Abstract

Since the discovery of the GABAB agonist and muscle relaxant, baclofen, there have been substantial advancements in the development of compounds that activate the GABAB receptor as agonists or positive allosteric modulators. For the agonists, most of the existing structure–activity data applies to understanding the role of substituents on the backbone of GABA as well as replacing the carboxylic acid and amine groups. In the cases of the positive allosteric modulators, the allosteric binding site(s) and structure–activity relationships are less well defined; however, multiple classes of molecules have been discovered. The recent report of the X-ray structure of the GABAB receptor with bound agonists and antagonists provides new insights for the development of compounds that bind the orthosteric site of this receptor. From a therapeutic perspective, these data have enabled efforts in drug discovery in areas of addiction-related behavior, the treatment of anxiety, and the control of muscle contractility.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In the central nervous system, the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter is γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Its major roles are to regulate the release of other neurotransmitters and the excitation of neurons. These actions are modulated by three types of receptors: GABAA, GABAB, and GABAAρ (also known as GABAC). These three receptors have served as a rich source of targets for the pharmaceutical industry and many drugs have been developed as ligands for these sites.1 The ionotropic GABAA receptor, a ligand-gated chloride-ion channel that suppresses neuronal excitability, is the most extensively targeted receptor. GABAA receptors are pentamers assembled around a central pore, and sixteen distinct subunits have been identified (six α, three β, three γ, δ, ε, θ, and π).2 Typically, GABAA receptors consist of two identical α subunits, two identical β subunits, and one “other” subunit. The differential subunit assembly may give rise to considerable diversity in channel composition. Three major classes of pharmaceuticals, the barbiturates (e.g., phenobarbital), the benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam), and the nonbenzodiazepine sedative/hypnotics (e.g., zaleplon and zolpidem), are ligands that bind to the GABAA receptor.1, 3 The GABAAρ receptors are also chloride-ion channels that are homo-pentameric assemblies of ρ1–3, and perhaps, other subunits.2 Though they are ionotropic receptors, they have a distinct pharmacology from GABAA receptors, being resistant to both the GABAA antagonist bicuculline and the sedative/hypnotic drugs that target the GABAA receptors.4, 5 Currently, no pharmaceuticals target the GABAAρ receptor as a primary mechanism of action.1, 6

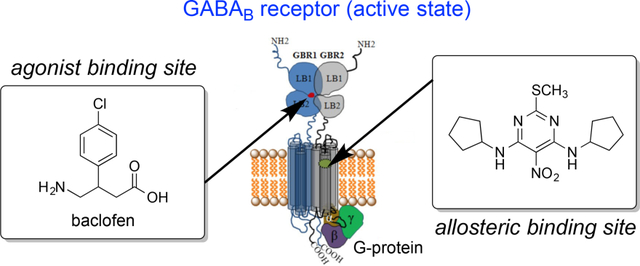

The GABAB receptor is an unusual G-protein coupled (i.e., metabotropic) receptor in that it exists as a heterodimer of GABAB1 and GABAB2 subunits.7 These receptors can inhibit the release of many neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine, via a G-protein-dependent inhibition of neuronal voltage-gated Ca2+ channels.8 However, activation of GABAB receptors also reduces neuronal excitability via activation of G-protein regulated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK or Kir3) channels.8 Finally, GABAB receptors regulate intracellular signaling by inhibiting adenylyl cyclase activity.9 GABAB receptors have an important function in the neuronal pathophysiology of many CNS diseases and disorders including anxiety, depression, epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, stroke, drug addiction, and the neurodegenerative disorders: Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease.10, 11 These receptors also have an established role in muscle spasticity disorders,12 pain,13 gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD),14 and schizophrenia.15 In contrast to the highly targeted GABAA receptor, currently the only FDA-approved drug to target the GABAB receptor is baclofen, a muscle relaxant. Specifically, baclofen is indicated for the relief of muscle spasticity in patients with multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injuries; however, baclofen is used off-label to treat many other conditions. One such off-label use is in the treatment of GERD14 and other peripherally acting GABAB agonists are under evaluation for the treatment of GERD.16, 17 GABAB agonists, including baclofen,10 and GABAB positive allosteric modulators18 have shown promise in numerous studies investigating their ability to prevent relapse in the treatment of drug and alcohol addiction,19, 20 as well as in the treatment of other neurological disorders.21, 22 In addition, the combination of baclofen and acamprosate was recently shown to be neuroprotective in a rodent model of Alzheimer’s disease.23

Despite its FDA approval for the treatment of muscle spasticity and a growing number of off-label and potential uses, baclofen is far from an ideal drug molecule. Baclofen has low penetration into the brain,24 a property which may be ascribed to transport out of the brain via the organic acid transporter.25 Additionally, baclofen has a short duration of action, a narrow therapeutic window, and a rapid tolerance.26 One notable advance is the investigational compound, arbaclofen placarbil, which serves as a prodrug of (R)-baclofen and was developed to enhance oral absorption compared to the parent compound.26 Although baclofen can be administered intrathecally via an implanted pump to reduce the doses required to achieve relief of muscle spasms and reduce peripheral side effects, additional innovations are needed. Thus, development of GABAB agonists or positive allosteric modulators with excellent brain/CNS penetration would provide a substantial improvement over baclofen in many therapeutic applications.

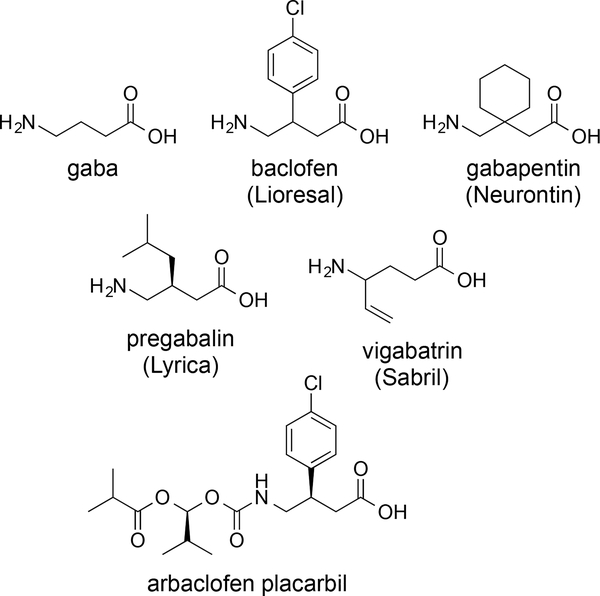

The extensive drug development efforts on the neurotransmitter, GABA, and the GABA receptors have provided many analogues of GABA. Correspondingly, the structure of GABA is embedded in the pharmaceuticals, baclofen, gabapentin, pregabalin, and vigabatrin (Figure 1). Although they display highly similar structures, the targets of these drugs are quite varied and some do not act on the GABA pathways.1 Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant, and despite its structural resemblance to GABA, gabapentin does not bind GABA receptors or influence the production or uptake of GABA.27 Pregabalin, which is used as an analgesic for neuropathic pain and as an anticonvulsant, also does not bind to GABA receptors or affect concentrations of GABA in the brain. Vigabatrin is an anticonvulsant and its mechanism of action is the inhibition of GABA transaminase, an enzyme responsible for the degradation of GABA.28 These agents further demonstrate the tremendous value in understanding the structure and the function of GABA and its receptors. The recent report in 2013 of the X-ray structure of the GABAB receptor, along with co-crystallized agonists and antagonists, provides a major breakthrough in this area, and a great foundation for the protein structure-based drug design of new modulators of this type of receptor.29 This perspective will serve as a guide of the existing structure-activity data for the activation of the GABAB receptor. The most significant and current potential for activation of the GABAB receptor is in the areas of alcoholism and drug abuse, and for example, three reviews focused on the preclinical and clinical studies in these therapeutic areas have appeared in the literature in 2014.18, 30, 31

Figure 1.

Structure of GABA and pharmaceuticals based on the structure of GABA.

