | M | 108 | NAA | Inadequate |

| 04 | F | 34 | AA/AN | Adequate |

| 05 | F | 27 | − | Adequate |

| 06 | F | 42 | NAA | Adequate |

| 07 | M | 37 | AA/AN | Adequate |

| 08 | M | 27 | NAA | Adequate |

| 09 | F | 182 | Hyperplastic | Adequate |

Endoscopic findings for patients with abnormal FIT results.

AA, advanced adenoma; AN, advanced neoplasia; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; n/a, not available; NAA, non-advanced adenoma.

Discussion

In this prospective pilot of Medicare Advantage enrollees, 29% of patients who were previously not up to date with CRC screening, returned a FIT received through mailed outreach. An estimated three to four individuals needed to receive mailed outreach to increase CRC screening participation by one patient. Our prior research demonstrated that the cost to perform outreach for one individual was $23 and the cost per additional patient screened was $112; both acceptable costs on face value given the established benefit of CRC screening.23

The proportion of individuals who returned a FIT after mailed outreach in our pilot was on the higher end of previously reported studies.16,24,25 This finding is likely due to our cohort of well-insured individuals compared with studies focused on Medicaid enrollees and populations receiving care through federally qualified healthcare centers (FQHCs). In addition, our primary end point evaluated FIT completion after 12 months, while other similar studies have reported more variable follow-up times (3 months to 24 months). Consistent with studies that have evaluated the impact of primary care encounters on being up to date with screening practices,26 we found that patients with a primary care encounter in the past 12 months were more likely to complete FIT than those without primary care contact during that same time period, suggesting that mailed FIT may be more effective among patients who have more recently engaged with the healthcare system. In addition, our study revealed that while reminders increased overall FIT completion, the incremental benefit declined with each additional reminder. This suggests that there are a proportion of patients, who are unlikely to complete a mailed FIT despite outreach and follow-up efforts. A recent Centers for Disease Control summit on mailed FIT outreach (unpublished data) recommends implementation of at least one type of reminder after mailed FIT, acknowledging that additional research is needed on how to operationalize reminders.

Our pilot revealed rare incorrect patient addresses. The accuracy of patient addresses should be evaluated prior to the initiation of any mailed FIT outreach program to ensure patient receipt and to limit wasted resources. Although not completed within this pilot, programs can consider mailing postcards prior to FIT outreach; postcard return rates could provide insight into the accuracy of patients’ home addresses ahead of broader outreach. Our pilot also revealed a relatively high (10%) rate of discarded FIT kits due to illegible patient writing on labels. A smaller roll-out of our mailed FIT program allowed us to identify these issues and develop solutions with the clinical laboratory such as pre-printed patient labels prior to a larger mailed outreach initiative. The larger initiative aims to include a broader patient population including non-English speakers.

A critical component of any mailed FIT outreach is the completion of a diagnostic colonoscopy after an abnormal result. Diagnostic colonoscopy completion rates in our study were comparable with other studies. Patients who have yet to complete a diagnostic colonoscopy, declined due to other competing health interests. While no cases of CRC were found within our cohort, the reported cancer prevalence in cohort studies of patients with abnormal FIT results ranges from 3.4% to 6.1%,27,28 making incomplete follow up an important problem. Surprisingly, evidence-based interventions that improve diagnostic colonoscopy completion are sparse. Given the need for coordination across multiple teams in the process of care (e.g. communication and coordination between primary and specialty care), such interventions will likely need to target multiple levels across the CRC screening continuum.

The continued growth of Medicare Advantage enrollees and the incentive structure of existing plans provides a unique opportunity to improve US CRC screening rates through mailed FIT outreach. Research shows a higher diagnostic yield of advanced neoplasia among participants who completed four rounds of yearly FIT for CRC screening compared with one-time colonoscopy or one-time flexible sigmoidoscopy with no difference in the detection of CRC across these strategies.29 While colonoscopy remains the primary modality for CRC screening in the US, some countries have achieved high CRC screening rates through organized fecal testing, including by FIT.30–32 Furthermore, providing colonoscopies to all eligible US citizens may not be feasible due to limitations of costs or the endoscopy labor force. In order to achieve population-wide improvements in CRC screening, interventions such as increased utilization of mailed outreach will be required, considering infrastructural factors and implementation strategies that will promote high-quality screening programs.