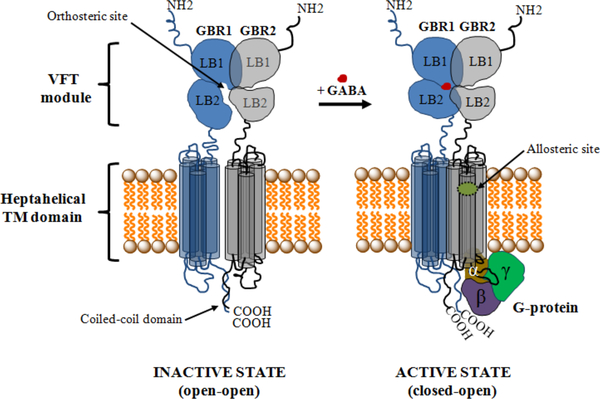

The GABAB receptor mediates slow and prolonged synaptic inhibition through Gi or Go proteins, and malfunctions of the GABAB receptor can be associated with various kinds of neurological disorders, including spasticity and epilepsy.29, 32–34 The functional unit of the GABAB receptor is a heterodimeric assembly of the two subunits GBR1b (GABAB1) and GBR2 (GABAB2)9, 35–37 containing 844 and 941 amino acids, respectively.38 Figure 2 depicts the complete GABAB receptor system, including its active and inactive (or resting) states. The extracellular Venus flytrap (VFT) domain (also called ectodomain) of the GBR1b subunit contains the recognition site for orthosteric ligands (agonists and competitive antagonists),29, 39–41 and no ligand binding occurs in the GBR2 subunit29, 40, 41 (Figure 2). The ectodomain of GBR2 directly interacts with the GBR1b ectodomain to enhance agonist affinity and is required for the normal trafficking of the GBR1b to the cell surface as well as for G-protein activation, via coupling with its heptahelical transmembrane domain.37, 42, 43 There is no X-ray crystal structure available for the complete GABAB receptor system. However, crystal structures for the stable heterodimeric assembly of the extracellular VFT module of the human GBR1b (GBR1bVFT) and GBR2 (GBR2VFT) in ligand-free state (apo state) and in the presence of various agonists and antagonists have recently been determined.29 These structures have provided important insights into the GABAB architecture, molecular mechanisms of receptor heterodimerization, ligand recognition and receptor activation. The structural information also establishes a good basis for efficient design and discovery of new GABAB receptor modulators.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the structure of the GABAB receptor in resting (inactive) and active states. In the resting state, the GBR1b and GBR2 subunits attain an open-open state, but during receptor activation only the GBR1b subunit transits closed (resulting in a closed-open state). The orthosteric site resides in the GBR1b subunit of the VFT module, and the allosteric site is proposed to lie in the heptahelical TM domain of the GBR2 subunit, based on mutagenesis experiments (see main text). The GBR2 subunit couples with a G-protein for further signaling.

Agonists and Antagonists

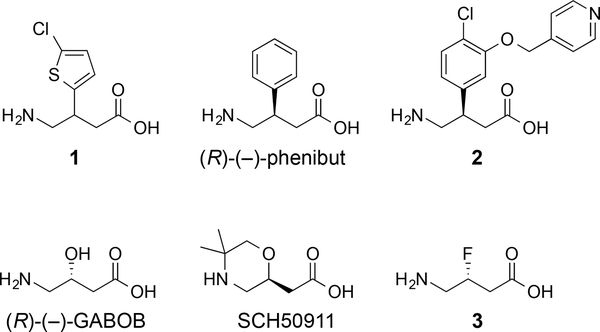

The first major agonist of the GABAB receptor, baclofen, was synthesized in 1962, and it was originally designed as a lipophilic analogue of GABA that would display enhanced permeability through the blood-brain barrier.12 Although baclofen does accumulate in the brain, this action is known to be aided by the large amino acid transporter.25, 44 On the other hand, its distribution is restricted because baclofen is effluxed by the organic anion transporters.24, 25 The pharmaceutical is a racemic mixture, but it was resolved and the (R)-(–)-enantiomer is substantially more active than the other enantiomer.45 For example, (R)-(–)-baclofen inhibits binding of [3H]baclofen to GABAB receptors in cat cerebellum with IC50 = 0.015 μM but (S)-(+)-baclofen inhibits with IC50 = 1.77 μM in this assay (100-fold difference in potency).46 Analogues of baclofen have been produced to understand the role of the carboxylic acid, amine, and para-chlorophenyl group.12 Replacement of the para-chlorophenyl group of baclofen with a 2-chlorothienyl group, compound 1, provides an active agonist with IC50 = 0.61 μM in the (R)-(–)-[3H]baclofen displacement assay, but substitution with a benzofuran produces a weak antagonist of the GABAB receptor (Figure 3).47, 48 Removal of the chlorine atom of baclofen results in another potent GABAB agonist, phenibut, and in a similar fashion, the racemic mixture is used, however (R)-phenibut displays the majority of the agonist activity at the GABAB receptor.49 For example, in radioligand-binding experiments, the affinity for racemic phenibut is Ki = 177 μM compared to 92 μM for (R)-phenibut and 6 μM for racemic baclofen. Adding ether substituents to the 3-position of baclofen provided the analogue 2, a potent GABAB agonist that stimulates currents at 60-fold lower concentration than (R)-baclofen in patch clamp experiments measuring the induction of GABAB receptor-mediated GIRK currents in rat hippocampal slices.50 Also, the compound 2 appears to cross the blood brain barrier as it demonstrates activity in rodent models of hypothermia. Replacing the aromatic substituent at the 3-position of baclofen with a hydroxyl group produces amino-3-hydroxybutanoic acid (GABOB).51 (R)-(–)-GABOB is an agonist of the GABAB (10-fold less potent than racemic baclofen in binding experiments from rat brain isolates) and GABAAρ receptors and (S)-(+)-GABOB is an agonist of the GABAA receptor and a partial agonist of the GABAB receptor.52 In these two cases, the configuration of the 3-position is critical to distinguish between agonist and antagonist behavior at the GABAB receptor, yet the agonist, (R)-(–)-GABOB, does not display the hydroxyl group on the same face as the para-chlorophenyl group of (R)-baclofen. The derivative (S)-(+)-5,5-dimethyl-2-morpholineacetic acid (SCH50911)53 can be envisioned to be a cyclized version of (S)-(+)-GABOB, and this analogue acts as an antagonist of the GABAB receptor.53 Specifically, SCH50911 inhibits the binding of GABA to GABAB receptors from rat brain with IC50 = 1.1 μM, but shows no binding affinity for the GABAA receptor. Exchanging the hydroxyl group of (R)-(–)-GABOB with fluorine provides (R)-3-fluoro-GABA 3 that is an agonist of the GABAA54 and GABAAρ55 receptors. Compounds 1–3, phenibut, GABOB, and SCH50911 bear a strong structural resemblance to baclofen by displaying the γ-aminobutyric acid core, yet they demonstrate that subtle changes can produce antagonists, eliminate activity at the GABAB receptor, or impart activity at other GABA receptors.

Figure 3.

Ligands of the GABAB receptor that display the structure of GABA. Compounds 1, 2, (R)-(–)-phenibut and (R)-(–)-GABOB are agonists of the GABAB receptor. SCH50911 is an antagonists of the GABAB receptor. Compound 3 is an agonist of the GABAA and GABAAρ receptors.

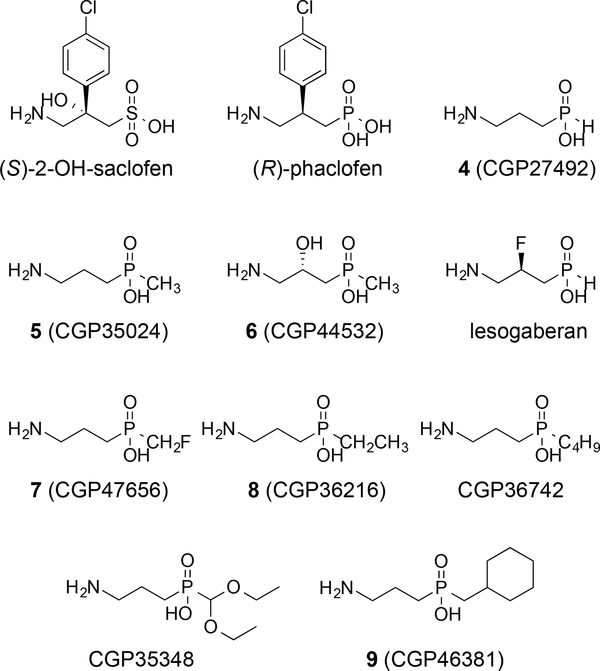

During the search for GABAB receptor ligands, a major divergence occurred when the carboxylic acid of γ-aminobutyric acid was replaced with potential bioisosteres such as sulfonic acids, phosphonic acids, and phosphinic acids.56 Although this change predominately results in the creation of antagonists of the GABAB receptor, the structure–activity relationships are of significance in the context of ligand design. For example, the phosphinic acid derivatives incorporate an additional alkyl substituent over the carboxylic acid and this component can aid in designing specific action across the receptors. (R)-Phaclofen, the phosphonic acid analogue of baclofen, was one of the first discovered antagonists of the GABAB receptor,57 followed closely by (S)-2-hydroxy-saclofen (Figure 4).58 (S)-2-Hydroxy-saclofen is 10-fold more potent an antagonist at the GABAB receptor than (R)-phaclofen. Additionally, (S)-2-hydroxy-saclofen can be compared to GABOB due to similar placement of the hydroxyl substituent. The phosphinic acid analogue of GABA, 4 (CGP27492),46 is a potent agonist (IC50 = 0.0024 μM) at the GABAB receptor in the [3H]baclofen binding assay in cat cerebellum and is nearly 15-fold more potent than baclofen.46 The methyl phosphinic acid analogue, 5 (CGP35024),46 is also an agonist of the GABAB receptor and is five times more potent than baclofen. Fluorine and hydroxyl substituents at the 3-position are well tolerated similar to these modifications of GABA. For example, the phosphinic acid, 6 (CGP44532),59 bears a 3-hydroxy group and retains activity as a GABAB receptor agonist.59 Furthermore, this compound demonstrates a 2-fold enhancement in potency compared to baclofen and an improved pharmacokinetic and CNS profile compared to baclofen in studies on Rhesus monkeys and rodents (rotarod test).46 The phosphinic acid, lesogaberan, displays a 3-fluoro substituent and functions as a GABAB receptor agonist.16, 17 It demonstrates binding affinity over 40-fold more potent (Ki = 5.1 nM for inhibition of [3H]GABA binding) than baclofen in rat brain GABA receptors yet lesogaberan primarily exhibits peripheral effects.60 Moreover, lesogaberan displays 87-fold more potent GABAB agonist activity (EC50 = 8.6 nM) in human recombinant GABAB receptors compared to racemic baclofen.60 On the other hand, lesogaberan is a contrast to its carboxylic acid equivalent 3, because the phosphonic acid derivative (lesogaberan) shows agonist activity at GABAB, whereas the subtle divergence in structure causes its absence in the carboxylic acid derivative 3.

Figure 4.

Analogues of GABA and baclofen in which the carboxylic acid is replaced. Compounds 4–6 and lesogaberan are agonists of the GABAB receptor, and 7 is a partial agonist of the GABAB receptor. (S)-2-hydroxy-saclofen, (R)-phaclofen, 8, CGP36742, CGP35348, and 9 are antagonists of the GABAB receptor.

The size of the alkyl substituent on the phosphinic acid plays a key role in distinguishing between agonist activity and antagonist activity at the GABAB receptor. Specifically, the methyl substituent is present on 5 and 6 and these compounds are agonists.46 As the size of the substituent increases in the case of the fluoromethyl group of 7 (CGP47656),46 the action of the molecule at the GABAB receptor is as a partial agonist. Further increases in size to the ethyl and butyl groups in 8 (CGP36216) and (3-aminopropyl)butylphosphinic acid (CGP36742),61 respectively, result in derivatives that display activity as antagonists of the GABAB receptor.61 The phosphinic acid bearing a methylcyclohexyl group, 9 (CGP46381),61 is also a potent antagonist. Moreover, (3-aminopropyl)diethoxymethylphosphinic acid (CGP35348)61 is a potent GABAB antagonist that penetrates the blood brain barrier upon i.p. administration.61, 62

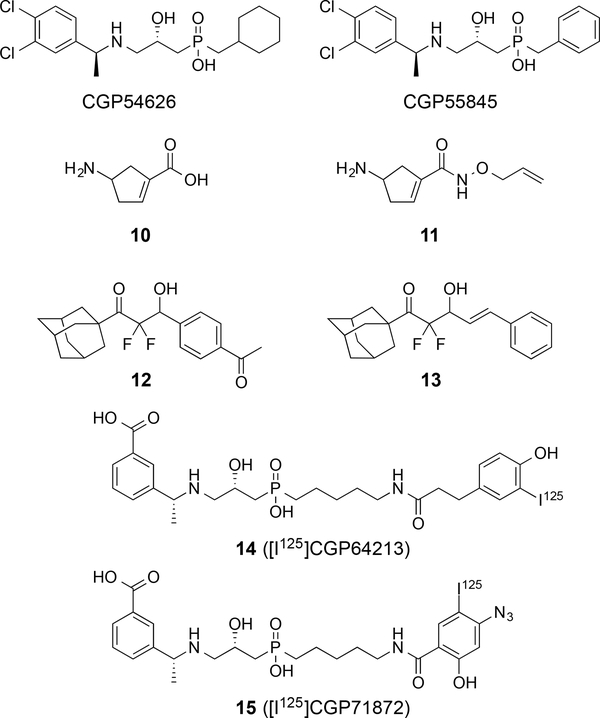

Another important structural modification is the addition of benzyl substituents to the nitrogen atom, because this manipulation usually imparts antagonist activity at the GABAB receptor in the nanomolar range. A representative group is the meta, para-dichlorobenzyl group as compounds (2S)-3-[[(1S)-1-(3,4-diclorophenyl)ethyl]amino-2-hydroxypropyl](cyclohexylmethyl)phosphinic acid (CGP54626) and (2S)-3-[[(1S)-1-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]amino-2-hydroxypropyl](phenylmethyl)phosphinic acid (CGP55845) are both highly potent antagonists63: compounds CGP54626 and CGP55845 display nanomolar potency as antagonists against mammalian GABAB receptors bound to bullfrog brain membranes (Figure 5).63 Antagonists with other substituted benzyl groups are well known in the literature.12 Studies on the conformational restriction of γ-aminobutyric acid into a five-membered ring provided 4-aminocyclopent-1-enecarboxylic acid 10 (4-ACPCA) that displays antagonist activity at the GABAAρ receptor and some agonist activity at the GABAA receptor.6 The design and synthesis of additional analogues of the cyclic scaffold produced compounds, such as 11, with enhanced activity at the GABAAρ receptor but replaced the agonist activity at the GABAA receptor with some activity at the GABAB receptor, in Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing recombinant GABA receptors. A class of structurally distinct agonists of the GABAB receptor was discovered in which each active compound displays a difluoromethyl ketone with a β-hydroxyl substituent (e.g., compounds 12 and 13).64 Compound 12 displays agonist activity in HEK293 cells expressing human GABAB receptors at a level that is 10-fold less potent than racemic baclofen; however, no activity was observed at the GABAA receptor. The fluorine atoms were critical, as demonstrated by the loss of activity for the non-fluorinated analogue of compound 12. Methylation of the β-hydroxyl substituent also eliminated activity at the GABAB receptor. Radiolabeled ligands of the GABAB receptor have been developed for understanding the presence of the receptor and these agents have been primarily produced from the potent antagonists displaying a N-benzyl group.12 For example, [H3]CGP54626, 14 ([I125]CGP64213),65 and 15 ([I125]CGP71872)66 are potent radiolabeled ligands for the GABAB receptor.66 The latter two compounds are powerful antagonists and present some of the largest substituent groups on the phosphinic acid. The azidophenol in 15 is the site of incorporation of the I125, and it also displays potency in the nanomolar range with a KD value of 1 nM.66

Figure 5.

Additional ligands of the GABAB receptor. CGP54626, CGP55845, 14, and 15 are antagonists of the GABAB receptor. Compounds 10 and 11 are antagonists of the GABAAρ receptor. Compounds 12 and 13 are agonists of the GABAB receptor.

Structure and Activation of the GABAB Receptor

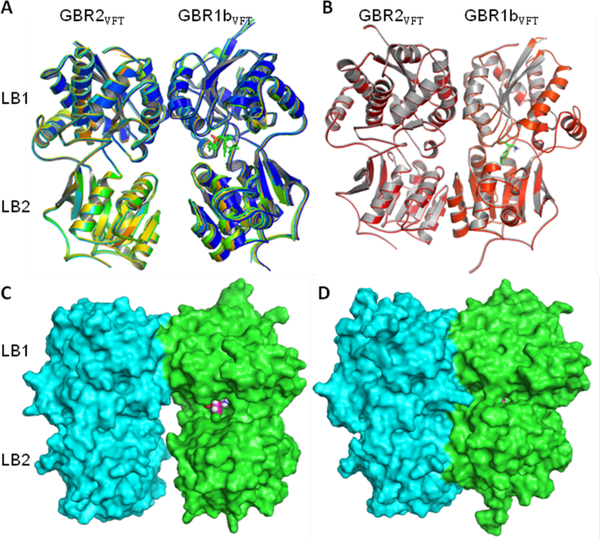

The GBR1bVFT and GBR2VFT subunits of GABAB receptor have similar bi-lobed architecture (33% sequence identity), like other class-C GPCRs, and each subunit contains two distinct domains, LB1 and LB2 (Figure 6). However, these two subunits have different interdomain arrangements. The ligand binding occurs within a large extracellular VFT module located at the crevice between the LB1 and LB2 domains of the GBR1bVFT subunit. The ligand-binding subunit GBR1bVFT can transit between open and closed conformations that correspond to resting (ligand-free or antagonist-bound) and active (agonist-bound) GABAB states, respectively. In contrast, the GBR2VFT subunit has identical conformations in both resting and active states of the GABAB receptor.29 The crystal structures of the GBR1bVFT:GBR2VFT complex bound to the antagonists CGP54626, 9, CGP35348, SCH50911, (S)-2-OH-saclofen, and (R)-phaclofen and to the agonists GABA and (R)-baclofen were published in 2013.29 All of the six antagonist-bound GABAB crystal structures resemble those of the apo or ligand-free structure in terms of both the heterodimeric arrangement as well as in the topology of individual subunits (Figures 6A and 6C). The ligand-binding crevice of GBR1bVFT remains open when bound to an antagonist. Agonist binding induces large conformational changes within the heterodimeric complex, leading to the closed conformation of the GABAB receptor (Figures 6B and 6D).29

Figure 6.