Our study has limitations. First, out-of-network utilization of CRC screening services may have occurred but is likely limited given our study time period and a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria. Second, patients with advanced comorbidities were excluded. Although this is standard practice in screening studies, it is possible that individuals with advanced comorbidities, who are less likely to complete screening would have lowered overall participation. Third, while the risk of CRC in the general population is 5%, given the lack of cancer diagnoses within our pilot, it is possible that those who might have been diagnosed with CRC did not participate in screening and are thus not represented in this analysis. Efforts to engage the eligible adults in CRC screening are ongoing within our institution and nationally. Finally, diagnostic colonoscopy is necessary after an abnormal FIT result to reduce CRC mortality, but our pilot intervention did not address diagnostic colonoscopy completion. Despite these limitations, mailed outreach remains cost effective even with suboptimal follow-up colonoscopy rates.23

In conclusion, 29% of Medicare Advantage enrollees who were not up to date with CRC screening completed FIT through mailed outreach; thus, this intervention is feasible and effective in this patient population and should be considered as part of other system-level strategies to improve overall CRC screening participation.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Study concept and design: Issaka, Akinsoto, Chaudhari, Flum, Inadomi. Acquisition of data: Issaka, Akinsoto. Statistical analysis: Issaka. Drafting of the manuscript: Issaka. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Approval of the final manuscript: all authors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Issaka receives funding from National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, award number K08 CA241296. The project described was supported by Funding Opportunity Number CMS-331-44-501 from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. This funding was part of the Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative, authorized under and Social Security Act 1115(A) and in support of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) to strengthen the quality of patient care and spend healthcare dollars more wisely. The project described was 100% financed with federal money. The contents provided are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the US Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies.

ORCID iD: Rachel B. Issaka  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9691-1655

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9691-1655

Contributor Information

Rachel B. Issaka, 1100 Fairview Ave. N., M/S: M3-B232, Seattle, WA 98109, USA; Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA; Hutchinson Institute for Cancer Outcomes Research, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA; Division of Gastroenterology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA.

Nkem O. Akinsoto, Primary Care and Population Health, Chief Health System Office, University of Washington Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA

Erica Strait, Primary Care and Population Health, Chief Health System Office, University of Washington Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA.

Van Chaudhari, Primary Care and Population Health, Chief Health System Office, University of Washington Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA; Department of Health Services, School of Public Health, University of Washington. Seattle, WA.

David R. Flum, Primary Care and Population Health, Chief Health System Office, University of Washington Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA Division of General Surgery, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA.

John M. Inadomi, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68: 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cyhaniuk A, Coombes ME. Longitudinal adherence to colorectal cancer screening guidelines. Am J Manag Care 2016; 22: 105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meester RG, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, et al. Public health impact of achieving 80% colorectal cancer screening rates in the United States by 2018. Cancer 2015; 121: 2281–2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. BRFSS prevalence & trends data. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Population Health, https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/ (2015, accessed 3 February 2020).