Cartoon depiction of superposed apo (blue) and antagonist-bound crystal structures (A) and of agonist-bound crystal structures (B) of the GBR1bVFT:GBR2VFT complex. Molecular surface of GBR1bVFT:GBR2VFT assembly bound to antagonist (R)-phaclofen (C), and that bound to agonist (R)-baclofen (D). The resting and antagonist-bound (inactive) GABAB receptors are found in an open state but the agonist-bound (active) receptor adjusts to a closed state. This image was generated using the PyMol molecular graphics software.67

In both the resting (open) and active (closed) states of the GABAB receptor, GBR1bVFT and GBR2VFT subunits interact through their LB1 domains (Figures 2 and 6). The LB1–LB1 heterodimeric interface involves formation of several hydrogen bonds (H-bond) or ion-dipole interactions, a few salt bridges, and a strong array of van der Waals (vdW) and hydrophobic contacts. Although the LB2 domains of the GBR1bVFT and GBR2VFT subunits remain separated in the resting state, agonist binding induces another heterodimeric interaction between the LB2 domains of the two subunits of the GABAB receptor.29, 68 The LB1–LB1 heterodimeric interface involves multiple interfacial H-bond interactions between several polar residues including the GBR1bVFT residues Thr198, Glu201 and Ser225, and the GBR2VFT residues Asp204, Gln206, Asn213 and Ser233. The LB1–LB1 interaction is mediated by the helices, but the LB2–LB2 interaction prevalent in the open or active state is mediated by loop-strand-helix motifs from each domain of the GBR1bVFT and GBR2VFT subunits. The agonist-induced formation of the LB2–LB2 heterodimeric interface is important for GABAB receptor activation and has been confirmed by alanine-scanning mutagenesis.29 In particular, the three deeply buried tyrosine residues (Tyr113 and Tyr 117 of GBR1bVFT and Tyr118 of GBR2VFT) at the heterodimer interface are critical for heterodimer interaction and receptor activation.43

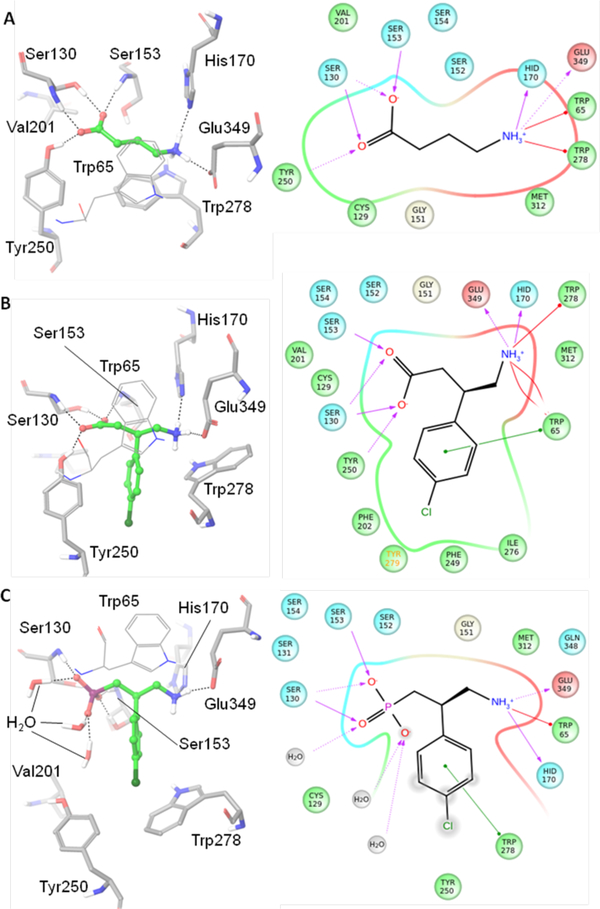

All of the agonists and antagonists bind within a large extracellular VFT module situated at the crevice between the LB1 and LB2 domains of the GBR1bVFT subunit. Depending on the nature of bound ligand (antagonist or agonist), the ligand-binding subunit GBR1bVFT attains open or closed conformations that correspond to the resting (inactive) and active GABAB states, respectively29 (Figures 2 and 6). Structurally, all of the co-crystallized agonists and antagonists are derivatives of GABA. Figure 7 depicts the GABAB amino acids and waters that interact directly or indirectly with the bound agonists and antagonists. The implication from the X-ray co-crystal structures is that agonist binding favors the closed conformation, and antagonist binding stabilizes the open conformation of the GBR1bVFT subunit. Furthermore, LB1 residues are necessary for recognition of both the agonist and antagonist, but the LB2 residues are primarily required for agonist recognition only (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 7.

Depiction of the GABAB amino acids and waters that interact directly or indirectly with bound agonists, GABA (A) and (R)-baclofen (B), or antagonist, (R)-phaclofen (C). 3D-(those that include the exact 3-dimensional geometry) and 2D-depictions of the protein-ligand interactions are on the left and right sides, respectively. These images were generated using the Schrödinger suite.69

The receptor–antagonist interactions are mediated mostly by multiple H-bonds with the LB1 domain of the GBR1bVFT subunit, and the LB2 domain interacts sparsely, as apparent in the available multiple X-ray crystal structures of the antagonist-bound GABAB receptor. The α-acid groups like carboxylic, phosphoric, sulfonic, etc., at one end form H-bonds with the LB1 residues Ser130 and Ser153, and the primary or secondary γ-amino group at the other end forms H-bonds to His170 and Glu349 (Figure 7C). The three-carbon linker present in all of the antagonists makes vdW interaction with Trp65 but its main role is to provide appropriate separation between the acid and amino end groups. Depending on structural features present in the antagonists, they exhibit other distinct interactions with the LB1 residues that are specific to them. For example, the β-hydroxyl group of CGP54626 and (S)-2-OH-saclofen exhibits H-bonding interactions with the LB1 residue that are specific to them. In addition, there are some common water-mediated H-bonds with the LB1 residue Ser131 that have been observed with all of the studied antagonists except SCH50911 and (R)-phaclofen.29

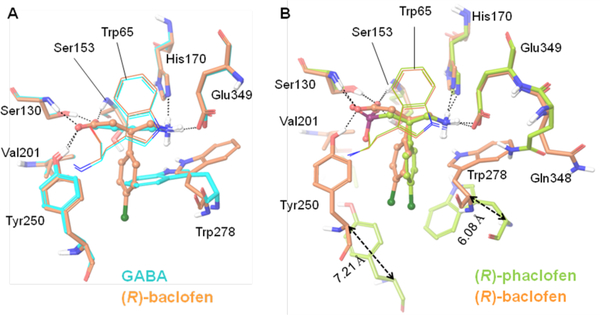

As found for antagonists, the endogenous agonist GABA and its synthetic derivative (R)-baclofen, which includes a β-(4-chlorophenyl) substituent, exhibit a common set of H-bonding interactions (Ser130 and Ser153 at one end, and His170 and Glu349 at the other end) and vdW contacts (Trp65) with the LB1 residues. However, unlike what is found for antagonists, these two agonists exhibit direct H-bonds with the LB2 residue, Tyr250, and strong vdW contacts with various LB2 residues (Figure 7). These additional interactions are due to a notable transition of the LB2 domain of the GBR1b subunit during receptor activation characterized by the closed state. This distinction is evidenced from X-ray crystal structures of GABAB-complexed with agonists and antagonists. The backbone Cα–Cα movements of Tyr250 and Trp278 from the active state to the inactive (resting) state are 7.21 and 6.08 Å, respectively (Figure 7), suggesting a phenomenal transition of the LB2 domain (GBR1b subunit) between the closed and inactive GABAB states. Most notably, the LB2 residue Tyr250 which forms an ion-dipole interaction with the negatively ionizable carboxylate group of the agonists GABA and (R)-baclofen remains far away and no H-bonding or ion-dipole interactions are apparent with Tyr250 in any of the antagonist-bound X-ray structures. Instead, a few water molecules are found to reside close to the antagonists and interact with the α-acid groups of antagonists (Figure 7C). The LB2 residue, Trp278, is highly flexible, exhibiting a wide rotameric adaptation of different conformations that can help the GABA receptor to recognize ligands (agonists or antagonists) of variable sizes in order to maintain ligand-binding affinity and specificity (Figures 7 and 8).29 The importance of the LB1 and LB2 residues has been implicated through mutagenesis studies (Table 1).

Figure 8.

Binding mode of ligands as shown in X-ray crystal structures.29 (A) Depiction of the differences in binding site residues of GABAB bound to the agonists, GABA (cyan) and (R)-baclofen (orange). The LB2 residue Trp278 is highly flexible, and undergoes rotameric transition to accommodate the bulky substituent p-chlorophenyl of (R)-baclofen. Other residues are conserved. (B) Depiction of the differences in binding site residues of the GABAB bound to the agonist (R)-baclofen (orange) and the antagonist (S)-phaclofen (green). As shown, the LB2 lobe of GBR1b undergoes major changes to govern the closed state of GABAB. The LB2 residues undergo major perturbation, especially Val201, Tyr250, and Trp278, which line the binding site during agonist binding (activation of the GABAB receptor). On the contrary, most of the LB1 residues, except for Gln348, are conserved in the resting (inactive) and active states of the GABAB receptor. Gln348 undergoes rotameric transition to allow a high degree of freedom to Trp278. The LB2 domain of the GBR1b subunit undergoes a major shift during the activation process. For example, the backbone Cαs of Tyr250 and Trp278 move 7.21 and 6.08 Å, respectively, between active and resting (inactive) states. These images were generated using the Schrödinger suite.

Table 1.