- 5. Centers for Disease Control. Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening test use—United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62: 881–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levin TR, Jamieson L, Burley DA, et al. Organized colorectal cancer screening in integrated health care systems. Epidemiol Rev 2011; 33: 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172: 575–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doubeni CA. Precision screening for colorectal cancer: promise and challenges. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163: 390–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, et al. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160: 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hassan C, Rossi PG, Camilloni L, et al. Meta-analysis: adherence to colorectal cancer screening and the detection rate for advanced neoplasia, according to the type of screening test. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 36: 929–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baker DW, Brown T, Buchanan DR, et al. Comparative effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve adherence to annual colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174: 1235–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldman SN, Liss DT, Brown T, et al. Comparative effectiveness of multifaceted outreach to initiate colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30: 1178–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gupta S, Halm EA, Rockey DC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of fecal immunochemical test outreach, colonoscopy outreach, and usual care for boosting colorectal cancer screening among the underserved: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 1725–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Singal AG, Gupta S, Tiro JA, et al. Outreach invitations for FIT and colonoscopy improve colorectal cancer screening rates: a randomized controlled trial in a safety-net health system. Cancer 2016; 122: 456–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Green BB, Wang CY, Anderson ML, et al. An automated intervention with stepped increases in support to increase uptake of colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158: 301–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Issaka RB, Avila P, Whitaker E, et al. Population health interventions to improve colorectal cancer screening by fecal immunochemical tests: a systematic review. Prev Med 2019; 118: 113–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jacobson G, Damico A, Neuman T. A dozen facts about medicare advantage. Kaiser Family Foundation; https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/a-dozen-facts-about-medicare-advantage-in-2020/ (2020, accessed 1 March 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 18. The National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable, 80% In Every Community Strategic Plan – Draft, https://nccrt.org/about/how-we-work/strategic-plan/80-in-every-community-strategic-plan (2020, accessed 1 March 2020).

- 19. De Moor JS, Cohen RA, Shapiro JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening in the United States: trends from 2008 to 2015 and variation by health insurance coverage. Prev Med 2018; 112: 199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Devine EB, Capurro D, van Eaton E, et al. Preparing electronic clinical data for quality improvement and comparative effectiveness research: the SCOAP CERTAIN automation and validation project. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2013; 1: 1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Eaton EG, Devlin AB, Devine EB, et al. Achieving and sustaining automated health data linkages for learning systems: barriers and solutions. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2014; 2: 1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alsayid M, Singh MH, Issaka R, et al. Yield of colonoscopy after a positive result from a fecal immunochemical test OC-light. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Epub ahead of print 13 April 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Somsouk M, Rachocki C, Mannalithara A, et al. Effectiveness and cost of organized outreach for colorectal cancer screening: a randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2020; 112: 305–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brenner AT, Rhode J, Yang JY, et al. Comparative effectiveness of mailed reminders with and without fecal immunochemical tests for Medicaid beneficiaries at a large county health department: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2018; 124: 3346–3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coronado GD, Petrik AF, Vollmer WM, et al. Effectiveness of a mailed colorectal cancer screening outreach program in community health clinics: the STOP CRC cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178: 1174–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martin J, Halm EA, Tiro JA, et al. Reasons for lack of diagnostic colonoscopy after positive result on fecal immunochemical test in a safety-net health system. Am J Med 2017; 130: 93.e91–93.e97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jensen CD, Corley DA, Quinn VP, et al. Fecal immunochemical test program performance over 4 rounds of annual screening: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. Epub ahead of print 26 January 2016. DOI: 10.7326/M15-0983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chiu HM, Lee YC, Tu CH, et al. Association between early stage colon neoplasms and false-negative results from the fecal immunochemical test. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11: 832–838.e831–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grobbee EJ, Van der Vlugt M, Van Vuuren AJ, et al. Diagnostic yield of one-time colonoscopy vs one-time flexible sigmoidoscopy vs multiple rounds of mailed fecal immunohistochemical tests in colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Epub ahead of print 13 August 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heijnen ML, Landsdorp-Vogelaar I. CRC screening in the Netherlands. From pilot to National Programme, http://www.rivm.nl/en/Topics/B/Bowel_cancer_screening_programme (2014, accessed 3 February 2020).

- 31. Viguier J, Morere JF, Brignoli-Guibaudet L, et al. Colon cancer screening programs: impact of an organized screening strategy assessed by the EDIFICE surveys. Curr Oncol Rep 2018; 20: 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Decker KM, Demers AA, Nugent Z, et al. Longitudinal rates of colon cancer screening use in Winnipeg, Canada: the experience of a universal health-care system with an organized colon screening program. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110: 1640–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]