The importance of LB1 and LB2 residues, as implicated through mutagenesis studies.

| Mutation | Resulting effects |

|---|---|

| Tyr118Ala | Disruption of heterodimeric interaction between GBR1bVFT and GBR2VFT43 |

| Tyr113Ala, Tyr117Ala | Weakening of heterodimeric interaction between GBR1bVFT and GBR2VFT43 |

| Ser130Ala | Complete loss of binding of antagonist 1465, 70 |

| Ser153Ala | Moderate effect on ligand binding65, 70 |

| Gly151Val | Loss of binding of antagonist [3H]-CGP54626; drastic loss of receptor function43 |

| Glu349Ala | Substantial loss of binding of antagonist 14; loss of potency of agonists GABA and baclofen65, 70 |

| Trp65Ala | Substantial loss of ligand binding and receptor function29 |

| His170Ala | Complete loss of antagonist binding; lowering of the maximum agonist-induced [35S]GTPγS binding to half that of wild-type level29 |

| Trp278Ala | No effect on the binding of antagonist [3H]-CGP54626, but a decrease in its potency; detrimental effect on receptor activation; decrease in agonist potency29 |

| Tyr250Ala | No effect on the binding of antagonist [3H]-CGP54626, but a decrease in agonist response and potency29 |

Each antagonist contains a bulky substituent at either one or both of the α- and γ-positions, and these apparently inhibit the domain closure of the GBR1bVFT subunit (Figures 2 and 6). The bulky substituent of the antagonist interacts with the LB2 domain residues Tyr250 and Trp278 (Figure 7C), which possibly prevents the LB1 and LB2 domains of the GBR1bVFT subunit from approaching each other (Figures 6, 7C, and 8B). In particular, this would be expected to prevent the LB2 domain from undergoing the substantial transition that happens during the receptor activation characterized by a closed GABAB state. The two antagonists (S)-2-OH-saclofen and (R)-phaclofen contain sulfonic and phosphinic acid motifs, respectively, that are structurally analogous to the carboxylic acid of agonist (R)-baclofen. Their acid motifs assume tetrahedral coordination geometries that are observed to be incompatible with the active or closed state conformation of the LB2 residue Tyr250.29 It is also suggested that these acid motifs at the α-position, being comparatively bulky relative to carboxylate, push the 4-chlorophenyl group located at the β-position towards the γ-amino end of each antagonist, and hence could possibly create steric hindrance with the LB2 residues Ile276 and Trp278 that undergo significant transition during domain closure of the GBR1bVFT subunit.

Positive Allosteric Modulators and Negative Allosteric Modulators

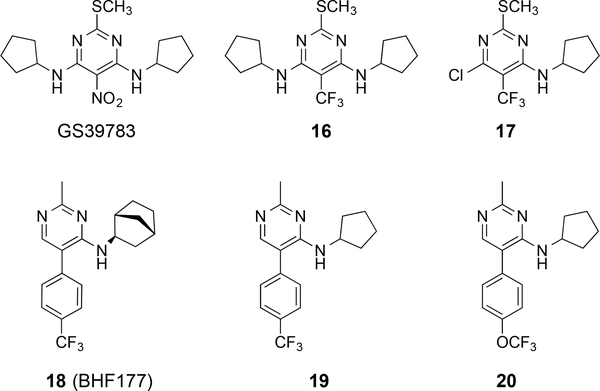

Three major structural classes of positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) have been described for the GABAB receptor in the literature: pyrimidines, di-tert-butylbenzenes, and thiophenes. These PAMs display no or some partial agonistic activity when applied alone in most assays, but enhance both the potency and efficacy of GABAB agonists (competitive or orthosteric ligands).38, 41 PAMs have been aggressively pursued in the context of drug design, because they are less likely to result in receptor desensitization than traditional GABAB agonists.71 Indeed, one of the typical drawbacks of baclofen use is that tolerance develops rapidly; therefore, this class of potential therapeutic agents was developed to display less tolerance and have an increased propensity for long-term use. The pyrimidine-based PAM, N,N’-dicyclopentyl-2-(methylthio)-5-nitro-pyrimidine-4,6-diamine (GS39783),72 was one of the first, potent molecules for allosteric activation of the GABAB receptor (Figure 9). GS39783 enhances the affinity of GABA at recombinant GABAB receptors in the [35S]GTPγS assay 8-fold and increases the maximal intrinsic efficacy for GABA 2.2-fold.72 Derivatives with alternative N-alkyl substituents were prepared along with analogues in which the thiomethyl group is exchanged for alkyl groups or a methoxy; however, GS39783 displays the highest potency. Other pyrimidine-derived compounds, such as 16 and 17, were designed with a trifluoromethyl group to eliminate the potential metabolic liability associated with the nitro group73 of GS39783.74 Compounds 16 and 17 displayed 106% and 139% potentiation compared to 192% for GS39783 in GABA-induced simulation of GTP(γ)35S binding. Pyrimidine 18 (BHF177)74 was also produced during optimization efforts upon GS39783, and two similar analogues are compounds 19 and 20. These compounds display the trifluoromethyl group but lack one of the alkyl aniline groups. Compound 18 is as potent as GS39783, but 19 and 20 display less than half of the potency of GS39783 in potentiating the effects of GABA. The binding site of the positive allosteric modulator, GS39783, was identified by point mutations in the heptahelical TM domain of the GBR2 subunit (GBR2TM). Specifically, the mutations G760T and A780P in TM6 were critical for allosteric activation, because mutations of these TM6 residues led to conversion of the PAM into an agonist.75 These sites are assumed to be involved in stabilizing the GBR2TM domain into an inactive conformation. It is proposed that the closure of the GBR1VFT domain signifying the active GABAB state conformation results in a new conformation of the heterodimer through an inter-subunit major rearrangement of the extracellular VFT domain. This new conformation, in turn, stabilizes the active state conformation of the GBR2TM domain for coupling with the G-protein. Recently, Matsushita and colleagues revealed through fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) studies that the extracellular VFT domain undergoes a major rearrangement, but the heptahelical TM domain of the GBR2 subunit undergoes a minor intra-TM rearrangement, during the receptor activation by an agonist.76 They also proposed that such a mode of receptor activation, involving a major inter-subunit rearrangement without any apparent intra-TM (intra-helical) structural changes, appears to be a common feature which applies to both the GABAB receptor and the metabotropic glutamate receptor 1α (mGluR1α), another class-C GPCR family member.76

Figure 9.

Pyrimidine-based allosteric modulators of the GABAB receptor.

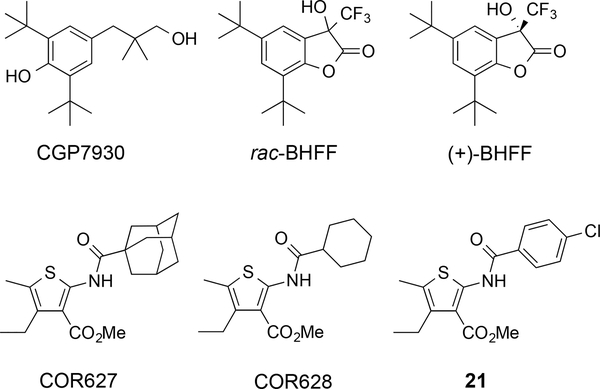

The calcium ion Ca2+ (a known PAM for the GABAB receptor) is proposed to stabilize the closed state of the extracellular GBR1VFT domain, but other PAMs bind to and stabilize the active conformation of the GBR2TM domain. These PAMs, other than Ca2+, may bind to their recognition sites (GBR2TM domain) when applied alone, but may not initiate the relative movement of the extracellular VFT domains of the two heterodimeric subunits the way that agonists do.41 The first discovered PAM was 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-(3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-propyl)-phenol (CGP7930)77 and it is not based on a pyrimidine scaffold (Figure 10).77 CGP7930 displays EC50 = 5.37 μM in GABA-induced stimulation of GTP(γ)35S binding at 1 μM GABA. During the characterization of the binding site of CGP7930 through various studies on the wild-type and chimeric GABAB subunits, Binet and colleagues revealed that only the heptahelical TM domain of the GBR2 subunit (GBR2TM) is required and sufficient for allosteric action.78 CGP7930 was then optimized into the fluorinated derivative, (R,S)-5,7-di-tert-butyl-3-hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-benzofuran-2-one (rac-BHFF),79 and separation of the enantiomers and subsequent biological evaluation demonstrated that (+)-BHFF was the potent PAM.79 The major structural advance was tethering the primary alcohol of CGP7930 with the phenolic hydroxyl group to form a cyclic lactone. At a concentration of 0.3 μM, rac-BHFF increased the potency of GABA by 15.3-fold with efficacy of 149% in GTP(γ)35S-binding assays compared to 87.3-fold increase and 181% efficacy with (+)-BHFF. The 2-(acylamino)thiophenes are the most recent class of PAMs to be discovered, and key members are methyl 2-(1-adamantanecarboxamido)-4-ethyl-5-methylthiophene-3-carboxylate (COR627) and methyl 2-(cyclohexanecarboxamido)-4-ethyl-5-methylthiophene-3-carboxylate (COR628),80 which were originally identified by a virtual screening protocol.80 Extensive optimizations led to the discovery of thiophene 21 that displays substantial activity in potentiating baclofen-induced sedation/hypnosis in mice, is active after intragastric administration, and fails to affect phenobarbital-induced sedative/hypnosis.81 The identification of new PAMs of the GABAB receptor continues to be an area of substantial interest due to the therapeutic potential, and new molecules are appearing in the literature, such as the PAM ADX71441 (structure not disclosed).82 Additionally, the arylalkylamines were reported to display activity as PAMs of the GABAB receptor,83 but subsequent evaluation in GTP(γ)35S-binding assays in the presence of GABA did not support that these molecules act in this fashion on the GABAB receptor.84

Figure 10.

Additional positive allosteric modulators of the GABAB receptor.

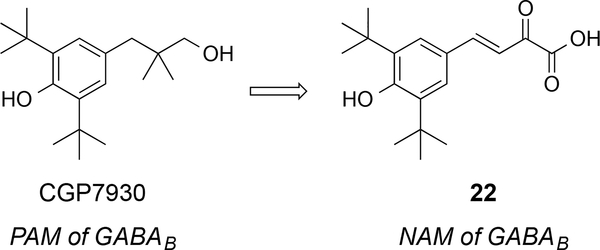

Negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) for the GABAB receptor were not known until 2014 and the first report described the discovery of a compound designed from CGP7930.85 The group of molecules acts as non-competitive antagonists of the GABAB receptor and they display the di-tert-butyl phenol scaffold that is present in other PAMs, such as CGP7930. The analogue 22 is the most active NAM and it does not bind into the orthosteric binding site of the GABAB receptor (Figure 11). The compound 22 decreased GABA-induced production of IP3 in HEK cells overexpressing GABAB receptors with IC50 = 37.9 μM. Even though it bears a common electrophilic group, an enone, specificity for the target was demonstrated for GABAB versus other GPCR class C members such as mGluR1, mGluR2, and mGluR5.

Figure 11.

First negative allosteric modulator of the GABAB receptor.

Conclusions

Since the discovery of the GABAB agonist and muscle relaxant, baclofen, there have been substantial advancements in the development of compounds that activate this receptor as agonists or PAMs. For the agonists, most of the existing structure–activity data applies to understanding the role of substituents on the backbone of GABA as well as replacing the carboxylic acid and amine groups. In the cases of the PAMs, the allosteric binding site(s) and structure–activity relationships are less well defined; however, multiple classes of molecules that act as PAMs have been discovered. Despite the preclinical and clinical investigations with PAMs, the fundamental question that remains to be answered is whether they will be therapeutically effective. Further studies are needed to characterize the therapeutic potential of these compounds. In terms of GABAB receptor structural information, there is now sufficient knowledge of the orthosteric site and recognition modes of various representative GABAB agonists and antagonists, but there is still a lack of knowledge of the allosteric site(s). A key topic of future exploration is whether multiple and distinct allosteric sites exist within GABAB receptors, especially in view of observations that some of the GABAB receptor PAMs (e.g. CGP7930) behave as allosteric agonists. The available X-ray crystal structures of agonist- and antagonist-bound GABAB receptors have established a platform for the use of state-of-the-art protein structure-based drug design tools to discover new ligands. From a therapeutic perspective, these data will enable additional efforts in drug discovery in areas of addiction-related behavior, the treatment of anxiety, and the control of muscle contractility. A major clinical question is whether modulation of the GABAB receptor can be used to effectively benefit patients afflicted with drug or alcohol addiction, as there is a substantial need to develop new agents for these conditions. Because the GABAB pathway is crucial in so many CNS related disorders, the stage is set for future investigations on this receptor to determine if it can be as pharmacologically lucrative as the extensively exploited GABAA receptor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Funding Sources

Authors acknowledge the University of Mississippi, Purdue University, Purdue Research Foundation, and the Ralph W. and Grace M. Showalter Research Trust for financial support. This investigation was also conducted in part in a facility constructed with support from the Research Facilities Improvements Program (C06 RR-14503-01) of the NIH National Center for Research Resources

ABBREVIATIONS

- CNS

central nervous system

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GABAA

γ-aminobutyric acid type A

- GABAB

γ-aminobutyric acid type B

- GABAC

γ-aminobutyric acid type C

- GABOB

amino-3-hydroxybutanoic acid

- GBR1b

γ-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit 1b

- GBR2

γ-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit 2

- GERD

gastro-esophageal reflux disease

- GIRK

G-protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channel

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- IP3

inositol triphosphate

- Kir3

potassium channel, inwardly-rectifying, member 3

- LB

ligand binding

- mGluR1α

metabotropic glutamate receptor 1α

- NAM

negative allosteric modulator

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- TM

transmembrane

- vdW

van der Waals

- VFT

Venus flytrap

Biographies

Katie M. Brown worked with Professor David A. Colby in the Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology from January 2012 to May 2014. She was the recipient of the Purdue College of Pharmacy Dean’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship in 2013 and is currently a pharmacy student at Purdue University.

Kuldeep K. Roy received his Ph.D. from the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi (India) under the guidance of Dr. Anil K. Saxena (Emeritus Scientist, CSIR-Central Drug Research Institute, Lucknow, UP (India) in 2012. He conducted his postdoctoral research at the Ewha Womans University, Seoul (South Korea) for about a year, and then moved to the United States where he is currently performing postdoctoral studies under Professor Robert J. Doerksen in the Department of BioMolecular Sciences at the University of Mississippi.

Gregory H. Hockerman received a Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, under the direction of Prof. Arnold E. Ruoho, and worked as a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Prof. William A. Catterall at the University of Washington. He is currently a professor in the Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology at Purdue University.

Robert J. Doerksen is an Associate Professor of Medicinal Chemistry in the Department of BioMolecular Sciences and a Research Associate Professor in the Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi. After receiving a Ph.D. in Chemistry from University of New Brunswick, Canada, under the guidance of Prof. Ajit Thakkar, he proceeded to postdoctoral fellowships in the Department of Chemistry at University of California, Berkeley, with Prof. Martin Head-Gordon, and in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, with Prof. Michael Klein. His research specialty is computational medicinal chemistry.

David A. Colby received a Pharm.D. from the University of Iowa, IA, and a Ph.D. from the University of California, Irvine, CA, working with Prof. A. Richard Chamberlin. He conducted postdoctoral studies at the Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, with Prof. Dale L. Boger, and in 2006, he joined the faculty at Purdue University in the Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology. He is currently an Associate Professor of Medicinal Chemistry in the Department of BioMolecular Sciences at the University of Mississippi and a Research Associate Professor in the Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the School of Pharmacy.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Froestl W, A Historical Perspective on GABAergic Drugs. Future Med. Chem. 2011, 3, 163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen RW; Sieghart W, International Union of Pharmacology. LXX. Subtypes of gamma-Aminobutyric AcidA Receptors: Classification on the Basis of Subunit Composition, Pharmacology, and Function. Update. Pharmacol. Rev. 2008, 60, 243–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanson SM; Morlock EV; Satyshur KA; Czajkowski C, Structural Requirements for Eszopiclone and Zolpidem Binding to the g-Aminobutyric Acid Type-A (GABAA) Receptor Are Different. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 7243–7252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chebib M; Johnston GA, The ‘ABC’ of GABA Receptors: A Brief Review. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1999, 26, 937–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drew CA; Johnston GAR; Weatherby RP, Bicuculline-Insensitive GABA Receptors: Studies on the Binding of (−)-Baclofen to Rat Cerebellar Membranes. Neurosci. Lett. 1984, 52, 317–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Locock KES; Yamamoto I; Tran P; Hanrahan JR; Chebib M; Johnston GAR; Allan RD, γ-Aminobutyric Acid(C) (GABAC) Selective Antagonists Derived from the Bioisosteric Modification of 4-Aminocyclopent-1-enecarboxylic Acid: Amides and Hydroxamates. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 5626–5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaupmann K; Huggel K; Heid J; Flor PJ; Bischoff S; Mickel SJ; McMaster G; Angst C; Bittiger H; Froestl W; Bettler B, Expression Cloning of GABAB receptors Uncovers Similarity to Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors. Nature 1997, 386, 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padgett CL; Slesinger PA; Thomas PB, GABAB Receptor Coupling to G-proteins and Ion Channels. Adv. Pharmacol. 2010, 58, 123–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuner R; Köhr G; Grünewald S; Eisenhardt G; Bach A; Kornau H-C, Role of Heteromer Formation in GABAB Receptor Function. Science 1999, 283, 74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar K; Sharma S; Kumar P; Deshmukh R, Therapeutic Potential of GABAB Receptor Ligands in Drug Addiction, Anxiety, Depression and Other CNS Disorders. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2013, 110, 174–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyacke RJ; Lingford-Hughes A; Reed LJ; Nutt DJ, GABAB Receptors in Addiction and Its Treatment. Adv. Pharmacol. 2010, 58, 373–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Froestl W, Chemistry and Pharmacology of GABAB Receptor Ligands. Adv. Pharmacol. 2010, 58, 19–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balerio GN; Rubio MC, Baclofen Analgesia: Involvement of the GABAergic System. Pharmacol. Res. 2002, 46, 281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehmann A; Jensen JM; Boeckxstaens GE, GABAB Receptor Agonism as a Novel Therapeutic Modality in the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Adv. Pharmacol. 2010, 58, 287–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizukami K; Sasaki M; Ishikawa M; Iwakiri M; Hidaka S; Shiraishi H; Iritani S, Immunohistochemical Localization of Gamma-aminobutyric acidB Receptor in the Hippocampus of Subjects with Schizophrenia. Neurosci. Lett. 2000, 283, 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brändén L; Fredriksson A; Harring E; Jensen J; Lehmann A, The Novel, Peripherally Restricted GABAB Receptor Agonist Lesogaberan (AZD3355) Inhibits Acid Reflux and Reduces Esophageal Acid Exposure as Measured with 24-h pHmetry in Dogs. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 634, 138–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alstermark C; Amin K; Dinn SR; Elebring T; Fjellström O; Fitzpatrick K; Geiss WB; Gottfries J; Guzzo PR; Harding JP; Holmén A; Kothare M; Lehmann A; Mattsson JP; Nilsson K; Sundén G; Swanson M; von Unge S; Woo AM; Wyle MJ; Zheng X, Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Novel γ-Aminobutyric Acid Type B (GABAB) Receptor Agonists as Gastroesophageal Reflux Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4315–4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filip M; Frankowska M; Sadakierska-Chudy A; Suder A; Szumiec Ł; Mierzejewski P; Bienkowski P; Przegaliński E; Cryan JF, GABAB Receptors as a Therapeutic Strategy in Substance Use Disorders: Focus on Positive Allosteric Modulators. Neuropharmacology 2015, 88, 36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filip M; Frankowska M, GABAB Receptors in Drug Addiction. Pharmacol. Rep. 2008, 60, 755–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brennan JL; Leung JG; Gagliardi JP; Rivelli SK; Muzyk AJ, Clinical Effectiveness of Baclofen for the treatment of Alcohol Dependence: A Review. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 5, 99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hering-Hanit R; Gadoth N, Baclofen in Cluster Headache. Headache 2000, 40, 48–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry-Kravis EM; Hessl D; Rathmell B; Zarevics P; Cherubini M; Walton-Bowen K; Mu Y; Nguyen DV; Gonzalez-Heydrich J; Wang PP; Carpenter RL; Bear MF; Hagerman RJ, Effects of STX (arbaclofen) on Neurobehavioral Function in Children with Fragile X Syndrome: A Randomized, Controlled, Phase 2 Trial. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 152a127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chumakov I; Nabirotchkin S; Cholet N; Milet A; Boucard A; Toulorge D; Pereira Y; Graudens E; Traoré S; Foucquier J; Guedj M; Vial E; Callizot N; Steinschneider R; Maurice T; Bertrand V; Scart-Grès C; Hajj R; Cohen D, Combining Two Repurposed Drugs as a Promising Approach for Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deguchi Y; Inabe K; Tomiyasu K; Nozawa K; Yamada S; Kimura R, Study on Brain Interstitial Fluid Distribution and Blood-Brain Barrier Transport of Baclofen in Rats by Microdialysis. Pharm. Res. 1995, 12, 1838–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohtsuki S; Asaba H; Takanaga H; Deguchi T; Hosoya K.-i.; Otagiri M; Terasaki T, Role of Blood–Brain Barrier Organic Anion Transporter 3 (OAT3) in the Efflux of Indoxyl Sulfate, a Uremic Toxin: Its Involvement in Neurotransmitter Metabolite Clearance from the Brain. J. Neurochem. 2002, 83, 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lal R; Sukbuntherng J; Tai EHL; Upadhyay S; Yao F; Warren MS; Luo W; Bu L; Nguyen S; Zamora J; Peng G; Dias T; Bao Y; Ludwikow M; Phan T; Scheuerman RA; Yan H; Gao M; Wu QQ; Annamalai T; Raillard SP; Koller K; Gallop MA; Cundy KC, Arbaclofen Placarbil, a Novel R-Baclofen Prodrug: Improved Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination Properties Compared with R-Baclofen. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 330, 911–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sills GJ, The Mechanisms of Action of Gabapentin and Pregabalin. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2006, 6, 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storici P; De Biase D; Bossa F; Bruno S; Mozzarelli A; Peneff C; Silverman RB; Schirmer T, Structures of γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Aminotransferase, a Pyridoxal 5′-Phosphate, and [2Fe-2S] Cluster-containing Enzyme, Complexed with γ-Ethynyl-GABA and with the Antiepilepsy Drug Vigabatrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 363–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geng Y; Bush M; Mosyak L; Wang F; Fan QR, Structural Mechanism of Ligand Activation in Human GABAB Receptor. Nature 2013, 504, 254–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips TJ; Reed C, Targeting GABAB Receptors for Anti-Abuse Drug Discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2014, 9, 1307–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agabio R; Colombo G, GABAB Receptor Ligands for the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder: Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pin JP; Kniazeff J; Goudet C; Bessis AS; Liu J; Galvez T; Acher F; Rondard P; Prezeau L, The Activation Mechanism of Class-C G-protein Coupled Receptors. Biol. Cell 2004, 96, 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bettler B; Kaupmann K; Mosbacher J; Gassmann M, Molecular Structure and Physiological Functions of GABAB Receptors. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 835–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowery NG; Bettler B; Froestl W; Gallagher JP; Marshall F; Raiteri M; Bonner TI; Enna SJ, International Union of Pharmacology. XXXIII. Mammalian gamma-aminobutyric acidB receptors: structure and function. Pharmacol. Rev 2002, 54, 247–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones KA; Borowsky B; Tamm JA; Craig DA; Durkin MM; Dai M; Yao W-J; Johnson M; Gunwaldsen C; Huang L-Y; Tang C; Shen Q; Salon JA; Morse K; Laz T; Smith KE; Nagarathnam D; Noble SA; Branchek TA; Gerald C, GABAB Receptors Function as a Heteromeric Assembly of the Subunits GABABR1 and GABABR2. Nature 1998, 396, 674–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaupmann K; Malitschek B; Schuler V; Heid J; Froestl W; Beck P; Mosbacher J; Bischoff S; Kulik A; Shigemoto R; Karschin A; Bettler B, GABAB-Receptor Subtypes Assemble into Functional Heteromeric Complexes. Nature 1998, 396, 683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White JH; Wise A; Main MJ; Green A; Fraser NJ; Disney GH; Barnes AA; Emson P; Foord SM; Marshall FH, Heterodimerization is Required for the Formation of a Functional GABAB Receptor. Nature 1998, 396, 679–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urwyler S, Allosteric Modulation of Family C G-Protein-Coupled Receptors: From Molecular Insights to Therapeutic Perspectives. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 59–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pin J-P; Kniazeff J; Binet V; Liu J; Maurel D; Galvez T; Duthey B; Havlickova M; Blahos J; Prézeau L; Rondard P, Activation Mechanism of the Heterodimeric GABAB Receptor. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004, 68, 1565–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kniazeff J; Galvez T; Labesse G; Pin JP, No Ligand Binding in the GB2 Subunit of the GABAB Receptor is Required for Activation and Allosteric Interaction Between the Subunits. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 7352–7361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pin JP; Prezeau L, Allosteric Modulators of GABAB Receptors: Mechanism of Action and Therapeutic Perspective. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2007, 5, 195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galvez T; Duthey B; Kniazeff J; Blahos J; Rovelli G; Bettler B; Prézeau L; Pin JP, Allosteric Interactions Between GB1 and GB2 Subunits are Required for Optimal GABAB Receptor Function. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 2152–2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geng Y; Xiong D; Mosyak L; Malito DL; Kniazeff J; Chen Y; Burmakina S; Quick M; Bush M; Javitch JA; Pin J-P; Fan QR, Structure and Functional Interaction of the Extracellular Domain of Human GABAB receptor GBR2. Nature Neurosci. 2012, 15, 970–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Bree JB; Audus KL; Borchardt RT, Carrier-Mediated Transport of Baclofen Across Monolayers of Bovine Brain Endothelial Cells in Primary Culture. Pharm. Res. 1988, 5, 369–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olpe HR; Demiéville H; Baltzer V; Bencze WL; Koella WP; Wolf P; Haas HL, The Biological Activity of D-Baclofen (Lioresal®). Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1978, 52, 133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Froestl W; Mickel SJ; Hall RG; von Sprecher G; Strub D; Baumann PA; Brugger F; Gentsch C; Jaekel J, Phosphinic Acid Analogs of GABA. 1. New Potent and Selective GABAB Agonists. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 3297–3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pirard B; Carrupt P-A; Testa B; Tsai R-S; Berthelot P; Vaccher C; Debaert M; Durant F, Structure-affinity Relationships of Baclofen and 3-Heteroaromatic Analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1995, 3, 1537–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berthelot P; Vaccher C; Musadad A; Flouquet N; Debaert M; Luyckx M, Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Analogs. New Ligand for GABA-B Sites. J. Med. Chem. 1987, 30, 743–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dambrova M; Zvejniece L; Liepinsh E; Cirule H; Zharkova O; Veinberg G; Kalvinsh I, Comparative Pharmacological Activity of Optical Isomers of Phenibut. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 583, 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu F; Peng G; Phan T; Dilip U; Chen JL; Chernov-Rogan T; Zhang X; Grindstaff K; Annamalai T; Koller K; Gallop MA; Wustrow DJ, Discovery of a Novel Potent GABAB Receptor Agonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 6582–6585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hinton T; Chebib M; Johnston GAR, Enantioselective Actions of 4-Amino-3-hydroxybutanoic Acid and (3-Amino-2-hydroxypropyl)methylphosphinic Acid at Recombinant GABAC Receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 402–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Falch E; Hedegaard A; Nielsen L; Jensen BR; Hjeds H; Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Comparative Stereostructure-Activity Studies on GABAA and GABAB Receptor Sites and GABA Uptake Using Rat Brain Membrane Preparations. J. Neurochem. 1986, 47, 898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bolser DC; Blythin DJ; Chapman RW; Egan RW; Hey JA; Rizzo C; Kuo SC; Kreutner W, The Pharmacology of SCH 50911: A Novel, Orally-Active GABAB Receptor Antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995, 274, 1393–1398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deniau G; Slawin AMZ; Lebl T; Chorki F; Issberner JP; van Mourik T; Heygate JM; Lambert JJ; Etherington L-A; Sillar KT; O’Hagan D, Synthesis, Conformation and Biological Evaluation of the Enantiomers of 3-Fluoro-γ-Aminobutyric Acid ((R)- and (S)-3F-GABA): An Analogue of the Neurotransmitter GABA. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 2265–2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamamoto I; Deniau GP; Gavande N; Chebib M; Johnston GAR; O’Hagan D, Agonist Responses of (R)- and (S)-3-Fluoro-[gamma]-aminobutyric Acids Suggest An Enantiomeric Fold for GABA Binding to GABAC Receptors. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7956–7958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ballatore C; Huryn DM; Smith AB, Carboxylic Acid (Bio)Isosteres in Drug Design. ChemMedChem 2013, 8, 385–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kerr DIB; Ong J; Prager RH; Gynther BD; Curtis DR, Phaclofen: A Peripheral and Central Baclofen Antagonist. Brain Res. 1987, 405, 150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kerr DIB; Ong J; Johnston GAR; Abbenante J; Prager RH, 2-Hydroxy-saclofen: An Improved Antagonist at Central and Peripheral GABAB Receptors. Neurosci. Lett. 1988, 92, 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ong J; Bexis S; Marino V; Parker DAS; Kerr DIB; Froestl W, Comparative Activities of the Enantiomeric GABAB receptor agonists CGP44532 and 44533 in Central and Peripheral Tissues. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 412, 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lehmann A; Antonsson M; Holmberg AA; Blackshaw LA; Brändén L; Bräuner-Osborne H; Christiansen B; Dent J; Elebring T; Jacobson B-M; Jensen J; Mattsson JP; Nilsson K; Oja SS; Page AJ; Saransaari P; von Unge S, (R)-(3-Amino-2-fluoropropyl) Phosphinic Acid (AZD3355), a Novel GABAB Receptor Agonist, Inhibits Transient Lower Esophageal Sphincter Relaxation through a Peripheral Mode of Action. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 331, 504–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Froestl W; Mickel SJ; von Sprecher G; Diel PJ; Hall RG; Maier L; Strub D; Melillo V; Baumann PA, Phosphinic Acid Analogs of GABA. 2. Selective, Orally Active GABAB Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 3313–3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olpe H-R; Karlsson G; Pozza MF; Brugger F; Steinmann M; Van Riezen H; Fagg G; Hall RG; Froestl W; Bittiger H, CGP 35348: A Centrally Active Blocker of GABAB Receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990, 187, 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Asay MJ; Boyd SK, Characterization of the Binding of [3H]CGP54626 to GABAB Receptors in the Male Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana). Brain Res. 2006, 1094, 76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Han C; Salyer AE; Kim EH; Jiang X; Jarrard RE; Powers MS; Kirchhoff AM; Salvador TK; Chester JA; Hockerman GH; Colby DA, Evaluation of Difluoromethyl Ketones as Agonists of the g-Aminobutyric Acid Type B (GABAB) Receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 2456–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Galvez T; Prézeau L; Milioti G; Franek M; Joly C; Froestl W; Bettler B; Bertrand H-O; Blahos J; Pin J-P, Mapping the Agonist-Binding Site of GABAB Type 1 Subunit Sheds Light on the Activation Process of GABAB Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 41166–41174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Froestl W; Bettler B; Bittiger H; Heid J; Kaupmann K; Mickel SJ; Strub D, Ligands for the Isolation of GABAB Receptors. Neuropharmacology 1999, 38, 1641–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.5.0.4 Schrödinger, LLC., New York, NY, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kniazeff J; Saintot PP; Goudet C; Liu J; Charnet A; Guillon G; Pin JP, Locking the Dimeric GABAB G-Protein-Coupled Receptor in its Active State. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 370–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schrödinger Release 2014–3: Maestro, version 9.9, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Galvez T; Parmentier M-L; Joly C; Malitschek B; Kaupmann K; Kuhn R; Bittiger H; Froestl W; Bettler B; Pin J-P, Mutagenesis and Modeling of the GABAB Receptor Extracellular Domain Support a Venus Flytrap Mechanism for Ligand Binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 13362–13369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gjoni T; Urwyler S, Receptor Activation Involving Positive Allosteric Modulation, Unlike Full Agonism, Does Not Result in GABAB Receptor Desensitization. Neuropharmacology 2008, 55, 1293–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Urwyler S; Pozza MF; Lingenhoehl K; Mosbacher J; Lampert C; Froestl W; Koller M; Kaupmann K, N,N’-Dicyclopentyl-2-methylsulfanyl-5-nitro-pyrimidine-4,6-diamine (GS39783) and Structurally Related Compounds: Novel Allosteric Enhancers of gamma-Aminobutyric Acid-B Receptor Function. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 307, 322–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bussy U; Chung-Davidson Y-W; Li K; Li W, Phase I and Phase II Reductive Metabolism Simulation of Nitro Aromatic Xenobiotics with Electrochemistry Coupled with High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 7253–7260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guery S; Floersheim P; Kaupmann K; Froestl W, Syntheses and Optimization of New GS39783 Analogues as Positive Allosteric Modulators of GABAB Receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 6206–6211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dupuis DS; Relkovic D; Lhuillier L; Mosbacher J; Kaupmann K, Point Mutations in the Transmembrane region of GABAB2 Facilitate Activation by the Positive Modulator N,N’-dicyclopentyl-2-methylsulfanyl-5-nitro-pyrimidine-4,6-diamine (GS39783) in the Absence of the GABAB1 Subunit. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 70, 2027–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matsushita S; Nakata H; Kubo Y; Tateyama M, Ligand-Induced Rearrangements of the GABAB Receptor Revealed by Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 10291–10299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Urwyler S; Mosbacher J; Lingenhoehl K; Heid J; Hofstetter K; Froestl W; Bettler B; Kaupmann K, Positive Allosteric Modulation of Native and Recombinant g-Aminobutyric Acidb Receptors by 2,6-Di-tert-butyl-4-(3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-propyl)-phenol (CGP7930) and its Aldehyde Analog CGP13501. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 60, 963–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Binet V; Brajon C; Le Corre L; Acher F; Pin JP; Prezeau L, The Heptahelical Domain of GABAB2 is Activated Directly by CGP7930, A Positive Allosteric Modulator of the GABAB Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 29085–29091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Malherbe P; Masciadri R; Norcross RD; Knoflach F; Kratzeisen C; Zenner MT; Kolb Y; Marcuz A; Huwyler J; Nakagawa T; Porter RHP; Thomas AW; Wettstein JG; Sleight AJ; Spooren W; Prinssen EP, Characterization of (R,S)-5,7-di-tert-Butyl-3-hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-benzofuran-2-one as a Positive Allosteric Modulator of GABAB Receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 154, 797–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Castelli MP; Casu A; Casti P; Lobina C; Carai MAM; Colombo G; Solinas M; Giunta D; Mugnaini C; Pasquini S; Tafi A; Brogi S; Gessa GL; Corelli F, Characterization of COR627 and COR628, Two Novel Positive Allosteric Modulators of the GABAB Receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012, 340, 529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mugnaini C; Pedani V; Casu A; Lobina C; Casti A; Maccioni P; Porcu A; Giunta D; Lamponi S; Solinas M; Dragoni S; Valoti M; Colombo G; Castelli MP; Gessa GL; Corelli F, Synthesis and Pharmacological Characterization of 2-(Acylamino)thiophene Derivatives as Metabolically Stable, Orally Effective, Positive Allosteric Modulators of the GABAB Receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 3620–3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kalinichev M; Palea S; Haddouk H; Royer-Urios I; Guilloteau V; Lluel P; Schneider M; Saporito M; Poli S, ADX71441, A Novel, Potent and Selective Positive Allosteric Modulator of the GABAB Receptor, Shows Efficacy in Rodent Models of Overactive Bladder. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 995–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kerr DIB; Ong J; Puspawati NM; Prager RH, Arylalkylamines are a Novel Class of Positive Allosteric Modulators at GABAB Receptors in Rat Neocortex. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 451, 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Urwyler S; Gjoni T; Kaupmann K; Pozza MF; Mosbacher J, Selected Amino Acids, Dipeptides and Arylalkylamine Derivatives Do Not Act as Allosteric Modulators at GABAB Receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 483, 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen L-H; Sun B; Zhang Y; Xu T-J; Xia Z-X; Liu J-F; Nan F-J, Discovery of a Negative Allosteric Modulator of GABAB Receptors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 742–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]